- 1Environmental and Social Epidemiology Unit, Department of Environment and Health, Istituto Superiore di Sanità, Rome, Italy

- 2WHO Collaborating Centre for Environmental Health in Contaminated Sites, Rome, Italy

This work aims to discuss the implementation of a communication plan as a key element of the epidemiological study to foster social capacity in the scarcely involved community of the industrial contaminated site of Porto Torres (Sardinia region, Italy). We established an inter-institutional working group committed to developing communication activities and materials ensuring multidisciplinary skills from social and communication sciences to collaborate with the environmental and health experts involved in the epidemiological study. The adopted methodological approach and communication strategy resulted in effective and successful engagement of local institutional and social actors in the design and implementation of targeted communication activities. Designing and implementing environmental public health communication processes with poorly involved communities residing close to industrially contaminated sites is critically important. In these areas, environmental noxious exposures associated with high health risks are frequently combined with low socioeconomic conditions. This calls upon mechanisms of environmental injustice, distributive and procedural, and emphasizes the need to prioritize interventions based on integrative strategies securing local communities' engagement through informed participation. Based on the lessons learned in this community-focused experience in Italy, we have identified key actions for suitable environmental public health communication to foster social capacity and promote procedural environmental justice in communities living in other industrial contaminated sites.

1 Introduction

There is increasing awareness about the role of communication as a process for engaging diverse stakeholders to better address environment and health issues (World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe, 2013a, 2021a). Moreover, it is also well-recognized that “communication approaches should be based on a clear methodology, be participatory and integrate sociological methods into traditional public health-oriented ones” (World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe, 2013a). Participatory communication relies on a dialogical and horizontal approach where a collective problem is addressed involving all relevant stakeholders (Huesca, 2008; Tufte and Mefalopulos, 2009). In this context, a two-way communication process is aimed to engage stakeholders to be aware of the problem and to define the needed change to address rather than to persuade audiences to adopt a predefined change (Tufte and Mefalopulos, 2009). These reference frameworks assume a critical importance in planning and implementing environmental and public health communication processes with communities residing close to industrially contaminated sites (World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe, 2013b, 2021b). Building on a previous operational definition proposed by WHO (World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe, 2013b), these sites have been defined as “areas hosting or having hosted industrial human activities which have produced or might produce, directly or indirectly (waste disposals), chemical contamination of soil, surface or ground-water, air, food-chain, resulting or being able to result in human health impacts” (Iavarone and Pasetto, 2018).

In these areas, environmental noxious exposures associated with high health risks are frequently combined with low socioeconomic conditions of the affected communities (Pasetto and Iavarone, 2020), including misrecognition of their right to be informed and participate through inclusive communication (Pasetto et al., 2019; Marsili et al., 2021). The latter can imply the marginalization of people in participating in the decision-making process concerning the settlement of industrial plants and/or their management in association with negative and positive impacts over time on the local population (Pasetto et al., 2019). In this regard, besides adverse impacts, local communities can also benefit from the output of industrial activities, including the opportunities that arise from employment in industrial plants or in the related economic activities and services. Moreover, benefits for the communities and their living environment can also derive from remediation and/or redevelopment of contaminated sites, especially when the site is made available for public re-use (World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe, 2021b).

This calls upon mechanisms driving environmental justice, both in its distributive and procedural domains (Schlosberg, 2007; Holifield et al., 2018). The knowledge on these mechanisms drives to the need of priorizing interventions in industrial contaminated sites adopting integrated strategies to address environmental, health, social and economic aspects (Lee, 2002). Moreover, knowing that communication is a complex and unequally distributed social capability (Enghel, 2014), major efforts should be directed to ensure the involvement of local communities through informed participatory communication (Pasetto and Marsili, 2023).

Considering the local community framework in such contaminated areas, is therefore crucial also from an environmental public health perspective, since the health effects of environmental pressures usually concerns people who: (i) share a geographic location; (ii) have common interests, problems, and identities; (iii) have social interactions that bind persons to each other through reciprocal relationships; (iv) share needs and problems that can be addressed through collective action (Laverack, 2016). These elements do not imply that local communities are homogeneous and straightforward entities. The degree of cohesion depends on the community's ability to respond to its members' needs and structural characteristics (Mannarini, 2016).

One critical point in promoting environmental justice and public health in communities living in industrial polluted sites is represented by the capacity of institutional stakeholders (public health authorities and researchers) to correctly communicate the evidence of the health impact of contamination directly to the affected communities, beginning from their key representatives, and effectively involve local stakeholders (Ramirez-Andreotta et al., 2014).

Each industrially contaminated site has its own characteristics. From the public health perspective, various can be the sources of contamination, the key contaminants, the pathways, and the circumstances of exposure of the affected population (Iavarone and Pasetto, 2018). In those contexts, promoting environmental public health therefore requires considering the community level, especially in the so-called monotowns (Shastitko and Fakhitova, 2015), where the presence of large industrial plants or industrial complexes determines a mono-functional evolution (i.e., a very strictly related socioeconomic progression of the communities and the industries) precluding them from any other possible development.

In these complex scenarios, the temporal dimension of the contamination process and the health-related effects, along with changes in the socio-demographic, economic and cultural characteristics of local communities, represent another relevant key issue. Epidemiological studies and surveillance of population living in contaminated areas help to characterize the health risk from contamination. However, in most cases, single studies cannot usually address the overall health impact, particularly of long-term contamination, started decades before the beginning of the assessment. Establishing a cause-effect relationship between a given contamination and the associated health risk is a challenging task. Nevertheless, whatever the applied epidemiological study design is, results should be considered under the perspective of the precautionary principle, which implies considering also partial and uncertain evidence on observed past and present risks as signals (i.e., facts) when communicating and providing recommendations for interventions (Comba and Pasetto, 2022).

The adoption of a communication approach integrated in an epidemiological study in poorly involved communities living in industrially contaminated sites requires taking into account two major issues for developing strategies that consider the specificity of the socio-cultural and institutional local context: (1) local communities have a long-lasting lack of answers on the possible connections between contamination and their health; (2) whatever the adopted epidemiologic study design is, results concerning the link between environmental contamination and health are usually weak and associated uncertainties have to be communicated (Renn, 2010; World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe, 2013a).

An international survey on the adoption of communication plans on risk associated with contaminated sites (Martin-Olmedo et al., 2019) showed that almost half of respondents (experts from 27 countries reporting on 81 key relevant sites) were either not aware or did not know whether a risk communication campaign was ever carried out in the contaminated site of interest, or whether stakeholders were involved in the development of the communications strategy. Moreover, very few campaigns focused specifically on health risk data, and about half of respondents declared an underreporting of uncertainty in health risk estimates, independently of the stakeholder categories involved in the risk communication strategies.

