Introduction

Human-wildlife coexistence is an understudied field within the Human Dimensions literature. Primarily due to the difficulty in defining, studying and implementing its various facets, researchers and practitioners often end up defining it by what it is not – for example, the absence of violence or retaliation (Nyhus, 2016). Based on Carter and Linnell's 2016 definition, (Pooley et al., 2020, p. 2) described coexistence as “a sustainable though dynamic state, where humans and wildlife coadapt to sharing landscapes and human interactions with wildlife are effectively governed to ensure wildlife populations persist in socially legitimate ways that ensure tolerable risk levels.”

I would like to further complement the idea of coexistence as a dynamic, co-adaptive state by proposing that it can comprise at least two dimensions – negative and positive. To explore this concept, I draw upon Galtung's 1964 definition of negative and positive peace.

Considered by many as the Father of Peace Studies, Galtung offered an alternative theory of peace at a time when the dominant definition of peace was circumscribed to the absence of war or assault (Chambers, 2004; Gleditsch et al., 2014). He suggested that violence often took place in an environment where basic human needs had not been met. These included “most basic needs” such as life and survival, to “basic needs” such as food, health, and education, to “near-basic needs” such as freedom, career, and political participation, to “people's relation to nature” (Al-Abedine, 2017, p. 85).

The unfulfillment of human needs, according to him, led to “freezing” (e.g., apathy, withdrawal) or “boiling” (e.g., revolt, mutiny) (Rubenstein, 1990). Instability in political or domestic settings resulted in direct violence (e.g., wars, assault, terrorism), which was often a symptom of deep-seated structural and/or cultural inequities (Galtung, 2000). He thus considered violence as a triangle with direct, cultural and structural dimensions as its three sides. These ideas were crucial in advancing the definition of peace.

According to Forcey (1989), peace does not imply the absence of conflicts but instead, the absence of violence. Galtung defines peace as the progression toward mutually accepted social goals, which may be complex and difficult, but not impossible to attain (Galtung, 1969). By extension, negative peace can be understood as the absence of direct or visible violence. It is the cessation of undesirable oppression or retaliation. Positive peace, on the other hand, refers to the integration of human society (Galtung, 1964, p. 2). He later defined positive peace as the absence of structural and cultural forms of violence, which are often invisible (Galtung and Fischer, 2013). Positive peace thus relies on the creation of structures, institutions and attitudes that facilitate social justice, well-being, and harmony for all. Negative and positive peace may be separate dimensions but cannot exist without each other.

Since the goal of peace theory is to understand and further coexistence between individuals and groups, I argue that Galtung's ideas can also be applied to better understand human-wildlife coexistence.

Deconstructing Coexistence

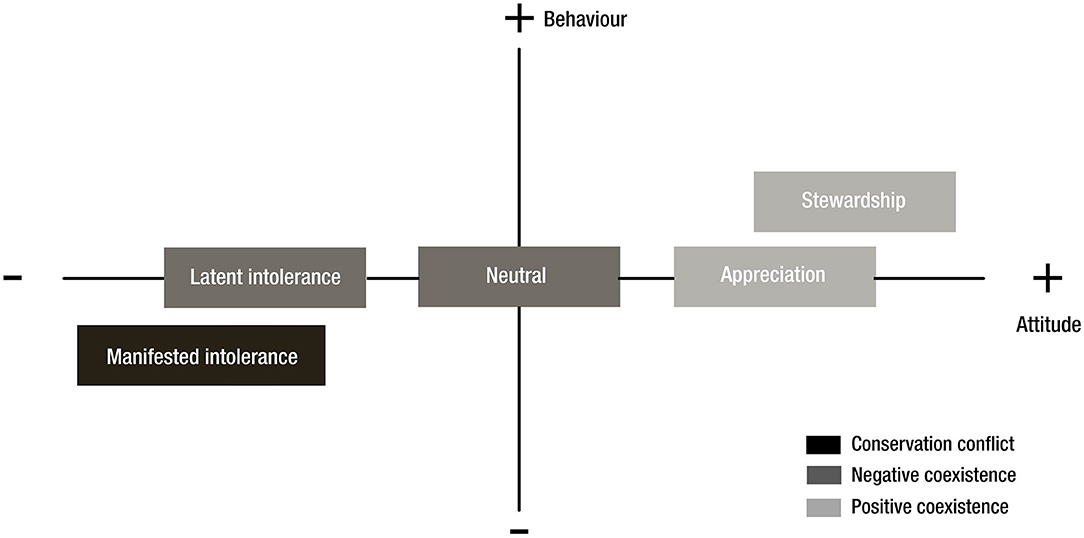

My central argument is that coexistence between people and wildlife can have “negative” and “positive” dimensions. To illustrate this, I refer to Bhatia et al.'s 2019 argument that tolerance – an essential component of coexistence – is a spectrum going from manifested intolerance (negative attitudes and behaviors toward wildlife) to stewardship (positive attitudes and behaviors toward wildlife) (Figure 1). Manifested intolerance comprises incidents that result in violence toward wildlife – a straightforward example of conservation conflict. Latent intolerance on the other hand, refers to the negative attitudes that do not result in violence toward wildlife which, along with neutral responses (ambivalent attitudes and behaviors), can be termed negative coexistence.

