- 1Maternity and Child Health Nursing Department, College of Nursing, University of Hail, Hail, Saudi Arabia

- 2College of Nursing, Ateneo de Zamboanga University, Zamboanga, Philippines

Background: The healthcare system of Saudi Arabia has evolved radically into an institution that is adaptive to global change and is abreast with new advances in medical field to meet Saudi Vision 2030. The concept and practice of the dimensions of learning organization could provide a framework to significantly improve organizational performance. This study explores the practice of the seven dimensions of LO and determines their utilization toward enhanced performance at hospitals in Hail, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA). The findings of this study will help improve organizational (hospital) performance.

Method: This cross-sectional study included 117 nurse respondents from various government and private hospitals in the Hail region. Staff nurses were surveyed using the Dimensions of Learning Organization Questionnaire (DLOQ), and supervisors and managers were interviewed.

Results: Creation of continuous learning opportunities, team learning and collaboration, and strategic leadership in learning were perceived to be very satisfactorily utilized. Promotion of dialogue and inquiry, systems to capture and share learning, and empowerment and connection of the organization to the community were perceived to be satisfactorily utilized. Furthermore, the dimensions were found to be directly correlated, evidently signifying a strong relationship.

Conclusion: Overall, hospitals in the Hail region were found to be learning organizations. The dimensions of learning organization were utilized very satisfactorily, and the culture of learning was strongly embedded in the hospitals' systems and practices.

1. Introduction

The world is continuously subjected to numerous advancements, and organizations are constantly challenged to remain updated and compete with other organizations. Hospitals are not exempt from these pressures and are required to be consumer-oriented, interprofessional in healthcare approaches, and intensely focused on outcome measures for quality improvement (Soklaridis, 2013).

The healthcare system is considered a knowledge-based and knowledge-intensive organization. Hospitals are expected to foster innovation and positive cultural change to attract a wide clientele. They are required to be adaptive to societal changes and to keep abreast of new advances. A significant amount of knowledge and expertise among hospital staff is tantamount to providing excellent medical and nursing services to patients. The concept of a learning organization (LO) can provide a framework to address the everyday challenges that hospitals face and to improve organizational performance.

Human resources in hospitals play a crucial role in ensuring suitable resource (staff and facilities) distribution and placement to meet overall hospital goals and patient needs (Berns, 2021). There is intense competition among hospitals and other healthcare delivery institutions in terms of service quality, which motivates hospitals to develop innovative ideas and strategies. This is highly dependent on the hospital as an organization and whether it supports a learning culture. Hospitals are encouraged to nurture an environment that encourages learning among their employees, which may be a sustainable advantage over their competitors (Farrukh Muhammad, 2015; Makabila, 2017).

An LO fosters the continuous learning of its members, which generates innovation, work efficiency, a strong drive for lifelong learning, and a competitive advantage over other organizations. To become an LO, an organization must enthuse a kind of learning that not only generates new knowledge but also applies this knowledge for overall performance improvement (Aragon and Morales, 2023). LOs must value total employee involvement to attain organizational goals. LOs support learning at a rate equal to or greater than the extent of change around them. Change should serve as the force motivating employees to improve organizational performance through learning (Xuebao, 2022).

Yang et al. (2004) integrated various concepts, such as systems thinking, learning perspective, and strategic perspective (Senge and Sterman, 1992; Garvin, 1993; Yang et al., 2004). This integrative approach assimilates people and organizational structures to foster continuous learning and bring about organizational changes (Xuebao, 2022). The seven dimensions or imperatives in Watkins and Marsick's model are as follows: (a) creating continuous learning to make sure that the entire organization is geared toward learning innovative skills; (b) promoting dialogue and inquiry to remove barriers within the organization and advocate the capacity to listen and inquire into the views of others; (c) encourage collaboration and team learning by customizing the work to make use of groups to access different modes of thinking; (d) establish systems to capture, share, and support learning; (e) empower people toward a collective vision to motivate employees to learn more and be accountable for learning; (f) connect the organization to its community and environment but acknowledges its dependence on it environment; and (g) provide strategic leadership for learning, wherein leaders are expected to model learning and exhaust resources to support learning of all employees (Serrat, 2017). All seven dimensions are based on the interaction between people and systematic structures in the organization (Qawasmeh and Al-Omari, 2013).

Past studies have suggested that organizations that adopt LO strategies promote learning opportunities and practices at the individual, team, and organizational levels, which will result in improved organizational performance (Xuebao, 2022). Organizational performance depends on not only the comparative performance of an organization with respect to other organizations but also the excellence and progress it demonstrates over time. LO is considered an integral factor of competitiveness and has a strong link with organizational performance (Namada, 2018).

A study conducted in Thailand showed a strong connection between knowledge management and organizational performance. Several other studies reported similar findings (Abbasi and Zamani, 2013). A study on the impact of LO on the organizational performance of Saudi universities revealed that the universities practicing the dimensions of LO exhibited higher organizational performance (Abdulrahim et al., 2021). Another study conducted among 1,500 healthcare professionals demonstrated the paramount importance of embedding knowledge sharing in healthcare organizations to maintain a high level of learning during a public health crisis (Alonazi, 2021).