This work aims to present and discuss the adoption of a structured approach for the implementation of a communication plan as a vital element of an epidemiological study to foster social capacity in the scarcely involved community of the industrial contaminated site of Porto Torres (Sardinia region, Italy). Our goal is also to point out and share the lessons learned for developing and undertaking participative communication initiatives with other poorly involved communities living in contaminated sites.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Setting

Porto Torres is a municipality of about 22,000 residents located in the Northwest of the Sardinia Region (Italy). Porto Torres's town is immediately close to a large industrial complex, including several petrochemical plants, a thermoelectric power plant, and an industrial and civil harbor. The petrochemical complex started its operation in the 60s of the last century, reaching a peak of around 8,000 workers in the 70s. The population of Porto Torres grew by about 45% in the period 1961–1971. Industrialization caused a profound transformation at a local level. In a short time, Porto Torres had become one of the most important centers of the European petrochemical industry, and this had led to the birth of numerous associated companies operating both in production and in services. After the first period of industrial and socioeconomic development, when significant industrial efforts were directed at improving production efficiency, as for other similar sites in southern Italy and the Great Islands, significant environmental contamination was progressively documented (Pasetto and Iavarone, 2020).

Porto Torres was declared a Site of national priority for remediation in 2002. Most of the petrochemical plants closed around 2010 (with a massive loss of the workforce). The surviving current activities involve a few hundred of workers. As estimated by the Census 2011 data, 80% of the local population resides in highly socioeconomically deprived census tracts (Pasetto et al., 2022).

Porto Torres, for its history, can be considered a monotown in which the development and destiny of the industrial complex and the nearby community are strictly interconnected.

The Porto Torres contaminated site is included among the currently 46 Italian priority sites for remediation analyzed by the Italian national surveillance system “SENTIERI” with provides periodical updates of the health profile of the resident population (Zona et al., 2023). This surveillance system is based on informative flows of health data managed at central/national level and does not rely upon local environmental/health information, nor includes direct interaction with local stakeholders to build up shared study protocols.

It is relevant to say that, despite the environmental health concerns of the local population, no ad hoc study has been previously carried out in Porto Torres to address the possible association between environmental contamination and health for the local affected community. In the last years, the Italian National Institute of Health (ISS) in collaboration with regional and local authorities and technical bodies in the environment and health fields designed new epidemiological activities. In order to answer to the legitimate needs of the local institutional and social actors, a new study was implemented, namely “Health profile of a community affected by industrial contamination, the case of Porto Torres (Sardinia, Italy): environment-health assessment, epidemiology, and communication” (Pasetto et al., 2022). The study aimed at achieving the following goals: (a) collection and systematization of environmental contamination data; (b) identification of priority pollutants from the point of view of their danger to health and potential exposure of the population; (c) description of the health profiles of the local population considering multiple health outcomes (mortality, morbidity—using hospital discharge records-, cancer incidence) from local information systems; (d) identification of the most important results on the basis of an integrated evaluation of environmental, toxicological and epidemiological data; (e) definition and implementation of a contextualized participative communication plan.

The present paper aims to report the experiences matured and the lesson learned in implementing a structured communication plan, shared with local stakeholders, and aimed at improving the poor social capacity of the Porto Torres community. The adopted methodology is presented below.

2.2 Strategy and aims of the communication plan

The communication strategy designed and implemented in the epidemiological study of Porto Torres relies on the communication guidelines proposed within the Italian epidemiological surveillance system of the priority contaminated sites for remediation SENTIERI (Marsili et al., 2017, 2021), and adapted to the specific characteristics of the local community context.

This approach was also acknowledged as best practice by the COST Action IS1408 on Industrially Contaminated Sites and Health Network (ICSHNet), an international coordination action aimed to establish and consolidate a European network of experts and institutions, and develop a common framework for research and response on environmental health issues related to industrially contaminated sites. ICSHNet involved about 50 environmental health institutions of 33 participating countries in the WHO European Region (https://www.cost.eu/actions/IS1408/; COST Action IS1408, 2019).

We implemented the communication plan for Porto Torres community in collaboration with the local and regional health communication offices of the Sardinia Region. Four hierarchical methodological steps compose the plan: (1) definition of the communication aims; (2) identification and engagement of local institutional and social actors in the communication activities; (3) selection of communication channels to disseminate tailored communication products to the diverse local stakeholders; (4) assessment of the impact of communication activities (Marsili et al., 2017, 2021).

The four steps have been adapted to the study of Porto Torres and implemented as follows:

1) Definition of the communication aims.

The main goal was to transfer and share with the Porto Torres community the new scientific knowledge gained from the epidemiological study that investigated, for the first time, the health profile of the population resident only in the municipality of Porto Torres. Closely related, the second goal was to establish an intersectoral network of institutional actors involved both in the epidemiological study and in the communication activities.

2) Identification and engagement of local institutional and social actors in the communication activities.

TOPIC. Knowledge of the local socio-institutional context is a key element for the identification and engagement of the local institutional and social actors of a municipality. In Porto Torres, we identified the governmental Authorities and health and environmental Authorities as the main institutional interlocutors and the local educational system and social actors, such as local environmental associations and media, as relevant target audiences.

ACTION. We implemented dedicated engagement initiatives to interact with each of the above-mentioned local actors using tailored languages for delivering key messages on the environmental health issues resulting from the study.

2.1) Engaging local governmental authorities.

TOPIC. Building relationships with local governmental authorities of a poorly involved contaminated community represents a critical aspect of the communication process. This is due to their relevant role in managing the scientific evidence emerging from the available studies in the decision-making process. The engagement of local governmental Authorities in the communication process, therefore, should foresee their participation in communicating with health and environmental local Authorities and in discussing the results of the epidemiological study with the community.

ACTION. We engaged and strengthened relationships with the mayor and several members of the Municipal Council since the beginning of the study period through a two-way dialogue concerning the purpose and contents of the study as well as of the socioeconomic context of the Porto Torres municipality.

The engagement methodology also relied on baseline semi-structured surveys and interviews with members and councilors of the Porto Torres local Government, envisaging their informed consent. The surveys and the interviews were designed by two researchers and verified by the communication expert of the local health Office, and conducted the first in October 2021, mid-way in the study, and the second 3 months after the communication of the study results in September 2022. The aims were to assess the awareness of the local governmental Authorities about the impact of the polluting industrial complex on the community, their information needs and expectations from the epidemiological study, and their consideration regarding the communication to the community of the epidemiological study findings.

2.2) Establishing an inter-institutional communication working group collaborating with the experts involved in the epidemiological study focusing on environmental and health issues.

