- 1RTI International, Dublin, Ireland

- 2Office of Science, Center for Tobacco Products, Silver Spring, MD, United States

- 3RTI International, Durham, NC, United States

Background: In February 2020, FDA prioritized enforcement of flavored (other than tobacco- or menthol-flavored) cartridge-based electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) without premarket authorization. To explore potential marketing changes, we conducted a content analysis of brands' social media posts, comparing devices and flavors before/after the policy.

Methods: We sampled up to three posts before (November 6, 2019–February 5, 2020) and after the policy (February 6–May 6, 2020) from brands' Instagram (n = 33) and Twitter (n = 30) accounts (N = 302 posts). Two analysts coded posts for device type and flavor. We summarized coded frequencies by device, flavor, and device-flavor combination, and by platform.

Results: In posts mentioning devices and flavors, those featuring flavored (other than tobacco- or menthol-flavored) cartridge-based devices (before: 2.5%; after: 0%) or tobacco- or menthol-flavored cartridge-based devices (before: 0%; after: 2.8%) were uncommon while any flavor disposables were most common (before: 10.8%; after: 14.6%) particularly after the policy. Half of posts featured devices without flavor (before: 50.0%; after: 50.0%) and one-fifth had no device or flavor references (before: 21.5%; after: 18.8%).

Conclusions: In the months before and after the policy, it appears ENDS brands were not using social media to market flavored (excluding tobacco- or menthol-flavored) cartridge-based ENDS (i.e., explicitly prioritized) or tobacco- or menthol-flavored cartridge-based devices (i.e., explicitly not prioritized). Brands were largely not advertising specific flavored products, but rather devices without mentioning flavor (e.g., open/refillable, disposable devices). We presented a snapshot of what consumers saw on social media around the time of the policy, which is important to understanding strategies to reach consumers in an evolving ENDS landscape.

1 Introduction

Between 2017 and 2019, the United States (US) witnessed rapid increases in past 30-day use of electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) and frequency of youth ENDS use (Cullen et al., 2018, 2019; Miech R. A. et al., 2019; Miech R. et al., 2019). The majority of youth (12–17 years) and young adult (18–24 years) ENDS users reported they first used a flavored product (Rostron et al., 2020); about 20% of middle and high school users reported they used ENDS because they were available in flavors they liked (e.g., mint, candy, fruit) (Wang et al., 2019). Evidence from 2019's National Youth Tobacco Survey suggested middle and high school students prefer cartridge-based ENDS (Cullen et al., 2019), which have high nicotine content, are easily concealed and used discreetly (Kong et al., 2019; Romberg et al., 2019).

Rapid increases in youth ENDS use coincided with 97% ENDS market growth from 2017 to 2018 (LaVito, 2018). In 2019, the bestselling ENDS brand was cartridge-based device JUUL, representing approximately 70% market share [see Supplementary material S1: Nielsen Data Source (a) for full description]. JUUL was one of the earliest brands to use widespread social media marketing (Jackler, 2019). A 2018 study found that at the time, many top-selling brands, including JUUL, either no longer posted content or left social media, possibly due to controversy or unwanted regulator attention (Scutti, 2018). Other ENDS brands continue to promote products via social media (O'Brien et al., 2020).

ENDS brands may utilize multiple social media platforms (e.g., Instagram, Twitter) to market products to users and potential users (Artman, 2019; O'Brien et al., 2020), including youth (Myers et al., 2018; Cho et al., 2019). Social platforms prohibit paid tobacco product advertising (Facebook, 2021; Twitter, 2021), making brands dependent on nonpaid marketing strategies (e.g., posting to brand social media pages) or influencers to promote products. One study found that more than half of youth surveyed reported exposure to ENDS ads, with social media as the main exposure channel (Cho et al., 2019). Youth exposure to tobacco social media marketing is associated with increased initiation, increased use frequency, progression to poly use, and decreased cessation incidence (Depue et al., 2015; Soneji et al., 2018).

The 2009 Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act granted the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) authority to regulate the manufacture, marketing, and distribution of tobacco products to protect public health and reduce minors' use (US Food and Drug Administration and US Department of Health and Human Services, 2011). Subsequently, FDA issued a rule establishing that, among other product types, ENDS meet the statutory definition of a tobacco product and are subject to FDA's tobacco product authorities (US Food and Drug Administration and US Department of Health and Human Services, 2016).

In response to the increase in youth ENDS use, particularly flavored cartridge-based devices, FDA issued final guidance in January 2020 (revised April 2020) for industry describing how FDA intended to prioritize enforcement resources with regard to marketing of certain deemed tobacco products, such as flavored (other than tobacco or menthol) cartridge-based ENDS without premarket authorization. Companies were given 30 days to “cease the manufacture, distribution, and sale of unauthorized flavored cartridge-based e-cigarettes (other than tobacco or menthol)” or risk FDA enforcement action upon policy implementation on February 6, 2020 (Center for Tobacco Products, 2020). Pending the September 9, 2020 deadline for submission of applications for pre-market review of ENDS products, other unauthorized ENDS products, specifically tobacco- or menthol-flavored cartridge-based devices and non-cartridge-based devices of any flavor, were not prioritized for enforcement unless products met criteria for enforcement priority under other categories (e.g., guidance describes prioritizing enforcement against any ENDS product with marketing that may target or promote minors' product use or that lacks adequate measures to prevent minors' access).

One previous study characterized industry marketing on Instagram before and after the policy implementation (January 1, 2019–December 31, 2021) and found that strategies included promotion of open/refillable ENDS devices and e-liquids, products in non-characterizing flavors (e.g., chill), stockpiling flavored products, and international product delivery (Kostygina et al., 2022). In this study, we conducted a content analysis of posts from official ENDS brands' Twitter and Instagram accounts to describe marketing of devices and flavors before and after implementation of the policy. We focused on device-flavor combinations prioritized (or not prioritized) by the policy and did not focus on additional policy provisions (e.g., products with inadequate measures to prevent minors' access).

