- 1Department of Political Science, Columbia University, New York, NY, United States

- 2BBC Media Action, Jakarta, Indonesia

- 3BBC Media Action, London, United Kingdom

- 4BBC Media Action, New Delhi, India

Drama has been shown to change attitudes and inspire action on topics as diverse as health, sanitation, intergroup conflict, and gender equality, but rarely have randomized trials assessed the influence of narrative entertainment programs focusing on climate change and environmental protection. We report the results of an experiment in which young Indonesian adults were sampled from five metropolitan areas. Participants were randomly assigned to watch a condensed two-hour version of a new award-winning TV drama series #CeritaKita (Our Story)—and accompanying social media discussion program Ngobrolin #CeritaKita (Chatter—Our Story)—as opposed to a placebo drama/discussion that lacked climate and environmental content. Outcomes were assessed via survey 1–7 days after exposure to the shows, and through a follow up survey after 5 months. We find that the treatment group became significantly more knowledgeable about environmental issues such as deforestation, an effect that persists long term. Other outcomes, such as motivation to participate in public discussion on climate change, willingness to follow influencers who post about environmental issues on social media, support for policies to address climate change and support for more media coverage of this issue, moved initially after viewing but subsided over time, possibly due to lack of continued exposure and other changes in context. This pattern of results suggests that ongoing/seasonal programming may be needed in order to sustain attitudinal and behavioral change.

1 Introduction

Indonesia has some of the world’s largest tropical rainforests and is one the most biodiverse countries (Mongabay, 2011). It is also one of the largest producers of greenhouse gases (GHGs), primarily coming from energy production, transport, and deforestation (Dunne, 2019). While annual deforestation monitoring results from 2021–2022 showed a drop by 8.4% compared to 2020–2021 according to official data (Ministry of Environment and Forests, 2023), deforestation is an ongoing concern particularly in secondary forests and other land not included in the official statistics (Teresia, 2023; Weisse et al., 2023). Forest fires have also become particularly common in recent years and have affected Indonesia’s emissions profile. The situation in Indonesia is further exacerbated by the fact that, due to its geography, the country is also particularly prone to devastating climate impacts, such as floods and droughts (Climate Risk Profile: Indonesia, 2021).

The Government of Indonesia has made notable commitments to address these issues, including a greenhouse gas emissions reduction target of 29–41% by 2030 as part of its commitment to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (2022). At the UN Climate Change Conference (COP26) in 2021, Indonesia further reiterated its commitment to foster low carbon growth and neutralize carbon emissions from deforestation. Nevertheless, its ability to fulfill these commitments depends on enhanced governance and accountability for sustainable use of its natural resources, which in turn requires large-scale public engagement.

Urban youth, in particular, can play a critical role in accelerating climate action. First, they make up a significant proportion of the Indonesian population—it is predicted that 46% of the population will be under the age of 30 by 2030, and 68% will reside in urban areas (Badan Pusat Statistik, 2013). Second, Indonesian youth have played an important role in political and governance issues over time, from the transition to a republican state to the demand for accountability around key livelihood or political decisions (Nowak, 2021).

Around the world, young people are leading engagement on climate action and sustainable lifestyles. However, climate change does not currently fit within the list of priorities for the majority of Indonesian youth. In nationally representative surveys, less than 3% (2019) and just under 5% (2022) of respondents below 30 spontaneously mentioned deforestation, pollution, and climate change as an important national issue (Devai and Eko, 2019, BBC Media Action, 2022). Indonesia is also home to an exceptionally large percentage of climate change deniers, who do not believe that humans are responsible for climate change (YouGov, 2020).

In response, BBC Media Action’s Kembali Ke Hutan (Return to the Forest) project aimed to engage Indonesian millennials on the sustainable development choices the country faces, help them to make informed decisions, and create platforms to have their voices heard. Programs included an award-winning1 TV drama #CeritaKita (Our Story), a companion social media discussion series Ngobrolin #CeritaKita (Chatter—Our Story), a social media brand AksiKita Indonesia (Our Action), and partnerships with media and civil society organizations for community engagement and capacity building.

Programming was shaped by formative research that demonstrated the need to motivate young Indonesians to engage with deforestation and green growth issues. While young people around the world lead engagement on climate action, our research found that climate change did not fit within the list of priorities for the majority of Indonesian youth (Devai and Eko, 2019). This finding led to a theory of change that focused on showcasing the positive social/identity impact of being engaged, building pride in Indonesia’s natural environment, and generating concern about the negative effects that human actions have on the climate and deforestation (Garg et al., 2023). Using an information-rich storyline that conveyed crucial facts about imminent environmental problems, we sought to increase the desirability of being interested in, discussing, and acting on climate issues using youth-led engaging, interactive and participatory platforms under an Indonesia digital youth brand.

With these objectives in mind, dramatic characters were developed to resonate with different audience segments, and plotlines were crafted to demonstrate the positive effects of individual and collective action. For example, Bodo, the lead character, is initially unengaged with climate change but witnesses air pollution, rubbish, floods, and deforestation in his community and learns about climate change from his love interest and the drama’s key protagonist, Tuji. Bodo’s civic identity transforms and he goes on to contest and eventually win the local election based on a sustainable development mandate. The drama showcases how people, communities, and local leaders can find their own ways to influence climate action and inspire system change. Kembali Ke Hutan (Return to the Forest) media outlets reached an estimated 24.5 million people (17% of the 15 years+ population living in target areas of Java, Sumatra, and Kalimantan) through the TV show and social media content (e.g., Instagram with 64,500 followers, YouTube short films with 96,500 subscribers, as of August 2022). The project’s brands were recalled by 35 million people—with over 10 million people who had not watched the output being aware of it, suggesting high media visibility and ability of the content to generate discussion (BBC Media Action, 2022).

The present paper describes an attempt to evaluate the impact of #CeritaKita and accompanying discussion on young Indonesian adults’ knowledge about environmental issues, their support for policies designed to address environmental degradation, and their willingness to devote time and effort to follow the issue and take action. We conducted a randomized experiment in which young Indonesian TV viewers were encouraged either to watch four episodes of #CeritaKita or an unrelated drama.2 A midline survey that measured a variety of beliefs, attitudes, and behavioral intentions was conducted between 1 and 7 days after the viewing period, and a similar endline survey was conducted 5 months after that. This research design offers a rare opportunity to study the rate at which the effects of exposure decay over time.