TOPIC. The engagement of the communication offices of the health Authorities at local and regional levels is an indispensable action to share strategies and implement the communication plan. The communication-working group has to be committed to undertake tailored communication activities and to collaborate with the experts of environmental and epidemiological working groups who provide the scientific contents. A multidisciplinary study team has the potential to address environmental, health, social and communication components of the study (Hoover et al., 2015; Comba and Marsili, 2019).

ACTION. In Porto Torres, since the design of the epidemiological study, we established an inter-institutional (national-regional-local) working group ensuring multidisciplinary skills from social and communication sciences for a fruitful collaboration with the environmental and health experts involved in the epidemiological study to implement communication activities (Marsili et al., 2021).

2.3) Involving the local educational system.

TOPIC. Fostering knowledge and awareness of young people about the environmental pollution and health-related effects in the areas where they live, especially in communities living in contaminated sites characterized by modest available information, requires good practices to meet the interactive (i.e., two-way communication) aspired level of participation (Adamonyte and Loots, 2017). This is also necessary to increase their critical thinking and motivations to participate in the community life (Mogensen, 1997). An effective action consists of establishing local networks of schools in communication activities relying on the peer education methodology (Topping et al., 2017), with the goal to train students to be educators or tutors for their peer group on the environmental and health risks affecting their community. The school network established in Casale Monferrato, an asbestos contaminated community in Italy, is a successful experience of this action (Marsili et al., 2019a,b).

ACTION. We envisaged the interactions with teachers from the schools of Porto Torres through the municipal Administration for involving them in framing participative training initiatives for students. Unfortunately, we were unable to develop these collaborations due to the outbreaks of the COVID-19 pandemic that prevented us to perform participative meetings and activities in presence with teachers and students in their schools. This type of communication activities has been done in presence to effectively engaging students and teachers.

2.4) Engaging local social actors and citizens.

TOPIC. The engagement of local social actors, such as environmental associations and media, is a fundamental action in poorly investigated contaminated sites to adopt a participative approach to the local communication process aimed at promoting a transparent information flow and interactions between institutional and social actors. This is particularly important for communicating with the media, as mediators of information to the community (Kasperson et al., 1988), and with the community at large, which requires tailored messages to be delivered through both institutional communication channels and public events. Improvement of environmental health literacy of the local social actors promotes their motivations and informed participation in decision-making and accountability of the local institutional actors (Ramirez-Andreotta et al., 2016; Ramírez et al., 2019; Marsili et al., 2021).

ACTION. In Porto Torres, we established and progressively improved interactions with a local environmental association; we communicate with media and citizens on the purposes and findings of the epidemiological study through both institutional communication channels and public events.

3) Selection of communication channels to disseminate tailored communications products to the diverse local stakeholders.

TOPIC. For a community which has never been involved in a participative communication process, as likely those living close to poorly investigated contaminated sites, it is necessary to make evidence-based information accessible and comprehensible for all citizens using correct and simplified language through institutional communication channels. Moreover, it is crucial to provide tailored materials and messages to interlocutors having different environmental health literacy levels (Davis et al., 2018).

ACTION. At the beginning of the study, we identified the institutional websites of the Sardinian regional and local health Authorities as the official communication channels to disseminate tailored materials to diverse target categories related to the epidemiological study.

4) Assessment of the impact of communication activities.

TOPIC. The impact assessment of communication activities in contaminated sites during the different phases of the studies is essential to understand the increased awareness and preparedness of the community to manage environmental and health risks information. The assessment can rely on qualitative and quantitative indicators [Enghel, 2017; Federation for the Humanities and Social Sciences (FUSS), 2017; Marsili et al., 2017]. Assessing the impact of communication processes on previously uninvolved communities residing close to contaminated sites is particularly challenging due to their likely limited preparedness and modest experience to participate in communication initiatives.

ACTION. We considered the adoption of the following indicators in the Porto Torres context: (i) the level of engagement of local and regional health and environmental Authorities in communication; (ii) the awareness of the municipal Authorities on the community point of view on the socio-economic and environmental health impact of the industrial complex; (iii) the number, contents, and tone of voice of the articles published on local and regional Media before and after the communication of the study results.

The methodological approach to environmental and public health communication described in this section relies on strengthening the capacity of local institutional actors to actively participate in the communication process with the community as well as on promoting preparedness and social capacity of the whole community (Pasetto et al., 2022).

3 Results

The adoption and implementation of the communication plan in Porto Torres relying on the methodological approach presented in this paper resulted to be quite effective for engaging key stakeholders, as explained in the following.

The establishment of the inter-institutional multidisciplinary working group ensured collaborations between experts from communication and social sciences and environmental and health experts from the national-regional-local Authorities involved in the epidemiological study. This allowed the shared implementation of the communication initiatives concerning the study findings and their implications on environmental and public health in Porto Torres.

The involvement of local governmental Authorities, planned since the beginning of the study, allowed us to build and strengthen trusted relationships during the study period, which fostered their engagement in several activities such as the interviews, the final communication event for presenting the results of the study to the community, and the subsequent interactions for impact assessment.

The latter aspects were confirmed by results of two rounds of baseline semi-structured surveys and interviews conducted by a trained interviewer respectively mid-way in the study timeline and 3 months after the final communication of the study findings. This assessment involved 9 members of the Porto Torres local Government (the Mayor and Municipal Council) for a total of 18 interviews. We discharged two further interviews because two different people responded only to one of the two rounds. The analysis of the information collected from the respondents allowed us to assess their engagement and awareness on the community living conditions, relationships and needs to be involved in a participatory approach. In particular, we have analyzed their awareness of the community point of view concerning the impact of the polluting industrial complex on the environment, health, economic conditions, and citizen's relationships. By comparing their answers in the first and the second interviews, it emerges that most of the respondents strengthened their opinion on the negative impact of the industrial complex on the community health and the environment, while confirming its positive impact on the economic conditions and the citizens' relationships in the first period after the plant opening. Moreover, the respondents recognized a growing conflict between population subgroups belonging to different occupational sectors as well as between old-young people due to a generational discontinuity about the perspective of developing a monofunctional community. They also pointed out the conflict between the workers of the industrial complex and other citizens concerning the environmental and health impacts. They were also aware of the low trust of citizens in local institutions, mostly due to the historical poor exchanges and the failure of previous attempts to disseminate information.

The analysis of the interviews also pointed out the information needs and expectations from the epidemiological study of the municipal Authorities. During the first round of interviews, all the respondents expressed their interest in being informed on the cancer incidence affecting the community as well as on the evidence of causal relationships between the industrial pollution and the health-related effects. In the second round of interviews, all respondents expressed satisfaction with the results of the study in terms of providing evidence-based information not relying only on self-perceptions. They also agreed that the results allow them to take informed decisions in planning interventions. They also identified three key areas for recommended actions based on the study results: continuing the remediation activities; implementing environmental monitoring also considering possible new activities developed within the industrial complex; implementing cancer screening campaign and informing general practitioners on the epidemiological profile of the population to make them aware of specific risks.

