- Department of Linguistics and Oriental Studies, Complutense University of Madrid, Madrid, Spain

This paper is an investigation of reference production in 84 Italian-Spanish bilingual children aged 8 to 12. The study explores whether such reference production is influenced by either the type of referential expression involved or language dominance by analyzing how these children manage reference. The children’s relative proficiency in the two languages (and thus their language dominance) was assessed through a cloze-test, and their narrative production was evaluated using a retelling task. Results indicated a preference for null pronouns to refer to subjects and full referential expressions for objects, with Italian showing a higher occurrence of full referential expressions. Dominance in either language did not significantly impact reference production. This suggests that bilingual children can distinguish between language-specific patterns, a behavior consistent with adult monolingual groups. These results contribute to our understanding of bilingual reference management and shed light on the role played by language and language dominance.

1 Introduction

Reference management and anaphora resolution in both the monolingual and multilingual contexts have been the subject of scholarly inquiry for many years. It has generally been assumed that languages that allow null subjects, that is, null-subject languages (NSLs) behave similarly regarding the interpretation of pronouns: null subject pronouns refer to subject antecedents, while overt subject pronouns refer to object antecedents and indicate a topic shift. This assumption has been confirmed in many studies where a similar pattern was found In various NSLs (Carminati, 2002 for Italian; Alonso-Ovalle et al., 2002 for Spanish; Papadopoulou et al., 2015 for Greek). However, other studies have yielded contrary results. For example, Filiaci (2011) detected differences in this regard between Italian and Spanish: following Carminati (2002), she confirmed through self-paced tasks that in Italian there is a strict division of labor between null and overt subject pronouns that is not as strong in Spanish, particularly with overt pronouns in subject position. Similarly, Leonetti and Torregrossa (in press) compared the interpretation of null and overt subject pronouns in Italian, Greek, and Spanish by means of an interpretation task. Here as well, Italian appeared to be the most syntactically “restrictive” of the three, as it showed a clear preference to associate null pronouns with subject antecedents and overt pronouns with object antecedents and rejected the contrary association (Rizzi, 1982). Greek showed a similar pattern but was less restrictive in accepting the less expected combinations. Regarding the findings for Spanish, it showed no preference whatsoever between null and overt pronouns in subject position referring back to subject and object antecedents, as in sentence (1), where it remains unclear who is performing the action in the subordinate clause–closing the folder– with both the null and the overt pronoun.

(1) El doctor pagó al arquitecto mientras (pro)/él cerraba la cartera.

‘The doctor paid the architect while (pro)/he was closing the folder.’

With regard to the bilingual context, a vast amount of literature has been produced in recent years focusing on the role played by factors such as cross-linguistic effects, language dominance, input or age of first exposure in early bilinguals, successive bilinguals and second language (L2) learners [see Meisel (2009) and Tsimpli (2014) for details]. Regarding child bilingualism, many elements of language have been analyzed, among them anaphora resolution in both NSLs and non-NSLs (Sorace, 2011; Torregrossa et al., 2020). Experiments on bilingual anaphora resolution have yielded very different results, prompting various explanations. For instance, studies involving English-speakers who were nearly native-speakers of Italian (Sorace and Filiaci, 2006; Belletti et al., 2007) found that while these individuals had the null subject grammar, they did not seem to have the necessary processing resources to felicitously apply it, resulting in an overproduction of overt pronouns compared to their monolingual peers.

Similar results have been found with bilinguals, as seen in Bel and García-Alcaraz (2016) for speakers of Moroccan Arabic and Spanish. Likewise, Sorace and Serratrice (2009) found an over-acceptance of overt subject pronouns in no-topic shift contexts in Italian–Spanish bilingual children. An equivalent outcome, but with an overproduction of full determiner phrases–DPs–, has also been found in Greek–Italian (Andreou et al., 2023) and Greek–Spanish (Giannakou and Sitaridou, 2022) bilinguals. Other studies (Torregrossa et al., 2020 for Greek–German; Torregrossa et al., 2021 for Greek–Albanian/English/German) have found both underspecification and overspecification in bilinguals, postulated as reflecting the impact of proficiency and language experience. On the other hand, native-like behavior has also been found in both bilinguals (Kraš, 2008 for Croatian–Italian; Di Domenico and Baroncini, 2019 for Greek–Italian; Giannakou, 2023 for Greek–Spanish) and L2 learners (Kraš, 2015 for Croatian–Italian). As we see, the bibliography is extensive and the possible reasons for these varied outcomes are many.

The general issue that arises with all these experiments is that differences among the methodologies applied and/or the linguistic backgrounds of participants have made it difficult to compare results. For this reason, the present study’s contribution is to add the pair Spanish–Italian to an ongoing investigation of bilingual narratives1 in different linguistic pairs, all applying an identical methodology, for which Torregrossa et al. (2020) work with German–Greek bilinguals is the starting point. It is intended that the resulting expanded compilation of findings will be compared and analyzed in the near future, providing an organized and systematized answer regarding bilingual narratives.

Following this approach, the main questions in this study are (1) whether bilinguals associate null and overt pronouns with specific antecedents following each language’s pattern (RQ1) and (2) whether language dominance play any role in their decisions (RQ2).

2 Methods

The study was conducted during the 2021–2022 academic year at an Italian school in Madrid, the Scuola Statale Italiana di Madrid, which uses Italian as the main medium of instruction but offers some subjects in Spanish.

