- 1BioARTech Laboratory, Faculty of Art and Design, University of Lapland, Rovaniemi, Finland

- 2DESIS-Q Laboratory, Department of Strategic Design, Kyushu University, Faculty of Design, Fukuoka, Japan

At the intersection of artistic performance, bioart, technology, and visual communication, this article explores how more-than-humans (MTHs) can be visualised, given a voice, and recognised as active collaborators in societal systems. The BioART Laboratory at the University of Lapland conducted a series of textile and digital art studies focussed on fostering shared growth and collaboration between humans and MTHs. This research aimed to investigate how active cooperation between humans and MTHs can be stimulated through visual communication and what roles improvisation, materiality, and digital technologies play in conveying such processes in a post-humanist context. To address these questions, two studies employing arts-based research were drawn from a series of studies conducted in the laboratory between 2021 and 2022. These studies examined the materiality, performative practices, and digital documentation of MTHs, employing photographic layering techniques and biotextiles. The affordances created through collaboration with MTHs for diverse improvisational and performance practices and the use of digital tools and multidimensional approaches were analysed. This analysis established a critical framework grounded in applied learning and self-reflection to better understand the contributions of MTHs to visual communication.

1 Introduction

This article discusses visual communicative practices and their relationships with more-than-humans (MTHs). Set in the framework of post-humanism, perspectives derived from non-Eurocentric origins remain largely marginalised. Barad’s (2003) study provides critical context for the post-humanist turn and the development of new materialist thinking. Barad begins by critiquing the power of language to confer meaning and the various twists it has introduced, including semiotic, interpretive, and cultural shifts. They argue that even materiality has been reduced to a form of language or cultural representation. Our article focuses on the post-humanist and material turn in relation to MTHs. Barad (2003) emphasises that understanding performative discursive practices challenges the representationalist belief that words merely describe predetermined things. By ‘performativity’, Barad refers to the productive nature of actions, suggesting that performativity challenges the supremacy of language in defining reality. In our study, performances are based on improvisatory practices and placemaking.

Barad (2003) explores performativity through practice and creation, arguing that the shift from representationalism to performative alternatives redirects attention from questions of reciprocity and the correspondence between descriptions and reality to an emphasis on practices, actions, and agency. These perspectives raise essential questions about ontology, materiality, and agency, exposing the limitations of social constructivism, which operates as an endless feedback loop with no new insights. Furthermore, Barad clarifies the theory of performativity in the contexts of scientific research, feminist theory, and queer theory. They examine performativity from materialist, naturalist, and post-humanist perspectives, highlighting the active participation of matter through the concept of ‘intra-action’. This performative understanding shifts the focus from linguistic representations to discursive practices. In this article, discursive practices, such as placemaking, design, and artistic co-authorship, are shown to construct social realities that incorporate MTHs as active participants.

With such perspectives, post-humanism can evolve by encouraging the emergence of marginalised knowledge (Ylirisku et al., 2024). Our studies investigate one example of such marginalised knowledge: visual communication with MTHs. Ylirisku et al. (2024) describe post-humanism as an intersection of ‘other critiques of humanism, including decolonial thought, feminism, and critical race theory, and thus attend to questions of ethics, power relations, and politics’. They emphasise that ‘many Indigenous epistemologies and cosmologies never parted from the entangled view of the world, and if these views are not accounted for, posthumanisms risk becoming yet another form of colonialism’ (Ylirisku et al., 2024, p. 2). A key post-humanist question is how to de-centre or deterritorialise humans, which has been critical, and consequently, how to foster alternative ways of knowing (Young and Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles, 2020). Furthermore, post-humanism seeks to dismantle the juxtaposition between humans and nature, recognising humans as integral to nature (Sundberg, 2014). Deleuze and Guattari (1987) provide another essential perspective by introducing rhizomatic thinking, which they describe as a non-hierarchical model of knowledge creation and social organisation. Rhizomatic thinking fosters interconnectedness between ideas, identities, and social practices (Deleuze and Guattari, 1987).

Our article aimed to explore how humans and MTHs can use improvisatory processes to review and re-enact knowledge co-creation. This process involves active and enacted practices of looking, seeing, and understanding (Seymour, 2023), creating new understanding through visuality and expression in collaboration with MTHs. In post-humanist theory, creativity is grounded in Indigenous epistemologies and critiques, and it can be contextualised as universal and extending beyond human activity (Henriksen et al., 2022). Barad’s (2007, pp. 128, 170, 178) concept of intra-action suggests that entities do not pre-exist in their interactions; rather, they emerge and take form through these interactions. Intra-action implies that meaning and agency emerge from the entangled relationships between subjects and objects. This contrasts with the traditional notion of ‘inter-action’, which assumes that subjects and objects are pre-existing entities that interact. Intra-action emphasises how entities come into being or continuously evolve, carrying profound implications for the agency. Our article also aims to expand the understanding of agency by recognising and respecting nature as a co-author in artistic practices. Intra-action suggests that in the entangled relationship between humans and MTHs, new forms of agency and authorship can emerge (Barad, 2007, p. 218). This evolving view of nature’s authorship is evident in legal and societal changes, as some jurisdictions currently recognise nature as a legal subject (Pelizzon et al., 2021). We remain attentive to the inherent differences among humans, particularly in post-humanist contexts.

This article poses the following questions: How can the post-humanist turn inform design practice, thinking, and performative ontologies? How can interactions between humans and MTHs, as well as cross-species translations, impact relationships such as co-authorship? How can these relationships be visually conveyed to raise awareness of human boundaries? Our article addresses these questions through two artistic studies, focussing on experiencing the natural environment and recognising diverse species as authors (Sheber, 2020). These studies emphasise visually representing place, respecting placemaking, and recognising nature as an artistic author. Arts-based research (ABR) was used to study the role and agency of MTHs (Miettinen et al., 2022). For example, Deleuze and Guattari (1987, p. 80) propose the concept of assemblages as complex networks of heterogeneous elements in which both humans and MTHs can exert agency, create new formations, and shape social realities. Assemblages underscore the interconnectedness of cultural, political, and social factors, providing insights into complex systems (Deleuze and Guattari, 1987).

The two artistic studies conducted at the Bioartex Laboratory at the University of Lapland employed an ABR strategy to explore MTH and human performances (Leavy, 2017). Study 1, ‘Filming Placemaking Through Performance’, explores the relationship between improvised performance and the affordances offered by natural environments. This study investigated the human–environment relationship in an art- and design-based context. Study 2, ‘Roots Stitching’, explored bioart tapestry-making and how its performative aspects can enable co-authorship between MTHs and artists. Härkönen et al. (2023) analysed ‘Roots Stitching’ from a legal and copyright law perspective, focussing on the temporary nature of the growth of the seedlings. The process involves transforming fleece into a tapestry by stitching fibres into a mat. From an artistic performance perspective, the growth of seedlings can be viewed as a form of artistic activity, which is comparable to traditional artistic performances (Härkönen et al., 2023). Usually, an artistic performance ends when it wraps up with the last tone or movement. Similarly, in tapestry-making, the growth of the seedlings halts and dries out during the final stages of the process. Both activities are, however, driven by human action and interpretation, but in the case of tapestry, MTHs act in collaboration with humans.

Both studies generated new meanings and knowledge through co-authorship and visual communication with MTHs. Liebenberg (2024, p. 115) emphasises the urgency of finding ‘new ways to talk—through image, text, and objects—about human–plant relationships’ and broader MTH–human interactions. To address this, this article employs photography and video for documentation and visual communication. A critical view on the use of various forms of visual documentation is presented by Sontag (2018), who cautions that ‘pictures do not speak for themselves; they need a historical and geographical context’. Such critical views are considered in both studies.

Kelly et al. (2020) argue that visual elements have become the primary means of conveying information in contexts such as media, social media, and education. The complexity of these multi-contextual applications underscores the need for visual literacy to critically interpret images. Visual communication facilitates understanding with the help of visual images in an increasingly digital world (Josephson et al., 2020). Sontag (1977) explored how photography shapes our sense of reality, engagement with the world, and perception of events. She posits that while photography can reveal truths, it can also alienate us from reality, urging artists to be cautious in interpreting and communicating reality through visual means. Sontag (1977, pp. 174–178) calls for a critical approach to consuming images.

Creating photographic and visual images with MTHs contributes to understanding social reality. Moriarty and Barbatsis (2005, p. xiii) assert that visual communication cannot and should not be confined to a ‘unifying theory’ ‘because it represents the intersection of thoughts from many diverse traditions’. As a starting principle, visual communication entails conveying, representing, and interpreting visual elements to communicate concepts and information. At the same time, it unites individuals without requiring a shared spoken language, enabling them to create common experiences and emotions (Günay, 2021). Design, as a visual language, uses visual cues and components to convey messages or address problems (Günay, 2021). Through visual communication, we can contribute to inclusion, exclusion, and agency; therefore, this article uses visual communication to challenge and reconsider human agency in interactions with MTHs.

