- Faculty of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom

‘Foodscaping’ seeks to understand how meaning is made through humans’ interaction with food in particular environments through a multimodal and interdisciplinary analytical lens. As part of a foodscaping project, researchers often interpret food environments to which they are not intimately ‘local’. This presents cross-cultural limitations in the production of analysis. Most pertinently, how can personal interpretation be divorced from locally salient and meaningful discourses? This paper presents the findings of a pilot foodscaping analysis using the box notation style of Kim’s Korean Segmented Film Discourse Representation Structures (K-SFDRS). K-SFDRS notation, developed to provide both coarser- and finer-grained formal transcription for South Korean multimodal film discourse analysis, is tested as an analytic tool for an authentic South Korean foodscaping experience. This paper aims to ascertain whether the formal nature of K-SFDRS transcription is a useful aid to the analysis of a foodscape, which otherwise risks relying heavily on personal interpretation. This pilot study presents an introduction to both foodscaping and (K-)SFDRS, outlines the potentials of (K-)SFDRS notation within a foodscaping context, offers a step-by-step outline for constructing K-SFDRS box notation using an exemplar South Korean foodscape, and finally demonstrates how this box notation may be used in the support of foodscaping analysis in various interdisciplinary channels. During this pilot study, the authors make a novel methodological development in the form of what they term ‘cluster structures’, which overcome the problems presented by the lack of cinematic narrative editing in spontaneous discourse, segmenting meaning into logical forms within which structures of meaning are hierarchised without requiring the discourse relations to structure the logical forms themselves in narrative discourse following the original K-SFDRS methodology. The paper concludes that K-SFDRS, alongside the aforementioned methodological development, has potential to help foodscaping researchers constrain interpretation to salient discourses and direct foodscaping analysis down meaningful avenues. Through its culinary scope, this chapter adds a new disciplinary dimension to discussions of metalanguage and makes an innovative contribution to the current corpus of multimodal research.

1 Introduction

In this paper, we present a pilot study whose aim is to test the hypothesis that Segmented Film Discourse Representation Structures (SFDRS), more specifically the Korean language and culture specific K-SFDRS, can be used to formally transcribe spontaneous and authentic foodscaping experiences. The paper will test whether this formal tool can productively be used to produce data in support of the analysis of a Korean foodscape and the multimodal threads that produce meaning therein. This paper tests whether foodscaping, a discipline borne from multimodal analysis, but which lacks a formal mode of data representation across modalities, benefits from the use of logical forms which incorporate a range of multimodal utterances.

1.1 Foodscaping

This paper is borne from the authors’ work on a wider project concerned with ‘foodscaping’ various regions of East Asia, and our search for formal methodology in support of said project. In order to understand the basis of the current paper, we must first outline foodscaping and, accordingly, the gap in formal data analysis it presents. Norah MacKendrick defines a foodscape as such: ‘Consider the places and spaces where you acquire food, prepare food, talk about food, or generally gather meaning from food. This is your foodscape’ (MacKendrick, 2014, p. 16). A Foodscape describes a wider space centred around a food environment and in which people interact with food, not only by consuming it but also producing it, acquiring it, preparing it, and socialising around it. The crucial element in MacKendrick’s above definition is the specification that in a foodscape, human actors ‘generally gather some sort of meaning from food’ (MacKendrick, 2014, p. 16). This consideration sits at the heart of foodscaping as the authors define it. Foodscaping is the study of foodscapes; more specifically, it is the methodological process through which a participant, or observer, analyses and unravels the multimodal strains through which meaning is derived from the foods in question in that specific space. Thus, foodscaping seeks to understand how meaning is made through humans’ interaction with food – and, by extension, with one another over food – in particular environments (Calway et al., 2025).

Further to this, foodscaping puts primacy on the understanding of the cultures and societies which surround and define foodscapes. If meaning is to be derived from food and the manner with which it is interacted, a multitude of culturally- and contextually-informed values exert an important influence. For example, imagine two foodscapes based around establishments serving fried chicken: one in London, United Kingdom, and another in Seoul, South Korea. Whilst the basic building blocks of the foodscape may be similar, the meanings constructed around the foodscape are entirely different. The side dishes customers eat with the chicken, the times at which customers purchase and eat the food, the groups or individuals with which they choose to eat the food, whether the chicken is eaten in the restaurant or at home as a takeaway, the manner and language in which the food is ordered and talked about; these factors and more, whilst being unique to each individual, behave to a certain extent according to custom and cues unique to each location and culture. It is the interplay of these unique customs and cues which foodscaping seeks to depict.

In short, individuals and groups derive meaning from food. These meanings are unique to certain groups or individuals, interacting with certain foods, in certain places, at certain times. Beyond just describing the resulting food cultures, foodscaping seeks to lay bare the exact factors that have converged to produce said meanings. Foodscaping, on the one hand, seeks to separate and consider these factors on their own terms, whilst, on the other hand, simultaneously recognising that it is their confluence which ultimately results in the meaning-making inherent to food in society. Thus, through foodscaping, foodscapes are deconstructed into numerous multimodal threads, understood according to the relevant academic discipline (i.e., language is analysed linguistically, historical processes are understood historically, anthropological considerations are understood anthropologically, etc.), and ultimately reconstructed in order to produce a refreshed, full picture of the meaning of food within the foodscape. Foodscaping therefore avoids pitfalls of which current food studies often fall foul: considering food through the lens of only one modality or discipline; or, conversely, attempting to consider the resulting meanings of food without affording due focus to each of these multifarious factors.

This approach to the analysis of a foodscape is highly complex; multiple modal inferences must be considered (such as spoken language, written language, movement, smells, tastes, sights, sounds, and temperature), each of which can be understood according to various disciplines (history, linguistics, sociology, psychology, anthropology). Where, then, does one begin? And how does one separate the different, simultaneous processes through which meaning is derived? These are the key questions which began our investigation, the result of which is this paper. It is all very well to say that Koreans eating a barbecue bond with one another by sharing food, on the one hand, and retain social distinctions by pouring one another alcohol according to age, on the other, but how does one trace these two processes all at once (Yu, 2017). More importantly, how can one use data (rather than just culturally-informed intuition, which is susceptible to bias) to verify that these processes are indeed happening? And lastly, how do we use this data to understand which threads of analysis are the most salient to the meaning-making we observe? Foodscaping, and food studies at large, lacks a logical approach through which foodscapes can be formally analysed and through which these questions can be answered using verifiable data. This is where KSFDRS comes in.

1.2 (K-)SFDRS

Before explaining the potential applicability of K-SFDRS to Foodscaping, we must first outline K-SFDRS, as well as the SFDRS from which it was derived. ‘Segmented Film Discourse Representation Structures’ (hereafter SFDRS) are a formal means of transcribing multimodality and how it unfolds to construct discourse in film, developed as a part of a framework from Multimodal Film Discourse Analysis by Wildfeuer (2012, 2014). The layered, dynamic discourses in foodscapes share a parallel with SFDRS in this respect, and have encouraged piloting the framework in this paper.

K-SFDRS is distinct from SFDRS in that it uses a set of Korean-specific socio-pragmatic rules for verbal and non-verbal language (‘socio-pragmatic primitives’) developed from Kiaer and Kim (2021) in addition to audio and visual elements to identify salient modalities and to infer the defeasible eventuality of those modalities as they interact, using them to draw the discourse structure. Studies by Kiaer and Kim (2021) and Kim (2022) both found that the socio-pragmatic expressions attached to modalities construct Korean narrative, drive it forward, and make its structure cohesive, as well as being predominantly responsible for defining the personalities, motivations, and intentions of characters. Kim (2022) found that discourse structures do not make sense without including socio-pragmatics in interpretation, and that doing so made interpretation much more specific. Kiaer and Kim (2021) have pointed out failing to follow socio-pragmatic rules, a lack of corroboration among modalities, or inconsistency in the socio-pragmatics at play in a given orchestration of expressions, either does not make sense or is purposely employed to show insincerity or strangeness. K-SFDRS also employs Kim and Kiaer’s (2021) granular division of discourse, which they term ‘higher activities,’ to organise the parts that form discourse and finer and coarser levels, though we do not employ this division system in this preliminary investigation. In order to illustrate the socio-pragmatic elements that constrain Korean interpretation of modality, which must be considered when studying Korean modalities, K-SFDRS includes in its annotation ‘[k]’ in addition to marking referents as either audio ‘[a]’ or visual ‘[v].’ This ‘[k]’ is positioned beneath people, objects, and expressions to indicate that the above is a Korean-specific socio-pragmatic or discursive element that has implications on other modalities in the given meaning-making process. In other words, ‘[k]’ indicates that an element is meaningful in the given context because of Korean socio-pragmatics. The use of the ‘[k]’ notation is exemplified in section 2 of this paper.

