- School of Communication, Ariel University, Ariel, Israel

Exploring the nexus between digital media and citizens’ exposure to diverse political views is imperative for understanding contemporary democratic engagement. This study builds upon Mutz and Martin’s (2001) seminal research, integrating digital communication channels previously unexamined. Our findings suggest that the interpersonal character of media interactions, rather than the mere distinction between offline and online platforms, significantly influences the diversity of political views to which individuals are exposed. Contrary to the prevalent theories of “echo chambers” and “filter bubbles,” our analysis reveals a nuanced media landscape where digital platforms facilitate both homogeneous and heterogeneous political exposures, depending on their specific affordances. This study contributes to the political communication literature by offering a comprehensive overview of exposure dynamics in the digital age.

Introduction

Exposure to diverse political views is fundamental to the functioning of democratic systems, fostering the exchange of heterogeneous ideas within public discourse and facilitating political participation. Such participation is integral to democratic societies, as citizens engage in processes that inform collective political decisions impacting their lives (Jun, 2014). Exposure to different opinions can lead to decreased levels of polarization (Levendusky and Stecula, 2021) and partisan divide (Levendusky, 2023). Exposure to diverse political views is necessary for citizens to form opinions while also considering the opinions and perspectives of others. Diverse opinions often strengthen people’s sense of legitimacy regarding their own opinions after receiving a broad perspective (Mutz and Martin, 2001).

Many studies have examined the level of exposure to diverse political views through specific media or platforms (e.g., Wojcieszak and Mutz, 2009; Kim, 2011; Guidetti et al., 2016; Cowan and Baldassarri, 2018; González-Bailón et al., 2023; Nyhan et al., 2023), or compared the frequency or extent of encountering diverse political views between some media (e.g., Baek et al., 2012; Anspach, 2017). However, to the best of our knowledge, a systematic, comprehensive comparison of perceived exposure to diverse political views across the range of sources of political information, including mass, personal, offline, and online media channels, has not been conducted.

This study is a follow-up to Mutz and Martin (2001), who examined the degree of exposure to diverse political views in various media that constitute key sources of political information. The aim of Mutz and Martin’s research was to examine the contribution of sources of political information to exposure to diverse political views, and to compare the degree of exposure to diverse views between interpersonal media and the mass media (Mutz and Martin, 2001).

The study was published in 2001 and was based on data collected in 1995; therefore, over two decades have passed since the data were collected, during which many changes took place in the communication landscape, such as the rise of the internet and the age of online social media, which has gained momentum in the last decade. Mutz and Martin found that different media lead to different degrees of exposure to diverse political opinions. Therefore, we saw a need to re-examine the question while updating existing sources of information that serve as a central source of political information for citizens.

The aim of this study is to investigate diversity in the current political media landscape using Israel as a case study, bearing in mind the importance of exposure to diverse opinions as an essential part of a healthy, functioning democracy (Jun, 2014).

Literature review

Selective exposure and the importance of exposure to diverse opinions

Diversity of opinions is an important precondition for making informed decisions (Wurff, 2011). Studies show that there is a positive effect of exposure to diverse political views because it expands citizens’ political knowledge, contributes to more complex, sophisticated opinion formation, and increases political efficacy (Guidetti et al., 2016; Harell et al., 2019). Exposure to diverse political views is critical in a democracy because when citizens are exposed to opinions that differ from their own, they develop understanding, tolerance, and critical thinking (Author; Min and Wohn, 2018).

Despite the importance of exposure to diverse opinions, people seek harmonious relationships with others; therefore, when two or more people hold common beliefs, they tend to connect with each other (Echterhoff et al., 2009). Seeking information from other like-minded people can provide the basic need for connection, so most people tend to gather around opinions similar to their own, to examine, interpret, and remember information that confirms their existing opinions in advance. In contrast, relationships characterized by conflicting beliefs and opinions can undermine this basic need (Frimer et al., 2017), create cognitive dissonance that conflicts with existing beliefs or opinions, and cause feelings of personal discomfort (Festinger, 1957).

When people consume media content, they tend to consume content that is consistent with their existing positions. As early as the 1940s, Lazarsfeld et al. (1944) identified that people selectively remember certain political media messages while avoiding others, and that there is a connection between people’s opinions and their choices of what to listen to, watch, or read. The Selective Exposure theory examines how useful information is for citizens in forming an opinion (Knobloch-Westerwick and Kleinman, 2012; Wagner, 2016). Many people are selectively exposed for convenience – it is easier to be exposed to people with similar views. In this regard, selective exposure is a form of self-defence against a sense of threat (Hart et al., 2009).

In the case of online social media, people are also accidentally exposed to political information that they did not necessarily actively seek, including different political opinions or challenges to existing political positions. This incidental exposure may also be a critical factor in reducing gaps in political involvement, as even people with low political involvement often participate in political discussions online, such as sharing political information (Weeks et al., 2017). Still, a computational study of the news consumption patterns of 14 million Facebook users across 5 years found that users, independent of the activity or the time they spend online, persistently tend to interact with a very limited number of news outlets with which they identify (Cinelli et al., 2020; see also González-Bailón et al., 2023; Nyhan et al., 2023).

Although people do not actively avoid online information they disagree with, the Internet allows users to easily search for and consume political news with similar views to theirs, and this selective exposure may occur more frequently when people strongly identify with a particular political party (Weeks et al., 2017; Tyler et al., 2022). For example, a recent study found that supporters of conspiracy theories about COVID-19 were more likely to selectively choose and consume conservative media (which often supported conspiratorial claims), and that conservative media use positively correlated with beliefs in COVID-19 conspiracies (Romer and Jamieson, 2021). Similarly, participants who have a negative attitude towards vaccination tended to consume and recall more accurately attitude-consistent information (Li et al., 2022).

Exposure to diverse views in the mass media

This study is a follow-up to the classic study by Mutz and Martin (2001) and replicates the original research method while updating the sources of political information included in the original study. Their study compared different interpersonal and mass media, and examined whether and to what extent these media expose those who consume them to different and diverse political opinions. The study was based on two representative national surveys conducted in the United States and in the United Kingdom (Mutz and Martin, 2001).

In both countries, it was found that exposure to opinions through interpersonal interaction is often homogeneous and that there is room for selection in interpersonal communication. Most people tend to avoid talking about political issues with people who hold contradicting opinions, and moreover, people deliberately choose those with whom they are comfortable connecting and with whom they feel comfortable having a political discussion. These patterns cause people to not encounter disagreements, and even when they encounter them, they tend to avoid confrontation.

The second finding from Mutz and Martin’s study is that mass media, led by newspapers and television news, are the main sources through which people are exposed to different opinions. Television is a major source of exposure to heterogeneous views. Television programs, especially current affairs and news programs, are committed to journalistic ethics – objective reporting and the presentation of a variety of opinions and responses (Bennett and Serrin, 2005). A recent study also showed that respondents who consume TV and radio news show less tendency for selective exposure to news items (Steppat et al., 2022). In addition to television, the researchers examined communication with acquaintances in the workplace as a source of exposure to heterogeneous views, and found that these connections were located midway between homogeneous interpersonal sources and heterogeneous mass media. The workplace has also been explored in Mutz and Mondak (2006) and similar follow-up studies (Jian and Jeffres, 2008; Yeoman, 2014).

