- Waseda Institute of Political Economy, Wseda University, Tokyo, Japan

This study examines how Japanese newspapers reporting the results of public opinion polls represent a unified picture of public opinion on environmental issues. Focusing on public opinion poll coverage, we argue that certain results are emphasized to the exclusion of others. To this end, this study analyzes articles and headlines of public opinion poll results on environmental issues published by three Japanese newspapers, the Asahi newspaper, the Yomiuri newspaper, and the Mainichi newspaper, from 1988 to 2010. In total, we located 64 articles that contain 179 headlines and subheadings. Findings suggest that the news coverage most often emphasized people's fears and concerns about environmental issues, followed by individuals' willingness to adopt environmentally friendly behaviors and practices, such as energy conservation and recycling. Overall, the headlines tend to give the impression that many respondents support this view. However, some media outlets that follow this trend selectively emphasize only one aspect of the poll results in their headlines without pointing out the existence of a conflict. They interpret poll results using second person or collective nouns to indicate the distribution of opinions. They then imply an overarching, unified public opinion that indicates a certain direction. This paper concludes that media representations of public opinion based on the results of Japanese public opinion polls on environmental issues legitimize existing political and economic structures and attribute responsibility for environmental problems to individuals.

1. Introduction

Studies have been conducted over the years on public opinion polls and the press, albeit not in abundance. We attend to one aspect of this association, probing how media channels use the results of public opinion polls to represent public opinion. Research in this area has for a long time questioned whether journalists accurately report public opinion polls (Broh, 1980; Brettschneider, 1997; Andersen, 2000). However, research projects have more recently adopted increasingly multifaceted approaches. For example, some studies have analyzed ideological and cultural aspects of the reporting of poll results by news media (Groeling, 2008; Searles et al., 2016). We represent the latter line of recent studies in our approach as we probe the representation of a unified image of public opinion as another aspect of the ways in which the media represent public opinion in reporting polls. The critical literature on public opinion polls highlights several problems regarding polling as a method of determining public opinion, stressing its susceptibility to ideological biases (e.g., Bourdieu, 1993). Conversely, researchers who view the outcomes of human activity as a cultural form consider both public opinion polls and the press to denote varied forms of the representation of public opinion (e.g., Lewis, 2001). We accept the idea that polls and the press are cultural forms that contribute to the representation of public opinion. This acceptance raises a significant question about the kind of image of public opinion that is created through poll coverage.

Our study analyzes the ways in which a unified image of public opinion is represented in newspaper coverage of environmental polls. Previous studies that have analyzed the coverage of public opinion poll results have examined news coverage on electoral polls with horse race journalism and the ways in which the press represents public opinion, including the treatment of poll results during election campaigns. On the other hand, little attention has been paid to how issue polls, which are polls focused on a single issue or agenda, are reported. As a primary purpose, our study scrutinizes the representation of a unified image of public opinion in the coverage of issue polling. In so doing, we also deliberate on the media narratives that function to represent a unified image of public opinion by considering the attribution of responsibility and the measures adopted to address it in polling reportage. We critically discuss our results, indicating that media representations of public opinion can exert significant politico-social consequences.

2. Context and method

2.1. Opinion polls and poll reporting

The press is deeply involved in the social construction of public opinion. Herbst (1998) identifies four elements as most important in the social construction of public opinion at the macro level. First, the form of the democratic model, e.g., representative democracy, tends to determine how people think about public opinion. Second, the techniques and methodologies available for assessing public opinion, i.e., public opinion polls are one of the forms of expressing opinions. Third, the rhetoric of leaders, i.e., what the political elites consider to be public opinion, and the fourth, public opinion as presented by journalists, are mentioned. Journalism and the press play an important role in shaping our concept of public opinion. This is because once public opinion, whether in polls or in the rhetoric of leaders' speeches, is shared with society through the filter of the mass media. Therefore, what the media present as public opinion and how they present it is an important theme for the social construction of public opinion at the macro level.

Several researchers have focused on and studied the way of media representation of public opinion. According to Beckers (2020), there are five categories of the way that media report public opinion: vox pops, protests, social media, inference about public opinion, and reporting opinion poll (Beckers, 2020). Vox pops, protests and social media are to report the voice of people, pulling attention of the recent research (Brookes et al., 2004; Lewis et al., 2004; Beckers et al., 2018; Beckers, 2020). Vox pops is to directly report the voice of people in street, often featured in television news (Beckers, 2020). Protest is to report the voice of individuals interacting politicians (McLeod and Hertog, 1992). Social media is to report the voice of people and reaction of it posted on social network service like Twitter or Facebook (McGregor, 2019). In contrast with these categories, inference is to report the inspection of media elites like news anchor or reporter, and political elites like politician and bureaucrat, without solid ground (Brookes et al., 2004; Beckers, 2020). Finally, the critical difference between reporting opinion poll and other categories is the object of reporting the statistical result of opinion poll based on statistics, which aligns with two of the four elements highlighted by Herbst (1998).

Bourdieu (1993) asserted that public opinion polls construct a unified public opinion and function on three implicit assumptions: that everyone has some opinion, that all opinions are equivalent and accountable, and that a consensus exists that it is natural to ask questions on issues (p. 149). Bourdieu thus contends: “That is the fundamental effect of the opinion poll: it creates the idea that there is such a thing as unanimous public opinion, and so legitimizes a policy and strengthens the power relations that underlie it or make it possible” (p. 150).

Lewis (2001) argues similarly that public opinion polls encompass wide-ranging exclusions and that public opinion as indicated by poll results is a manufactured thing (p. 28). However, Lewis adopts the position that public opinion polls should be viewed as a form of representation. First, the social construction of unified public opinion represents a profoundly complex process. Therefore, unified public opinion cannot be attributed to any society solely through the examination of opinion polls. Bourdieu's point is valid because it illuminates the political nature of public opinion polls. Nevertheless, it would be slightly simplistic to cognize that unified public opinion could emerge merely through the conduction of polls. Lewis (2001, p. 12) encourages us to view public opinion represented by the media that disseminate it in society, arguing that it is worth investigating varied expressions of public opinion rather than exploring one genuine articulation of public opinion.

Some researchers aim to understand the characteristics of media as represented by news organizations, focusing on the practices of news selection and emphasis. Groeling (2008) and Searles et al. (2016) have found that ideological biases could influence media selections of poll results reported during election campaigns. Larsen and Fazekas (2020) have also revealed that media poll coverage places news value on change and highlights this aspect, notwithstanding whether such change is calculated within the margin of error. These existing studies evidence that the media select and emphasize certain facets of poll results in their reports.

News organizations appear to reflect the characteristics of selection and emphasis; they also seem to manufacture consensus through the manipulation of public opinion polls, intentionally or otherwise. Lewis (2001) identified the features of media poll coverage reflecting the above-stated assumptions of poll operations critiqued by Bourdieu (1993, p. 151). For example, Lewis noted that media poll coverage tends to interpret changes in a section of respondents as the general transformation of public opinion (pp. 59–60), hide conflicts discovered in poll results, ignore attributional information (p. 65), and use the second- and third-person voice (p. 66). Lewis did not explicitly claim the deduction but these findings signify that media poll coverage is oriented toward the construction of an image of unanimous public opinion. Lewis also criticized the so-represented unified image of public opinion, which differs from the distribution of individual opinions revealed by other polls and legitimizes discourse and policies posited by the political elite (p. 68). Bourdieu (1993, p. 150) described precisely this eventuality as “public opinion on our side.”

