- 1BE4LIFE, Department of Marketing, Innovation and Organization, Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium

- 2Research Group Cultural History Since 1750, Catholic University of Leuven, Leuven, Belgium

Introduction: The landscape of food writings has undergone a significant transformation, shifting from traditional informational cookbooks to hybrid edutaining cookbooks authored by celebrity chefs and influencers. To gain a better understanding of this evolution, we conducted a discourse analysis to examine the proclamations made by cookbooks authored by celebrity chefs and influencers and their alignment with our society.

Methods: We conducted a critical discourse analysis on 18 best-selling cookbooks published in Flanders (Belgium) between 2008 and 2018. Applying Fairclough's three-dimensional framework, we conducted text, process, and social analyses to delve into the content and context of the cookbooks.

Results: Our analysis reveals that modern cookbooks not only provide information but also aim to inspire and entertain readers. They adopt a personal discourse that emphasizes shared values and authenticity. Celebrity chefs focus on traditional aspects, such as family, tradition, and the joy of cooking, while influencers offer lifestyle advice centered on postmodern values, including moral choice, achievement, fulfillment, and personal responsibility. Additionally, influencers take an anti-establishment stance by criticizing “conventional science” and processed food, reflecting the growing societal distrust toward food science and the food industry.

Discussion: The shift from traditional informational cookbooks to hybrid edutaining cookbooks authored by media icons such as celebrity chefs and influencers is apparent based on our analysis. These contemporary cookbooks not only provide recipes but also serve as outlets for inspiration and entertainment. Furthermore, the discourse found in modern cookbooks reflects the prevailing societal trends of our postmodern and individualistic era.

1. Introduction

Food has always held great societal significance, and people have been writing about it for centuries (Homan, 2007). While classic food writings and cookbooks typically offer guidance on cooking, preserving, and serving food, Notaker (2017) notes they also provide insight into local traditions and social evolutions (Homan, 2007; Notaker, 2017). In line with this, several Western countries have their own classic cookbook that reflects their longstanding culinary traditions. In Flanders (Belgium), for instance, “ons kookboek” stands as the most renowned classic cookbook (Segers, 2005). The book was first published in 1927 and received 15 editions over the course of a century. Examples of classic cookbooks from other countries include the Danish cookbook “Mad” and the Dutch cookbook “Margriet Kookboek” (Segers, 2005; Eidner et al., 2013; Buisman and Jonkman, 2019). “Mad” and “Margriet Kookboek” were first published in 1909 and 1945, respectively, and continue to captivate local audiences to this day (Segers, 2005; Eidner et al., 2013; Buisman and Jonkman, 2019). Changes in recipes across new editions of both cookbooks for instance, are intertwined with shifts in the dietary habits of both the Dutch and Danish populations (Eidner et al., 2013; Buisman and Jonkman, 2019). As such, aside from providing insight into social evolutions, classic cookbooks may also have the potential to shape and influence them (Notaker, 2017). For example before the release of “ons kookboek” the traditional Flemish diet was rather monotonous (Segers, 2005). Main dishes predominantly revolved around potatoes, bread, bacon, and butter. Vegetables and meat only played a minor role. In “ons kookboek,” the authors advocated for a three meals a day system and an increased usage of home-produced vegetables and animal products (Segers, 2005). To this day, the three meals a day system, along with a main course featuring potatoes, vegetables, fish, or meat, remain the cornerstones of Flemish cuisine. Considering the societal role these classic cookbooks had, important questions are whether and what social implications current cookbooks have, and how their content has evolved over the years.

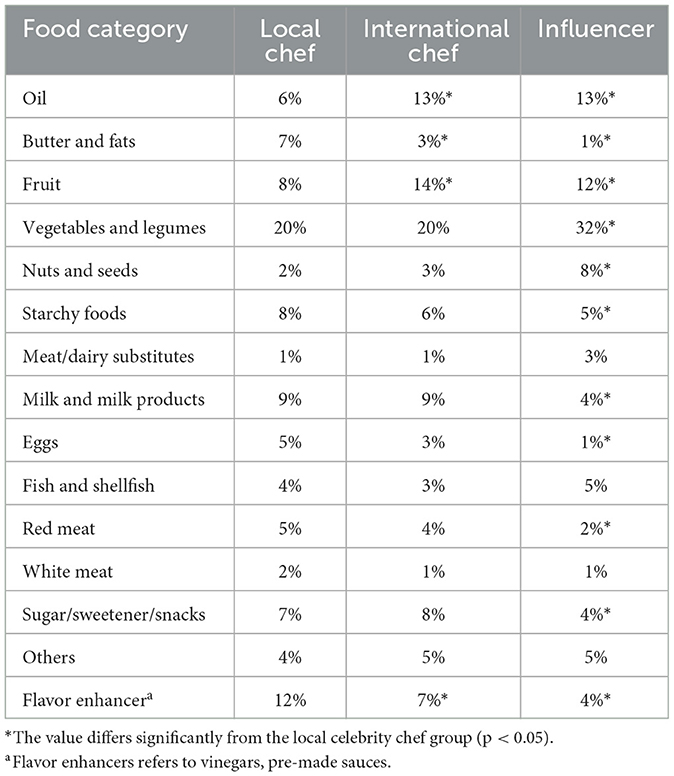

These questions are relevant as cookbooks still matter today. Indeed, despite the increasing amount of media channels offering food information, cookbooks continue to enjoy enduring popularity in contemporary times. In the United States, for example, cookbook sales keep increasing (NPD Group, 2018, 2020). Similarly, in Flanders (Belgium) with an adult population of approximately 5 million people, over 600,000 cookbooks were sold annually over the period 2009–2018 (Figure 1) (Boek.be, 2019; Statistiek Vlaanderen, 2022).

Figure 1. Annual cookbook sales in Flanders over the period 2008-2019 (Boek.be, 2019).

This enduring popularity of cookbooks may appear counterintuitive in an era where thousands of recipes are readily accessible online (Elias, 2017). However, it is plausible though that the rise of other media channels has actually contributed to the appeal of cookbooks (Notaker, 2017). For instance, cookbooks can serve as a medium through which popular food media icons can recontextualize their work and connect with a wider audience. This theory aligns with the observed sales decline of traditional cookbooks, which have an informational purpose without a central focus on a specific persona. In Flanders, for example, traditional cookbook sales have dropped from over 200,000 in 2008 to < 50,000 in 2018 (Boek.be, 2019). Similar trends are reported in Slovenia and the United States (Tominc, 2014b; Swanson, 2015, 2017, 2018; Segura, 2016). In contrast, cookbooks centered around popular media icons such as celebrity chefs and lifestyle gurus have been dominating cookbook charts in Flanders and the United States since the 2010s (Tominc, 2014b; Swanson, 2015, 2017, 2018; Segura, 2016; Boek.be, 2019).

Celebrity chefs, which we define as professional cooks who have attained a celebrity status through their appearances on media platforms, quickly gained popularity in the 1990s and 2000s, coinciding with an overall boom in cooking television (Giousmpasoglou et al., 2020). Before the 1990s, cooking shows did not enjoy high viewing figures and the profession of being a chef was relatively marginalized in society (Giousmpasoglou et al., 2020). In the 1990s, new food television shows that revolved around celebrity chefs emerged, and these shows quickly gained widespread popularity (Zopiatis and Melanthiou, 2019; Giousmpasoglou et al., 2020). International chefs like Jamie Oliver and Gordon Ramsay gained fame across multiple Western countries (Tominc, 2014b). Simultaneously, most Western countries got their own local celebrity chefs. These local celebrity chefs drew inspiration from their international counterparts and adapted it to local cultures and expectations (Tominc, 2014b; Zopiatis and Melanthiou, 2019). Soon celebrity chefs started to recontextualize their work to other media channels like cookbooks and later on social media, gaining even more fame (Henderson, 2011; Clarke et al., 2016). In literature this widespread popularity of celebrity chefs is referred to as “the celebrity chef phenomenon,” and until this day it shows no sign of disappearing (Zopiatis and Melanthiou, 2019; Giousmpasoglou et al., 2020). In fact, a recent study shows that 33% of Flemish people rely on celebrity chefs as their primary source of food information, making them the most popular food information source among the population (Proesmans et al., 2022).

