95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Conserv. Sci. , 14 July 2021

Sec. Human-Wildlife Interactions

Volume 2 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcosc.2021.682590

This article is part of the Research Topic Planning and Decision-Making in Human-Wildlife Conflict and Coexistence View all 19 articles

Ee Phin Wong1,2*

Ee Phin Wong1,2* Ahimsa Campos-Arceiz3,4

Ahimsa Campos-Arceiz3,4 Natasha Zulaikha1,2

Natasha Zulaikha1,2 Praveena Chackrapani1,2

Praveena Chackrapani1,2 Aida Ghani Quilter1,2,5

Aida Ghani Quilter1,2,5 J. Antonio de la Torre1,3,4,6

J. Antonio de la Torre1,3,4,6 Alicia Solana-Mena1,7

Alicia Solana-Mena1,7 Wei Harn Tan2,3,4

Wei Harn Tan2,3,4 Lisa Ong2,3,4

Lisa Ong2,3,4 Muhammad Amin Rusli1,2

Muhammad Amin Rusli1,2 Sinchita Sinha1,2

Sinchita Sinha1,2 Vanitha Ponnusamy8

Vanitha Ponnusamy8 Teck Wyn Lim1,2

Teck Wyn Lim1,2 Oi Ching Or1,2

Oi Ching Or1,2 Ahmad Fitri Aziz1,2

Ahmad Fitri Aziz1,2 Ning Hii1

Ning Hii1 Ange Seok Ling Tan1

Ange Seok Ling Tan1 Jamie Wadey1,9

Jamie Wadey1,9 Vivienne P. W. Loke1,2

Vivienne P. W. Loke1,2 Abdullah Zawawi10

Abdullah Zawawi10 Muhammad Munir Idris10

Muhammad Munir Idris10 Pazil Abdul Patah10

Pazil Abdul Patah10 Mohd Taufik Abdul Rahman10

Mohd Taufik Abdul Rahman10 Salman Saaban1,10

Salman Saaban1,10Theory of Change (ToC) and Social Return of Investment (SROI) are planning tools that help projects craft strategic approaches in order to create the most impact. In 2018, the Management & Ecology of Malaysian Elephants (MEME) carried out planning exercises using these tools to develop an Asian elephant conservation project with agriculture communities. First, a problem tree was constructed together with stakeholders, with issues arranged along a cause-and-effect continuum. There were 17 main issues identified, ranging from habitat connectivity and fragmentation, to the lack of tolerance toward wild elephants. All issues ultimately stemmed from a human mindset that favors human-centric development. The stakeholders recognize the need to extend conservation efforts beyond protected areas and move toward coexistence with agriculture communities for the survival of the wild elephants. We mapped previous Human-Elephant Conflict (HEC) management methods and other governmental policies in Malaysia against the problem tree, and provided an overview of the different groups of stakeholders. The ToC was developed and adapted for each entity, while including Asian elephants as a stakeholder in the project. From the SROI estimation, we extrapolated the intrinsic value of the wild Asian elephant population in Johor, Malaysia, to be conservatively worth at least MYR 7.3 million (USD 1.8 million) per year. From the overall calculations, the potential SROI value of the project is 18.96 within 5 years, meaning for every ringgit invested in the project, it generates MYR 18.96 (USD 4.74) worth of social return value. There are caveats with using these value estimations outside of the SROI context, which was thoroughly discussed. The SROI provides projects with the ability to justify to funders the social return values of its activities, which we have adapted to include the intrinsic value of an endangered megafauna. Moreover, SROI encourages projects to consider unintended impacts (i.e., replacement, displacement, and deadweight), and acknowledge contributions from stakeholders. The development of the problem tree and ToC via SROI approach, can help in clarifying priorities and encourage thinking out of the box. For this case study, we presented the thinking process, full framework and provided evidences to support the Theory of Change.

Southeast Asia (SEA) is a region rich in biodiversity with complex biogeographic divides (Hughes, 2017), with four subspecies of Asian elephants (one extinct), five subspecies of tigers (two extinct), three extant species of orang-utans, a marine region that is high in coral diversity and many more. Three out of 11 countries in SEA, including Malaysia, are recognized as megadiverse countries (von Rintelen et al., 2017). This region has a very high number of megafauna species facing the potential threat of extinction (Ripple et al., 2017), even though these megafauna are often regarded as charismatic species that attract public attention. One megafauna of concern is the Asian elephant (Elephas maximus), currently listed as “Endangered” on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (IUCN, 2019). Malaysia's Asian elephant subspecies include the Mainland Asian elephant (Elephas maximus indicus) in Peninsular Malaysia and the Bornean Pygmy elephant (Elephas maximus borneensis) in Sabah. Previously, in the eighteenth century, it was suggested that the elephant population in Peninsular Malaysia was a distinct subspecies, Elephas maximus hirsutus, described solely based on morphology description of a single baby elephant (Lydekker, 1914); however, term is not widely used. The Asian elephant is facing diverse threats throughout its range that include habitat loss and fragmentation, human-elephant conflict, and poaching (Sukumar, 2003; Fernando and Pastorini, 2011; IUCN, 2019; Mahmood et al., 2021).

One of the main challenges for wildlife research and conservation projects is in attracting long-term funders, as stakes are often high and with real possibilities of failures. Moreover, the scarcity of funds and a plethora of environmental and biodiversity related organizations, often results in high competition for project grants. Project planning tools such as problem tree and Theory of Change (ToC), have the potential to help projects strategize their approach and focus to create the most impactful change. It is useful in identifying suitable project Monitoring & Evaluation (M&E) indicators to monitor project progress (Rice et al., 2020). Donors themselves are very concerned about project outcomes and many funders are using M&E tools since the 1990s to monitor and measure project impact on the ground (Stem et al., 2005; Cameron, 2012). Key challenges in using M&E tools include the need to transfer project planning skills from the realm of expert planners to project executants (Cameron, 2012; Golini et al., 2018), and to define the real impact of the project on the ground (Stem et al., 2005). In terms of impact, it is often challenging to capture both the visible and invisible outcomes of the project in a quantifiable manner.

