- School of Foreign Studies, Nantong University, Nantong, China

This study examines the image construction of front-line healthcare workers (HCWs) in Chinese government Weibo (microblogs) during the COVID-19 pandemic. Specifically, we rely on a discourse-historical approach to analyze 1,510 posts collected from an influential government Weibo account, @healthchina (健康中国), during the first wave of the pandemic to investigate the diverse images of HCWs constructed, the discursive strategies employed, and the pragma-linguistic devices used by @healthchina. The data analyses find that Chinese HCWs are depicted as professional and competent in addressing the pandemic crisis, compassionate and caring to their patients, and responsible and devoted to public health. Two discursive strategies are found salient in HCW’s image construction—nomination and predication realized through the identity labels, attitude/judgment resources, metaphors and comparisons, pictures, and hashtags. We argue that Chinese government microbloggers intentionally constructed these images of the HCWs to elicit positive emotional responses, reinforce government trustworthiness, and foster social cohesion in the collective fight against the pandemic. This research underscores the strategic communication efforts aimed at shaping the perception of HCWs and their pivotal role in managing the pandemic.

1 Introduction

The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic sparked extensive discourse highlighting the remarkable contributions of healthcare workers (referred to as “HCWs” hereafter) in their unwavering efforts to combat the virus (e.g., Adam and Walls, 2020). This discourse has gained substantial traction across various social media platforms in China, facilitating the spreading of news and stories about Chinese medical staff. Notably, Chinese government Weibo (microblogging) played a pivotal role in constructing and communicating the images of HCWs amid the crisis. While some studies have investigated the government’s discursive practices in public crises (e.g., Wang, 2016), there exists a substantial knowledge gap regarding the discursive construction of the image of a specific group within the Chinese government microblogging sphere.

Our study addresses this research gap by conducting a discourse-historical analysis of HCWs’ image construction in the Chinese government Weibo posts. Examining 1,510 posts from the highly influential government Weibo account, @healthchina (@健康中国), we have three research objectives: (i) to gain a comprehensive understanding of the HCWs’ images constructed in Chinese government Weibo posts, (ii) to explore the discursive strategies and pragma-linguistic devices employed in the process, and (iii) to examine the motivations driving these discursive constructions within the context of the COVID-19 crisis.

2 Political discourses of COVID-19

The global spread of the COVID-19 pandemic has propelled it into a central theme across various mediums, including government documents, official briefings, political leaders’ speeches, and government Weibo posts. Consequently, a substantial body of research has been conducted to examine political discourses surrounding the pandemic from different perspectives (e.g., Chepurnaya, 2021; Jarvis, 2022; Wang and Yao, 2022; Williams and Wright, 2022). Some of these studies focus on the use and functions of specific linguistic tools, including personal pronouns (Williams and Wright, 2022), numerical figures (Billig, 2021), and metaphors (Seixas, 2021), yielding valuable research insights. For instance, Williams and Wright (2022) explored UK government speakers’ use of person pronouns in the daily televised COVID-19 briefings. Their research suggests that the strategic selection of “inclusive,” “exclusive,” or “ambiguous” person pronouns mitigates the government’s accountability for controlling the spread of the pandemic while increasing the sense of responsibility placed on the general public. Billig (2021) turned his attention to the numerical figures, examining their role in framing the British government’s COVID-19 goals and their political achievements. Seixas (2021) examined the militaristic metaphors used by Donald Trump in his tweets, proposing that these metaphors aid Trump in pursuing the goal of constructing enemies and shifting the blame and responsibility.

Besides these micro-linguistic analyses, there are also studies investigating the strategic aspect of discourse, i.e., the discursive strategies employed by the political discourse participants. Typical studies include Chepurnaya (2021) and Takovski (2021). The former cast interest in the strategic perspective of the political discourse about the pandemic, applying Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) concepts and Crisis Communication analytical tools to examine the discursive strategies used in Trump’s tweets about the pandemic. The latter examined two major political parties’ strategic use of the pandemic, focusing specifically on the strategies of predication and argumentation employed for achieving political purposes.

Finally, a growing body of research has been dedicated to unraveling the discursive construction in the political discourses surrounding COVID-19. For instance, Andreouli and Brice (2020) analyzed how the UK government constructed various aspects of citizenship in their briefings during the initial 9 months of the pandemic, resulting in five interconnected constructions of “good citizens” actively combating the pandemic, including the confined, the heroic, the sacrificial, the unfree, and the responsible. Berrocal et al. (2021) analyzed the statements made by 29 prominent political leaders across five continents, assessing discursive constructions of solidarity and nationalism with a focus on the social representation of inclusion/exclusion involving various groups.

These studies above provide valuable insights and suggestions for the present study. However, despite the wealth of research on the political discourses of COVID-19, there remains a significant research gap concerning a specific sub-genre of this discourse— Chinese government Weibo posts, except for the work conducted by Wang and Yao (2022) exploring how a specific Chinese government Weibo account, @chinapeace, constructed trustworthiness in their posts during the initial wave of the pandemic. Nonetheless, the portrayal of medical staff in Chinese government Weibo posts and the underlying motivations driving their image construction remains relatively under-explored. Addressing this research gap promises to provide valuable insights into the unique dynamics of political discourse on social media during public crises. As such, the research purposes of this study are (i) to analyze the images of Chinese HCWs constructed in @chinapeace, and (ii) to explore the discursive strategies used in this process.

3 Image construction in crisis communication

The scholarly understanding of image has shifted from essentialism to constructivism, marked by a “discursive turn” in image construction research (Chen and Jin, 2022). From a constructivist perspective, an image is neither preexisting nor static; it can be dynamically constructed, managed, or even repaired through discourse. Studies in pragmatics and discourse analysis have delved into how discursive strategies shape the images of individuals, groups, companies, cities, or countries (e.g., Alonso Belmonte et al., 2010). These investigations have explored how image construction can effectively contribute to fulfilling interpersonal or transactional goals.