However, scant studies apart from Lewis's (2001) have analyzed the media representation of unified public opinion in covering polls. Lewis and Bourdieu attended to issue polls related to policy issues, but most other existing studies have focused on electoral poll—horse race—coverage in election campaigns. Public opinion polls can be broadly divided into two categories based on their interest in ascertaining approval ratings, electoral poll, or discerning public concern about specific policies or social issues, issues poll. Polls on approval ratings rely essentially on the structure of competition between candidates. Some early studies of poll coverage have primarily centered around horse race journalism and the accuracy of poll reporting, as well as the provision of information regarding polling methodologies (Broh, 1980; Brettschneider, 1997; Andersen, 2000; Patterson, 2005).

Researchers must also analyze overall reporting patterns, given debates on wide-ranging policy issues during election campaigns, for instance, questions pertaining to first-level contentious issues, such as identifying the most important problems. The outcomes of such inquiries serve the purpose of understanding the priorities individuals assign to various agendas, and can be interpreted as indicators of social integration or fragmentation. Social integration is inferred when people share common issue of contention, whereas fragmentation is inferred when responses diverge (Edy and Meirick, 2019). The prioritization of the most important problems deprives people of the opportunity to express their views on the sub-issues of each issue (responsibility, choice of countermeasures, etc.), and the coverage of the results is unlikely to include media representations of a unified public opinion. Conversely, Bourdieu (1993) and Lewis (2001) discussed issue polling on certain policy and social issues. Bourdieu's perspective emphasized the existence of as many public opinions as there are policy issues. Flagging a consensus on a particular policy contributes to policymaking. Such a unified image of public opinion is elevated to the status of common values and serves as a presupposition of national identity (Eriksen, 2005, p. 343).

This article is based on a case study of the coverage of public opinion polls on environmental issues in Japanese newspapers. We report the results of our fundamental content analysis inspired by the concept of responsibility and attribution and discuss the implications. The investigation revealed that the media's coverage of poll results on societal issues weaves narratives that convey the image of unified public opinion. Specifically, our study focused on two aspects: media selection and emphasis, and media interpretation of poll results. We analyzed the headlines of news articles on issue-based polls to identify the aspects of the poll results that attracted media attention and were emphasized. We also examined media interpretations of the poll results. We further evaluated how the media turned a report of poll results into a story by narrating public opinion construed from the poll results. We employed basic content analysis for the scrutiny of this storytelling aspect to identify media interpretations before discussing the effected construals.

2.2. Environmental issues, media, and public opinion

This present study scrutinized the reporting of polls on environmental issues, which denote a media-associated social concern: media reportage and environmental topics have become deeply intertwined. Media channels have increased their coverage of environmental issues and have attracted social attention to such concerns (Downs, 1972). In fact, the increasing coverage of environmental issues by media outlets has elevated environment-related problems that are not directly experienced by many people to the status of public social concerns (Zucker, 1978; Ader, 1995). Such environmental worries include global problems such as climate change (Sampei and Aoyagi-Usui, 2009). This increasing media attention reflects a phenomenon of the critical discourse moment (Chilton, 1987) and offers societies opportunities to elicit social debates, demand responses, and seek consensus on environmental issues (Carmichael and Brulle, 2017).

In this process, the media share with society the frameworks concerning the definition, responsibility, and strategies related to environmental issues. Media encourage systematization to render events comprehensible (Gamson and Modigliani, 1989), by establishing a pattern of information selection, emphasis, and exclusion (Gitlin, 1979, p. 7). Such systemization seeks to define a problem, establish its causes, describe attitudes toward the issue, and tender justifications toward responses (Entman, 1993). The instituted frameworks encapsulate how a societal issue emerges and determine who bears responsibility for its addressal (Iyengar, 1990). The established systems could become particularly entrenched and long-lasting, becoming normalized and accepted as natural; at this stage, they can restrict individual thoughts and actions vis-à-vis the issue at hand (Carragee and Roefs, 2004).

The formation of consensus on environmental issues by the media is crucial to their resolution because public opinion functions to bolster governmental action (Guber, 2003, p. 2). By eliminating uncertainties surrounding environmental issues and emphasizing their dangers while clearly attributing responsibility, a consensus for addressing the problems can be established, though the opposite scenario is also possible. The Swedish media emphasize the threat of climate crisis and exclude uncertainties about climate change, legitimizing the allocation of responsibility to governments or international institutions to respond to the issue. The Swedish media assigned the onus for the response strategy of mitigation to international bodies and assigned the task of undertaking the strategy of adaptation to the national and regional governments as a “global responsibility” (Olausson, 2009). As a result, media houses have endeavored to represent a unified “us” to signify their accord in broadcasting public opinion about responding to climate change risks as an aspect that shapes the identity of the EU (p. 7). This framework of power relationships subsequently became fixed and naturalized (Olausson, 2009).

In contrast, the US media houses have emphasized uncertainty, obscured the attribution of responsibility, and generated conflicts in public opinion, thus delaying the institution of countermeasures to environmental difficulties. Political elites in the United States have emphasized the uncertainty of climate change and global warming, and American media outlets have competitively followed this drama, reporting and representing the clashing opinions ranging from skepticism about climate change to the scientific community's consensus on anthropogenic global warming (Boykoff and Boykoff, 2004; Boykoff, 2007). Such media-represented disagreements between the political and scientific elite have hindered the development of a broader concurrence on climate change in the American public (McCright and Dunlap, 2003, 2011). Such failures in forming consensus legitimize the United State government's inaction on climate change and slow down the advancement of a global resolution.

Even if the mention or exclusion of uncertainty affects subsequent attribution of responsibility, who is attributed responsibility is another point worth noting. Outside of the aforementioned studies, media outlets frequently address the attribution of responsibility at the state or government level in climate change coverage (Dirikx and Gelders, 2010; Liang et al., 2014). Certainly, it is not surprising that the responsibilities and roles of international organizations, states, and local administrations are emphasized in responding to global environmental issues. However, although frameworks attributing responsibility for addressing environmental issues to individuals exist in the media, their prevalence is relatively limited (Olausson, 2009; Dirikx and Gelders, 2010).

During the 2000s, in advanced countries and international organizations, a framing based on the idea of individual responsibility for addressing climate change has gained prominence. In the UK, frameworks such as “I will if you will” (Sustainable Consumption Round Table, 2006) have been highlighted, advocating that sustainable consumption and individual behavior can contribute to solving climate change and achieving a sustainable society (Shove, 2010). The Australian government also launched the climate change information campaign “Be Climate Clever” in 2007, encouraging people to reduce energy consumption (Kent, 2009). The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) has also addressed individual behavior (United Nations Environment Programme, 2008, p. 46–47) and initiated initiatives such as “Kick the habit” to call for action. Currently, the emphasis on “individual actions” contributing to climate change mitigation remains (Dietz et al., 2009; Wynes and Nicholas, 2017).

However, frameworks attributing responsibility to individuals have been subject to criticism. This notion of individualizing responsibility is derived from neoliberalism (Kent, 2009; Bloom, 2017). Maniates (2002) referred to such frameworks as “the individualization of responsibility,” arguing that when responsibility for environmental issues becomes individualized, it diminishes the collective consideration of how to change institutions and political power that constrain people's actions. By making it seem that solving environmental issues can be achieved through individual actions alone, the idea of individualizing responsibility conceals the need for more fundamental societal structural changes (Shove, 2003, p. 9).

Indeed, eco-friendly consumption might have been embraced by politically active individuals as one of their environmental actions (Willis and Schor, 2012). However, such actions ultimately remain exclusive and individualized consumption and may not necessarily spread throughout society as a whole (Baumann et al., 2015). In fact, considering the continuous increase in material and resource consumption and the resulting environmental burden in Canada and the United States, it is unlikely that such individual consumption behaviors will have significant effects on solving environmental issues (e.g., U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2017; Government of Canada, 2018).