2.1 Participants

Eighty-four bilingual children (41 female) ranging in age from 8 to 12 took part in the study.

Prior to the experiment, a short questionnaire was sent to the participants’ parents regarding the linguistic background of their children in terms of the language(s) spoken at home, during extracurricular activities, with parents and grandparents, etc.2. In terms of nationality, in some cases parents were both Spanish or both Italian while in others one parent was Spanish and the other Italian. Nevertheless, 67% of parents reported the family context to be more Spanish-dominant, although 80% of the families had exposed their children to Italian in some way since the age of 3. Following Montrul (2008), participants can therefore be described as either simultaneous or early successive bilinguals. According to the traditional characterization of micro- and macro-parameters, the Null Subject Parameter is considered a macro-parameter (Roberts, 2007). Following Clark (2009), children learn macro-parameters by the age of 6, which means that when monolingual natives enter school, they have already mastered the basic syntax of the Null Subject Parameter. On the other hand, according to Tsimpli (2014) and Paradis et al. (2011), simultaneous and early successive bilinguals have no learning constraints compared to their monolingual peers, if the input has been similar and sufficient in both languages. If bilingual children raised with two NSLs are perfectly able to acquire the Null Subject Parameter of both languages, and we know that children in the present experiment have had a balanced input for Spanish and Italian since age 3 or before, this would allow them to separate the syntactic particularities of anaphora, according to the aforementioned literature.

2.2 Materials and procedure

Participating pupils performed two experimental tasks, a cloze-test and a narrative retelling task for each language. Tasks in the respective languages were administered on paper during the children’s regular Italian and Spanish classes. The order in which the two language versions were administered was randomized across groups, as was the order of tasks. Administration of one language version of the task set was separated by a gap of at least 1 week from administration of the other language version.

The cloze-test was intended to assess the children’s proficiency in each language (see Hulstijn, 2010 for an overview of instruments of this sort), replicating the task used in Torregrossa et al. (2023) for Portuguese,3 which in turn is based on a textless cartoon story that forms part of the Edmonton Narrative Norms Instrument (ENNI; Story B3 – Balloon; Schneider et al., 2006)4. The story is written in such a way that it targets structures related to the syntax-discourse interface (e.g., pronouns, clitics, adverbial clauses). This makes it possible to assess the children’s mastery of these structures, as well as their comprehension abilities (Torregrossa et al., 2023: 16). Excerpts from the Italian and Spanish versions of the test can be seen in (2).

(2) a. Il coniglio ve_ _ che la sua amica sta tirando un carretto con un belli_ _ _ _ _ palloncino. Il palloncino, il coniglio _ _ vuole prendere, per gio_ _ _ _ con la sua amica, ma la cagnolina g_ _ dice che prima devono slegarlo. (Italian)

b. El conejito ve que su amiga está tirando de un carrito con un globo muy bo_ _ _ _. El conejito quiere coger_ _, para ju_ _ _ con su amiga, pero la perrita _ _ dice que antes tienen que desatarlo. (Spanish).

The rabbit sees his friend pulling a wagon with a beautiful balloon tied to it. The little rabbit wants to take the balloon to play with his friend, but the little dog says that they need to untie it first.

Participants’ word completions were then coded as ‘correct’, ‘incorrect’, ‘missing’ or ‘unexpected’ (meaning that the word completion was not the intended target but was nonetheless grammatically acceptable). For purposes of analysis, all ‘correct’ and ‘unexpected’ answers were assigned a value of 1, while all ‘incorrect’ and ‘missing’ answers were assigned a value of 0. Points were totalled for each language, resulting in a proficiency score out of forty.

These scores also made it possible to check for language dominance by subtracting one language proficiency score from the other, in this case the score for Spanish being subtracted from the score for Italian. Thus a positive score indicated dominance in Italian, while a negative score indicated dominance in Spanish. The closer the score is to zero, the more balanced the child’s knowledge of both languages (Torregrossa and Bongartz, 2018). This dominance score will be used in the analysis of the narrative task.

Participants’ ability to produce referential expressions in Spanish and Italian was tested using a story-telling task, again replicating the experiment carried out in Torregrossa et al. (2020). Narratives were elicited by asking the children to retell another ENNI story in both languages (Story A3 – Airplane; Schneider et al., 2006). The story consists of 13 pictures with no text, representing a series of events involving two characters, Elephant Girl and Giraffe Boy.

Following the procedure in Torregrossa et al. (2020), we primed the participants by first having them hear a narrator tell the story depicted in the cartoon drawing before they had to retell it, on the grounds that this would render the decoding of the pictures and the comprehension of the story easier for them (Gagarina, 2016). The task was administered as a sequence of Power Point slides on the classroom screen. The story pictures appeared two by two, accompanied by the voice of the narrator telling the story (the Spanish audio was created based on the Italian version, already available from Torregrossa et al., 2020). After they had viewed and heard the full story, the children were asked to rewrite it in their own words.5

