94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Commun., 10 June 2024

Sec. Media Governance and the Public Sphere

Volume 9 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2024.1424096

This article is part of the Research TopicSelf-Regulation and Co-Regulation as Governance SolutionsView all 8 articles

Within the European Union, the pluralist polarized journalistic model suggests the presence of journalistic cultures rooted in the connections between political parties and media organizations. In this classical framework, the state exerts significant intervention to influence a media system characterized by lower levels of professionalization. In this regard, Spain serves as a well-examined example of a pluralist polarized Western democracy. Our study entails a systematic review based on two distinct dimensions. Firstly, we scrutinized all legal documents pertaining to media regulation in Spain published between the Spanish transition and the present 1977–2024. From this perspective, we propose a chronological evolution to categorize this extensive collection of norms. Secondly, we complement our primary source assessment with an examination of secondary sources to validate the proposed evolution. Our findings indicate that the Spanish media regulation is evolving due to two pivotal factors: the influence of the European Union and the preservation of the narrative established during the transition to democracy. While contemporary communication grapples with issues such as the rise of artificial intelligence, journalistic instability, algorithmic communication, and fragmented user consumption, these areas are only addressed peripherally within the Spanish media normative context.

Communication policies are created and implemented under the influence of the economic, political, social, and cultural context (Mastrini and Loreti, 2009). At the economic level, as these authors explain, communication policies confront issues such as ownership concentration, or the impact of information and communication technologies and the readjustment of the media market. Indeed, there has been a gradual de-capitalization of advertising, especially from major media, in favor of social networks (Barredo Ibáñez, 2021). But also, new media have emerged that take advantage of the reduction in the costs of informative production and depend on a diversification of economic sources, as explained in the cited work.

Politically, regulatory frameworks are impacted by issues such as the growing difficulty for national states to establish communication policies (Mastrini and Loreti, 2009), the rise of populist candidates—partly aided by the absence of social media editorial filters—proposing reactionary agendas and threats to democracy as a political system (Eichengreen, 2018; Galston, 2018), and the increasing influence of international institutions in defining policies of mandatory compliance, such as supranational agreements.

Culturally, communication policies depend largely on the distinctive attributes and the particular development of each journalistic culture. This journalistic culture concentrates the identity traits of journalists within the collective they belong to, visible both in professional orientations (values, attitudes, and convictions) as well as in practices and works evident in journalistic products and texts (Hanitzsch, 2007). Journalistic cultures introduce specific mediations with the restrictions imposed from the political or economic domains, as well as with the different conceptualizations or impositions of press freedom (Hanusch and Hanitzsch, 2019).

In this regard, the journalistic culture of Spain fits into the so-called pluralist polarized media system (Hallin and Mancini, 2004). This system is characterized by high political polarization, state intervention, and the existence of a strong link between media groups and political parties, which reduces independence and public knowledge about politics, among others. Globalization and market competition have not limited parallelism in Spain, where the media tend to respond to ideological positions and approach certain parties and political ideas (Baumgartner and Chaqués Bonafont, 2015).

The Spanish journalistic culture is explained by its political background: from 1936 to 1975, journalists were assimilating the regulatory principles imposed by the authoritarian political model of Francisco Franco’s dictatorship (Sevillano, 1998). This dictatorship had various internal evolutionary stages, which will be explained later in this article. However, from approximately 1977 to 1982, the political Transition from the dictatorship to democracy took place, conceived as a pact among the country’s elites (Aguilar and Sánchez-Cuenca, 2009), with the aim of agreeing on the foundations of democracy as an evolution of the Francoist political system. Authors such as Barredo Ibáñez (2013) refer to this moment as “second phase or integrated Francoism” (p. 48), inasmuch as numerous principles of the authoritarian model were maintained, or in the words of Ruiz-Huerta (2009), the “perverse legacies of Francoism” (p. 122).

From this angle, Spanish journalists assumed an unwritten imposition of amnesia about the recent past. Issues such as the democratic coexistence during the Second Spanish Republic (1931–1939), the coup d’état led by Francisco Franco in collusion with the country’s economic oligarchies, or the responsibilities of the Francoist hierarchies in the systematic assassinations or brutalities of the Civil War, were taboo subjects assimilated through the pact of oblivion (Brunner, 2009). Another journalistic taboo forged during the Transition to democracy was the monarchy, considered as a democratizing element and, therefore, a factor that the editors of the main media informatively shielded to safeguard the emerging political system (Zugasti, 2007).

In any case, the Transition ensured at least three main actions relevant to the innovation of the Spanish journalistic culture, such as, firstly, the guarantee and establishment of press freedom (Martín, 2003; Aguilar and Sánchez-Cuenca, 2009). Secondly, in 1938, before the conclusion of the Civil War, the Francoist apparatus created the Press Chain of the Movement (CPM), which grouped together all those media confiscated by the winning side of the dictatorship, and with which it was intended to monopolize and actively control social imaginaries and representations (Sánchez-García et al., 2021). This CPM was dismantled from 1977 onwards, in order to introduce more diverse ownership and, with it, less state interference. And thirdly, during those years, the development of democratic media and multimedia groups was enhanced.

However, this democratizing process was slow and gradual. Moragas Spà (2009) indeed indicates that, in its first years after the democratic transition, Spanish communication policies were characterized by being erratic, composing very fragmented legislation and a distribution of communication competencies that did not facilitate the preparation of legislative reforms. Similar to other countries in its environment that transitioned from authoritarian government models to democracies, such as Portugal (1974) or Grecia (1974) and that could be classified as a pluralist polarized—according to the now classic description of Hallin and Mancini (2004)—, the development of communication policies in Spain has followed in parallel the evolution of the political, media, and social system. But thinking about communication policies also involves facing and reflecting on future challenges in a context where some destabilizing transformations exist (Martín-Barbero, 2015).

In this sense, in this article, we will study in detail the regulations that have governed communication throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. The classification of these norms will allow us to effectively discern the impact they have had on the communicational field. The aim of this article, therefore, is to describe the normative evolution in Spain, analyze the impact of previous regulations on the communication landscape, and anticipate some challenges that may arise in the context of normative evolution in Spain. To achieve this, we start from an analysis from the Spanish political transition, which marked the establishment of the framework of freedoms. At the same time, we seek to examine the influence of the European Union on the Spanish normative framework and determine the challenges and possible difficulties still pending in this area. This analysis incorporates key considerations that allow examining emerging novelties that must be taken into account for the elaboration of communication policies in the future.