In summary of this section, firstly, media representation and media-driven consensus formation on environmental issues strongly influence responses to such problems and affect how the responses are legitimized. Therefore, the reporting of opinion polls on environmental issues represents an effective case study topic through which we can examine the media representations of unified public opinion. The second point is that the media not only represent public opinion as a consensus on environmental issues but also create a sense of responsibility that becomes ingrained and unquestionable, perpetuating existing power relationships. It is crucial, therefore, for poll coverage to be analyzed from the perspective of the attribution of responsibility. Thus, as the secondary objective, the present study examines who is attributed with what responsibility by the media coverage of environment-related issues polls. It also reveals the public opinion image that is portrayed by probing the measures the media propose.

2.3. Japanese news media, opinion poll, and environmental politics

We analyzed the reporting on opinion polls in Japanese national newspapers, a relevant case for the current topic of study because national Japanese newspapers are deeply committed to public opinion polling. Japanese mass media companies conduct opinion polls because they consider opinion polling a tool that reflects the views of the citizenry on the business of governance as well as elections (Sato, 2008). Japan's media companies incorporate internal polling divisions that enable them to conduct surveys and report the results. Conversely, mass media groups in other countries generally purchase and report the results of opinion polls conducted by third parties (for example, Gallup in the US or YouGov in the UK). National Japanese newspapers conduct opinion polls and report poll results, indicating their firm commitment to the representation of public opinion. The analysis of the reportage of opinion polling by national Japanese newspapers represents an effective case for their representation of unified public opinion.

Of course, the Japanese media functions significantly in tackling environmental issues. Japan's rapid economic growth in the 1960s was accompanied by severe pollution, and Japanese mass media brought this serious problem to public attention in the 1970s (Stearns and Almeida, 2004). The volume of media coverage of climate change increased from the 1980s in the context of political events (Nagai, 2017), and the media amplified public concerns about environmental issues (Sampei and Aoyagi-Usui, 2009). The rise and fall of the Japanese media have been linked to political events.

The Japanese government has sought to establish its leadership in international environmental politics. In the 1970s, Japan overcame serious environmental pollution through stringent regulation and the deployment of environmental technologies. Japan became more active in the 1990s in contributing to international collaborations in the domain of environmental protection. Underlying such activities is the Japanese government's desire to restructure and counter Japan's adverse international image as an economic powerhouse with limited international contribution (Ohta, 2000). The Japanese government acted as a mediator between European countries and the United States and took on a persuasive role during negotiations of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (Pajon, 2010). In 2008, the Japanese government proposed the goal of halving greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. Further, Japan hosted the G8 Hokkaido Toyako Summit in July 2008, for which the global environment and climate change represented a primary agenda item and the post-Kyoto framework was a topic of discussion.

This linkages between media and politics in Japan could indicate the possibility of the media representation of unified public opinion representation in covering opinion polls. For example, unlike the media skepticism prevailing in the United States, Japanese mass media consistently follow the consensus of the elite scientific community and eliminated uncertainty (Asayama and Ishii, 2014). Japanese media that support a proactive attitude could avoid domestic confrontations. Such contexts suggest that Japanese media outlets are more likely to represent a unified image of public opinion, just as Olausson (2009) has evidenced for the European media.

2.4. Method and data

2.4.1. Material

We conducted content analysis on three Japanese national newspapers, Asahi, Yomiuri, and Mainichi, to reveal the media representation of a unified public opinion on environmental issues. These Japanese broadsheets denote daily newspapers with the largest circulations and thus deliver a fairly comprehensive representation of the Japanese mainstream press. The three newspapers subscribe to different political ideologies (McCargo, 1996) but do not operate their ideologies in the coverage of environmental issues (Asayama and Ishii, 2014). We collected all articles containing the keywords “environment” (kankyou) and “public opinion” (yoron) from the digital archives of Japanese newspapers from 1988 to 2010, when Japanese climate coverage continued to increase (Nagai, 2017), to locate reporting of opinion polls. Note that we could not find any articles after 2010, so this is the period when the Japanese media paid attention to public opinion on the environment. In total, we located 64 articles after excluding unrelated pieces (Asahi: 20; Yomiuri: 29; Mainichi: 15).

