- 1Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, United States

- 2Program in Biology, Faculty of Science, Ubon Ratchathani Rajabhat University, Ubon Ratchathani, Thailand

Interest in wildlife ecotourism is increasing but many studies have identified detrimental effects making it unsustainable in the long run. We discuss a relatively new wildlife ecotourism event where tourists visit Ubon Ratchathani, Thailand to witness a mass migration of freshwater shrimp that emerge from the water and move across land known as “shrimp parading.” As this has been developed into a tourist event, the number of migrating shrimp have declined, suggesting that it may be unsustainable as currently practiced. We used a questionnaire to ask how locals, tourists, and stakeholders value the shrimp and their willingness to change their behavior to mitigate anthropogenic impacts. We found that three groups of participants were not aware of potential negative impacts to the shrimp from tourism. Locals valued the tourism in terms of the economy, culture, and environment less than tourists and stakeholders. The local government applied a top-down approach to manage this tourism without a fundamental understanding of the shrimp's biology, impacts of tourists on the shrimp, or the various stakeholder perceptions. We discuss the problems and possible solutions that may be employed to help sustain this fascinating biological and cultural event and propose a framework to develop a sustainable wildlife ecotourism management plan. This case study serves as a model for others developing wildlife watching ecotourism, especially in developing countries.

Introduction

The tourism industry is one of the world's largest industries, which before the COVID-19 pandemic, contributed over 8.9 trillion US dollars of world gross domestic product (The World Travel Tourism Council, 2019). Among the types of tourism, ecotourism, a type of nature-based tourism, has become increasingly popular since the late twentieth century (Buckley, 1998; Hawkins and Lamoureux, 2001).

Ecotourism is defined as responsible travel to natural areas which aims to conserve the environment as well as to sustain the well-being of local people (The International Ecotourism Society, 2015). Ecotourism may have both socioeconomic and environmental benefits through conservation. However, the success of using ecotourism as a conservation tool depends on many factors (Krüger, 2005). For example, studies of sea turtle ecotourism in Brazil and Peru revealed that different conditions might give different results. In Brazil, the economic benefits of locals are associated with the success of conservation outcomes. On the other hand, in Peru, both local participation in ecotourism management and the economic benefits of locals drive the success of conservation (Stronza and Pegas, 2008). Even though management is a key to successful conservation and sustainable ecotourism, the understanding of fundamental knowledge of each system and perceptions from three important elements of ecotourism system—tourists, ecotourism stakeholders (i.e., business owners), and locals (residents)—are essential to create positive conservation outcomes (Murphy and Murphy, 2004; Sánchez Cañizares et al., 2016).

Relatively little wildlife ecotourism has traditionally focused on invertebrates, animals that have a vital role in their ecosystem (Huntly et al., 2005). However, invertebrate ecotourism is expanding. Examples of invertebrate ecotourism (reviewed in Lemelin, 2013) includes the mass aggregation of the New Zealand glowworms (Arachnocampa luminosa) in a cave in New Zealand (Hall, 2012), and firefly watching tours in Amphawa, Samut Songkhram, Thailand (Nurancha et al., 2013). Moreover, when invertebrates exhibit mass migration, they could stimulate more attention from tourists (Mavhunga, 2011). This can be seen in the spectacular annual migration of monarch butterflies (Danaus plexippus) in the United States (Whelan, 2012), and the mass migration of red crabs (Gecarcoidea natalis) on Christmas Island, Australia (Back From The Brink, 2019). Several developing countries in tropical regions, where invertebrate biodiversity is high, have much potential to develop invertebrate tourism. Therefore, understanding how locals, tourists, and stakeholders in different areas think about their resources is an essential part for developing sustainable ecotourism management plans (Sánchez Cañizares et al., 2016).

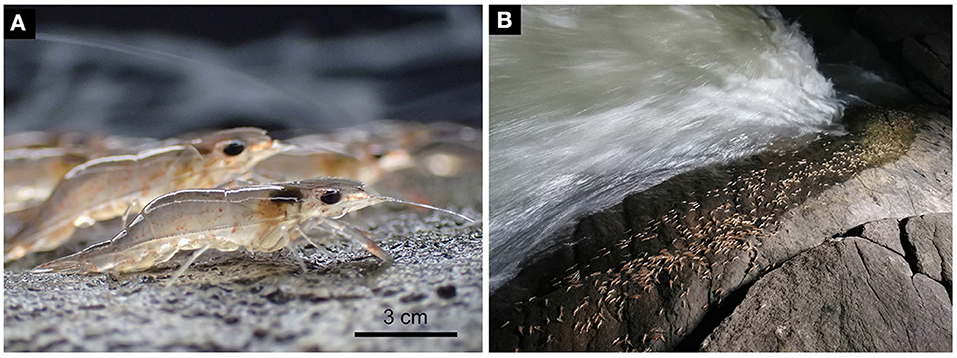

“Shrimp Watching” tourism is a type of ecotourism that was promoted by the Tourism Authority of Thailand (TAT) under the “Amazing Thailand” campaign from 1998 to 1999. This event has been organized annually at Lamduan rapids, Nam Yuen district, Ubon Ratchathani, Thailand by the Nature and Wildlife Education Center Ubon Ratchathani. In September of each year, tourists from all around Thailand and other countries in Southeast Asia travel to this place to witness the unique mass migration of freshwater shrimp known as “Parading Shrimp” (Figure 1; Supplementary Video 1). This natural phenomenon occurs at night when millions of freshwater shrimp collectively climb out of the Lamduan rapids and start to parade on land toward the headwater in the Thailand-Cambodia border. Research from Hongjamrassilp et al. (2020) reveals that the shrimp leave the water to escape the strong water current in the rapids. They do not perform this unique migration for reproduction, as observed in other riverine animals, such as salmon.

Figure 1. (A) A close-up photo of the parading shrimp while parading on land. (B) The mass migration on land of the parading shrimp at Lamduan rapids, Ubon Ratchathani, Thailand heading toward the headwater in Dângrêk Mountains in Thai-Cambodian natural border. Photos by Watcharapong Hongjamrassilp.

Over the past 20 years, locals in Nam Yuen district have developed novel cultural practices around the shrimp (e.g., food, folk songs, and dances) indicating that the shrimp have become integrated into their culture (Figure 2). However, observations from rangers in the Nature and Wildlife Education Center, suggest that shrimp populations have decreased during the past 5 years (Wassana Maiphrom, pers. comm.). Indeed, (Hongjamrassilp and Blumstein, under review) report reveals that the decrease in the number of parading shrimp is associated with the presence of tourists. The decline of shrimp may ultimately influence the tourism business, the cultures that have been developed, as well as other emerging cultures and traditions.

Figure 2. (A) Statue of parading shrimp at the tourism site. (B) Mascot design competition event for primary to high school students organized by the Nature and Wildlife Education Center at Ubon Ratchathani with the aim to increase the awareness of anthropogenic disturbances on parading shrimp. (C) Folk dance telling the story about the parading shrimp and how to conserve them. (D) A group of tourists watching the parading shrimp climb out of the river at night. Photo by (A,B,D) Watcharapong Hongjamrassilp and (C) the Nature and Wildlife Education Center at Ubon Ratchathani.

