94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Front. Commun., 11 June 2024

Sec. Health Communication

Volume 9 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2024.1331139

This article is part of the Research TopicAnti-Stigma Communication in the 21st Century: Theory, Research, and ApplicationsView all 7 articles

Destigmatization is a crucial step toward achieving societal equality. Media contribute both to the stigmatization and destigmatization of various groups. Through a systematic literature review, the present study aims to develop a comprehensive overview of destigmatization in the context of media and communication. A final sample of 79 scientific publications was analyzed and synthesized. First, a systematically derived, interdisciplinary applicable definition of destigmatization is presented. Second, an overview of factors influencing destigmatization is given, categorized into four factor groups: contact, education, language and terminology, and framing. Third, the processual character of destigmatization, referring to reflexive and rule-based processes, is discussed. This systematic literature review emphasizes the responsibility and potential positive impact of media and communication for destigmatization. The findings provide a basis for adaptation and expansion by future research focusing on various stigmatized groups and settings.

Stigmatization is a problem—individuals are denied their individuality, are classified into groups, are reduced to certain characteristics, and have to deal with negative consequences in various aspects of life (e.g., Corrigan, 2004; Hajebi et al., 2022). Stigmatization is connected to the rejection of “basic human values, such as social acceptance, tolerance, civil rights, and […] societal resources” (Chung and Slater, 2013, p. 896). Because of their group membership, stigmatized individuals are excluded from full societal participation (Read and Harper, 2022). That is an ethical problem because stigmatized individuals are treated in an unequal way (Heney, 2022). Stigmatization affects a broad range of groups and—through changes in individual life situations and societal power relations—can potentially affect everyone.

Previous research demonstrates that stigmatization can be reinforced by media portrayals (e.g., Ma, 2017; Kosenko et al., 2019). At the same time, media can also contribute to destigmatization (e.g., Clement et al., 2013). As stigmatization influences the opportunities of stigmatized individuals, destigmatization can have wide-ranging effects on their quality of life too. We therefore need more insights into factors influencing destigmatization, how this process evolves, and—first of all—how destigmatization is defined. Therefore, the potential and responsibility of media and communication for destigmatization should be emphasized.

Research on stigmatization and destigmatization is multi- and interdisciplinary, including, for example, studies from sociology, psychology, and political science (Link and Phelan, 2001). Various studies have explored how media should be designed to destigmatize in a specific context. For example, there are studies on films (e.g., Chung and Slater, 2013), news articles (e.g., Ramasubramanian, 2007), and celebrities (e.g., Hoffner and Cohen, 2018) influencing destigmatization. Studies focus on stigmatized groups like people with depression (e.g., Martin et al., 2022), homeless people (e.g., Bartsch and Kloß, 2019), or people with eating disorders (e.g., O’Hara and Smith, 2007). Implemented methodological approaches include experiments (e.g., Winkler et al., 2017), focus group interviews (e.g., Hajebi et al., 2022), and content analyses (e.g., Yang et al., 2017), among others. To the best of the author’s knowledge, what is missing is a comprehensive systematic literature review to compile evidence on destigmatization in the context of media and communication.

The present study aims to close this research gap. Previous systematic literature reviews on mass media interventions (Clement et al., 2013), or more specifically on video interventions (Janoušková et al., 2017), have focused on the destigmatization of people with mental health problems. Other reviews have concentrated on stigmatization rather than destigmatization, either in general (e.g., Taft and Keefer, 2016) or within the context of media (e.g., Wanniarachchi et al., 2020). Again, these reviews addressed one specific stigmatized group. The present systematic literature review does not focus on one concrete stigmatized group or a particular media intervention. Additionally, it emphasizes destigmatization rather than stigmatization. In doing so, this review aims to refocus the research landscape to actively contribute to positive changes for stigmatized individuals. Research on destigmatization is of importance as stigmatization affects individuals, hindering their well-being and societal integration. Therefore, destigmatization efforts are imperative to counteract these effects and strive toward equality and inclusivity. Developing a collective understanding of destigmatization is crucial. Only by comprehensively investigating the processes underlying destigmatization can we effectively support and catalyze such efforts in everyday life. While various research approaches exist, bringing them together is essential for a holistic understanding. Adopting a future-oriented perspective, this study calls for sustainable societal change.

This systematic literature review is structured by three research questions. First, it asks for a systematically derived definition of destigmatization (RQ1). Research often does not provide an explicit or consistent definition of stigmatization (Link and Phelan, 2001). The same can be observed for destigmatization. With a systematically derived definition of destigmatization, the scope of destigmatization as well as the relationship between stigmatization and destigmatization can be evaluated, and a framework for destigmatization strategies can be fostered. Furthermore, this review wants to derive an overview of factors influencing destigmatization in the context of media and communication, their efficacy, and their respective theoretical backgrounds (RQ2). There are studies on effective media interventions for destigmatization (e.g., Brown, 2020; Neubaum et al., 2020), but a comprehensive overview of factors is missing. Therefore, this overview is needed as a starting point for the development of interventions by researchers and media practitioners. Finally, this systematic literature review is aimed at uncovering theoretical mechanisms related to the processual character of destigmatization (RQ3). Again, knowledge about these mechanisms is crucial for the development of successful interventions.

To answer these research questions, a final sample of 79 papers published in English were read and analyzed. The aim of this review is to unveil common ground between interdisciplinary research efforts on destigmatization in the context of media and communication as a starting point for both future research and practitioners with the intention of developing destigmatizing media content and communication strategies. Before the review’s findings are summarized and discussed, the methodological approach, structured in three stages, is described. The article ends with a conclusion and recommendations for further research. Detailed information on the systematic literature review’s objectives and scope, as well as on the sampling process and category system used for the data extraction, is documented in the review protocol (available via OSF: https://bit.ly/3xsuZ1e).

A systematic literature review (SLR) is a suitable method for addressing the intended research objectives, as it enables the exploration of a broad, heterogeneous, and interdisciplinary research field in a reproducible and reliable way (Rogge et al., 2024). The methodological approach is based on the recommendations of Petticrew and Roberts (2006) and the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) checklist, as well as corresponding recommendations for systematic literature reviews (Page et al., 2021), and the STAMP method (Rogge et al., 2024). Two types of literature reviews—a scoping review and a theoretical review—were combined to connect the summarization of prior knowledge with further explanation building through a comprehensive search strategy (Paré et al., 2015). The sampling process of the SLR was standardized across three stages to determine eligible publications: a systematic search for relevant publications, an abstract-based screening (ABS) of these publications, and a full-text reading (FTR) of the remaining publications to build a final sample for the synthesis. Throughout the sampling process, a publication had to fulfill four eligibility criteria: Each publication had to be a detailed scientific work in English with a thematic focus on destigmatization and a connection to media and communication. The PRISMA 2020 flow diagram of the present SLR provides a detailed overview of the sampling process (see Figure 1).

The systematic search was conducted using two databases—Web of Science Core Collection and Communication & Mass Media Complete (CMMC)—and the search engine Google Scholar. The search strategy encompassed multiple databases/search engines to combine the strengths of different platforms (Falagas et al., 2008). For the initial search, Web of Science served as an interdisciplinary basis, while CMMC offered a more specific focus on media and communication science. In the second step, these search results were extended by a Google Scholar search, as the comprehensive nature of Google Scholar is an interdisciplinary extension with publications identified as particularly relevant through the corresponding algorithm. As a search engine, Google Scholar has (theoretically) no limits regarding electronically available resources, e.g., scientific journals (Falagas et al., 2008). It was used to make sure that the full breadth of relevant literature could be identified.

Since one of the SLR’s main objectives is to define destigmatization, the search string destigma* was employed. Given the focus on internationally available publications, a search string in English language was implemented. The focus on destigmatization in the context of media and communication was not part of the search string and was only evaluated beginning with the ABS stage. As a result, the search string is more sensitive and less specific regarding media and communication, and more specific yet less sensitive concerning destigmatization.

For Google Scholar, a slightly adapted search string was used: destigmatization AND media. Given the substantial volume of search results (for the adapted search string there were still around 10,000 results, depending on the time and device used for the search) and Google Scholar’s automatic incorporation of synonyms into the search, this adjustment was made to ensure a higher yield of relevant results. Patents and citations were excluded from the search. As Google Scholar mainly serves as a validation source regarding the search results extracted from Web of Science and CMMC, only the first 300 search results were extracted. The results were sorted by relevance, meaning that the first pages of Google Scholar, based on a qualitative assessment, probably already included the most important publications. Nevertheless, it should be borne in mind that there is no transparent information about the algorithm Google Scholar uses to rank the search results.