In times of crisis, the construction of images is crucial in shaping public perception, influencing behavior, and managing narratives associated with the event or situation. Thus, image construction has attracted significant scholarly attention, leading researchers to explore the construction of diverse images of social actors, events, and activities in public discourses surrounding crises (e.g., Valdebenito, 2013; Wang, 2016; Wang and Liu, 2019; Sun and Chałupnik, 2022; Wang and Yao, 2022). For instance, Valdebenito (2013) examined how 12 Chilean companies constructed a positive corporate image in public statements addressing a corporate crisis. Their study identified three crucial discursive strategies: image-repair strategies, ethos construction, and narrative techniques. The study also highlighted the instrumental roles of different linguistic features (e.g., metaphor) and pragmatic strategies (e.g., redundancy) in constructing corporate image. Wang and Liu (2019) also focused on corporate image construction within critical contexts. By analyzing corporate chief executive officer (CEO) letters, these scholars investigated how CEOs struggle to restore a trustworthy image by neutralizing the positive, emphasizing the negative, and mobilizing public emotions. Besides corporate image construction, studies have explored government image construction in crisis communication. For example, Wang (2016) investigated how Chinese local governments struggled to build a trustworthy image in press conferences addressing the Tianjin blasts in China. She found that the local government in Tianjin City constructed its trustworthiness mainly by activating its ability, integrity, and benevolence in its press conference discourse. More recently, Wang and Yao (2022) examined government image construction in a newly emerging social media discourse, precisely that of government-based Weibo accounts, finding that some specific linguistic devices (e.g., appraisal and metaphor) and semiotic technologies (e.g., hashtags) play an instrumental role in government image construction. These studies form a solid literature foundation for our research; however, research on HCWs’ image construction in Chinese government Weibo posts and the discursive strategies employed for this purpose is lacking.

4 Methodology

4.1 Research questions

This study focuses on the discursive construction of front-line medical staff in China’s government Weibo posts during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. Our investigation is driven by two research questions:

1. What images of HCWs are constructed in Chinese government Weibo posts?

2. What discursive strategies are employed in constructing these images, and what specific pragma-linguistic devices are used in this process?

4.2 Data collection and analysis

Data for this study were collected from the official Weibo account of the National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China, known as @healthchina.1 This account has extensive reach, generating billions of views and consistently ranking first on the government affairs list, making it one of China’s most influential government Weibo accounts. Throughout the fight against COVID-19, @healthchina played a pivotal role in narrating the experiences of medical staff and disseminating accurate and timely information about COVID-19 prevention, symptoms, testing, and treatment to the public. By actively sharing content related to Chinese HCWs, @healthchina portrayed multidimensional images of HCWs, aiming to foster hope and instill confidence among the public.

To collect the data, the second researcher logged onto the Sina Weibo (新浪微博) platform and followed the official account @healthchina. The data-collection process involved utilizing the advanced web search interface on the platform, whereby the researcher retrieved posts from @healthchina containing the keywords “疫情” (pandemic) and “新冠” (coronavirus) in Chinese. The data-collection period was deliberately set from January 1 to March 31, 2020, corresponding to the rapid development of COVID-19 from Wuhan to other cities in China. Throughout this period, doctors and nurses from various areas in China volunteered in pandemic prevention and control efforts. The official government Weibo platform, like @healthchina, featured the highest prevalence of news and narratives spotlighting these front-line healthcare staff in this period, facilitating the collection of research data for the present study. Figure 1 visually represents the advanced web search interface used in the study.

The data of this study consisted of 1,510 posts, encompassing interactions between @healthchina and its followers, amounting to 634,057 words. This dataset included both original posts authored by @healthchina and reposts by other users. Including reposts in our analysis holds particular significance since reposting has been acknowledged as a crucial microblogging activity through which social media users express their opinions and attitudes (Yan and Huang, 2014).

In the process of data analysis, we relied on the discourse-historical approach (DHA), which includes three analytical dimensions: (i) identifying the content of a particular discourse, (ii) investigating discursive strategies, and (iii) examining linguistic devices and the specific context-dependent linguistic realizations (Reisigl and Wodak, 2016). Following the DHA framework, our data analysis was conducted in three phases. Firstly, we scrutinized the content of the posts, categorizing the diverse images of HCWs constructed by @healthchina. Secondly, we examined the discursive strategies used for HCWs’ image construction, focusing on nomination and predication, as these strategies emerged as particularly salient in our dataset. Thirdly, our attention turned to the lexical, rhetorical, and pragmatic devices, as well as semiotic resources such as hashtags, utilized to realize the above-mentioned discursive strategies. Additionally, the two researchers thoroughly reviewed relevant studies and engaged in discussions to unveil potential motivations underlying the image construction of healthcare workers by @healthchina.

5 Findings

5.1 Images of HCWs constructed by @healthchina

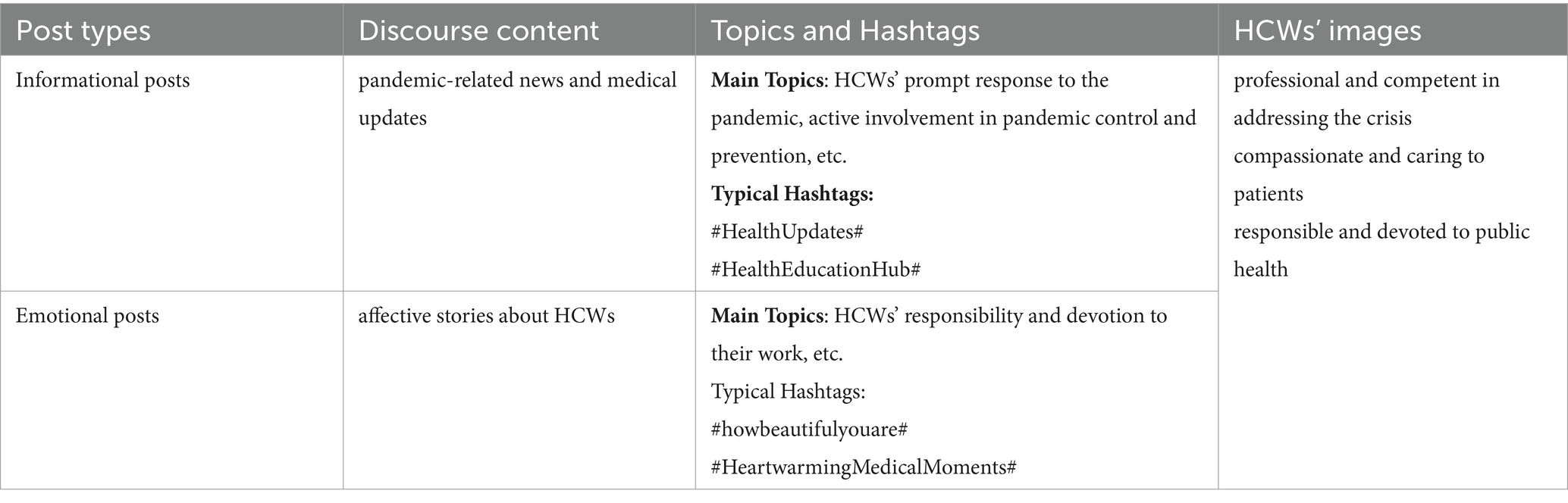

We conducted the content analysis of the Weibo posts, identifying two primary categories—informational and emotional posts. These categories align with the two principal communicative functions typically observed in government Weibo posts, i.e., informing the public and mobilizing public emotions (Wang and Yao, 2022). The content of informational posts primarily revolves around pandemic-related news and medical updates for the public. In contrast, emotional posts primarily features affective stories highlighting dedicated HCWs fulfilling their responsibilities or sharing heartwarming interactions between HCWs and their patients.

