- 1Manship School of Mass Communication, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA, United States

- 2Retired, Beaumont, TX, United States

- 3Retired, Raeford, NC, United States

Introduction: Black American women's health outcomes have been altered by a number of factors. Those factors include social determinants of health, lack of culturally competent healthcare providers, and generations of medical racism leading to prolonged pain, delayed care, and sometimes, untimely deaths.

Methods: This original research article centers Southern Black women's lived experiences through family storytelling. We explored generations of health narratives in regard to age, region, and at times, their own acts of silence. Building from theorizing on loud healing, two Black daughters turned the mic on for their mothers by engaging in a critical intergenerational double duoethnography to discuss decades of healing over a 3 months long conversation (in person, over the phone, and on video chat).

Results: The analysis of the interviews/dialogue between Black mothers and daughters identified several themes connected to loud healing: (1) some healths lessons are quietly taught from intergenerational trauma; (2) the silencing of Black matriarchs occurs in generations not just spirals; (3) loud healing is a faith-filled call to action; (4) mothers and daughters help turn the mic on for each other; (5) Loud healing is affirming and produces visibility; (6) the body teaches culturally competent health lessons; (7) Trusting loud healing to leave the mic on and door open.

Discussion: Our collective and individual lived experiences reveal the very real impacts of culture, identity, and power on Black women's health and storytelling. By interrogating the past with our stories, this group of Black mothers and daughters represents three generations of medical erasures, amplification of voice, and the need for loud healing for loud, tangible change.

Introduction

“Your silence will not protect you.” Audre Lorde, Sister Outsider

“There is no greater agony than bearing the untold story inside of you.” Maya Angelou, I Know Why The Caged Bird Sings

“Women's rights is not only an abstraction, a cause; it is also a personal affair. It is not only about us; it is also about me and you. Just the two of us.” Toni Morrison

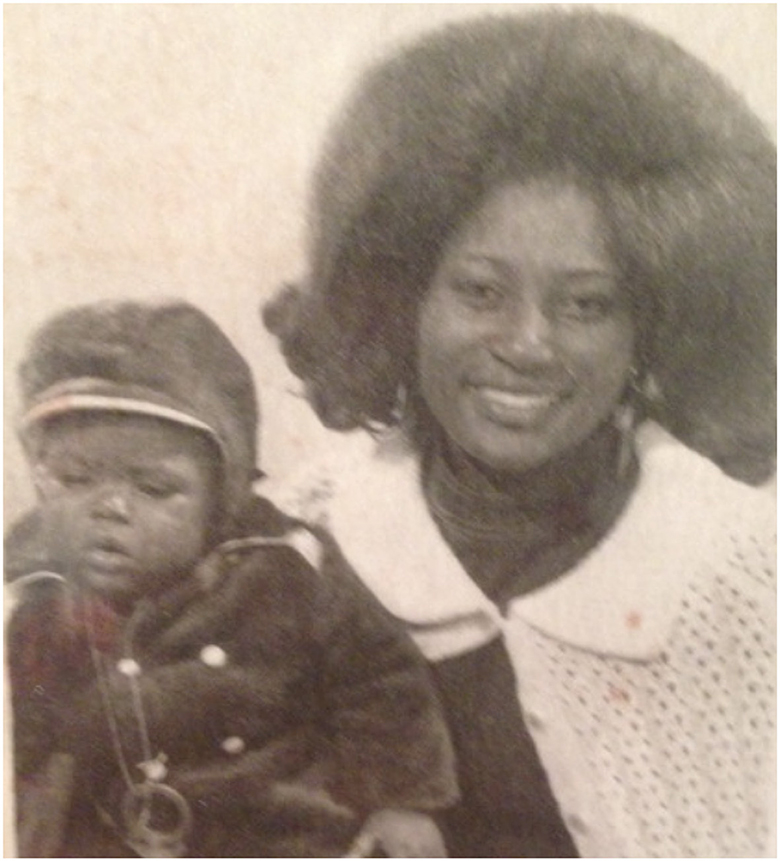

Our mothers have lived through Black freedom movements and endured the racial unrest of the American civil rights movement in the U.S. South and Northeast in segregated schools. They have picked cotton in Deep East Texas with their parents during the 1950s, had vicious dogs chased after them while walking to their neighborhood markets, and have been exposed to dangerous medical care and advice—and yet survived it all with a story to tell. However, in the moments when the personal becomes public and political, the survivors we call, Mama, armed themselves for battle in a protective gear called silence. In this original research article, we interrogate the contemporary context of Black women's health by revisiting the past in a duoethnography (Norris and Sawyer, 2004) with our Black mothers. In the moments that we sat with them and heard their stories and their lived experiences at the hands of oppressive medical practitioners, we learned with and from each other's silence and volume of our pain, even resilience.

First, we realize this particular study is an act of resistance (Watts, 2006; Iqtadar et al., 2020; Batcho, 2021) and restoration for our Black mothers. We call it resistive because these health narratives required our mothers who stayed silent to stay alive, often blended into the normative background of wellness to protect systems of oppression found in healthcare, to be loud and clear. The intentional unearthing of our youthful stories can also restore those who engage with them and who will see themselves in our stories—in and out of the ivory halls of academia (Figure 1).

Our mothers have often described us as brave, courageous, and vocal, without sometimes realizing that our bravery and courageous nature came directly from them. We use this open source research space to illuminate the lived experiences of Black women through multiple generations, contest the dominant narratives around Black American women's health, and thread together our knowledge production like a cultural quilt beautified by the scraps of our lives to critique the impacts of American medicine on African American health. In the end, this study promotes Black women's voices as ontological and epistemological truths, and these truths (without quantitative data, data sets, and traditional methods of inquiry) are very much data…and very much research. These ways of knowing in health communication, specifically through Black women's health experiences, are represented by these intergenerational narratives that have shaped our families in the U.S. since before the 1940s.

Theoretical framework

This current project utilizes Patricia Hill Collins' Black Feminist Epistemology (2000) to frame the duoethnography with our mothers. While it lies between our mother's oral histories and our own autoethnography, framing this study in the four tenets of Black feminist epistemology (BFE) allows us to place Black American women at the center and forefront of the conversation with ethics and care. According to the BFE, there are four guiding tenets to do this study—(1) lived experiences as criterion of meaning; (2) the use of dialogue in assessing knowledge claims; (3) the ethics of caring; (4) the ethic of personal accountability. Collins also recognizes Black women as agents of knowledge, and to put this in conversation with the spiral of silence theory, we explore how silence and loud healing are juxtaposed against each other in Black American womanhood and motherhood. Developed in the 1970s by Noelle-Neumann, the spiral of silence theory can be used to understand how public opinion, society's idea of right and wrong, and individuals' willingness to voice their own opinions have affected the way that Black women have historically not expressed their wants, desires, hurts, and traumas for fear of being alone (Noelle-Neumann, 1974). In other words, fear of their thoughts and attitudes being in the minority, punished, ignored, misunderstood, or distorted plausibly kept Black women silent. Madlock Gatison (2015) uses the spiral of silence theory to discuss how the intersectionality of faith, strong Black womanhood, and a societally driven view of breast cancer survivorship can foster isolation and alienation of the Black woman's experience and encourage silence in the time of great pain. Our mothers' stories of silent pain often paralleled the survivors in Gatison's research in that outside factors and influences kept them from experiencing loud, restorative healing.

An important concept within BFE that is critical to this study is visibility, especially when Black people are often silenced and made invisible within white-denominant culture (Mowatt et al., 2013). We push back by exalting and honoring their narratives. Additionally, Mowatt et al. (2013) draws attention to the lack of representation in studies involving health, making this double duoethnographic study necessary and vital to scholarship. As Black Feminist Thought provides a comprehensive scholarship on the plight of Black women in America (Dotson, 2015), creating an interdisciplinary resource that examines their narratives contributes to the eradication of silence. Ultimately, we interrogate the spiral of silence against loud healing with Black women's intergenerational health narratives at the core.

What is loud healing?