The final search and download of the respective datasets of the two databases and the search engine were conducted on 13/14 February 2023. There were no restrictions regarding the earliest publication year. Finally, the search yielded 1,452 results (Web of Science n = 869; CMMC n = 283; Google Scholar n = 300). The three datasets were merged into one, which was then carefully examined for duplicates, both within and across the three sources. Automated and nonautomated techniques were used to search for duplicates (e.g., based on the titles of publications). A total of 123 duplicates were identified. The duplicate entries were merged, combining the information of both entries. Afterwards, one entry from each set of duplicate entries was removed from the dataset. Additionally, 60 more cases were excluded as they fell into publication types beyond the SLR’s eligibility criteria (i.e., abstract, bibliography, book/film/product review, excerpt, letter/note, meeting abstract, news item). This led to a sample of 1,269 publications after the systematic search.

The aim of the abstract-based screening (ABS) was to determine the relevance and eligibility of the 1,269 publications. To ensure the reproducibility of this screening process, four ABS criteria along with a corresponding scoring technique were established. An eligible publication had to fulfill the following ABS criteria/categories:

1. The publication must primarily focus on destigmatization. If destigmatization is only mentioned as a challenge in the abstract’s conclusion, then the publication is excluded.

2. The publication must include a connection between destigmatization and media or communication. This may involve interventions through media such as films, adjustments in terminology, or the use of specific styles such as narrativity. The emphasis on media and communication does not have to be the thematic focus of the publication (like it has to be for destigmatization/ABS criterion 1).

3. The publication must be written in English.

4. The publication must be a detailed scientific work (e.g., journal article, book chapter, proceedings paper).

A codebook describing the ABS criteria and the ABS procedure was prepared. Afterwards, a pretest of the ABS was conducted. To evaluate a publication regarding the four ABS criteria, both the publication’s abstract and title were thoroughly examined. In cases where no abstract was available in the dataset, the coder would conduct an online search for the accompanying abstract or examine the introduction and conclusion of the publication. Through the systematic procedure, the aim was to identify and include thematically relevant publications, covering those that may be less well known. To achieve this, the ABS was performed without disclosing the authors of the publications. This increases inclusivity and ensures that the research is as unbiased and objective as possible. To facilitate the blinded assessment of the abstracts, each publication was assigned an individual ID. For every abstract, a decision was made regarding whether each ABS criterion was met (= 1 point) or not (= 0 points). If the coder was unsure about a specific criterion, the instruction was to be inclusive (= 1 point). Subsequently, an additive ABS score for each publication was computed, ranging from 0 to 4, indicating how many ABS criteria were fulfilled. Only publications that met all four ABS criteria, resulting in an ABS score of 4, remained in the sample. After the abstract-based screening, these publications were most likely highly relevant for answering the research questions.

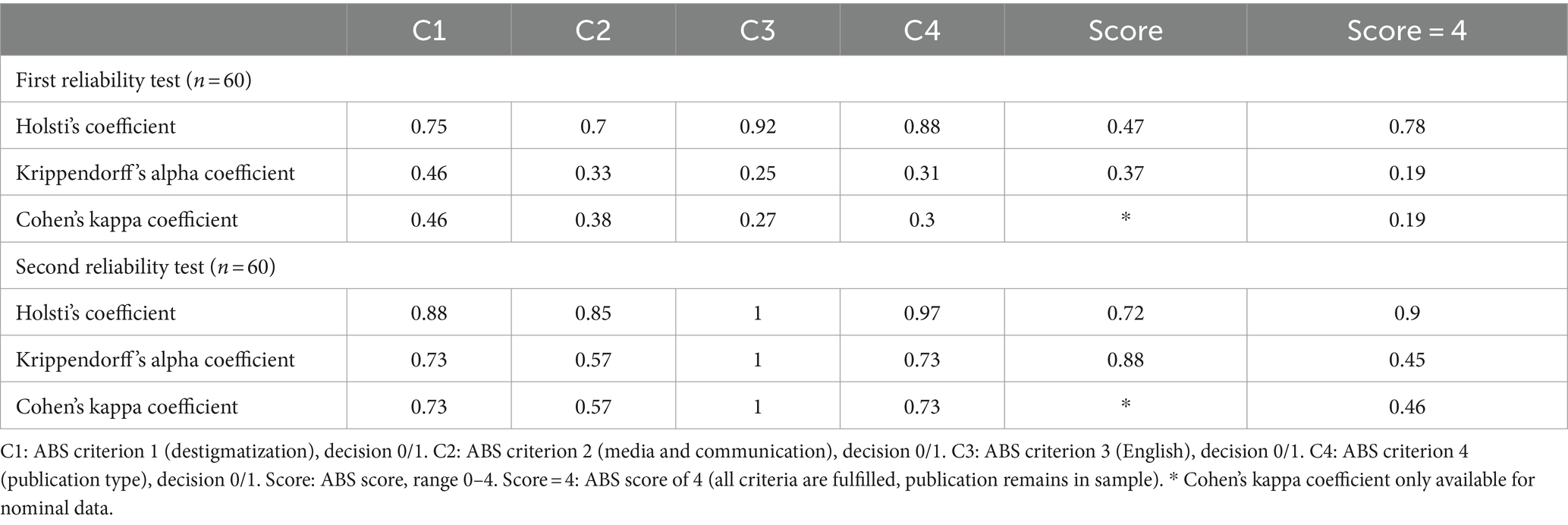

Before the ABS was employed on all of the 1,269 publications the systematic search had identified, two rounds of reliability tests of the ABS procedure were conducted to ensure that the procedure was intersubjectively comprehensible and applicable. Each round consisted of a sample of 60 publications, evaluated by two coders. This was based on a recommendation by Petticrew and Roberts (2006), who advise that around 10% of the material should be evaluated by at least two coders. As the main ABS procedure was conducted by one coder (the corresponding author of this publication), an additional coder (a research assistant) supported the reliability tests with a total of 120 publications. Before each round of reliability tests, both coders met for some training and discussed the codebook containing the ABS criteria and procedure. In the case of the second reliability test, missing agreements during the first reliability test and adjustments of the codebook were discussed. Table 1 gives an overview of the reliability coefficients (Holsti’s coefficient, Krippendorff’s alpha coefficient, and Cohen’s kappa coefficient). Values for Holsti’s coefficients indicated substantial agreement, especially after the second reliability test. Neither Krippendorff’s alpha nor Cohen’s kappa coefficients were optimal but they reached acceptable values after the second reliability test. Here, it has to be borne in mind that the homogeneity (e.g., a majority of the publications did not fulfill ABS criterion 2) and dichotomy (0/1) of most of the data may have been a problem for the usage of these coefficients (Rogge et al., 2024). During the reliability tests, it was observed that ABS criterion 2—the connection of destigmatization with media or communication—is hard to decide on, as media and communication are broad and diverse concepts. Therefore, it was even more important to be inclusive regarding ABS criterion 2 throughout the screening procedure.

Table 1. Reliability coefficients of the abstract-based screening reliability tests with two coders.

After the ABS of all of the 1,269 publications, nine duplicate publications had to be excluded. Furthermore, 1,003 publications were excluded because they had an ABS score lower than 4. This resulted in a sample of 257 eligible publications for the full-text reading.

To conduct the full-text reading (FTR) of the sample, the availability of the 257 publications as full texts had to be checked. If there was no access to a publication (e.g., because of a paywall), the authors of the publication were contacted and requested to send their publication. However, 19 publications were not available (7% of the 257 publications). Then, four FTR criteria/categories, similar to the ABS criteria, were developed to set the scope for eligible publications:

1. The publication must primarily focus on destigmatization.

2. The publication must include a connection between destigmatization and media or communication.

3. The publication must be written in English.

4. The publication must be a peer-reviewed journal article or similar (e.g., a book chapter). Other publication types, e.g., proceedings papers, are excluded.

Seven publications were excluded because they were not written in English (FTR criterion 3) and 31 because of the publication type (FTR criterion 4). That resulted in a sample of 200 publications being available for the FTR procedure. Then, a random sample of 100 cases out of the 200 publications was drawn. This decision was made according to the concept of saturation (Petticrew and Roberts, 2006). The intention behind this is that at some point the analysis of the material will be saturated and no additional new information can be derived from the remaining material. To make sure that the 100 publications that were not part of the random sample did not in fact contain any additional relevant information, the following procedure was established: After the FTR of the random sample (see the following paragraphs for a description of the FTR procedure), the titles and abstracts of the remaining 100 publications were skim-read. In other words, the ABS procedure was repeated, but with another focus: The information extracted from the random sample after the FTR was compared to the content of the abstracts and titles of the remaining 100 publications. This comparison led to the conclusion that no crucial additional information for answering the research questions of this SLR could be found in the remaining 100 publications. Consequently, it was seen as legitimate to draw a random sample of publications (n = 100) for the next steps of the SLR.