To preview the results, the midline survey indicates that exposure to #CeritaKita had sizable and statistically significant effects on several outcomes: knowledge of environmental issues it covered, confidence in understanding deforestation, discussion of climate change and the environment, motivation to publicly discuss climate change, interest in following an influencer engaged on environmental themes, motivation to share on social media about environmental destruction, support for Indonesia’s environmental pledges, and support for increased media coverage of environmental topics. This pattern of results is consistent with other entertainment-education experiments in domains such as health (Banerjee et al., 2019; Green et al., 2021) and gender equality (Green et al., 2020, 2023) but is the first to our knowledge to demonstrate these effects for TV dramas related to climate change. The endline survey indicates that although significant effects on knowledge persisted over time, other effects observed at midline largely subsided. This pattern of results suggests that ongoing media interventions that create momentum beyond being an initial catalyst may be needed to sustain attitude and behavioral change.

This paper is organized as follows. We begin by providing some theoretical background from the literature on entertainment education. Next, we describe the context in which the study was conducted and the manner in which participants were sampled and recruited. We describe the content of the treatment and control TV shows that participants were encouraged to watch, from which we derive hypotheses about what kinds of beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors may be affected. We then turn to the midline and endline survey instruments, describing the measures we used to assess knowledge about the causes and consequences of deforestation and climate change, interest in the issue, public discussion on climate, behavioral intentions, engagement with climate issues, and support for more media coverage of climate issues. The results section begins by confirming that the randomly assigned treatment and control groups had similar background characteristics and then demonstrates that compliance with assigned treatment was reasonably high. After assessing the effects of the random encouragement across an array of midline outcomes, we show the extent to which some, but not all, effects subsided by the endline several months later. We conclude by reflecting on the implications of these findings for future interventions and tests.

2 Theory

Leading theories in social psychology and communication suggest that narrative entertainment may be uniquely suited to inform and persuade (Paluck, 2012). In contrast to overtly persuasive messages, whose messages audiences either avoid (Knobloch-Westerwick, 2014) or resist (Kruglanski et al., 1993), narrative entertainment is thought to be effective for three reasons. First, when persuasive messages are embedded in an entertaining narrative, audiences may encounter counter-attitudinal content they might otherwise avoid (Strange, 2002). Second, when audiences become absorbed in a story and see things from the point of view of the main characters, their tendency to counter-argue diminishes. This causal mechanism fits within the Elaboration Likelihood Model of persuasion (Slater and Rouner, 2002).

A third reason to expect narratives to persuade stems from Social Cognitive Theory (Bandura, 2004). Appealing characters who are shown to thrive over the course of a narrative serve as models of socially appropriate attitudes and behavior. In essence, narratives teach audiences what good and bad characters think and do, which may explain why previous experiments have shown entertainment-education to be successful in changing attitudes and behavioral intentions (Green et al., 2020). A complementary argument is the theory of positive deviance (Singhal and Svenkerud, 2019), which holds that positive role models need not be generated through instigation by outsiders; persuasive narratives may work best when the attitudes and actions that are modeled come from local characters, because solutions that are “generated locally are more likely to be owned by local adopters.” (p.10).

At the same time, theory and evidence suggest that the effects of entertainment education may be short-lived. Just as narratives raise the salience of particular topics and win support for political and social causes, subsequent messages about other topics may draw attention away from these issues, causing their persuasive effects to diminish over time. Another reason that effects may decay is that when audiences return to their social environments, they may encounter countervailing messages that undercut the persuasive narrative. Diminishing treatment response over time is a robust finding in media studies (Hill et al., 2013) and cognitive psychology more generally (Rubin and Wenzel, 1996). Studies of entertainment-education find this pattern as well. For example, in their study of narratives about forced marriage of underage girls in East Africa, Green et al. (2023) found that weeks after exposure to this radio soap opera, audiences in the treatment group became significantly more likely to oppose this practice and that the effects were largest in the most socially conservative villages. However, a year later (with no further exposure to media narratives on this topic), the effects had largely subsided, perhaps reflecting the fact that many in the treatment group reverted to the views that prevailed in their conservative milieu.

Taken together, these theories lead us to expect short-term change in the wake of narrative entertainment about climate change, but the extent to which these changes persist in the absence of further media coverage remains an open question.

3 Research context

This study was conducted from November 2021 through May 2022, during the global COVID-19 pandemic. Because of the potential risks of data collection, face-to-face recruitment took place under strict COVID-19 protocols.

4 Research design

4.1 Subject pool/recruitment

Fieldwork was conducted by a local market research company, Cimigo,3 following a competitive procurement managed by BBC Media Action’s Indonesia office. The study used quota sampling to recruit respondents. To meet the selection criteria, potential respondents had to be at least weekly consumers of SCTV but must not have watched any episodes of #CeritaKita or engaged with Ngobrolin CeritaKita online. Recruitment took place in five Indonesian cities: Jakarta, Surabaya, Medan, Makassar, and Banjarmasin. Sampling was proportional to city size. A total of 869 participants were recruited in order to obtain approximately 800 panel survey respondents who would complete baseline, midline, and endline surveys. During recruitment, all respondents read and signed a consent form4 that described the study, data management, confidentiality, and provided contact details for the enumerators. Respondents are 24 years old, on average, and men and women are equally represented. The modal respondent has a high school degree and uses social media “several times per day.”

4.2 Description of the treatment and control interventions

Participants in the treatment group watched a distillation of storylines from the drama series (25 min) along with supporting content from the discussion program (5 min). The control group watched a TV drama and discussion of similar production value on a subject that bore no connection to environmental issues. Links to four episodes were provided to respondents, and they could watch the drama (treatment or control) over 1 week period.

4.3 Measures

The baseline screener interview collected information on demographics (gender, age, city, socioeconomic status, and education) and media consumption, in particular viewership of SCTV and #CeritaKita. For participants to qualify for the study, they had to be viewers of SCTV but not #CeritaKita.

The midline survey, which respondents completed between 23 November and 30 December 2021, measured outcomes that #CeritaKita was designed to shift. These included:

• Recent discussion of climate and the environment

• Knowledge of the environmental impact of human activities

• Assessment of deforestation’s effect on people’s lives

• Perceptions about whether urban dwellers could do anything about deforestation

• Beliefs about the threat posed by deforestation and climate change, especially for urban dwellers

• Willingness to follow influencers who post about environmental issues on social media

• Behaviors and behavioral intentions relevant to conservation

• Sense of individual and collective efficacy in influencing environmental outcomes

• Support for environmental policies

• Appetite for more media coverage of climate issues.

