- Department of Media and Business Communication, Institute Human-Computer-Media, University of Würzburg, Würzburg, Germany

Contemporary events are marked by profound social changes and the resulting insecurity among many people. Political appeals on an emotional level and beyond facts are therefore currently popular. The German construct of Heimat conveys feelings of safety and shelter like no other. It is therefore not surprising that the term is instrumentalized in political advertising across the entire party spectrum in Germany. In an empirical study, the influence of Heimat references in visual political advertising on the attitudes of recipients is examined, whereby the feelings of Heimat evoked are modeled as a mediator of this relationship. It is assumed that the strength of this affective influence depends on the moderators information processing (heuristic or substantive) and the personality expression on the factor neuroticism. Party identification complements the model, also moderated by information processing, as an additional factor influencing political attitudes. The results show, however, that the explanatory power for the feeling of Heimat is rather to be found in the identification with the communicating party. Against this background, the persuasive instrumentalization of a feeling of Heimat for the evaluation of political issues can certainly be worthwhile. In this context, it is not decisive whether the content of the advertising material explicitly references the Heimat issue, but how the party itself is perceived by the recipients. No effects were found for personality and information processing.

1 Introduction

The present is characterized by numerous social developments such as economic globalization (Südekum et al., 2017), comprehensive digitalization (Kollmann and Schmidt, 2016), and various migration movements (Bade, 2018). These require adaptation and create feelings of insecurity among a large part of the population. In this regard, a trend is currently noticeable, a development toward “subliminal, long-term longings for anchoring, security, and deceleration” (Schipperges et al., 2016, p. 15, translation added). Like hardly any other term, Heimat 1 and all the associations related to it are likely to feed into these longings: According to a representative survey in Germany, many people associate the term with positive social relationships, emotional components such as a sense of security, but also with references to place and cultural aspects (Schröter, 2016). This is also reflected in the use of media content for entertainment purposes, as, for example, the longing for an “ideal world” was identified as an important reception motive for Heimat-related TV series (Schramm et al., 2020, p. 176).

It is therefore not surprising that advertisers in Germany use the concept of Heimat. Hardly any other field tries to instrumentalize the topic of Heimat in its various facets as strongly as political advertising. In the run-up to many German elections in recent years, the parties across the whole political spectrum have used the term to describe the core virtues of their own position: Schramm and Liebers (2019, p. 259) provided a collection of slogans, for example by the German regional party CSU (Christian Social Union) in the 2018 Bavarian state election campaign [“Heimat—Unsere bayerische Lebensart erhalten” (Heimat—Preserving our Bavarian way of life; translation added)] and the green party in the 2018 Hessian state election campaign [“Heimat? Natürlich.” (Heimat?—Naturally; translation added)].

There are several reasons why politics is currently predestined for the emotional instrumentalization of the concept of Heimat. On the one hand, the current German political party landscape is experiencing a major shift in party power relations and political attitudes (Schoen, 2019). New and hitherto unthinkable coalitions seem possible and are even becoming the norm, as demonstrated, for example, in 2018 by the continuation of the conservative-green government formation in the state elections in Hesse, Germany (cf. the analysis by Debus and Faas, 2019). On the other hand, the right-wing populist party Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) was particularly able to profit in the last elections. Among other things, feelings of insecurity, for example regarding migration policy and the resulting fears, can be seen as the cause of their rise (Hilmer and Gagné, 2018). Korte (2016, p. 90), referring to the 2016 state elections, also points out that facts are currently not the only decisive component in voting behavior for many voters, but that rather emotions play a major role: the parties' handling of emotional problems such as “fears of losing one's Heimat” [translation added] was decisive for the election.

All in all, appeals beyond purely factual content seem to work well for the electorate. The unique values embodied by the construct of Heimat seem to be ideally suited to satisfy longings for security, which German politics tries to exploit across the entire spectrum of political positions. This study therefore examines the affective influence of feelings of Heimat on the persuasive effect of political advertising.

2 Heimat and feelings of Heimat

Many different disciplines, from milieu research and evolutionary psychology to migration research, have dealt with the meaning of the concept of Heimat (for an overview, see Teubner-Guerra, 2014). In most cases, Heimat is understood as a complex concept that can take on many possible subjective forms: Mitzscherlich (2000), for example, uses a qualitative approach to identify 10 dimensions of meaning, including aspects such as the family childhood environment, a state of experience or a political-ideological construction. The reason why almost all parties can nevertheless claim the term for their position is its historical development: from its Middle and Old High German origins with the meaning of a place of settlement (Klose, 2013) to a legal claim with legal obligations (Röll, 2014), the term developed in the context of the national movement in the nineteenth century to fatherland and nation (Röll, 2014). The perceived loss of Heimat due to industrialization and rural exodus (Hammer, 2017) was followed between the two World Wars by a mystification and ideologization of the term until its misuse during the National Socialist era (Heller and Narr, 2011). Subsequently, the term was coined on the one hand against the background of all those who had been expelled from their Heimat (Heller and Narr, 2011). On the other hand, an image of Heimat developed at this time, transported in particular by the Heimatfilm genre, as a relationship to the local and social environment characterized by self-confidence and harmony (Ludewig, 2008). After the political end of the German Democratic Republic, a glorifying and nostalgic longing for a Heimat that had never really existed developed (Thompson, 2009). In the 1980's, the concept of Heimat finally took on a new meaning in the context of ecological trends and the destruction of natural space: Heimat was now interpreted both in the countryside and in the city as an environment for which responsibility had to be taken (Mitzscherlich, 2014). Especially in the context of the massive migration movements of recent years, the concept of Heimat has gained renewed relevance: Refugees and their descendants sometimes experience strong feelings of loss in relation to their Heimat or are torn between their new and old Heimat (Mitzscherlich, 2016). Even today, various of the historical aspects mentioned can still be found in the understanding of the term: be it in the radical right-wing riots of the recent past, which are still explicitly directed against foreigners in a sense of “Germany for the Germans” (Franke et al., 2009, p. 12, translation added), or a preference for an ostalgic indulgence in the past, which is often served by popular entertainment formats such as the German crime television series “Tatort” (Ludewig, 2019).

When considering the concept of Heimat, its emotional component is of particular importance (Schramm et al., 2022b). In the psychological analysis by Mitzscherlich (2000) described above, the author identified the emotional state as the most frequently mentioned of the 10 dimensions of meaning of Heimat. In the geographically oriented quantitative Heimat survey on the German region of Saarland from 2007, a feeling of security proved to be central when asked what constituted Heimat (Kühne and Spellerberg, 2010). In the media entertainment context, it could be shown that references to Heimat can trigger feelings of Heimat through an activation of Heimat-related social identity (Schramm et al., 2022a). Heimat-related social identity was also associated with positive affect and an increased evaluation of one's own social group (Breves et al., 2022). Even if the feeling of Heimat is perceived differently, the approaches are nevertheless similar in the positive valence of the emotion. Nevertheless, feelings of Heimat in their constitution as a unique emotional experience, have not yet been examined empirically in the persuasion context: Remotely similar existing approaches like the Country-of-Origin effect (e.g., Balabanis and Diamantopoulos, 2004) in the commercial advertising literature or the place identity literature known from environmental psychology (e.g., Proshansky et al., 1983), do not really capture the nature of feelings of Heimat. Their complexity is reflected in the communication science-oriented definition by Schramm et al. (2022b, p. 7), which was coined in a first step to empirically capture what constitutes this experience:

“[Feeling of Heimat] […] manifests itself on an emotional level and is usually fed by positive feelings of belonging, security, safety, and/or familiarity. [Feeling of Heimat] […] is triggered by spatiotemporal associations with a place of origin and/or refuge and its geographical surroundings, which usually corresponds to the childhood family environment but can change or expand over the course of one's life through changes in location of residence; socio-cultural associations with aspects of culture such as language, traditions, and lifestyle; and social aspects such as involvement in relationships and/or communities, as well as with cultural-ideological or political-ideological aspects such as values and norms.”

This definition identifies several aspects that can evoke feelings of Heimat. It should be emphasized that these are not necessarily positive from the outset (the childhood family environment might not have been friendly), but overall, the emotional experience nevertheless seems to consist of predominantly positively connoted components. This can also be seen in the study by Schramm et al. (2022a), who were able to identify the following components as part of their development of a scale to empirically assess the feeling of Heimat: The emotional experience according to this consists of affection, belonging, comfortable feeling, emotional security, familiarity, happiness, joy, longing, proudness, quietness, safety, solidarity, and warmth. This is probably the reason for its attempted instrumentalization in the political context. In an interview, Lessenich reveals that the concept of Heimat is viewed by politicians as being able to “touch people's collective psyche” (Lessenich et al., 2019, p. 8, translation added). In this sense, the concept of Heimat itself can be regarded as having a clearly positive emotional impact (Lessenich et al., 2019). In other words, a feeling of Heimat seems to be an emotion that can be expected to be processed very differently from one individual to another, but nevertheless to be perceived positively in most cases. In view of the widespread use of Heimat-related political advertising in Germany described above, this raises the question of the extent to which political advertising slogans are able to evoke this complex emotional experience at all and whether this pays off persuasively in the desired sense for the party.