This article, following the procedures of other historical studies (Sánchez-García et al., 2021), is based on a bibliographic review and consultation of primary sources. It is, therefore, a non-experimental study with a descriptive scope, based on the systematic review (Arnau and Sala, 2020) of both the previous literature and, especially, the normative sources related to the regulation of communication in Spain. Specifically, we have followed the following instrumental steps to operationalize the aforementioned review, in accordance with the details provided by Codina (2018) and Xiao and Watson (2019):

1. Definition of inclusion criteria. For locating the documents to be systematized, we defined five parts, which in turn constitute the theoretical axes around which the results have been written. In the first part, we analyze the final stage of Francoism and the emerging communication policies during the transition and during the 1980s. In the second part, we advance in the evolutionary analysis of communication policies during the 1990s. The third phase focuses on examining the digital transition covering the period from 1998 to 2010. In the fourth section, we study the influence of the EU. Finally, in the fifth section, we address the pending challenges in the future of communication policies. In this way, we included works related to the five defined stages that had in some aspect total or linked to the regulation of communication in Spain. In this first point, we had a limitation: we only located texts in Spanish or English.

2. Document search. The identification of the documents was carried out in the range from 1977—the beginning year of the Spanish political Transition, as described by Aguilar and Sánchez-Cuenca (2009)—, up to 2024. The search was conducted using keywords such as “regulation + media + Spain,” or “laws + journalism + Spain,” among others. The location of the documents was carried out through Google Scholar, for academic works, and Google—for norms or primary sources. Google helps to quickly locate the content of the primary sources and identify standards by their rank and abbreviations. To search for those norms, as keywords, we used “media Spanish laws,” “Francoist Spanish media norms,” or “Spanish Transition communication laws.” Furthermore, Google provides the option to search for both old and current versions, and you can search for both words and numbers simultaneously. At the same time, the search was complemented with the online platform of the Spanish Official Bulletin, which concentrates all the laws approved by the State from 1960 onwards.

3. Organization of primary and secondary sources. Once the documents for analysis were located, they were employed around the five structuring axes mentioned.

4. Analysis and synthesis. In this final stage, we assembled a first draft through the analytical and synthetic description of the planned axes, trying to interconnect them to generate an evolutionary discourse between periods.

Despite the potential interest of the systematic review as a research technique, this method is not without methodological drawbacks. Among the perceived limitations, we find the following, which are associated with other difficulties of similar studies, such as the classic work of Sancho (1990):

a. Although we have attempted to systematize the Spanish normative corpus pertaining to the media, the truth is that there is an abundance of related documents, especially those related to jurisprudence, which, due to their high volume, could not be included in the review.

b. The three signing authors have conducted parallel searches to avoid possible omissions, although it is possible that some less-known documents may have been left out of the analysis, either due to lack of visibility within the search engines or because they are analog documents without an online replica.

c. Following the above, we note the potential access limitations, particularly for older documents.

d. Author biases, depending on their areas of knowledge or interpretive frameworks.

In this first stage, communication policies in Spain were initially conceived as mechanisms aimed at directing the operation of the Francoist communication systems (Sevillano, 1998). With the disappearance of the dictatorship, these mechanisms evolved into a set of regulations intended to eliminate the criteria of the old regime, giving way to the organization of a media system aligned with the democratic standards of Western European countries. As Europe experienced the decline of monopolies and the emergence of liberalism with the development of private television, the main challenges of the Transition in Spain focused on changing the norms that regulated the operation of the information system. In the process of redefining the role of the State in relation to the media, the intention was to replace the totalitarian model with one that respected freedom of enterprise, informative plurality, and guaranteed the basic rights of expression and information. This approach also included the re-conversion of journalism and journalists. However, despite the normative results that reflected an approach to democratic Europe, the media landscape during the transition already showed a trend toward business concentration parallel to governmental intervention in the radio and public state television. The legislation developed at that time reflected an attempt to align with European democratic principles; however, according to Moya-López (2023), what happened during the transition is the consequence of a trajectory forged throughout the 20th century. The Transition consolidated evolved dynamics that pointed toward a new phase in which media, political, and economic power converge.

To understand the communication policies that were implemented during the Spanish Transition, we have to look back at the preliminaries of the previous ones. During Francoism, communication was the object of significant government action. The early years of Francoism lacked a defined ideology but were aware of the importance of the media as persuasive mechanisms of public opinion (Sevillano, 1998). Thus, before the end of the Civil War (1936–1939), the Press Law of April 22, 1938, was approved, which established the legal basis for the strict state control of the media through prior censorship, turning information into political propaganda. As Sevillano (1998) explains, this Law turned the journalist into a vehicle supporting political action, that is, collaborators of the authority with the intention of maintaining control of the information system and social control. It is indicative of the aforementioned Law the creation of the provincial Propaganda headquarters, which could punish any writing that attacked the prestige of the nation or the regime, hindered the work of the government, or spread pernicious ideas (Art. 18). Other relevant aspects of this 1938 Law—which was in force for almost three decades—included the approval of sanctions for non-compliance with the norms dictated from the State (Art. 19). Sanctions ranged from fines, dismissal of the director, cancelation of their name in the Official Register of Journalists, and seizure of the newspaper (Art. 20). Measures and sanctions on media were agreed upon by the minister and could be appealed to the head of the Government (Art. 21). And, in extreme cases, the State could seize the media, based on the warning of a serious fault against the regime and whenever there was a repetition of previously sanctioned acts that demonstrated recidivism. The seizure was decided by the Head of Government in an unappealable motivated Decree (Art. 22).

