94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Commun. , 26 October 2023

Sec. Health Communication

Volume 8 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2023.1205883

This article is part of the Research Topic Integrating Digital Health Technologies in Clinical Practice and Everyday Life: Unfolding Innovative Communication Practices View all 9 articles

Introduction: Technology-enabled treatments (TET) have emerged in pediatric care as an effective solution for early and intensive intervention. There is a lack of research in the field of digitalized health care on the interaction between professionals and parents on which these treatments are based, and at the same time too little is known about the impact of remoteness and technology on interaction in the field of health communication.

Method: We use a conversation analytical approach to examine the interaction between occupational therapists and parents in one such treatment on a micro level, with a focus on advice-giving and the role of professional and parental authorities in this.

Results: Our analyses show that professionals in TET work together with the parents of children in treatment to achieve children's rehabilitation goals. In advice-giving in TET, the professionals interactionally downgrade their epistemic and deontic authority, orienting toward the imposition on parents inherent to advice and orienting toward parental authority.

Discussion: By describing three different patterns of the interactional unfolding of advice-giving, we provide insights into how professionals carefully initiate and return to advice and show how this activity is shaped by the technology used for the interaction. Our study offers a better understanding of how paramedical professionals practice their profession given remoteness and technology and what TET entails interactionally in terms of advice-giving.

In an increasingly digitalized society, people incorporate digital technologies into both their work and everyday lives. This also holds for the field of paramedical care. Digitalization implies that treatments increasingly take place remotely, in a setting where the professional and the care recipient are not in the same physical place. This means that communication about care also increasingly takes place through technological means, such as videoconferencing, email, chat, or instant messaging. We refer to these treatments carried out remotely using technology as “technology-enabled treatment” (TET).

Digitalization of paramedical treatments does not only take place in adult care but also in pediatric care, where communication about treatment primarily involves professionals and parents of underage patients. An example of a pediatric TET is the home-based upper limb training program using a video coaching approach for infants and toddlers with cerebral palsy (Verhaegh et al., 2022, 2023). In this treatment, interaction between paramedical professionals and parents of young patients takes place via a secure website. Parents make videos of their infant or toddler while they practice together in the home environment. Professionals watch the videos parents post on the website and provide written feedback. This enables them to share with parents descriptions of what they observe in the videos, evaluate the activities, and give parents advice for future actions. The collaborative work between professionals and parents is crucial in this case of TET: they depend on each other to achieve the child's rehabilitation goals. How to achieve these goals is negotiated in the digital interaction between the professional and parent on the website.

Previous research on TET shows, among other things, that it is effective for the rehabilitation of very young children with this type of motor disability (Verhaegh et al., 2023) and that parents evaluate the treatment positively (Verhaegh et al., 2022). However, there is a lack of research addressing the interactional nature of TET and the impact of remoteness and use of technology on the interaction between professionals and parents. We use conversation analysis (CA) to examine the interaction between professionals and parents in TET on a microlevel to unravel how remoteness and technology affect the interaction between parent, child, and professional and their therapeutic work. CA has proven to be a fruitful approach in research on the interaction between healthcare professionals and patients (e.g., Pilnick and Coleman, 2003; Pino et al., 2021) and interaction between healthcare professionals and parents of young patients more specifically (e.g., Heritage and Sefi, 1992; Stivers and Timmermans, 2020). In addition, CA is increasingly used as a method for analyzing digital interaction (Meredith et al., 2021).

In this study, we focus on an aspect of interaction that plays an important role in the treatment described above, i.e., the sequential unfolding of advice. Our focus on advice-giving and implementation holds particular importance as this interactional activity constitutes a crucial component of care professionals' everyday institutional practice and can impact patients' and parents' compliance with therapies. Much is already known about advice-giving in interaction, including in medical settings. Previous studies have shown that advice-giving is potentially a problematic activity (see, e.g., Heritage and Sefi, 1992; Heritage and Lindstrom, 1998). By offering advice, the advice-giver implies that they have knowledge or insight that the advice-recipient lacks, thus positioning the participants asymmetrically (Vehviläinen, 2012). The assumed or established asymmetries between advice-giver and advice-recipient can make advice-giving problematic because it can suggest that the advice-giver assumes that the recipient of the advice did not already know what to do, thereby problematizing their competence (Shaw and Hepburn, 2013, p. 348). This also holds for institutional settings such as healthcare (Heritage and Sefi, 1992; Jefferson and Lee, 1992; Kinnell and Maynard, 1996; Waring, 2007a). The tension between professional and lay expertise is specifically marked in care situations, where professionals and patients or their caregivers share some domains of knowledge, to which the care receivers have primary access (Heritage, 2012a).

Very little is known about advice-giving in TET. Studies in the fields of authority and advice-giving in medical interactions have focused on face-to-face interactions, and therefore, a systematic understanding of how technology shapes these interactional practices is still lacking. In an institutional setting, expertise is intrinsically part of the competence each professional in a particular domain may claim as compared to a layperson (Stevanovic, 2021). Studies show that phenomena such as web-based self-diagnosis, parental pressure in pediatric settings, and their resistance to advice (Stivers, 2005; Stivers and Timmermans, 2020; Caronia and Ranzani, 2023) point to an impending consequence of the redistribution of epistemic and deontic rights, resulting in a narrower gap between professional and lay vision (Goodwin, 1994). However, it remains unclear whether the asymmetries observed in physical treatment settings also hold in virtual settings. Previous research shows that parents who assist their children during home-based treatments report increased competence and professional knowledge (Novak, 2011; Verhaegh et al., 2022). This raises questions about how professionals deal with what the changing (a)symmetry TET may entail. How do professionals orient to parental authority in advice-giving? How does this relate to their own displayed authority?

Our case study aims to describe how remoteness and technology affect advice-giving and the subsequent interaction through a detailed analysis of e-text messages in which advice is provided by occupational therapists, and of videos made by parents in which implementation of advice becomes visible. Previous empirical studies of advice in interaction have focused on advice-giving and receiving (e.g., accepting, resisting, or rejecting) rather than on implementing advice. By studying the implementation or non-implementation of advised activities and how this is responded to, in addition to advice-giving, we aim to describe the unfolding of advice. In this way, we show how parents and occupational therapists work together to achieve children's rehabilitation goals in TET. The analysis specifically focuses on how and to what extent authority is displayed in the technology-enabled interactions between professionals and parents during the treatment. Thus, we provide a better understanding of paramedical professional practices by identifying advice dynamics in digitalized paramedical interaction.

Building on previous research on authority in social interaction (e.g., Heritage and Clayman, 2010; Heritage and Raymond, 2012; Stevanovic, 2015) and more specifically on advice-giving in interaction in healthcare (e.g., Heritage and Sefi, 1992; Heritage and Lindstrom, 1998; Pilnick, 2001, 2003), in this article, we empirically illustrate how these two concepts are related when occupational therapists practice their profession in TET. In this way, our research contributes to the study of advice-giving in technology-mediated interactions, as well as the management of epistemic and deontic authority among professionals and laypersons in digitalized social interactions. We begin by considering conversation analytic work on authority and advice-giving, to examine the relationship between the two.

Authority, the concept of articulating one's specific set of skills and knowledge, is a thoroughly social phenomenon that is constantly achieved and negotiated in interaction (Stevanovic, 2021). Studies of authority in institutional interaction (e.g., Heritage and Sefi, 1992; Boyd, 1998; Perakyla, 1998; Peräkylä, 2002; Heritage, 2005) have shown that by analyzing the microdetails of turn-by-turn sequential unfolding of interaction, participants' orientations to authority can be observed (Heritage and Clayman, 2010). Two components of authority are distinguished in this: epistemic authority and deontic authority (Bocheński, 1974; Heritage and Raymond, 2012; Stevanovic, 2015). Whereas epistemic authority relates to expertise based on knowledge in a particular field, i.e., knowing how the world is, deontic authority relates to the right or capacity to determine action, and thus to determine how the world ought to be (Stevanovic and Peräkylä, 2012). The knowledge or power expressed in the linguistic form of an utterance is described as an authoritative stance (Stevanovic and Peräkylä, 2014). A person's authoritative stance, whether epistemic or deontic, reflects the level of authority a person demonstrates publicly in interaction, which is established through his or her (linguistic) behavior from moment to moment.