Figure 1. Visual representation of human response to wildlife impacts. Manifested intolerance refers to negative attitudes and behaviors toward wildlife. Latent intolerance comprises responses where attitudes are negative, but behaviors are not. Neutral refers to ambivalent attitudes and behaviors. Appreciation includes responses where attitudes are positive, but without corresponding positive behaviors. Stewardship includes positive attitudes and behaviors [Source: Adapted from Bhatia et al. (2019)].

Negative coexistence can thus be defined as a state in which people do not engage in any form of retaliatory killing or harm to wildlife though their attitudes may not necessarily be pro-conservation/pro-wildlife. To clarify, wild animals are often killed for subsistence or sport in many parts of the world. However, this definition refers to contextual killing, that is, killing in response to wildlife-caused damage (to people and/or property). While several factors affect an individual's decision to kill or harm wildlife, violence toward wildlife can be a result of deeply ingrained cultural biases, negative stereotyping, and/or structural or economic inequities (Chavez et al., 2005; Lucas, 2016).

Positive coexistence focuses on the cultural and structural dimensions. It needs an environment in which people feel emotionally and socially supported, and thus consider supporting wildlife conservation despite the costs. According to Bhatia et al.'s 2019 typology, positive coexistence would include aspects like appreciation (positive attitudes) and stewardship (positive attitudes and behaviors) (Figure 1).

The idea behind proposing this theoretical dichotomy is to illustrate that coexistence does not simply imply the absence of intolerance but can be a state of positive associations with and actions for wildlife. Often, the aim of conservation is to reduce behavioral intolerance which can be achieved through legal or moral means. It may be effective in reducing the anthropogenic impact on wildlife which, in Galtung's vocabulary, refers to a reduction in direct violence. However, it may not always translate to positive attitudes or behaviors – a goal that many conservationists (would like to) strive for. Positive coexistence can truly blossom in an environment that harbors socio-cultural, financial and emotional support systems that help people cope with losses and enable them to protect wildlife despite the odds. In short, it calls for a structural and cultural paradigm shift in which impacts are mitigated, and affected stakeholders feel connected to wildlife at the same time.

Ideological Complexities

A pertinent question to ask here is “coexistence for whom?” Like peace, coexistence is contextual and has multiple interpretations. For example, Galtung (1981) pointed out that peace theory tends to be skewed in favor of the powerful and is used to maintain status-quo in society. Schmid (1968) similarly criticized peace research by pointing out that facilitating negative peace, that is prohibiting violence, often means giving more power to the powerful while ignoring the needs and motivations of disenfranchised individuals or groups. Galtung's work has been criticized for not offering any criteria to assess and facilitate equity, and for using the terms like “equality” and “justice” interchangeably (Al-Abedine, 2017). These are valid criticisms of his ideas and are relevant for coexistence research too.

In the field of biodiversity conservation, for example, one tries to balance the needs of various human and non-human stakeholders some of whom may have diametrically opposite interests. How, then, can we come up with a unified idea of coexistence that is mutually acceptable to most, if not all groups? Moreover, is it even possible to transition to positive coexistence which, like Galtung's ideas, sounds all too utopian and nearly impossible to achieve (Bönisch, 1981; Gur-Ze-ev, 2001)? To add to it, we are not always well-versed with the nuances or standard/appropriate definitions of the various terminologies that we employ, and sometimes use them indiscriminately (e.g., human-wildlife conflict, tolerance, local communities, to name a few).

How does one navigate these challenges and complexities all the while attempting to facilitate and/or maintain coexistence? The theoretical, ideological, and practical challenges of applying the principles of peace research to our context can understandably be overwhelming. However, I would argue that this marriage can help reduce our efforts at reinventing the wheel (indeed, peace, conflict, coexistence is not unique to biodiversity conservation). Conservation practice requires us to think more carefully about how we engage with the problem and the efficacy of the various tools that we employ to deal with them.

Speaking of tools, Galtung defines peace using a mathematical formula [Peace = (Equity × Empathy)/(Trauma × Conflict)], which may seem strange at first. However, the formula can help us consolidate the learnings. According to the formula, mutual and equal benefit, and empathy for another's pain can enhance positive peace, whereas reconciling trauma and minimizing violence can enhance negative peace. To negotiate an acceptable version of peace, Galtung proposes a three-step approach which can help understand the origin of destructive behaviors and result in strategies to rectify them (Galtung, 2011).