1.3 Why apply (K-)SFDRS to (Korean) foodscaping

(K-)SFDRS is highly applicable to foodscaping research in two key ways: firstly, multimodality is laid bare, and secondly, the most salient instances of multimodal communication can be identified in a controlled manner. Furthermore, it enables both researchers and readers to verify the findings of the ultimate output, referencing the specific modalities in their original context against the final interpretation of the author.

1.3.1 Multimodality

(K-)SFDRS provides a means of formally transcribing multimodality to facilitate their full and proper analysis. (K-)SFDRS notation not only takes into account all modalities present in a section of discourse, but it converts them into logical forms which point to the mode in which it is manifested, all whilst considering all modes together in one chronological graphic representation. In this way, (K-)SFDRS analysis avoids putting primacy on any one modality by considering them all as equal in their potential importance to meaning-making, whilst also retaining the nature of each modality so that they can be identified in the logical representation of the discourse. This limits the bias researchers might afford the more ‘apparent’ methodologies in a foodscape analysis, instead forcing them to consider all possible multimodal referents before narrowing them down to the most salient factors only after considering each and every one. We believe this to be highly relevant to foodscaping, as well as frameworks that resonate with it such as culinary linguistics (Gerhardt et al., 2013), where each modal thread must retain its original modality to be properly analysed, but should also be considered in terms of its confluence with other multimodal utterances in working towards the formation of meaning.

1.3.2 Salience

A major issue faced in discourse analysis is the difficulty distinguishing between salient and arbitrary (Bateman and Wildfeuer, 2014). Foodscaping is no exception. In fact, it is potentially one of the greatest challenges in discourse analysis, because it involves the interpretation of discourses in live environments, without the carefully planned narrative and editing to guide the researcher to meanings. Yet, these spaces exist at the communicative core of our social lives and are rich in customs, traditions, and forms of communication (Kiaer et al., 2024), and therefore undoubtedly contain discourses.

(K-)SFDRS has the basic aim of codifying and representing multimodal instances, enabling the researcher to identify the most salient moments in contributing to the segments of meaning inferred. We begin with the hypothesis that this may be a starting point for analysing spontaneous discourse in food environments. If people can identify salient modalities, then modalities that are acting in similar ways or corroborating with one another will also be identifiable; in the same way, it becomes apparent when modalities do not corroborate with one another. Based on this, referents may be categorised into groups which, although demonstrating subtle variations, demonstrate similar factors in the meanings to which they contribute. These groups may then be brought together into clusters that build more general meaning. As the researcher gains organisation over these clusters, they may employ their disciplinary background and individual expertise to draw discourses from the meaning-making processes. These structures can, with persistence, continue to branch further and further. The precise manner in which the branches develop depend on the discipline of the researcher; whilst the logical forms help to guide interpretation, the ability of the researcher is required to interpret said forms and thus their knowledge of these discourses is vital. This is why we recommend collaboration between researchers from different disciplines in research of foodscapes to make the most of the methodology (for more on this, see section 4).

1.3.3 Logical forms/graphic representation

The production of logical forms to which the researcher may point, and the reader may consult, further makes (K-)SFDRS a potentially beneficial tool for foodscaping. The description of spontaneous discourse in a foodscape is difficult to achieve through written prose, particularly when the aim is to identify several discourses, which require the identification of several salient modalities. Furthermore, an understanding of how and when each event takes place is most likely germane to a reader’s understanding. The box notations produced through (K-)SFDRS could prove useful in enabling the author to demonstrate this in concise, logical terms. Additionally, foodscaping, like a lot of ethnographic and cultural analysis, rests on the trust of both the researcher and the reader on the researcher’s own interpretation of the target culture and society. Whilst the authors do not wish to cast aspersions on the credentials of ethnographic researchers (indeed, quite the opposite), we propose (K-)SFDRS as a useful tool for reasoning, reviewing, and verifying to the researcher and reader alike the legitimacy of the researcher’s inferences. (K-)SFDRS effectively transforms qualitative interactions into a piece of data. Whilst this alone may not adequately give the full picture of a foodscape, it certainly can be used by the researcher as quantitative evidence for the veracity of their observances: which modalities are most salient in this foodscape and which discourses do they take their salience from? Not only does the process of (K-)SFDRS notation help find the answers to these questions, but the graphical forms produced lay them bare.

1.3.4 Cross-cultural translation and interpretation

The key factor in our choice to apply K-SFDRS, rather than SFDRS, to foodscaping analyses in the Korean context is its ability to effectively ‘translate’ Korean meaning-making. Cross-cultural development of SFDRS through socio-pragmatics has already been demonstrated as beneficial to interpreting culture specific discourses; studies like Kim and Kiaer’s (2021) focused on the case of Korean filmic discourse. Bohnemeyer et al. (2007, p. 496) further proposes that ‘Given this intralanguage variability, we may expect a high amount of crosslinguistic variation in event representations’; K-SFDRS has the potential to approach this variability in foodscaping.

An analysis grounded in the original cultural context of a discourse is very important, especially for newcomers/non-natives (both conducting and reading) analysis of global foodscapes. Since SFDRS derives from SDRT (Asher and Lascarides, 2003), which was developed for the English language, there is much that does not translate and requires recognition of the Korean configuration of multimodality in order to make sense of discourses. This brings us to a matter of the utmost importance when analysing discourses of the Other: Interpretation and translation are the same (Gadamer, 1975, p. 365; Koller, 1987, p. 51; Bühler, 2002). This means that any act of interpretation, but especially those made of modalities and contexts foreign to the interpreter at a societal ‘level of culture’ (House, 2002) such as at a national level, are an act of translation. This means that researchers must bridge the chasm between linguistic systems and cultural differences that otherwise make their analysis null and void and the use of the artefact pointless, since it is these ‘differences’ that give cultures their ‘singularity’ (Deutsch, 1966, p. 75) and that should be the very focus of cultural translation (Bhabha, 1994). In short, Korean language and culture cannot be analysed through Western European scopes of reasoning (Hong, 2009; Kim and Kiaer, 2021; Kiaer, 2022; Kim, 2022, 2024). There is much documentation of this by researchers across the realms of translation (Bassnett and Lefevere, 1995), cultural studies (Bhabha, 1994), linguistics (Venuti, 2009; Kiaer, 2019), and film studies that deal with multimodality and discourses as we do here (Higson, 2000; Kim, 2006). Kaplan (1993, p. 9), for instance, comments on the limitations of analysing Chinese films, stating ‘cross-cultural analysis is difficult: It is fraught with danger. We are either forced to read works produced by the Other through the constraints of our own frameworks/ theories/ ideologies; or to adopt what we believe to be the position of the Other – to submerge our position in that of the imagined Other.’ Similarly, Matron (2010, p. 36) in analysis of Korean film as a West German researcher, states

‘[…] it is still important to keep in mind the position that is taken by the author. In this article, I drew a line connecting two movies from two very different cultures while always maintaining my own West German point of view. It is obvious that within the limited context of this study it is not possible to undertake a deeper comparison of the movies regarding diverging filmic and narrative traditions and the applicability of symbols specific to the respective culture.’

Willemen (2006, p. 35) argues that this gap between researcher and film must be accounted for, or otherwise conform to the cultural practices of the researcher:

‘If we accept that national boundaries have a significant structuring impact on national socio-cultural formations […], this has to be accounted for in the way we approach and deal with cultural practices from “elsewhere.” Otherwise, reading a Japanese film from within a British film studies framework may in fact be more like a cultural cross-border raid, or worse, an attempt to annex another culture in a subordinate position by requiring it to conform to the readers’ cultural practices.’

If foodscaping, then, is to be undertaken by researchers non-native to a particular environment, it is crucial that processes are put in place to ensure cultural differences are taken into account such that specificity and primacy of the source culture is maintained. As per Willemen, it is unethical, not to mention pointless, to approach other cultures from one’s own cultural perspective. Following Eurocentric traditions to address Asian artefacts is akin to analysing a Western adaptation rather than the original text itself. K-SFDRS offers researchers the opportunity to apply a logical framework, grounded in the socio-pragmatics of Korean language and culture, where the gap between Korean and Western scopes predominantly resides, to Korean film so as to facilitate an unbiased understanding of the conventions and meanings made therein. SFDRS is developed to draw discourse structures based on how multimodality ‘makes sense.’ Hong argues that ‘Confucianism is the “common sense” that permeates all kinds of Korean social interactions’ and in order to understand Korean communication, it is Confucian reasoning that has been argued needs developing into a ‘functional and comprehensive tool’ (Hong, 2009, p. 5–7). Kim (2022) builds upon this by developing K-SFDRS with Korean Confucian socio-pragmatics, which constitute a significant, although not sole, influence on Korean interpersonal relations. For a more in-depth discussion of K-SFDRS and its importance to understanding Korean film, we direct readers to Kim (2024).

