- 1Department of General Psychology and Methodology, University of Bamberg, Bamberg, Germany

- 2Research Group EPÆG (Ergonomics, Psychological Æsthetics, Gestalt), Bamberg, Bavaria, Germany

Communication is critical in a wide variety of fields. Successful intra-organizational communication plays a significant role in building trust by creating an environment that empowers leaders to lead effectively, motivates employees to work, and thus contributes to organizational performance. In the context of cluster management, communication within the cluster, especially between the cluster leadership and the often vast number of cluster members, plays a pivotal role in successful and effective cluster development. A cluster typically operates in a regional context characterized by multi-agent, multi-objective, multi-vision, and pluralistic processes, methods, competencies, expertise, and aims. Cluster leadership is usually associated with particular difficulties in addressing these challenges. The primary needs and demands to fulfill such a role are to bring together a large number of partly competing actors involved in a cluster, to build up a trustful and open network, to include different cultures, and to harmonize institutional agendas. The main aim is to develop and establish a common ground to communicate and coordinate joint work efforts, which can mutually benefit and create synergies. The present article conceptualizes Effective internal Cluster Communication and Place Leadership as determinants for successful cluster developments. Despite the multiplicity of actors and sometimes even competing interest groups, Effective Place Leader Cluster Communication (EPLCC) enables clusters to inspire common, cooperative, collaborative and synergetic ways of working together. This is key to cluster development, successful and goal-directed cluster operation, and a sustainable operation of the cluster.

Introduction

Communication is critical in a wide variety of fields. Communication plays an integral part in the process of organizational sustainment and transformation (Lundberg and Brownell, 1993). In this context, communication is understood as a collaborative, dialogic process that organizes entrepreneurial activities at different levels.

It is good communication that enables managers to share information and expectations with others. In this way, processes and their status are made transparent and accessible. Transparency within the company, in turn, plays an important role in building motivation and trust. Good organizational communication skills help to develop better understanding and beliefs among people and inspire them to follow common values (Luthra and Dahiya, 2015). Kouzes and Posner (1993) found in a study that trust is a factor that every person wants to have before enthusiastically following someone in any situation, whether it is a battlefield or a meeting room. In developing the trust factor, leaders must be able to share their vision by interacting with their environment. If this is accomplished, successful intra-organizational communication leads to operating more effectively and efficiently within an organization. Thus, communication enables leaders to lead successfully in the first place (Frese et al., 2003; Barrett, 2006). From a today's perspective, the concept of organizational communication goes far beyond the one-way linear transmission communication model.

Trust, commitment, identification with the organization—all of this is needed to motivate company employees and thus successfully implement entrepreneurial activities. These aspects become even more decisive when there is no commitment or bond to pursue a common goal.

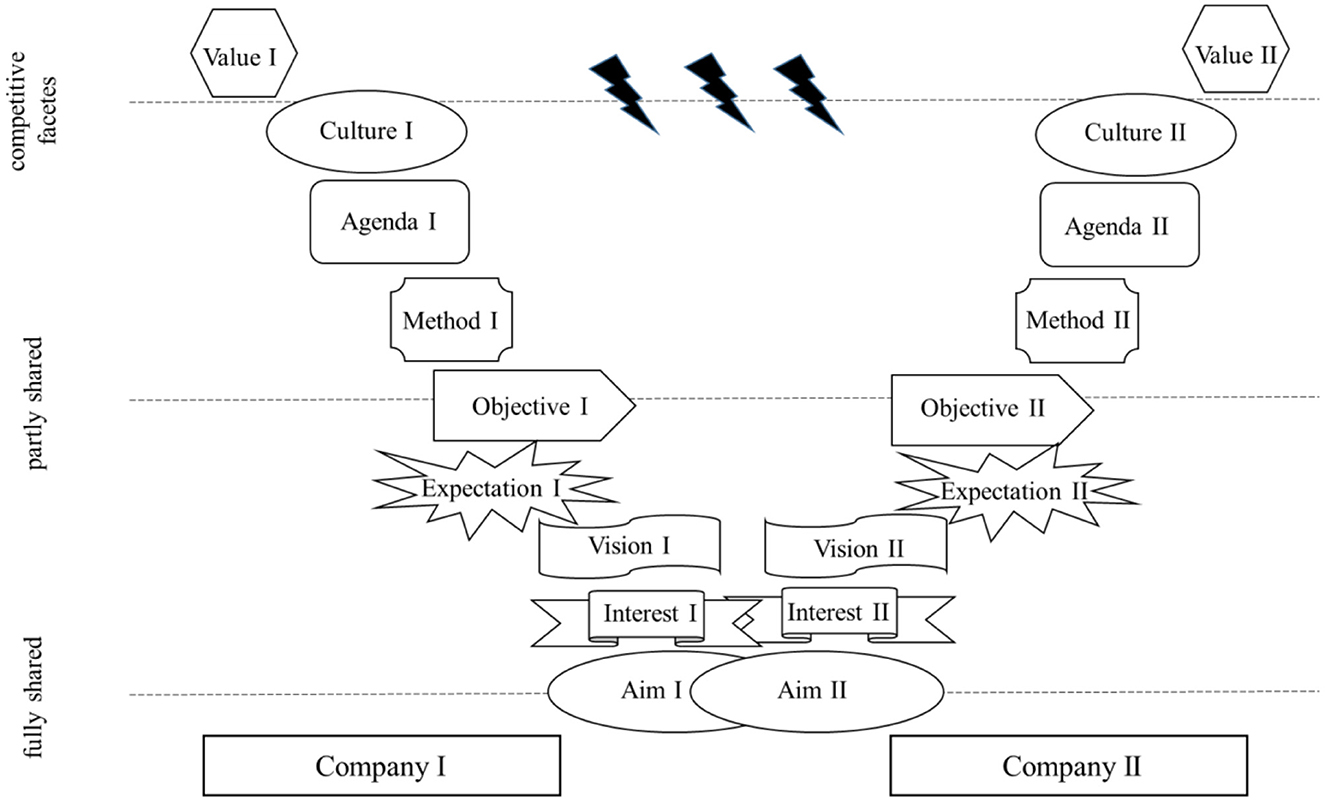

In the context of cluster management, communication within the cluster, especially between the cluster management and the multitude of cluster members, plays a particularly important role in successful and effective cluster development. Porter (1998) described clusters as geographically concentrated groups of companies and institutions working together in a particular field. Clusters include specialized suppliers, background service providers, companies in related industries, and institutions such as universities, government organizations, trade agencies, professional organizations and associations linked in a field by their similarities and comparative characteristics. A cluster typically operates in a regional context characterized by multi-agent, multi-objective, multi-vision, and pluralistic processes, methods, and aims. With so many actors involved in a cluster, it is often a major challenge to balance the different cultures and institutional agendas and find common ground and mutual benefit (Burfitt and Macneill, 2008). One of the goals of clusters is to ensure that cluster members experience growing innovation and competitiveness through cluster membership and related activities. In this regard, the decision to share initiatives in technical and technological innovation with other actors in the area is not necessarily self-evident. Due to sometimes converging expectations, values and interests, obstacles such as mistrust, lack of interest, or unwillingness to cooperate can arise (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Fully shared, partly shared and competitive facets of two exemplary companies working within the same cluster.

Cluster organizations must set aside their competitive mindset in favor of a common, larger objective, a shared vision, in order to be able to build a trustworthy and open network. These requirements must emerge within the cluster through the willingness and commitment of the cluster members and cannot be externally imposed. The main goal is to develop and establish a common basis for communication and coordination of joint work efforts from which all sides can benefit and create synergies. Successful communication has to preserve the identity of the individual companies that stand for themselves, but at the same time it has to foster the adoption of the cluster identity. Clusters must first convince companies and institutions to join the cluster and ensure that everyone's interests and goals are reflected in the cluster. Cluster members must then be mobilized around a common strategy and vision. Internal cluster communication forms the basis for the cluster's function by shaping the cluster's identity and facilitating its appropriation by cluster members.

