- Department of Media and Business Communication, Institute Human-Computer-Media, University of Würzburg, Würzburg, Germany

Although product placements in music videos are ubiquitous and a common form of advertising cooperation between companies and artists, few studies have addressed the topic, especially the artists' perceptions. This experimental online study examines the effects of fit between artist and product in music videos. Results show that good artist-product-fit reduces persuasion knowledge and increases perceived credibility of the artist as well as viewers' willingness to share the video through electronic word of mouth (eWOM). These results highlight the need to understand viewers' perceptions of artists in promotional contexts to avoid dysfunctional promotional collaborations.

1 Introduction

Run-DMC's 1986 single “My Adidas” is one of the US hip-hop group's most successful tracks. The song centers on Adidas' iconic “Superstar” sneaker, initiating an enduring advertising phenomenon in which branded products are seamlessly integrated into songs and music videos. The subsequent partnership between Run-DMC and the sporting goods manufacturer paved the way for a successful advertising alliance that has now lasted for almost 40 years, granting Adidas a huge boost in sales and an iconic collaboration for Run-DMC (Baksh-Mohammed and Callison, 2014; Rucker, 2023). The song mentioned is just one of many examples in which the worlds of music and advertising merge through the intended inclusion of branded products (Gloor, 2014; Metcalfe and Ruth, 2020). Music and advertising are inseparably entwined in today's advertising landscape (Ruth and Spangardt, 2017; Spangardt and Ruth, 2018). While recipients are continuously confronted with persuasion attempts due to the interlacing of everyday life with technology and entertainment media, the synthesis of music and advertising in the form of product placements in music videos offers a promising way to reach an increasingly skeptical audience (Matthes et al., 2012). It is therefore not surprising that around half of the music videos in the rap/hip-hop genre contain brand references (Martin and McCracken, 2001). World-renowned rappers such as Drake, Travis Scott and Jay-Z have formed lasting partnerships with well-known brands such as Nike and Puma (Rucker, 2023), continuing the promotional strategy pioneered by Run-DMC. Alliances between artists and brands can build synergistic relationships that can strengthen the public image on both sides, the artists and the brands, leading to mutually beneficial results in terms of financial gains and brand perception (e.g., Schemer et al., 2008; Hudders et al., 2016).

Although branded product placements are ubiquitous in music videos, there is limited research on this phenomenon (Ferguson and Burkhalter, 2015). Previous studies have focused predominantly on the perception of the placed brand, while artists who integrate branded products into their short films have been largely neglected. Therefore, the artist takes center stage in this study. Examining how the fit between the artist and the advertised product influences the artist's perceived credibility and recipients' behavior is of research interest. Contributing to the sparsely researched area and providing recommendations for artists in the first place, this article is also aiming at illustrating that a congruent artist-product fit can be beneficial not only on the artists' side. Maintaining a secular, matching advertising alliance can, as in the case of Run DMC, lead to the collaborative launch of an anniversary Superstar sneaker in 2020−34 years after the release of “My Adidas” (Rucker, 2023).

2 Theory

2.1 Product placements

Product placement can be defined as the “paid inclusion of branded products or brand identifiers, through audio and/or visual means, within mass media programming” (Karrh, 1998, p. 33). The strategy of integrating branded products into audio-visual media for commercial purposes can be traced back to the early days of cinema in the 1890s (Hudson and Hudson, 2006). Initially, branded products were placed rather unsystematically in films primarily to reduce production costs (Karrh et al., 2003). The popularity of product placement as a marketing strategy received a boost with the famous placement of the candy “Reece's Pieces” in the science fiction classic “E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial” in 1982 (Balasubramanian et al., 2006). The placement increased sales of the confectionery, made by the American chocolate manufacturer Hershey's, by 66% (Reed, 1989). Since then, product and brand placement in media content has become an established instrument in consumer marketing (Hudson and Hudson, 2006). While product placements are predominantly integrated into audio-visual media, they can also be embedded in magazines, novels, radio programs, video games, and many other media contexts (Koch, 2016).

The increasing integration of branded products into audio-visual media and the resulting renunciation of traditional advertising formats such as commercials may be due to the increasing audience reactance to interruptive advertising (Matthes et al., 2012). In traditional television, commercial breaks are bypassed by switching channels (Avery and Ferraro, 2000). As predicted by Rust and Oliver (1994), traditional advertising formats such as commercials are “on their deathbed” (Rust and Oliver, 1994, p. 71). This forces companies to use hybrid advertising methods (Balasubramanian, 1994) that are adapted to the recipients' reactance to persuasiveness (Russell, 2002). Product placements that are woven into the plot in a mostly unobtrusive way seem to meet this need. A recent study shows that global revenues from product placements have been on a steep growth curve. Only in 2020 did a pandemic-related decline in global product placement spend undercut the steady growth. However, the situation recovered quickly and spending reliably increased again the following year. Consequently, the total value of product placements in all media is forecast to grow by 14.3% to $26.2 billion by 2022 (PQ Media, 2022). There has been extensive scientific investigation of product placements and their effects on viewers. However, studies on product placements mostly focus on films and TV formats (and especially on social media influencers during the last 5 years), while other relevant media that offer a potential framework for product placements are neglected (Burkhalter et al., 2017).

2.2 Product placements in music videos

Record labels began commissioning music videos for advertising purposes in the mid-1970s. Music video production was given a significant boost in 1981, with the launch of MTV (Music Television), a commercial channel specifically designed for broadcasting music videos (Keazor and Wübbena, 2017). Music videos have since departed from traditional television and are now predominantly located on online platforms such as YouTube, VEVO, and social media platforms (Edmond, 2014; Ruth, 2019). The two most-viewed videos on YouTube until July 2023 were music videos, garnering a collective viewership of over 20 billion clicks (Lohmeier, 2023). Online platforms such as YouTube allow continuous access to musical clips (Keazor and Wübbena, 2017). Furthermore, music videos are typically much shorter than movies or TV formats, making it more likely that viewers will watch a video multiple times (Burkhalter et al., 2017). Given the promising characteristics of music videos, it is hardly surprising that companies have long since recognized this market's suitability as an advertising format to successfully integrate their promotional activities (Davtyan et al., 2021). An early example of product placements in songs is the 1986 release “My Adidas” by the hip-hop group Run-D.M.C. The mere title implies the endorsed product. However, the song cannot be defined as a classic, contractually regulated placement, given that it was only after the title achieved great success and drove up Adidas' sales figures that the sportswear manufacturer signed the group as brand ambassadors for USD 1.5 million (Kaufman, 2003; Baksh-Mohammed and Callison, 2014). Nevertheless, Run-D.M.C. and their song are regarded as pioneers of placements in the music industry (Delattre and Colovic, 2009).