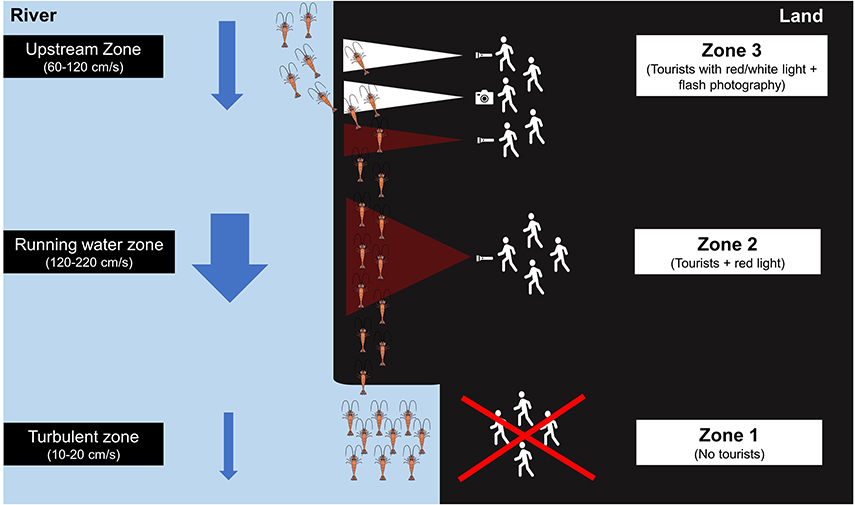

(Hongjamrassilp and Blumstein, under review) discovered that light from tourist's flashlights is the main factor that might lead to the decrease in parading shrimp during the tourist season. They found that red and yellow lights affect the shrimp while migrating on land less than other colors. Therefore, they suggested an evidenced-based solution to mitigate the anthropogenic disturbances on the shrimp would involve creating three different zones, in which each zone allows tourists would be permitted to use different light colors while shrimp watching (Figure 3). However, to create and apply an effective management plan, we need to understand how participants in this tourism industry understand the problems, value their resources, and the degree to which they are willing to change their behaviors for the good of the shrimp.

Figure 3. The management plan proposed by Hongjamrassilp and Blumstein (under review). Because the shrimp respond to red light less than other light colors, they proposed to divide the tourist's site into three zones. At zone 1, tourists are not allowed to be here because light could inhibit the shrimp from emerging from the river. At zone 2, tourists can use personal flashlights. However, they need to use red light instead of white light because white light can cause the shrimp to walk back to river where they are washed downstream. Light color can be modified by covering the tourist's personal flashlight with a piece of red cellophane. Finally, at zone 3, tourists can use both red and white light and flash photography while watching the shrimp because it is safe for the shrimp to re-enter the water. The blue arrows represent water velocity.

This study had three aims. First, to understand the perceptions of locals, tourists, and stakeholders toward Shrimp Watching tourism. Second, to generate ideas about how to improve and balance the demands of users and the environment. And, third, to identify the potential factors that might negatively affect the tourism development in this area.

Methods

Interviews About the Development of Shrimp Watching Tourism in Thailand

We interviewed the director of the Nature and Wildlife Education Center at Ubon Ratchathani who has been responsible for organizing and planning the Shrimp Parading festival since 2012 and other locals in Nam Yuen district where we conducted the survey study. The main interview questions included: (1) How was Shrimp Watching tourism developed?, (2) What is the present management plan? (3) Which locals have participated in this tourism?, and (4) What are the local beliefs and cultures related to the parading shrimp? We summarize the interviews in the results section. Because information regarding the development of Shrimp Watching tourism and the locals understanding about parading shrimp have never been documented, these interviews provide novel information.

Survey Regarding Attitudes of Locals, Tourists, and Stakeholders Toward Shrimp Watching Tourism

Questionnaire Design

Locals, tourists, and stakeholders who are directly involved with an ecotourism industry are key players in conservation and management. Understanding their thoughts about parading shrimp will allow us to develop a sustainable plan for ecotourism management. We conducted a survey using a questionnaire. We constructed the questionnaire following the suggestions from De Vaus (2013; Box 7.2). The questions were designed to mainly understand:

(1) How much do participants know and how concerned are they about parading shrimp?

(2) How much do participants understand ecological, cultural, and economic values of parading shrimp?

(3) How much do the participants know about parading shrimp's threats and their willingness to change their behavior for the shrimp?

We surveyed three main groups: (1) locals, who do not directly profit from ecotourism, (2) tourists, and (3) stakeholders (business owners), who directly profit from ecotourism, such as tourist guides, and local entrepreneurs who work at the tourist site. The questionnaire consisted of four parts. The first part was used to describe the groups and collect demographic data. The second part was used to identify the understanding and basic knowledge of the parading shrimp including concerns about the present status of the parading shrimp population. The third part was used to identify how people valued parading shrimp in terms of economics, environment, and culture. The fourth and final part was used to understand how much people knew about the threats for the parading shrimp and are willing to modify their behavior for the shrimp.

Questions were posed using a 5-point Likert-scale. We tested the reliability and internal consistency of the Likert-scale question with Cronbach's alpha coefficient (Cronbach, 1951). Responses to Likert-scale statements showed an acceptable level of internal consistency (Cronbach's α = 0.72) meaning that the multiple Likert-scale questions were reliable. This study provides vital information to help us understand the attitudes toward parading shrimp in three key parties that will ultimately be affected by the development of a sustainable management plan.

Data Collection

We conduct the survey study in September of 2019 at the tourist site in Nam Yuen district, Ubon Ratchathani, Thailand (14° 26′ 07.0″ N; 105 ° 06′ 17.0″ E) and in nine villages nearby the tourism site (Supplementary Document). We spent about 3 h interviewing the director of the Nature and Wildlife Education Center at Ubon Ratchathani to learn about the development of Shrimp Watching tourism in Thailand. We spent about 40–60 min interviewing each of three old locals (>40 years) from Nhong Phoad village (N = 1) and Kae Don village (N = 2). These two villages are the two locations where the shrimp leave the water.

For the questionnaire, we collected data by interviewing each participant in person. Before the interview, we asked for permission from participants and told them about their conditions for participation which were approved by the UCLA Institutional Review Board (Protocol #18-000944). We spent no more than 15 min interviewing each participant. For tourists (N = 133), we haphazardly selected subjects before they went to watch the parading shrimp. For, stakeholders (N = 35), we interviewed local vendors, tour guides, and hotel staff in Nam Yuen district where the parading shrimp were. For locals (N = 117), we went to nine villages located around the tourist site in Nam Yuen district and haphazardly selected 10–13 participants per village to interview. Since most locals spoke neither Thai nor English, we hired local translators to help conduct the interviews.

Data Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to describe the participants' demographic data. For the Likert-scale questions, we used the Kruskal-Wallis test to test for differences in the mean rank of each question among three different study groups (locals, tourists, and stakeholders). We conducted multiple comparisons using a Bonferroni correction which made the new critical p-value = 0.017 (0.05/3). All data analysis were conducted in R 4.0.2 (R Core Team, 2020).

Results

History of Shrimp Watching Tourism Development in Thailand

The Development of Shrimp Watching Tourism

Shrimp Watching tourism (or the Shrimp Parading festival) was first promoted as nature-based tourism under the “Amazing Thailand” campaign in 1998–1999 when the federal government aimed to stimulate the tourism economy. The former director named the phenomenon of shrimp walking on land “Shrimp Parading” because he thought that this natural phenomenon resembles the parading activity in humans. Since 1999, the director of the Nature and Wildlife Education Center at Ubon Ratchathani has been replaced several times resulting in inconsistent management. However, from 1999 to the present, every management decision for this tourist site has been decided solely by the government staff. Locals and stakeholders have played no role in developing any ecotourism management plan.

What Is the Present Management Plan?

The present management plan (from 2012–present) includes organizing the government staff members to take care of the tourist's safety during the tourist season and educating tourists with information posters about the shrimp parading and how should tourists behave while watching the shrimp. The only management plan that focuses on the mitigation of anthropogenic threats on the shrimp is the prohibition of harvesting the parading shrimp in the tourist site.

Which Locals Have Participated in This Tourism?