Mutz and Martin’s research provided important and relevant information about the sources through which people are exposed to diverse political views; however, since the study was conducted more than 20 years ago, it did not include online sources. Due to the significant changes that the media environment has undergone in recent years, as will be detailed below, there is room to update the study and reexamine it today.

Recent studies demonstrate that online platforms and social media emerged as the second-largest sources of news consumption, while television maintained significant viewership, particularly in political coverage (Gottfried and Shearer, 2017; Newman et al., 2018; Yanatma, 2018). Notably, during the 2016 US presidential elections, television served as the primary source for news on election results (Gottfried and Shearer, 2017). However, there us a shift, with a decline in television news consumption and a corresponding rise in social media usage for news consumption. A recent report suggests that these two sources of news consumption now stand as nearly equal primary sources for news. Additionally, the report highlights that, despite evolving media landscapes, television anchors and presenters remain the most recognized journalists in many countries (Newman et al., 2022).

A study investigating media influences on political positions revealed nuanced effects based on viewing behaviors. Unlike commercial television, engaging with current affairs programs on public channels has been associated with positive outcomes such as enhanced cognition, increased efficiency, and higher voter turnout in elections (Aarts and Semetko, 2003).

Despite the decline in the consumption of printed newspapers, traditional print media continues to play a vital role in enriching and deepening knowledge on political, social, and general issues. Research indicates that printed newspapers are particularly effective in broadening the scope of both general and political topics, surpassing online newspapers in this regard. However, this efficacy is contingent upon readers’ interest in and reliance on information from printed sources (Waal and Schoenbach, 2008). Moreover, compared to online news platforms, which offer a plethora of headlines for users to select from, print newspapers encourage a more structured consumption of stories, potentially fostering a deeper engagement with the content (Pearson and Knobloch-Westerwick, 2018).

In recent years, politics has made its way into the realm of reality television. A study examining viewer reactions to the UK general election within the context of the reality show “Big Brother” revealed that the program successfully engaged young individuals who may otherwise feel excluded from traditional political processes. Remarkably, this engagement was achieved through the lens of pleasure rather than a sense of duty or inherent interest in politics (Coleman, 2006). Furthermore, reality shows often leverage diversity in casting to attract audiences, intentionally creating tensions and conflicts among participants from various backgrounds. This deliberate representation of diverse social groups on screen frequently leads to clashes of values, adding an additional layer of intrigue to the programming (Kushin and Yamamoto, 2010).

Exposure to diverse views through interpersonal communication

According to a 2016 survey, friends and family are important sources of news, but respondents rely more on institutionalized media. Respondents testified that they trust the information they receive from official news sources, as well as information from family and friends, although trust in news from family and friends was lower than from official sources (Mitchell, 2016).

In contrast, political dialogue with co-workers is less likely to occur. A study that examined the conditions under which people would talk and reveal their political views found that there was a higher chance that people would share their views with friends and family than with co-workers. Moreover, people avoid talking about their political views, specifically with people they disagree with, to avoid conflict. It produces an experience of highly homogeneous social contexts, in which only liberal or conservative views are heard (Cowan and Baldassarri, 2018). Nevertheless, Mutz’s follow-up study of co-workers found that the workplace provides the most comfortable social context to encourage people to engage in political discourse. Moreover, because political discourse at work involves a large number of people, exposure to diverse opinions is commonplace (Mutz and Mondak, 2006).

Exposure to diverse views online

Numerous studies have explored the expansive nature of the Internet, which enables significant exposure to diverse individuals and opinions by facilitating connections across different societies and even among individuals residing in adversarial countries. This exposure to varied perspectives is facilitated through Internet platforms that attract individuals with a wide array of viewpoints. Notably, non-political discussion groups, such as those centered around hobbies and sports, often draw participants with divergent political beliefs (Wojcieszak and Mutz, 2009; Munson and Resnick, 2021). However, some studies cast doubt on the Internet’s efficacy as a tool for fostering exposure to a broad range of views and facilitating discussions among individuals and groups with contrasting perspectives (Author). Despite the importance of exposure to differing viewpoints and engaging in discussions with individuals holding diverse beliefs, empirical evidence suggests that people tend to avoid such discussions in practice (Mutz, 2006).

However, it’s crucial to recognize that the Internet is not a monolithic entity; rather, it comprises diverse digital spaces with distinct characteristics. When analyzing news consumption and the spectrum of political positions within digital realms, it becomes imperative to differentiate between various types of online spaces. These include news websites, email applications, social media platforms, content aggregators, blogs, and more. Each of these digital environments offers unique features and dynamics that shape the ways in which information is disseminated, consumed, and interacted with by users. Therefore, understanding the nuances of these digital spaces is essential for comprehensively examining the landscape of online news consumption and political discourse.

A survey conducted in 2016 revealed that online news has surpassed print newspapers in popularity, ranking second only to television (Mitchell et al., 2016). Furthermore, another survey indicated that printed newspapers ranked lowest in terms of political news consumption, with only 36% of adults in the U.S. reporting that they learned about political campaigns from local or national print newspapers. Importantly, this survey specifically inquired about the printed versions of newspapers and did not include digital formats, suggesting a significant gap in understanding: nearly half of U.S. adults (48%) obtained political news from news websites or apps. This distinction is crucial, highlighting the evolving landscape of media consumption and the increasing prominence of online news as one of the top ten new forms of digital media. This trend underscores the rise of new media platforms in comparison to traditional media outlets (Gottfried et al., 2016).

In the current era dominated by social media, research indicates contrasting dynamics regarding the content encountered on these platforms. On one hand, studies suggest that the composition of our social network plays a pivotal role in shaping the content we encounter, a phenomenon known as “selective exposure” (Bakshy et al., 2015). This suggests that individuals are more likely to come across content that aligns with the viewpoints of their social circle. Conversely, there is a claim that individuals who utilize social media for news consumption seek out diverse opinions and actively desire exposure to viewpoints that differ from their own (Beam et al., 2018). This suggests a motivation for seeking out diverse perspectives and challenging one’s own beliefs within the realm of social media news consumption. These contrasting findings underscore the complexity of individuals’ interactions with social media platforms and their motivations for engaging with diverse content.

Online social media platforms have emerged as crucial sources of political information, particularly during election campaigns (Sobaci et al., 2016; Lin et al., 2017). A significant portion of US adults, approximately half, now obtain news from social media platforms at least occasionally (Forman-Katz and Matsa, 2022). These platforms possess the potential to expose citizens to a multitude of perspectives and diverse political information (Kim, 2011; Bakshy et al., 2015; Barberá et al., 2015), potentially surpassing the reach of traditional mass media outlets (Anspach, 2017). Moreover, the utilization of targeting and personalization practices allows political candidates to tailor their messages to specific audiences (Mohamed and Manan, 2020). Concurrently, users leverage social media platforms to disseminate messages from campaigns and political organizations, recognizing the accessibility of these platforms to a broad and diverse audience (Vendemia et al., 2019).