For the FTR procedure, an FTR score was developed, again ranging from 0 to 4. For each publication, it was decided whether each FTR criterion was met (= 1 point) or not (= 0 points). Only publications fulfilling all FTR criteria (FTR score of 4) remained in the sample. The FTR was performed without disclosing the authors of the publications. After the FTR, one duplicate publication and 20 publications with FTR scores below 4 were excluded. That led to a final sample of 79 publications, which was then used for the synthesis.

A category system (comparable to a traditional content analysis) was used to extract relevant information from the 79 full texts. The main focus was on the three research questions regarding: (1) the definition of destigmatization; (2) the factors influencing destigmatization and their efficacy, as well as theoretical explanations; and (3) the theoretical background of the processual character of destigmatization. Furthermore, information on the publication’s corresponding scientific discipline and country, the type of study that was conducted, the stigmatized group of interest, the publication’s research objectives, and, if applicable, the operationalization of destigmatization was collected. All information was gathered in a data extraction form.

From a methodological point of view, an additional literature search, complementary to the systematic search, is recommended (e.g., Petticrew and Roberts, 2006). For this SLR, this is especially important as the search string was focused on the term “destigmatization.” Other publications that thematically deal with destigmatization but may not use this specific term (e.g., publications on the reduction of stigmatization) were excluded. Therefore, the systematic search was accompanied by an extended sample, which was based on a hand search and included further publications. For the synthesis of the results, the focus was initially on the systematically derived publications. Then, additional information from the publications of the extended sample was included. To allow transparency and differentiation from the extended sample, an overview of the systematically derived sample is provided (see Table 2).

Before this paper focuses on the results regarding the research questions, an overview of the final sample (n = 79) of the SLR is provided. The oldest publication of the final sample dates back to 1996, while the most recent one is from 2023. An increase in the number of publications over the years can be observed, with the majority of cases in the final sample originating from 2021 and 2022. Given that the search was conducted at the beginning of 2023, there are fewer publications from this year included in the final sample. Data on a publication’s country of origin were collected based on information regarding the publication’s sample or, if not feasible, the location of the first author’s institution. Notably, most of the research emanates from the United States, accounting for 38% of the final sample, followed by Germany (11%) and the United Kingdom (10%). The majority of publications stem from the scientific disciplines of psychology and psychiatry (29%), followed by media and communication (18%), medicine (11%), and public health (10%). It is no surprise that a lot of the publications are assigned to media and communication science, as this thematic focus was one of the SLR’s eligibility criteria. Interestingly, destigmatization—even with a focus on media interventions—is predominantly addressed by health-related disciplines. Nevertheless, it is important to acknowledge that diverse scientific disciplines engage with this topic (e.g., philosophy, environmental studies, and computer science). The data collection is based on the affiliation of the first author’s institution, but it should be acknowledged that in some cases scientists from various fields collaborate in an interdisciplinary manner. A large proportion of publications conducted empirical research, with a particular emphasis on experiments (24%) and both qualitative and quantitative content analyses of diverse materials (19%). In addition, literature reviews, essays, surveys, focus group studies, and case studies, among others, are part of the final sample. It can be concluded that researchers address destigmatization with a wide range of approaches.

Furthermore, this SLR’s interest extended to the specific stigmatized groups that were the primary focus of the publications. The 79 publications of the final sample addressed 89 groups, as one publication could focus on more than one stigmatized group. Subsequently, these 89 groups of interest were categorized into 47 distinct stigmatized groups. The efforts to synthesize the data ultimately led to five overarching categories of stigmatized groups that are the focal point of the final sample:

1. Groups regarding mental health problems and mental illness in the broadest sense (47%, n = 42) (e.g., depression, schizophrenia, eating disorders)

2. Groups regarding physical health and disabilities in the broadest sense (30%, n = 27) (e.g., HIV, hearing loss, mobility disabilities)

3. Groups regarding cultural circumstances in the broadest sense (11%, n = 10) (e.g., people of color, territorial stigma, stigma of leaving religion)

4. Groups regarding social circumstances in the broadest sense (9%, n = 8) (e.g., homelessness, poverty)

5. Groups regarding gender/sexuality in the broadest sense (2%, n = 2) (e.g., homosexuality, transgender individuals)

Health-related stigma predominates the field of research, particularly with a focus on mental illness or, more broadly, mental health problems. The final sample includes publications about individuals who experience stigmatization for various conditions (e.g., homeless individuals experiencing depression; Tolomiczenko et al., 2001) or represent a specific subset of a stigmatized group (e.g., young adults). It is crucial to acknowledge that the reduction to five main categories of stigmatized groups is solely intended to facilitate an understanding of the research landscape. Therefore, this vague categorization may not sufficiently account for the individuality and, at times, the intersectionality of stigmatized individuals.

With the first research question, this review asks about the definition of destigmatization used by the authors of the publications identified as relevant. Detailed definitions of destigmatization were collected, but it was also noted when no definitions were provided and when destigmatization was solely conceptualized as work on stigmatization.

In a majority of the publications, no definition of destigmatization is provided, or the authors refer to “work on stigmatization” to define destigmatization. Four approaches can be summarized under “work on stigmatization”:

• Reducing stigma

• Combating stigma

• Stigma management

• Improvement of attitudes

First, a multitude of publications in the context of destigmatization highlight the goal of reducing stigma (e.g., Read, 2007; Chung and Slater, 2013; Ellison et al., 2015; Gray et al., 2015; Zwick et al., 2020; Chiu et al., 2021; Fachter et al., 2021; Stelzmann et al., 2021; Graham et al., 2022). In other words, diminishing stigma (e.g., Lam et al., 2016; Heney, 2022) and reducing negative attitudes (e.g., Kingdon et al., 2008) are also mentioned. A somewhat more extreme description is eradicating (e.g., Tomlinson, 2021) or eliminating stigma (e.g., Gruber, 2016). Here, destigmatization can be seen as the opposite pole of stigmatization. Second, other publications refer to combating stigma (e.g., Navon, 1996; Han et al., 2015; Settles and Furgerson, 2015; Pardo, 2018; Bartsch and Kloß, 2019; Brownstone et al., 2021). They counter stigma (e.g., Foss, 2014a; Sisson and Kimport, 2016; Dassieu et al., 2021), address stigma (e.g., Abdulai et al., 2022), challenge stigma (e.g., Rademacher, 2018), or overcome stigma (e.g., Khazaal, 2017). Furthermore, publications mention projects against stigma (e.g., Louie et al., 2019) and anti-stigma projects (e.g., Haghighat, 2001; Somasundaram, 2013; Winkler et al., 2017). Also, resistance to stigmatization (e.g., Cullen and Korolczuk, 2019; Meese et al., 2020) is described as the main mechanism of destigmatization. Here, the active fight against stigma can be seen as a dominant frame. Third, the concept of stigma management (e.g., Yodovich, 2016; Dassieu et al., 2021; Roscoe, 2021; Liu and Kozinets, 2022) is discussed. Here, the focus can be seen as finding ways to deal with stigma, which do not necessarily have to reduce or combat stigma. Fourth, some authors set the improvement of attitudes (e.g., Navon, 1996; Lebowitz and Ahn, 2012) as a goal. For instance, Yang et al. (2017) refer to Smith’s (2007) challenge communication, which includes, among others, optimism, hope, and social inclusion. With that, positive attitudes toward the stigmatized group are conveyed. Here, destigmatization can be seen as an increase in favorable attitudes.

As can be seen from the four distinct approaches regarding work on stigmatization, there is a lack of unity among scholars. This also becomes apparent through the measurement of stigmatization and destigmatization. The publications of the final sample offer a wide variety of approaches to operationalizing destigmatization, e.g., through changes in implicit or explicit attitudes (e.g., Bartsch et al., 2018), on the behavioral level (e.g., Winkler et al., 2017), or through emotions (e.g., Fachter et al., 2021), among others.

Overall, it is becoming apparent that in the vast majority of publications, no detailed, explicit definitions of destigmatization are given. Instead, destigmatization is defined in terms of work on stigmatization—as reducing stigma, combating stigma, stigma management, or improving attitudes. In this context, many publications present definitions of stigmatization. These will be discussed in the following section.

The works of Goffman (1963) and Link and Phelan (2001) are often applied as a foundation for a definition of stigma. However, Kosenko et al. (2019) describe a “fuzziness” (p. 2) regarding the conceptualization of stigma, which may be because stigma applies to so many different areas, circumstances, and disciplines. Goffman (1963) defines stigma as an “attribute that is deeply discrediting” (p. 3). In the sample of this SLR, a lot of publications refer to this attribute-oriented definition (e.g., Lavack, 2007; Yodovich, 2016; Yang et al., 2017; Stelzmann et al., 2021; Heney, 2022; Jahiu and Cinnamon, 2022). Kosenko et al. (2019) point out that—according to this definition—scholars in social psychology in particular define stigma as “a trait or mark, a seemingly objective feature of an individual, that is linked to negative stereotypes through cognitive processes” (p. 3). Problematically, this definition “emphasize[s] the observer’s view” (Kosenko et al., 2019, p. 3), leaving out the perspective of the stigmatized group.

