- 1Faculty of Modern Languages and Communication, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Serdang, Malaysia

- 2School of Foreign Languages, Zunyi Medical University, Zunyi, China

Translating cultural references in tourism materials is pivotal in bridging cultural gaps and facilitating cross-cultural communication. Despite the escalating demand for accurate translation, no research exists to address the losses in cultural connotations and their impact on semantic accuracy in Chinese-English cultural reference translation within Lonely Planet’s travel guides. This research seeks to fill this gap, specifically focusing on Beijing, Shanghai, and Sichuan destinations. The objectives are as follows: 1) to identify the types of cultural connotation losses in the English translation of Chinese cultural references; 2) to examine cultural-related semantic losses, considering instances where cultural connotation losses lead to partial or complete semantic losses; and 3) to elucidate the translation decisions (both macro and micro levels) implications on the culturally based semantic losses. A qualitative-descriptive approach forms the foundation of this research. The findings revealed seven types of cultural connotation losses, with partial semantic losses predominant. Applying Venuti’s domestication and foreignization, the results also uncovered a strong inclination toward foreignization, emphasizing the strangeness inherent in the source culture is intensified. These findings contribute to a nuanced understanding of the complexities of translating cultural connotations and maintaining semantic accuracy, offering a comprehensive typology that can guide future translation practices and serve as a springboard for further research in the field. Lastly, this study underscores the significance of maintaining cultural connotations in translation, thereby contributing to the ongoing development of cross-cultural communication.

1 Introduction

The rapid globalization and increased international travel have led to a surge in cross-border tourism (Gao et al., 2022). China is one of the world’s most sought-after destinations, attracting many foreign visitors. Smith (2016) contends that the primary motivation for inbound tourists is the allure of China’s rich history and culture. Wang and Marafa (2021) further assert that China’s appeal extends to its natural landscapes and the captivating cultural meanings embedded in its majestic scenery. Tourism is inherently a cultural experience for foreign visitors. Promotional tourism materials are indeed editorial products with a distinct editorial line and unique policy. The destination culture is accordingly represented and narrated. Translating tourism materials as a cross cultural communication poses great challenges related to non-equivalent issues in the target language (Chen et al., 2023a), making it particularly demanding for translators. Cultural references, inherently culture-specific, are known and unique to one cultural community but not to others. The translatability of these references has long been a focal point for translators and translation theorists. Some scholars even describe them as problematic and “indicating the limits of the translatable” (Petillo, 2012, p. 248). Within the translation literature, various labels exist for cultural references, such as “culture-specific, bound reference/element/terms/items/expressions, realia, or cultural references” (Marco, 2019, p. 2). These terms are challenging to define precisely, as they encompass “not only objects but also words” signifying “concepts related to a specific culture” (Terestyényi, 2011, p. 13). These terms could be specific or general, referring to a kind of food, a religious doctrine, or a societal practice (Baker, 2018). The current study uses “cultural references” to refer to expressions, concepts, words, and phrases unique to the original culture. In the target culture, these items are either without counterparts or have distinct semantic meanings and cultural connotations.

Katan (2009, p. 79) states translators need “to transfer the terms and concepts in the source text abroad with minimum loss”. Previous studies questioning the semantic accuracy of cultural references with cultural connotations indicate that, despite the critical role that cultural references play in tourist materials, the quality of tourism translation remains a topic of scholarly contention (e.g., Agorni, 2012; Hogg et al., 2014; Sulaiman and Wilson, 2018). Within a specific culture, cultural connotations can have additional meanings and associations. These are known as cultural connotations. When cultural references are misinterpreted, cultural connotation losses occur. For example, red represents luck, happiness, and joy in Chinese culture. It is frequently utilized to provide positive vibes to festivities and events like weddings and the Lunar New Year (Dimitrieska and Efremova, 2021). In Western culture, the red color can symbolize passion and love, but it is also linked to danger and warning signals, occasionally indicating hostility or rage (Harutyunyan, 2015). A reader may become confused and lose interest in the intended destination if crucial cultural connotations and semantic meanings are lost due to inadequate translation.

According to Qiu (2022), foreign visitors favor Beijing, Shanghai, and Sichuan. Two of China’s most well-known cities for foreign tourists are Beijing and Shanghai (Lyu et al., 2021), each capturing unique cultural, historical, and socioeconomic aspects. Conversely, Sichuan presents a distinct cultural environment distinguished by its abundant gastronomic legacy. Lonely Planet, one of the biggest publishers of travel guides and information worldwide (Wang et al., 2023), is a noteworthy illustration of China’s efforts to increase its market share in the global tourist industry. While travel guides, brochures, and guidebooks all fall under the umbrella of tourism materials, they serve different purposes and have distinct characteristics. A travel guide serves as a comprehensive source of information for travelers. It typically provides detailed insights into various aspects of a destination, including its attractions, accommodations, dining options, transportation, local customs, and practical travel tips, aiming to assist individuals in planning and navigating their trips effectively. For brochures and guidebooks, tend to be concise and may lack the depth needed for in-depth research. They focus more on promotional content rather than comprehensive information. While detailed, they may have a narrower focus or specific thematic emphasis, limiting their applicability to broader research objectives.

Numerous studies focused on the translation of Lonely Planet’s travel guides (e.g., Pan, 2015; Li, 2018; Song and Zhu, 2019; Tang, 2022). However, most of these studies have been conducted in Western countries. It deserves further investigation to discover if translating travel guides for non-Occidental nations results in the same issues, such as losing crucial semantic meanings and cultural connotations. Some Chinese scholars have studied Chinese-English translations to fill this gap (Guo, 2017; Meng, 2019; Zou, 2020; Tan, 2021). Among the other cities and provinces in the nation, they chose to speak to Hubei, Henan, Gansu, Dali, and Northeast China. However, the most popular tourist destinations for foreigners are usually already internationalized and show a strong cultural and historical legacy; Beijing, Shanghai, and Sichuan are a few examples. Furthermore, the analysis of cultural connotations in previous studies was limited to a single location; nevertheless, because of geographical disparities, the cultural connotations associated with different destinations are distinct and varied.

According to Li et al. (2022a,b), translation studies continue to give the tourism text genre a relatively peripheral role. Rhetorical devices (Zahrawi, 2018), religious information (Alwazna, 2014; Zahrawi, 2018), historical and cultural background (Tiwiyanti and Retnomurti, 2017), customs and festivals (Kuleli, 2019), and cuisine (Dann, 1996; Marco, 2019) are just a few of the studies that investigated the cultural connotation losses in literary works translations. In contrast, not much research has been done on the typologies of cultural connotation losses in materials related to tourism, such as travel guides. Numerous academics believe that the intricacy of translating cultural connotations results in a loss of semantic meaning. Therefore, the translations for travel guides are often deemed low quality (Valdés, 2013; Sulaiman, 2014; Zou, 2020; Li, 2021). But there is also a lack of research on the culturally based semantic losses.

In addition, earlier studies on tourism translation have evaluated the effectiveness of micro-level translation procedures for cultural references in conveying cultural connotations (Qassem et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2023b). Further research (Lin, 2021; Turzynski-Azimi, 2021; Li et al., 2022a,b; Chen et al., 2023a) examined the impact of the macro-level translation methods on the translation. However, the implications of the translation decisions (both macro and micro levels) on culturally based semantic losses were not examined. Addressing these gaps, the current study seeks to identify the types of cultural connotations losses in the Chinese cultural references’ English translation for Lonely Planet’s travel guides. In addition, this study attempts to investigate the culturally based semantic losses, with special reference to certain cultural connotations loss that result in partial or complete semantic loss. Besides that, this study aims to examine the implications of the translation decisions, as involved in translating cultural references, on culturally based semantic losses. Therefore, the research questions are as follows:

RQ1: What are the types of cultural connotations losses that occurred in the English translation of Chinese cultural references in Lonely Planet’s travel guides?

RQ2: What are the culturally based semantic losses in the English translation of Chinese cultural references in Lonely Planet's travel guides?

RQ3: How do the translation decisions (both macro and micro levels) impact the cultural-related semantic losses in the English translation of Chinese cultural references in Lonely Planet's travel guides?

