95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Commun. , 12 March 2024

Sec. Health Communication

Volume 9 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2024.1296296

This article is part of the Research Topic Insights in Health Communication: 2022-2025 View all 6 articles

People are increasingly turning to social media platforms to acquire information and seek advice on health matters. Consequently, a growing number of qualified healthcare professionals are using social media as channels for public health communication. On platforms such as YouTube and Instagram, health workers can reach a wide and interested audience while applying powerful tools for presentation and interaction. However, such platforms also represent certain challenges and dilemmas when doctors and psychologists become health influencers. Who do they represent? What style of communication is expected? And what responsibilities do they have toward their followers? The present study contributes to the field of investigation by employing qualitative methods. It is based on three focus group interviews conducted with students enrolled in health-related study programmes at Norwegian universities. The paper asks: How do future healthcare workers perceive the social media practices of popular healthcare experts regarding the advantages and dilemmas associated with such practices?

People are increasingly turning to social media platforms to acquire information and seek advice on health matters (Chen and Wang, 2021). Consequently, a growing number of qualified healthcare professionals are using social media as channels for public health communication (Campbell et al., 2016). Throughout the course of the pandemic, the use of platforms such as Instagram, YouTube, Facebook, and Twitter as arenas for authoritative health information, as well as various forms of health-related misinformation, increased substantially (Suarez-Lledo and Alvarez-Galvez, 2021). Today, many healthcare professionals have attained popularity as media personalities, using their platforms to share details of their private lives with their followers in parallel to providing reliable and evidence-based health guidance. While some derive their livelihood solely from activities associated with their social media presence, others function as “health influencers”1 alongside their primary roles as hospital physicians, psychologists, or public health nurses. Given that these actors represent novel and popular avenues for health communication, it becomes imperative to address urgent questions regarding the effectiveness and social implications of their media practices. Do they improve public health? Are they the new first-line service? Or do they make their followers oversensitive to normal challenges, or even sully the reputation of health sciences? The present study suggests that social media platforms provide unique opportunities for healthcare professionals to disseminate authoritative health advice to a broad audience. However, the study also indicates that being a public health advisor on social media does not appear particularly attractive to future healthcare workers.

There is increasing scholarly interest in the use of social media platforms by qualified healthcare professionals and health organizations (Martini et al., 2018; Basch et al., 2021; Chen and Wang, 2021). Much of the existing research in this domain employs quantitative methodologies, which uncover broad patterns in the evolution of mediated health communication (Chen and Wang, 2021). The present study contributes to the field employing qualitative methods. It is based on three focus group interviews conducted with students enrolled in health-related study programmes at Norwegian universities. The paper asks: How do future healthcare workers perceive the social media practices of popular healthcare experts regarding the advantages and dilemmas associated with such practices?2 The objective of the study is to add depth and nuances to a field of research dominated by quantitative studies, allowing the voices of future healthcare workers to be heard. Today's students of health sciences will assumably have a considerable impact on the future development of public health communication. They are also qualified critics of the practices in question. Therefore, their voices are of special interest, yet largely absent from the existing body of research. The results of the study will be useful to students and researchers in the media and health sciences, as well as for practitioners and policy makers operating within this domain.

The article is structured into four main sections. First, it provides a narrative review of previous research conducted in this field of investigation. Second, the methodological and theoretical frameworks employed in the study are explained. In the third section, the interview data is analyzed. Engagement, trust, and social roles are key concepts in the analysis. In the fourth and final section, the findings are summarized, discussed, and concluded.

Social media have long been regarded as a promising arena for science communication and dissemination of knowledge. According to Davies and Hara (2017, p. 564), digital and social media have the potentials to “open up science, enable dialogue, and create a digital public sphere of engagement and debate.” These media affordances also apply to health communication. Research has revealed that social media represent opportunities to increase self-efficacy, treatment adherence, and health literacy, when used actively by health professionals to spread health information and advice (Suarez-Lledo and Alvarez-Galvez, 2021). However, these channels also work as arenas for health-related misinformation, understood as “a health-related claim that is based on anecdotal evidence, false or misleading owing to the lack of existing scientific knowledge” (Suarez-Lledo and Alvarez-Galvez, 2021, p. 2). That is one of the reasons why Gabarron et al. (2020, p. 127) state that healthcare professionals and public health institutions need to have a greater presence on social media: “They have the potential for interacting with individuals, delivering trustworthy information, correcting misinformation, and providing the correct responses to personal and public concerns.”

A literature review of 158 relevant studies concluded that “using SM [social media] could be a key strategy in addressing some of the challenges and limitations often faced by HCPs [health care providers] in traditional health communication through faster and cheaper dissemination, more accessibility, better interaction, and increased patient empowerment” (Farsi, 2021, p. 6).

As a channel for qualified health information and advice, social media represent a new arena, and guidelines from public health authorities are rare (Gabarron et al., 2020; Farsi et al., 2022). However, research indicates that certain strategies work better than others in terms of evoking engagement among internet users. The use of video (Kite et al., 2016; Martini et al., 2018), personal stories, humor, and two-way communication (Steffens et al., 2020; Basch et al., 2021), are all elements that have been shown to evoke followers' attention and engagement. Although social media's opportunities for dialogue and interaction are regarded by some commentators as the “gold mine” for health workers who want to reach young internet users (Yonker et al., 2015, p. 8), many health experts use these media merely as a one-way channel for the dissemination of information (Campbell et al., 2016). Such a one-way approach to a typical two-way social arena may be motivated by several factors, such as the time demanded for staying connected and the risk of privacy breach (cf. Farsi, 2021).