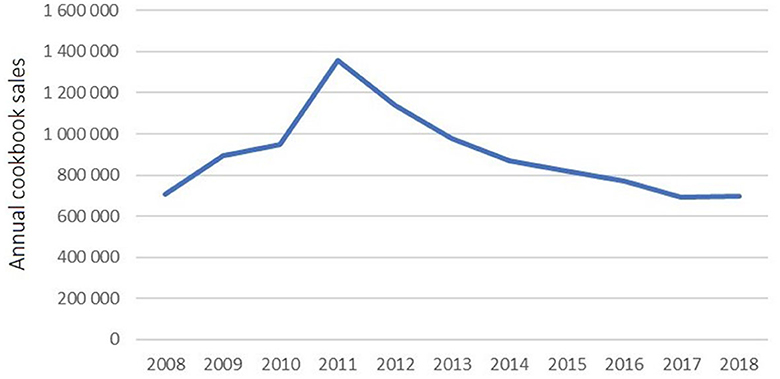

Celebrity chefs aside, influencers or lifestyle gurus defined as “unlicensed native agents of awareness, positioned in conventional and social media, to offer emotional support, an identity matrix and pedagogy for self-discovery and well-being.”(Baker and Rojek, 2020, p.13) also gained prominence in the 2010s. Influencers first obtained popularity with slimming diets after the 1960s (Mitchell, 2008; Anderson, 2023). The influencers Montignac and Atkins, for example, sold over a million books promoting a controversial diet for weight loss (Bradfield, 1973; Martin, 2003; Hevesi, 2010). However, especially the rise of social media in the 2010s fueled influencers' popularity (Baker and Rojek, 2020). With little regulations and widespread popularity, online media allows everyone to spread food-related content and to make almost any dietary claim without proper substantiation via blogs or social media (Baker and Rojek, 2020). In contrast to normal celebrities or food scientists, these influencers can interact directly with their audience on social media creating strong parasocial relationships (Baker and Rojek, 2020). Previous studies even found that these parasocial relations and a high sense of authenticity make influencers more successful than celebrities in promoting products (Schouten et al., 2019; Baker and Rojek, 2020). In Flanders, 12% of people refer to influencers as their main source of food information, making them the most popular source of food information after celebrity chefs and family and friends (Proesmans et al., 2022). Of all food information sources mentioned in the study, people who obtained information from influencers showed the strongest association with changes in dietary intake and dietary restrictions. Since 2015, influencers have been dominating the cookbook charts in Flanders (Figure 2). A similar phenomenon seems to occur in other countries. In the United States, for example, influencers dominated the book charts in 2014, while Joanna Gaines' “Magnolia table” was the best-selling cookbook in 2018 (Swanson, 2015; NPD Group, 2018). Joanna Gaines is not a certified chef, but she did obtain fame via reality TV and social media resulting in a substantial number of loyal followers and a true influencer status.

Figure 2. Prominence of each type of author in the top 20 best-selling cookbooks of Flanders. Data obtained from Boek.be (2019).

The social implications of this increased popularity of celebrity chefs and influencers are unclear though. A discourse study of Tominc (2012) found Slovenian celebrity chef cookbooks increasingly adopt an edutaining genre, which could help in generating the idea of cooking as a recreational activity (Daniels et al., 2012; Tominc, 2012). Other studies hypothesize celebrity chefs may have stimulated men to cook more often at home in a period where home cooking was in decline (Daniels et al., 2012; De Backer and Hudders, 2016). In line with this hypothesis, previous discourse studies found male celebrity chef cookbooks attempt to recontextualize cooking as a masculine practice trying to recontextualize cooking as a masculine practice (Eriksson and Andersson, 2016; Anderson, 2023). In contrast, Anderson (2023) points out these books still reproduce traditional gender norms and a gendered division in labor though. In the case of female celebrity chefs, past discourse analyses show how cookbooks still promote the traditional idea of women who have to cook at home, while also offering a discourse of achievability, self-fulfillment, and femininity (Matwick, 2017). Similarly, influencers also rely on a discourse of achievability and self-fulfillment to promote their content (Baker and Rojek, 2020). Some authors criticize influencers for offering oversimplified food advice and promoting unhealthy dietary behavior (Byrne et al., 2017; Lavorgna and Di Ronco, 2019), while other studies indicate influencers can also promote healthy dietary practices (Korthals, 2017). To gain more insight into the proclamations of popular cookbook content and their relation to society, this study aims to provide an in-depth analysis of the evolution in the discourse of popular cookbooks published between 2008 and 2019. Our analysis seeks to examine the changes in cookbook content, its alignment with current social norms, and its potential contribution to social change. A better understanding of these matters is necessary as it would provide insights into the following three intertwined key points: (1) the discourse employed by chefs and influencers to amass significant followings, (2) the perspectives they advocate for regarding diet, cooking behavior, and lifestyle, and (3) the extent to which evolutions in discourse of cookbooks correspond with social trends and may even contribute to social change. By understanding the evolving discourse in cookbook content, valuable insights can be gained into the role of chefs and influencers in shaping culinary preferences and lifestyle choices, as well as in effectively communicating with the general public.

2. Methods and materials

2.1. Discourse analysis

To gain a deeper understanding of the discourse employed in contemporary cookbooks, a discourse analysis was conducted using Fairclough's three-dimensional framework (Fairclough, 2001). This framework was selected due to its systematic and practical approach in examining the intricate relationship between language and social change (Beyen, 2019). The framework has proven to be useful in multiple scientific disciplines such as marketing, sociology and history (Kaur et al., 2013; Beyen, 2019; Rashid, 2020). In addition, it has also been used to study the construction of gender roles in the cookbooks authored by female celebrity chefs (Matwick, 2016).

According to Fairclough, language and discourse are forms of social practice (Fairclough, 2001). Therefore, an analysis should pay attention to (1) the text (i.e. the description); (2) the processes of interpretation and production (i.e., the discursive practice); and (3) the social conditions in which the discourse occurs (i.e., social practice).

The first stage of the framework is “description” and it comprises a textual analysis (Janks, 1997; Beyen, 2019). During this stage, we analyze the vocabulary, semantics and linguistic features used in the text. As discourse analyses are sometimes criticized for being too subjective because of their qualitative approach, we integrate elements of corpus linguistics to improve the reliability (Orpin, 2005). This implies substantiating the findings with word frequencies and concordances using Wordsmith 7, as well as analyzing the ingredients used in the described dishes. This approach allows us to identify regularities and tendencies in the used language. Furthermore, applying word frequencies on both the text and the ingredient lists can give an indication on whether the discourse used in the text is in line with the ingredients used in the recipes. For example, if the discourse of the authors focusses on traditional Flemish recipes, one would expect a frequent usage of vegetables and meat in the recipes (Segers, 2005). In contrast, if authors focus on natural unprocessed diets, their recipes probably comprise more plant-based food groups. All ingredients were coded into different food groups based on the food scheme developed by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) (Montville et al., 2013).

The second stage, “interpretation” comprises a process analysis (Janks, 1997). This stage examines the production and interpretation of text, paying particular attention to the context in which the text is created, disseminated, and consumed. It is important to recognize that texts do not convey meaning in isolation; rather, they are part of a dynamic interaction involving the author, the disseminator, and the intended reader (Beyen, 2019). Within this process analysis, the focus is on how celebrity chefs and influencers promote their content and how they communicate. Likewise, authors can use references to other texts to reinforce their message. All aspects contribute to the discourse (Beyen, 2019).

The third stage “explanation” comprises a social analysis (Janks, 1997). While this dimension may not be directly embedded within the discourse itself, understanding the social context in which the discourse unfolds is crucial for comprehending its meaning and social implications (Janks, 1997; Beyen, 2019). Central in this stage is the dialectical relation between the discourse and social practice (Fairclough, 2001).

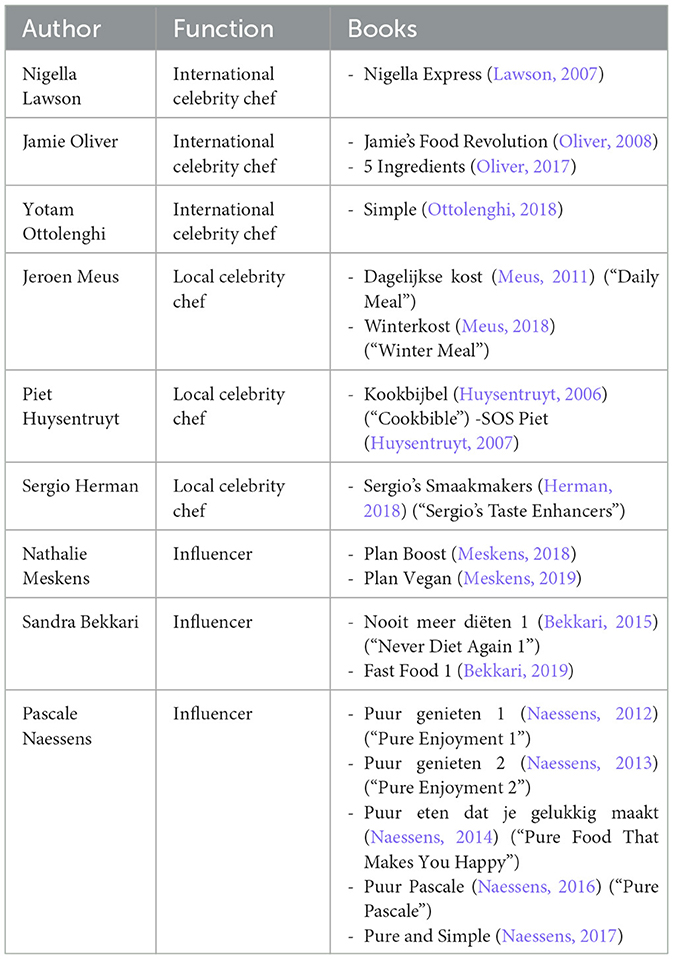

2.2. Corpus

Table 1 shows the 18 cookbooks selected for the discourse analysis. These cookbooks were chosen because they ranked among the top twenty of the year bestselling cookbooks in Flanders between 2008 and 2019. Notably, these 18 cookbooks were authored by only nine different individuals. This is because the top five bestselling cookbooks each year during the period of 2008–2019 were written by just ten different authors. Therefore, our analysis primarily focused on the content of these authors.