Despite the importance of practicing the dimensions of LO to enhance organizational performance, there are limited studies relevant to hospitals as learning organizations. Considering these factors, this study explores the practice of the seven dimensions of LO and determines their utilization toward enhanced performance at hospitals in Hail, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA). Furthermore, this study establishes the relationship among the dimensions of learning organization in enhancing the practice of LO. The findings of this study will help improve organizational (hospital) performance.

2. Methodology

2.1. Study design and participants

This study employed a cross-sectional approach to comprehensively explore the utilization of the seven dimensions of LO at hospitals in Hail, KSA. The research design helped obtain information on the current status of hospitals and described “what exists” in terms of the dimensions of LO. The study participants included nursing directors, nursing supervisors, head nurses, and staff nurses of three major government and two private hospitals in Hail, KSA. Convenience sampling was employed in this study where nurses participated with the following inclusion criteria; (a) working in the hospital for at least 6 months, (b) know how to write and speak in English, (c) willing to participate. Nurses were chosen primarily because nurses form the bulk of hospital personnel and are believed to spend the greatest number of hours in the hospitals and contact with patients. A total of 117 nurses participated in the online survey, which used a standardized questionnaire.

2.2. Data collection and study measures

The dimensions of the learning organization questionnaire (DLOQ) was used for the online survey of the hospital staff nurses. The DLOQ was developed by Yang et al. (2004). It measures the value of learning culture and explores the significant relationships between learning culture and organizational performance. The DLOQ has been studied extensively, with proven empirical results of acceptability and reliability estimates and a coefficient of alpha value ranging from 0.75 to 0.85. The questionnaire integrates both LO (continuous learning, systems connection, and embedded systems) and organizational learning process (dialogue and inquiry, team learning, empowerment, and strategic leadership). The seven aforementioned dimensions are both people-oriented and structure-oriented (Goula et al., 2020).

The authors validated the questionnaire in the local context, however, translation to Arabic was not done as majority of the participants understand English. The tool was then pilot tested to 15 staff nurses in a hospital not included in the study. The results yielded Cronbach alpha of 0.79, making the tool reliable.

Data collection commenced after the ethics board granted approval. All the six hospitals in Hail were chosen as locale of the study. The hospitals are under the Ministry of Health for a unified strategy on financing and expenditure, workforce and human resource development (Al Asmri et al., 2020). Data collection was assisted by the Continuing Nursing Education (CNE) units of the hospitals. Potential study participants with at least 6 months of service were identified and oriented to the study. Nurses were invited to participate in the study and an informed consent was signed as evidence of their voluntary and willingness to participate. The informed consent outlined the purpose and nature of study, the extent of their participation, confidentiality and voluntary clause and the right to withdraw from the study at any point. A Google link to the DLOQ was sent to the respondents. The data collection period was from November to December 2022.

2.3. Ethical consideration

This study was reviewed, approved and granted Ethics Clearance by the Local Committee for Bioethics Research in Hail Health (IRB-2022-66).

2.4. Statistical analysis

SPSS Version 26 was employed to statistically analyze the data. The mean and standard deviation were calculated to determine the variation from the average. Skewness and kurtosis were obtained to determine the symmetry or the lack of symmetry of the data sets, and whether the data were heavy-tailed or light-tailed compared to a normal distribution. Since the data was not normally distributed, Spearman's rho was used. A more robust non-parametric statistical treatment was deemed unnecessary in this study by the authors due to the fact that the study involved a relatively large number of participants and there were many paired ranks involved.