From the above, it can be inferred that both epistemic and deontic authority are relevant in advice-giving, for which we follow Heritage and Sefi's (1992) understanding of advice as describing, recommending, or otherwise forwarding a preferred course of future action. By providing advice, the advice-giver displays having the knowledge about what the preferred course of action is, thereby claiming epistemic authority over the matter, and the right to tell someone to undertake this course of action, thus claiming deontic authority. As a result, advice-giving as an activity in itself establishes an asymmetry between participants (Hutchby, 1995), in that the advice-giver is positioned as more knowledgeable and powerful (and thus more authoritative) than the receiver of the advice. Additionally, when advice is given in an institutional setting such as healthcare, the direction of asymmetry between participants may be assumed: a medical professional typically has greater epistemic and deontic authority regarding a future course of action than a patient (Heritage, 2012b; Stevanovic and Peräkylä, 2012). This is reflected in a scenario where the professional is usually the one who initiates advice and thus assumes the role of advice-giver, while the patient, or caregiver, is assigned the role of advice-recipient.

Authority is not global, but rather linked to specific areas of knowledge or action (Stevanovic and Peräkylä, 2012). Whereas a medical professional has authority in a medical area, a patient has authority regarding issues related to their own body, and parents in turn typically have authority regarding their own child (Versteeg and Te Molder, 2018). The distribution of authoritative rights is also gradual: it is not the case that one person necessarily has absolute authority and another none (Stevanovic and Peräkylä, 2012). These two features of authority (locality and graduality) together mean that epistemic and deontic rights vary from domain to domain and hence a person may have more rights to decide on a future course of action in some areas of action than in others (Stevanovic and Peräkylä, 2012).

Both professionals and parents of patients have epistemic and deontic rights and responsibilities in different domains (Stivers and Timmermans, 2020). The epistemic domain of occupational therapists' authority, referring to what they can be expected to know, how they know it, and whether they have the right to describe it (Heritage and Raymond, 2005), is grounded in paramedical expert knowledge about interpretation of movements, clinical diagnosis, and assessment. They exercise authority on deontic grounds when they recommend patients or their parents regarding future actions. Patients also have domains of authority: based on their experience and patient-specific knowledge (Pomerantz, 1980; Mishler, 1984; Sacks, 1984). In the case of infants and toddlers, this holds for their parents: they possess relevant knowledge about their child and have the right to decide about treatment (Stivers and Timmermans, 2020). The epistemic domain of parents' authority includes their child's experiences, preferences, perceptions, and in-depth knowledge about the health of their child. They have deontic primacy over the choices they make on behalf of their child, including implementation of treatment and compliance with advice (Stivers and Timmermans, 2020).

Since advice-giving is an essential part of medical professional's routine work practices, it is not a surprise that a considerable body of CA literature has examined advice-giving and -receiving in healthcare over the past 30 years (e.g., Heritage and Sefi, 1992; Jefferson and Lee, 1992; Silverman et al., 1992; Kinnell and Maynard, 1996; Silverman, 1997; Heritage and Lindstrom, 1998; Heritage and Lindström, 2012; Leppänen, 1998; Pilnick, 2001, 2003; Pilnick and Coleman, 2003, 2010; Emmison and Firth, 2012; Pudlinski, 2012; Zayts and Schnurr, 2012; Landqvist, 2014; Bloch and Antaki, 2022). The studies that focus on interactions between healthcare professionals and parents show that advice can be a problematic activity and that parental competence is at stake in advice regarding children.

In their seminal work on face-to-face interactions between British health visitors (HVs) and first-time mothers, Heritage and Sefi (1992) showed that HVs generally initiated advice without a clear indication that there was a problem or that advice was desired. Moreover, it appeared that HVs made little effort to adapt advice-giving to the circumstances of individual mothers or to recognize their competencies and capacity for personal decision-making. In terms of advice uptake, Heritage and Sefi observed that mothers used marked and unmarked acknowledgments, but also explicitly resisted advice, by asserting their knowledge or competence. Additionally, it was found that HVs' advice was more readily accepted when a stepwise approach was taken, with the advice fitted to the mother's perspective. In a related study, Heritage and Lindstrom (1998) highlighted the moral dimension of these advice conversations by showing that moral standards about what makes a good mother are implicitly the topic of the conversations. Pilnick (2001, 2003) showed that parents of patients who receive long-term treatment often displayed their competence in pharmacy consultations at a pediatric oncology outpatient clinic. They did this by interrupting the pharmacist's turn (Pilnick, 2001), and by pre-empting, summarizing, or extending the pharmacist's turn (Pilnick, 2003). These expressions of competence, which parents based on their knowledge, gave shape to the moral parental obligation to care for children, accompanied by a desire to demonstrate proper fulfillment of that obligation.

These previous studies highlight that giving advice creates an asymmetry between professional and parent where the professional is in a position of professional authority, which can lead to resistance or reluctance on the part of parents to accept the advice and to displays of competence. Moreover, previous empirical research on treatment recommendations showed that when parents resist a recommendation, professionals tend to accommodate their concerns, which usually leads to a modification of the recommendation (Stivers and Timmermans, 2020). TET centers on the parent's home sphere and their knowledge and experience and thus bolsters their epistemic authority vis-à-vis professionals. It is not yet known what this increase in experience and epistemic authority means in the interaction during TET, especially in the uptake and implementation of advice. As discussed, advice can be perceived as a threat to the parent's authority regarding their own child. Therefore, medical professionals often choose to take a less straightforward path when giving advice (Couture, 2006; Zayts and Schnurr, 2012). Some linguistic forms of advice provide little optionality for the recipient to do the suggested action, such as an imperative, verb with obligation, or tag question (Shaw, 2013). However, there are also less constraining forms of advice that offer the recipient more contingency. Advice-givers can mitigate their advice and thereby reduce asymmetry, minimizing the potential threat to the recipient's face and achieving further interactional goals (Caffi, 1999).

While considerable CA research has thus been carried out on advice-giving and the role of authority in healthcare settings, much less is known about written advice in a technology-enabled healthcare context, especially from a CA perspective. However, CA has a solid history of examining technology-mediated interaction, focusing on how participants use different media for different types of social interactions (for recent reviews, see Seuren et al., forthcoming; Arminen et al., 2016; Mlynár et al., 2018). The analytical premise of CA when analyzing technology-mediated interaction is that technology does not determine how people act. The focus is on how technology is (made) procedurally consequential for the interaction (Arminen et al., 2016). TET entails certain affordances (Hutchby, 2001), such as rehearsability (the possibility of editing a message before sending it) and reprocessability (the possibility of rereading messages) (see Baralou and Tsoukas, 2015). At the same time, the technology also provides certain constraints, including, for example, not being able to see the direct uptake of advice (because of the asynchronicity of the setting and the modality of text). Little is known about how these affordances and constraints involved in TET impact advice-giving and the subsequent interaction. Thus, while it cannot be assumed unequivocally that technology-mediated interaction necessarily differs from face-to-face interaction (Arminen et al., 2016), it is not clear to what extent research on advice and the role of authority therein in healthcare interactions translates to remote services (Lopriore et al., 2017).