From Ideology to Practice

The first stage is mapping where an external/disinterested negotiator individually speaks to each stakeholder (group or representative) and maps out the contours of the problem from their perspective. At this stage, they could enquire about the fears, hopes and aspirations of the stakeholder vis-à-vis the issue. Empathetic, compassionate and open communication can enable the group/representative to confide in the negotiator (Galtung, 2004). This stage involves determining what the goal of each stakeholder looks like.

The next stage is to legitimize the goal with the help of the law, human rights perspective and generally accepted ethics and social norms. For example, is the goal legal – does it involve actions that are legally prohibited? What are the human costs of pursuing the goal? What are the costs to wildlife and domestic animals in our case? These discussions can enable the negotiator to understand what is at stake and if there is wiggle-room.

The third and final stage is referred to as bridging where the negotiator assesses the compatibilities and incompatibilities between the goals of the different stakeholders. Through sustained dialogue and cooperation, they endeavor to find a middle ground that may be mutually acceptable.

Indeed, all of this is easier in theory than in practice. Further, as Pooley et al. (2020) pointed out, coexistence is a dynamic state implying that the same stakeholder group may feel differently toward wildlife in different situations/contexts. Additionally, the agency of the animals is completely missing from the discussion. The closest alternative to the voice of wild animals is the voice of conservationists who consider themselves capable of interpreting the needs of wildlife and wild places (Redpath et al., 2015). Similarly, local communities who tend livestock consider themselves legitimate representatives of their animals. Galtung's approach, some may argue, is more suited to human communities in conflict. However, numerous studies now suggest that human-wildlife conflict is essentially the conflict between the goals and aspirations of various human groups (Redpath et al., 2015, Peterson et al., 2010).

In recent times, toolkits like IUCN's CEPA and Snow Leopard Trust's PARTNERS Principles (Hesselink et al., 2007; Mishra, 2016) have provided practitioners with the skills to engage with communities. Such conservation toolkits combined with learnings from an allied field can enhance our efforts in the right direction. To me, the special feature of Galtung's three-step approach is the presence of an external negotiator. While this may be a luxury in a field that is fraught with funding issues and socio-political complexities, it is important to note that conservationists trying to find a middle ground to resolve wildlife-related conflicts may only be serving their own interests and agendas. Such impressions can put stakeholders on the defense, especially if the discussions assume a coercive tone, not to mention that these discussions usually reflect vast power asymmetries.

The negotiator, however, could be someone that most parties respect and hold in high regard – a person without vested interest. For example, it could be someone with experience in engaging with communities and wildlife management. The proposed solution(s), as Galtung insists, must strive to be constructive, concrete and creative, whilst being mindful that coexistence is a fragile and dynamic state that requires constant work. The three steps can enable us to better understand conflicts, validate different perspectives and design solutions that minimize or resolve friction. The aim is to move from negative coexistence to a positive one, which the three-step approach can facilitate. At the very least, we could try to intersperse the two depending on the context. In theory, positive coexistence is likely to last longer and may be more resilient because it calls for a structural shift that focuses on managing negative wildlife impacts, and enabling positive associations between people and wildlife.

There have been various theories of peace propagated by different schools of thought (see Kant, 1795; Kelman, 1993; Okoth, 2008). A full review is beyond the scope of this paper. Galtung's theories, however, have withstood the test of time and are based on a deep understanding of the situation on-ground (Lawler, 1989; Cravo, 2017).

The proposal presented here is an effort to learn from a field faced with similar challenges. The most significant one being the challenge of reconciling the needs of various stakeholders as well as arriving at a shared vision of the landscape, its people and the environment. The solutions that are devised within a particular socio-economic and cultural setup, however, may not generalizable though they may have common elements. It is thus important to be mindful that conservation challenges (especially conflict mitigation) are, in a sense, unique and require innovative approaches to ensure the well-being of all parties, humans and animals alike.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Pankaj Sekhsaria for reviewing a draft of this manuscript.

References

Al-Abedine, Y. Z. (2017). Western theories on conflict resolution and peace building: a critique. Int. J. Manage. Appl. Sci. 3, 83–92.