Companies face increasing audience resistance to interruptive advertising (Avery and Ferraro, 2000) and see music videos as an entertainment form “where consumers cannot blatantly avoid an advertising influence” (Matthes et al., 2012, p. 129). The doubling of revenue from product placements in music videos between 2000 and 2010 (Plambeck, 2010) confirms the trend. Meanwhile, record sales are declining (Drücke et al., 2021), and artists are reliant on alternative sources of income. Product placements and associated advertising contracts can provide support for artists to finance tours (Delattre and Colovic, 2009) or reduce production costs (Sánchez-Olmos and Castelló-Martínez, 2020). Branded products also appear spontaneously in music videos due to the artists' food, clothing, or alcohol preferences (Kaufman, 2003). The viewer, however, cannot easily differentiate the artists' motives (Ruth and Spangardt, 2017; Spangardt and Ruth, 2018). Therefore, spontaneous placements are not distinguished from commercial placements in this article and the financial component is assumed.

2.3 Literature review

Although there is currently only limited research on music videos and product placements within them, it has yielded significant findings for artists and advertising companies. Content analysis studies have reported an increase in product placements in songs (de Gregorio and Sung, 2009; Baksh-Mohammed and Callison, 2014; Gloor, 2014; Metcalfe and Ruth, 2020) and music videos (Burkhalter and Thornton, 2012; Sánchez-Olmos and Castelló-Martínez, 2020). They are particularly prevalent in the genres of hip-hop and rap (Martin and McCracken, 2001; Burkhalter and Thornton, 2012; Baksh-Mohammed and Callison, 2014; Metcalfe and Ruth, 2020), and according to recipients, hip-hop music is especially suitable for placing branded products (de Gregorio and Sung, 2009). The most frequently mentioned product categories are cars, clothing, food, and (alcoholic) drinks, as well as media and entertainment products (de Gregorio and Sung, 2009; Metcalfe and Ruth, 2020; Sánchez-Olmos and Castelló-Martínez, 2020). Davtyan et al. (2021) found that repeated exposure to a placement, ranging from four to five insertions per music video, positively influenced recipients' brand memory, brand attitude, purchase intention, and brand advocacy. Matthes et al. (2012) investigated repetition effects based on the mere exposure effect (Zajonc, 1968), which states that solely repeated exposure to stimuli improves attitudes. Their study found an effect only for frequently presented brands in combination with moderate or high viewer involvement (Matthes et al., 2012).

Only a few studies on product placements in music videos have considered the role and influence of the artist. Yet, findings in this stream of research mostly investigate the perception of the placed brand and not the perception of the artist. For example, Hudders et al. (2016) reported that prominently placed products in a music video may harm viewers' brand attitudes and purchase intentions. However, such placements led to improved brand attitudes among respondents who felt strongly connected to the artist, possibly because they paid more attention to the artist than the placement (Hudders et al., 2016). In contrast, Krishen and Sirgy (2016) found that consumers who perceived a high level of self-congruence (i.e., a good match between their self-image and the brand personality) were more likely to have a positive attitude toward the placed brand. They also examined the moderating effects of involvement with the artist and congruence between the artist and the product but found no significant effects on brand attitudes (Krishen and Sirgy, 2016). In a study by Thornton and Burkhalter (2015), viewers' interest in owning a placed brand was formed independently of their preference or aversion to an artist. However, brand interest was significantly higher when the artist interacted with the product than when supporting characters interacted with the product in the music video (Thornton and Burkhalter, 2015). Schemer et al. (2008) experimented with using an authentic rap music video to measure evaluative conditioning effects on viewers. The researchers varied the artists' images and the presence or absence of product placements and found that portraying the artist in a positive context induced more positive attitudes toward the brand, while portraying the artist in a negative context evoked more negative attitudes. Stronger conditioning effects were observed among participants with a preference for hip-hop music. Contrary to the authors' assumption that viewers averse to the genre would not be conditioned or only negatively conditioned, the data showed that they were simply less likely to be conditioned than fans of the genre (Schemer et al., 2008).

Burkhalter et al. (2017) are, to the best of our knowledge, the only researchers to have explored viewers' perceptions of artists promoting brands in music videos. Their findings indicate that viewers prefer to believe that artists genuinely mention or display brands because of their personal experiences and convictions, even if they receive monetary compensation. If viewers perceive the artist as pursuing merely financial motives, both the artist's authenticity and that of the placed brand may be compromised. According to the researchers, placements are perceived as authentic and unadulterated when they align with the artist's genre, image, and lifestyle (Burkhalter et al., 2017). The financial benefits of placements in music videos for an artist are apparent, yet there is a gap in current research regarding the degree to which the viewer's perception of the artist is impacted by product placements. Focusing on the fit between the artist and the product, the present study aimed to investigate the credibility of an artist who places products in their videos and the circumstances under which credibility may be affected or increased. Before outlining the study's methodology and findings, we introduce the theoretical foundations.

2.4 Theoretical background

Product placement research draws on a plethora of theories to explain the efficiency and effects of placement on recipients. The present study uses the match-up hypothesis, the source credibility model, and the persuasion knowledge model, which are briefly explained in the following sections.

2.4.1 Match-up hypothesis

The match-up hypothesis states that advertisements are more effective if the endorsing person fits or is congruent with the advertised brand (Kamins, 1990). Congruence occurs if the relevant characteristics of the speaker and relevant attributes of the brand overlap (Misra and Beatty, 1990). A study by Kahle and Homer (1985), for example, showed that attractive endorsers induced a higher purchase intention and more positive brand attitude in recipients when advertising an attractiveness-related product. Kamins (1990) confirmed these results and found that attractive endorsers promoting an attractiveness-related product were perceived as more credible. Social adaptation theory (Kahle, 1984) and attributional theory (Jones and Davis, 1965) have been used to explain why a recipient may react positively to a congruent speaker–product match (Mishra et al., 2015; Breves et al., 2019). According to social adaptation theory, recipients perceive endorsers as effective sources of new information when their personality is congruent with the advertised brand image (Kamins, 1990). Furthermore, attribution theory states that consumers attribute internal motivational reasons to those who advertise a fitting brand. Viewers want to believe that endorsers who fit the advertised brand also advertise it because they are convinced of it and use it themselves (Koernig and Boyd, 2009; Mishra et al., 2015).

2.4.2 Source credibility

The source credibility model states that the effectiveness of a statement or advertising message depends on the communicator's credibility, which is determined by the expertise and trustworthiness of the spokesperson. Expertise in this context is described as the extent to which a communicator can make valid statements about a particular topic based on their knowledge and experience, whereas trustworthiness is perceived when statements are considered honest and objective (Erdogan, 1999; Jackob and Hueß, 2016). Ohanian (1990) subsequently added the physical attractiveness of the communicator to the source credibility model. Taken together, expertise, trustworthiness, and physical attractiveness are the three main criteria that determine the perception of a spokesperson's credibility (Ohanian, 1990).