3. Results

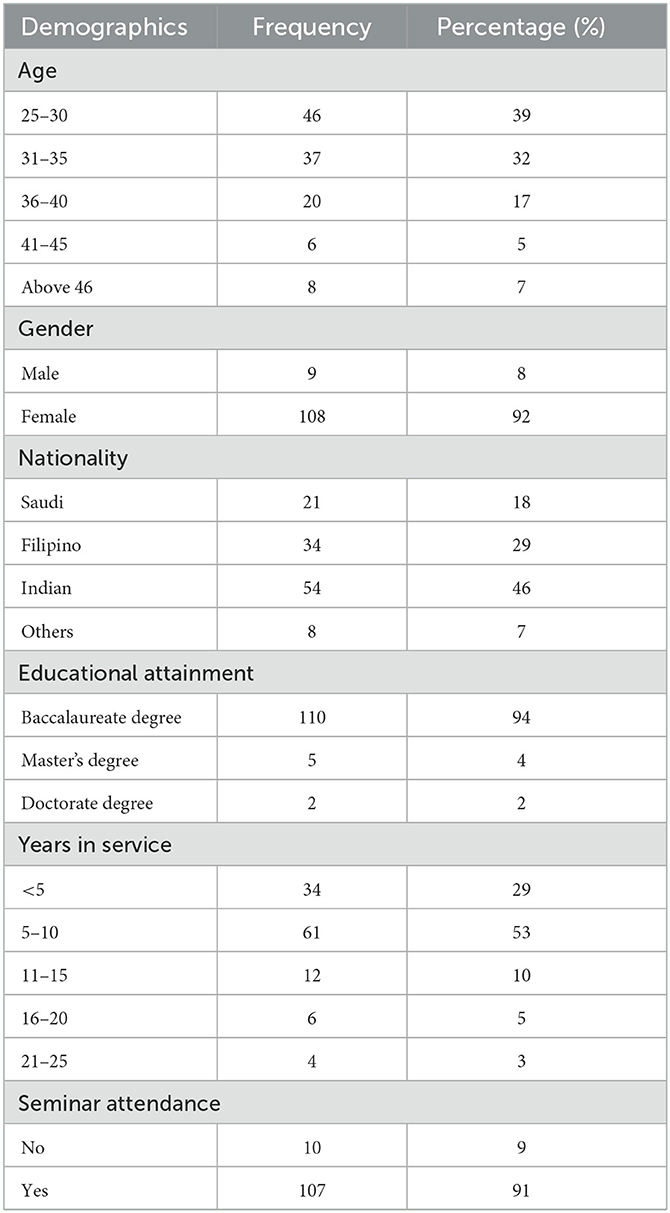

Table 1 presents the demographic profiles of the participants. The majority (39%) were within the 25–30 age group, with 92% (n = 108) of them being female. Most (46%; n = 54) of the participants were of Indian ethnicity. Remarkably, 94% (n = 110) of the nurses possessed a baccalaureate degree. More than half (53%) have been in service for ≤10 years and it is worth noting that 91% (n = 107) of the nurses have attended seminars and/or trainings on professional development.

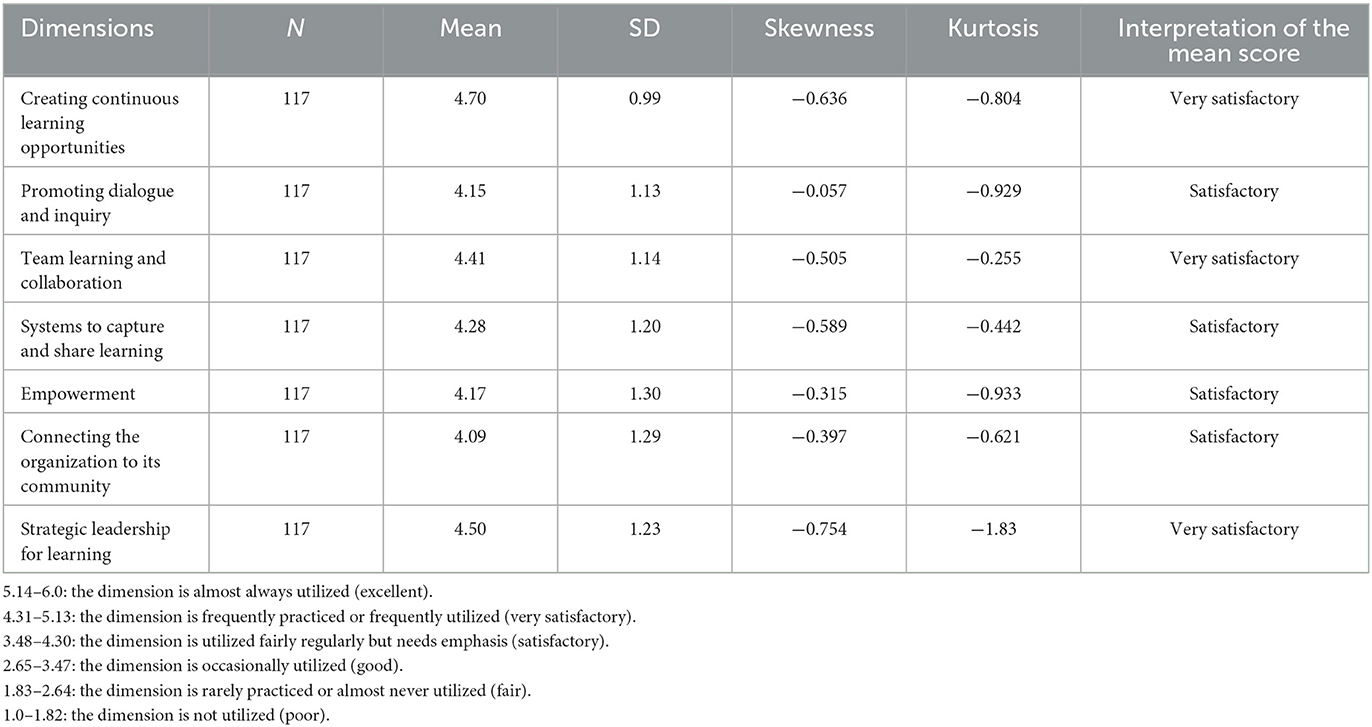

Table 2 presents the descriptive results of the seven dimensions of LO. Of note, “creating continuous learning opportunities” (4.70 ± 0.99), “team learning and collaboration” (4.41 ± 1.14), and “strategic leadership for learning” (4.50 ± 1.23) were found to be very satisfactory. Similarly, “promoting dialogue and inquiry” (4.15 ± 1.13), “systems to capture and share learning” (4.28 ± 1.20), “empowerment” (4.17 ± 1.30), and “connection to community and the environment” (4.09 ± 1.29) were found to be satisfactory.