Literature on written advice in other digital contexts reports that advice is not bound to a limited set of linguistic realizations but consists of multifaceted interactions, taking place within longer narrative responses that include explanation and elaboration (e.g., DeCapua and Dunham, 2012). It is also known that the face-threatening potential of written advice is high and that relational strategies are essential in the enactment of advice in these settings (Locher and Limberg, 2012). Analyses of written, technology-mediated expert advice in the context of health advice columns showed that there is an ideal of non-directiveness to which interactants orient themselves as a norm when giving advice in this setting (Locher, 2006, 2010). Analyses of written, technology-mediated expert advice in educational settings showed that linguistic mitigation is exploited in advice-giving (Hyland and Hyland, 2001, 2012), i.e., strategies adopted to “reduce risks for interactants at various levels, e.g., risks of self-contradiction, refusal, losing face, conflict, and so forth” (Caffi, 1999, p. 882). This demonstrates that professionals are aware of the affective, face-threatening nature of their comments. Furthermore, in analyzing written advice from prospective teachers to mothers of young children, it was shown that assessments were often given before the suggestion of a future course of action, to understand the given context better; it was also shown that the criticism was often combined with a positive comment and that the advice was often elaborated on (DeCapua and Dunham, 2012). These studies demonstrate the complexity of advice in discourse and underscore the considerable relational work that is done in technology-enabled settings. Similar findings have been reported in text-based CA studies of counseling (Stommel, 2012) and cognitive behavioral therapy (Eckberg et al., 2013).

In sum, advice-giving in interaction is studied extensively, but the impact of remoteness and technology on advice-giving in TET is unknown. In addition, CA studies have focused on the uptake of advice, but not on its actual implementation visible to the professional, and how this affects the sequential unfolding of the interaction. Moreover, there is no available literature on the role of professional and parental authorities in the context of TET. In this article, we ask How do occupational therapists give advice to parents in the setting of a technology-enabled treatment, and how do these advice sequences unfold? By answering this question, we aim to show how professionals do their work, given the remoteness and the technology, and what TET may entail interactionally.

The TET we studied is a home-based upper limb training program offered by a pediatric rehabilitation unit in the Netherlands. The infants and toddlers receiving this treatment have some form of cerebral palsy (CP), the most common physical disability in children. Children with CP have motor function disorders on one or both sides of their body, and as a result, they often avoid the use of their affected upper limbs (Oskoui et al., 2013). To enhance and improve the use of these limbs in children with CP, constraint-induced movement therapy (CIMT) and bimanual training (BiT) are effective interventions, provided that the intensity of training is sufficient and that treatment preferably begins at an early age (McIntyre et al., 2011; Hoare et al., 2019). Home-based TET programs have been proven to be an effective solution for this purpose (Novak and Berry, 2014; Verhaegh et al., 2023), since training in the home environment, implemented by parents, allows intensive training from as young as 4 months of age.

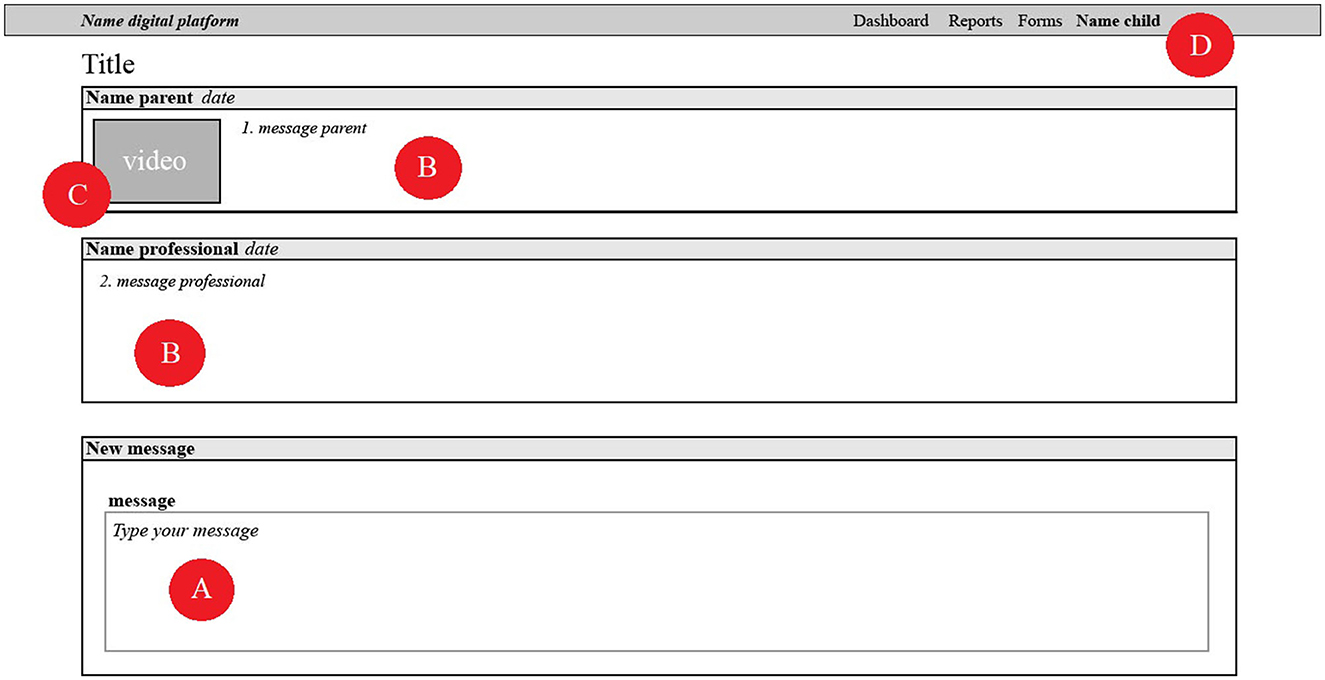

In TET, professionals work together with the parents of affected children to bring treatment to fruition. Parents are expected to do specific therapeutic activities with their child in the home environment for at least 30 min a day. Furthermore, they are asked to make videos of their training sessions at home. Throughout their child's treatment, they are digitally supported and coached by one or more paramedical professionals. Coaching takes place via a secure website specifically designed for this purpose (see Figure 1), where parents upload their videos and professionals provide electronically written feedback to parents after watching the videos (Verhaegh et al., 2022). Parents can read the feedback and, in turn, implement any advice-given during the next practice (and filming) opportunity. Parents also can write messages to professionals, ask questions, address problems, etc. Because the website archives messages, parents and professionals can reinspect their videos and messages. Professionals are not only able to observe the children's movements in the videos but also whether their advice is acted upon by the parents in follow-up videos. At the beginning of the treatment, professionals and parents agree on the frequency with which videos and messages are sent and responded to. Usually, parents send videos and messages more often than professionals reply to them.

Figure 1. Interface of the website. (A) Is the field where users are able to type a new message. (B) Is where previous messages can be read. If a user clicks on the video (C), it comes into view enlarged. Via (D), a user navigates to previous messages elsewhere on the website (for example, sent during previous treatment cycles).

Our data were collected from the archive of the TET program described above. Data collection took place from October 2021 till February 2022. All participants involved in the interactions (parents and professionals) gave informed consent to use their previously generated data (videos and electronic text messages). The treatment (cycle) of the children in question had been completed before data collection. Our analysis concerns the video and e-text data from the cases of seven different infants and toddlers. In total, eight different professionals were involved in these seven cases, and seven parents or parent couples. The data include 376 videos and 799 e-text messages. The video durations were between 3 s and almost 28 min, with an average duration of 5 min and 27 s. Of the 799 e-text messages, 291 were sent by occupational therapists (average 149 words per message), 46 by primary physical therapists (average 95 words per message), and 462 by parents (average 33 words per message). For the current study, we analyzed videos made by parents as well as the corresponding messages and feedback messages written by occupational therapists (see overview in Table 1).