As our study pushes back against the historical, dominant, hegemonic, patriarchal systems that have controlled healthcare in the U.S. since its inception, we call upon loud healing as a tool, weapon, and source of amplification. In order to perform this duoethnography, we asked our co-authors (our mothers) to be loud. Being loud according to Winfield (2022) requires those who have been silenced by those same systems of oppression (those louder voices of power and autonomy, lack of resources listed in the social determinants of health, fear of the unknown futures, and the culture of life, death, and healing in the Black community) to not only be more than visible but also be vocal.

According to Winfield (2022),

Loud healing is the beginning of true intervention. [1] It is intersectional and takes into consideration the whole being for an all-encompassing wellbeing … It, too, is [2] loud and faith-filled but must also continually reject the negative psychosocial experiences that would negatively influence health-seeking. [3] It is community-driven and culturally-competent. Loud healing means no more hiding afflictions or masking miseries to appear normal. Loud healing means academics no longer must hide their debilitating conditions because it's not normalized in the classroom or society. There are places for pain in academic journals … (Winfield, 2022, p.129)

We use the theorizing around loud healing to explore how our intergenerational narratives of healing, health, and hope can combat spirals of silence through Black Feminist Thought. Loud healing provides us with the structure and freedom to identify the themes in our mothers' responses. Loud healing, because it is intersectional in its view of Black women, complicates identity, contextualizes moments in time, calls for other mothers as pedagogues and healers, and is full of faith—that one's resistance and volume will not return unto her void, but are necessary for true and continual health. Loud healing identifies stereotypes and how they influence multiple layers and forms of communication and present complex evidence allowing Black women to remove the mask of strength to receive culturally competent care by their healthcare providers, families, and themselves.

Stereotypes of Black American women have existed since their arrival on cargo ships in the 17th century and persisted in media and culture since then. Some stereotypes and tropes have become so pervasive that their existence reaches beyond the television screens and into the very real lives of Black women. Those historical stereotypes include Mammy, Sapphire, Jezebel, and Tragic Mulatto (Bogle, 1973, 2001, 2015). The Sapphire image describes a Black woman who is emasculating, aggressive, sassy, domineering, angry, and loud without ever providing any explanations or reasons why she had to appear or show up in those ways. The heart of loud healing is courage to be vocal and heard, and those stereotypes work against healing for Black women if the world makes assumptions about the truths of their pain and health conditions.

With Black feminist epistemologies and loud healing as the framework contesting generations of silence and stereotypes, we ask the following research questions to explore the intergenerational family health narratives of Black American women:

RQ1: In what ways (if any) have Black American mothers utilized loud healing to share their health narratives with their Black daughters? What stories have been inherited and shared through multiple generations in regards to their intergenerational and intersectional identities?

RQ2: What themes arise for Black mothers when performing medical memory-work through family storytelling with their adult Black daughters?

Methods

For this study, we adopted what we are calling a critical intergenerational double duoethnography to capture how two Black American women engaged their Black mothers in health and family storytelling. We chose this format to not only engage our own ways of knowing as it relates to Black women's health and health storytelling but also bring light to our shared and individual experiences of love, blood, and struggle. It is birthed from the sometimes broken bodies, broken systems, and beautiful Black women that found a way(s) to survive in the midst of it all. Our mothers' stories of survival and their familial health narratives not only influenced our scholarship but also inspired this study. We hope to motivate many other scholars and practitioners to understand the long history of health issues and disparities that have played major roles in lives and bodies of Black American women and in the stories [or lack thereof] they tell their Black daughters. Those stories captured here are their own, and yet they echo the songs of so many other Black women.

Duoethnography is designed for two or more researchers to collaborate on the understanding of a phenomenon by spotlighting their personal narratives (Norris et al., 2012; Denzin, 2018; Brown and Gilbert, 2021). Within this methodology, the interpretation of the story is based on the art of listening, questioning, and reconceptualizing, based on the meanings presented by the researchers (Heavey and Jemmott, 2020). Due to lack of representation and the need for critical discourse based on lived experiences (Walker and Di Niro, 2019), the creators of duoethnography, Sawyer and Norris (2015) posited, “To keep the voices separate, we began to write in script format in a way to promote the quest of inquiry as a phenomenological process of reconceptualization, not the identification of portable research findings and answers.” Similar to Madden and McGregor (2013), the utilization of duoethnography examines the frameworks of culture-centered approach and intergenerational narrative work to reflect on literature around Black women's health through storytelling.

Scholars have used double duoethnography in previous studies (Pung et al., 2020) to capture the multiple and intersecting perspectives of scholars based on gender differences. This method is a dialogic method, where a collaborative construction of the discourse is created to compare experiences and attach meaning to the stories while exchanging reflections (Mair and Frew, 2018; Pung et al., 2020). In other words, while these particular conversations have been occurring all of our lives, over the course of several conversations with our mothers and each other, we reproduced our mothers' pedagogy around health. However, with an intention of shedding light on multiple experiences, we (Asha and Hope) asked our mothers a set of questions to guide our conversations and assist in our analysis, interpretation, and meaning-making processes with each other and ourselves. Following the work of Durham et al. (2020) who declared that the future of autoethnography was Black and that this work is radical—we dared to ask and answer the questions. Using Boylorn's (2015) non-linear, polyvocal narratives of multigenerational Black women in Sweetwater:Black women and Narratives of Resilience, we borrow her courage to share our truth:

Because my story is hers

Hers is mine

What does it mean for me to tell our story?

My secrets are someone else's secrets

My pain unlocks someone else's pain

My memory is not the same as someone else's memory …

My mother's scorn

My reflections song

Boylorn uses autoethnography to reveal truth. Boylorn (2015) declares “Telling was murder and I anxiously became a co-conspirator, killing the silence with the story.” Using Black women scholars' work through BFT and narrative work, we let the stories lead us into an intergenerational, polyvocal, non-linear reckoning.

All five authors played the role of researchers and the researched much like Pung et al.'s study. Many duoethnographies only include two co-authors, but ours includes 2 [academic] daughters and our mothers. We all identify as Black/African American women who have only lived in the United States (see descriptions in Section 3.1.1.). We recorded conversations with our mothers using Otter.ai and obtained the transcripts to sit in the abductive process of interpretation.

Using semi-structured interview questions, we asked our mothers to share their life stories with regard to the health narratives. The conversations occurred over multiple days and dialogues in the Spring of 2023 (January–March), always coming back to the conversations before. After several weeks of conversations with our mothers, the co-authors coded all of the conversations for the themes across all dialogues and topics. We then asked our mothers to share photographs that would help to supplement the stories they shared with us. When our mothers could not find the photographs, we asked other Black women relatives to help tell the generational narratives using images. Those photographs are included throughout this duoethnography as timestamps to the combined narratives. This photo elicitation (Harper, 2002) in concert with memory work (Madden and McGregor, 2013; Grant and Radcliffe, 2015; Khoo-Lattimore, 2018) provides a comprehensive snapshot of the experiences our mothers' chose to share.

The dialogue

Self-portraits and heavy influences

Loud healing first begins with how we see ourselves, others, systems, and ourselves in relation to others and big/small systems. Loud healing requires a mirror, a mic, and a speaker—figuratively, metaphorically, and internally.