Even though Porter's (1998) cluster concept has become the standard concept of practice in this field as a tool for promoting national, regional and local competitiveness, innovation and growth, and there are numerous publications on clusters, little importance has been given in research to the aspect of communication within clusters. In this article, we aim to draw attention to the role of communication in successful cluster development, as we are convinced that internal communication of clusters is important for their success since clusters are based on networks. The primary need of networks is communication between their members (Borgulya et al., 2022). To do so, we conceptualize Effective internal Cluster Communication and Place Leadership (Ganske and Carbon, 2023) as determinant for successful cluster development. We demonstrate that despite the multiplicity of actors and sometimes competing interest groups, Effective Place Leader Cluster Communication (EPLCC) that addresses both the individual and social identities of cluster members enables clusters to inspire common, cooperative, and collaborative ways of working together and thus represents a key success factor for cluster development and leadership.

Communication as a determinant of success in organizations

Communication is the key to an organization's success as a system of individuals working together toward common goals. In times characterized by recurring economic crises, globalization, digitalization, climate change, scarcity of natural resources, and a host of other societal dynamics such as migration and demographic change, and more recently, the COVID-19 pandemic or the Russo-Ukrainian War, an organization must be able to respond quickly. Organizational members need clear, relevant, and fully comprehensive information (Blazenaite, 2011). Research shows that effective communication is paramount in any organization. Ensuring open interaction with free flow of information, managing organizational communication processes, and creating an open and adaptable communication system yields extensive organizational benefits (Szukala, 2001; Tourish and Hargie, 2004; Eisenberg et al., 2009). A functioning communication system at all levels of the organization ensures the management of information, which brings stability and order to an organization. It also promotes important organizational processes that allow a company to adapt, change, and innovate (Blazenaite, 2011). Good communication enables an organization to succeed and grow.

There is no standard definition of organizational communication (Roberts et al., 1974). Organizational communication influences and is influenced by its environment. In doing so, it involves creating and maintaining by encompassing message flow, people and their relationships, attitudes, feelings, and capabilities (Lundberg and Brownell, 1993). “Communication […] is not a process that takes place in organizations, it is the constitutive means by which organizing occurs” (Eisenberg and Riley, 1988, p. 132). Organizational communication enables the exchange of contact and information between the departments and units of an organization and their environment for the purpose of operating the organization and achieving its objectives (Blazenaite, 2011). Organizational communication includes decision-making and conflict management in an organization. It enables the creation and maintenance of organizational images, missions, and values, as well as power and politics within organizations (Blazenaite, 2011). Communication becomes “organizational” when collective action finds expression in an identifiable actor, and the actor is recognized by the community as the legitimate expression of such action (Taylor and Cooren, 1997).

Communication takes place internally and externally. Internal communication is understood as the strategic management of interactions and relationships between stakeholders at all levels within organizations (Borgulya et al., 2022). Internal corporate communication is defined as “communication between an organization's strategic managers and its internal stakeholders, designed to promote commitment to the organization, a sense of belonging to it, awareness of its changing environment and understanding of its evolving aims” (Welch and Jackson, 2007, p. 193).

The literature provides evidence that the performance and effectiveness, and thus the success, of an organization is closely correlated with the communication in the organization. Good communication leads to high performance and effectiveness, while poor organizational communication is likely to cause organizations to struggle (Goldhaber et al., 1978). Studies show that communication is positively correlated with many organizational outcomes necessary for organizational success. These include productivity, organizational commitment, performance/profit, social behavior, and job satisfaction. In contrast, failure in communication can lead to non-functional outcomes such as stress, job dissatisfaction, low trust, decrease in organizational commitment, intention to quit, and employee absenteeism (Linkert, 1967; Husain, 2013) and this may negatively impact organizational effectiveness and success (Zhang and Agarwal, 2009).

Good communication informs and educates employees at all levels and motivates them to support the organizational strategy (Barrett, 2002). In general, organizational communication has two purposes of meeting the overarching objective of organizational success: one purpose is to inform employees about their work tasks and the organization's policy issues; the second goal of organizational communication is to establish a community within the organization (Postmes et al., 2001; de Ridder, 2004). In more detail, the following six factors can be defined as correlating with organizational success, and some of which are mutually dependent and which are positively influenced by good organizational communication.

Understanding

Understanding and comprehending why organizations need to evolve their goals must be ensured through organizational communication. Good communication skills help build better understanding and beliefs among people, inspiring them to follow the values their leader wants them to follow (Luthra and Dahiya, 2015). Knowing the reasons for change makes it easier to reduce uncertainty and create willingness to adapt to change (Husain, 2013). Since organizations operate in a dynamic environment with a high pace of change, internal corporate communications must be designed to develop an awareness of changes in the organization's environment (Welch and Jackson, 2007). Changes in the macro, micro, and internal environments cause the organization to change. Effective internal organizational communication should enable an understanding of the relationship between ongoing changes in the environment and the resulting need to review strategic direction. In this way, employees develop an understanding of the organization's evolving goals. Employees' understanding of strategic direction contributes to the development of commitment among them (Asif and Sargeant, 2000; de Ridder, 2004; Welch and Jackson, 2007).

Employee participation

When employees have the opportunity to participate in decision-making, they will feel as important persons for the organization (Kulachai et al., 2018), resulting in increased organizational commitment and employee engagement (Bonache, 2005). Employee participation in decision-making is associated with higher job satisfaction (Konovsky et al., 1987; Parker et al., 1997). Employees who participate in decision-making are more satisfied and more committed to the organization. Employee participation increases their input into decisions affecting their welfare and performance (Glew et al., 1995). Conversely, a study by Appelbaum et al. (2013) found that insufficient participation in decision-making leads to low job satisfaction and employee engagement. Hyo-Sook (2005) found that excellent organizations have management structures that enable employee participation in decision-making. Moreover, greater participation of lower-level employees in decision-making positively affects the efficiency of the decision-making process (Heller et al., 1988). A growing body of research suggests that employee involvement has a positive impact on change implementation (Sims, 2002) and productivity (Huselid, 1995). Knowing the reasons for change makes it easier to reduce uncertainty and create the willingness to adapt to change (Husain, 2013).

Trust

In organizations, effective intra-organizational communication plays an important role in building trust by creating an environment that enables leaders to lead effectively, motivates employees to work (Luthra and Dahiya, 2015), and thus contributes to organizational performance. Trust leads to effects such as more positive attitudes, higher levels of collaboration, and thus better performance (Mayer et al., 1995; Jones and George, 1998). Trust and commitment can be referred to as byproducts of open, appropriate, clear, and timely communication (Chia, 2006). Trust can be facilitated through effective communication via openness and compassion. Communication practices within an organization are believed to have an important impact on the level of trust employees have in their managers and in the organization's leadership, as well as their commitment to the organization (Husain, 2013). Sparrow and Cooper (2003) emphasized the role of trust as a dimension of the social climate in organizations, highlighting its role as an antecedent to commitment and noting that low levels of trust are associated with poor communication. Good communication leads to trust and understanding of a corporate strategy and thus to greater commitment, identification, motivation and higher organizational performance.