A promising combination of the source credibility model and the match-up hypothesis has been reported in numerous studies, confirming that a match between an advertising spokesperson and the advertised product can influence consumer behavior (Mishra et al., 2015) and lead to increased perceived credibility of the spokesperson (Kamins, 1990; Kamins and Gupta, 1994; Koernig and Boyd, 2009; Breves et al., 2019). Early studies on this topic were conducted by Kamins and Gupta (1994), who compared print adverts for computers and trainers. Advertisements in which the spokesperson's image matched that of the advertised product led to higher perceived credibility of the spokesperson and enhanced evaluation rates of the advertising brand (Kamins and Gupta, 1994). In a recent study on the match-up hypothesis in a social media research context, Breves et al. (2019) presented participants with a manipulated image of an influencer and written information about them. They were then shown sponsored image content for a KIA car brand. The advertising spokesperson was described as either an environmentally conscious cyclist or a car enthusiast, to manipulate the fit with the advertised product. The results once again indicated that a high influencer–brand fit led to increased perceived influencer credibility and increased behavioral intentions.

2.4.3 Persuasion knowledge

A significant factor that can influence the effectiveness of product placements is the recipient's knowledge about the persuasive intention of media content. According to Friestad and Wright (1994) persuasion knowledge model, consumers continuously learn to recognize, interpret, evaluate, and develop defense mechanisms against the persuasive attempts they are confronted with (Friestad and Wright, 1994). In the case of traditional advertising such as commercial breaks, viewers are often aware of persuasive attempts. However, in the case of product placements, the persuasive intent is not necessarily clear to viewers, as placements are typically not visibly labeled as advertisements (Koch, 2016). While congruent information may enhance realism, incongruent information can raise suspicions about the appearance of a brand (Russell, 2002). Placements that do not match the program in which they are embedded are perceived as unpleasant in terms of reception experience and their persuasive intent is more easily recognized (Koch, 2016). Incongruity in the form of a mismatch between the advertising character and the brand can make viewers more aware of the inconsistency of the advertising content (Sujan, 1985; Koernig and Boyd, 2009). Furthermore, the perception of incongruent information requires greater cognitive processing effort, which in turn increases attention and enhances viewers' memory (Mandler, 1982; Ferguson and Burkhalter, 2015). An increased processing time could trigger the activation of persuasion knowledge and thus the formation of skepticism, distrust, and defense mechanisms (Ferguson and Burkhalter, 2015). Based on the aforementioned points, the consideration of the persuasion knowledge model in conjunction with the match-up hypothesis and source credibility model appears to be sensible in order to determine the extent to which knowledge of persuasive attempts influences the relationship between congruence and credibility.

2.5 Hypotheses

When an artist incorporates a product or brand into his or her music video, it is promotional content that is not explicitly labeled as such. Consequently, awareness of the video's persuasive intent could be activated. Consistent with the preceding discussion, it is hypothesized that an incongruent artist-product fit fosters higher cognitive elaboration and skepticism toward the music video and the artist, which, in turn, can activate persuasion knowledge. In contrast, it seems plausible that a congruent artist-product fit does not lead to increased persuasion knowledge, as congruence should not raise suspicions about the product's appearance in the music video. Consequently, the following first hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 1: A congruent artist-product fit activates less persuasion knowledge than an incongruent artist-product fit.

Consequently, we expect that a high fit between the artist and the advertised product will lead to higher perceived credibility. While the original model of source credibility includes the factors of trustworthiness, expertise, and attractiveness, Breves et al. (2019) claimed that there is no reliable empirical reason for the congruence between the spokesperson and the product to affect their perceived physical attractiveness. This assumption was based on previous research that examined the influence of congruence on the credibility of a source, but either did not explicitly incorporate and clearly define physical attractiveness (Kamins, 1990; Kamins and Gupta, 1994) or solely considered the factors of trustworthiness and expertise to determine perceived credibility (Koernig and Boyd, 2009). Additionally, the undifferentiated impacts of congruence on the individual dimensions of the source credibility scale reported by Mishra et al. (2015) led Breves et al. (2019) to conclude that only trustworthiness and expertise should be positively affected by a high spokesperson–product fit. This assumption was confirmed by their study and provides a valid basis for limiting perceived credibility in this study to the constructs of trustworthiness and expertise. The second hypothesis to be tested is therefore:

Hypothesis 2: A congruent artist–product fit leads to higher perceived credibility than an incongruent artist–product fit.

Furthermore, viewers' behavioral intentions depending on the artist–product fit are of interest. Here, electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) seems to be one of the most relevant behavioral intentions of music video recipients for the present research, because artists benefit from recipients' sharing and promoting of the music videos. eWOM refers to the digital, internet-based form of word-of-mouth that is an extension of traditional direct word-of-mouth (Lis and Korchmar, 2013). Research on influencer marketing has confirmed that congruence between the advertising spokesperson and the promoted product can positively influence users' behavioral intentions (Phua et al., 2018; Breves et al., 2019; Lee et al., 2021). We therefore assume that recipients' willingness to share a music video with others through eWOM increases when the product shows a good fit with the artist.

Hypothesis 3: A congruent artist–product fit leads to a greater willingness to share the music video with others (eWOM willingness) than an incongruent artist–product fit.

Moreover, it seems theoretically plausible that the first effect, namely less persuasive knowledge, in turn leads to higher perceived credibility and thus greater willingness to share about eWOM. Any alternative sequence of effects would be implausible, and recent studies on persuasive knowledge show that this sequence of effects can be assumed. For example, Lee et al. (2021) found that consumers' general skepticism toward advertising content diminishes the credibility of advertising figures on Instagram. Through their study, researchers Hsieh et al. (2012) discovered that viewers rate online videos poorly and are less inclined to share them when they have detected the videos' persuasive intent. According to a study by Boerman et al. (2017), the identification of a message as a persuasion attempt leads to a reduced willingness to spread electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) on Facebook. Therefore, we assume the following serial mediation hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4: The effect of greater eWOM willingness when viewing a music video with a congruent artist-product fit (compared to an incongruent artist-product fit) is mediated by less persuasion knowledge and, subsequently, increased perceived credibility of the artist.

Understanding the impact of genre preferences on product placements in music videos is crucial from a marketing and artists' perspective. In a study on verbal placements in songs, Ferguson and Burkhalter (2015) manipulated the fit between the placed product and the hip-hop genre by placing brands that either did or did not represent hip-hop culture. A high affinity for hip-hop culture was associated with a better rating of the congruent brand. However, the researchers acknowledged that a study of audio-visual placements in music videos would be desirable to confirm such an effect (Ferguson and Burkhalter, 2015). Delattre and Colovic (2009) also found that listeners remembered significantly more verbally placed brands if they favored the song or the artist than if they did not. However, they could not identify an influence of genre preference (Delattre and Colovic, 2009). In their study of conditioned learning, Schemer et al. (2008) found that music preference predicted brand attitude. Stronger conditioning effects were measured for participants with a preference for rap music. Conditioning may be positive or negative. Participants who showed no preference for the genre were generally less conditionable (Schemer et al., 2008). The findings on the potential influence of genre preference are therefore ambiguous and partly limited to verbal placements (Delattre and Colovic, 2009; Ferguson and Burkhalter, 2015). In the present study, we therefore decided to include genre preference in order to control for its effects.

