- 1Department of Family Medicine, Schulich School of Medicine and Dentistry, Western University, London, ON, Canada

- 2Faculty of Health Sciences, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, BC, Canada

- 3Faculty of Nursing, Memorial University, St. John's, NL, Canada

- 4Department of Family Medicine Primary Care Research Unit, Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS, Canada

- 5Doctors Nova Scotia, Dartmouth, NS, Canada

- 6Nova Scotia Health, Halifax, NS, Canada

- 7Thames Valley Family Health Team, London, ON, Canada

- 8St. Joseph's Health Care London, Family Medical Centre, London, ON, Canada

Introduction: Providing family physicians (FPs) with the information they need is crucial for their participation in a coordinated pandemic or health emergency response, and to allow them to effectively run their practices. Most pandemic planning documents do not address communication plans specific to FPs. This study describes FPs' experiences and challenges with information management during the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada.

Methods: We conducted semi-structured qualitative interviews with FPs across four Canadian regions and asked about their roles during different pandemic stages, as well as facilitators and barriers they experienced in performing these roles. We transcribed the interviews, used a thematic analysis approach to develop a unified coding template across the four regions, and identified recurring themes.

Results: We interviewed 68 FPs and identified two key themes specifically related to communication. The first is FPs' experiences obtaining and managing information during the COVID-19 pandemic. FPs were overwhelmed by the volume of information and had difficulty applying the information to their practices. The second is the specific attributes FPs need from the information sent to them. Participants wanted summarized and consistent information from credible sources that are relevant to primary care.

Discussion: Providing clear, collated, and relevant information to FPs is essential during pandemics and other health emergencies. Future pandemic plans should integrate strategies to deliver information to FPs that is tailored to primary care. Findings highlight the need for a coordinated communication strategy to effectively inform FPs in health emergencies.

1. Introduction

Public health guidelines for communicating to the public during an infectious disease outbreak emphasize the need for communication that is timely, accurate, credible, respectful, action-oriented, and shows empathy and cultural sensitivity (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; World Health Organization, 2008; Henry, 2018). Best practice recommendations for communications during a health crisis build on principles of ethics, collaboration, proportionality, evidence-informed decision-making (Henry, 2018), and theories of risk perception and tolerance (Inouye, 2014; Hyland-Wood et al., 2021; Ontario Hospital Association). Additionally, these guidelines highlight the need to build trust and cooperation by including mechanisms to engage and listen to communities and stakeholders (World Health Organization, 2008; Centers for Disease Control Prevention, 2018; Henry, 2018; Hyland-Wood et al., 2021), including primary care providers who play important roles in pandemic response (Mathews et al., 2023a,b).

Communication with primary care providers is key to an effective and coordinated response to pandemics and health emergencies. The need for communication plans and guidelines for information management [i.e., the compilation, organization, and dissemination of relevant information and guidelines (Jaeger et al., 2005)] for primary care have been identified in multiple pandemic planning documents. These documents call for effective bi-directional communication between primary care providers and decision makers, strategies to engage and communicate with primary care providers, and the importance of developing guidance documents specific to primary care (Health Canada, 2003; Ontario Ministry of Health Long-Term Care, 2009, 2013; Public Health Agency of Canada Health Canada, 2010).

Despite these recommendations, there is very little scientific literature on information management for family physicians during a pandemic. A report from the SARS pandemic noted that very little guidance relevant to a pandemic response [e.g., infection prevention and control (IPAC) procedures] was given to primary care, which led to some FPs becoming exposed to SARS (Health Canada, 2003; Government of Canada, 2018). While previous research has examined the effectiveness of crisis communications, none has looked at communication specifically to FPs, even though FPs have been identified as trusted sources of crisis communication to the public (MacKay et al., 2021). A formal pandemic plan outlining communication and information management strategies for primary care during a pandemic or other health emergencies has not been developed.

In this study, we describe Canadian FPs' perceptions on communication and information management during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. This study addresses the gap in the literature between the stated best practices of provider communication and the actual experiences of FPs during the COVID-19 pandemic and identifies improvements that could be made to communication and information management for primary care in future pandemics or health emergencies.

2. Materials and methods

We conducted a multiple case study across regions in four Canadian provinces (British Columbia, Newfoundland and Labrador, Nova Scotia, and Ontario) examining FP roles during the COVID-19 pandemic. Our previously published study protocol describes these regions and rationale for their selection (Mathews et al., 2021). Using a semi-structured interview guide, we interviewed FPs between October 2020 and June 2021. We recruited along a wide range of characteristics using maximum variation sampling until we reached saturation (Berg, 1995; Creswell, 2014). These recruitment characteristics included academic appointments, gender, primary care funding and practice model, team involvements, hospital affiliations, practice settings, and rurality.