In sociology, an extension of this attribute-oriented view is made by emphasizing the “social and contextual determinants of stigma” (Kosenko et al., 2019, p. 3). This is reflected in Link and Phelan’s (2001) definition of stigma as a process “when elements of labeling, stereotyping, separation, status loss, and discrimination co-occur in a power situation” (p. 367). After labeling differences and associating them with negative attributes, a separation between “us” and “them” is created, and finally status loss and discrimination manifest (Link and Phelan, 2001, p. 367). This shows that in the context of stigma, a distinction is made between stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination (Neubaum et al., 2020). It is emphasized that stigma does not emanate from the stigmatized group but is socially and culturally ascribed as well as produced and may not necessarily be valid, particularly since stigma “is generally based on assumptions or misconceptions” (Zwick et al., 2020, p. 1). Bullinger et al. (2023) also note that social dynamics and societal constructions reproduce discrimination and that this must be taken into account if destigmatization is to be successful. Stigma is thus a socially embedded process, as already emphasized by Goffman (1963). Han et al. (2015) state that “a stigma must be a shared evaluative belief by the community at large, not just a personal opinion on a matter, which requires the community level intervention” (p. 65). Sisson and Kimport (2016) also refer to the fact that the broader society stigmatizes when something is outside of social norms. Importantly, Link and Phelan (2001) emphasize the role of social, economic, and political power for the concept of stigma. Lundahl (2020) mentions that changes in stigmatization “do reflect the interests of the powerful” (p. 244), and Meese et al. (2020) add that systems of classification actively reproduce stigma. Liu and Kozinets (2022) also emphasize the role of power for stigma. Nevertheless, Kosenko et al. (2019) mention that this sociological definition of stigma is also criticized—as being both too narrow and too broad. A lot of publications in this SLR’s final sample include both the definitions of stigma by Goffman (1963) and Link and Phelan (2001) (e.g., Chung and Slater, 2013; Wu et al., 2018; Dassieu et al., 2021; Fan et al., 2021; Roscoe, 2021; Liu and Kozinets, 2022).

Kosenko et al. (2019) then suggest that stigma should be defined as communication-based, so that “stigma is outside of the individual and to emphasize its discursive nature” (p. 4). “To this end, we assume that stigma is constituted in messages that separate and label something as physically, behaviorally, morally, or socially deficient” (Kosenko et al., 2019, p. 4). This includes the fact that stigma can not only affect individuals but also, for example, institutions, that it can have not only negative but also positive effects (see also the concept of positive deviance, mentioned by Lundahl, 2020), and that it is transported via one or many messages (Kosenko et al., 2019). This is based on Smith’s (2007) stigma communication theory. Here, stigma provides messages in a communication context that help the community at large to identify members who are disgraced and then react accordingly. It is emphasized that stigma has social functions (Smith, 2007).

It should also be noted that a distinction is made between different forms of stigma. Heney (2022) describes social stigma, also called public stigma, which is interpersonal and takes place between the stigmatized and the nonstigmatized. Public stigma is defined by Chiu et al. (2021) in a way that “people stereotype and prejudge individuals in a minor group” (p. 3). Also, for example, Ellison et al. (2015) refer to public stigma. Furthermore, there is perceived stigma: “the awareness of public stigma, or the way individuals perceive themselves as being stigmatized and feel discriminated against by others” (Fan et al., 2021, p. 9). In addition to public stigma, Heney (2022) mentions associative stigma and structural stigma. Associative stigma attaches to people close to the stigmatized group. This is comparable to Goffman’s (1963) courtesy stigma. Structural stigma means that “societal-level conditions, cultural norms and institutional policies constrain the opportunities, resources or well-being of the stigmatized” (Heney, 2022, p. 885). These forms of stigma could lead to self-stigma (e.g., Lavack, 2007; Chiu et al., 2021; Fan et al., 2021; Heney, 2022): the internalization of stigma by the stigmatized persons themselves. Rademacher (2018), Wu et al. (2018), and Kosenko et al. (2019) distinguish between enacted stigma (e.g., experiencing discrimination), felt or perceived stigma, and internalized stigma (comparable with self-stigma).

In the final sample of this SLR—and in general—no coherent definition of stigmatization can be found. Most of the publications agree on the foundation established by Goffman (1963) and Link and Phelan (2001). What should be emphasized are the social construction of stigma, the dependence on relationships of power, and the communicative nature of stigma. Additionally, different forms of stigma (e.g., public stigma and self-stigma) should be considered. Many publications only define stigma, but a few exceptions directly define destigmatization.

It is interesting that hardly any detailed, explicitly expressed definitions of destigmatization are provided in the publications of the final sample. Only two detailed definitions can be found, one of which is used by two publications.

First, Hecht et al. (2022) use the definition of destigmatization provided by Lundahl (2020), whose publication is also part of the final sample. According to this, destigmatization is the “normalisation and acceptance of previously stigmatised groups by lessening or neutralising the negative stereotypes related to the Other, and by decreasing the degree of separation between Us and Them” (Lundahl, 2020, p. 244). This definition seems to align with the aforementioned goal of reducing stigma. Lundahl (2020) also mentions that this “assumption is so ingrained that destigmatisation is generally not even defined in destigmatisation literature” (p. 244), which could be an explanation for the missing definitions in other publications.

Second, Bullinger et al. (2023) refer to the definition of destigmatization by Lamont (2018). According to this definition, destigmatization is “the process by which low-status groups gain recognition and worth in society” (Lamont, 2018, p. 420). Throughout this process, boundaries between social groups are redrawn (Lamont, 2018). Here, activating morality plays a major role, specifically in the context of worth ascription (Bullinger et al., 2023). Bullinger et al. (2023) emphasize that “both stigma and attempts to overcome it depend on societal constructions of who is worthy and who is not” (p. 741). Accordingly, it is important to consider destigmatization at the societal level (Bullinger et al., 2023), which is a major argument for the definition of stigmatization too. Consequently, it may not only be individuals but also science, politics, and organizations that contribute to destigmatization (Lamont, 2018). This definition seems to focus on combating stigma by repositioning the social order. In the following, Lamont’s (2018) and Lundahl’s (2020) central arguments are combined to derive a comprehensive definition of destigmatization.

In light of the information just presented, to answer RQ1, this review proposes the following definition of destigmatization:

Destigmatization is the communication-based process of working on change for stigmatized groups to decrease labeling and the separation between Us and Them and to reevaluate the societal construction of who is “worthy.” This process requires not only individual but structural efforts, since power relations benefit from and therefore reproduce stigmatization, but also have the potential to produce destigmatization. Furthermore, this process is context-specific, depends on the individual backgrounds of the stigmatized groups, and different forms of stigma have to be considered. The perspective of the stigmatized group should always be asked for and included in the process of destigmatization.

With this definition, the communicative (e.g., Smith, 2007; Kosenko et al., 2019) and the processual (e.g., Link and Phelan, 2001; Lamont, 2018) character of destigmatization is emphasized. The aforementioned separation between Us and Them (e.g., Link and Phelan, 2001; Lundahl, 2020) and the element of worth (e.g., Lamont, 2018; Bullinger et al., 2023) are included. Destigmatization is viewed as a socially embedded process, depending on power relations (e.g., Goffman, 1963; Link and Phelan, 2001; Lundahl, 2020; Meese et al., 2020; Bullinger et al., 2023). Furthermore, the definition focuses on destigmatization as a work on change, appearing through different approaches (e.g., reducing stigma, combating stigma, stigma management, improving attitudes, and other opportunities like explaining the process of stigmatization). It is concluded that it has to be borne in mind that stigmatization appears for a lot of different groups and therefore destigmatization approaches have to be adjusted to individual situations and goals, including the experiences and wishes of the stigmatized themselves.