1.3.5 Event segmentation

Another aspect of SFDRS that we believe to hold particular potential for foodscaping analysis lies in the fact that the pre-existing SDRS methodology (Asher and Lascarides, 2003) was developed using Event Segmentation Theory, enabling its application to multimodal narrative discourses in film. Event segmentation theory applies not only to film, where there have been considerable studies, Song et al. (2021) and the earlier Zacks (2010) to name a few, but also to real-life information processing. In his delineation of the architecture of Event Segmentation Theory, Zacks (2020, p. 42) explains that ‘people can segment ongoing activity reliably with virtually no training. This seems to be picking up on something that is just a natural part of the observing activity.’ Some researchers have described this interpretation of events as a constant construction of narratives. Song et al. (2021), for example, state:

‘We make sense of our memory and others’ behaviour by constantly constructing narratives from an information stream that unfolds over time. Comprehending a narrative is a process of accumulating ongoing information, storing it in memory as a situational model, and simultaneously integrating it to construct a coherent representation. Forming a coherent representation of a narrative involves comprehending the causal structure of the events, including the causal flow that links consecutive events or even a long-range causal connection that exists between temporally discontiguous events.’

Thus, the event segmentation inherent to the (K-)SFDRS methodology gives it potential to accurately analyse the information processing by actors in real-life interactions over food. The significance of segmentation specifically to cross-cultural interpretation has also been demonstrated by Kim (2024 forthcoming; Kim, 2022) in the Korean context. Kim (2022) found that socio-pragmatic primitives are used to infer meaning, and that there is an effect on event segmentation as a result when drawing SFDRS. Event-related potential (ERP) studies on the pragmatic processing of Korean honorifics in the brain have shown that when honorifics are misaligned, the N400 effect occurs, signalling pragmatic mismatches. N400 forms part of the common electrical brain activity observed in response to a variety of meaningful and potentially meaningful stimuli (Kiaer et al., 2022). The same N400 effect has been found to occur in response to modulations in film editing (Sanz-Aznar et al., 2023). As Kim (2022) argues, given that stimuli evoke specific functional reactions in an organ or tissue, there is potential for Korean socio-pragmatics (i.e., honorifics) to be determinants of how Koreans segment ‘meaningful events,’ and thus how discourses in Korean contexts – such as the Korean food environment we examine in this chapter – are understood by Koreans. A related study of Japanese language processing (Cui et al., 2022) is, since among East Asian languages Japanese is the most similar socio-pragmatically to Korean (Kiaer, 2018), ‘still highly relevant here’ (Kim, 2022). The study by Cui et al., which looks into functional magnetic resonance imaging, examines the neural correlates of honorific agreement processing mediated by socio-pragmatic factors in the Japanese language. This study demonstrates that socio-pragmatic factors, such as social roles and language experience, could be key influences in language processing, and demonstrates that social cues, such as social status, ‘trigger computation of honorific agreement’ (Cui et al., 2022, p. 1). This is to say that honorifics register as feature changes as encountered by actors in cultures that employ them. Therefore, the consideration of Korean socio-pragmatics by K-SFDRS fully takes account of their importance in event segmentation and, in turn, the discourses present and how they are understood.

1.4 Conclusion to the introduction

In short, the ability of K-SFDRS to engage with event segmentation according to uniquely Korean socio-pragmatic factors, identifying those which are most salient to a given interaction, gives it potential as a useful tool in understanding Korean communication and meaning-making within foodscapes. It incorporates both ‘obvious’ and ‘obscure’ meanings and lays them bare to both the Korean and non-Korean researcher and reader. As detailed above, this event segmentation is as relevant to spontaneous communication as it is to edited filmic discourse, thus making the principles of K-SFDRS transferable to videographic evidence of live foodscapes. As Kim (2022) states of K-SFDRS:

‘The approach suits the ambiguity encountered in Korean socio-pragmatic communication in filmic discourse, which is often subtle and requires a socio-pragmatic sensitivity that is particular to Korean interpersonal relations, through which clear dependencies of socio-pragmatic relevance between inferences can be identified. This means that the relational structure that holds the socio-pragmatic expressions can be as important for making inferences of segments as the verbal and non-verbal referents that they contain.’

2 Step-by-step guide

For this pilot, video data was collected at a barbeque restaurant in South Korea. The restaurant has both inside and outside seating areas and serves a variety of sliced raw meats (mostly pork and beef, but also chicken) that patrons then cook themselves on coal grills built into the tables. Among the four tables included in our recording, we have chosen table two, situated in the outside eating area, as our main example; the patrons of table two are two Korean men. This section of the paper uses this example to guide how the video recording and informal on-site transcriptive notes of a foodscape are transferred into a formal description.

2.1 Data collection

In order to apply (K-)SFDRS to foodscaping, an audiovisual recording is taken, turning the foodscape experience into a piece of audiovisual material, akin to the film scenes to which (K-)SFDRS is designed to be applied, from which modalities may be transferred into logical forms. The format of the video is not dissimilar from food ‘vlogging,’ in which a patron records themself, their fellow diners, surroundings, dishes, and more in the process of eating, discussing the food, and interacting with people and objects in the wider food environment. Some of the stills from this recording have been inserted into the box notation of logical forms to aid in our demonstration, as Wildfeuer (2014) and Kim (2022, 2024) also do. Please note that in these stills, members of the public have had their faces blurred to maintain anonymity.

Since foodscaping intends to capture and analyse an experience, not just videographic materials, informal fieldnotes on multimodal happenings should also be made by the researcher during and after filming. This intends to capture as much of the modal interplay as possible (for example, noting down smells, tastes, sounds) beyond just that which is apparent from the audiovisual recording alone. These notes should include the point in time at which each happening occurs to facilitate their alignment with the final recording.

2.2 Informal transcription

The video footage is then reviewed several times and a comprehensive informal transcription completed. This notes down all multimodal instances, such as dialogue, activities, and gestures, in the order in which they occurred. This informal transcription brings together chronological instances apparent in the video footage as well as those from the researcher’s fieldnotes. This process involves several rewatches of the footage and constant review and updating of the transcription; through multiple viewings of the footage, the consequential relations between the multimodal inferences become increasingly apparent.

The nature of the informal transcription process, being an early stage of analysis, requires the researcher to begin by writing down as much modality as they can recognise; this list will be narrowed down to the most salient elements in the latter stages. The following excerpt (Excerpt 1) is taken from the informal transcription of the events at and surrounding Mr. A and Mr. B at table two. Some of these modalities occurred simultaneously. Only dialogue and gesture are presented in linear order. Further, the fieldwork researcher’s informal transcription notes have been merged with this in order to include smell and touch where applicable.

EXCERPT 1

Hot but not humid (touch)

Rain (touch, sound, visual)

Sundown (visual, smell)

Stainless steel cups and water bowls (visual)

Grilled meat (smell and visual and sound)

Mr. A turns grilled meat (visual)

Meat sizzles (sound)

Fish from nearby stall selling seafood (smell and visual)

Mopeds slowly driving through (sound and visual)

Staff on stalls working on the street (sound and visual)

People shuffling by (sound and visual)

People holding umbrellas (visual)

People in suits passing through (visual, sound)

Delivery men passing through (visual, sound)

Servers in uniforms (visual)

Mr. A: “Yeogi doenjangjjigae hana” (여기 된장찌개 하나…) ‘One doenjang jjigae [soybean soup] over here… [indecipherable words]

Server: “Honja deusigeyo?” (혼자 드시게요?) ‘Is the doenjang jjigae [soybean soup] for one person?’