But Francoism, in its almost four decades of existence, evolved politically as it established a new information order (Sevillano, 1998), after the defeat of the fascist allied axis in World War II. Thus, in 1945, the “Fuero de los Españoles” was approved, which established “liberalizing” rights and duties as contradictory as those stated in Article 12: “Every Spaniard may freely express their ideas as long as they do not attack the fundamental principles of the State.” In other words, this Fuero proposed a set of broad, abstract freedoms, always subject to state discretion. Since 1951, the Ministry of Communication and Tourism assumed responsibility for everything related to communication, until in 1978, the Secretary of State for Information was created by Decree. This change did not occur without first exploring other formulas that could manage communication policies (Pérez, 1979).

In 1966, the Press Law of 1966 (Law 14/1966) was approved. Also known as the Fraga Law, was named after the Minister of Information and Tourism who promoted the creation and approval of the law. This law moderated the intervention and control of the press, beginning with the gradual elimination of prior censorship, except in special situations such as the reporting of labor disputes (Art. 3). It was an apparently open-minded law, although it continued to establish moral and political limits such as those established in Article 2: respect for morality, compliance with the Law of Principles of the National Movement, maintenance of public order, among others. Previous kidnappings and administrative sanctions were still possible. However, without intending to do so, the law created an imprecise informative context that favored new informative perspectives and a space for criticism in the media.

The dismantling of Francoism began with the Political Reform Law of January 4, 1977 (Law 1/1977) Political Reform Law, which constitutes the Autonomous Body of State Social Communication Media. Subsequently, Decree Law 23/1977 of April 1 on the Restructuring of the Organs dependent on the National Council and New Legal Regime of the Associations, Officials and Patrimony of the National Movement was approved, which meant the public auction of printed media and ended the monopoly of Radio Nacional de España (RNE) with Royal Decree 2664/1977, of October 6, on the general freedom of information by broadcasting stations. Likewise, in 1975, the Official School of Journalism (which had been in force since 1941) disappeared, favoring the training of professionals in the field from Higher Education Institutions (Sánchez-García et al., 2021), a process that had begun as of 1971.

The center right UCD party (Unión de Centro Democrático) won the first democratic elections in Spain in 1977. On December 6, 1978, the Spanish Constitution was approved by referendum after negotiations and later agreement between different political parties. Thanks to the inclusion of Article 20, the Spanish media system was equated with those of Western Europe. Article 20 of the Spanish Constitution establishes the legal framework for journalists and journalism, regulating rights and freedoms, and differentiating between the right to information and freedom of expression. It includes legal instruments that protect professional secrecy and the conscience clause. However, the regulation of the conscience clause of information professionals was not extensively developed until the Organic Law 2/1997 of June 9. As for professional secrecy, it is protected by the CE in its article 20.1.d as an instrumental right. Although in 2022, a draft law on the professional secrecy of journalism [Draft Organic Law for the protection of the professional secrecy of journalism (121/000135)] was outlined, its processing has been paralyzed in 2023.

Regarding radio, Royal Decree 1233/1979, of June 8, which establishes the Transitional Technical Plan for the Public Broadcasting Sound Service in Metric Waves with Frequency Modulation, defined the technical conditions of sound broadcasting, such as frequency assignment or coverage area. It established the technical and operational bases for the development of broadcasting.

With the transition came efforts to provide some legal order to the radio sector, characterized by its legal dispersion. Thus, the reform of the audiovisual field began with the promulgation of the Radio and Television Statute on January 10, 1980 (Law 4/1980), which establishes that broadcasting and television are essential public services whose ownership corresponds to the State. In accordance with this legislation, Royal Decree 1615/1980, promulgated on July 31, gives rise to the public limited companies Televisión Española (TVE), Radio Nacional de España (RNE), and Radio Cadena Española (RCE). In Spain, the public monopoly becomes the RTVE public entity, which is an institution of public nature with its own legal personality. Two Royal Decrees (RD) of 1981 (RD 3271/1981 and RD 3302/1981) enable the provision of television repeaters and frequency modulation to the rural environment and regulate the transfer of concessions of broadcasting stations. In this progressive advance, it is also at the end of the 70s when the birth of the regional stations was forged, with the historical communities of Catalonia, Galicia, and the Basque Country being the first to have their own stations. With the first socialist government in Spain (1982–1995), the offer of public television is expanded with the Third Channel Law (1983), which enables the appearance of regional television stations, created in line with the newly inaugurated state of autonomies.

The Organic Law 10/1988, which regulates private television allowing the entry of new operators into the market, and Royal Decree 895/1988, which regulates the merger of RNE and RCE, were approved.

In the radio field, it is also worth highlighting the Law on the Regulation of Telecommunications (LOT) of 1987 (Law 31/1987), which led to a novel regulatory panorama, as it involved opening the market, with the multiplication of FM licenses. It also represented a timid approach to community policies since, although the Law had been approved a year and a half after the signing of the Accession Treaty, only in the preamble was there mention of the spirit of the European Common Market, without this being reflected in the development of the norm. For example, the Law establishes that the concessionaire of the indirect management of a station must necessarily possess Spanish nationality. This would require a modification of the norm a few years later to avoid collision with the European common market.

Spain timidly joined the neoliberal deregulatory current of European countries. Thus, while Spain opened up to market liberalization slowly but progressively and with delay compared to its European counterparts, from the European Union, specifically the European Commission, advanced in its attempt to harmonize through the publication a few months earlier of the Green Paper on Telecommunications.

The transition in the Spanish media had fostered a clear commitment to democracy, which combined a mixture of freedom of expression, technological renewal, and the incorporation of new genres, formats, and changes in the grids, all linked with the modernization of management forms in the radio sector, which would bear fruit during the 90s. After the explosion of radio concessions and after a few years of flourishing in the sector, as a consequence of the commercial unviability of many of those small new stations, the radio market suffered a strong business concentration, which led to the absorption of many of them by the large chains, so that the first major communication groups in Spain began to be consolidated.

With the arrival of the 1980s, subsequent regulations consolidated public television and allowed the creation of private and regional channels. The privatization of media in Spain was perceived internally as a move toward democracy, in contrast to the prevailing opinion in Europe, where high privatization was considered a reduction in the social function of the media. During this period, there is a definition of the role of the State in the media field without an exhaustive development of specific policies. The Transition marked the beginning of a stage in the formulation of communication policies in Spain characterized by little coherence and the passing of regulations according to emerging needs or difficulties. During the period analyzed, there is a clear tendency toward the liberalization of the sector initiated in the 80s. In addition to liberalization, Hernández Prieto (2015) highlights that, during the 80s, communication policies were strongly influenced by globalization and international governance, where the interest groups involved in the formulation of public policies grew significantly. These groups became a determining factor structuring public policies, representing a significant change for communication policies, which were already conditioned by the availability of resources, national cultural practices, and the distribution of power, among other issues.