2 Theoretical framework

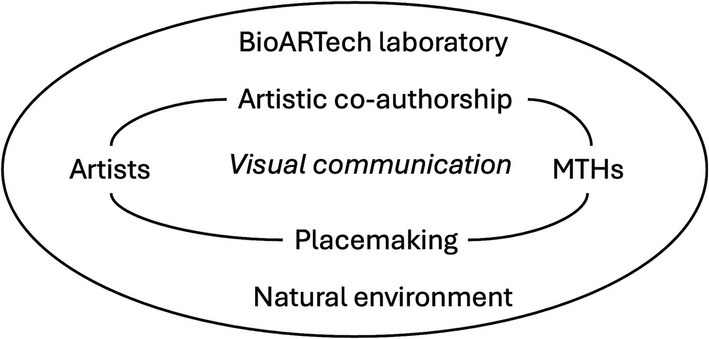

The theoretical framework is constructed through artistic co-authorship and placemaking with MTHs in the natural environment and at the Bioartex Laboratory. Both artistic co-authorship and placemaking are visually communicated. This laboratory focuses on developing new knowledge about bioart by creating activities that combine bioart, fashion and textile art, creative research (using arts-based methods and ABR), biotechnology, and science. The physical laboratory is in the Faculty of Art and Design at the University of Lapland, but its research connects diverse natural environments in Finland and globally.

McEwan (2023) raises the question of how to ethically engage with proteas, endangered wildflowers in South Africa, where human livelihoods are prioritised in policymaking. She aims to investigate the possibility of dialogue between humans and MTHs and to enable the agency of proteas in multispecies storytelling. McEwan examines phytography, which enables visual communication by studying plants by means of writing or photography. This article investigates similar relationships, especially how co-authorship and placemaking allow artists to visually communicate with and about MTHs in the natural environment or the Bioartex Laboratory. Haraway (2007) investigated how narratives and storytelling are the focal points in understanding and communicating complex species interactions. Additionally, Haraway (2007) suggests that diverse narratives are needed to recognise many voices in ecological dialogue. Furthermore, she reminds us of ethical considerations and our responsibility towards non-human life. Connecting to these different views, this article draws from artistic co-authorship and placemaking to explore visual communication through performance collaborations.

2.1 Design and artistic co-authorship with MTHs

‘Design for more-than-human futures is an invitation to travel new paths for design framed by an ethics of more-than-human coexistence that breaks with the unsustainability installed in the designs that outfit our lives’ (Tironi et al., 2024, p. 2). The transformative times we live in require more radical approaches to design that can enable the exploration of alternative ways of life. As Tironi et al., (2024, p. 2) posits, ‘design cannot be a mere spectator, nor can it continue to replicate clientelist and instrumentalist strategies for relating to the world’ by ‘rethinking our anthropocentric inheritance’. Humans should reflect on their transformative capacities, turning their detrimental impact into working with nature and enabling the agency for MTHs.

Artistic co-authorship with communities, past and present artists, or MTHs contributes to plural design by providing new views and ways to create authorship in a post-humanist society (Bacharach and Tollefsen, 2015). Natural resources can contribute to designing a more inclusive society that strives for activism and more political agendas. Nature is increasingly recognised as an author in scientific publications, such as Martuwarra RiverOfLife (Pelizzon et al., 2021) and Wann Country (Foster et al., 2020). Similarly, co-authorship with nature through the arts can create radically new ways of investigating ethical and copyright questions by offering alternate views, but more research is needed. Hick (2014) studied co-authorship and multiple authorship in artistic practice, but the role of plants, animals, and other non-human entities remains underexplored and warrants further investigation.

Mitchell (2010, p. 11) defines bioart as a ‘medium’ offering conditions for emergence through processes of biological mutation. Biotextile is defined by Plank (2020, para. 5) as ‘biofabricated textiles [that] are materials grown from live microorganisms’. The performative aspects of this biotextile were explored by Härkönen et al. (2023) from a legal and copyright perspective. The analysis described bioart as a performance, as the author was not wholly in control throughout the creative roots stitching processes. In its living form, the authorship of the biotextile belongs to the seedlings who stitched the tapestry. In a later stage, after the seedlings have died and the biotextile emerges in its dried state, the authorship of bioart may transfer at a later stage to the bioartist.

2.2 Placemaking with more-than-humans

Placemaking relates to urban design and the inclusion of communities when co-designing or performing. In recent years, placemaking in natural environments and rural communities utilising performance and other arts-based methods has been studied (Björn and Miettinen, 2024; Björn et al., 2023). Humanistic geographer Relph (1976) provided an analytical account of place identity, drawing on personal experience. Place-based identity unites a place’s affective and cognitive aspects (Paasi, 2003) and is, like gender or social class, a substructure of self-identity. Creative placemaking and place-based art have evolved to become social, economic, and culturally empowering art forms that place artists and arts workers at the centre of their communities. As a result, artists have become proactive protagonists as to what communities, not governments, can accomplish through the arts (Grodach, 2011). Documentary films can be used as tools for creative placemaking (Plow, 2015).

The goal of placemaking practice is to go beyond the ‘tourist gaze’ (Urry, 1992). Place-based arts adopted a deep consideration for ‘place ethic’, which demands respect for any place that reaches further than merely drawing aesthetic inspiration derived from what is known as the ‘tourist gaze’, which often results from a superficial and short-term interaction with a place (Lippard, 1997). Thus, place ethics considers the cultural value of a place, acknowledging that it is deeply rooted in cultural meanings and traditions that are often rendered invisible or silent due to the hegemonic forces at play. Björn and Miettinen (2024) discuss place-based arts and service design that engage with place ethics in the context of artistic cartographies. Through these approaches, the authors explore new materialities, methods of self-presentation, and ways to consider the cultural significance of a place. They propose that artistic cartographies and placemaking offer valuable means to acknowledge and preserve the deeply rooted cultural and natural meanings and traditions of a place (Björn and Miettinen, 2024).

A critical view of traditional placemaking highlights its reliance on community consultation and local stories while still operating within colonial conceptualisations of the ‘site’ (Foster et al., 2020). These authors explain that the concept of a country includes the ecologies of plants, animals, water, sky, air, and all aspects of the natural environment. Björn et al. (2023) have explored placemaking as a place-specific approach to service design that engages reflexivity, knowledge-sharing, and epistemology towards non-humans, for example, plants and the surrounding environment. Placemaking can help identify place-related values, such as appreciation of nature and culture, through service design.

3 Methodology

Hultin (2019) reflects on the researcher’s role in a world constantly shaped by socio-material practices. He aims to understand how the ontological position underlying the socio-material approach relates to epistemology and how we can act more creatively and responsibly as socio-material researchers. This research design utilises the premises of creativity and responsibility.

According to performative ontology, knowledge and meanings arise from actions and relationships. Material elements play a role in the production of knowledge. Therefore, it is essential in research to consider social and material relationships and to understand that the research process should be viewed as an active process and a network of relationships. Phenomena should be examined as dynamic and relational, using research methods that consider context, relationships, and materiality. Such methods include ethnography and participatory observation. The active role of the researcher influences research, knowledge creation, and sharing (Hultin, 2019).

Our research emphasises epistemological practices rooted in relational and performative ontology, highlighting the dynamism and diversity of knowledge. According to relational ontology, knowledge is context-dependent and shaped by social relationships and interactions (Hultin, 2019). Our interactions are with MTHs in our artistic practice. However, according to performative ontology, knowledge does not passively reflect reality but is generated through agency and relationships. Some epistemological practices include participatory research, ethnography, interaction, and a research process allowing reflection and adaptation (Hultin, 2019).

We employed ABR to generate new knowledge through the lens of the post-humanist material turn and performativity (Barad, 2003). Methodologically, our article reflects on two artistic studies: (1) Filming “Placemaking Through Performance” and (2) Roots Stitching. The research strategy employed is ABR, an overarching research approach that includes various art forms, genres, and practices (Leavy, 2015). However, it is important to acknowledge that ABR takes place in the post-human context. ABR is also a hybrid and practice-based methodology (Sinner et al., 2006) that often leaves practitioners in the ‘in-betweenness’ of ‘knowing, doing and making’ (Pinar et al., 2004), contributing to performative aspects. Art-making processes have a strong potential to generate knowledge that may be used and applied by the makers and researchers of artistic practice, thus transitioning from tacit and implicit to explicit. This premise is the basis of practice-based (or practice-led) and artistic research (e.g., Koskinen et al., 2011).