3 Method

3.1 Design

To test our hypotheses, an experimental online study was conducted in Germany using a two-factor experiment (congruent vs. incongruent artist–product fit) with a between-subjects design. The German participants viewed a professionally produced German hip-hop music video (2:43 min) featuring a placement of the widely recognized soft drink “Fanta,” which was visually displayed and verbally mentioned multiple times in the verses and chorus (see https://studien.mwk.uni-wuerzburg.de/BA_Kraft_Musikvideo.mp4).

The music video was freely available on YouTube and had only received just over 2,000 clicks at the time the questionnaire was created, so we assumed that the artist (rapper RIHHI) and the video (with the song “Tropical Flavors”) were unknown to most respondents prior to their participation.

The artist's unfamiliarity was a necessary prerequisite for the manipulation of the artist-product-fit. Two authentic-looking magazine articles from a fictitious online magazine were created for this purpose. Both articles were designed identically and contained the same pictures of the musician, which were taken from his public Instagram accounts. The only difference between the two manipulations was the text. Fictitious verbatim quotes from the interviewed musician were used to make the article appear as realistic as possible. In the congruent condition, the rapper was portrayed as a fast food lover who loves burgers and wants to open his own fast food restaurant. This was intended to create a good fit between the musician and the soft drink. In contrast, another article was written that portrayed the rapper as an extremely nutrition-conscious person who is committed to educating young people about diabetes, which consequently made for a less fitting connection between the musician and the soft drink. The participants were randomly shown one of the two magazine articles, which they were instructed to read carefully before viewing the music video.

3.2 Procedure and measurements

The participants were recruited through Facebook and Instagram. They were asked to complete the survey in a quiet place without interruption. As they would be watching a music video, they were asked to use headphones or set the volume to a moderate level. The actual purpose of the study was not disclosed beforehand. The participants were instructed to carefully read the magazine article that was randomly assigned to them. Subsequently, the same music video was played for all participants. To ensure full reception of the stimuli, the “Continue” button was not displayed until 55 and 160 s after presentation of the article and the video, respectively. After watching the clip, a treatment check was conducted in which the participants were asked to select the brand they had seen in the music video from the six provided options.

Subsequently, the participants were asked to evaluate the rapper's credibility using two dimensions of the 7-point semantic differential scale of source credibility by Ohanian (1990): trustworthiness (five items; α = 0.91; M = 3.6, SD = 1.37) and expertise (five items; α = 0.89; M = 3.79, SD = 1.22). The bipolar items “knowledgeable/ignorant” and “expert/non-expert” were replaced by the newly formulated items “capable/incapable” and “professional/unprofessional,” to make them more relevant to the evaluation of an artist. To test the formulated hypotheses, the two dimensions were combined (10 items; α = 0.94; M = 3.69, SD = 1.23).

The participants' willingness to share the music video via eWOM was measured using two items adapted from Chiu et al. (2007) and supplemented with two additional items (Lee et al., 2021) that reflected more extensive opportunities for participation in eWOM music video sharing (four items; α = 0.91; M = 2.57, SD = 1.61). They were asked to indicate their agreement with items such as “I will give the music video a thumbs up” on a 7-point Likert scale.

The participants' persuasion knowledge was assessed using six slightly adapted items based on previous work by Boerman et al. (2017). The participants rated their agreement with items such as “I think the music video I watched was an advertisement” on a 7-point Likert scale (six items; α = 0.70; M = 4.61, SD = 1.07).

Hip-hop genre preference was assessed using a newly constructed single item (one item; M = 4.85, SD = 1.92) with a scale ranging from 1 (“I am not a fan of hip-hop music at all”) to 7 (“I am a big fan of hip-hop music”).

The participants were then asked whether they had known the artist and the music video before the study (“yes” or “no”). To complete the questionnaire, participants were asked to provide personal and demographic information about their age, gender and level of education.

3.3 Participants

Unusual and incomplete cases were eliminated from the sample. Additionally, the age limit was lowered to 29 years and under, because the hip-hop main target group of 14–29-year-olds was considered in this study (Lohmeier, 2024). The 144 participants (64.6% female) had an average age of 21.36 years (SD = 3.94) and an age range of 16–29 years. Approximately 70% were highly educated or possessed a high school diploma. All participants correctly identified the product Fanta in the treatment check. Before participation, none of the participants was familiar with the rapper and the music video. The two experimental groups did not differ in terms of age [t(142) = 1.58, p = 0.12], gender [χ2(1, N = 144) = 2.46, p = 0.12], or educational level [χ2(1, N = 144) = 0.83, p = 0.36].

4 Results

Hypotheses 1–3 postulate that a congruent artist–product fit activates less persuasion knowledge and leads to a higher perceived artist credibility and a greater willingness to share the music video with others (eWOM willingness) than an incongruent artist–product fit. To validate these hypotheses, three separate one-way ANOVAs were conducted, with the experimental condition of congruent or incongruent artist–product fit serving as the independent variable. As predicted, a congruent artist–product fit activated less persuasion knowledge (M = 4.41; SD = 0.94) than an incongruent artist–product fit [M = 4.81; SD = 1.16; F(1, 142) = 5.84, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.036]. A congruent artist–product fit also led to higher artist credibility (M = 4.01, SD = 1.16) than an incongruent artist–product fit [M = 3.38, SD = 1.24; F(1, 142) = 9.70, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.064]. And finally, a congruent artist–product fit resulted in a higher willingness to share the video with others via social media (eWOM) (M = 2.89, SD = 1.69) than an incongruent artist–product fit [M = 2.26, SD = 1.48; F(1, 142) = 5.64, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.038]. Consequently, hypotheses 1–3 were supported.