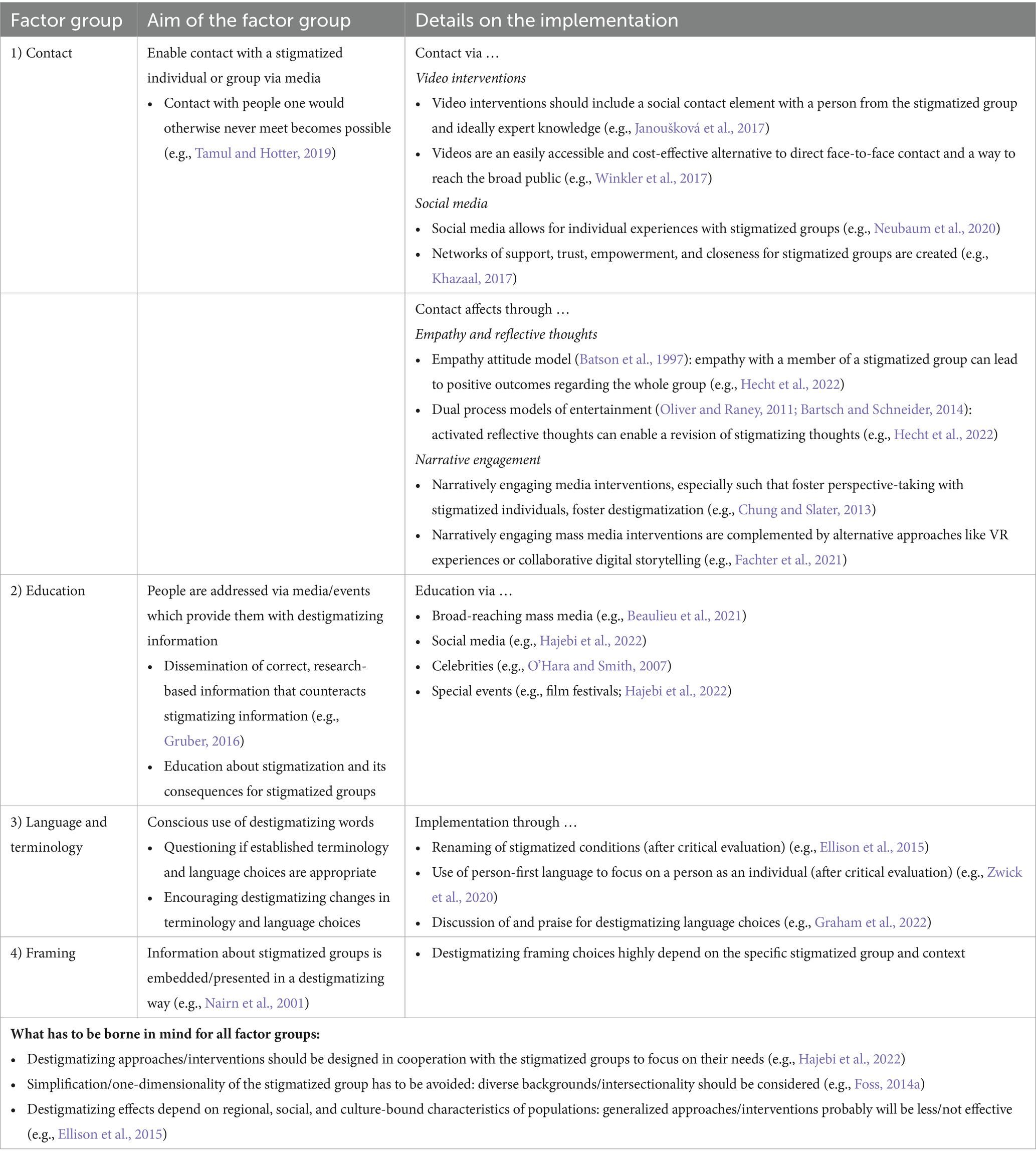

With the second research question, this review asks about factors influencing destigmatization, their efficacy, and explanations of these processes. Since the systematic literature review focuses on the context of media and communication, an overview of important factors specifically for this field is derived. As different kinds of publications were included in the literature sample (e.g., empirical studies, literature reviews, and essays), the assessment of the efficacy of factors can be based on empirical research as well as theoretically derived arguments. By reducing the extracted information from the publications of the final sample, four factor groups were identified: contact, education, language and terminology, and framing. Table 3 serves as a summary of the four factor groups.

Table 3. Factors influencing destigmatization in the context of media and communication identified through the systematic literature review.

Contact with a stigmatized person or group via media can contribute to destigmatization through various mechanisms such as empathy. Thirty-one publications (39%) from the final sample that can be mainly attributed to the contact factor group were identified. This contact can take place via, for example, social media, entertaining films, or news stories, can involve fictional or real people, and can target other stigmatized group members or out-group members. Regardless of the form the contact takes, the media bear a great responsibility here, as they enable contact with people we would otherwise never meet (Tamul and Hotter, 2019). In the final sample, four focal points that receive notable emphasis for influencing destigmatization were identified: video interventions, empathy and reflective thoughts, narrative engagement, and social media.

In their review on video interventions as a tool for destigmatizing mental illness among young people, Janoušková et al. (2017) conclude that video interventions are an effective strategy for destigmatization. To successfully destigmatize, video interventions should include a social contact element with a person from the stigmatized group and additional expert information (see factor group education). In an experiment, Winkler et al. (2017) compared a short video intervention with an informational leaflet and an educational seminar and found that all three interventions were able to reduce stigmatizing attitudes and behavior, with the seminar (Cohen’s d = 0.61/d = 0.58) being the most effective, followed by the video (d = 0.49/d = 0.35) and the flyer (d = 0.25/d = 0.01). A three-month follow-up assessment did show that the video (d = 0.22/d = 0.21) was still effective in reducing stigmatization, but the seminar (d = 0.43/d = 0.26) was more effective once again (flyer: d = 0.05/d = 0.04). Both the intergroup contact hypothesis (Allport, 1954; Pettigrew, 1998) and the parasocial contact hypothesis (Schiappa et al., 2005) serve as theoretical explanations for the efficacy of video interventions. Here, it is important to bear in mind that videos are easily accessible and cost-effective, and can reach a broader public, especially when presented via mass media. Overall, they do not need as many resources as destigmatization strategies with direct, face-to-face contact and are therefore recommended. One reason why video interventions are especially important for destigmatization is their potential to activate empathy (Martin et al., 2022; Mukherjee et al., 2022).

The importance of empathy for destigmatization is explained by the empathy attitude model of Batson et al. (1997, 2002), in the sense that empathy for one stigmatized individual could lead to a positive attitude change toward the whole group. For example, Hecht et al. (2022) found that empathy mediated the positive effect of both emotional background music (vs. neutral) and actual, authentic portrayals (vs. enacted, fictional) in a deep-disclosure video clip on destigmatization. We have to bear in mind that there are different subtypes of empathic feelings. In the context of Paralympic athletes, Bartsch et al. (2018) found positive mediating effects for closeness (social comparison at eye level; β = 0.15) and feelings of elevation (upward comparison; β = 0.21/β = 0.11) on destigmatization, but a negative effect for pity (β = −0.05). Pity is a more ambivalent form of empathy and includes downward comparison and false superiority, whereas for closeness, viewers learn that they share experiences, goals, and concerns with the portrayed stigmatized persons.

Another mediator of the effects of emotional background music and veracity on destigmatization identified by Hecht et al. (2022) is the variable increased reflective thoughts. Additionally, empathy had a statistically significant indirect effect via reflective thoughts on destigmatization (β = 0.27 for Hecht et al., 2022; β = 0.13 for Bartsch et al., 2018). And there was a statistically significant direct effect (β = 0.41) of reflective thoughts on destigmatization (Hecht et al., 2022). The importance of reflective thoughts is explained by dual process models of entertainment (Oliver and Raney, 2011; Bartsch and Schneider, 2014), in the sense that eudaimonic (vs. hedonic) entertainment experiences, and therefore moving and thought-provoking experiences, lead to prosocial outcomes in such a way that the recipients rethink their stereotypes. Hecht et al. (2022) thus emphasize the potential of eudaimonic entertainment even outside of fictional entertainment. This is an important finding, since “the cognitive mechanisms of how media messages can reduce mental health stigma are still unclear” (Hecht et al., 2022, p. 368). In summary, some subtypes of empathy and the activation of reflective thoughts are substantial facilitators for successful destigmatization.