We included FPs who were clinically active or eligible to be clinically active in their region in 2020. We excluded FPs who were still in residency training; had temporary licenses; or held exclusively academic, research, or administrative roles. Research assistants recruited FPs by emailing study invitations to individuals on faculty lists, practice directories, privileging lists, and provincial Colleges of Physicians and Surgeons search portals. We included recruitment notices in professional organizations' newsletters and social media posts. We also recruited using snowball sampling, where permitted.

During the interview we asked participants to describe pandemic-related roles FPs performed over different stages of the pandemic, facilitators and barriers they experienced in performing these roles, potential roles that FPs could have filled, as well as demographic and practice characteristics. While there were no specific questions about communication and information management, all FPs in this study raised the topic of information management. We adapted interview questions to account for differences in physician roles and broader health system contexts in each region.

We conducted interviews by Zoom (Zoom Video Communications Inc.) or telephone based on participant preference, which were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. We used an inductive thematic analysis approach and developed a coding template from the interview transcripts and interviewers' field notes. At least two members of the research team from each region independently read 2–3 transcripts to identify keywords and codes. We then organized a preliminary coding scheme which we updated to incorporate any additional codes from subsequent transcripts. Regional teams met to compare and refine code descriptions as well as develop a harmonized template with uniform code labels and descriptions. We resolved any coding disagreements through discussion and consensus.

We used the unified coding template and NVivo 12 (QSR International) to code transcripts and field notes. We then summarized participant demographic and practice characteristic data using descriptive statistics. To enhance study rigor, we pre-tested interview questions, used experienced interviewers, verified meaning with the participants during interviews, and kept a detailed audit trail (Berg, 1995; Guest et al., 2012; Creswell, 2014). We included negative cases and used thick description and illustrative quotes. Our interdisciplinary team, including FPs and public health experts, reviewed the initial analyses related to our larger findings.