A further important aspect concerned the increasing awareness of the respondents from the local government of the need to communicate with the community the results of the epidemiological study as well as contextualized environmental health issues. Furthermore, in the second interview, the respondents stressed the willingness to promote environmental health literacy initiatives for the young generations in Porto Torres.

The effective engagement of the local governmental Authorities during the whole study period promoted their motivated and proactive participation in co-organizing a local public event to communicate the epidemiological study results. Moreover, by participating in person to the final communication event, they expressed their accountability to the community coherently with their role of decision-makers, corroborating the importance of adopting a participative approach to communication.

The communication of the study findings to the Porto Torres community, including local environmental associations and citizens, was performed during the final public event, attended both in-person and remotely (i.e., online). We, researchers from the ISS, co-organized the event with the local governmental Authorities and with the inter-institutional working group. The active participation of representatives of the local institutions, social actors, and citizens, each one with its own role and responsibility, corroborates the effectiveness of the communication in addressing delicate and sensitive topics such as the implementation of recommendations resulting from the epidemiological study and the consequent actions for prevention and environmental remediation.

The information flow and the contents of the communication material deserved special attention.

We published a section dedicated to the study namely “Health and Environment in Porto Torres” (Salute e Ambiente a Porto Torres in the institutional websites https://www.sardegnasalute.it/index.php?xsl=316&s=9&v=9&c=94516&na=1&n=10), where all the outreach material was progressively made available and freely accessible. Outreach materials consisted of:

• Tailored documents in lay language to share with non-expert interlocutors the study findings through texts (poster information and web texts) and informative graphic representations such as the digital conceptual map of the study highlighting the links between the environmental and health issues characterizing the study and the glossary of the most relevant scientific terms used by the study;

• A technical report for local and regional health and environmental technicians containing the adopted methodologies of the environmental, health, and communication components of the study as well as the study results (Pasetto et al., 2022);

• Abooklet in lay language for sharing with the Porto Torres community the most relevant study findings using a correct and simplified language (Istituto Superiore di Sanità, 2022). This booklet is publicly available also at the ISS official website at: https://www.iss.it/documents/20126/0/SaluteAmbiente_PORTO_TORRES.pdf/63d57379-d94c-76a1-f633-168d31554fac?t=1655293653209.

Following the adopted methodology, we assessed the impact of communication activities in Porto Torres through qualitative and quantitative indicators as described in the following.

i) Level of engagement of local and regional health and environmental Authorities in communication (poor, medium, high). Their engagement level resulted to be high because of the effective collaborations with the inter-institutional communication-working group. They participated and shared responsibilities in selecting information and the most relevant results of the study to be shared with the whole community through outreach and dissemination initiatives. Their active participation in the final public event to communicate the study findings further corroborated their full engagement.

ii) Awareness of the municipal Authorities on the community point of view about the impacts of the industrial complex and the communication needs. The analysis of the information collected during the two-rounds interviews demonstrated a progressive improvement of their awareness of the community concerns on the local environment and health problems, of the concerns and conflicts expressed by the diverse occupational sectors and old-young generations of the community. The local government representatives also expressed the need to foster environmental health communication initiatives relying on a participative approach.

iii) Number, contents, and tone of voice of the articles published on local and regional Media before and after the communication of the study results. Information concerning the event was published on the Porto Torres institutional website (https://www.comune.porto-torres.ss.it/it/novita/news/Pubblicati-i-risultati-dello-studio-epidemiologico-del-profilo-di-salute-della-popolazione-residente-nel-Comune-di-Porto-Torres/) 1 month before the date as well as subsequently on the regional and local institutional social media (Facebook). We monitored the publication of articles in journals, websites and social media addressing the study findings in the months before and after the public communication event. We counted a total of 24 articles, 13 of which before (four in regional and local journals, five in local websites, and four in social media) and 11 after the communication of the study results (five in regional and local journals, four in local websites, and two in social media). Moreover, we assessed the contents of the articles in terms of the correctness and faithfulness of the study aims and results. We found non-alarming information in most of the articles. They effectively focused on the key messages emerging from the study. They reported the actual aims of the study, and the articles published after the communication of the study results reported the sentences taken from the booklet presented during the public event and published on the regional and local institutional websites.

4 Discussion

The strategic decision to establish the inter-institutional and multidisciplinary working group, to share and plan the communication initiatives related to the epidemiological study and assess the implications for environmental and public health in Porto Torres, turned out to be particularly relevant. The engagement of experts from the health communication offices of the Sardinia Region in the communication-working group allowed us to better implementing the communication initiatives taking into account local information and knowledge of the Porto Torres socio-institutional context. This made it possible to identify the local institutional and social actors to be involved, the socio-cultural attitude and behaviors of the community to be included in public events; the level of the citizens' trust in the local institutions, the socioeconomic housing distribution of Porto Torres.

The design and implementation of a contextualized communication plan is a peculiar characteristic of an epidemiological study focused on a specific community (Pasetto et al., 2022). Indeed, Porto Torres municipality is the urban nucleus adjacent to the industrial complex (including the petrochemical, a thermoelectric power plant and the port area) within a larger contaminated site also including, for administrative reasons, the town of Sassari (about 130,000 inhabitants with the urban area located about 20 km away from the industrial complex). Our community-based epidemiological study included, for the first time, only the population of Porto Torres (about 22.000 inhabitants) identified as the main target community affected by industrial contamination and subject to epidemiological assessment. This approach has strongly motivated the involved local environmental and health experts to directly participating in the public communication initiatives, and also answering to the information needs of the community through a participative approach.

Moreover, the multidisciplinary and inter-institutional working group ensured the creation of a collaborative framework and fostered the establishment of trust relationships among the local environmental and health institutional actors, which is vital to implement tailored communication strategies and tools (Leach et al., 2022). This also facilitated the engagement of, and the interactions with the local governmental Authorities. We planned the engagement of local governmental Authorities since the beginning of the study. We experienced a change of the local Government because of political elections in Porto Torres. For this reason, we interacted with two different mayors and municipal Councils. The adoption of a transparent information flow concerning the purposes and findings of the study allowed us to interact with both Councils recognizing their role of decision-makers for health prevention initiatives. We built and strengthened trust relationships with them during the study period including the first round of interviews, the co-organization of the final communication event, the communication with the community, and the subsequent interactions for the second round of interviews for impact assessment. The involvement of local stakeholders, such as governmental Authorities and environmental and health institutional actors in the implementation of the communication plan, resulted to be essential to fostering community social capacity in a contextualized process. Thanks to this approach, new shared evidence-based knowledge, placed-based experiences, cultural and social relationships, and motivations (Tufte and Mefalopulos, 2009; Ramirez-Andreotta et al., 2016) converged in the informed participation in decision-making.