Regarding the specific topics, the informational type comprises posts featuring hashtags such as #健康发布# (#HealthUpdates#) and #健康科普汇# (#HealthEducationHub#). Topics related to HCWs include their prompt response to the pandemic, active involvement in pandemic control and prevention, contributions to medical research on the pandemic, etc. The selection of these topics depicts HCWs as highly professional, competent, and authoritative individuals capable of combating the pandemic and safeguarding people’s lives. A typical example is illustrated below:

1 #健康发布# [国家卫生健康委积极开展新型冠状病毒感染的肺炎疫情防控工作  ]2020年1月1日我委成立由马晓伟主任为组长的疫情应对处置领导小组, 会商分析疫情发展变化, 研究部署防控策略措施, 及时指导, 支持湖北省和武汉市开展病例救治, 疫情防控和应急处置等工作 (#HealthUpdates# [National Health Commission Actively Carries Out Prevention and Control Work for the coronavirus epidemic] On January 1, 2020, the National Health Commission established an epidemic response and management leadership group, with Director Ma Xiaowei as the leader. They analyzed the epidemic situation, studied and deployed prevention and control strategies, and provided timely guidance and support for Hubei Province and Wuhan City in treating cases, epidemic prevention and control, and emergency response, among other tasks.)

]2020年1月1日我委成立由马晓伟主任为组长的疫情应对处置领导小组, 会商分析疫情发展变化, 研究部署防控策略措施, 及时指导, 支持湖北省和武汉市开展病例救治, 疫情防控和应急处置等工作 (#HealthUpdates# [National Health Commission Actively Carries Out Prevention and Control Work for the coronavirus epidemic] On January 1, 2020, the National Health Commission established an epidemic response and management leadership group, with Director Ma Xiaowei as the leader. They analyzed the epidemic situation, studied and deployed prevention and control strategies, and provided timely guidance and support for Hubei Province and Wuhan City in treating cases, epidemic prevention and control, and emergency response, among other tasks.)

Example (1), published by @healthchina on January 19, 2020, portrays the National Health Commission and the medical team led by Director Ma as highly professional and competent in the battle against the epidemic. The post is accompanied by the hashtag #HealthUpdates#, categorizing the topic and emphasizing the discourse content (Zappavigna, 2018). Within the post, the National Health Commission established an “epidemic response and management leadership group” led by Director Ma Xiaowei. This immediate action conveys a sense of authority and leadership within the healthcare sector. Director Ma Xiaowei emerges as a prominent figure, implying that exceptionally qualified individuals spearhead the response to the COVID-19 crisis.

Moreover, the leadership group is depicted engaging in activities such as “analyzing the epidemic situation,” “studying and deploying prevention and control strategies,” and “providing timely guidance and support.” This multifaceted approach suggests that HCWs are well aware of the situation and take well-informed actions to address it effectively. This portrayal reinforces their competence in handling complex and high-pressure situations. The careful selection of these subtopics in Example (1) conveys to the public that the National Health Commission and the medical team possess the necessary skills and expertise in their specific domains to effectively manage the COVID-19 crisis, thereby constructing a professional and competent image.

The second type comprises narrative posts often introduced with hashtags like #你有多美# (#howbeautifulyouare#) and #温暖医瞬间# (#HeartwarmingMedicalMoments#). These posts feature pictures or videos related to HCWs and encompass topics highlighting their positive qualities, such as their responsibility and devotion to their work. These narratives also underscore their care and compassion for patients. The hashtags in these posts serve the conceptual function of categorizing content and play an interpersonal role in expressing attitudes and stances (Halliday, 1985; Zappavigna, 2016). The following two examples illustrate how Chinese HCWs are depicted as hardworking and devoted in their health work and caring and compassionate toward their patients, respectively.

2 #你有多美# #温暖医瞬间# 看这张照片, 你就知道海南医疗队在武汉有多拼! (#howbeautifulyouare# #HeartwarmingMedicalMoments# Look at this picture, and you will see how hardworking the Hainan medical team is in Wuhan!).

3 #你有多美# #温暖医瞬间# [不是父子, 胜似父子]从1月28日开始在湖北黄冈大别山区域医疗中心, 接受治疗的患者陈友明, 最近特意让护士录制了一段小视频他要感谢山东医疗队照顾他的三位护士, 也可以说是他心目中的三个“儿子”2 (#howbeautiful you are# #HeartwarmingMedicalMoments# [Not Father and Son, but Like Father and Son] Chen Youming, a patient receiving treatment at the Hubei Huanggang Dabie Mountain Medical Center since January 28th, has recently had a short video recorded. He wishes to express his gratitude to three nurses from the Shandong medical team who have been taking care of him. In his heart, they are like his three “sons.” Watch the video)(see text footnote 2).