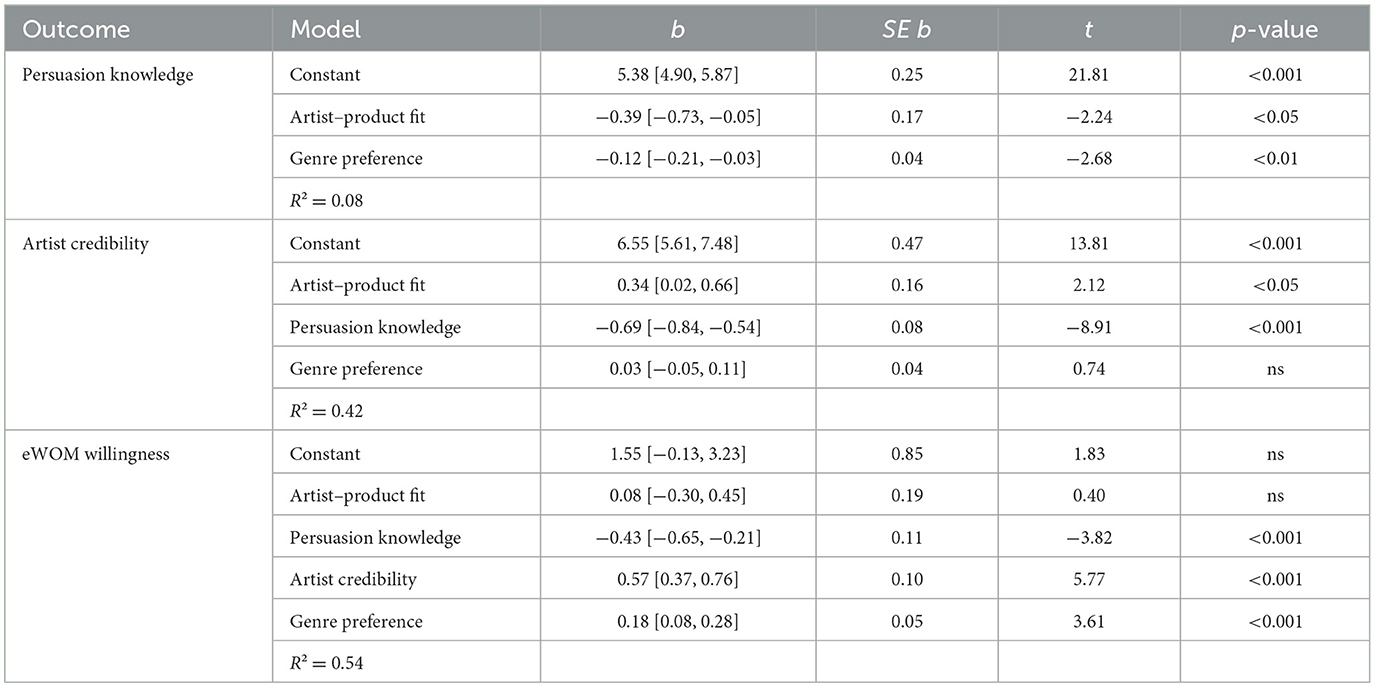

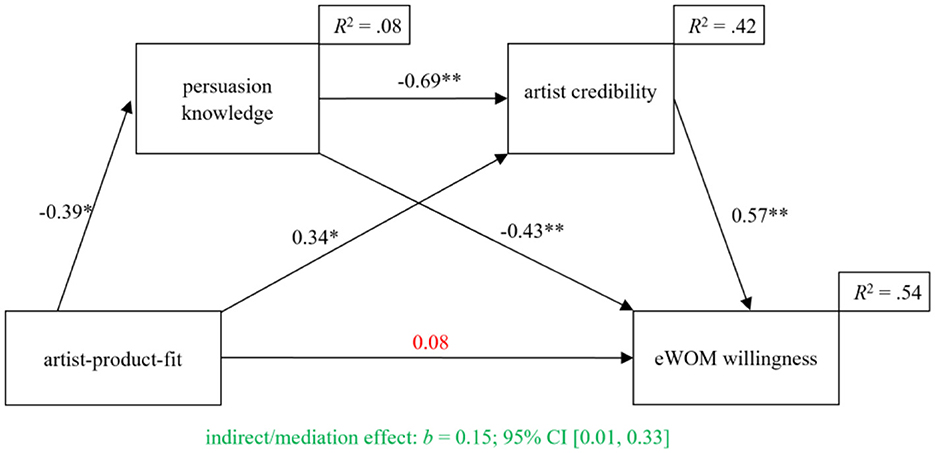

A serial mediation analysis with genre preference as covariate was conducted to test hypothesis 4, using the PROCESS 4.0 macro introduced by Hayes (2018). The bootstrapping method was applied (m = 5.000), and all reported regression coefficients (see Table 1) are unstandardized. The indirect effect of a congruent artist-product fit (compared to an incongruent artist-product fit) on eWOM willingness via reduced persuasion knowledge and, subsequently, stronger perceived credibility of the artist was considered significant [b = 0.15; 95% CI (0.01, 0.33)], whereas the direct effect became non-significant [b = 0.08; 95% CI (−0.30, 0.45)], supporting hypothesis 4. The model explained 54 percent of the variance in viewers' eWOM willingness (see Figure 1).

Table 1. Serial mediation analysis with unstandardized regression coefficients and bootstrapping (m = 5.000; Hayes, 2018).

Figure 1. Indirect effect of artist-product-fit on eWOM willingness mediated by persuasion knowledge and artist credibility. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

With regard to the impact of genre preference we see a negative influence on the activation of persuasion knowledge (b = −0.12, p < 0.01) which is supportive for the artist credibility, and a positive influence on eWOM willingness (b = 0.18, p < 0.001).

5 Discussion

5.1 Interpretation and implications

In contrast to previous research, the present study did not focus on the placed brand and its perceived attributes. Rather, the study is the first, as far as we are aware, to deliberately explore the effects of product placement on artists rather than gauging its effects on brands and consequently the advertising industry. Our findings provide novel insights into the multifarious ways in which product placement can influence an artist's image. The findings confirm the presumed influence of congruence between an artist and the product featured in their music video. Therefore, when the artist's image matched the advertised product, the viewers activate less persuasion knowledge, find the artist to be more credible and are more willing to share the music video than when the artist–product fit is incongruent. Fans of the music genre are less critical and activate less persuasion knowledge. Consequently, they find the artist to be more credible and are more willing to share the video than those viewers who do not consider themselves fans. The rationale behind these findings can be seen in line with the stronger conditioning effects for fans of the genre, as previously posited by Schemer et al. (2008).

This study contributes to the growing research on product placements in music videos and counters the empirical concentration on films and TV formats. In contrast to previous investigations, the present study did not focus on the situated brand and its corresponding perception. Instead, the artist was the object of scrutiny. Additionally, by applying the match-up hypothesis and the closely connected source credibility model, two important trends in the endorsement literature have been applied to another medium, the music video. The overlap of both models received statistical confirmation: credibility ratings were higher when there was a match between the spokesperson and the product.

From a pragmatic standpoint, the outcomes of the current study hold significant implications for music producers and empower the authors to offer specific directives. Artists who produce music videos and integrate advertising products should ensure that the brand or product aligns with their image. Although contracting with a brand may appear financially lucrative to an artist, divergences between the product and the artist may compromise their credibility. In such cases, it is advisable to refrain from cooperation or to identify brands that align with the artist's image (Breves et al., 2019). In addition, artists should be careful to maintain a credible image, as this can have a positive impact on the audience's behavioral intentions, as demonstrated by the findings of the current study. Lastly, artists who may have limited exposure to advertising research in their profession should be made aware that viewers can identify the persuasive intent of ostensibly covert advertising messages. If a product is integrated thoughtlessly and is perceived by viewers as an attempt at persuasion, it can have adverse consequences for the artist. Therefore, product placement agents or advertising agencies should advise artists to carefully integrate products into music videos to avoid activating persuasion knowledge and mitigate the risk of negative audience reactions. Furthermore, unsuitable brands should only be considered by artists when the target audience has a very strong preference for the genre and therefore develop less persuasion knowledge, given that a high preference for the hip-hop genre led to both higher perceived credibility and higher behavioral intentions, whereas high levels of persuasion knowledge diminished both of these variables.