2 Materials and methods

This study was deemed not human subjects research by RTI International's Institutional Review Board (RTI Office of Research Protection) on April 3, 2020.

2.1 Brand identification

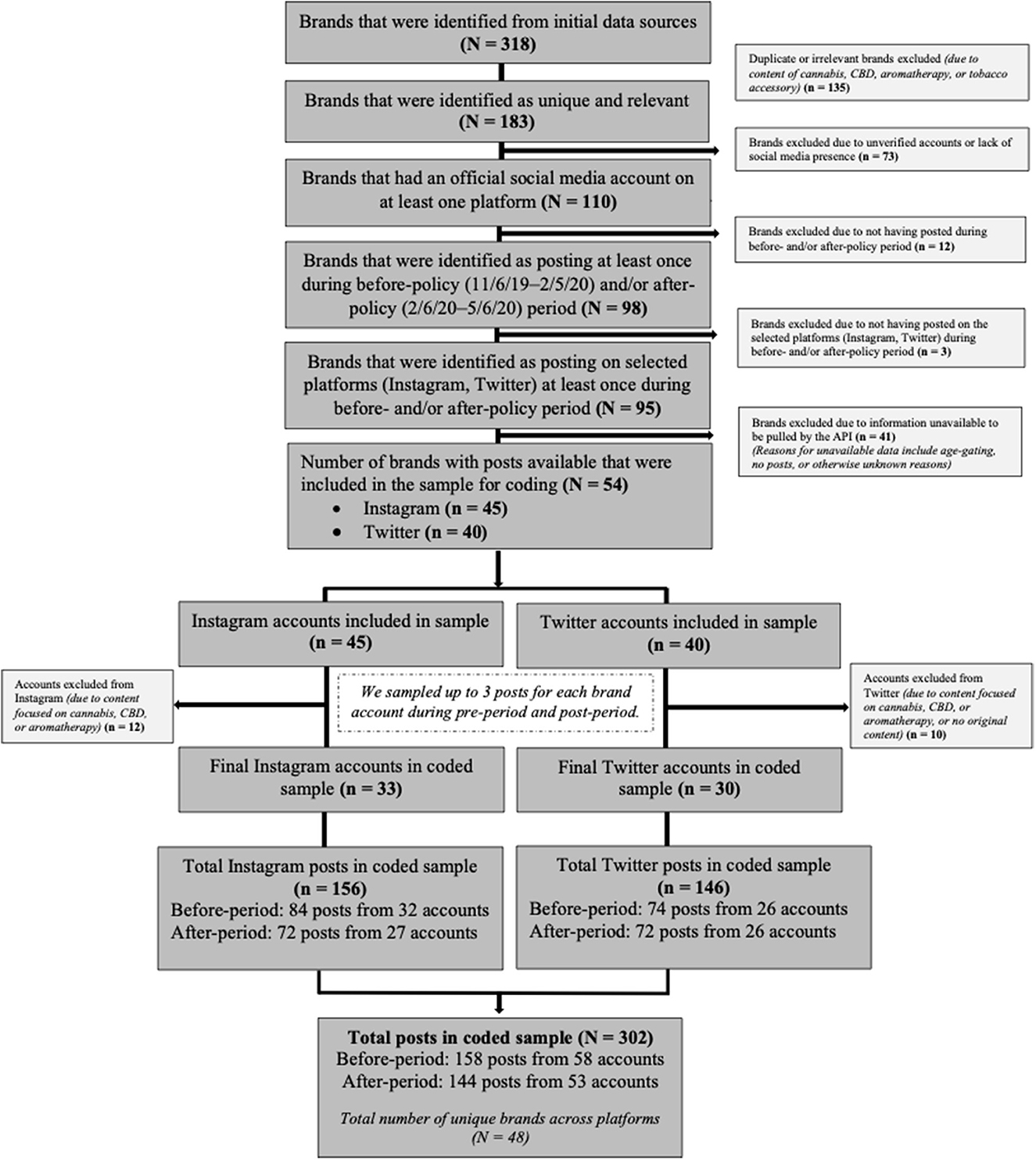

We adapted O'Brien et al.'s (2020) approach to identify top US ENDS brands and accompanying social media accounts and extract posts from the final sample of accounts for coding. We used four sources to identify brands. First, we used Nielsen Retail Measurement Service data to identify brands with >$1,000 sales in US retail stores from November 2019 to May 2020 (n = 90) [see Supplementary material S1: Nielsen Data Source (b) for full description]. Second, we used Numerator to identify all brands that purchased television, newspaper, magazine, trade magazine, or online ads from November 2019 to May 2020 (n = 86). Third, we identified all brands in the following ECigIntelligence data: E-liquids and Hardware: Consumer Survey (November 2019); Vape Store Survey (August 2019); ECigIntelligence Online Brands Tracker Q1 2020 (February 2020); and Disposables (data collected by ECigIntelligence from leading US online multibrand vape retailers, May 2020) (n = 92). Fourth, we used Google Search Trends to identify brands using US ENDS/vaping-related search terms (e.g., e-cigarettes, disposable vapes) from November 2019 to May 2020 (n = 50). Our initial list included 318 brands (Figure 1). We excluded 135 duplicate or irrelevant brands from our potential sample using the following criteria: duplicate brands identified in multiple sources (n = 89); cannabis-related brands (e.g., CBD FX, Leafly) (n = 11); tobacco accessory brands (e.g., Zig Zag) (n = 2); and duplicate brands with different products under a single brand and social media account (e.g., Instagram account nowposh posted about Posh and Posh Plus; counted as one brand) (n = 33). Exclusions resulted in 183 brands remaining for analysis.

2.2 Identification of official brand social media accounts

From the list of 183 brands, we identified official social media accounts by visiting each brand's website and collecting information on linked accounts in May/June 2020. For brands without official websites, we searched brand names directly on social media platforms. Using O'Brien et al.'s (2020) criteria, we included accounts with public social media pages and at least one of the following: the term “official” or “verified”, link to the brand website, or only one brand promoted (e.g., JUUL account promotes only JUUL products). We excluded 73 brands with unverified accounts (i.e., accounts were not linked to the brand website, were fan pages, used language other than English, were outside the US, had no posts) or lacked a social media presence (i.e., no brand accounts). This resulted in 110 brands with official accounts on at least one platform (Figure 1).