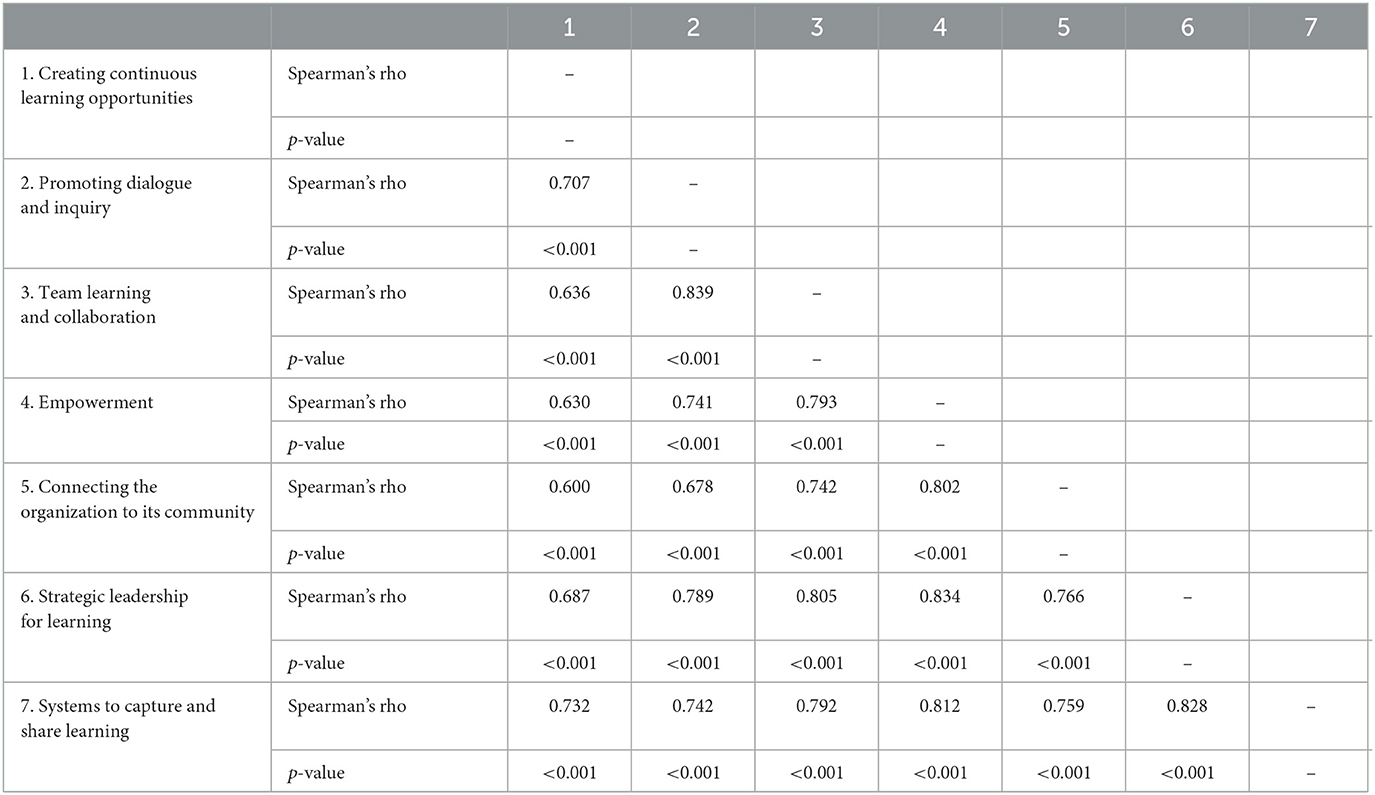

Table 3 presents the correlation between the dimensions of learning organization. The relationships were found to be significant at an alpha level of 0.01, which indicated a strong correlation between the dimensions of LO. Unmistakably, all seven dimensions, pairwise, were directly correlated, signifying a strong relationship. This was supported by a Spearman's rho value higher than 0.60. Generally, it is observed that when one dimension is evidently practiced, there is a strong tendency for the other dimensions to be equally utilized.

4. Discussion

This study determined the utilization of the dimensions of LO at hospitals in the Hail region to enhance organizational performance. The readiness of the healthcare workforce to undergo transformation should be considered a pivotal factor in coping with and adapting to changes. Saudi Arabia Ministry of Health (MOH) supports the changes in global health by developing and providing learning opportunities to staff to improve the quality of care and to achieve the goals of Saudi Vision 2030 and the National Transformation Program (NTP) (Anon, 2023).

In this study, hospitals' utilization of the dimension related to “creating continuous learning opportunities” was found to be very satisfactory. This suggests that hospitals are geared toward training nurses in learning new skills. The provision of learning opportunities are viewed to be frequently evident among hospitals. However, the responses of some of the participants indicated that the evidence of utilization was relatively occasional, if not fairly regular. In practice, the topics of educational activities in the annual plan were drafted after a thorough analysis of the learning needs assessments conducted among the nursing staff. This indicated that the learning needs of the staff were supported and that continuous learning was encouraged. According to Rahman and Malik (2021), the practice of continuous learning solidifies the employees' existing skills and helped them improve in lacking areas. Hospitals with effective training programs are able to identify individual areas of improvement and address them properly. This built the nurses' confidence, improved overall performance, and encouraged cooperation and creativity to bring new ideas to the workplace (Tine Health, 2023).