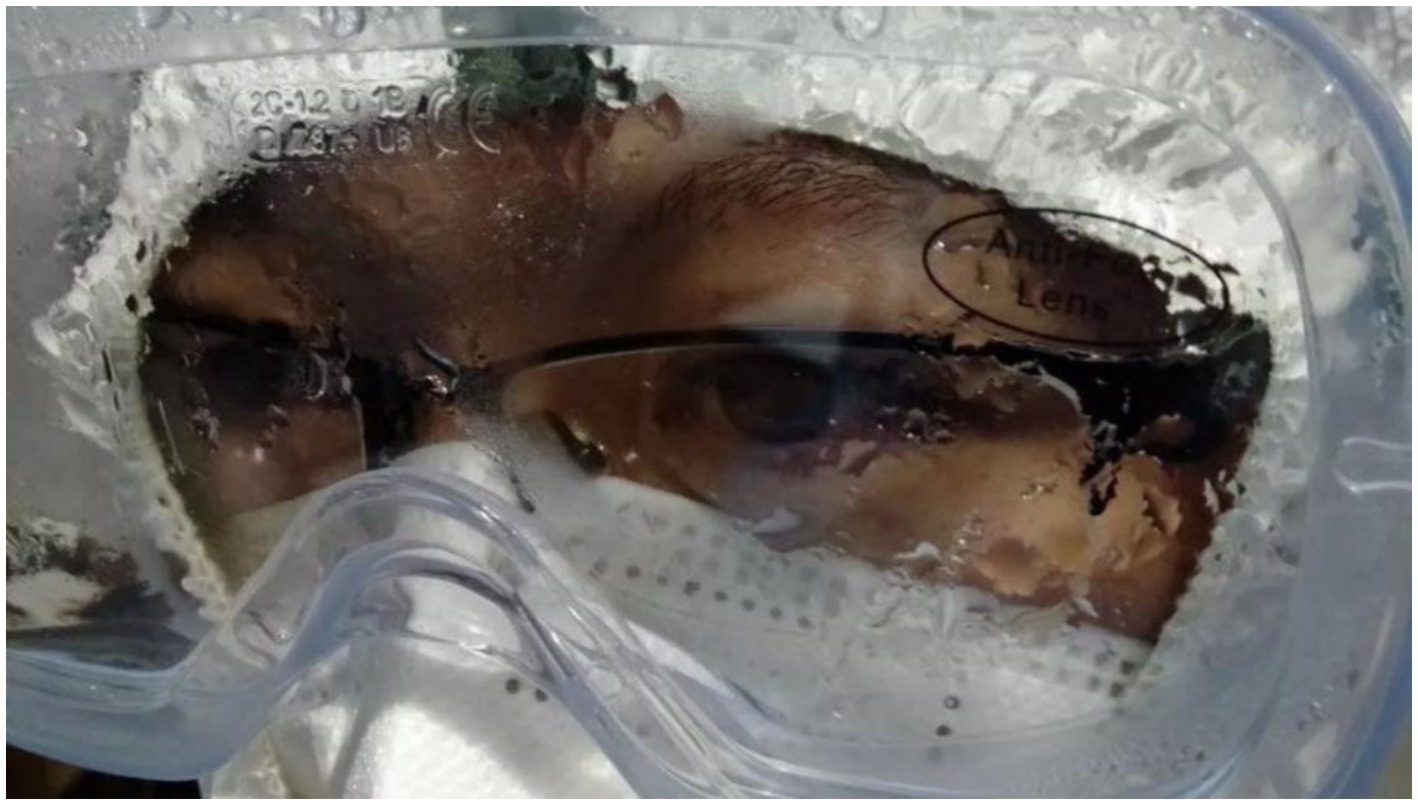

Both examples are introduced with two emotional hashtags, #你有多美# (#howbeautifulyouare#) and #温暖医瞬间# (#HeartwarmingMedicalMoments#), signifying @healthchina’s positive evaluation of HCWs. Specifically, in Example (2), the HCWs in Hainan medical team are depicted to be hardworking and dedicated in their work, shown from the sweat under the face mask of a doctor in a close-up picture accompanied in the post (Figure 2). In Example (3), the HCWs are lauded for their caring and compassionate approach to patients. In this narrative, three nurses receive high praise from a specific patient, Chen Youming, who recorded a short video to express his gratitude for their care. Chen perceives these three nurses as his three “sons,” suggesting they care for him as if he were their own family. Following the main content is a link to the short video, indicated by the symbol  , functioning as a multimodal evidential marker to prove the “reliability of the information” (Mushin, 2000, p. 927). Thus, the HCWs, represented by these three nurses, are depicted as caring and compassionate towards patients, treating them like beloved family members.

, functioning as a multimodal evidential marker to prove the “reliability of the information” (Mushin, 2000, p. 927). Thus, the HCWs, represented by these three nurses, are depicted as caring and compassionate towards patients, treating them like beloved family members.

To sum up, in the informational and emotional posts issued by @healthchina during the first 3 months of the year 2020, various discourse topics (i.e., HCWs’ prompt response to the pandemic, active involvement in pandemic control and prevention, responsibility and devotion to their jobs, etc.), realized through some typical hashtags, are selected to portray HCWs as professional and competent in addressing the pandemic crisis, compassionate and caring toward their patients, and responsible and devoted to public health. Table 1 presents an overall picture of HCWs’ images constructed in @healthchina’s Weibo posts.

Notable is that the HCWs’ images are made salient through the choice of discourse content and discursive strategies. Two discursive strategies are particularly prominent: nomination and predication. The following section examines how these two discursive strategies contribute to constructing HCWs’ images through a detailed textual analysis of @healthchina’s Weibo posts.

5.2 Discursive strategies employed in the depictions

5.2.1 Nomination strategy

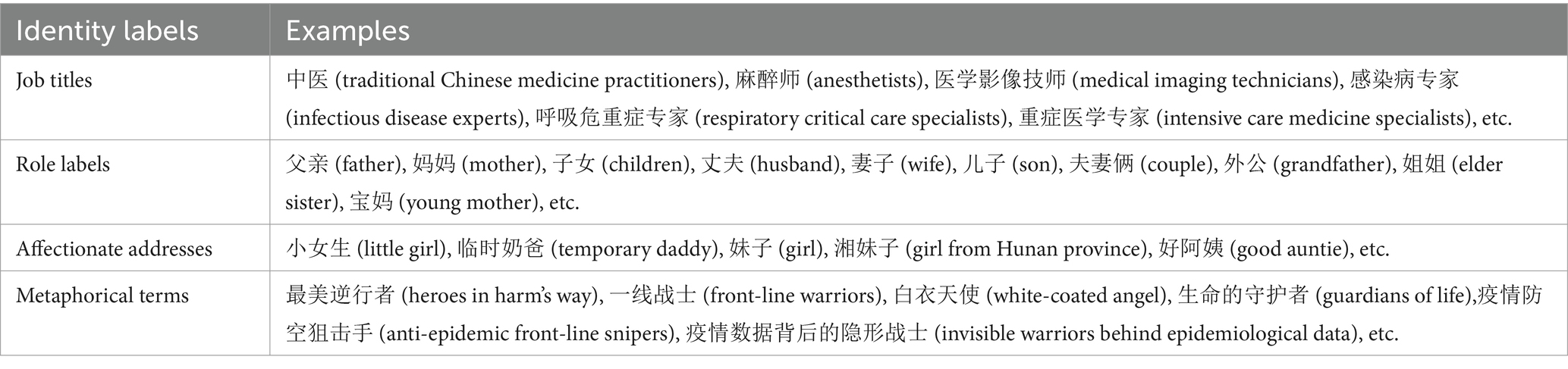

Nomination involves naming and categorizing social actors through membership categorization or rhetorical devices like metaphor, metonymy, and synecdoche (Wodak, 2001). Our study focuses on how HCWs were named or referred to linguistically in @healthchina’s posts. This strategy entails the purposeful selection of literal and metaphorical identity labels, which contribute to constructing diverse images of the medical staff. The analyses of @healthchina’s posts yield a wide array of identity labels referring to the medical staff, encompassing job titles, role labels, affectionate addresses, and metaphorical titles (see Table 2).