While social media offer unique opportunities for health communication in the digital public, they also represent several challenges, risks, and dilemmas. One challenge is to find the right balance between pedagogical simplification and scientific quality. In all forms of public communication of scientific content, the issue of understandability is key (cf. Bauer, 2009). And social media offer unique affordances regarding educationally tailored, visual and multimodal presentations of health-related content (Moreno and D'Angelo, 2019). On the other hand, too strong simplification and generalization may blur important nuances and even lead to a banalization of the subject topic.

Another challenge lies in establishing an online identity that effectively combines the role of a trusted and personal advisor with that of a professional health authority. One approach is to adopt the style employed by popular lifestyle or fashion influencers. This style typically involves the sharing of personal details (Torjesen, 2021), potentially fostering both emotional engagement and a sense of confidentiality and trust with followers. However, such a stylistic choice can clash with the expectation of objectivity and discretion associated with a professional healthcare provider (Ferrell and Campos-Castillo, 2022). The existing literature does not provide a definitive answer on the most effective means of building trust on social media (ibid.). Some commentators suggest that many people, particularly young people, tend to place greater trust in their friends and other approachable individuals than in experts (Yonker et al., 2015; Jenkins et al., 2020). Conversely, others argue that trust can be established through the inclusion of credible sources and an emphasis on the reliability of the information conveyed (Fontaine et al., 2019).

The above-mentioned challenges of evoking engagement and building trust are related to a potential conflict of norms. This conflict comes to surface when institutionalized conventions regulating the behavior of professional health workers meet the open and sharing culture of social networks (Munson et al., 2013; Ferrell and Campos-Castillo, 2022; Atef et al., 2023). They are also related to the fact that the health-related information and advice offered on social media platforms are most often aimed at a wide audience (Farsi et al., 2022). When targeting a wide media audience, it can be challenging to find topics and a style of discourse that fits all, as well as to construct a sender identity and a social relation that evokes engagement and trust in all parts of the audience. Farsi (2021, p. 7) write: “Messages tailored to certain population segments are more effective than generic messages, as tailored messages address the specific needs of their recipients.”

Thus, research in the field has revealed that the transition of health information from leaflets, school visits, and magazine columns to YouTube, Instagram, and TikTok implies both new opportunities and new challenges. What is lacking in the literature are qualitative investigations on how specific segments of users experience and value the work done by health experts on social media. The present study is a response to this lacuna in our shared knowledge on health and the media.

The study is based on three focus group interviews, each group consisting of five to six students enrolled in health-related study programmes at Norwegian universities. The study programmes included are medicine, psychology, and public health nursing (a 1-year further education programme for nurses). Employing a qualitative design, the study aims to uncover the experiences, attitudes, and reflections expressed by members of this specific segment of the media audience. The findings are not representative of a large and diverse population. Nevertheless, the study provides insights and nuanced perspectives on how a particular group of recipients responds to a new genre of health communication and how these responses manifest verbally. The article supports its findings by presenting extracts from transcribed interviews, documenting, and illustrating the results. This form of explorative, qualitative research contributes to future surveys that aim to identify patterns and trends within larger populations.

The interview guide was developed based on previous research in the relevant field (see the previous section) and relevant concepts from two disciplines: science communication and social semiotics. In the literature on science communication, three key factors for such communication to be successful are identified: understandability, emotional engagement, and trust (Bauer, 2009). All these aspects of communication are reflected in the interview guide. In the theoretical field of social semiotics, the focus is on the process of meaning-making in social settings, including the interpersonal aspect of communication. According to Van Leeuwen (2022), the shaping and negotiation of identities and social roles are fundamental processes in all instances of human communication. These processes are particularly relevant for this study, as they contribute to establishing the social status of the communicating individuals and the trustworthiness attributed to the exchanged messages.

Van Leeuwen (2022) distinguishes four types of identity: social identity, which positions individuals within specific social groups; individual identity, which signifies unique qualities and characteristics of a person; role identity, which indicates the various social or professional roles a person may have in different situations; and lifestyle identity, which connects a person to particular values and interests based on leisure activities and consumption patterns. These categories of identity are applicable to both the sender and the receiver of mediated messages. In the present study, they are useful in analyzing and discussing the results from the focus group interviews.

Students enrolled in health-related study programmes were specifically chosen for their possession of three key characteristics: (a) being relevant recipients of the media content, (b) possessing the qualifications to critically analyse the content, and (c) having the potential to become recruits for the type of media practice being examined. The interviews were coordinated and carried out by staff members of Medlytic, a Norwegian company specializing in supporting health-related research. They undertook this task based on the detailed instructions and interview guide provided by the author of this article.3

In the process of recruiting participants to the focus groups, Medlytic staff used social media announcements. They also reached out to personal networks within the student population. All participants were enrolled in study programmes at various Norwegian universities. The author of this article decided the number of participants in each focus group, and what study programmes the participants in each group should be recruited from: study programmes in medicine, psychology, and health nursing, respectively. As a token of gratitude for their time and participation, the informants received a small gift card. To conduct the interviews, Medlytic staff used the video conferencing software Zoom, allowing digital interaction. Each of the three interviews had a duration of approximately one to one and a half hours, the participants sitting in different locations in Norway. All interview sessions were recorded on video and subsequently anonymised and transcribed. The author of this article, not being present during the Zoom sessions, received the anonymised transcriptions once they were completed. Staff members from Medlytic have not taken any part in the analysis of the interviews or in the writing process.