On top of these outcomes, the survey also measured some placebo outcomes that were not expected to be influenced by #CeritaKita. These included knowledge about COVID-19 and interest in politics.

Cognitive testing with a small set of respondents (n = 5) was conducted during midline questionnaire design to confirm that respondents understood the questions. The final questionnaire was translated into Bahasa Indonesia and independently back-translated to English.

4.4 Timeline

Enumerators were trained in virtual sessions on October 18–22, 2021. A pilot test involving 50 respondents was carried out on October 25–29, 2021. Some outcome measures were revised in order to make them clearer and less prone to skewed response distributions. Data collection resumed on November 23, 2021. Fieldwork paused once again after the first 100 cases were collected—these were checked to ensure that randomization was properly implemented, attrition was balanced across experimental conditions, and survey outcomes were coded according to our instructions. The remaining data collection process was carried out between December 7 and December 30, 2021. After cleaning, the final dataset with n = 843 valid and n = 26 attrited respondents was received on January 12, 2022. At the end of the midline survey, respondents were invited to continue participation in research related to their viewing experience. 85% agreed to be re-contacted, which enabled the administration of an endline survey between April 22 and May 25, 2022, about 5 months after initial exposure.

4.5 Statistical model

The key statistical assumption underlying the research design is that encouragement to watch the treatment program is statistically independent of potential outcomes. This assumption is satisfied by random assignment of subjects to treatment and control groups. In this instance, random assignment was conducted by the research agency and monitored by the authors. In order to verify that random assignment produced the expected degree of covariate balance, we conducted a regression analysis in which random assignment (Z = 0 for control and 1 for treatment) was regressed on background covariates measured prior to random assignment. These covariates include the categorical variables gender, age ranges, geographic location, source of household water, and educational attainment. As expected, the F-statistic (0.79), which tests the null hypothesis that all slope coefficients are zero, is nonsignificant (p = 0.65). In other words, differences in the background characteristics of treatment and control subjects are relatively minor and in the expected range.

A further check on the randomization of treatment and control is whether covariate balance persists after some subjects dropped out of the study. A small proportion of subjects were lost to follow-up because they refused to respond to the midline interview. Fortunately, rates of attrition were similar in treatment (3.8%) and control (2.1%). The apparent difference is not greater than would be expected by chance if attrition were random (p value = 0.14). The endline interview conducted approximately 5 months later had a lower response rate. However, attrition rates in the endline were similar in treatment (30.2%) and control (25.6%). This difference is not greater than would be expected by chance if attrition were random (p value = 0.13).

Because exposure to the media treatment can be encouraged but not enforced, there is some slippage between treatment assigned and treatment received. Some of the subjects who were assigned to watch the treatment drama may not have watched, and some who watched may not have paid attention while doing so. One approach is to ignore noncompliance and simply study the intent-to-treat effects of our random encouragement to watch on beliefs and attitudes. Another approach is to quantify the share of the assigned treatment group that actually took the treatment; in the latter case, if one is prepared to say that X% of the assigned treatment group watched enough to receive the communication objectives within the drama while the remaining (100 − X)% were entirely unaffected by the drama, one can back out the average effect of watching the drama on the subset of subjects known as “compliers,” who would watch the drama only if they were encouraged to do so (Gerber and Green, 2012, chapter 5).

In order to get a sense of the share of compliers, the midline survey concluded with a battery of questions that quizzed subjects in the treatment group about the characters and plot line of the treatment drama. Answers to the four factual questions about the plotline form a scale ranging from 0 to 4, based on the number of correct answers. More than one-third (37.8%) of respondents answered all questions correctly; another one-third (34.7%) made only one error. Very few (2.6%) failed to give any correct answers. Because the level of compliance seems high, there is relatively little difference between the effects of encouragement and the effects of actual viewing, and so this report focuses exclusively on the former. It should be noted that the effects of actual viewing among compilers are greater, and so our approach errs on the conservative side.

5 Results

5.1 Midline results

This section summarizes the midline results from each of the primary outcome measures, grouped by category. Because respondents were not offered the option to volunteer answers or skip questions, there is no item-level missingness in the midline or endline results, and thus the Ns remain constant across outcome measures.

5.1.1 Knowledge outcomes

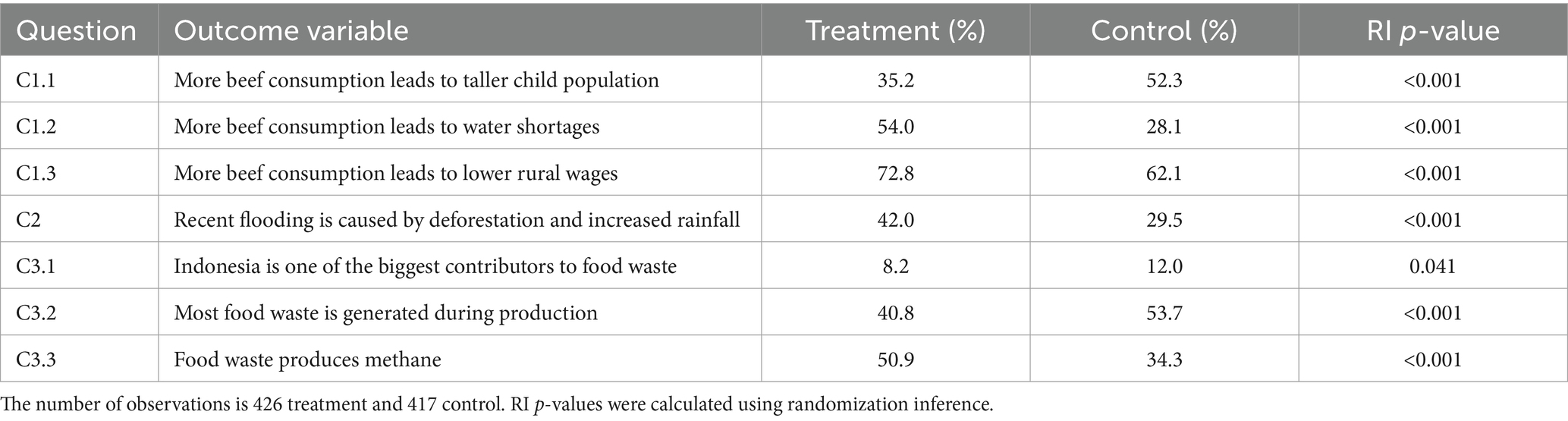

In order to assess whether the treatment program imparted information about the causes and consequences of deforestation and climate change, a series of factual questions were posed to assess respondents’ knowledge:

“C1. As Indonesians consume more beef they buy in the market, this leads to…A taller child population, Water shortages, or Lower wages of people working in rural areas?”