2.4.2. Method

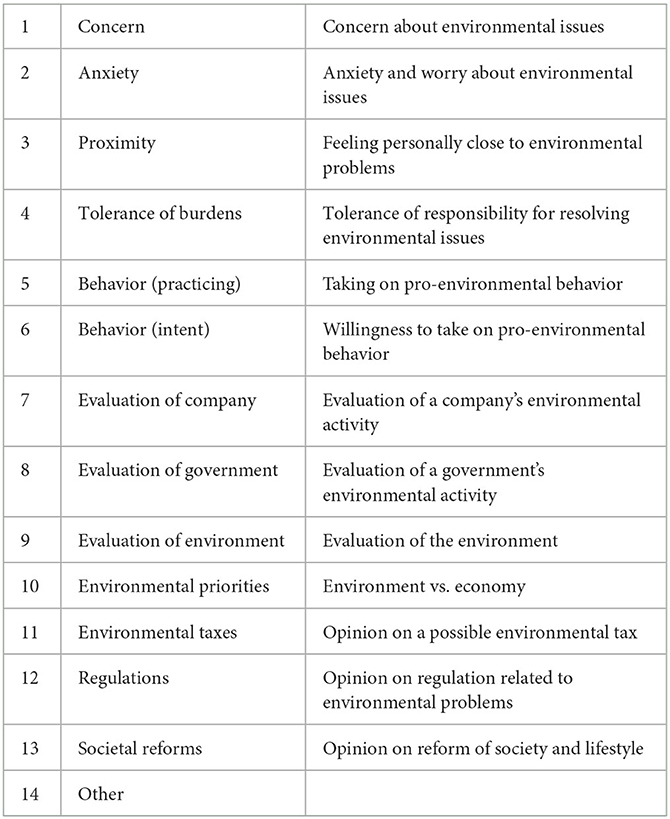

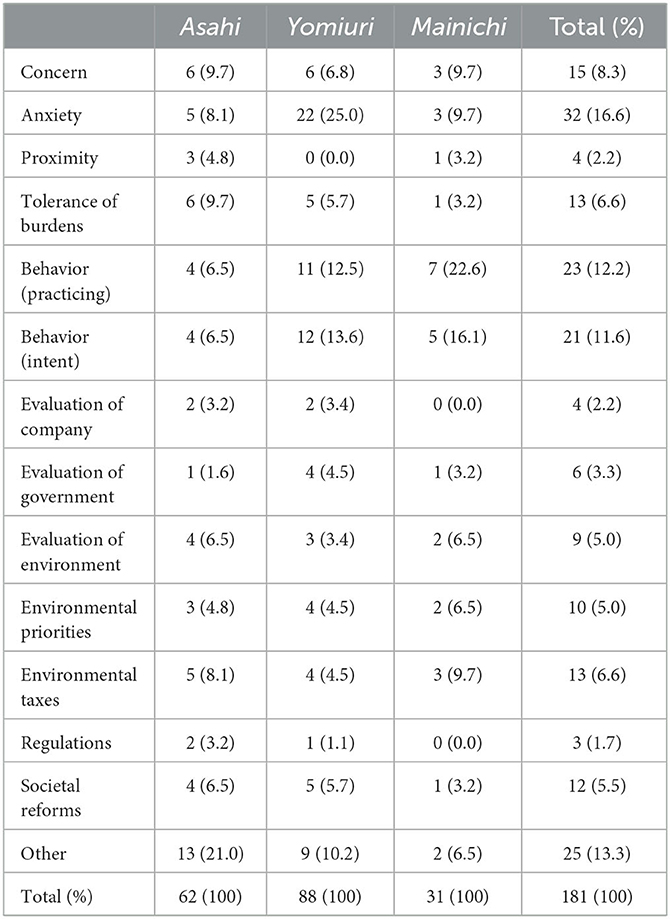

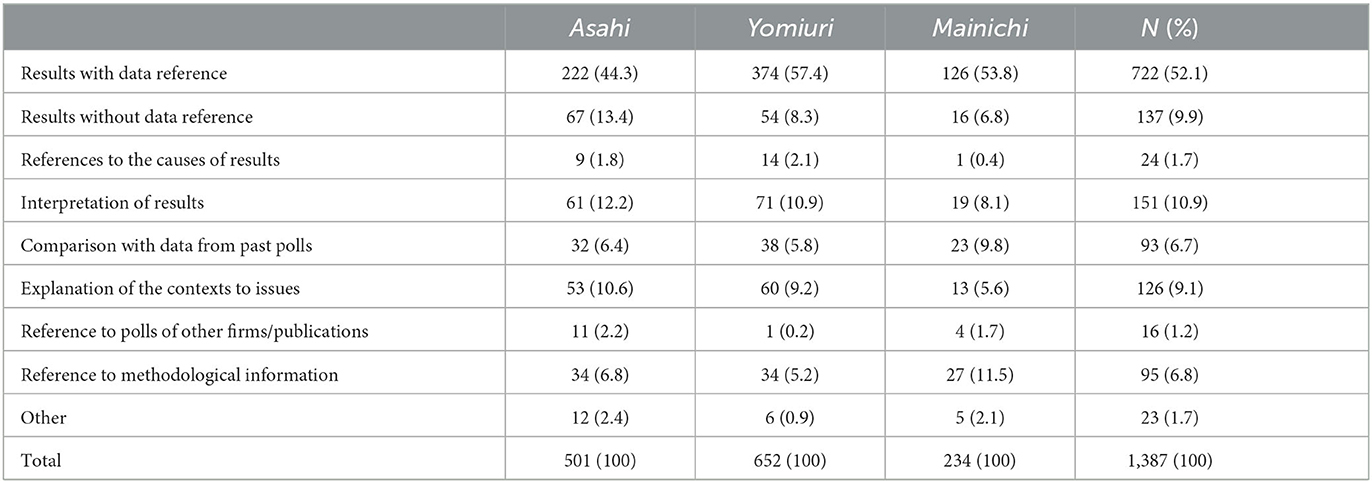

We analyzed the selection and emphasis of the stated coverage to address the media representation of a unified public opinion, focusing on three aspects: headlines and subheadings, the impressions created by them, and the media's interpretations of poll results. Headlines function crucially in conveying the most important information to the reader. Headlines narrow down the number of emphasized facets of poll results because they “should be written to inform the reader as to what is most important about the story” (Trumbo, 1996, p. 272). The study's analysis also included subheadings to capture the full picture because subheadings are often used in conjunction with headlines to convey additional information. Japanese newspapers employ discrete font sizes for their article headlines and subheadings. We identified a total of 179 headings, which were grouped into 14 categories as shown in Table 1. Of these, only two required multi-coding, resulting in the final count of N = 181.

Besides evaluating which findings were selected and highlighted by the Japanese media, we examined the impressions created by headlines to infer the effects of the headlines on the perceptions of readers with regard to public opinion. Readers do not always read entire newspapers. Most readers scan headings and read the articles that attract their attention (Holsanova et al., 2006). Therefore, headlines function crucially in shaping the impressions of readers. As previously mentioned, the reporting of poll results influences the perceptions of readers vis-à-vis public opinion. Readers exposed to headlines that tend to emphasize the majority view while ignoring minority opinions may identify their position within the distribution of the stated attitudes and may feel relieved to consider themselves in the majority. However, readers whose views are in the minority could try to integrate with the majority opinion or could be silenced in despair. This practice can trigger a spiral that propagates the majority viewpoint (Noelle-Neumann, 1974). Headlines could conceal existing conflict by selecting and emphasizing only one aspect of the division of public opinion on an issue, even if both opinions are subsequently mentioned within the article. Of course, newspapers do not directly represent a unified image of public opinion by emphasizing the majority perspective or highlighting only one side of public opinion in their headlines. Nevertheless, the headline emphasis functions as a gear in the representation of a unified image of public opinion. The media appear to simply report the facts but media channels play a role in shaping impressions of public opinion in their wide readership by presenting poll results understandably and credibly (Krippendorff, 2005, p. 144). We framed a question to reveal the predisposition of the impressions created by headlines: “Does this headline or subheading deliver the impression that many people or few individuals hold this opinion?” The collected newspaper headlines were classified into two categories based on our responses to this question.

We investigated how media companies interpret and present poll results to construct narratives about public opinion. Poll data provides information about the distribution of opinions; however, if a news article lists the numbers as-is, it becomes a research report and not a story. Media outlets create narratives that turn events or data into a story that makes sense to its audiences (Gamson et al., 1992, p. 385). We focused on two of the distinct features highlighted by Lewis (2001) in our observations of the process of transforming poll results into a news story. First, media interpretations of data often portray a change in a select group as a transformation occurring in the entire population. Second, the media use second- and third-person pronouns and collective nouns such as public or people to create their narratives and depict the image of unified public opinion (p. 66).

We identified such media interpretations using qualitative analysis, for which we located 151 sentences from the aggregate of statements (N = 1,387) related to the interpretation of results into categories based on previous studies (Smith and Verrall, 1985; Brettschneider, 1997; Hardmeier, 1999; Andersen, 2000), as presented in Table 2. This analysis of the media's interpretations of poll results aimed to reveal how the media represent and reinforce a particular narrative about public opinion.

We assessed intercoder reliability by calculating Krippendorff's alpha for each analysis using a test sample of data for three coders: the first was computed as α = 0.7983 (0.7035 ≤ α ≤ 0.8814); the second, α = 0.8139 (0.7022 ≤ α ≤ 0.9256), and the third, α = 0.8235 (0.6427 ≤ α ≤ 0.9553) (Hayes and Krippendorff, 2007).

3. Result

3.1. Headlines of articles reporting poll results reporting on environmental issues

The results of the present investigation revealed that the media representation of public opinion on environmental issues is strongly related to the degree of concern and anxiety people feel about environmental issues. Headlines most selected and emphasized the public opinion of anxiety about environmental issues at 16.6%, followed by concern at 8.3%. In total, these terms accounted for 24.9% of the relevant headlines: for example, “Strong concerns over damage to the Earth” (Yomiuri, 18 May 1989), “8 in 10 say worried about global warming” (Yomiuri, 30 July 1990), “54% are anxious about global warming” (Asahi, 8 April 2002), “Abnormal weather raises fears” (Mainichi, 20 September 2002), “71% are worried about global warming” (Yomiuri, 5 June 2007). Such emphasis on the data evincing anxiety and concern about environmental problems sensed by most respondents implies that the issues must be resolved and amount to a call for action at the national level.

Japanese national newspapers significantly focus on solutions centered on individual actions. This predilection was evident from the emphasis placed on adopting pro-environmental behavior (12.2%) and demonstrating a willingness to engage in such behavior (11.6%), which together accounted for 23.8% of the headlines. Examples of such focus on personal responsibility can be seen in headlines such as “six out of 10 recycling” (Yomiuri, 5 June 1997), “87% say their air-con usage is moderate” (Asahi, 7 May 2007), “67% want to use Bio Fuel,” “70% now conserving water and energy” (Yomiuri, 5 June 2007), and “78% separating trash; 72% saving water” (Yomiuri, 27 June 2008).