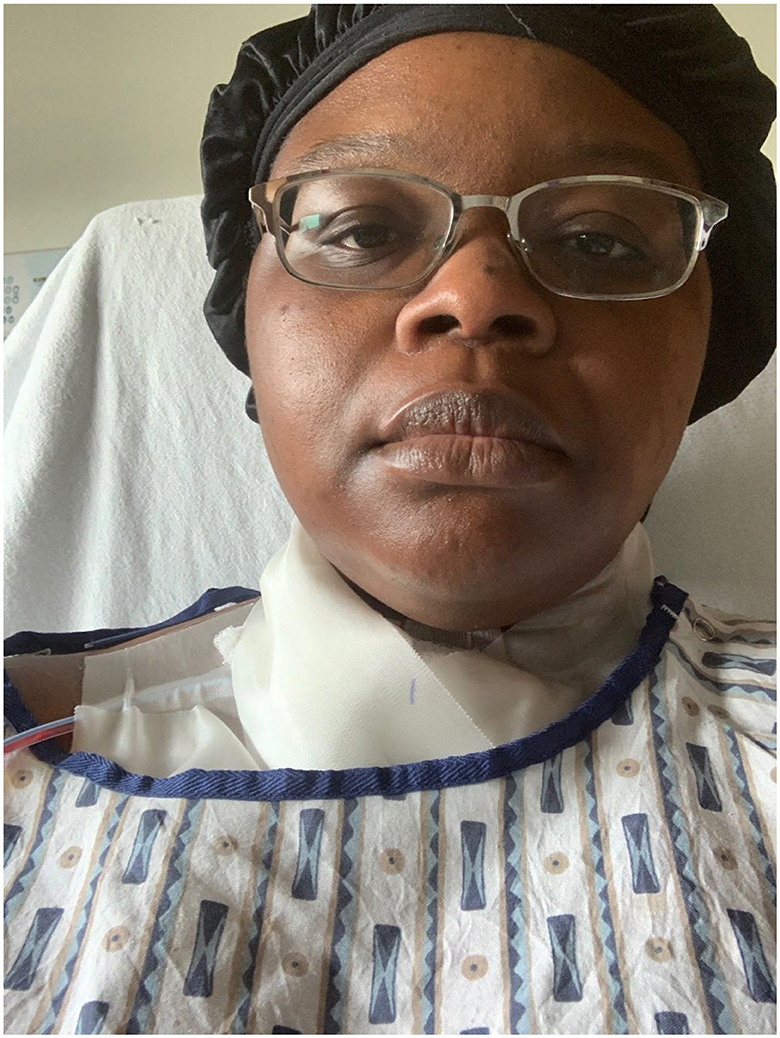

Asha: I am a 33-year-old Black American woman from Big Money Texas also known as Beaumont, Texas.1 I received my Ph.D in 2021, and I've been a tenure-track professor at a large research university in the US south for about 2 years now after teaching at several colleges in Texas since 2013. I have had a long history with uterine fibroid issues that have impacted my entire life and resulted in two different fibroid surgeries (2019 and 2022), as well as a back surgery (2020), most of which happened during my doctoral studies (2018–2022). I have written about these critical health experiences through a culture-centered lens (Winfield, 2022), and they have highly motivated and influenced the work that I do around Black women's health representations in the media, culture, and society.

My mother, Mama Ann, is a 74-year-old woman from San Augustine, Texas who graduated in the 1970s from Texas Southern University and became a pharmacist (Figure 2). She and my father, Rev. Jerry, have been married since March 1972, and they have five children including two sets of twins 13 years apart. She was a pharmacist for over 40 years in Texas, and I watched her care for our entire city and Jefferson County my whole life in that role. During hurricanes and disasters, Mama Ann would have to come back early to make sure the city's most vulnerable residents had access to their medicines needed for survival—those experiences, volunteering alongside her, shaped my care for the community. She's taken care of everyone, and I mean everyone—she is the one sick folks call before they call their doctor. Throughout my life, my mother would share her own testimony of fibroid issues with me, as well as her experiences living in Texas during racially tense times of the civil rights movement in America, particularly the 1950 and 60s. We did not often talk about how the movement impacted Black women's health choices and outcomes. She is most proud of being our mother and her work as a pharmacist. When I asked her to describe herself, it is the first thing she mentioned (Figure 3).

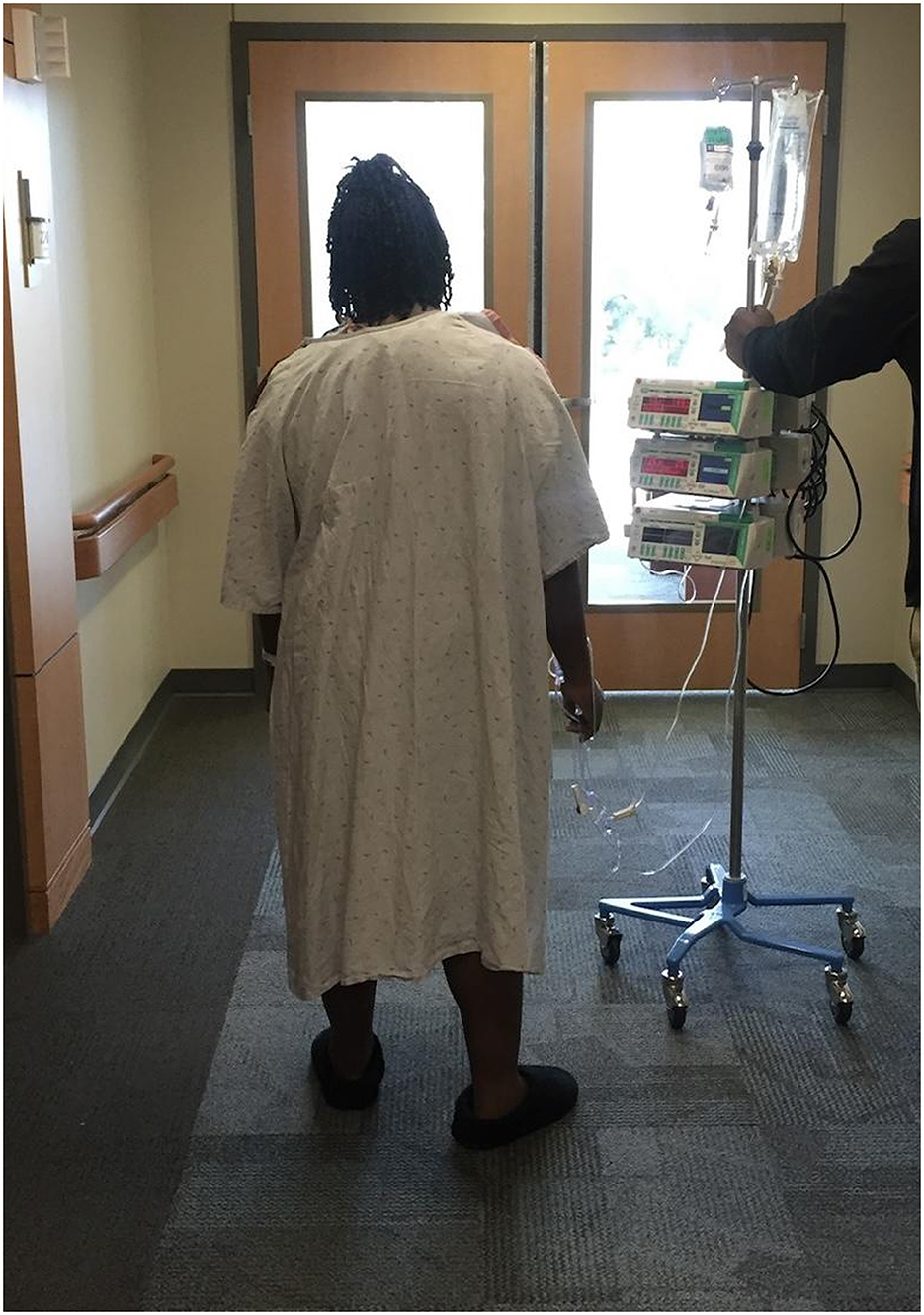

Hope: I am a Black American wife of 8 years and mother of 2 children, ages 7 and 5. I was born in New York and raised in North Carolina. I am currently a PhD candidate and plan to graduate in 2024. I was blessed and lucky to not have any health issues that required medical intervention until 2015 when I had my first C-section, 2017 when I had my second C-section, and 2018 when I had to have a hernia repair surgery. Then in 2019, a cyst on my thyroid gland grew big enough to push my esophagus over and bulge out of the side of my neck. Recently, I have had two back surgeries during the summer of 2023, during my doctoral studies. These experiences all played a part in my research interests in media messaging and health communication for Black women and mothers, and other marginalized communities (Figure 4).

My mother, Mama Brigitte, is a 63-year-old woman born and raised in Brooklyn, NY. She joined the Army right after high school and met my father. With Baby Me in tow, they eventually settled in North Carolina where my mom still lives. I have watched my mother work very physically demanding jobs all of her life and yet she still found the energy to run our household and take care of everyone else. My mom always made sure that my siblings and I felt comfortable enough to talk with her about anything health-related but she found it hard to talk about her own health issues with us. A learned behavior passed down from my great-grandmother and grandmother, my mom continues to hold strong to the habit of not telling us about any potential health problems until pressed or she has no other choice. Just like Mama Ann and Asha, we hardly ever talked about how the civil rights movement impacted a Black woman's health.