“C2. So far as you know, what has caused recent flooding in big cities in Indonesia? Please select two options: Increased construction of dams, Deforestation, Changing sea currents around Indonesia, or Increased rainfall.”

“C3. Thinking about food waste, which of the following is correct? Indonesia is one of the lowest contributors to food waste in the world, In Indonesia most food waste is generated in the process of production, or Food waste produces methane, which contributes to climate change.”

The correct answer to C1 is “Water shortages.” This answer was given by 54.0% of subjects in the treatment group, as compared to 28.1% in the control group. The apparent difference of 25.9 percentage points is substantively quite large and highly statistically significant (p < 0.001). The correct answers to C2 are “Deforestation” and “Increased rainfall.” This pair of correct answers was given by 42% of subjects in the treatment group, as compared to 29.5% in the control group. The apparent difference of 12.5 percentage points is substantial and statistically significant (p < 0.001). Finally, the correct answer to C3 is “Food waste produces methane, which contributes to climate change.” This answer was given by 50.9% of the treatment group and 34.3% of the control group. Again, this difference is large and extremely unlikely to have been generated by chance (p < 0.001).

Taken together, responses to these three questions leave little doubt that viewers of the treatment drama absorbed and retained a substantial amount of policy-relevant factual information. When all three questions are pooled into a single knowledge index, just 23.9% of the treatment group offered no correct answers, as compared to 40.4% of the control group. Perfect quiz scores were achieved by 18.1% of the treatment group and 6.6% of the control group (Table 1).

5.1.2 Climate change as a topic of conversation

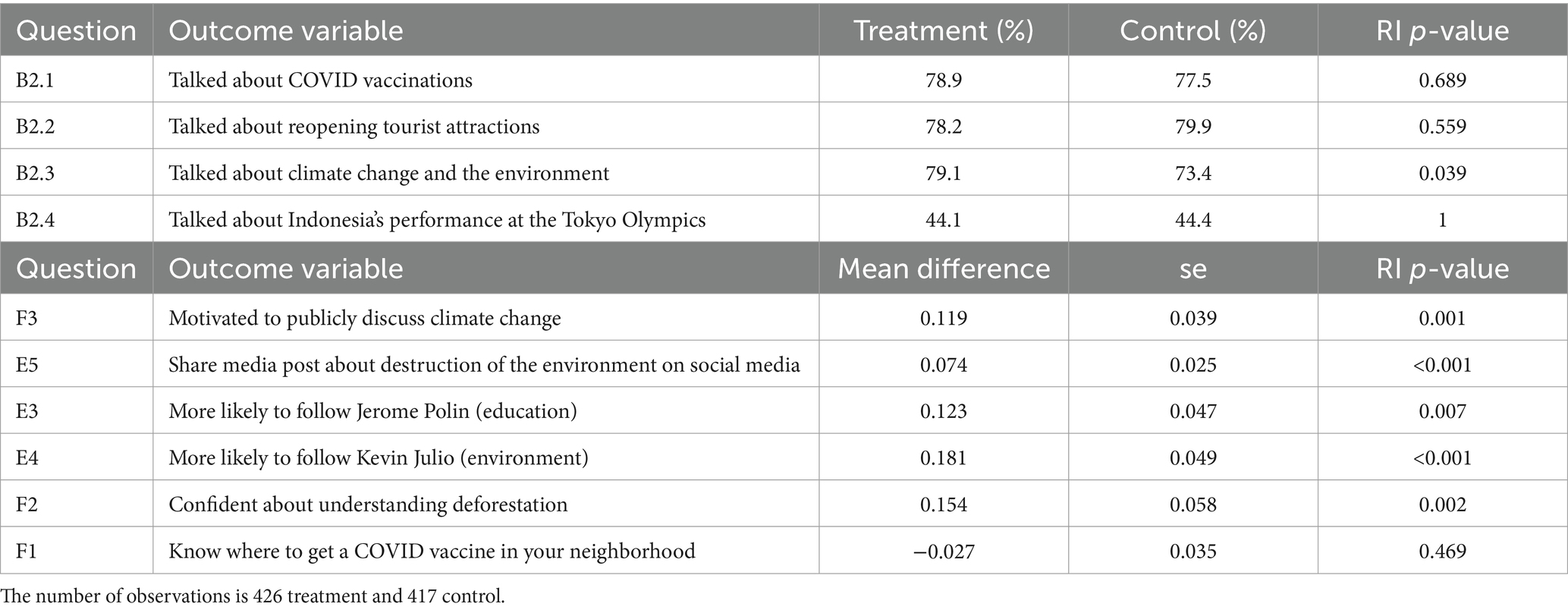

The next battery of questions measured whether climate change became a more frequent topic of conversation. One sign that the treatment drama piqued viewers’ interest is that they subsequently became more likely to report discussing “climate change and the environment” with their family and friends. Rather than ask this question point blank, we buried it in a series of questions about current events:

“B2. During the past few days have you talked about any of the following topics with your family or friends? COVID vaccinations … Re-opening of tourist attractions, malls and movie theaters … Climate change and environment … Indonesia’s performance at the Tokyo Olympics.”

As expected, treatment and control group subjects responded similarly to each of the non-environmental topics. The treatment group, however, was significantly (p = 0.039) more likely to report discussing climate change and the environment (79.1%) than the control group (73.4%). Treatment group respondents were also more likely to express a motivation to participate in public discussion, as measured by the following question:

“F3. How motivated do you feel about participating in a public discussion on how climate change and extreme weather events affect your lives? [Very motivated, Somewhat motivated, Not very motivated].”

The treatment group was 0.119 points (out of a three-point scale) more motivated to participate, as compared to the control group. The p value of 0.001 suggests that this apparent effect is unlikely to be due to chance.

This motivation finds expression in greater willingness to share social media posts on environmental topics. The question read as follows:

“E5. Some people are so interested in the destruction of the environment that they would be inclined to share environmental posts on social media. How about you? Would you feel inclined to share on social media, or you are not that interested?”

The treatment group was 0.074 points (along a four-point scale) more willing to share social media posts than the control group, a statistically significant difference (p < 0.001).