Apart from individual behavior, we found that the Japanese media emphasized a high public willingness to accept burdens (6.11%). For example, we noted headlines including statements such as “Even if it is inconvenient, 50%” (Asahi, 21 June 1997), “86% accept lowering the efficiency in living” (Yomiuri, 9 February 1992), and “Even if it makes life inconvenient,” “77% want environmental protection” (Yomiuri, 10 January 2001). Such headlines convey that the majority of Japanese public opinion is willing to take responsibility for environmental issues as individuals. Certainly, such emphases could encourage individual commitment to environmental responsibility.

Viewed critically, however, these results suggest that Japanese national newspapers present individual behavior as their primary in-house solution to environmental problems and push social and political activism to the fringes of public opinion. Compared to individual action, the headlines of Japanese national newspapers do not emphasize government and corporate responsibility in their poll coverage of environmental issues. It is rare to see headlines that hold corporations accountable (2.2%), such as “60% believe businesses' energy efficiency efforts insufficient” (Asahi, 1 April 2002) and “76% of the responsibility for product disposal lies with companies” (Yomiuri, 5 June 1997). Similarly, opinions holding the government responsible are seldom featured (3.3%), such as “Citizens want a proactive stance from government” (Asahi, 7 January 2008) and “63% do not rate government actions highly” (Yomiuri, 21 October 2004). Such headlines would be published more often if Japanese newspapers placed pressure on elite quarters to serve the objective of reflecting public opinion in politics.

First, Asahi and Yomiuri have both probed public evaluation of the government only twice in around 20 years; Mainichi has only done it once and without featuring it as a headline. Similarly, Regarding Asahi has posed questions seeking evaluations of corporations twice in the above-stated time, while Yomiuri and Mainichi have abstained from raising such queries. This finding indicates that the newspapers are not willing to hold corporations or the government responsible from the initial stage of conducting in-house opinion polls.

Changes to personal behavior may be necessary for solving environmental problems but voluntary individual behavior is less efficient and effective than modifications to regulatory and administrative frameworks. In fact, Japan has overcome serious air and water pollution in previous decades by instituting strict regulations (Stearns and Almeida, 2004). Such historical improvements prove the efficiency and effectiveness of implementing new regulations and laws for environmental protection. Our results indicate that Japanese national newspapers exclude the role of people taking political actions to fight against environmental problems in their opinion poll coverage; rather, they tend to individualize the responsibility for environmental problems.

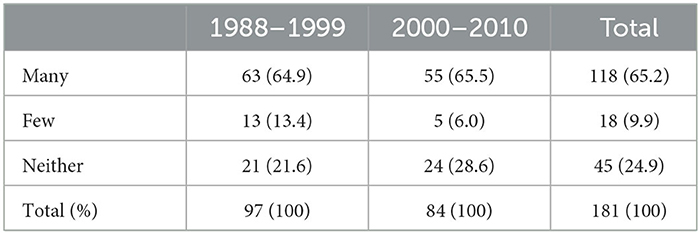

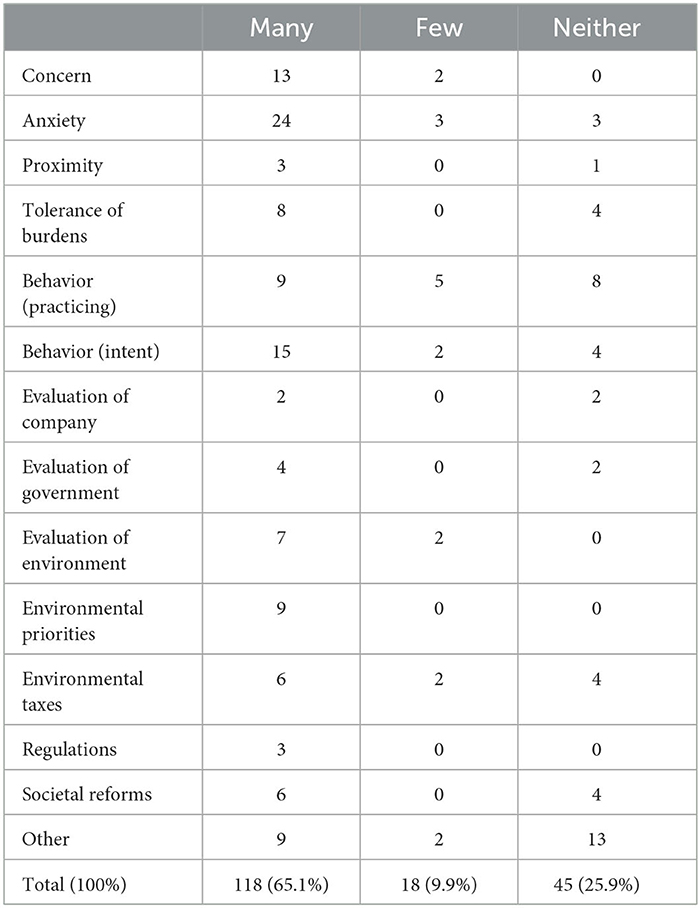

3.2. Headline impressions

Japanese newspapers consistently impart to readers the impression that the majority of the population supports a certain idea: 65.2% of the headlines deliver the notion that many people hold an opinion when only a few people have indicated it (Table 3). This finding is consistent across all headline categories established for this study (Table 4). The results and the examples noted in the previous section allow us to claim that overall, the relevant headlines of major Japanese newspapers have emphasized that many of their respondents are concerned and anxious about environmental issues and are willing to act or already implement environmentally friendly behavior in their homes.

Of course, the majority opinion has the right to decide in a democratic society, and presenting the majority view as the headline should not be problematic. However, questions may be raised if only one side of a divided opinion is featured in the headlines by the media following this trend of poll coverage. Does such selection and emphasis suggest dishonesty in the media's act of reporting poll results? Conversely, should this treatment be viewed as a result of the media selecting results aligning with a particular climate of public opinion?

Of the three newspapers, Asahi appears to particularly conceal the conflict indicated by poll results related to the burden of environmental protection and the issue of environmental taxes. Asahi asked the following question about the tolerance of such a burden in 1990,1 1997, 2002, 2007, and 2008:

Q: “Do you mind if your lifestyle becomes less convenient than it is now to prevent the global environment from getting worse? Or would that trouble you?”

A: “I wouldn't mind” or “I would be troubled”

Asahi used the headline “‘Even if it's inconvenient', say 50%” (21 June 1997) along with another emphasizing the absence of any change after a decade: “No change from 10 years ago−51% say inconvenience is fine” (7 January 2018). Read on their own, the headlines impart the impression that many people are willing to accept the burden of environmental protection. However, the actual poll results show a split opinion among the respondents. In 1990, 48% of the respondents answered “I wouldn't mind” and 46% asserted “I would be troubled.” In 1997, this comparative value was 50% and 44% and in 2002, it was 49 and 48%. Further, the outcomes were 51 and 43% in 2007, and 51% and 44% in 2008. From a statistical standpoint, these results evidence a clear distribution of opinions into two large groups. The distribution of opinions remains largely unchanged, and the headline “No change over 10 years–inconvenience would be a problem, say 44%” would have been equally true. Incidentally, in displaying its in-house poll results, Yomiuri did not disclose any split opinions with the headline “77% ‘protect the environment' even if it makes life inconvenient” (Yomiuri, 10 January 2001). Mainichi did not query burden acceptance.