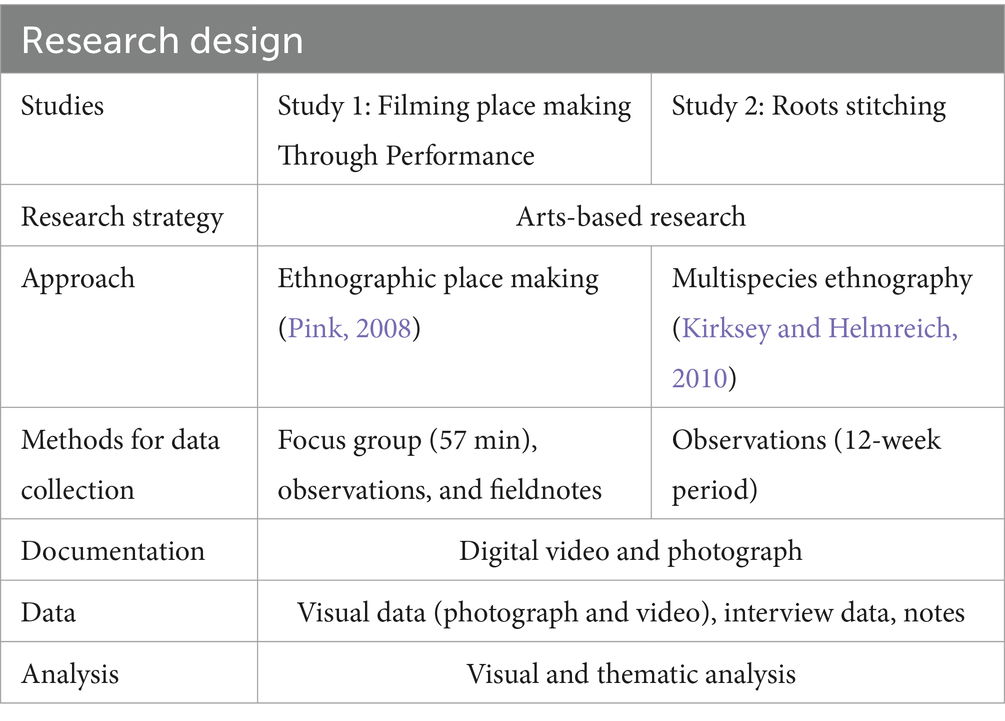

We relied on the art-making process with MTHs and independent artistic works. The artistic processes incorporated arts-based methods, such as improvisation, intuition, performance, and photography. ABR can cultivate empathy and self-reflection by disrupting dominant narratives through performance and storytelling (Leavy, 2017). The research design employed an iterative strategy based on learning from one’s research process and findings (Thomas and Rothman, 2013). New theories, artefacts, and practices were produced as an outcome of the research design process (Barab and Squire, 2004). The two artistic studies demonstrate how MTH and human interaction can be visually communicated to contribute to inclusive, reflective practices. The analysis aimed to provide a structured critical framework for active collaboration between humans and MTHs and how humans can deterritorialise representations through visual communication. Observations, digital film, and photo documentation served as essential data analysis methods. Additionally, interviews with performers, conducted as part of a focus group discussion, were incorporated into the placemaking through Performance study, specifically a focus group discussion. A detailed discussion of Studies 1 and 2 will further elucidate these findings (Table 1).

3.1 Study 1: filming “placemaking through performance”

Study 1 draws on the study by Pink (2008), who explores sensory sociality and its role in placemaking. Pink (2008) argues that focussing on place invites ethnographers to conceptualise how embodied beings are differentiated by gender, generation, class, race, ethnicity, and more. The researcher and the researched are jointly present in a simultaneously experienced and constructed place. Walks and routes connect us to the processes of placemaking. Pink uses both the walks and the routes to question whether the ethnographer and the researcher are also participants in placemaking and whether ethnographic research can be examined from the perspective of placemaking. Study 1 connects ethnography and placemaking through observations, notes, and interviews. Pink (2008) describes ethnographic placemaking as a crossroads of direct experience and its reorganisation. In this context, memories are emphasised alongside systematic material analysis. Pink suggests that theorising common ethnographic methods through placemaking generates an understanding of how people construct urban environments through embodied and imaginative practices and how researchers create ethnographic places (see Table 2).

Study 1 is based on the video ‘placemaking through performance’, which includes several artistic video processes. The placemaking performances were conducted with groups of women. The author (she/her) had a long-term relationship with the women in different roles, such as colleague, thesis supervisor, and friend. There was familiarity and care when documenting the performances (Sarantou et al., 2021, 87–89).

Filmmaking is used as a means of visual communication. Carbonell (2022) studied a new mode of filmmaking called multispecies cinema, which is an attempt to experience MTHs through the use of different senses, such as seeing, hearing, and feeling, providing a means for understanding the ecosystem in flux. Barad (2017) discusses spacetimemattering, marking the inseparability of space, time, and matter. This verb stands for the relationalities of moments, places, things, and the intra-actions that configure and iterate them. The video format can enable spacetimemattering to represent the role of material in constructing reality. Time and temporality can be manipulated in the video. It enabled the artists to visualise and communicate several positions and even render the past and present into the same frame (Sinquefield-Kangas et al., 2022).

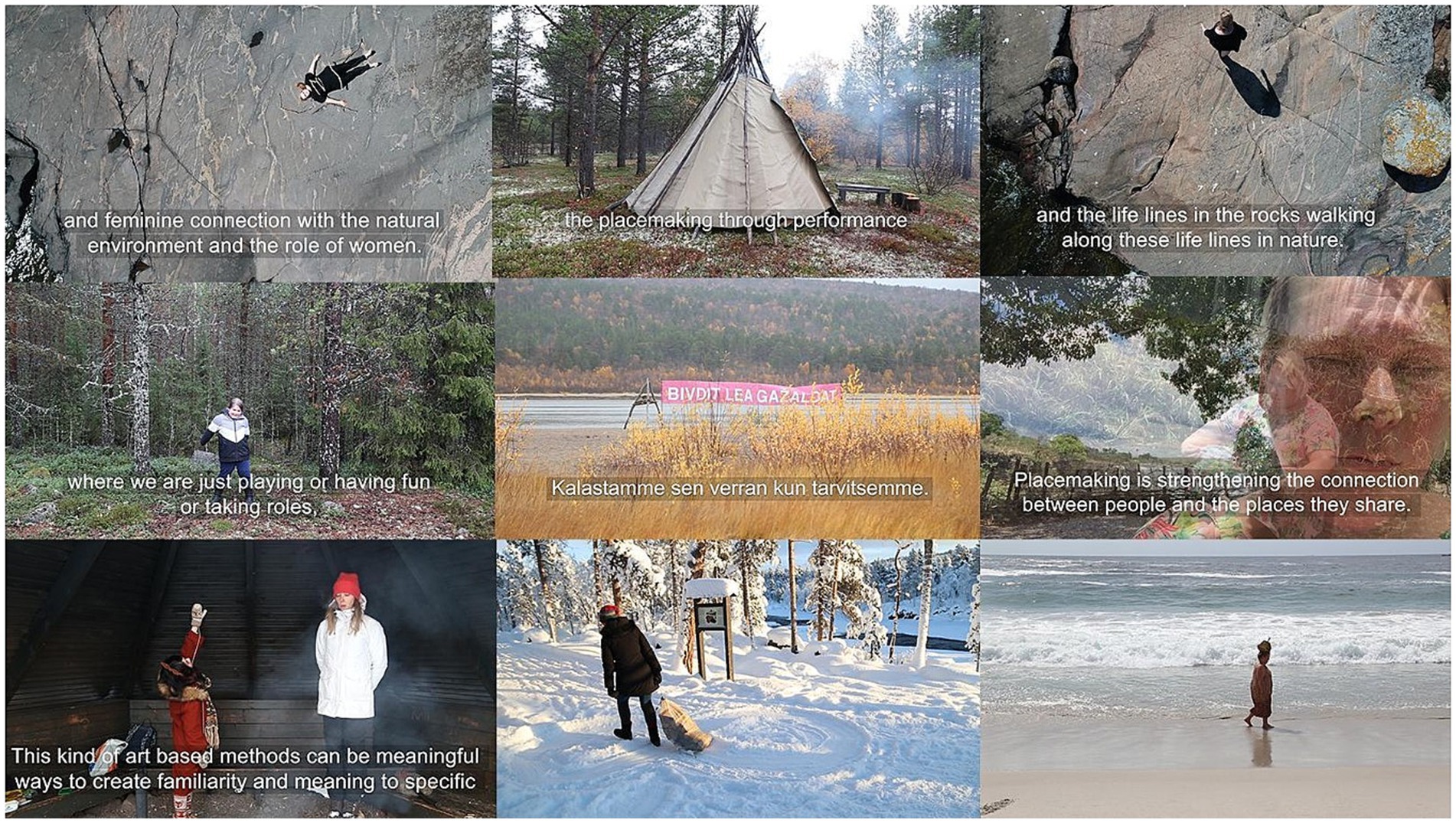

We examined the idea of placemaking and performing in a natural environment and through embodied experience. Filming ‘placemaking through performance’ involved artistic processes using photography, video, and performance to design, test, and iterate new artistic ways and meanings for placemaking and create artistic performances in the natural environment. The idea of performing and performance developed through several embodied studies through working intuitively in a natural environment during the shooting sessions. In our artistic processes, placemaking provides storytelling and performance channels to create the personal understandings and meanings of a place. The artistic research process included critical thinking and evaluation of the meaning and contents (Henke et al., 2020) of the artistic process (see Figure 1).