3. Results

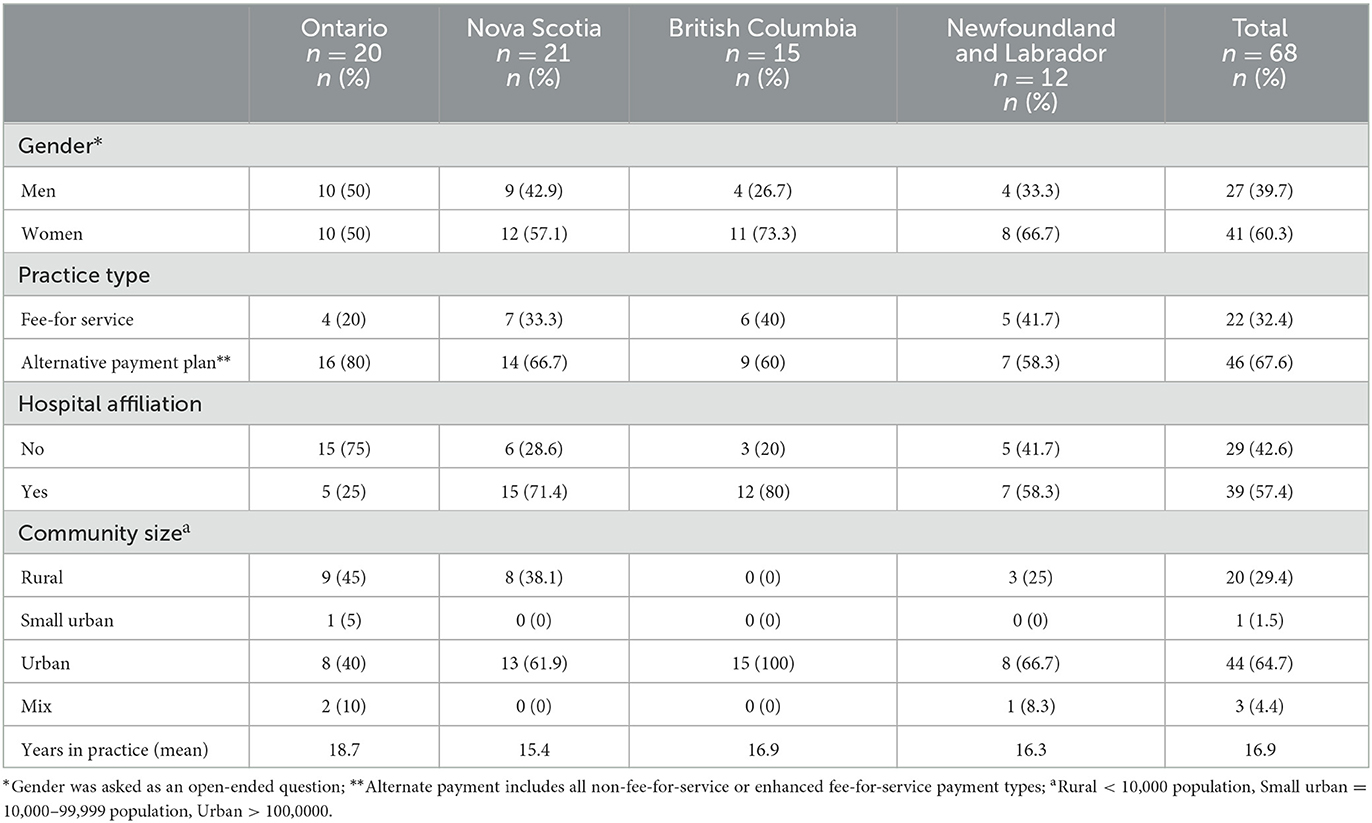

We interviewed a total of 68 physicians across the four regions included in our study: 15 from British Columbia, 12 from Newfoundland and Labrador, 21 from Nova Scotia, and 20 from Ontario (Table 1). The participants included 41 women, 27 men, and 20 FPs who practiced in rural locations. Participants had been in practice for an average of 16.9 years. Twenty-two physicians were paid through fee-for-service remuneration schemes, and 49 had hospital privileges. In this article we report findings from the codes on communication and management of information. We describe two overarching themes: (1) FPs' experiences of obtaining information, and (2) the specific attributes of information that FPs valued.

3.1. Obtaining information

Participants received information (e.g., information was sent to them) and actively sought it out. Although all participants felt they were inundated with information, they still felt the need to seek out information relevant to them.

3.1.1. Inundated with information

At the start of the pandemic, in early 2020, FPs were overwhelmed by the information they received. In all four regions of the study, physicians described being inundated with information about COVID-19 from multiple sources, including provincial Colleges of Physicians and Surgeons, medical associations, the Ministry of Health, and provincial public health authorities. The volume of incoming information was exacerbated by requests for details on how FPs wished to receive information [“I can't be barraged by information, including information requesting my information about how I want to get information” (BC06)], contributing to participants' perceptions that communications to family physicians had not been planned or thought out. Physicians partially attributed the quantity of information they received to the rate at which the information was changing:

The thing that I really remember the most was…being swamped with information. Coming from all–so we have Eastern Health, we have Memorial University, we have our own medical association, we have our College of Physicians and Surgeons, we have the College of Family Practice. … And the information was changing at least daily …. [NL05]

Much of the information they received was repetitive and duplicated, and left FPs with the burdensome task of sorting through all the emails from different sources to find any information that might be relevant to them:

…every organization was sending out high alert information every day almost, and so it was just like, you'd open your inbox and it would be like a flood of emails. But most of them said similar things and it was quite annoying actually, to try and skim and decide which ones you need to keep. [BC15]

The duplication of information added to all participants' already heavy workloads and sense of frustration in the early stages of the pandemic.

3.1.2. Actively seeking relevant information

Despite the increased volume of communications, most participants in all four regions of the study did not feel they received the information they needed, but instead had to seek out and piece together information themselves. Participants recalled that early in the pandemic they turned to different sources of information, including formal sources such as health agencies, health authorities, and scientific journals. Some participants chose one source to focus on: “Initially, I was getting all of my information from BCCDC [British Columbia Centre for Disease Control]” [BC14] but others relied on multiple sources, each providing a portion of the information FPs needed to operate their practices:

I was checking the news about how many cases we have… listening closely to Public Health measures …. And basically, my guideline was whatever the government of Canada, the Public Health Agency and Newfoundland and Labrador basically, Medical Association was suggesting me. [NL11]

In addition, all participants in all four study regions sought information from informal sources including social media networks such as Twitter and Facebook. A participant in Ontario noted that they felt that the most “practical” information they received came from social media: “…I guess a lot of my information that I got was a lot of practical points, were actually online through a Facebook group for physicians” [ON16]. Physicians created their own networks and communicated with each other to learn how other clinics were implementing guidelines: “…the amount of phone calls between physicians and text messages, to see what one clinic was doing, to see how we could apply to our clinic ….” [NL10]. Creating networks–whether official or informal–helped participants find relevant information, particularly on operating a practice with required IPAC measures. However, reliance on peers and social media reinforced perceptions among all participants that the information needs and communication with primary care providers had not been considered in advance.