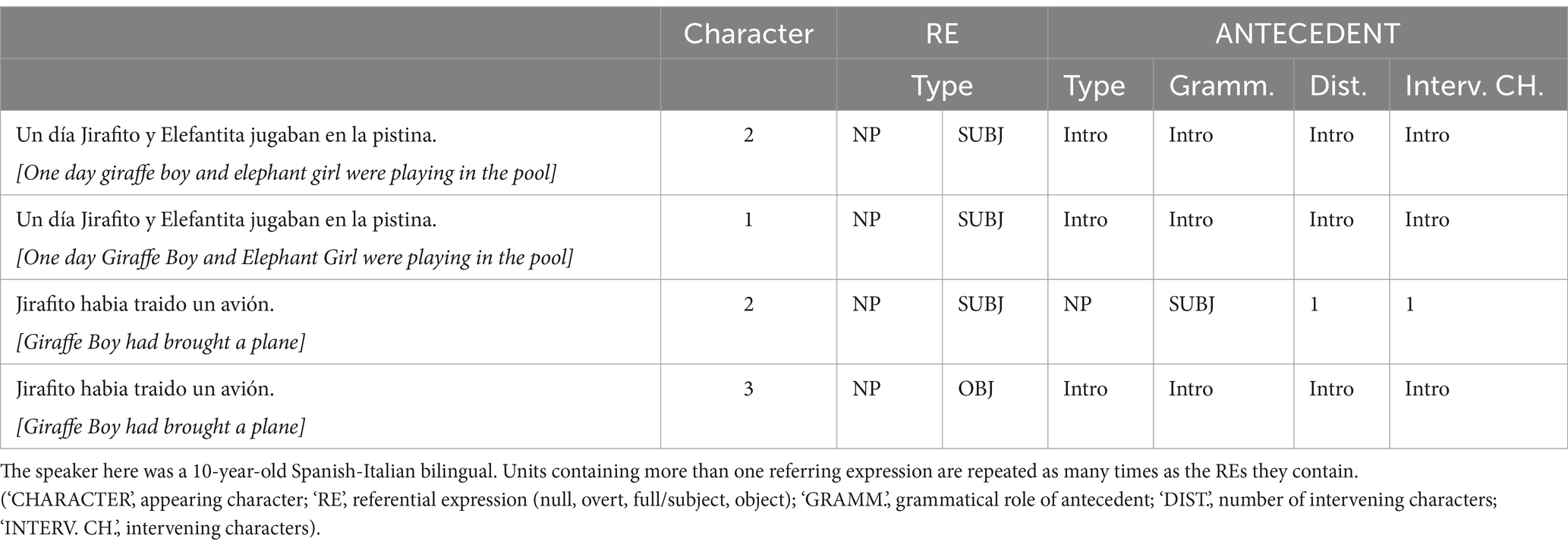

All resulting child-produced texts were subsequently transcribed as digital text and then divided into clauses, based around the occurrence of any verb in the text. In the analysis process, each clause was entered in a table with an additional column indicating any referential expression (RE) contained in that clause. If the clause contained more than one RE, it received an additional column entry. Further columns indicated each of the possible characters with an assigned number, the type of RE (e.g., full, null, overt), its grammatical role (e.g., subject, object, etc.) and the number of characters intervening between the antecedent and the RE (except for the first appearance, labeled as “intro”). A sample of coding can be seen in Table 1. After coding all narratives, only distances of none or one intervening character between the RE and its antecedent were considered, as here immediate pronominal resumption was the main focus.