Together looking in the mirror of the weight room

One of the common themes present in our mothers' generations and their own descriptions of themselves is their ability to take care of everyone else while at times ignoring, dismissing, and avoiding their own health issues through the silences their mothers passed down to them. That is the same silence we initially interrogated when beginning this discussion. Listening to the ways in which they honored their own legacy through their selfless identity-making brings up the tenets of the Strong Black Woman trope (Romero, 2000). Romero found that [Black] African American women are identified as strong, self-reliant, and self-contained and maintained the roles of “nurturing” and “preserving the family.” Our mothers bore the burden of strength applied by society and health systems onto Black women and adopted those selfless colorless pixels as a part of their overall image. Loud healing begins with complex identification through careful lenses. It was important for us to ask our mothers how they see themselves but to also add what we see to the frame. Loud healing requires us to see each other, our intersectional identities, and the oppressive nature by which we have cared for ourselves and others when life's microphone was silenced.

Initial tensions

One of the first battles we needed to address was what it meant to be transparent, and honest about our individual and collective pasts … The past of our bodies and the stories hidden deep without our tissues and muscles. Muscle memories … do in fact keep the record and know the score. For Mama Ann, there was an instant fear that came with the opportunity of sharing her story, her testimony, and her lived experience, because while others can talk about the topic and experience sympathy for my mother and other Black women, her lived experience was her reality and a very personal one (as she noted in her interviews); often a very silent one. For Mama Ann, the fear of calling it out and saying what it really was and how she had really been treated in regard to her uterine health was anxiety-inducing. She wanted to be presented authentically (with scholarly edits) as much as her initial fears would allow.

Mama Ann: I don't know if I can do this, baby. It's a painful subject. A lot of people have a lot of shame around this topic and it's really personal … we didn't have any good doctors for the Black people [back in 1940–60s in Deep East Texas]. People really didn't wanna tell things about that.

Asha: You don't have to write anything, you just have to talk to me.

What is important to note here is that loud healing was a collective, familial effort from one mother to her daughter. Loud healing is not a solo act, and the method of qualitative inquiry allows us to sit with the stories, feelings, emotions, and regrets. Loud healing permits us to patiently, fearfully, and courageously sit in truth and honor.

Engaging our first stories

Asha to Mama Ann: Some of my earliest memories of having my cycle and you being there are very emotional memories for me, but what I remember the most is that you always believed my pain. I can remember being in middle school, in the sixth grade, and I would be so weak and hurting so badly that I was near passing out. I would be losing my sight, and I would somehow find a way to the nurse's office after I told my teacher that I wasn't feeling well. On one occasion, I remember being in science class, Mrs Simmons at Odom Academy, and I was on my knees, taking my examination because I was hurting so badly and nobody checked on me, not one person. I finished my test and I made it through several hallways to the nurse office and she did not greet me with kindness. She told me that this was my life now and that I needed to start being prepared because I couldn't be missing classes for my cycle every month. She allowed me to call home and to call you at work and you came over as fast as you could. You took me home and you cared for me and that happened so many times throughout middle school and high school and college. So while the world was misunderstanding what was happening in my body, you recognized my pain as your own and you cared for me. You taught me how to care for myself.

Hope: One of my earliest memories of having a health-related conversation with my mother was when my period first began. I remember it like it was yesterday. I was 11 years old, just having gotten home from school, when I felt a pressing need to use the bathroom. Sitting there on porcelain, I was confronted with the tell-tale signs of impending womanhood and yelled for my mama like the child I still was. My mom pokes her head into the bathroom and could tell what was happening by the look on my face. She said, and I quote, “well, like your grandma told me, you're a woman now. So keep your panties up and your dress down because you can get pregnant now.” She then softly closed the door behind her and left me to try to figure out what she meant. And that was it. That was my sex talk from my mom.

Mama Brigitte: (Deep breath) Ok. I tried to give you and Brittany [my younger sister] more explanation about things because back then, my mother, your grandmother, she explained things to us, but she didn't go into depth. You know, I tried to give explanations, hopefully, a little better than my mother. If I wasn't satisfied with what she was saying, I worked it out on my own but I tried to do more explaining. Especially with you. You know, we talked. I always wanted you to feel like you could come to me and we could talk about anything. I tried not to hide anything. Even if I was uncomfortable with it. It didn't matter. I tried to explain it, give more information. Yeah, I think I was a little more, uhhhhh uhhhh, a little more…what's the word I'm looking for? A little more receptive to hearing things from my girls than my mother was. She gave explanations. It was good, but it was short. It was either a yes or no, or no you can't do that, but that was it. I tried to do more. I tried.

Hope: And you did a great job because you see how I passed that down to my kids. I take the time to explain things to them. You see that. You started that and I'm passing it on. Because I want my kids to feel comfortable talking to me too. You know, yeah.

Mama Brigitte: I do see it. Thanks, my daughter.

Together in the intergenerational pow[d]er room

(Hope): While Mama Brigitte wasn't always the most forthcoming when it came to health conversations, I always felt that I could go to her if I had any questions. While it might not have been easy for her, I instinctively knew that she would listen and answer my questions as best as she could.

(Asha) Mama Ann tried throughout my life to give me as much information as she felt comfortable giving. I always knew she wanted me to be well, but I could also see how uncomfortable the truth was when it came to uterine fibroids and other reproductive health topics. I was about 21 years old and fresh from the gynecologist who told me I had large fibroids, when she finally had a “sex” talk with me. I was dating an older young man from church, and she was concerned. All she said was “it's gonna hurt” and followed it with “kissing will get you pregnant, so don't be kissing.” I saw how hard it was for my mother to say even those parts but she said it's the same lessons she was told when she was my age. However, by 22, my mother was married and on her way to motherhood in 1972.

Theme: quiet lessons borne from intergenerational trauma

Relationships between mothers and daughters can oftentimes be a complicated and expensive handbag of trials and tribulations (Figure 5). As a parent myself, I now know that my mom did the absolute best she could in raising my siblings and I. Neurobiology research tells us that parents tend to raise their children in the same ways that they themselves were raised (Lomanowska et al., 2017). I think that should be taken a step further—not only do mothers tend to parent the same way they were parented but they also pass along lessons learned through the generations to their daughters, especially those rooted in trauma, to keep the negative cycles from continuing.

Hope: What kinds of stuff did you talk about with Grandma as a young woman that you wanted to make sure that you shared with me and Brittany (my sister)?

Mama Brigitte:

Most important thing was, don't trust a man, you know, don't take them at their word. You know, back then…they were so scared of you having sex and all that stuff. Don't be too trusting when it comes to a man talking to you about your body parts. That's the one that stays with me the most. Of course, I would ask some more questions and I wouldn't get anything but I always figured something must've happened, you know. So, when it comes to that, yeah, it was don't trust men. You know that's how it was back then. She didn't ever go into deep conversation about stuff but she would give you a little piece. And she was right as you know. They only ever want to get your coochie [or want to have sexual intercourse with you].

Hope: In this snippet, Mama Brigitte alluded to trauma that she assumed her mother might have experienced (Figure 6). Whether or not her assumption was confirmed, my mom passed that lesson down to me. I remember feeling like a veil had been removed from my eyes after that conversation. I began looking at boys and men differently. I felt I had to in order to protect myself and carried that anxiety with me all of my adult life. According to the Violence Policy Center (2021), “In 2019, Black females accounted for 14% of the female population in the United States, and yet 28% of the females killed by males in single victim/single offender incidents where the race of the victim was known were Black”.

I recently had an age-appropriate conversation with my 5-year-old daughter about good touch and bad touch (Figure 7). While we were talking, my mom was quietly listening and supporting me in the background. My grandmother passed down her message of interpersonal safety to her daughters in the only way she knew how—quietly and without making waves. My mother followed in her footsteps with my sister and I; however, I always knew if I had a question or concern about anything, she would answer. Now, as a grown woman with my own daughter, I am breaking that cycle of quietness by being intentional and very direct as I teach her life lessons. I don't want her to have any confusion or hesitancy when it comes to consent and appropriate touch. As my mom watched my daughter and I talk, I could see from the smile on her face that she was proud of me. My own loud healing came from the knowledge that my daughter is now well-prepared and informed. As Black women in this country, this is a lesson that must be continued.