Our analysis is informed by CA, a method typically used to examine the sequential nature of the interaction (Heritage, 1984; Schegloff, 2007; Ten Have, 2007). We analyzed sequences of videos and e-text messages in detail to discern patterns in advice delivery and compliance. The sequential context of interaction (the prime object of investigation in CA) is of crucial importance in digital interaction, just as in talk/spoken interaction (Stommel, 2012). However, there are differences between spoken interaction and the interaction we analyze in this article. For example, the written interactions in the setting under scrutiny are asynchronous, which imposes constraints such as the lack of possibilities for the participants to mutually monitor each other and to adjust their interactional contributions “on the fly,” in response to the recipient's ongoing (verbal or embodied) reactions. In addition to the constraints that technologies can pose, they also have distinct features, which afford users of the technology with particular types of interactions, depending on the context and purpose for which they are used (Hutchby, 2001; Baralou and Tsoukas, 2015). In our analysis, we therefore take into account the affordances of the website that provides the context for the TET (Figure 1). For instance, the website must be high in reprocessability, as messages are stored and retrievable on the website, allowing participants to revisit previous messages (Baralou and Tsoukas, 2015, p. 599). This means that in the setting of this treatment, the interactional context of each message and video is considered an available record for participants (Stommel, 2012), while in face-to-face interaction, this record is not available to participants (Gibson, 2009). Thus, when writing messages or recording videos, both professionals and parents have a complete record of the interaction, which they can refer back to, check, etc., when composing a new message and/or video.

The current analysis is based on a collection of advice sequences initiated by occupational therapists. What actually constitutes advice in this particular setting was an exploratory focus (see discussion) rather than a pre-defined concept. However, as a starting point to identify instances of advice in the corpus, we relied on Heritage and Sefi's (1992, p. 368) rather generic definition of advice as the interactional practice through which a professional “describes, recommends, or otherwise forwards a preferred course of future action.” To supplement the identification of advice in the text messages, the parts of the videos that the advice linked to were viewed to properly grasp what the advice referred to. The following step consisted of analyzing what happened in reaction to the advice. Videos that followed the formulated advice were therefore examined to see whether they showed behavior in which parents acted in accordance with the advice they had received. In addition, we examined messages from parents to see if and how there was a textual response to written advice. The next step was to look at the therapist's responsive message with feedback on the video. Videos and e-text messages were thus always studied in relation to one another. Although the responding videos were viewed in their entirety, only the relevant excerpts were directly analyzed in detail. The video excerpts were first roughly categorized based on whether the advice could be seen to be complied with or not. When different patterns emerged, sequences of:

(1) Professionals' advice-giving (text message).

(2) Parents' advice implementation (video excerpt or text message).

(3) Professionals' feedback (text message).

were constructed, transcribed (in the case of video)1, and analyzed in detail. The analysis focused on displays of and orientations to authority, which emerged from the inductive data-driven conversation analytic process (see Ten Have, 2007). We then examined how the specificities of the website used for the interaction afford these practices. The concept of affordances allows for the examination of the interaction itself first, after which it can be explored if and how that interaction orients to the relevant technological features of the medium (Arminen et al., 2016; Meredith et al., 2021). Initial analysis was conducted by the first author and refined through discussion and data sessions with the fourth author. In the findings section, we discuss in detail three advice sequences (advice message—video or message parent—advice message) that exemplify three different patterns of how advice is given, complied with, and followed up on in our dataset. These exemplary cases were presented and discussed in data sessions with other researchers. In our analysis, we particularly focus on the interactional work accomplished by occupational therapists in downgrading their own epistemic and deontic authority and acknowledging the epistemic and deontic authority of the parents they work with. It is important to state that we consider collaboration a cooperative interactional work realized by both parents and professionals, although for this article, we particularly stress the work carried out by professionals. However, as our analysis will show, this collaborative work is mutually accomplished by both parties in the interaction and is not just the result of the professionals' work.

Because our analysis focuses on specific aspects of feedback messages and therefore omits parts of them, this section briefly presents the overall structure of feedback messages. The messages from occupational therapists on the website are structured in a relatively consistent way (see Table 2). Variation between messages may consist of several components being omitted, presented in a different order, or components that are repeated several times.

Our analysis shows that in this TET, professionals and parents work together to achieve the child's individual rehabilitation goals by giving advice and implementing advice. When occupational therapists position themselves asymmetrically in relation to the parent by giving advice, i.e., as someone with an authoritative position, they downgrade this authority by using various linguistic strategies that embody a less knowledgeable or powerful stance. This displays an orientation to the imposition on the parent inherent to the advice. In what follows, we narrow the discussion down to three patterns of advice in this TET setting, showing three different ways in which an advice sequence can unfold. We present three example cases to illustrate our findings.2 In the first case, advice from the occupational therapist is implemented by the parent. This represents the most common pattern in our data. In the second case, compliance with the advice is not observable in the video, upon which the professional reiterates the advice. In the third case, compliance with the advice is also not observable in the video but parents account for this in a message, upon which the professional modifies the advice.

The first pattern to be discussed illustrates what advice-giving in TET looks like when advice is initiated by the professional and the advice is subsequently implemented by the parent.

Extract 1 is taken from the treatment of Nolan, an infant who has been in treatment for about 5 months and is practicing with two hands (BiT) at this point of the treatment. The extract is the first part of a feedback message written by the occupational therapist.

The professional opens the message without greetings, general comments, or compliments, moves that are normally found at the beginning of a feedback message (see Table 2). The omission of these opening moves suggests that a certain collaborative relationship has already been established between professional and parent, and our data accordingly show that these elements are never omitted when treatment has just begun. The first elements (1–3 in Table 2) can be seen as relational work in advice-giving, which is arguably less essential when treatment has been underway for some time.3

Extract 1 instead begins with reference to the specific video the message responds to (2.7, line 1) by quoting the parent's title of the video (week 2.7, data not shown here). After this, the professional describes what they have seen in this video (line 2), initially quite general (weer samen aan het oefenen “practicing together again,” line 2), then more specific (pakken “grabbing,” line 2; loslaten “releasing,” met de intentie met beide handen naar het midden te komen “with the intention to come to the middle with both hands,” line 3; loslaat ““releases,” line 4). The professional combines these observations with evaluations (mooi “nicely,” line 2; mooi “nice,” line 3), and thereby indirectly offers an assessment of the child. In giving these evaluative descriptions, the professional displays their paramedical expert knowledge and the right to describe this, and thus claims epistemic authority (cf. Heritage and Raymond, 2012). The website affords the possibility of such specific evaluative descriptions. The videos allow the professional to observe the therapeutic activities between parent and child without being physically present. The website further allows the video to be paused and parts of it to be replayed. This, in turn, allows for very specific written descriptions and evaluations of the movements and activities seen on camera.

The description ends with a time stamp referring to a precise time in the video (0:29, line 4), shown in Figure 2. The professional thus indicates a very specific moment in the video when something remarkable happens: the child releasing the orange toy in the parent's hand in a specific way (indicated by hoe “how,” line 3). Note here that the time stamp is used as a specification, since “orange toy” (oranje speeltje, line 4) already implicitly refers to the moment when the child is practicing with that particular toy. It is at this point in the video where the parent can see how it is that Nolan is releasing the toy, i.e., what a “nice” way of releasing looks like, according to the professional. The time stamp, an affordance of the technology used for the interaction, invites the parent to watch that part of the video as visual support for the advice that follows (lines 5–6): the way Nolan is releasing the toy in the parent's hand might be a signal that the parent can start provoking “more targeted release” (gerichter loslaten, line 5), if possible in combination with Nolan looking at his hand while releasing the toy (i.e., paying attention to it). The advice is initially framed as building on the child's (and parent's) success in achieving a rehabilitation goal that is visible on camera: releasing the toy in a nice way. Moreover, the initiation of the advice is specifically shaped by the technology used for giving advice, because of the time stamp indicating a successful moment in the video, that the parent can return to, and based on which a new activity is advised. By providing advice, the professional places themself in an asymmetrical position toward the parent, claiming access to the relevant knowledge and rights to propose a future action (Heritage, 2012b; Stevanovic and Peräkylä, 2012), and thus displaying both epistemic and deontic authorities.