Asahi displayed the same tendency in headlines on its polls on environmental taxes. An Asahi poll inquired intermittently whether respondents approved or disapproved of an environmental tax. In 2002, 44% of the respondents approved of the notion, while 45% disapproved. Of the headlines in Asahi about the results of this poll over the years, only one reflected this division in opinion: “Opinion divided on environmental tax” (Asahi, 8 April 2002). The other headlines emphasized only the result in favor of the tax. In the 2004 poll on this issue, 37% of the respondents approved of the idea, while 50% disapproved. However, the headline read “37% in favor of introducing an environment tax” (Asahi, 1 December 2004). Half the respondents (50%) to the 2004 Asahi poll selected the disapprove option but Asahi excluded this result from the headline. In the 2007 poll, 48% of the respondents approved of the environmental tax and 41% disapproved. Asahi noted the change in its headline: “Support for environment tax rises to 48%” (Asahi, 7 June 2008).

Yomiuri's coverage of the 2004 and 2007 public opinion polls evinced that most respondents favored the environmental tax, and the headlines only highlighted the side in favor. However, a 2005 article reporting the results of a government poll carried the headline “Opposition outweighs support for environmental taxes” (5 June 2005). Mainichi reflected both sides of the poll results in its headline: “Environmental Tax: Nearly Equal in Support and Opposition” (Mainichi, 4 July 1992) and “32% oppose the introduction of environmental tax, 24% approve” (Mainichi, 2 October 2005).

This finding suggests that the selection and emphasis of poll results can create impressions in readers that differ from the actual poll results. We confirm Lewis's point about the absence of conflict in public opinion coverage of policy issues.

3.3. Interpretation of poll results

We applied the coding rules presented in Table 5 to locate sentences in the articles related to the interpretation of poll results and categorized all sentences accordingly. Our analysis revealed 151 sentences referring to interpretation, including the implications and meanings of poll results. As discussed above, the results of opinion polls evince only the distribution of opinions from which we can infer the distribution of opinions in the population of Japan. However, the examination of these 151 sentences revealed that Asahi and Yomiuri used the third-person and collective nouns to interpret poll results. For example, “(The results) highlight citizens' high degree of concern about the global environment” (Yomiuri, 2 May 1988), “(The results) highlight public feeling that the whole nation should implement countermeasures” (Asahi, 1 April 2002), “Our opinion poll clearly shows a public worried about the global environment” (Asahi, 8 April 2002), “You can see that the people worry deeply and take seriously the future of the global environment,” and “Japanese people felt vaguely insecure about the future of the global environment 16 years ago; they are now developing a sense of impending crisis” (Yomiuri, 27 June 2008). Mainichi also used the term “Japanese” once to interpret poll results in comparison to polls conducted in Europe (Mainichi, 2 May 1988). Japanese national newspapers integrate the poll results into a broader national perspective by using words like nation, public, or people. These words thus function as a device that binds together several subgroups within the society to depict a unified image of public opinion.

In our analysis of 22 years of poll coverage, we found that Japan's newspapers delineated the narrative of changing environmental attitudes articulated by the Japanese people. In terms of Larsen and Fazekas' (2020) statement on media focus on change, it is not a story of change over a short period; it is a story of change over a longer period. The following symbolic interpretation in Yomiuri sums up several previous polls:

the Japanese people, who had only felt a vague sense of worry about the future direction of the global environment, now feel a sense of impending crisis… it isn't all pessimism, as having discovered the meaning of individual actions aimed at climate protection, we are now positively striving to co-exist with nature (Yomiuri, 27 June 2008).

Japanese mass media has thus constructed a major, long-term narrative of the image of public opinion vis-à-vis environmental issues.

4. Discussion

This study analyzed the reporting of poll results on environmental issues by Japanese national newspapers, revealing the media representation of the image of unified public opinion. Japanese newspapers have consistently selected and emphasized specific aspects of public opinion: the concern and anxiety and personal pro-environmental behavior of the public. In so doing, they have imparted the impression that many people support environmental protection initiatives. The newspapers have created a climate of public opinion by portraying the Japanese as a people with high environmental awareness. Any poll results that counter this sense have tended to be excluded from the newspaper headlines, for instance, a reluctance to bear the burden of environmental protection. Moreover, the newspapers used second-person and collective nouns such as nation, public, or people to convey the attitudes of some respondents as characterizations of public opinion as a whole. Through such selections, emphases, and interpretations, the newspapers have attempted to portray a unified image of the public opinion articulated by the “high environmentally conscious Japanese.”

In positive terms, the poll coverage we have seen has indicated that the Japanese people are highly environmentally conscious, are motivated to take eco-friendly actions, and are actually undertaking some desired actions. This finding implies that the Japanese people harbor a positive attitude toward solving national, and by extension, global environmental problems. However, the secondary results of this study indicate that a unified image of Japanese public opinion on environmental issues is within a framework of the individualization of responsibility. The focus of public attention has shifted from holding corporations and governments accountable to individuals. While the trend of individualizing responsibility for environmental issues has been observed internationally in the 2000s, the secondary findings of this study have revealed that this process extends to the reporting of opinion poll results in Japan. In reporting the news, the mass media tend to focus on stories about individuals rather than about large social, economic, or political structures (Bennett, 1996). Placing the responsibility for social problems on individuals restricts the behavior of people and conceals the existence of societal structures and power relationships in which these problems are rooted (Murdock, 1973; Hall, 1977; Gitlin, 1979). Moreover, the individualization that occurs from considering possible solutions emanating solely from the actions of individuals in the private sphere prevents the institutional cognition of the issue and excludes solutions, like collective actions, related to the influence of social systems or power structures (Bellah et al., 1992; Maniates, 2002). It is unlikely that this image of public opinion can break through political inertia and rally people to action to solve global environmental problems and climate change.

The image represented by Japanese newspapers of public opinion on environmental issues appears idealized and fosters a consensus approximating such an idealization. Ideally, the Japanese people can live green lifestyles simply by actively undertaking personal pro-environmental behaviors such as separating trash for recycling or saving energy and water without needing any alternative political actions. This idealized image of ordinary people is also connected to the formation of national identity and the inculcation of the conception of what the Japanese people should be. People can thus internalize the image of public opinion on environmental issues as part of their national or personal identity. In turn, they could adopt the attitude of “let's do a little bit” to attain release from their anxieties about environmental issues, while environmental issues would continue to worsen outside their homes.

This nonpolitical imaging of public opinion may be common for environmental issues as well as public opinion reporting. By extension, it could also apply to news reporting in general. Public opinion is only a part of the background, divorced from politics, whether experts and newscasters speculate on the views of the citizenry projected as voices on the street or present it as an aggregated distribution of views. No news organization with a neutrality policy would want to report on an overly political and active public (Lewis et al., 2004, p. 163). Or, if the media do report, it may marginalize them as a protest group (McLeod and Hertog, 1992). However, this practice defeats the poll's ideal of reflecting the will of the people in politics. Considered a pseudo-referendum, the poll presents a large-format snapshot of the distribution of aggregated opinion at a particular time. The media attempt to recount a nonpolitical story by eliminating some portion of that big picture to construct an appealing narrative. This narrative is retrieved by existing social systems or power structures and even takes on a conservative aspect. It is not valid to exclude minority opinions just because the majority stands on one side, and the majority is not always right. This dilemma presents a challenge for news organizations: should they encourage social integration or display the division as-is in reporting poll results, and by extension, the results revealed by large-scale data? If news organizations segment their reporting and broadcast content along with the fragmentation of public opinion, it may further accelerate social fragmentation (Edy and Meirick, 2019).