Mr. A: [Indecipherable words]

Mr. B: Eats from one of the side dishes

Mr. A: “Ani, ani, ani” (아니, 아니, 아니) ‘No, no, no’

Mr. A turns meat on the grill

Woman working at stall in background (visual)

Constant hum of unknown voices in the background (sound)

People holding umbrellas (visual)

Mr. A adds more meat to grill and turns it over (visual)

Meat sizzles (sound)

Server returns and serves doengjang jjigae [soybean soup]

Another server walks by

Mr. A: “Nae nae” (네 네) ‘Yes yes’

Mr. A passes tray back to the server

Mr. A: “Oh igeot, igeot, igeot” (Oh 이것, 이것, 이것) ‘Oh this, this, this’

Server receives scissors, bows, and leaves

Mr. A: “Joesonghae kimchi jom…” (죄송해 김치 좀…) ‘Excuse me, a little kimchi [fermented cabbage side dish] perhaps…’

Server: “Oh yea yea nae” (Oh 예 예 네) ‘Oh yes, yes, yes”

2.3 Identify socio-pragmatic expressions

The informal transcription is then examined for socio-pragmatic expressions. This helps to find direction in the analysis, since it is these expressions which provide clarity on the meaning of Korean multimodality (Kim and Kiaer, 2021; Kim, 2022, 2024), which we hypothesise in this pilot can then be linked to relevant Korean-specific discourses. Continuing with the same excerpt, the following example (Excerpt 2) shows the identification of socio-pragmatic expressions in the verbal language, non-verbal gestures, and in the ‘food language’ (Kiaer et al., 2024)

Figure 1. Kim’s (2022) transcription model implemented before developing clusters.

EXCERPT 2

Mr. A: “Yeogi doenjangjjigae hana” (여기 된장찌개 하나…) ‘One doenjang jjigae [soybean soup] over here… [indecipherable words] (informal speech style, speaking to much younger man)

Server: “Honja deusigeyo?” (혼자 드시게요?) ‘Is the doenjang jjigae [soybean soup] for one person?’ (formal speech style, speaking to much older man, and customer)

Mr. A: [Indecipherable words]

Mr. A: “Ani, ani, ani” (아니, 아니, 아니) ‘No, no, no’ (informal speech style, one soup to share suggests intimacy between the patrons)

Mr. A turns meat on the grill (would be submissive if the second man at the table wasn’t also doing so and if gestures from both didn’t suggest equality)

People with umbrellas walk by (no socio-pragmatic value – atmospheric)

Mr. A adds more meat to grill and turns it over

Meat sizzles

Server returns and serves doengjang jjigae [soybean soup]

Another server walks by

Mr. A: “Nae nae” (네 네) ‘Yes yes’ (formal speech style)

Mr. A passes tray back to server. (man passes with one hand because he’s so much older and a customer, and server receives with two because he is much younger and a server – age is main factor)

Mr. A: “Oh igeot, igeot, igeot” (Oh 이것, 이것, 이것) ‘Oh this, this, this’ (informal speech style)

Server takes scissors, bows, and leaves. (men don’t bow back because they are customers and much older) [paying further attention to the socio-pragmatics of the man’s gestures, now his avoidance of eye contact can be contextualised and recognised as salient too, as can both the supporting of his right arm with his left hand when reaching across the men and his reluctance to do so often, be identified though partially concealed from view]

Mr. A: “Joesonghae kimchi jom…” (죄송해 김치 좀…) ‘Excuse me, a little kimchi [fermented cabbage side dish] perhaps…’ (informal speech style)

Server: “Oh yea yea nae” (Oh 예 예 네) ‘Oh yes, yes, yes” (formal speech style)

With the socio-pragmatic information taken from this informal transcription alone, we can ascertain the close intimate relationship of the two patrons dining at table two, which is important for discourses related to anju (안주, ‘food consumed customarily with alcohol’) and male bonding (Kiaer and Kim, 2021) as we shall go on to show, and the appropriate behaviour of the server (Figure 1).

2.4 Review and refine transcription

The referents seen in Figure 2 in logical forms , , , and , were inferred having collected the salient modalities from the informal transcription. Table 1 shows the modalities in their entirety assigned to Mr. A and Mr. B at table two. We have included referent and cluster form labels so that referents can easily be tracked to the graphical representations of logical forms that will follow.

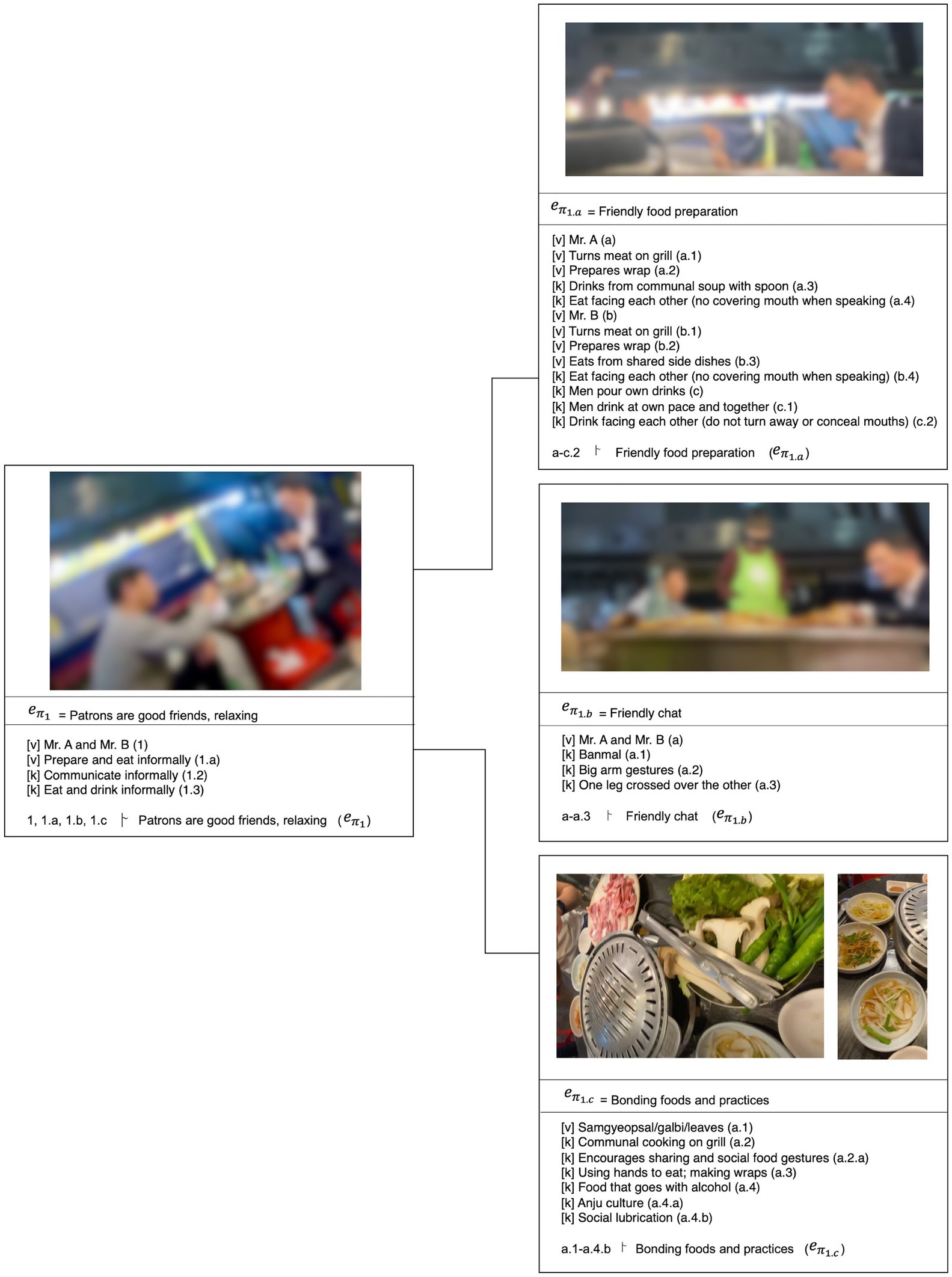

Figure 2. The cluster structure drawn of table two; the umbrella logical form ‘Patrons are good friends, relaxing’ (left) and the three finer-grained logical forms ‘Friendly food preparation’, ‘Friendly chat’, and ‘Bonding foods and practices’, that can be constructed from.