The Social Return Of Investment (SROI) approach is often used for measuring the social, environmental and economic impact of the social entrepreneurs, and it is usually conducted as a forecast at the conceptualization of the project or as an evaluation of the project after completion (Lingane and Olsen, 2004; Nicholls et al., 2021). What makes SROI unique from other project planning tools is the consideration given to both bad (usually unintended) and good consequences of the project. Based on the framework set by Nicholls et al. (2021), the SROI calculations include consideration if the project is taking over an existing activity that is producing the same change at the study site or if the project is moving the problem elsewhere (displacement). It includes the null hypothesis scenario, whereby if the project did not take place, would the project outcome still be realized (deadweight). Additionally, it requires the project proponent to give credit and acknowledgment to other players in the landscape (attribution). With this, SROI is able to guide the project executants to consider, in a holistic manner, the impact that they can create via the project and provide a transparent projection of social return value to the donors. There are concerns if SROI may be biased toward the “economic return” of investment, and conservationists may be wary that the measurement of “social and environmental values” in SROI may encourage “monetization” of the values. It is important to emphasize that the purpose of SROI is to help project executants to visualize the impact of the project on the ground for project planning and monitoring purposes, and additionally to provide justification to funders. The calculations for SROI cannot be used outside the scope of these purposes, and important caveats are further elaborated in the Discussion section. The framework deploy by SROI is to provide a centralized measurement for both tangible and intangible outcomes, mainly to help support management decisions.

In this study, we explore the use of the SROI framework (Nicholls et al., 2021) to support the development of Theory of Change for a human-elephant coexistence project via a collaborative approach with stakeholders. The Management & Ecology of Malaysian Elephants (MEME) is a project established in 2011 to conduct science-based research in order to support evidence-based management of wild Asian elephants in Peninsular Malaysia. The project is carried out in collaboration with the Department of Wildlife and National Parks (PERHILITAN) in Peninsular Malaysia and with various other partners from non-governmental organizations, academia, and private sectors.

We examined the publication trends via the Web of Science search engine on 10th March 2021. The key phrase “Theory of Change,” was searched through all the years with fixed word order, and subsequently the results were filtered with “Conservation OR Wildlife OR Environmental” keywords individually and collectively to examine the use of the theory in these fields. We examined the trend of Social Return of Investment via the more popular keyword “SROI” in combination with “Social” to avoid picking up other research or terms with identical acronyms. We used the keywords “wildlife” AND “conflict or coexistence,” which generated more hits compared to “human-wildlife conflict,” and filter the results for Asian elephants in general and specifically within South East Asian countries.

A problem tree is used for identifying issues or obstacles to the goal and to prioritize the issues along a cause-and-effect continuum (Alvarez et al., 2010). This exercise is conducted via a respectful discourse with stakeholders. Two planning exercises were conducted on 19th July 2018 and 7th November 2018 at the University of Nottingham Malaysia campus in Semenyih with the same group of 15 people attending both sessions. The discussion team includes a social scientist from the Nottingham Business School, two members of the IUCN Asian Elephant Specialists Group, two PERHILITAN staff who were managing human-elephant conflict cases on the ground and several other MEME researchers and students, with ages ranging from 20's to 50's. Collectively, the group represents more than 90 years of working experience (range: 3–20 years/ individual) from academic, non-governmental organizations, governmental agency, and the private sector (plantations and consultancies).

The group carried out ad libitum brainstorming to identify challenges to elephant conservation in Malaysia, represented by keywords written on flashcards. This was followed by the creation of the problem tree by the rearrangement of the flashcards along a cause-and-effect continuum, with the root cause at the bottom of the tree, and the effects placed upwards in the order of one (cause) leading to the other (effect) forming the branches of the tree. The process was moderated by the lead author who has prior experience conducting such planning exercises. Subsequently, the interrelationships between the issues were defined further using systems thinking (Haraldsson, 2004), whereby arrows representing same relationship or oppositional relationship were drawn to connect the issues. Two issues connected via arrows of same relationship (i.e., A increase B, and B increase A) then, it is considered a reinforcing loop. While two issues connected with opposing relationship (i.e., A increase B, but B reduces A) then it is considered as a balancing loop or negative-feedback loop (Mahajan et al., 2019).

Theory of Change is a logical argument outlining the steps required to reach the goals and is recognized to be useful for tackling conservation conflicts (Baynham-Herd et al., 2018) and in helping conservation projects create impact (Stem et al., 2005). We develop the Theory of Change for individual stakeholders, using an emerging concept, SROI, to integrate social, economic and environmental values and quantify invisible outcomes of the project. The SROI mirrors the more popular project planning tool, Logical Framework Assessment, but with additional components. The concept of SROI is largely based on seven fundamental principles as quoted here: “involve stakeholders, understand what changes, value things that matter, only include what is material, do not over-claim, be transparent and verify the result” (Nicholls et al., 2021).

To carry out an SROI analysis, there are six stages or steps: “(i) Establishing a scope and identifying key stakeholders, (ii) Mapping outcomes, (iii) Evidencing outcomes and giving them a value, (iv) Establishing impact, (v) Calculating the SROI, and (vi) Reporting, using and embedding.” An Excel template is used for capturing all critical information in a systematic manner and to derive the SROI ratio calculation (Nicholls et al., 2021).

The foundation of SROI is the acknowledgment that project activities will actively create and/or destroy values, and result in changes (Lingane and Olsen, 2004; Nicholls et al., 2021). To measure changes that occur requires the project proponent to estimate a monetary value for the outcomes, which in turn need to be supported by evidence. The evidence provided is not expected to be accurate (approximation is sufficient), but it needs to be reliable, realistic and consistent. Based on Nicholls et al. (2021), the formula given for Impact value is denoted as the Outcome value after the deduction of deadweight, displacement, and attribution estimation. And the SROI ratio value would be the total impact value divided by total input.