3 Political advertising

3.1 Political persuasion

In Germany, there is a high demand for research on political advertising, especially on election posters as central campaign media (Podschuweit, 2016). Persuasion can be regarded as a political target and core process and thus represents a discrete research strand (Mutz et al., 1999). Petty and Cacioppo (1996, p. 4) provide a definition of persuasion as “any instance in which an active attempt is made to change a person's mind.” One of the persuasive effects of political communication is the attitude effect (Reinemann and Zerback, 2013). Attitude is usually understood as the overall evaluation of an object, which can adopt different valences (e.g., Petty et al., 1997). Depending on the objective of the advertising, this can, for example, concern content, persons, or parties whose evaluation should be more positive or more negative after the reception.

Whether and how advertising unfolds its persuasive effect can depend on various factors. In view of the current political situation, which is characterized by uncertainties and changes, three variables in particular are brought into focus for the context of the present study: the influence of emotions as an important component in addition to content appeals, the personality of the recipients as an influencing factor on the perception of the current situation and, last but not least, party identification in a political environment whose balance of power is in flux.

3.2 Influence of emotions in political persuasion

Empirical research has already investigated the emotional effects of political advertising in many ways.2 On the one hand, political advertising seems to be fundamentally capable of triggering emotions on the part of the recipients: This ability was shown against the backdrop of many different contexts, be it images and music in real campaigns (Brader, 2005), TV spots in the run-up to the German election in 1990 (Kaid and Holtz-Bacha, 1993) or right-wing populist advertising posters (Matthes and Marquart, 2013). On the other hand, the attitudinal effect of political advertising seems to come about indirectly via the emotions of the recipients: Wirz (2018) investigated the emotional and persuasive potential of populist advertising posters. Attitudes were influenced indirectly, via the mediating effect of evoked emotions. Schemer (2010) conducted a multi-wave telephone survey in the context of an upcoming vote in Switzerland in 2006 on a tightening of the asylum law. The focus was on posters and advertisements as well as the positive and negative emotions perceived toward asylum seekers and the asylum law. The emotions evoked by political advertising mediated the effect of advertising on attitudes according to their valence.

In addition, information processing plays a decisive role in influencing attitudes: In order to be able to deal specifically with affective influences in the formation of judgments, Forgas (1995) developed the Affect-Infusion-Model (AIM) on this basis, in which four strategies are distinguished: direct access, motivated, heuristic and substantive processing. According to Forgas (1995), direct access and motivated processing are characterized by predetermined and direct information searches. The information processing is therefore not open-ended and can only be influenced to a limited extent by affects, which is why they are not considered further here. On the other hand, processing methods that are open to the influence of affect are therefore substantive and heuristic processes. A direct way in which affects can influence attitude formation in terms of heuristic processing is the affect-as-information mechanism described by Schwarz and Clore (1988): One's own affective state functions as information about how a certain attitude object is to be evaluated. If, on the other hand, substantive processing takes place, an affect-priming mechanism, i.e., an influence of affect by indirect means, as described by Bower (1981), is to be expected: according to this, an affective state activates similarly valenced memory contents, which are thus more likely to be recalled. In both cases, the recipient's attitude should depend on the valence of the affective state. In the case of the affect-infusion model, a greater influence of effect on the formation of judgments can be assumed in the case of substantive processing.

Petty et al. (1993) conducted two experiments to test the influence of positive and neutral moods on persuasion as a function of information processing. Both studies showed that positive moods exerted an indirect influence at a high level of processing and a direct influence at a low level of processing. The study by Kühne et al. (2012), which explicitly examined the affect-infusion model on the basis of newspaper articles on the topic of organ donation, points in a similar direction. They investigated the question of how moods influence the formation of attitudes during the reception of news. Information processing was manipulated in terms of heuristic and substantive processing. Positive mood led to more positive attitudes toward the topic, negative mood to more negative ones. They were able to at least partially confirm the assumptions underlying the affect-infusion model about the mechanisms described: On the one hand, the presumed effects for heuristic and substantive processing were shown, but the results also pointed to mixed forms in processing.

With regard to the strength of the influence of affect, the results of Huddy and Gunnthorsdottir (2000) prove to be interesting. Within the framework of a study, they examined the influence of emotions in connection with the degree of involvement with a topic. They used positively and negatively valenced emotional flyers on the topic of environmental protection. The results showed that there was no simple transfer of affect among the uninformed, but rather a stronger emotional influence in connection with a more in-depth discussion of the content.

All in all, political advertising seems to be able to evoke emotions in recipients, which act as mediators in the process of influencing attitudes. The emotions influence the attitudes of the persons either directly through heuristic or indirectly through substantive information processing. A stronger influence of emotions is to be expected for substantive processing. Since the integration of references to Heimat into the political advertising communication of German parties is widespread, three questions arise, that have not yet been investigated in this context: Firstly, it should be examined whether the simple integration of Heimat into political election slogans is sufficient to trigger the complex experience of the positively connoted feelings of Heimat introduced above. Secondly, it is of great interest whether the instrumentalization of this specific experience ultimately pays off persuasively in the interests of the advertisers as it is known from for example emotional imagery. And thirdly, we are concerned with the question of which underlying mechanisms of information processing exert influence here.

3.3 Influence of personality in political persuasion

The personality of the recipients can sometimes be assumed to have a similarly large influence on political attitudes and behavior as is the case with the common variables of income or education (Gerber et al., 2010).

Five dimensions known as the Big Five can be commonly used to measure personality, which according to Goldberg (1993) are called Extraversion, Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, Neuroticism and Openness to Experience. According to Neyer and Asendorpf (2018), the factors each make their own statements about the characteristics of a personality: extraversion goes hand in hand with sociability, among other things, agreeableness refers to warmth in dealing with others. Conscientiousness draws on aspects such as orderliness, whereas neuroticism is associated with anxiety and emotional fluctuations. Finally, openness to new experiences refers to a person's intellectual curiosity, among other things.

In view of the political situation described above, a large proportion of the electorate is likely to have emotional states that are particularly associated with the neuroticism factor. Gallego and Pardos-Prado (2014) showed in a study that a correlation can be found between the expression of personality on the neuroticism factor and attitudes toward immigrants: More neurotic persons showed more negative attitudes. If one considers the so-called refugee crisis as a symbol of change and insecurity for many people, it would be reasonable to assume that neurotic people have stronger negative feelings. Analyses such as those by Schoen and Schumann (2007) point in a similar direction: For the German population, it could be shown that neurotic persons prefer those parties that stand for protection against challenges, for example of a cultural nature.

In this context, studies such as the one by Berenbaum et al. (2008) are also interesting: It could be shown that there is a strong connection between neuroticism and insecurity. However, the more neurotic the person, the more pronounced were also unpleasant feelings toward insecurity. A study by Hirsh and Inzlicht (2008) shows a similar perspective: Using a task to estimate the duration of a past period of time, participants were given either positive, negative or uncertain feedback. More neurotic individuals even reacted physically in their brain more strongly to uncertain than to negative feedback. In the end, the researchers conclude that neurotic individuals may even prefer negative to uncertain feedback. Considering these results altogether, feelings of security and warmth—in the context of the present study represented by the construct of Heimat—could thus provide a remedy for the unpleasant emotions of neurotic persons. In other words, as huge parts of the electorate might be bewildered by current political happenings in an increasingly fast-paced world, it seems only logical that in face of these threats, especially neurotic people must deal with feelings of insecurity and fear. So, in a situation where they are confronted with political advertising, the emotional components of experiencing feelings of Heimat are likely to fall on fertile ground with these people. If the party is able to use its advertising to provide relief from unpleasant emotions, this should make recipients more open to its content, which should pay off in a more positive attitude toward the advertised topic.

3.4 Influence of party identification in political persuasion

The great importance of party identification for the study of political events can already be seen in the integration of the concept in the classic models and studies of the discipline: Campbell et al. (1960) include party identification in their work “The American Voter”, and decades later Miller and Shanks (1996) also devote an entire section to party identification in “The New American Voter” as an explanatory variable for voting behavior. Party identification can be understood as “a stable, emotional attachment of individuals to particular political parties”, which represents a “core component of individuals' self-definition” (Schmitt-Beck and Weick, 2001, p. 1, translation added). It serves as a heuristic with an orientation function for voters in a complex political world, whereby in Germany a distinction is commonly made between the presence, direction, and strength of party identification (Kroh, 2020).