The dimension related to “promotion of dialogue and inquiry” was perceived to be satisfactory, which suggested that this dimension was practiced fairly regularly and that it needed emphasis. Dialogue and inquiry significantly boosted organizational efforts to create a culture of feedback, positive questioning, and experimentation, helped recognize staff concerns, perspectives, and experiences, broke down stereotypes, strengthened teams, and transformed ideas in beneficial ways. This corroborates the study among healthcare employees given the opportunity to express individual views and opinions related to work (Goula et al., 2020). It takes an astute leader to make the first move by creating programs and a physical work environment around these ideals, setting up the framework for an open dialogue culture to prevail naturally (Malik and Garg, 2017). According to a good number of respondents, the hospitals in Hail promoted dialogue and inquiry among the nurses. Nurse managers verbalized that staff nurses were given the opportunity to select educational activities through their participation in the learning needs assessment, one-on-one teaching, and open forums for the courses. The Continuing Education Units (CNE) of the hospitals encourage the use of interactive courses. Nurse leaders may advance a culture of inquiry by providing the infrastructure to support evidence-based activities, which include access to scientific articles and partnerships with nursing schools, and empowering nurses to question and seek answers to identified practice questions (Carter et al., 2018).

The dimension related to “team learning and collaboration” was found to be very satisfactory. Such a finding implies that patient care is the top priority in nursing. For patients to receive the best possible healthcare, nurses must be knowledgeable about the latest developments in nursing care. Safe patient care was facilitated through team learning and collaboration among those involved in patient care.

Organizational learning and team learning in healthcare are central to managing the learning requirements in a complex interconnected dynamic system, wherein all are encouraged to apply background knowledge, along with shared meta-knowledge of roles and responsibilities, to execute assigned functions, communicate and transfer the flow of pertinent information, and collectively provide safe patient care (Ratnapalan and Uleryk, 2014). A considerable number of participants mentioned that hospitals in Hail almost always utilized team learning and collaboration to perform their tasks. Based on the information gathered from the nurse managers, the CNE team was responsible for developing a plan for the nursing staff, nursing students, and interns at all affiliated hospitals, nursing colleges, and/or universities. There was also a clinical resource nurse responsible for implementing the nursing competency program (NCP), updating the online NCP database, assisting the nursing staff from other hospitals/institutions (cross-training) to become familiar with the new job requirements and working environment, and enhancing staff's knowledge and skills in advanced specific clinical competencies. This result differs substantially from findings of other studies (Leufvén et al., 2015; Kumar et al., 2016; Goula et al., 2020) showing lower scores for team learning and collaboration and further encouraged to achieve organization-wide learning.

The central role of healthcare organizations is to provide safe and effective health care. They are equally responsible for generating new knowledge and approaches to address complex issues and educating future generations of health professionals. All healthcare institutions recognize that learning as an organization is an essential function for managing and bringing about changes, especially in complex systems. Individual and team learning alone cannot produce the desired effect or stave off stagnation, which could threaten service excellence and patient safety (Ratnapalan and Uleryk, 2014).

In this study, the dimension related to “systems to capture and share learning” was found to be satisfactory. According to a sizable group of participants, this dimension was at the most occasionally utilized, while a subgroup viewed it to be at least frequently utilized or observed. Hospitals as learning organizations use technology systems for information dissemination within and outside the organization. Information and communication technologies (ICT), such as telehealth and patient portals for electronic medical records, provide a great opportunity for hospitals to efficiently and effectively manage healthcare service delivery. Despite the challenge to ease of use, these systems were created and integrated in the hospital workflow. Access to these systems must be provided to all employees to bring about a positive impact on patient outcomes and fast interaction with other members of the healthcare team, as well as to ensure data security and resourcing (Alexander et al., 2021).

Top-level managers of the hospitals verbalized that information and communications systems were established to speed up collaborative work and improve the safety of healthcare delivery and the quality of work to be on par with other globally recognized healthcare institutions. This has greatly reduced unnecessary delays and lowered administrative costs on a long-term basis. Nurses expressed appreciation for advanced technology in patient care. Nurses were trained to be familiar with technology use for patient care and the hospital system for easy and convenient communication. Systems to capture and share learning in hospitals have enabled personnel to easily obtain the required information and maintain a database of employee skills. Additionally, such systems have allowed hospitals to measure the gaps between current and expected performance, as well as the time and resources spent on personnel development. Saudi Arabia has undergone intense dynamic development in the past several years with the government's Vision 2030, which has paved the way for massive improvements in the quality of healthcare and patient safety (Alatawi et al., 2022). However, the result runs contrary to findings of other studies (Alatawi et al., 2022; Tebitendwa and Ssebagala, 2022) showing the organizations' disconnect from the environment.

The dimension related to “empowerment” was found to be satisfactory. A considerable number of participants believed that empowerment was utilized only occasionally. In a learning organization, such as a hospital, top management was encouraged to empower staff to realize the organization's vision. The employees were involved in setting, owning, and implementing a joint vision. Hospital management empowered their employees by distributing work responsibilities among them and decentralizing decision making. By doing so, employees were motivated to learn more and become accountable for learning (Tebitendwa and Ssebagala, 2022). The results proved that the dimension related to “empowerment” is a potential area for improvement. Responses from participants showed that a slightly low score on this dimension was probably related to the organization's inherent hierarchical structure, especially for hospitals where the employees have provisional rights and access to certain information and limited authority to take risks and make decisions, which leave very little initiative for the employees to learn or innovate (Leufvén et al., 2015). The relatively low score on empowerment contradicts the findings (Kumar et al., 2016) of a study where empowerment scored high and presumed to be due to the bureaucratic structure in most healthcare organizations.