Commitment

Commitment can be understood as the nature or degree of loyalty to the organization. Commitment is described as a positive employee attitude and is defined in terms of individual identification and involvement with an organization (de Ridder, 2004). Studies in the field of relationship research have shown that perceptions of the quality of relationships in the organization and perceptions of the quality of communication have a strong influence on member satisfaction and commitment to the organization. Openness, honesty, trustworthiness, credibility, influence, understanding, similarity, and competence are variables that influence these qualities. A positive perception of the overall climate in an organization is related to members' sense of commitment, their ability to influence the organization, and their satisfaction with the system (Goldhaber et al., 1978). Employee effectiveness and commitment depend on their knowledge and understanding of the organization's strategic issues (Tucker et al., 1996). Communication must be well managed so that confusion is always avoided through clear, accurate, and honest messages (Abraham et al., 1999). According to Pascale (1984), people committed to a vision are more important than a well-designed strategy because they successfully accelerate change processes (Larwood et al., 1995). Allen (1992) found that commitment and support derive from communication with top management and superiors, as well as communication with co-workers, leading to a sense of belonging, which in turn increases commitment. A sincere and effective communication style among organizational members enables members to integrate into the organization as employees internalize the organization's goals and rules. Thus, employee commitment increases, and with the increase in job satisfaction, the employee contributes to the increase in the organization's success (Husain, 2013).

Identification with the organization

According to Cornelissen (2004, p. 68), the feeling of positive belonging can be expressed as: “a “we” feeling … allowing people to identify with their organizations.” Identification is also seen as a persuasive strategy that organizations use to influence relationships with internal stakeholders by emphasizing shared beliefs and values that thereby fulfill individual needs for belonging (Cheney, 1983). Internal communication influences the degree to which employees identify with their organization and their attitudes toward supporting the organization (Smidts et al., 2001). Organizational communication is seen as an important antecedent to the self-categorization process that helps define a group's identity and create a sense of community that meets the needs of the organization (Postmes et al., 2001; de Ridder, 2004). A sense of belonging and identification with the organization is strongly influenced by participation, commitment, and satisfaction with the practices, policies, and goals of the system. Communication has been critical to creating organizational cultures and identifying with the organization (Pacanowsky and O'Donnell-Trujillo, 1982; Smidts et al., 2001).

Motivation

Motivation is the influence or drive that causes one to behave in a certain way and is described as consisting of energy, direction, and sustainability (Kroth, 2007). Communication has also been shown to be an effective tool in motivating employees (Luecke, 2003). Studies in the field of organizational communication have shown that the adequacy of information provided by the organization also contributes to employee job satisfaction, which encourages and motivates employees (Husain, 2013). Predictors of motivation have been shown to include job satisfaction, perceived fairness, and organizational commitment (Schnake, 2007). Motivation is influenced either positively or negatively by the experiences an employee has in a particular work environment and with managers (Gilley et al., 2009). Strong motivations promote strong efforts to complete the action despite great difficulties (Husain, 2013). A shared organizational vision positively affects motivation and identification with the organization. Visions motivate people to act and inspire them to go beyond their current state. Deeper than goals or strategies, desired images of the future or the hoped-for future can provide a sense of mission (Boyatzis et al., 2015). A vision should inspire and motivate employees to perform exceptionally. Griffin et al. (2010) found that leaders who developed a vision achieved more openness and adaptability in organizations. Therefore, leaders must ensure that employees understand the importance of the vision. The vision must be communicated in a way that generates enthusiasm and inspires subordinates, colleagues, or customers (Frese et al., 2003).

Clusters—between competition and cooperation

Cluster theory has become a standard concept and serves as a tool to promote national, regional, and local competitiveness, innovation, and growth by acting as a generator that provides potential advantages in perceiving both the need and the opportunity for innovation (Porter and Stern, 2001). The OECD (1999, 2001) entitled innovative clusters as a driver of national economic growth. The most widely accepted definition of clusters is based on Porter, who describes clusters as “geographic concentrations of interconnected companies, specialized suppliers, service providers, firms in related industries, and associated institutions (e.g., universities, standards agencies, trade associations) in a particular field that compete but also cooperate” (Porter, 2000b, p. 15). Porter's definition has key distinguishing elements: first, a regional cluster consists not only of companies, but also of a specific institutional environment that is also part of the cluster. These institutions include supporting institutions such as the cluster organization, but also research and educational institutions that serve as the basis for innovation networks and human capital formation. Second, the definition indicates that there is an external boundary to clusters. The first limitation refers to the fact that they are companies and institutions “in a certain field.” Thus, there is a certain technological proximity within a cluster, which forms the basis for a variety of exchange processes and synergies. Companies and institutions that use other technologies are outside this “particular field” and thus outside the cluster. The second limitation is of geographical nature (Menzel and Fornahl, 2005). In a cluster, the companies and their institutional environment are spatially concentrated.

Clusters affect a company's competitive advantage through synergistic effects by increasing the productivity of the company, guiding the direction and the pace of innovation, and stimulating the conformation of new business which also enlarges and reinforces the cluster itself (Porter, 1998; Borgulya et al., 2022). Being part of a cluster enables the company to work more productively, access more information, use technology, cooperate with related companies, and ultimately stimulate improvements to achieve better performance. The networks necessary for these benefits are based on interpersonal relationships and trust. Externalities result from the concentration of many people working on problems in a similar or related set of industries, skill sets, and processes that produce a widely shared understanding of the problem and its workings. The result is greater innovation with respect to product, process, or marketing that lowers costs and generates greater productivity for firms in the region. It is the “social glue (that) binds clusters together, contributing to the realization of this potential […] Relationships, networks, and a sense of common interest undergird these circumstances. The social structure of clusters thus takes a central importance” (Porter, 2000a, p. 264).

According to Wolman and Hincapie (2014) which draw on Gordon and McCann (2000) clustering can be divided into two forms: the pure economies of agglomeration and the social network model of clustering. The first results from firms located in geographic proximity to each other. The cost-savings that come from lower input costs and increased productivity are external benefits to firms that come about through this proximity. A pure agglomeration economy does not require interaction between actors, but the agglomeration component of the cluster concept leads to an increase in regional economic performance. The social network model of clustering refers to the cooperation part and thus, the resulting knowledge spillover of the cluster concept. In this model, informal networks of individuals across firms and related institutions (e.g., trade associations, universities, research institutes, and labor organizations) yield the transmission of knowledge generating innovation and adopting advanced and improved production processes, marketing, and research techniques. Communication presents a key role. Combining the two forms of clustering one can see that clusters can bring several fundamental benefits.

Cluster management plays a crucial role in the success of a cluster. It organizes and coordinates the activities of a cluster in accordance with the cluster strategy to achieve clearly defined goals. It focuses on mediating and facilitating the relationship between cluster members. Cluster management ensures that cluster members open up, are willing to cooperate, conflicts of interest are eliminated, the various agendas of cluster members are unified into common goals and collective actions, and that organizations see sufficient added value from their participation in cluster activities (Borgulya et al., 2022). In this regard, the coordination of communication within the cluster plays an important role, as the internal architecture of cluster organizations is based on naturally established, voluntary, and constructive interaction and collaboration among cluster members (Rosenfeld, 1996). Therefore, promoting internal and external communication is one of the most fundamental tasks of cluster management, in addition to the many other specific functions (Borgulya et al., 2022).

Communication must be directed in such a way that, in accordance with the Dual Identity Theory, both identities of the cluster members are addressed and preserved. The Dual Identity Theory (also known as Social Identity Theory) was developed by Henry Tajfel in the 1970s and is a social psychological theory that explains how people develop and maintain multiple identities simultaneously due to their membership in different social groups. Tajfel argued that a person's self-concept is based not only on their individual characteristics but also on their social group membership. The theory states that people have both a personal identity (unique characteristics and traits) and a social identity (based on group membership). According to the theory, people tend to group themselves and others into social groups based on shared characteristics. Individuals then become attached to their own social group and develop a sense of belonging and loyalty to that group. This social identity provides a sense of self-esteem and affirmation and also shapes their attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors. The theory states that people can have multiple social identities that are relevant to different contexts and situations. For example, someone may identify as both a member of a religious group and a member of a sports team and behave differently in each context based on the norms and values of those groups. Dual identification can lead to a state in which both identities are simultaneously recognized and promoted (see, e.g., Tajfel and Turner, 1979; Hogg and Terry, 2000; Prasch et al., 2022).