Job titles, as artifacts or symbolic objects, convey signals about individuals’ knowledge, skills, and competence in specific domains (Rafaeli and Pratt, 2013). In @healthchina’s posts, titles such as “感染病专家” (“infectious disease experts”) and “呼吸危重症专家” (“respiratory critical care specialists”) were frequently employed to highlight the higher “epistemic status” (Heritage, 2012) of the HCWs, positioning them as highly skilled and capable professionals who were well-equipped to tackle the challenges posed by the pandemic. Moreover, as job titles inherently reflect expanded roles and responsibilities (Manning et al., 2012), these titles also imply a level of authority and responsibility held by Chinese HCWs in their respective roles, reinforcing their expert image within the healthcare domain.

Role labels such as “父亲” (“father”), “妈妈” (“mother”), “子女” (“children”), “丈夫” (“husband”), and “妻子” (“wife”) were primarily used to depict HCWs as ordinary individuals in the domestic sphere (Sun and Chałupnik, 2022). In referring to HCWs using these role labels, @healthchina created an emotional connection between HCWs and the public and invoked societal expectations for them. Further, these role labels added another layer to the depiction of medical workers, highlighting the intersection of their professional responsibilities with their roles within their families. This portrayal reinforced the perception of HCWs as ordinary individuals who were forced to juggle multiple responsibilities while exhibiting selflessness and dedication, emphasizing their nobility in terms of sacrificing their time with their own families for the good of the entire country, as Wang and Ge (2022) discovered in their study.

Affectionate addresses such as “小女生” (“little girl”), “临时奶爸” (“temporary daddy”), and “好阿姨” (“good auntie”) were employed to depict Chinese HCWs as compassionate and caring to their patients. Using these terms evokes a sense of warmth, friendliness, and kindness (Wang and Yao, 2022), creating an emotional connection between medical workers and those they cared for. For instance, the term “小女生” (“little girl”) depict a youthful and innocent image, suggesting a gentle and caring nature associated with these identities. The label “临时奶爸” (“temporary daddy”) refers to a medical worker taking on the temporary role of father, symbolizing the care and protection this individual exhibited toward patients. The term “好阿姨” (“good auntie”) portrays a figure who is nurturing and kind-hearted, emphasizing the role of medical workers in providing emotional support and comfort. All these affectionate addresses were selected to signify the role of Chinese HCWs in creating a comforting and caring environment for those in their care, portraying them as compassionate caregivers who not only provided medical expertise but also offered empathy, kindness, and a nurturing presence to those in their care.

In addition, various metaphorical terms were used to describe Chinese HCWs in the government Weibo posts, conveying specific qualities or attributes associated with their roles. For instance, “最美逆行者” (“heroes in harm’s way”) and “一线战士” (“front-line warriors”) activate a war metaphor, underscoring the heroic and courageous nature of Chinese HCWs. “白衣天使” (“white-coated angels”) and “生命的守护者” (“guardians of life”) highlight the compassionate and caring role of medical staff, positioning Chinese HCWs as empathetic caregivers who provide emotional support, comfort, and protection to those in need. “疫情防空狙击手” (“anti-epidemic front-line snipers”) and “疫情数据背后的隐形战士” (“invisible warriors behind epidemiological data”) emphasize the critical role HCWs played in pandemic prevention and control, underscoring the image of HCWs as professional and competent experts fighting against the COVID-19 pandemic by leveraging their knowledge and expertise.

Overall, all the above identity labels, literal or metaphorical, were used as linguistic realizations of the nomination strategy, portraying Chinese HCWs as brave, compassionate, and competent in the battle against the COVID-19 pandemic.

5.2.2 Strategy of predication

The predication strategy focuses on making positive or negative evaluations of social actors via explicit or implicit predicates or modifiers (Wodak, 2001). In our study, predication centers on the discursive qualification of Chinese HCWs in the pandemic context. Data analyses demonstrate that this strategy primarily involves using explicit predicative adjectives and verbs, rhetorical and pragmatic devices, and the semiotic resource of hashtags.

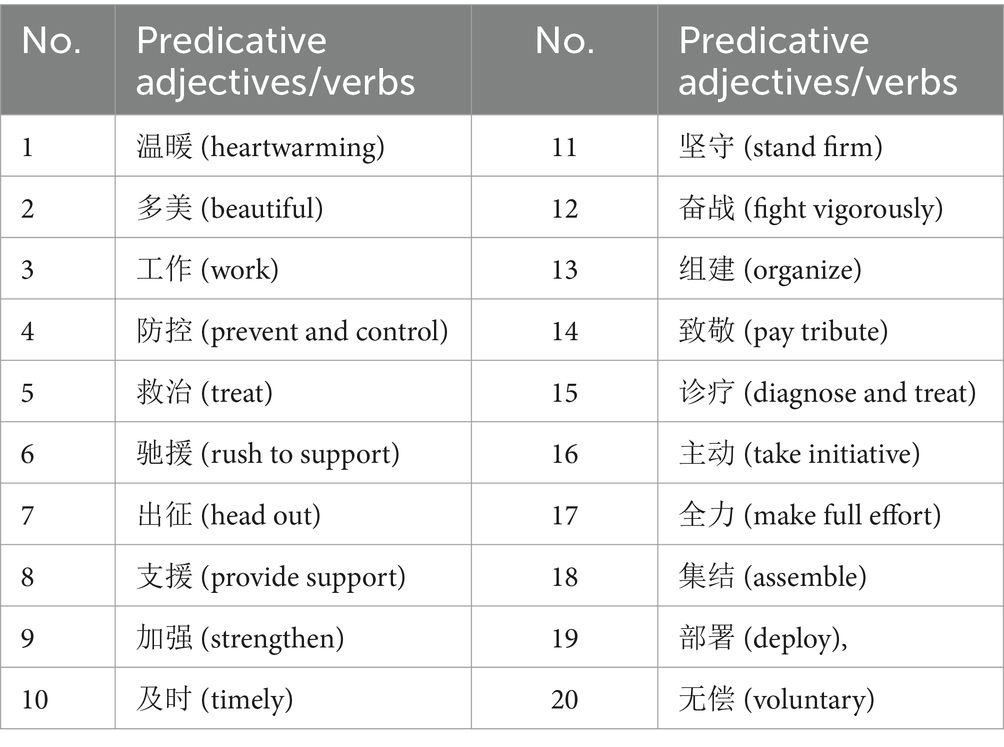

In @healthchina’s posts, predicative adjectives and verbs were used to depict the efforts of Chinese HCWs battling against the pandemic, giving rise to various related images. Through the employment of online word cloud technology,4 we identified the top 20 adjectives and verbs frequently used in the posts to describe Chinese HCWs (Table 3).