Looking at the best-selling authors, a distinction can be made between international celebrity chefs, local celebrity chefs and influencers. Three authors of each category were included. In total, nine books of influencers, five from local celebrity chefs and four from international celebrity chefs were used for analysis. All books were analyzed In the original language of publication.

3. Results

3.1. Description: textual analysis

During the first phase, known as the “description” phase, we conducted an analysis of the texts present in the cookbooks, focusing on the content alongside the ingredient lists. This analysis involved examining the frequently used words and conducting a content analysis specifically on the ingredient lists.

3.1.1. Pronouns

The cookbooks of both influencers and celebrity chefs frequently use the first and second person pronouns “I” and “you” and the possessive pronoun “my” (Appendices 1, 2). This usage of pronouns allows the authors to address readers collectively as individuals, creating a sense of personalization known as “synthetic personalization”(Patrona, 2015). This approach contributes to a conversation-like discourse, fostering a more direct relationship between the author and the reader As a result, the author appears more authentic and genuine (Kaur et al., 2013; Tominc, 2014a). For instance:

• “I want to cook healthy and tasty, but I do not have the time. Ooh I hear that remark often” (Sandra Bekkari's Fast Food; influencer, p. 9).

• “Even my children enjoy it more than McDonald's” (Sergio Herman's Sergio's Taste Enhancers; local chef, p. 220).

In both examples, the authors talk about shared experiences by discussing topics such as finding time to cook or making meals that their children enjoy. By using pronouns like “I” and “my,” they create an authentic and conversational discourse, fostering a sense of connection with the readers.

3.1.2. Adjectives

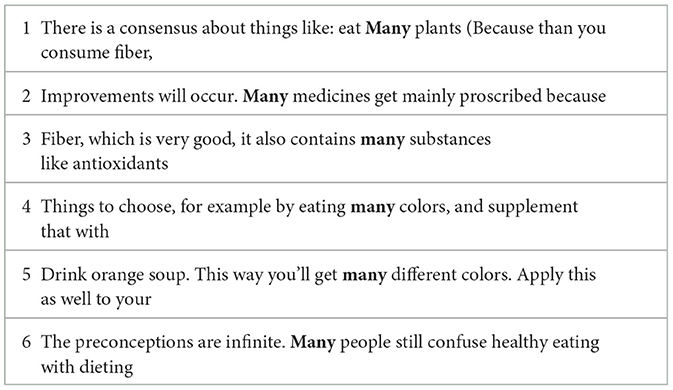

Influencers frequently use the words “many,” “more,” and “very” which are encapsulated by the word “veel” in Dutch (Appendix 1). These adjectives contribute to a discourse of fulfillment instead of a discourse of dieting and restriction. It can be used to enhance certain claims or accentuate certain beneficial aspects of a food product (Table 2).

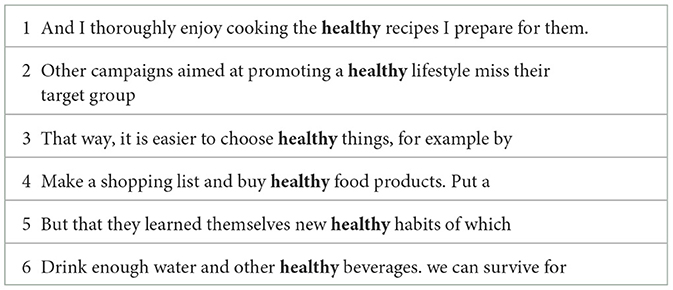

Other frequently used adjectives include “natural” and “healthy.” The term “natural” is generally used to promote a diet consisting of unprocessed food, which is proclaimed to be healthier (Table 3). The emphasis on naturalness may stem from concerns about the food chain and is reported as an outgrowth of the natural food movements in the 1970s (Elias, 2017). Similarly, the word healthy is used to promote specific food and lifestyle choices and reduce food anxiety (Table 4).

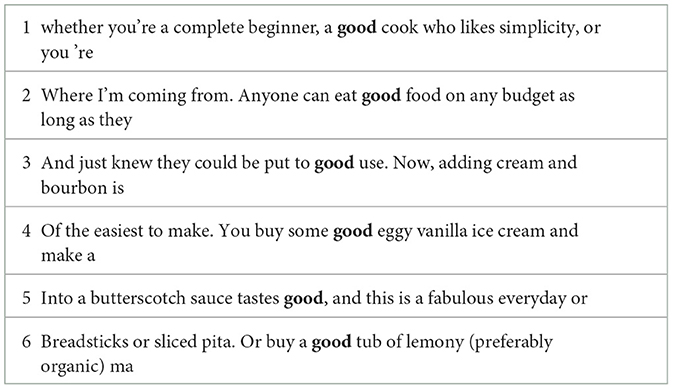

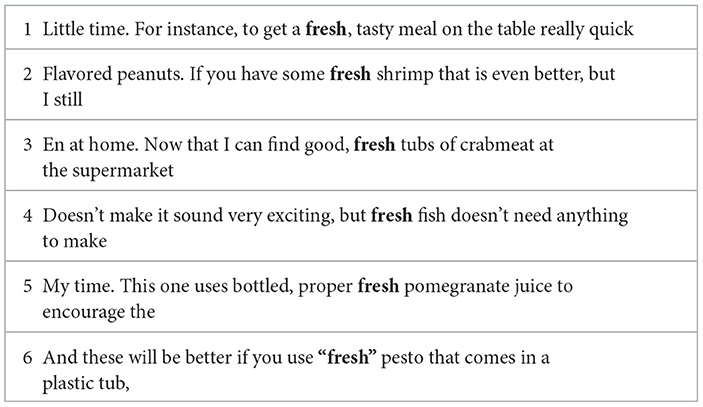

In celebrity chef cookbooks, adjectives such as “good,” “great,” and “fresh” are commonly employed to describe the quality of dishes and ingredients (Tables 5, 6). The focus here is on the cooking itself as fresh refers to the ingredients and good relates to the taste and quality of the dishes and the ingredients.

3.1.3. Vocabulary and verbs

When analyzing the vocabulary used in cookbooks, a noticeable distinction can be observed between celebrity chef and influencer cookbooks (Appendices 1, 2). Celebrity chefs tend to place a primary focus on the food itself, as evidenced by the frequent occurrence of words such as “eat,” “food,” and “cooking” in their texts (Appendix 1). Consistent with the findings of Elias (2017), the celebrity chefs in our study emphasize specific ingredients such as “anchovy,” “chicken,” and “garlic.” However, it is important to note that the choice of exact ingredients may vary from book to book and author to author. On the other hand, influencers demonstrate a discourse centered around food and health, frequently employing words such as “eat,” “healthy,” “health,” “body,” “good,” and “vegetables.” They further reinforce this discourse by incorporating technical terms like “phytochemicals,” “endorphins,” and “capsaicin.” Furthermore, influencers often provide oversimplified explanations of scientific concepts, such as the glycemic index or type 2 diabetes, and offer simplistic solutions on how to prevent or address issues regarding these concepts. These aspects all contribute to a “guru effect.” The guru effect suggests that individuals tend to perceive obscure opinions or information as a sign of intelligence, particularly when the guru figure appears to possess a deep understanding of complex concepts that others may have struggled to comprehend (Sperber, 2010). For instance:

• “Pure, natural ingredients promote a healthier, stronger, and more beautiful body.” (Pascale Naessens's Pure Pascale; influencer, p. 54).

• “Empty calories refers to calories that contain few vitamins, minerals, flavonoids and thousands of other types of phytochemicals or nutrients” (Nathalie Meskens' Plan boost, guru, p.11).

Many readers may not be familiar with terms such as phytochemicals or flavonoids and their impact on health. However, the authors presents themselves as an experts and emphasize the importance of these nutrients, creating an impression of expertise and implying their necessity.

3.1.4. Grammar

Among the cookbooks authored by influencers, there are several introductory chapters dedicated to persuading readers about healthfulness of a particular diet. In these chapters, influencers describe their theories about healthy food using declarative sentence structures. They outline the steps individuals should follow to adhere to the diet, employing conditional imperatives or declarative sentences. This approach enhances the creation of a synthesized personality (Patrona, 2015), portraying their statements as factual rather than mere ideas. The use of conditional structures also helps to distance the concept from the notion of restriction. For instance:

• “Baobab is a natural source of fiber, vitamin C, magnesium and calcium” (Nathalie Meskens's Plan Vegan; influencer, p. 28).

• “Start your day with a big glass of water and drink water throughout the day” (Sandra Bekkari's Never Diet Again 1; influencer, p. 27).

In the examples, little explanation is given regarding the specific quantity of minerals present in baobab or the reasons behind their potential benefits. Similarly, no justification is provided for the importance of starting the day with a large glass of water. However, due to the imperative structure employed in these statements, they are presented as factual without requiring further elaboration.