Although the artist is of particular interest in this study, the results findings are equally important for brands and advertising specialists. Positive effects of a congruent artist-product fit should also yield positive effects for brands who place products in music videos. A current negative example that illustrates this connection is the debate about the rapper Ye (formerly Kanye West). Adidas and Ye have had an advertising partnership known as “Yeezzy” since 2016, which has marketed clothing and especially shoes with great commercial success (Runau et al., 2016). Ye increasingly attracted public attention with anti-Semitic and racist statements (Bücker, 2022), which not only had a lasting negative impact on his image, but also on the German company Adidas. Following harsh criticism of the partnership and public pressure to dissolve the collaboration with the rapper, Adidas finally terminated the partnership in October 2022 and suffered a loss of sales worth 1.2 billion euros (Ritzer, 2023). The company, which is committed to fighting hate, discrimination and antisemitism (Adidas Press Release, 2023), could understandably not continue to support this alliance. In order to avert such serious economic and image damaging consequences, it is accordingly indispensable for companies to monitor and constantly question the fit of artists under advertising contracts.

5.2 Limitations and future research

Although a treatment check ensured that the subjects correctly recognized the product placement, and much effort was put into the production of two realistic-looking magazine articles to manipulate the artist-product fit, an additional manipulation check for this fit was neglected. Since all hypotheses were confirmed, it can be assumed that the manipulation worked, because the experimental groups did not differ in any other factor, but future studies should include a manipulation check (and also validate the manipulation with a pretest) in order to be able to rule out a failed effect of the manipulation as the cause if the hypotheses are not confirmed.

Moreover, to comprehensively assess the artist–recipient relationship and all of the dependent and moderating variables, future research should adopt a more realistic evaluation of this relationship, considering not only the evaluation of credibility but also individuals' preferences and parasocial relationships (Horton and Wohl, 1956) with their favorite artists. The inclusion of parasocial relationships, as demonstrated by Breves et al. (2019), can offer valuable insights, as individuals with a stronger parasocial relationship with a social media entity base their credibility judgments on prior experiences with the influencer rather than on influencer–product congruency. Against this background, further studies could investigate, for example, how different matching product placements have an effect in the environment of a well-known and popular artist. Is the effect of the perception of unsuitable product placements outshone or balanced out by positive parasocial relationships with the artist, or are such unsuitable products even more noticeable because they do not fit into the artist's familiar scheme and are therefore likely to irritate fans in particular? Of course, such studies would be difficult to implement, because which well-known artist would be willing to shoot a music video in two versions with two differently fitting products? Alternatively, if two different music videos by the same artist were used, one featuring a more suitable product and the other a very unsuitable one, then the videos would differ in many other ways, for example in the song content - although external validity would be given for such stimuli, internal validity would be severely limited, so that cause-and-effect attributions could no longer be made beyond doubt.

The present study focused on the placement of a soft drink, and while beverages are commonly featured as product placements in music videos (Sánchez-Olmos and Castelló-Martínez, 2020), it would be advantageous to compare various products to examine potential differences in artist perception. Future studies could also benefit from a more realistic reception scenario. For instance, YouTube provides information on the numbers of likes, clicks, and subscribers of the channel, which have been shown to positively influence perceptions in influencer research (De Veirman et al., 2017). Therefore, it would be worthwhile to investigate the effect of the number of subscribers or “thumbs-up” ratings on the perception of artist credibility with artist–product congruency. Certainly, exploring multiple music genres would offer an interesting research approach. In any case, future research should compensate for the limitations of this study in order to provide further recommendations for brand managers and music creators, especially in terms of practical implications.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not mandatory for this study. In Germany, there is no legal obligation to have every study approved by an Ethics Committee, and it is common practice here to do so only if harm to participants is expected. In this study, as can be seen from the stimulus and measurements section of this paper, no such harm was expected, so we did not seek approval. Participants of 16 years and older simply had to watch a funny hip-hop video, as young people see every day on TikTok or YouTube, and answer questions about their perceptions. The study was conducted in accordance with the national guidelines of the German Research Foundation—guideline 10 “Legal and ethical framework conditions, rights of use” was also implemented (you can also see there that an ethics vote is not explicitly required). The participants gave their written consent to participate in this study before the study and were able to delete their data at any time after the study via a self-generated code and thus withdraw their informed consent. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

HS: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JK: Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This publication was supported by the Open Access Publication Fund of the University of Würzburg.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2024.1396483/full#supplementary-material

References

Adidas Press Release (2023). Adidas to release existing YEEZY product in May 2023. Available at: https://www.adidas-group.com/en/media/press-releases/adidas-to-release-existing-yeezy-product-in-may-2023

Avery, R. J., and Ferraro, R. (2000). Verisimilitude or advertising? Brand appearances on prime-time television. J. Consum. Aff. 34, 217–244. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6606.2000.tb00092.x

Baksh-Mohammed, S., and Callison, C. (2014). “Listening to Maybach in my Maybach”: evolution of product mention in music across the millennium's first decade. J. Promot. Manag. 20, 20–35. doi: 10.1080/10496491.2013.829162

Balasubramanian, S. K. (1994). Beyond advertising and publicity: hybrid messages and public policy issues. J. Advert. 23, 29–46. doi: 10.1080/00913367.1943.10673457

Balasubramanian, S. K., Karrh, J. A., and Patwardhan, H. (2006). Audience response to product placements: an integrative framework and future research agenda. J. Advert. 35, 115–141. doi: 10.2753/JOA0091-3367350308

Boerman, S. C., Willemsen, L. M., and van der Aa, E. P. (2017). “This post is sponsored”: effects of sponsorship disclosure on persuasion knowledge and electronic word of mouth in the context of Facebook. J. Interact. Mark. 38, 82–92. doi: 10.1016/j.intmar.2016.12.002

Breves, P. L., Liebers, N., Abt, M., and Kunze, A. (2019). The perceived fit between Instagram influencers and the endorsed brand: how influencer–brand fit affects source credibility and persuasive effectiveness. J. Advert. Res. 59, 440–454. doi: 10.2501/JAR-2019-030

Bücker, T. (2022). Adidas stellt Partnerschaft mit Kanye West in Frage [Adidas questions partnership with Kanye West]. Available at: https://www.tagesschau.de/wirtschaft/unternehmen/adidas-kanye-west-yeezy-aktie-101.html

Burkhalter, J. N., Curasi, C. F., Thornton, C. G., and Donthu, N. (2017). Music and its multitude of meanings: exploring what makes brand placements in music videos authentic. J. Brand Manag. 24, 140–160. doi: 10.1057/s41262-017-0029-5

Burkhalter, J. N., and Thornton, C. G. (2012). Advertising to the beat: an analysis of brand placements in hip-hop music videos. J. Mark. Commun. 20, 366–382. doi: 10.1080/13527266.2012.710643

Chiu, H.-C., Hsieh, Y.-C., Kao, Y.-H., and Lee, M. (2007). The determinants of e-mail receivers' disseminating behaviors on the internet. J. Advert. Res. 47, 524–534. doi: 10.2501/S0021849907070547

Davtyan, D., Cunningham, I., and Tashchian, A. (2021). Effectiveness of brand placements in music videos on viewers' brand memory, brand attitude and behavioral intentions. Eur. J. Mark. 55, 420–443. doi: 10.1108/EJM-08-2019-0670

de Gregorio, F., and Sung, Y. (2009). Giving a shout out to Seagram's gin: extent of and attitudes towards brands in popular songs. J. Brand Manag. 17, 218–235. doi: 10.1057/bm.2009.4