Adjectives such as “温暖” (“heartwarming”) and “多美” (“beautiful”) evoke emotions of warmth, care, and beauty, suggesting that Chinese HCWs possess an innate kindness and compassion in their interactions with patients and the community. These two adjectives appear in hashtags such as “#暖医#” (“#HeartwarmingDoctors#”), “#温暖医瞬间” (“#HeartwarmingMedicalMoments#”), and “#你有多美#” (“#HowBeautifulYouAre#”), making these hashtags a vital semiotic resource related to HCWs’ image construction (Zappavigna, 2018).

Predicative verbs also contributed to constructing the Chinese HCWs’ favorable images. Verbs such as “工作” (“work”), “防控” (“prevent and control”), and “救治” (“treat”) emphasize the diligent and skillful efforts of Chinese HCWs in managing and treating patients during the pandemic, underscoring their professionalism and competence in fulfilling their crucial roles. Verb phrases including “驰援” (“rush to support”) and “出征” (“head out”) imply a profound commitment and readiness to provide assistance, even in the most challenging situations. Verbs such as “支援” (“provide support”), “加强” (“strengthen”), and “组建” (“organize”) suggest a collaborative and supportive environment among healthcare workers, implying that healthcare professionals worked together bolstered their collective efforts, and organized themselves effectively to tackle the pandemic’s challenges as a united front. Finally, verb phrases including “坚守” (“stand firm”), “奋战” (“fight vigorously”), and “致敬” (“pay tribute”) highlight the noble qualities of perseverance and devotion exhibited by Chinese HCWs while facing the pandemic head-on, and their garnering of admiration and respect from the community they served.

Rhetorical and pragmatic devices were also used as predication strategy to depict Chinese HCWs, as exemplified below.

4 当我们阖家团圆品尝年夜饭时有这样一群人依旧在自己的岗位坚守为我们的幸福生活提供最坚实的保障… (When we gather as a family to enjoy the New Year’s Eve dinner, there is a group of people who are still steadfast in their positions, providing the strongest guarantee for our happy lives…)

In Example (1), the rhetorical device of comparison is employed to highlight the noble traits of Chinese HCWs in their fight against the COVID-19 pandemic. The phrase “阖家团圆品尝年夜饭” (“gather as a family to enjoy the New Year’s Eve dinner”) holds cultural significance, representing a cherished tradition of unity and happiness. However, the post highlights that amidst this highly valued and joyous occasion for all Chinese, there existed a group of individuals—the HCWs—who were “still steadfast in their positions.” Such a comparison serves multiple purposes. First, it establishes a clear contrast between the normalcy and joy experienced during a family gathering and the unwavering commitment of the medical staff, thus amplifying the perception of their sacrifices and solidifying their responsibility for public welfare. Furthermore, it highlights the importance of HCWs’ work by juxtaposing it with a traditional and treasured cultural event—the Chinese New Year. Through this comparison, @healthchina underscored the significance of the medical staff’s contributions and emphasized their vital responsibility in safeguarding the well-being and happiness of society.

Pragmatic presupposition is also used in this example to depict HCWs. The adverb “依旧” (“still”) functions as a presupposition trigger to imply that medical staff are always steadfast in their positions regardless of circumstance. Similarly, the phrase “提供最坚实的保障” (“providing the strongest guarantee for our happy life”) implies that HCWs are vital for public well-being. As such, by means of presupposition, the vivid image and noble traits of the HCWs are reinforced.

5 对身在抗击新型冠状病毒疫情的医务工作者来说这是一个终生难忘的春节。在这场战役中, 车票已退, 婚礼取消这样的一幕幕, 随时随刻都发生在这些坚守在一线岗位上的医护人员身上 “白衣战士们”义无反顾的选择了逆流而上, 抗击第一线!在这危急时刻, 让我们向这些挺身而出的医务工作者致敬!我们等你们凯旋! (For the medical workers engaged in combating the Covid-19 epidemic, this is an unforgettable Chinese New Year. In this battle, scenes like canceled train tickets and postponed weddings constantly occur for those healthcare personnel who stand at the front line. The “white-clad warriors” have made unwavering choices to go against the tide and fight on the front lines! In this critical moment, let us salute these brave medical workers who have stepped forward! We await your triumphant return!).

In Example (2), @healthchina uses the rhetorical device of metaphor to convey the noble traits of HCWs. Words like “抗击” (“fight against”), “战役” (“battle”), “战士” (“warriors”), and “凯旋” (“triumphant return”) activate a metaphor in which the virus is compared to an enemy in a war, while the medical staff are depicted as warriors bravely fighting against the pandemic enemy (Semino, 2021). The phrase “白衣战士” (“white-coated warriors”) employs “白衣” (“white-coated”) to refer to the uniforms worn by HCWs, symbolizing their purity and devotion in their mission to combat the virus. By likening medical staff to warriors, the metaphor conveys both the dangers posed by the pandemic and the HCWs’ bravery and willingness to confront and overcome challenges on the front lines of the battle (Flusberg et al., 2018).

Furthermore, the expression “逆流而上” (“go against the tide”) activates a metaphor of waves (Abdel-Raheem, 2021), depicting HCWs’ actions as akin to swimming against waves and thereby symbolizing their ability to confront and overcome obstacles and difficulties, and their determination and resilience. Standing up against prevailing circumstances, HCWs exemplified their unwavering commitment to their duty, fearlessly facing the challenges and working tirelessly to combat the virus.

In conclusion, @healthchina utilized the predication strategy, realized through various linguistic devices and semiotic resources, to depict Chinese HCWs as compassionate, hardworking, devoted, and brave individuals with the necessary expertise to provide exceptional care and support during the pandemic. This powerful use of the predication strategy adds depth and emotional resonance to the portrayal, evoking admiration and respect for the extraordinary noble traits of these ordinary medical workers.

6 Discussion and conclusion

Data analyses revealed that @healthchina utilized the discursive strategies of nomination and predication to construct various images of Chinese HCWs during the COVID-19 pandemic. These depictions portray HCWs as professional and competent in addressing the pandemic crisis, compassionate and caring to their patients, and responsible and devoted to public health as well. Below, we discuss the underlying motivations driving these image constructions.