However, cluster management literature considers cluster communication only as a peripheral factor of cluster management and development (Rosenfeld, 2002; Blassini et al., 2013; Hartmann, 2016). To our knowledge, there are few studies that take a closer look at the forms of communication [whether simple communication models or more complex ones that view communication as a collaborative process in which all parties work together to identify common goals and interests while recognizing that different stakeholders may have different perspectives, experiences, and priorities, such as the consensus model (see e.g., Lewin, 1948; Fisher et al., 2011)] in a cluster. Too often, cluster communication is either not addressed at all or effective communication is seen as a given. Nevertheless, in our contribution here, we want to show that internal cluster communication makes a central contribution to the success of the cluster by addressing the personal identity of the cluster companies on the one hand, while at the same time strengthening the social identity of the cluster members and thus harmonizing the competitive facets of companies working within the cluster, as shown in Figure 1.

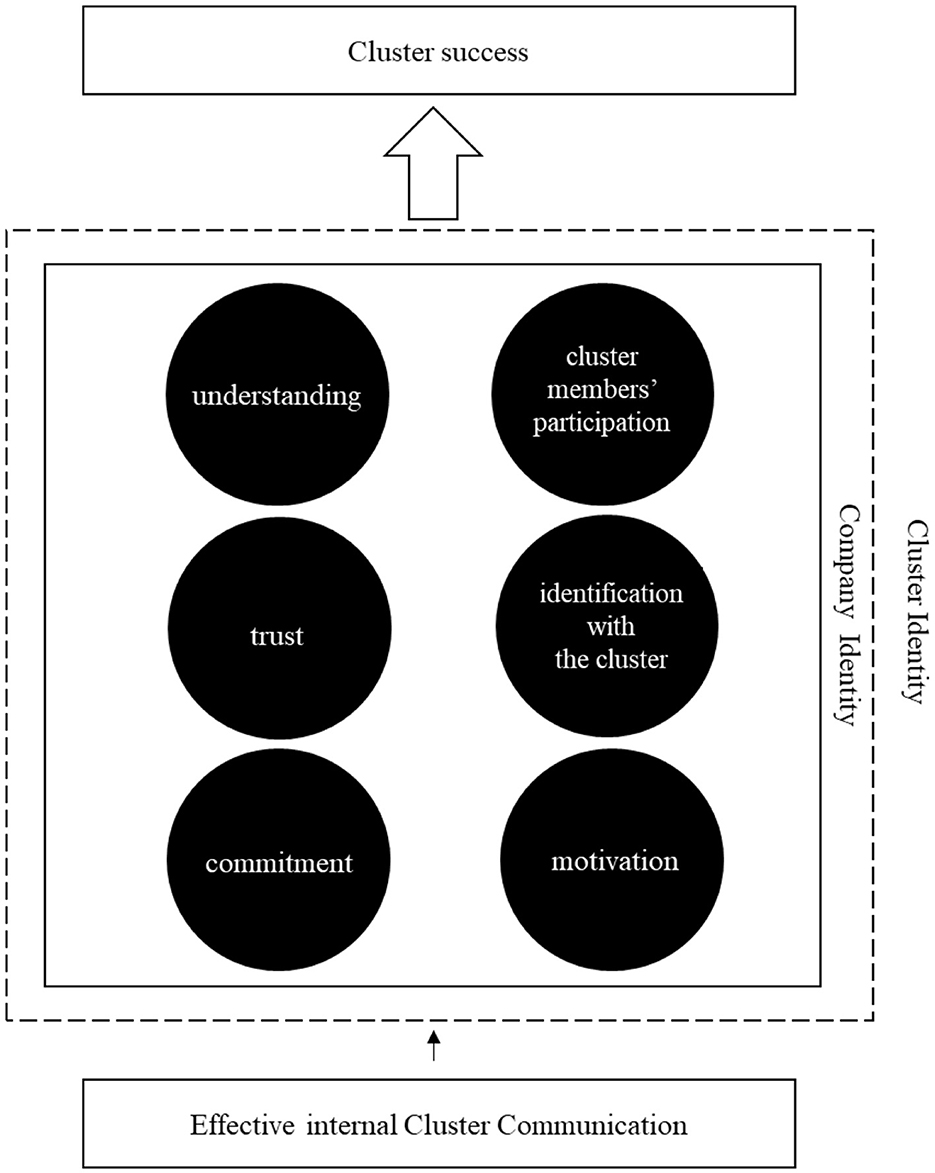

Businesses and other organizations are not the same as clusters in terms of how they function, but they do share some common characteristics. According to Borgulya et al. (2022), these include the existence of goals, strategies, and values; management of activities and planning of future actions; and the need for communication. Internal communication in companies and other organizations is not identical to communication in clusters, but because of the common characteristics, it can be argued that communication in all organizations has similar goals, core functions and elements (Borgulya et al., 2022). The internal communication of a cluster should boost the cluster's operation. Like organizational communication in general, internal cluster communication, therefore, also has two primary objectives: on the one hand, to strengthen the exchange of information and engagement in the cluster and, on the other hand, to transmit and disseminate a common, appropriate identity and vision in order to strengthen the intra-cluster community. Due to the high overlap of characteristics of clusters and companies, we assume the six determinants of organizational success understanding, employee participation, trust, commitment, identification with the organization and motivation, which are positively influenced by good internal communication, in the applied form understanding, cluster members' participation, trust, commitment, identification with the cluster, and motivation, as determinants of success for cluster development, successful and goal-directed cluster operation, and a sustainable establishment of clusters (see Figure 2).

At this point, we would like to introduce the term “Effective internal Cluster Communication” and define it as “The communication within a cluster, between the cluster management and the cluster members, which enables the process of clear, distinct, purposeful and successful exchange of ideas, thoughts, opinions, knowledge and data within the cluster.”

Place leader and a shared vision as a liaison in an ambivalent environment

In most cases, leadership is referred to as an individual “who makes it happen”. In the literature, names such as for example champions, policy entrepreneurs, change agents, social innovators or transformative leaders are commonly used (Westley et al., 2013). Leadership is considered an individual capacity to order others what to do, based on strong hierarchical relations in decision-making and formal power.

In the case of the leadership of places and clusters, this is far more complex. We are in a system with multiple players, multiple stakeholders, multiple leaders and multiple, sometimes conflicting interests. Instead of a top-down management Place Leadership is often referred to as shared, cooperative or collaborative. It is described as multi-agency, multi-level and multi-faceted and shaped differently according to the frame conditions (Horlings et al., 2018). Place Leadership is defined as “the mobilization and coordination of diverse groups of actors to achieve a collective effort aimed at enhancing the development of a specific place” (Sotarauta, 2021, p. 152). It takes Place Leaders to successfully lead a place. A Place Leader is “an actor having a position to assess a path development process from a more comprehensive angle than the other actors, and mobilize and pool resources, competencies and powers” (Sotarauta et al., 2020, p. 96). Along with individuals from various sectors such as government, business, academia, and the community, also institutions and organizations as such can play the role of Place Leaders. Actually, this happens quite often in shaping the development and growth of a particular place. For example, a chamber of commerce, local economic development agency, or nonprofit organization can take a leadership role by advocating for policies and investments that support the development of the place they serve, fostering collaboration and partnerships among stakeholders, and supporting a shared vision for the place's future. Place Leaders gain influence by stimulating imagination, (re)framing issues, and developing new agendas, helping to “think the unthinkable” (Horlings et al., 2010). In this way, Place Leaders influence activities over which they often have little formal authority but which can strongly influence regional development (Sotarauta and Suvinen, 2019). Effective Place Leaders gain their influence through their ability to influence other stakeholders who hold formal power (Beer et al., 2019). Place Leaders are thus doing much more than mere managing—they truly lead a place.