2.3 Identification of active social media accounts

To qualify for sample inclusion, brand accounts had to have posted at least once in the time periods before (November 6, 2019–February 5, 2020) or after the policy (February 6, 2020–May 6, 2020). We manually reviewed posts in July 2020. Of the 110 brands with official accounts, 98 posted at least once during the study period (91 before the policy, 88 after the policy, and 86 in both time periods) (Figure 1). Most brands had official Instagram (n = 89), Facebook (n = 89), and Twitter accounts (n = 70), with few on YouTube (n = 46) and Tumblr (n = 3). We prioritized Instagram and Twitter due to the number of brands with a presence on these platforms, higher use by youth (72% of teenagers use Instagram vs. 40% of adults; 32% of teenagers use Twitter vs. 23% of adults) (Pew Research Center, 2021), and greater ease of accessing historical data. Instagram was prioritized over Facebook as the content was repetitive (Facebook owns Instagram and they use the same posting platform) and Instagram has a higher proportion of youth users (Pew Research Center, 2018, 2021). Ninety-five brands with official accounts on Instagram or Twitter posted at least once during the study period (Figure 1).

2.4 Social media post identification

In July 2020, we used a licensed application programming interface (API), Apify, and Twitter's API to identify all public posts that the 95 brands shared on Instagram and Twitter during the study period. We could not pull data from 41 accounts because they were gated by Instagram due to age restrictions (n = 4), had no posts (posts deleted between manual review and API pull) (n = 3), were dead links (n = 5), or data could not be extracted via an API (n = 29). For the 54 brands with available data (Instagram n = 45, Twitter n = 40), we used Stata's pseudorandom number generator to randomly sample up to three posts from the time period before the policy and up to three posts from after policy for each brand's social media account(s). While some brands only posted once in the study period, one brand posted 897 times. Sampling up to three posts per account per period allowed insight into each brand's marketing while ensuring individual brands' practices received nearly equal weight.

2.5 Coding

During coding, we excluded an additional 12 Instagram and 10 Twitter accounts that were irrelevant because they sold cannabis or advertised CBD or aromatherapy products and not tobacco products, which was not indicated by the brand name identified during the brand screening stage. The final coded sample included 302 posts from 33 Instagram (156 posts) and 30 Twitter (146 posts) accounts.

Two trained analysts used a priori codes to code post characteristics and compared results for all posts (all posts double-coded). A third person resolved coding discrepancies.

2.5.1 Account characteristics

The API extracted the number of posts and followers for each brand's account(s) as of July 2020 (Supplementary Table S1).

2.5.2 Post characteristics

The API pulled information for post characteristics, including post date and text. Additional post data pulled from the API included post link, hashtags, and engagement data. Coders manually coded the remaining measures below.

2.5.3 Device type

Coders reviewed post text and images and coded number and type of devices in posts. If text and image were inconsistent, coders classified the device using the text. The codebook included device keywords (e.g., “disposable,” “bars,” “puff count” to describe disposable devices) and images.

Coders classified device type(s) based on seven mutually exclusive categories: (1) cartridge-based ENDS devices using an enclosed, sealed, prefilled cartridge/pod that holds liquid to be aerosolized (includes cartridges/pods sold separately); (2) disposable devices sold ready for use (filled and charged) and disposed of when liquid or battery depletes; (3) open/refillable system devices (i.e., mods, tank systems, devices using unsealed, empty, refillable cartridges); (4) bottles of e-liquids for refilling; (5) other components/parts (e.g., batteries, coils) or accessories (e.g., carrying cases); (6) multiple devices from the prior categories (multiple devices of the same type coded once); and (7) irrelevant content (i.e., post had no ENDS product, see Table 1).

If a device was cartridge-based, we collected data on whether the post contained the device only, device and cartridge/pod, or unknown. If the post included an e-liquid or cartridge/pod, we collected data on whether the device was a pod for a non-disposable cartridge-based device, a bottle of e-liquid for refilling, or other.

2.5.4 Flavor

We coded all flavors in posts. Coders examined (1) text appearing in the post description and/or on the image (e.g., “mint eliquid”) and (2) images (e.g., image of a disposable device with a strawberry). If the text and image were inconsistent, coding was based on the text.

We used six mutually exclusive flavor categories: (1) explicit flavors (e.g., crème brûlée) that are non-menthol, non-mint, non-tobacco, including flavors in which part of the name was an explicit non-menthol, non-mint, non-tobacco flavor (e.g., strawberry menthol); (2) explicit mint (i.e., mentioned “mint,” “spearmint,” “wintergreen,” “peppermint” in post or image text); (3) explicit menthol (i.e., mentioned “menthol” in post or image text); (4) explicit tobacco; and (5) undetermined/concept [implicit or ambiguous terms (e.g., red, tropical)]. If there were multiple products with multiple flavors in a post, this was coded as (6) multiple flavors. Each flavor was categorized once, meaning “minty melon” was coded as non-menthol, non-mint, non-tobacco flavor, and not also as mint. If mint was present in a single flavor name with menthol or tobacco (e.g., “minty menthol”), the flavor was categorized once as mint. If no flavor was indicated, the flavor was considered “missing” (Supplementary Table S2 provides detailed flavor category definitions).

Throughout the manuscript, “flavored” is defined as any explicit flavor other than tobacco- or menthol-flavor. “Any flavor” refers to all explicit flavors including tobacco, menthol, mint, or any other flavor.