Impact value = Outcome – Deadweight – Displacement – Attribution

SROI = Total Impact Value/ Total input

To calculate Input value, in addition to funds given by donors, additional in-kind contributions by stakeholders such as direct participation in activity and sponsorship are included. We quantify the direct participation of stakeholders in activities in terms of hours or man-days for the whole project duration, which is then converted into manpower value by estimating the daily cost of hiring a daily paid assistant to do the work. Meanwhile, we calculate the intrinsic value of Outcome by multiplying in-kind contribution (manpower value) invested by the stakeholder/s by the number of people in the community who will benefit from the investment. For example, an officer entrusted by an estate to learn and carry out safety guidelines for managing conflict with elephants may invest 1 day per week toward this purpose, but his or her action and knowledge could potentially benefit the safety of all staff and families staying in the estate. The SROI framework considers as well if the impact from the activity may last more than a year, and flexible enough for adjustment of success rates to account for some participants dropping out half-way or discontinuing the program after it ends.

We estimated the monetary value for wild elephants by extrapolating the results of a published study by Poh and Mohd Shahwahid (2008) that evaluated the average willingness to pay for wild elephant conservation and well-being as MYR 5.86/ person (N = 200) that was gathered from communities living in Human Elephant Conflict (HEC) area around Pahang, Terengganu and Taman Negara National Park. This value is potentially biased toward a lower value, as members of the public in urban areas have a higher appreciation for wildlife conservation (Guérin et al., 2017; Tan et al., 2020). We projected the value to a population of 32.6 million people in Malaysia (Department of Statistics Malaysia Official Portal, 2020) and prorated the value with estimated number of elephants in different parts of Peninsular Malaysia (Saaban et al., 2011) and Sabah (Alfred et al., 2011). We assumed that there will be no drop off in the intrinsic value of the elephants in the subsequent years of the project.

Deadweight estimation, requires the consideration that if the project did not take place, would the outcome (if not fully, then at what percentage) still be realized by other stakeholders? We derive the percentage calculation by considering ongoing efforts by stakeholders in the study area and denote 50% if there are other stakeholders with an overlap in activities and 25% if they are working on elephant conservation in general (without overlap). Displacement value is the consideration of whether the project is taking over an existing activity that is producing the same change or if the problem is being shifted elsewhere. Since the project is engaging with all parties who are actively working on wild elephant conservation at the study site as research partners, to build on each other's effort (avoid duplication) and jointly deliver the outcome, hence displacement is valued at 0%. The contributions from partners are captured under Attribution, which is the estimation of the efforts contributed by partners to help make the activity or goal successful. For activities that require a partner to participate fully (as part of empowerment), we denote the attribution value as 50%, and for activities that require direct support by partner/s to realize the outcome, we divided the percentage with the number of key sectors (i.e., government, public, private, and NGOs) involved. We are unable to outline fully each calculation and evidence prepared for ToC here, please see the full SROI framework under Supplementary Table 1.

A general search of “Theory of Change” on the Web of Science (WoS) revealed 1,018 publications predominantly in the field of occupational health, education, psychology and social sciences from the last 20 years. Collectively, there were 102 ToC publications in conservation, wildlife and environmental fields with most articles being published in the last 6 years. Out of all, only nine publications found were on wildlife. Meanwhile, the search for SROI revealed only 145 publications, mainly in business economics, environmental sciences and social sciences published in recent years, but none for wildlife.

Although “wildlife” and “conflict OR coexistence” by themselves generated 4,127 publications on WoS, only 2.6% were from South East Asia, while 3.8% were on Asian elephants. Although there are ToC papers on poaching and wildlife trade, there are no ToC or SROI specifically for elephants.