From 2012–present, locals and schoolchildren from many villages around the tourist site have been invited to join the opening ceremony of the Shrimp Parading festival. Students have been involved in designing a shrimp mascot costume to represent the environmental issues in that area (Figure 2B). Locals who are not students are invited to sell their products (e.g., local fruits, local foods, and textiles) at the tourist site.

Local Beliefs and Cultures Related the Shrimp

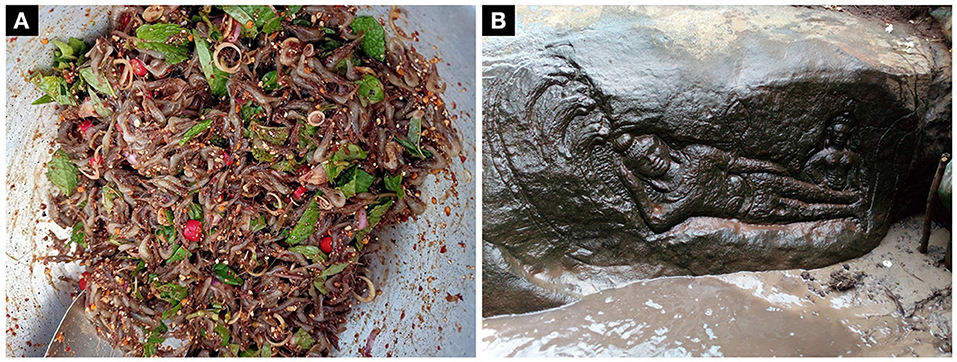

Long before 1998, locals knew about the terrestrial shrimp migration. They caught the parading shrimp for food and developed several recipes. One of the most popular is Koi-Kung (Thai:  ), the local traditional Northeastern Thai food which is made from raw shrimp marinated with lime juice (Figure 4A). Moreover, older residents believed that the shrimp parade to the headwater in Dângrêk Mountains to worship the Hindu god Vishu (or Phra Narai) (Figure 4B). Recently, locals composed a song about the present status and conservation of parading shrimp. Together, these actions illustrate the development of local culture associated with shrimp.

), the local traditional Northeastern Thai food which is made from raw shrimp marinated with lime juice (Figure 4A). Moreover, older residents believed that the shrimp parade to the headwater in Dângrêk Mountains to worship the Hindu god Vishu (or Phra Narai) (Figure 4B). Recently, locals composed a song about the present status and conservation of parading shrimp. Together, these actions illustrate the development of local culture associated with shrimp.

Figure 4. (A) Koi-Kung, a local Northeastern Thai dish, made from parading shrimp. (B) Bas relief carving of “Reclining Vishnu Lintel on the Serpent Ananta (Phra Narai Lintel)” carved under the Lam Dom Yai river. This carving can be seen only in the dry season (March –April) when the river dries up. Photo by (A) Prapun Traiyasut and (B) the Nature and Wildlife Education Center at Ubon Ratchathani.

Survey Regarding Attitudes of Locals, Tourists, and Stakeholders Toward Shrimp Watching Tourism

Participants Socio-Demographic Characteristics

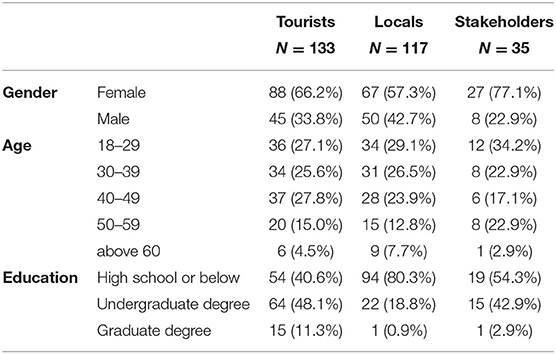

Of the 285 survey participants, 182 (63.85%) were women and 103 (36.15%) were men (Table 1). Within each group, the sex ratio of the locals was around 1:1 (female: male), while the tourist group was 2:1, and the stakeholder group was 3:1. Most of the participants were between 18 and 49 years. In the tourist and stakeholder groups, most of the respondent's highest education was high school (40.6% for tourists and 54.3% for stakeholders) and undergraduate degree (48.1% for tourists and 42.9% for stakeholders), while the majority of local's highest degree was high school (80.3%) (Table 3). Participants learned about the parading shrimp from their friends and family (57%), social media (23%), television news (15%), newspapers (3%), and other ways (2%).

How Much Do Participants Know About and Have Concerns for Parading Shrimp?

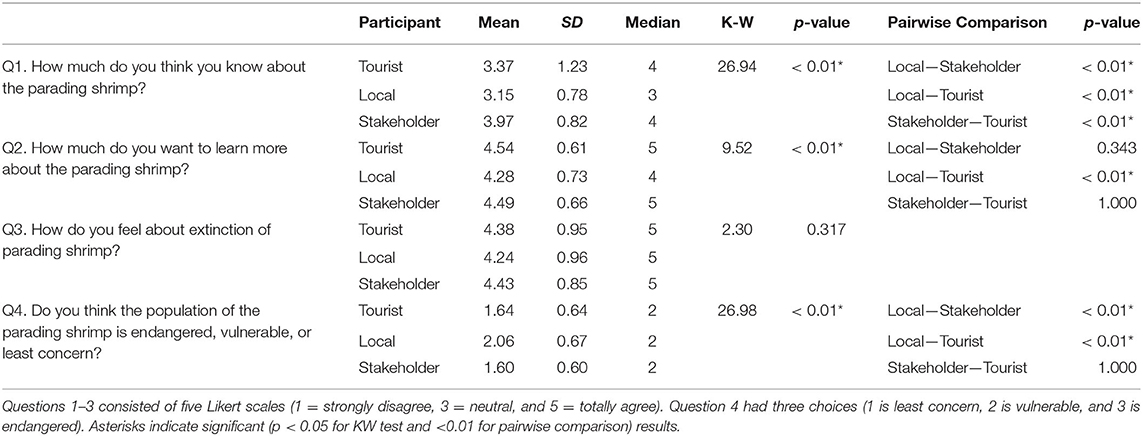

All three groups of participants felt neutral about their knowledge regarding the parading shrimp, but stakeholders were likely to have more confidence about their knowledge than tourists, and locals (P < 0.01; Table 2 Question 1). They also would like to learn more about the parading shrimp. However, tourists would like to learn more about the parading shrimp than locals (P < 0.001; Table 2 Question 2). Most participants were aware that the parading shrimp population was vulnerable. Nevertheless, tourists and stakeholders were more aware of this vulnerability than locals (P < 0.01; Table 2 Question 4). Overall, locals, tourists, and stakeholders were all very concerned about local extinction (of the parading shrimp (P > 0.05; Table 2 Question 3).

Table 2. Summary of participants' knowledge about the parading shrimp, their awareness, and their willingness to learn more about the shrimp.