The analysis was carried out in three stages. During the initial stage, all interview transcripts were uploaded to Nvivo software and coded according to a predefined codebook that was developed based on the interview guide and the theoretical framework. In the second stage, both the codebook and the coding were iteratively adjusted by multiple readings of the transcripts. Lastly, in the third stage, the analysis was thematically organized and written with the objective of providing a valid and comprehensive response to the research question. At this stage, the focus was on detecting ideas and perceptions recurring across the three groups as well as variations in the interview data.

Focus group interviews encompass both strengths and weaknesses as a research methodology (see, e.g., Powell and Single, 1996). One advantage lies in the group dynamics, which facilitate the emergence of diverse ideas and foster discussion, including the introduction of contrasting viewpoints. Furthermore, the inclusion of a larger number of participants allows for a comprehensive data collection in a relatively short time frame. Powell and Single (1996, p. 504) write: “The focus group is an ideal means of generating hypotheses, of investigating unexplored areas of human experience and of clarifying ambiguous ones.” However, there are also drawbacks to consider. Participants may self-censor due to concerns about potential social stigma within the group, hindering the full expression of their thoughts and opinions. Additionally, there is a risk that more extroverted or dominant participants might overshadow the contributions of quieter participants. To address these concerns, it is crucial that the moderator extracts relevant information from all participants while safeguarding the integrity of the individual informant. In the present study, a professional moderator was appointed to lead all three interviews, based on the instructions and interview guide provided by the author of this article. While this delegation of tasks may have strengthened the flow of information in the interview sessions, it also represents limitations regarding the follow-up questions that were raised, and the amount of time allocated to each theme. An additional limitation of the study is the gender imbalance among informants, 16 out of 17 participants being women. This imbalance is a consequence of the recruitment process, while also reflecting the existing gender disparity in health-related study programmes in Norway.4 Although it remains uncertain whether a more balanced group of informants would have yielded significantly different results, this gender distribution should be recognized. Regarding the reliability of the results, it should be recognized that another researcher might have emphasized and presented the findings in the interview data differently, not least since the analysis in this case was carried out by a single researcher. This hermeneutic aspect of qualitative research makes complete replicability unattainable. It highlights the need for transparency regarding the implementation of the research and awareness regarding its limitations.

The study adheres to the prevailing academic standards of research ethics and has obtained approval from the Norwegian Center for Research Data (NSD).

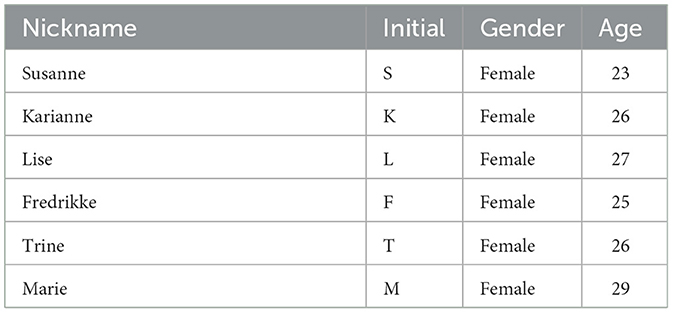

The three focus groups consisted of individuals referred to by their chosen nicknames, as listed below (see Tables 1–3).

Table 3. Group 3—Students studying public health nursing (the public health nursing programme is a 1-year continuing education programme for nurses).

During the recruitment stage, candidates received information on the general theme of the interview. They were instructed to prepare by familiarizing themselves with a selection of relevant social media accounts, which are run by a hospital doctor, a psychologist, and a public health nurse, respectively.5 Many of the participants already knew one or more of these accounts, as well as similar accounts run by other health experts. Consequently, the responses given during the interviews should not be interpreted solely as reactions to the three specific accounts mentioned, but rather as reflections on the broader phenomenon of health experts providing information and advice on social media.

The analysis reveals that the study participants generally perceive the health experts' activities on social media as a positive and beneficial practice. They appreciate their role in increasing visibility and normalizing discussions surrounding health issues, as well as raising awareness about health matters. However, they also highlighted certain areas of uncertainty and risk connected to these forms of media practice. None of the participants expressed aspirations to engage in this kind of practice themselves (see Table 4) .

A central finding of the study is that the participants perceive the relational aspect as a crucial factor in the activities of healthcare professionals on social media. According to the literature on science communication (Bauer, 2009; Davies and Horst, 2016), building social connections provides opportunities for emotional engagement and facilitates effective dissemination of academic content. The informants also acknowledge and appreciate the efforts of experts to simplify complex topics. However, in their view, both endeavors come with associated costs. Therefore, one key conclusion drawn from the interviews is that the success and effectiveness of such media activities by professional health workers hinge on their ability to strike a delicate balance between two basic, yet potentially conflicting, aims: being comprehensible while maintaining scientific accuracy; and fostering social connections while upholding professional standards.