Bhatia, S., Redpath, S. M., Suryawanshi, K., and Mishra, C. (2019). Beyond conflict: exploring the spectrum of human–wildlife interactions and their underlying mechanisms. Oryx 54, 1–8. doi: 10.1017/S003060531800159X

Bönisch, A. (1981). Elements of the modern concept of peace. J. Peace Res. 18, 165–173. doi: 10.1177/002234338101800205

Carter, N. H., and Linnell, J. D. (2016). Co-adaptation is key to coexisting with large carnivores. Trends Ecol. Evol. 31, 575–578. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2016.05.006

Chambers, J. W., (ed.). (2004). The Oxford Companion to American Military History. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chavez, A. S., Gese, E. M., and Krannich, R. S. (2005). Attitudes of rural landowners toward wolves in northwestern Minnesota. Wildlife Soc. Bull. 33, 517–527. doi: 10.2193/0091-7648(2005)33517:AORLTW2.0.CO

Cravo, T. A. (2017). Peacebuilding: assumptions, practices and critiques. J. Int. Relations 8, 44–60. Available online at: https://repositorio.ual.pt/handle/11144/3032

Forcey, L. R., (ed.). (1989). Peace: Meanings, Politics, Strategies. New York, NY: Praeger Pub Text.

Galtung, J. (1969). Violence, peace, and peace research. J. Peace Res. 6, 167–191. doi: 10.1177/002234336900600301

Galtung, J. (1981). Social cosmology and the concept of peace. J. Peace Res. 18, 183–199. doi: 10.1177/002234338101800207

Galtung, J. (2000). The task of peace journalism. Ethical Pers. 7, 162–167. doi: 10.2143/EP.7.2.503802

Galtung, J. (2011). “TRANSCEND method,” in The Encyclopedia of Peace Psychology, ed D. J. Christie (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd). doi: 10.1002/9780470672532.wbepp280

Galtung, J., and Fischer, D. (2013). “Positive and negative peace,” in Johan Galtung, eds J. Galtung and D. Fischer(Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer), 173–178. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-32481-9_17

Gleditsch, N. P., Nordkvelle, J., and Strand, H. (2014). Peace research–Just the study of war? J. Peace Res. 51, 145–158. doi: 10.1177/0022343313514074

Gur-Ze-ev, I. (2001). Philosophy of peace education in a postmodern era. Educ. Theory 51:315. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-5446.2001.00315.x

Hesselink, F. J., Goldstein, W., van Kempen, P., Garnett, T., and Dela, J. (2007). Communication, Education and Public Awareness (CEPA): A Toolkit for National Focal Points and NBSAP Coordinators. Montreal, QC: Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity and IUCN.

Kant, I. (1795). Perpetual Peace: A Philosophical Sketch. Kant: Political Writings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 93–130.

Kelman, H. C. (1993). Conflict Resolution Theory and Practice: Integration and Application. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Lawler (1989). A question of values: a critique of Galtung's peace research. Interdiscip Peace Res. 1, 27–55. doi: 10.1080/14781158908412711

Lucas, A. (2016). Elite capture and corruption in two villages in Bengkulu Province, Sumatra. Hum. Ecol. 44, 287–300. doi: 10.1007/s10745-016-9837-6

Mishra, C. (2016). The Partners Principles for Community-Based Conservation. Seattle: Snow Leopard Trust.

Nyhus, P. J. (2016). Human–wildlife conflict and coexistence. Ann. Rev. Environ. Resour. 41, 143–171. doi: 10.1146/annurev-environ-110615-085634

Okoth, P. G. (2008). Peace and Conflict Studies in a Global Context. Kakamega: Published by Masinde Muliro University of Science and Technology Press in collaboration with Scholarly Open Press.

Peterson, M. N., Birckhead, J. L., Leong, K., Peterson, M. J., and Peterson, T. R. (2010). Rearticulating the myth of human–wildlife conflict. Conserv. Lett. 3, 74–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-263X.2010.00099.x

Pooley, S., Bhatia, S., and Vasava, A. (2020). Rethinking the study of human–wildlife coexistence. Conserv. Biol. doi: 10.1111/cobi.13653. [Epub ahead of print].

Redpath, S. M., Bhatia, S., and Young, J. (2015). Tilting at wildlife: reconsidering human–wildlife conflict. Oryx 49, 222–225. doi: 10.1017/S0030605314000799

Rubenstein, R. E. (1990). “Basic human needs theory: beyond natural law,” in Conflict: Human Needs Theory, ed J. Burton (London: Palgrave Macmillan), 336–355. doi: 10.1007/978-1-349-21000-8_17

Keywords: peace, violence, human-wildlife conflict, human-wildlife interactions, tolerance

Citation: Bhatia S (2021) More Than Just No Conflict: Examining the Two Sides of the Coexistence Coin. Front. Conserv. Sci. 2:688307. doi: 10.3389/fcosc.2021.688307

Received: 30 March 2021; Accepted: 17 May 2021;

Published: 09 June 2021.

Edited by:

Simon Pooley, Birkbeck, University of London, United KingdomReviewed by:

Juliette Young, Institute national de recherche pour l'agriculture, l'alimentation et l'environnement (INRAE), FranceCopyright © 2021 Bhatia. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Saloni Bhatia, c2Fsb25pODZAZ21haWwuY29t

Saloni Bhatia

Saloni Bhatia