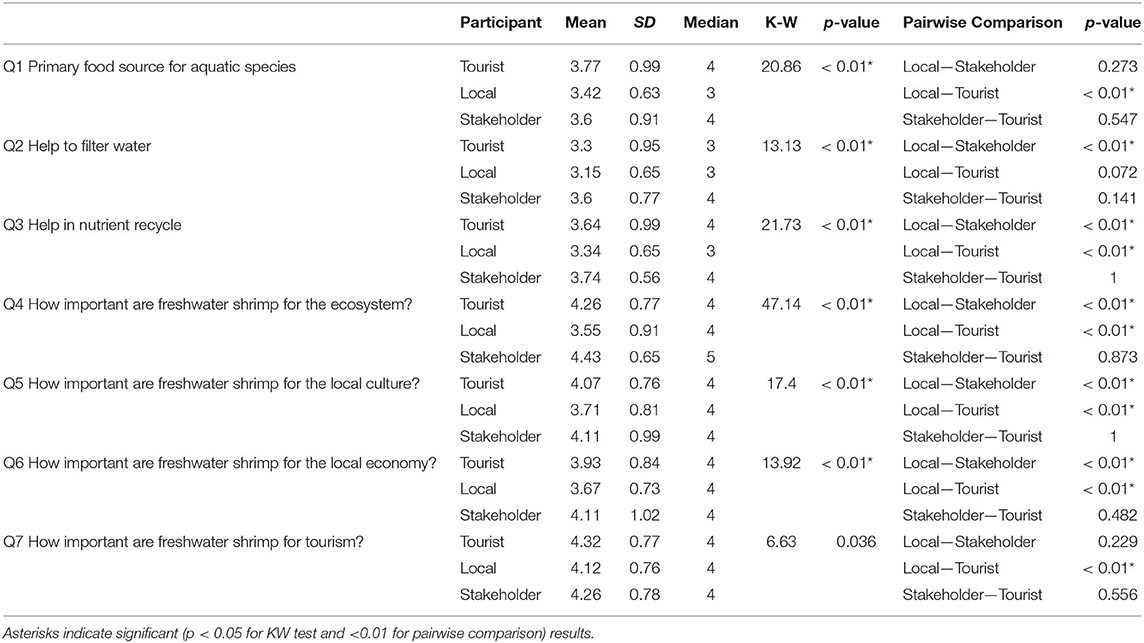

How Much Do Participants Understand Ecological, Cultural, and Economic Values of Parading Shrimp?

All three groups of participants have a fair level of knowledge regarding the roles of the parading shrimp in the freshwater ecosystem (Table 3; Questions 1–3). They all believed that the shrimp play potentially important roles in freshwater ecosystems, are part of local cultures, and important to the local economy. However, locals agreed less to this statement than tourists and stakeholders (P < 0.01; Table 3; Questions 4–6). Locals agreed that shrimp were important for tourism, but when asked about the local economy, locals felt neutral about the role of the shrimp in the local economy (Table 3; Questions 6–7). This may reflect the fact that locals have not been actively involved in the shrimp ecotourism, and that they do not economically benefit from this ecotourism.

Table 3. Summary of participants understanding of the ecological roles and values of the parading shrimp (1 = strongly disagree, 3 = neutral, and 5 = totally agree).

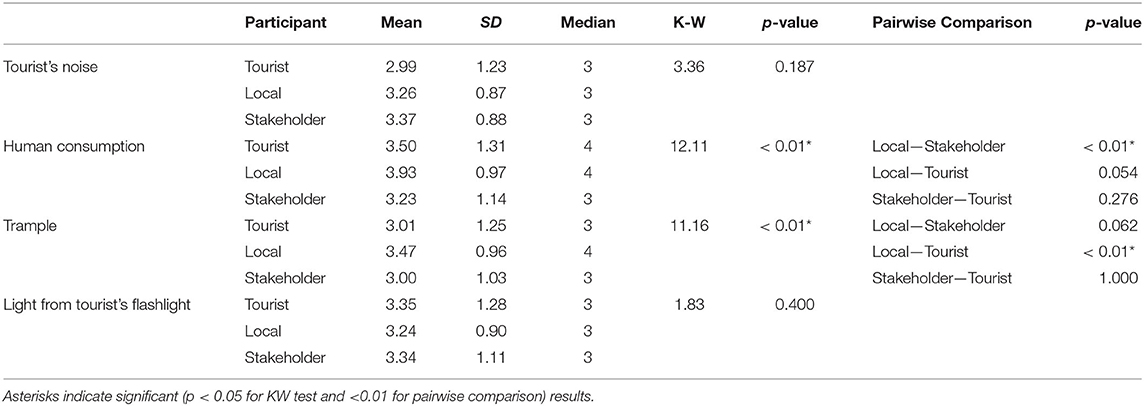

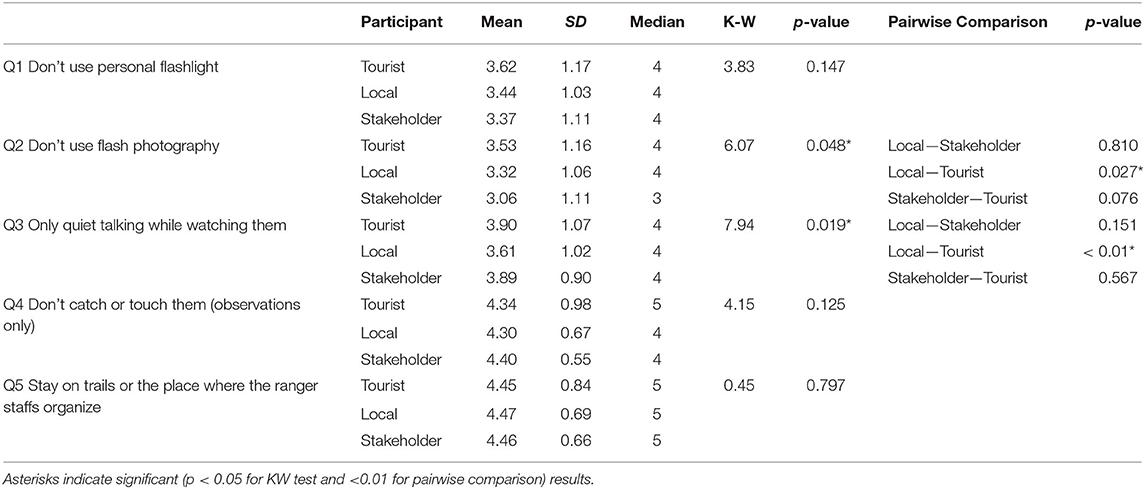

How Much Do the Participants Know About Parading Shrimp's Threats and How Willing Are They to Change Their Behavior for the Shrimp?

Few interviewees knew about the threats to the parading shrimp, and almost no one knew that tourist's lights were a major threat (Table 4). Locals realized that human consumption can harm the shrimp population and trampling on the shrimp might be a threat; by contrast tourists and stakeholders felt neutral about these actions (Table 4). Moreover, most participants responded positively toward adjusting their behavior to help the shrimp by staying on the trail or designed areas and not touching the shrimp. They felt neutral about being quiet, not using a personal flashlight, and not using flash photography while watching the shrimp parade (Table 5).

Table 4. Summary of participant's awareness of the threats to parading shrimp (1 = strongly disagree, 3 = neutral, and 5 = totally agree).

Table 5. Summary of participants' willingness to change their behavior to help the parading shrimp (1 = strongly disagree, 3 = neutral, and 5 = totally agree).

Discussion

Invertebrates play several essential roles in ecosystem; however, they are largely ignored by public especially in the ecotourism sector (Huntly et al., 2005). One of the reasons is that they are not charismatic like birds and mammals (Clark and May, 2002). Furthermore, invertebrates have been viewed as an invasive species to humans and usually are eradicated without animal welfare regulation (Clark, 2015). Several efforts have tried to promote invertebrates as flagship species for conservation or as a focus of ecotourism such as marine invertebrates (Veríssimo et al., 2012), local insects (Barua et al., 2012; Schlegel et al., 2015), Queen Alexandra's birdwing (Ornithoptera alexandrae) (Cranston, 2010), and fireflies (Fallon et al., 2019; Lewis et al., 2020). However, with few exceptions, the effort has rarely been successful. Our research demonstrates that tourists are interested in a small freshwater shrimp that engage in mass migration and thus this is one of few examples of an ecotourism event focused on an invertebrate.