3.1.5. The recipes

In addition to variations in textual content, there are differences in the recipes themselves among different types of cookbook authors. Firstly, there is a discrepancy in the reported preparation time. Influencers provide clear indications of the time required to prepare a meal, often distinguishing between cooking time and preparation time. Among celebrity chefs, only cookbooks published after 2009 include information about the preparation time. Additionally, influencer recipes typically take around 33 min on average to prepare, whereas recipes from celebrity chefs tend to take approximately 63 min. Second, there is a difference in the amount of ingredients used. Notably, local and international celebrity chefs, on average, use ten ingredients per recipe, while influencers use only six. These findings are in line with the discourse of influencers concerning quick and easy recipes. The longer preparation time and ingredient list of celebrity chefs' recipes may indicate their recipes are more complex and less suitable for daily use. In line with these findings, Elias (2017) also report celebrity chefs' recipes are complex and therefore not ideal for home cooking.

Another explanation for why the recipes of influencers, as opposed to celebrity chefs, in this study have a shorter preparation time and use fewer ingredients could be that they are more recently published than the books of celebrity chefs. As many people struggle with finding the time to cook, the duration and simplicity of recipes may have become increasingly important over the years (Daniels et al., 2012; Taillie, 2018). One example of a more recent celebrity chef cookbook is Jamie Oliver's “5 Ingredients” (2017), which aims to provide recipes that are simple, use few ingredients, and can be prepared within 30 min. Unfortunately, based on the current selection of cookbooks, we cannot separate the impact of the type of author (celebrity chef vs. influencer) from the impact of the time period.

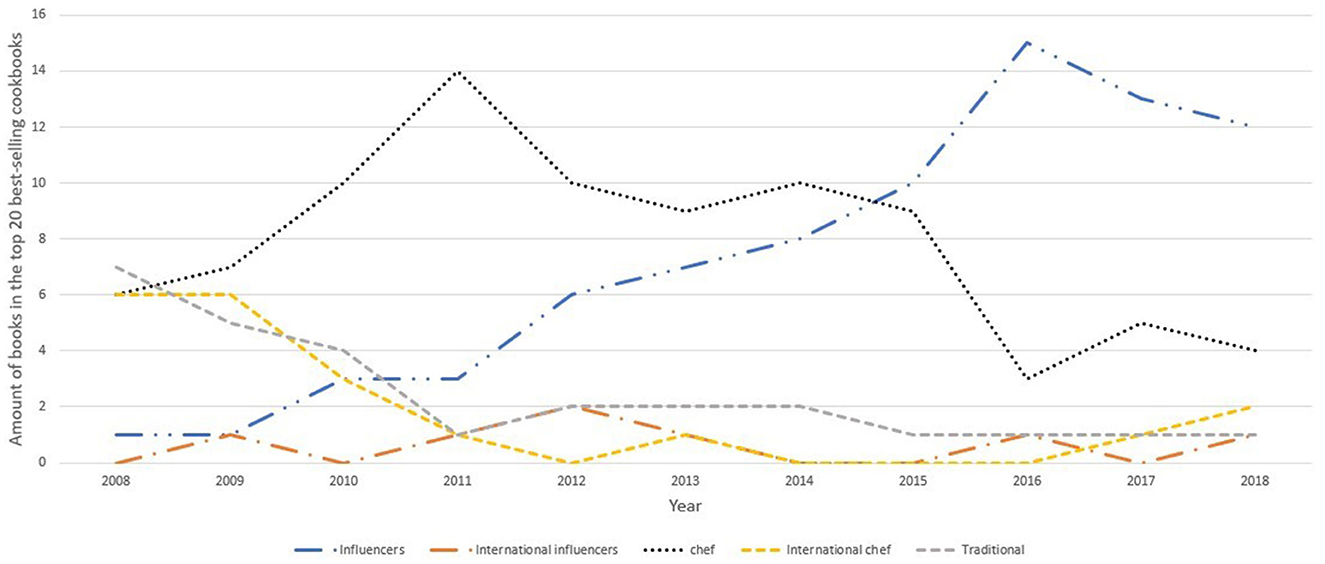

To further analyze the difference in content, Table 7 shows the ratio in which each food group occurs throughout the ingredient lists. Percentages are compared using a chi-square test with post-hoc comparison.

Table 7 reveals that influencers use oils, vegetables and legumes, and nuts and seeds (p < 0.05) more frequently, while using butter and fats, starchy foods, milk and milk products, eggs, flavor enhancers, sugar and sweeteners, and red meat less frequently (p < 0.05) compared to local celebrity chefs. This indicates that influencers tend to incorporate more plant-based ingredients in their recipes, aligning with their discourse on “natural” and “pure” ingredients. This aligns with the nutritional guidelines in 2020 that also encourage a greater emphasis on plant-based diets, further reinforcing the health discourse of the influencers (Gezond leven, 2019). Moreover, these differences are consistent with the observed differences in dietary intake between followers of influencers and followers of celebrity chefs in Flanders (Proesmans et al., 2022). Furthermore, it is observed that the difference in ingredient choices between local and international celebrity chefs is minimal. Local chefs tend to use butter and flavor enhancers more frequently, while using oil and fruit less frequently in their recipes. This finding suggests that local celebrity chefs may be influenced by their international counterparts, adapting their ingredient choices to align with global culinary trends.

3.2. Interpretation: discursive practice

In the second phase, “interpretation,” we conduct a process analysis. Here, a closer look is given to the discursive practice. The focus here is on the linguistic strategies authors use to persuade their audience and the context around the production and interpretation of the text.

3.2.1. Discourse of celebrity chefs

3.2.1.1. Content

All the analyzed celebrity chef cookbooks exhibit have a similar structure, with the exception of “Daily meal.” They typically start with a preface, followed by a collection of recipes. Among the international celebrity chefs and the cookbooks published after 2008, this collection of recipes comprises a story on each dish followed by instructions on how to prepare it. These stories serve to establish a connection with the readers and move the content to a more edutaining genre.

3.2.1.2. Recontextualization

A first observation among both local and international celebrity chefs is that their books serve as a recontextualization of their respective television shows. In the case of local celebrity chefs, they even name their books after their television show and prominently mention the broadcasting channel on the cover. In the cookbooks of local celebrity chefs published between 2008 and 2009, the recontextualization is particularly evident, as the prefaces discuss the origins of the TV show and the anecdotes shared in relation to the ingredients are derived from the television program. This approach not only promotes the television show, it also legitimizes their discourse as an impersonal authority (Van Leeuwen, 2007). For instance:

• “Three years of SOS Piet on television.” (Piet Huysentruyt's SOS Piet; local chef, p. 3).

• “More than a thousand recipes, years of practice bundled in one book. Who could have imagined this when I started the “Lekker Thuis” show in 1997.” (Piet Huysentruyt's Cookbible; local chef, p. 7).

In both examples, the authors highlight their previous successes, creating a sense of authority and expertise. These references in the preface not only establish their credibility but also serve as a promotional tool for their content across different media channels. It showcases their presence in the culinary world beyond the cookbook itself and adds to their overall image as reputable figures in the industry.

3.2.1.3. Discourse of relatability

As time progressed, cookbooks have evolved into a more hybrid genre, incorporating both stories and a broader focus on shared values (Tominc, 2014b). One example is the increasing emphasis on family. Cookbooks authored by local celebrity chefs published in 2008 or 2009 only briefly mention cooking for family. Among international celebrity chef and more recent local celebrity chef cookbooks, the concept of cooking for family gains more prominence. Meus (2018), for example, starts with a discourse of nostalgia, linking good childhood memories of being together with food. International celebrity chefs mention cooking for family multiple times when talking about their dishes and display pictures of them being with friends and family as well in their book. For instance:

• “On the weekend, I woke up to the scent of French toast, bacon, and coffee. We, me and my two brothers with whom I fought regularly, but that is a long time ago, would sit close to each other on the couch and read the stories of our childhood heroes.” (Jeroen Meus's Winter Meal; local chef, p. 4).

• “Having friends and family over is as much about hanging out together as the food that you eat.” (Yotam Ottolenghi's Simple; international chef, p. 13).

The first example creates a sense of nostalgia, evoking pleasant memories and highlighting the emotional significance of shared meals. The second example emphasizes the importance of being with friends and family, suggesting that the enjoyment of cooking extends beyond the food itself. By linking home cooking and food to other enjoyable activities, these authors contribute to the perception of cooking as a fun.

Another aspect is the emphasis on shared struggles with the reader. Celebrity chefs for instance emphasize that cooking does not always have to be difficult or time-consuming. In more recent celebrity chef cookbooks, authors increasingly promote certain recipes as fast and easy to prepare. For instance:

• “Sometimes even a chef does not have time to eat.” (Jeroen Meus's Daily Meal; local chef, p. 6).

• “These are dishes you can get on the table in 30 minutes or less; or that are ridiculously quick to put together with just 10 minutes hands-on time, while the oven or hob then does the rest of the work.” (Jamie Oliver's 5 Ingredients; international chef, p. 15).

In both examples, there is a focus on time limitations and the need for quick meals. However, an important difference is that in the first example, a recipe with a short preparation time is provided as an exception to other recipes. In the second example, the author emphasizes that quick and easy recipes are one of the main focuses of the book itself. Possibly the duration of recipes has become an increasingly important concern of celebrity chefs over time as suggested in the content analysis of the recipes.