3.2. Attributes of information valued by FPs

Participants outlined six attributes of communication and information that they valued: (1) from credible sources, (2) actionable messages, (3) collated and summarized, (4) consistent, (5) clear, and (6) bi-directional.

3.2.1. Credible sources

Some participants, seeking trusted and high-quality data about COVID-19, turned to local agencies such as local public health units and physician organizations: “I participated in webinars with Public Health for information, for epi reports. … a great support was Doctors Nova Scotia in that they offered that platform that they had and helped to put it together. And was very helpful” [NS07]. Other physicians turned to major academic journals and experts online for clinical information:

I use the New England Journal, that's pretty reputable, … the British Medical Journal had a good COVID site. So, I used those two sources basically as, this is where I'm going to go for the scientific information about this virus …I actually found Twitter to be very helpful… but it's always, look where's it coming from, who's the source, right? [NL05]

These quotations highlight participants reliance on traditional sources of information that had established reputations for providing credible data.

3.2.2. Actionable messages

All participants in all study regions needed information that was relevant and specific to primary care. They found that the information available was not always applicable to their practices. For example, some participants described the information they initially received related to hospitals, without much consideration of how to translate it to community-based settings:

There was lots of guidance about how you should behave in hospitals, or how clinics were going to work in hospitals…. But there was no guidance about how should I redesign my waiting room if I'm in a general practice office…Or how should I do my bookings or the elements of safe phone visiting that I need to pay attention to. [NS01]

Participants felt that this was particularly true when seeking guidance on how to change their clinics to limit potential exposure to COVID-19: “there was really not a lot of very specific guidance, like, ‘Here are the ten steps you need to do in each clinic”' [BC03]. Another participant noted that FPs had to make sense of the information available to them and interpret what it meant for their practices individually or for their local context: “I think that one of the major dilemmas was just keeping up … with the amount of information that was coming… and making sense of it and how that applied to your day-to-day practice” [NL02]. The lack of information targeting primary care providers heightened participants' feelings of anxiety about exposing themselves or their patients to the virus.

3.2.3. Summarized, collated information

In all study regions, participants repeatedly emphasized the need for collated information from a single reliable source to ease the time burden and improve consistency across the primary health care sector:

Initially there was way too much information from like 50 different sources and it was confusing, conflicting and often still is. So, to me, I think there needs to be one source with clear guidance on how we are to approach the new disease that we're dealing with. [ON12]

Participants wanted information that was brief and easy to interpret: “So, I think we got a lot of communications … but they weren't necessarily coming from a central spot in an easily digestible format that we could quickly implement in practice” [ON15]. Almost all participants noted that as the pandemic progressed, the delivery of information improved:

… Department of Family Practice for [the provincial health authority] created its own newsletter that had multiple links in it about different topic areas. As opposed to what were, in the early days, twelve separate emails about each one of those topics…. [NS01]

The need to collate and synthesize information magnified participants' workload. Moreover, the need to translate information for the primary care setting added to a general sense of uncertainty and frustration.

3.2.4. Consistent information

Almost all participants across the four study regions reported having issues with inconsistent information and needing accurate information to manage their practices and for the public: “sometimes what the [Centre for Disease Control] and what the Health Authority would say would not be in alignment and that was very frustrating” [BC02]. The lack of consistency caused increased work for physicians who had to help translate resources, direct patients to the correct services, and answer questions. Information inconsistencies also impacted physicians' abilities to implement effective plans for their clinics. For example, one participant expressed frustration around inconsistencies and conflicting information of public health guidelines, which influenced their ability to provide care for their patients:

And I would also say that around developing and implementing a triage plan … we continue to have a lot of uncertainty about how to do that well. I mean, who should come in and who shouldn't come in and how we make decisions around that. It has been difficult from the start, but it's more difficult during the phased reopening because there's what seems to be a lot of inconsistency around what people are allowed to do. [BC01]

As an example, some participants were unclear on how to prioritize preventative care, such as cervical cancer screening. Moreover, while public health guidelines limited in-person visits in primary care settings, these guidelines did not seem as restrictive for other sectors, such as beauty salons and restaurants. Participants from all four study regions felt awkward having to explain these inconsistencies to patients.