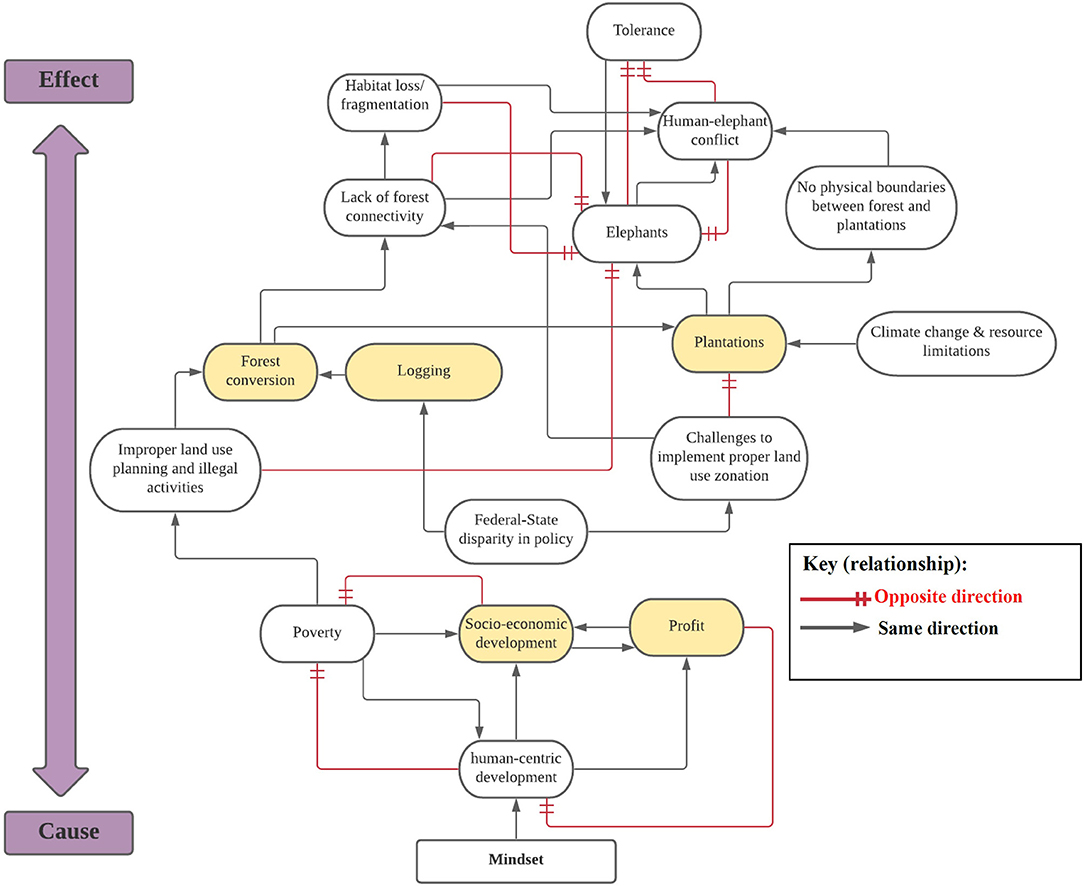

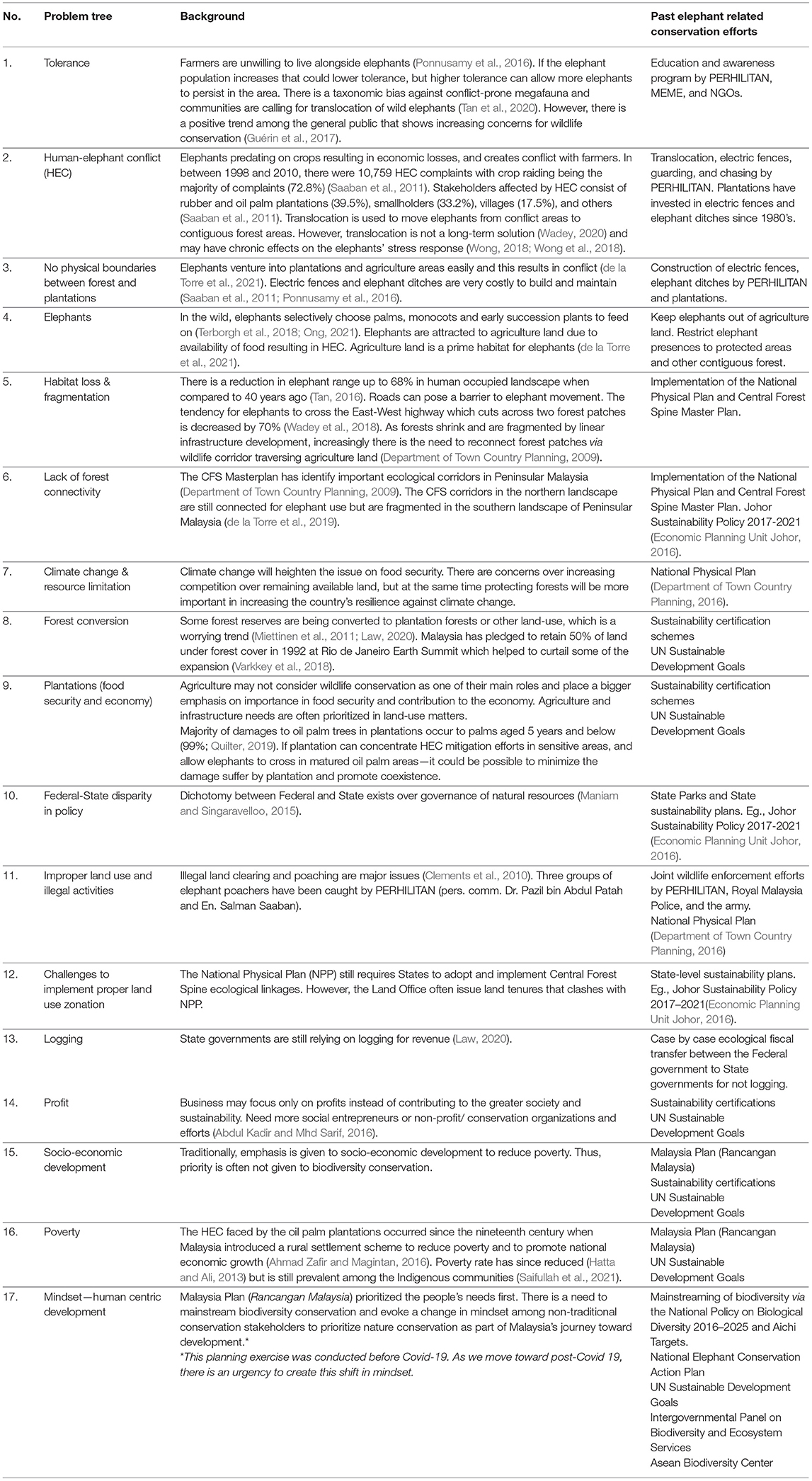

The problem tree was constructed (Figure 1) by arranging challenges related to elephant conservation on a continuum scale with the causes at the “root” ascending to effects in the tree branches. The background for the challenges was elaborated in Table 1, and previous HEC mitigation in the past and other relevant efforts were captured according to the issues. Considering project limitations, we scope the project toward interventions targeting root, middle and top of the problem tree, focusing on “changing mindsets,” “working with plantations to improve forest connectivity” and “fostering tolerance” respectively (Table 2).

Figure 1. The problem tree identifying challenges for wild elephant conservation arranged on a cause-and-effect continuum, with relationships between issues depicted using systems thinking approach. Note that priority was given to highlight relationships directly impacting wild elephants. Although there are synergies and interactions for certain issues (highlighted in beige), but the relationships between these issues are complex and are not depicted fully.©2021 by Dr. Wong Ee Phin is licensed under Attribution-Non-Commercial 4.0 International. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

Table 1. Background to the issues presented in the problem tree, with past conservation efforts in Malaysia.

We calculated an intrinsic value of wild elephants for the study site in Johor to be at least MYR 7.3 million (~USD 1.8 million) per year based solely on willingness to pay for the well-being of elephants in the forest, without considering elephants' ecosystem services or its role as an umbrella species that help conserve other wildlife. This intrinsic value of conserving wild elephants is shared equally with all key stakeholders as all sectors have to play a role to secure the existence of wild elephants in the landscape (see 2.4 Attribution).

The total input is estimated at the value of MYR 3.92 million for the period of 3 years. The total impact value was estimated to be at least MYR 14.59 million, with the SROI ratio of 3.72 (for every ringgit invested in the project, it brings a social return of investment worth MYR 3.72). When the project impact is projected for 5 years, the SROI per amount invested is 18.96.

We included Asian elephants in the study site as a stakeholder, alongside government agencies, non-governmental organizations, agriculture communities and private sectors (Table 2), and justified the ToC and indicators of monitoring (see Supplementary Table 1).

The project Management & Ecology of Malaysian Elephants (MEME) used project planning tools such as problem tree and Theory of Change (ToC) to conceptualize a new phase of conservation work for elephants. We documented the thinking process and introduced the use of the Social Return Of Investment (SROI), which mirrors the logistic framework approach in the development of ToC, but with additional considerations for quantifying intangible outcomes.