The neoliberalism and individualism that now permeate societies most hinder the media from drawing a picture of public opinion that questions the responsibility of existing economic and political structures in reporting the results of public opinion polls on environmental issues. These prevailing ideologies whisper that the root of the problem is vested in individual behavior and that the problem-solution must also be found in individual behavioral changes. However, an individual's only action of choice is limited to the selection of the goods and services offered for personal use. Such restricted options can only scantly influence the watershed emergent in an increasingly globalized and complex supply chain.

Can we envision poll coverage portraying the individual belief that environmental difficulties are rooted in existing social structures, while also transmitting the image of unified public opinion of this type of cognition? To realize this vision, traditional journalism must first depart radically from neoliberalism and individualism. Second, it must renew the ways in which it frames questions at the polling stage. At the very least, it is necessary to avoid individualizing responsibility for environmental degradation at the stage of reporting the results of public opinion polls. Public opinion polls aggregate people's opinions as individual opinions and are under the influence of political elites (Lewis, 2001), and may draw individuals away from shaping public opinion (Knobloch, 2011). However, depending on how the questions and the coverages are framed to help people understand that the current social, economic, and political systems that restrict, form, and frame people's behavior and cause environmental problems (Maniates, 2002, p. 65–66), they also have the potential to make people realize the need for social and collective action that will bring about social change, not just a little bit of individual action in the house. Meanwhile, renewing opinion polls may be a necessary condition for engaging with a public that is becoming increasingly submerged within a progressively liberal consumer society.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Funding

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENH, Grant-in-Aid for Early-Career Scientists, JP20K13708.

Acknowledgments

I extend my sincere gratitude to Prof. Tanifuji for his invaluable guidance and insights during my time at Waseda University's School of Political Science and Economics. I am also thankful to Prof. Segawa and Prof. Hino for their technical assistance and encouragement. My appreciation also goes to the reviewers for their constructive feedback and to Rob Fahey for his English-language support. Finally, I acknowledge the financial support from JSPS that enabled the completion of this study.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^The 1990 poll and articles were not included in the analysis data. In this poll, environmental questions were included only as part of a broader set of questions on societal problems, and the headline did not relate to environmental issues.

References

Ader, C. R. (1995). A longitudinal study of agenda setting for the issue of environmental pollution. Journal. Mass Commun. Q. 72, 300–311. doi: 10.1177/107769909507200204

Andersen, R. (2000). Reporting public opinion polls: the media and the 1997 Canadian election. Int. J. Public Opin. Res. 12, 285–298. doi: 10.1093/ijpor/12.3.000285

Asayama, S., and Ishii, A. (2014). Reconstruction of the boundary between climate science and politics: the IPCC in the Japanese mass media, 1988–2007. Public Underst. Sci. 23, 189–203. doi: 10.1177/0963662512450989

Baumann, S., Engman, A., and Johnston, J. (2015). Political consumption, conventional politics, and high cultural capital. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 39, 413–421. doi: 10.1111/ijcs.12223

Beckers, K. (2020). The voice of the people in the news: A content analysis of public opinion displays in routine and election news. Journal. Stud. 21, 2078–2095. doi: 10.1080/1461670X.2020.1809498

Beckers, K., Walgrave, S., and Van den Bulck, H. (2018). Opinion balance in vox pop television news. Journal. Stud. 19, 284–296. doi: 10.1080/1461670X.2016.1187576

Bellah, R. N., Madsen, R., Sullivan, W. M., Swidler, A., and Tipton, S. (1992). The Good Society. New York, NY: Vintage.

Bennett, W. L. (1996). An introduction to journalism norms and representations of politics. Polit. Commun. 13, 373–384. doi: 10.1080/10584609.1996.9963126

Bloom, P. (2017). The Ethics of Neoliberalism: The Business of Making Capitalism Moral. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315619019

Boykoff, M. T. (2007). Flogging a dead norm? Newspaper coverage of anthropogenic climate change in the United States and United Kingdom from 2003 to 2006. Area 39, 470–481. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-4762.2007.00769.x

Boykoff, M. T., and Boykoff, J. M. (2004). Balance as bias: global warming and the US prestige press. Glob. Environ. Change 14, 125–136. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2003.10.001

Brettschneider, F. (1997). The press and the polls in Germany, 1980–1994 poll coverage as an essential part of election campaign reporting. Int. J. Public Opin. Res. 9, 248–265. doi: 10.1093/ijpor/9.3.248

Broh, C. A. (1980). Horse-race journalism: reporting the polls in the 1976 presidential election. Public Opin. Q. 44, 514–529. doi: 10.1086/268620

Brookes, R., Lewis, J., and Wahl-Jorgensen, K. (2004). The media representation of public opinion: British television news coverage of the 2001 general election. Media Cult. Soc. 26, 63–80. doi: 10.1177/0163443704039493

Carmichael, J. T., and Brulle, R. J. (2017). Elite cues, media coverage, and public concern: an integrated path analysis of public opinion on climate change, 2001–2013. Environ. Polit. 26, 232–252. doi: 10.1080/09644016.2016.1263433

Carragee, K. M., and Roefs, W. (2004). The neglect of power in recent framing research. J. Commun. 54, 214–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2004.tb02625.x

Chilton, P. (1987). Metaphor, euphemism and the militarization of language. Curr. Res. Peace Violence 10, 7–19.

Dietz, T., Gardner, G. T., Gilligan, J., Stern, P. C., and Vandenbergh, M. P. (2009). Household actions can provide a behavioral wedge to rapidly reduce US carbon emissions. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 106, 18452–18456. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908738106

Dirikx, A., and Gelders, D. (2010). To frame is to explain: a deductive frame-analysis of Dutch and French climate change coverage during the annual UN Conferences of the Parties. Public Underst. Sci. 19, 732–742. doi: 10.1177/0963662509352044

Edy, J. A., and Meirick, P. C. (2019). A Nation Fragmented: The Public Agenda in the Information Age. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

Entman, R. M. (1993). Framing: toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. J. Commun. 43, 51–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x

Eriksen, E. O. (2005). An emerging European public sphere. Eur. J. Soc. Theory 8, 341–363. doi: 10.1177/1368431005054798

Gamson, W. A., Croteau, D., Hoynes, W., and Sasson, T. (1992). Media images and the social construction of reality. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 18, 373–393. doi: 10.1146/annurev.so.18.080192.002105

Gamson, W. A., and Modigliani, A. (1989). Media discourse and public opinion on nuclear power: a constructionist approach. Am. J. Sociol. 95, 1–37. doi: 10.1086/229213

Gitlin, T. (1979). Prime time ideology: the hegemonic process in television entertainment. Soc. Probl. 26, 251–266. doi: 10.2307/800451

Government of Canada (2018). Disposal of Waste, by Source. Available online at: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=3810003201 (accessed July 23, 2023).