First, we argue that the construction of HCWs’ images aimed primarily to elicit positive emotional responses from the public during the pandemic. The COVID-19 pandemic generated negative sentiment among the general population, including panic, anxiety, and stress (Lakhan et al., 2020). These adverse emotions quickly spread through online platforms, and addressing them became crucial for public health authorities to avoid collective action against the government (Bondes and Schucher, 2015). Social psychology research has shown that prosocial appeals play a vital role in public health communication during a crisis and that describing behaviors that result in positive outcomes during public health crises can instill hope, joy, and other positive emotions (Nabi et al., 2018). Prosocial public health messages can evoke positive responses by emphasizing actions that contribute to social and communal well-being rather than solely focusing on self-interest. As such, highlighting the professional competence, compassionate conduct, and various prosocial qualities of Chinese HCWs, including their dutifulness, dedication, selflessness, and prioritization of collective welfare over personal interests, served as an effective form of prosocial discourse that elicited positive emotional responses in the face of the pandemic threat.

Additionally, the image construction of HWCs was closely tied to the government institution’s efforts to restore trust during the pandemic. Trust has been defined as “the willingness of a party to be vulnerable to the actions of another party based on the expectation that the other will perform a particular action important to the trustor” (Mayer et al., 1995, p. 712). Three key factors are considered crucial for evaluating trustworthiness: ability, integrity, and benevolence (Mayer et al., 1995; Wang and Yao, 2022; Wang and Cao, 2023). Ability refers to the trustee’s expertise and competence in a specific domain, integrity relates to their moral and ethical values, and benevolence encompasses their care and concern for the trustor.

The COVID-19 pandemic instilled uncertainty in society, leading to a decline in trust in public health authorities, particularly during the initial stages of the pandemic. It manifested in public suspicion regarding the authorities’ ability, integrity, and benevolence in relation to combating the pandemic. In response, @healthchina took measures to counteract distrust and restore trust. The positive portrayal of HCWs served as one such measure. By presenting HCWs as competent and confident experts in the fight against the pandemic, @healthchina aimed to reassure the public that their well-being and safety were in capable hands. By emphasizing the responsibility and dedication of Chinese HCWs, @healthchina sought to restore faith in the integrity of the healthcare system, assuring the public that they are trustworthy and dedicated to the welfare and health of the population. Lastly, by depicting HCWs as compassionate and caring to their patients, @healthchina fostered a sense of mutual care and solidarity, strengthening the bond between the public and HCWs and, to some extent, repairing the damaged sense of benevolence. Consequently, it can be concluded that the construction of these three types of HCW images by @healthchina aligns with their objective of restoring trust in their ability, integrity, and benevolence, with the ultimate goal of repairing public trust in China’s public health authorities and the government as a whole.

Finally, these image constructions significantly fostered social cohesion amidst the collective battle against COVID-19. The pandemic created a sense of shared adversity and a common goal of overcoming the health crisis and increasing population identification (Zagefka, 2021). In this context, depicting HCWs as professional experts, compassionate caregivers, and individuals with noble qualities instilled a sense of unity and solidarity among the public. Such portrayals highlighted the selfless dedication and bravery exhibited by HCWs in the face of unprecedented challenges. By emphasizing their role as front-line heroes, @healthchina and other entities contributed to the creation of a “shared fate” and “collective identity” (Zagefka, 2021) centered around the valiant efforts of HCWs.

These portrayals also promoted a sense of shared responsibility and mobilized collective action. By showcasing the commitment and sacrifices made by HCWs, they inspired individuals to adhere to health guidelines, take necessary precautions, and support public health initiatives. The positive images of HCWs were intended to encourage the public to rally together, showing solidarity and cooperation in adhering to preventive measures and working toward the common goal of mitigating the impact of the pandemic.

Furthermore, the portrayals of Chinese HCWs as compassionate caregivers evoked empathy and appreciation from the public. The recognition of HCWs’ tireless efforts and the portrayal of their caring nature fostered a sense of gratitude and respect toward HCWs. Consequently, these portrayals deepened the bond between the public and HCWs, fostering a collective appreciation for their invaluable contributions to the well-being of society. This approach in government communication during the pandemic is widely recognized as one of the best practices in Kim and Kreps (2020), as it effectively promoted unity and solidarity within the community.

Overall, portrays of HCWs during the pandemic had a profound impact on promoting social cohesion, which aligns with the findings of Jewett et al. (2021). They fostered unity, inspired collective action, and evoked empathy and gratitude within the community. By highlighting medical workers’ heroism and noble qualities, such portrayals reinforced the shared values and aspirations in the fight against COVID-19, ultimately forging a stronger, more resilient society.

The study boasts both theoretical and practical implications. Theoretically, this study offers a new perspective into the intricate dynamics of image construction and discursive practices. Practically, the findings provide valuable insights and actionable guidelines for organizations and governments to communicate with the public during public health crises strategically. Understanding these discursive strategies enables practical public relations efforts, empowering governmental institutions to mold a positive public perception of healthcare workers and reinforce trust in healthcare institutions.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

XW: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ZZ: Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The study is supported by Project of Modern Educational Technology in Jiangsu Province (grant no. 2021-R-92296).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the reviewers for their insightful and helpful comments on the different versions of this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

References

Abdel-Raheem, A. (2021). Where Covid metaphors come from: Reconsideringcontext and modality in metaphor. Soc. Semiot. 33, 971–1010. doi: 10.1080/10350330.2021.1971493

Adam, J. G., and Walls, R. M. (2020). Supporting the health care workforce during the COVID-19 global epidemic. JAMA 323, 1439–1440. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3972

Alonso Belmonte, I., McCabe, A., and Chornet-Roses, D. (2010). In their own words: the construction of the image of the immigrant in peninsular Spanish broadsheets and freesheets. Discourse Commun. 4, 227–242. doi: 10.1177/1750481310373218

Andreouli, E., and Brice, E. (2020). Citizenship under COVID-19: an analysis of UK political rhetoric during the first wave of the 2020 pandemic. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 32, 555–572. doi: 10.1002/casp.2526

Berrocal, M., Kranert, M., Attolino, P., Santos, J. A. B., Santamaria, S. G., Henaku, N., et al. (2021). Constructing collective identities and solidarity in premiers’ early speeches on COVID-19: a global perspective. Human. Soc. Sci. Commun. 8, 128–139. doi: 10.1057/s41599-021-00805-x

Billig, M. (2021). Rhetorical uses of precise numbers and semi-magical round numbers in political discourse about COVID-19: examples from the government of the United Kingdom. Discourse Soc. 32, 542–558. doi: 10.1177/09579265211013115

Bondes, M., and Schucher, G. (2015). “Derailed emotions: the transformation of claims and targets during the Wenzhou online incident” in The internet, social networks and civic engagement in Chinese Society. ed. W. Chen (London: Routledge), 21.