Theme: silencing the matriarchs: not just spirals, but generations

One of the first theories communication scholars learn about is the spiral of silence. That put in conversation with a cultural-centered approach to health reminds us of the history of culture, especially Black American culture, where sharing one's health issues could mean being separated from the family during enslavement, being fired or dismissed from work, and losing money if there was a lack of benefits. Davis and Jones (2021) posit that the Strong Black Woman image is an archetype embodied by many Black women and characterized by extreme independence, self-sacrifice, and emotional silencing (p. 301; Romero, 2000). They further argue that the same strength that serves as a vital function in Black women's lives causes us to distance ourselves from the ramifications of the oppression we experience; it also has a number of negative implications for Black women including their psychological, mental, and physical health. Having our mothers discuss the tragedies and triumphs in their health helped to amplify the racialized and gendered events of their lives (Figure 8).

Mama Ann: There must be a dialogue to help change the narrative of unspoken things pertaining to our health … Some of these things in my culture dictate my silence in my own health. It takes generations of the stigma, shame, and guilt. You just find it unbearable to speak on.

Asha: Do you remember any of the conversations that you had with Grandma or with MaMaw (Great-grandmother) about cycles or what it meant to grow up as a Black woman or like y'all's health?

Mama Ann: No, like I said, most of those things were unspoken. That's why everybody used to say, “what was said in this house, stays in this house.” And that was the way it was told to me. And nobody expected anything less or anything more.

Asha: So y'all never had a conversation about your cycle, your period, or pads. Did y'all have pads back then?

Mama Ann: Not until years later.

Asha: So you never had a conversation with your mom about your painful cycles? You just went through it?

Mama Ann: Yeah.

Asha: Did she have painful cycles? Or your Grandma (my great grandma).

Mama Ann: No, no. no.

Asha: Any conversations with your aunts?

Mama Ann: Some of my cousins, Yes.

Asha: And do you remember what those conversations looked like when you and your cousins would talk about your painful cycles?

Mama Ann: Yea, everybody talked about the cramps. We called it, The Monthly Reaper because everybody knew we had severe pain and I mean it wasn't the regular pain. We're talking about excruciating pain.

Asha: Listening to my mother call her cycle, The Monthly Reaper, broke my heart but naming our pain, even the silent pain, is a common cultural practice. By name alone, a reaper takes something by force, or a person or machine that harvests a crop. The grim reaper, another idiom, is known as death. Put together, the pain my mother and aunts felt as a result of their hereditary and seemingly genetic disposition to Menorrhagia or abnormally heavy or prolonged bleeding during the menstrual cycle (Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research, 2022) lead my family's matriarchs to compare it to thief of their bodily freedom and even their demise.

Mayo Clinic lists some of symptoms of menorrhagia as “soaking through one or more sanitary pads or tampons every hour for several consecutive hours, needing to use double sanitary protection to control your menstrual flow, needing to wake up to change sanitary protection during the night, bleeding for longer than a week, passing blood clots larger than a quarter, and restricting daily activities due to heavy menstrual flow and symptoms of anemia, such as tiredness, fatigue, or shortness of breath” (2022). Before we had a name for it, we named it; before we knew what it was, we knew how to describe it and the ways it made us feel. The suffering of Black women did not stifle their/our creative ways to name and to heal. However, naming my mothers' pain did not increase her volume in loud healing. Instead, it connected our stories and bond over the invisible and the heavy. So we continue to name it. This for us is the second step in loud healing after naming ourselves, we name our pain and our offenders in hopes of freedom and connection.

Loud healing is a faith-filled call to action

Hope: In my family, the origin story of the spiral of silence as it pertains to health is centered around a deeply rooted belief in religion and curses (Figure 9). Historically, Black people have relied on their faith in God and belief in His power to get them through any manner of wrongs and injustices committed against them, provide healing from physical ailments, and offer comfort in times of mental strife. According to religious study researchers, a curse is “a solemn utterance intended to invoke a supernatural power to inflict harm or punishment on someone or something” (Hachalinga, 2017). My great grandmother was a very religious woman and believed in the power of the tongue. As such, she believed she was cursed with “big legs” because she once spoke disparagingly about another woman who suffered from the same affliction. The curse of the big legs is actually a condition known as elephantiasis. According to the National Organization for Rare Disorders (2019), “Elephantiasis is a condition characterized by gross enlargement of an area of the body, especially the limbs, and is caused by obstruction of the lymphatic system, which results in the accumulation of a fluid called lymph in the affected areas.”

My great grandmother believed it was her fault that the curse also spread to her children. My mother and all of her sisters also suffer from elephantiasis of varying degrees of severity. I also worry about the possibility of inheriting the condition myself later in life. Even though this condition could affect every member of our family, it is not talked about much. In fact, I never heard my grandma, or any of her sisters, ever name the actual medical term for the condition. Great Grandma was a strong, stern woman, and her word was law—because she believed the condition came from a curse and not a bonafide medical condition, it was not to be discussed. It was just something she had to endure for uttering a bad word against another. Although I have never discussed this with my family, my theory is that Great Grandma's adherence to silence about all things health-related was unconsciously passed down to her children and grandchildren. My mother's hesitation to initiate potentially painful conversations about health with her children can be directly attributed to the spiral of silence that began with my great grandmother. My mother and aunts were the first to actually refer to it as elephantiasis rather than “the curse,” and only after Great Grandma had transitioned to the afterlife. It was only then that they started their own process of loud healing by naming the condition what it really is.

Hope: What health issues did grandma tell you ran in our family?

Mama Brigitte: High blood pressure. And of course, our big legs and feet that started with your great grandmother. She always explained to us that she passed the curse on to us. And we were like, Grandma, what do you mean, curse? She would tell us the story of when she laughed at another woman who had big legs and she believed that was how it started. We didn't know any better. She explained to us to never make fun of people. It didn't dawn on me what she meant or how heavy what she was saying was then, until we started getting older. Because when you start looking at people and because we feel something is wrong with them, we make fun of them. The curse gets on you then. So that really opened my eyes. Never make fun of people because it will come back on you.

Hope: Ma, you never told me that. I didn't know Great Grandma thought that way.

Mama Brigitte: Yes I did! Well, I thought I did.

Hope: You didn't tell us she thought it was a curse. Do you think she really believed that it was a curse? Or she was just telling y'all that so you'd be nice to people?

Mama Brigitte: Yeah, she believed it. Her mother. Both of her legs had to be removed. Grandma had the same problem that we had. And she had to lose a leg. Aunt Corrine, same thing, but she refused to let them take her leg.

Hope: But I thought that was from diabetes though, right?

Mama Brigitte: Diabetes was just a part of it. I always remember the rest of it as being the curse.

Theme: like mother, like daughter: turning the mic on

When we started this project, I was thinking about one of the moments in middle school. I think it was middle school because we had Grandpa's brown van. The elderly white nurse at the school was so mean to me every month when I would have to come in and call y'all to come get me because I was hurting so bad. I was so young-−6th grade; I was bleeding so bad and cramping so bad that I would lose my vision and get dizzy. I did not recognize then that these were symptoms of some terrible periods and fibroids because the pain had become normalized in my life. Having a cycle that was not painful would have been out of the ordinary for me.

Asha: One day in particular, I think you and Aunt Shirley came to get me in the van. And even though I was bent over you were always so patient with me when nobody else would believe my pain. You believed me. You would give me some medicine and tell me it was gonna be okay and that you understood. You got me a Sprite or Ginger ale. And even when I was throwing up because I was in so much pain, you were still so patient because you understood what I was going through even at 12 and 13 years old. And those moments stayed with me. I don't think I realized then that you were so understanding about it because you had lived it. You knew my pain before I knew what it was and even how to name it. So thank you mama.

Mama Ann: Oh, you certainly welcome, baby.

Hope: When it comes to passing on the pain, my experience was a little different. I grew up knowing that my mom had a cyst removed from her foot. However, I didn't really know what that meant. Mom used to say that she had a growth on her foot that she would have to get lanced periodically but eventually, it had to be removed surgically. She would always dismiss it as no big deal. So when I developed a cyst on my ovary in college that caused me so much pain, I'd lay in the bed and cry at times, I dismissed it as just a part of life like Mom did. However, when a doctor discovered a cyst on my thyroid during a routine check-up, I couldn't dismiss it. After tearfully lamenting to my mom about the doctor's discovery, to my surprise, she then told me that our family had a history of cysts. In addition to her, my Uncle Dennis and my Aunt Paula had issues with cysts with my Aunt's being in the same place as mine. I found myself angry because if I had known that a predisposition to developing cysts ran in my family, I could have been more informed and prepared for the possible eventuality that I could develop them as well.