3.2.5. Clear information

All participants also found there was ambiguity on communication surrounding the supports they would receive, particularly with respect to personal protective equipment (PPE) and the sudden transition to virtual care: “So, we never had any guidance as to what to do at the clinics, who to bring in, what our obligations were, when we would get PPE, would we get paid even, you know, because a lot of us transitioned to virtual care without there being any formalized plan for that” [NL11]. Further, many participants had trouble locating information to guide how they were expected to manage virtual care and access to other health services. Many felt there was a lack of direction and clarity from local authorities: “… it would have been great to get some kind of top-down approach on direction, on how to coordinate the system. … if we have a sick patient …, who do we call, referrals, all of those things were really up in the air” [ON07]. This was echoed by a physician in British Columbia who said “… it would be nice to have more deliberate strategy around how often someone should be seen in-person, …you know, every second prescription at least should be done in-person for diabetics or every–because it's nice to check their blood pressure and actually lay eyes on them” [BC13]. These experiences reinforced participants' feelings that primary care and the role of FPs during the pandemic had not been prioritized by health system planners. Participants from all study regions shared this sentiment.

FPs in the study felt they were unable to help patients access the care they required. Participants reported confusion on which specialists were offering services and what conditions warranted further care. A FP in British Columbia emphasized the need for clearer guidelines on what conditions were considered urgent: “… it would have been good … to have a bit of a more clear guideline the way that radiology guideline had–[a] step-wise, reopening of mammography… what kind of MRIs are considered urgent” [BC07]. A physician in Nova Scotia reported that clearer communication to the public on how to access health services during COVID-19 was also needed. Without information to navigate the system, participants felt frustrated that they were unable to help their patients access services or provide high-quality care. This also reinforced participants' sense that the contributions of primary care within the larger health system and in the pandemic response were not highly valued.

3.2.6. Bi-directional communication

Many participants also noted the need for points of contact at public health agencies and other organizations to facilitate bi-directional communication during a pandemic. Individual experiences varied by study region. FPs explained that, in their experience, bi-directional communication only occurred when it was initiated by them. Some participants felt they were well-supported by physician networks or public health agencies: “…if I was wondering about something, I would just email the Family Practice Network and they would get back to me with an answer” [NL08]. Similarly, a participant in Nova Scotia shared: “there was never a point when I couldn't pick up the phone and call somebody and get an answer, right?” [NS19]. In contrast, other participants felt they had no place to ask questions or ways to give ideas and engage in a dialogue with health authorities:

So, the other thing is that there was no direct communication or two-way dialogue between the Public Health and family doctors. It was impossible…. we'd receive communications, one-way faxes or emails from the Public Health essentially with their directives. But it was impossible to have a two-way dialogue or a conversation to ask questions. [BC10]

Many participants did not feel that their concerns, and primary care in general, were important in the pandemic response. A participant in Ontario ultimately invited a Public Health representative to attend meetings with FPs to simplify communication between community FPs and public health officiants in his community:

We invited a representative from Public Health to join us and … from there, communication improved drastically…. we could ask direct questions, we could get immediate real-time feedback, we could run ideas by them, they could let us know what was changing in the system, what to anticipate as best as they could tell. They could correct any misunderstandings about COVID management and expectations. [ON04]

Having the ability to speak directly with managers allowed the participant to resolve concerns in a timely manner but also suggest ideas and solutions. The two-way communication made participants feel valued and that they were part of a coordinated pandemic response.

4. Discussion

Using qualitative interviews with FPs in four regions in Canada, we described the experiences of FPs in obtaining the information they needed to provide care during the pandemic. This study highlights how, across all study regions, FPs had to contend with overwhelming, delayed, and contradictory information that made it difficult to manage their practices, leaving them to seek out needed information on their own. Some participants had opportunities to communicate directly with public health and system managers, which improved their personal experiences and instilled a sense that primary care providers were valued. Our findings are consistent with studies from other high-income countries that found that during the early stages of the pandemic, primary care providers had to manage rapidly evolving information and practice guidelines that focused on secondary settings (Gray and Sanders, 2020; Kurotschka et al., 2021; Smyrnakis et al., 2021; Sotomayor-Castillo et al., 2021; Adler et al., 2022; Mahlknecht et al., 2022; Van Poel et al., 2022; Makowski et al., 2023). We also identified attributes of information that FPs valued: credible, clear, consistent, collated, brief, actionable, bi-directional, and relevant to the primary care setting. Our findings are consistent with frontline clinicians' experiences during the 2009 influenza pandemic in Utah, which found that clinicians preferred a single, institutional-sourced email for clinical guidance (Staes et al., 2011). Moreover, they align with the general principles of communication plans in a health crisis, especially the need to build trust and cooperation by including mechanisms to engage and listen to stakeholders, specifically, primary care providers (World Health Organization, 2008; Centers for Disease Control Prevention, 2018; Henry, 2018; Hyland-Wood et al., 2021).