Through the problem tree exercise, we acknowledged that in Malaysia, the established mindset of the government and society is to prioritize people's welfare first, and the country's development plans in the past have mostly been human-centric (Nagulendran et al., 2016). After World War II ended in 1945, Malaysia's concern was on alleviating poverty. After more than six decades of independence, Malaysia has managed to reduce her poverty level to 3.8% in 2009 (Hatta and Ali, 2013), however many indigenous communities are still living below National hardcore poverty line (Saifullah et al., 2021). These communities often face crop depredation and other types of conflict with wild elephants, although most are still influence by their ancestor's culture that imbued respect for the elephants (Lim, 2018). By applying systems thinking on the problem tree, which helps to visualize the intricacies of interrelationships between factor (Mahajan et al., 2019), we recognized that with reduction of the poverty rate and as the larger society becomes more affluent (with an increase in profit), there are opportunities to shift the society's focus on human-centric development toward balanced development that supports wildlife conservation (Guérin et al., 2017; Tan et al., 2020) or toward a more eco-centric mindset (Taylor et al., 2020). In other parts of the world, there are similar shifts in societal values moving toward support for biodiversity conservation (Manfredo et al., 2021).

Malaysia is a signatory to various international treaties including the Convention of Biological Diversity, Aichi Targets and we have adopted the United Nations Sustainability Development Goals which may influence the trajectory to move away from a human-centric mindset (Government of Malaysia, 2012). Internationally, due to the demand of consumers for products with sustainable certification, plantations are extending their Corporate Social Responsibility remit toward nature and wildlife (Quilter, 2019). We identify this as an opportunity to bring on-board the wider society to support wild elephant conservation in particular. Furthermore, our past studies have indicated that wild elephants will be attracted to the agricultural landscape (de la Torre et al., 2021) for food (Terborgh et al., 2018; Ong, 2021), and simultaneously we recognized that plantations can potentially help to reconnect forest patches by establishing wildlife corridors (Department of Town Country Planning, 2009). By carrying out interventions that can help increase the tolerance of the agriculture communities toward wild elephants, and by reconnecting some of the larger forest patches, it may help to create more favorable circumstances to support the wild elephant population (Figure 1).

The objectives for the project are selected by considering the relationship between issues on the problem tree and the scope of the project. The prioritization of issues according to the cause-and-effect continuum effectively mean that interventions targeting issues closer to the roots will benefit issues above, as in efforts in tackling the cause can help minimize the effect. By designing a ToC that consider the relationship between issues, and by evaluating and prioritizing stakeholders together with SROI value, conservation projects, especially those dealing with conservation conflict, can identify areas where they can deliver the highest impact (Biggs et al., 2017; Rice et al., 2020). However this approach does not take into account the potential underlying conflict between stakeholders and hence further scoping work may be required on the ground to understand the power dynamics of the community (Zimmermann et al., 2020). During the course of project implementation, there could be a need to reiterate some parts of the planning process together with stakeholders on the ground (i.e., plantations and smallholders) to identify new issues and to verify assumptions. The challenge with project planning tools often occurs when the monitoring process becomes too rigid, which can impede the organic flow of the project's implementation on the ground (Stem et al., 2005; Cameron, 2012). We recommending projects to keep some flexibility in how activities can be carried out, considering planning is done at the conceptualization of the project often with general assumptions, while the reality on the ground could differ. We recommend projects to support their ToC assumptions with evidence and choose their indicators carefully to monitor the change that they want to see. Although SROI framework does not require accurate estimation of monetary values as long it is realistic and consistent, but often the danger is when these data are taken out of SROI context. Other common difficulties in implementing ToC include governance challenges, when the actual output depends on action from stakeholders who are higher up in the management hierarchy, or if the issue is extremely complex and requires a huge amount of effort in order to make a net benefit (Stem et al., 2005; Cameron, 2012; Biggs et al., 2017).

In this case study, the ToC was developed for stakeholders with the inclusion of Asian elephants as stakeholders in the SROI framework. We found the use of SROI can potentially account for invisible values, which can be further developed for wildlife projects by realizing that the society has an intrinsic appreciation of wildlife existence and there are social values when working together with stakeholders (Lingane and Olsen, 2004; Stem et al., 2005; Nicholls et al., 2021). The challenge would be to convert those values in monetary terms. Here, we calculated the monetary value for “in-kind contribution” by stakeholders via their time involvement with the project and extrapolated results from a “willingness to pay” study to quantify the intrinsic value of elephants. There is plenty of room for developing value quantification of ecosystem services provided by elephants, or in having tolerance toward elephants and many more.

The SROI calculations can help projects to reconsider the impact that they are making on the ground, and serve as a basis to justify to donors that the funds invested in the project is worth the social outcomes. However, there are some important caveats to consider, it is generally not encouraged to compare one project with another based on SROI ratios. The SROI is meant to help in monitoring internal progress or changes of the project from time to time. To interpret the SROI ratio for each project, we have to consider the local context, supporting evidence and the overall analysis of what factors that are being compared.

This case study calculated the SROI values for conserving an estimated 135 elephants in the State of Johor. Previously, Saaban et al. (2020) had used population viability analysis to predict that local extinction could happen to this elephant population if artificial removal from the wild continued. Using the intrinsic value of a wild elephant, extrapolated from a study on willingness to pay for a wild elephant's conservation and well-being, the SROI value generated was at least MYR 7.3 million/year for the elephant population in Johor. This is a very conservative estimation, and the intrinsic value calculated for wild elephants could potentially increase as more efforts are poured into conserving the species, higher awareness raised or when additional values such as elephant functions in ecosystem services are accounted for. This SROI value cannot be claimed by the project solely as it requires the involvement of all stakeholders including government agencies, non-governmental organizations, private sectors and communities to play vital roles in ensuring the survival and viability of the elephant population. Hence, the SROI template allows the project proponent to acknowledge the contributions from other stakeholders and present a realistic and transparent assessment to the funder.