3 Results

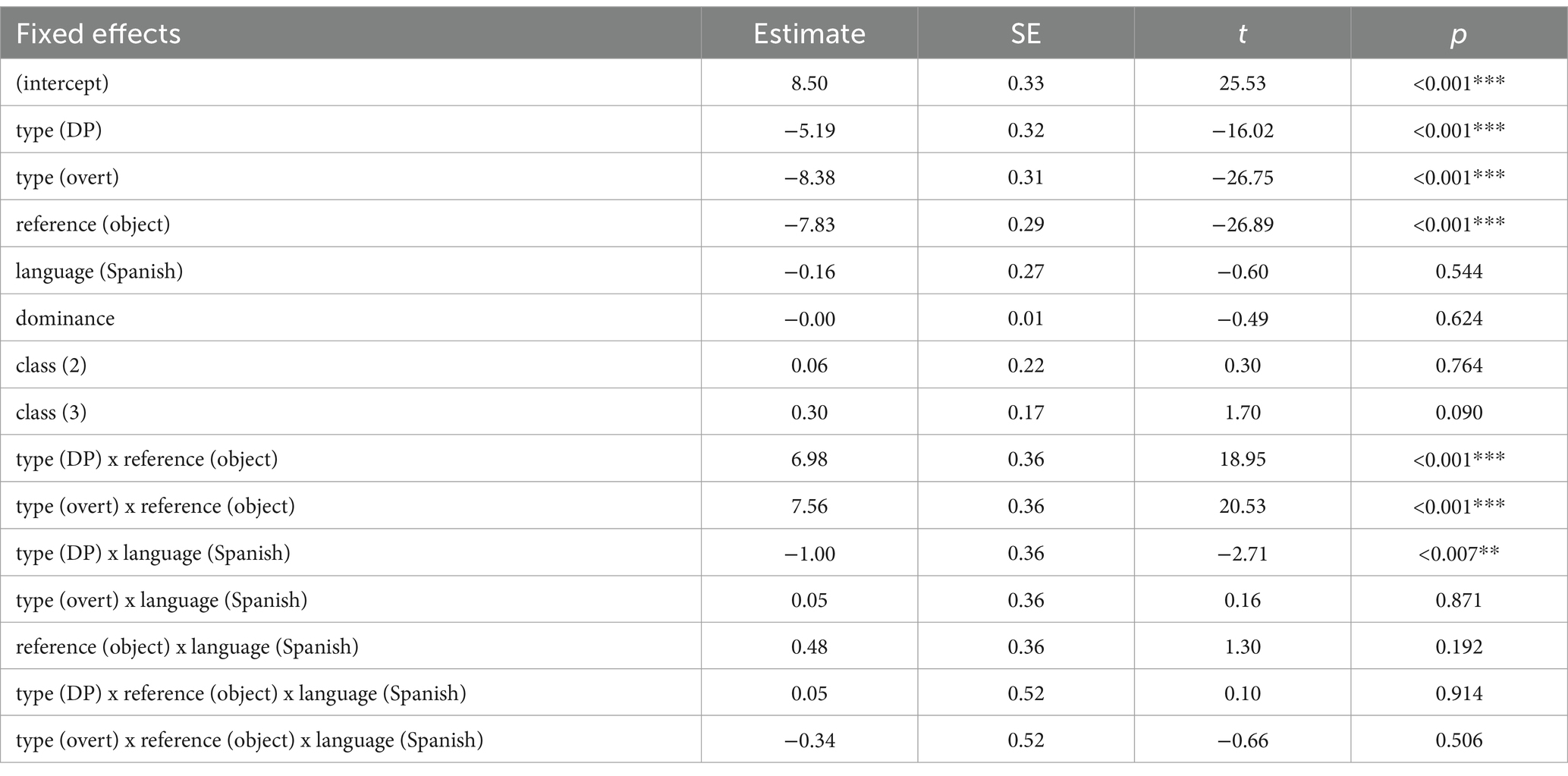

Looking at the results for the full sample of 84 participants, the cloze-test revealed a balanced participant population with similar proficiency levels in Spanish and Italian. As shown in Figure 1, groups were separated by age, displaying proficiency levels in both languages. In fact, the mean language dominance score was −0.5, pointing to a slight (but not statistically significant) Spanish dominance. To calculate language dominance scores, the results of the cloze-test in Spanish were subtracted to the results of the cloze-test in Italian for each child; a negative number corresponded to a Spanish dominance, while a positive result indicated an Italian dominance.

Figure 1. Language dominance scores calculated by subtracting cloze-test task results (/40) for Spanish from corresponding results for Italian.