The establishment and the progressive improvement of interactions with representatives of a local environmental association, who have been asking for a dedicated epidemiological study on the Porto Torres residents for many years, allowed a transparent information flow about the purposes and the outcomes of the epidemiological study. Access to the study findings was guaranteed through both direct interactions with the involved researchers and the materials made available through the institutional websites. Tailored messages conveyed through simplified languages to explain the new and complex evidence-based information, including limitations and scientific uncertainties of the epidemiological study, allowed us to interact with the local association on the study results and related recommendations. Indeed, outside the scientific community, the communication of the uncertainties affecting the epidemiological results is usually more difficult for those elements of risk that inexperienced stakeholders poorly understand (Kasperson et al., 2022). These continued interactions among relevant stakeholders also facilitated the promotion of their proactive role for developing, likely for the first time, a shared reasoning about the issue of environmental justice (Raphael, 2019).

Furthermore, local media used the most important messages from the epidemiological study, freely accessible through the local institutional websites, for their own communications aimed at describing the resulting environmental health profile of Porto Torres residents. These contributions actually resulted in effective dissemination to the community, avoiding alarming messages. They also highlighted the transparent approach adopted in communicating the aims and results of the epidemiological study to the whole community.

The creation of this collaborative framework for sharing communication strategies and initiatives fostered the establishment of trust relationships among the local governmental Authorities, environmental and health institutional actors as well as the effective engagement of social actors.

Undoubtedly the interest and active participation of experts from the National Institute of Health (ISS) in the design and implementation of the epidemiological study and the related communication plan has contributed to strengthening the trust of local community in public institutions, favoring the establishment of constructive interactions.

This allowed us to set up those participatory processes necessary for the communication (Tufte and Mefalopulos, 2009) and the promotion of an effective mitigation of environment and health risks. Contextualized participative processes contribute to enabling management of the environmental and health risks as well as remediation of the local contaminated site toward the selection of the future site functions/uses (World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe, 2021b), including changing the monofunctional feature of a town and the related socio-economic development of the community. In such a context, procedural environmental justice is promoted where the community and all sub-groups are involved in the early stages of the planning process since they can be engaged in authentic discussions, rather than just being passively informed about decisions already taken. Procedural environmental justice embeds the promotion of an inclusive participation and a fair distribution of power in environmental decision-making (Bell and Carrick, 2018). Conversely, misrecognition of these communities and their marginalization in decision-making processes regarding the use of their lands and/or redevelopment of the contaminated site represent a frequently documented mechanism behind the generation and maintenance of environmental injustices (Pasetto et al., 2019). Indeed, the misrecognition and marginalization of the affected communities can also occur in interventions improving their living conditions such as cleaning-up interventions reducing degradation of their territories and in interventions to reduce exposure to pollutants and the related impact on their health (Pasetto and Iavarone, 2020). Mechanisms of exclusion and marginalization also drive “environmental assimilation” (Tsuji, 2021). The concept of environmental assimilation was recently introduced to define the phenomenon of a progressive exclusion of cultural activities (and loss of identities) of indigenous communities by introducing changes in the living environment to an extent where it can no longer support them. The same mechanism may progressively erode the cultural resources of local communities in monotowns, stimulating not only environmental injustice but also affecting one of the pillars of Sustainability (culture21: https://www.agenda21culture.net/home; Sabatini, 2019). Communities living in monotowns often have their own identities strictly connected with the contamination and require interventions apt to open a view to a future without contamination (Pasetto and Innocenti Malini, 2022). Difficulties in putting in practice participatory processes in environmental decision-making widely persist because of power disparities and mistrust between those with access to information and those without (Enghel, 2014; Carrick et al., 2022). This raises the urgency to address and implement the active engagement of affected communities' institutional and social actors starting from a full transparency to mitigate the effects of unequal power relations (Carrick et al., 2022). Procedural environmental justice is understood as institutional processes that determine access to information, participation, decision-making and justice representing a precondition to effectively address distributive injustice (Walker, 2012).

The implementation of contextualized communication plans as described in this paper for the community of Porto Torres, contributes to the adoption of both formal procedures and substantial recognition of the role of the local institutional and social actors and their rights to be involved as stakeholders in the negotiation of the interests at stake. Participated communication plans strengthen the community's social capacity enabling the awareness of the local institutional and social actors in sharing and using the new knowledge derived from the studies. This also contribute to fostering social networking, accountability, and trust relationships between citizens and institutions (Pasetto and Marsili, 2023). Indeed, these networks are a structural component of the linking social capital contributing to redistributing power among stakeholders (Solar and Irwin, 2010). This approach contributes to the local integration of environmental justice and sustainability, as advocated by scholars for promoting more just and equitable outcomes in decision-making processes and sustainability planning (Clark and Miles, 2021).

Environmental, social and health problems related to long-lasting contamination often affecting monotowns have to be addressed through multisectoral sustainable redeveloping actions, starting from cleaning up environmental pollution. Depending on the new function of the remediated site, the urban redevelopment projects can create new green spaces, sustainable jobs and improve the health, wellbeing and quality of life in the surrounding, often marginalized and vulnerable, communities (World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe, 2021a). The issue of human health in industrially contaminated areas is therefore properly addressed within a strong sustainability perspective capable of considering the evidence on health effects and impacts together with the broader context of environmental and ecosystem health as well as the social and occupational environment (Martuzzi and Matic, 2016).

In this perspective, new scientific evidence on effective remediation measures and redevelopment actions should be used to support local practitioners, as well as the engagement of stakeholders has to progress from the initial information and consult stages to an active collaborative work (Cundy et al., 2013). A transparent communication process showing the benefits of remediation and/or redevelopment for the community and enabling public participation to influence decision-making is a key component of engagement processes. To this goal, the technical and methodological competencies of local public authorities to manage public participation processes have to be improved (World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe, 2021b).

5 Conclusions

In this paper, we have discussed the implementation of a structured communication plan associated with the epidemiological study of a poorly involved community living in the contaminated site of Porto Torres. The adopted methodological approach and communication strategy resulted in effective and successful engagement of local institutional and social actors in the design and execution of targeted communication activities. The impact of communication and the level of engagement of local institutional and social actors (namely, the governmental authorities, health and environmental authorities, environmental associations, and media) have been assessed, corroborating the effectiveness of the adopted strategy and methodology. The experience gained in the communication of the Porto Torres epidemiological study with the different local stakeholders highlights the importance of including the communication plan as a key element of the study.