3.2.1.4. Discourse of “real cooking”

Celebrity chefs also tend to write in a normative way about “real cooking” and emphasize the importance of using fresh and local ingredients. They rationalize the goal of cooking itself and further authorize it with their appeal to tradition. Furthermore, they show aversion to alternatives like readymade meals and fast food. This urge to go back to home cooking, and the use of fresh ingredients is often seen in the discourse of chefs and helps to portray them as ordinary and authentic (Tominc, 2014b). For instance:

• “I am an advocate for real cooking. That is what fellow chefs call it. There's food with a preparation time and food that you order on a plate.… For me it is fine, as long as there are fresh ingredients on your plate, I am satisfied.” (Jeroen Meus's Winter Meal; local chef, p. 4).

• “As soon as you get the cooking bug, you're going to want to become as good at it as you can get, and eat food that tastes as good as you can make it, as quickly as possible.” (Jamie Oliver's Jamie's Food Revolution; international chef, p. 20).

These examples advocate for home cooking by emphasizing the joy and ease of cooking, as well as highlighting the importance of using fresh ingredients.

Besides the emphasis on “real cooking,” celebrity chefs also highlight the importance of locality and tradition. Local chefs often describe multiple dishes as traditional or even call them “classics.” While it may be more straightforward for local chefs to emphasize local and traditional dishes, international chefs use a similar tactic as they focus on widely popular and familiar dishes. This includes salads, soups, and omelets, but also dishes which they refer to as classic in a certain region like “Italian classics.” For instance:

• “For the first SOS Piet book, the main focus was on the classics of the Flemish kitchen.” (Piet Huysentruyt's SOS Piet; local chef? p.7).

• “Tomato soup, a wonderful classic soup — if you get the seasoning right, you'll be surprised at the difference between your homemade version and the canned stuff.” (Jamie Oliver's Jamie's Food Revolution; international chef, p. 133).

3.2.2. Discourse of influencers

3.2.2.1. Content

In contrast to celebrity chef cookbooks, influencer cookbooks have multiple chapters before getting to the recipes. All books include an anecdotal preface from the author, followed by prefaces by others. Subsequently, there are chapters that offer dietary advice and share more stories or anecdotes before presenting the recipes. The genre of influencer cookbooks appears to be more hybrid compared to that of celebrity chefs, incorporating lifestyle tips, workout tips, and scientific information. This blending of genres is often considered a characteristic of post-modernity (Barker, 1999). Looking at the recipes, in contrast to celebrity chefs, influencers do not provide a small story before talking about the recipes. However, they do provide extra tips to make recipes more healthy or tasty and clearly mention when recipes are vegan or gluten-free. For instance:

• “Looking at the total number of calories or the total fat content is simply not the right way to determine if food is healthy or unhealthy” (Pascale Naessens's Pure and Simple; influencer, p. 122).

As shown in the example, aside from instructions on how to prepare a meal, influencers provide also advice on how to judge whether a recipe is healthy or not.

3.2.2.2. A discourse of achievement, relatability, and experience

In influencers' cookbooks there is a common emphasis on personal experience. All books start with an anecdotal preface of the authors themselves talking about their journey toward a healthy diet, a strategy influencers use on other platforms as well (Chiu and Penders, 2021). For instance:

• “I tried all sorts of diets before. Name it and I tried it without lasting success.” (Nathalie Meskens's Plan Boost; influencer, p. 11).

• “During my time as a model, I experimented with nearly every possible diet. While they may have produced results in the first few weeks, I found that many of these diets were too extreme and took a toll on me both physically and psychologically.” (Pascale Naessens's Pure Enjoyment 1; influencer, p12).

In both examples, the authors discuss relatable struggles that many people face, such as the challenge of balancing a busy lifestyle with maintaining a healthy diet, or the difficulties of losing weight. They acknowledge the confusion that can arise when it comes to nutrition and navigating the world of diets.

After talking about the struggles they experienced, the authors tell the readers which initiatives they took to solve these problems. They describe how they did their own research and arrived at a durable solution. The discourse changes toward a discourse of achievement and authenticity in which the author acts as a role model (Johnston and Goodman, 2015). For instance:

• “I read tons of books and scientific studies, then based on the knowledge and experience I gained, I developed my own method to guide people toward a healthier diet.” (Sandra Bekkari's Never Diet Again 1; influencer, p. 11).

• “My body just followed; I did not have the feeling I was dieting.” (Nathalie Meskens's Plan Boost; influencer, p. 11).

In the first example, the author shares her personal journey of overcoming the struggles she faced, which creates a sense of relatability with the readers. By sharing her own experiences and demonstrating that she has successfully overcome these challenges, she becomes a source of inspiration and motivation for the readers who may be going through similar struggles. In the second example, the emphasis is placed on the ease of achieving the desired outcomes, the author aims to inspire readers and build trust in their expertise and advice.

Like celebrity chefs, influencers authorize their discourse by focusing on shared values and struggles. However, influencers tend to go a step further in emphasizing these aspects compared to celebrity chefs. They dedicate more time in their prefaces to discussing shared values and struggles, and they often incorporate more pictures to visually underline these values.

First, there is the value of family and friends. Influencers frequently refer to inviting people and enjoying food in company of others or eating together with family. For instance:

• “I think of these long cozy summer nights, enjoying a ‘tête-à-tête' with friends or family.” (Pascale Naessens's Pure Enjoyment 1; influencer, p. 9).

• “Every morning I cherish the opportunity to share a tasty and nutritious meal with my family.” (Sandra Bekkari's Never Diet Again 1; influencer, p. 32).

Aside from these textual examples, in the “Never diet again” series and the “Pure Pascale” series, there are also multiple pictures of the author enjoying dinner with family and friends. This enforces the link for the reader between cooking and enjoying food with loved ones.

Another aspect is the urge for simplicity. All influencers consistently emphasize the simplicity of their recipes and the importance of using natural ingredients. This trend aligns with past diet movements, such as the low-carbohydrate diet movement in the 1990s and 2000s (Knight, 2015). However, the focus influencers have on simplicity extends beyond their diets. Influencers romanticize being in nature and spending time outdoors with friends. The visual elements of influencer cookbooks, such as the “plan boost” and “Pure Pascale” often feature images of influencers in natural settings, highlighting their affinity for a basic lifestyle. For instance:

• “I need my walk just as much as my dogs do. Preferably outside in the beauty of nature, at any season, because they all have their charm.” (Nathalie Meskens's Plan Vegan; influencer, p.11).

• “We are part of nature. The more we live in harmony with it, the better we feel because we are nature ourselves.” (Pascale Naessens's Pure Food That Makes You Happy; influencer, p. 11).

3.2.2.3. Intertextuality

Intertextuality plays a significant role in influencers' cookbooks, serving to legitimize the authors' work by incorporating personal and expert authorities. In Nathalie Meskens' “plan boost” series, the preface is written by popular food influencer Kris Verburgh, spanning three pages. Similarly, influencers Pascale Naessens and Sandra Bekkari have prefaces from professors who recommend the book for its content and readability. The inclusion of these authoritative voices, along with the use of anecdotes from individuals who have successfully followed the diet, contributes to the notion of a consensus on what constitutes a healthy diet (Fairclough, 2001). This intertextuality not only authorizes the authors' perspectives but also generates trust and credibility among readers. Moreover, influencers often refer to documentaries and scientific studies, further enhancing the perceived healthfulness of their dietary recommendations and reinforcing their expertise (Baker and Rojek, 2020). One example of referring to an expert opinion is:

• “Professor Kim William, chief of the American College of Cardiology, is even more clear: “there are two types of cardiologists: vegans and those who did not read the studies.” (Nathalie Meskens's Plan Vegan; influencer, p.14).

3.2.2.4. Discourse of influencers' diet

When providing dietary advice, influencers distance themselves from the concept of “dieting,” which they view as wrong, extreme, and short-term focused. Instead, they promote their recommendations as a lifestyle choice that is healthy and long-term bound. Through their careful selection of words and deliberate avoidance of certain terms, influencers shape the discourse surrounding nutrition and create a sense of novelty and progressiveness (Moriarty and Pietikäinen, 2011).

In addition, influencers challenge the notion of restriction by emphasizing that the quality of food is more important than the quantity consumed. They position themselves as being anti-establishment as they address misconceptions that seem to exist not just among “most people,” “conventional science,” but also among governments and experts (Baker and Rojek, 2020). While others are misguided, they proclaim to tell the absolute truth or at least know the modern scientific insights.

• “Many people think they live healthy, it can be a lot healthier.” (Nathalie Meskens's Plan Boost; influencer, p. 16).

• “Many people still confuse healthy eating with dieting.” (Sandra Bekkari's Never Diet Again 1; influencer, p. 17).

In these examples, the authors discuss how “many people” perceive themselves as living a healthy lifestyle or how they associate healthy eating with dieting. Although it is not explicitly specified who these people are, the authors distance themselves from this perspective, taking an anti-establishment position. This can be seen as a persuasive strategy for readers who have struggled with weight loss in the past, as the authors present themselves as offering a sustainable solution.