However, the authoritative stance reflected in the linguistic form of the utterance can be expressed with stronger or weaker force. In Extract 1, the advice is provided through an indirect construction (lines 5–6). Not directly addressing the recipient of the advice, i.e., the person who would be doing the action, creates some distance between the professional as the advice-giver and the parent as the recipient of the advice (cf. DeCapua and Dunham, 2012). This limits the face-threatening potential of advice-giving and softens the imposition it may have on the parent (cf. the alternative formulation: “Possibly that is a signal that you can also start to provoke a more targeted release”). The use of brackets around “where possible combined with looking” and the lexical choice “waar mogelijk” (“where possible,” lines 5–6) mitigates the advice. The utterance, therefore, embodies a downgraded deontic stance.

Furthermore, the use of “possibly” (mogelijk, line 5) weakens the professional's epistemic stance. The child's movements might be interpreted as a signal for a “next step” in the treatment, but the professional displays some cautiousness regarding the appropriateness of this future course of action. This downplay of authority may also be related to an orientation to the advice-recipients' authority: the parent has more experience practicing with the child than the professional and may have a different interpretation of the signals shown by Nolan based on this experience.

The advice is concretized with an explanation of how to start provoking a more targeted release (lines 7–8). This part of the advice can also be said to resemble instruction-giving as it seems designed “to get someone to do something” (Goodwin, 2006, p. 517). Unlike earlier, the parent is addressed directly with je (“you,” line 7), which arguably creates less distance between the advice-giver and the recipient as compared to the potential alternative of using an indirect construction. There is now less ambiguity about who should implement the advised action. Still, this substantiation of the advice is presented in a way that conveys optionality. Two means contribute to this: first, the conditional modal verb “could” (zou kunnen, line 7), which treats the proposed future action as an option, rather than an obligation (see Stevanovic and Peräkylä, 2012); second, “or the like” (o.i.d., line 7) marks the salad bowl as an option among others, which is reinforced by explicating two other options: “Old empty paint (or milk powder) cans” (oude lege verf (of melkpoeder)blikken, line 8). Listing different options makes the advice concrete rather than general, minimizing possible resistance to the advice (see Waring, 2007b). In addition, the optionality reduces the imposition on the parent to follow the exact advice and leaves some latitude for the parent to implement the advice according to their circumstances (i.e., if you do not have a salad bowl at home, you can also use an empty paint can). Note that although conveying optionality reduces asymmetry, explicating multiple options simultaneously strengthens the normative obligation to try at least one of the options.

The professional further elaborates on the advice by explaining how the proposed course of action would contribute to Nolan's rehabilitation process: i.e., it may help Nolan to progress from accidental to conscious release (lines 9–10). By providing the rationale behind the advice, the professional displays accountability toward advice-giving (cf. Stivers, 2005; Waring, 2007b). Rather than advice being deontically mitigated, this is a prediction that is epistemically downgraded through some of the same means (the mitigators mogelijk “possibly” and iets “a bit,” line 9). Important for our discussion here is that this explanation is deployed by the professional to substantiate the importance of the advice as it is essential to convince the parent of the benefits of advice implementation. The asynchronous nature of the technology used makes it all the more necessary for the professional to do this as soon as the advice has been given (cf. Licoppe, 2021).

In the next video of Nolan posted on the website, the parent embodies compliance with the professional's advice (Extract 2).4

At 02:20, the parent evaluates the child's conduct of grabbing the rattle with “very good.” At the same time, the parent grabs a salad bowl and holds it under the child's right hand, thus implementing the advice (“taking a large salad bowl or the like”). Meanwhile, Nolan is shaking the rattle in his hand and starts looking at the bowl. At 02:22, the parent encourages the child to “put it [PAR] in the bowl,” while Nolan moves his hand with the rattle in it sideways to the right (02:23). The parent at this point moves the salad bowl along to the right (02:24), thereby maximizing the possibility that the rattle will fall into the bowl. This is another moment where the parent is observably implementing the professional's advice (“[…] that you hold under his hand”). At 02:25, the child releases the rattle in the bowl and directs his gaze at either the bowl or his hand (difficult to see), which is something the professional pointed out in the advice as being extra beneficial (see Extract 1). After the child releases the toy into the bowl, the parent offers positive assessments of what the child has done (02:25: jaaaa “yeaahhh,” 02:26: goed zo “good,” 02:28: clapping, and 02:29: goed gedaan hoor mannetje “well done [PAR] little man”). Thus, the parent implicitly claims access to the relevant knowledge to assess the conduct of their child and therefore enacts epistemic authority (see Heritage and Raymond, 2005). Although the assessment is primarily directed toward the child, it is also hearable post hoc to the professional (by means of the video). Thus, a right that traditionally belongs to the domain of the professional (assessment) is now implicitly taken over by the parent. Moreover, by verbalizing the assessment aloud on the video, the parent also allows for the professional's endorsement of their assessment of the child's movement, and thus their epistemic authority.

In the next feedback message (Extract 3), the professional follows up on the parent's compliance and their advice.

Extract 3 starts where the professional refers to the exact moment in the video where Nolan releases the toy into the bowl (bij de 2:26 “at the 2:26,” line 4. See 02:26 in Extract 2). Given that the video duration is over 10 min and includes several practice activities, it is notable that the professional points out specifically this moment. It implies that this is, still or again, a relevant activity to discuss. Again, the professional uses a time stamp to highlight this part of the video, which she positively assesses (super mooi “super nice,” line 4), thereby claiming epistemic authority. However, in doing so, she also indirectly affirms the parent's positive assessment of the video and thus the parent's epistemic authority. The informal “super” (line 4) arguably enhances the relationship between professional and parent (cf. also the smiley in line 14), thus helping to reduce asymmetry.

The construction without parent or child in the agent position makes it an evaluation of the activity as successful, thereby only indirectly assessing parent and child. The professional refers to the release as “targeted” (gericht, line 4), which was described earlier as the specific activity that could be practiced (see Extract 1). Thus, the professional implicitly indicates that the implementation of their advice was effective (i.e., “targeted release” is achieved), indirectly affirming their epistemic authority. Whereas in Extract 1, the professional displayed caution regarding their knowledge that this was the time for the next step in Nolan's treatment, and in Extract 3 they confirm that their advice was indeed appropriate for that moment: Nolan was ready for a next step because when the targeted release was provoked, he produced the desired conduct.

Following the assessment, an explanation is provided of how implementing the advice is beneficial for the child's rehabilitation: the bowl is not only helping Nolan to release the toy in a more targeted way but also helping him to hold it “somewhat more consciously” (iets bewuster, line 5), and thereby “holding it longer” (langer vasthouden, line 6). The professional here again claims epistemic authority by displaying relevant, specialist knowledge. Once more, caution wording is observable: the modal verb lijkt (“seems,” line 4) and adverb iets (“a little,” line 5). This downplays the professional's epistemic authority, indicating orientation to the parent's epistemic authority. “Seems” is not only a mitigator but also an orientation to the circumstance that the professional assesses the child based on the video only and also on only this one occasion. Due to the remoteness and the technology of video, the professional cannot optimally observe the child in all dimensions, while the parent has real-time access to the child's movements and can therefore also make assessments based on multiple occasions. This thus orients to a difference in their epistemic domains.