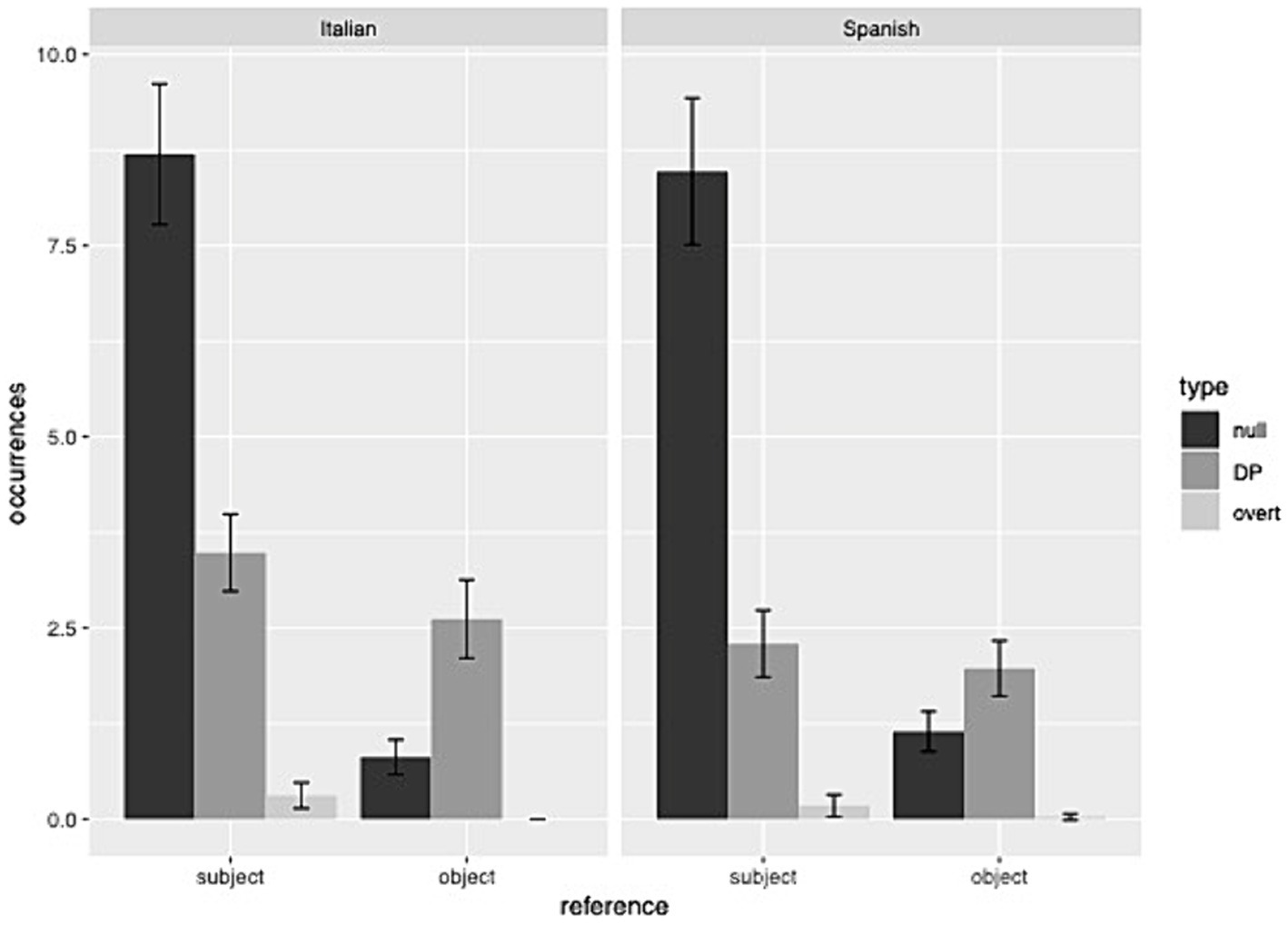

Moving on to the narrative retelling task, Figure 2 represents the overall occurrences of null and overt pronouns and full referential expressions as referring to either a subject or an object antecedent. As can be seen, null pronouns are the preferred form used to refer to the subject in both languages.

Figure 2. Overall occurrences of null and overt pronouns and full referential expressions as referring to either a subject or an object antecedent.

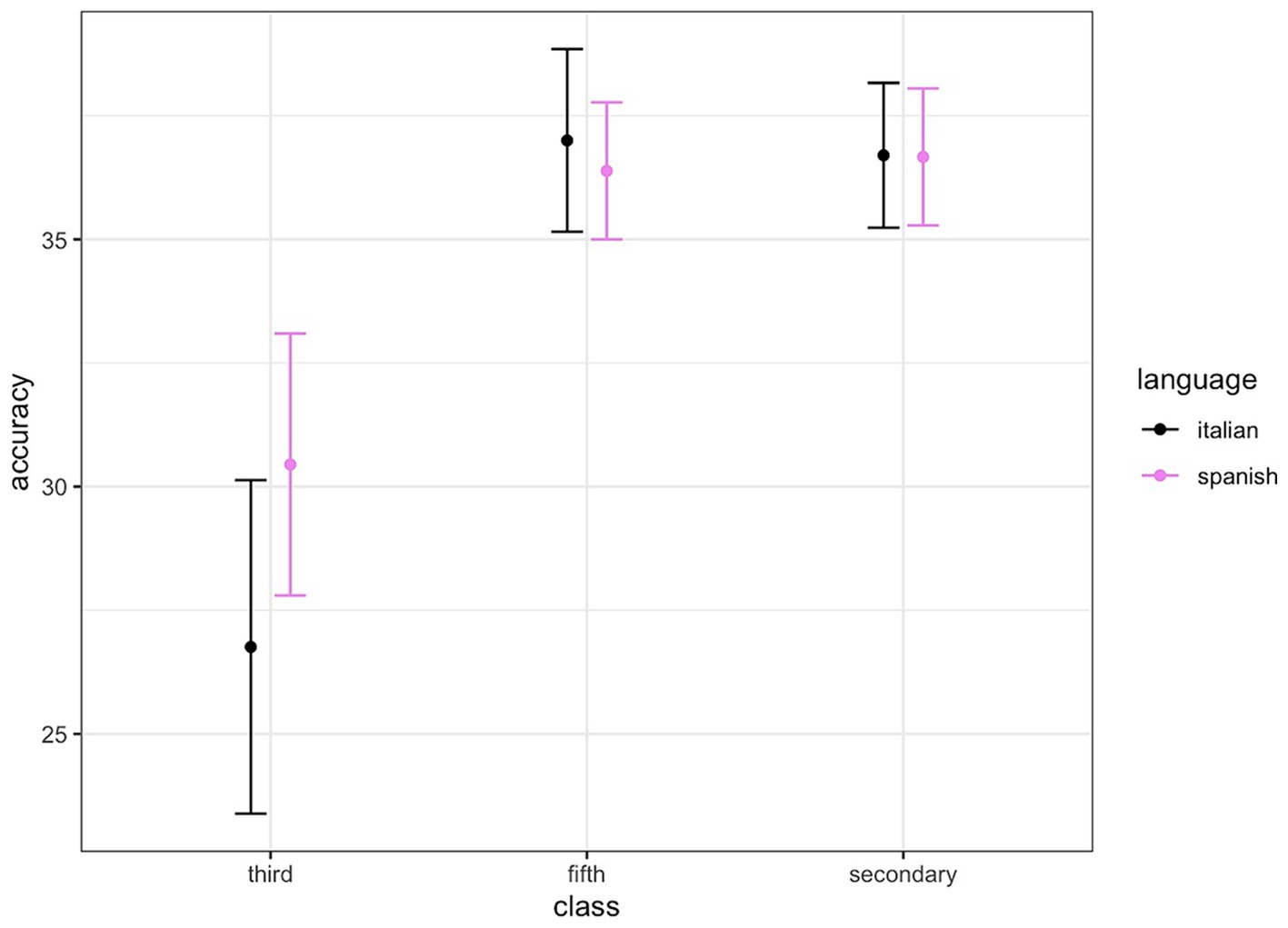

For the statistical analysis, a linear mixed-effects model was applied using R software. The model, created for the response variable frequency (representing the frequency of specific REs produced by each child in relation to a specific antecedent), includes a random intercept and slopes for each participant and was fitted as a function of the dependent variable type (indicating the type of RE) in a second-order interaction with reference (distinguishing between reference to a subject antecedent vs. reference to an object antecedent) and language (Italian vs. Spanish). Additionally, the variables group (i.e., mean age) and dominance were also included as main effects. The model also included subject intercept and slope random effects (Table 2).