The question of how the party, identification with it and the reception of political content interact has already been analyzed empirically many times. In an experiment, for example, Rahn (1993) examined the use of party stereotypes as heuristics for the evaluation of candidates. The data showed that the recipients were capable of forming judgments from the processing of given content-related information but relied—if available—on the party of the respective candidate in forming their judgments. The party as a heuristic was superior to the candidate's assessment of content as a basis for evaluation. Bartels (2002) was also able to show that party identification influences the perception of the political world: In his analyzed panel data, correlations were found between party identification and the evaluation of objective economic data within all forms of party identification. The situation was assessed differently depending on which political side one belonged to and whether it agreed with the incumbent and thus responsible president. The results of Cohen (2003), who carried out a whole series of studies, go in a similar direction. It was shown that the recipients rated the content that was apparently represented by their preferred party as better. The communicating party had a greater influence than the content itself, without the recipients being aware of this. The results of Hawkins and Nosek (2012) go in a similar direction and even beyond in this context. People who claimed to be politically independent in their assessment of content, nevertheless revealed implicit party identifications by means of an implicit association test. Here, too, these had a decisive influence on the evaluation of topics. Party identification thus seems to work not only on an explicit level, but to be a kind of reception filter for political attitudes of all persons. Overall, these studies point to a dominant influence of the extent of identification with the communicating party on received content.

Thus, an influence of party identification on the reception of political advertising is to be expected. In addition, different influences of party identification should become apparent depending on the type of information processing. More specifically, in current political times of insecurity, change and increasing complexity, people might want to rely on a simple heuristic when forming an opinion on topics. The communicating party might be just the right cue in this case, especially in a scenario where people do not want to get involved with the topic to much, but instead benefit from fast and convenient opinion forming in a sense of heuristic processing.

4 Hypotheses

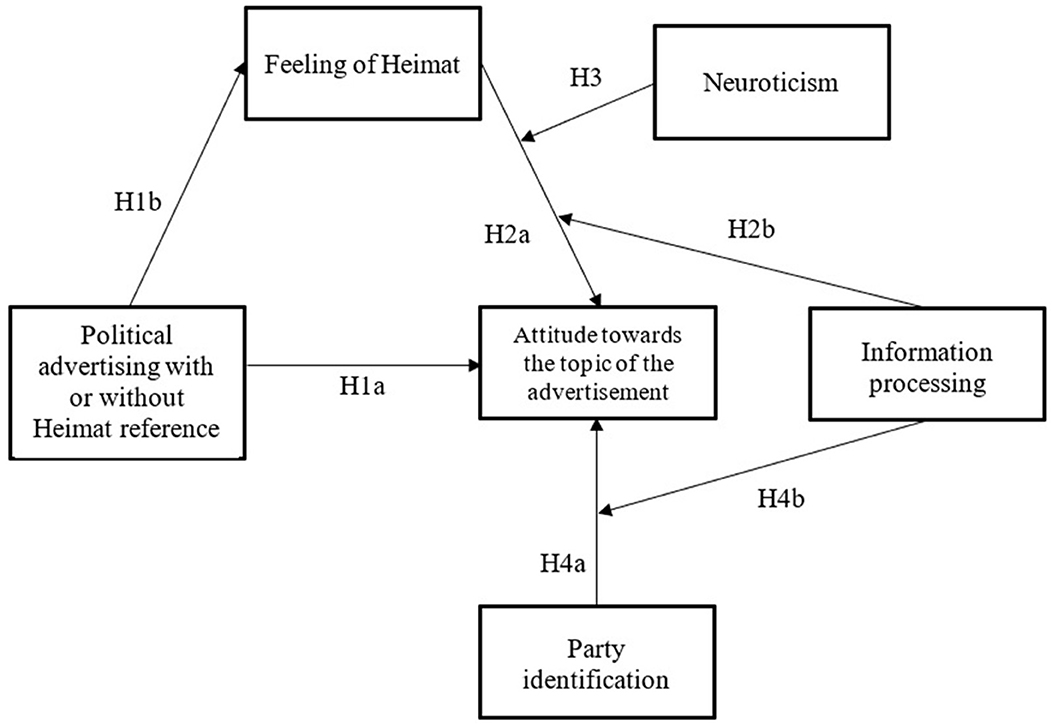

In order to translate the findings and assumptions explained in the previous part into an empirically testable model, hypotheses are developed in the following. As described, the concept of Heimat is highly subjective and thus filled with different associations. It is to be expected that these associations will tend to be positive in most cases. Therefore, a direct effect of political advertising with reference to Heimat on the attitude according to (H1a) is expected (cf. Figure 1).

(H1a) Political advertising with a reference to Heimat leads to a more positive attitude toward the content of political advertising among recipients than advertising without a reference to Heimat.

Political advertising can be assumed to be capable of triggering emotions in the recipients (e.g., Brader, 2005; Matthes and Marquart, 2013). The emotional component, in turn, is, as described, the central component of the Heimat construct and can be expected to be positive in its valence (e.g., Schramm and Liebers, 2019). If a political advertisement thus contains a reference to Heimat, then a relation according to (H1b) can be assumed.

(H1b) Political advertising with a reference to Heimat triggers a stronger feeling of Heimat in recipients than political advertising without a reference to Heimat.

This feeling of Heimat triggered by political advertising can be assumed to have an influence on the reception of the persuasive message: According to Forgas' (1995) affect-infusion model, affect can influence attitude formation in the reception process according to its valence. Since a feeling of Heimat is to be expected as a positive emotion, the attitude of the recipient should adapt to that of the communicator according to (H2a).

(H2a) The stronger the evoked feeling of Heimat, the more positive the attitude toward the content of the political advertisement turns out to be.

The Affect-Infusion-Model (Forgas, 1995) distinguishes, as described, between substantive and heuristic information processing in the potential for affect influence. According to the model assumptions and the empirical findings presented (e.g., Huddy and Gunnthorsdottir, 2000), a varying degree of influence of the feeling of Heimat can be assumed for (H2b).

(H2b) The influence of the feeling of Heimat on the attitude toward the topic is greater with substantive processing than with heuristic processing.

Regarding personality, neuroticism seems to be related to the experience of unpleasant negative emotions on the one hand and to an intolerance of uncertainty on the other. According to the definition by Schramm and Liebers (2019) used in this study, a feeling of Heimat usually stands for positive emotions with components such as safety and shelter. If political advertising evokes a feeling of Heimat among the recipients, this will exactly meet the needs of neurotic persons. Thus, according to (H3), it is to be expected that high neuroticism in connection with a feeling of Heimat leads to a greater attitude effect.

(H3) The more neurotic the recipient, the greater the influence of the feeling of Heimat on the attitude toward the topic.

As described, party identification influences people's perception of the political world in its role as a component of self-definition (e.g., Schmitt-Beck and Weick, 2001). It has been empirically shown several times that this influence even exceeds that of many other factors (e.g., Rahn, 1993; Bartels, 2002). Therefore, according to (H4a) it is to be expected that party identification exerts an independent influence on attitudes in the reception of political advertising:

(H4a) The stronger the identification of the recipient with the communicating party, the more positive the attitude toward the content of the political advertisement.

Since party identification is an influencing factor independent of the concrete content of the advertisement, the depth of information processing is likely to play a role. For the derivation of one's own attitudes, it is a simple and quickly accessible point of orientation in the political world. Especially against the background of the assumptions of the affect-infusion model (Forgas, 1995), the influence of party identification should thus be stronger in heuristic processing. This connection is described in (H4b).

(H4b) The influence of the recipient's identification with the communicating party on attitude is greater with heuristic processing than with substantive processing.

To summarize, it is assumed that a political advertisement with a reference to Heimat in the slogan has a positive effect on the experience of positive feelings of Heimat, which in turn should have a positive influence on the attitude toward the topic of the advertisement. The latter relationship should in turn be moderated by the personality characteristics of the person on the neuroticism factor and the type of information processing. In addition, a direct positive effect of a Heimat reference in political advertising on attitudes toward the topic is assumed. Party identification is assumed to be a further explanatory variable. A high degree of identification with the communicating party should have a positive effect on attitudes toward the advertised topic. This relationship should also be moderated by the type of information processing. Figure 1 shows the assumptions summarized in model form.

5 Method

5.1 Sample

Participants for the online study were recruited in Germany between 01.04.2020 and 30.04.2020 via social media and email resulting in a convenience sample. Two hundred and fifty-nine people took part in the experiment within the 4 weeks. Nine people were excluded from data analysis who were not being entitled to vote in Germany (and thus not being able to perceive the same relevance of the shown material) or whose participation behavior indicated a lack of diligence (e.g., too short time span for participation). The final sample consisted of 250 people (62% female). The average age was about 30 years (M = 30.16, SD = 11.55). Overall, the sample had a high level of formal education with an academic degree (56.0%) or high school diploma (Abitur) (30.8%) and were mainly employed (45.6%) or studying (44.0%).

5.2 Experimental design

The present study is a 2x2-between-subjects design. On the one hand, the reference to Heimat on an election poster was varied as an independent variable in dichotomous form with the characteristics “present in the slogan” or “not present in the slogan”. On the other hand, the random allocation to different groups of information processing as moderator took place, which was also dichotomously divided into substantive and heuristic processing. This was manipulated in the questionnaire following the procedure in Kühne et al. (2012): In the substantive condition, the respondent was asked to study the following poster in detail in order to be able to answer a few questions about it. In addition, the participants were informed that they could only continue with the questionnaire after a minimum observation period had elapsed. In the heuristic condition, it was asked that only a short overview should be taken, comparable to passing an election poster on the street. This was followed by the indication that after a short viewing period, the respondent was automatically directed to the further processing of the study.