2 Theoretical framework

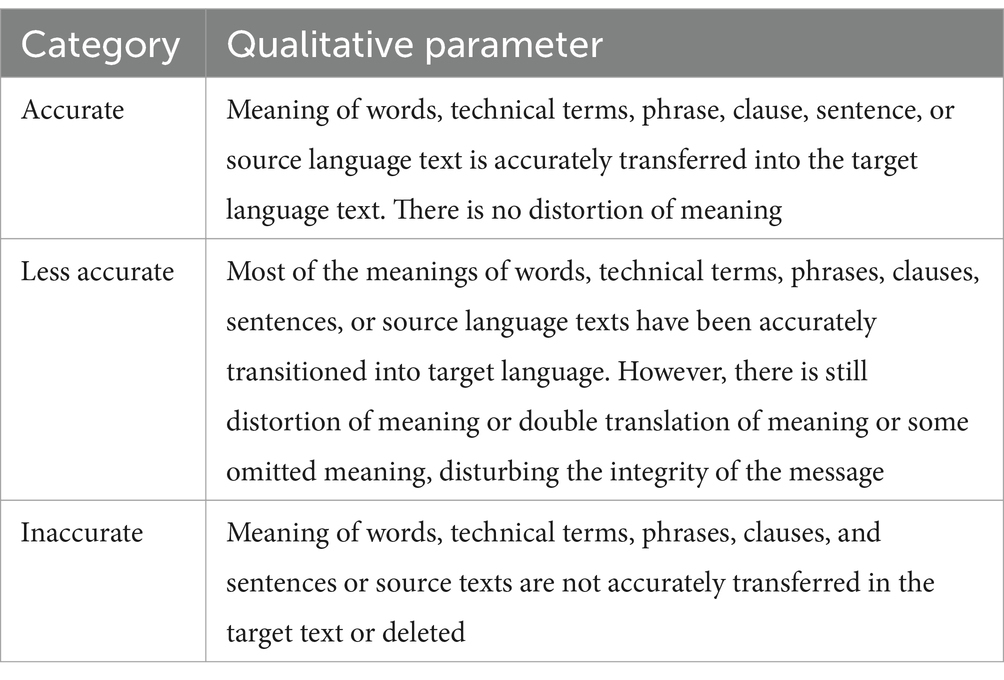

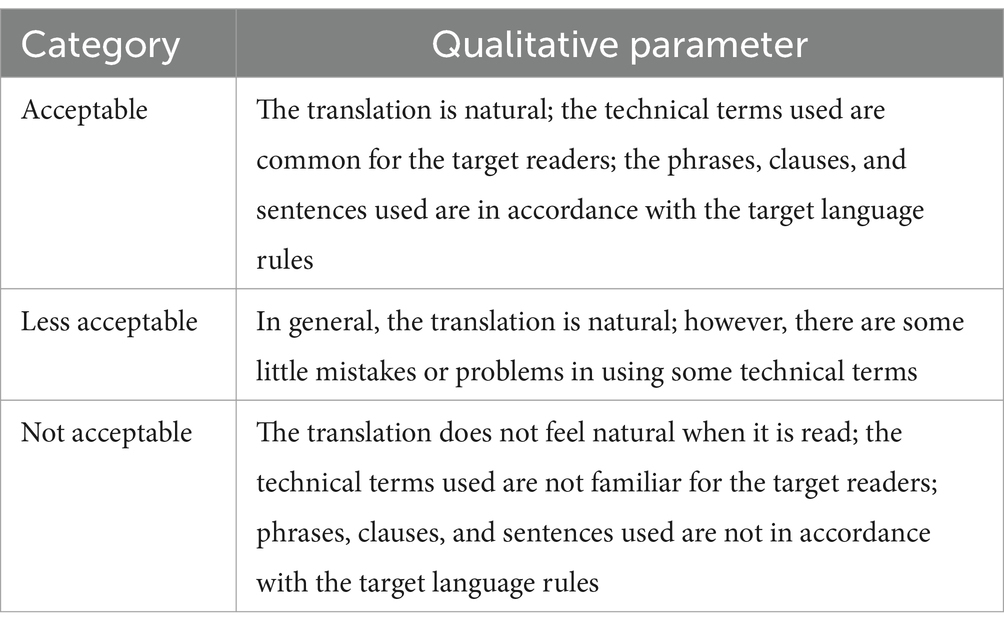

Two theories formed the basis of the current study. The primary theoretical foundation for this study’s investigation of the types of cultural connotations losses and the culturally based semantic losses was provided by Nababan et al. (2012) translation quality assessment. Three main criteria are used to evaluate the quality of a translation: accuracy, acceptance, and readability. The degree of fidelity or correspondence between the content of the source and target languages is termed accuracy, according to Nababan et al. (2012). Table 1 displays the qualitative accuracy parameters. Nababan et al. (2012) define acceptability as the extent to which a translated text complies with the norms, traditions, and practices of the target language and culture. It is another important dimension. Table 2 displays the acceptability’s qualitative parameters. Another critical component of translation quality is readability, which is the degree to which the target audience can promptly and readily understand the translated material (Nababan et al., 2012). It is crucial to make clear that the metrics of accuracy and acceptability are the only ones on which this study bases its analysis. Although readability is unquestionably a crucial component in Nababan et al. (2012) theory, it has been purposefully left out for the following reasons. First and foremost, a thorough textual examination of the translated travel guides is the main emphasis of this study. Instead of evaluating the translations’ readability for a particular audience, the main goal is to explore the cultural nuances incorporated into them. Additionally, the study does not use surveys or interviews with international tourists. Since readability assessment requires input directly from the intended audience, it is impossible to do a thorough analysis of this dimension in the absence of such information.

The current study also applied Venuti’s (1995) domestication and foreignization to analyze the implications of the macro-level translation methods of the identified micro-level translation procedures on the culturally based semantic losses. According to Venuti (2004, p. 203), domesticating translations “conform to values currently dominating the target-language culture, taking a conservative and openly assimilationist approach to the foreign text, appropriating it to support domestic canons, publishing trends and political alignments.” On the other hand, foreignizing translation may “resist and aim to revise the dominant by drawing on the marginal, restoring foreign texts excluded by domestic canons.” The current study analyzed cultural references embedded with cultural connotations and semantic losses in translation in the context of travel guides and examined the implications of translation methods of employed translation procedures on these losses.

3 Literature review

3.1 Studies on cultural references

Finding the appropriate equivalents for cultural references with cultural connotations is “the hardest thing” in translation, according to Petrulionė (2012, p. 44). Similarly, Kuleli (2019) emphasized that preserving the cultural connotations associated with cultural references is important. Horbačauskienė et al. (2016) offered a fresh viewpoint on evaluating the translation of cultural references in subtitling, pointing out that the precision of cultural references plays a crucial role in assessing the semantic quality of the translation, given the expansion of research on this subject beyond literary translation. They discovered that source-oriented transference through retention—which leads to poor translation quality and semantic losses—is a simpler way to deal with cultural references. Besides that, Farkhan et al. (2020) concentrated on how Netflix cooking shows understand cultural references relating to food and what influences the selection of translation procedures. The significance of food-related cultural references for cultural distinctiveness has been widely discussed in the literature since Newmark (1988, p. 97) assertion that food is one of the most “sensitive and important” markers of a nation’s cultural identity.

More recently, Amenador and Wang (2022) investigated cultural references translation in the Chinese to English food menu corpus. They identified the prevalent procedures and investigated the factors that influenced the selection of specific procedures. The primary factors discovered were the degree of cultural markedness, the misleading link between the source text’ item and the target text’ item, and the metonymic/metaphorical use of the cultural references. More significantly, Amenador and Wang (2022, 2023) emphasized that cultural connotations within culinary contexts can be lost if an emphasis is only placed on the linguistic features of cuisine at the expense of its underlying cultural image. They also found that neutralizing procedures were used more frequently than foreignizing or domesticating methods. This result was in line with other findings from earlier research (e.g., De Marco, 2015; Oster and Molés-Cases, 2016; Setyaningsih, 2020). Furthermore, the results conflicted with earlier research. For instance, Demir and Genç (2019) focused on the food-related cultural references translation from English to Turkish and found that a target-oriented method (domestication) was adopted. However, it may be difficult to compare the translation of food-related items in literary works with food menus, as the standards governing these two activities may be quite distinct.

Turzynski-Azimi (2021, p. 10) presented a novel viewpoint regarding the cultural connotations losses and revealed how the degree of loss differs “depending on the category” of cultural references. Furthermore, it was found by Turzynski-Azimi (2021) that the prominence of historical eras, architectural features, and proper names in tourism literature promoting historical attractions was mirrored in proportionate tendency. However, the translation of these parts was considerably restricted because a potential tourist lacking knowledge of the historical background of the source language could not associate these cultural references with their corresponding connotations in the target culture. To historically situate the text’s content, the recipient had to look elsewhere for contextual clues. Furthermore, the study emphasized the criticality of reducing the cultural connotations losses in the culinary items. This discovery provided further evidence in favor of De Marco’s (2015, p. 310) assertion that visitors “recognize food as a powerful expression of the… cultural identity of a place.” According to recent research by Marco (2019), every aspect of culture is somehow interconnected with food.

3.2 Studies trends on cultural references

Many taxonomies of translation techniques pertaining to cultural references have emerged in the studied literature (Nedergaard-Larsen, 1993; Pedersen, 2007; Olk, 2012; Marco, 2019). These taxonomies aim to establish translation procedures along a “continuum between ST and TT orientation” (Ramière, 2016, p. 3). The way translators handle micro-level procedures when confronted with the unique linguistic components of tourism materials influences the way the source language destination is portrayed at the macro level as a tourist attraction.