Hospitals, as learning organizations, connect to their communities and environments by maintaining harmonious relationships. Hospitals acknowledged their dependence on the environment, and the information they acquired from their environment was used to improve and sustain work practices (Alonazi, 2021). Like the other dimensions, the participants considered the dimension related to the “connection of the organization to the environment” to be utilized satisfactorily. The responses related to the hospitals' connection to their environment were limited to those who participated in different training programs with other agencies within Saudi Arabia. This perspective may depend on how hierarchical structures with rigid rules, standard procedures, and processes influence employees' perceptions of hospitals as learning organizations (Leufvén et al., 2015). Despite this perspective, past research has shown that hospitals in Saudi Arabia continue to improve their connections and relationships with the community by constantly improving systems and collaborating with other agencies (Alonazi, 2021). Goula et al. (2021) likewise stipulate that the internal and external environment of hospitals as well as the development of organizational programs are essential to succeed as learning organizations.

The results of this study yielded empirical evidence that the dimension related to “strategic leadership for learning” was perceived to be very satisfactory. Leaders of a learning organization immensely impact the entire organization by modeling learning and exhausting resources to support the learning of all employees. Hospital management embodies strategic leadership to foster learning and innovation. Nursing leaders in hospitals foster structured programs dedicated to enhancing and strengthening the clinical expertise of nurses through continuing nursing education units. Leaders asserted their commitment to improving the nursing workforce through continued learning opportunities. However, responses from staff nurses showed dissatisfaction in terms of available additional learning based on expertise. It was further observed that staff nurses were reluctant to elaborate on their dissatisfaction. This may be attributed to the high regard staff nurses confer upon their nursing leaders or the unwillingness to critique managers and leaders due to the hierarchical structure (Leufvén et al., 2015). Notably, this finding is incompatible with Goula et al. (2021) where leaders are not able to provide an environment nurturing a culture of learning within the organization. It is further advised for leaders to adapt transformational leadership and foster active communication among members of the organization (Santoso et al., 2022).

Overall, the dimensions of LO were found to be utilized very satisfactorily. A considerable number of nurses perceived the dimensions to be satisfactorily utilized. The results presented a favorable scenario for the healthcare system to improve organizational (hospital) performance. By and large, healthcare institutions in Saudi Arabia, including the Hail region, have experienced massive development in the last 15 years. The NTP, as part of the Saudi Vision 2030, aims to improve the quality of patient care (Young et al., 2021). In this regard, hospitals, like any other organization, aim to be learning organizations and enhance practices to help bolster the knowledge and skills of employees and provide appropriate opportunities to improve organizational performance (Alexander et al., 2021). Hospital leaders play a unique role in nurturing an intense commitment to learning and investing resources and time to incorporate learning into managerial strategies. Leaders reinforce organizational values by fostering an environment that allow the members of the organization to grow and develop through active involvement in goal setting, opportunities and recognition. Employee engagement is positively correlated to improved performance and greater job satisfaction (Tenney, 2023).

Organizational performance describes how much excellence and progress the organization demonstrates over time. Scholars view LO as a process of obtaining and using knowledge and as a basic criterion of competitiveness, which is strongly linked to organizational performance (Garvin, 1993). LO has a positive effect on the behavior of the members of the organization (Abbasi and Zamani, 2013). Other studies conducted in Taiwan and Pakistan also reported a positive correlation between LO and organizational performance (Lagura, 2019). A study conducted among healthcare organizations in the Al-Taif governorate also showed a statistically significant relationship between LO and organizational performance (Nafei, 2015). Another study found that the absence of a health LO may lead to ineffective hospital performance within a holistic healthcare system (Alonazi, 2021).

It can be construed that a hospital that embeds a learning culture in its organizational practices will improve the skills and knowledge of its employees to deliver quality services. Hospitals with a culture of continuous learning at all levels can facilitate improvements, thus making the organization more innovative. Well-connected systems in hospitals that are integrated with a learning culture will nurture cohesive working relationships within the organization and with the community and strengthen desirable healthcare practices. Leadership in healthcare can foster healthy dialogue and inquiry to correct confusing structures, procedures, and assumptions (Goula et al., 2020).

This study illustrated the value and usefulness of utilizing the dimensions of LO across all levels in hospitals as a basis for enhancing or improving organizational performance. Organizational practices must be consistently followed and evaluated regularly to continuously attract, retain, and motivate the best employees in the organization.

A pronounced strong relationship was observed between team learning and collaboration and each of the following dimensions: promotion of dialogue and inquiry and strategic leadership for learning. This result highlighted the role of leaders who systematically mentored and coached subordinates by promoting an environment of teamwork and collaboration, as well as nurturing positive feedback and open communication (Tebitendwa and Ssebagala, 2022). Similarly, hospital leaders fostered positive relationships in the implementation of strategies to achieve the organizational vision stressed by the nursing leaders. Likewise, a significantly strong relationship was evident between empowerment and the connection of the organization to its environment, strategic leadership for learning, and systems to capture and share learning. A strong relationship was also conspicuous between strategic leadership for learning and systems to capture and share learning, as well as team learning and collaboration. Also, the underlying relationship resulted in a very high tendency for one dimension's level of utilization to increase with the increase in the other dimensions' level of utilization. This study specifically showed a high tendency for hospitals to utilize the dimension related to “promotion of dialogue and inquiry” more often whenever “team learning and collaboration” was utilized more frequently. These findings are consistent with other studies stating that integrating learning into organizational functions leads to a positive effect on individual and organizational performance (Young et al., 2021). The same was stated in other studies (Nafei, 2015; Kyoungshin et al., 2017; Lagura, 2019). This is in view of the fact that hospital performance is by far a result of a concerted effort. Cultivating organizational performance is a continuous challenge as hospitals adopt positive strategies for it (Xiong et al., 2022).