During this time, two laws aimed at radio also stand out, intended to organize, create, and control municipal radio broadcasting stations: Law 11/1991, of April 8, on the Organization and Control of Municipal Radio Broadcasting Stations, and Royal Decree 1273/1992, which empowered municipal governments to grant concessions for the exploitation of ordinary radio broadcasting services in FM, the rest of the radio regulations were subsequently assimilated with audiovisual regulations. Regulations for satellite television were established, excluding telecommunications service from the category of public service. This implies that satellite television broadcasting is not subject to competition; one simply had to request a license from the government.

The normative context of Spain, which became part of the European Union (EU) in 1986, began to be influenced by the Union’s communication policies through Law 25/1994, which represents the transposition of the Television Without Frontiers Directive 89/552/EEC (TWFD). Since the late 80s, when that first Directive was adopted, and then throughout the 90s, there were repeated attempts in Europe to harmonize national media concentration rules in some member states. This initiative was due to the economic current driven by the globalization of markets, which motivated significant concentration processes in the sector.

Moreover, during this decade, various pioneering initiatives were carried out from the European Union aimed at monitoring pluralism, an issue that has since become a recurrent concern for European institutions. In fact, in 1992, the Commission examined the possibility of issuing a directive in the field of pluralism, which ultimately was frustrated due to opposition from all involved sectors. There were several attempts in this field and repeatedly the Commission itself emphasized on several occasions that the protection of pluralism in the media was a central task for the member states, so the role of the European institution was to complement the measures of the member states on this matter, for example, through the Recommendation on measures to promote pluralism in the media of 1999, whose impact in Spain was minimal.

However, in general terms, this is a period marked by the first adjustments of the Spanish laws to the European framework. Thus, the Royal Decree-Law 6/1996, of June 7, on the Liberalization of Telecommunications, ratified by Law 12/1997, establishes the Telecommunications Market Commission (CMT) as the independent Public Regulatory Body for national electronic communications markets and audiovisual services. Another relevant regulation is Law 22/99, which also transposes the European Directive 97/36/EC. This law shapes the legal basis and limits on television content in Spain. In addition, laws aimed at promoting new technologies in Spanish homes were enacted, such as Law 45/1995. Audiovisual legislation is the greatest example of the influence of the EU, although there are other examples such as the approval of the Organic Law 15/1999 on Data Protection repealed by the now in force Organic Law on Personal Data Protection and Guarantee of Digital Rights (Law 3/2028-LOPDGDD), which adapts Spanish legislation to the European Regulation, whose articles 85 and 86 regulate the rights of rectification on the Internet and the right to update information in digital media. The structure of the television market remained without significant changes from the 90s until 2005 with the introduction of Digital Terrestrial Television (DTT), marking an important milestone in the evolution of the sector.

From 1996 to 2004, the socialist government in Spain was replaced by the conservative right Popular Party (PP: Partido Popular) after 13 years of governance. In this period, in the field of communications, a notable aspect in the analysis of communication policies in Spain was the digital transition. This transition, which Marzal and Casero-Ripollés (2009a,b) place between 1998 and 2008, marked a significant milestone in Spain’s communication policies by opening up the sector and orienting it toward economic values. In the realm of television, digitalization is regulated by public policies that influence both public and private broadcasters.

The year 1998 is marked as the beginning of this stage due to the approval of the National Technical Plan for Digital Terrestrial Television (Royal Decree 2169/1998), which established the guidelines for spectrum distribution and scheduled the cessation of analog broadcasts, initially planned for before 2012. Private television concessionaires were also allowed to expand their licenses to enable DTT broadcasting. Thus began the transition toward digital technology with the implementation of the shared multiple channel (multiplex), which in 2002 would allow the test broadcasts of the current television channels, namely TVE1, TVE2, Antena 3, Telecinco, and Canal+. The market position of these operators would be further strengthened with the subsequent granting of DTT licenses to those same companies.

Until the implementation of the Audiovisual Law of 2010, the organization and structuring of communication policies were affected by fragility in formulation. Numerous gaps and a lack of coherence in the Spanish regulation at the end of the 20th and beginning of the 21st centuries are evident. The sparse regulations in the first decade of the 2000s paid much attention to the interests of communication groups and set up a digital scenario governed by commercial parameters that reproduced patterns of concentration. The regulation allowed for mergers and concentration in the private sector, and a departure from the public domain was detected, leaving the oversight of the sector to the National Commission of Markets and Competition (Law 3/2013, BOE of June 5, 2013) which is scarcely independent, according to Bustamante (2014).

This third stage begins with Organic Law 15/1999, of December 13, on Personal Data Protection, which applies to user data in any form that is published, something very relevant to the media. This law establishes the definition of “personal data” (Art. 3), the right to information for users during data capture mechanisms (Art. 5), and the distinction between personal data and specially protected data (Art. 7), among others.

The third stage identified, in broad terms, is characterized by liberalization and support for economic values; deregulation of ownership deepens in the name of greater privatization of the media. It is crucial to highlight the importance of the so-called digital transition and the enactment of the General Law on Audiovisual Communication in 2010 (Law 7/2010), two events that significantly reconfigure the audiovisual landscape in Spain.

Under the socialist government of José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero (2004–2011) were approved regulations for DTT and Audiovisual market. To promote DTT, Royal Decree (RD) 439/2004 of March 12 was approved, amended by RD 2268/2004, which activates Law 41/1995 of December 22 on Local Television by Terrestrial Waves. Law 10/2005 on urgent measures to promote DTT concretizes the plan from December 2004, although it establishes lax limits on concentration in radio.

Digital Terrestrial Television was first implemented in 1998 through a First National Technical Plan which proved ineffective, being relaunched in 2005 through Royal Decree 944/2005, of July 29 of the National Technical Plan for DTT that establishes conditions for switching to the digital system and allocates frequencies to the different networks (Zallo, 2010) and the National DTT Plan in 2007.