2.5 Draw logical forms

Drawing the logical forms themselves, we follow Kim’s (2022, 2024) presentation, however, unlike Kim, Korean gestures and speech styles have not been abbreviated in order to give as much clarity as possible in this early pilot. We do include the hierarchical relations between communicators, using < to indicate that the former person is junior to the latter (e.g., Person 1 < Person 2; person 1 is junior to person 2), and the reverse > (e.g., Person 1 > Person 2; person 1 is senior to person 2). This equation then specifies the type of seniority. (P) stands for ‘position.’ A senior in position can, and does in our analysis, refer to the senior position of a restaurant patron to service staff. (A) stands for ‘age,’ so if Person 1 were visibly senior in age, the hierarchical relation ‘Person 1 > Person 2 (A)’ would be attached to them within the logical form. In the logical form, salient modality is listed in the central area of the box and marked with [v] for ‘visual,’ [a] for ‘audio,’ or [k] for ‘Korean’ when Korean socio-pragmatic primitives are interpreted (e.g., speech styles, certain socio-pragmatic gestures, and the hierarchical relations previously mentioned) or other cultural communications. These ‘referents’ are also labelled, with the same labels that appear in the formula of the defeasible eventuality (the meaning interpreted from those multi-modal interactions), followed by the defeasible eventuality symbol, and finally the inferred meaning. Figure 3 shows a logical form in K-SFDRS format, created using the analysis presented in this chapter.

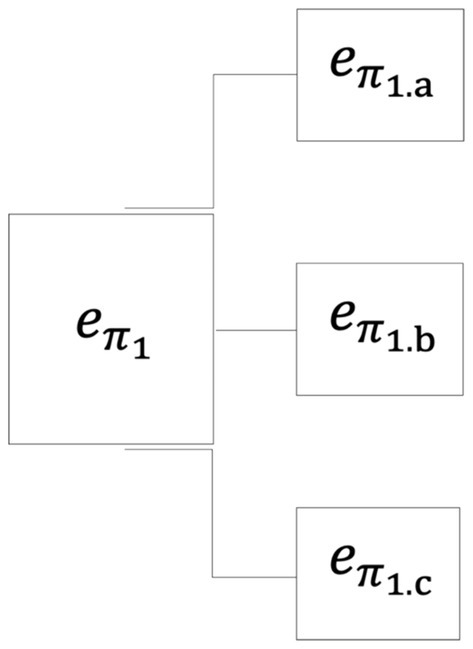

Figure 3. Cluster model for hierarchising spontaneous simultaneous multimodality using as an example.

2.6 Organise logical forms and clusters

In the first instance, the above list of referents was considered within the scope of a single logical form, all of the components constructing a single meaning, but the referents are too numerous, and also offered separate, subtle contributions to the information inferable. To a degree, all referents share connections or commonalities, so it is possible to summarise (or rather simplify) what they amount to as a communication. This is because of the alignment of honorifics found in the verbal and non-verbal communication of Koreans (Brown, 2013; Kiaer and Kim, 2021; Kiaer, 2023), and the rigidity within which this is upheld, and the meaning potentials expressed if not (e.g., misalignment can be used to insult), that ultimately point to interpersonal relations and the nature of the interaction being observed.

It was decided early on that the pilot would need to be conducted without traditional discourse relation structures, and thus logical forms would be the focus. To understand how segments unfold in discourse, and apply discourse relations to the transcription, would require either a narrative or process to be observed or, where no narrative exists, a new conceptualisation of a narrative or process to replace it. It was thus determined that in the confines of this paper it was more prescient to focus on how the first granular level of K-SFDRS would work on independent instances of food consumption. However, this left another problem: several logical forms would be produced with an array of possibilities for interpretation, but they would be without the discourse relations which control said interpretation by highlighting whether they do or do not make sense. Fortunately, the process of creating logical forms itself granted the development of a method of organisation for the logical forms drawn from spontaneous, simultaneous multimodal discourse. The resulting structure is an umbrella logical form divided into various smaller logical forms, each of which represents a part of the main form. We term these ‘cluster structures.’ This approach does not require discourse relations, but rather transcribes how various meaning potentials are inferred by certain multimodal interactions and culminate ultimately in a particular aspect of the environment.

Figure 3 shows how is divided, exposing a cluster of smaller logical forms, each of which possesses its own meaning potential and disciplinary routes through which it may be understood. See Figure 2 to view the complete logical forms of this cluster structure of .

This development came about as it was observed that, when corroborative modalities could be identified working together, their unanimous meaning potential made them the salient modalities. Further, because of how socio-pragmatic rules limit the options for meaning potentials in Korean multimodal communication, as does socio-pragmatic alignment (Kiaer and Kim, 2021) and socio-pragmatic feature changes (Kim, 2022, 2024), meaning potentials were no longer elusive once these modalities could be identified. Logical forms could then be refined in order for them to ‘make sense’ both on Wildfeuer’s (2014) and Kim’s (2022, 2024) terms. Through this process of drawing logical forms, reviewing footage, and analysing alignment and consistency in expressions, not only is it possible to refine the referents listed in the box notations, but to refine the defeasible eventualities, and in some cases remove or merge logical forms altogether. Both Wildfeuer (2014) and Kim (2022, 2024) write on this process of revision and tweaking that occurs naturally when building (K-)SFDRS; the only difference here is simply that this occurred at the level of logical forms only. Each type of information communicated by certain sets of modalities could then be separated into logical forms, and the logical forms clustered in the foodscape under analysis.

It is possible, with some consideration, to determine a set of categories that allow the divisions which facilitate clusters to take place, according to the corroboration of given modalities through which certain intentions or functions can be reasoned. For example, food gestures like ‘drinking facing each other,’ ‘not concealing mouth when eating/drinking,’ ‘pouring own drink,’ and ‘drinking at own pace’ are all expressions of informality and, consequentially, intimacy. The same is true of similarly informal and intimate verbal language and non-verbal gestures such as speaking in ‘banmal’ (an informal speech style) and ‘big arm gestures’ that in formal or distant relations would be considered inappropriate. Eating meat with soju (a Korean spirit) is a social lubricant or setting for informal and intimate socialising – either to build intimacy in a relationship or for relationships in which this is already established. Both are linked by intimacy and informality, however, one a set of modalities (banmal, and pouring one’s own drink, for example), while meat and soju are rather a well-suited setting for intimate and informal socialising and bonding. Please see Kiaer and Kim (2021, 2024), Kiaer et al. (2024), and Kim (2022, 2024) where these expressions are covered extensively.

The umbrella logical form drawn up in this case was ‘Patrons are good friends, relaxing.’ This defeasible eventuality was inferred by both the socio-pragmatics of modalities employed by the two patrons, and their alignment and consistency. Both men used informal speech styles and gestures; even their postures, sitting with one leg crossed over the other, facing each other when downing shots of soju, neither covering their mouth when eating and talking at the same time (Kiaer and Kim, 2021, 2024). Socio-pragmatic expressions out of alignment were purposeful and did not change this consistency. For instance, the men would take turns pouring drinks for each other on occasion, but this is a gesture that between friends is a way of making a fuss or showing care and not submissive (Kiaer and Kim, 2021), and combined with pouring drinks for oneself and one-handed, which would not be acceptable by a junior to a senior, does not nullify its meaning. Another example is of how both men take turns tending to the meat on the grill; had one of the men been junior to the other then he would have solely or dominantly tended to the meat, and the elder tending to the meat would have been an exaggeration of care, which could be identified in its orchestration with other modalities such as back patting or saying ‘Eat meat!’ the Korean phrase Geogi meogo! (‘고기 먹어!’) that are also ways of showing care and therefore would support this inference.

This logical form can then be broken down into a ‘cluster’ in which finer grained meanings are defeasibly reasoned as segments constructing Patrons are good friends, relaxing; with modalities divided into groups according to their corroboration in meaning potential. As such, the notable long list of modalities found to be salient in the inference of Patrons are good friends, relaxing can be lessened in preparation for later discussion of discourses to be more specific.

Figure 2, the umbrella logical form and the cluster of logical forms and are the final logical forms in the cluster model developed during this pilot. They reflect the hierarchy of forms that combine simultaneously in spontaneous discourse. Eventuality labels (e.g., ) were applied with the umbrella logical form being a number (e.g., 1), and those that cluster to form said umbrella being labelled with a letter in addition to the respective number (e.g., 1.a, 1.b, 1.c, etc.). Further, the referents in umbrella logical forms are generalised (e.g., ‘informal communication’), while in the appropriate logical form from the cluster specified examples will be listed (e.g., ‘banmal speech style,’ ‘one-handed giving/receiving’). Each logical form within a given cluster was dedicated to one of the generalised modalities in the umbrella logical form which would be elaborated on within the logical form, and as such the logical form was labelled with the same referent label as the generalised modality, making the structure explicit.

3 Analysing the notation

Within the ‘friends eating’ cluster (the full version of the logical forms produced in the preceding step-by-step section), several themes emerge that are ripe for interdisciplinary analysis. For the most part, these centre around the nature of Korean barbecue as a tool for socialisation and social lubrication, largely through alcohol drunk alongside the meal, as well as the reduction of politeness forms in interaction that fosters intimate friendship between social equals. Here we will give examples of avenues down which interdisciplinary researchers may go when expanding the SFDRS notation into a fully-fledged foodscaping analysis. We have labelled these avenues by the key theme that becomes apparent through the K-SFDRS analysis and suggest potential further avenues of investigation or elucidation scholars belonging to various disciplines may take.