Afterwards, the participants were randomly assigned to one of the poster versions, whereby the viewing time was technically controlled according to the reception instructions described above. This procedure resulted in four groups, namely one with an election poster with a reference to Heimat in the condition of substantive information processing (n = 66) and the other group with heuristic information processing (n = 52). Secondly, the other two groups received an (otherwise identical) election poster with no reference to Heimat also in one case with substantive information processing (n = 69) and in the other case with heuristic information processing (n = 63). The four resulting groups did not differ significantly with regard to age [Msubstantive_heimat = 29.23, SDsubstantive_heimat = 9.83; Msubstantive_no−heimat = 29.65, SDsubstantive_no−heimat = 11.68; Mheuristic_heimat = 29.21, SDheuristic_heimat = 9.74, Mheuristic_no−heimat = 32.46, SDheuristic_no−heimat = 14.13; Welch test, F(3, 134.11) = 0.88, p = 0.46], net income [ANOVA, F(3, 194) = 1.73, p = 0.16] and in the distribution of gender and educational qualifications (χ2-tests, all calculated χ2-values with p > 0.05).

5.3 Stimulus material

The advertising form of the political election poster was selected as the stimulus material. In German-speaking countries, this can be considered one of the most important campaign media (Podschuweit, 2016). Moreover, its reception is conceivable in both a substantive and a heuristic way: Increased interest in politics in the run-up to elections could lead to a deeper engagement with the content, while passing billboards in everyday traffic is likely to appeal to more superficial information processing.

In addition to the image content, election posters generally consist of a short text message or a slogan and a party logo (Lessinger and Holtz-Bacha, 2019). These three elements were adapted for the present study. The CSU was chosen as the communicating party, as it was shown in an analysis by Reusswig (2019) to be at the forefront of parties in both qualitative and quantitative use of the concept of Heimat. The topic was selected based on the criteria in Kühne et al. (2012): According to this, the topic should not be occupied with preconceptions on the part of recipients, as this could potentially prevent open-ended processing and thus affect influences. Secondly, the topic had to be sufficiently concrete, complex, and new for the party to enable plausible argumentation in different directions. The local election program of the CSU district association Wuerzburg (2020) actively calls for, among other things, the “examination and implementation of greening facades and roofs on public buildings” (CSU district association Wuerzburg, 2020, p. 7, translation added). The topic was judged to be appropriate because, although it is not the focus of public discussion, it can nevertheless be considered to be in line with the spirit of the time. Therefore, depending on the condition, either “Gemeinsam für die Umwelt” (“Together for the environment”) or “Gemeinsam für die Umwelt—unserer Heimat zuliebe” (“Together for the environment—for the sake of our Heimat”) was chosen as the slogan. The reference to facade greening “Fassadenbegrünungen bei öffentlichen Gebäuden fördern” (“Promote facade greening on public buildings”) remained the same as the subtitle in each case.

Based on a CDU poster from the 2017 federal election campaign, a poster was created in both versions for the study. The image of a facade with incipient greenery served as the background. At the top right, the CSU logo was inserted as a bar on a white background, while the slogans were placed slightly below the center. In the lower half, the poster was filled with graphic elements in the typical blue color scheme of the CSU.

5.4 Construct measurements

To capture recipients' thoughts and thus the depth and valence of cognitive processing the thought-listing technique according to Cacioppo and Petty (1981) respectively a slightly adapted version of the German wording in Knoll (2015) was used. Between zero and ten thoughts could be expressed within the framework of given lines, whereby one line was provided for each thought. The thoughts were coded according to their valence into positive, neutral and negative thoughts. Coding procedure was as follows: Positive thoughts were all statements that were favorable in nature toward the poster itself, its content or the advertising party (e.g., “greening the facade makes sense and looks cozy”). Negative thoughts were those that expressed rejection of the party, poster or content (e.g., “I don't trust the CSU”). Simple descriptions of content, questions without evaluative content and expressions whose valence was ambiguous were classified as neutral (e.g., “How big is the impact of a green facade on the environment?”).

A scale by Schramm et al. (2021, 2022a) was used for feeling of Heimat. A 5-point Likert scale with the poles “Not at all” to “Completely” was used to indicate the extent to which the respondent felt a certain component of the construct “feeling of Heimat” while looking at the poster. Items were such as e.g., “belonging”, “emotional security”, or “Joy”. The scale consisted of 13 items (M = 2.16, SD = 0.85) and achieved a reliability of α = 0.95.

Attitudes toward the topic of the political advertising poster were measured in two ways. Firstly, attitudes toward the overarching theme of environmental awareness, which was referenced in the slogan of all posters, were asked. For this purpose, the environmental awareness scale by Bernhardt (2019) was used, which in her study combined three items from Schuhwerk and Lefkoff-Hagius (1995) respectively their German translation by Schmuck et al. (2018) as well as four items from Ellen et al. (1991) in her own translation into an overall scale. Participants were asked to indicate their agreement on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from “Do not agree at all” to “Fully agree.” Items were e.g., “I care about the environment”, “I am prepared to make sacrifices to protect the environment”, or “I can think of many things I would rather do than work on improving the environment” (reverse coded). Two items were excluded in favor of higher reliability. Overall, the final scale consisted of five items (M = 5.6, SD = 1.00) and achieved a reliability of α = 0.77.

In order to live up to the concrete topic of facade greening, which is explicitly referenced both visually and in the text, an additional scale was developed for this study. A 5-point Likert scale was used to measure agreement with various statements on facade greening, ranging from “Do not agree at all” to “Fully agree.” Items included statements like “For me, the advantages of facade greening outweigh the disadvantages.” or “Facade greening is an important step in the fight against climate change”. Two items were excluded in favor of a higher reliability, so that the final scale consisted of five items (M = 3.19, SD = 0.86) and achieved a reliability of α = 0.81.

A scale by Ohr and Quandt (2012) based on items by Gluchowski (1983) was used for party identification. We used standard wording for asking for party identification in Germany (see Ohr and Quandt, 2012) to introduce the question and adapted it for the party CSU which was used in the stimulus material: “Many people in Germany identify more or less strongly with a particular political party over a longer period of time. How do you feel about the CSU?”. Afterwards we presented items capturing party identification based on past experiences (“The CSU has been done a lot for people like me”; “Once I've decided in favor of the CSU, I'm sticking with it”), emotional attachment (“I feel closely connected to the CSU”; “The CSU means a lot to me”) and judgments based on content-related position (“The positions of the CSU help me to find my way in politics”; “The CSU stands for my values and core believes”). Participants were asked to indicate on a 4-point Likert scale the extent to which they agreed with these statements ranging from “Do not agree at all” to “Fully agree”. One item was removed in favor of a higher reliability, so that the remaining scale comprised six items (M = 1.49, SD = 0.54) with a reliability of α = 0.87.

The personality dimension neuroticism was assessed with the version of the Big Five Inventory verified by Lang et al. (2001) for different age groups. On a 5-point Likert scale, statements were to be rated in terms of their degree of fit to the person between “Does not apply at all” and “Applies completely”. Items included responding to whether someone “…worries a lot”, “…becomes easily nervous and insecure,” or “…is not easily upset” (reverse coded). The final scale contained seven items (M = 2.61, SD = 0.73) and achieved a reliability of α = 0.81.

All scales used thus achieved acceptable to excellent reliabilities across the board, suggesting that they were suitable for the present study to measure the respective constructs. The procedures reported in the results section are based on the respective mean indices calculated for the individual scales on environmental awareness, facade greening, neuroticism and party identification, or the sum index for the thoughts expressed.

5.5 Manipulation check

The information processing was manipulated as described on the one hand by an according instruction and on the other hand by technically controlling the viewing duration. A successful manipulation would mean a higher depth of processing with substantive than with heuristic processing. As a measure of this, the number of thoughts expressed was combined into an index as described. It turned out that the participants in the condition of substantive information processing expressed slightly more thoughts (M = 3.89, SD = 2.13, n = 135) than those in the heuristic condition (M = 3.61, SD = 1.89, n = 115) on a descriptive level, but the difference tested by a t-test was not significant [t(248) = 1.09, p = 0.14]. Thus, based on the thoughts expressed, it cannot be assumed that there is a different depth of processing and thus also not a successful manipulation. However, since only the number of thoughts was coded on the basis of completed lines in the questionnaire, without taking potential differences in length or depth of content into account, reference is made here to the different reception instructions and viewing times: Participants in the substantive condition were nevertheless exposed to the stimulus for a longer period of time—and this in the knowledge that they would be asked questions about it after the reception. A more targeted and potentially deeper processing can therefore still be assumed. For the following hypothesis-related evaluation of the results, it is therefore initially assumed that the two different types of information processing are present. Subsequently, however, the underlying mechanism of information processing will be examined again in detail within a post-hoc analysis.