Place Leaders are usually referred to as leaders, not by their position, but leaders by their personality. Leaders are people whom many people follow because they trust them. They do not follow a leader they cannot trust. Trust is an influential tool that increases reliability and integrity and provides an additional advantage in the face of uncertainty. Luthra and Dahiya (2015) even claimed that trust cannot be built; it can only be gained or earned. A trusting relationship between stakeholders and Place Leadership is what allows a place to be led in the first place. Rather than trying to convince all stakeholders of the one “right and true” view, leaders work to create a shared vision, common goals, and a shared strategy for the place across all stakeholders. A shared vision is defined as the organizational values that are the foundation for the active participation of all members of the organization (network) in the development, communication, dissemination, and implementation of organizational goals, and stands in contrast to the traditional top-down approach (Wang and Rafiq, 2009). They act as a kind of nexus between the different stakeholders (Horlings et al., 2018) and try to strengthen the sense of place and thus identification to better develop the place through joint actions. A shared vision represents the extent to which network members share a common understanding and perspective on how to achieve the network's activities and outcomes results. Shared goals, vision, and identity mean that network actors have similar perceptions of how they act with others. In this context, the exchange of ideas and resources, as well as knowledge transfer, can be promoted (Inkpen and Tsang, 2005).

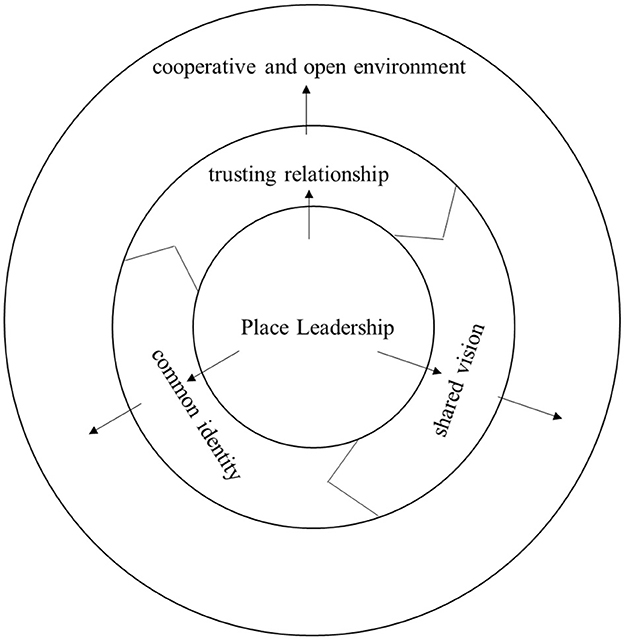

The leadership and management of clusters are similar to the leadership of places. As with Place Leadership, cluster management operates in an ambivalent environment of cooperation and competition. Moreover, cluster leadership per se also does not have the authority to order a company or institution what to do. Rather, both forms of leadership are based on mobilizing existing potentials and coordinating and harmonizing a multitude of interests to foster knowledge and technology transfer, exploit synergy effects and thus create added value and generate wealth. To accomplish this objective, cluster managers need the leadership personality of a Place Leader. As leaders, Place Leaders succeed in creating a collaborative and open environment by fostering a trusting relationship with local stakeholders (or cluster members) and the creation of a shared vision and resulting common identity for the place (or cluster) (see Figure 3). Place Leaders succeed in having cluster companies identify themselves simultaneously in two senses. On the one hand, with their personal identification as an independent company, and, on the other hand, with their social identity as part of the cluster. The dual identification induced can lead to a state where both identities are equally recognized and promoted (Hornsey and Hogg, 2000). We, therefore, argue that Place Leaders, through their leadership competencies, are better able to face the challenges of the multi-layered and partly competitive environment prevailing in a cluster than a cluster management that is not a Place Leader and lacks this leadership personality for a successful bottom-up approach. In our view, cluster management consisting of Place Leaders is critical to the success of cluster development.

Effective place leader cluster communication

Derived from our previously introduced understanding and presentation, we want to define Effective Place Leader Cluster Communication (EPLCC) as

The communication within a cluster, between the Place Leader, the cluster management and the cluster members, which enables the process of clear, distinct, purposeful and successful exchange of ideas, thoughts, opinions, knowledge and data within the cooperative and open cluster environment created by the Place Leader's personality, to develop understanding, cluster members' participation, trust, commitment, identification with the cluster and motivation, thereby influencing the success of the cluster.