The aversion influencers have toward dieting is amplified by their emphasis on the importance of personal choice and their proclamation that it is acceptable to deviate from dietary their guidelines at times. They even acknowledging that they themselves occasionally do so. This approach promotes a sense of autonomy and personal agency in relation to food choices. For instance:

• “I adhere 70% of the time to my guidelines, the other percentage I do what I want.” (Pascale Naessens's Pure Enjoyment 1; influencer, p. 183).

• “If your lifestyle adheres for 80% with the SANA method, you can fill in the other 20% yourself.” (Sandra Bekkari's Never Diet Again 1; influencer, p. 18).

In the given examples, readers are given the freedom and flexibility to fill in 20% and 30% of as they wish. This creates the impression of freedom and flexibility in their food choices. However, it is emphasized that strict adherence to the provided guidelines for the remaining percentage is crucial for the success of the diet. The discourse leans toward “healthism,” a discourse in which being healthy is portrayed as a moral responsibility and a choice (Baker and Rojek, 2019). The idea of self-responsibility in maintaining one's health has also been observed in the framing of dietary practices in other media channels (Orste et al., 2021).

When examining the diets influencers recommend in their cookbooks, it becomes evident that influencers employ similar discursive strategies. One such strategy is the glorification or demonization of food products based on specific aspects, a concept known as “Nutritional Reductionism” (Scrinis, 2008). In both the “Never diet again 1” and the “plan boost” series, there is a list of so-called “superfoods” is presented. Each of these foods are presented as exceptionally healthy due to a specific attribute they possess. On the other hand, influencer Pascale Naessens, proclaims that she does not use terms like superfoods, but glorifies natural unprocessed foods instead. Furthermore, all influencers show aversion to processed food, proclaiming how it makes us unhealthy. For instance:

• “The food industry can try as much as they want to compensate for the loss of useful nutrients by industrial processing. A natural product has way more to offer than any man-made product.” (Pascale Naessens's Pure Enjoyment 2; influencer, p23).

• “Goji berries are rich in antioxidants and can help prevent cancer and cardiovascular diseases.” (Nathalie Meskens's Plan Boost; influencer, p. 24).

Paired to nutritional reductionism the authors also use nutritional determinism, which involves oversimplifying the notion of being healthy to just nutrition (Scrinis, 2008). For instance:

• “When people eat healthier, they can omit 80% of their medication.” (Pascale Naessens's Pure Enjoyment 2; influencer, p. 6).

• “I have friends with diabetes, lost a friend to cancer, know a lot of women who only got pregnant after IVF…. Briefly I wanted to know how to optimize my body.” (Nathalie Meskens's Plan Boost; influencer, p. 12).

In the above example, complex health conditions such as cancer or diabetes are attributed solely to nutrition, which oversimplifies their origins. While this approach may not be scientifically valid, it is persuasive and provides individuals with a sense of control over their health.

3.2.2.5. The author as role model

The relatability and proclaimed success of the diet is further enhanced by the pictures and layout used throughout the books. Looking at the covers of all the books, it shows authors smiling and enjoying their dishes or enjoying preparing a meal. While the cover of celebrity chef cookbooks only seems to promise tasty dishes, influencers go further, promising a positive change to the readers' life. For instance:

• “Plan boost, the 68 recipes that changed my life.” (Nathalie Meskens's Plan Boost; influencer).

• “To eat better is to live better.” (Pascale Naessens's Pure Pascale; influencer).

Throughout the book, influencers frequently support their textual claims with pictures, a trend also seen online (Baker and Walsh, 2018). Their books feature numerous pictures of the authors practicing sports, spending quality time with family and friends, or immersing themselves in nature. These visuals portray a joyful and carefree lifestyle, serving as tangible evidence of the perceived success attributed to following the advocated diet (Baker and Rojek, 2020).

3.3. Explanation: social practice

In the third part of the analysis, the “social practice” in which the discourse occurs is examined, taking into account the social, cultural, and institutional conditions that shape it. This analysis pays particular attention to the dialectical relationship between the discourse and society, recognizing their mutual influence on each other.

3.3.1. Social changes

Current western societies are postmodern, characterized by the unprecedented fast pace at which social transformations occur (Whitley, 2008). One of these transformations is the shift from tradition and collectivism to individualism (Whitley, 2008). In the past, factors such as self-identity and social roles were largely predetermined, but now individuals have the freedom to shape their own self-identity. Accompanying this shift, there has been a cultural move toward self-fulfillment and self-actualization, emphasizing personal choice and autonomy rather than determinism (Giddens, 1991). People now have a tendency to develop a unique self-identity and pursue meaningful social roles, also referred to as the “authentic-self” (Whitley, 2008). Consequently, postmodern societies value concepts like authenticity and personal achievement (Whitley, 2008; Pineda et al., 2015; Baker and Rojek, 2019).

As diet is one factor through which people can strive toward this authentic self, people seek food media icons whom they relate to and perceive as trustworthy (Schouten et al., 2019; Baker and Rojek, 2020). Celebrity chefs and influencers fulfill this premise through their authorization strategies and their personal discourse. Furthermore, these food media icons must excel in what they do in order to fulfill an exemplary role successfully. In Flanders, for example, the best-selling cookbook authors already achieved a certain status before their books became popular. Celebrity chef Jeroen Meus not only had his own cooking show on television, but he also presented a television quiz show. Influencer Pascale Naessens had a successful career as a model and presented multiple TV shows before she wrote her books. Nathalie Meskens is an actress and artist, while Sandra Bekkari had a successful institute for weight management before she became an author. This aspect seems to have become increasingly important over the years as the list of authors of bestselling books became less diverse throughout the years. The followers of these bestselling authors also display strong loyalty. For instance, between 2014 and 2018, only four authors accounted for the twenty bestselling cookbooks. This pattern of concentrated popularity can also be observed on an international level, with celebrity chefs like Nigella Lawson, Yotam Ottolenghi, and Jamie Oliver amassing a strong following. This loyalty is evident not only in the consistent success of these chefs in the cookbook charts but also in their influence on local authors. For example, Jamie Oliver's concept of using five ingredients, introduced in 2017, was adopted by local influencer Pascale Naessens, who published two cookbooks featuring recipes with only four ingredients each. Additionally, previous studies have shown that Belgian celebrity chefs draw inspiration from their international counterparts, often adopting a similar role known as the “new lad.” This role challenges traditional gender stereotypes by depicting men engaging in household tasks traditionally associated with women (De Backer and Hudders, 2016).

3.3.2. Reflexive modernization

Another transformation is the increasing distrust in expertise and science, a concept referred to as “reflexive modernization” (Beck et al., 1994; Aupers, 2012). When specifically examining the field of food science, there are several underlying reasons contributing to this phenomenon. First, there are past scandals and conflicts of interest, resulting in a decreased trust in experts and the food industry (Garza et al., 2019).

Second, there is the issue of conflicting dietary advice, as new scientific evidence often challenges previously established consensuses (Garza et al., 2019). This, coupled with the overwhelming influx of information from various media sources, can lead to confusion among individuals, who may seek simplistic answers or information that aligns with their existing beliefs (Baker and Rojek, 2020). Consequently, there has been a shift away from traditional sources of information, with the rise of “new experts” such as celebrities and influencers (Whitley, 2008). These new experts often reject conventional scientific narratives. Furthermore, the public discourse became more conversation-like due to a resulting tension between information, entertainment and a more marketized discourse (Tominc, 2014b; Patrona, 2015), a process Fairclough refers to as “commercialization of public discourse” (Patrona, 2015).

4. Discussion

During this study, we conducted an in-depth analysis of the evolution in the discourse of popular cookbooks published between 2008 and 2019 to gain insight into three intertwined key points: (1) the discourse employed by chefs and influencers to amass significant followings, (2) the perspectives they advocate for regarding diet, cooking behavior, and lifestyle, and (3) the extent to which evolutions in discourse of cookbooks correspond with trends in society and may even contribute to social change.

Looking at the evolution of popular cookbook content in the 2010s, a clear shift can be observed from traditional cookbooks toward the cookbooks authored by celebrity chefs, and later on, cookbooks authored by influencers. Looking at the discourse (1), similar to Tominc (2014a), this study finds celebrity chef cookbooks to be a rather hybrid genre. These cookbooks employ added narratives, a personal discourse, and a focus on aesthetics provide the content in an entertaining manner. Instead of solely providing information, these books revolve around the authors' wisdom, emphasizing concepts such as “being yourself” and self-fulfillment as part of their professional ideology (Tominc, 2014a; Elias, 2017; Matwick, 2017). This trend became even more pronounced with the rise of influencers. Influencer cookbooks exhibit an even greater hybridity, featuring lengthier prefaces and devoting equal attention to themes such as lifestyle, time management, and health, alongside the culinary aspect itself.

The rise of influencers was facilitated by social media and likely and likely influenced the discourse of celebrity chefs as well (Baker and Rojek, 2019). Authors in the food media landscape started paying increased attention to health and personal factors (2), incorporating information such as “vegetarian,” “preparation time,” and “amount of calories.” This trend was adopted to a lesser extent in later celebrity chef cookbooks. The heightened focus on health and personal factors can be attributed to broader societal changes, including globalization and a societal emphasis on achievement and health. These changes highlight the dialectical relationship between discourse and society (3), where evolving societal values and aspirations shape the content and direction of food media discourse (Whitley, 2008). This is also illustrated by the societal anxiety toward the food chain (Elias, 2017) that is reflected in the authors' discourse. Among celebrity chefs, there is a strong inclination toward “real cooking” and a disdain for prepackaged meals (2). Influencers, on the other hand, advocate for “real food” and promote diets that prioritize organic, unprocessed, and plant-based choices. These attitudes and preferences are not only observed among food media figures but also resonate on a societal level, as the transnational organic food movement gains popularity and more individuals embrace cooking at home since the rise of celebrity chefs (Larsson, 2015; Taillie, 2018).