Chen, X., and Jin, Y. (2022). Image construction: its connotations, types and discursive practices. Foreign Lang. Learn. Theory and Prac. 3, 1–12,

Chepurnaya, A. (2021). Modeling public perception in times of crisis: discursive strategies in Trump’s COVID-19 discourse. Crit. Discourse Stud. 20, 70–81. doi: 10.1080/17405904.2021.1990780

Flusberg, S., Matlock, T., and Paul, T. (2018). War metaphors in public discourse. Metaphor. Symb. 33, 1–18. doi: 10.1080/10926488.2018.1407992

Heritage, J. (2012). Epistemics in action: action formation and territories of knowledge. Res. Lang. Soc. Interact. 45, 1–29. doi: 10.1080/08351813.2012.646684

Jarvis, L. (2022). Constructing the coronavirus crisis: narratives of time in British political discourse on COVID-19. Br. Polit. 17, 24–43. doi: 10.1057/s41293-021-00180-w

Jewett, R., Mah, S., Howell, N., and Larsen, M. (2021). Social Cohesion and Community Resilience During COVID-19 and Pandemics: A Rapid Scoping Review to Inform the United Nations Research Roadmap for COVID-19 Recovery. International Journal of Health Services 51, 1–12. doi: 10.1177/0020731421997092

Kim, D. K., and Kreps, G. L. (2020). An analysis of government communication in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic: recommendations for effective government health risk communication. World Med. Health Policy 12, 398–412. doi: 10.1002/wmh3.363

Lakhan, R., Agrawal, A., and Sharma, M. (2020). Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress during COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Neurosci. Rural Prac. 11, 519–525. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1716442

Manning, M. L., Dorothy, L. B., and Rumovitz, D. M. (2012). Infection preventionists’ job descriptions: do they reflect expanded roles and responsibilities? Am. J. Infect. Control 40, 888–890. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2011.12.008

Mayer, R. C., Davis, J. H., and Schoorman, F. D. (1995). An integrative model of organizational trust. Acad. Manag. Rev. 20, 709–734. doi: 10.2307/258792

Mushin, I. (2000). Evidentiality and deixis in narrative retelling. J. Pragmat. 32, 927–957. doi: 10.1016/S0378-2166(99)00085-5

Nabi, R. L., Gustafson, A., and Jensen, R. (2018). Framing climate change: exploring the role of emotion in generating advocacy behavior. Sci. Commun. 40, 442–468. doi: 10.1177/1075547018776019

Rafaeli, A., and Pratt, M. G. (2013). Artifacts and organizations: Beyond mere symbolism. London: Psychology Press.

Reisigl, M., and Wodak, R. (2016). “The discourse-historical approach (DHA)” in Methods of critical discourse studies. eds. R. Wodak and M. Meyer (London: SAGE).

Seixas, E. C. (2021). War metaphors in political communication on COVID-19. Front. Sociol. 5, 1–11. doi: 10.3389/fsoc.2020.583680

Semino, E. (2021). Not soldiers but fire-fighters: metaphors and COVID-19. Health Commun. 36, 50–58. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2020.1844989

Sun, X., and Chałupnik, M. (2022). Sacrificing long hair and the domestic sphere: reporting on female medical workers in Chinese online news during COVID-19. Discourse Soc. 33, 650–670. doi: 10.1177/09579265221096029

Takovski, A. (2021). Political alliance with COVID-19: Macedonian politics and the strategic use of the pandemic. Discourse Soc. 33, 215–234. doi: 10.1177/09579265221088156

Valdebenito, M. S. (2013). Image repair discourse of Chilean companies facing a scandal. Discourse Commun. 7, 95–115. doi: 10.1177/1750481312466474

Wang, X. (2016). A struggle for trustworthiness: local officials’ discursive behaviour in press conferences handling Tianjin blasts in China. Discourse Commun. 10, 412–426. doi: 10.1177/1750481316638150

Wang, X., and Cao, R. (2023). “Thanks for trusting me, parent”: Chinese pediatricians’ epistemic behaviour for trustworthiness in online medical consultations. East Asian Pragmatics 8, 271–289. doi: 10.1558/eap.22552

Wang, H., and Ge, Y. (2022). The discursive (re)construction of social relations in a crisis situation: a genre analytical approach to press conferences on COVID-19 in China. Front. Psychol. 13, 1–13. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.991813

Wang, X., and Liu, D. (2019). Discursive behaviours for trust-repair in crisis: a text analysis of BP’s letters to shareholders after oil spill crisis. Foreign Lang. Res. 5, 43–48,

Wang, X., and Yao, H. (2022). In government microblogs we trust: doing trust work in Chinese government microblogs during COVID-19. Discourse Commun. 16, 716–734. doi: 10.1177/17504813221109090

Williams, J., and Wright, D. (2022). Ambiguity, responsibility and political action in the UK daily COVID-19 briefings. Crit. Discourse Stud. 21, 76–91. doi: 10.1080/17405904.2022.2110132

Wodak, R. (2001). “The discourse-historical approach” in Methods of critical discourse analysis. eds. Wodak and M. Meyer (London: Sage).

Yan, W., and Huang, J. (2014). Microblogging reposting mechanism: an information adoption perspective. Tsinghua Sci. Technol. 19, 531–542. doi: 10.1109/TST.2014.6919830

Zagefka, H. (2021). Intergroup helping during the coronavirus crisis: effects of group identification, ingroup blame and third party outgroup blame. J. Commun. App. Soc. Psychol. 31, 83–93. doi: 10.1002/casp.2487

Zappavigna, M. (2016). Social media photography: construing subjectivity in Instagram images. Vis. Commun. 15, 271–292. doi: 10.1177/1470357216643220

Keywords: healthcare workers, government Weibo, image construction, discursive strategies, discourse-historical analysis

Citation: Wang X and Zheng Z (2024) Constructing images of HCWs in Chinese government Weibo posts: a discourse-historical approach. Front. Commun. 9:1320228. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2024.1320228

Edited by:

Xuefan Dong, Beijing University of Technology, ChinaReviewed by:

Ning Ma, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, ChinaYing Lian, Communication University of China, China

Yang Bo, Data Mining Time Series Prediction Time Delay Analysis, China

Barton Buechner, Adler School of Professional Psychology, United States

Copyright © 2024 Wang and Zheng. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xueyu Wang, d2FuZ3h1ZXl1MjAxMkBnbWFpbC5jb20=

Xueyu Wang

Xueyu Wang Zheng Zheng

Zheng Zheng