Hope: I didn't know that Aunt Paula had cysts, I didn't know that Uncle Dennis had them. I only knew about the cyst on your foot. Why didn't you tell me about this stuff? I could have been more prepared. I was scared to death when I found out about mine.

Mama Brigitte: Well how in the hell do you think I felt? I was scared to death too! (Both laughing) But you know, hindsight, whatever goes on in your body can happen to your kids. Oh, Lord, when you first told me about yours, I asked myself, why did this jump on my child?? Hopefully, it doesn't have to happen to your children. But you do have to talk about these things, but you know, we don't like to. We just don't do it.

Hope: Why don't you like to?

Mama Brigitte: Cause it's sad. You know? Oh, you don't want to see your kids go through that. The worst thing in my life was seeing a bandage on your neck. And you looked all pitiful and in pain. I couldn't take it. I thought to myself “Oh my God, look at my child. She's gotta go through that. Oh Lord.”

Hope: So you don't want to talk about certain things because it's sad if I have to go through it? Too sad to think about?

Mama Brigitte: Yeah, it was. I saw you and was like Oh my God.

Hope: It did look bad. I saw pictures of myself. I was like, oh, oh, I do look bad. (Laughing together)

Hope: I had to first undergo a biopsy to determine if the cyst was cancerous (Figure 10). I can't describe the fear and trepidation I felt watching the doctor approach me with a very, very long needle, aimed at my neck. Once it was confirmed that the cyst was benign and not causing any immediate health issues, I tried to put it out of my mind. However, it didn't like being ignored and grew so large that it looked like I swallowed a tennis ball that got stuck inside my throat. I eventually had to have surgery to get it removed because it was too big. The surgeon told me afterward that they normally use the esophagus as a guide to the midline but my cyst was so big that it pushed my esophagus all the way to the side which meant they had to change course in the middle of the surgery to avoid hitting my vocal cords. My doctors were amazed that I had been able to speak and swallow correctly prior to the surgery. Although the experience was a roller coaster of emotions and uncertainty, it was okay in the end.

Mama Brigitte: Thank God you made it through, you know. You made it through. Amen. I know you have to take medicine for the rest of your life and yes, that's bad but you're here. Amen.

Hope: I've come to realize that it was fear that kept my mom silent about our family's struggles with cysts, not fear for herself, but fear for me and my siblings. Fear that the pain would be passed down to us. For my mother, silence was the better option because that fear was more than she could bear.

Together: We realized in the midst of analyzing our stories that as much as our mothers did not want to pass their pain or their painful narratives onto us, it worked like a family heirloom, moving from generation to generation, hidden and heavy. The pain, however, that was meant to silence us gave us purpose and bonded us with not only our mothers but other Black women with other serious health issues. Their silent secrets were the prescriptions to our healing, and this research worked like a dosage check, moving our words into the tissues of bodies. Additionally, both mothers, with grateful hearts, mention their religious/spiritual affinities in their interviews. We believe that their faithful dispositions worked as an anchor when the tides of health disparities and winds of racism blew them about the oceans of life. They passed down those lessons as well.

Theme: loud healing is visibility—Affirming our mother's stories and rearing

Hope: It must be noted that both daughters felt the need to affirm their mothers' parenting choices throughout their respective interviews. As Black women, who are faced daily with multiple oppressions simply because of what we look like, neither daughter wanted their mothers to carry the additional burden of feeling like they weren't enough. In the snippet below, after asking Mom to describe how she passed information along to my sister and I, I could see that she was getting uncomfortable and responded accordingly (Figure 11).

Hope: So how did you teach Brittany and I about what it means to be a Black woman in America? How has that changed your ideas of what you grew up with? Or has it?

Mama Brigitte: Did I teach y'all anything about being a Black woman??.…Well, I can say that I did the best that I could….(pause)…Oh, it was different. I'm sure. My time growing up wasn't as hard as it is today. Each generation is different.

Hope: Oh, you think it's harder now?

Mama Brigitte: (Scoffs) Oh, yeah, you know with all the problems there are, yes. But hopefully the little bit that you did get from me, helps. Okay. I think I did a good job with y'all. Well sorta. (Laughs nervously)

Hope: Yeah, you did great, Ma. I promise.

Together: (Hope) There were many times during our 30-min conversation that I felt the push, the necessity, to affirm my mother's child rearing of me. While I can acknowledge that, at times, I wished more information was readily given without prodding, I wholeheartedly know that my mother did the absolute best she could based on her own upbringing and life experiences and gave her all for her children. By participating in this project, I never wanted Mom to feel like I lacked anything growing up (because I didn't), so whenever I noticed a bit of insecurity or nervousness on her part, I freely gave my mom affirmations that I could see were a balm to her mama heart.

Asha: I'm so proud of you for talking to me about it though because I know that it takes a lot to even talk about one of these questions. So I thank you for your loud healing. And I thank you for being vulnerable with me and sharing this space with me. And I couldn't have asked for a better mama who gave me a chance.

Mama Ann: Well, I just hope you always have a platform that you can speak on the hard, heart issues baby, okay.

Theme: loud healing is culturally competent—The lessons our bodies taught

(Asha): There were a number of lessons that we learned about being Black women healing from our mothers, but it was the lessons that our bodies taught us beyond the hospital rooms and doctor visits that shaped our health identities. The silence that moved from theme to theme also played a major role in the transmission of information from my MaMaw to my grandmother to my mother to me. Four generations of silent, strong, Black women, whose selflessness cost them blood and strength, found remedies when doctors were unavailable and care was unreachable. For my mother growing up in the 1950–1970s in Deep East Texas, she and her aunts and cousins who all lived in MaMaws house had to get creative with their pain management. It wasn't until 1957, when a Black woman, Mary Beatrice Davidson Kenner, a self-taught inventor created the first sanitary pad (Tsjeng, 2018) (Figure 12).

Mama Ann: What I experienced from an early age of 11 years, no plan or anything was explained. To fear heavy flows, not able to cover yourself, always turning around and looking behind you to see if you have something on you… for your monthly durations as long as 7 more days. Cramps were unbearable, low average pooling clot. I remember years using a 15 pound doorstop on my stomach to just relieve some of the pain and pressure. We had no other way to pay for it. So I would use an iron and heat it up and wrap it in a cloth or a towel and place it on my abdomen. We had no medical treatment at that time. Finally, after years, there were such drugs as Pamprin or Midol - and that too was no delight for anyone. You had very little money to even pay for those two drugs. Doctors had long believed that if you had a child that that would be the answer to many of the problems that women suffered but we still could not get past the dilemma that we face. We didn't have the pads, we had a lot of sheets. I had to have like so many changes and changes of sheets. You would take the sheets and you cut it up in so many different ways. And then you try to sit on it and then the mess would hurt you just so bad. Shoot, it would feel like you were cutting yourself all during the day trying to sit on it. But no, we didn't have any pads like that at all. And it took a long time before we had Kotex, and stuff like that. A long time. And at the time I don't remember us having money like that or anything. We would wash them and then they look like they were clean. You would bleach them and boil them and then you would start all over again the next month and the next month. You start with the same thing all over again.

Asha: How did you manage the pain?

Mama Ann: I would use the 15lbs doorstop and then I would use the regular iron and heat it up on the stove and wrap it in a towel.

Asha: Do you remember any of the stories that we talked about later in life or early when it came to my cycle? I know I hid it for a little while when it first came because I was really embarrassed that I even had one. But do you remember any of the things that you wanted to share with me about my cycle growing up?

Mama Ann: No

We finished my mother's narrative with her admitting that there was nothing else that she wanted to share with me. I believe she shared what we could handle, she supplied the materials I needed to survive, but some information came from other mothers/sources at times. In the end, I know the stories she shared during my maturation was her loud healing because she dared to share what her mother and grandmother did not. She turned her mic on even if the volume was low. That radical act is how she explored new frontiers in healing and offered me care in the interim.