2.5.5 Device-flavor combinations

We combined coded data on device type and flavor to create a variable “device-flavor combination” with eight categories (see Table 1 for examples and Supplementary Table S3 for device-flavor categories): (1) posts featuring only flavored (e.g., mint) cartridge-based ENDS; (2) posts featuring only tobacco- or menthol-flavored cartridge-based ENDS; (3) posts featuring only disposable devices in any flavor (e.g., mango-flavored disposable device); (4) posts featuring only e-liquid in any flavor (e.g., raspberry-flavored e-liquid); (5) posts featuring only concept-named cartridge-based ENDS (e.g., gold-named); (6) posts featuring products from more than one preceding category (e.g., post mentioning berry-flavored and menthol-flavored cartridges); (7) posts featuring devices and no flavor reference (e.g., open/refillable devices with no e-liquid, cartridge-based ENDS devices sold without pods/cartridges; other device components; product accessories); and (8) posts not featuring any ENDS device or flavor (e.g., “Happy New Year” with no product in post).

If multiple device-flavor combinations from the same category were in a post (e.g., tobacco- and menthol-flavored cartridge-based ENDS in one post), they were counted once in the appropriate category. No posts featured a flavor and no device.

2.6 Analysis

We summarized descriptive frequencies for all measures. To explore brands' social media activities before and after the policy, we stratified post characteristics by the time periods before (November 6, 2019–February 5, 2020) and after the policy (February 6, 2020–May 6, 2020), and by social media platform (Instagram, Twitter). Analyses were conducted using Stata 16.0.

3 Results

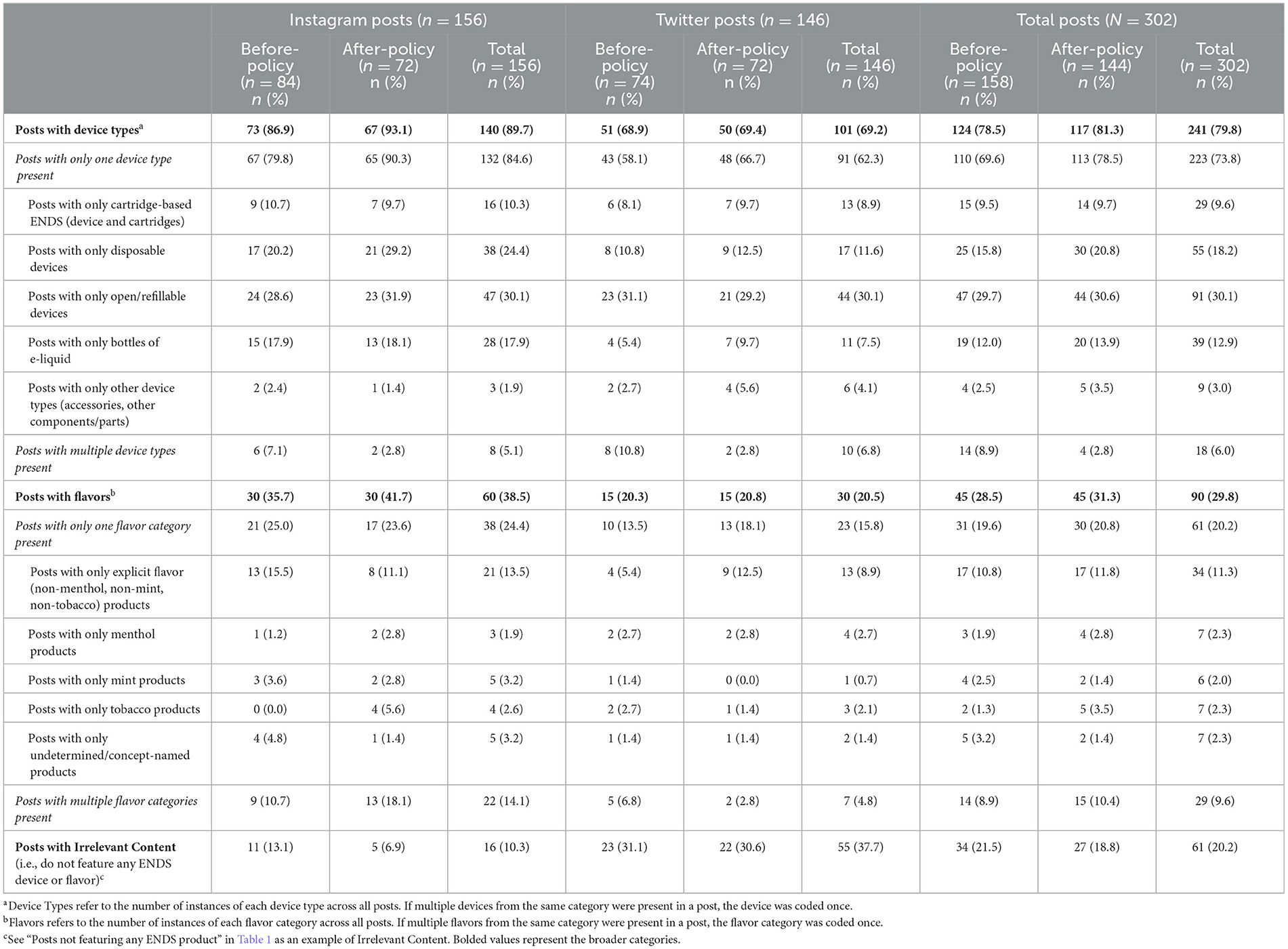

Table 2 describes post characteristics for coded posts (N = 302) in the before- and after-policy periods with summaries of device types and flavors in posts, overall and by platform. The majority of posts (79.8%) across the entire study period featured devices. More Instagram (89.7%) than Twitter posts (69.2%) featured devices. Nearly one-third of all posts (29.8%) indicated any flavor (tobacco, menthol, mint, or any other flavor) of product. More Instagram (38.5%) than Twitter posts (20.5%) indicated any flavor of product.

Table 2. Sample of ENDS brands' social media posts by device type and flavor categories during before-policy (November 6, 2019–February 5, 2020) and after-policy periods (February 6, 2020–May 6, 2020).