Holding the toy longer is treated by the professional as a new future course of action that can be practiced by the parent and child. Again, the advice is framed as building on the success of the child (and indirectly the parent) in achieving something (cf. Extract 1). A new advice is formulated (lines 7–10) which includes various advice mitigation strategies also observed in Extract 1, e.g., an indirect construction (line 8), providing several options (rammelaar of sambabal “rattle or samba ball,” line 8; ballon of zo “balloon or something,” line 9) and optionality expressed through of zo (“or so,” line 9). Notable is that the professional returns to the salad bowl advice by proposing to repeat the bowl exercise. The professional positively assesses the use of the object referring to it as “a great addition” (echt een prima toevoeging, line 14). Although they thereby claim epistemic authority, this is mitigated by the use of the hedge “I think” (Landgrebe, 2012). The professional follows up on the previous advice by suggesting “you may keep that one in :)” (die mag je erin houden :), line 14). Again, the conditional modal verb mag (“may”) is used, this time combined with a smiley (a specific affordance of the medium of text). Both contribute to reducing the imposition on the parent and mitigate the professional's deontic stance.

Our analysis of case 1 shows that professional advice and inherent authority are downplayed in terms of epistemic and deontic stance, orienting to the authority of the parent. In the subsequent video, the parent complied with the advice and claimed epistemic authority by assessing the child's conduct, which was followed by a message in which the professional positively evaluated the compliance and elaborated on the advice. In doing so, the professional validated the authority of the parent, but at the same time managed to affirm their authority. Moreover, the advice sequence shows how the professional and the parent make use of the website and its affordances to work collaboratively in the child's treatment. The professional describes in great detail what the child is doing in the video and what progress they are making in the treatment and advises the parent on how they can contribute to this. The parent by implementing the advice and filming this for the professional, creates yet another opportunity for the professional to describe, assess, and advise. Furthermore, the analysis shows how specific affordances of the technology are used, for example, the time stamp referring to a moment in the video to initiate advice.

We now turn to the second pattern of advice-giving, in which advice from the occupational therapist is not implemented by the parent. Of interest is mainly how the professional revisits the advice in the follow-up message, but first, we examine the message in which the advice is initiated and the subsequent video in which the advice is not implemented.

Extract 4 is taken from the treatment of Noor, a toddler who has been in treatment for about 6 months and is at this point of the treatment somewhat in-between practicing with one hand wearing a sock to constrain the other hand (CIMT) and practicing with two hands (BiT). The focus of the therapeutic activities is particularly on the left hand. The extract shows the first part of a feedback message written by the occupational therapist.

The message is built up according to the common structure of the feedback messages (see Table 2), starting with greetings (line 1), followed by a thank-you message and a somewhat general compliment toward the parent (line 2). What follows is an announcement of what was observed in the video (made explicit by the verb zie “see,” line 3) and a slightly positive evaluation of the observed conduct: hele kleine stapjes vooruit (“very small steps forward,” line 3). The contrast indicated by toch (“yet,” line 3) may be a response to the parent's message accompanying the video that says: “Things are the same with Noor” (data not shown), suggesting a lack of progress. Notable is that the professional makes considerable effort to demonstrate the basis for the epistemic authority on which their feedback is built. By listing what is observed in the video (lines 4–8) and what is thus evaluated as progress, she provides evidence for their assessment and for the upcoming recommendations (see also the colon at the end of line 3). Starting each observation with a horizontal dash and a time stamp, the professional gives very specific descriptions of the child's conduct on the video (cf. Extract 1). The use of specific text features such as these parentheses (but also smiley faces, horizontal dashes for an enumeration, etc.) is afforded by the technology used for the interaction.

The professional uses the time stamp “1:27” (line 6, shown in Figure 3) to initiate advice. In the video, Noor shows movements that the professional points to as something that can be practiced: releasing. The parentheses around “(by accident)” [(per toeval), line 6] mark some uncertainty and therefore mitigate epistemic authority. The advice entails that, in future, the parent should point out to Noor that she has released something properly. The professional's orientation to the delicacy of their advice can be seen through the conditional modal verb mag (“may,” line 6) that treats the projected action as an option, and the use of the abbreviation evt. (“possibly,” line 6) that likewise marks the optionality of the proposal (see Stevanovic and Peräkylä, 2012). As such, the professional mitigates the claim of deontic authority that their advice might entail and reduces the imposition on the parent.

To elaborate on the advice, the professional enacts the words the parent might use to implement the advice (lines 6–7). Instead of mentioning multiple options (cf. Extract 1), one specific option is described in the form of a hypothetical wording that the parent may apply. Again, the professional makes the advice concrete and eliminates a potential problem in implementation, namely that the parent would not know how to do that (see Simmons and LeCouteur, 2011). Moreover, the professional accounts for the advice by explicating that it may be implemented even if Noor accidentally releases the toy (line 7). This addresses the norm that one usually does not complement something that happens by accident but emphasizes that there are many opportunities to practice what is advised (i.e., the parent does not have to wait for the child to intentionally release the toy).

In the next video posted on the website, the parent observably misses an opportunity for advice implementation (Extract 5).5

The fragment starts at 03:54 where the parent hands over a circular toy to the sibling sitting next to Noor (the hand is visible at the bottom left of the frame). While the parent is doing this, at 03:54 Noor gazes at the toy and at 03:56 reaches for the circular toy with her right hand, moving her body forward. At 03:57, Noor releases the rattle that she was holding in her left hand and at 03:58 moves her body up. At this point, the professional's advice in Extract 4 becomes relevant: the parent can now compliment Noor for properly releasing the toy with her left hand. The next few seconds (03:59–04:02) show that the child's release of the rattle does not go unnoticed by the parent. At 03:59, the parent reaches forward to pick up the fallen rattle and Noor gazes at her parent. At 04:00, the parent moves backwards holding the rattle, while Noor follows the parent's hand holding the rattle with her gaze. Then, at 04:01, the parent says “uh oh,” orienting to the release as an accident rather than something that was successful. At 04:02, the parent goes through the bin of toys and initiates the start of a new activity with “what more do we have.”

The parent thus does not implement the professional's advice (“compliment releasing”) during this opportunity. The response of the professional (Extract 6) indirectly addresses the lack of compliance by reiterating the advice.

The “accidental release” (per ongeluk loslaten) is pointed out in line 8, followed by a time stamp at which this (approximately)6 occurred according to the professional and a positive evaluation (netjes “neat,” line 9). Through the assessments of the child's conduct, the professional claims epistemic authority, this time not mitigating their epistemic stance regarding what they see in the video (cf. Extract 4).

After the evaluative description of what is seen in the video, the professional re-issues their advice (“compliment releasing”). With the conditional verb mag (“may,” line 9), they mitigate the deontic power of their proposal but foreground the issue of choice less apparently than before: instead of evt. (“possibly”), the professional now uses the Dutch adverb wel (line 9), which means the opposite of “not,” emphasizing that the parent did not say this in the video, but should. With the advice not being implemented the first time, the professional does not suggest a particular phrasing, but she does provide the rationale behind the advice, which was absent the first time (cf. Extract 1). The professional emphasizes how implementing the advice might result in the child enjoying the activity more and help make more progress (lines 10–11), both things that stress the importance of the advice.

The analysis of case 2 shows how a professional addresses non-compliance with advice during TET. The video showed that the parent did not implement the advice, which the professional responded to in a subsequent message. By re-issuing the advice, presenting it as less optional and supporting it with an explanation of how this future action may facilitate the child's rehabilitation, the professional pursued advice implementation. The professional did not explicitly orient to non-compliance, having to repeat the advice, or even to a missed opportunity, but only indirectly addressed the lack of enacted compliance. Note that this is particularly notable because of the reprocessability on the website. It would have been convenient for the professional to refer to something she had mentioned in a previous message since the history of the interaction is available to both parents and professionals. By refraining from using this feature, the professional downplayed their role as someone who should assess the parent and their “work” and focus on the assessment of the child's movements and future opportunities for advice implementation.