Narrative engagement is another important concept that has to be considered for successful contact interventions through media. Tamul and Hotter (2019) found that news stories told by a stigmatized person led to recipients’ emotional engagement and cognitive immersion into the narrative, and with that, reduced stigma. Therefore, media producers like journalists not only have to create accurate reporting but also “storytelling that is well-written, coherently organized, immersive, and emotionally engaging” (Tamul and Hotter, 2019, p. 20). Similarly, perspective-taking is described as the “most important element of narrative engagement with respect to reducing stigma” (Chung and Slater, 2013, p. 906). Perspective-taking as one dimension of identification highlights the individuality and complexity of others, helps to understand their emotions and thoughts, and therefore normalizes and humanizes stigmatized others (Chung and Slater, 2013). Chung and Slater (2013) did not find statistically significant effects for other dimensions of the identification construct or overall identification, but they did for perspective-taking. On the other hand, Johnson (2008) generally emphasizes the importance of identification with a character for destigmatization. In this context, it is worth considering the results of Entertainment-Education, the Extended Elaboration Likelihood Model, and the Entertainment Overcoming Resistance Model (De Ridder et al., 2023). Next to these mass media-based contact interventions, studies of the final sample also considered alternative approaches such as contact via VR videos, which can foster destigmatization, when a character seems likable (Stelzmann et al., 2021). Another possibility is collaborative digital storytelling, where individuals work together to build a joint narration, e.g., based on textual and graphical elements, thereby learning more about stigmatized groups (Fachter et al., 2021). To summarize, narratively engaging media interventions, especially those that foster perspective-taking with stigmatized individuals, can cause destigmatizing effects.

Social media is an important space for solidarity for members of stigmatized groups to meet and discuss their experiences. Here, stigmatized groups have more control over their presentation (e.g., compared to mass media), and they can create and share counternarratives, and challenge the dominant discourse (Khazaal, 2017; Meese et al., 2020; Liu and Kozinets, 2022). Networks of support, trust, and closeness can be created. Through visual presentations, this can even happen without language barriers (Pardo, 2018). Stigmatized persons who share experiences on social media platforms like YouTube are seen as advocates who—through their transparency and bravery—empower other stigmatized group members (Johnson et al., 2021; King and McCashin, 2022). Another example of engaging social media interactions is memes, which are an effective tool for encouraging other people to produce their own destigmatizing content (Tomlinson, 2021).

Other forms of human-human interaction via social media are destigmatizing too (Song et al., 2011; Wu et al., 2018). While Wu et al. (2018) found support for the intergroup contact hypothesis (Allport, 1954; Pettigrew, 1998), Neubaum et al. (2020) found additional support for the media-focused parasocial contact hypothesis (Schiappa et al., 2005) in the context of social media. Interpersonal mediated contact between users and celebrities from the stigmatized group (e.g., the number of times users received comments and messages from a celebrity via social media) increases tolerance (β = 0.14) and acceptance (β = 0.26) (Wu et al., 2018). Additionally, passive browsing through the personal social media profile of a member of a stigmatized group with neutral or positive information on their daily life fostered destigmatization (compared to a profile without information about the stigmatized group membership) (Neubaum et al., 2020). It can be concluded that social networking profiles address the lack of experience with stigmatized groups, provide information, and therefore allow for contact with groups people usually do not have much contact with.

In the sample of this SLR, nine out of 79 publications (11%) focus on education in order to foster destigmatization. It is noticeable that publications regarding the factor group education often appear in the context of mental illness (e.g., Roberts et al., 2013; Louie et al., 2019; Hajebi et al., 2022). The central approach of this factor group is that people from the out-group are addressed via mass media and provided with information. This can be the dissemination of correct, research-based information that counteracts stigmatizing information (Gruber, 2016; Hajebi et al., 2022) and also education about stigmatization and its consequences for stigmatized groups. Because of their broad reach, mass media are a reasonable opportunity to educate people (Beaulieu et al., 2021). Social media (Hajebi et al., 2022) and support from celebrities (O’Hara and Smith, 2007; Hajebi et al., 2022) are supposed to be especially effective in promoting education. Also, film festivals (Hajebi et al., 2022) and literary works and their discussion via media (Somasundaram, 2013) are mentioned as examples of ways to educate the broad public.

It is often mentioned that education interventions should be designed through cooperation between media specialists and experts regarding the stigmatized group (e.g., psychotherapists as experts for the stigmatization of people with mental illness, or stigmatized persons themselves). Here, it should be noted that on the one hand, we need experts as educators (Somasundaram, 2013; Louie et al., 2019) and media producers like journalists should be trained by experts (Roberts et al., 2013; Stelzmann et al., 2020; Hajebi et al., 2022), as media producers sometimes do not seek correct and destigmatizing background information on their own (O’Hara and Smith, 2007). On the other hand, experts (e.g., psychotherapists) will not have enough time to train media producers or appear in interviews, it is not the responsibility of stigmatized persons to educate the broad public, and we need knowledge regarding the media production of media specialists. So, we need both the openness of experts regarding stigmatized groups for the support of media production and the initiative of media producers to contact experts and include correct, destigmatizing information. Finally, it is important to avoid simplification of the stigmatized group while attempting to educate. For successful educational destigmatization strategies, stigmatized people have to be presented with diverse backgrounds, ethnicities, and as far as possible, their individuality (O’Hara and Smith, 2007; Foss, 2014a).

Another nine publications (11%) from the final sample focus on language and terminology as a factor group influencing destigmatization. Here, Zwick et al. (2020) argue: “There are many ways to contribute to a more accepting society, but it starts with bottom-up processes like language choices” (p. 3). Therefore, the factor group language and terminology mainly focuses on the conscious use of words, as words matter.

Labels can serve as cues that activate stigma (Lam et al., 2016). We have to discuss whether the terminology established over the years is still appropriate. Different studies have focused on the renaming of stigmatized conditions like schizophrenia (e.g., Ellison et al., 2015) and epilepsy (e.g., Isaza-Jaramillo et al., 2020). These studies conclude that decisions to rename stigmatized conditions should be made with caution, because of the complex influence of labels on stigmatization. Renaming has the potential to reduce stigma (Chiu et al., 2021), whereas other studies found that alternative terminology could even increase stigmatization (Ellison et al., 2015). Furthermore, different studies argue for the use of person-first language (Zwick et al., 2020; Graham et al., 2022), in order to focus on a person as an individual. However, person-first language is not always effective in reducing stigmatization (Isaza-Jaramillo et al., 2020). Here, we have to bear in mind that language and terminology depend on regional and culture-bound characteristics of populations (Palm, 2012; Isaza-Jaramillo et al., 2020). Therefore, generalized and standardized interventions will probably not always be effective.

Graham et al. (2022) found that medical, epidemiological, public health, and mental health communities on Twitter already do not often use stigmatizing language and the use is even decreasing. But the explicit use of destigmatizing language could be higher and the presence of destigmatizing language should be actively discussed and praised. According to social learning theory (Bandura, 1977), journalists and experts should behave as role models. Then other people would observe their behavior and imitate it if destigmatizing language and terminology were encouraged. Finally, what must always be considered regarding language and terminology is what stigmatized group members need and prefer (Ellison et al., 2015). Also, by using self-chosen labels, stigmatized persons gain empowerment (Brownstone et al., 2021).

Based on the contact, education, and language and terminology factor groups, we know that the presence of stigmatized groups in the media is important for destigmatization. The way in which information is framed is another powerful mechanism, especially in mass media (Entman, 1993; Jahiu and Cinnamon, 2022). Twenty-five publications (32%) from the final sample are ascribed as part of the framing factor group.

Generally speaking, the framing of media content has to be considered regarding destigmatization (Nairn et al., 2001). However, research on framing in this context greatly depends on the specific stigmatized group. In the final sample, framing is discussed, for example, in the context of abortion stigma (e.g., Settles and Furgerson, 2015; Kosenko et al., 2019), where it is argued that abortions should be framed in the context of legal, medical settings in order to destigmatize them (Sisson and Kimport, 2016). For mental health problems, it is argued that use of the biogenetic causal explanation should stop and an evidence-based psychosocial explanation for effective destigmatization should be employed instead (Read, 2007; Read and Harper, 2022). Here, the biogenetic frame is supposed to present mental health problems as uncontrollable, therefore distance to affected people is requested, and a clear separation of groups takes place, whereas the psychosocial frame presents mental health problems as understandable reactions to life events. On the other hand, the biogenetic frame together with treatment information could have a destigmatizing role too (Lebowitz and Ahn, 2012). Dassieu et al. (2021) call for more evidence-based and less sensationalistic frames in the context of opioid use (see factor group education). With regard to obesity, framing should be employed that presents obesity as a complex multifactorial condition (Hilbert and Ried, 2009). Milfeld et al. (2021) present cultural identity mindset framing (CIMF) as an approach to emphasize connecting common-sense beliefs. It can be seen that framing depends on the stigmatized group and should also be employed based on relevant social and cultural contexts (Yoo et al., 2012; Han et al., 2015). The influence of framing in media portrayals is especially strong when people do not have their own experience with the stigmatized group (Baumann et al., 2022).

The SLR’s final sample led to four factor groups influencing destigmatization in the context of media and communication: contact, education, language and terminology, and framing. Within those factor groups, different approaches and constructs are summarized. It is noticeable that a lot of publications from the SLR’s final sample did not extensively discuss the theoretical background and the mechanisms of factors influencing destigmatization.