De Veirman, M., Cauberghe, V., and Hudders, L. (2017). Marketing through Instagram influencers: the impact of number of followers and product divergence on brand attitude. Int. J. Advert. 36, 798–828. doi: 10.1080/02650487.2017.1348035

Delattre, E., and Colovic, A. (2009). Memory and perception of brand mentions and placement of brands in songs. Int. J. Advert. 28, 807–842. doi: 10.2501/S0265048709200916

Drücke, F., Herrenbrück, S., Sobbe, G., Reitz, S., and Hartmann, C. (2021). Musikindustrie in Zahlen 2020 [Music industry in numbers 2020]. Available at: https://www.musikindustrie.de/fileadmin/bvmi/upload/06_Publikationen/MiZ_Jahrbuch/2020/BVMI_Musikindustrie_in_Zahlen_2020.pdf

Edmond, M. (2014). Here we go again: Music videos after YouTube. Telev. New Media 15, 305–320. doi: 10.1177/1527476412465901

Erdogan, B. Z. (1999). Celebrity endorsement: a literature review. J. Mark. Manag. 15, 291–314. doi: 10.1362/026725799784870379

Ferguson, N. S., and Burkhalter, J. N. (2015). Yo, DJ, that's my brand: an examination of consumer response to brand placements in hip-hop music. J. Advert. 44, 47–57. doi: 10.1080/00913367.2014.935897

Friestad, M., and Wright, P. (1994). The persuasion knowledge model: how people cope with persuasion attempts. J. Consum. Res. 21, 1–31. doi: 10.1086/209380

Gloor, S. (2014). Songs as branding platforms? A historical analysis of people, places, and products in pop music lyrics. J. Music Entertain. Ind. Educ. Assoc. 14, 39–60. doi: 10.25101/14.2

Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

Horton, D., and Wohl, R. R. (1956). Mass communication and para-social interaction: observations on intimacy at a distance. Psychiatry 19, 188–211. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1956.11023049

Hsieh, J.-K., Hsieh, Y.-C., and Tang, Y.-C. (2012). Exploring the disseminating behaviors of eWOM marketing: persuasion in online video. Electron. Commer. Res. 12, 201–224. doi: 10.1007/s10660-012-9091-y

Hudders, L., Cauberghe, V., Faseur, T., and Panic, K. (2016). “How to pass the Courvoisier? An experimental study on the effectiveness of brand placements in music videos,” in Advertising in New Formats and Media: Current Research and Implications for Marketer, eds. P. de Pelsmacker (Leeds: Emerald Group Publishing Limited), 361–378. doi: 10.1108/978-1-78560-313-620151017

Hudson, S., and Hudson, D. (2006). Branded entertainment: a new advertising technique or product placement in disguise? J. Mark. Manag. 22, 489–504. doi: 10.1362/026725706777978703

Jackob, N., and Hueß, C. (2016). “Communication and persuasion” in Schlüsselwerke der Medienwirkungsforschung [Key Works in Media Effects Research], ed. M. Potthoff (New York, NY: Springer VS), 49–60. doi: 10.1007/978-3-658-09923-7_5

Jones, E., and Davis, K. (1965). From acts to dispositions: the attribution process in person perception. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2, 219–266. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60107-0

Kahle, L. R. (1984). Attitudes and Social Adaptation: A Person-situation Interaction Approach. Elmsford, NY: Pergamon Press.

Kahle, L. R., and Homer, P. M. (1985). Physical attractiveness of the celebrity endorser: a social adaptation perspective. J. Consum. Res. 11, 954–961. doi: 10.1086/209029

Kamins, M. A. (1990). An investigation into the “Match-up” hypothesis in celebrity advertising: when beauty may be only skin deep. J. Advert. 19, 4–13. doi: 10.1080/00913367.1990.10673175

Kamins, M. A., and Gupta, K. (1994). Congruence between spokesperson and product type: a matchup hypothesis perspective. Psychol. Mark. 11, 569–586. doi: 10.1002/mar.4220110605

Karrh, J. A. (1998). Brand placement: a review. J. Curr. Issues Res. Advert. 20, 31–49. doi: 10.1080/10641734.1998.10505081

Karrh, J. A., McKee, K. B., and Pardun, C. J. (2003). Practitioners' evolving views on product placement effectiveness. J. Advert. Res. 43, 138–149. doi: 10.2501/JAR-43-2-138-149

Kaufman, G. (2003). Push the Courvoisier: Are rappers paid for product placement? Available at: http://www.mtv.com/news/1472393/push-the-courvoisier-are-rappers-paid-for-product-placement/

Keazor, H., and Wübbena, T. (2017). “Musikvideo [Music video],” in Handbuch Popkultur [Handbook Pop Culture], eds. T. Hecken, and M. S. Kleiner (Stuttgart: J. B. Metzler Verlag), 173–177. doi: 10.1007/978-3-476-05601-6_33

Koch, T. (2016). “Wirkung von product placements [The effect of product placements],” in Handbuch Werbeforschung [Handbook of Advertising Research], eds. G. Siegert, W. Wirth, P. Weber, and J. A. Lischka (New York, NY: Springer), 373–394. doi: 10.1007/978-3-531-18916-1_17

Koernig, S. K., and Boyd, T. C. (2009). To catch a tiger or let him go: the match-up effect and athlete endorsers for sport and non-sport brands. Sport Mark. Q. 18, 25–37.

Krishen, A. S., and Sirgy, M. J. (2016). Identifying with the brand placed in music videos makes me like the brand. J. Curr. Issues Res. Advert. 37, 45–58. doi: 10.1080/10641734.2015.1119768

Lee, S. S., Chen, H., and Lee, Y.-H. (2021). How endorser-product congruity and self-expressiveness affect Instagram micro-celebrities' native advertising effectiveness. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 31, 149–162. doi: 10.1108/JPBM-02-2020-2757

Lis, B., and Korchmar, S. (2013). “Die digitale mundpropaganda (Electronic word-of-mouth) [The digital word of mouth (electronic word-of-mouth)],” in Digitales Empfehlungsmarketing: Konzeption, Theorien und Determinanten Zur Glaubwürdigkeit des Electronic Word-Of-Mouth (EWOM) [Digital Referral Marketing: Concept, Theories and Determinants On the Credibility of Electronic Word-Of-Mouth (EWOM)], ed. B. Lis (New York, NY: Springer), 11–20. doi: 10.1007/978-3-658-01008-9_3

Lohmeier, L. (2023). Ranking der meistgenutzten YouTube-Videos aller Zeiten nach der Anzahl der Views bis Juli 2023 [Ranking of the most viewed YouTube videos of all time by number of views until July 2023]. Available at: https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/246583/umfrage/meistgenutzte-youtube-videos-weltweit/

Lohmeier, L. (2024). Beliebteste Musikrichtungen in Deutschland unterteilt nach Altersgruppen im Jahr 2023 [Most popular music genres in Germany by age group in 2023]. Available at: https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/893002/umfrage/umfrage-in-deutschland-zu-den-beliebtesten-musikrichtungen-nach-altersgruppen/

Mandler, G. (1982). “The structure of value: accounting for taste,” in Affect and Cognition: 17th Annual Carnegie Mellon Symposium on Cognition, eds. M. S. Clark and S. T. Fiske (London: Psychology Press), 3–36.