In the top right image of Figure 2, the performer traces the lifelines of the granite engraved in the rock bed with her feet. The performer honours the temporal dimensions of the stone and its enduring interconnectedness with the culture and stories of the local community that lived on Vänö Island in Finland. The bottom centre image (Figure 2) illustrates that the performance is about the physical burden placed on the performer by dragging a bundle of chopped wood in the perpetual shape of an enigma. Performance signifies providing resources often exploited by human-centred and consumer existence. In addition, the performances interacted with nature, as the affordances of the natural environment—such as the hard rock surface and soft snow—both enabled and, in the case of the snow, restricted the performance due to the heavy wood bundle.

Figure 2. Images from the placemaking through performance video. Videoart by Satu Miettinen Miettinen et al. (2022).

3.1.1 The scenes of “video placemaking through performance”

The scenes in this video address several topics, including the role of women and the feminine connection with the natural environment. For example, the starting scene is improvised around a warrior Viking woman’s burial. The next scene is about the female connection with the rocks, with a woman walking along the lines on rock surfaces, following the lifelines in nature. The viewer may feel grounded by the rocks and connected to them.

One of the topics explores a performance within the space of a sauna in northern Finland, specifically a wooden, heated sauna. The project explored how diverse feminist perspectives can be adopted in photo documentation, including in fashion photography (Sarantou et al., 2021). Many performers participated in producing these scenes, adding layers of meaning. For example, some performers used intuition and improvisation while wearing Sarantou’s Water Waisted fashion collection. The artist herself wore the collection for sauna performances in the subzero temperatures of Pyhätunturi. Artistic processes overlap and develop in self-expression and meaning throughout the video project. Sarantou’s comment in this video, ‘I’m running out of water’, creates several meanings. Having no water to pour on the hot sauna stone or the global drought and lack of water in the desert regions, the author is familiar with experiences in Namibia and South Australia, which inspired the fashion collection.

One of the scenes in the video shows how children and adults can engage in both realistic and imaginative play in forests (Miettinen and Sarantou, 2021a). Washinawatok et al. (2017) explored children’s sensitivity to ecological relations when engaging with forests. This exploratory play can also be performed in or with the natural environment. Some of the locations in the video are very familiar, for example, the forest close to Miettinen’s house in Korkalovaara, where she played, trying out different things, having fun, and assuming roles.

Scenes four and five are called ‘Jäniskoski Improvisation’ and ‘Caressing the Stones’. Care and caressing are topics connecting performances in these videos. A performer caresses the lávvu (fireplace in the Northern Sami language) while considering protecting this wooden structure that provides continuous groups of people. Another scene shows the author caressing the river stones with a brush. These scenes were produced in the context of the project Dialogues and Encounters in the Arctic, a project funded by Interreg Nord and the Lapland regional council. The project was led by the Sámi Education Institute (Finland), with collaborators such as Umeå University (Sweden) and the University of Lapland (Finland). We refrain from using the term ‘Lapland’ in this article and instead refer to specific place names. Challenges are presented with the names of locations, especially when using the English language, because in the Finnish language we use the term ‘Lappi’ which is a little less problematic than its English translation Lapland. ‘Lappi’ refers to the administrative region of Northern Lapland, which is a larger geographical area than Sápmi, the homeland of the Indigenous Sámi people (Tervaniemi and Magga, 2018). Both the terms Lapland and ‘Lappi’ are still complex questions. The use of names in this context warrants a much broader discussion, which cannot be accommodated due to word count limitations. However, readers can refer to works such as Moran (2012, p. 5) for further insights. In addition, a recent discussion by Sámi activist Laiti (2025) provides valuable perspectives for those seeking additional references. Author Miettinen is located in ‘Lappi’, northern Finland, just outside of Sápmi. She recognises and acknowledges the Indigenous lands and strives to approach placemaking on these lands with care (Miettinen, n.d.). However, such acknowledgements have been criticised as having little more than ceremonial value (Dreyfus and Hellwig, 2023). The sixth scene, ‘Salmon War’, presents ephemeral textile art and activist performance art aimed at protesting the legal sanctioning of a Finnish environmental graffiti artist advocating for action against the disappearance of salmon from the Kemi River in northern Finland (Miettinen and Sarantou, 2021b). Activism, or artivism, is one of the essential topics of video. In this performance, we embody Indigenous salmon in the Kemijoki at Tervakari, conveying the struggle of swimming against the current in the Kemijoki.

In addition to these six artistic and performative processes, the ‘Placemaking Through Performance’ video includes short video segments of placemaking performances from different natural environments in Victoria Falls in Zimbabwe, Camps Bay Beach in South Africa, and various locations in Finland: Pyhätunturi, Tenojoki, and Pulmankijärvi. Some video sessions are autoethnographic, such as She Santa at Kemijoki or a portrait at Victoria Falls, affording opportunities for different alter egos or roleplays in the performance. She Santa tells the story of a female Santa who promotes emancipation and environmental values. Autoethnography gives space for thinking about one’s personal history, the complexity of relationships, and connections with environments. The video includes narration that explains “placemaking through performance.”

3.2 Study 2: roots stitching

Roots Stitching was a collaborative work between the sunflower seedlings and Sarantou. This section reflects on the biological agency of sunflower seedlings growing on a woolbed. These studies were conducted in various locations from Finland, Australia, and Japan, and they yielded different results based on the environments in which the seedlings performed their rhizomatic root growth to connect different layers of wool. The seedlings were provided with wool to perform stitching with their roots to create the intricate textures of a wool tapestry. Sarantou is a Namibian-born Australian who worked in academic contexts in Finland and, more recently, in Japan. In all the places she has lived, her bioart and root tapestries assist her in exploring rootlessness resulting from migration.

3.2.1 Multispecies ethnography, observations, and performance

Peers et al. (2022, p. 18) refer to deep visiting as a collaborative autoethnographic methodology for mutual flourishing. They describe deep visiting as ‘mutual receptivity, cultivated, slowly and softly—through deeply intersectional and accessible visiting—across what was, what is, and what may yet become’. The concept of deep visiting is to spend time with one another and with research participants in affirming the processes of renewal. The research with Sunflower Seedlings was a multispecies ethnography that can be understood as ethnography practised with human and non-human species (Kirksey and Helmreich, 2010). This field of research practice emerged from three areas: animal, environmental, and science and technology studies (Kirksey and Helmreich, 2010). The ethnography was based on observational and digital documentation practices, where the deep visiting of the artist-researcher with the sunflower seedlings grew into an intimate understanding of the growth and meshworking of the seedlings. Additionally, the multispecies ethnography practised in this way aligns with Pink’s (2008) visual ethnography.

The mono-directional observational relationship requires acknowledgement, yet at the same time, deeper implications for (artistic) performance became evident through the observations by the artist-researcher, which implies the seedlings had an audience (apart from being exhibited at the Gallery Hämärä at the University of Lapland in 2022). Davies (2011) implies that performance itself may be an artwork when contextual properties, such as representation and expression, form the artistic content of the study. However, performance may also refer to improvised studies in which the doing of the artwork answers these contextual properties, such as a jazz performance. Moreover, a performance can play a key role in appreciating a larger artwork by being one of many possible versions of it (Davies, 2011). Biotextile tapestry, classified as bioart, can be seen as a product of performance. Given the representational and expressive contextual qualities of stitching the lambswool and representing the stitched actions through their root meshwork, it may also be an improvised art.

3.2.2 Photographing performance by MTHs and biotextile roots stitching

The image on the right of Figure 3 depicts the stitching of sunflower seedlings. The image on the left (Figure 3) represents the digital manipulation of documentary photography to visually communicate, recognise, and acknowledge the inscriptions of the root network and the surface texture and traces (Ingold, 2018) of their performance in the woolbed. The surface traces only partly communicate the depth and labour of the performance, as several layers of hidden activity lie underneath the surface of the tapestry.

Figure 3. Co-authors of the bioart, sunflower seedlings, ‘perform’ the process of rhizomatic growth by stitching layers of Finnish lambswool into textiles resembling a tapestry. Photograph printed in Härkönen et al. (2023).

The biotextile, represented by the dried tapestry (Figure 4), illustrates the root network in a transformed state: dried and browned, in contrast to the green woolbed. Here, the sunflower seedlings have become part of the materiality of the biotextile after their live performance. They are the surface texture and traces within and of the materiality they represent. This bioart visually communicates the fragile interconnectedness of the roots and the wool and the beauty of endings and histories. The biotextile does not visually communicate the superficiality of the surface (see Ingold, 2018, p. 137), but rather the depth of life, labour (of love), and the transformation of meshworking through the woolbed. The biotextile also communicates co-authorship with MTHs.