Another indication that the treatment group became more favorably disposed toward on-line environmental communication has to do with following social media influencers. Subjects were presented with two potential influencers. First, respondents were asked, “Some public figures like Jerome Polin engage on issues such as creating educational opportunities for all segments even for the poor. Would you be more or less likely to ‘follow’ the social media account of Jerome Polin if you knew that he recently spoke out on creating educational opportunities?” Second, respondents were asked about an influencer whose views were closer to the substance of the treatment: “Some public figures like Kevin Julio engage on environmental issues. Would you be more or less likely to ‘follow’ the social media account of Kevin Julio if you knew that he recently spoke out on environmental issues?” When developing the outcome measures, we expected the Kevin Julio outcome to be more strongly affected by the intervention. Table 2 shows that the treatment seems to have significantly affected both outcomes, especially the latter. Elevated support for Kevin Julio was in line with expectations, but elevated support for Jerome Polin was unexpected, since the prime mentioned only the issue of creating educational opportunities. Although the TV drama might have indirectly increased interest in education, another interpretation is that this false positive occurred by chance due to the number of outcomes we considered.

Does the treatment drama make viewers more confident about their understanding of deforestation’s effects? Respondents were asked

“F2. There has been a lot of talk recently about how deforestation in Indonesia affects flooding. How confident do you feel about your understanding of this issue [Very confident, Somewhat confident, Not at all confident], or is this not an issue you have been following?”

The treatment group was 0.154 units (along a three-point scale) more confident about their understanding of deforestation than the control group, a statistically significant difference (p = 0.002). Reassuringly, no such gap was found for confidence about an irrelevant topic, “knowing where to get a COVID vaccine in your neighborhood” (p = 0.469). We infer, therefore, that the audience’s growing sense of confidence on the topic of deforestation is due to exposure to the treatment.

5.1.3 Perceptions

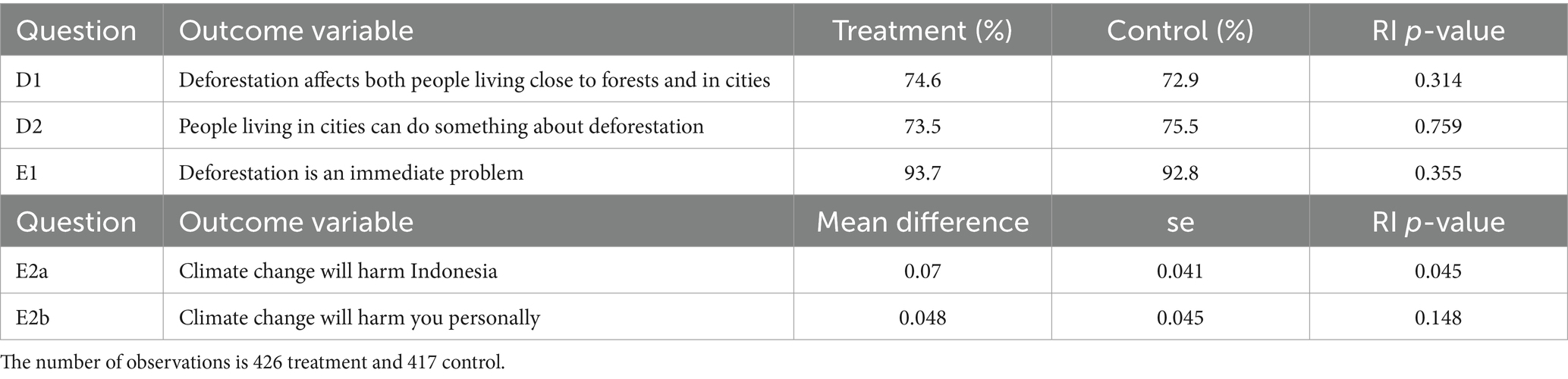

Two questions tapped respondents’ assessment of whether the impact of deforestation is felt outside rural areas adjacent to the diminished forests.

“D1. People have different opinions about deforestation in Indonesia and how it affects their lives. By deforestation we mean the destruction and conversion of forest land to other land use. Which statement comes closer to your view: Deforestation affects only the daily lives of people living close to forests, or Deforestation affects both people living close to forests and people in the city?”

“D2. People have different opinions about what can be done to address deforestation. Which statement comes closer to your view: People living in a city cannot do anything to address deforestation, or People living in a city can do something to address deforestation.”

Both questions reveal relatively small treatment effects. The view that deforestation affects both people living close to forests and people in the city is endorsed by 74.6% of the treatment group and 72.9% of the control group. This apparent effect is in the expected direction, but the difference falls short of conventional levels of statistical significance (p = 0.314). On the other hand, those in the treatment group were slightly less likely (73.5%) to endorse the view that people living in a city can do something to address deforestation than their control group counterparts (75.5%). This small difference is not in the expected direction and is not statistically distinguishable from zero (p = 0.759).

Three questions assessed respondents’ sense of the gravity of environmental problems.

“E1. Some people say that the loss of forest land in Indonesia is an immediate problem that threatens biodiversity (e.g. variety of animals, plants). Others say that threats to Indonesia’s environment are trivial problems. Which comes closer to your view?”

“E2a. How much will climate change harm people in Indonesia? … Not at all … Only a little…A moderate amount…A great deal.”

“E2b. How much will climate change harm you personally? … Not at all … Only a little …A moderate amount …A great deal.”

Both treatment and control respondents are overwhelmingly of the opinion that deforestation is an immediate problem. The treatment group edges ahead of the control group (93.7–92.8%), but the difference falls short of statistical significance (p = 0.355). The treatment group is, however, 0.07 points (on a four-point scale) more likely to agree that climate change will inflict harm on Indonesia than the control group. A regression of this outcome measure on treatment assignment yields a p value of 0.045. This borderline result suggests that treatment respondents are somewhat more likely to anticipate harms to the country than their control group counterparts. However, the treatment effect is more muted when it comes to perceived personal harms. The treatment group is only 0.048 points (on a four-point scale) more likely to anticipate personal harm than the control group (p = 0.148). Overall, the results suggest that #CeritaKita may have increased concern for Indonesia among the treatment group but did not elevate concern about personal adverse effects (Table 3).