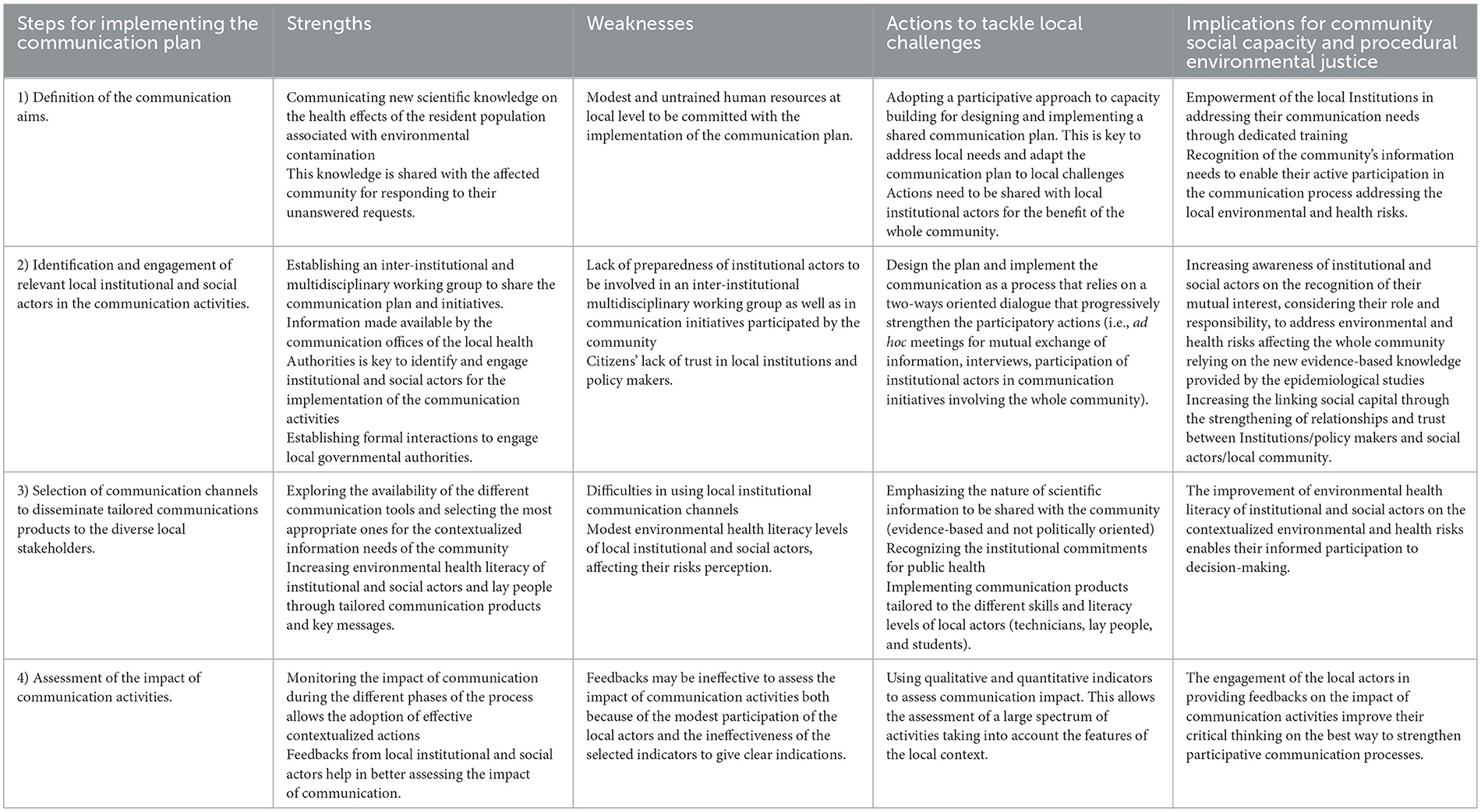

Based on the lessons learned in this community-focused experience in Italy, we were able to identify some key features for a suitable environmental public health communication that should be addressed to foster social capacity in poorly involved communities living in industrial contaminated sites. To share our experience and lessons learned with other studies in contaminated sites, we suggest as a recommendation or a good practice the hierarchical four-step communication procedure proposed in this study. Table 1 summarizes for each step the outcomes of the communication of the epidemiological study in Porto Torres in terms of strengths, weaknesses, actions to tackle local challenges, and implications for the community social capacity and procedural environmental justice at local level. Strengths and the weaknesses identified for each step undertaken to implement the communication plan, though refer to the Porto Torres study, are representative for other areas with poorly involved communities. The actions to tackle local challenges can be considered as either strategic actions to secure strengths or mitigation actions to overcome weaknesses. These strategic actions are also proposed to ensure the improvement of community social capacity and the promotion of procedural environmental justice.

Table 1. Key actions for a suitable environmental public health communication with poorly involved communities living in industrial contaminated sites. Hierarchical four-step communication procedure is analyzed in terms of strengths, weaknesses, actions to tackle local challenges and implications for the community social capacity and environmental procedural justice.

The adopted approach for environmental public health communication in Porto Torres allowed us to establish a participatory process, nested in an epidemiological study, to address the issues of procedural environmental justice. This approach is suitable to be applied and consolidated by researchers and practitioners in other similar industrial contaminated areas to engage stakeholders and foster social capacity in communities scarcely involved in the decision-making process.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

DM conceptualized and designed the study, structured the methodology, contributed to design the surveys, interpreted the data and information, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. RP wrote sections of the manuscript, and contributed to design and interpret the surveys. II contributed to write sections of the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, finalization, and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Porto Torres Governmental Authorities who participated in our surveys and interviews, and Liliana Recino (expert of the local health communication Office) for her contribution in revising the surveys. We thank the experts involved in the communication-working group for their proactive participation and effective contributions. We also thank Amerigo Zona (Istituto Superiore di Sanità) for his contribution in elaborating the communication tools namely the glossary and the conceptual map of the study, and Alessandra Fabri (Istituto Superiore di Sanità) for the technical support in managing the software for the digital version of the conceptual map of the study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adamonyte, D., and Loots, I. (2017). Regional Office for Europe. World Health Organization. pp. 337–345. Available online at: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/325316 (accessed December 2, 2023).