Figure 4. “Roots stitching” bioart tapestry, co-authored by the sunflower seedlings and the author Sarantou. The biotextile is the result of the performance of bioart in its dried state. Photography by Melanie Sarantou Sarantou and Miettinen (2022).

Documentation of research processes through photography can be interpreted as performance, as explained by Holm (2008), who has used photography to document ethnographic research since the 1990s. In this context, performance serves as both a method of exploration and a means of representation. The researcher works closely and collaboratively with participants throughout the research and its representation, creating a process that can be viewed as a shared performance (Holm, 2008). The photographic documentation of the growth and development of the biotextile through observation (through a lens), and as a collaborative process and deep visiting (Peers et al., 2022) between the Sunflower Seedlings and the artist-researcher, can be interpreted and described as a performance.

3.3 Analysis

The analytical approaches used in this article are visual analysis (Studies 1 and 2) and thematic analysis (Study 1). Visual analysis examines visual elements such as line, colour, shape, and composition to understand the meaning, function, and impact of a work. It systematically considers context, purpose, and symbolism to deepen our understanding of visual representation, whether art or design. Drew and Guillemin (2014, p. 54) propose the interpretive engagement framework, which consists of five elements: the researcher, participant, image, context of production, and audiences. These elements each make a unique contribution to visual analysis, but when applied as a systematic analytical approach, they can, in combination, significantly contribute to the entire analysis.

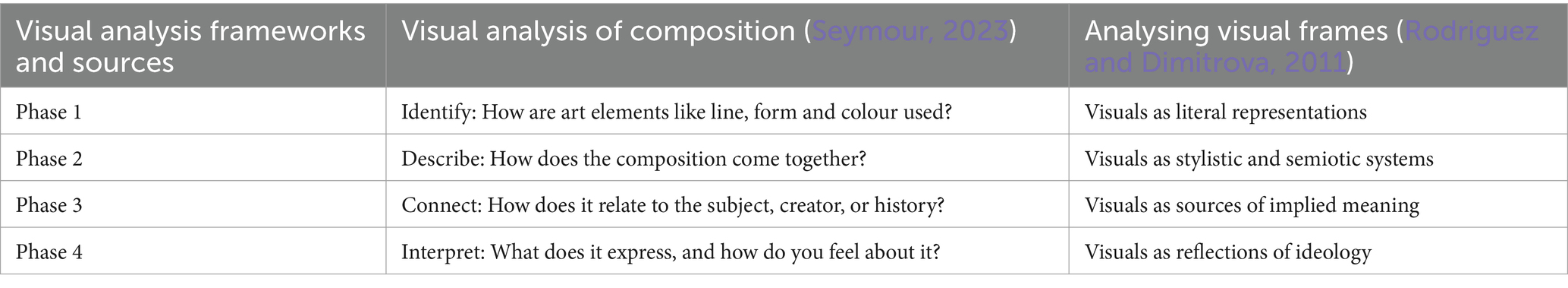

Seymour (2023) explains the process of visually analysing the composition of artworks or photographs. The process is inspired by the studies by Fry (2018) and Bell (2019), who summarise how art and photographs can be interpreted in four steps: identification, description, connection, and interpretation. Rodriguez and Dimitrova (2011) propose a similar visual analysis method, a four-level framework for identifying and analysing visual frames in which each level explains and seeks to identify unique points of view within that visual frame. Their frameworks can be used to analyse a variety of visual media or how audiences interpret them. Both indicate the systematic use of visual analysis processes in which different phases lead to gaining more comprehensive insights into the artwork or photograph.

Both frameworks are informative and have been used in the visual analysis in Studies 1 and 2. For example, in roots stitching, the analysis compares how art elements changed over 12 weeks to identify the performance of the seedlings, which enabled the artist to describe how the composition of the meshwork developed. The meshwork was created in the history of placemaking in the Bioartex Laboratory and the interactions between the artist and seedlings. On an emotional level, the interconnection between the meshwork and the artist evolved, at least for Sarantou, who experienced emotional stimuli from the developing meshwork, the slow creation of the changing colour palette from growth to demise of the seedlings.

Thematic analysis was used to analyse the transcribed data from the focus group. This analytical method identifies and analyses patterns of meaning within a dataset (Joffe, 2012). It highlights key themes significant to understanding the phenomenon being studied, ultimately showcasing the most prominent meaning of the data through clusters of similar or opposing data, which is used to constitute new themes. As Joffe (2012, p. 209) explains, ‘a theme refers to a specific pattern of meaning found in the data’. The transcribed data from the focus group interview were analysed by clustering similar content under new themes, such as placemaking and agency; while performing and documenting these performances, the natural environment and its forces impacted how and when to visualise them.

4 Findings

Placemaking in the natural environment is sensitive to co-authorship with the natural environment. The affordances in the natural environment create a deeply sensory space where we experience the geohistorical and a connection with a living ecosystem where both humans and non-humans belong. Placemaking is also used to revitalise one’s connection with the natural environment. Sometimes, there is a need to feel the connection through family-owned land. Sometimes, family grounds are lost due to conflicts, changes in the borders of nation-states, or new policies. The natural environment can enable grounding through familiarity with the location and create a healing or nurturing experience. For example, bathing, floating, or swimming in moving water, such as a river, will co-author the experience and profoundly impact embodiment and sensory place. Filmmaking used for visual communication can make this co-authorship with the environment more available for the audience. Filmmaking enables seeing, feeling, and showing, as it helps represent embodied, multisensory experience and reflect this (Paterson and Glass, 2020). Filmmaking can make co-authorship with MTH more visible when using moving images and soundscapes. Placemaking as a co-authoring practice can interact with the idea of different cosmologies, such as the planet’s origins, which Mignolo (2018) discusses. Placemaking also attempts to open us to the possibility of accepting affordances in nature and their impact on shaping and co-creating our experiences and emotional space.

Spacetimemattering through video helps in understanding the agency of the natural environment through its movements, such as the flow of the sea or the soundscape of the waterfall. Both of these can participate in the narrative of the performance by watering or moving the performing body in the direction it wants, such as in the placemaking scenes in the natural environments at Victoria Falls in Zimbabwe or Camps Bay Beach in South Africa. The natural environment and forces impact cinematography. The opening scene of the placemaking video was filmed with a drone camera, which was possible only when it was not too windy. This is a testimony to the agency of the natural environment. Following the weather created an intense dialogue with the natural forces.

4.1 Performing in the natural environment

Performance through placemaking is an artistic practice in which one uses one’s creative potential to move one’s body through the feelings, emotions, and memories that one senses from a particular place, such as a natural environment. These movements can fill a small or large space, be enacted with natural elements such as trees or water, and engage available objects. Performance through placemaking is place-specific and embodied (Wilbur, 2015). Placemaking strengthens the connection between people and the places they share. Placemaking is needed more and more because people are dislocated or newcomers to different places. Therefore, it is essential to create new strategies for people to feel a meaningful connection between each other and the places they share. We may change the places in which we live several times. Hence, we lose the traditional knowledge stored by our parents or grandparents, such as how to find mushrooms, how to find blueberries in the nearby forest, or how to familiarise ourselves with natural landmarks. These art-based methods can be meaningful ways to create familiarity and meaning with specific locations and connections between places and the people sharing them. Artistic processes around placemaking create feelings and memories of strong intergenerational connections with particular locations, and these can carry immense meaning for placemaking and connection with the place (Rico and Jennings, 2012).

It was the whole trip—somehow driving this way and seeing all the colours, lights, and sceneries was pretty important and amazing. Somehow sensitising you all the time that, okay, you are seeing something, and then more and more. I think it was significant to see those birds flying. This riekko (willow grouse). I felt it’s somehow mystical how the land and the sky somehow mixed. (Excerpt from a group discussion, 2021)

This artistic research project explored the role of human and non-human agency, interaction, and temporality in performance and the environment. Artistic action can connect our bodies with the surrounding ecosystem and remind us of this connection—being embodied and part-of-nature creatures (Gibbs, 2014). Some of the performances are in new locations where one is trying to make sense, create meaning, or develop respect for the place, such as Victoria Falls, Cape Town, or other locations that one wants to preserve and protect. These embodied and artistic interactions create new affordances for performing in and learning about the natural environment. Placemaking could be used to revitalise the earth’s connection and ground us. Some locations, such as Pulmankijärvi, have unique biodiversity. Sense can be enhanced through placemaking, and performances can bring together true and imagined stories through the signs and signals observed in a natural environment.

I realised it was so important to be there and enjoy that incredible landscape that it was the moment where I should put things out of my mind and just focus on being there. Because it was so incredibly special. (Excerpt from a group discussion, 2021)

Artistic research and artistic thinking are used in several ways during the process: performing; documenting; creating photographs and videos; narrating the performances; discussing the processes; opening up spaces for improvisation, iteration, and interpretation; and creating meaning for the “Placemaking Through Performance.”