In addition, the Urgent Measures Law for DTT would remove the limit of three national coverage channels, allowing a new concession to the Mediapro group and the conversion of Canal Plus into a free-to-air channel. Finally, the transition to digital television was carried out in three phases, culminating with the definitive implementation in 2010.

During this period, laws related to cinema, the promotion of the information society, modifications to the 1988 Private Television Law, and Law 8/2009 of August 28 on the financing of RTVE were also approved. Prior to the significant changes introduced by these two Laws, in 2004, the Independent Council for the Reform of Public Media Communication (“Committee of wise men”) was created, which initiated a debate about the radio-television model and the deterioration of public media in Spain. After a lengthy process of deliberation and consultation with parties, it concluded with the need to approve a new funding structure for the public entity. It also highlighted the need for a new legal framework for the public media sector, given the existence of more than 30 legal provisions that directly affected radio-television and which resulted in incomplete regulation or poorly adapted to the new times, especially in terms of public service. And to some extent this was achieved with Law 7/2010, General of Audiovisual Communication of March 31, which transposes Directive 2007/65/EC and reorganizes the audiovisual system in Spain unifying national regulations. This legislation addresses various aspects of audiovisual media, such as public rights, plurality, transparency, cultural diversity, protection of minors, and universal accessibility. It also promotes self-regulation, prohibits covert political communications and discrimination. The Law was well received by the professional sector and citizens, who saw it as an attempt to depoliticize public media. Another important aspect is that it repealed obsolete regulations, so it can effectively be considered that the General Law of Audiovisual Communication of 2010 contributed to ending that normative dispersion, although at the same time it represented a strong advance toward concentration, by modifying the previous rule and from that moment authorizing that the same owner could hold a share portfolio in up to eight private national chains, provided they did not exceed 27% market share. This modification would pave the way for the reordering of the Spanish audiovisual sector, through the subsequent merger process that was led by Atresmedia and Mediaset (Zallo, 2010). It is also worth noting that this Law included a frequency reservation for third sector radios, so that, from that moment on, community and cultural non-profit stations have a legal framework for their development.

RD-Law 1/2009 converted into Law 7/2009 on urgent measures in the field of telecommunications enabled greater concentration in the sector (García Leiva, 2015), which was the result of the anticipated deregulation.

A few years earlier, in 2003, Law 32/2003 was approved, which repealed the initial Law 42/1995 on Cable Telecommunications and opened the market to the late development of cable telecommunications services in Spain, and in particular, the broadcasting of Digital Cable Television. The new legal framework would allow the entry of numerous operators such as ONO, Telecable, and Euskaltel, to more than a dozen that would later undergo a process of concentration.

The process of market liberalization characteristic of this stage was completed with the end of the digital transition of commercial television. Although the date initially planned for the so-called “analog switch-off” was set for 2012, it was brought forward to April 3, 2010, the date on which a new period began in which digital terrestrial television took the limelight. This marked the end of more than a decade of changes in the Spanish audiovisual model, in which chaotic legislation built on decrees and urgent measure laws was ordered, but which also led to the process of concentration in the sector.

Although there are national communication policies, in the last 15 years, a greater influence of the EU has been detected due to the rapid issuance of Directives or Regulations aimed at unifying the European regulatory framework and addressing the advance of the big tech companies, for example: in 2019, the modernization of the market rules for copyright affected online platforms such as YouTube, Facebook, and Google News, facilitating greater access to online content. The European influence is reinforced with technological advancement whose approach is multifactorial, global, and often renders national communication policies obsolete. Additionally, there is a wide dissemination of norms and programs supporting media pluralism from the EU and scant regulatory attention from Spain to the technological deluge that impacted the media system as evidenced by the establishment of regulations that are almost exclusively driven by the need to transpose European regulations.

In an initial stage, audiovisual policy in Europe focused on two objectives: the first considers technological, industrial, and economic aspects for the strategic audiovisual sector that encompasses traditional media and new technologies, with the intention of making it competitive; and the second considers aspects associated with the political and cultural dimension of communication that opened the redefinition of the European cultural project and thus strengthen cohesion (Murciano, 1996). European audiovisual policy is governed by Arts. 167 and 173 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU).

Neither the Treaty of Rome nor the TFEU -which are the main constitutive documents of the EU-attribute direct competencies in the field of audiovisual policies, but these competencies are deduced from the articles of the TFEU that allow policies to be developed in the different sectors of media and communication technologies. The legal bases are found in the TFEU in Arts. 28, 30, 34, and 35, on the free movement of goods; in Arts. 45–62, on the free movement of persons, services, and capital; in Arts. 101–109, on competition policy; in Art. 114, on technological harmonization or the use of similar technological standards in internet productions; in Art. 165, on education; in Art. 166, on vocational training; in Art. 167, on culture; in Art. 173, on industry; and in Art. 207, on common commercial policy.

The current EU approach to media establishes actions related to disinformation: the 2018 Code of Practice on Disinformation strengthened in 2022, the European Action Plan on Media and Audiovisuals focused on boosting European media and maintaining cultural and technological autonomy in print and online media, radio, and audiovisual services (2020), the Directive on audiovisual media services (EU Directive 2018/1808 of November 14), or the Media Pluralism Monitor and the European Film Forum (2020 and 2021).

The most important European regulation and that which has had the most impact on the Spanish media system was the 2007 Audiovisual Media Directive, which becomes the LGCA 2010, later revised in the EU in 2018 and whose approval occurred in Spain during 2022.

One of the areas where European activity has been most prolific in terms of communication policies is in the field of disinformation, through the launch of numerous regulatory initiatives aimed at curbing its impact, by developing its framework of principles and solutions that demonstrate the European governance’s intention to address it. In addition to binding regulations, the European Union has approved in the last 10 years more than 30 recommendations, communications, reports, resolutions, and legislative proposals, among other modalities, aimed at curbing disinformation, confirming the concern of European bodies before this systemic problem (Fernández and Cea, 2023).