Another research trend focused on translation quality assessment. For example, Amiri and Tabrizi (2018) examined the cultural references using Newmark’s (1988) categories and translation procedures and House’s (1997) translation quality assessment. The study found that the loss of meaning was a key factor influencing the translation quality. Similarly, Kamalizad and Khaksar (2018) also used House’s (1997) model. Furthermore, Karimnia and Heydari Gheshlagh (2020) found certain cultural references rendered by separating the semantic components into pieces. Sofyan and Tarigan (2019) proved the translation quality assessment (TAQ) proposed by Nababan et al. (2012) was based on a holistic nature. This model endeavored to mitigate subjectivity and relativity in TQA by distinctively addressing the quality dimensions: accuracy, acceptability, and readability. In a more recent study, Marhamah et al. (2021) investigated the translation quality of subtitling using the model proposed by Nababan et al. (2012). In the same year, Pratama et al. (2021) also used Nababan et al.’s (2012) model as a foundation and discovered that translating tourism promotional texts’ cultural references was challenging. Similarly, Putri et al. (2022) investigated the translation of the Medan City Tourism website pages under the TAQ Nababan et al. (2012) developed. Overall, the examined earlier research demonstrated the impact of semantic meanings on the quality of translation. As previously posited, the accuracy of translated semantic meanings was significantly complicated by the cultural connotations encoded within cultural references.

3.3 Studies on cultural connotations in tourism materials and semantic accuracy

When considering translation studies in a broader context, the tourism textual genre is frequently placed at the periphery (Chen et al., 2023b). Limited scholarly focus has been devoted to examining translation studies concerning tourism materials written in languages that share different cultures, such as Chinese and English. Agorni (2012) stated that the cultural connotations in rhetorical devices, such as similes and metaphors, were frequently used in persuasive text types, including tourism materials, to engage readers by captivating their attention. Furthermore, Agorni (2012) discovered that the translators intentionally preserve and accentuate the stylistic impact of metaphorical cultural connotations. Moreover, according to AmirDabbaghian (2014), translations of tourism materials lost cultural connotations as dish names containing personal names, references, and legends. In a similar vein, Chiaro and Rossato (2015) emphasized the unexpectedly limited attention paid to the connection between translation, culture, and cuisine. Larson (1998) argued that although translators must strive to convey both form and meaning when dealing with cultural references, their primary goal is to preserve the intended meaning and stressed that “the receptor language form should be changed so that the source language meaning not be distorted” (p. 12). According to Nida (1964), when “conflict” arises between form and content, “correspondence in meaning must have priority over correspondence in style” [cited in Munday (2001), p. 42]. Therefore, while translating cultural references, the interpreter should prioritize communicating the intended meaning over the literal translation. Every society possesses cultural references unique to its language that have not been lexicalized in another language, according to Maasoum and Davtalab (2011). They also recommended that the translators choose the most appropriate procedure following the situation, purpose, and context. In translating cultural references, Kim and Kim (2015) introduced transliteration supplemented by semantic translation enclosed in parentheses. Furthermore, cultural references that are rendered by deconstructing the semantic components of a compound term were recognized by Karimnia and Heydari Gheshlagh (2020). However, Hashim (2023) contended that translation becomes troublesome when semantic meanings are critical and believed a complete comprehension of cultural context is insufficient.

The relevance of Venuti’s (1995) observation that translation has a significant capability to produce images of foreign cultures in texts endorsing tourist destinations is underscored by the “cultural load implied in the language of tourism” (Gandin, 2013, p. 327). Cultural references must be negotiated as critical indications of cultural identities when selecting translation procedures to properly educate and attract a potential visitor. The internal contradiction between the author’s cultural orientations and those of the intended audience is a fundamental characteristic of translated tourism texts. Translators assume the role of intermediaries to respect the target reader’s cultural context while strategically emphasizing the foreign. This concept has been described in Venuti (1995) framework of foreignization and domestication. Foreignized translations preserve or accentuate differences, urging the reader to depart from a familiar background and confront the unknown. Conversely, domesticated translations diminish or obscure peculiar aspects, concealing the foreign in a familiar garment for the receiving society (Venuti, 1995). The dichotomy between these two extremes is particularly apparent in tourism literature, where the primary aim is to educate readers about the unfamiliar. A potential drawback of a foreignized translation is that it may hinder communication. This can occur when the reader is deterred from exploring alternative subjects or when the text’s persuasive power is diminished. Additionally, an excessive domestication of the foreign elements in the text may jeopardize its authenticity and originality (Dann, 1996). The tourism industry’s dual objective of safeguarding clients against unforeseen circumstances and delivering a memorable experience may prove challenging to measure, according to Cronin (2000).

Numerous prior investigations have examined the prevailing translation procedures, representing the bulk of translation efforts concerning tourism literature. Sanning (2010) discovered, for instance, that the translations were replete with Pinyin and transliteration, neither of which was sufficient for the average English reader to comprehend the cultural connotations embedded in cultural references; this led to the loss of cultural connotations in historical context. In addition, Mansor (2012) investigated the religious-related cultural references and cultural connotations in gastronomy. Foreignization prevailed in the translations of historically important cultural references in Japanese travel texts, according to a more recent study by Turzynski-Azimi (2021). The frequency of non-lexicalized borrowing in translating proper names, architectural structures, and historical eras was also revealed in this study. This finding suggested that translated materials employing foreignized methods that favor the source culture were accepted. However, Agorni (2012, p. 6) adheres to Kelly’s (1997, p. 39) advice on “information loss,” contending that such a foreignizing method could hinder communication by denying the reader access to the cultural connotations associated with unfamiliar cultural expressions. Similarly, Turzynski-Azimi (2021) demonstrated that an audience outside of Japan could not perceive the cultural connotations of historical characters that were well-known to Japanese readers with sensitivity. When this occurs, the lack of additional procedures, such as an explanation, could suggest that the translator could not distinguish between the target culture and the reader’s presumptive comprehension of the source culture. As stated by Poncini (2006), the absence of compensatory procedures, such as explanation, harms the development of “shared knowledge of local … attractions and the readers appreciation of these features and their value” (p. 141). Numerous cultural connotations embedded in the translation of cultural references have been analyzed in the context of tourism materials. Nevertheless, there has been a lack of investigation into the typologies of cultural connotation losses and culturally based semantic losses.

4 Methodology

4.1 Research approach

The present study employed a qualitative descriptive research design to investigate, gather, and assess data to answer the research questions in the Chinese-to-English translation of Lonely Planet’s travel guides.

4.2 Data sources

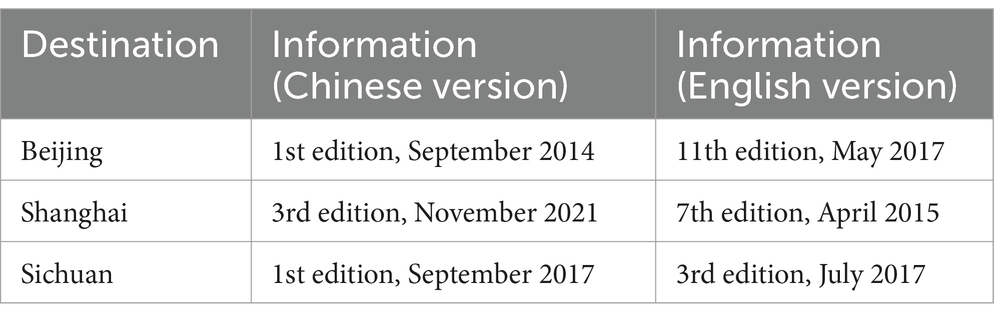

As indicated in Table 3, the researcher’s selection of specific editions for the travel guides (Beijing, Shanghai, and Sichuan) aligns with the research objectives focused on addressing culturally based semantic losses in the translation of cultural references, particularly in the introductory sections of attractions. The researcher prioritizes the more recent Chinese editions for Beijing, Shanghai, and Sichuan. The Chinese versions have more frequent updates, encompassing changes in prices for accommodation, food, admission fees, opening and closing times, etc. This ensures that the data used in the research is up-to-date and reflective of the current conditions and trends in the destinations. While changes in prices are crucial, the researcher notes that the content of the introductory sections for attractions remains the same across editions. This observation justifies the focus on the more frequently updated Chinese editions, as changes in prices for these sections are not central to the research objectives.

The study is based on maximum variation sampling, which entails choosing samples that possess features that transcend contexts and get their significance from being generated from heterogeneity (Palinkas et al., 2015). In this study, the researcher identified cases that exemplify the spectrum associated with the issue being investigated (Hancock et al., 2009). An extensive collection of data for the study was obtained by identifying 500 cultural references under Newmark’s (1988) taxonomy. Saturation served as the criterion for selecting the quantity of the sample in terms of size, which signifies that enough data has been collected for the planned investigation, and further material would not yield new information (Elliott and Timulak, 2015). Hence, sample adequacy, a critical condition for bolstering the study’s validity, was established in the present investigation through the selection of samples till saturation was achieved.