It looked flat. You couldn’t really know how deep the snow was, so as I started interacting with the snow and walking, I realised it was deep. Then I started thinking, oh it’s hard, and then I started thinking about this metaphor that I explained earlier. But I was impressed by how quickly you start getting these thoughts, images and ideas. But in a way, using art-based methods is also a more embodied experience to generate ideas. It just happens. (Excerpt from a group discussion, 2021)

Placemaking through performance is a process. We are still investigating, studying, and figuring out all kinds of meanings relating to it, including what can be done with it and what kinds of contexts it can be applied to. It has already proved its potential, and we are continually working with it. Filmmaking can help the audience understand the process and utilise their senses when spectating. The idea of the project was to present feelings related to the natural environment with embodied actions and movements through performances in specific places that felt special and specific. The places were selected intuitively. This embodied performance sensitised us to the location so that we could hear, see, smell, listen to, and feel the natural environment. Using all the senses is integral to performing in a natural environment. Doing so enables the discovery of affordances, sensitising oneself to create connections with past generations and co-authoring with non-humans such as plants, water, and animals. Intra-action during placemaking creates an embodied personal and a shared space between humans and non-humans (Barad, 2007). Intra-action proposes questions of co-authorship during placemaking. The flow and soundscape of the natural environment play a role and are documented in the video. The rhythm, movement, and silence are co-created with entities in the natural environment.

Vera (2021) proposes land-based design approaches to un-design the colonial space in the university context. Vera acknowledges herself and the land in diverse worlds, where different ways of being and knowing can build community and transform realities into possibilities of change. Vera (2021) presents a design process that dismantles colonial structures and separates individual and universal structures; understanding place-specific history and the natural environment enabled us, the participants, to feel a connection to the land. Vera (2021) points out that decolonising ourselves gives us a respectful way of looking at a world where many worlds can fit. Similarly, creative placemaking can bring the idea of pluriverse and place-specific knowledge into a dialogue and enable us to know things new and have the possibility of transformation.

In this context, it is essential to acknowledge how the intersection of whiteness and placemaking is intertwined with the social constructions of race and identity. It is necessary not to overlook the implications of race, especially whiteness, and how this shapes our visual communication, experiences, and practices. Visual communication can contribute to power dynamics; awareness of and dismantling these dynamics is essential (Thompson, 2017).

Fari (2023) studied site-orientated performance while documenting how the body can be both in front of and behind the camera while trying to create a deep awareness of the place. While Fari (2023) investigates the narrative agency of the camera, Miettinen investigates the agency of the place where she is performing (Björn and Miettinen, 2024). Fari’s (2023) artistic practice is similar to the first author’s and highlights the challenge of providing and understanding the agency of all participating in both performing and visual communication. Placemaking can enable a platform of co-authorship and communication, but more study needs to be done to develop the agency of MTHs and the means for their communication. The practice itself enables a strong linkage and rooting with the natural environment, and the affordances it offers open opportunities for this agency and visual communication.

4.2 Bioart and performance

The finding regarding the biotextile is that this form of bioart-making can be understood as a performance by the sunflower seedlings, which later transformed into a wool tapestry of dried roots. As Härkönen et al. (2023) posit, it is necessary to identify the entity to which mandatory copyright criteria are applied. The performance of the roots stitching entitles the Sunflower Seedlings to be the performers of the stitching process. Hence, they have authorship and control as long as the performances last, as explained by Härkönen et al. (2023, Section 5.1, p. 107). However, the photography of these processes has implications for authorship as artworks.

The findings also revealed that it is essential to acknowledge the agency of the roots while stitching and its control of the action, hence having the authorship of the performance. The seedlings were autonomous, living MTHs, partly independent of human input, although only temporarily. In addition, the agency revealed by the seedlings to grow through layers of paper, and then, a woolbed revealed that their growth was sometimes beyond the control of the artist-researcher. Regarding bioart, Kac (2021, p. 1367) reminds us that ‘art that manipulates or creates life must be pursued with great care, with acknowledgement of the complex issues it raises and, above all, with a commitment to respect, nurture, and love the life created’. The question of nurturing is vital in this case, as the role of the artist-researcher was nurturing, enabling the seedlings to be in control and having authorship of the process and performance. The sunflower seedlings had agency, but as Ingold (2007, p. 1) posits, they were also ‘caught up in these currents of the lifeworld… not fixed attributes of matter but are processual and relational’, which is reflected in the transformative process of the biotextile. From having authorship through performative growth to co-authorship in the dead state of the root and wool tapestry, the performance of the biotextile was methodical and contextual. This outcome contrasts with additional biotextiles that transformed differently into new performative growth and ongoing (slow) live processes of rot and decay.

5 Discussion

A critical framework emerged from the studies based on applied learning, self-reflection, and rational discourse stimulated by visual communication through filmmaking and photography. Our framework addresses active collaboration between humans and MTHs and how humans can deterritorialise representations through visual communication. Visual communication facilitates the use of the senses by both the authors and the audience. Filmmaking can follow the movement of MTHs and enables, for example, the use of audio, which gives room to the sounds of nature and demonstrates its independence from human impact. The sounds of wind and water are important soundscapes and independent authors in placemaking. We present the following framework:

5.1 Placemaking

Our performances with nature in various southern and northern environments relied on improvisation and intuition to explore and better understand the affordances of nature, enabling co-authorship with it. Wilmot (2020) discusses documentary filmmaking as a placemaking practice, arguing that it can be used to examine the relationships between place, a sense of belonging, the notions of home, and away, and the conditions of modernity and post-colonialism. Filmmaking was part of the placemaking performance to communicate better the authorship of nature and sensory levels of placemaking. The reflection that filmmaking creates when used with placemaking enables new ways of creating knowledge, such as new ways of knowing and understanding the authorship of nature.

Another insight into placemaking is presented by Lilja (2022, p. 206). who posits that ‘movement as such produces place’. The slow meshworking of the MTH growth movements of the sunflower seedlings was placemaking in the Bioartex Laboratory at the University of Lapland. Similarly, studies of seedlings were conducted in South Australia and Japan, where they also engaged in placemaking. The movement of seedlings reacting to being and growing within one another’s environment, captured by time-lapse photography as a documentation tool, illustrates their placemaking. The co-performance created during the photographic documentation (Holm, 2008) between the seedlings, as research participants, and the artist-researcher added another dimension to the placemaking activities in the laboratory and elsewhere.

5.2 Material vs. materiality

Ingold (2007, p. 1) critically investigates the term ‘materiality’. He explains that it refers to ‘the stuff things are made of’ and ‘the stuff we want to understand’. Exemplified by the biotextile (or root tapestry), the Finnish lambswool and the roots (living or dead) are the materialities resulting from our co-authorship with MTHs. In the example of the enigma performance, the materials are the textile wrapped around and holding the heavy birch wood on the soft, light snow in northern Finland. The weight and texture of the natural materials, and their environment, resisted movement and placemaking. Visually, the resistance the materials caused to the performance was not evident at first, yet the video documentation visually communicated the difficulty of the performance and the symbolic flagellation of hauling the heavy bundle of wood through the snow.

Ingold (2012, p. 438; cf. Deleuze and Guattari, 1987, p. 454) explains materiality as the connection to consciousness. As artist-researchers, the authors investigated their practice in the context of performative ontology. Being immersed in the practice and doing the artistic practice that was corporeal and sensory enabled both authors to develop a methodology where the MTHs participated, documenting these processes and then developing artistic outcomes that could be visually communicated to the audience. The concept of intra-action (Barad, 2007) was exploited and worked to offer new information on artistic practice and visual communication about and with MTHs. Intra-action enables the co-creation and co-authorship between humans and MTHs during placemaking. Barad (2007, p. 392) emphasises the importance of responsibility and accountability in ethical relationships with others. This principle extends to artistic practice, requiring responsibility and humility in intra-actions between humans and MTHs, particularly when engaging with Indigenous places that demand respect—whether it be Sápmi or other vulnerable locations. Such respect cannot be overlooked or forgotten.

Barad (2017, p. 106) argues through their notion of spacetimemattering that entanglements are shaped by historical, political, and ethical dimensions. Entanglements signify the fundamental interconnectedness and co-composition of all matter and meaning, challenging traditional separations between objects, subjects, and their spatiotemporal dimensions. The biotextile created by the seedlings is a metaphor for how conditions required by MTHs and humans are entangled. The entanglements of the biotextile connected diverse spaces, times, and materialities into a co-authored expression, while digital expressions, also co-created with MTHs, facilitated the visual communications of such entanglements.