On social media platforms, individuals have the opportunity to engage in online discussions and express their political opinions, effectively simulating face-to-face deliberations on political matters. Through these interactions, other users can read and evaluate public sentiment on specific topics (Walther and Jang, 2012; Anspach, 2017), potentially reinforcing their own opinions (Metzger et al., 2010). The diverse range of political perspectives evident in social media responses plays a crucial role in fostering public deliberation (Price et al., 2002; Mutz, 2006; Fishkin, 2009).

There is a prevalent argument suggesting that social media has fundamentally transformed the landscape of news consumption, offering a platform for exposure to diverse and heterogeneous viewpoints, often emphasizing social values over political affiliations (Messing and Westwood, 2014). In the era of social media dominance, individuals find themselves more susceptible than ever to the influence of others’ opinions, as these platforms have become primary sources of information for many (Jahng, 2018). Moreover, research indicates a positive correlation between the frequency and extent of social media usage and the likelihood of incidental exposure to diverse political perspectives and information (Lu and Lee, 2019).

Facebook stands out as a prominent source of news consumption among various social media platforms, with approximately 36% of US adults reporting regular news consumption on the platform (Shearer and Mitchell, 2021). Research from 2018 indicates that individuals who use Facebook for news consumption often encounter opinions that challenge their existing worldview (Beam et al., 2018). However, contrasting findings exist, with another study suggesting that Facebook may expose users to a more limited range of news content. Nonetheless, this study also proposes that prolonged use of Facebook may reduce the necessity for acquiring up-to-date information from alternative platforms (Boukes, 2019).

WhatsApp serves as another significant social media tool, offering users a platform characterized by intimacy, convenience, privacy, and trust, distinct from other social media applications. Within this environment, users can engage in the sharing of news and political discussions among their close contacts (Cheng et al., 2023).

Limited research has been conducted on email as a source of political knowledge. A study from 2016 examining political news sources during the US election campaign revealed that mailing lists were the least utilized source, accounting for only 1% of political news consumption compared to other sources (Gottfried et al., 2016). This indicates a decline in the use of email for political discussions compared to an earlier study, which found that 14% of Internet users reported sending emails to discuss politics through mailing lists comprised of family, friends, or relatives (Rainie et al., 2005).

In conclusion, the contemporary media landscape has undergone significant transformation with the widespread adoption of social media platforms, altering the role and relevance of traditional media outlets. These shifts have brought about important changes in how individuals encounter, search for, and engage with news and political information. The proliferation of social media has diversified the sources of information available to the public and facilitated broader participation in political discourse.

Challenges of democratizing information: navigating misinformation, polarization, and inequality in the digital age

The democratization of online information poses significant challenges, notably due to the absence of supervision and regulation, leading to concerns over the proliferation of misinformation, biases, misperceptions, and incitement. Furthermore, mere access to information does not necessarily guarantee the advancement of a stable and desired democratic model. In recent years, democratic systems in Western capitalist countries have experienced profound transformations. Political parties have drifted apart from the populace and “the people” (Mair, 2023), while political structures tend to represent specific societal layers, excluding marginalized groups and perpetuating inequality (Fraser, 2014). Concurrently, democracy’s substance has been hollowed out, replaced by authoritarian power structures under the guise of ostensibly democratic “rule of law” mechanisms (Slobodian, 2023). Scholars often attribute these concerning trends to the ascendance of social media. Disinformation campaigns undermine political discourse’s quality and erode trust in democratic institutions (Hunter, 2023). Echo chambers, where users predominantly encounter viewpoints aligning with their own, foster political polarization as individuals entrench in their beliefs, disinclined to engage with dissenting perspectives (Barberá, 2020). While exposure to diverse political views is imperative, it alone is insufficient to bolster robust, representative democracy. Understanding these dynamics is essential for navigating the complexities of the contemporary media landscape and fostering informed civic engagement in an increasingly digital era.

A note about the definition and boundaries of political diversity

When discussing media diversity, it’s crucial to acknowledge its inherently political character, as extensively examined by sociologists and political scientists. Pierre Bourdieu’s insights offer a critical perspective on media diversity, framing it within the dynamics of symbolic power and authority. He emphasizes the interplay between power dynamics and communication, highlighting how media production is influenced by symbolic power, shaping both audience reception and media practice (Park, 2010). Bourdieu underscores the impact of political and economic forces on media, delineating its boundaries. Media diversity, as valued within market constraints, often perpetuates symbolic violence by sensationalizing and portraying “the other” within predetermined boundaries that do not challenge existing political structures (Marlière, 1998).

Moreover, the complexities of media markets challenge the assumption that solely catering to audience preferences benefits society. This tension between meeting audience expectations and upholding broader societal standards is evident globally. In Israel, critiques of media diversity reveal underrepresentation and stereotypical portrayals of minorities such as Israeli Arabs and Ultra-Orthodox Jews, perpetuating marginalization (Laor and Galily, 2022; Schejter et al., 2023).

Regarding political perspectives, mainstream media has historically leaned leftward, but recent shifts in the political landscape and government policies aimed at amplifying right-wing voices have led to increased representation of conservative opinions in television and print media (Shwartz Altshuler, 2014). This trend aligns closely with Bourdieu’s assertions, highlighting the intricate relationship between media representation and political power dynamics.

Novelty of the study

Mutz and Martin (2001) examined the extent to which sources of political information expose people to different political views. They included the following media in their research: the three people with whom respondents talked the most about politics, voluntary organizations, “Talk Show” programs, workplace acquaintances, newspapers, TV news, and magazines. This study followed the same methodology as the original study and revisited the same question. However, in light of the changes in the current political media landscape, we updated the sources under investigation, mainly adding relevant digital communication venues where political discussions occur, such as WhatsApp, Facebook (distinguishing between general feed and direct communication with Facebook friends with whom respondents talk about politics), e-mail, news websites, and reality TV shows.

As reviewed above, many recent studies have addressed the issue of exposure to diverse opinions across media. However, to the best of our knowledge, no previous study has compared all sources of political information in contemporary media in terms of the diversity of political views. Therefore, it is important to revisit the comprehensive 2001 research by Mutz and Martin to answer this question, as it is expressed in today’s field of communication.

We investigated the diversity of opinions within Israeli media as perceived by media consumers. Israel operates as a parliamentary democracy, where the Prime Minister leads a multi-party coalition government. Despite certain limitations in its balancing mechanisms—such as national elections and a single house of representatives—the country maintains a separation of powers, encompassing executive, legislative, and judicial branches (The Israeli Political System, n.d.).

Regarding media regulation, Israel employs a complex framework of laws and regulatory bodies. In contrast to centralized authorities like the UK’s OFCOM and France’s CSA, Israel’s media regulation system is more decentralized. While the print and online press operate without direct regulation, they are subject to various ad hoc regulations outlined in the penal and civil codes (Israel, n.d.). Furthermore, Israel’s media landscape is characterized by greater diversity and complexity, featuring a multitude of media outlets and a heightened level of political polarization.