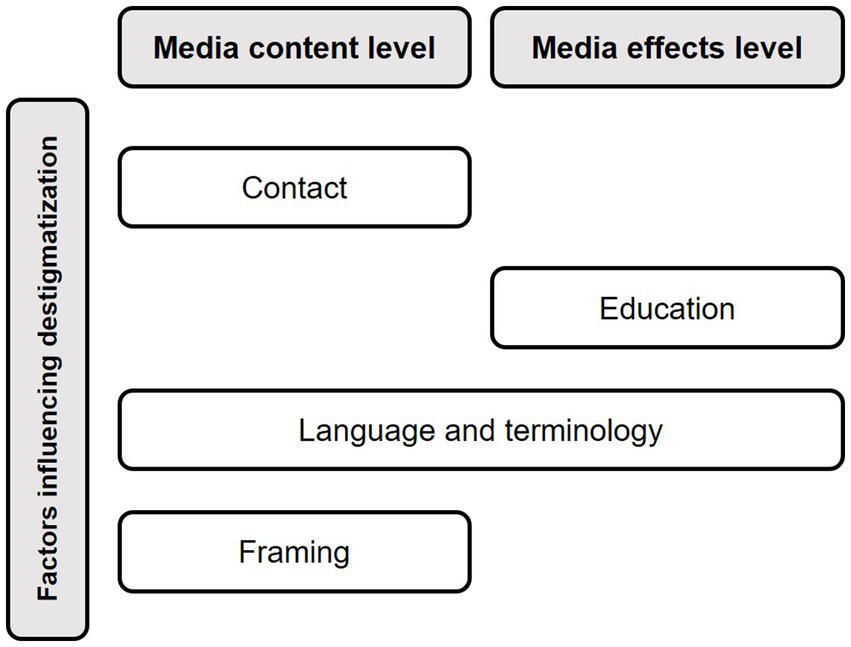

The four factor groups are not fully distinct from one another. Furthermore, some publications argue for a combination of different factor groups for successful destigmatization (e.g., Janoušková et al., 2017). However, the aim was to present an overview and systematization of factors influencing destigmatization. The interaction of these factors is complex and differs according to the stigmatized group and the further context. It can be concluded that on the media content level, framing and contact interventions in particular could be adapted. The factor group education summarizes media effects. Language and terminology are seen on both media content and media effects levels (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Overview of identified factor groups influencing destigmatization in the context of media and communication.

The present systematization of factor groups has similarities with other overviews of destigmatization interventions. Haghighat (2001), who is also part of this SLR’s final sample, formulates six possible interventions for destigmatization: educational interventions (cognitive level), psychological interventions (affective level), legislative interventions (discrimination level), political interventions (economic level), linguistic interventions (denial level), and intellectual and cultural interventions (evolutionary origin). Here, parallels with the factor groups contact, education, and language and terminology can be observed. Therefore, the factor group contact is comparable with the psychological interventions that Haghighat (2001) describes. The factor group language and terminology matches with Haghighat’s (2001) linguistic interventions. Haghighat (2001) adds that linguistic interventions not only reduce verbal disrespect but, as they are requested by stigmatized persons, they can demonstrate that existing societal orders are not immutable. The factor groups contact and education are also in line with strategies presented by Corrigan and Penn (1999). They additionally identify protest as a destigmatization strategy. Protest is connected to the suppression of stigmatization and is therefore described as less effective in promoting positive, destigmatizing attitudes (Rüsch et al., 2005). Furthermore, Lavack (2007) argues that destigmatization works at the cognitive level (see education), the affective level (see contact), the linguistic level (see language and terminology), and the discrimination level (e.g., legislation and public policy). Again, this could be considered a confirmation of the present SLR’s systematization.

The four identified factor groups influencing destigmatization in the context of media and communication are reinforced by similarities to existing systematizations. Nevertheless, this overview of factors influencing destigmatization can be seen as a starting point for further research, as nonexhaustive, and as an invitation for integration and expansion.

Destigmatization is described as a process (e.g., Yoo et al., 2012). Therefore, the third research question addresses theoretical models concerning the processual character of destigmatization. Very few publications from the SLR’s final sample develop or explore theoretical models. Of course, theories that capture the impact of various factors that influence destigmatization are discussed, as outlined in the previous section (e.g., the empathy attitude model). However, comprehensive models concerning the processual character of destigmatization are rarely encountered.

Only the Dual-Process Model of Reactions to Perceived Stigma developed by Pryor et al. (2004) is mentioned by two publications from this SLR’s final sample (Lavack, 2007; Milfeld et al., 2021). Similarly to other dual-process models, this theoretical framework posits that stigmatization arises from distinct psychological processes. Pryor et al. (2004) outline two systems—the reflexive process and the rule-based process. The reflexive process is characterized by spontaneous, instinctive, impulsive, immediate, and often emotional reactions. In contrast, the rule-based process describes reflective, thoughtful reactions based on conscious deliberation. Pryor et al. (2004) propose a temporal pattern for these reactions, insofar as rule-based reactions do not replace reflexive reactions, but the two processes dynamically interact over time.

In line with Reeder and Pryor (2008), the present review assumes that both reflexive and rule-based processes must be taken into account for effective destigmatization. It is believed that influencing a stigmatizing reflexive reaction is a difficult and long-term process. Reflexive reactions are based on learned heuristics (Pryor et al., 2004)—for example, shaped by years of exposure to stigmatizing media content. While undoubtedly desirable, influencing reflexive reactions is challenging. Instead, a rule-based reaction follows a reflexive reaction, as individuals question the appropriateness of their reflexive reaction (Pryor et al., 2004). This implies that rule-based reactions can be adjusted reactions—as long as a person is provided with sufficient time, motivation, and cognitive resources (Strack and Deutsch, 2004). This paper suggests that destigmatization starts with influencing rule-based processes. In doing so, over an extended period, this may also impact reflexive processes.

Therefore, this SLR proposes applying the Dual-Process Model of Reactions to Perceived Stigma (Pryor et al., 2004) as a framework for destigmatization efforts, with a specific emphasis on rule-based processes. Further research is needed regarding various rule-based reactions that could follow an immediate stigmatizing reflexive reaction toward a member of a stigmatized group. Individuals may become aware of their stigmatizing reactions and actively reject them. They may experience feelings like shame or guilt for their instinctive reactions, leading to a suppression of stigmatizing reactions. Or they may seek justifications for the correctness of their initial stigmatizing reactions (Pryor et al., 2004), thus reinforcing stigmatization.

Additionally, it has to be investigated which factors influencing destigmatization operate on reflexive processes and which factors impact rule-based processes. Reeder and Pryor (2008) argue that depending on the respective process, different destigmatization strategies are needed. Based on the systematization of Corrigan and Penn (1999), they assume that protest and education are connected to rule-based processes, whereas contact can impact both rule-based and reflexive processes. Like Reeder and Pryor (2008), this paper sees education—one of the four factor groups influencing destigmatization that this SLR identified—as working on rule-based processes while transferring knowledge. Contact, which can have an impact on both an affective and cognitive level, could work on both processes. Framing as well as language and terminology may predominantly impact reflexive processes. As already mentioned, empirical research on this is required.

The aim of this research was to present a general definition of destigmatization, a comprehensive overview of factors that influence it, and a theoretical reflection on its processual character. Consequently, it was decided not to focus on any specific stigmatized group (e.g., people with schizophrenia) and thereby close a research gap with this holistic approach. This SLR’s findings are classified as a summary of the current state of research, as a starting point and framework for future research. Nevertheless, it still has to be stressed that each stigmatized group has a specific history, context, and characteristics. This emphasizes the importance of a thorough reflection on individual backgrounds while conducting destigmatization research. Therefore, future researchers are invited to expand these findings according to specific stigmatized groups. Another important point of discussion here is intersectionality. An individual can experience stigmatization because of different group memberships at the same time. Research found that destigmatization interventions can even be more effective when intersectionality is considered (Martin et al., 2022). Also, sociocultural differences regarding stigmatization and destigmatization have to be taken into account (Fan et al., 2021).

Also, the importance of including stigmatized individuals in the creation of destigmatization interventions has to be discussed. Hearing the perspectives and needs of the stigmatized group should be one of the first steps within a destigmatization process. It can be observed that very few publications of the final sample acted upon this recommendation. Future research on destigmatization is invited to incorporate the perspective of stigmatized groups more extensively. At the same time, it has to be borne in mind that the work on a destigmatization project could be a “personal odyssey” (Kaufman and Kaufman, 2013, p. 215) for stigmatized individuals, especially when face-to-face contact is required. That is one reason why the present review focused on destigmatization in the context of media and communication, as contact interventions through media are a reasonable alternative for destigmatization because stigmatized individuals do not have to be present in a direct way. The factor group contact identified here summarizes different approaches to establishing such mediated contact interventions.