The model showed a main effect in Italian for the type of RE when referring to subjects, with significantly fewer occurrences of DPs (β = −5.19, SE = 0.32, t = −16.02, p = <0.001) and overt pronouns (β = −8.38, SE = 0.31, t = −26.75, p = <0.001) as compared to null pronouns. This effect was no different for Spanish for overt pronouns, as seen in the non-significant main effect of language or in the interaction of this variable with the variable type (overt), although this was not the case for DPs, which were less frequently resorted to in Spanish as compared to Italian (β = −1.00, SE = 0.36, t = −2.71, p = 0.007).

Additionally, a main effect was also observed in Italian for the variable reference on the number of occurrences of null pronouns, which participants used fewer times when referring to objects than when referring to subjects (β = −7.83, SE = 0.29, t = −24.21, p = < 0.001). The interaction of reference with the type of anaphoric expression shows a different pattern in the use of DPs, which were more often used when referring to objects than null pronouns (β = 6.98, SE = 0.36, t = 18.95, p = < 0.001), differently from the trend observed when referring to subjects. Also, a significant interaction was observed for overt pronouns, showing a much smaller difference between null and overt pronouns, even though these were resorted to on very few occasions in reference to objects (β = 7.56, SE = 0.36, t = 20.53, p = < 0.001). The same applies to Spanish, as shown by the non-significant differences in the corresponding interactions. Finally, the model showed no effect for the variables of language dominance or age group.

4 Discussion and conclusion

The aim of this study was to test reference production in Spanish–Italian bilingual children by means of a narrative retelling task. Following the ENNI materials used in Torregrossa et al. (2020), this task prompted participating children to retell a story using their own words. The main focus was to see, on one hand, whether they would associate null and overt pronouns with specific antecedents following different patterns for Spanish and Italian (RQ1), as found in monolinguals in Filiaci (2011) and Leonetti and Torregrossa (in press), and on the other, whether language or language dominance would play any role in their decisions (RQ2).

The statistically significant differences in the occurrence of anaphoric expressions reveal a clear relationship between them and reference assignment (RQ1), with an interaction between null pronouns and the subject antecedent, and between full RE and the object antecedent in both languages. However, in Italian there is a higher occurrence of full REs, with both subject and object antecedents. As for overt pronouns, they are scarce in number but clearly associated with subject antecedents. This is similar to the results found in Lozano (2009) for English speakers of Spanish as an L1, where both native-speakers and L2-learners displayed a clear preference for full DPs in topic-shift contexts and used a small number of overt pronouns, as well as the findings reported in Giannakou and Sitaridou (2022) for Greek–Italian bilinguals, who used overt pronouns only rarely.

Excerpts (3) and (4) below are taken from the transcribed productions of 12-year-old participants in the present study as they begin the narrative retelling task.6 In the Italian sentence in (3) there are more occurrences of full REs (Elefantina, Giraffino, aeroplanino), while in the Spanish sentence in (4) there are more null and clitic pronouns.

(3) Elefantina e Giraffino decidono di andare alla piscina. Giraffino gli fa vedere ad Elefantina il suo aeroplanino. Elefantina si innamora del aeroplanino di Giraffino. Elefantina gli rubba l’aeroplanno a Giraffino.

Elephant Girl and Giraffe Boy decide to go to the pool. Giraffe Boy shows ElephaGirl his toy airplane. Elephant Girl falls in love with Giraffe Boy’s airplane. Elephant Girl steals the airplane from Giraffe Boy.

(4) Un día Jirafito estaba jugando con un avioncito, y cuando Elefantita lo vio le dio envidia asi que se lo quito y casualmente se le cayo al agua y el Jirafito enfadado le chilla.

One day Giraffe Boy was playing with a toy airplane, and when Elephant Girl saw it, she got envious so she took it from him and it fell in the water, and Giraffe Boy was angry and yelled at her.

Regarding whether language or language dominance are relevant factors for reference assignment (RQ2), the statistical analysis showed no significant results for these two factors. This indicates that the referential choices made by the children were not influenced by one language or another, or by the child’s being more dominant in Spanish or Italian. This result is not surprising considering the scores obtained in the cloze-test: while we would expect dominance in one of the two languages to translate into cross-linguistic effects [as in Sorace and Filiaci (2006)], the fact that differences between Spanish and Italian are maintained means that children can separate each referential choice in the two languages.

These results are consistent with some of those found in previous research. For example, Bel and García-Alcaraz (2016) observed that Moroccan Arabic–Spanish bilinguals performed very much native-like, in accordance with the Position of Antecedent Strategy (Carminati, 2002) in terms of associating null pronouns with subject antecedents and exhibiting no residual optionality, in other words, not overproducting overt pronouns in contexts where the preferred RE would be a null subject. Similarly, Di Domenico and Baroncini (2019) compared L2 and bilingual Greek and Italian speakers to monolinguals and found that the bilinguals behaved like the monolinguals; an effect of age, however, was found inside this bilingual group. Finally, Giannakou (2023) compared bilingual, heritage and L2 speakers of Greek and Spanish with monolinguals and found that the bilinguals performed like the monolinguals in linking null pronouns to subject antecedents and overt pronouns to object antecedent in Greek. Heritage speakers were closer to Spanish monolinguals because they produced more ambiguous null pronouns. As Giannakou (2023) points out, what arises from her study is that the interpretation of overt pronouns in Greek is more grammatically determined and restricted to more specific contexts, while in Spanish overt pronouns rely more on pragmatics and therefore can be used more flexibly.