Asha: Do you remember the first time you told the doctor that you were having pain with cramps … that you finally admitted it?

Mama Ann: No, I mean, I was like a real, real real teenager. I mean, I do not remember them. I don't remember seeing a doctor at all, I really don't.

Asha: When did you find out you have fibroids?

Mama Ann: When I was pregnant with Cedric (first born child in 1973 at age 22). I had already graduated from college and everything.

Asha: Did it cause any complications with any of your pregnancies or knowing if you were pregnant?

Mama Ann: That's why I didn't know when I was really pregnant or not. Because they would give me the birth control pill every month but I bled regardless. So they didn't know what was going on. Every month I had a cycle right in the middle of the month no matter what. It would be 3 or more months and we didn't even know you were pregnant because you still had one or two cycles that came that month.

Asha: So you really got some miracle babies because I can only imagine what that does to a relationship.

Mama Ann: Oh Very much so. Very much so.

Asha: Was there any time throughout your life or through your pregnancies that anybody offered you a different treatment plan at all or some type of relief from the pain?

Mama Ann: No

Asha: Not even after you had us?

Mama Ann: A hysterectomy.

Asha: At 40!?

Mama Ann: Yep.

Asha: You're gonna make me cry, mama.

Asha: My mother was not the first young woman to be presented with only one treatment option for her uterine fibroids—a total hysterectomy (Figure 13). At 27 years old, it was also an option given to me when the pain was unbearable and when the doctors at my university student health center could care less about giving me options that met my short and long-term goals (to finish my degree without constant pain, future marriage, and eventually a chance to have children). I went through several brands of birth control to manage the heavy bleeding, similarly to my mother. At one point between 2018 and 2019, I bled for a whole year with only a few days without bleeding. My mother experienced the same phenomena multiple times throughout her life with one only option presented in her treatment plan. It was not until much later did we discuss how constant bleeding impacts romantic, platonic, and social relationships and most of all self-esteem.

Together: The fear of death, perpetual sickness, and unwellness is a cage that has locked away so many families of Black women. That fear is amplified when we struggle to understand how it is that there are less invasive treatments for fibroids than hysterectomies, but lack of access to those treatments mean that Black women receive the more invasive hysterectomy at a rate three times higher than White women, with up to 90% of the procedures among Black patients occurring in the U.S. South (Yurkanin, 2022). In addition, the warranted distrust of medical professionals could cause many Black women to avoid seeking healthcare. Nicknamed the Mississippi Appendectomy because of how common the practice was, Black women would go to the doctor for routine surgeries and wake up to find that they were given an unsanctioned hysterectomy (Early et al., 2021). Learning about the injustice and depravity of the Mississippi Appendectomies sent shivers down our spines; one can only imagine how Black women who lived during that time period felt. However, these types of qualitative studies that transverse academic spaces, encouraging community work, allow Black women safe spaces to have their stories told and their voices heard.

Theme: trusting loud healing—Inspired to leave the mic on and the door open

Hope: As a young girl, reading anatomy books in elementary school, I've always been interested in the human body and knew my career would revolve around some aspect of health. I think the moment that sealed the deal for me was when I gave my younger brothers and sister the sex talk. I was a sophomore in college at the time and a founding member of my school's peer education group—we would frequent different areas of campus where students congregated and engage them in conversations about health and wellbeing. Because of that, I had access to sexual health props. My siblings were at the age that they were starting to have questions about sex and how to be safe. My mom trusted me with the duty to educate my siblings. That was the pinnacle moment for me. I had been used to teaching college students but knew I couldn't present the information in the same way to my siblings. I realized the importance of making sure the message was informative but said in a way that my younger siblings would understand. That was when I truly understood the power of health communication.

Asha: If you can talk to your younger self today, like back in the 1950s and 60s, is there any advice that you would give to your younger self about your health and wellness?

Mama Ann: I don't see anything that changes my outlook on that particular time. I know that that experience alone made me want to be in the health field. I had to do something.

Hope: Okay. So if you could go back in time and talk to your younger self, young Brig. If you can tell your younger self anything that you have learned, any lesson that you've learned about health and wellness, what would it be?

Mama Brigitte: Oh, God, I would tell myself to exercise more, eat less, eat less. That was the number one thing I would tell myself as being Black people, exercise more matter of fact. Get into the gym, workout more. That's the key to everything like that. Also, try not to eat so much pork. We don't realize it until we get older. Oh, it's rough when you hit your 50s you know, you got to be careful. You can't do it like you used to do any more. And if you want to get to 70 or 80, you definitely can't have all that sodium and eat too much.

Hope: There is power in disseminating health information because the way we present a message can influence the choices people make for their own health and the wellbeing of their families. As such, we have a responsibility to do it right. That moment my mother trusted me to help my siblings in such an important way solidified my desire to work in health education and communication.

Conclusion: it's her story to tell

We realized throughout our dialogues with our mothers that our leaky bodies and bloody tales were always connected. Like a generational tale, an heirloom of misery, our own beauty for ashes was our story to tell—no one else's. That is loud healing, empowering each other to tell our own testimonies. Her story is her history, and my story is her legacy. The memory work needed to do this study is also a part of American history and its innovations a part of our futures. The wars our mothers fought may not have been with armies, but they are indeed veterans who have faced battle. Their wounds were bandaged in pads and reusable sheets, and even though we cannot see their scars, they wear them everyday. We have a famous saying in our home that says “you don't look like what you've been through” and in looking at the photographs of the authors and our mothers, I can also harmonize with the choir when they declare its truth. Our mothers do not look like what American healthcare, society, and culture has put them through. They survived to tell their own stories and in that, we shared our own.

Why do these intergenerational stories matter to academia?

This research sought to explore the lived experiences with and about Black American women through multiple generations and in multiple regions of the US. We used duoethnography and photo elicitation to evoke the stories of our mother's lifetimes to see more clearly their health experiences through the decades. Our Black mothers met us with honesty, transparency, and most of all added to our knowledge production of the health disparities felt by Black American women from the 1940s to 1990s and even still today. This research identified a number of themes present in our dialogues through loud healing: (1) quiet lessons borne are from intergenerational trauma; (2) silencing matriarchs occurs in generations, not just spirals; (3) how pain is passed down; (4) the need to affirm our mother stories and rearing of their Black daughter, (5) how these lived experience inspired all of us to work in the healthcare field and in research, and finally (6) ultimately, it is Black women's stories to tell—herstory. These themes resonate with the tenets of Black feminist epistemologies and help us break out of the spiral of silence that had entrapped us for so many years. Instead, our work calls upon loud healing to combat the traditions of masking pain and hurt with a smile, no words at all. Centering our mother's words and naming them as co-authors is resistive and restorative in making sure their stories are shared.

This type of qualitative work is not easy but is necessary for combating years of being shoved to the periphery. Watts (2006) work on feminist-based research within resistance culture found that it is paramount to connect the researcher's role in “truth telling” and the safety while centering ethics and boundaries that was created within storytelling. Understanding the nuances involved within participant narratives provides a unique common identity (Watts, 2006) that revolutionizes research beyond traditional confines, while spotlighting and placing care upon cultural implications that are often missed. While resistance work acknowledges the ongoing concerns of the marginalized within dominant systems (Iqtadar et al., 2020), giving voice [or amplifying voices] to identified matriarchs preserves their identity and captures nostalgia (Batcho, 2021), while reassigns power and authority of their narrative, not often captured within majority-centered research.

We would be remiss to conclude this study without a call to action. While stories such as ours are personal and unique to us, we know that fear, trauma, unease, societal ills, culture, and/or pain has prevented untold numbers of mothers and daughters from achieving their own loud healing. To all of the grandmothers, mothers, daughters, aunts, and sisters reading this study, let our stories embolden you to break free of the shackles of silence. Your voice is a gift.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent was obtained from the individuals and/or their legal guardian/next of kin for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

ASW, HH, and DD contributed to the conception and design of this study, wrote sections of the manuscript, and contributed to the revision, read, and approved the submitted version. ASW and HH conducted the interviews with ARW and BM, while DD worked on coding the conversations. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^Beaumont is about 30 min from Louisiana and its chemical plants while also hosting a collection of chemical plants within the 90 mile radius. This breeds a number of health issues for the poor neighborhoods that are nearest to the plants.