Destigmatization is a complex process. That also means that it cannot usually be reached through one intervention alone (Haghighat, 2001; Meese et al., 2020). Destigmatization has to be employed through continuous, open-ended projects (Haghighat, 2001). Link and Phelan (2001) emphasize that destigmatization approaches have to be multifaceted and multilevel. Therefore, this review recommends focusing not just on one factor (group) influencing destigmatization but on a combination of factors when preparing destigmatization interventions.

The findings of this research are based on a systematic literature review. Therefore, some limitations of the methodological approach have to be considered. First, the search string (destigma*) aimed for publications that explicitly refer to the term “destigmatization.” Accordingly, based on the Web of Science and CMMC database search it was not possible to include publications that could be relevant to the research objectives but use another wording (e.g., reduction of stigmatization, countering stigmatization, de-stigmatization). However, Google Scholar automatically searches for synonyms of the search string, meaning that publications with variations in terminology could have been included through this search approach. Additionally, with the extended sample, the present literature review tried to incorporate publications using another terminology. Nevertheless, the extended sample was not derived systematically. Therefore, future SLRs could employ a search string for a systematic database search including a wide range of terminology related to destigmatization to replicate and complement the findings of this SLR. Second, only publications written in English were included. Potentially relevant publications in other languages were not included. Furthermore, for the final sample, the focus was only on peer-reviewed journal articles and book chapters, excluding proceedings papers and other publication types like grey literature. Again, those publications could hold relevant information regarding destigmatization. Third, this SLR aimed for a comprehensive overview of destigmatization, resulting in a heterogeneity of theoretical and methodological approaches in the final sample. This restricted comparability and the analysis of the efficacy of factors influencing destigmatization. Fourth, most of the sampling procedure and the analysis were conducted by only one coder, the corresponding author. Thus, potential biases (e.g., learning effects) have to be considered. Nevertheless, through the intercoder reliability tests of the ABS procedure, the nondisclosure of authors’ names during the sampling, and the overall standardized SLR procedure, the aim was to reduce potential biases as much as possible.

This paper presents a systematic literature review on destigmatization in the context of media and communication. The final sample of 79 publications was systematically derived from three sources (Web of Science, Communication & Mass Media Complete, and Google Scholar) and selected using a standardized coding procedure based on an abstract-based screening and full-text reading of the publications. The findings contribute to the research field of destigmatization in three ways. First, a definition of destigmatization was derived. This closes a research gap, as a systematically derived, interdisciplinary applicable definition is—to the best of the author’s knowledge—missing to date. The proposed definition focuses on the communication-based, processual, structurally embedded, and context-specific character of destigmatization and the aim of creating change for stigmatized groups. Therefore, the importance of considering the perspectives of the stigmatized groups, which is currently rarely done in destigmatization research, is emphasized. Second, this paper presented an overview of factors influencing destigmatization, categorized into four factor groups: contact, education, language and terminology, and framing. In the context of media and communication, contact focuses on video interventions and social media, as well as the activation of empathy, reflective thoughts, and narrative engagement. For education strategies, cooperation between experts regarding the stigmatized group and media practitioners is required. The factor group language and terminology argues for a reconsideration of established language choices. Framing emphasizes the importance of different information presentation approaches via media. This overview of factors influencing destigmatization shows similarities with other systematizations (Corrigan and Penn, 1999; Haghighat, 2001) but is specified in media and communication strategies and synthesizes the current state of the research. Third, the processual character of destigmatization was discussed. Referring to the Dual-Process Model of Reactions to Perceived Stigma (Pryor et al., 2004), it is assumed that destigmatization should start with rule-based processes and, over an extended period, may impact reflexive processes. Overall, these findings demonstrate that research on destigmatization is diverse regarding methodological approaches, stigmatized groups of interest, and relevant scientific disciplines. Yet, it can be concluded that health communication is particularly prominent in, and important for, destigmatization research.

By unifying diverse and interdisciplinary approaches to destigmatization, these findings are considered a starting point for future research and invite scholars to critically examine, expand, and refine the definition, factor groups, and theoretical contribution presented here. Future research should assess the applicability of the findings for different stigmatized groups and settings. Also, we still have to uncover further factors influencing destigmatization (Tamul and Hotter, 2019; Hecht et al., 2022). As regards the processual character of destigmatization, we need more empirical research to test those theoretical assumptions. Here, for example, the range of rule-based reactions that follow an immediate stigmatizing reflexive reaction toward a member of a stigmatized group should be explored. Additionally, it should be investigated which factors influencing destigmatization operate on reflexive processes, and which ones impact rule-based processes.

Moreover, with the overview of factors that influence destigmatization, this SLR aims to reach media practitioners seeking advice on how to create destigmatizing interventions. Both research and practical work on destigmatization contribute to fostering equality and fair opportunities for all individuals. Future research on destigmatization still has to make a lot of progress (Heney, 2022). By adopting a future-oriented perspective that focuses on destigmatization rather than stigmatization, the present study hopes to contribute to filling this research gap.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, the review protocol of this SLR is publicly available via OSF: https://bit.ly/3xsuZ1e. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

DK: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author declares financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The article processing charges were funded by the joint publication funds of the TU Dresden, including Carl Gustav Carus Faculty of Medicine, and the SLUB Dresden as well as the Open Access Publication Funding of the DFG. No further funding was received for conducting the research presented in this article.

The author wants to thank the reviewers and the academic editor for their valuable and constructive comments.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abdulai, A.-F., Howard, A. F., Yong, P. J., Noga, H., Parmar, G., and Currie, L. M. (2022). Developing an educational website for women with endometriosis-associated dyspareunia: usability and stigma analysis. JMIR Hum. Factors 9:e31317. doi: 10.2196/31317

Bartsch, A., and Kloß, A. (2019). Personalized charity advertising: can personalized prosocial messages promote empathy, attitude change, and helping intentions toward stigmatized social groups? Int. J. Advert. 38, 345–363. doi: 10.1080/02650487.2018.1482098

Bartsch, A., Oliver, M. B., Nitsch, C., and Scherr, S. (2018). Inspired by the Paralympics: effects of empathy on audience interest in Para-sports and on the destigmatization of persons with disabilities. Commun. Res. 45, 525–553. doi: 10.1177/0093650215626984

Bartsch, A., and Schneider, F. M. (2014). Entertainment and politics revisited: how non-escapist forms of entertainment can stimulate political interest and information seeking. J. Commun. 64, 369–396. doi: 10.1111/jcom.12095

Batson, C. D., Chang, J., Orr, R., and Rowland, J. (2002). Empathy, attitudes, and action: can feeling for a member of a stigmatized group motivate one to help the group? Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 28, 1656–1666. doi: 10.1177/014616702237647

Batson, C. D., Polycarpou, M. P., Harmon-Jones, E., Imhoff, H. J., Mitchener, E. C., Bednar, L. L., et al. (1997). Empathy and attitudes: can feeling for a member of a stigmatized group improve feelings toward the group? J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 72, 105–118. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.72.1.105

Baumann, E., Horsfield, P., Freytag, A., and Schomerus, G. (2022). “The role of media reporting for substance use stigma” in The stigma of substance use disorders. eds. G. Schomerus and P. W. Corrigan (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 213–231.

Beaulieu, M., St-Martin, K., and Cadieux Genesse, J. (2021). ‘I care a lot’ a commentary on the depiction of elder abuse in the film. J. Elder Abuse Negl. 33, 342–349. doi: 10.1080/08946566.2021.1965931

Brown, S. (2020). The effectiveness of two potential mass media interventions on stigma: video-recorded social contact and audio/visual simulations. Community Ment. Health J. 56, 471–477. doi: 10.1007/s10597-019-00503-8

Brownstone, L. M., Kelly, D. A., Ko, S.-J., Jasper, M. L., Sumlin, L. J., Hall, J., et al. (2021). Dismantling weight stigma: a group intervention in a partial hospitalization and intensive outpatient eating disorder treatment program. Psychotherapy 58, 282–287. doi: 10.1037/pst0000358

Bullinger, B., Schneider, A., and Gond, J.-P. (2023). Destigmatization through visualization: striving to redefine refugee workers’ worth. Organ. Stud. 44, 739–763. doi: 10.1177/01708406221116597

Chiu, Y.-H., Kao, M.-Y., Goh, K. K., Lu, C.-Y., and Lu, M.-L. (2021). Effects of renaming schizophrenia on destigmatization among medical students in one Taiwan university. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18:9347. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18179347

Chung, A. H., and Slater, M. D. (2013). Reducing stigma and out-group distinctions through perspective-taking in narratives. J. Commun. 63, 894–911. doi: 10.1111/jcom.12050