We duly acknowledge that the intrinsic value of a wild elephant calculated here is purely an academic exercise and that the existence of any endangered species individuals is deemed priceless by the conservation communities (Soule, 1985) and any concerned citizen. However, in an effort to move the larger society toward supporting biodiversity conservation, increasingly the language of economics is used to justify the need for conservation despite challenges in capturing the complex relationship between nature and people via invisible and intrinsic values in addition to direct and indirect economic benefits (Kareiva and Marvier, 2012; Dasgupta, 2021). Instead of trying to force biodiversity calculations into traditional economic methods, the “Dasgupta Review” highlighted the potential to expand the ability of economic tools to take into account the holistic roles of biodiversity and nature, and their relationship with people (Dasgupta, 2021). But, until the world has fully embraced accounting of ecological footprint and biosphere regeneration (Dasgupta, 2021), we highly recommend our readers to avoid using the intrinsic economic value calculated for elephants outside of SROI context, as there are multiple assumptions used in the calculations and it may wrongly encourage the direct use of cost-benefit analysis to justify development above species survival (Catlin et al., 2013).

We like to emphasize that the real value of the development of ToC through the SROI approach is the ability to value the social (and biodiversity) returns of the conservation project itself, akin to social entrepreneurship, to justify to the funder of the project's necessity (Nicholls et al., 2021). Furthermore, the thinking process that the tools necessitate can help encourage the project proponents to consider thoroughly the value of change they may influence on the ground. The problem tree and SROI framework encourages collaboration with stakeholders to tackle critical issues (Rice et al., 2020), and consider both the positive and negative impact of the project carefully through the inclusion of replacement, displacement and deadweight calculations (Nicholls et al., 2021). By using the SROI framework to monitor the project development, projects can adjust their strategies based on adaptive management and make changes as the project goes along. Project management is often challenging due to the many moving parts and factors often outside of the project executants' control. The ToC and SROI system recommended here are approaches to help visualize the project challenges in a simplified and logical order, to support the design of interventions. The assumptions taken to design the interventions are often crucial, and often reiterations of the planning process (or some parts of it) may be needed at different management levels, with different groups of stakeholders, or at different phases of the project to identify new issues and help verify assumptions.

Project planning tools can help wildlife conservation projects in prioritizing issues to tackle and stakeholders to engage with, in order to achieve its objectives. However, the true value is in the process of deliberation and constructive discussion, which allows thinking out of the box, and building cooperation between stakeholders. Tools like ToC and SROI can provide further justification to donors and convince them on the potential project outcome. We recommend projects to have some flexibility in envisioning and carrying out activities on the ground and to select their project indicators carefully.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethical review and approval was not required for this study as it is not a social survey but a project planning exercise involving all coauthors in this paper.

EPW facilitated and moderated the project planning processes and conceptualized and took the leading role in writing this paper. ACA, NZ, PC, AGQ, JAT, ASM, WHT, LO, MAR, SSD, VP, TWL, OOC, AFA, NH, AT, JW, VL, AZ, MMI, PAP, MTAR, and SS have participated in the planning process or contributed own research, shared feedback, and contributed to this write-up. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Yayasan Sime Darby (NVHU.0001, NVHH.007), Wildlife Reserves Singapore (U0050.54.04), Chester Zoo (C0011.54.04), and National Geographic (NGS86500C-21). The funds management is overseen by the University of Nottingham Malaysia and is audited annually.

AGQ is employed by a certified sustainable oil palm company, and the project is currently working closely with the agriculture communities to promote coexistence with wild elephants. The lead author and the project did not receive any monetary contribution from the agriculture companies.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

We like to thank MEME's funders for all their encouragement and trust in our work. Our appreciation for the support we received from our friends, colleagues, supporters, students, family members, University of Nottingham Malaysia, and the IUCN SSC Asian Elephant Specialist Group. Our utmost gratitude for the opportunities provided for us to contribute toward the conservation of wild Asian elephants and other endangered wildlife.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcosc.2021.682590/full#supplementary-material

Abdul Kadir, M. A. B., and Mhd Sarif, S. (2016). Social entrepreneurship, social entrepreneur and social enterprise:a review of concepts, definitions and development in Malaysia. JEEIR 4:51. doi: 10.24191/jeeir.v4i2.9086

Ahmad Zafir, A. W., and Magintan, D. (2016). Historical review of human-elephant conflict in Peninsular Malaysia. J. Wildlife Parks 31, 1–19. Available online at: http://myagric.upm.edu.my/id/eprint/14460

Alfred, R., Ambu, L., Nathan, S. K. S. S., and Goossens, B. (2011). Current status of Asian elephants in Borneo. Gajah 35, 29–35. Available online at: https://www.asesg.org/PDFfiles/2012/35-29-Alfred.pdf

Alvarez, S., Douthwaite, B., Thiele, G., et al. (2010). Participatory impact pathways analysis: a practical method for project planning and evaluation. Dev. Pract. 20, 946–958. doi: 10.1080/09614524.2010.513723

Baynham-Herd, Z., Redpath, S., Bunnefeld, N., et al. (2018). Conservation conflicts: behavioural threats, frames, and intervention recommendations. Biol. Conserv. 222, 180–188. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2018.04.012

Biggs, D., Cooney, R., Roe, D., Dublin, H. T., Allan, J. R., Challender, D. W., et al. (2017). Developing a theory of change for a community-based response to illegal wildlife trade. Conserv. Biol. 31:8. doi: 10.1111/cobi.12796

Cameron, J. (2012). The challenges for monitoring and evaluation in the 1990s. Project Appr. 8, 91–96. doi: 10.1080/02688867.1993.9726893

Catlin, J., Hughes, M., Jones, T., Jones, R., and Campbell, R. (2013). Valuing individual animals through tourism: science or speculation? Biol. Conserv. 157, 93–98. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2012.07.022

Clements, R., Rayan, D. M., Ahmad Zafir, A. W., Venketraman, A., Alfred, R., Payne, J., et al. (2010). Trio under threat: can we secure the future of rhinos, elephants and tigers in Malaysia? Biodiv. Conserv. 2010, 115–1136. doi: 10.1007/s10531-009-9775-3

de la Torre, J. A., Lechner, A. M., Wong, E. P., Magintan, D., Saaban, S., and Campos-Arceiz, A. (2019). Using elephant movements to assess landscape connectivity under Peninsular Malaysia's central forest spine land use policy. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 1:e133. doi: 10.1111/csp2.133

de la Torre, J. A., Wong, E. P., Lechner, A. M., Zhulaika, N., Zawawi, A., Abdhul-Patah, P., et al. (2021). There will be conflict – agricultural landscapes are prime, rather than marginal, habitats for Asian elephants. Anim. Conserv. 2021:acv.12668. doi: 10.1111/acv.12668

Department of Statistics Malaysia Official Portal (2020). Current Population Estimates, Malaysia, 2020. Available online at: https://www.dosm.gov.my/v1/index.php?r=column/cthemeByCat&cat=155&bul_id=OVByWjg5YkQ3MWFZRTN5bDJiaEVhZz09&menu_id=L0pheU43NWJwRWVSZklWdzQ4TlhUUT09 (accessed March 15, 2021).