This societal anxiety toward the food chain is rooted in multiple causes, one of which is eroding trust in the nutrition sciences and food industry (3) (Garza et al., 2019). Past scandals, rejection of old scientific findings, and conflicts of interest fueled people's distrust (Garza et al., 2019). Additionally, the overwhelming amount of information available through various media channels makes it challenging to discern which claims are supported by reliable evidence (Garza et al., 2019). As such, people are more likely to seek information from sources they trust and can identify with (Baker and Rojek, 2019). Both celebrity chefs and influencers act on this through multiple forms of legitimation. First, they authorize their discourse through not just a personal discourse but also a focus on tradition and shared values (1). Second, celebrity chefs and influencers act as role models, as they are famous and successful, while portraying themselves as similar to the reader. This is especially the case among influencers, as they themselves are living proof that their diets and information are correct (Baker and Rojek, 2020). Influencers further authorize their discourse as they refer to each other and to scientists or documentaries to confirm their claims. Another aspect is the villainizing of conventional science and the food industry to further reinforce their statements. They also rationalize their discourse by providing people with oversimplified information on nutrition and disease, portraying their advice as “common sense.” This is particularly important as simple and easy to understand nutritional information has shown to be an effective way to influence individuals (Mariscal-Arcas et al., 2021). Finally, there is a focus on moral choice. They do not dictate their advice to readers, rather they show them a scenario of fulfillment and happiness that they can achieve by following the influencers' advice. This creates a sense of empowerment that can explain why their discourse proves to be effective in this and previous studies (Muturi et al., 2016; Proesmans et al., 2022).

This emphasis on individual choice, moral responsibility, and achievement reflects the individualistic postmodern society within which the authors operate (3) (Whitley, 2008; Baker and Rojek, 2020). Especially influencers reinforce this ideology by tackling existing concerns from an individualistic point of view. With an emphasis on personal choice, it seems that current cookbooks are used as much for inspiration as for information.

5. Conclusion

Modern cookbooks have evolved to serve as both sources of inspiration and information. Celebrity chefs and influencers have risen to prominence by adopting personal and entertaining approaches in their discourse. Celebrity chefs advocate for home cooking, emphasizing the importance of family and shared values. Influencers, on the other hand, take it a step further by promoting a natural and healthy lifestyle. Their overall discourse can be summarized as encouraging individuals to strive to be the best versions of themselves (Baker and Rojek, 2020). In essence, the modern cookbook discourse mirrors the broader societal trends of our postmodern and individualistic era, centered around moral choice, achievement, and personal responsibility.

6. Future research implications

With celebrity chefs and influencers becoming bestselling cookbook authors, as well as popular figures in online and conventional media, it would be interesting to conduct an extensive nutritional analysis of the dishes they recommend. This analysis would provide insights into the nutritional adequacy of their recommended diets. Furthermore, as influencers have a discourse of perfection and moral choice, it would be interesting to investigate the relation between following influencers and mental health or extreme diets (Whitley, 2008).

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

VP: conducted the analyses, interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript. MG, IV, and NT: helped shaping the design, supervised all steps in the study, and provided feedback at each stage in the writing process. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by the governmental agency Flanders Innovation & Entrepreneurship (VLAIO) under Grant Number AIO.SBO.2019.0002.01. VLAIO played no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the publishers Standaard Uitgeverij and Borgerhoff & Lamberigts for providing us cookbooks, the non-profit organization boek.be for providing us with data on cookbook sales in Flanders, and Adam Lederer for proofreading the manuscript as a freelancer.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2023.1205390/full#supplementary-material

References

Anderson, K. (2023). Popular fad diets: An evidence-based perspective. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 77, 78–85. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2023.02.001

Aupers, S. (2012). ‘Trust no one': modernization, paranoia and conspiracy culture. Eur. J. Commun. 27, 22–34. doi: 10.1177/0267323111433566

Baker, S. A., and Rojek, C. (2019). The Belle Gibson scandal: the rise of lifestyle gurus as micro-celebrities in low-trust societies. J. Sociol. 56, 1440783319846188. doi: 10.1177/1440783319846188

Baker, S. A., and Rojek, C. (2020). Lifestyle Gurus: Constructing Authority and Influence Online. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons.

Baker, S. A., and Walsh, M. J. (2018). ‘Good Morning Fitfam': Top posts, hashtags and gender display on Instagram. N. Media Soc. 20, 4553–4570. doi: 10.1177/1461444818777514

Barker, C. (1999). Television, Globalization and Cultural Identities. Buckingham: Open University Press Buckingham.

Beck, U., Giddens, A., and Lash, S. (1994). Reflexive Modernization: Politics, Tradition and Aesthetics in the Modern Social Order. Redwood City, CA: Stanford University Press.

Beyen, M. (2019). De taal van de geschiedenis: Hoe historici lezen en schrijven. Leuven: Universitaire Pers Leuven.

Bradfield, R. B. (1973). Journal of nutrition education. J. Nutr. Educ. 5, 14–8149. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3182(73)80040-8

Buisman, M. E., and Jonkman, J. (2019). Dietary trends from 1950 to 2010: A Dutch cookbook analysis. J. Nutr. Sci. 8, e5. doi: 10.1017/jns.2019.3

Byrne, E., Kearney, J., and MacEvilly, C. (2017). The role of influencer marketing and social influencers in public health. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 105, 76. doi: 10.1017/S0029665117001768

Chiu, M.-C., and Penders, B. (2021). “Maybe a Long Fast Is Good for You”: health conceptualisations in youtube diet videos. Front. Commun. 6, 6. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2021.625906

Clarke, T. B., Murphy, J., and Adler, J. (2016). Celebrity chef adoption and implementation of social media, particularly pinterest: a diffusion of innovations approach. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 57, 84–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2016.06.004

Daniels, S., Glorieux, I., Minnen, J., and van Tienoven, T. P. (2012). More than preparing a meal? Concerning the meanings of home cooking. Appetite 58, 1050–1056. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2012.02.040

De Backer, C. J. S., and Hudders, L. (2016). Look who's cooking. Investigating the relationship between watching educational and edutainment TV cooking shows, eating habits and everyday cooking practices among men and women in Belgium. Appetite 96, 494–501. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2015.10.016

Eidner, M. B., Lund, A.-S. Q., Harboe, B. S., and Clemmensen, I. H. (2013). Calories and portion sizes in recipes throughout 100 years: an overlooked factor in the development of overweight and obesity? Scand. J. Public Health 41, 839–845. doi: 10.1177/1403494813498468

Elias, M. J. (2017). Food on the Page: Cookbooks and American Culture. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Eriksson, G., and Andersson, H. (2016). andquot;To pose as a chefandquot;: Visual and Textual Representations of Masculinity in Cookbooks. p. 46–47. Available online at: https://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:oru:diva-53542 (accessed June 10, 2023).

Garza, C., Stover, P. J., Ohlhorst, S. D., Field, M. S., Steinbrook, R., Rowe, S., et al. (2019). Best practices in nutrition science to earn and keep the public's trust. Am J Clin Nutr. 109, 225–243. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqy337

Gezond leven (2019). Nieuwe adviezen van Hoge Gezondheidsraad bevestigen voedingsdriehoek. Vlaams Instituut Gezond Leven. Available online at: https://www.gezondleven.be/nieuws/nieuwe-adviezen-van-hoge-gezondheidsraad-bevestigen-voedingsdriehoek (accessed January 21, 2023).

Giddens, A. (1991). Modernity and Self-identity: Self and Society in the Late Modern Age. Redwood City, CA: Stanford University Press.

Giousmpasoglou, C., Brown, L., and Cooper, J. (2020). The role of the celebrity chef. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 85, 102358. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2019.102358

Henderson, J. C. (2011). Celebrity chefs: expanding empires. Br. Food J. 113, 613–624. doi: 10.1108/00070701111131728

Hevesi, D. (2010). Michel Montignac, Creator of Trend-Setting Diet, Dies at 66. The New York Times. Available online at: https://www.nytimes.com/2010/08/27/business/27montignac.html (accessed April 27, 2022).