Bell, D., and Carrick, J. (2018). “Procedural environmental justice,” in The Routledge Handbook of Environmental Justice, 1st ed., eds R. Holifield, J. Chakraborty, and G. Walker (New York, NY: Routledge), 101–112. doi: 10.4324/9781315678986-9

Carrick, J., Bell, D., Fitzsimmons, C., Gray, T., and Stewart, G. (2022). Principles and practical criteria for effective participatory environmental planning and decision-making. J. Environ. Plann. Manage. 66, 2854–2877. doi: 10.1080/09640568.2022.2086857

Clark, S. S., and Miles, M. L. (2021). Assessing the integration of environmental justice and sustainability in practice: a review of the literature. Sustainability 13, 11238. doi: 10.3390/su132011238

Comba, P., and Marsili, D. (2019). Towards integration of epidemiological and social sciences approaches in the study of communities affected by asbestos exposure. Ann. Ist. Super. Sanita. 55, 68–69. doi: 10.4415/ANN_19_01_13

Comba, P., and Pasetto, R. (2022). Health in contaminated sites: the contribution of epidemiological surveillance to the detection of causal links. Comment. Ann. Ist Super Sanita. 58, 223–226. doi: 10.4415/ANN_22_04_01

COST Action IS1408 (2019). “Guidance on the human health impact of industrially contaminated sites,” in Industrially Contaminated Sites and Health Network (ICSHNet), eds I. Iavarone, and M. Martuzzi (COST- European Cooperation in Science and Technology). Available online at: https://www.iss.it/en/-/cost-action-icshnet-networking-/-guidance (accessed December 2, 2023).

Cundy, A. B., Bardos, R. P., Church, A., Puschenreiter, M., Friesl-Hanl, W., Müller, et al. (2013). Developing principles of sustainability and stakeholder engagement for “gentle” remediation approachest: the European context. J. Environ. Manage. 129, 283–291. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2013.07.032

Davis, L. F., Ramirez-Andreotta, M. D., McLain, J. E. T., Kilungo, A., Abrell, L., Buxnner, S., et al. (2018). Increasing environmental health literacy through contextual learning in communities at risk. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 15, 2203. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15102203

Enghel, F. (2014). “Communication, development and social change: future alternatives,” in Global Communication New Agendas in Communication, 1st ed., eds K. Wilkins, J. Straubhaar, and S. Kumar (New York, NY: Routledge Press), 119–141.

Enghel, F. (2017). El problema del éxito en la comunicación para el cambio social. Commons: Rev. Comun. Ciudadanía Digit. 6, 11–22. doi: 10.25267/COMMONS.2017.v6.i1.02

Federation for the Humanities Social Sciences (FUSS) (2017). Approaches to Assessing Impacts in the Humanities and Social Sciences. Ottawa, ON: FHSS. Available online at: https://sfdora.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/impact_report_en_final.pdf (accessed December 2, 2023).

Holifield, R., Chakraborty, J., and Walker, G, . (eds). (2018). The Routledge Handbook of Environmental Justice. New York, NY: Taylor and Francis.

Hoover, E., Renauld, M., Edelstein, M. R., and Brown, P. (2015). Social science collaboration with environmental health. Environ. Health Perspect. 123, 1100–1106. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1409283

Huesca, R. (2008). “Tracing the history of participatory communication approaches to development: a critical appraisal,” in Communication for Development and Social Change, ed. J. Servaes (Paris: UNESCO), 180–199. doi: 10.4135/9788132108474.n9

Iavarone, I., and Pasetto, R. (2018). ICSHNet. Environmental health challenges from industrial contamination. Epidemiol Prev. 42(5–6 Suppl 1), 5–7. doi: 10.19191/EP18.5-6.S1.P005.083

Istituto Superiore di Sanità, ISS. (2022). Salute e Ambiente a Porto Torres. Risultati dello Studio Epidemiologico Descrittivo Della Popolazione Residente. Opuscolo ISS, Istituto Superiore di Sanità. Available online at: https://bit.ly/3xt0ci2 (accessed December 2, 2023).

Kasperson, R. E., Renn, O., Slovic, P., Brown, H. S., Emel, J., Goble, R., et al. (1988). The social amplification of risk: a conceptual framework. Risk Anal. 8, 177–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.1988.tb01168.x

Kasperson, R. E., Webler, T., Ram, B., and Sutton, J. (2022). The social amplification of risk framework: new perspectives. Risk Anal. 42, 1367–1380. doi: 10.1111/risa.13926

Laverack, G. (2016). Public Health. Power, Empowerment and Professional Practice, 3rd ed. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. doi: 10.1007/978-1-137-54604-3

Leach, C., Schroeck, N., Blessman, J., Rorai, V., Cooper-Sargent, M., Lichtenberg, P. A., et al. (2022). Engaged communication of environmental health science: processes and outcomes of urban academic-community partnerships. Appl. Environ. Educ. Commun. 21, 7–22. doi: 10.1080/1533015X.2021.1930609

Lee, C. (2002). Environmental justice: building a unified vision of health and the environment. Environ. Health Perspect. 110, 141–144. doi: 10.1289/ehp.02110s2141

Mannarini, T. (2016). Senso di Comunità. Come e Perché i Legami Contano. New York, NY: McGrawHill Education.

Marsili, D., Battifoglia, E., Bisceglia, L., Fazzo, L., Forti, M., Iavarone, I., et al. (2019a). La comunicazione nei siti contaminati [Communication in contaminated Sites], in SENTIERI: epidemiological study of residents in national priority contaminated sites. Fifth Report [Italian]. Epidemiol Prev. 43(2–3 Suppl. 1), 198–205. doi: 10.19191/EP19.2-3.S1.032

Marsili, D., Fazzo, L., Iavarone, I., and Comba, P. (2017). “Communication plans in contaminated areas as prevention tools for informed policy,” in Public Health Panorama (World Health Organization). Available online at: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/325311 (accessed December 2, 2023).

Marsili, D., Magnani, C., Canepa, A., Bruno, C., Luberto, F., Caputo, A., et al. (2019b). Communication and health education in communities experiencing asbestos risk and health impacts in Italy. Ann. Ist. Super. Sanita 55, 70–79. doi: 10.4415/ANN_19_01_14

Marsili, D., Pasetto, R., Iavarone, I., Fazzo, L., Zona, A., Comba, P., et al. (2021). Fostering environmental health literacy in contaminated sites: national and local experience in Italy from a public health and equity perspective. Front. Commun. 6, 697547. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2021.697547

Martin-Olmedo, P., Sánchez-Cantalejo, C., Ancona, C., Ranzi, A., Bauleo, L., Fletcher, T. I., et al. (2019). Industrial contaminated sites and health: results of a European survey. Epidemiol. Prev. 43, 238–248. doi: 10.19191/EP19.4.A02.069

Martuzzi, M., and Matic, S. (2016). “Industrially contaminated sites and health: challenges for science and policy,” in First Plenary Conference. Industrially Contaminated Sites and Health Network (ICSHNet, COST Action IS1408), eds R. Pasetto, and I. Iavarone (Istituto Superiore di Sanità), 6–8. Rome, October 1-2, 2015. Proceedings. Rapporti ISTISAN 16/27. Available online at: https://www.iss.it/documents/20126/45616/16_27_web.pdf/e3c40ddd-80db-9b64-0ee7-39f1cb1f4abc?t=1581099206825