In the following analysis of the interview data, key findings, and selected citations underpinning them, are organized in three sections, each presenting the informants' view on the following topics: the dissemination of content to a wide audience; the stimulation of the followers' engagement and trust, and the likelihood that they themselves will take on a role as health influencers.

Examples of key questions and responses are found in Table 4 below, followed by a more detailed presentation of the results.

The informants are generally of the opinion that qualified health influencers have a considerable ability to reach a large audience with health advice that is understandable and useful to many. Nina (medicine student) believes that the most popular health influencers have “cracked a code” that the public health authorities have not yet managed. She said6:

The public authorities are probably thinking about how they can achieve something similar, reach out to people. They have maybe not cracked that code themselves, then.

However, some of the informants highlight potential problems that may arise from targeting a broad audience. When a health expert delves deeply into a narrow and specialized topic, many of their followers can feel excluded. On the other hand, if the expert alternates between very disparate types of information or advice, it can confuse followers regarding whether they belong to the intended target group or not. Among the informants, there are various opinions about the types of topics that work well or not so well on social media accounts with a broad and heterogeneous audience. Some say that such accounts should focus on promoting good health and general wellbeing, while refraining from providing detailed descriptions and advice related to severe health conditions. Others say that it can be a support for people who suffer from serious conditions to hear about others who go through the same.

Ingvild (psychology student) said:

I think anything that promotes good health that is presented on Instagram or elsewhere is a good thing. Everything that is preventive, that explains how our body and mind work, is good. What I think there should be less of, is all the talk about serious illnesses and symptoms. (..) What do we gain from talking a lot about anxiety, trauma and depression, or people dying from cancer? I don't say that it's all wrong (..) It is not good to be protected from everything evil. (..) But I think promoting good health is more important.

Regarding the challenges related to the pedagogical shaping of professional knowledge to fit a broad audience consisting of non-experts with limited time and interest, the informants unanimously concur on the necessity of simplification. They acknowledge that many health experts on social media are very good at this. However, they also caution against the potential drawbacks of oversimplification. In certain instances, some participants said, it can obscure a reality that is considerably more complex. The concerns expressed by some of the psychology students were particularly focused on the potential pitfalls of providing generalized advice on mental challenges that can be experienced in very diverse ways by different individuals. Additionally, it was emphasized that while straightforward guidance for psychological self-help may prove effective for some individuals, it may not be equally beneficial for everyone, particularly when individuals are solely responsible for implementing the advice in their own lives. And if the advice does not work, it was argued, it can potentially intensify feelings of defeat and despair. Ronja (psychology student) said:

Some may read these simple-looking advice and think, ok, I should use some more time on myself, but they experience that it can be difficult to implement without any further guidance. And it may encourage the idea that this does not help me, I will not be any better.

Many informants highlighted one significant positive impact of health experts engaging with social media: the ability to bring attention to and normalize conditions that are normally not talked about. That is a key reason for the general opinion among the informants that health experts on social media generally contribute to improving public health. Thelma (medicine student) said:

Just a few years ago, no one would ever talk loud about going to a psychologist. And it was unheard of that you should seek professional help if you were struggling with difficult thoughts or those kinds of things. Now, that has become quite normal. Several of my own friends can say, oh, I have to go because I have an appointment with my psychologist. I think that is because some psychologists have started to be more visible on social media, offering their knowledge as well as their opinions. I think that is a really good thing.

On the other hand, several of the informants were concerned about the risk of misinterpretations and self-diagnosis as a result of oversimplification and increased visibility, especially in the context of mental health. They emphasized the challenge of capturing all nuances associated with different mental conditions in a highly simplistic manner, highlighting the likelihood that individuals may too hastily identify specific symptoms within themselves. The need for individualized treatment of mental conditions was emphasized, given the diverse range of causes and symptoms they can encompass. Connie (psychology student) said:

I saw a video reel on Instagram about mental diagnoses. It did not convey the appropriate information about the decline of normal function and levels of symptomatic pressure, which are actually very key criteria for making a diagnosis. It is completely impossible for...even for us, who are students of psychology and have worked in this field for years, we cannot do it right.

Furthermore, informants highlighted the risk of misinterpreting provided information due to the absence of adequate opportunities for follow-up questions or personalized guidance. It was also expressed a concern that something presented with the aim of describing a normal human condition, a condition that most people will recognize, is perceived as a symptom of sickness. Ingvild (psychology student) said:

Everyone will recognise some signs of depression or some signs of anxiety. That does not mean that you are depressed or that you are a person who suffers from anxiety. But many people might think they are, because they lack a deeper understanding of these conditions.

To communicate scientific knowledge effectively to a wide audience, it is essential to evoke a certain level of emotional engagement (cf. Bauer, 2009). The participants recognized the potential for social connection inherent in the role of popular health influencers. Individual experts, showing their faces and revealing personal experience and advice, tend to appear more relatable and approachable compared to an organization or a public health institution. According to Munson et al. (2013), being personal and approachable is a central issue when experts use social media for public health communication. This aspect is crucial in cultivating emotional engagement among followers and, consequently, building a broad and attentive audience (ibid.). Several informants expressed similar ideas. Susanne (public health nursing student) said:

To build a following, those who follow need to feel that they get to know the person behind the account. That is the whole point of being an influencer. That those following you feel that they know you. So, if they behave in a very distanced manner, I doubt that they will create much engagement.