In this sense, one of the European regulations expected to have a significant impact on the media environment is the Digital Services Act (DSA) of the European Union, dated November 16, 2022, which proposes a European regulatory context for online intermediaries (EBU, 2023), which will also become mandatory from 2024. The DSA encourages public-private collaboration to favor a safer online ecosystem. Also noteworthy is the Digital Markets Act (DMA) of the European Union, dated November 1, 2022, which is oriented toward the so-called “gatekeepers,” intermediaries with significant economic and social impact (Decarolis and Li, 2023). European audiovisual communication regulations in Spain are shown in Figure 1.

This stage encompasses regulations issued and adopted by conservative governments of the Popular Party (2011–2018), and the socialist party of Pedro Sánchez (2018–present). We found that one of the greatest challenges facing communication regulation in Spain lies in the content disseminated through social networks and, in general, the regulation of technological platforms, which tend to hyper-concentrate access to users (Barredo Ibáñez, 2021). Although legal reforms have been approved, such as the Organic Law 4/2015, of March 30, on the protection of citizen security, criticized for the absence of an organism or procedure that supervises the police during its application (Amnesty International, 2024); the Criminal Procedure Law of 2023, which establishes criminal procedures in Spain (Calderón, 2023); or that of Article 578 of the Penal Code—which focuses on protecting the potential exaltation or humiliation of victims of terrorism, or public disorder—, its application has been controversial (Cancio Meliá, 2022).

Perhaps the Spanish regulator will find in this new stage a response from the EU to these challenges, given that the supranational body is going to have more influence over national policies due to its strategy of establishing cohesive policies to face the multiple transformations of the sector. In this sense, it is to be expected to what extent the European Media Freedom Act of April 11th of this year, 2024, whose entry into force begins on May 7 of this year, will affect the existing Spanish regulations. All member states will fully apply this regulation as of August 8, 2025. Within the digital strategy and technological disruption, Spain will have to adapt European provisions and establish regulations or promote self-regulations in line with the capacity and development of the sector in Spain. The challenges posed are related to the DMA, DSA, Artificial Intelligence (AI), data usage, and the forthcoming European Media Freedom Act. The current DMA: will ensure a level playing field for all digital companies, regardless of their size and will establish clear rules for large platforms. The DSA came into force on November 16, 2022, and is applicable throughout the EU from February 17, 2024. It will give people more control over what they see online: users will have better information about why specific content is recommended to them and will be able to choose an option that does not include profiling. Advertising targeting minors will be prohibited, and the use of sensitive data, such as sexual orientation, religion, or ethnic origin, will not be allowed.

The European Media Freedom Act, once in force, will represent a substantial advance, as for the first time in EU history, pluralism will be regulated. It is the culmination of a journey throughout the last decade in which the European Union has progressively advanced through initiatives, which have gone from the field of recommendation to an increasingly prescriptive framework and finally binding to limit the effect of disinformation and enhance the role of quality journalism, a necessary pillar of any rule of law and a necessary bulwark in a context where information disorders are increasingly present.

The new policies are aimed at helping to protect users from harmful and illegal content and improve the removal of illegal content. They will also help address harmful content such as political or health-related misinformation and introduce better rules for protecting freedom of expression.

Artificial Intelligence is destined to have a significant influence in the field of communication. The EU’s anticipation in issuing regulations has left an important mark in Spain where the Spanish System of Science, Technology, and Innovation (SECTI) coordinates research policies in AI. In response to this advance, a plan for the digitization of the public sector for the period 2021–2025 has been established. In addition, a Charter of Digital Rights and a new legislative framework have been established (Van Roy et al., 2021).