3.1 Friendship relations

Spoken Korean is highly mediated in terms of formality, putting a strong focus on and reinforcing a complex structure of social hierarchies (Kiaer and Kim, 2021). This permeates Korean speech in every situation, and determines the way in which Koreans speak to one another every minute of every day; for example, one must be aware of which register to use when talking to one’s boss, mother, older sibling, younger sibling, a friend one has just met, or a friend one meets every day and is close to, and how each one may differ from another in any given situation (Lee and Robert Ramsey, 2000, p. 267–272; Brown and Winter, 2019). Despite frequently entrenching hierarchies in a manner that keeps individuals emotionally distant, this feature of the Korean language is also an important tool in bond-building between individuals; deeming one’s relationship sufficiently intimate to transfer from a formal register to a more casual one can assert intimacy, friendship, and trust between individuals, provided it is instigated by the more senior of the pair or group and in an appropriate situation (Choo, 1999; Lee and Robert Ramsey, 2000).

A foodscape such as the one at the heart of our analysis, a barbecue restaurant of the most casual kind, by its nature encourages this kind of linguistic mediation from its patrons. The majority of the people eating in the restaurant on the evening in question were groups of close colleagues or young people in large friendship groups. In this example cluster, much of the salient multimodal referents are predicated on the manner in which they speak with one another, which can be categorised as ‘informal’ according to Korean speech registers. Through actions such as talking in ‘banmal,’ gesturing in an animated way with one’s hands, and using typically ‘male’ registers of speech, the two friends are entrenching their close relationship with one another further throughout their meal (Choo, 1999; Lee and Robert Ramsey, 2000; Kiaer and Kim, 2021, 2024).

A researcher interested in the linguistic aspect of friends eating a meal may point towards this particular piece of notation in as data-driven proof of the salience of said linguistic elements in the foodscape in question. Use of banmal and its consistency are shown in the notation to build significantly towards the resulting characterisation of the exchange as ‘Patrons are good friends, relaxing.’

Segment carries the same themes of informality, but rather than just speech it demonstrates how the various referents contribute to the defeasible eventuality ‘Friendly food preparation.’ This demonstrates the gestural and food-specific dimensions of informal Korean linguistic analysis, thereby opening up the hypothesis that the communal cooking and eating processes in which patrons engage in this foodscape specifically encourages social bond-building. For example, Mr. A takes food from a communal stew with his spoon; it is customary for a Korean meal to involve an individual bowl of soup or stew per diner, so in this instance the sharing of one bowl indicates the interlocutors’ intimacy (Kiaer et al., 2024). Additionally, it is considered polite to cover one’s mouth when speaking, an act of modesty and moderation when animated, in particular when laughing or smiling; an action in which neither of the men in this segment engage (Kiaer and Kim, 2021). Far from indicating impoliteness or rudeness to one another, however, the defeasible eventuality of this segment is ‘Friendly food preparation.’ Thus, we see how, with the correct relationship and level of intimacy, ‘impolite’ gestures such as those shown in and foster and reassert the close level of friendship between interlocutors; something which is facilitated by anju (Brown and Winter, 2019). This, then, indicates the foodscape in question, and perhaps, as an extension, barbecue restaurants in general, as a space which establishes an atmosphere in which informal behaviours are acceptable, even reaffirming the nature of the group as intimate friends.

3.2 Alcohol as a social lubricant

In c, c.1, and c.2 of we can observe how soju is combined with the meal of Korean barbecue. A distilled alcoholic beverage which has been produced on the Korean peninsula from as early as the thirteenth century, soju is a very common beverage enjoyed by Koreans particularly as an accompaniment to communal meals such as Korean barbecue (Park, 2021). Although soju can range anywhere between about 10 and 50 percent ABV, lower alcohol soju ranging between 12 and 16 percent have become more frequent in the past few decades, making them akin to a wine in alcoholic terms (Park, 2014). Served to the table in cold bottles to be distributed into small glasses, frequently ‘shot’ sized with a 50 mL capacity, soju retains its cool temperature when being drunk in the hot atmosphere of a busy barbecue restaurant. The cool temperature and refreshing, slightly sweet, taste of soju makes it the perfect pairing to salty, fatty, caramelised barbecue meats (Yoon, 2022).

The importance of soju as a social lubricant, and the established norm in Korean culture of eating whilst drinking alcohol, further cements the success of soju and barbecued meat as a successful pairing (Ko and Sohn, 2018). In South Korea, the drinking of alcohol is most often combined with the eating of food, which may range anywhere from small snacks taken from packets, through a selection of cooked dishes, to full-blown meals featuring meat, stews, and rice; it is rare to drink at an establishment without some kind of food on the table to accompany it (Lee, 2011). The culture of anju has a long heritage in Korea, stemming centuries back into the dynastic periods of the peninsula, and is a tradition which endures amongst Koreans today, both young and old (Pettid, 2008).

In , we particularly see how cultural roles associated with sharing alcohol, much like those of formal speech patterns and gestural behaviours, can be broken down and made more casual in order to assert close, typically male, friendships (Ko and Sohn, 2018). In , we see both Mr. A and Mr. B pour soju from the communal bottle into their glass and drink at leisure. Where this might seem a relatively standard practice from a non-Korean perspective, it is in fact notable that each man serves themselves and drinks as and when they choose. When socialising with others, particularly those of different social standings (such as seniority of work role, age, family position, etc.), it is common practice for the younger of the pair or group to serve others (often following order of seniority) from the shared bottle before they themselves are served by one of the other members of the group, and for everyone to drink at the same time, with juniors being sure to match pace with the more senior members of the group before the process is repeated again (Hines, 2022). It is also standard polite practice to cover one’s mouth or turn away from one’s interlocutors (especially seniors), when taking a sip from one’s drink (Kiaer and Kim, 2024). In contrast to this, the interlocutors in pour their own drinks, take sips of their drinks at their own pace, and drink facing one another without covering their mouths or turning away. Again, we see from the notation in and that such actions, rather than suggesting rudeness, contribute to the ‘friendly’ nature of their food preparation and consumption together.

Researchers of Korean socio-pragmatics may use the above analysis as an opportunity to explain, firstly, the relationships of Korean diners to one another as exemplified in the pouring and taking of drinks. The logical form could serve as a very useful piece of evidence in a comparative exercise with another, perhaps more formal, foodscape featuring both alcohol and a range of ages of participants to better exemplify this element of Korean culture. Food historians may also use the analysis to speak to the pairing of soju with barbecued meat, outlining their history and using the multimodal inferences as evidence to their combination by today’s eaters. Sociologists and gender studies experts may further wish to analyse the interactions in light of notions of ‘masculinity’ associated with both the meat and the alcohol being consumed.

3.3 Eating ‘correctly’

Several elements of the ‘friends eating’ cluster also illuminate the ‘grammar’ of a Korean meal and how this is observed by everyday Korean eaters in the context of a barbecue meal. Firstly, in we observe patron Mr. B prepare a lettuce leaf wrap for eating, in which he takes a piece of meat that has been cooked on the communal grill and, holding an open lettuce leaf in the palm of his hand, wraps it up alongside sauce (assumedly ssamjang (쌈장)), kimchi, and vegetarian banchan (반찬, small side dishes customarily served for free alongside a meal) of his choosing into a bite-sized piece (the main ingredients for this are shown in ). It is a common practice when eating Korean-style barbecue to take green leaves, which is often lettuce but can be any leafy green or a combination thereof and use it to wrap up a small piece of meat in combination with condiments (often a spicy or plain fermented bean paste), banchan, kimchi, or rice before eating in a single bite. When asking a Korean why they prefer to eat their meat as ssam (쌈), literally meaning ‘wrapped,’ they will most likely simply respond ‘because it tastes better’ (Lee, 2016). But this ‘simple’ aspect of taste can be traced back once again to traditional Korean preferences for balance not just across a meal or within a recipe, but in each individual bite. Owing to traditions of Traditional Korean Medicine and Neo-Confucianism, achieving a balance not only of flavours but also of colours, temperatures, and textures, is very important in the construction of a ‘proper’ Korean meal (Pettid, 2008). Indeed, whilst the banchan, condiments, meats, and rice of a Korean barbecue meal demonstrate this balance, they are served in distinct dishes and are cooked separately, making it difficult to enjoy them all together at once, thereby properly savouring their combination and, therefore, the balance of flavours they together achieve. This is where ssam come in – the leafy green is used as a utensil in which the balanced flavours of each element of the barbecue meal can be combined. Researchers with a host of disciplinary backgrounds, including History, Traditional Korean Medicine, and Philosophy, would be valuable in fully unravelling the cultural and historical contexts relevant to this line of enquiry.