We suggest that these freshwater shrimp in Ubon Ratchathani, Thailand could be used as a flagship species for both ecotourism and conservation. Schlegel et al. (2015) suggest that local insects have the potential to be used as flagship species for conservation in Switzerland. To increase the conservation value, information regarding local insects should be included in primary school curriculum because this is when students pay most attention to their local environment and biodiversity (Lindemann-Matthies, 2006; Jaun-Holderegger, 2012). Therefore, we suggest the educational staff in Ubon Ratchathani create curriculum that uses the parading shrimp and their unique migratory behavior to teach primary school students (Wolff and Skarstein, 2020). This should include information about shrimp biology, their ecological roles, and the roles of shrimp in their local culture and local economy (e.g., through ecotourism).

Following the first publication (in November 2020) that described the Thai parading shrimp, there were a number of high-profile international press reports such as The New York Times, National Geographic, and Smithsonian Magazine (Buehler, 2020; Fox, 2020; Preston, 2020). Hence, Macrobrachium shrimp might have potential to serve as a flagship species for freshwater conservation since they have relatives on every continent except Antarctica and Europe that engage in similar behavior (Holthuis and Ng, 2010; Hongjamrassilp et al., 2020). More investigation into this is warranted.

Concerns regarding adverse effects of technology on animal-based tourism have increased together with the exponential improvement of technology (Pacheco, 2018; Essen et al., 2020). In our case study, we found that light from flashlight and mobile phones that tourists use force the shrimp to walk back to the river which results in them getting washed downstream. The consequence of this action has not been well-studied but have been hypothesized that the shrimp might end up be eaten by other predators downstream (Hongjamrassilp and Blumstein, under review). (Hongjamrassilp and Blumstein, under review) suggested a solution to mitigate this problem by using red or yellow cellophane as a filter to change the light color. However, technology could also benefit the shrimp if is used properly. Our results show that technology plays role in promoting the parading shrimp. Some 38% of participants heard about the parading shrimp through electronic devices (23% from social media and 15% from news from TV). Moreover, a search using Google Trends looking up the term “ (Parading shrimp in Thai)” in Thailand from January to December 2019, revealed that that people search “parading shrimp” the most during the first 2 weeks of the tourist season (i.e., in September) (Google Trends, 2020). Unfortunately, we found no websites that provide correct scientific information about the parading shrimp. Therefore, we suggest that the government should take this opportunity to create an online site that provides information about the shrimp, promotes shrimp ecotourism, and provides sustainable tourism guidelines.

(Parading shrimp in Thai)” in Thailand from January to December 2019, revealed that that people search “parading shrimp” the most during the first 2 weeks of the tourist season (i.e., in September) (Google Trends, 2020). Unfortunately, we found no websites that provide correct scientific information about the parading shrimp. Therefore, we suggest that the government should take this opportunity to create an online site that provides information about the shrimp, promotes shrimp ecotourism, and provides sustainable tourism guidelines.

Sustainable ecotourism requires collaboration between private stakeholders and government sectors (Bhuiyan et al., 2011). Moreover, locals' understandings and attitudes toward their resources are key factors to create sustainability (Vincent and Thompson, 2002). Our results indicated that all three main groups in this study (locals, stakeholders, and tourists) were concerned that the shrimp are vulnerable to declines, and that they would like to learn more about the shrimp. Even though they realized that the shrimp are part of the local culture, economy and ecosystem services, their knowledge regarding the roles of shrimp in the freshwater ecosystem was modest. Locals valued the shrimp in terms of culture, economy, and the environment less than tourists and stakeholders. Moreover, most of them did not realize that light from a flashlight is a threat to the shrimp, and they felt neutral toward the plan to reduce the use of personal flashlights to mitigate the effect of tourists on shrimp. We discuss the issues for Shrimp Watching tourism and make suggestions for further management below.

The survey results clearly show that tourists, stakeholders, and locals felt neutral about their knowledge regarding the shrimp. Moreover, they did not know that a key threat to the shrimp comes from the lights used by tourists. These results are not surprising because when the government promoted this Shrimp Watching in 1998–1999, little was known about the fundamental biology of the shrimp and nothing was known about anthropogenic threats to the shrimp. The first study studying parading shrimp biology and their responses to the anthropogenic threats came out in 2020, two decades after this ecotourism event was created (Hongjamrassilp et al., 2020). This Shrimp Watching tourism in Thailand is a case study showing the importance of developing a formal understanding of the effect of anthropogenic impacts on animals to properly manage them.

All three groups in this survey indicated that they were aware of decreasing shrimp populations, and they were willing to learn more about the shrimp. Based on this, we suggest that government managers could reduce anthropogenic disturbances on the parading shrimp by instating targeted educational programs aimed at each of the three participant groups. Tourists and stakeholders directly contact the shrimp and are unaware that light from their flashlights can harm the shrimp. This might be the reason why they felt neutral about the suggestion to do not use a personal flashlight and flash photography while watching the shrimp. However, they agreed to stay on the trail. Therefore, education must be targeted to inform these groups about the negative impacts of the personal flashlight use and flash photography. (Hongjamrassilp and Blumstein, under review) proposed creating three different zones for tourists. Tourists can use their flashlight and flash photography at one of the zones, but not the others. If successful, this plan could minimize the anthropogenic effects while maximizing tourist's desires to see the shrimp.

Sustainable ecotourism requires community members to obtain economic benefits from ecotourism (Vincent and Thompson, 2002; Li, 2006). This means they should first understand and value their natural resources. However, our results suggest that locals not otherwise involved in the ecotourism industry valued the shrimp less than the other two groups. This might be a function of differences in education or differences in economic status. Our results indicate that 80.3% of locals in this study completed their education at the high school level or below, but we do not have data regarding the participant's annual income. In other parts of the world, low education is associated with low socioeconomic status (e.g., American Psychological Association, 2017). Perhaps the neutrality of locals toward the tourism is because they do not obtain enough economic benefits from it. Other research has shown that if locals do not obtain sufficient benefits, it may lead to unsustainable ecotourism (Talsma and Molenbroek, 2012; Thanvisitthpon, 2016). We suggest that the government should support locals by educating them about the economic values of the shrimp and providing key information on how to conserve them. Importantly, however, the government has an important role in stimulating job creation around shrimp ecotourism so as to increase the number of individuals that benefit from it. Doing so may help increase the desire of locals to conserve this remarkable natural phenomenon.

While we have identified key roles for the government in helping to create more sustainable shrimp ecotourism, we recognize that this is a very top-down approach. Top-down management has been shown in other countries to be associated with unsustainable ecotourism (Garrod, 2003; Talsma and Molenbroek, 2012). In Thailand, research has shown top-down tourism development results in unsustainable outcomes and less effective (Ping, (n.d); Connell and Rugendyke, 2008; Muangasame and McKercher, 2015). One of the reasons is that locals do not get enough economic benefit from that tourism (Thanvisitthpon, 2016). On the other hand, creating a more bottom-up management, where locals and stakeholders participate in planning and development, provides an opportunity to improve the likelihood of a sustainable outcome (Middleton, 1997; Kopolratana, 2009; Talsma and Molenbroek, 2012; Theerapappisit, 2012). A case study in Jordan demonstrated that bottom-up approach can lead to sustainable cultural tourism (Jamhawi and Hajahjah, 2017). However, bottom-up approach alone could also lead to several problems. For example, locals sometimes lack of understanding regarding the concept of sustainability and knowledge about their own resources (Victurine, 2000). In our case study, we found that the locals do not really understand about the threats to the shrimp and the importance of the shrimp in environment, cultural, and economy aspects. This can result in ineffective plan development from locals who might want to only use the resource to get benefit for their own but do not aware about next generations. Another example is the issue regarding monopolization of resources. In Thailand, it has been known that the management power in community or ability to access resources is not equally distributed. Instead, it is centralized with local mafia (Shepherd, 2002; Kontogeorgopoulos, 2005) and Tambon Administrative Organization (TAO). People with good connections with the TAO can access more resources than others (Leksakundilok and Hirsch, 2008). Therefore, we suggest that the government should combine bottom-up and top-down approaches whereby the government, acting as the leader, actively involves the local community and stakeholders to plan and manage the tourist site for sustainable use (Wisansing, 2004; Kubickova and Campbell, 2020).