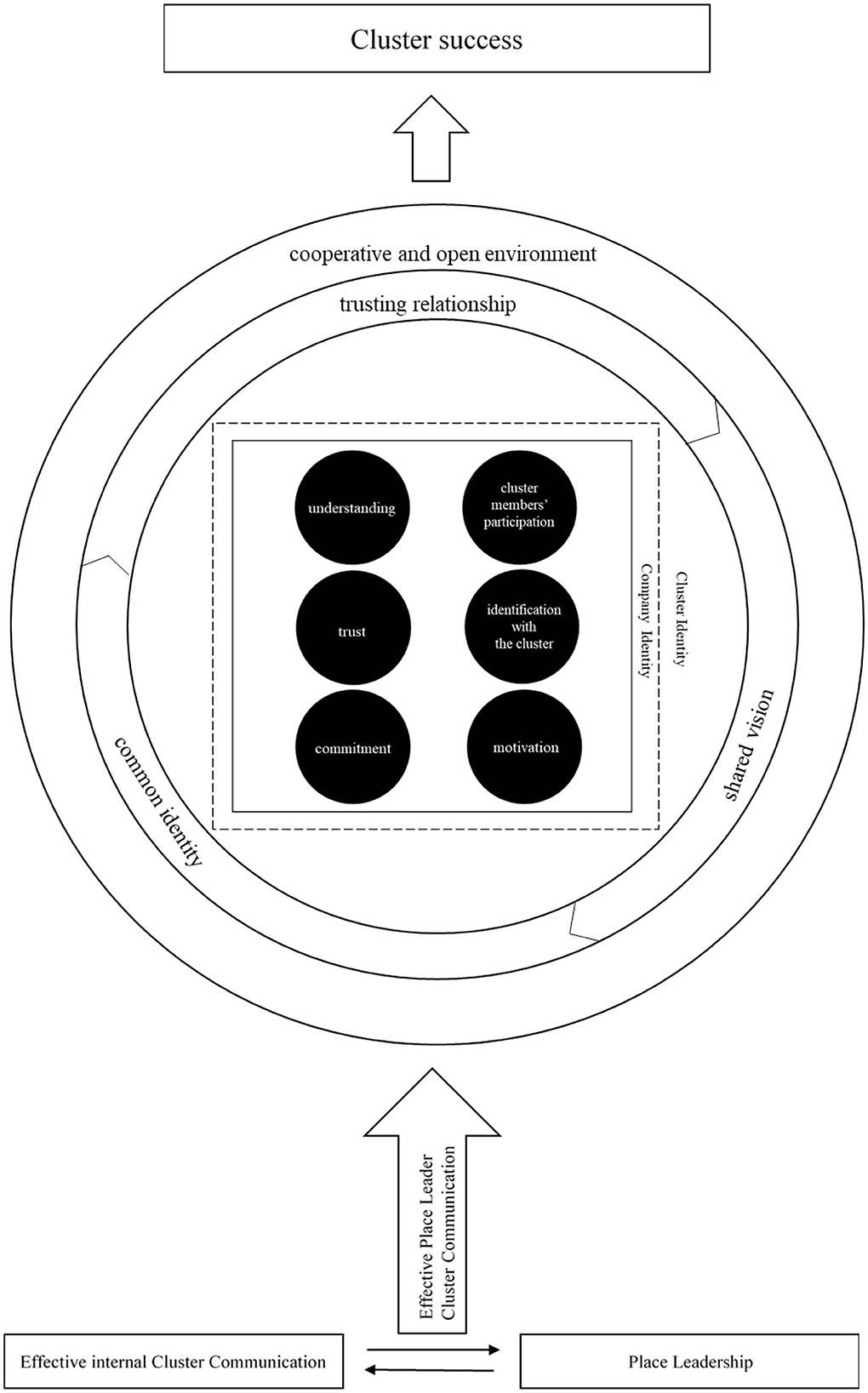

Through their leadership personality, a Place Leader-led cluster management succeeds in creating an open and cooperative environment of collaboration within the cluster. As key personalities, they create a trusting relationship with the cluster members and support establishing a shared vision for the cluster and, as a result, a shared cluster identity. A cluster management led by Place Leaders achieves that cluster members find the necessary framework to open up, are willing to cooperate, conflicts of interest can be eliminated, and the different agendas of the cluster members can be merged into common goals and collective actions. However, for this to happen, in addition to the leadership of the cluster management, clear, distinct, and purposeful communication is needed within the cluster, between the cluster members and the cluster management. Effective internal Cluster Communication is closely related to and interacts with Place Leadership. Only through Effective Place Leader Cluster Communication (EPLCC), can a cluster be sustainably developed and established through successful and targeted cluster work.

Effective Place Leader Cluster Communication affects the success of a cluster via various determinants that correlate with each other and are, in part, mutually dependent. In contrast to numerous other organizational forms with hierarchical structures and the top-down management usually associated with them, cluster membership is based on naturally established, voluntary and constructive interaction and cooperation. Cluster membership must be associated with added value for the companies and institutions. However, this added value can only be generated if it is possible to bring together a large number of sometimes competing actors, establish a trusting and open network, incorporate different cultures and harmonize institutional agendas. For this reason, Effective Place Leader Cluster Communication addresses two primary goals: on the one hand, communication within the cluster should strengthen information exchange and engagement within the cluster, and on the other hand, it should strengthen the cluster community, the “We-feeling.” Both objectives are particularly important in the cluster context in order to move from competing companies to cooperating companies on a voluntary basis that is characteristic of the cluster, thus making the cluster successful and in turn, generating the surplus value of cluster membership.

For this reason, Effective Place Leader Cluster Communication addresses not only the social (cluster) identity but also the personal identity of cluster companies, thus taking into account the sometimes competing interests of cluster members. Through their leadership competencies (pure management is not enough here), Place Leaders allow cluster companies not to abandon either identity but to live out both simultaneously. For if people are encouraged to give up their personal identity in favor of a superior group identity, they may perceive the undermining of their personal identity as a threat, which then leads to efforts to clearly distinguish and distance themselves from the “superior” group (Prasch et al., 2022).

Effective Place Leader Cluster Communication causes cluster members to develop an understanding of why joining a cluster can potentially add value to them, why there is a need for cooperation, and why they need to develop their own goals within the framework of the cluster to achieve the holistic cluster objective. Understanding the competitive framework and the potential added value of cluster membership paves the way for willingness to engage in a cluster. If the need to act and cooperate is recognized, involving cluster members in cluster management decision-making processes helps members pursue the cluster strategy more convincingly, become more committed to the cluster, become more engaged, and thus actively participate in the cluster's success. Involving cluster members in internal cluster decision-making processes also leads to increased trust in the cluster management, the cluster strategy and the cluster as a whole. Only when the cluster members trust the management and one another are they willing to open up and cooperate. Over time, trust also leads to commitment to the cluster, which is accompanied by identification with the cluster. The individual cluster members increasingly break out of their silo thinking and think in a more networked way which has a strong impact on initially competing companies follow then common goals and values and become more and more committed to the cluster idea as such. A common identity leads to an increase in motivation to become increasingly involved in the cluster and to continue to pursue the cluster objective in order to achieve the common cluster vision, even in the face of possible difficulties.

It is important to note that the individual success determinants are not to be understood in hierarchical order, but rather are mutually dependent and complementary. A genuinely Effective Place Leader Cluster Communication has the effect of stimulating all six success-defining factors. However, this requires an open and cooperative cluster environment, which is why cluster management should not be designed as a top-down system but should pursue a bottom-up approach utilizing Place Leadership, as shown in Figure 4.

Discussion

The Effective Place Leader Cluster Communication (EPLCC) model builds on the premise that clusters and organizations share some common characteristics such as the existence of goals, strategies, and values; management of activities and planning of future actions; and the need for communication. We hypothesize that, at their heart, the communication of clusters and organizations share similar goals and, therefore, have similar core functions and elements. Based on these shared characteristics, we apply the six organizational success determinants understanding, employee participation, trust, commitment, identification with the organization and motivation, which are positively influenced by good internal communication, to the cluster context. In doing so, we define understanding, cluster members' participation, trust, commitment, identification with the cluster, and motivation, as determinants of success for cluster development, successful and goal-directed cluster operation, and a sustainable establishment of clusters. While these assumptions are plausible (they follow a logical consistency and are consistent with existing knowledge), it is important to note that the plausibility of a model based on assumptions and theoretical considerations alone is not sufficient to prove its correctness. For this reason, the Effective Place Leader Cluster Communication model should be validated through systematic and rigorous empirical testing.

The EPLCC model shows the crucial role that Effective internal Cluster Communication plays in cluster development and the success factors that shape it. However, the model does not show which concrete communication tools and channels are used to promote the six mutually dependent and complementary success factors of understanding, cluster members' participation, trust, commitment, identification with the cluster, and motivation. The model provides a theoretical framework that explains why Effective Place Leader Cluster Communication is critical to cluster success, but it does not go into detail about how to practically implement that communication. Further investigation or study would be required to determine the specific communication tools and channels used to promote the aforementioned success factors. This could include, for example, qualitative interviews or surveys of members of successful Place Leader-led clusters to gain insight into their actual communication practices. This way, it would be possible to identify which specific means of communication, such as meetings, digital platforms, information sessions, or face-to-face conversations, are most effective in promoting understanding, cluster members' participation, trust, commitment, identification with the cluster, and motivation among cluster members. Identifying suitable communication tools and channels tailored to the specific requirements and needs of the cluster is an essential step in putting the theoretical insights of the EPLCC model into practice, thus effectively promoting cluster development.

Conclusion

Communication is key to the success of organizations as a system of individuals working together toward common objectives. In the context of cluster management, communication within the cluster, especially between the cluster leadership and the multitude of cluster members, plays a particularly important role in successful and effective cluster development. Clusters typically operate in a regional context characterized by multi-agents, multi-objectives, multi-visions, and pluralistic processes, methods, and goals. With the multitude of actors involved in a cluster, it is often a major challenge to balance the different cultures and institutional agendas and find common ground and mutual benefit. The decision to share initiatives in the field of technical and technological innovation with the other actors in the area is not a foregone conclusion. Due to sometimes converging expectations, values, and interests, obstacles such as mistrust, lack of interest, or unwillingness to cooperate can arise.

By conceptualizing Effective internal Cluster Communication and Place Leadership as determinants of successful cluster development, we show in this article that Effective Place Leader Cluster Communication enables clusters to find common, cooperative, and collaborative ways of working together. In the manner of the Dual Identity Theory, it is important to address and maintain both the personal and the social identity of the cluster members. We define Effective Place Leader Cluster Communication (EPLCC) as “The communication within a cluster, between the Place Leader, the cluster management and the cluster members, which enables the process of clear, distinct, purposeful and successful exchange of ideas, thoughts, opinions, knowledge and data within the cooperative and open cluster environment created by the Place Leader's personality, to develop understanding, cluster members' participation, trust, commitment, identification with the cluster and motivation, thereby influencing the success of the cluster.” Effective Place Leader Cluster Communication is a central element for cluster development, for successful and targeted cluster work, and for the sustainable establishment of the cluster.