The narrative task proposed in the present paper reveals that Italian–Spanish bilingual children, just like adults, show a clear preference to associate certain REs with specific antecedents. Nevertheless, this preference is not as strong as those found in previous adult monolingual studies, such as Leonetti and Torregrossa (in press), where Italian-speakers exhibited a sharp dichotomy between null pronouns associated to subject antecedents and overt material associated to object antecedents, while Spanish-speakers showed no preferences whatsoever. In the present study, a general tendency to associate null pronouns with subject antecedents and full REs with object antecedents seems to arise. However, when speaking Italian, participants more clearly associate each type of RE with a specific antecedent and produce a higher number of full REs overall. This could be an indicator of these bilingual children’s sensitivity to language-specific patterns.

As mentioned, a surprising finding is the scarce use by these children of overt pronouns in both languages, which contradicts other research on Spanish–Italian bilinguals, such as Sorace and Serratrice (2009): although the authors associate this result with cognitive processing costs, it could be a further indicator of the actually different uses and interpretations of null and overt pronouns in these two languages. It has generally been assumed that null and overt pronouns are complementary and, like a coin, are a two-sided “self-sufficient” element regarding anaphora resolution: null for subject antecedents, overt for object antecedents; null when there is topic continuity, overt when the topic changes, and so on. But what these results show seems to put overt pronouns in a different, secondary position, as full REs seem to be preferred in these contexts. In this sense, such behavior has been found also in other linguistic pairs, such as English L1/Spanish L2 or in Greek-Spanish bilinguals (Lozano, 2009; Giannakou and Sitaridou, 2022).

The purpose of this study was to collect data regarding how Italian-Spanish bilingual children manage reference in a narrative retelling task context. Because other language pairings –such as German-Greek in Torregrossa et al. (2020)– are being studied using exactly the same methodology, this will give us data in both languages that allow null pronouns and languages that do not, that is, pro-drop and non pro-drop language combinations, which will all be directly comparable. The results of these comparisons will allow a more extended and complete analysis of bilingual narratives.

Our present investigation of Italian and Spanish bilingual children reveals that they choose to associate specific referential expressions with specific antecedents, namely, null pronouns with subject antecedents and full REs with object antecedents. Nevertheless, they are beginning to mirror the behavior seen in studies of adult monolinguals (Leonetti and Torregrossa, in press; Filiaci, 2011), that is, a more pronounced separation of duties for the Italian pronominal system, and an increased number of null pronouns referring to object antecedents for Spanish. Moreover, language dominance seems to play no role in such differentiations. This separation of patterns is consistent to a certain extent with the results found in some of the literature for other languages, such as Andreou et al. (2023) for Greek–Italian bilinguals or Giannakou (2023) for Greek–Spanish bilinguals. This work therefore represents a small contribution to our understanding of reference production in bilingual contexts.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Scuola Statale Italiana di Madrid Enrico Fermi. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin.

Author contributions

VL: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Publishing funding received from AEAL - Asociación para el Estudio de la Adquisición del Lenguaje.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Margarita Borreguero Zuloaga, Jacopo Torregrossa and Miguel Jiménez Bravo for their insightful feedback throughout the course of this research, and the journal assigned peer reviewers that have helped me improve this manuscript with their invaluable comments. This research is also part of the work developed within the framework of the project EPSILtwo (PID2023-148755NB-I00). I would also like to thank Michael Kennedy-Scanlon for proofreading the paper. Any remaining errors or omissions in this work are solely my own responsibility.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^https://sfb1252.uni-koeln.de/en/projects/c03-reference-management-in-bilingual-narratives

2. ^Unfortunately, only 27 parents filled in the questionnaire, and many of those who did failed to provide the child’s date of birth. The background information for children provided here must therefore be viewed as merely suggestive.

3. ^We obtained an Italian version from the authors and translated it to Spanish with their permission.

4. ^http://www.rehabmed.ualberta.ca/spa/enni/about_the_enni.htm

5. ^In Torregrossa et al. (2018), the children retold the story orally and were audio-recorded doing so. The present experiment was carried out in a post-Covid environment in which the sanitary protocols of the school permitted us only to test the children by means of a written activity.

6. ^All the examples provided maintain the child’s original spelling.

References

Alonso-Ovalle, L., Fernández-Solera, S., and Clifton, C. (2002). Null vs. overt pronouns and the topic-focus articulation in Spanish. Ital. J. Ling. 14, 151–169.

Andreou, M., Torregrossa, J., and Bongartz, C. (2023). “The use of null subjects by Greek-Italian bilingual children: identifying cross-linguistic effects” in Individual differences in anaphora resolution: Language and cognitive effects. eds. G. Fotiadou and I. M. Tsimpli (Amsterdam: John Benjamins).

Bel, A., and García-Alcaraz, E. (2016). “Subject pronouns in the L2 Spanish of Moroccan Arabic speakers” in The Acquisition of Spanish in understudied language pairings. eds. T. Judy and S. Perpiñán (Amsterdam: John Benjamins), 201–232.

Belletti, A., Bennati, E., and Sorace, A. (2007). Theoretical and developmental issues in the syntax of subjects: evidence from near-native Italian. Nat. Lang. Ling. Theory 25, 657–689. doi: 10.1007/s11049-007-9026-9

Carminati, M.N . (2002). The processing of Italian subject pronouns. PhD dissertation, University of Massachusetts at Amherst, Amherst (Ma): GLSA Publications.