6 Results

As the model assumes indirect effects respectively moderated effects, we chose to calculate mediation and moderation models according to Hayes (2018). The calculation of all mediation and moderation models for testing the hypotheses was carried out in SPSS (v. 21) using Hayes' (2018) PROCESS (v. 3.5). An alpha level of 0.05 was used for all statistical analyses. Effects were assessed using bootstrapping percentile confidence intervals based on 10,000 draws.

6.1 Hypothesis evaluation

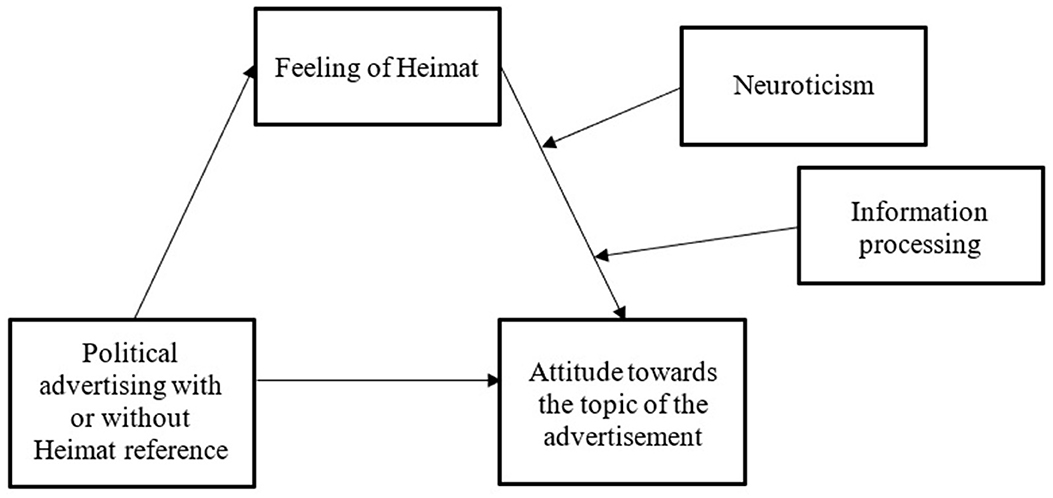

In the hypotheses on the feeling of Heimat, it was assumed that it acted as a mediating variable in the relationship between reference to Heimat and attitude toward the topic. Both a direct effect of the Heimat reference on the attitude (H1a) and an indirect effect via the evoked feeling of Heimat (H1b) were expected. The assumed positive influence of the feeling of Heimat (H2a) is moderated by the factors information processing (H2b) and neuroticism (H3).

Figure 2 shows the model to be examined.

Since the topic was operationalized in two ways for the attitude measurement of the dependent variables, the evaluation took place for both environmental awareness and facade greening using PROCESS model no. 16 in both cases.

The data showed that a Heimat reference in the slogan did not exert a significant direct effect on the dependent variable attitude toward the topic of environmental awareness (b1 = 0.151, p = 0.241). For the topic of facade greening, a negative relation contrary to the hypothesis was found: a slogan without reference to Heimat led to a better evaluation of the topic by ~0.3 points (b1 = 0.297, p = 0.005). Hypothesis (1a) must therefore be rejected. Furthermore, the presence of a reference to Heimat should trigger a stronger feeling of Heimat (H1b). This assumption cannot be confirmed based on the data either (b2 = −0.196, p = 0.069). Within the framework of hypothesis (2a), it was assumed that a stronger sense of Heimat would lead to a more positive attitude toward the topic. Although the data did not show a corresponding correlation for the attitude toward environmental awareness (b3 = −0.239, p = 0.395), for the topic of facade greening a feeling of Heimat that was one unit stronger led to a rating of facade greening that was about half a point better (b3 = 0.517, p = 0.024). Thus, hypothesis (2a) can be partially accepted. Information processing did not interact with the influence of the feeling of Heimat on the attitude toward environmental awareness (b5 = 0.201, p = 0.180) or toward facade greening (b5 = 0.015, p = 0.906), as assumed in hypothesis (2b). For the personality factor neuroticism, there was no interaction either with environmental awareness (b4 = 0.035, p = 0.735) or with facade greening (b4 = −0.078, p = 0.347). Thus, hypotheses (2b) and (3) also find no confirmation in the data.

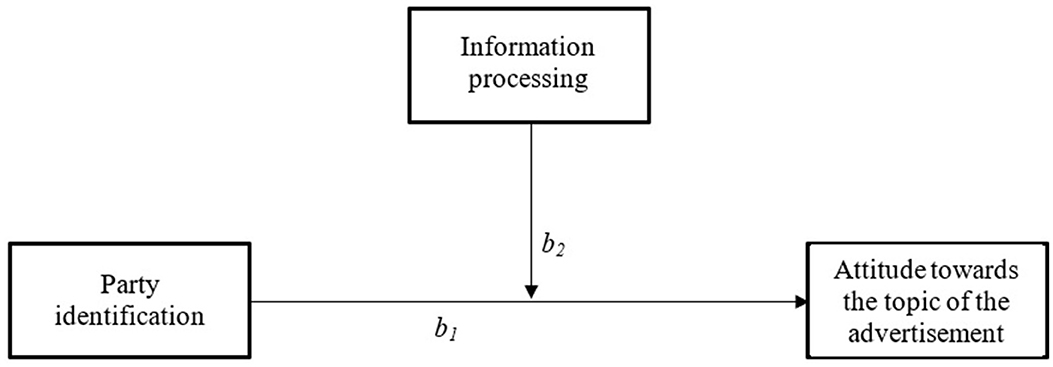

According to hypothesis (4a), a positive correlation between party identification and attitude toward the topic of the advertisement was assumed. According to hypothesis (4b), a moderating function of information processing was also to be expected. This further model is shown in Figure 3 below.

PROCESS model no. 1 was used here. Basically, only party identification seems to have an influence on attitudes toward environmental awareness (b1 = −0.617, p = 0.000). The negative valence is against the direction of the presumed relationship. However, the interaction with information processing was not significant (b2 = 0.310, p = 0.175). At 7.3%, the overall model has a significant (p = 0.003) but rather low explanatory power. Since a significant value was only found for party identification, a new analysis was carried out excluding the interaction: This results in a simple regression analysis for the correlation between party identification and attitude toward environmental awareness. This showed a significant correlation of b1 = −0.465 (p = 0.000). Contrary to expectations, however, the increase in party identification by one unit was accompanied by a decrease in agreement on the topic of environmental awareness by almost half a point.

There was no influence of party identification on attitudes to the topic of facade greening (b1 = −0.176, p = 0.212), and there was no interaction with information processing (b2 = 0.238, p = 0.243). Thus, hypotheses (4a) and (4b) cannot be accepted either.

6.2 Post-hoc analysis of information processing

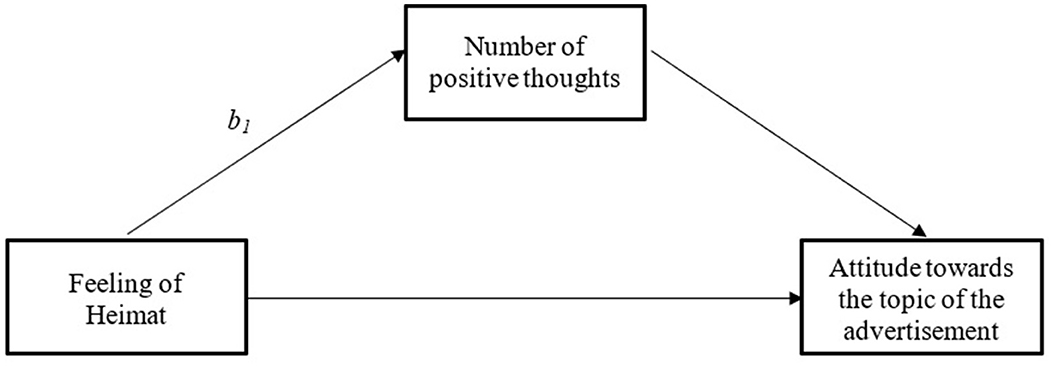

According to the assumptions of the affect-infusion model by Forgas (1995) used as a basis in the theory section, the influence of affect in substantive processing should occur via an indirect pathway, mediated by positive thoughts. With heuristic processing, on the other hand, a direct influence of affect is to be expected. For verification, four simple mediation models (PROCESS model no. 4) were calculated according to Hayes (2018). Analogous to the previous analyses, the calculations according to Figure 4 were also calculated here once for the superordinate topic of environmental awareness and once for the specific topic of facade greening.

Overall, a successful manipulation could not be assumed; regardless of the intended experimental group, various mixed forms of information processing or the underlying mechanisms were found.3 Interestingly, however, the feeling of Heimat was able to evoke positive thoughts in the recipients in all conditions. In the conditions originally intended as substantive, a one unit stronger feeling of Heimat led to ~1 more thought expressed (b1 = 1.004; p = 0.000). In the group thought to be heuristic, a one unit stronger feeling of a sense of Heimat still led to about half a thought more (b1 = 0.622; p = 0.000).