Finally, in the third pattern of advice-giving in our data, the occupational therapist's advice is not implemented by the parent (on video), but the parent displays accountability for this in the accompanying message. Of particular interest is how the professional modifies the advice in the follow-up message, but first, we consider the message initiating the advice and the subsequent message from the parent accounting for not complying with the advice.

Extract 7 is taken from the treatment of Lynn, a toddler who just started treatment and is practicing with one hand wearing a sling to constrain the other hand (CIMT). This extract shows only the lines in which advice, and a rationale for the advice, are provided by the occupational therapist.

Again, the professional's orientation to the delicacy of their advice can be seen in their use of the conditional modal verb “could” (zou kunnen, line 6) and the particle nog (“further,” [PAR], line 6). The use of bekijken (“consider,” line 6) is also a mitigated phrasing of advice. Furthermore, the entire wording of the advice is a mitigated choice compared to, for example, “you could [PAR] put Lynn in a high chair at the table.”

When the professional elaborates on their advice in line 7 by providing a rationale behind it, caution is also evident: it would cause Lynn to sit “just [PAR] a bit” more stable (nog net wat, line 7) and “slightly” (iets, line 7) less forward. The use of the probability adjective “possibly” (mogelijk, line 8), when the professional explains how implementation of the advice might contribute to Lynn's rehabilitation, does similar interactional work (cf. Extract 1 and 6).

In the next message posted on the website accompanying a new video of Lynn, the parents display accountability for their non-compliance with the professional's advice, which is visible on the video (Extract 8).

By stating that they have tried implementing the professional's advice (to practice with their child in a high chair), the parents orient to and validate the professionals' deontic authority. However, the parents claim epistemic authority by assessing that this advice does not work for their daughter (“she hates this,” line 9). In TET, such experience is not equally available to all interactants. The parent's explanation (“our high chair is very narrow,” lines 9–10) further provides the professional with access to previously unknown information about Lynn's specific situation.

Instead of waiting for new advice from the professional in the subsequent message, the parents communicate that they “are going to try” (we gaan even proberen, line 13) a solution they came up with themselves (a different chair). Instead of engaging in such a task with the professional together, the parents self-initiate a different course of action and thus assert their deontic rights to determine the course of their child's treatment. By stating how this solution will resolve the problem (because it provides access to the table for Lynn, see lines 13–14), the parents claim access to the relevant knowledge about a good solution and their rights to display this knowledge.

The professional responds to the parents by considering their experiences and modifying the advice (Extract 9).

In their revision of the advice, the professional limits the options to implement the advice to three different alternatives. First, the alternative that comes closest to the initial advice is practicing in a high chair, yet a specific “Ikea outdoor/camping” chair [kinderstoel van Ikea (buiten/campingstoel), line 4]. Second, the alternative the parents proposed (kleinere witte stoeltje van de ikea “smaller white Ikea chair,” line 5), yet with the addition of “a footstool” (voetenbankje, line 6). Third, a new alternative: “The corner of the sofa” (hoek van de bank, line 10). Through mitigation (heel mss “just maybe,” line 5; zou denk ik wel kunnen “would be possible I think,” lines 6–7), the imposition put on the parents is reduced. Not attributing the actions of implementing the advice directly to the parents does similar interactional work.

The mitigation in the revision of the advice also displays an orientation toward, and validates, the parents' claim of epistemic authority. However, the addition of a footstool to the parents' solution also implicitly challenges that claim. By not treating the alternative that the parents proposed as a foolproof plan, the professional questions their authority and thereby reclaims some of their own epistemic authority. Moreover, the professional also inserts a warning to the parents' alternative (line 8), displaying their knowledge about the possible danger involved in this activity. Adding a third, new option, is also a marked action since the parents did not ask for alternative solutions. Finally, with the request in line 9, the professional also reclaims their epistemic authority: it invites the parents directly to share visual access to the child with the professional [although again the deontic force is downplayed by the use of “may” (mag, line 9)]. This allows the professional to assess the activity in future and also provides an opportunity to check whether the parents implement the modification of the advice.

The analysis of case 3 shows how some form of friction between the professional's authority and the parent's authority is managed by both parties in the interaction. Parents claim relevant epistemic knowledge about their child's situation (that is unavailable to the professional because of the setting of TET) and concurrent deontic authority regarding the course of their child's treatment (i.e., not complying with a particular advice). By giving an account, they not only provide access to the relevant knowledge but also allow the professional to validate their authority. The professional responds to the parents' display of authority by modifying their previous advice. In doing so, she affirms the parents' authority, while also displaying their own. On the one hand, she does this by evaluating the parents' alternative and adding something to it, and on the other hand, by proposing two other alternative solutions. In other words, the professional downplays their deontic stance, to reduce the imposition advice-giving puts on parents and the asymmetry it creates between the interactants. At the same time, they reinforce their epistemic stance by not accepting the parents' solution without adaptation and displaying their own solutions to the problem.

This study set out to describe advice-giving by occupational therapists in the setting of a pediatric TET, as well as the visible (non-)compliance to this advice, and the subsequent response. Although advice-giving is an essential part of paramedical professionals' work practices, it is also generally considered a precarious activity (Heritage and Sefi, 1992). We assumed that remoteness and technology would affect advice practices, particularly as the website allows for reprocessability and rehearsability of what has been or is said and done by interactants (both professionals and parents), and because of the modalities of text and video. We focused our analysis on authority, a key concept in advice-giving, which in itself implies a certain asymmetric relationship between the giver and the receiver. Our analyses show that professionals in TET accomplish their work together with the parents of the children in treatment. They do this by interactionally downgrading their authority and orienting toward parental authority. In terms of advice-giving, we found that professionals displayed great caution when providing electronically written advice to parents. By downplaying their deontic stance, they oriented toward advice involving an imposition on parents. Furthermore, by mitigating their epistemic stance, professionals are oriented toward parents' epistemic authority regarding their own child and their specific situation.

We observed different patterns of advice depending on whether written advice was visibly implemented or not in the videos posted on the website. Three patterns of advice-giving can be identified in the data. When advice was visibly implemented in the follow-up video, the professional slightly strengthened their epistemic stance regarding the possible outcome of the advice, although caution was still evident. This caution may be due to a constraint of the technology of video, upon which the professional relies for the assessment, not having full visual access to the child's movements. Although advice was followed by visible compliance from the parent in the vast majority of cases in our dataset, there were also cases where advice was not visibly implemented in the follow-up video. We observed that by reiterating the advice, the professional pursued compliance. Mere re-issuing of the advice was not observed when parents accounted for their non-compliance in a message and claimed deontic authority based on the knowledge of their child. The professional asserted the parents' authority by putting forward alternative, modified advice, thus respecting their objection to the initial advice.

Our analyses extend previous analyses of authority in social interaction (e.g., Heritage and Clayman, 2010; Heritage and Raymond, 2012; Stevanovic, 2015) and more specifically on advice-giving in interaction in healthcare (e.g., Heritage and Sefi, 1992; Heritage and Lindstrom, 1998; Pilnick, 2001, 2003) by considering how this works in a technology-mediated environment. Based on our analyses, we draw three conclusions regarding how technology and remoteness impact advice-giving in TET. First, we discuss how exploring advice-giving in TET reshapes our understanding of advice in this setting as a “merged” activity where advice implies instruction. Second, we describe how our analyses demonstrate how advice-giving in TET is altered in terms of authority and shifting domains of authority. Third, we show how TET produces “reciprocal accountability”—the accounting for the intensive work of parents incites professionals to respond with similar attentiveness and intensity. We elaborate on these findings in more detail below.