Research hypotheses

Sources of political information and exposure to diverse political views

H1: In line with Mutz and Martin (2001), the degree of exposure to diverse political views varies among sources of political information. Political information originating from interpersonal relationships with friends and close acquaintances is characterized by the most homogeneous exposure (similar views), whereas political information originating from the mass media is characterized by the most heterogeneous exposure (diverse political views).

H2: Differences will be found between online sources of political information, such that interpersonal sources of information will be characterized by more homogeneous exposure, and mass sources of information will be characterized by heterogeneous exposure to political opinions (Mitchell, 2016).

Methodology

An online survey was conducted among adult internet users in Israel. The survey was distributed by a leading Israeli online panel service.1

Our methodology employs self-reported measures to investigate participants’ exposure to diverse political views across various media. This approach was intentionally chosen due to the inherent limitations of digital data scraping in capturing the nuances of offline interactions and the subjective nature of media perception. Self-reports enable the examination of individuals’ perceptions, offering insights into the perceived diversity of political discourse they encounter. This method acknowledges the complexity of measuring exposure in both digital and non-digital environments and prioritizes the subjective experience of media consumers, aligning with our study’s focus on perceived, rather than objective, exposure to political diversity.

While acknowledging existing literature that points to potential inaccuracies in individuals’ perceptions of their social circles’ political views (c.f. Levendusky and Malhotra, 2016), our study minimizes this concern by focusing on respondents’ evaluations of political discussions with specific individuals. By concentrating on dialogues about political matters, we argue that our respondents provide more accurate assessments of the political diversity they are exposed to, compared to their assessment of the political diversity of their broader social network.

Participants

In total, 514 respondents, 51% of whom were male, ages 18–70 (M = 40.72, SD = 14.55), participated in the survey, which repeated the methodology used by Mutz and Martin (2001) as much as possible. 49% of the respondents considered themselves right-wingers (right or very right), 31% centrist, and 20% left-wingers (left or very left).

Questionnaire

Digital sources of information that did not exist in Mutz and Martin’s study were added to the survey, and the types of television programs in which political positions are heard were also updated. To characterize the main sources of information for media consumers today, a pilot study was conducted among students, in which the respondents were asked to indicate all the sources of political information to which they were exposed. Ultimately, 12 information channels were selected for the survey.

1. The person the respondent talks to the most about politics (closest person)

2. Apart from this person, the person the respondent talks to the most about politics (second closest person)

3. Acquaintances from the current/last workplace

4. Print newspaper

5. Television news programs

6. Current affairs programs on television

7. Television reality shows

8. News content websites

9. WhatsApp

10. Email

11. Facebook Feed

12. Facebook friend the respondent talks to the most about politics (on Facebook).

Except for the first three sources, which constitute daily interpersonal relationships, for each of the other sources of information, the respondents were asked about their exposure to political information during the week prior to the survey.

Instead of “Talk Show” programs, a very popular genre in the United States that was included in the original study, we chose to review reality shows, a popular genre among Israelis with high ratings (Tucker, 2015).

In questions concerning mass media – newspapers, news content sites, and television – respondents were asked about what information channels they use (choosing from the leading channels, e.g., major newspapers and major TV channels, with the option to mark “other” and indicate the name of a channel not mentioned in the list). If the respondents stated that they do not use any communication channel, questions regarding this channel were not presented to them.

In the second part of the questionnaire, each of the information sources indicated by respondents were presented with three questions related to the political information they were exposed to through that channel:

1. To what extent is their political view similar or different from the political view expressed by the source of the information or the view to which they were exposed through the source of the information?

2. The extent to which their political preferences are similar or different from the political preferences of the source of information, or the preferences to which they have been exposed through the source of information.

3. The extent to which their opinions on issues on the agenda are similar or different from the opinions of the source of information, or the opinions to which they have been exposed through the source of information.

The answers to each of these questions, for each of the relevant sources, were on a 5-point scale, with points 1–2 denoting very different or different positions, point 3 denoting equally similar and different, and points 4–5 signifying similar and very similar positions.