There are a number of issues that should be considered when applying a top-down and bottom-up approach, especially in developing countries. We will discuss two main examples. First, there is a real threat of what is referred to as “pseudo-participation” or “passive participation” (Tosun, 2000; Leksakundilok and Hirsch, 2008). Even though the top-down and bottom-up approach aims to equally involve stakeholders and locals during the process of management plan development, in many cases, stakeholders and locals actually act as consultants rather than participants and their input has not always been used during plan development. This pseudo-participation commonly occurs in many case studies from developing countries (Mowforth and Munt, 1998). Second, there is fear among locals and stakeholders of the authority power, and this impedes active collaboration. For instance, a case study from The Doi Tung Development Project in Thailand shows that when there is conflict of interest, it is difficult for locals to negotiate with authorities because they fear the authority's power (Theerapappisit, 2009). This cultural issue can be observed throughout Thailand and other developing countries such as Cambodia and Indonesia (Cole, 2006; Ellis and Sheridan, 2015; Palmer and Chuamuangphan, 2018). More discussions regarding implementation problems of top-down and bottom-up approach can be seen in Leksakundilok and Hirsch (2008) and Theerapappisit (2009). Governmental officials must be aware of these if they want to have a chance at creating truly sustainable management plans.

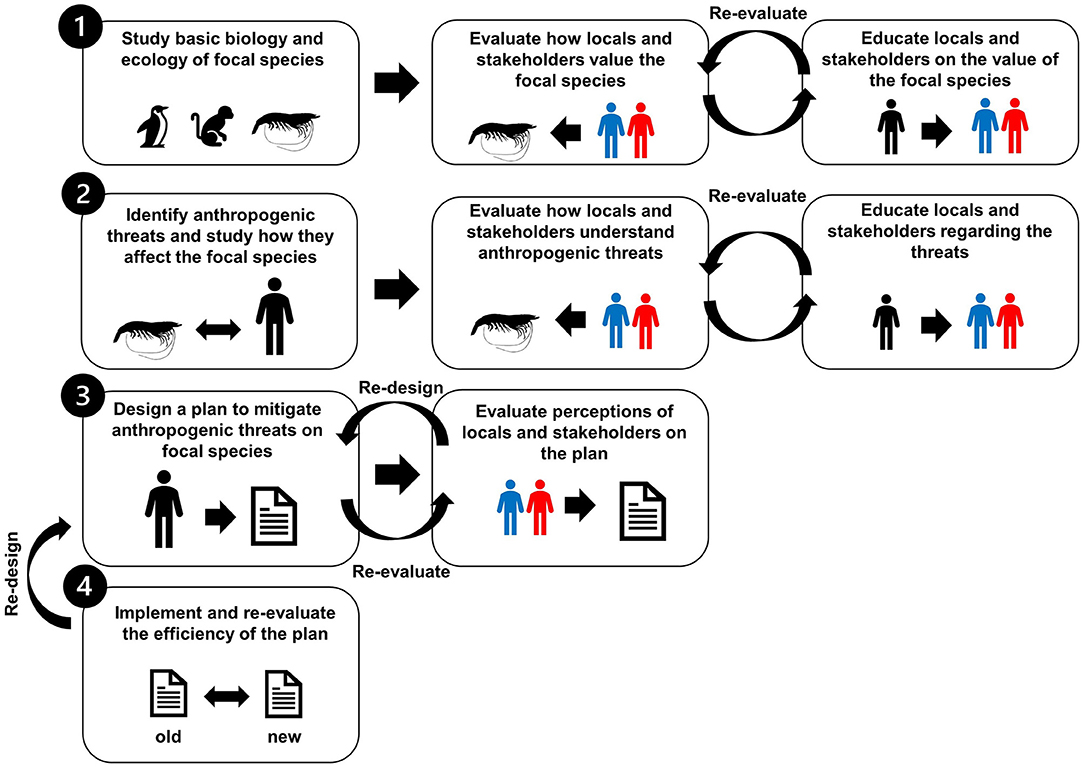

We have illustrated, with this case study, how an understanding of the biology of animals as well as an understanding of the people involved in ecotourism are essential for the scientific management of ecotourism and the creation of sustainable tourism. Here we propose a process to create sustainable wildlife ecotourism, which includes integrating top-down and bottom-up approaches (Figure 5). While we describe this process generally, it can be applied to manage parading shrimp, and it also could be applied to other targets of ecotourism (including plants and ecosystems). This process involves four steps.

Figure 5. Four-step framework to develop a sustainable wildlife ecotourism management plan. The colors of human symbols represent: (1) black = government staff, (2) red = stakeholders, and (3) blue = locals.

First, as a fundamental step of all conservation and management, it is essential to critically study biology and ecology (e.g., ecological roles) of each focal species (National Research Council, 1992). Often, this will be funded by the government or conducted by government researchers. Combined with this, surveys must be used to develop an understanding of how locals and stakeholders, who have an essential role in sustainable management, value the focal species along three major dimensions: culture, economy, and environment. Their understanding about their resources and their engagement are essential for successful conservation and management (Boiral and Heras-Saizarbitoria, 2017; Sterling et al., 2017). With these data in hand, the government can develop educational materials to ensure all locals and stakeholders have sufficient knowledge about the biology and ecology of the species/ecosystem. Built into this process is evaluation (Treephan et al., 2019), to ensure all locals and stakeholders understand the biological, ecological, and cultural values of the focal animals.

Second, it is essential to identify potential anthropogenic threats and study how these threats affect the focal animals (Tapper, 2006; Blumstein et al., 2017). Again, this will often be funded by the government or conducted by government researchers. With these data, surveys can be used to develop an understanding of the knowledge of locals and stakeholders about these threats. And again, educational materials and evaluation will ensure that locals and stakeholders understand the threats to the species. Depending upon existing knowledge of the system being studied, this process can be combined with the above process. A certificate program, educational program, or exam can be used to screen participants who wish to participate in step 3.

Third, the government, working together with certified locals and stakeholders, can develop a management plan to mitigate the anthropogenic threats on the focal species based on the knowledge of threats generated from targeted research (Wisansing, 2004; Kubickova and Campbell, 2020). This process will likely involve several iterations to ensure that locals and stakeholders support the proposed management actions, and, if required, the management action have remediations built in so as to not negatively affect the local economy.

Finally, the management plan should be implemented and re-evaluated over time (Salafsky et al., 2001; Higham et al., 2008). If the management plan is not effective in maintaining the biological or ecological resource (e.g., the population of a focal species declines), it should be re-designed with locals and stakeholder input. Throughout, the government is working closely with those who will be most affected by management to generate sustainable management solutions.

By working together, and committing to adaptive management (Holling, 1978; Dreiss et al., 2017), we hope that this spectacular natural phenomenon of shrimp leaving the water is able to entertain and educates future generations of tourists and provides needed resources to this rural Thai economy. Moreover, our suggested management framework could be used to develop a management strategy during developing of a new wildlife ecotourism, especially in developing countries.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by UCLA Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author Contributions

WH and DB designed the study and wrote and edited the manuscript. WH and PT collected survey and interview data. WH analyzed the data. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This research was supported by the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at UCLA, Sigma Xi Grants-in-Aid of Research (GIAR), and gift from Mr. Rerngchai Hongjamrassilp.