3.1 Device type

In both before- and after-policy periods, when brands included a single device type in posts, open/refillable system devices were most common (before: 29.7%; after: 30.6%), followed by disposable devices (before: 15.8%; after: 20.8%), bottles of e-liquid (before: 12.0%; after: 13.9%), and cartridge-based ENDS (before: 9.5%; after: 9.7%). Few posts featured multiple device types (before: 8.9%; after: 2.8%). Brands' posts featured more disposable devices on Instagram than Twitter (24.4% vs. 11.6%) and more e-liquids on Instagram than Twitter (17.9% vs. 7.5%).

3.1.1 Flavor

During both time periods, posts with explicit non-mint, non-menthol, non-tobacco flavor (e.g., fruit) products were more common (before: 10.8%; after: 11.8%) than posts with any of the following flavors: undetermined/concept (before: 3.2%; after: 1.4%); tobacco (before: 1.3%; after: 3.5%); menthol (before: 1.9%; after: 2.8%); and mint (before: 2.5%; after: 1.4%). About one-tenth of posts included multiple flavor categories in one post (before: 8.9%; after: 10.4%). In the after-policy period, Instagram had more posts featuring multiple flavors (18.1%) than Twitter (2.8%). No products were explicitly identified as “unflavored.”

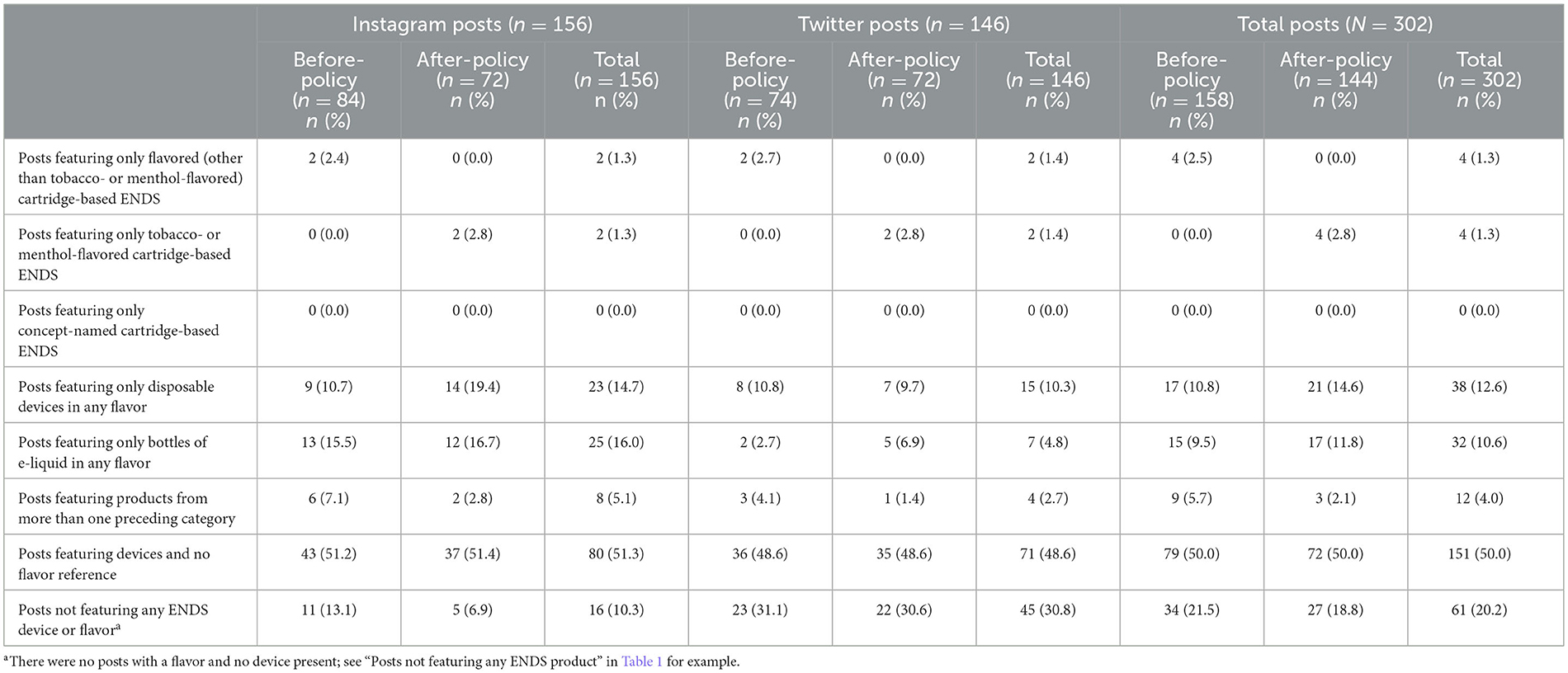

3.1.2 Device-flavor combinations

Table 3 provides a breakdown of posts with device-flavor combinations in before- and after-policy periods, overall and by platform. We observed few posts with only flavored cartridge-based ENDS (before: 2.5%; after: 0%) and with only tobacco- or menthol-flavored cartridge-based ENDS (before: 0%; after: 2.8%).

Table 3. Sample of ENDS brands' social media posts by device-flavor combinations during before-policy (November 6, 2019–February 5, 2020) and after-policy periods (February 6, 2020–May 6, 2020).

More posts featured disposable devices of any flavor (including tobacco, menthol, mint, or any other flavor) (before: 10.8%; after: 14.6%) and bottles of e-liquid in any flavor (before: 9.5%; after: 11.8%). There were more posts on Instagram featuring disposable devices in any flavor in the after-policy period (19.4%) vs. before-policy period (10.7%). There were also more Instagram than Twitter posts featuring disposables in the after-policy period (Instagram: 19.4%; Twitter: 9.7%). No posts featured only concept-named cartridge-based ENDS.

Half of posts featured ENDS devices but not flavor (e.g., open-refillable devices with no e-liquid) (before: 50.0%, after: 50.0%). About one-fifth of posts featured irrelevant content (i.e., no device and no flavor present) (e.g., “Happy Cinco de Mayo!”) (before: 21.5%; after: 18.8%) with more such posts on Twitter (30.8%) than Instagram (10.3%).