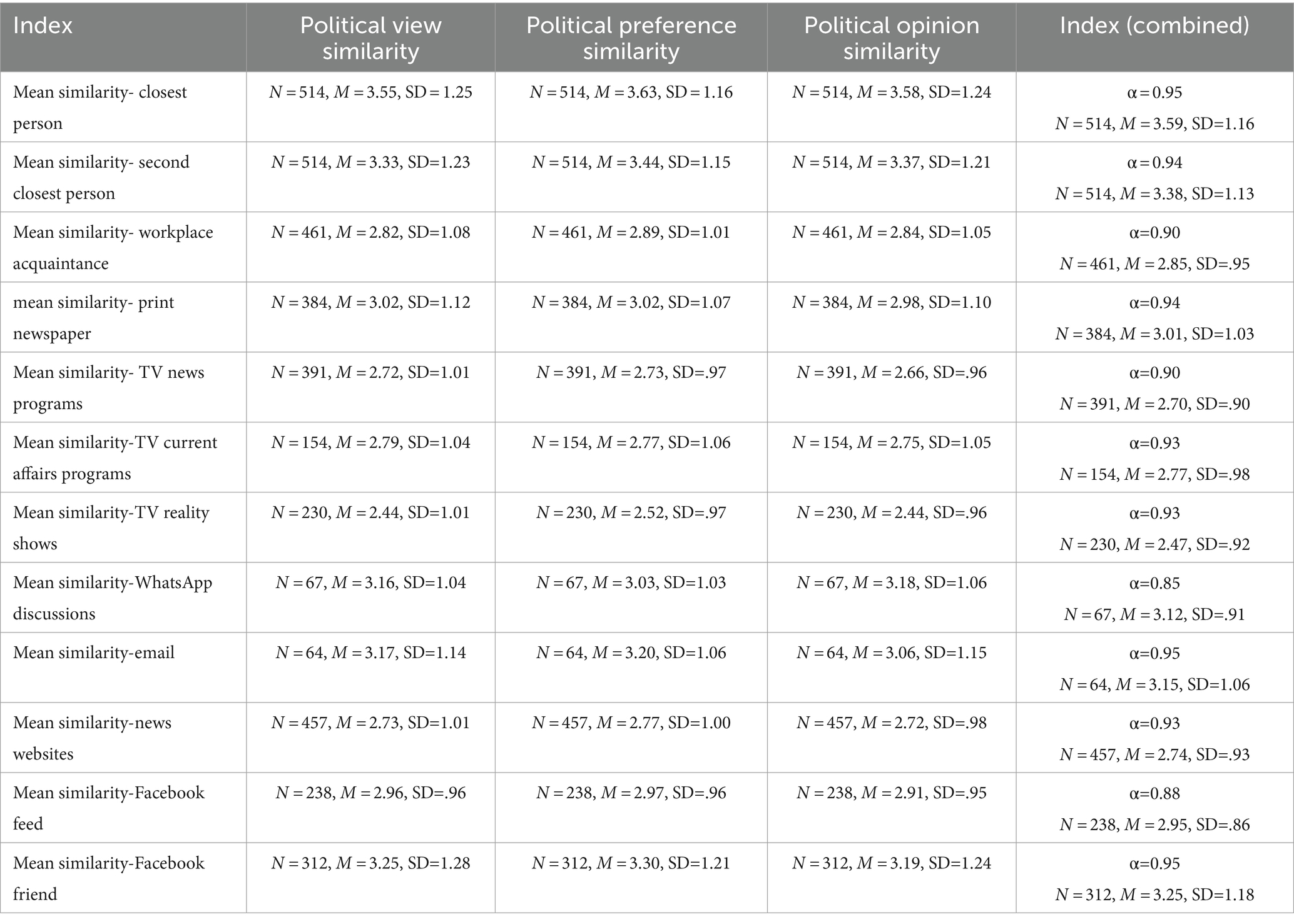

For each of the sources of information, a “mean of similarity” index was compiled which consisted of the mean of these three questions, the reliability of which was extremely high in each case. Table 1 summarizes the means of the variables and scales. It should be noted that the numbers (N) for each source of information pertain to the number of respondents who testified that they were exposed to political information through the source of the information, and do not indicate the extent to which one or another source of media information is used.

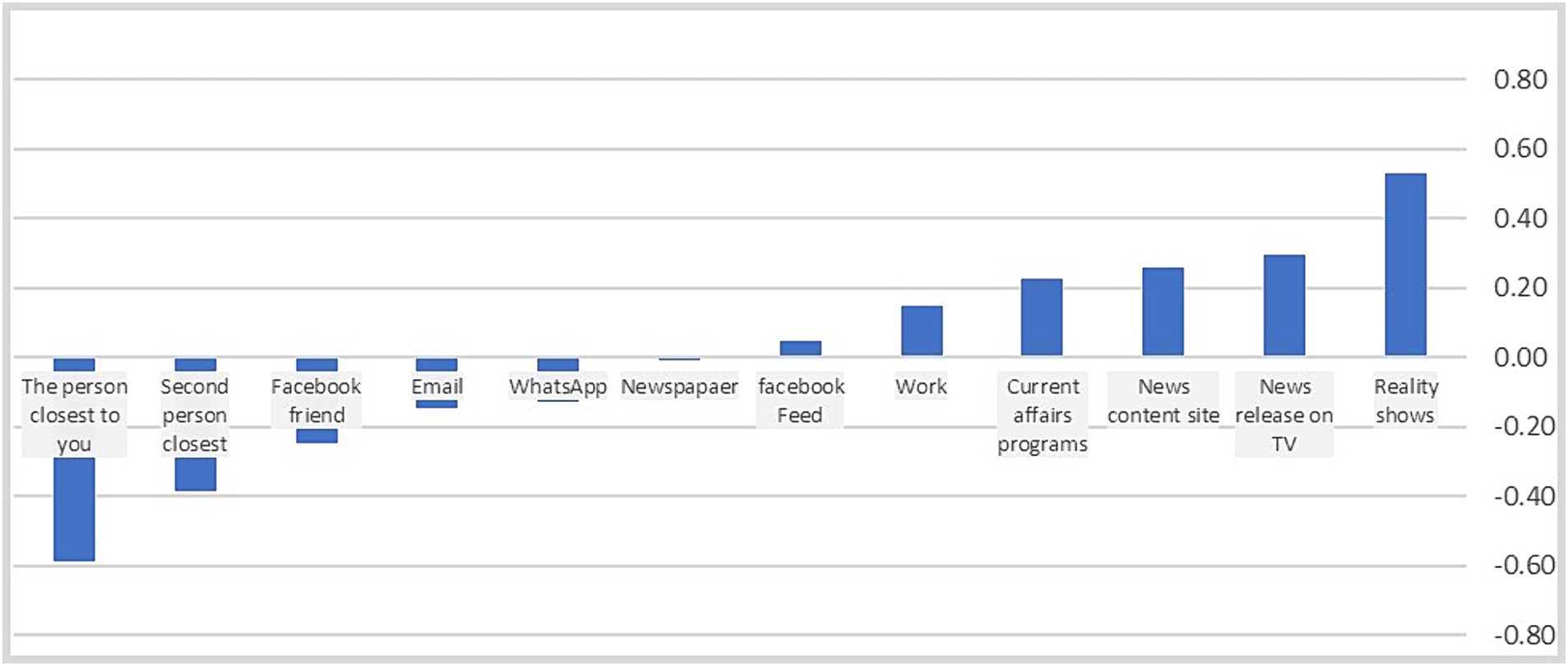

Table 1. Mean similarity indices and average scores for the indices and for the items composing them.

Results

Sources of political information and exposure to diverse political views

Figure 1 shows the exposure indices for diverse opinions, on the axis between the most homogeneous exposure and the most heterogeneous exposure relative to the average of all indices. The “zero” point in the graph is the average of all sources, that is, neither homogeneous nor heterogeneous. The indices below this point are more homogeneous, and the indices above it are more heterogeneous.

The findings demonstrate that information sources can be roughly divided into three groups in terms of heterogeneous exposure to political opinions. In the first, most homogeneous group, we find the interpersonal sources of information: the closest person, the second closest person, and a Facebook friend with whom the respondents talk about politics. The middle group mainly includes sources of information that are not mass but less interpersonal: email, WhatsApp, Facebook Feed, and workplace acquaintances. Newspapers also fall into this category, perhaps due to the existence of politically identifiable newspapers, as well as the practice of consuming information in newspapers that allows for a relatively high degree of selective exposure.

The group featuring the most heterogeneous political information sources includes television programs and news websites. It is interesting to note here that, of all the sources of information, it was the reality shows that respondents think exposed them to the most diverse political views.

These results confirm H1: Interpersonal relationships are the most homogeneous sources of political information and views, whereas mass media are the most heterogeneous.

H2 was also confirmed. It is apparent that digital information sources are not unified. These were divided according to the type of connection/communication. Computer-mediated interpersonal communication (e.g., Facebook friends) is more homogeneous and similar to interpersonal communication in general. Content websites, however, are more heterogeneous, similar to mass media.

Respondents were also asked about their frequency of exposure to political information from various sources. Three questions were posed for this purpose: each time the respondents were asked about the source through which they were most exposed to political information of all sources of information. Once they made their choice, they were presented with the sources of information in the next question, without the already selected source. This way the study mapped the three most frequent sources of political information, in order of frequency, per respondent.

The analysis revealed that the most common source of exposure to political information by most people is the closest person, who was indicated in the three questions by 308 respondents, followed by the second closest person, which was indicated by 204 respondents. Then, TV news, chosen by 242 respondents and content websites were chosen by 227 respondents.

It is interesting to note that these are two types of sources positioned at the opposite end points of the diverse views graph. Interpersonal relationships – the first person and the second person – are characterized by exposure to the most homogeneous opinions and, on the other hand, news on television and content websites that respondents perceive as the most heterogeneous political sources.