4.3 Instrument and data collection

Instruments and data collection methods in qualitative research are constrained “to a large extent by the research questions and objectives” (Canals, 2017, p. 390). This study aims to examine culturally based semantic losses in translating cultural references in Lonely Planet’s travel guides, as stated previously. These travel guides exemplify popular culture documents, as “culture” arises when “society produces materials designed to entertain, inform, and perhaps persuade the public” (Merriam and Tisdell, 2015, p. 143). The present study employed a document-review approach, with the assistance of Microsoft Excel, as its data-gathering tool. To ensure data validity, the current study adopts the three-step process described by Merriam and Tisdell (2015).

The initial “document-location” phase involved the researcher manually gathering 500 cultural references with their Anglophone counterparts from printed versions of the three selected destinations. The second phase involved verifying the authenticity of the gathered documents. Two aspects comprised this phase. Firstly, “the author, the place, and the date of writing all need to be established and verified” (Merriam and Tisdell, 2015, p. 151). The data collection involved manually recording page, column, and line numbers, subsequently transcribed into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. Subsequently, the researcher determined the “primary or secondary” nature of the documents (Merriam and Tisdell, 2015, p. 152). Primary documents consist of documents in which the author conveys first-hand knowledge or expertise about the subject matter. The Lonely Planet travel guides examined in this context contain precise self-descriptions; hence, they qualify as primary documents, highlighting their role as firsthand sources of information about the destinations they cover.

In the third phase of the document review process, a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet was utilized to manually code the documents. There were three stages of data coding conducted in the present investigation. In relation to the first research question, the focus of this study was the analysis of cultural references that have experienced a loss in their cultural connotations. The researcher adhered rigorously to the acceptability criterion (Nababan et al., 2012). During the initial stage of data coding, any cultural references deemed less acceptable or unacceptable were entered into the “travel guides data” column of a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet titled “cultural connotations losses.” In relation to the second research question, the present study examined the culturally based semantic losses. The accuracy parameter guided the execution of the second round of data coding (Nababan et al., 2012). All cultural references, either deemed less accurate or inaccurate, were entered manually into the “travel guides data” column of a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet labeled “culturally based semantic losses.” In relation to research question three, the current study delved into the implications of the translation decisions (both macro and micro levels) on culturally based semantic losses. In the third phase of data coding, the translation procedures used to investigate the impact of translation methods on culturally based semantic losses per Venuti’s (1995) concepts of domestication and foreignization were coded. All data were manually coded into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet, “travel guides data,” in the column named “micro-level translation procedures.”

4.4 Data analysis

Ongoing “back and forth” movement is necessary for data analysis (Merriam and Tisdell, 2015, p. 167) since the researcher must flow between deductive and inductive thinking, describe concrete facts, comprehend abstract notions, and so forth. This research exemplifies a qualitative inquiry that utilizes inductive data analysis, wherein the researcher derives themes and patterns from the initial data. The data analysis for the present investigation commenced concurrently with the data collection. This study also incorporated content analysis to attain a more comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon under investigation (Krippendorff, 2018).

The current study was initiated by collecting and analyzing the data about Sichuan. This selection assumes that Sichuan has a relatively smaller number of available quantum editions (in Chinese and translated English) than Beijing and Shanghai. The researcher employed Newmark’s (1988) model to identify cultural references as she read the hard copy and Nababan et al.’s (2012) acceptability parameter to assess the loss of cultural connotations. The researcher annotated and commented in the margins, contrasting these with cultural references potentially pertinent to addressing Research Question One or otherwise significant to the current investigation. After completing the transcript in this manner, she reviewed the marginal notes and comments to group them where applicable. The researcher manually entered these into the Microsoft Excel spreadsheet “travel guides data” in the column named “Sichuan.” Moreover, the researcher began constructing categories by assigning codes to pieces of data.

Succeeding that, the remaining documents (Beijing and Shanghai) underwent the same operation. The researcher scanned them as mentioned above, comparing the extracted list of categories from the initial Sichuan document with those found in the remaining two documents and maintaining this list in mind. The researcher compiled notes and comments for each document before comparing these with the material from the preceding document (Sichuan). In due course, the data were manually entered into the Microsoft Excel spreadsheet “travel guides data” in the columns named “Beijing” and “Shanghai,” respectively, as appropriate. A comprehensive triple verification process was conducted on the “Sichuan” column and both the “Beijing” and “Shanghai” columns to detect the various types of cultural connotation losses.

The columns labeled “Beijing,” “Shanghai,” and “Sichuan” within the dataset of travel guides formed a rudimentary framework or fundamental classification system, which demonstrated the cultural connotations associated with Chinese cultural references were lost, as translated into English. Data retained their original identification codes, denoting their provenance from “Beijing,” “Shanghai,” or “Sichuan,” as well as specific page, column, and line references for the cited excerpts (referred to as cultural references). Including these comprehensive details ensures the researcher can readily access and review the data as needed.

Regarding Research Question Two, the accuracy parameter of Nababan et al. (2012) was deployed to evaluate the degree of semantic loss generated by the translation in question and to interrogate the relationship between semantic and cultural connotations loss. The current study deemed less accurate translation resulted in partial semantic loss, whereas inaccurate translation resulted in complete semantic loss. As previously stated, specific file folders were created, each assigned to represent a certain type of cultural connotation loss. The researcher meticulously recorded the assessment results for each cultural reference containing cultural connotation losses in the “semantic loss” column of each file folder. This documentation unveiled that specific type of cultural connotation loss resulted in either partial or complete semantic loss. After thoroughly evaluating the accuracy of all cultural references embedded with diverse cultural connotations losses, the present study calculated the percentages of partial and total semantic losses, respectively. This allowed for an investigation into the significant influence that cultural connotations losses have on successive semantic losses. Venuti’s (1995) “foreignizing” and “domesticating” macro-level translation methods were applied to aid in the data analysis for Research Question Three. The researcher meticulously examined the micro-level translation procedures for each cultural reference that involved cultural connotations losses and semantic losses. The translation procedures were recorded in each file folder’s “translation procedures” column.

5 Findings

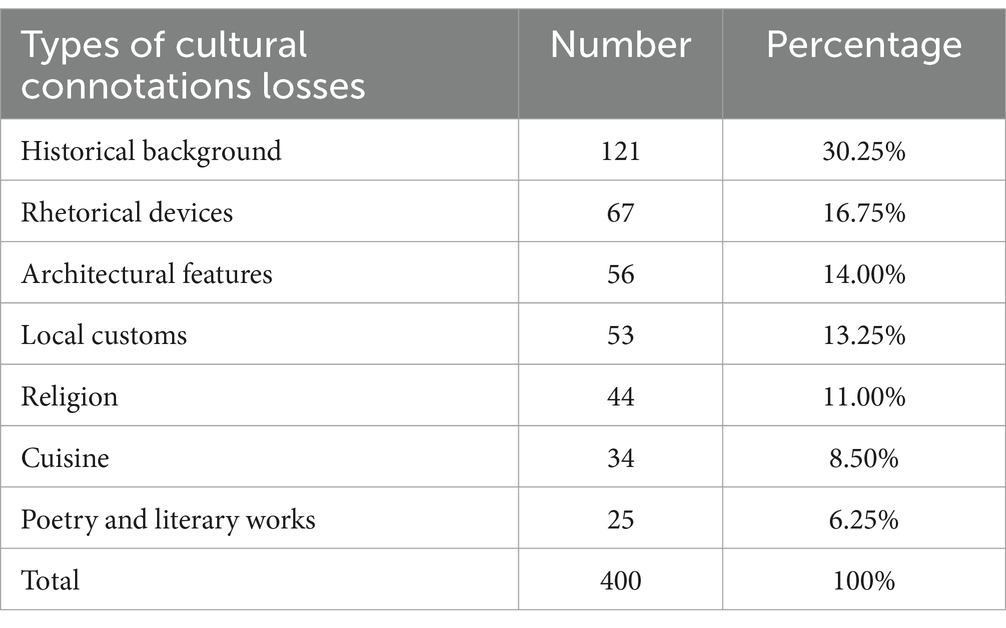

Seven types of cultural connotation losses in the translation of cultural references in Lonely Planet’s travel guides for Beijing, Shanghai, and Sichuan were identified in the present study (see Table 4). The most prominent type was detected in the historical background (121 occurrences); it consisted of prefaces to notable historical figures, chronological context, and political developments. For example, 永陵已有上千的历史 (lit: Yongling has thousands of years of history) → the thousand-years-old Yongling. The term “Yongling” carried cultural and reverential connotations associated with the imperial tomb. The translation might miss conveying the respect and cultural significance attached to such specific historical figure’s resting places. 永陵 is not merely a generic term for a tomb but holds specific historical and cultural significance as the final resting place of Wang Jian (847–918). Understanding the cultural context, historical role, and legacy of Wang Jian is essential to grasp the cultural connotations associated with 永陵. 珍品馆…雕刻于太平天国时期的紫檀木座椅特别精彩 (lit: Treasures Hall…The rosewood seats carved during the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom are particularly exciting) → Treasure Gallery… including a set of armchairs made of red sandalwood from the age of Taiping Heavenly Kingdom. 太平天国时期 refers to a Chinese Christian theocratic absolute monarchy that sought to overthrow the Qing dynasty from 1851 to 1864 and was led by King Hong Xiuquan and his followers. The translation failed to illustrate the cultural connotations of 太平天国时期. The failure to accurately transmit the full cultural connotations connected with the historical context in Chinese culture can be attributed to the disparate historical and cultural origins of the English and Chinese languages. It is worth noting that historical background information is intricately woven into the cultural context of the source language. The precise cultural connotations and importance associated with historical figures, events, and political developments present challenges in conveying this information accurately to the target language, ultimately resulting in the omission of cultural connotations. Based on the taxonomy of cultural references proposed by Nedergaard-Larsen (1993), the findings of the losses of cultural connotations in historical context are consistent with those of other prior research concerning historical notables, political development, and chronology context. For instance, Turzynski-Azimi (2021) conducted an analysis incorporating Nedergaard-Larsen’s (1993) taxonomy and identified cultural references covering political conflicts and revolutions, historical figures, and chronological epochs, presenting translation obstacles.