Thus, a key aspect of building a relation with an audience is the construction of a sender identity. A sender identity is based in part on the personality of the communicating individual, but it is also the result of a certain style, i.e., the choices made concerning verbal message, visual appearance, and physical surroundings (Van Leeuwen, 2022). In the case of health influencers, several informants emphasized that health experts on social media need to find the right balance between representing themselves—building a personal brand—and representing a field of scientific knowledge as well as a profession. Several informants, having observed a number of health experts on various social media platforms, talked about substantial variations concerning their choices of style. Some have a very informal and personal style in their posts, sharing their personal experiences and opinions about current controversies, while others have a more objective and formal style. The informants reported that some health influencers reveal an intention to build social relationships, while others focus more exclusively on scientific matters. Which strategy is more effective is a question without a clear answer in the three groups of participants. Marie (public health nursing student) said:

When it comes to sharing their own experiences, for example, talking about what worked well for themselves.. I guess that will be useful for some of their followers. It depends on their age group, and many things.(..) For those struggling with certain problems, it may help to see that certain simple measures worked well for this psychologist, for example.

Karianne (public health nursing student) said:

For my part, I prefer to have it more distanced. When health issues are concerned, a distanced form makes the health influencer more trustworthy, in my eyes. But I do see the potentials that lie in the opposite, a style that involves the sharing of their own experiences and life situations. That may contribute to normalising symptoms that one may experience, or normalising a certain life condition that one feels totally alone in.

Some informants noted that the difficult balance between representing a field of science on the one hand and building their own personal brand on the other, becomes particularly visible when health influencers promote their own books instead of guiding followers to consult other sources or other health experts. Kine (psychology student) said:

There may be various motifs behind the media activity. Some may write that …ok, if this strikes you, you can read more about it in my book. Instead of saying, ok, if this strikes you, you should see a psychologist, here is the number to so and so…

On the other hand, some informants expressed that they understand that money is a natural—and sometimes necessary—element in a long-term engagement as a health influencer. Ingvild (psychology student) said:

All the health influencers I have observed… they all seem to possess a genuine desire to help. They do not appear to be bad people who only think about money. But gradually, if you see that... here I can make some money if I write a book. It is a natural thing to think. No one hates money. Or some of them may wish to become famous. And you may question how moral such a wish is. But anyway, if they do the right things, they still do a good job in terms of preventive care and health promotion.

The choice between building an approachable and personal identity as a health influencer or rather constructing a professional, distanced expert-identity, became a core issue in the conversations with the informants. It concerns questions of engagement and trust, and it also involves questions of ethical standards and dilemmas. The existence of a personalized social relationship is key to having an impact on the attitudes and actions of other people. But in a situation where it is impossible to follow up such a relationship by offering individual advice and guidance; is it still ethically acceptable to build such a relationship? On this issue, the reflections of the informants follow various trajectories. Beate (medicine student) said:

Some of the influencers I have looked at have a strong personal style, and I believe they become important figures in the lives of many young people. And that is a good thing, because they offer a lot of good advice. But then, when a young person feels that…this is meant for me, and yet, they cannot get in touch with the sender, that may lead to problems. It means that health influencers should be very explicit, saying that…I am not your psychologist. If you are struggling, you should consult someone else.

The issues of identity and style lead to the question of who the health experts on social media actually are representing. Do they work as a new first-line service, implying that they have a role in the public health care system? Or do they only represent themselves? It should be noted that some health influencers work their day job in various public health institutions, while others earn their living from personal enterprises. The informants, all familiar with the public health care system in Norway, have different views on this question. Marie (public health nursing student) said:

They are not employed by anyone; they are independent actors. And what they do is mainly to offer information, not health care. So, I would not call them a new first-line service.

Other informants are more open to the idea that qualified health workers on social media can function as a new first-line service. Beate (medicine student) said:

When you mentioned first-line service, I thought that...since everyone is on social media nowadays, this may be the first place that you meet issues related to mental health. Or to corona. This may be the first step. And then you might become more curious, you read more and bring it to your GP, who may then send you to a specialist. I think this might be the first line, yes. But in a grey-zone, somehow.

Nina (medicine student) agreed with Beate, and said:

A first-line service, yes. You check with people you trust first. Then you may consult the public health system in the next step.

While the informants generally conveyed positive attitudes toward the efforts of health experts on social media, none of the 17 informants expressed an ambition to assume a similar publicly exposed role when explicitly asked. Several reasons for this reluctance were mentioned, including the fear of making mistakes or tarnishing the reputation of their own profession; the fear of facing public criticism, and the sense of being responsible for the health of other people without the ability to provide continuous support. Ingvild (psychology student) said:

If you have 100 000 followers, it is probably impossible to answer all the messages you receive. How would you choose between them? I would have felt really bad not being able to follow up all those who contacted me. Being a popular health influencer, you have no contract about following up everyone contacting you. But I think you have some sort of moral responsibility. I would not feel ok about it. That is one of the reasons why I never would wish to be a person with many followers, someone known to many.