During and , we also see the banchan, or ‘side dishes,’ served to every table of diners for free as part of the meal, regardless of their other orders. The banchan served to the tables of the present foodscape are several without being numerous; diners are offered a dish of spicy dressed bean sprouts, shredded cabbage with a sesame dressing, vinegar-dressed greens, and a small side of kimchi. These three dishes are very commonly served at barbecue restaurants such as this one. Banchan, an integral part of any Korean meal, regardless of the price point, mealtime, or situation, serves a multitude of purposes in the Korean meal, but most importantly they balance the meal’s flavour profile, inject crucial vitamins and minerals to the diet, and add colour to the table (Kim, 2020). Banchan is served in small dishes, and it is the norm that diners may ask for a top-up of any given side dish as they eat (Kiaer et al., 2024) – in the foodscape analysis, Mr. A can be seen asking for an additional portion of kimchi. In other foodscapes the authors have observed, however, banchan (for which there is a long history in Korea stemming from royal court cuisine), are offered instead in the form of a self-serve banchan bar (Yeong, 2021). This allows patrons to select their own banchan from an array of options (the authors have observed restaurants offering anywhere between three and nine different side dishes and varieties of kimchi) and bring it to their table, asking only that they leave none at the end of their meal beyond reasonable leftovers. This change in long-standing format of meal presumably stems from economic considerations on the part of the restaurant, particularly following the COVID-19 pandemic and the resulting loss in sales (Lee and Koo, 2023). From an environmental perspective also, although we suspect this to be secondary to economic concerns from the perspective of restaurant owners, offering a lower volume of banchan which patrons may ask to top up should they wish more cuts down on food waste, which is increasingly a hot topic in Korean and global society. Indeed, as with many other elements of this foodscape, we see the realities on a local scale of a changing and shifting global South Korea reckoning with new concerns that appear to clash with traditional practices and expectations. Scholars interested in economics, public health, policy, and sustainability might all fruitfully follow this line of enquiry to develop a foodscaping analysis.

4 Conclusion and further research

In this paper we have outlined the need for a formal logic that can be applied to the multimodal analysis of foodscaping, proposed the use of the logical forms of (K-)SFDRS as a potential tool for this, and demonstrated (K-)SFDRS’s box notation style on a recorded live foodscape, as well as offering analysis of the multimodal strands of analysis and associated discourses that are revealed and structured by the notation. This has been completed using the example of an evening foodscape at a barbeque restaurant in South Korea, which we have anonymised here.

The box notations and their analysis presented here lends a formal method to the understanding of a foodscape, featuring both local and non-local actors, in terms of diverse modalities, enabling the researchers to attach different disciplinary strands and contexts to further explain how certain inferences are produced in the foodscape in question: (1) the foodscape was recorded through informal transcription and audiovisual recording; (2) the data, categorised into ‘clusters’ based on different actors in the foodscape (in this case, tables of diners), was transformed into logical forms using the (K-)SFDRS model of box notation, through which; (3) the clusters were systematically analysed to produce a commentary on the salient multimodal elements that contribute to the inferences of given actors in each cluster, drawing on interdisciplinary discussions to give important context and background to explain how said inferences are ascertained from the associated multimodal influences.

The process of drawing equations, in which various modalities in the food environment possess meaning-making potential and combine to create various inferences, was found beneficial for identifying how certain modes interact to produce inferences, and the many multimodal discourses present in a food environment at a given time; not to mention the multifarious interdisciplinary roots of meaning-making processes that perhaps are not clear on initial inspection to the casual observer. This is because the modalities revealed by the (K-)SFDRS notation to be salient in creating certain meanings can be traced culturally and historically, thereby revealing the value of interdisciplinary analysis in understanding meaning-making processes in food spaces. Under scrutiny, this information then reveals connotations that accompany the local experience, in this case of samgyeopsal eateries in metropolitan spaces in South Korea, and specifically of the case study featured in this paper.

The process detailed in this paper has revealed advantages (both evident and potential), as well as drawbacks (both inherent and open to adjustment) in the use of logical forms of (K-)SFDRS for foodscape analysis. Here we outline these in greater detail.

4.1 Strengths

The ‘cluster’ system developed for the collection of segments into useful groupings has aided in the structure and logical discussion of the foodscape. The clusters allow researchers to focus on certain actors at any one time, essentially using primarily a nonlinear approach so as to deal with associated narratives without being overly dependent on chronology. We propose that cluster structures are ultimately catering formally to the incredibly complex ‘multidimensional maps’ that Doxiadis (2010, p. 81) describes: ‘Narratives flow linearly in time, yet they mediate between worlds that are largely nonlinear: both the world of action, with its manifold possibilities, and our mental models of it are like complex, multidimensional maps, representing not just objects but also relations, in webs of immense connectivity. Narratives by contrast, are like specific paths taken through these worlds — partial, linear views of nonlinear environments’.

The multimodal notation of (K-)SFDRS, through both audiovisual recording and fieldnotes, takes into account all modalities and brings them together as equal participants in meaning-making. This ensures that it is not only the most ‘apparent’ modalities that are taken into account; the researcher must consider every utterance, regardless of modality, as of equal potential importance until the informal transcription is narrowed down to salient modalities.

Using the (K-)SFDRS notation as a basis for discussion and analysis, drawing discussions based on the relevant discipline as they appear, has proved useful in establishing a neutral foundation from which to explore the multifaceted avenues of the foodscape. Further, by identifying pertinent actions (i.e., those which contribute the most to a given inference), the notation ensures that conversation springs only from the multimodal occurrences which result in genuine meaning-making. Thus, the method acts as a great base upon which to build layers of interdisciplinary analysis only when pertinent to the inference at hand, and without relying on a given discipline as ‘prime’ or as the foundation for analysis.

The formal logic of (K-)SFDRS notation contributes to the understanding of how meaning is made through certain multimodal interactions in a way that can be explained to locals and non-locals alike. Our analysis, in particular the table demonstrating knowledge sources, illustrates how using (K-)SFDRS notation enables researchers to clearly align a stimulus with the mode in which it occurs, the inference in which it results, and the knowledge required for actors to reach said inference. This explicitly joins the dots of the meaning-making processes within any given foodscape and for any given actor, clearly exposing the roots of inferences, sparking discussions on the similarities and differences therein, and providing opportunities in which to explain the interdisciplinary background where pertinent.

The production of logical forms facilitates the in-depth review of an experienced foodscape (through both audiovisual recording and defeasible notes made at the time) and their transferal into, firstly, a list of multimodal occurrences and, secondly, logical forms based on their importance and interaction to create meaning. During this paper, we have found the very action of producing logical forms on the part of the researcher to be helpful in attributing inferences (which otherwise rely solely on the researcher’s own intuition) to data-based evidence. As such, the use of (K-)SFDRS in the process of analysing a foodscape helps the researcher to double check one’s own assumptions and intuitive thoughts, cross-referencing them with the salient moments evidenced through the process of producing (K-)SFDRS logical forms.

The appearance of final logical forms in box notation (as well as intermediary stages such as lists of multimodal occurrences if relevant) and umbrella clusters helps the reader of foodscaping outputs to better understand and contextualise the analysis in several ways. Firstly, the description of a foodscape, considering its rich multimodal nature, is a difficult task in the context of an academic paper; word limits are often strict, and the literary language required for description is often undesirable. (K-)SFDRS notation has the potential to overcome this by laying out key multimodal instances (either/both chronological and thematic) for the reader in a concise, objective manner. Secondly, in the process of reading foodscaping analysis, readers are directed repeatedly to different instances of meaning-making as demands the flow of the paper’s argument. As such, logical forms and their labelling are useful as a reference point to which readers may return in order to fully contextualise the referents discussed at points in the argumentation. Lastly, much like the researcher themself, logical forms enable readers to cross-check author assertions with the multimodal evidence to which they pertain, again ensuring that conclusions do not rely exclusively on author intuition.

4.2 Limitations

(K-)SFDRS, owing to its main purpose as film notation, relied most heavily upon audiovisual data as the main source of analysis. Although our implementation of an informal transcription, which foregrounds sensory data, as well as ensuring the researchers personally experience the foodscape whilst recording, has helped to incorporate further non-audiovisual, multimodal aspects into the analysis, further experimentation may be needed to develop a more robust method of incorporating multimodal evidence into the notation.