The translation of rhetorical devices demonstrated the second highest frequency (67 occurrences) of cultural connotation loss. Rhetorical devices are frequently employed in Chinese language and literature, yet translations fall short of faithfully conveying their intended meanings and the cultural connotations integral to them. The translation of personification, metaphor, metonymy, and allusion was especially replete with this phenomenon. Translating these devices is a significant obstacle, leading to the omission of cultural complexities and subtleties fundamental to the initial rhetoric. For example, 五色海…返演历史,预测未来 (lit: The five-color sea… replays history and predicts the future) → Five Color Sea… is a celebrated holy lake in the Tibetan region. 返演历史,预测未来implies that this place holds mystical or profound quality beyond its physical beauty, being able to “reenact history and predict the future.” The original phrase personifies mystical qualities to this place, which were lost in the translated version. There’s a rich cultural and philosophical depth in the Chinese phrase that might not be apparent in the English translation. The notion of 返演历史,预测未来 holds spiritual or mystical implications that extend beyond a simple description of a holy lake. 天师张道陵看上青城山的深幽宁静,在此结庐传道,直至123岁“羽化成仙,” 青城山从此多了个道教发源地的头衔 (lit: The Heavenly Master Zhang Daoling fell in love with the deep tranquility of Qingcheng Mountain, so he built a house here and preached Taoism until he “transformed into an immortal” at the age of 123. From then on, Qingcheng Mountain gained the title of the birthplace of Taoism) → Covered in lush forests, the sacred mountain of Mount Qingcheng has been a Taoist spiritual center for more than 2000 years. The translation did not reference Zhang DaoLing, the Celestial Master, and his role in establishing Daoism at Mount Qingcheng. This translation overlooked the specific allusion to the founder and the subsequent attribution of Mount Qingcheng as the birthplace of Daoism due to Zhang DaoLing’s presence. In addition, the idea of Zhang DaoLing’s ascension to immortality (羽化成仙) is omitted in the translation, which is a significant aspect of the story.

Architectural features also experienced cultural connotation losses, which were recorded 56 occurrences in all three travel guides’ translations. Architectural styles and features frequently incorporate cultural connotations for which the target language has no exact translations. For example, 明楼后面的圆形宝城,它和前面的殿群所构成的方院,象征着天圆地方的建筑思想 (lit: The round treasure city behind the Ming Tower and the square courtyard formed by it and the palaces in front symbolize the architectural idea of a round sky and a square place) → …behind which rises the burial mound surrounded by a fortified wall. The original text embodies the idea of cosmic symbolism in Chinese architecture, which represents a deeply rooted cultural belief. The interplay between round and square shapes in the architecture symbolizes the harmony and balance between heaven and earth, a concept fundamental to Chinese philosophy and traditional architecture. The translation failed to effectively convey the cultural connotations of architectural features and the profound philosophical ideas embedded in the original text. Due to the context-dependent and highly specialized character of architectural terminology, it becomes difficult to discover appropriate equivalents for certain elements and transmit their cultural significance in the target language. A profound comprehension of cultural connotations is necessary when translating architectural characteristics; failure to do so may result in unintentional omissions or omissions throughout the translation process. Furthermore, the current investigation detected occurrences of cultural connotation loss in indigenous customs, amounting to 53 occurrences. This type of loss was observed when translations failed to convey the full cultural importance connected with Chinese customs or traditions. The traditional meals, customs, or beliefs associated with a particular local festival may be insufficiently conveyed in a translated version, resulting in the loss of cultural connotations. For instance, 阆中号称春节文化的发源地,年庆活动会持续近两个月,丛腊八到二月二 (lit: Langzhong is known as the birthplace of Spring Festival culture. The annual celebrations will last for nearly 2 months, from Laba to February 2) → Langzhong is the birthplace of the Spring Festival and celebrations last for a couple of months. 丛腊八到二月二 suggests that the New Year celebrations start with the “Laba Festival” (the eighth day of the twelfth lunar month) and continue until “Yuanxiao Festival” (the fifteenth day of the first lunar month). While the translation provides a general idea of the extended celebrations and some specific rituals, it might lose some of the detailed cultural connotations, such as unique customs.

In addition, occurrences of cultural connotation losses in other domains, such as religion, were identified (44 times). For example, …伏虎寺…别错过铸有4700余尊小佛与《华严经》全文的紫铜华严塔 (lit: Fuhu Temple… do not miss the copper Huayan Pagoda with more than 4,700 small Buddhas and the full text of the Huayan Sutra) → Crouching Tiger Monastery… houses a 7 m-high copper pagoda inscribed with Buddhist images and texts. 华严塔 carries religious and cultural significance. The presence of Buddhist images and the complete text of the Huayan Sutra (《华严经》) within the pagoda signifies the importance of Buddhist scriptures and spiritual teachings associated with the monastery. The translation missed the depth of cultural and religious connotations that the original text possessed. The source language frequently imparts profound cultural and historical significance to religious beliefs, ceremonies, and terminology. Without thoroughly comprehending the religious meaning of certain cultural references, translation may result in the loss of cultural connotations. The present study also noted the cultural connotations losses in cuisine (34 occurrences). Many Chinese cuisines and cooking techniques have strong regional or historical associations that are culturally significant in the original language, distinguishing them from their Western counterparts and contributing to this loss. Cultural connotations may be lost when translating these associations into the target language, which could require further explanations or modifications. For example, 凉拌山珍(干笋) (lit: Cold mountain delicacies (dried bamboo shoots)) → Mountain Treasure Salad (凉拌山珍; usually containing dried bamboo shoots). The translation mentioning dried bamboo shoots focused on one specific ingredient, which might not fully encompass the diversity and range of ingredients typically found in 凉拌山珍. While dried bamboo shoots can be part of this dish, they are not the sole defining component. Moreover, the term 凉拌 should have been rendered as “Cold-Tossed,” which refers to the method of preparing the dish—mixing the various ingredients with a cold dressing or sauce. This technique is crucial in retaining the freshness and natural flavors of the mountain-grown ingredients. It is not just about the specific inclusion of dried bamboo shoots but rather about a broader concept of gathering and presenting natural treasures from mountainous regions in a fresh, cold dish. Furthermore, literary and poetic works were translated into English with lost cultural connotations (25 occurrences). On occasion, the translation fell short of accurately communicating certain symbolic elements of poetry and literary terms, which were inherently complex and culturally significant. These subtleties frequently elicit cultural esthetics and feelings. Translating them while preserving their cultural depth and complexity can be challenging and may result in the loss of certain cultural connotations. For example, 清音阁始建于唐僖宗年间,名称源自左思《招隐诗》“何必丝与竹,山水有清音” (lit: Qingyin Pavilion was built during the reign of Emperor Xizong of the Tang Dynasty. Its name comes from Zuo Si′s “Poem of Zhao Yin” “Why bother with silk and bamboo? The mountains and rivers have clear sounds”) → 清音阁. Named ‘Pure Sound Pavilion’ after the soothing sounds of the waters coursing around rock formations. The translation captured the literal meaning of the term 清音阁 and its etymology from the phrase in the poem by Zuo Si. However, it does not fully encapsulate the cultural connotations, literary references, and poetic essence embedded in the original Chinese text. Culture has an important influence on the communicative function of tourism texts, as demonstrated by prior studies (e.g., Pan, 2015; Li, 2021). As a result, translators must be able to comprehend cultural connotations embedded within cultural references to convey the genre’s “communicative position” (Kelly, 1997, p. 34). This study revealed that when translating travel guides from Chinese cultural references, Anglophone native language translators tended to lose the cultural connotations embedded within them.