Nina (medicine student) said:

My field of interest is neuroscience, which is research on the human brain, and I want to continue working in that field. And I think it would be very useful to inform people about that topic. But it is really hard to explain it in a proper manner, without making it banal and incorrect. (..) I think that is a reason why I would not choose to become a public figure. I am not sure whether it is even possible to disseminate it in a proper way.

Another reason for reluctance was particularly related to how some of the informants viewed the profession of psychologists. One informant, Ronja, studying psychology, felt that practicing both as a clinical psychologist and as an influencer on mental issues would be difficult to combine. She said:

Being an influencer, you are supposed to put focus on yourself and who you are—which is somehow the opposite of what a psychologist is supposed to do when working with therapy. (..) In a way, being a psychologist is different from being a psychology influencer.

Although they were skeptical about assuming the role of a publicly exposed health influencer themselves, several informants acknowledged that they were inspired by such media actors. They reported that health experts on social media had made them more aware of the importance of making their own knowledge accessible to others.

Fredrikke (public health nursing student) said:

I think she [a public health nurse on social media] is really accessible. And we may feel a bit of a pressure because we are not equally accessible. We may not have to open a Snapchat-account, but we need to think of new solutions to become more accessible. Maybe for both good and bad.

In the introduction of this paper, I asked: How do future healthcare workers perceive the media practices of popular health influencers regarding the advantages and dilemmas associated with such practices? Using the three focus group interviews with 17 students enrolled in health-related study programmes at Norwegian universities as an indicator, we can now ask more specifically: How did the participants view today's health experts on social media regarding the three key factors for effective science communication mentioned by Bauer (2009): understandability, engagement, and trust?

Overall, the participants recognized the strong potentials of such media activity concerning all three factors. But they also identified certain challenges and dilemmas. While simplification was acknowledged as necessary in popular dissemination, several participants—particularly those studying psychology—noted that the sharing of generalized advice can be problematic, since individual followers may experience health issues in very different ways. It is difficult to offer advice adapted to individual needs when you have 100,000 followers on Instagram, it was mentioned.

Concerning engagement and trust, these factors were closely connected to the kind of sender-identity that is being constructed by the individual health expert. Van Leeuwen (2022) emphasizes that different types of identity can be expressed through different styles, which encompass choices related to clothing, language, visual symbols etc. A specific area of research examines how identities are formed within the realm of social media. Platforms like Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, and TikTok provide opportunities for individuals to creatively curate their identities through the arrangement of words, voice, camera angels, colors, and other semiotic resources (see, e.g., Rettberg, 2014). Applying the four kinds of identity suggested by Van Leeuwen (2022)—individual identity; social identity; role identity, and lifestyle identity—we can conclude that the informants valued the significance of the different kinds of identity differently in this context. Some participants valued individual identity and lifestyle identity strongest, emphasizing that a key success factor on social media is to build a personal brand by applying a personal style and sharing personal details and ideas. Others valued more strongly a style that reflects the social role and responsibilities of being a public health expert, representing institutionalized knowledge and traditions. It was said that a more objective and distanced style makes health experts appear more trustworthy, even on social media. These different views touch upon critical comments that have surfaced in the trade press regarding potential ambiguities in terms of roles and identities, that may occur when popular health influencers use their professional titles on their private social media channels. In a Norwegian journal for nurses, concerns are expressed that it can seem hard to distinguish between their role as entrepreneurs, promoting their own enterprises, and their role as healthcare professionals (Fjelldal, 2019).

In the literature on health experts using social media for health communication, many commentators are concerned about the risk of sensitive information being exposed in the sections with followers' comments (e.g., Munson et al., 2013; Yonker et al., 2015; Farsi, 2021). When asked explicitly about ethical concerns, none of the participants in the study mentioned this issue. What many were more concerned about, was the responsibility related to giving generalized health advice without being able to follow up each receiver individually. This finding may indicate that the next generation of health care givers (contrary to media scholars?) assume that the sharing of personal information is a normal thing to do for many users of social media, and that those who share such information, know what they are doing. This view corresponds to opinions expressed by health experts active on social media (Engebretsen, 2024).

The results of the study are relevant for several groups. Media scholars are informed on the reception of a new media practice; health professionals active on social media can see and review detailed feedback on activities similar to their own, and health authorities are offered input to evaluate and guide a new communication practice that involves qualified health personal. The results also have implications for educators. If qualified health advice on social media can be seen as a new first-line service, an idea that several participants agreed to, such dissemination activity should be reflected in relevant health-related study programmes. Parallel to the growing attention to patient-doctor communication in medical education (see, e.g., Ong et al., 1995), a similar attention to expert-audience communication online would be a useful outcome of the growing body of research in this novel field of practice. To support future curricula changes in this direction, more research is needed to understand and evaluate the social and professional role of qualified health influencers on social media. What rhetorical strategies are the most effective in terms of understandability and engagement? What professional and ethical norms and values are most suitable to guide such media activities? And how can non-expert audience members distinguish between trustworthy and less trustworthy health information on popular social media platforms? The questions are multiple, and they call for multiple approaches in terms of research design and methodology.