Discussion and conclusions

The dynamic and rapidly evolving nature of the media landscape necessitates periodic revisitation and validation of previous research findings, particularly when comparing media in relation to their social applications or implications. In our study, we revisited the research conducted by Mutz and Martin (2001) with several updates and modifications to reflect the present-day media landscape. This involved incorporating additional and diverse means of communication not considered in the original study, such as TV reality shows and various online sources. Simultaneously, we excluded less relevant sources included in the original study, such as talk shows that hold lesser popularity in certain regions like Israel.

These adjustments were made to align the study with the current media environment and to reassess which sources of political information provide media consumers with the most heterogeneous political views. While the findings of our study largely mirrored those of the original research, several new insights emerged. This underscores the importance of continuously adapting research methodologies to account for the dynamic nature of media consumption patterns and technological advancements.

Consistent with the findings of the original study, our research reaffirmed that television programs remain significant sources of heterogeneous political information, exposing media consumers to a variety of political views. Television news programs, in particular, emerged as the second most heterogeneous source of political information in both studies. Additionally, workplace acquaintances were identified as heterogeneous sources of political information, ranking closely behind television in terms of diversity.

Furthermore, akin to the original study, our research revealed that interpersonal relationships heavily influence political discourse. We found that individuals tend to engage in political discussions with those who share similar political views, resulting in homogeneous political interactions. This consistency underscores the enduring influence of personal networks on shaping individuals’ political beliefs and the limited exposure to diverse viewpoints within these social circles.

Unlike the original study, which identified print newspapers as the most heterogeneous source of political information, our findings suggest that newspapers now fall between interpersonal relationships and television in terms of diversity. This shift may reflect changes in the print industry, with newspapers increasingly aligning themselves with specific political ideologies, thereby attracting readers who share those views (Hart et al., 2009).

Regarding the sources added in our study, we observed variations in the degree of exposure to diverse opinions. Reality shows emerged as the most heterogeneous source, followed by TV news programs, news websites, and current affairs programs. In contrast, WhatsApp and email exhibited more homogeneous exposure. Notably, Facebook friends and offline interpersonal relationships were among the most homogeneous sources, aligning with the theory of selective exposure (Lazarsfeld et al., 1944) and individuals’ tendency to engage with like-minded individuals.

We can categorize sources of political information into three groups based on their heterogeneous exposure to political opinions. The first group consists of the most homogeneous sources, primarily interpersonal relationships. The middle group includes less mass sources such as email, WhatsApp, and newspapers, which have become more politically identified in recent years. The most heterogeneous group comprises mass media sources like television programs and news websites, providing diverse political views.

Interestingly, respondents perceived reality shows as the source exposing them to the most diverse political views. This may be attributed to the format of reality shows, which integrates individuals from diverse backgrounds and social groups, fostering conflicts and generating diverse perspectives for entertainment purposes. Here, one might question whether the exposure to diverse political views provided by reality TV, which often showcases extravagant individuals in extreme conditions, genuinely serves the goal of fostering understanding, tolerance, and critical thinking—qualities essential for sustaining a vibrant public sphere in a democracy.

Habermas distinguishes between public opinion and public mood by underscoring that public opinion involves the expression of beliefs and sentiments within a citizenry regarding human affairs. It emerges from critical-rational discourse, where citizens engage in reasoned debate and discussion to form collective opinions on political issues—an ideal manifestation of the public sphere. Conversely, public mood denotes the collective emotional state of a group, capable of influencing thoughts and actions, reflecting shared experiences. Public moods are reactive and lack inherent rationality. While public opinion is shaped by stable and consistent aggregate-level views over time, public mood is more dynamic, uncertain, and diverse. Habermas perceives the transition from public opinion to public mood as a troubling modern development, as it undermines the critical-rational deliberation central to his ideal public sphere.

The media, particularly the widespread commercialization of news and the proliferation of advertising and manipulation techniques, play a pivotal role in shaping and amplifying public moods rather than facilitating public opinion (Calhoun, 1993; Habermas, 2012; Gerbaudo, 2022). Indeed, the often sensational portrayal of social groups may evoke moods rather than encourage opinion formation or challenge existing beliefs. Nevertheless, even within the constraints of ratings and provocation, some viewers—particularly younger audiences—encounter diverse social groups, opinions, and cultures through these media contents, serving as their initial exposure. Furthermore, such content sparks political discussions among young, less politically involved citizens, who may not have otherwise engaged with such topics (Coleman, 2006; Graham and Hajru, 2011).

Furthermore, our study reaffirmed the importance of interpersonal interactions as the primary source of exposure to political information, followed by television news programs and news websites. This aligns with previous research emphasizing the significance of interpersonal communication and mass media in shaping political exposure (Gottfried and Shearer, 2017; Newman et al., 2018, 2022; Yanatma, 2018).

In conclusion, our study advances our understanding of the role of digital media in facilitating exposure to diverse political views, challenging the dichotomy of online versus offline media influence. By highlighting the critical role of interpersonal interactions alongside digital platforms, our findings underscore the complexity of political exposure in the digital age. Future research should continue to explore the evolving nature of digital platforms and their impact on political discourse, considering rapid technological advancements and their implications for democratic engagement. An examination of how citizens in other democracies perceive the diversity of opinions across media and platforms would be invaluable, enabling profound comparative insights into the nature of different media sources in various democratic systems and how they are perceived by media consumers.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

NS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AL-o: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

References

Aarts, K., and Semetko, H. A. (2003). The divided electorate: media use and political involvement. J. Polit. 65, 759–784. doi: 10.1111/1468-2508.00211

Anspach, N. M. (2017). The new personal influence: how our Facebook friends influence the news we read. Polit. Commun. 34, 590–606. doi: 10.1080/10584609.2017.1316329

Baek, Y. M., Wojcieszak, M., and Delli Carpini, M. X. (2012). Online versus face-to-face deliberation: who? Why? What? With what effects? New Media Soc. 14, 363–383. doi: 10.1177/1461444811413191

Bakshy, E., Messing, S., and Adamic, L. A. (2015). Exposure to ideologically diverse news and opinion on Facebook. Science 348, 1130–1132. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa1160

Barberá, P. (2020). “Social media, echo chambers, and political polarization” in Social media and democracy. eds. N. Persily and J. A. Tucker (Cambridge, USA: Cambridge University Press), 34–55.

Barberá, P., Jost, J. T., Nagler, J., Tucker, J. A., and Bonneau, R. (2015). Tweeting from left to right. Psychol. Sci. 26, 1531–1542. doi: 10.1177/0956797615594620

Beam, M. A., Hutchens, M. J., and Hmielowski, J. D. (2018). Facebook news and (de) polarization: reinforcing spirals in the 2016 US election. Inf. Commun. Soc. 21, 940–958. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2018.1444783

Boukes, M. (2019). Social network sites and acquiring current affairs knowledge: the impact of twitter and Facebook usage on learning about the news. J. Inform. Tech. Polit. 16, 36–51. doi: 10.1080/19331681.2019.1572568

Cheng, Z., Zhang, B., and Gil de Zúñiga, H. (2023). Antecedents of political consumerism: modeling online, social media and Whats app news use effects through political expression and political discussion. Int. J. Press Polit. 28:194016122210759. doi: 10.1177/19401612221075936

Cinelli, M., Brugnoli, E., Schmidt, A. L., Zollo, F., Quattrociocchi, W., and Scala, A. (2020). Selective exposure shapes the Facebook news diet. PLoS One 15:229129. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0229129

Coleman, J. A. (2006). English-medium teaching in European higher education. Lang. Teach. 39, 1–14. doi: 10.1017/S026144480600320X

Cowan, S. K., and Baldassarri, D. (2018). “It could turn ugly”: selective disclosure of attitudes in political discussion networks. Soc. Networks 52, 1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.socnet.2017.04.002

Echterhoff, G., Higgins, E. T., and Levine, J. M. (2009). Shared reality: experiencing commonality with others’ inner states about the world. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 4, 496–521. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2009.01161.x

Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Redwood City, USA: Stanford University Press, vol. 2.