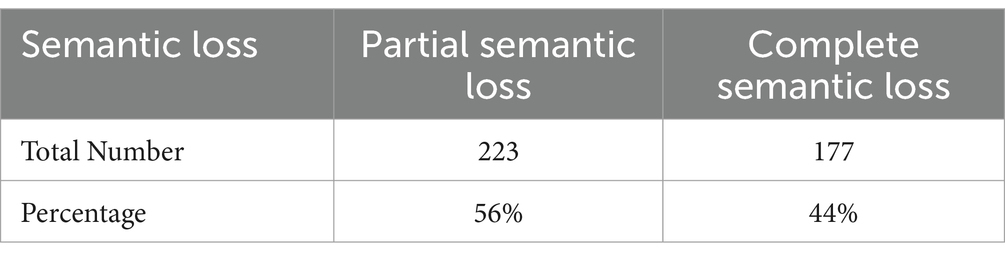

Moreover, the results indicated that the degree of semantic losses influenced by the types of cultural connotation loss varied from complete to partial. Complete semantic losses happen when the original language’s meaning is not entirely transferred or twisted. Conversely, partial semantic losses entailed transmitting a fractional portion of the intended message originating from the source language. All occurrences of complete and partial semantic loss in translation (attributable to the cultural connotations losses) were outlined in Table 5. The findings indicated that complete semantic loss accounted for 44%, whereas partial semantic loss comprised 56%. The results confirmed that partial semantic losses were the most prevalent type of semantic loss observed in the translations of travel guides. For example, 说到乐山的翘脚牛肉… (lit: Speaking of Leshan’s beef and sweet-skinned duck…) → The soupy beef with herbs (翘脚牛肉; Qiàojiǎo niúròu) …are all gastronomic delights of Lesan. A partial semantic loss occurred due to the cultural connotations loss related to cuisine in this case. The translation provided “soupy beef with herbs,” conveying the basic idea of the dish, but failing to capture its cultural connotations and the specific associations linked to Sichuan cuisine. The partial semantic loss occurred because the translation did not effectively convey the cultural connotations associated with 翘脚牛肉 (Qiàojiǎo niúròu) and its significance in Sichuan cuisine. “翘脚” (Qiàojiǎo) carries the connotation of being delicious or satisfying in the Sichuan dialect. Including this term would indicate the locals’ appreciation for the dish and their satisfaction with its flavors. However, by omitting this cultural connotation, the translation lost the richness and specific cultural associations related to the dish. As cultural nuances influence semantic meaning and comprehension, it is worthwhile to investigate the correlation between cultural connotations losses and semantic losses in translation contexts. The cultural connotations are deeply ingrained within the social, historical, and cultural settings of the language, and they possess multidimensional meanings that transcend the precise definitions of the cultural references. Within the realm of travel guides, which communicate cultural insights and recount personal experiences at destinations (Federici, 2007), it is crucial to know not only the literal meaning of cultural references but also the cultural connotations that accompany them (Islam, 2018). Culturally based semantic loss occurs when the translated cultural reference loses its intended meaning or fails to convey the cultural subtleties and connections present in the original language.

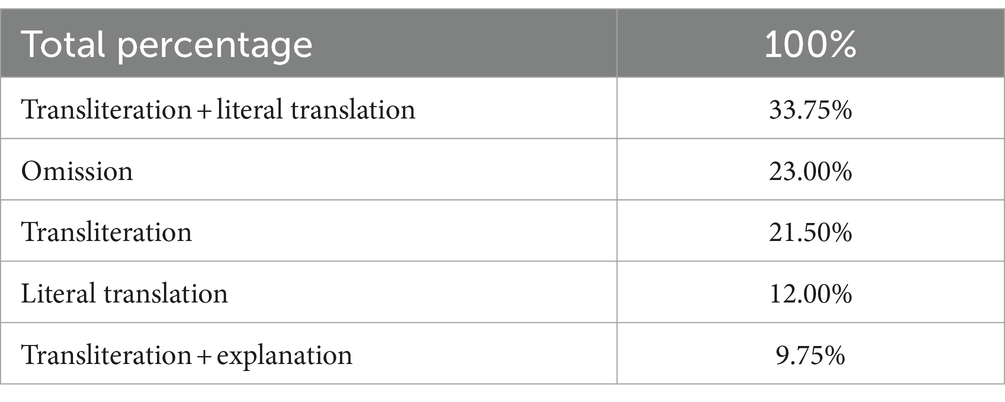

Additionally, the findings of this study revealed the prevalence of macro-level translation method foreignization. The micro-level translation procedures including literal translation, transliteration, transliteration + literal translation, transliteration + explanation, and omission were utilized. Table 6 presents their proportions. Transliteration, literal translation, and their combination counting 67.25% are employed dominantly, which represents a conscious effort to prevent the influence of Western cultural mores and prioritizes the maintenance of the cultural and linguistic distinctiveness of the source culture. This finding is consistent with a prior investigation conducted by Chen et al. (2023a), which identified foreignization as the prevailing approach in translating tourism texts. In the same vein, Chung (2021) argues that foreignization works in the following ways: it enhances visitors’ cultural engagement, prevents ethnocentric biases, aligns with the preferences of the target audience, grants a unique cultural identity, and promotes intercultural exchanges. The following detailed the impacts of translation decisions (both macro and micro levels) on culturally based semantic losses.

A hybrid approach is implemented when transliteration and literal translation are mixed, comprising 33.75 percent of the micro-level procedures. This approach, characterized by using transliteration to preserve the initial phonetic representation, tends to preserve linguistic faithfulness to the culture of origin (Aixelá, 1996). For example, 你会难忘在江边的“夜啤酒”摊儿(在川西成都平原一带,这种晚饭兼夜宵摊叫“冷淡杯”),吹着风、光着膀子吃几碟各式各样的卤味,甚至是爆炒的江湖菜 (lit: You will never forget to sit at the “Night Beer” stall by the river (in the Chengdu Plain area of western Sichuan, this kind of dinner and late-night snack stall is called “Lengdan Cup”), eating several plates of various braised food with bare arms in the wind. Even stir-fried Jianghu dishes) → An evening sampling the street food and drinking beer by the riverside is a must. In Chengdu Plain to the west of Sichuan, this kind of dinner or late-night snack is commonly called “Cold Cup.” Choose from a variety of marinated street snacks: try the deep-fried Jianghu cuisine in the cool evening breeze. In this case, the translation of “江湖菜” as “jianghu cuisine” posed semantic losses as it not effectively conveying the cultural connotations. The cultural context of “江湖” (jianghu) was inadequately conveyed, which traditionally refers to a realm beyond mainstream society. “江湖菜” is deeply rooted in folk culture and reflects the culinary practices of people living on the fringes of society. English readers unfamiliar with the term “jianghu” might interpret “jianghu cuisine” merely as a type of culinary style without understanding the cultural and societal connotations associated with the original term. It is worth noting that the literal translation of this hybrid approach, although praiseworthy for its strict adherence to word-for-word reproduction, does not adequately encompass the complete range of cultural nuances (Vinay and Darbelnet, 2000). Consequently, the effectiveness of this approach in communicating the entirety of cultural connotations and semantic meanings to the target culture can be compromised, perhaps leading to a degree of cultural detachment among the target audience from the profound cultural richness of the source culture.

Transliteration, which comprises an estimated 21.5 percent of the known micro-level translation procedures, is identified as a component of foreignization. Transliteration inherently preserves a stronger connection with the source culture, a notion that Aixelá (1996) emphasizes. However, it is important to acknowledge that this process might create cultural distance from the target culture, as individuals reading in the target language might find it difficult to understand the cultural connotations associated with transliterated terms without additional contextual details. On the other hand, literal translation, which accounts for around 12 percent of the identified procedures, emphasizes opposition to the imposition of Western cultural hegemony (Vinay and Darbelnet, 2000). In employing a literal translation, translators strive to convey the source text in the target language in a precise, word-for-word manner. The integrity of the source material takes precedence above cultural integration. This may involve preserving cultural references, idiomatic phrases, or metaphors in their original form without modifying them to conform to the cultural context of the target language. Nevertheless, although the exact translation maintains the authenticity of the original culture, it could unintentionally disregard the contextual cues unique to the source culture. Specific cultural references that do not have direct equivalents in the target language may cause misunderstanding for the intended audience. For example, 再要碗清清凉凉的冰粉或者凉虾 (lit: order a bowl of refreshing ice powder or cold shrimps) → order some ‘liangfen’ or cold shrimp snacks. The translation “cold shrimp” for “凉虾” represented a literal rendering that has led to culturally based semantic losses. The original term does not refer to actual shrimp but rather denotes a common summer snack in the southwestern region of China. Typically made from rice or starch, the dish is shaped to resemble small shrimp swimming in water. To address this cultural nuance and enhance accuracy, a more culturally accurate translation could be “Chinese Shrimp-shaped Summer Dessert.”