Conflict of Interest

DB is the field chief editor of Frontiers in Conservation Science.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the dedicated assistance of Mrs. Wassana Maiphrom, Mr. Narong Mangsachat, Ms. Waraphon Thipauthai, Ms. Kitiwara Paramat, Mrs. Pranom Thason, and other staff members from the Ubon Ratchathani Wildlife and Nature Education Center and the Yod Dom Wildlife Sanctuary for assisting in data collection. We thank the UCLA statistical consulting center for providing suggestions regarding statistical analysis. WH thanks Professors Greg Grether, Peter Narins, and Peter Nonacs for guidance and valuable discussions. We thank Dana Williams, Daniel S. Cooper, and two reviewers for comments on earlier versions of this manuscript.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcosc.2020.624239/full#supplementary-material

References

American Psychological Association (2017). Education and Socioeconomic Status. Available online at: https://www.apa.org/pi/ses/resources/publications/references (accessed September 22, 2020).

Back From The Brink (2019). Christmas Island Red Crab. Available online at: https://backfromthebrink.com/animals/christmas-island-red-crab/ (accessed December 25, 2020).

Barua, M., Gurdak, D. J., Ahmed, R. A., and Tamuly, J. (2012). Selecting flagships for invertebrate conservation. Biodivers. Conserv. 21, 1457–1476. doi: 10.1007/s10531-012-0257-7

Bhuiyan, M. A. H., Siwar, C., Ismail, S. M., and Islam, R. (2011). The role of government for ecotourism development: focusing on east coast economic region. J. Soc. Sci. 7, 557–564. doi: 10.3844/jssp.2011.557.564

Blumstein, D. T., Geffroy, B., Samia, D. S. M., and Bessa, E. (2017). “Creating a research-based agenda to reduce ecotourism impacts on wildlife,” in Ecotourism's Promise and Peril, eds D. T. Blumstein, B. Geffroy, D. Samin, and E. Bessa (Springer, Cham), 180–185. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-58331-0_11

Boiral, O., and Heras-Saizarbitoria, I. (2017). Managing biodiversity through stakeholder involvement: why, who, and for what initiatives? J. Bus. Ethics. 140, 403–421. doi: 10.1007/s10551-015-2668-3

Buehler, J. (2020). These Shrimp Parade on Land. Now We Know Why. Available online at: Available online at: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/2020/12/shrimp-parade-on-land-now-we-know-why/ (accessed December 10, 2020).

Clark, J. A., and May, R. M. (2002). Taxonomic bias in conservation research. Science 297, 191–193. doi: 10.1126/science.297.5579.191b

Cole, S. (2006). Information and empowerment: the keys to achieving sustainable tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 14, 629–644. doi: 10.2167/jost607.0

Connell, J., and Rugendyke, B. (2008). Tourism at the Grassroots: Villagers and Visitors in the Asia-Pacific. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203938027

Cranston, P. S. (2010). Insect biodiversity and conservation in Australasia. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 55, 55–75. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-112408-085348

Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 16, 297–334. doi: 10.1007/BF02310555

Dreiss, L. M., Hessenauer, J. M., Nathan, L. R., O'Connor, K. M., Liberati, M. R., Kloster, D. P., and Morzillo, A. T. (2017). Adaptive management as an effective strategy: interdisciplinary perceptions for natural resources management. Environ. Manage. 59, 218–229. doi: 10.1007/s00267-016-0785-0

Ellis, S., and Sheridan, L. (2015). The role of resident perceptions in achieving effective community-based tourism for least developed countries. Anatolia 26, 244–257. doi: 10.1080/13032917.2014.939202

Essen, E. V., Lindsjö, J., and Berg, C. (2020). Instagranimal: animal welfare and animal ethics challenges of animal-based tourism. Animals 10, 1–17. doi: 10.3390/ani10101830

Fallon, C., Hoyle, S., Lewis, S., Owens, A., Lee-Mäder, E., Hoffman Black, S., and Jepsen, A. (2019). Conserving the Jewels of the Night: Guidelines for Protecting Fireflies in the United States and Canada. Portland: OR: The Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation.

Fox, A. (2020). The Science Behind Thailand's Great Shrimp Parade. Available online at: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/thailands-great-shrimp-parade-180976452/ (accessed on December 10, 2020).

Garrod, B. (2003). Local participation in the planning and management of ecotourism: a revised model approach. J. Ecotourism. 2, 33–53. doi: 10.1080/14724040308668132

Google Trends (2020). Google Trends. Available online at: https://www.google.com/trends (accessed December 11, 2020).

Hall, C. M. (2012). “Glow-worm tourism in Australia and New Zealand: commodifying and conserving charismatic micro-fauna,” in The Management of Insects in Recreation and Tourism, ed H. Lemelin (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 217–232. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781139003339.017

Hawkins, D. E., and Lamoureux, K. (2001). “Global growth and magnitude of ecotourism,” in The Encyclopedia of Ecotourism, ed D. B. Weaver (New York: Cabi Publishing), 63–72. doi: 10.1079/9780851993683.0063

Higham, J. E., Bejder, L., and Lusseau, D. (2008). An integrated and adaptive management model to address the long-term sustainability of tourist interactions with cetaceans. Environ. Conserv. 34, 294–302. doi: 10.1017/S0376892908005249

Holling, C. S. (1978). Adaptive Environmental Assessment and Management. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

Holthuis, L. B., and Ng, P. K. L. (2010). “Nomenclature and taxonomy,” in Freshwater Prawns: Biology and Farming, 1st Edn. (Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell), 12–17. doi: 10.1002/9781444314649.ch2

Hongjamrassilp, W., Maiphrom, W., and Blumstein, D. T. (2020). Why do shrimp leave the water? Mechanisms and functions of parading behaviour in freshwater shrimp. J. Zool. 12. doi: 10.1111/jzo.12841

Huntly, P. M., Van Noort, S., and Hamer, M. (2005). Giving increased value to invertebrates through ecotourism. Afr. J. Wildl. Res. 35, 53–62. doi: 10.7287/peerj.preprints.1178v1

Jamhawi, M. M., and Hajahjah, Z. A. (2017). A bottom-up approach for cultural tourism management in the old city of As-Salt, Jordan. JCHMSD 7, 91–106. doi: 10.1108/JCHMSD-07-2015-0027

Jaun-Holderegger, B. (2012). Biodiversität an primarschulen. Früh übt sich! [Biodiversity at primary schools. Start early!]. Hotspot Biodivers. Bildung. 26, 8–9.

Kontogeorgopoulos, N. (2005). Community-based ecotourism in phuket and ao phangnga, Thailand: partial victories and bittersweet remedies. J. Sustain. Tour. 13, 4–23. doi: 10.1080/17501220508668470

Kopolratana, P. (2009). Wetland tourism management at don hoi lot (ramsar site), samut songkhram province (Doctoral dissertation). Bangkok, Thailand: Mahidol University.

Krüger, O. (2005). The role of ecotourism in conservation: panacea or pandora's box? Biodivers. Conserv. 14, 579–600. doi: 10.1007/s10531-004-3917-4

Kubickova, M., and Campbell, J. M. (2020). The role of government in agro-tourism development: a top-down bottom-up approach. Curr. Issues Tour. 23, 587–604. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2018.1551338

Leksakundilok, A., and Hirsch, P. (2008). “Community-based ecotourism in Thailand,” in Tourism at the Grassroots: Villagers and Visitors in the Asia-Pacific, eds J. Connell and B. Rugendyke (New York, NY: Routledge), 214–235.