Fishkin, J. S. (2009). Virtual public consultation: Prospects for internet deliberative democracy. Eds. Davies, T and Gangadharan, S.P. Online Deliberation: Design, Research, and Practice, 23–35.

Forman-Katz, N., and Matsa, K. (2022). News platform fact sheet Pew Research Center’s Journalism Project Available at: https://www.pewresearch.org/journalism/fact-sheet/news-platform-fact-sheet/.

Fraser, N. (2014). “Rethinking the public sphere: a contribution to the critique of actually existing democracy” in Between borders. eds. H. A. Giroux and P. McLaren (London, UK: Routledge), 74–98.

Frimer, J. A., Skitka, L. J., and Motyl, M. (2017). Liberals and conservatives are similarly motivated to avoid exposure to one another’s opinions. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 72, 1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2017.04.003

Gerbaudo, P. (2022). Theorizing reactive democracy: the social media public sphere, online crowds, and the plebiscitary logic of online reactions. Democr. Theory 9, 120–138. doi: 10.3167/dt.2022.090207

González-Bailón, S., Lazer, D., Barberá, P., Zhang, M., Allcott, H., Brown, T., et al. (2023). Asymmetric ideological segregation in exposure to political news on Facebook. Science 381, 392–398. doi: 10.1126/science.ade7138

Gottfried, J., Barthel, M., Shearer, E., and Mitchell, A. (2016). The 2016 presidential campaign – A news event That’s hard to miss. Washington, D.C, USA: Pew Research Center.

Gottfried, J., and Shearer, E. (2017). Americans’ online news use is closing in on TV news use.Washington, D.C, USA: Pew Research Center.

Graham, T., and Hajru, A. (2011). Reality TV as a trigger of everyday political talk in the net-based public sphere. Eur. J. Commun. 26, 18–32. doi: 10.1177/0267323110394858

Guidetti, M., Cavazza, N., and Graziani, A. R. (2016). Perceived disagreement and heterogeneity in social networks: distinct effects on political participation. J. Soc. Psychol. 156, 222–242. doi: 10.1080/00224545.2015.1095707

Harell, A., Stolle, D., and Quintelier, E. (2019). Experiencing political diversity: the mobilizing effect among youth. Acta Politica 54, 684–712. doi: 10.1057/ap.2016.2

Hart, W., Albarracín, D., Eagly, A. H., Brechan, I., Lindberg, M. J., and Merrill, L. (2009). Feeling valiyeard versus being correct: a meta-analysis of selective exposure to information. Psychol. Bull. 135, 555–588. doi: 10.1037/a0015701

Hunter, L. Y. (2023). Social media, disinformation, and democracy: how different types of social media usage affect democracy cross-nationally. Democratization 30, 1040–1072. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2023.2208355

Israel. (n.d.) Center for media, data and society. Available at: https://cmds.ceu.edu/israel (Accessed April 7, 2024).

Jahng, M. R. (2018). From reading comments to seeking news: exposure to disagreements from online comments and the need for opinion-challenging news. J. Inform. Tech. Polit. 15, 142–154. doi: 10.1080/19331681.2018.1449702

Jian, G., and Jeffres, L. (2008). Spanning the boundaries of work: workplace participation, political efficacy, and political involvement. Commun. Stud. 59, 35–50. doi: 10.1080/10510970701849370

Jun, N. (2014). Political diversity and participation: a systematic review of the measurement and relationship. Asian J. Public Opin. Res. 1, 103–127. doi: 10.15206/ajpor.2014.1.2.103

Kim, Y. (2011). The contribution of social network sites to exposure to political difference: the relationships among SNSs, online political messaging, and exposure to cross-cutting perspectives. Comput. Hum. Behav. 27, 971–977. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2010.12.001

Knobloch-Westerwick, S., and Kleinman, S. B. (2012). Preelection selective exposure: confirmation bias versus informational utility. Commun. Res. 39, 170–193. doi: 10.1177/0093650211400597

Kushin, M. J., and Yamamoto, M. (2010). Did social media really matter? College students’ use of online media and political decision making in the 2008 election. Mass Commun. Soc. 13, 608–630. doi: 10.1080/15205436.2010.516863

Laor, T., and Galily, Y. (2022). Ultra-orthodox representations in Israeli radio satire. Israel Aff. 28, 271–296. doi: 10.1080/13537121.2022.2041827

Lazarsfeld, P. F., Berelson, B., and Gaudet, H. (1944). The people’s choice. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Levendusky, M. (2023). Our common bonds: Using what Americans share to help bridge the partisan divide. Chicago, USA: University of Chicago Press.

Levendusky, M. S., and Malhotra, N. (2016). (Mis) perceptions of partisan polarization in the American public. Public Opin. Q. 80, 378–391. doi: 10.1093/poq/nfv045

Levendusky, M. S., and Stecula, D. A. (2021). We need to talk: How cross-party dialogue reduces affective polarization. Cambridge, USA: Cambridge University Press.

Li, K., Li, Y., and Zhang, P. (2022). Selective exposure to COVID-19 vaccination information: the influence of prior attitude, perceived threat level and information limit. Libr. Hi Tech 40, 323–339. doi: 10.1108/LHT-03-2021-0117

Lin, Y. H., Hsu, C. L., Chen, M. F., and Fang, C. H. (2017). New gratifications for social word-of-mouth spread via mobile SNSs: uses and gratifications approach with a perspective of media technology. Telematics Inform. 34, 382–397. doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2016.08.019

Lu, Y., and Lee, J. K. (2019). Stumbling upon the other side: incidental learning of counter-attitudinal political information on Facebook. New Media Soc. 21, 248–265. doi: 10.1177/1461444818793421

Marlière, P. (1998). The rules of the journalistic field: Pierre Bourdieu’s contribution to the sociology of the media. Eur. J. Commun. 13, 219–234. doi: 10.1177/0267323198013002004

Messing, S., and Westwood, S. J. (2014). Selective exposure in the age of social media: endorsements trump partisan source affiliation when selecting news online. Commun. Res. 41, 1042–1063. doi: 10.1177/0093650212466406

Metzger, M. J., Flanagin, A. J., and Medders, R. B. (2010). Social and heuristic approaches to credibility evaluation online. J. Commun. 60, 413–439. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2010.01488.x

Min, S. J., and Wohn, D. Y. (2018). All the news that you don’t like: cross-cutting exposure and political participation in the age of social media. Comput. Hum. Behav. 83, 24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2018.01.015

Mitchell, A. (2016). Key findings on the traits and habits of the modern news consumer, Washington, D.C, USA: Pew Research Center.