4 Discussion

We conducted a content analysis of industry posts on official ENDS brands' social media accounts to explore potential changes in marketing practices in the 3 months before and after implementation of the February 2020 FDA ENDS policy that prioritized enforcement of flavored (other than tobacco- or menthol-flavored) cartridge-based ENDS without premarket authorization (Center for Tobacco Products, 2020). We focused on industry marketing related to featured device types and flavors.

In our sample, we observed no social media posts featuring flavored (other than tobacco- or menthol-flavored) cartridge-based ENDS following policy implementation; however, we observed only a few posts featuring these products before implementation. Similarly, only a few posts featured tobacco- or menthol-flavored cartridge-based ENDS following implementation, with none before implementation. More commonly marketed ENDS products across the entire study period were device-flavor combinations not explicitly prioritized by the policy, including disposable devices of any flavor and bottles of e-liquid of any flavor (including tobacco, menthol, mint, or any other flavor). Nearly half of posts in our sample featured devices without any indication of flavor, and another one-fifth of posts made no reference to any ENDS product (no device and no flavor).

Findings are likely due to multiple factors. First, ENDS brands' marketing practices may have shifted earlier than 3 months before the policy. For example, JUUL voluntarily ceased cartridge sales in flavors other than mint, menthol, and tobacco in retail stores in November 2018 and online in October 2019, and stopped selling mint-flavored cartridges in stores and online in November 2019 (JUUL, 2018, 2019a,b). Exploring social media posts from <3 months before the ban may have allowed us to observe more posts with products referencing flavor. Second, the most common device type featured in posts was open/refillable devices, suggesting these brands may have been more likely to market products on social media during the study period than brands with devices with higher market share that were facing increasing policymaker scrutiny (e.g., cartridge-based ENDS). Results suggest that ENDS brands in this study more commonly promoted devices with no reference to flavor (e.g., posts featuring an open/refillable system).

Other studies show that tobacco companies adapt marketing and sales strategies in response to regulatory policies (e.g., Rogers et al., 2020, 2022; Kostygina et al., 2021, 2022; Do et al., 2023). One study explored direct-to-consumer email advertisements for menthol-flavored ENDS before and after FDA's prioritized enforcement of flavored (other than tobacco- or menthol-flavored) cartridge-based ENDS and found that advertisements for these products increased after the policy (Do et al., 2023). Two studies showed that when a new policy goes into effect, as was the case with the Providence, RI sales restriction on all non-menthol, non-mint, non-tobacco flavor tobacco products, sales (Rogers et al., 2020) and availability (Rogers et al., 2022) of products not covered by the policy increased. However, research shows that when a policy is more comprehensive (e.g., includes all non-tobacco flavors, includes all tobacco products, has no retail exemptions, includes sufficient resources for education and enforcement), as with the ban on all sales of tobacco products in flavors other than tobacco in San Francisco, CA, sales of products in flavors other than tobacco decreased (Gammon et al., 2021).

When exploring differences in industry marketing on Instagram and Twitter we observed two notable findings related to disposable devices. First, there were more disposable devices in posts on Instagram than Twitter in the after-policy period. Second, we observed a larger number of disposable device posts on Instagram in the after-policy compared to the before-policy period. These findings suggest that brands posting on Instagram may have shifted marketing to disposable devices, which were not explicitly prioritized in the guidance document. These findings are consistent with increasing popularity of disposable products among youth and young adults from 2019 to 2020 (Cullen et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2019, 2020; Rostron et al., 2020), and Instagram's younger-skewing audience (Pew Research Center, 2018, 2021).

Notably, we found that about one-fifth of posts from ENDS brands featured no ENDS devices and no flavors, a practice more common on Twitter than Instagram. In these posts, brands posted timely, attention-grabbing content (e.g., COVID-19 PPE giveaway—see Table 1), perhaps to build brand recognition (Evans et al., 2005) and credibility (Erdem and Swait, 2004). Also of note, many top-selling brands selling cartridge-based ENDS devices (e.g., Vuse, NJOY, Logic) either had no social media accounts, did not post during the study period, or had posts that could not be extracted via an API, and thus were not in our sample. Brands may also not be posting on easily monitored public social media, may be using paid influencers which are not easily monitored, or may be marketing products outside social media (e.g., point-of-sale, promotional emails). Thus, factors outside of the scope of this study may explain the lack of changes observed, including advertising content outside of social media channels, anticipatory changes to social media messaging, and/or deleted or altered posts.

5 Limitations

This study has several limitations. We collected before-policy (November 6, 2019–February 5, 2020) and after-policy (February 6, 2020–May 6, 2020) data in July/August 2020 and brands may have deleted or altered posts made between the time of posting and collection. Future studies using social media data may consider collecting data in real time to allow researchers to capture posts before they can be deleted or altered. Furthermore, the before-policy period included the policy announcement date of January 2, 2020, which may have impacted posts shared in the before-policy period. Draft policy guidance was published on March 14, 2019 (with an initial statement by the FDA Commissioner laying out major tenets of the guidance in November 2018) and brands may have changed marketing practices in advance of our study, which examines changes around the final policy. The study focused on social media marketing among a limited sample of ENDS brands that posted public content to Twitter and Instagram during the study period; conclusions may not generalize to posts from private accounts or accounts requiring age verification, other types of ENDS marketing, or other social media platforms. The study focused on a limited sample of official ENDS brands' posts, so conclusions may not generalize to all brand posts made in the periods. Additionally, some brands may have sold only one type of ENDS device type (e.g., only cartridges) and we may not expect the same type of posts or the same changes in marketing practices as ENDS brands that sold multiple device types. We did not sample posts by device type and some device types may be underrepresented. Our classification was based on our interpretation of the device types (e.g., classifying an unsealed, empty cartridge as an open/refillable device and not as a cartridge-based ENDS); others may classify devices differently. ENDS brands may be conveying flavor or product information through other types of marketing not captured here, such as magazine or point-of-sale advertising. Instagram is an image-oriented platform while Twitter is a text-oriented platform, so content posted on each platform may not be comparable. This study included a limited number of brands with a limited number of posts about flavors, which did not allow us to test for differences in posting activity between time periods. Other research may explore quantitative differences in brands' posting activity or may use mixed methods, triangulating social media data with additional data sources (e.g., sales data, survey data assessing consumer exposure to brands' posts). Finally, in addition to prioritizing enforcement of flavored (other than tobacco- or menthol-flavored) cartridge-based ENDS, the policy also prioritized enforcement of ENDS products, regardless of flavor or device type, with inadequate manufacturer measures to prevent youth access or that targeted marketing to youth. This aspect of the policy may have impacted marketing of ENDS device types and flavors; however, it was not the focus of our study.