Di Domenico, E., and Baroncini, I. (2019). Age of onset and dominance in the choice of subject anaphoric devices: comparing natives and near-natives of two null-subject languages. Front. Psychol. 9:2729. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02729

Filiaci, F. (2011). Anaphoric preferences of null and overt subjects in Italian and Spanish: A cross-linguistic comparison PhD dissertation. Edinburgh: The University of Edinburgh.

Gagarina, N. (2016). Narratives of Russian–German preschool and primary school bilinguals: Rasskaz and Erzählung. Appl. Psycholinguist. 37, 91–122. doi: 10.1017/S0142716415000430

Giannakou, A. (2023). Anaphora resolution and age effects in Greek-Spanish bilingualism: evidence from first-generation immigrants, heritage speakers, and L2 speakers. Lingua 292:103573. doi: 10.1016/j.lingua.2023.103573

Giannakou, A., and Sitaridou, I. (2022). (in)felicitous use of subjects in Greek and Spanish in monolingual and contact settings. Glossa 7, 1–33. doi: 10.16995/glossa.5812

Hulstijn, J. H. (2010). “Measuring second language proficiency” in Experimental methods in language acquisition research. eds. E. Blom and S. Unsworth (Amsterdam: John Benjamins).

Kraš, T. (2008). Anaphora resolution in near-native Italian grammars: evidence from native speakers of Croatian. EUROSLA Yearb. 8, 107–134. doi: 10.1075/eurosla.8.08kra

Kraš, T. (2015). Cross-linguistic influence at the discourse-syntax interface: insights from anaphora resolution in child L2 learners of Italian. Int. J. Biling. 20, 369–385. doi: 10.1177/1367006915609239

Leonetti, V., and Torregrossa, J. (in press). The interpretation of null and overt subject pronouns in Spanish compared to Greek and Italian: The role of VSO and DOM.

Lozano, C. (2009). Selective deficits at the syntax-discourse interface: evidence from the CEDEL2 corpus. In N. Snape, Y.K. Leung, and M.S. Smith (eds.), Representational deficits in SLA. Amsterdam: John Benjamins . 127–166.

Meisel, J. M. (2009). Second language acquisition in early childhood. Z. Sprachwiss. 28, 5–34. doi: 10.1515/ZFSW.2009.002

Montrul, S. (2008). Incomplete acquisition in bilingualism: re-examining the age factor. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Papadopoulou, D., Peristeri, E., Plemenou, E., Marinis, T., and Tsimpli, I. M. (2015). Pronoun ambiguity resolution in Greek: evidence from monolingual adults and children. Lingua 155, 98–120. doi: 10.1016/j.lingua.2014.09.006

Paradis, J., Genesee, F., and Crago, M. (2011). Dual language development and disorders: A handbook on bilingualism and second language learning. Baltimore: Brookes.

Schneider, P., Hayward, D., and Vis Dubé, R. (2006). Storytelling from pictures using the Edmonton narrative norms instrument. J. Speech Lang. Pathol. Audiol. 30, 224–238.

Sorace, A. (2011). Pinning down the concept of ‘interface’ in bilingualism. Ling. Approach. Bilingual. 1, 1–33. doi: 10.1075/lab.1.1.01sor

Sorace, A., and Filiaci, F. (2006). Anaphora resolution in near-native speakers of Italian. Second. Lang. Res. 22, 339–368. doi: 10.1191/0267658306sr271oa

Sorace, A., and Serratrice, L. (2009). Internal and external interfaces in bilingual language development: beyond structural overlap. Int. J. Biling. 13, 195–210. doi: 10.1177/1367006909339810

Torregrossa, J., Andreou, M., and Bongartz, C. (2020). Variation in the use and interpretation of null subjects: a view from Greek and Italian. Glossa 5:95. doi: 10.5334/gjgl.1011

Torregrossa, J., and Bongartz, C. M. (2018). Teasing apart the effects of dominance, transfer, and processing in reference production by German–Italian bilingual adolescents. Languages 3:36. doi: 10.3390/languages3030036

Torregrossa, J., Bongartz, C., and Tsimpli, I. M. (2018). Bilingual reference production. A cognitive computational account. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism. 9, 569–599.

Torregrossa, J., Bongartz, C., and Tsimpli, I. M. (2021). “Bilingual reference production” in Psycholinguistic approaches to production and comprehension in bilingual adults and children. eds. L. Fernandez, K. Katsika, M. Iraola, and S. Allen (Amsterdam: John Benjamins).

Torregrossa, J., Flores, C., and Rinke, E. (2023). What modulates the acquisition of difficult structures in a heritage language? A study on Portuguese in contact with French. German Ital. Bilingual. 26, 179–192. doi: 10.1017/S1366728922000438

Keywords: bilingualism, anaphora, narratives, Spanish, Italian

Citation: Leonetti Escandell V (2024) Reference management in written narrative production by Spanish-Italian bilingual children. Front. Commun. 9:1400984. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2024.1400984

Edited by:

Eva Aguilar-Mediavilla, University of the Balearic Islands, SpainReviewed by:

Aretousa Giannakou, University of Nicosia, CyprusVioleta Sotirova, University of Nottingham, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2024 Leonetti Escandell. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Victoria Leonetti Escandell, dmxlb25ldHRAdWNtLmVz

Victoria Leonetti Escandell

Victoria Leonetti Escandell