5. Limitation

This study acknowledges its limitations. For instance, this study focused only on hospitals in the Hail Region of Saudi Arabia and included a specific sample of nurses. This restricts the generalizability of the findings to other regions or healthcare settings. The findings may not be applicable to hospitals in different contexts or countries. Moreover, the data collection relied on self-report measures, which can be subjected to response biases. Participants may have provided socially desirable responses or may not have accurately represented their true experiences and perceptions. This could affect the reliability and validity of the results.

This study relied solely on questionnaire-based data collection, which may have limit the depth of understanding and overlook important contextual factors. Employing additional methods, such as interviews or observations, could have provided richer insights into the utilization of LO dimensions in hospitals.

The study did not include a control group for comparison. Without a control group, it is challenging to determine whether the observed utilization of LO dimensions is unique to the hospitals in the Hail region or if it is consistent across different settings. A control group would have allowed for better comparisons and enhanced the study's internal validity. The questionnaire used in the study was developed and administered in English, and no information was provided regarding translation or validation in Arabic. This language limitation could introduce potential issues related to comprehension or interpretation of the questionnaire by the participants.

6. Conclusion

This study demonstrated that hospitals in the Hail region of KSA were learning organizations, as evidenced by their utilization of the dimensions of LO. Yang et al. (2004) seven dimensions were perceived to be utilized very satisfactorily, and these dimensions were found to exhibit strong correlations. The findings offer a promising scenario for the healthcare system because like any other organization, hospitals are geared toward adapting to the ever-changing environment. As LOs, hospitals in the Hail region can keep abreast of the dynamics of the healthcare sector. Furthermore, considering the increasing demand for accountability for quality care, patient satisfaction, and social responsibility, these hospitals, as LOs, can embrace best practices and quality improvement to enhance hospital performance.

This study recommends that hospitals pursue LO not only to improve organizational performance but also to develop a learning culture that increases employee job satisfaction and lowers turnover rates. Future studies may cover other variables that may be impacted by LO.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Local Committee for Bioethics Research in Hail Health (IRB-2022-66). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

GL: conceptualizing and writing—original draft. GL and MC: data curation. GL, MC, and NA: methodology and writing—review & editing. GL and NA: project administration and supervision. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This research has been funded by Deputy for Research and Innovation, Ministry of Education through Initiative of Institutional Funding at University of Ha'il – Saudi Arabia through project number IFP-22 116.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abbasi, E., and Zamani, N. (2013). The role of transformational leadership, organizational culture and organizational learning in improving the performance of Iranian agricultural faculties. High. Educ. 66, 505–519. doi: 10.1007/s10734-013-9618-8

Abdulrahim, M., Othayman, M., Boy, F., and Dinnedu, D. (2021). The Impact of Learning Organizations Dimensions on the Organisational Performance: An Exploring Study of Saudi Universitie. International BUsiness Research.

Al Asmri, M., Almalki, M. J., Fitzgerald, G., and Clarck, M. (2020). The public health care system and primary care services in Saudi Arabia: a system in transition. East Mediterr. Health J. 4, 26. doi: 10.26719/emhj.19.049

Alatawi, S., Olfat, S., and Zakari, N. (2022). Impact of learning organization's dimensions on saudi nurses' performance: a cross sectional study. Nurs. Prim. Care 6, 1–5. doi: 10.33425/2639-9474.1218

Alexander, K. A., Ogle, T., Hoberg, H., Linley, L., and Bradford, N. (2021). Patient preferences for using technology in communication about symptoms post hospital discharge. BMC Health Serv. Res. 21, 141. doi: 10.1186/s12913-021-06119-7

Alonazi, W. B. (2021). Building learning organizational culture during COVID-19 outbreak: a national study. BioMed Central. 21, 1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12913-021-06454-9

Anon (2023). Vision 2030. Available online at: https://www.vision2030.gov.sa/v2030/vrps/hstp/ (accessed January 13, 2023).

Aragon, C. L. M., and Morales, N. A. (2023). A systematic review of the organizational learning and performance literature. Rev. Cient. Vision Futuro 27, 24–39. doi: 10.36995/j.visiondefuturo.2023.27.01.001.en

Carter, E. J., Rivera, R. R., Gallagher, K. A., and Cato, K. D. (2018). Targeted interventions to advance a culture of inquiry at a large, multicampus hospital among nurses. J. Nurs. Adm. 48, 18–24. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0000000000000565

Farrukh Muhammad, W. A. (2015). Learning organization and competitive advantage - an integrative approach. J. Asian Bus. Strat. 5, 73–79. doi: 10.18488/journal.1006/2015.5.4/1006.4.73.79

Goula, A., Stamouli, M.-A., Latsou, D., Gkioka, V., and Sarris, M. (2020). Validation of dimensions of learning organization questionnaire (DLOQ) in health care setting in Greece. J. Public Health Res. 9, 517–522. doi: 10.4081/jphr.2020.1962

Goula, A., Stamouli, M. A., Latsou, D., Gkioka, V., and Kyriakidou, N. (2021). Learning organizational culture in Greek Public Hospitals. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 18, 1867. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18041867

Kumar, J. K., Gupta, R., Basavaraj, P., Singla, A., Prasad, M., Pandita, V., et al. (2016). An insight into health care setup in National capital region of India using dimensions of learning organizations questionnaire (DLOQ)- a cross-sectional study. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 10, 1–5. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2016/16186.7898

Kyoungshin, K., Watkins, K. E., and Lu, Z. L. (2017). The impact of a learning organization on performance: focusing on knowledge performance and financial performance. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 41, 177–193. doi: 10.1108/EJTD-01-2016-0003

Lagura, G. A. (2019). Dimensions of learning organization and the predictors to organizational performance among Universities in Zamboanga City. Int. J. Innovat. Creat. Change. 8.