5.3 Digital technologies

Digital technologies enabled the documentation, digital inscription, and material understanding of the performances by (the study Roots Stitching) and with (the study video “Placemaking Through Performance”) the natural environment. The documentation of the performances by MTHs and humans captured by the digital video and photographs, and the performative aspects involved in capturing and creating video and photograph, were placemaking, produced by the movement that creates a place, as Lilja (2022) explains. In the example of the biotextile, digital technologies created material understanding through the digital tracing around the temporal root activity, thereby capturing the performance in a format that can contribute to the sedimentation of knowledge, as it will be laid down in layers of documentation and investigation into the future.

As efficient pedagogical tools, digital technologies can enable critical thinking by identifying and cultivating critical thinking and enhancing the continuous flow of information and knowledge (Mhlongo et al., 2023). Visual and digital documentation outcomes, such as photographs and videos, should be critically considered through careful connection to history and context, or text and context (Sontag, 2018, 175). This article presents examples of how visual documentation and images can be dealt with in research. For example, Study 1 used text captured through a focus group discussion to create more profound insights into the contexts of the images through textual data from the 57-min focus group. Study 2, in contrast, used systematic photo and video documentation over an extended 12-week period, including time-lapse photography, to capture the history of the seedlings’ sprouting, growth, movements, and stitching of the wool, including rotting and/or death, which were interpreted as performances due to the characteristics of their movements, which were stimulated by their direct environment.

The use of digital technologies, therefore, can visualise and communicate the boundaries we must critically reflect on as humans, as well as the reflective and learning capacities we need to nurture to enable effective interactions with MTHs. According to Giaccardi and Redström (2020), design processes are no longer isolated from production; instead, development and deployment are fully integrated. Technologies actively ‘learn’ during consumption, constantly evolving, adapting, and transforming in the process.

Thompson (2017) provides another perspective by describing the ontological turn in the context of sound studies. She examines how sound can be understood through the nature of being and existence, not only through representation. Sound can be a medium of communication and an aspect of social and cultural reality. Similarly, digital technologies are used for visual communication and to shape social relations, identities, and power structures. This question should be investigated and scrutinised from a decolonial perspective (Thompson, 2017).

5.4 Improvisation as a respectful practice

Improvisation as such is wayfinding (Ingold, 2004), which refers to making the best of and coping with the affordances of a given environment (Sarantou and Miettinen, 2017). With a sensitive and respectful attitude towards walking as wayfinding (Instone, 2015), the affordances within nature and natural environments may be better recognised for their fragility and limitations. Lilja (2022, pp. 201–204) emphasises the enactment of attentive walking to critically reflect on our extractive mindsets, juxtaposed with our human proximity to and interconnectedness with ‘mineralness’ as a part of the natural constitution of our bodies. At the same time, mineralness signals an additional dimension with the interconnection of mineral matter through digital technologies. Lilja (2022) explains that due to humans’ contribution to substantial material devastation and heavy resource use, ‘mineralness can be understood as an attribute to help us [re]think the mineral beyond the subject/object divide… but also its nature culture entanglement as the mineral constitution of bodies, including the human’ (pp. 102–104). Through improvisatory practices, often born from a lack of resources and driven by thriftiness, as observed through craft-design practices in Namibia (Sarantou, 2014), our attentiveness to nature–culture affordances can remind us of our critical examination of our human boundaries and the limitations of our natural resources. Our awareness of our mineralness and interconnectedness should stimulate humans’ awareness of more respectful wayfaring with MTHs, including digital technologies.

6 Conclusion

Underpinned by ABR and comparative analysis, this article has presented two artistic studies, ‘filming placemaking through performance’ and ‘roots stitching’, to develop a critical framework based on applied learning, self-reflection, and rational discourse. The critical framework aims to enhance practices for visually communicating with and through MTHs. The studies showcase the digital documentation of performance with and by nature. One study illustrates the interaction between MTHs and humans, while the second focuses on MTH performance through a biotextile. Issues of authorship and visual communication are explored, and a framework is proposed that identifies the elements of placemaking and the roles of material, digital technologies, and respectful improvisatory practices. The visual communication of placemaking and the places gains authorship through the flow of the ecosystem: moving water, sounds of water, and wind. However, as Carbonell (2022) reminds us, we need a close attunement to MTHs to challenge our exceptionalism in natural environments. More prominently, this article concludes that the critical framework for visual communication by and with MTHs enables humans to see, grasp., and make sense of that which is less obvious—that which our consumer and other habits territorialise—and that which we urgently need to understand through reflective practices, assisted by performance partners such as MTHs and digital technologies.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because photographic copyright. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to c2FyYW50b3VAZGVzaWduLmt5dXNodS11LmFjLmpw.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by University of Lapland Research Ethics Committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

SM: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MS: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The research, titled “Action on the Margin: Arts as Social Sculpture” (AMASS, grant number 870621), was funded by the European Commission Horizon 2020 programme. The regional development project titled “Dialogues and Encounters in the Arctic” was funded by European Regional Development Fund (ERDF).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank everyone involved in performing, placemaking, and filmmaking in the Placemaking Through Performance videos and Roots Stitching. We want to acknowledge AskGPT for its assistance in providing examples for our information on complex topics discussed in this paper. OpenAI. (2023). AskGPT. Retrieved from [https://askgpt.app/chat].

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Bacharach, S., and Tollefsen, D. (2015). Co‐Authorship, Multiple Authorship, and Posthumous Authorship: A Reply to Hick. J. Aesthet. Art Crit. 73, 331–334.

Barab, S., and Squire, K. (2004). Design-based research: putting a stake in the ground. J. Learn. Sci. 13, 1–14. doi: 10.1207/s15327809jls1301_1

Barad, K. (2003). Posthumanist performativity: toward an understanding of how matter comes to matter. Signs 28, 801–831. doi: 10.1086/345321

Barad, K. (2007). Meeting the universe Halfway: Quantum physics and the entanglement of matter and meaning, Durham [N.C.]: Duke University Press.

Barad, K. (2017). “No small matter: mushroom clouds, ecologies of nothingness, and strange topologies of spacetimemattering” in Arts of living on a damaged planet: Ghosts and monsters of the Anthropocene. eds. A. Tsing, H. Swanson, E. Gan, and N. Bubandt (Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press), G103–G120.

Bell, C. (2019). Significant form. Burlingt. Mag. Connoisseurs 34(195), 257–257. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/860741 (Accessed 15, December 2024).

Björn, E., and Miettinen, S. (2024). “Artistic cartographies and place-based service design for making places” in Tourism interventions. eds. R. K. Isaac, J. Nawijn, J. Farkić, and J. Klijs (London: Routledge), 83–96.

Björn, E., Miettinen, S., and Alhonsuo, M. (2023). “Place-based service design through placemaking and performance” in ServDes 2023: Entanglements and flows: Service encounters and meanings: Conference proceedings. eds. C. Cipolla, C. Mont’Alvão, L. Farias, and M. Quaresma (Linköping: Linköping University Electronic Press), 1–22.

Carbonell, I. M. (2022). Attuning to the Pluriverse: Documentary filmmaking methods, environmental disasters, & the more-than-human. Santa Cruz: University of California.

Deleuze, G., and Guattari, F. (1987). A thousand plateaus Capitalism and Schizophrenia (B. Massumi, trans.). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Drew, S., and Guillemin, M. (2014). From photographs to findings: visual meaning-making and interpretive engagement in the analysis of participant-generated images. Vis. Stud. 29, 54–67. doi: 10.1080/1472586X.2014.862994

Dreyfus, S., and Hellwig, A. F. J. (2023). Meaningful rituals: a linguistic analysis of acknowledgements of country. J. Aust. Stud. 47, 590–610. doi: 10.1080/14443058.2023.2236618

Fari, N. S. (2023). Performing while documenting or how to enhance the narrative agency of a camera. Theatre, Dance Perform. Train. 14, 46–56. doi: 10.1080/19443927.2022.2162572

Foster, S., Paterson Kinniburgh, J., and Country, W. (2020). “There’s no place like (without) country” in Placemaking fundamentals for the built environment. eds. D. Hes and C. Hernandez-Santin (Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan).

Fry, R. (2018). Line as a means of expression in modern art. Burlingt. Mag. Connoisseurs 33(189), 201–208. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/860829 (Accessed 15 December 2024).

Giaccardi, E., and Redström, J. (2020). Technology and more-than-human design. Des. Issues 36, 33–44. doi: 10.1162/desi_a_00612

Gibbs, L. (2014). Arts-science collaboration, embodied research methods, and the politics of belonging: ‘SiteWorks’ and the Shoalhaven River, Australia. Cult. Geogr. 21, 207–227. doi: 10.1177/1474474013487484

Grodach, C. (2011). Art spaces in community and economic development: connections to neighborhoods, artists, and the cultural economy. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 31, 74–85. doi: 10.1177/0739456X10391668

Günay, M. (2021). Design in visual communication. Art Des. Rev. 9, 109–122. doi: 10.4236/adr.2021.92010

Härkönen, H., Ballardini, R., Pietarinen, H., and Sarantou, M. (2023). Nature’s own intellectual creation: copyright in creative expressions of bioart. NuArt J. Stavanger, 4, 100–110.