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the article is based on anonymized transcriptions of focus group interviews. The interviewees were not asked to accept re-use of the interview data beyond the described study so the data cannot be used by others. Queries relating to the research may be directed to the author.

The study was approved by Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research. The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their informed consent to participate in this study.

ME: Writing – original draft.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The study was funded by a grant from The Norwegian Media Authorities (grant no. 21/2073) and by the author's home institution, University of Agder.

Thanks to the Norwegian Media Authorities for funding the study from which this article is derived. And a big thanks to the 17 participants that openly shared their thoughts and opinions on the topic of interest in this article and thus made it a feasible project.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. ^I use the concept of “influencers” according to the wide definition presented on the web site of Vixen Awards, an organization that annually awards prizes to Norwegian influencers: “An influencer is a person who has an influence on others through content that is created and shared in their own channels and on social media.” (My translation from Norwegian). Downloaded August 28th, 2023, from https://www.vixen.no/.

2. ^The study is part of a project funded by The Norwegian Media Authorities. Other parts of the project include a multimodal discourse analysis of one selected case (Engebretsen, 2023), and an interview-based study of three awarded health influencers (Engebretsen, 2024).

3. ^See the interview guide in Appendix 1. The same guide was used in all three interviews.

4. ^According to statistics from the Norwegian Directorate for Higher Education and Skills, 81 per cent of the students starting health-related studies in 2022 were women. https://www.samordnaopptak.no/info/om/sokertall/sokertall-2022/sluttstatistikk-uhg-2022.pdf.

5. ^The informants were asked to study the following social media accounts for preparation: https://www.instagram.com/psyktdeg/, https://www.youtube.com/c/DrWasimZahid, and https://www.instagram.com/helsesista/. See Engebretsen (2023) for a multimodal case study of the Instagram account PsyktDeg.

6. ^All citations are translated from Norwegian to English by author. When a sequence of words from the transcript is omitted in the citation, it is marked with (..).

Atef, N., Fleerackers, A., and Alperin, J. (2023). “Influencers” or “doctors”? Physicians' presentation of self in Youtube and Facebook videos. Int. J. Commun. 17, 2665–2688. doi: 10.31235/osf.io/2rbt7

Basch, C. H., Fera, J., Pierce, I., and Basch, C. E. (2021). Promoting mask use on TikTok: descriptive, cross-sectional study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 7:e26392. doi: 10.2196/26392

Bauer, M. W. (2009). The evolution of public understanding of science: discourse and comparative evidence. Sci. Technol. Soc. 14, 221–240. doi: 10.1177/097172180901400202

Campbell, L., Evans, Y., Pumper, M., and Moreno, M. (2016). Social media use by physicians: a qualitative study of the new frontier of medicine. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 16:91. doi: 10.1186/s12911-016-0327-y

Chen, J., and Wang, Y. (2021). Social media use for health purposes: systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 23:e17917. doi: 10.2196/17917

Davies, S., and Hara, N. (2017). Public science in a wired world: how online media are shaping science communication. Sci. Commun. 39, 563–568. doi: 10.1177/1075547017736892

Davies, S., and Horst, M. (2016). Science Communication. Culture, Identity and Citizenship. London: Palgrave. doi: 10.1057/978-1-137-50366-4

Engebretsen, M. (2023). Communicating health advice on social media: a multimodal case study. Mediekultur 39, 164–184. doi: 10.7146/mk.v39i74.134085

Engebretsen, M. (2024). På YouTube og Instagram i Folkehelsas Tjeneste. En Studie av Tre Helsearbeidere på Sosiale Medier. [On YouTube and Instagram in the Service of Public Health. A Study of Three Health Workers on Social Media]. Norsk Medietidsskrift.

Farsi, D. (2021). Social media and health care, part I: literature review of social media use by health care providers. J. Med. Internet Res. 23:e23205. doi: 10.2196/23205

Farsi, D., Martinez-Menchaca, H., Ahmed, M., and Farsi, N. (2022). Social media and health care, part ii: narrative review of social media use by patients. J. Med. Internet Res. 24:e30379. doi: 10.2196/preprints.30379

Ferrell, D., and Campos-Castillo, C. (2022). Factors affecting physicians' credibility on Twitter when sharing health information: online experimental study. JMIR Infodemiology 2:e34525. doi: 10.2196/34525

Fjelldal, S. (2019). Hvilken Rolle har Helsesista? [What role does Helsesista have?] Debate post in Sykepleien (Norwegian journal for nurses), 03.12.2019. Available online at: https://sykepleien.no/meninger/innspill/2019/11/hvilken-rolle-har-helsesista (accessed September 14, 2023).