6.3 Derivation and testing of a post-hoc model

Looking closely at the results from the two previous sections, two main aspects stand out: party identification did not function as a kind of positive filter on recipients' attitudes, as had been assumed. Instead, attitudes toward the topic were more negative among those who identified more strongly with the party. People who sympathize with the CSU thus seem to be critical of the topic of environmental awareness based on this data. At the same time, the post-hoc analysis showed that the manipulation of information processing had not led to the different intended groups. Instead, it revealed that, interestingly, feeling of Heimat was able to evoke positive thoughts in the recipients regardless of the originally intended experimental condition. However, the perceived feeling of Heimat was not generated from the literal reference to Heimat in the slogan, as had been assumed. This raised the question of whether such an explicit reference was necessary at all for a party like the CSU: with its own regional reference and programmatic focus on Heimat, it could have been responsible in itself for the feeling of Heimat for many people.

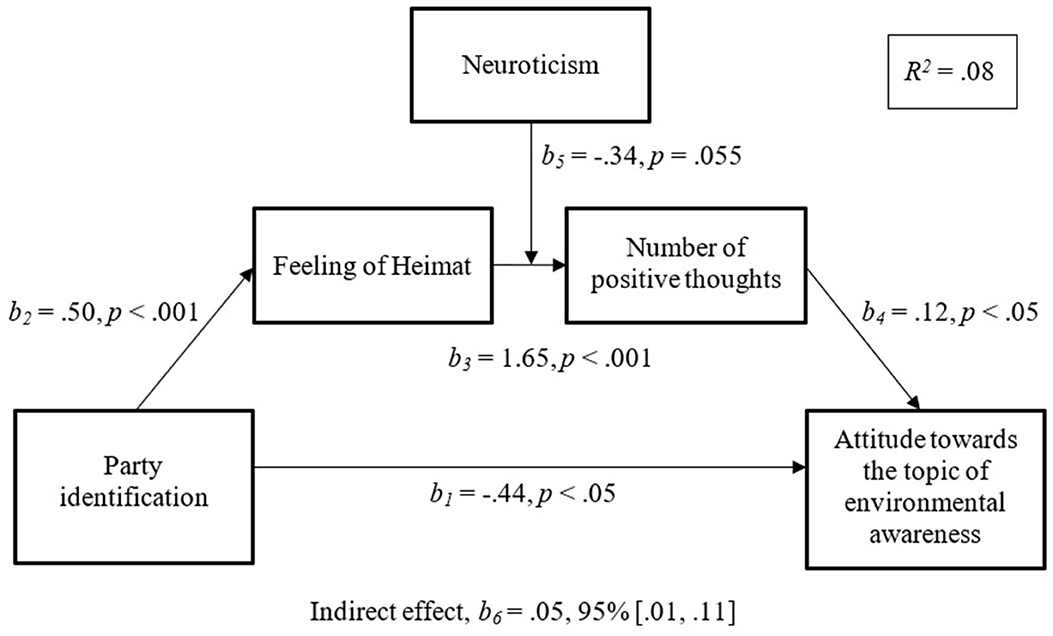

Instead of the original model, these results and considerations thus suggest an indirect effect path from identification with the CSU, which seems to be able to trigger a feeling of Heimat, via the positive thoughts evoked by it, to a corresponding positive effect on attitudes toward the topic of environmental awareness. In the previous analysis, neurotic persons had not shown themselves to be more strongly influenced in their attitudes by a feeling of Heimat. Due to the further plausible assumption of an affinity of neurotic persons for a feeling of Heimat, an influence of this interaction on the resulting positive thoughts was assumed instead. Based on this, a moderated mediation model with two serial mediators (PROCESS model no. 91) was calculated as a post-hoc analysis excluding the persons with minimal party identification (Nnew = 174).4 This new model can be found in Figure 5.

The direct effect of CSU party identification on environmental attitudes was significantly negative (b1 = −0.44, p < 0.05). Looking at the indirect effect, however, there was a positive correlation between party identification and feeling of Heimat (b2 = 0.50, p < 0.001) as well as between feeling of Heimat and the number of positive thoughts (b3 = 1.65, p < 0.001). These were ultimately associated with a more positive environmental attitude (b4 = 0.12, p < 0.05). An interaction between feeling of Heimat and neuroticism could not be confirmed (b5 = −0.34, p = 0.055). Overall, there was a significant indirect effect in the data [b6 = 0.05, 95% (0.01, 0.11)].

7 Discussion and conclusion

Overall, a connection between Heimat reference, feeling of Heimat and the attitude toward the topic of a political advertisement, originally modeled as a mediation, could not be confirmed based on the available data. A reference to Heimat on a purely literal level, in this case manipulated by the slogan of the election poster, does not seem to be sufficient to trigger a desired emotional reaction on the part of the recipients. A slogan without reference to Heimat was even better received by the recipients on the topic of facade greening. This can be interpreted as an indication that Heimat does not seem to function as a kind of “universal address” for all insecure voter groups. Particularly with regard to the almost inflationary use in past election campaigns (cf. e.g., the collection of political slogans already mentioned at the beginning of this article in Schramm and Liebers, 2019), this should give parties food for thought in the future.

At the same time, a positive influence of the feeling of Heimat on the attitude was at least partially confirmed. This, in turn, can be seen as a tentative confirmation of the assumption of an emotional component as the center of the construct of Heimat. However, as the subsequent analysis showed, it was not the content-related reference but another aspect that was much more important for the evocation of such a feeling of Heimat: the CSU party and the political-ideological constructs associated with it seem to be responsible for the emotional reaction among its supporters. In other words, the extent of party identification—independent of the manipulated poster version—was decisive for the strength of the perceived sense of Heimat among potential voters. The more strongly a person was inclined toward the CSU, the more negative the environmental attitude was in the present study.5 However, the feeling of Heimat and the positive thoughts associated with it were in turn able to indirectly influence the environmental attitude positively. It can be concluded that many people closely associate the CSU with Heimat—an association that was presumably intended (cf. the analysis on the use of the concept of Heimat by political parties by Reusswig, 2019). It is precisely this positioning that is likely to be far more important in the election campaign than occasionally sprinkling appeals à la “For the sake of our Heimat” into advertising material. Summing up, the intuitive use of a supposedly emotionally strong term in a literal sense, as currently done by many parties in Germany, does not seem to pay off as intended. Whether the experience of a feeling of Heimat is too complex or the general use of supposedly emotionalizing slogans should be reconsidered opens an interesting field of research. However, based on this pioneering study, it seems to be much more important to create identification potential for voters in such a way that they feel at home and accepted. This is a much more difficult, long-term task, which future research should explore in terms of ways and means. The study also contributes to the area of the influence of emotional experience on persuasion processes. As described in the theoretical section, a feeling of Heimat can be triggered by a wide variety of aspects and is therefore a highly subjective form of affective experience. Nevertheless, the evocation of feelings of Heimat by advertisers certainly seems to pay off: Irrespective of the origin, the post-hoc analysis showed that positive associations and thoughts can be effectively evoked, which have a direct positive effect on attitudes toward a topic. The mechanism for the persuasive influence of feelings of Heimat therefore seems to be a rather indirect one. In view of the direct negative effect of party identification on attitudes toward the topic, the instrumentalization of feelings of Heimat could be particularly useful for topics that seem to be less relevant to the party's usual canon of topics: Conveying a homely feeling of emotional security and safety could become a key component in the political discourse in times of declining trust in parties and institutions and the rise of radical political forces, and should therefore urgently be researched more intensively.

However, it must also be noted at this point that a further shift in political discourse toward a centering around the concept of Heimat by all parties could lead to a cultivation of the party-Heimat connection (for the cultivation approach see e.g., Gerbner et al., 1980) in the perspective of the recipients, which could lead to a kind of desensitization to such persuasive appeals. Especially in view of the fact that such Heimat appeals are not limited to the political sphere but have also found their way into other areas of persuasive communication (for commercial product advertising, see e.g., Mayer et al., 2023), Heimat profiles could, in extreme cases, no longer offer any potential for differentiation in the future. Further advertising developments must be awaited in order to make an assessment in this regard.

Of course, a critical reflection must be made at this point: The originally modeled assumptions had to be almost completely discarded. As described above, the manipulation of information processing also failed. The model that is ultimately relevant and can also be proven statistically is a conclusion from partly hypothesis-contradictory results of the primary analysis, whereby this can only be assumed for one of two operationalizations of the dependent variable. The theoretically plausible but absent effect of personality remains in this second model and should stimulate further research. The relatively small convenience sample used for this study is not representative of the electorate and should therefore be interpreted with care. Especially as the CSU is a rather conservative party, the potentially highly relevant target groups besides younger, highly educated females is strongly underrepresented. Especially aspects such as the level of education of the recipients could in itself influence the way different information processing strategies lead to their specific effect or might in reality—independent from any experimental manipulation—even determine the way in which the political information is processed. Investigating such effects would require a more balanced sample in terms of education, which is why we strongly encourage future research in this area. But as this is the first study to empirically investigate the role of “Heimat” in political advertising respectively as party image profile, future research can nevertheless build on the present findings.