Department of Town and Country Planning (2009). Final Report Central Forest Spine 1: Master Plan for Ecological Linkages. Malaysia: Government of Malaysia.

Department of Town and Country Planning (2016). 3rd National Physical Plan. Putrajaya, Kuala Lumpur: Government of Malaysia.

Economic Planning Unit Johor (2016). Johor Sustainability Policy 2017-2021. Johor, Malaysia: Economic Planning Unit Johor.

Fernando, P., and Pastorini, J. (2011). Range-wide status of Asian elephants. Gajah 35, 15–20. Available online at: https://www.asesg.org/PDFfiles/2012/35-15-Fernando.pdf

Golini, R., Landoni, P., and Kalchschmidt, M. (2018). The adoption of the logical framework in international development projects: a survey of non-governmental organizations. Impact Assess. Project Appraisal 36, 145–154. doi: 10.1080/14615517.2017.1354643

Government of Malaysia (2012). National Policy on Biological Diversity 2016-2025. Putrajaya: Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment.

Guérin, M., Lim, T., Tan, A., and Campos-Arceiz, A. (2017). A favourable shift towards public acceptance of wildlife conservation in Peninsular Malaysia: comparing the findings of the Wild Life Commission of Malaya (1932). with a recent survey of attitudes in Kuala Lumpur and Taiping, Perak. Malayan Nat. J. 21–31. Retrieved from: https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01845024/

Hatta, Z. A., and Ali, I. (2013). Poverty reduction policies in Malaysia: trends, strategies and challenges. ACH 5:48. doi: 10.5539/ach.v5n2p48

Hughes, A. C. (2017). Understanding the drivers of Southeast Asian biodiversity loss. Ecosphere 8:e01624. doi: 10.1002/ecs2.1624

IUCN (2019). “Elephas maximus,” in The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, eds C. Williams, S. K. Tiwari, V. R. Goswami, S. de Silva, A. Kumar, N. Baskaran, et al., 2020:e.T7140A45818198.

Kareiva, P., and Marvier, M. (2012). What is conservation science? BioScience 62, 962–969. doi: 10.1525/bio.2012.62.11.5

Law, Y. H. (2020). Forest Loss Under Whose Watch? Macaranga.org.

Lim, T. W. (2018). Human-Elephant Relations in Peninsular Malaysia. Ph.D. thesis, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, United Kingdom.

Lingane, A., and Olsen, S. (2004). Guidelines for social return on investment. California Manag. Rev. 46, 116–135. doi: 10.2307/41166224

Lydekker, R. (1914). The Malay Race of the Indian Elephant Elephas maximus hirsutus*. Proc. Zool. Soc. Lond. 84, 285–288. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7998.1914.tb07036.x

Mahajan, S. L., Glew, L., Rieder, E., et al. (2019). Systems thinking for planning and evaluating conservation interventions. Conservat. Sci. Prac. 1:44. doi: 10.1111/csp2.44

Mahmood, T., Vu, T. T., Campos-Arceiz, A., Akrim, F., Andleeb, S., Farooq, M., et al. (2021). Historical and current distribution ranges and loss of mega-herbivores and carnivores of Asia. PeerJ 9:e10738. doi: 10.7717/peerj.10738

Manfredo, M. J., Teel, T. L., Berl, R. E. W., Bruskotter, J. T., and Kitayama, S. (2021). Publisher correction: societal value shift in favour of biodiversity conservation in the United States. Nature Sustain. 4, 323–330. doi: 10.1038/s41893-020-00675-2

Maniam, A., and Singaravelloo, K. (2015). Impediments to Linking Forest Islands to Central Forest Spine in Johor, Malaysia. IJSSH 5, 22–28. doi: 10.7763/IJSSH.2015.V5.415

Miettinen, J., Shi, C., and Liew, S. C. (2011). Deforestation rates in insular Southeast Asia between 2000 and 2010: deforestation in insular Southeast Asia 2000–2010. Glob. Change Biol. 17, 2261–2270. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2011.02398.x

Nagulendran, K., Padfield, R., Aziz, S. A., Amir, A. A., Rahman, A. R. A., Latiff, M. A., et al. (2016). A multi-stakeholder strategy to identify conservation priorities in Peninsular Malaysia. Cogent Environ. Sci. 21:1254078. doi: 10.1080/23311843.2016.1254078

Nicholls, J., Lawlor, E., Neitzert, E., and Goodspeed, T. (2021). A Guide to Social Return on Investment. The SROI Network accounting for value.

Ong, L. (2021). The Ecological Functions of Asian Elephants in the Sundaic Rainforest: Herbivory and Seed Dispersal. Ph.D. thesis, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, United Kingdom. Available online at: http://eprints.nottingham.ac.uk/63904/

Poh, L. Y., and Mohd Shahwahid, H. O. (2008). Economic Value of Forest in Elephant Conservation, Peninsular Malaysia. Kuala Lumpur: Forestry Department Peninsular Malaysia.

Ponnusamy, V., Chackrapani, P., Lim, T. W., Saaban, S., and Campos-Arceiz, A. (2016). Farmers' perceptions and attitudes towards government-constructed electric fences in Peninsular Malaysia. Gajah 45, 4–11. Available online at: https://www.asesg.org/PDFfiles/2016/Gajah%2045/45-04-Ponnusamy.pdf

Quilter, A. G. (2019). Developing an Evidence Based Policy and Protocol for Human Elephant Conflict in Oil Palm Plantations: A Case Study of Sime Darby Plantation Berhad. MRes thesis, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, United Kingdom.