5.1.4 Behavioral intentions, support for policy, and interest in media coverage

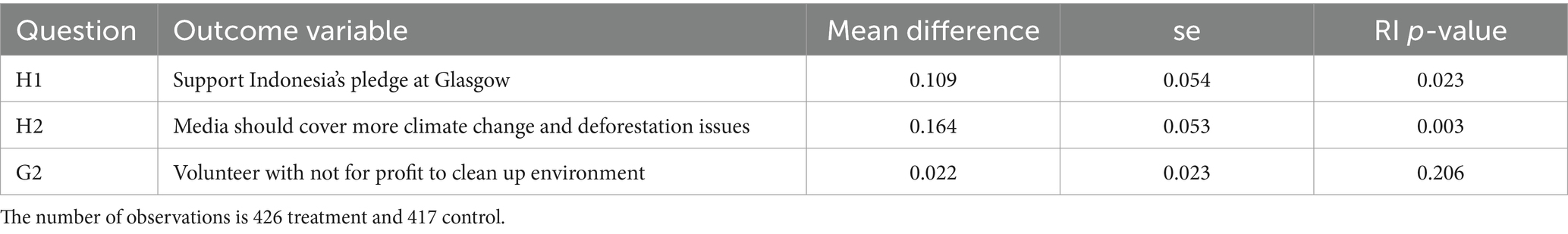

One potential consequence of sensitizing viewers to issues of environmental degradation and climate change is that it enhances their support for international efforts to address deforestation.

“H1. How much do you support the Indonesian government’s pledge made at the Glasgow climate conference to stop deforestation by 2030?” Responses range from (1) Strongly oppose to (4) Strongly support.”

Table 4 suggests that the treatment did raise policy support. The average response is 0.109 units (on a four-point scale) higher in treatment than control (p = 0.023).

Table 4. Behavioral intentions, support for policy, and interest in media coverage of climate change, by treatment condition.

One concern among proponents of drama for development is that although the shows are more engaging than non-narrative modes, these programs are less engaging than “pure” entertainment. One aim of a well-crafted social and behavior change drama is to create a new appetite for programming in this issue domain (as well as inspire others broadcasters to use their unique platforms to support climate action). We therefore asked the following agree/disagree question:

“H2. Media companies/broadcasters should do more to cover climate and deforestation issues in their content?” Responses range from (1) Strongly disagree to (4) Strongly agree.”

The treatment group proves substantially more supportive of media coverage of climate change and deforestation than the control group. The treatment group is 0.164 points (on a four-point scale) more likely to support this policy than the control group (p = 0.003).

On the other hand, the treatment seems to be less pronounced when it comes to expressing an intention to engage in local community action.

“G2. A not for profit organization that is concerned about Indonesia's natural resources carries out tree planting and trash clean ups in rivers. If they conduct this activity in your city in the next month, would you be interested in getting involved? [Yes, No].”

Although rates of intent to volunteer are elevated slightly in the treatment group compared to the control group, we cannot rule out the possibility that the observed 2.2 percentage point gain is due to chance (p = 0.206).

5.2 Endline results

Relatively few randomized evaluations of narrative dramas have assessed whether effects decay over time.5 Understanding whether decay occurs, and for which outcomes, is crucial for developing narratives that have momentum and are impactful enough to change public opinion and policy-relevant outcomes. We therefore attempted to reinterview midline respondents in order to see whether the treatment-control differences persisted approximately 5 months later.