Following on from Strength 1, we have found clustering a useful tool. Though, as we previously stated and expected given that discourse relations were not able to be applied to logical forms simply, the non-linear aspect has taken precedence. Whilst chronology is not essential in each inference, we would like to develop clusters to engage more actively with linear processes in food consumption, preparation, and etiquette. We believe this would better demonstrate the foodscape as it happens and allow readers to contextualise multimodal inferences better in the process of following the final analysis.

4.3 Further research

The present study only makes the very first inroads into the potential use of (K-)SFDRS methodology in the pursuit of foodscaping projects. Whilst we believe that this methodological paper has proved the potential of the methodology and its strengths and weaknesses, there are several key avenues down which we believe future research could profitably travel to further explore and verify its usefulness.

This paper, due to constraints on length and its methodological nature, does not utilise (K-)SFDRS in the context of a full and proper foodscaping analysis. As such, it cannot definitively evidence the usefulness of the methodology. We propose further studies entirely within the foodscaping methodology which make use of (K-)SFDRS in the initial analysis so as to further investigate its applicability.

We additionally propose that future research employ (K-)SFDRS in foodscaping projects which incorporate authors from various disciplinary backgrounds so as to make the most of the multimodal nature of the logical forms and their ability to serve as a ‘jumping off point’ for multiple disciplinary avenues. Based on disciplinary background, our expertise as authors lends itself to linguistics, multimodality, cross-cultural perspectives, Korean culture, history, and food; as such, these are the topics with which our example analyses most heavily engage. Should researchers who are specialists in Korean agriculture, politics, or economy, for example, employ this methodology, their results might accordingly identify contributions of other modalities to other logical forms. Rather than a hindrance, we see this as mirroring the interdisciplinary nature of foodscaping as an endeavour; interdisciplinary teams of researchers are a benefit, if not an essential, to the aims of foodscaping, and thus the simultaneous use of the (K-)SFDRS method on the same multimodal inferences by researchers with different disciplinary backgrounds is a necessity for the full and proper analysis of a foodscape.

We have discussed how (K-)SFDRS, being developed as a method for film analysis (and therefore relying on strong cinematic narratives), must be altered to fit spontaneous discourse in which purposeful narrative does not exist. As such, discourse relations were not forthcoming in the foodscape analysis presented here, resulting in the original innovation of the cluster notation. However, as outlined in limitation 2, we believe that the logical form clusters would be best complimented with a chronological or relation-based method specifically designed to suit spontaneous discourse. This would enable the true-to-life chronology of the foodscape to be better conveyed to the reader, and, in turn, allow relations to be drawn between occurrences in a manner more akin to the original SFDRS methodology. For this, a further novel notation style must be developed; this is an important task that we must leave to future studies.

As scholars with backgrounds in Korean studies, and using the K-SFDRS system developed by Kim (2022, 2024), this paper necessarily focuses on the Korean context for its example analyses. Part of the benefits of K-SFDRS over SFDRS evidenced in this paper is its specificity to the Korean language and socio-pragmatic nuances, both in reference to native actors and to the interactions of non-native actors within the context of a South Korean foodscape. As such, we believe that the development of specific local SFDRS systems is crucial to this method’s success in further international endeavours. We encourage our colleagues in Japanese studies to consider J-SFDRS, Chinese studies to consider C-SFDRS, etcetera, until a wealth of international logical forms can be drawn from to facilitate nuanced and accurate cross-cultural foodscaping analyses.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

LK: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. NC: Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Asher, N., and Lascarides, A. (2003). Logics of conversation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bassnett, S., and Lefevere, A. (1995). “General editors’ preface” in The Translator’s invisibility: a history of translation. ed. L. Venuti (London: Routledge).

Bateman, J. A., and Wildfeuer, J. (2014). A multimodal discourse theory of visual narrative. J. Pragmat. 74, 180–208. doi: 10.1016/j.pragma.2014.10.001

Bohnemeyer, J., Enfield, N. J., Essegbey, J., Ibarretxe-Antunano, I., Kita, S., Lüpke, F., et al. (2007). Principles of event segmentation in language: the case of motion events. Language 83, 495–532. doi: 10.1353/lan.2007.0116

Brown, L. (2013). ‘Mind your own esteemed business’: sarcastic honorifics use and impoliteness in Korean TV dramas. J. Politeness Res. 9, 159–186. doi: 10.1515/pr-2013-0008

Brown, L., and Winter, B. (2019). Multimodal Indexicality in Korean: ‘doing deference’ and ‘performing intimacy’ through nonverbal behavior. J. Politeness Res. 15, 25–54. doi: 10.1515/pr-2016-0042

Bühler, A. (2002). “Translation and interpretation” in Translation studies: perspectives on an emerging discipline. ed. A. Riccardi (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Calway, N., Loli, K., and Robert, W.-C. (2025). Foodscaping the Seoul metropolis: foodscaping Korea. London: Bloomsbury.

Cui, H., Jeong, H., Okamoto, K., Takahashi, D., Kawashima, R., and Sugiura, M. (2022). Neural correlates of Japanese honorific agreement processing mediated by socio-pragmatic factors: an FMRI study. J. Neurolinguistics 62:101041. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroling.2021.101041

Deutsch, K. (1966). Nationalism and social communication: an inquiry into the foundations of nationality. Massachusetts: Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press.

Doxiadis, A. (2010). Narrative, rhetoric, and the origins of logic. Storyworlds J. Narrat. Stud. 2, 79–99. doi: 10.5250/storyworlds.2.1.79

Gerhardt, C., Frobenius, M., and Ley, S. (2013). “Culinary linguistics: the Chef’s special” in. eds. C. Gerhardt, M. Frobenius, and S. Ley (Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company).

Higson, A. (2000). “The limiting imagination of National Cinema” in Cinema and nation. eds. M. Hjort and S. MacKenzie (London: Routledge), 63–87.

Hines, Nick . (2022). What is soju? Everything you need to know about Korea’s national drink. Available at: https://vinepair.com/articles/soju-koreas-national-drink/#soju-how

Hong, J. O. (2009). A discourse approach to Korean politeness: towards a culture-specific confucian framework. Nottingham: Nottingham Trent University.

House, J. (2002). “Universality versus culture specificity in translation” in Translation studies: perspectives on an emerging discipline. ed. A. Riccardi (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 92–110.

Kaplan, E. A. (1993). “Melodrama / subjectivity / ideology: western melodrama theories and their relevance to recent Chinese cinema” in Melodrama and Asian Cinema (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 9–28.

Kiaer, J. (2019). “Translating invisibility: the case of Korean-English literary translation” in Translation and literature in East Asia. 1st ed. Eds. K. Jieun, G. Jennifer, and L. Xiaofan Amy(London: Routledge).

Kiaer, J., and Kim, L. (2021). Understanding Korean film: a cross-cultural perspective. 1st Edn. London: Routledge.

Kiaer, J., and Kim, L. (2024). Embodied words: a guide to Asian non-verbal gestures through the Lens of film. Oxon: Routledge.

Kiaer, J., Kim, L., and Calway, N. (2024). The language and food through the Lens of East Asian film and dramas. London: Routledge.

Kiaer, Jieun, Lee, I., and Brown, L. (2022). An ERP study on the pragmatic processing of Korean honorifics and politeness. (Forthcoming).

Kim, S. K. (2006). Renaissance of Korean National Cinema as a terrain of negotiation and contention between the global and the local: analysing two Korean blockbusters, Shiri (1999) and JSA (2000). Available at: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/‘-Renaissance-of-Korean-National-Cinema-’-as-a-of-%3A-Kim/e03e2065951c51e9ed89ba78bf6c30fa48c6e87f#citing-papers

Kim, Eric . (2020). A spread worthy of loyalty. The New York Times. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/28/dining/banchan-recipes.html

Kim, L. (2022). A theory of multimodal translation for cross-cultural viewers of south Korean film. University of Oxford.

Kim, L., and Kiaer, J. (2021). “Conventions in how Korean films mean” in Empirical multimodality research. eds. J. Wildfeuer, J. Pflaeging, and J. Bateman (Berlin: De Gruyter), 237–258.

Ko, S., and Sohn, A. (2018). Behaviours and culture of drinking among Korean people. Iran J. Public Health 47, 47–56.

Lee, Cecelia Hae-Jin . (2011). Food and drinks the Korean way. Available at: https://www.latimes.com/food/la-xpm-2011-may-26-la-fo-anju-20110526-story.html