Mitchell, A., Gottfried, J., Barthel, M., and Shearer, E. (2016). Pathways to news. Washington, D.C, USA: Pew Research Center.

Mohamed, S., and Manan, K. A. (2020). Facebook and political communication: a study of online campaigning during the 14th Malaysian general election. IIUM J. Hum. Sci. 2, 1–13. doi: 10.31436/ijohs.v2i1.112

Munson, S., and Resnick, P. (2021). The prevalence of political discourse in non-political blogs. Proc. Int. AAAI Conf. Web Soc. Media 5, 233–240. doi: 10.1609/icwsm.v5i1.14133

Mutz, D. C. (2006). Hearing the other side: Deliberative versus participatory democracy. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Mutz, D. C., and Martin, P. S. (2001). Facilitating communication across lines of political difference: the role of mass media. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 95, 97–114. doi: 10.1017/S0003055401000223

Mutz, D. C., and Mondak, J. J. (2006). The workplace as a context for cross-cutting political discourse. J. Polit. 68, 140–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2508.2006.00376.x

Newman, N., Fletcher, R., Kalogeropoulos, A., Levy, D. A. L., and Nielsen, R. K. (2018). Reuters institute digital news report 2018 Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism Available at: https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/digital-news-report-2018.pdf.

Newman, N., Fletcher, R., Robertson, C. T., Eddy, K., and Nielsen, R. K. (2022). Reuters institute digital news report 2022 Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism Available at: https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2022-06/Digital_News-Report_2022.pdf.

Nyhan, B., Settle, J., Thorson, E., Wojcieszak, M., Barberá, P., Chen, A. Y., et al. (2023). Like-minded sources on Facebook are prevalent but not polarizing. Nature 620, 137–144. doi: 10.1038/s41586-023-06297-w

Park, D. W. (2010). Pierre Bourdieu: A critical introduction to media and communication theory. New York, United States of America: Peter Lang Verlag.

Pearson, G. D., and Knobloch-Westerwick, S. (2018). Perusing pages and skimming screens: exploring differing patterns of selective exposure to hard news and professional sources in online and print news. New Media Soc. 20, 3580–3596. doi: 10.1177/1461444818755565

Price, V., Cappella, J. N., and Nir, L. (2002). Does disagreement contribute to more deliberative opinion? Polit. Commun. 19, 95–112. doi: 10.1080/105846002317246506

Rainie, L., Cornfield, M., and Horrigan, J. (2005). The internet and campaign 2004. Washington D.C., USA: Pew Internet & American Life Project.

Romer, D., and Jamieson, K. H. (2021). Conspiratorial thinking, selective exposure to conservative media, and response to COVID-19 in the US. Soc. Sci. Med. 291:114480. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114480

Schejter, A. M., Shomron, B., Abu Jafar, M., Abu-Kaf, G., Mendels, J., Mola, S., et al. (2023). “Mass media: the case of Israeli broadcast media and Arab-Israelis” in Digital capabilities: ICT adoption in marginalized communities in Israel and the West Bank (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 39–58.

Shearer, E., and Mitchell, A. (2021). News use across social media platforms in 2020: Facebook stands out as a regular source of news for about a third of Americans Pew Research Center. Available at: https://www.pewresearch.org/journalism/2021/01/12/news-use-across-social-media-platforms-in-2020/.

Shwartz Altshuler, T. (2014). IDI: advocates of diversity and transparency in the media. The Israeli democracy institute op-ed. Available at: https://en.idi.org.il/articles/6444 (Accessed April 4, 2024).

Slobodian, Q. (2023). Crack-up capitalism: Market radicals and the dream of a world without democracy New-York, USA: Random House.

Sobaci, M. Z., Eryiğit, K. Y., and Hatipoğlu, İ. (2016). “The net effect of social media on election results: the case of twitter in 2014 Turkish local elections” in Social media and local governments. Public administration and information technology. ed. M. Sobaci (Berlin, Germany: Springer), 265–279.

Steppat, D., Castro Herrero, L., and Esser, F. (2022). Selective exposure in different political information environments–how media fragmentation and polarization shape congruent news use. Eur. J. Commun. 37, 82–102. doi: 10.1177/02673231211012141

The Israeli Political System. Schusterman center for Israel studies research guide. (n.d.). Available at: https://guides.library.brandeis.edu/c.php?g=1021060&p=7478457 (Accessed April 7, 2024).

Tucker, N. (2015). Half-year ratings summery. Available at: https://www.themarker.com/advertising/1.2670303.

Tyler, M., Grimmer, J., and Iyengar, S. (2022). Partisan enclaves and information bazaars: mapping selective exposure to online news. J. Polit. 84, 1057–1073. doi: 10.1086/716950

Vendemia, M. A., Bond, R. M., and DeAndrea, D. C. (2019). The strategic presentation of user comments affects how political messages are evaluated on social media sites: evidence for robust effects across party lines. Comput. Hum. Behav. 91, 279–289. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2018.10.007

Waal, E., and Schoenbach, K. (2008). Presentation style and beyond: how print newspapers and online news expand awareness of public affairs issues. Mass Commun. Soc. 11, 161–176. doi: 10.1080/15205430701668113

Walther, J. B., and Jang, J. W. (2012). Communication processes in participatory websites. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 18, 2–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1083-6101.2012.01592.x

Weeks, B. E., Lane, D. S., Kim, D. H., Lee, S. S., and Kwak, N. (2017). Incidental exposure, selective exposure, and political information sharing: integrating online exposure patterns and expression on social media. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 22, 363–379. doi: 10.1111/jcc4.12199

Wojcieszak, M. E., and Mutz, D. C. (2009). Online groups and political discourse: do online discussion spaces facilitate exposure to political disagreement? J. Commun. 59, 40–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2008.01403.x

Wurff, R. (2011). Do audiences receive diverse ideas from news media? Exposure to a variety of news media and personal characteristics as determinants of diversity as received. Eur. J. Commun. 26, 328–342. doi: 10.1177/0267323111423377

Yanatma, S. (2018). Reuters institute digital news report – Turkey supplementary report. Oxford, UK: University of Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

Keywords: political communication, political discourse, diverse political views, selective exposure, echo chambers, filter bubbles, online social media

Citation: Steinfeld N and Lev-on A (2024) Exposure to diverse political views in contemporary media environments. Front. Commun. 9:1384706. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2024.1384706

Edited by:

Pradeep Nair, Central University of Himachal Pradesh, IndiaReviewed by:

Kostas Maronitis, Leeds Trinity University, United KingdomAndrijana Rabrenovic, Radio Bijelo Polje, Montenegro

Copyright © 2024 Steinfeld and Lev-on. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Azi Lev-on, YXppbGV2b25AZ21haWwuY29t

†ORCID: Azi Lev-on, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0248-9802

Nili Steinfeld

Nili Steinfeld Azi Lev-on

Azi Lev-on