Our findings provide insight into the range of topics that are important to FPs: epidemiology of the virus; clinical presentation and management of the illness; access to testing and vaccination; safe management of practices (e.g., IPAC, triaging patients for virtual care, billing information), and access to services (especially diagnostic and specialist services). While information related to a novel disease (i.e., its epidemiology, clinical presentation and management) may not be known in advance, the information needed to prepare FPs to adapt their practices and provision of routine primary care can be anticipated and prepared in advance of the next pandemic, taking into account the attributes valued by FPs.

Studies have also reported the need to ensure that communication infrastructure is in place to disseminate information to community-based practices (Mathews et al., 2022; Mathews et al., 2023). In Canada, many primary care practices are privately owned and operated (Health Canada, 2003). These practices may be unaffiliated with health authorities or hospitals. Alami et al. (2021) reported that structural and sectoral “silos” presented a persistent barrier to effective data sharing and communication during the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada. Integration and affiliation with local health authorities or hospitals gave FPs access to information resources as well as networks and supports that they could turn to for advice (Smyrnakis et al., 2021; Mathews et al., 2022). Communication plans must incorporate strategies to communicate with these individual practices that do not have formal linkages, such as creating email lists of community-based FPs. Pandemic plans should include means to facilitate bi-directional communication between FPs and public health and local health authorities, such as identifying contact persons, involving FPs in pandemic leadership groups, and creating opportunities for FPs to meet with public health and pandemic response personnel.

The value of intermediaries in communication with FPs during the pandemic was repeatedly flagged. Khan et al. (2019) noted that establishing the capacity for coordinating joint, consistent, and timely messaging with relevant network partners is a key indicator of emergency preparedness. Organizations such as physician professional groups, public health, and health authorities stepped up to facilitate communication to FPs and delivered trusted content that was needed. Future pandemic plans should have clear roles for these organizations in facilitating communication to the FP workforce. Organizations such as physician professional groups are likely to also have up-to-date email contacts as part of their enrollment and registration.

4.1. Limitations

Interviews were completed between October 2020 and June 2021 in four Canadian provinces. Our findings may not reflect the experiences of primary care professionals in other areas or at later stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. Most Canadian FPs are paid by fee-for-service and do not have hospital affiliations, while most of our participants were paid by alternate payment plans and had hospital affiliations; therefore, the data collected may not be an accurate representation of the experiences and perspectives of FPs in these regions. Interviews are subject to recall and social desirability bias (Coughlin, 1990; Bergen and Labonté, 2020); however, this was mitigated in our study through the use of consistent probes during the interview process.

5. Conclusions

FPs found the volume of information they received at the start of the pandemic overwhelming, with duplication and inconsistency, forcing them to sift through the information to figure out what was relevant to their practices. Our findings emphasize the need to incorporate communication planning specific to FPs in pandemic and disaster plans. Particular attention should be paid to creating collated information that comes from trusted, up-to-date sources that is specific to primary care. This could allow for better integration of primary care into pandemic plans.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because of the need to maintain participant confidentiality; however, a portion of these data may be available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to bWFyaWEubWF0aGV3c0BzY2h1bGljaC51d28uY2E=.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Research Ethics Boards at Simon Fraser University and the University of British Columbia (through the harmonized research ethics platform provided by Research Ethics British Columbia), the Health Research Ethics Board of Newfoundland and Labrador, Nova Scotia Health, and Western University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

GY and MMa wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. GY, MMa, MMc, LH, EM, JL, DR, SS, PG, and EC critically reviewed and edited the manuscript. MMa, LH, JL, EM, RB, SS, DR, LMe, and LMo carried out the methodology related to the study. MMa, LH, EM, and JL supervised the project. MMa, LMe, LH, SS, EM, JL, RB, and DR contributed to administration of the project. MMa, LH, EM, and JL acquired funding. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (Grant Number VR41 72756).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adler, L., Vinker, S., Heymann, A. D., Van Poel, E., Willems, S., and Zacay, G. (2022). The effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on primary care physicians in Israel, with comparison to an international cohort: a cross-sectional study. Isr. J. Health Policy Res. 11, 34. doi: 10.1186/s13584-022-00543-8

Alami, H., Lehoux, P., Fleet, R., Fortin, J. P., Liu, J., Attieh, R., et al. (2021). How can health systems better prepare for the next pandemic? Lessons learned from the management of COVID-19 in Quebec (Canada). Front. Public Health 9:671833. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.671833

Berg, B. L. (1995). Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences. 2nd edn. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

Bergen, N., and Labonté, R. (2020). “Everything is perfect, and we have no problems”: detecting and limiting social desirability bias in qualitative research. Qual. Health Res. 30, 783–792. doi: 10.1177/1049732319889354

Centers for Disease Control Prevention (2018). Resources for Emergency Health Professionals: Crisis and Emergency Risk Communication. Available online at: https://emergency.cdc.gov/cerc/ (accessed August 3, 2023).