In addition, the question of the role of party identification in a changing political world comes to the fore: even if its importance is said by some to be in continuous decline (e.g., Arzheimer, 2006), party identification proved to be an important factor in the present study. The question of the extent to which other parties, which are not only regionally electable like the CSU in Bavaria, can play a similar explanatory role is also left to further research.

Moreover, empirical research on the effect of Heimat and the feeling of Heimat in a persuasive context is still quite new. The assumptions of the present study are based on definitions and operationalizations that present feelings of Heimat as a clearly positively valenced emotion. That this assumption might not be entirely unproblematic against the background of different contexts is shown, for example, in the contributions by Mitzscherlich (2016) on the topic of loss of Heimat or the contribution by Ludewig (2019), who also associates with Heimat the “loss of a time idealized from a historical distance” (p. 281, translation added). Nevertheless—and this was shown regardless of the unsuccessful manipulation—the feeling of Heimat was able to evoke positive thoughts on the part of the recipients in every condition.

Overall, the present study can also be seen as a starting point for examining the emergence of a feeling of Heimat beyond content-related slogans: Musically speaking, Mendívil (2008) calls the German Schlager a “bearer of the longing for Heimat” (p. 277, translation added), while on a visual level certain landscape images are often closely linked to Heimat (Weber et al., 2019). Last but not least, the development of the term Heimat over time described at the beginning is far from having reached its end. Younger generations, for example, now seem to have found a Heimat in the digital world (e.g., Lutz and Fußmann, 2014). The coronavirus pandemic and the associated restrictions on freedom of movement may also have led to a reduction in the perceived living space of many people and an associated return to their local Heimat. The Russian war of aggression on Ukraine and its consequences for the rest of Europe could also be perceived as an acute threat to this Heimat. The extent to which these developments shape the concept—possibly even sustainably—is an interesting field of future research.

Ultimately, the present study shows that Heimat as a party profile can certainly function in a political context. Nevertheless, the possibilities of instrumentalization are complex and the desired emotional effect is not self-evident. Parties should strive to offer their voters a form of Heimat: Those who feel picked up, safe and secure seem to transfer positive thoughts in this regard to political content. The CSU seems to have achieved this to some extent—at least for those who sympathize with them.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the studies involving humans because in Germany, there is no legal obligation to have every study cleared by an Ethics Committee and it is scientific common practice to only do this, if any harm concerning participants is expectable. In this study, as is obvious by the measurements section in this paper, no such harm was to expect, which is why we waived the approval. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

FM: Writing – original draft. HS: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This publication was supported by the Open Access Publication Fund of the University of Würzburg.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^“Heimat” translates directly into “home” but stands for more (cf. Schröter, 2016). Due to a lack of an equivalent concept in English and in line with Ratter and Gee (2012), the German term “Heimat” is used throughout the article as was practiced by previous research on the concept in the media context (e.g., Schramm et al., 2022a).

2. ^Emotions can be understood as brief, intense affective sensations with a clear cause (Forgas, 1992).

3. ^Due to the fact that the processing mechanisms could not be proven on the basis of the data as intended, the corresponding groups for information processing could not be assumed either. Since these could therefore not be interpreted and no effects were found for the hypothesis evaluation, a detailed presentation of the statistical values for the four models is omitted for the sake of readability.

4. ^Such a restriction of the sample was made because in the new modeling, identification with the CSU was assumed to have the potential to trigger a feeling of Heimat. Persons without any identification with the CSU were thus not relevant for further consideration.

5. ^Whether this is actually due to a rejection of the topic or simply because the election poster is perceived as an all to obvious greenwashing attempt can only be surmised in retrospect.

References

Arzheimer, K. (2006). “Dead men walking?” Party identification in Germany, 1977-2002. Elector. Stud. 25, 791–807. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2006.01.004

Bade, K. J. (2018). “Von Unworten zu Untaten: Kulturängste, Populismus und politische Feindbilder in der deutschen Migrations- und Asyldiskussion zwischen ‘Gastarbeiterfrage' und ‘Flüchtlingskrise”' [From Unwords to Misdeeds: Cultural Fears, Populism and Political Enemy Images in the German Migration and Asylum Debate between the ‘Guest Worker Question' and the ‘Refugee Crisis']. Histor. Soc. Res. Suppl. 30, 338–350. doi: 10.12759/hsr.suppl.30.2018.338-350

Balabanis, G., and Diamantopoulos, A. (2004). Domestic country bias, country-of-origin effects, and consumer ethnocentrism: a multidimensional unfolding approach. J. Acad. Market. Sci. 32, 80–95. doi: 10.1177/0092070303257644

Bartels, L. M. (2002). Beyond the running tally: partisan bias in political perceptions. Polit. Behav. 24, 117–150. doi: 10.1023/A:1021226224601

Berenbaum, H., Bredemeier, K., and Thompson, R. J. (2008). Intolerance of uncertainty: exploring its dimensionality and associations with need for cognitive closure, psychopathology, and personality. J. Anxiety Disord. 22, 117–125. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.01.004

Bernhardt, S. (2019). Buy green, buy better - Beeinflusst Umweltbewusstsein und Verlangen nach Status die Wahrnehmung von Greenwashing in der Werbung und die Kaufintention grüner Produkte? [Buy Green, Buy Better - Do Environmental Awareness and Desire for Status Influence the Perception of Greenwashing in Advertising and the Purchase Intention of Green Products?], (Master's thesis), University of Wuerzburg, Wuerzburg, Germany.

Brader, T. (2005). Striking a responsive chord: how political ads motivate and persuade voters by appealing to emotions. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 49, 388–405. doi: 10.1111/j.0092-5853.2005.00130.x

Breves, P., Liebers, N., and Schramm, H. (2022). “The impact of spatiotemporal and sociocultural heimat associations in entertaining media on social identity, individual well-being, and intergroup relations”, in Presentation at the 72nd Annual Meeting of the International Communication Association (ICA). Paris.

Cacioppo, J. T., and Petty, R. E. (1981). “Social psychological procedures for cognitive response assessment: the thought-listing technique”, in Cognitive Assessment, eds. T. V. Merluzzi, C. R. Glass, and M. Genest (New York, NY: The Guilford Press), 309–342.

Campbell, A., Converse, P. E., Miller, W. E., and Stokes, E. D. (1960). The American Voter. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Cohen, G. L. (2003). Party over policy: the dominating impact of group influence on political beliefs. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 85, 808–822. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.5.808

CSU district association Wuerzburg (2020). Programm der CSU zur Kommunalwahl in Würzburg am 15. März 2020 für die kommende Wahlperiode 2020-2026 [Program of the CSU for the local elections in Würzburg on March 15, 2020 for the upcoming election period 2020-2026]. Available online at: https://www.csu.de/common/csu/content/csu/hauptnavigation/verbaende/kreisverbaende/wuerzburg-land/Kommunalwahl2020/CSU-Programm_proof4.pdf (accessed March 15, 2020).

Debus, M., and Faas, T. (2019). Die hessische Landtagswahl vom 28. Oktober 2018: Fortsetzung der schwarz-grünen Wunschehe mit starken Grünen und schwacher CDU [The Hessian state election of 28 October 2018: continuation of the black-green desire marriage with strong Greens and weak CDU]. ZParl Zeitschrift für Parlamentsfragen 50, 245–262. doi: 10.5771/0340-1758-2019-2-245

Ellen, P. S., Wiener, J. L., and Cobb-Walgren, C. (1991). The role of perceived consumer effectiveness in motivating environmentally conscious behaviors. J. Publ. Pol. Market. 10, 102–117. doi: 10.1177/074391569101000206

Forgas, J. P. (1992). Affect in social judgments and decisions: a multiprocess model. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 25, 227–275. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60285-3

Forgas, J. P. (1995). Mood and judgment: the affect infusion model (AIM). Psychol. Bullet. 117, 39–66. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.117.1.39

Franke, N., Ratter, B. M. W., and Treiling, T. (2009). Heimat und Regionalentwicklung an Mosel, Rhein und Nahe. Empirische Studien zur Regionalen Identität in Rheinland-Pfalz [Heimat und Regional Development at Mosel, Rhein and Nahe. Empirical Studies on Regional Identity in Rhineland-Palatinate]. Mainz: Institute of Geography of the Johannes-Guttenberg-University Mainz.

Gallego, A., and Pardos-Prado, S. (2014). The big five personality traits and attitudes towards immigrants. J. Ethnic Migrat. Stud. 40, 79–99. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2013.826131

Gerber, A. S., Huber, G. A., Doherty, D., Dowling, C. M., and Ha, S. E. (2010). Personality and political attitudes: relationships across issue domains and political contexts. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 104, 111–133. doi: 10.1017/S0003055410000031

Gerbner, G., Gross, L., Morgan, M., and Signorielli, N. (1980). The “mainstreaming” of America: violence profile number 11. J. Commun. 30, 10–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.1980.tb01987.x

Gluchowski, P. (1983). “Wahlerfahrung und Parteiidentifikation. Zur Einbindung von Wählern in das Parteiensystem der Bundesrepublik [Electoral Experience and Party Identification. On the involvement of voters in the party system of the Federal Republic of Germany]”, in Wahlen und politisches System. Analysen aus Anlaß der Elections and the political system [Elections and the political system. Analyses on the occasion of the 1980 Bundestag election], eds. M. Kaase and H.-D. Klingemann (Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag GmbH), 442-477.