6 Conclusions

This study explores changes in ENDS industry marketing practices on companies' official social media accounts in response to FDA's prioritized ENDS enforcement policy, although brands with the largest market share had little social media presence on official company accounts during the study period. Based on our observations, the device-flavor combinations explicitly prioritized by the policy (i.e., flavored [other than tobacco- or menthol-flavored] cartridge-based devices) did not appear to be commonly marketed on companies' official social media accounts before or after the policy. Rather, the most commonly marketed ENDS products featured no reference to flavor (e.g., an open/refillable device), followed by devices that were not explicitly prioritized by the policy (e.g., any flavor disposable devices or e-liquid bottles). Our findings combined with findings from other studies (Kostygina et al., 2021, 2022; Rogers et al., 2022), suggest industry marketing strategies may reflect a perceived opportunity in marketing product types not explicitly prioritized for enforcement.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

JG: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. ST: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. AR: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing—review & editing. SL: Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. AK: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing—review & editing. JN: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing—review & editing. STL: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing—review & editing. KS: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing—review & editing. JD: Supervision, Writing—review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the U. S. Food and Drug Administration Center for Tobacco Products (contract number HHSF223201810042B/75F40119F19002). The U. S. Food and Drug Administration coauthors contributed to the conceptualization of the study design, manuscript development, and decision to submit this research for publication.

Acknowledgments

R. Chew, M. Wenger, and J. Thompson provided data extraction and analysis support. L. Olson and Y. Lee with RTI and D. Neveleff with FDA provided critical review and comment on the manuscript drafts.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Author disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Food and Drug Administration.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2023.1274098/full#supplementary-material

References

Artman, J. (2019). Market your vape shop on social media. eCig One. Available online at: https://ecigone.com/vape-shop-help/market-vape-shop-social-media/ (accessed April 23, 2022).

Center for Tobacco Products (2020). Enforcement Priorities for Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems (ENDS) and Other Deemed Products on the Market Without Premarket Authorization (revised): Guidance for Industry. Silver Spring: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration. Available online at: https://www.fda.gov/media/133880/download (accessed May 03, 2022).

Cho, Y. J., Thrasher, J. F., Reid, J. L., Hitchman, S., and Hammond, D. (2019). Youth self-reported exposure to and perceptions of vaping advertisements: findings from the 2017 international tobacco control youth tobacco and vaping survey. Prev. Med. 126, 105775. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.105775

Cullen, K. A., Ambrose, B. K., Gentzke, A. S., Apelberg, B. J., Jamal, A., and King, B. A. (2018). Notes from the field: use of electronic cigarettes and any tobacco product among middle and high school students - United States, 2011-2018. MMWR Morb. Mortal Wkly. Rep. 67, 1276–1277. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6745a5

Cullen, K. A., Gentzke, A. S., Sawdey, M. D., Chang, J. T., Anic, G. M., Wang, T. W., et al. (2019). e-Cigarette use among youth in the United States, 2019. JAMA 322, 2095–2103. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.18387

Depue, J. B., Southwell, B. G., Betzner, A. E., and Walsh, B. M. (2015). Encoded exposure to tobacco use in social media predicts subsequent smoking behavior. Am. J. Health Promot. 29, 259–261. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.130214-ARB-69

Do, E. K., O'Connor, K., Diaz, M. C., Schillo, B. A., Kreslake, J. M., and Hair, E. C. (2023). Relative increases in direct-to-consumer menthol ads following 2020 FDA guidance on flavoured e-cigarettes. Tob. Control 32, 779–781. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2021-057069

Erdem, T., and Swait, J. (2004). Brand credibility, brand consideration, and choice. J. Cons. Res. 31, 191–198. doi: 10.1086/383434

Evans, W. D., Price, S., and Blahut, S. (2005). Evaluating the truth brand. J. Health Commun. 10, 181–192. doi: 10.1080/10810730590915137

Facebook (2021). Advertising Policies on Prohibited Content for Facebook and Instagram: 4. Tobacco and Related Products. Available online at: https://transparency.fb.com/policies/ad-standards/dangerous-content/tobacco/?source=https%3A%2F%2Fm.facebook.com%2Fpolicies_center%2Fads%2Fprohibited_10 (accessed May, 2022).

Gammon, D. G., Rogers, T., Gaber, J., Nonnemaker, J. M., Feld, A. L., Henriksen, L., et al. (2021). Implementation of a comprehensive flavoured tobacco product sales restriction and retail tobacco sales. Tob. Control. 31, e104–e110. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2021-056494

Jackler, R. (2019). JUUL Advertising Over its First Three Years on the Market. Available online at: https://www.wbtw.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/22/2019/09/JUUL_Marketing_Stanford.pdf (accessed October 10, 2021).

JUUL (2018). JUUL Labs Action Plan. Available online at: https://www.juullabs.com/juul-labs-action-plan/ (accessed November 23, 2021).

JUUL (2019a). JUUL Labs Stops the Sale of Mint JUULpods in the United States. Available online at: https://www.juullabs.com/juul-labs-stops-the-sale-of-mint-juulpods-in-the-united-states/ (accessed November 23, 2021).

JUUL (2019b). JUULLabs Suspends Sale of Non-Tobacco, Non-Menthol-Based Flavors in the U.S. Available online at: https://www.juullabs.com/juul-labs-suspends-sale-of-non-tobacco-non-menthol-based-flavors-in-the-u-s/ (accessed November 23, 2021).