Centers for Disease Control Prevention (n.d.). CERC in An Infectious Disease Outbreak. Available online at: https://emergency.cdc.gov/cerc/resources/pdf/CERC_Infectious_Diseases_FactSheet.pdf (accessed August 3 2023).

Coughlin, S. S. (1990). Recall bias in epidemiologic studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 43, 87–91. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(90)90060-3

Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research Design - Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches. 4th edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications Ltd.

Government of Canada (2018). Canadian Pandemic Influenza Preparedness: Planning Guidance for the Health Sector. Available online at: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/flu-influenza/pandemic-plans.html (accessed January 30, 2023).

Gray, R., and Sanders, C. (2020). A reflection on the impact of COVID-19 on primary care in the United Kingdom. J. Interprof. Care. 34,672–678. doi: 10.1080/13561820.2020.1823948

Guest, G., MacQueen, K. M., and Namey, E. E. (2012). Applied Thematic Analysis. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications Ltd. doi: 10.4135/9781483384436

Health Canada (2003). Learning from SARS: Renewal of Public Health in Canada. Available online at: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/reports-publications/learning-sars-renewal-public-health-canada.html (accessed January 20, 2023).

Henry, B. (2018). Canadian pandemic influenza preparedness: communications strategy. CCDR. 44, 106–9. doi: 10.14745/ccdr.v44i05a03

Hyland-Wood, B., Gardner, J., Leask, J., and Ecker, U. K. H. (2021). Towards effective government communication strategies in the era of COVID-19. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 8, e1–11. doi: 10.1057/s41599-020-00701-w

Inouye, J. (2014). Risk perception: Theories, Strategies and Next Steps. Campbell Institute. Available online at: https://www.thecampbellinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Campbell-Institute-Risk-Perception-WP.pdf (accessed August 3, 2023).

Jaeger, P. T., Thompson, K. M., and McClure, C. R. (2005). “Information Management”, in Encyclopedia of Social Measurement, Volume 2, ed K. Kempf-Leonard (Amsterdam: Elsevier Inc.), 277–282. doi: 10.1016/B0-12-369398-5/00531-4

Khan, Y., Brown, A. D., Gagliardi, A. R., O'Sullivan, T., Lacarte, S., Henry, B., et al. (2019). Are we prepared? the development of performance indicators for public health emergency preparedness using a modified delphi approach. PLoS ONE. 14:e0226489. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0226489

Kurotschka, P. K., Serafini, A., Demontis, M., Serafini, A., Mereu, A., Moro, M. F., et al. (2021). General practitioners' experiences during the first phase of the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy: a critical incident technique study. Front. Public Health. 9:623904. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.623904

MacKay, M., Colangeli, T., Thaivalappil, A., Del Bianco, A., McWhirter, J., and Papadopoulos, A. (2021). A review and analysis of the literature on public health emergency communication practices. J. Commun. Health. 47, 150–162. doi: 10.1007/s10900-021-01032-w

Mahlknecht, A., Barbieri, V., Engl, A., Piccoliori, G., and Wiedermann, C. J. (2022). Challenges and experiences of general practitioners during the course of the Covid-19 pandemic: a northern Italian observational study-cross-sectional analysis and comparison of a two-time survey in primary care. Fam. Pract. 39,1009–1016. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmac025

Makowski, L., Schrader, H., Parisi, S., Ehlers-Mondorf, J., Joos, S., Kaduszkiewicz, H., et al. (2023). German general practitioners' experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic and how it affected their patient care: a qualitative study. Eur. J. Gen. Pract. 29:2156498. doi: 10.1080/13814788.2022.2156498

Mathews, M., Meredith, L., Ryan, D., Hedden, L., Lukewich, J., Marshall, E. G., et al. (2023a). The roles of family physicians during a pandemic. Healthc. Manage. Forum. 36, 30–35. doi: 10.1177/08404704221112311

Mathews, M., Ryan, D., Hedden, L., Lukewich, J., Marshall, E. G., Brown, J. B., et al. (2022). Family physician leadership during the COVID-19 pandemic: roles, functions and key supports. Leadersh. Health Serv. 35, 559–575. doi: 10.1108/LHS-03-2022-0030