Moreover, the omission, which comprises 23 percent of the micro-level translation procedures found, tends to promote the target culture (Davies, 2003). By prioritizing the readability and comprehension of the target text over the preservation of the cultural and linguistic characteristics of the source material, omission renders the translation more natural and familiar to the audience (Pedersen, 2007). Although omission improves the accessibility and understanding of the text, it could also lead to the loss of cultural connotations, thereby substantially affecting semantic accuracy. In addition, 9.75% of the reported micro-level transliteration plus explanation, while aiming to strike a balance between target and source cultures, carries the inherent risk of culturally based semantic losses if the translator falls short in effectively translating the cultural references. If inadequately executed, the preservation of phonetic representation through transliteration may not suffice to convey the nuanced cultural meanings, and the explanatory component in the target language might not fully bridge the cultural gap. For example, 寺院的喇嘛们会戴上面具跳神 (lit: The lamas in the monastery will wear masks and perform dances) → Cham dance (跳神; Tiàoshén), a masked and costumed dance by monks. In this context, the use of transliteration (跳神; Tiàoshén) aimed to retain the phonetic representation of the original term, while the explanation provided an interpretation in English. However, this approach may result in culturally based semantic losses. The term “跳神” itself may have broader cultural and spiritual connotations beyond a mere dance. The explanation “a masked and costumed dance by monks” provided a description but might not capture the full depth and significance of the Cham dance within the cultural and religious practices of Tibetan Buddhism. It is crucial for translators to employ this strategy to ensure a meticulous and culturally informed approach, taking into account the subtleties and connotations embedded in the cultural references to mitigate the potential for semantic losses.

The utilization of literal translation, transliteration, and a combined usage of transliteration plus literal translation comprise most of the identified translation procedures. Their objective is to deliberately provide a heightened sensation of foreignness to the target text, thus preserving the authenticity of the initial cultural context. Foreignization is consistent with a broader theoretical framework that prioritizes the conservation of cultural diversity in translational endeavors. In addition to embodying a dedication to faithful linguistic representation, this approach aims to facilitate a more sophisticated intercultural dialog in translation. Furthermore, this approach emphasizes the translators’ ability to negotiate the power relations intrinsic to cross-cultural communication; hence, it contributes to a larger academic conversation regarding cultural autonomy and representation in translation studies. According to the present study’s findings, although foreignization effectively preserves the cultural distinctiveness of the source materials, it may unintentionally result in culturally based semantic losses, particularly in terms of acceptability and accuracy of the nuanced cultural interpretation for the target audience. When used at the macro-level, the foreignizing method increases the preservation of cultural connotations inherent in source texts. Specifically, the subtle application of transliteration contributes to the preservation of phonetic characteristics of the source language, hence assisting in the preservation of the exotic nature of the original text. However, this adherence to phonetic fidelity may sometimes result in nuanced meaning alterations that could pose a difficulty for readers, particularly those not well-versed in the original culture. In a similar vein, literal translation, although beneficial for maintaining the fundamental meaning of the source text, might not consistently communicate the complex cultural subtleties inherent in cultural references. Nevertheless, the target culture may struggle to comprehend the cultural connotations attached to the cultural references; therefore, the target audience may experience a degree of semantic loss due to the profound richness of the source culture. Thus, the present study posits that translators ought to carefully consider the effects associated with the usage of foreignization. Achieving a good equilibrium between preserving cultural connotations and minimizing semantic loss becomes crucial in fostering intercultural understanding and reducing intercultural differences. Foreignization has a multifaceted effect on translation, as it simultaneously safeguards cultural identity and poses difficulties in communicating nuanced cultural connotations. A comprehensive understanding of these influences empowers scholars to make well-informed decisions that foster effective cross-cultural communication and guarantee culturally faithful translations.

6 Discussion and conclusion

The primary goal of this study was to identify the various types of cultural connotation losses and analyze the culturally based semantic losses that occur in the English translation of cultural references found in the Chinese travel guides published by Lonely Planet. Academic investigations have emphasized the critical significance of cultural connotations inherent in cultural references when translating tourism materials for communication purposes. Nevertheless, there has been a scarcity of comprehensive academic research that has thoroughly examined the complexities associated with the losses of cultural connotations and culturally intertwined semantic losses in the translation of tourism materials, including the travel guides published by Lonely Planet.

The present study provided a multitude of contributions. To begin with, the research introduced an all-encompassing typology consisting of seven distinct types of cultural connotation losses that arise in translating cultural references. Filling an existing gap in the literature, this typology will function as a fundamental structure for subsequent investigations. Moreover, the research employs the translation quality assessment parameters proposed by Nababan et al. (2012), specifically acceptability, to detect the cultural connotations losses. This contributes to developing translation evaluation approaches that provide a trustworthy and objective method for determining whether translated materials have retained their cultural importance. Besides that, the study highlighted the cultural connotations losses are intricately connected to semantic losses. Ensuring the accuracy of translated material is critical for alerting translators about possible losses and providing direction for generating more sensitive translations to cultural differences. Additionally, the study illuminated that dominant translation procedures, such as transliteration, literal translation, and explanation, offer valuable insights into translators’ choices in handling cultural references. This knowledge guides optimal translation decisions, underscoring the significance of selecting suitable procedures to preserve cultural authenticity.

7 Implications and limitations

The study’s findings have twofold implications, extending to theoretical and practical areas. On the one hand, theoretical implications concern the practical implementation of pertinent theories in subsequent research endeavors. At present, the realm of cultural connotation losses within the framework of tourism is an area that has received limited attention in the academic community. The lack of scholarly literature and empirical research has resulted in a scarcity of understanding of the cultural connotation losses in tourism materials. The current research has not only revealed various types of cultural connotation losses that occur in translating cultural references in travel guides published by Lonely Planet, but it has also confirmed that the acceptability and accuracy criteria outlined in Nababan et al. (2012) model can be used to evaluate the quality of translations containing culturally linked semantic losses in the tourism industry. Furthermore, the model put forth in this research exhibits generalizability beyond the domain of travel guides, including a wide range of textual genres. Furthermore, the extent to which these cultural connotation losses result in semantic losses has emphasized the critical significance of semantic meanings in determining the quality of translation. Demonstrating expertise in managing semantic losses influenced by culture enables translators to effectively choose translation procedures, resulting in maximum persuasive effectiveness and, thus, accomplishing the primary communicative goals inherent in tourism materials. On the other hand, the practical implications encompassed approaches for enhancing workshops and training programs for translators to attain the expected objectives of tourism promotion. The present study’s findings suggest that training initiatives and acquainting translators with the different types of losses that can occur during the translation of cultural references can foster the development of a new cohort of translators who possess the necessary abilities to effectively navigate cultural nuances. Furthermore, the practical implications encompass the improvement of translator training programs’ effectiveness in achieving the desired results of attracting tourists.

However, it should be noted that this research is subject to specific limitations. Examining culturally based semantic losses in the English translations of Chinese cultural references within the context of Lonely Planet’s travel guides for Beijing, Shanghai, and Sichuan is the primary subject of this research. The lack of universal applicability of the findings to other travel guides or genres restricts the study’s conclusions from being used in a wider translation context. China’s extensive cultural diversity comprises many regions, each characterized by unique cultural characteristics. Although the research examined three notable locations, it is challenging to portray the culturally diverse nuances throughout China comprehensively. Thus, the study’s findings are regionally restricted and do not capture the full scope of culturally associated semantic losses in Chinese cultural references. An additional limitation arises from the subjective nature of assessing cultural connotations. Given the complex and multidimensional nature of cultural subtleties and meanings, the assessment process inevitably incorporates subjective opinion. Despite the use of in Nababan et al. (2012) translation quality assessment parameters and a peer review process in this study, the subjective and interpretive nature of these evaluations potentially influences the quantification and categorization of losses associated with cultural connotations.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

SC: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. TZ: Data curation, Project administration, Software, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Agorni, M. (2012). Tourism communication: the translator’s responsibility in the translation of cultural difference. J. Tourism Cult. Herit. 10, 5–11. doi: 10.25145/j.pasos.2012.10.048

Alwazna, R. Y. (2014). The cultural aspect of translation: the workability of cultural translation strategies in translating culture-specific texts. Life Sci. J. 11, 182–188.

Amenador, K. B., and Wang, Z. (2022). The translation of culture-specific items (CSIS) in Chinese-English food menu corpus: a study of strategies and factors. SAGE Open 12:215824402210966. doi: 10.1177/21582440221096649

Amenador, K. B., and Wang, Z. (2023). The image of China as a destination for tourist: translation strategies of culture-specific items in the Chinese-English food menus. SAGE Open 13:21582440231196656. doi: 10.1177/21582440231196656

AmirDabbaghian, A. (2014). Translation and tourism: a cross cultural communication and the art of translating menus. J. Basic Appl. Sci. Res. 4, 11–19.

Amiri, E. S., and Tabrizi, H. H. (2018). The study of English culture-specific items in Persian translation based on House’s model: the case of waiting for Godot. Int. J. Engl. Linguist. 8:135. doi: 10.5539/ijel.v8n1p135

Baker, M. (2018). In other words: a coursebook on translation. 3rd Edn. Abingdon, Oxon; New York, NY: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315619187

Chen, S., Mansor, N. S., Mooisan, C., and Abdullah, M. A. R. (2023b). Examining cultural words translation in tourism texts: A systematic review. JLTR 14, 499–509. doi: 10.17507/jltr.1402.26

Chen, S., Shahila Mansor, N., Mooisan, C., and Redzuan Abdullah, M. A. (2023a). Exploring cultural representation through tourism-related cultural words translation on Hangzhou tourism website. World J. Engl. Lang. 13:168. doi: 10.5430/wjel.v13n2p168

Chiaro, D., and Rossato, L. (2015). Food and translation, translation and food. Translator 21, 237–243. doi: 10.1080/13556509.2015.1110934

Chung, F. M. Y. (2021). Translating culture-bound elements: a case study of traditional chinese theatre in the socio-cultural context of Hong Kong. Fudan J. Hum. Soc. Sci. 14, 393–415. doi: 10.1007/s40647-021-00322-w

Cronin, M. (2000). Across the lines: Travel, language, translation. Cork, Ireland: Cork University Press.