Henke, S., Mersch, D., van der Meulen, N., Wiesel, J., and Strässle, T. (2020). Manifesto of artistic research: A defense against its advocates : Diaphanes Verlag.

Henriksen, D., Creely, E., and Mehta, R. (2022). Rethinking the politics of creativity: posthumanism, indigeneity, and creativity beyond the Western Anthropocene. Qual. Inq. 28, 465–475. doi: 10.1177/10778004211065813

Hick, D. H. (2014). Authorship, co authorship, and multiple authorship. J. Aesthet. Art Crit. 72, 147–156. doi: 10.1111/jaac.12075

Hultin, L. (2019). On becoming a sociomaterial researcher: exploring epistemological practices grounded in a relational, performative ontology. Inf. Organ. 29, 91–104. doi: 10.1016/j.infoandorg.2019.04.004

Ingold, T. (2004). Culture on the ground: the world perceived through the feet. J. Mater. Cult. 9, 315–340. doi: 10.1177/1359183504046896

Ingold, T. (2007). Materials against materiality. Archaeol. Dialogues 14, 1–16. doi: 10.1017/S1380203807002127

Ingold, T. (2012). Toward an ecology of materials. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 41, 427–442. doi: 10.1146/annurev-anthro-081309-145920

Ingold, T. (2018). Surface textures: the ground and the page. Philol. Q. 97, 137–154. Available at: https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/surface-textures-ground-page/docview/2099390485/se-2

Instone, L. (2015). “Walking as respectful wayfinding in an uncertain age,” in Manifesto for living in the Anthropocene, eds. G. Katherine, D. Bird Rose, and R. Fincher (Santa Barbara: Punctum Books), 133–138. Available at: https://nova.newcastle.edu.au/vital/access/services/Download/uon:23672/ATTACHMENT02 (Accessed 15, December 2024).

Joffe, H. (2012). “Thematic analysis,” in Qualitative research methods in mental health and psychotherapy: A guide for students and practitioners, eds. D. Harper and A. Thompson (Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell), 209–223.

Josephson, S., Kelly, J., and Smith, K. (Eds.) (2020). Handbook of visual communication. Theory, Methods, and Media. New York, NY: Routledge.

Kelly, J. D., Josephson, S., and Smith, K. (Eds.) (2020). Visual Communication Dominates the 21st Century. In: Understanding Visual Communication. New York: Academic Press. xvii–xx.

Kirksey, S. E., and Helmreich, S. (2010). The emergence of multispecies ethnography. Cult. Anthropol. 25, 545–576. doi: 10.1111/j.1548-1360.2010.01069.x

Koskinen, I., Zimmerman, J., Binder, T., Redstrom, J., and Wensveen, S. (2011). Design research through practice: From the lab, field, and showroom. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Laiti, P. (2025). Why are we still calling it “Lapland”? Available at: https://www.instagram.com/p/DE0Oc8NtCc2/?img_index=5

Leavy, P. (2017). Research design: Quantitative, qualitative, mixed methods, arts-based, and community-based participatory research approaches. New York: Guilford Publications.

Liebenberg, N. (2024). Weeds in the greenhouse: curating posthuman engagements. Res. Arts Educ. 2024, 105–119. doi: 10.54916/rae.145486

Lilja, P. (2022). “Attentive walking: encountering mineralness” in Pathways: Exploring the routes of a movement heritage. eds. D. Svensson, K. Saltzman, and S. Sörlin (Winwick, Cambridgeshire: White Horse Press), 201–218.

Lippard, L. R. (1997). The lure of the local: Senses of place in a multicentered society. New York: New Press.

McEwan, C. (2023). Multispecies storytelling in botanical worlds: the creative agencies of plants in contested ecologies. Environ. Plan. E: Nat. Space 6, 1114–1137. doi: 10.1177/25148486221110755

Mhlongo, S., Mbatha, K., Ramatsetse, B., and Dlamini, R. (2023). Challenges, opportunities, and prospects of adopting and using smart digital technologies in learning environments: an iterative review. Heliyon 9:e16348. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e16348

Miettinen, S. (n.d.). “Civic education and learning through placemaking in Sápmi” in Co-designing civic education for the circumpolar north. eds. J. C. Young, M. Koutnik, and N. C. Fabbi (Seattle: University of Washington).

Miettinen, S., Mikkonen, E., dos Santos, M. C. L., and Sarantou, M. (2022). “Introduction: artistic cartographies and design explorations towards the pluriverse” in Artistic Cartography and Design Explorations Towards the Pluriverse eds. S. Miettinen, E. Mikkonen, M. C. L. dos Santos, and M. Sarantou (Routledge), 1–14.

Miettinen, S., and Sarantou, M. (2021a). “Forest play: global north and south” in Dialogista Vaikuttamista: Yhteisöllistä Taidekasvatusta Pohjoisessa eds. M. Huhmarniemi, S. Wallenius-Korkalo, and T. Jokela (Rovaniemi: Lapin Yliopisto), 119–122.

Miettinen, S., and Sarantou, M. (2021b). “Five salmon and two fish (viisi lohta ja kaksi kalaa)” in Documents of socially engaged art eds. R. Vella and M. Sarantou (Viseu, Portugal: International Society for Education through art (InSEA)), 37–47.

Mignolo, W. D. (2018). Decoloniality and phenomenology: The geopolitics of knowing and epistemic/ontological colonial differences. JSP: J. Specul. Philos. 32, 360–387.

Mitchell, R. (2010). Bioart and the Vitality of Media. University of Washington Press. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvcwnfnr

Moran, D. J. (2012). Whose land is Lapland? The Nellim case: a study of the divergent claims of forestry, reindeer herding and indigenous rights in northern Finland. University of Helsinki Faculty of Social Sciences Sociology. Available at: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/14924748.pdf (Accessed 1, April 2024).

Moriarty, S., and Barbatsis, G. (2005). “Introduction: from an oak to a stand of aspen: visual communication theory mapped as rhizome analysis” in Handbook of visual communication: Theory, methods, and media. eds. K. Smith, S. Moriarty, G. Barbatsis, and K. Kenney (New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers), xi–xxii.

Paasi, A. (2003). Region and place: regional identity in question. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 27, 475–485. doi: 10.1191/0309132503ph439pr

Paterson, M., and Glass, M. R. (2020). Seeing, feeling, and showing ‘bodies-in-place’: exploring reflexivity and the multisensory body through videography. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 21, 1–24. doi: 10.1080/14649365.2018.1433866

Peers, D., Joseph, J., McGuire-Adams, T., Eales, L., Fawaz, N. V., Chen, C., et al. (2022). We become gardens: intersectional methodologies for mutual flourishing. Leis./Loisir 47, 27–47. doi: 10.1080/14927713.2022.2141836

Pelizzon, A., Poelina, A., Akhtar-Khavari, A., Clark, C., Laborde, S., Macpherson, E., et al. (2021). Yoongoorrookoo: The emergence of ancestral personhood. Griffith Law Rev. 30, 505–529. doi: 10.1080/10383441.2021.1996882

Pinar, W. F., Irwin, R. L., and de Cosson, A. (2004). A/r/tography: Rendering self through arts-based living inquiry. Vancouver, Canada: Pacific Educational Press.

Pink, S. (2008). An urban tour: the sensory sociality of ethnographic place-making. Ethnography 9, 175–196. doi: 10.1177/1466138108089467

Plank, M. (2020). What are biofabrics and how sustainable are they? Innovative, common objective. Available at: https://www.commonobjective.co/article/what-are-biofabrics-and-how-sustainable-are-they (Accessed 1, April 2024).

Plow, B. (2015). Understanding artists’ relationships to urban creative placemaking through documentary storytelling. J. Urban Cult. Res. 10, 24–39. doi: 10.58837/CHULA.JUCR.10.1.2

Rico, G., and Jennings, M. K. (2012). The intergenerational transmission of contending place identities. Polit. Psychol. 33, 723–742. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9221.2012.00894.x

Rodriguez, L., and Dimitrova, D. V. (2011). The levels of visual framing. J. Vis. Lit. 30, 48–65. doi: 10.1080/23796529.2011.11674684

Sarantou, M. A. C. (2014). Namibian narratives: postcolonial identities in craft and design [doctoral dissertation]. University of South Australia. Available at: https://hdl.handle.net/11541.2/128656 (Accessed 6, May 2024).

Sarantou, M. A., and Miettinen, S. A. (2017). “The connective role of improvisation in dealing with uncertainty during invention and design processes,” in Conference proceedings research perspectives on creative intersections, design management academy, Hong Kong, eds. E. Bohemia, C. Bontde, and L. S. Holm, Vol. 4, 1171–1186. Available at: https://www.designresearchsociety.org/articles/design-management-academy-2017-conferee-proceedings-available-online (Accessed 15, December 2024).