Fontaine, G., Maheu-Cadotte, M., Lavallée, A., Mailhot, T., Rouleau, G., Bouix-Picasso, J., et al. (2019). Communicating science in the digital and social media ecosystem: scoping review and typology of strategies used by health scientists. JMIR Public Health Surveil. 5:e14447. doi: 10.2196/14447

Gabarron, E., Bradway, M., and Årsand, E. (2020). “Social media for adults,” in Diabetes Digital Health, eds D. Klonoff, D. Kerr, and S. Mulvaney (Amsterdam: Elsevier), 119–129. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-817485-2.00009-2

Jenkins, E., Ilicic, J., Barklamb, A., and McCaffrey, T. (2020). Assessing the credibility and authenticity of social media content for applications in health communication: scoping review. J. Med. Int. Res. 22. doi: 10.2196/17296

Kite, J., Foley, B., Grunseit, A., and Freeman, B. (2016). Please like me: Facebook and public health communication. PLoS ONE 11:e0162765. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0162765

Martini, T., Czepielewski, L., Baldez, D., Gliddon, E., Kieling, C., Berk, L., et al. (2018). Mental health information online: what we have learned from social media metrics in BuzzFeed's Mental Health Week. Trends Psychiatry Psychother. 40, 326–336. doi: 10.1590/2237-6089-2018-0023

Moreno, M., and D'Angelo, J. (2019). Social media intervention design: applying an affordances framework. J. Med. Internet Res. 21:e11014. doi: 10.2196/preprints.11014

Munson, S., Cavusoglu, H., Frisch, L., and Fels, S. (2013). Sociotechnical challenges and progress in using social media for health. J. Med. Internet Res. 15:e2792. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2792

Ong, L. M. L., de Haes, J. C. J., Hoos, A. M., and Lammes, F.B. (1995). Doctor-patient communication: a review of the literature. Soc. Sci. Med. 40, 903–918. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00155-M

Powell, R., and Single, H. M. (1996). Methodology matters: focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 8, 499–504. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/8.5.499

Rettberg, J. W. (2014). Seeing Ourselves through Technology: How we use Selfies, Blogs and Wearable Devices to see and Shape Ourselves. London: Palgrave Macmillan. doi: 10.1057/9781137476661

Steffens, M., Dunn, A., Leask, J., and Wiley, K. (2020). Using social media for vaccination promotion: practices and challenges. Digi. Health 6. doi: 10.1177/2055207620970785

Suarez-Lledo, V., and Alvarez-Galvez, J. (2021). Prevalence of health misinformation on social media: systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 23:e17187. doi: 10.2196/17187

Torjesen, A. (2021). The genre repertoires of Norwegian beauty and lifestyle influencers on YouTube. Nordicom Rev. 42, 168–184. doi: 10.2478/nor-2021-0036

Van Leeuwen, T. (2022). Multimodality and Identity. London, NY: Routledge doi: 10.4324/9781003186625

Yonker, L., Zan, S., Scirica, C., Jethwani, K., and Kinane, T. (2015). “Friending” teens: systematic review of social media in adolescent and young adult health care. J. Med. Internet Res. 17:e4. doi: 10.2196/jmir.3692

Project: Health workers on social media

Project leader: Prof. Martin Engebretsen, University of Agder

Interview guide, focus groups

(Translated from Norwegian)

1. Age, gender and professional background (type of study) of the participants.

2. Did you know any of the three selected health influencers before you were asked to participate in the study?

- Do you know other, similar health professionals on SoMe?

- Have you yourself been an active follower of any of these actors on SoMe?

3. Are you yourselves affected by these types of media actors when it comes to your own understanding of your profession and social role?

- Do you, for example, either feel identification—or distance?

- Do you experience that they simplify the professional content too much (oversimplification)?

- Do you yourself become more aware of the importance of communicating professional knowledge in a way that is adapted to a target audience, or that is creative and innovative?

- Do you feel like taking a similar role yourself in the future, using digital media?

4. Do you believe that these actors reach their target audiences in terms of providing them with…

- a better understanding of their own health?

- a better relationship with themselves and their own body/mental health?

- greater trust in qualified health experts?

5. Do you believe that health communication in social media can motivate changes in lifestyle or mindset?

- Are there any differences between young and older followers in this regard?

6. Do you see any professional or ethical dilemmas associated with this type of practice?

- Is it a problem that the style and tone of social media and professional healthcare are inherently different (personal and intimate vs. professional and distant)?

- Is it a problem that sharing and interaction are expected on social media, while anonymity and discretion are expected in other forms of contact with healthcare?

7. How do you perceive the social role of this group of health communicators?

- Are they “private” knowledge disseminators, who stand outside the healthcare system, but are driven by a desire to contribute to better public health?

- Are they a kind of frontline service that helps people in need move further into the healthcare system?

- Are they primarily commercial actors, operating primarily on market terms?

- Are they a kind of “rock stars” attracted by the attention and reward system that social media can provide?

- Something completely different? Or something more mixed—difficult to generalize?

Instruction: Present the main, open question first—then specify in the next round if the proposed points have not been mentioned in the conversation.

Keywords: social media, health communication, trust, social roles, focus group interviews, students, health experts

Citation: Engebretsen M (2024) The role, impact, and responsibilities of health experts on social media. A focus group study with future healthcare workers. Front. Commun. 9:1296296. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2024.1296296

Received: 18 September 2023; Accepted: 21 February 2024;

Published: 12 March 2024.

Edited by:

Parul Jain, Ohio University, United StatesReviewed by:

Rita Gill Singh, Hong Kong Baptist University, Hong Kong SAR, ChinaCopyright © 2024 Engebretsen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Martin Engebretsen, bWFydGluLmVuZ2VicmV0c2VuQHVpYS5ubw==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.