Dann, G. (1996). The language of tourism: A sociolinguistic perspective. Wallingford, Oxon: CAB International.

Davies, E. E. (2003). A goblin or a dirty nose? The treatment of culture-specific references in translations of the Harry potter books. Translator 9, 65–100. doi: 10.1080/13556509.2003.10799146

De Marco, A. (2015). Are green-lipped mussels really green? Touring New Zealand food in translation. Translator 21, 310–326. doi: 10.1080/13556509.2015.1103098

Demir, D., and Genç, A. (2019). Academic Turkish for international students: problems and suggestions. Dil ve Dilbilimi Çalışmaları Dergisi 15, 34–47. doi: 10.17263/jlls.547601

Dimitrieska, S., and Efremova, T. (2021). Colors in the International Marketing. Entrepreneurship 9, 78–86. doi: 10.37708/ep.swu.v9i1.7

Elliott, R., and Timulak, L. (2015). Descriptive and interpretive approaches to qualitative research. Oxford University Press. Oxford.

Farkhan, M., Naimah, L. U., and Suriadi, M. A. (2020). Translation strategies of food-related culture specific items in Indonesian subtitle of Netflix series the final table. Insaniyat: J. Islam Human. 4, 149–162. doi: 10.15408/insaniyat.v4i2.14668

Federici, E. (2007). What to do and not to do when translating tourist brochures. Università di pisa dipartimento di anglistica Pisa

Gandin, S. (2013). Translating the language of tourism. A Corpus based study on the translational tourism English Corpus (T-TourEC). Procedia. Soc. Behav. Sci. 95, 325–335. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.10.654

Gao, X., Gu, Z., Niu, S., and Ryu, S. (2022). Effects of international tourist flow on startup financing: investment scope and market potential perspectives. SAGE Open 12:215824402211264. doi: 10.1177/21582440221126455

Guo, Q. (2017). Translation practice of tourism resources excerpts from "lonely planet: Northeast China", Harbin Normal University). Harbin

Hancock, B., Ockleford, E., and Windridge, K. (2009). An introduction to qualitative research: The NIHR research Design Service for Yorkshire & the Humber. The NIHR RDS EM/YH. London

Harutyunyan, K. (2015). Colour terms in advertisements. Armenian Folia Anglistika 11, 55–67. doi: 10.46991/afa/2015.11.2.056

Hashim, B. A. (2023). The impact of cultural differences in translation from English into Arabic, University of Basrah). Basrah

Hogg, G., Liao, M.-H., and O’Gorman, K. (2014). Reading between the lines: multidimensional translation in tourism consumption. Tour. Manag. 42, 157–164. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2013.10.005

Horbačauskienė, J., Kasperavičienė, R., and Petronienė, S. (2016). Issues of culture specific item translation in subtitling. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 231, 223–228. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.09.095

Islam, S. (2018). Semantic loss in two English translations of surah Ya-sin by two translators (Abdullah Yusuf Ali and Arthur John Arberry). IJLLT 1, 18–34. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3477133

Kamalizad, J., and Khaksar, M. (2018). Translation quality assessment of Harry potter and the cursed child according to house’ TQA model. DJ J. English Lit. 3, 11–18. doi: 10.18831/djeng.org/2018021002

Karimnia, A., and Heydari Gheshlagh, N. (2020). Investigating culture-specific items in Roald Dahl’s “Charlie and chocolate factory” based on Newmark’s model. Int. J. Engl. Lang. Educ. 5, 1–12. doi: 10.29252/ijree.5.2.1

Katan, D. (2009). “Translation as intercultural communication” in The Routledge Companion to Translation Studies. ed. J. Munday (London: Routledge)

Kelly, D. (1997). The translation of texts from the tourist sector: textual conventions, cultural distance and other constraints. Trans 2, 33–42.

Kim, H., and Kim, J. (2015). A study on translation strategies of culture-specific items. Meta 60:350. doi: 10.7202/1032901ar

Krippendorff, K. (2018). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. Sage Publications. Thousand Oaks, CA

Kuleli, M. (2019). Identification of translation procedures for culture specific items in a short story. Dil ve Dilbilimi Çalışmaları Dergisi 15, 1105–1121. doi: 10.17263/jlls.631551

Larson, M. L. (1998). Meaning-based translation: A guide to cross-language equivalence. 2nd. Lanham, Md: University Press of America.

Li, H. (2018). Translation-oriented text analysis model-guided practice of English-Chinese translation of tourist guides: A case study of "lonely planet: Netherlands", Xi'an International Studies University. Xi'an

Li, Q., Ng, Y., and Wu, R. (2022a). Strategies and problems in Geotourism interpretation: a comprehensive literature review of an interdisciplinary Chinese to English translation. Int. J. Geoheritage Parks 10, 27–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgeop.2022.02.001

Li, Q., Wu, R., and Ng, Y. (2022b). Developing culturally effective strategies for Chinese to English Geotourism translation by Corpus-based interdisciplinary translation analysis. Geoheritage 14:6. doi: 10.1007/s12371-021-00616-1

Lin, C. L. (2021). A comparative study of cultural references between the Spanish and Chinese versions of Seville’s travel guidebook as a case study. SKASE J. Transl. Interpret. 14, 36–61.

Lyu, J., Huang, H., and Mao, Z. (2021). Middle-aged and older adults’ preferences for long-stay tourism in rural China. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 19:100552. doi: 10.1016/j.jdmm.2020.100552

Maasoum, S. M. H., and Davtalab, H. (2011). An analysis of culture-specific items in the Persian translation of “Dubliners” based on Newmark’s model. TPLS 1, 1767–1779. doi: 10.4304/tpls.1.12.1767-1779

Mansor, I. (2012). Acceptability in the translation into Malay of Rihlat Ibn Battutah. Kemanusiaan: Asian J. Humanit. 19, 1–18.

Marco, J. (2019). The translation of food-related culture-specific items in the Valencian Corpus of translated literature (COVALT) corpus: a study of techniques and factors. Perspectives 27, 20–41. doi: 10.1080/0907676X.2018.1449228

Marhamah, Z., Holila, A., and Zainuddin, (2021). Translation quality of subtitle text in Greta’s movie: 6th annual international seminar on transformative education and educational leadership (AISTEEL 2021), Medan, Indonesia.

Meng, X. (2019). Lonely planet: China (excerpt) English-to-Chinese translation practice report, Northwest Normal University). Lanzhou

Merriam, S. B., and Tisdell, E. J. (2015). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. John Wiley & Sons. Hoboken, NJ

Nababan, M., Nuraeni, A., and Sumardiono, (2012). Pengembangan Model Penilaian Kualitas Terjemahan Mangatur Nababan, dkk. Kajian Linguistik Dan Sastra 24, 39–57.

Nedergaard-Larsen, B. (1993). Culture-bound problems in subtitling. Perspectives 1, 207–240. doi: 10.1080/0907676X.1993.9961214

Olk, H. M. (2012). Cultural references in translation: a framework for quantitative translation analysis. Perspectives 21, 344–357. doi: 10.1080/0907676X.201.646279

Oster, U., and Molés-Cases, T. (2016). Eating and drinking seen through translation: a study of food-related translation difficulties and techniques in a parallel corpus of literary texts. Across Lang. Cult. 17, 53–75. doi: 10.1556/084.2016.17.1.3

Palinkas, L. A., Horwitz, S. M., Green, C. A., Wisdom, J. P., Duan, N., and Hoagwood, K. (2015). Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 42, 533–544. doi: 10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y

Pan, Y. (2015). English-Chinese translation report on lonely planet travel guide series: Thailand—Difficulties and methods in translating proper nouns in tourist texts, Zhejiang Gongshang University. Zhejiang

Pedersen, J. (2007). Cultural interchangeability: the effects of substituting cultural references in subtitling. Perspectives 15, 30–48. doi: 10.2167/pst003.0

Petillo, M. (2012). Translating cultural references in tourism discourse: the case of the apulian region. Altre Modernità: Rivista di studi letterari e culturali 1, 248–263.

Petrulionė, L. (2012). Translation of culture-specific items from English into Lithuanian: the case of Joanne Harris’s novels. StALan 21, 43–49. doi: 10.5755/j01.sal.0.21.2305

Poncini, G. (2006). “The challenge of communicating in a changing tourism market” in Translating tourism: Linguistic/cultural representations. eds. O. Palusci and S. Francesconi (Trento: Università degli Studi di Trento Editrice), 15–34.