Lemelin, R. H. (2013). The Management of Insects in Recreation and Tourism. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781139003339

Lewis, S. M., Wong, C. H., Owens, A., Fallon, C., Jepsen, S., Thancharoen, A., et al. (2020). A global perspective on firefly extinction threats. BioScience 70, 157–167. doi: 10.1093/biosci/biz157

Li, W. (2006). Community decision making participation in development. Ann. Tour. Res. 33, 132–143. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2005.07.003

Lindemann-Matthies, P. (2006). Investigating nature on the way to school: responses to an educational programme by teachers and their pupils. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 28, 895–918. doi: 10.1080/10670560500438396

Mavhunga, C. (2011). Mobility and the Making of Animal Meaning: the Kinetics of 'Vermin' and 'Wildlife' in Southern Africa. Making Animal Meaning. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press. 17–44.

Middleton, V. T. C. (1997). “Sustainable tourism: a marketing perspective,” in Tourism and Sustainability: Principles to Practice, ed M. J. Stabler (Oxford, England: CAB International), 129–142.

Mowforth, M., and Munt, I. (1998). Tourism and Sustainability: New Tourism in the Third World. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203437292

Muangasame, K., and McKercher, B. (2015). The challenge of implementing sustainable tourism policy: a 360-degree assessment of Thailand's “7 greens sustainable tourism policy”. J. Sustain. Tour. 23, 497–516. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2014.978789

Murphy, P. E., and Murphy, A. E. (2004). Strategic Management for Tourism Communities: Bridging the Gaps. Bristol: Channel View Publications. doi: 10.21832/9781873150856

National Research Council (1992). Conserving Biodiversity: a Research Agenda for Development Agencies. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Nurancha, P., Inkapatanakul, W., and Chunkao, K. (2013). Guidelines to the management of firefly watching tour in Thailand. Mod. Appl. Sci. 7, 8–14. doi: 10.5539/mas.v7n3p8

Pacheco, X. P. (2018). How Technology Can Transform Wildlife Conservation. Available online at: https://www.intechopen.com/books/green-technologies-to-improve-the-environment-on-earth/how-technology-can-transform-wildlife-conservation (accessed on December 10, 2020).

Palmer, N. J., and Chuamuangphan, N. (2018). Governance and local participation in ecotourism: community-level ecotourism stakeholders in Chiang Rai province, Thailand. J. Ecotourism. 17, 320–337. doi: 10.1080/14724049.2018.1502248

Ping, W. J. (n.d). Community-Based Ecotourism and Development in Northern Thailand. Available online at: http://www.asianscholarship.org/asf/ejourn/articles/jianping_w.pdf (accessed September 25, 2020).

Preston, E. (2020). These Shrimp Leave the Safety of Water and Walk on Land. But Why? Available online at: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/11/18/science/shrimp-parade-thailand.html (accessed December 10, 2020).

R Core Team (2020). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria. Available online at: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed September 25, 2020).

Salafsky, N., Margoluis, R., and Redford, K. H. (2001). Adaptive Management: a Tool for Conservation Practitioners. Washington, DC: Biodiversity Support Program.

Sánchez Cañizares, S. M., Castillo Canalejo, A. M., and Núñez Tabales, J. M. (2016). Stakeholders' perceptions of tourism development in Cape Verde, Africa. Curr. Issues Tour. 19, 966–980. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2015.1008428

Schlegel, J., Breuer, G., and Rupf, R. (2015). Local insects as flagship species to promote nature conservation? A survey among primary school children on their attitudes toward invertebrates. Anthrozoös 28, 229–245. doi: 10.1080/08927936.2015.11435399

Shepherd, N. (2002). How ecotourism can go wrong: the cases of seacanoe and Siam Safari, Thailand. Curr. Iss. Tour. 5, 309–318.

Sterling, E. J., Betley, E., Sigouin, A., Gomez, A., Toomey, A., Cullman, G., and Filardi, C. (2017). Assessing the evidence for stakeholder engagement in biodiversity conservation. Biol. Conserv. 209, 59–171. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2017.02.008

Stronza, A., and Pegas, F. (2008). Ecotourism and conservation: two cases from Brazil and Peru. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 13, 263–279. doi: 10.1080/10871200802187097

Talsma, L., and Molenbroek, J. F. M. (2012). User-centered ecotourism development. Work 41, 2147–2154. doi: 10.3233/WOR-2012-1019-2147

Tapper, R. (2006). Wildlife Watching and Tourism: A Study on the Benefits and Risks of a Fast Growing Tourism Activity and its Impacts on Species. Bonn: UNEP/Earthprint.

Thanvisitthpon, N. (2016). Urban environmental assessment and social impact assessment of tourism development policy: Thailand's Ayutthaya historical park. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 18, 1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.tmp.2016.01.006

The International Ecotourism Society (2015). What Is Ecotourism. Available online at: https://ecotourism.org/what-is-ecotourism/ (accessed September 22, 2020).

The World Travel Tourism Council (2019). Economic Impact Reports. Available online at: https://wttc.org/Research/Economic-Impact (accessed September 22, 2020).

Theerapappisit, P. (2009). Pro-poor ethnic tourism in the Mekong: a study of three approaches in Northern Thailand. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 14, 201–221. doi: 10.1080/10941660902847245

Theerapappisit, P. (2012). “The bottom-up approach of community-based ethnic tourism: a case study in Chiang Rai,” in Strategies for Tourism Industry: Micro and Macro Perspectives, ed M. Kasimoglu (Croatia: InTech), 267–294.

Tosun, C. (2000). Limits to community participation in the tourism development process in developing countries. Tour. Manag. 21, 613–633. doi: 10.1016/S0261-5177(00)00009-1

Treephan, P., Visuthismajarn, P., and Isaramalai, S. A. (2019). A model of participatory community-based ecotourism and mangrove forest conservation in Ban Hua Thang, Thailand. Afr. J. Hosp. 8, 1–8.

Veríssimo, D., Barua, M., Jepson, P. D., MacMillan, D. C., and Smith, R. J. (2012). Selecting marine invertebrate flagship species: widening the net. Biol. Conserv. 145:4. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2011.11.007

Victurine, R. (2000). Building tourism excellence at the community level: capacity building for community-based entrepreneurs in Uganda. J. Travel Res. 38, 221–229. doi: 10.1177/004728750003800303

Vincent, V. C., and Thompson, W. (2002). Assessing community support and sustainability for ecotourism development. J. Travel Res. 41, 153–160. doi: 10.1177/004728702237415

Whelan, J. C. (2012). Experiments with entomological ecotourism models and the effects of ecotourism on the overwintering monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus) (Doctoral dissertation). Florida (FL): University of Florida.

Wisansing, J. (2004). Tourism planning and destination marketing: toward a community-driven approach: a case of Thailand (Doctoral dissertation). Oakland: California: Lincoln University.

Keywords: animal-based tourism, flagship species, invertebrate tourism, invertebrate conservation, sustainable ecotourism, Southeast Asia, Thailand, wildlife watching

Citation: Hongjamrassilp W, Traiyasut P and Blumstein DT (2021) “Shrimp Watching” Ecotourism in Thailand: Toward Sustainable Management Policy. Front. Conserv. Sci. 1:624239. doi: 10.3389/fcosc.2020.624239

Received: 30 October 2020; Accepted: 18 December 2020;

Published: 26 January 2021.

Edited by:

Silvio Marchini, University of São Paulo, BrazilReviewed by:

Pierre Walter, University of British Columbia, CanadaErica von Essen, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Sweden

Copyright © 2021 Hongjamrassilp, Traiyasut and Blumstein. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Watcharapong Hongjamrassilp, d2luYmlvbG9naXN0QHVjbGEuZWR1; d2F0Y2hhcmFwb25nLmhnQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Watcharapong Hongjamrassilp

Watcharapong Hongjamrassilp Prapun Traiyasut2

Prapun Traiyasut2 Daniel T. Blumstein

Daniel T. Blumstein