5.2.1 Persistence of treatment effects for knowledge-related questions but not attitudinal or behavioral questions

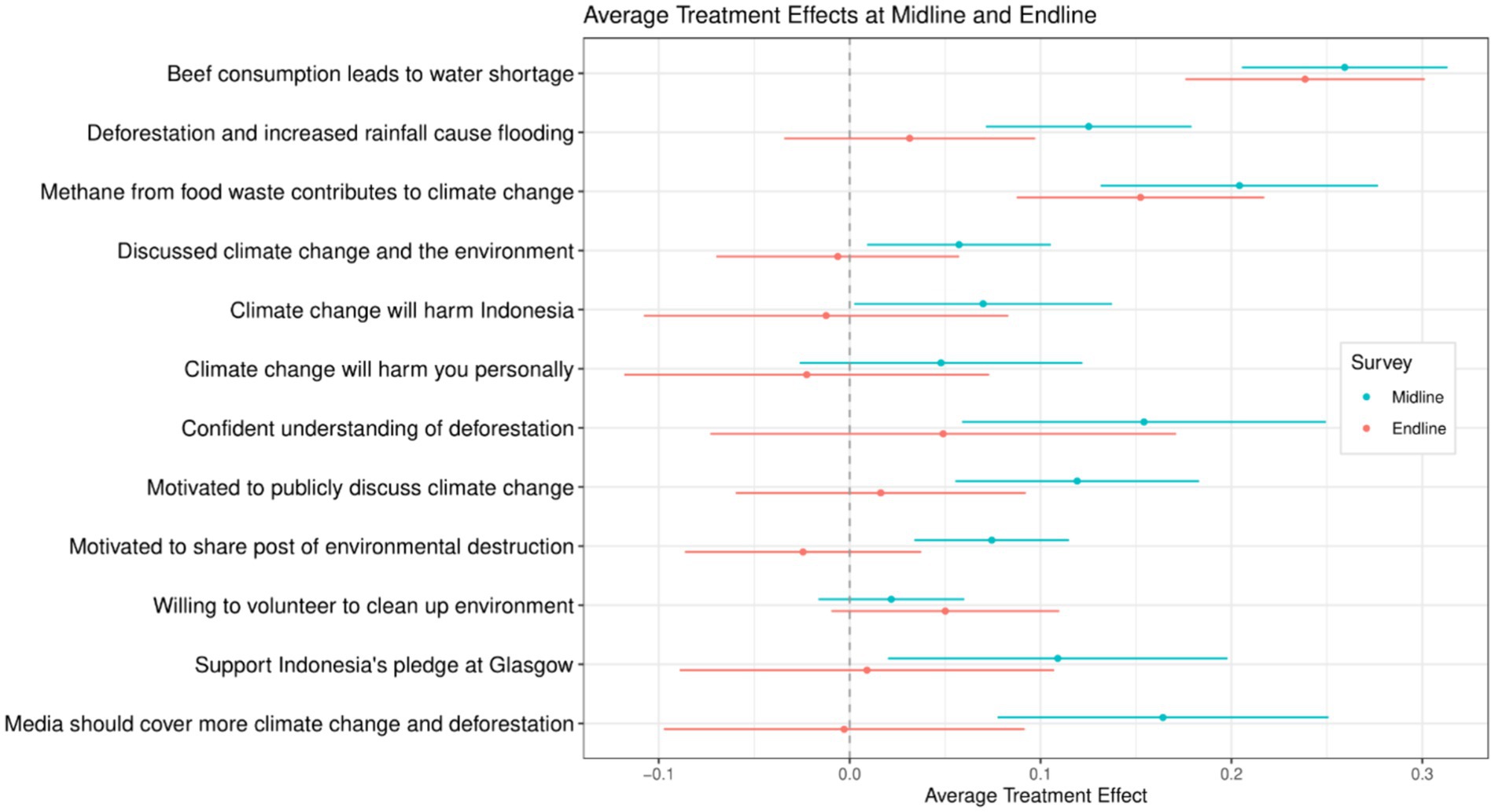

Figure 1 shows the persistence of treatment effects for responses to knowledge-related questions asked in both the midline and endline surveys. Although all three knowledge items show smaller effects at endline, the pooled effect remains statistically significant and substantively meaningful. On the other hand, all of the other apparent treatment effects at midline appear to have subsided by the endline. For example, respondents in the treatment group were much more willing than those in the control group to share a post about the destruction of the environment on social media at midline, but at endline, were no more willing to do so. Similarly, the treatment effect on support for the Indonesian government’s pledge at Glasgow to stop deforestation that was apparent at midline is all but absent at the endline. This pattern of over-time change has an interesting theoretical implication insofar as it demonstrates that although an initial change in knowledge coincided with changes in attitudes and behavioral intentions, knowledge gains seem to persist but without motivating concomitant changes in policy support or willingness to share environmental posts or volunteer for environmental collective action.

Figure 1. Comparison of average treatment effects between midline and endline surveys. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals around the estimate. The number of midline and endline responses were 843 and 626, respectively.

6 Conclusion

Taken together, the experimental study paints a promising picture of #CeritaKita’s (and Ngobrolin #CeritaKita’s) short-term impact. Interviewed a couple of days after their last exposure to four episodes (approximately 2 h of content), respondents expressed changed beliefs and attitudes in the desired direction on:

• knowledge of environmental issues it covered;

• confidence in their understanding of deforestation;

• discussion of climate change and the environment;

• motivation to publicly discuss climate change;

• interest in following an influencer engaged on environmental themes;

• motivation to share on social media about environmental destruction;

• support for Indonesia’s COP pledge; and

• support for increased media coverage of environmental topics.

However, exposure to the treatment had no immediate effects on a number of other outcomes:

• perceived severity of deforestation and climate change as immediate problems;

• perceived collective risk from climate change;

• urban people’s perceived efficacy when attempting to do something about deforestation;

• interest in getting involved in local environmental action.

The positively-affected outcomes may be broadly characterized as involving the acquisition of pertinent information, confidence about their understanding of the subject, and eagerness to hear more about it. Despite increased awareness of facts and discussion of the topic with others, policy support saw equivocal gains, perhaps because respondents in the treatment group did not emerge with a heightened sense of risk or efficacy. Behavioral intentions, such as getting involved in a local environmental action, were largely unaffected in the short run. Further research is needed to learn whether and how the content of environmentally-themed dramas can be adjusted to produce stronger effects on policy support and behavioral intentions. Studies of narrative entertainment in other substantive domains suggest that achieving such effects is possible (Rahmani et al., 2023).

Our evaluation is one of the few studies to investigate the persistence of media effects several months after exposure. Knowledge gains appear to persist, albeit with some attenuation. Effects on other outcomes, such as policy support and motivation to engage, appear to have dissipated almost entirely by endline.

Further research is needed to assess whether sustained exposure to media content on climate in turn sustains the treatment effects over time. Although studies such as this one clearly demonstrate the immediate efficacy of a few hours of programming, the next step in this line of research is to assess the effects of continual exposure, randomly assigning audiences to weeks or months of media content. An even more ambitious design would be a field experiment in which randomly selected media markets are saturated with ongoing programming—perhaps narrative entertainment alone or a mix of dramas and non-narrative coverage—on topics such as climate change. An advantage of the latter approach is that it not only contributes to the question of whether increased dosage amplifies effects but also allows for the study of policy-relevant behavioral outcomes that may occur within media markets.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Institutional Review Board at Columbia University, Morningside Heights Campus. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

DG: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. RE: Investigation, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. LO: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. BP: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AGo: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AGa: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HR: Investigation, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The Kembali Ke Hutan (Return to the Forest) project was funded by the Norwegian Development Cooperation Agency (Norad), grant reference number GLO-4060 INS-16/002.

Acknowledgments

We thank BBC Media Action’s project, research and production teams, as well as funder Norad, for having the foresight and openness to support this study. We also thank the Cimigo research agency for their fieldwork and, importantly, the study’s participants for sharing their time over the course of the project.

Conflict of interest

DG served as an outside evaluator and received no compensation for his work on this project. RE, LO, and HR were employed by BBC Media Action, Indonesia. BP and AGo were employed by BBC Media Action, United Kingdom. AGa was employed by BBC Media Action, India.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2024.1366289/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^Daftar Pemenang Festival Film Bandung, 2021. (2021, October). Festival Film Bandung. Available at: https://www.festivalfilmbandung.com/2021/10/daftar-pemenang-festival-film-bandung-2021.html.

2. ^This study was part of a wider mixed-method evaluation that included a process evaluation, a representative survey, qualitative research, social media analytics, and interviews with climate and forestry experts.

3. ^https://www.cimigo.com/en/

4. ^This document was reviewed and approved by the Columbia University IRB under protocol AAAT8838.

5. ^One study of short videos on violence against women found persistence in viewers’ willingness to take action over a span of 8 months (Green et al., 2020); another study found persistent effects of viewing six episodes of a drama designed to reduce prejudice against Arab Muslims over 3 months (Murrar and Brauer, 2018); other studies have found that treatment effects decay if lessons are not reinforced through repeated messaging or through group viewing and discussion (Nsangi et al., 2020).

References

Badan Pusat Statistik (2013). Proyeksi Penduduk Indonesia 2010–2035. Available at: https://www.bps.go.id/id/publication/2013/10/07/053d25bed2e4d62aab3346ec/proyeksi-penduduk-indonesia-2010-2035.html

Bandura, A. (2004). “Social cognitive theory for social and personal change enabled by the media” in Entertainment-Education and Social Change: History, Research, and Practice. eds. A. Singhal, M. Cody, E. M. Rogers, and M. Sabido (Mahwah, N.J: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates), 75–95.