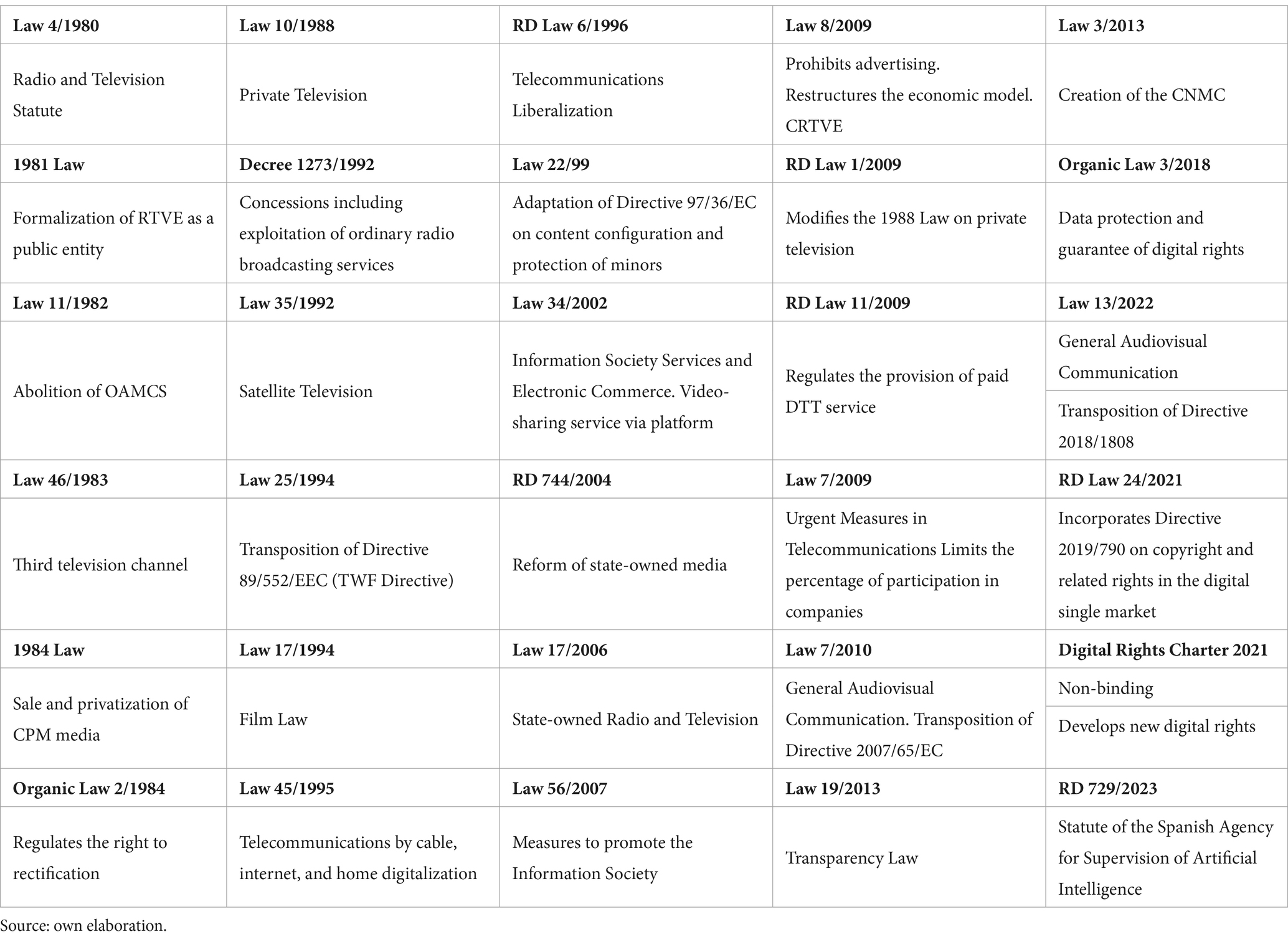

The National AI Strategy (ENIA), aims to articulate the action of different administrations and create a reference framework for the public and private sectors. This strategy is one of the fundamental elements of the Digital Spain Agenda 2025. Within the national strategy, it is foreseen that the media will be one of the sectors to experience the greatest impact due to the development of AI [National AI Strategy (ENIA), 2020] (Table 1).

Table 1. Summary of communication policies in Spain: in blue, the regulations emanating from European Directives.

Regulating communication in the 21st century is a complex issue, given the influence of aspects both internal and external to journalistic cultures (Mastrini and Loreti, 2009; Hanusch and Hanitzsch, 2019), such as contemporary problems associated with democracy as a political system (Eichengreen, 2018; Galston, 2018), or the changes linked to the abrupt digital transformation of the media ecosystem (Barredo Ibáñez, 2021). In the Spanish case, the regulation of the media is determined by the characteristics of the polarized pluralist model (Hallin and Mancini, 2004), the media’s parallelism with political parties (Baumgartner and Chaqués Bonafont, 2015), the reconfiguration suggested from the transition from dictatorship to democracy, and the normative evolution suggested since joining the European Union in 1986.

The Transition led to the partial dismantling of the Francoist communication laws, with the gradual replacement of a model based on media control—typical of authoritarianism—by one that encourages greater self-regulation. Thus, although some laws from the Franco era remain unchanged—such as the Press Law of 1966, partially in force—there has been a normative and cultural evolution (Barredo Ibáñez, 2013), with the approval of new normative bodies that overcome the pact of oblivion (Brunner, 2009), or the journalistic taboo of the monarchy (Zugasti, 2007), establishing a legal framework of guarantees for journalists and communicators.

Although we have seen how, since joining the EU, there has been a growing European influence on the Spanish regulatory framework, we have also witnessed a continuous political appropriation of communication regulations. Let us consider two examples of the above: the first, that of RD-Law 1/2009 on urgent measures in telecommunications, which far from promoting deregulation of communication, ended up encouraging greater media ownership concentration (García Leiva, 2015); the second is that of Organic Law 4/2015, of March 30, which was approved granting excessive prominence to the police forces, against journalists, something that has been criticized by organizations such as Amnesty International (2024).

As we have observed, the new ways of communicating present numerous challenges for the formulation of communication policies, highlighting the complexity of harmonizing the interests of global-scale actors and the national interests of each country. The actors operating on a global level are large companies providing services, content, platforms, search engines, applications, and telecommunications operators. Added to this are local companies and intermediaries, users/consumers who are also creators, broadcasters, and redistributors of content. This entire conglomerate complicates the task of establishing regulations.

However, the EU, as a supranational body, has been approving some regulations that, like the DSA or the DMA, are difficult to implement due to resistance among the EU States and those generated by interest groups, lobbies, and large global companies. It will be complex to align approaches of fundamental rights protection with business freedom or competition, and it is still uncertain to what extent all this will influence national policies.

The increasing participation of various actors complicates the task of establishing cross-cutting regulations. With the inclusion of technology, policy formulation will have to incorporate an ethical and human rights perspective that protects citizens’ rights. In addition, it will have to consider mechanisms to prevent excessive intrusion by public and private powers when there is a lack of policies. Both the regulations proposed by the EU and the policies outlined from Spain are influenced by economic aspects and protection of rights.

The interesting feature of European regulations lies in the harmonization of common principles and the integration of the human rights perspective in the regulation of emerging technologies. Proposals for new communication policies must consider the complexity of factors, strengthen free and independent communication systems, and find a balance between protection, flexibility, and non-intervention.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

RS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DB: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. NC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This article has been co-funded by the research project “App-Andalus,” with reference number EMC21_00240, funded by the General Secretariat for Research and Innovation of the Andalusian Regional Government, through the Emergia Program.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Aguilar, P., and Sánchez-Cuenca, I. (2009). Terrorist violence and popular mobilization: he case of the Spanish transition to democracy. Polit. Soc. 37, 428–453. doi: 10.1177/003232920933892

Amnesty International (2024). Freedom of expression in Spain. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/5chfsfz5

Arnau, L., and Sala, J. (2020). The review of scientific literature: guidelines, procedures, and quality criteria. Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. Available at: https://www.mdx.cat/handle/10503/69666

Barredo Ibáñez, D. (2013). The Royal Taboo: The Image of a Monarchy in Crisis. Córdoba, Spain: Berenice.

Barredo Ibáñez, D. (2021). Digital Media, Participation, and Public Opinion. Bogotá D. C.: Tirant Lo Blanch.

Baumgartner, F., and Chaqués Bonafont, L. (2015). All news is bad news: newspaper coverage of political parties in Spain. Polit. Commun. 32, 268–291. doi: 10.1080/10584609.2014.919974

Brunner, J. (2009). Ironies of Spanish history: observations on the post-Franco politics of forgetting and memory. Hist. Contemp. 38, 163–183.

Bustamante, E. (2014). “The democratization of the Spanish cultural and media system. Facing a national emergency situation” in Proximity Media: Social Participation and Public Policies. ed. M. Chaparro Escudero (Girona/Málaga, Spain: Luces de Gálibo), 21–34.