Martin, B. A., and McCracken, C. A. (2001). Music marketing: music consumption imagery in the UK and New Zealand. J. Consum. Mark. 18, 426–436. doi: 10.1108/EUM0000000005602

Matthes, J., Wirth, W., Schemer, C., and Pachoud, N. (2012). Tiptoe or tackle? The role of product placement prominence and program involvement for the mere exposure effect. J. Curr. Issues Res. Advert. 33, 129–145. doi: 10.1080/10641734.2012.700625

Metcalfe, T., and Ruth, N. (2020). Beamer, Benz, or Bentley: mentions of products in hip hop and RandB music. Int. J. Music Bus. Res. 9, 41–62.

Mishra, A. S., Roy, S., and Bailey, A. A. (2015). Exploring brand personality-celebrity endorser personality congruence in celebrity endorsements in the Indian context. Psychol. Mark. 32, 1158–1174. doi: 10.1002/mar.20846

Misra, S., and Beatty, S. E. (1990). Celebrity spokesperson and brand congruence. J. Bus. Res. 21, 159–173. doi: 10.1016/0148-2963(90)90050-N

Ohanian, R. (1990). Construction and validation of a scale to measure celebrity endorsers' perceived expertise, trustworthiness, and attractiveness. J. Advert. 19, 39–52. doi: 10.1080/00913367.1990.10673191

Phua, J., Lin, J.-S., and Lim, D. J. (2018). Understanding consumer engagement with celebrity-endorsed e-cigarette advertising on Instagram. Comput. Human Behav. 84, 93–102. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2018.02.031

Plambeck, J. (2010). Product placement grows in music videos. New York Times. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2010/07/06/business/media/06adco.html#:~:text=According%20to%20a%20report%20released,2.8%20percent%2C%20to%20%243.6%20billion

PQ Media (2022). Global Product Placement Spend Surged 12.3% in 2021, After Worst Decline in Pandemic-Struck 2020; Spend to Grow at Faster 14.3% in 2022, Fueled By Digital, TV, Music. Available at: https://www.prweb.com/releases/2022/8/prweb18838348.htm

Reed, J. D. (1989). Show business: Plugging away in Hollywood. Available at: http://content.time.com/time/subscriber/article/0,33009,956646,00.html

Ritzer, U. (2023). Adidas in der Krise: Das verheerende Erbe des Rappers Kanye West [Adidas in crisis: the devastating legacy of rapper Kanye West]. Available at: https://www.sueddeutsche.de/wirtschaft/adidas-verlust-kanye-west-1.5748585

Rucker, J. (2023). The History and Legacy of the Run-DMC adidas Partnership. Available at: https://www.one37pm.com/style/run-dmc-adidas-partnership

Runau, J., Schreiber, K., Steffen, S., and Stöhr, C. (2016). YEEZY - adidas und Kanye West schreiben Geschichte mit neuer Partnerschaft adidas + KANYE WEST [YEEZY - adidas and Kanye West make history with new partnership adidas + KANYE WEST]. Available at: https://www.adidas-group.com/de/medien/newsarchiv/pressemitteilungen/2016/adidas-und-kanye-west-schreiben-geschichte-mit-neuer-partnerscha/

Russell, C. A. (2002). Investigating the effectiveness of product placements in television shows: the role of modality and plot connection congruence on brand memory and attitude. J. Consum. Res. 29, 306–318. doi: 10.1086/344432

Rust, R. T., and Oliver, R. W. (1994). The death of advertising. J. Advert. 23, 71–77. doi: 10.1080/00913367.1943.10673460

Ruth, N. (2019). “Musik auf Online- und Mobilmedien [Music on online and mobile media],” in Handbuch Musik und Medien. Interdisziplinärer Überblick über die Mediengeschichte der Musik [Handbook of Music and Media. Interdisciplinary overview of the media history of music], ed. H. Schramm, 2nd Edn. (New York, NY: Springer VS), 225–252. doi: 10.1007/978-3-658-21899-7_9

Ruth, N., and Spangardt, B. (2017). Research trends on music and advertising. Rev. Mediterr. Commun. 8, 13–23. doi: 10.14198/MEDCOM2017.8.2.1

Sánchez-Olmos, C., and Castelló-Martínez, A. (2020). Brand placement in music videos: artists, brands and products appearances in the Billboard Hot 100 from 2003 to 2016. J. Promot. Manag. 26, 874–892. doi: 10.1080/10496491.2020.1745986

Schemer, C., Matthes, J., Wirth, W., and Textor, S. (2008). Does “Passing the Courvoisier” always pay off? Positive and negative evaluative conditioning effects of brand placements in rap videos. Psychol. Mark. 25, 923–943. doi: 10.1002/mar.20246

Spangardt, B., and Ruth, N. (2018). “Werbung und Musik: Versuch einer Typologie ihrer Beziehung mit einem Plädoyer für mehr interdisziplinäre Forschung [Advertising and music: an attempt at a typology of their relationship with a plea for more interdisciplinary research],” in Musik und Stadt: Jahrbuch für Musikwirtschafts- und Musikkulturforschung 2/2018 [Music and the City: Yearbook for Music Business and Music Culture Research 2/2018], eds. L. Grünewald-Schukalla, M. Lücke, M. Rauch, and C. Winter (New York, NY: Springer), 195–211. doi: 10.1007/978-3-658-23773-8_10

Sujan, M. (1985). Consumer knowledge: effects on evaluation strategies mediating consumer judgments. J. Consum. Res. 12, 31–46. doi: 10.1086/209033

Thornton, C., and Burkhalter, J. (2015). Must be the music: examining the placement effects of character-brand association and brand prestige on consumer brand interest within the music video context. J. Promot. Manag. 21, 126–141. doi: 10.1080/10496491.2014.971212

Keywords: product placement, brand placement, music, persuasion knowledge, credibility, word-of-mouth (WOM), video

Citation: Schramm H and Kraft J (2024) Are product placements in music videos beneficial for the artists? The impact of artist–product fit on viewers' persuasion knowledge and perceived credibility of the artist. Front. Commun. 9:1396483. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2024.1396483

Received: 05 March 2024; Accepted: 18 July 2024;

Published: 05 September 2024.

Edited by:

Tereza Semerádová, Technical University of Liberec, CzechiaReviewed by:

Nicolas Ruth, University of Music and Performing Arts Munich, GermanyAndrzej Tadeusz Kawiak, Marie Curie-Sklodowska University, Poland

Copyright © 2024 Schramm and Kraft. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Holger Schramm, aG9sZ2VyLnNjaHJhbW1AdW5pLXd1ZXJ6YnVyZy5kZQ==

Holger Schramm

Holger Schramm Jana Kraft

Jana Kraft