Mathews, M., Ryan, D., Hedden, L., Lukewich, J., Marshall, E. G., Buote, R., et al. (2023b). Strengthening the integration of primary care in pandemic response plans: a qualitative interview study of Canadian family physicians. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 73, E348–355. doi: 10.3399/BJGP.2022.0350

Mathews, M., Spencer, S., Hedden, L., Marshall, E. G., Lukewich, J., Meredith, L., et al. (2021). Development of a primary care pandemic plan informed by in-depth policy analysis and interviews with family physicians across Canada during COVID-19: a qualitative case study protocol. BMJ Open. 11:E048209. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-048209

Ontario Hospital Association (n.d.). Effective Communication Strategies for COVID-19: Research Brief. Available online at: https://www.oha.com/Documents/Effective%20Communications%20Strategies%20for%20COVID-19.pdf (accessed August 3, 2023).

Ontario Ministry of Health Long-Term Care (2009). The H1N1 Flu in Ontario: A Report by Ontario's Chief Medical Officer of Health. Available online at: https://collections.ola.org/mon/23009/295092.pdf (accessed March 12, 2023).

Ontario Ministry of Health Long-Term Care (2013). Chapter 9: Primary Health Care Services in Ontario Health Plan for an Influenza Pandemic. Available online at: https://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/emb/pan_flu/docs/ch_09.pdf (accessed January 30, 2023).

Public Health Agency of Canada Health Canada (2010). Lessons Learned Review: Public Health Agency of Canada and Health Canada Response to the 2009 H1N1 Pandemic. Available online at: https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/phac-aspc/migration/phac-aspc/about_apropos/evaluation/reports-rapports/2010-2011/h1n1/pdf/h1n1-eng.pdf (accessed January 30, 2023).

Smyrnakis, E., Symintiridou, D., Andreou, M., Dandoulakis, M., Theodoropoulos, E., Kokkali, S., et al. (2021). Primary care professionals' experiences during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Greece: a qualitative study. BMC Fam. Pract. 22, 174. doi: 10.1186/s12875-021-01522-9

Sotomayor-Castillo, C., Nahidi, S., Li, C., Hespe, C., Burns, P. L., and Shaban, R. Z. (2021). General practitioners' knowledge, preparedness, and experiences of managing COVID-19 in Australia. Infect. Dis. Health. 26,166–172. doi: 10.1016/j.idh.2021.01.004

Staes, C. J., Wuthrich, A., Gesteland, P., Allison, M. A., Leecaster, M., Shakib, J. H., et al. (2011). Public health communication with frontline clinicians during the first wave of the 2009 influenza pandemic. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 17, 36–44. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0b013e3181ee9b29

Van Poel, E., Vanden Bussche, P., Klemenc-Ketis, Z., and Willems, S. (2022). How did general practices organize care during the COVID-19 pandemic: the protocol of the cross-sectional PRICOV-19 study in 38 countries. BMC Prim. Care. 23, 11. doi: 10.1186/s12875-021-01587-6

World Health Organization (2008). World Health Organization Outbreak Communication Planning Guide: 2008 Edition. Available online at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241597449 (accessed August 3, 2023).

Keywords: information management, communication, primary care, family physician, pandemic response, COVID-19, policy planning, qualitative research

Citation: Young G, Mathews M, Hedden L, Lukewich J, Marshall EG, Gill P, McKay M, Ryan D, Spencer S, Buote R, Meredith L, Moritz L, Brown JB, Christian E and Wong E (2023) “Swamped with information”: a qualitative study of family physicians' experiences of managing and applying pandemic-related information. Front. Commun. 8:1186678. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2023.1186678

Received: 15 March 2023; Accepted: 09 October 2023;

Published: 26 October 2023.

Edited by:

Shamshad Khan, University of Texas at San Antonio, United StatesReviewed by:

Uttaran Dutta, Arizona State University, United StatesBrenda Sawatzky-Girling, Health Care Management and Policy Consultant, Canada

Copyright © 2023 Young, Mathews, Hedden, Lukewich, Marshall, Gill, McKay, Ryan, Spencer, Buote, Meredith, Moritz, Brown, Christian and Wong. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Maria Mathews, bWFyaWEubWF0aGV3c0BzY2h1bGljaC51d28uY2E=

Gillian Young1

Gillian Young1 Paul Gill

Paul Gill Dana Ryan

Dana Ryan Sarah Spencer

Sarah Spencer