Groeling, T. (2008). Who's the fairest of them all? An empirical test for partisan bias on ABC, CBS, NBC, and fox news. Pres. Stud. Q. 38, 631–657. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-5705.2008.02668.x

Guber, D. L. (2003). The Grassroots of a Green Revolution: Polling America on the Environment. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. doi: 10.7551/mitpress/3351.001.0001

Hardmeier, S. (1999). Political poll reporting in Swiss print media: analysis and suggestions for quality improvement. Int. J. Public Opin. Res. 11, 257–274. doi: 10.1093/ijpor/11.3.257

Hayes, A. F., and Krippendorff, K. (2007). Answering the call for a standard reliability measure for coding data. Commun. Methods Meas. 1, 77–89. doi: 10.1080/19312450709336664

Herbst, S. (1998). Reading Public Opinion: How Political Actors View the Democratic Process. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Holsanova, J., Rahm, H., and Holmqvist, K. (2006). Entry points and reading paths on newspaper spreads: comparing a semiotic analysis with eye-tracking measurements. Vis. Commun. 5, 65–93. doi: 10.1177/1470357206061005

Iyengar, S. (1990). Framing responsibility for political issues: the case of poverty. Polit. Behav. 12, 19–40. doi: 10.1007/BF00992330

Kent, J. (2009). Individualized responsibility and climate change: “if climate protection becomes everyone's responsibility, does it end up being no-one's?” Cosmop. Civil Soc. 1, 132–149. doi: 10.5130/ccs.v1i3.1081

Knobloch, K. R. (2011). Public sphere alienation: a model for analysis and critique. Javnost 18, 21–37. doi: 10.1080/13183222.2011.11009065

Krippendorff, K. (2005). “The social construction of public opinion,” in Kommunikation über Kommunikation, eds E. Wienand, J. Westerbarkey, and A. Scholl (Berlin: Springer), 129–149. doi: 10.1007/978-3-322-80821-9_10

Larsen, E. G., and Fazekas, Z. (2020). Transforming stability into change: how the media select and report opinion polls. Int. J. Press Polit. 25, 115–134. doi: 10.1177/1940161219864295

Lewis, J. (2001). Constructing Public Opinion: How Political Elites do What They Like and Why we Seem to go Along with it. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Lewis, J., Wahl-Jorgensen, K., and Inthorn, S. (2004). Images of citizenship on television news: constructing a passive public. Journal. Stud. 5, 153–164. doi: 10.1080/1461670042000211140

Liang, X., Tsai, J.-Y., Mattis, K., Konieczna, M., and Dunwoody, S. (2014). Exploring attribution of responsibility in a cross-national study of TV news coverage of the 2009 United Nations climate change conference in Copenhagen. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 58, 253–271. doi: 10.1080/08838151.2014.906436

Maniates, M. (2002). “Individualization: plant a tree, buy a bike, save the world?” in Confronting Consumption, eds T. Princen, M. Maniates, and K. Conca (Cambridge, MA: MIT press), 43–66.

McCargo, D. (1996). The political role of the Japanese media. Pac. Rev. 9, 251–264. doi: 10.1080/09512749608719181

McCright, A. M., and Dunlap, R. E. (2003). Defeating Kyoto: the conservative movement's impact on US climate change policy. Soc. Probl. 50, 348–373. doi: 10.1525/sp.2003.50.3.348

McCright, A. M., and Dunlap, R. E. (2011). The politicization of climate change and polarization in the American public's views of global warming, 2001–2010. Sociol. Q. 52, 155–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-8525.2011.01198.x

McGregor, S. C. (2019). Social media as public opinion: how journalists use social media to represent public opinion. Journalism 20, 1070–1086. doi: 10.1177/1464884919845458

McLeod, D. M., and Hertog, J. K. (1992). The manufacture of ‘public opinion' by reporters: informal cues for public perceptions of protest groups. Discourse Soc. 3, 259–275. doi: 10.1177/0957926592003003001

Murdock, G. (1973). “Political deviance: the press presentation of a militant mass demonstration,” in The Manufacture of News: Social Problems, Deviance and the Mass Media, Constable, eds S. Cohen, and J. Young (London: Sage), 156–175.

Nagai, K. (2017). Mapping Media Attention to Climate Change in Japanese Newspapers from 1988 to 2010. Asian J. Media Journal Stud. 1, 17–44.

Noelle-Neumann, E. (1974). The spiral of silence a theory of public opinion. J. Commun. 24, 43–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.1974.tb00367.x

Ohta, H. (2000). “Japanese environmental foreign policy,” in Japanese Foreign Policy Today: A Reader, 1st ed., eds T. Inoguchi and P. Jain (London: Palgrave), 96–121. doi: 10.1007/978-1-349-62529-1_6

Olausson, U. (2009). Global warming-global responsibility? Media frames of collective action and scientific certainty. Public Understand. Sci. 18, 421–436. doi: 10.1177/0963662507081242

Pajon, C. (2010). Japan's Ambivalent Diplomacy on Climate Change. The Institut français des relations internationales.

Patterson, T. E. (2005). Of polls, mountains: US journalists and their use of election surveys. Public Opin. Q. 69, 716–724. doi: 10.1093/poq/nfi065

Sampei, Y., and Aoyagi-Usui, M. (2009). Mass-media coverage, its influence on public awareness of climate-change issues, and implications for Japan's national campaign to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Glob. Environ. Change 19, 203–212. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2008.10.005

Sato, T. (2008). “[Establishment of Japanese-style “public opinion”: from information propaganda to public opinion polls] Nihongata yoron no seiritu: zyouhou senden kara yoron tyousa he (in Japanese),” in [Public Opinion Research and Polls] Yoron Kenkyu to Seron Tyousa, eds N. Okada, T. Sato, S. Nishihira, and M. Miyatake (Tokyo: Shin-yo-sha), 86–136.

Searles, K., Ginn, M. H., and Nickens, J. (2016). For whom the poll airs: comparing poll results to television poll coverage. Public Opin. Q. 80, 943–963. doi: 10.1093/poq/nfw031

Shove, E. (2003). Comfort, Cleanliness and Convenience: The Social Organization of Normality. Oxford: Berg.

Shove, E. (2010). Beyond the ABC: climate change policy and theories of social change. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 42, 1273–1285. doi: 10.1068/a42282

Smith, T. J., and Verrall, D. O. (1985). A critical analysis of Australian television coverage of election opinion polls. Public Opin. Q. 49, 58–79. doi: 10.1086/268901

Stearns, L. B., and Almeida, P. D. (2004). The formation of state actor-social movement coalitions and favorable policy outcomes. Soc. Probl. 51, 478–504. doi: 10.1525/sp.2004.51.4.478

Sustainable Consumption Round Table (2006). I will if you will: Towards Sustainable Consumption. Available online at: https://www.sd-commission.org.uk/data/files/publications/I_Will_If_You_Will.pdf (accessed August 30, 2023).

Trumbo, C. (1996). Constructing climate change: claims and frames in US news coverage of an environmental issue. Public Underst. Sci. 5, 269–283. doi: 10.1088/0963-6625/5/3/006

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (2017). National Overview: Facts and Figures on Materials, Wastes and Recycling. Available online at: https://www.epa.gov/facts-and-figures-about-materials-waste-and-recycling/national-overview-facts-and-figures-materials (accessed August 30, 2023).

United Nations Environment Programme (2008). CCCC: Kick the Habit. Available online at: https://www.uncclearn.org/wp-content/uploads/library/unep11.pdf (accessed August 30, 2023).

Willis, M. M., and Schor, J. B. (2012). Does changing a light bulb lead to changing the world? Political action and the conscious consumer. Ann. Am. Acad. Polit. Soc. Sci. 644, 160–190. doi: 10.1177/0002716212454831

Wynes, S., and Nicholas, K. A. (2017). The climate mitigation gap: education and government recommendations miss the most effective individual actions. Environ. Res. Lett. 12, 074024. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/aa7541

Keywords: public opinion, polls, poll coverage, newspaper coverage, environmental issues, content analysis

Citation: Nagai K (2023) The representation of public opinion in reporting poll results on environment issues. Front. Commun. 8:1225306. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2023.1225306

Received: 22 May 2023; Accepted: 18 August 2023;

Published: 02 October 2023.

Edited by:

Anders Hansen, University of Leicester, United KingdomReviewed by:

Steph Hill, University of Leicester, United KingdomJustin Reedy, University of Oklahoma, United States

Copyright © 2023 Nagai. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kentaro Nagai, ay5uYWdhaTRAa3VyZW5haS53YXNlZGEuanA=

Kentaro Nagai

Kentaro Nagai