Homan, M. M. (2007). The oldest cuisine in the world: cooking in Mesopotamia. Near Eastern Archaeology 70, 231. doi: 10.1086/NEA20361337

Janks, H. (1997). Critical discourse analysis as a research tool. Discourse: studies in the cultural politics of education 18, 329–342. doi: 10.1080/0159630970180302

Johnston, J., and Goodman, M. K. (2015). Spectacular Foodscapes. Food, Culture and Society, 18, 205–222. doi: 10.2752/175174415X14180391604369

Kaur, K., Arumugam, N., and Yunus, N. M. (2013). Beauty product advertisements: A critical discourse analysis. Asian Soc. Sci. 9, 61. doi: 10.5539/ass.v9n3p61

Knight, C. (2015). “We Can't Go Back a Hundred Million Years”. Food Cult. Soc. 18, 441–461. doi: 10.1080/15528014.2015.1043107

Korthals, M. (2017). Ethics of dietary guidelines: nutrients, processes and meals. J. Agricult. Environ. Ethics 30, 413–421. doi: 10.1007/s10806-017-9674-7

Larsson, T. (2015). The rise of the organic foods movement as a transnational phenomenon. Oxford Handbook Food Pol. Soc. 739–754. doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195397772.013.001

Lavorgna, A., and Di Ronco, A. (2019). Medical Misinformation and Social Harm in Non-Science Based Health Practices: A Multidisciplinary Perspective. Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge.

Mariscal-Arcas, M., Jimenez-Casquet, M. J., Saenz de Buruaga, B., Delgado-Mingorance, S., Blas-Diaz, A., Cantero, L., et al. (2021). Use of social media, network avenues, blog and scientific information systems through the website promoting the mediterranean diet as a method of a health safeguarding. Front. Commun. 6, 599661. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2021.599661

Martin, D. (2003). Dr. Robert C. Atkins, Author of Controversial but Best-Selling Diet Books, Is Dead at 72. The New York Times. Available online at: https://www.nytimes.com/2003/04/18/nyregion/dr-robert-c-atkins-author-controversial-but-best-selling-diet-books-dead-72.html (accessed January 20, 2022).

Matwick, K. (2016). A Critical Discourse Analysis of Language and Gender in Cookbooks by Female Celebrity Chefs. PhD Thesis. Gainesville, FL: University of Florida.

Matwick, K. (2017). Language and gender in female celebrity chef cookbooks: Cooking to show care for the family and for the self. Crit. Discourse Stud. 14, 532–547. doi: 10.1080/17405904.2017.1309326

Mitchell, J. (2008). New Zealand cookbooks as a reflection of nutritional knowledge, 1940–1969. Nutrit. Dietet. 65, 134–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0080.2008.00240.x

Montville, J. B., Ahuja, J. K. C., Martin, C. L., Heendeniya, K. Y., Omolewa-Tomobi, G., Steinfeldt, L. C., et al. (2013). USDA food and nutrient database for dietary studies (FNDDS), 5.0. Procedia Food Sci. 2, 99–112. doi: 10.1016/j.profoo.2013.04.016

Moriarty, M., and Pietikäinen, S. (2011). Micro-level language-planning and grass-root initiatives: a case study of Irish language comedy and Inari Sámi rap. Current Issu. Lang. Plan. 12, 363–379. doi: 10.1080/14664208.2011.604962

Muturi, N. W., Kidd, T., Khan, T., Kattelmann, K., Zies, S., Lindshield, E., et al. (2016). An Examination of factors associated with self-efficacy for food choice and healthy eating among low-income adolescents in three U.S. states. Front. Commun. 1, 1. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2016.00006

Notaker, H. (2017). A History of Cookbooks: From Kitchen to Page Over Seven Centuries (Vol. 64). Berkeley, CA: Univ of California Press,.

NPD Group (2018). Cookbook Category Sales Rose 21 Percent, Year over Year. Cookbook Category Sales Rose 21 Percent, Year over Year. Available online at: https://www.npd.com/wps/portal/npd/us/news/press-releases/2018/cookbook-category-sales-rose-21-percent-year-over-year-the-npd-group-says/ (accessed October 26, 2020).

NPD Group. (2020). Bread Cookbooks Rise in the Time of COVID-19. Available online at: https://www.npd.com/wps/portal/npd/us/news/press-releases/2020/bread-cookbooks-rise-in-the-time-of-covid-19–the-npd-group-says/ (accessed October 26, 2020).

Orpin, D. (2005). Corpus linguistics and critical discourse analysis: examining the ideology of sleaze. Int. J. Corpus Linguistics 10, 37–61. doi: 10.1075/ijcl.10.1.03orp

Orste, L., Krumina, A., Kilis, E., Adamsone-Fiskovica, A., and Grivins, M. (2021). Individual responsibilities, collective issues: the framing of dietary practices in Latvian media. Appetite 164, 105219. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2021.105219

Patrona, M. (2015). Synthetic Personalization. In: The International Encyclopedia of Language and Social Interaction. New York, NY: American Cancer Society. p. 1–6.

Pineda, A., Hernández-Santaolalla, V., Rubio-Hernández, M., and del, M. (2015). Individualism in Western advertising: A comparative study of Spanish and US newspaper advertisements. Eur. J. Commun. 30, 437–453. doi: 10.1177/0267323115586722

Proesmans, V. L. J., Vermeir, I., de Backer, C., and Geuens, M. (2022). Food media and dietary behavior in a belgian adult sample: how obtaining information from food media sources associates with dietary behavior. Int. J. Public Health. 67, 1604627. doi: 10.3389/ijph.2022.1604627

Rashid, B. N. (2020). Discourse Analysis of Advertisements: A Critical Insight Using Fairclough's Three Dimensions. Talent Development & Excellence. p. 12.

Schouten, A. P., Janssen, L., and Verspaget, M. (2019). Celebrity vs. Influencer endorsements in advertising: the role of identification, credibility, and Product-Endorser fit. Int. J. Advert. 39, 1–24. doi: 10.1080/02650487.2019.1634898

Scrinis, G. (2008). On the ideology of nutritionism. Gastronomica 8, 39–48. doi: 10.1525/gfc.2008.8.1.39

Segers, Y. (2005). Food recommendations, tradition and change in a Flemish cookbook: Ons Kookboek, 1920–2000. Appetite 45, 4–14. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2005.03.007

Segura, J. (2016). The Bestselling Cookbooks of 2015. PublishersWeekly.Com. Available online at: https://www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/industry-news/cooking/article/69064-the-bestselling-cookbooks-of-2015.html (accessed March 25, 2022).

Sperber, D. (2010). The guru effect. Rev. Philos. Psychol. 1, 583–592. doi: 10.1007/s13164-010-0025-0

Statistiek Vlaanderen. (2022). Vlaanderen in cijfers 2023 (p. 29). Statistiek Vlaanderen.Available online at: https://www.vlaanderen.be/publicaties/vlaanderen-in-cijfers

Swanson, C. (2015). The Bestselling Cookbooks of 2014. The Bestselling Cookbooks of 2014. Available online at: https://www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/industry-news/cooking/article/65184-the-bestselling-cookbooks-of-2014.html (accessed March 25, 2022).

Swanson, C. (2017). The Bestselling Cookbooks of 2016. PublishersWeekly.Com. Available online at: https://www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/industry-news/cooking/article/72521-the-bestselling-cookbooks-of-2016.html (accessed March 25, 2022).

Swanson, C. (2018). The Bestselling Cookbooks of 2017. PublishersWeekly.Com. https://www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/industry-news/cooking/article/75832-the-bestselling-cookbooks-of-2017.html (accessed March 25, 2022).

Taillie, L. S. (2018). Who's cooking? Trends in US home food preparation by gender, education, and race/ethnicity from 2003 to 2016. Nutr. J. 17, 41. doi: 10.1186/s12937-018-0347-9

Tominc, A. (2012). Jamie Oliver as a Promoter of a Lifestyle: Recontextualisation of a Culinary Discourse and the Transformation of Cookbooks in Slovenia. Lancaster: Lancaster University (United Kingdom).

Tominc, A. (2014a). Legitimising amateur celebrity chefs' advice and the discursive transformation of the Slovene national culinary identity. Eur. J. Cult. Stud. 17, 316–337. doi: 10.1177/1367549413508743

Tominc, A. (2014b). Tolstoy in a recipe: globalisation and cookbook discourse in postmodernity. Nutr. Food Sci. 44, 310–323. doi: 10.1108/NFS-01-2014-0009

Van Leeuwen, T. (2007). Legitimation in discourse and communication. Disc. Commun. 1, 91–112. doi: 10.1177/1750481307071986

Whitley, R. (2008). Postmodernity and mental health. Harvard Rev. Psychiatry 16, 352–364. doi: 10.1080/10673220802564186

Keywords: cookbook, influencer, celebrity chef, diet, food writings, food media, healthy eating

Citation: Proesmans VLJ, Vermeir I, Teughels N and Geuens M (2023) Food writings in a postmodern society: a discourse analysis of influencer and celebrity chef cookbooks in Belgium. Front. Commun. 8:1205390. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2023.1205390

Received: 13 April 2023; Accepted: 27 June 2023;

Published: 20 July 2023.

Edited by:

Marco Mandolfo, Polytechnic University of Milan, ItalyReviewed by:

Keri Matwick, Nanyang Technological University, SingaporeSabiha Ahmad Khan, The University of Texas at El Paso, United States

Copyright © 2023 Proesmans, Vermeir, Teughels and Geuens. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Viktor L. J. Proesmans, dmlrdG9yLnByb2VzbWFuc0B1Z2VudC5iZQ==

Viktor L. J. Proesmans

Viktor L. J. Proesmans Iris Vermeir

Iris Vermeir Nelleke Teughels2

Nelleke Teughels2 Maggie Geuens

Maggie Geuens