Rice, W. S., Sowman, M. R., and Bavinck, M. (2020). Using Theory of Change to improve post-2020 conservation: a proposed framework and recommendations for use. Conservat. Sci. Prac. 2:301. doi: 10.1111/csp2.301

Ripple, W. J., Chapron, G., López-Bao, J. V., et al. (2017). Conserving the World's Megafauna and biodiversity: the fierce urgency of now. BioScience 2017:biw168. doi: 10.1093/biosci/biw168

Saaban, S., Othman, N., Yasak, M. N., Mohd Nor, B, Zafir, A., Campos-Arceiz, A., et al. (2011). Current status of Asian elephants in Peninsular Malaysia. Gajah 35, 67–75. Available online at: https://www.asesg.org/PDFfiles/2012/35-67-Saaban.pdf

Saaban, S., Yasak, M. N., Gumal, M., Oziar, A., Cheong, F., Shaari, Z., et al. (2020). Viability and management of the Asian elephant (Elephas maximus) population in the Endau Rompin landscape, Peninsular Malaysia. PeerJ 8:e8209. doi: 10.7717/peerj.8209

Saifullah, M. K., Masud, M. M., and Kari, F. B. (2021). Vulnerability context and well-being factors of Indigenous community development: a study of Peninsular Malaysia. AlterNative. 17, 94–105. doi: 10.1177/1177180121995166

Stem, C., Margolius, R., Salafsky, N., and Brown, M. (2005). Monitoring and evaluation in conservation: a review of trends and approaches. Conserv. Biol. 19, 209–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2005.00594.x

Sukumar, R. (2003). The Living Elephants: Evolutionary Ecology, Behavior, and Conservation. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Tan, A. S. L. (2016). Mapping the Current and Past Distribution of Asian Elephants (Elephas maximus) and Human-Elephant- Conflict (HEC) in Human-Occupied-Landscapes of Peninsular Malaysia.

Tan, A. S. L., de la Torre, J. A., Wong, E. P., Thuppil, V., and Campos-Arceiz, A. (2020). Factors affecting urban and rural tolerance towards conflict-prone endangered megafauna in Peninsular Malaysia. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 23:e01179. doi: 10.1016/j.gecco.2020.e01179

Taylor, B., Chapron, G., Kopnina, H., Orlikowska, E., Gray, J., and Piccolo, J. J. (2020). The need for ecocentrism in biodiversity conservation. Conserv. Biol. 34, 1089–1096. doi: 10.1111/cobi.13541

Terborgh, J., Davenport, L. C., Ong, L., and Campos-Arceiz, A. (2018). Foraging impacts of Asian megafauna on tropical rain forest structure and biodiversity. Biotropica 50, 84–89. doi: 10.1111/btp.12488

Varkkey, H., Tyson, A., and Choiruzzad, S. A. B. (2018). Palm oil intensification and expansion in Indonesia and Malaysia: environmental and socio-political factors influencing policy. Forest Poli. Econ. 92, 148–159. doi: 10.1016/j.forpol.2018.05.002

von Rintelen, K., von Arida, E., and Häuser, C. (2017). A review of biodiversity-related issues and challenges in megadiverse Indonesia and other Southeast Asian countries. RIO 3:e20860. doi: 10.3897/rio.3.e20860

Wadey, J. (2020). Movement Ecology of Asian Elephants in Peninsular Malaysia. Ph.D. thesis, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, United Kingdom. Available online at: http://eprints.nottingham.ac.uk/60708/

Wadey, J., Beyer, H. L., Saaban, S., Othman, N., Leimgruber, P., Campos-Arceiz, A., et al. (2018). Why did the elephant cross the road? The complex response of wild elephants to a major road in Peninsular Malaysia. Biol. Conserv. 218, 91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2017.11.036

Wong, E. P. (2018). Non-Invasive Monitoring of Stress in Wild Asian Elephant (Elephas maximus) in Peninsular Malaysia. Ph.D. thesis, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, United Kingdom. Available online at: http://eprints.nottingham.ac.uk/47810/

Wong, E. P., Yon, L., Walker, S. L., Mena, A. S., Wadey, J., Othman, N., et al. (2018). The elephant who finally crossed the road – significant life events reflected in faecal hormone metabolites of a Wild Asian Elephant. Gajah 48, 4–11. Available online at: https://www.asesg.org/PDFfiles/2018/48-04-Wong.pdf

Keywords: human-elephant conflict, coexistence, theory of change, social return of investment, Asian elephant, Elephas maximus, Malaysia

Citation: Wong EP, Campos-Arceiz A, Zulaikha N, Chackrapani P, Quilter AG, de la Torre JA, Solana-Mena A, Tan WH, Ong L, Rusli MA, Sinha S, Ponnusamy V, Lim TW, Or OC, Aziz AF, Hii N, Tan ASL, Wadey J, Loke VPW, Zawawi A, Idris MM, Abdul Patah P, Abdul Rahman MT and Saaban S (2021) Living With Elephants: Evidence-Based Planning to Conserve Wild Elephants in a Megadiverse South East Asian Country. Front. Conserv. Sci. 2:682590. doi: 10.3389/fcosc.2021.682590

Received: 18 March 2021; Accepted: 21 May 2021;

Published: 14 July 2021.

Edited by:

Alexandra Zimmermann, University of Oxford, United KingdomReviewed by:

Nurzhafarina Othman, Persatuan Pemuliharaan Biodiversiti Seratu Aatai Sabah, MalaysiaCopyright © 2021 Wong, Campos-Arceiz, Zulaikha, Chackrapani, Quilter, de la Torre, Solana-Mena, Tan, Ong, Rusli, Sinha, Ponnusamy, Lim, Or, Aziz, Hii, Tan, Wadey, Loke, Zawawi, Idris, Abdul Patah, Abdul Rahman and Saaban. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ee Phin Wong, RWVQaGluLldvbmdAbm90dGluZ2hhbS5lZHUubXk=; ZWVwaGluQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.