Banerjee, A, La Ferrara, E, and Orozco-Olvera, VH (2019). “The entertaining way to behavioral change: Fighting HIV with MTV.” Working Paper.

BBC Media Action (2022). How media can engage youth to take climate action. Research Briefings. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/mediaaction/publications-and-resources/research/briefings/asia/indonesia/climate-2022

Climate Risk Profile: Indonesia (2021). The World Bank Group and Asian Development Bank. Available at: https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/700411/climate-risk-country-profile-indonesia.pdf

Devai, S, and Eko, R (2019). Indonesia formative research. Internal Research Report. BBC Media Action.

Dunne, D (2019). The carbon brief profile: Indonesia. Carbon brief clear on climate. Available at: https://www.carbonbrief.org/the-carbon-brief-profile-indonesia

Garg, A., Godfrey, A., and Eko, R. (2023). “Kembali Ke Hutan (return to the Forest): using storytelling for youth engagement and climate action in Indonesia” in Storytelling to Accelerate Climate Solutions. eds. E. Coren and H. Wang (New York: Springer).

Gerber, A. S., and Green, D. P. (2012). Field experiments: design, analysis, and interpretation New York: W.W. Norton.

Green, D. P., Groves, D. W., and Manda, C. (2021). A radio Drama’s effects on HIV attitudes and policy priorities: a field experiment in Tanzania. Health Educ. Behav. 48, 842–851. doi: 10.1177/10901981211010421

Green, D. P., Groves, D. W., Manda, C., Montano, B., and Rahmani, B. (2023). A radio drama’s effects on attitudes toward early and forced marriage: results from a field experiment in rural Tanzania. Comp. Pol. Stud. 56, 1115–1155. doi: 10.1177/00104140221139385

Green, D. P., Wilke, A. M., and Cooper, J. (2020). Countering violence against women by encouraging disclosure: a mass media experiment in rural Uganda. Comp. Pol. Stud. 53, 2283–2320. doi: 10.1177/0010414020912275

Hill, S. J., Lo, J., Vavreck, L., and Zaller, J. (2013). How quickly we forget: the duration of persuasion effects from mass communication. Polit. Commun. 30, 521–547. doi: 10.1080/10584609.2013.828143

Knobloch-Westerwick, S. (2014). Choice and Preference in Media Use: Advances in Selective Exposure Theory and Research. New York, NY: Routledge.

Kruglanski, A. W., Webster, D. M., and Klem, A. (1993). Motivated resistance and openness to persuasion in the presence or absence of prior information. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 65, 861–876. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.65.5.861

Ministry of Environment and Forests (2023). Deforestation official statistics. Available at: https://sigap.menlhk.go.id/dok-elektronik

Mongabay (2011). Indonesia forest information and data. Mongabay.com. Available at: https://rainforests.mongabay.com/deforestation/2000/Indonesia.htm (Accessed November 30, 2023).

Murrar, S., and Brauer, M. (2018). Entertainment-education effectively reduces prejudice. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 21, 1053–1077. doi: 10.1177/1368430216682350

Nowak, N. (2021). Youth, Politics and Social Engagement in Contemporary Indonesia. Jakarta, Indonesia: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung.

Nsangi, A., Semakula, D., Oxman, A. D., Austvoll-Dahlgren, A., Oxman, M., and Rosenbaum, S.. (2020). Effects of the informed health choices primary school intervention on the ability of children in Uganda to assess the reliability of claims about treatment effects, 1-year follow-up: a cluster-randomised trial. Trials 21, 1–22. doi: 10.1186/s13063-019-3960-9

Paluck, E. L. (2012). “Media as an instrument for reconstructing communities following conflict” in Restoring Civil Societies. eds. K. J. Jonas and T. A. Morton (Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley), 284–298.

Rahmani, B, Green, DP, Groves, DW, and Montano, B (2023). “The persuasive effects of narrative entertainment: a Meta-analysis of recent experiments” in Paper presented at the Annual meeting of the Association for Psychological Science, Washington, D.C.

Rubin, D. C., and Wenzel, A. E. (1996). One hundred years of forgetting: a quantitative description of retention. Psychol. Rev. 103, 734–760. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.103.4.734

Singhal, A., and Svenkerud, P. J. (2019). Flipping the diffusion of innovations paradigm: embracing the positive deviance approach to social change. Asia Pacific Media Educ. 29, 151–163. doi: 10.1177/1326365X19857010

Slater, M. D., and Rouner, D. (2002). Entertainment-education and elaboration likelihood: understanding the processing of narrative persuasion. Commun. Theory 12, 173–191. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2885.2002.tb00265.x

Strange, J. J. (2002). “How fictional tales wag real-world beliefs: models and mechanisms of narrative influence” in Narrative Impact: Social and Cognitive Foundations. eds. M. C. Green, J. J. Strange, and T. C. Brock (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates), 263–286.

Teresia, A (2023). Indonesia cites deforestation decline from stricter controls. Reuters. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/indonesia-cites-deforestation-decline-stricter-controls-2023-06-26/

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (2022). Enhanced nationally determined contribution, Republic of Indonesia. 2022. Available at: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/NDC/2022-09/ENDC%20Indonesia.pdf

Weisse, M, Goldman, E, and Carter, S (2023). Forest pulse: the latest on the world’s forests. World Resources Institute. Available at: https://research.wri.org/gfr/latest-analysis-deforestation-trends (Accessed November 30, 2023)

YouGov (2020). Climate and lifestyle after COVID. Globalism Report. Available at: https://docs.cdn.yougov.com/rhokagcmxq/Globalism2020%20Guardian%20Climate%20and%20Lifestyle%20after%20COVID.pdf

Keywords: climate change, environment, deforestation, entertainment program, randomized trial

Citation: Green DP, Eko R, Ong L, Paskuj B, Godfrey A, Garg A and Rea H (2024) Changing minds about climate change in Indonesia through a TV drama. Front. Commun. 9:1366289. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2024.1366289

Edited by:

Anders Hansen, University of Leicester, United KingdomReviewed by:

Tendai Chari, University of Venda, South AfricaJens Wolling, Technische Universität Ilmenau, Germany

Copyright © 2024 Green, Eko, Ong, Paskuj, Godfrey, Garg and Rea. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Donald P. Green, ZHBnMjExMEBjb2x1bWJpYS5lZHU=

Donald P. Green

Donald P. Green Rosiana Eko2

Rosiana Eko2 Lionel Ong

Lionel Ong Benedek Paskuj

Benedek Paskuj Anna Godfrey

Anna Godfrey