Leufvén, M., Vitrakoti, R., Bergström, A., Ashish, K. C., and Målqvist, M. (2015). Dimensions of learning organizations questionnaire (DLOQ) in a low resource health care setting in Nepal. Health Res. Policy Syst. 13, 1–8. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-13-6

Makabila, G. I. M. W. A. (2017). Does organizational learning and competitive advantage? Int. J. Sci. Res. Publ. 7, 1–18.

Malik, P., and Garg, P. (2017). The relationship between learning culture, inquiry and dialogue, knowledge sharing structure and affective commitment to change. J. Org. Change Manag. 30. doi: 10.1108/JOCM-09-2016-0176

Nafei, W. A. (2015). Organizational learning and organizational performance: a correlation study in the kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Am. Int. J. Soc. Sci. 4, 191–208.

Namada, J. (2018). “Organizational learning and competitive advantage,” in Evaluation on Personal Leadership in Practice, ed U. S. I. University (Pennsylvania: IGI Global), 86–104.

Qawasmeh, F., and Al-Omari, Z. (2013). The learning organization dimensions and their impact on organizational performance: orange Jordan as a case study. Arab Econ. Bus. J. 8, 38–52. doi: 10.1016/j.aebj.2013.11.005

Rahman, A., and Malik, A. R. (2021). Relationship between training and development and employee performance: an analysis. Int. J. New Technol. Res. 7, 57–61. doi: 10.31871/IJNTR.7.2.12

Ratnapalan, S., and Uleryk, E. (2014). Organizational learning in health care organizations. Systems 2, 24–33. doi: 10.3390/systems2010024

Santoso, N. R., Sulistyaningtyas, I. D., and Pratama, B. P. (2022). Transformational Leadership during the COVID-19 pandemic: strengthening employee engagement through internal communication. J. Commun. Inq. 1–24. doi: 10.1177/01968599221095182

Senge, P. M., and Sterman, J. D. (1992). Systems thinking and organizational learning: acting locally and thinking globally in the organization of the future. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 59, 137–150. doi: 10.1016/0377-2217(92)90011-W

Serrat, O. (2017). “Dimensions of learning organization,” in Knowledge Solutions (Singapore: Springer), 865–870.

Soklaridis, S. (2013). Improving hospital care: are learning organizations the answer? Natl. Libr. Med. 28, 830–838. doi: 10.1108/JHOM-10-2013-0229

Tebitendwa, A., and Ssebagala, C. (2022). employee empowerment and employee performane in the public hospitals in Uganda. a case of Naguru Hospital. Acad. Lett. 5566. doi: 10.20935/AL5566

Tenney, M. (2023). Business Leadership Today. Available online at: https://businessleadershiptoday.com/what-is-the-value-of-employee-engagement/ (accessed May 2, 2023).

Tine Health (2023). How to Develop Effective Hospital Training and Development Programs. San Francisco, CA.

Xiong, C., Hu, T., Xia, Y., Cheng, J., and Chen, X. (2022). Growth culture and public hospital performance: the mediating effect of job satisfaction and person–organization fit. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19, 1–16. doi: 10.3390/ijerph191912185

Xuebao, X. D. K. D. (2022). A review of organization change management and employee performance. J. Xidian Univ. 6, 494–506. doi: 10.37896/jxu16.1/043

Yang, B., Watkins, K. E., and Marsick, V. J. (2004). The construct of the learning orgaization: dimensions, measurement and evaluation. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 15, 1–25. doi: 10.1002/hrdq.1086

Keywords: learning organization, dimensions of learning organization, hospital performance, Saudi nurses, DLOQ

Citation: Alrashidi NA, Lagura GAL and Celdran MCB (2023) Utilization of the dimensions of learning organization for enhanced hospital performance. Front. Commun. 8:1189234. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2023.1189234

Received: 18 March 2023; Accepted: 18 October 2023;

Published: 02 November 2023.

Edited by:

Janice McMillan, Edinburgh Napier University, United KingdomReviewed by:

Tosaporn Mahamud, Kasem Bundit University, ThailandLina Díaz-Castro, National Institute of Psychiatry Ramon de la Fuente Muñiz (INPRFM), Mexico

Oytun Sözüdoğru, University of City Island, Cyprus

Copyright © 2023 Alrashidi, Lagura and Celdran. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Grace Ann Lim Lagura, Zy5sYWd1cmFAdW9oLmVkdS5zYQ==; Z3JhY2Vhbm4xMTAyQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Nojoud Abdullah Alrashidi

Nojoud Abdullah Alrashidi Grace Ann Lim Lagura

Grace Ann Lim Lagura Ma Christina Bello Celdran

Ma Christina Bello Celdran