Goldberg, L. R. (1993). The structure of phenotypic personality traits. Am. Psychol. 48, 26–34. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.48.1.26

Hammer, D. (2017). “My Heimat is my castle-Rechtspopulistische Heimatbegriffe [My Heimat is my castle—Right-wing populist concepts of homeland]”, in Heimat finden—Heimat erfinden. Politisch-philosophische Perspektiven [Finding Heimat - inventing Heimat. Political-philosophical perspectives], eds. U. Hemel and J. Manemann (Paderborn: Wilhelm Fink Verlag), 61–77.

Hawkins, C. B., and Nosek, B. A. (2012). Motivated independence? Implicit party identity predicts political judgments among self-proclaimed independents. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bullet. 38, 1437–1452. doi: 10.1177/0146167212452313

Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to Mediation, Moderation and Conditional Process Analyses. A Regression-Based Approach, 2nd Edn. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Heller, W., and Narr, W.-D. (2011). Heimat - zu Verwendungen dieses Begriffs [Home - on uses of this term]. Geographische Revue 13, 11–28.

Hilmer, R., and Gagné, J. (2018). Die Bundestagswahl 2017: GroKo IV - ohne Alternative für Deutschland [The Bundestag Election 2017: GroKo IV - without Alternative für Deutschland]. ZParl Zeitschrift für Parlamentsfragen 49, 372–406. doi: 10.5771/0340-1758-2018-2-372

Hirsh, J. B., and Inzlicht, M. (2008). The devil you know: neuroticism predicts neural response to uncertainty. Psychol. Sci. 19, 962–967. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02183.x

Huddy, L., and Gunnthorsdottir, A. H. (2000). The persuasive effects of emotive visual imagery: superficial manipulation or the product of passionate reason? Polit. Psychol. 21, 745–778. doi: 10.1111/0162-895X.00215

Kaid, L. L., and Holtz-Bacha, C. (1993). Audience reactions to televised political programs: an experimental study of the 1990 German national election. Eur. J. Commun. 8, 77–99. doi: 10.1177/0267323193008001004

Klose, J. (2013). “Heimat' als gelingende Ordnungskonstruktion ['Heimat' as a successful construction of order]”, in Die Machbarkeit politischer Ordnung. Transzendenz und Konstruktion [The feasibility of political order. Transcendence and construction], ed. W. J. Patzelt (Bielefeld: transcript Verlag), 391–415.

Knoll, J. (2015). Persuasion in sozialen Medien. Der Einfluss nutzergenerierter Inhalte auf die Rezeption und Wirkung von Onlinewerbung [Persuasion in Social Media. The Influence of User-Generated Content on the Reception and Impact of Online Advertising]. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Kollmann, T., and Schmidt, H. (2016). Deutschland 4.0. Wie die Digitale Transformation gelingt [Germany 4.0. How the Digital Transformation Succeeds]. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien.

Korte, K. R. (2016). Flüchtlinge verändern unsere Demokratie [Refugees change our democracy]. Zeitschrift für Politikwissenschaft. 26, 87–94. doi: 10.1007/s41358-016-0024-5

Kroh, M. (2020). “Parteiidentifikation: Konzeptionelle Debatten und empirische Befunde [Party identification: Conceptual debates and empirical findings]”, in Politikwissenschaftliche Einstellungs- und Verhaltensforschung. Handbuch für Wissenschaft und Studium [Political science attitude and behavior research. Handbook for science and studies], eds. T. Faas, O. W. Gabriel, and J. Maier (Baden-Baden: Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft), 458–479.

Kühne, O., and Spellerberg, A. (2010). Heimat in Zeiten erhöhter Flexibilitätsanforderungen. Empirische Studien im Saarland [Home in times of increased flexibility demands. Empirical studies in Saarland]. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Kühne, R., Wirth, W., and Müller, S. (2012). Der Einfluss von Stimmungen auf die Nachrichtenrezeption und Meinungsbildung: Eine experimentelle Überprüfung des Affect Infusion Models [The influence of moods on news reception and opinion formation: an experimental test of the affect infusion model]. Medien Kommunikationswissenschaft 60, 414–431. doi: 10.5771/1615-634x-2012-3-414

Lang, F. R., Lüdtke, O., and Asendorpf, J. B. (2001). Testgüte und psychometrische Äquivalenz der deutschen Version des Big Five Inventory (BFI) bei jungen, mittelalten und alten Erwachsenen [Test performance and psychometric equivalence of the German version of the Big Five Inventory (BFI) in young, middle-aged and old adults]. Diagnostica 47, 111–121. doi: 10.1026//0012-1924.47.3.111

Lessenich, S., Przybilla-Voß, M., Klatt, J., and Rolfes, L. (2019). ‘Heimat lässt sich nur in einem sozialen Zusammenhang denken' Ein Gespräch mit Stephan Lessenich über den Heimatbegriff, Umweltschutz und das Unheimliche ['Heimat can only be thought of in a social context' A conversation with Stephan Lessenich on the concept of Heimat, environmental protection and the uncanny]. Indes 7, 7–18. doi: 10.13109/inde.2018.7.4.7

Lessinger, E.-M., and Holtz-Bacha, C. (2019). “Nicht von gestern. Die Parteienplakate im Bundestagswahlkampf 2017 [Not from yesterday. The party posters in the 2017 federal election campaign]”, in Die (Massen-) Medien im Wahlkampf. Die Bundestagswahl 2017 [The (mass) media in the election campaign. The 2017 federal election], ed. C. Holtz-Bacha (Wiesbaden: Springer VS), 125–164.

Ludewig, A. (2008). ‘Heimat, Heimat, über alles': Heimat in two contemporary German films. Stud. Eur. Cinema 5, 219–232. doi: 10.1386/seci.5.3.219_1

Ludewig, A. (2019). “Ostalgie im Dresdner Tatort (2016/2017) [Ostalgie in the Dresden Tatort (2016/2017)]”, in Heimat. Ein vielfältiges Konstrukt [Heimat. A multifaceted construct], eds. M. Hülz, O. Kühne, and F. Weber (Wiesbaden: Springer VS), 279–297.

Lutz, K., and Fußmann, A. (2014). Im Universum zuhause [At home in the universe]. Merz - medien+erziehung 58, 7–11.

Matthes, J., and Marquart, F. (2013). Werbung auf niedrigem Niveau? Die Wirkung negativ-emotionalisierender politischer Werbung auf Einstellungen gegenüber Ausländern [Advertising at a low level? The effect of negative-emotionalizing political advertising on attitudes towards foreigners]. Publizistik 58, 247–266. doi: 10.1007/s11616-013-0182-0

Mayer, F., Taupert, N., and Schramm, H. (2023). “Kann man Heimat (ver)kaufen? Zur Wirkung von Heimatbezügen und Unternehmen-Heimat-Fit in der kommerziellen Werbekommunikation auf persuasive Effekte [Can Heimat be bought? On the impact of Heimat references and company-Heimat fit in commercial advertising communication on persuasive effects]”, in Presentation at the Annual Meeting of DGPuK-Devision for Advertising Communication. Würzburg.

Mendívil, J. (2008). Ein musikalisches Stück Heimat. Ethnologische Beobachtungen zum deutschen Schlager [A musical piece of home. Ethnological observations on the German Schlager]. Bielefeld: transcript Verlag.

Miller, W. E., and Shanks, J. M. (1996). The New American Voter. Cambridge, MA: Havard University Press.

Mitzscherlich, B. (2000). Heimat ist etwas, was ich mache. Eine psychologische Untersuchung zum individuellen Prozess von Beheimatung (2. Auflage) ['Heimat is something I do'. A psychological study on the individual process of homecoming]. Herbolzheim: Centaurus Verlag.

Mitzscherlich, B. (2014). “Zur Psychologie von Heimat und Beheimatung—eignet sich Heimat als Thema der Umweltbildung? [On the psychology of Heimat and being at home—is Heimat suitable as a topic for environmental education?]”, in Vom Sinn der Heimat. Bindung, Wandel, Verlust, Gestaltung—Hintergründe für die Bildungsarbeit [The meaning of Heimat. Attachment, change, loss, design - background for educational work], eds. N. Jung, H. Molitor, and A. Schilling (Berlin: Budrich Uni-Press), 35–45.

Mitzscherlich, B. (2016). Heimatverlust und -wiedergewinn: Psychologische Grundlagen [Losing and regaining one's Heimat: psychological foundations]. Leidfaden 5, 4–13. doi: 10.13109/leid.2016.5.3.4