References

Batcho, K. I. (2021). The role of nostalgia in resistance: a psychological perspective. Qual. Res. Psychol. 18, 227–249. doi: 10.1080/14780887.2018.1499835

Bogle, D. (2001). Toms, Coons, Mulattoes, Mammies, and Bucks: An Interpretive History of Blacks in American Films. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Bogle, D. (2015). Primetime Blues: African Americans on Network Television. New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Boylorn, R. M. (2015). Stories from sweetwater: Black women and narratives of resilience. Depart. Crit. Qual. Res. 4, 89–96. doi: 10.1525/dcqr.2015.4.1.89

Brown, K. J., and Gilbert, L. M. (2021). Black hair as metaphor explored through duoethnography and arts based research. J. Folklore Educ. 8, 85–106.

Davis, S. M., and Jones, M. K. (2021). Black women at war: a comprehensive framework for research on the strong black woman. Women's Stud. Commun. 44, 301–322. doi: 10.1080/07491409.2020.1838020

Denzin, N. (2018). Performance Autoethnography: Critical Pedagogy and the Politics of Culture, 2nd ed. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315159270

Dotson, K. (2015). Inheriting Patricia Hill Collins's black feminist epistemology. Ethn. Racial Stud. 38, 2322–2328. doi: 10.1080/01419870.2015.1058496

Durham, A., McFerguson, M., Sanders, S., and Woodruffe, A. (2020). The future of autoethnography is Black. J. Autoethnogr. 1, 289–296. doi: 10.1525/joae.2020.1.3.289

Early, R., Lifson, A., Lucey, D. M., and Jones, M. S. (2021). The sweat and blood of fannie lou hamer. Humanities. Available online at: https://www.neh.gov/article/sweat-and-blood-fannie-lou-hamer (accessed March 13, 2023).

Grant, A. J., and Radcliffe, M. A. (2015). Resisting technical rationality in mental health nurse higher education: a duoethnography. Qual. Rep. 20, 815–825. doi: 10.46743/2160-3715/2015.2157

Hachalinga, P. (2017). How curses impact people and biblical responses. J. Advent. Mission Stud. 13, 55–63. doi: 10.32597/jams/vol13/iss1/7/

Harper, D. (2002). Talking about pictures: a case for photo elicitation. Vis. Stud. 17, 13–26. doi: 10.1080/14725860220137345

Heavey, K., and Jemmott, K. (2020). Cinders: a duoethnography on race, growth and transformation. Can. J. Study Adult Educ. 32, 103–119.

Iqtadar, S., Hern, D. I., and Ellison, S. (2020). “If it wasn't my race, it was other things like being a woman, or my disability”: a qualitative research synthesis of disability research. Disabil. Stud. Quart. 40. doi: 10.18061/dsq.v40i2.6881

Khoo-Lattimore, C. (2018). The ethics of excellence in tourism research: a reflexive analysis and implications for early career researchers. Tour. Anal. 23, 239–248. doi: 10.3727/108354218X15210313504580

Lomanowska, A. M., Boivin, M., and Hertzman, C. (2017). Parenting begets parenting: a neurobiological perspective on early adversity and the transmission of parenting styles across generations. Neuroscience 342, 120–139. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.09.029

Madden, B., and McGregor, H. E. (2013). Ex (er) cising student voice in pedagogy for decolonizing: exploring complexities through duoethnography. Rev. Educ. Pedagog. Cult. Stud. 35, 371–391. doi: 10.1080/10714413.2013.842866

Madlock Gatison, A. (2015). The pink and black experience: lies that make us suffer in silence and cost us our lives. Women's Stud. Commun. 38, 135–140. doi: 10.1080/07491409.2015.1034628

Mair, J., and Frew, E. (2018). Academic conferences: a female duoethnography. Curr. Issues Tour. 21, 2160–2180. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2016.1248909

Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research (2022). Menorrhagia (Heavy Menstrual Bleeding). Available online at: https://www.mayoclinic.org/disease-conditions/menorrhagia/symptoms-causes/syc-20352829#:~:text=Menorrhagia%20is%20the%20medical%20term,to%20be%20defined%20as%20menorrhagia (accessed March 3, 2023).

Mowatt, R. A., French, B. H., and Malebranche, D. A. (2013). Black/female/body hypervisibility and invisibility: a Black feminist augmentation of feminist leisure research. J. Leis. Res. 45, 644–660. doi: 10.18666/jlr-2013-v45-i5-4367

National Organization for Rare Disorders (2019). Elephantiasis. Available online at: https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/elephantiasis/ (accessed 12 March 2023).

Noelle-Neumann, E. (1974). The spiral of silence a theory of public opinion. J. Commun. 24, 43–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.1974.tb00367.x

Norris, J., and Sawyer, R. (2004). “Null and hidden curricula of sexual orientation: a dialogue on the curreres of the absent presence and the present absence,” in Democratic Responses in an Era of Standardization, eds L. Coia et al. (Troy, NY: Educator's International Press), 139–159.

Norris, J., Sawyer, R. D., and Lund, D., (eds.). (2012). Duoethnography: Dialogic Methods for Social, Health, and Educational Research. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press.

Pung, J. M., Yung, R., Khoo-Lattimore, C., and Del Chiappa, G. (2020). Transformative travel experiences and gender: a double duoethnography approach. Curr. Issues Tour. 23, 538–558. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2019.1635091

Romero, R. E. (2000). “The icon of the strong Black woman: the paradox of strength,” in Psychotherapy with African American Women: Innovations in Psychodynamic Perspective and Practice, eds L. C. Jackson, and B. Greene (New York, NY: The Guilford Press), 225–238.

Sawyer, R., and Norris, J. (2015). Hidden and null curricula of sexual orientation: a duoethnography of the absent presence and the present absence. Int. Rev. Qual. Res. 8, 5–26. doi: 10.1525/irqr.2015.8.1.5

Tsjeng, Z. (2018). The Forgotten Black Woman Inventor who Revolutionized Menstrual Pads, VICE. Available online at: https://www.vice.com/en/article/mb5yap/mary-beatrice-davidson-kenner-sanitary-belt (accessed March 13, 2023.).

Violence Policy Center (2021). Study finds Black Women Murdered by Men are Nearly Always Killed by Someone they Know, Most Commonly with a Gun. Violence Policy Center. Available online at: https://vpc.org/press/study-finds-black-women-murdered-by-men-are-nearly-always-killed-by-someone-they-know-most-commonly-with-a-gun-7/ (accessed October, 2023).

Walker, A. C., and Di Niro, C (2019). Creative duoethnography: a collaborative methodology for arts research. Text 23(Special 57), 1–17. doi: 10.52086/001c.23582

Watts, J. (2006). ‘The outsider within': dilemmas of qualitative feminist research within a culture of resistance. Qual. Res. 6, 385–402. doi: 10.1177/1468794106065009

Winfield, A. S. (2022). Body, blood, and brilliance: a Black woman's battle for loud healing and strength. Health Commun. 37, 127–130. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2020.1826656

Yurkanin, A. (2022). Why Do Black Women Get More Hysterectomies in the South? USC Center for Health Journalism. Available online at: https://centerforhealthjournalism.org/our-work/insights/why-do-black-women-get-more-hysterectomies-south (accessed October, 2023).

Keywords: Black women, duoethnography, loud healing, women's health, uterine fibroid, breast cancer, culture, storytelling

Citation: Winfield AS, Hickerson H, Doub DC, Winfield AR and McPhatter B (2024) Between Black mothers and daughters: a critical intergenerational duoethnography on the silence of health disparities and hope of loud healing. Front. Commun. 8:1185919. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2023.1185919

Received: 14 March 2023; Accepted: 27 October 2023;

Published: 17 January 2024.

Edited by:

Victoria Team, Monash University, AustraliaReviewed by:

Rokeshia Renné Ashley, Florida International University, United StatesIccha Basnyat, George Mason University, United States

Copyright © 2024 Winfield, Hickerson, Doub, Winfield and McPhatter. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Asha S. Winfield, YXN3aW5maWVsZEBsc3UuZWR1

Asha S. Winfield

Asha S. Winfield Hope Hickerson1

Hope Hickerson1