Kong, G., Bold, K. W., Morean, M. E., Bhatti, H., Camenga, D. R., Jackson, A., et al. (2019). Appeal of JUUL among adolescents. Drug Alcohol Depend. 205, 107691. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.107691

Kostygina, G., Kreslake, J. M., Borowiecki, M., Kierstead, E. C., Diaz, M. C., Emery, S. L., et al. (2021). Industry tactics in anticipation of strengthened regulation: BIDI Vapor unveils non-characterising BIDI Stick flavours on digital media platforms. Tob. Control 32, 121–123. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2021-056502

Kostygina, G., Tran, H., Schillo, B., Silver, N. A., and Emery, S. L. (2022). Industry response to strengthened regulations: amount and themes of flavoured electronic cigarette promotion by product vendors and manufacturers on Instagram. Tob Control 31, s249–s254. doi: 10.1136/tc-2022-057490

LaVito, A. (2018). Available online at: https://www.cnbc.com/2018/07/02/juul-e-cigarette-sales-have-surged-over-the-past-year.html (accessed October 12, 2021).

Miech, R., Johnston, L., O'Malley, P. M., Bachman, J. G., and Patrick, M. E. (2019). Trends in adolescent vaping, 2017-2019. N. Engl. J. Med. 381, 1490–1491. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1910739

Miech, R. A., Johnston, L., and O'Malley, P. M. (2019). Monitoring the Future National Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975–2018: Volume I, Secondary School Students. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan: Institute for Social Research. Available online at: http://monitoringthefuture.org/pubs.html#monographs (accessed November 22, 2022).

Myers, M. L., Muggli, M. E., and Henigan, D. A. (2018). Request for Investigative and Enforcement Action to Stop Deceptive Advertising Online Washington, DC: Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids.

O'Brien, E. K., Hoffman, L., Navarro, M. A., and Ganz, O. (2020). Social media use by leading US e-cigarette, cigarette, smokeless tobacco, cigar and hookah brands. Tob Control 29, e87–e97. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2019-055406

Pew Research Center (2018). Teens, Social Media & Technology 2018. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center.

Pew Research Center (2021). Social Media Fact Sheet. Available online at: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/social-media/?menuItem=b14b718d-7ab6-46f4-b447-0abd510f4180 (accessed November 23, 2021).

Rogers, T., Feld, A., Gammon, D. G., Coats, E. M., Brown, E. M., Olson, L. T., et al. (2020). Changes in cigar sales following implementation of a local policy restricting sales of flavoured non-cigarette tobacco products. Tob. Control 29, 412–419. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2019-055004

Rogers, T., Gammon, D. G., Coats, E. M., Nonnemaker, J. M., Xu, X., et al. (2022). Changes in cigarillo availability following implementation of a local flavoured tobacco sales restriction. Tob. Control 31, 707–713. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2020-056229

Romberg, A. R., Miller Lo, E. J., Cuccia, A. F., Willett, J. G., Xiao, H., Hair, E. C., et al. (2019). Patterns of nicotine concentrations in electronic cigarettes sold in the United States, 2013-2018. Drug Alcohol Depend. 203, 1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.05.029

Rostron, B. L., Cheng, Y. C., Gardner, L. D., and Ambrose, B. K. (2020). Prevalence and reasons for use of flavored cigars and ENDS among US youth and adults: estimates from Wave 4 of the PATH Study, 2016-2017. Am. J. Health Behav. 44, 76–81. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.44.1.8

Scutti, S. (2018). Juul to eliminate social media accounts, stop retail sales of flavors. CNN Health. Available online at: https://www.cnn.com/2018/11/13/health/juul-flavor-social-media-fda-bn/index.html (accessed July 26, 2020].

Soneji, S., Yang, J., Knutzen, K. E., Moran, M. B., Tan, A. S. L., Sargent, J., et al. (2018). Online tobacco marketing and subsequent tobacco use. Pediatrics 141, 2. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-2927

Twitter (2021). Tobacco and Accessories. Available online at: https://business.twitter.com/en/help/ads-policies/ads-content-policies/tobacco-and-tobacco-accessories.html (accessed November 20, 2021).

US Food and Drug Administration and US Department of Health and Human Services (2011). Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. Maryland: US Food and Drug Administration, US Department of Health and Human Services, Silver Spring.

US Food and Drug Administration and US Department of Health and Human Services (2016). “Deeming tobacco products to be subject to the Federal food, drug, and cosmetic act, as amended by the family smoking prevention and tobacco control act; Restrictions on the sale and distribution of tobacco products and required warning statements for tobacco products,” in Federal Register, 81.

Wang, T. W., Gentzke, A. S., Creamer, M. R., Cullen, K. A., Holder-Hayes, E., Sawdey, M. D., et al. (2019). Tobacco product use and associated factors among middle and high school students—United States, 2019. MMWR Surveill. Summ. 68, 1–22. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6812a1

Keywords: electronic nicotine delivery systems, tobacco industry, policy, marketing, Twitter, Instagram

Citation: Guillory J, Trigger S, Ross A, Lane S, Kim A, Nonnemaker J, Liu ST, Snyder K and Delahanty J (2023) Changes in industry marketing of electronic nicotine delivery systems on social media following FDA's prioritized enforcement policy: a content analysis of Instagram and Twitter posts. Front. Commun. 8:1274098. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2023.1274098

Received: 07 August 2023; Accepted: 23 November 2023;

Published: 11 December 2023.

Edited by:

Keryn E. Pasch, The University of Texas at Austin, United StatesReviewed by:

Jessica Castonguay, Temple University, United StatesEsther Agbaje, Mitchell Hamline School of Law, United States

Copyright © 2023 Guillory, Trigger, Ross, Lane, Kim, Nonnemaker, Liu, Snyder and Delahanty. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jamie Guillory, amFtaWVndWlsbG9yeSYjeDAwMDQwO3J0aS5vcmc=

Jamie Guillory

Jamie Guillory Sarah Trigger

Sarah Trigger Ashley Ross

Ashley Ross Stephanie Lane3

Stephanie Lane3