With our article, we contribute to further research and understanding of how clusters work. There is a large body of cluster literature, but little attention has been paid to communication in clusters. This paper demonstrates the critical role that successful intra-cluster communication plays in cluster development. By applying the existing organizational communication literature to the cluster context and using the Place Leadership literature to conceptualize collaborative cluster management, as well as drawing on the insights of the Dual Identity Theory, we extend the existing literature with the model of Effective Place Leader Cluster Communication (EPLCC). The article offers numerous points of reference for further research in cluster communication and cluster leadership, establishment, and management.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

PG: initial idea. C-CC: supervision. PG and C-CC: writing and editing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abraham, M., Crawford, J., and Fisher, T. (1999). Key factors predicting effectiveness of cultural change and improved productivity in implementing total quality management. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 16, 112–132. doi: 10.1108/02656719910239910

Allen, M. W. (1992). Communication and organizational commitment: perceived organizational support as a mediating factor. Commun. Q. 40, 357–367. doi: 10.1080/01463379209369852

Appelbaum, S. H., Louis, D., Makarenko, D., Saluja, J., Meleshko, O., Kulbashian, S., et al. (2013). Participation in decision making: a case study of job satisfaction and commitment (part three). Ind. Commer. Train. 45, 412–419. doi: 10.1108/ICT-09-2012-0049

Asif, S., and Sargeant, A. (2000). Modelling internal communications in the financial services sector. Eur. J. Mark. 34, 299–318. doi: 10.1108/03090560010311867

Barrett, D. J. (2002). Change communication: using strategic employee communication to facilitate major change. Corp. Commun. 7, 219–231. doi: 10.1108/13563280210449804

Barrett, D. J. (2006). “Leadership communication: a communication approach for senior-level managers,” in Handbook of Business Strategy, ed. P. Coate (Bradford: Emerald Group Publishing Limited), 385–390. doi: 10.1108/10775730610619124

Beer, A., Ayres, S., Clower, T., Faller, F., Sancino, A., Sotarauta, M., et al. (2019). Place leadership and regional economic development: a framework for cross-regional analysis. Reg. Stud. 53, 171–182. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2018.1447662

Blassini, B., Dang, R. J., Minshall, T., and Mortara, L. (2013). “The role of communication in innovation clusters,” in Strategy and Communication for Innovation, eds N. Pfeffermann, T. Minshall, and L. Mortara (Berlin-Heidelberg: Springer), 119–137. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-41479-4_8

Blazenaite, A. (2011). Effective organizational communication: in search of a system. Soc. Sci. 74, 84–101. doi: 10.5755/j01.ss.74.4.1038

Bonache, J. (2005). Job satisfaction among expatriates, repatriates and domestic employees. The perceived impact of international assignments on work-related variables. Pers. Rev. 34, 110–124. doi: 10.1108/00483480510571905

Borgulya, Á., Balogh, G., and Jarjabka, Á. (2022). Communication management in industrial clusters: an attempt to capture its contribution to the cluster's success. J. East Eur. Manag. Stud. 27, 179–209. doi: 10.5771/0949-6181-2022-2-179

Boyatzis, R. E., Rochford, K., and Taylor, S. N. (2015). The role of the positive emotional attractor in vision and shared vision: toward effective leadership, relationships, and engagement. Front. Psychol. 6, 670. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00670

Burfitt, A., and Macneill, S. (2008). The challenges of pursuing cluster policy in the congested state. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 32, 492–505. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2427.2008.00784.x

Cheney, G. (1983). The rhetoric of identification and the study of organizational communication. Q. J. Speech 69, 143–158. doi: 10.1080/00335638309383643

de Ridder, J. A. (2004). Organisational communication and supportive employees. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 14, 20–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-8583.2004.tb00124.x

Eisenberg, E. M., Goodall, H. L Jr, and Trethewey, A. (2009). Organizational Communication. Balancing Creativity and Constraint. Boston, NY: Bedford/St. Martin's

Eisenberg, E. M., and Riley, P. (1988). “Organizational symbols and sense-making,” in Handbook of Organizational Communication, eds G. M. Goldhaber, and G. A. Barnett (Norwood, NJ: Ablex), 131–150.

Fisher, R., Ury, W., and Patton, B. (2011). Getting to Yes: Negotiating Agreement Without Giving In. New York, NY: Penguin Books.

Frese, M., Beimel, S., and Schoenborn, S. (2003). Action training for charismatic leadership: two evaluations of studies of a commercial training module on inspirational communication of a vision. Pers. Psychol. 56, 671–697. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2003.tb00754.x

Ganske, P., and Carbon, C.-C. (2023). Re-thinking cluster policies: the role of shared vision and Place Leadership on the development of resilient clusters. Leadersh. Educ. Pers. Interdiscipl. J. 4, 1–6. doi: 10.1365/s42681-023-00032-9

Gilley, A. M., Gilley, J. W., and McMillan, H. S. (2009). Organizational change: motivation, communication, and leadership effectiveness. Perform. Improv. Q. 21, 75–94. doi: 10.1002/piq.20039

Glew, D. J., O'Leary-Kelly, A. M., Griffin, R. W., and van Fleet, D. D. (1995). Participation in organizations: a preview of the issues and proposed framework for future analysis. J. Manage. 21, 395–421. doi: 10.1177/014920639502100302

Goldhaber, G. M., Porter, D. T., Yates, M. P., and Lesniak, R. (1978). Organizational communication: 1978. Hum. Commun. Res. 5, 76–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2958.1978.tb00624.x

Gordon, I. R., and McCann, P. (2000). Industrial clusters: complexes, agglomeration and/or social networks? Urban Stud. 37, 513–532. doi: 10.1080/0042098002096

Griffin, M. A., Parker, S. K., and Mason, C. M. (2010). Leader vision and the development of adaptive and proactive performance: a longitudinal study. J. Appl. Psychol. 95, 174–182. doi: 10.1037/a0017263

Hartmann, B. (2016). Kommunikationsmanagement von Clusterorganisationen. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien. doi: 10.1007/978-3-658-11111-3

Heller, F., Drenth, P., and Rus, V. (1988). Decision in Organizations: A Three Country Comperative Study. London: SAGE.

Hogg, M. A., and Terry, D. J. (2000). Social identity and self-categorization processes in organizational contexts. Acad. Manag. Rev. 25, 121–140. doi: 10.2307/259266

Horlings, L., Ostaaijen, J. J. C., and Stoep, H. (2010). Vital Coalitions, Vital Regions; Cooperation in Sustainable, Regional Development. Wageningen: Wageningen Academic Publishers. doi: 10.3920/978-90-8686-695-3

Horlings, L., Roep, D., and Wellbrock, W. (2018). The role of leadership in place-based development and building institutional arrangements. Local Econ. 33, 245–268. doi: 10.1177/0269094218763050

Hornsey, M. J., and Hogg, M. A. (2000). Assimilation and diversity: an integrative model of subgroup relations. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 4, 143–156. doi: 10.1207/S15327957PSPR0402_03

Husain, Z. (2013). Effective communication brings successful organizational change. Bus. Manag. Rev. 3, 43−50.

Huselid, M. A. (1995). The impact of human resource management practices on turnover, productivity, and corporate financial performance. Acad. Manag. J. 38, 635–672. doi: 10.2307/256741

Hyo-Sook, K. (2005). Organizational Structure and Internal Communication as Antecedents of Employee -Organizational Relationships in the Context of Organizational Justice: A Multilevel Analysis [PhD dissertation; department of communication]. College Park, MD, University of Maryland.