Mogensen, F. (1997). Critical thinking: a central element in developing action competence in health and environmental education. Health Educ. Res. 12, 429–436. doi: 10.1093/her/12.4.429

Pasetto, R., and Iavarone, I. (2020). “Environmental justice in industrially contaminated sites. From the development of a national surveillance system to the birth of an international network,” in Toxic Truths: Environmental Justice and Citizen Science in a Post-truth Age, 1st ed., eds A. Mah, and T. Davis (Manchester: Manchester University Press), 199–219. doi: 10.7765/9781526137005.00023

Pasetto, R., and Innocenti Malini, G. (2022). Promoting environmental justice in contaminated areas by combining environmental public health and community theatre practices. Futures 142, 103111. doi: 10.1016/j.futures.2022.103011

Pasetto, R., and Marsili, D. (2023). Environmental justice promotion in the Italian contaminated sites through the national epidemiological surveillance system SENTIERI [Italian]. Epidemiol. Prev. 47(1-2 Suppl 1), 375–384. doi: 10.19191/EP23.1-2-S1.010

Pasetto, R., Mattioli, B., and Marsili, D. (2019). Environmental justice in industrially contaminated sites. A review of scientific evidence in the WHO European region. IJERPH, 16, pii, 998. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16060998

Pasetto, R., Zona, A., Marsili, D., and Fabri, A. (2022). Health Profile of a Community Affected by Industrial Contamination. The case study of Porto Torres (Sardinia, Italy): Environmental-health Assessment, Epidemiology and Communication. [Italian] Profilo di Salute di una Comunità Interessata da Contaminazione Industrial. Il caso di Porto Torres: Valutazioni Ambiente-salute, Epidemiologia e Comunicazione. Istituto Superiore di Sanità, Rapporti ISTISAN 22/13, Available online at: https://www.iss.it/documents/20126/6682486/22-13+web.pdf/746ad52f-150c-ca89-0078-8e448558c6d3?t=1655477200491 (accessed December 2, 2023).

Ramírez, A. S., Ramondt, S., Van Bogart, K., and Perez-Zuniga, R. (2019). Public awareness of air pollution and health threats: challenges and opportunities for communication strategies to improve environmental health literacy. J. Health Commun. 24, 75–83. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2019.1574320

Ramirez-Andreotta, M. D., Brody, J. G., Lothrop, N., Loh, M., Beamer, P.I., and Brown, P. (2016). Improving environmental health literacy and justice through environmental exposure results communication. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 13, 690. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13070690

Ramirez-Andreotta, M. D., Brusseau, M. L., Artiola, J. F., Maier, R. M., and Gandolfi, A. J. (2014). Environmental research translation: enhancing interactions with communities at contaminated sites. Sci. Total Environ. 497–498, 651–664. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.08.021

Raphael, C. (2019). Engaged communication scholarship for environmental justice: a research agenda. Environ. Commun. 13, 1–21. doi: 10.1080/17524032.2019.1591478

Renn, O. (2010). The contribution of different types of knowledge towards understanding, sharing and communication risk concepts. Catalan J. Commun. Cult. Stud. 2, 177–195. doi: 10.1386/cjcs.2.2.177_1

Sabatini, F. (2019). Culture as a fourth pillar of sustainable development. Perspectives for integration, paradigms for action. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 8, 31. doi: 10.14207/ejsd.2019.v8n3p31

Schlosberg, D. (2007). Defining Environmental Justice. Theories, Movements, and Nature. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199286294.001.0001

Shastitko, A., and Fakhitova, A. (2015). Monotowns: a new take on the old problem. Balt. Reg. 1, 4–24. doi: 10.5922/2079-8555-2015-1-1

Solar, O., and Irwin, A. (2010). “A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health,” in Social Determinants of Health Discussion Paper 2 (Policy and Practice) (Geneva: WHO). Available online at: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/44489/9789241500852_eng.pdf?isAllowed=y&sequence=1 (accessed December 2, 2023).

Topping, K., Buchs, C., Duran, D., and van Keer, H. (2017). Effective Peer Learning. From principles to Practical Implementation. New York, NY: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315695471

Tsuji, S. R. J. (2021). Indigenous environmental justice and sustainability: what is environmental assimilation? Sustainability 13, 8382. doi: 10.3390/su13158382

Tufte, T., and Mefalopulos, P. (2009). Participatory Communication: A Practical Guide. World Bank Working Paper; no. 170. Washington, DC: World Bank. Available online at: http://hdl.handle.net/10986/5940 (accessed December 2, 2023).

Walker, G. (2012). Environmental Justice: Concepts, Evidence and Politics. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203610671

World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe (2013a). Health and Environment: Communicating the Risks. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe. Available online at: https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0011/233759/e96930.pdf (accessed December 2, 2023).

World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe (2013b). Contaminated Site and Health. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe. Available online at: https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/186240/e96843e.pdf (accessed December 2, 2023).

World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe (2021a). Effective Risk Communication for Environment and Health: A Strategic Report on Recent Trends, Theories and Concepts. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0. IGO. Available online at: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/349338/WHO-EURO-2021-4208-43967-61972-eng.pdf?sequence=3andisAllowed=y

World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe (2021b). Urban Redevelopment of Contaminated Sites: A Review of Scientific Evidence and Practical Knowledge on Environmental and Health Issues. World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0. IGO. Available online at: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/340944

Zona, A., Fazzo, L., Benedetti, M., Bruno, C., Vecchi, S., Pasetto, R., et al. (2023). SENTIERI - Studio epidemiologico nazionale dei territori e degli insediamenti esposti a rischio da inquinamento. Sesto Rapporto [SENTIERI - Epidemiological Study of Residents in National Priority Contaminated Sites. Sixth Report]. Epidemiol. Prev. 47(1–2 Suppl 1), 1–286. doi: 10.19191/EP23.1-2-S1.003

Keywords: participative communication process, industrially contaminated sites, stakeholders' engagement, social capacity, environmental justice

Citation: Marsili D, Pasetto R and Iavarone I (2023) Environmental public health communication to engage stakeholders and foster social capacity in poorly involved communities living in industrial contaminated sites: the case study of Porto Torres (Italy). Front. Commun. 8:1217427. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2023.1217427

Received: 05 May 2023; Accepted: 27 November 2023;

Published: 15 December 2023.

Edited by:

John Parrish-Sprowl, Purdue University Indianapolis, United StatesReviewed by:

Emiliano Guaraldo, Ca' Foscari University of Venice, ItalyPatrick Murphy, Temple University, United States

Copyright © 2023 Marsili, Pasetto and Iavarone. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Daniela Marsili, ZGFuaWVsYS5tYXJzaWxpQGlzcy5pdA==

Daniela Marsili

Daniela Marsili Roberto Pasetto1,2

Roberto Pasetto1,2