First, in terms of advice-giving, our findings have implications for our understanding of advice in general. Where previous studies showed how patients or their caretakers receive professionals' advice during the unfolding of the healthcare interaction (e.g., by displaying acceptance, resistance, or rejection), we have provided fresh data that illustrate parents' actual implementation of the advice observable to the professionals on a website. Our analysis of advice-giving in TET shows that the activity and the actions it accomplishes in this specific setting are different, which brings us to a new understanding of advice in the specific interactions under scrutiny. Advice-giving in TET appears to be a “merged” activity, combining the actions of advice and instructed action. In general, advice is a description of a preferred rather than a definitive course of action and is often formulated in a suggestive, tentative way (Pilnick, 1999, 2003). We see this reflected in the way professionals in TET design their turns. However, we have also seen that in addition to describing what a preferred course of action could be, professionals describe how this preferred course of action could be implemented (see, for example, Extract 1, lines 7–8). By telling parents what they could do and how they could do it, professionals seem to orient to ensuring that parents follow the advice, in addition to recommending the most appropriate course of action. This is even more relevant considering the specific goals and constraints of the interaction. Parents are not only expected but also encouraged to follow the procedures indicated by the professionals and to make these activities available (and thus assessable) through video. It, therefore, seems that parents' actions at home are in some sense assessed in terms of to what extent they match the professionals' proposed actions. This is evident when parents account for not (visibly) following advised actions on camera and when professionals re-issue advice when they do not observe compliance, which is more consistent with responses to instructed actions than with responses to advice implementation (cf. Mondada, 2011; Zemel and Koschmann, 2011).

However, the sequences are not designed as a directive “first” that projects one correct complying “second,” i.e., there is not merely one correct way to follow the advice. This distinguishes the sequences from typical instructions (cf. Pilnick, 1999, 2001, 2003, on medication dosage instructions, or Hedman, 2016, on emergency call instructions). As such, these may be instructions disguised as advice or advice that implies instructions (cf. “advice implicative actions,” Shaw et al., 2015). Advice-giving and implementing practices are constructed and made explicitly observable and reproducible through the videos and messages on the website. Although advice in TET does not always merely describe what a future course of action might be but can also include directions on how to implement an action, it is not as constraining as instructions and grants more authority to the advice-recipient. However, instead of acceptance or rejection, it sets up implementation of the advice on camera as a relevant next action. This may explain why parents treat advised actions as instructed actions by accounting for non-compliance, and why professionals re-issue the advice if there is no compliance or accounting by the parent. The “merging” of advice-giving/instructing is thus arguably related to the technology used for TET.

Second, our findings provide empirical evidence on the role of epistemic and deontic authorities in technology-mediated interaction. Our analyses reveal that domains of authority shift during TET. Knowledge that is typically part of the professional's epistemic domain shifts toward the parental domain, which is, for example, visible when parents assess their child during exercises in the videos. The setting of TET provides the parent with a certain amount of (on-site) expertise: they are the ones who instruct the child and practice with them in their home environment. During the treatment, they therefore become an expert in providing treatment to this specific child. The professional and parent hence become joint experts in the child's treatment: the professional is based on professional training and experience (e.g., Abbott, 1993). The parent based on personal experience with their child.

In reaction to this, professionals not only demonstrate their epistemic authority through very detailed descriptions of the movements they observe in the videos but they also give parents access to this epistemic knowledge. Parents in turn display their epistemic authority by making assessments of the child's conduct and providing the professionals with information specific to their child. Based on this, they also exercise authority on deontic grounds by not implementing advice and proposing alternative solutions. This is consistent with previous findings that patients (or their caregivers) resist advice that may not fit their situation or preferences (e.g., Heritage and Sefi, 1992; Pilnick and Coleman, 2003; Stivers, 2005; Stivers and Timmermans, 2020; Caronia and Ranzani, 2023). While some research suggests that a shift of authority toward patients or their parents can be problematic (cf. Stivers and Timmermans, 2020), our analyses show that professionals in the TET we studied are well able to adjust to this. Professionals orient to mutual expertise by displaying both their epistemic and deontic authority in a mitigated form, but also by validating parental authority through endorsing their assessments and proposals.

Finally, our analyses show that parents' accounting for intensive work incites professionals to respond with similar attentiveness and intensity. The pattern in which advice was followed by visible compliance on video was the most common sequential unfolding of advice in our dataset. Again, this may be due to the specific affordances of the technology used: for example, parents have the option not to upload videos in which they do not implement advice meaning that the technology allows them to rehearse before uploading. This, however, is also likely related to the fact that most professional advice proposes so-called “low-cost actions” that support the child's rehabilitation. Nonetheless, our data reveal that parents need to display that they are doing the work expected of them, for example, by giving an account based on their knowledge about their own situation for not following advice, but actually also in the first place by uploading videos showing compliance with the advice and providing evidence for practicing. The technology thus not only allows for the reprocessability of earlier actions (e.g., Baralou and Tsoukas, 2015) but also becomes a performative form of accountability. The overview on the website of parents' earlier actions, i.e., the reprocessability, reveals how all previous “low-cost” actions build up to a high cost.

While the advice may focus on “low-cost actions,” perseverance with the treatment demands a great deal from parents, especially as the videos provide a way for professionals to “check” what parents do and how they do this. This requires parents to feel encouraged and well-treated. Professionals therefore respond in their feedback messages to the intensity of the work for parents and, in the way they write their advice, orient to the work placed on parents' shoulders. At the same time, professionals show their reciprocal accountability by putting a lot of effort into their feedback, not only by cautiously phrasing advice but also by describing in detail what they observe in the videos, giving compliments, and encouraging parents. The way they give advice should thus also be seen as displaying accountability for the time and effort they put in the treatment, which they can only make visible to parents in this way. Again, this mechanism of reciprocal account-giving of actions—for both the parents and the professionals—is enabled and reproduced by the use of digital technology to provide remote treatment.

Our study reveals how TET requires at least additional and different work from professionals. The cautiousness and optionality conveyed in occupational therapists' advice, and also, the detailed descriptions of what they see in the videos, the compliments they provide, and the informal language used, show that professionals perform a great deal of “relational work” (Locher and Watts, 2005) to preserve the relationship and avoid resistance from parents in the course of the treatment. It reveals a delicate balance between two goals of professionals in TET that are crucial for the child's rehabilitation: on the one hand, reducing imposition, to ensure that parents remain motivated to continue the treatment with their child, and, on the other hand, ensuring that parents implement activities correctly and thus follow the advice.

For coaching practices, professionals rely on writing. This means obtaining certain skills that might otherwise play no (major) role in this profession, such as writing skills, converting what is seen on video to text, and finding ways to refer to moving images by means of writing. Our analysis thus calls for reflection on what digitalization means for the work of professionals and what this implies for professional training. One implication is, for example, that professionals must have and be given time to master these specific skills to engage in TET. Another implication is that, given the increase in digitalized treatments, attention to these skills should be included in professionals' education programs.

The recursive character of displaying hard work, particularly from professionals, raises the question of whether this remains manageable in practice. In the setting of our study, working with the secured website for TET was still on a small scale. How such use of digital technology for TET further alters the work of professionals, particularly when this becomes a common practice in many more treatments, calls for future research. Moreover, a limitation to the conclusions presented here is that we have focused mainly on the side of professionals. Therefore, future research is needed to investigate how parents manage their participation in TET and how they cope with possible overintensity as a result of the work required of them.

We can conclude that occupational therapists providing TET to young children with CP orient to authority in their electronically written advice to parents and work hard to present a downgraded authoritative stance that is weaker than their institutional status would implicate, thereby establishing and maintaining collaboration with parents to serve the child's recovery. Our conversation analytical study of naturally occurring digitalized interactions provides insights into how professionals carefully initiate and return to advice, and how they thus work together with parents from message to message in TET. This offers a better understanding of how paramedical professionals conduct their profession given remoteness and technology and how remoteness and technology affect advice-giving.

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because of confidentiality. Requests to access the datasets should be directed at: ZXZpLmRhbG1haWplckBydS5ubA==.