Inkpen, A. C., and Tsang, E. W. K. (2005). Social capital, networks, and knowledge transfer. Acad. Manag. Rev. 30, 146–165. doi: 10.5465/amr.2005.15281445

Jones, G. R., and George, J. M. (1998). The experience and evolution of trust: implications for cooperation and teamwork. Acad. Manag. Rev. 23, 531–546. doi: 10.2307/259293

Konovsky, M., Folger, R., and Cropanzano, R. (1987). Relative effects of procedural and distributive justice on employee attitudes. Represent. Res. Soc. Psychol. 17, 15–24.

Kouzes, J. M., and Posner, B. Z. (1993). Credibility: How Leaders Gain and Lose it, Why People Demand it. San Francisco: Jossey-Bss Publishers.

Kulachai, W., Narkwatchara, P., Siripool, P., and Vilailert, K. (2018). “Internal communication, employee participation, job satisfaction, and employee performance,” in Proceedings of the 15th International Symposium on Management (INSYMA 2018), 2018/03 (Amsterdam: Atlantis Press), 124–128. doi: 10.2991/insyma-18.2018.31

Larwood, L., Falbe, C. M., Kriger, M. P., and Miesing, P. (1995). Structure and meaning of organizational vision. Acad. Manag. J. 38, 740–769. doi: 10.2307/256744

Lewin, K. (1948). Resolving Social Conflicts: Selected Papers on Group Dynamics. New York, NY: Harper and Row.

Lundberg, C. C., and Brownell, J. (1993). The implications of organizational learning for organizational communication: a review and reformulation. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 1, 29–53. doi: 10.1108/eb028782

Luthra, A., and Dahiya, R. (2015). Effective leadership is all about communicating effectively: connecting leadership and communication. Int. J. Manag. Bus. Stud. 5, 43–48.

Mayer, R. C., Davis, J. H., and Schoorman, F. D. (1995). An integrative model of organizational trust. Acad. Manag. Rev. 20, 709–734. doi: 10.2307/258792

Menzel, M.-P., and Fornahl, D. (2005). Unternehmensgründungen und regionale Cluster: Ein Stufenmodell mit quantitativen, qualitativen und systemischen Faktoren. Z. Wirtschgeogr. 49, 131–149. doi: 10.1515/zfw-2005-0002

Pacanowsky, M. E., and O'Donnell-Trujillo, N. (1982). Communication and organizational cultures. West. J. Speech Commun. 46, 115–130. doi: 10.1080/10570318209374072

Parker, S. K., Chmiel, N., and Wall, T. D. (1997). Work characteristics and employee well-being within a context of strategic downsizing. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2, 289–303. doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.2.4.289

Pascale, R. T. (1984). Perspectives on strategy: the real story behind Honda's success. Calif. Manage. Rev. 26, 47–72. doi: 10.2307/41165080

Porter, M. E. (2000a). “Locations, clusters and company strategy,” in The Oxford Handbook of Economic Geography, eds G. L. Clark, M. P. Feldman, and M. S. Gertler (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 253–274.

Porter, M. E. (2000b). Location, competition, and economic development: local clusters in a global economy. Econ. Dev. Q. 14, 15–34. doi: 10.1177/089124240001400105

Postmes, T., Tanis, M., and Wit, B. (2001). Communication and commitment in organizations: a social identity approach. Group Process. Intergr. Relat. 4, 227–246. doi: 10.1177/1368430201004003004

Prasch, J. E., Neelim, A., Carbon, C.-C., Schoormans, J. P. L., and Blijlevens, J. (2022). An application of the dual identity model and active categorization to increase intercultural closeness. Front. Psychol. 13, 705858. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.705858

Roberts, K. H., O'Reilly, C. A., Bretton, G. E., and Porter, L. W. (1974). Organizational theory and organizational communication: a communication failure? Hum. Relat. 27, 501–524. doi: 10.1177/001872677402700507

Rosenfeld, S. A. (1996). Does cooperation enhance competitiveness? Assessing the impacts of inter-firm collaboration. Res. Policy 25, 247–263. doi: 10.1016/0048-7333(95)00835-7

Rosenfeld, S. A. (2002). Creating Smart Systems A Guide to Cluster Strategies in Less Favoured Regions. Carrboro, NC: Regional Technology Strategies.

Schnake, M. (2007). An integrative model of effort propensity. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 17, 274–289. doi: 10.1016/j.hrmr.2007.07.003

Sims, R. R. (2002). “Employee involvement is still the key to successfully managing change,” in Changing the Way We Manage Change, eds S. J. Sims, and R. R. Sims (Westport: Quorum Books), 33–54.

Smidts, A., Pruyn, A., and van Riel, C. (2001). The impact of employee communication and perceived external prestige on organizational identification. Acad. Manag. J. 49, 1051–1062. doi: 10.2307/3069448

Sotarauta, M. (2021). “Combinatorial power and place leadership,” in Handbook on City and Regional Leadership, eds M. Sotarauta, and A. Beer (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing), 152–166. doi: 10.4337/9781788979689.00018

Sotarauta, M., and Suvinen, N. (2019). Place leadership and the challenge of transformation: policy platforms and innovation ecosystems in promotion of green growth. Eur. Plan. Stud. 27, 1748–1767. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2019.1634006

Sotarauta, M., Suvinen, N., Jolly, S., and Hansen, T. (2020). The many roles of change agency in the game of green path development in the North. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 28, 92–110. doi: 10.1177/0969776420944995

Sparrow, P., and Cooper, C. L. (2003). The Employment Relationship: Key Challenges for HR. London: Routledge.

Tajfel, H., and Turner, J. C. (1979). “An integrative theory of intergroup conflict,” in The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations, eds W. G. Austin, and S. Worchel (Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole), 33–37.

Taylor, J. R., and Cooren, F. (1997). What makes communication ‘organizational'?: how the many voices of a collectivity become the one voice of an organization. J. Pragmat. 27, 409–438. doi: 10.1016/S0378-2166(96)00044-6

Tourish, D., and Hargie, O. (2004). Key Issues in Organizational Communication. London, NY: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203414958.pt2

Tucker, M. L., Meyer, G. D., and Westerman, J. W. (1996). Organizational communication: development of internal strategic competitive advantage. J. Bus. Commun. 33, 51–69. doi: 10.1177/002194369603300106

Wang, C., and Rafiq, M. (2009). Organizational diversity and shared vision: resolving the paradox of exploratory and exploitative learning. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 12, 86–101. doi: 10.1108/14601060910928184

Welch, M., and Jackson, P. R. (2007). Rethinking internal communication: a stakeholder approach. Corp. Commun. 12, 177–198. doi: 10.1108/13563280710744847

Westley, F. R., Tjornbo, O., Schultz, L., Olsson, P., Folke, C., Crona, B. I., et al. (2013). A theory of transformative agency in linked social-ecological systems. Ecol. Soc. 18, 27. doi: 10.5751/ES-05072-180327

Wolman, H., and Hincapie, D. (2014). Clusters and cluster-based development policy. Econ. Dev. Q. 29, 135–149. doi: 10.1177/0891242413517136

Keywords: organizational communication, cluster management, Place Leadership, entrepreneurship, openness, cooperation, shared vision, success factor

Citation: Ganske P and Carbon C-C (2023) Successful clusters through successful communication: why clusters should be managed by Place Leaders. Front. Commun. 8:1194103. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2023.1194103

Received: 26 March 2023; Accepted: 13 June 2023;

Published: 06 July 2023.

Edited by:

Ryan P. Fuller, California State University, Sacramento, United StatesReviewed by:

Andreia de Bem Machado, Federal University of Santa Catarina, BrazilTrygve Steiro, Nord University, Norway

Copyright © 2023 Ganske and Carbon. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Claus-Christian Carbon, Y2NjQHVuaS1iYW1iZXJnLmRl

Patricia Ganske

Patricia Ganske Claus-Christian Carbon

Claus-Christian Carbon