Calderón, G. O. (2023). Conformity in the Spanish criminal process: analysis and critical judgment. Derecho PUCP 90, 389–411. doi: 10.18800/derechopucp.202301.011

Cancio Meliá, M. (2022). Terrorist discourse, hate speech, and the crime of glorification/humiliation (art. 578 of the penal code): risk or imposition of a specific view of the past? Rev. Electrón. Direct. Penal Polít. Crim. 10, 173–194.

Codina, LL (2018). Systematic reviews for academic papers 1: concepts, phases, and bibliography. Blog Lluís Codina. Available at: https://www.lluiscodina.com/revisiones-sistematizadas-fundamentos

Decarolis, F., and Li, M. (2023). Regulating online search in the EU: from the android case to the digital markets act and digital services act. Int. J. Ind. Organ. 90:102983. doi: 10.1016/j.ijindorg.2023.102983

Eichengreen, B. (2018). The Populist Temptation: Economic Grievance and Political Reaction in the Modern Era. United States of America: Oxford University Press.

Fernández, M. J., and Cea, N. (2023). “European union legislation on disinformation: progress and challenges” in Communication in the Digital Era. eds. F. J. Martínez and A. Miguel (Valencia, Spain: Tirant lo Blanch), 61–76.

Galston, W. (2018). Anti-Pluralism: The Populist Threat to Liberal Democracy. New Haven, London: Yale University Press.

García Leiva, M. T. (2015). Spain and the convention on cultural diversity: consequences of its ratification for communication and cultural policies. Trípodos 36, 167–183.

Hallin, D. C., and Mancini, P. (2004). Comparative Media Systems: Three Models of the Relationship Between Media and Politics. United States of America: Hacer editorial.

Hanitzsch, T. (2007). Deconstructing journalism culture: toward a universal theory. Mass Commun. Theory 17, 367–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2885.2007.00303.x

Hanusch, F., and Hanitzsch, T. (2019). “Modeling journalistic cultures: a global approach” in Worlds of Journalism: Journalistic Cultures Around the Globe. eds. T. Hanitzsch, F. Hanusch, J. Ramaprasad, and A. de Beer (New York Chichester, West Sussex: Columbia University Press), 283–308.

Hernández Prieto, M. (2015). Public Communication Policies: A Comparative Study of Audiovisual Legislation in Argentina and Spain. Doctoral thesis. Universidad de Salamanca.

Martín-Barbero, J. (2015). From where do we think about communication today? Rev. Latin. Comun. 128, 13–29.

Marzal, F. J., and Casero-Ripollés, A. (2009b). The policies of communication before the implementation of TDT in Spain. Critical Balance Sheet and Outstanding Challenges. Sphera Públ. 9, 95–113.

Marzal, F. J., and Casero-Ripollés, A. (2009a). Communication Policies in the Implementation of DTT (Digital Terrestrial Television) in Spain: Critical Assessment and Pending Challenges. Sphera Publ. 9, 95–113.

Mastrini, G., and Loreti, D. (2009). “Communication policies: a deficit of democracy” in Mediated Communication: Hegemonies, Alternatives, Sovereignties. ed. S. Sel (Buenos Aires: CLACSO), 59–70.

Moragas Spà, M. D. (2009). From communication to culture: new challenges for communication policies Telos. Cuadernos Comun. Tecnol. Soc. 81, 12–18.

Moya-López, D. (2023). Banking and media in the Spanish transition and democratic consolidation (1975-1989). Investig. Hist. Econ. 19, 56–67. doi: 10.33231/j.ihe.2023.04.002

Murciano, M. (1996). European communication policies: analysis of developing experience. Comun. Soc. 28, 9–32.

National AI Strategy (ENIA). (2020). Estrategia Nacional de Inteligencia Artificial. Gobierno de España. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/2jtm93ud

Pérez, J. B. (1979). Communication policy in Spain during Franco's regime. Rev. Estud. Polít. 11, 157–170.

Ruiz-Huerta, A. (2009). The blind spots: A critical perspective of the Spanish transition, 1976–1979. Biblioteca Nueva.

Sánchez-García, P., Redondo, M., and Diez, A. (2021). Journalism teaching at the Franquist official school (1941-1975) analyzed by its former students. Ámbitos 54, 38–56. doi: 10.12795/Ambitos.2021.i54.02

Sancho, R. (1990). Bibliometric indicators used in the evaluation of science and technology: a literature review. Rev. Españ. Document. Científ. 13, 842–106. doi: 10.3989/redc.1990.v13.i3.842

Van Roy, V., Rossetti, F, Perset, K, and Galindo-Romero, L (2021). AI watch-national strategies on artificial intelligence: A European perspective. No. JRC122684. Joint Research Centre (Seville site).

Xiao, Y., and Watson, M. (2019). Guidance on conducting a systematic literature review. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 39, 93–112. doi: 10.1177/0739456X17723971

Zallo, R. (2010). The audiovisual communication policy of the socialist government (2004-2009): a neoliberal turn. Rev. Lat. Comun. Soc. 65, 014–029. doi: 10.4185/RLCS-2010-880-014-029

Keywords: normative framework, Spanish media, media regulation, pluralist polarized model, Spain

Citation: Seijas Costa R, Barredo Ibáñez D and Cea Esteruelas N (2024) Evolutionary regulatory dynamics in a pluralist and polarized journalism landscape: a case study of the normative framework in Spanish media. Front. Commun. 9:1424096. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2024.1424096

Received: 27 April 2024; Accepted: 21 May 2024;

Published: 10 June 2024.

Edited by:

José Sixto-García, University of Santiago de Compostela, SpainReviewed by:

Roberto Gelado Marcos, CEU San Pablo University, SpainCopyright © 2024 Seijas Costa, Barredo Ibáñez and Cea Esteruelas. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Raquel Seijas Costa, c2VpamFzQHVtYS5lcw==; Daniel Barredo Ibáñez, ZGFuaWVsLmJhcnJlZG9AdW1hLmVz; Nereida Cea Esteruelas, bmVyZWlkYWNlYUB1bWEuZXM=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.