- Department of Foreign Languages and Translation, University of Agder, Kristiansand, Norway

Introduction: Metaphor is more than understanding and expressing an abstract concept in terms of a concrete one. Pre-linguistically, it is the conceptual creativity that resides in the entities yet to be expressed. Linguistically, it is the invention that expands the boundaries of words. Contextually, it is the preservation or generation of polysemy that brings about a confrontation of meanings. As such, metaphor is also a universal creative mechanism of semantic innovation and an artful discourse feature. Both Metaphor and Translation Studies, however, have mostly addressed conventional metaphors and professional translators, thereby neglecting students' behaviors when translating creative metaphors, especially at discourse level.

Methods/Aim: The main objective of this task-based descriptive study is therefore to investigate to what extent and how the translation strategies spontaneously adopted by 73 translator students are influenced by local, creative metaphors and by their textual patterning. The analysis of the data showed that while isolated, non-conflictual metaphors did not pose any challenges, the diverse patterns of conflictual ones hampered the translation outcome. At the micro-level, literal and explicitation strategies result in neutral, less connotative renditions. When omission prevails in correlation to metaphor clusters, the target texts appear more condensed, overtly informative, and lack the metaphorical diversity and cohesion of the source ones. As a result, the appealing linguistic jocularity deriving from exploiting metaphors and puns is toned down.

Discussion: Since students tend to avoid creative solutions, these findings will serve as a preliminary discussion on how students' strategic and textual competence can benefit from cognitive-informed, conflict-based inferencing skills by exploiting the metalinguistic nature of creative metaphors and puns.

1. Introduction

More than forty years after the seminal work of the first generation of cognitive linguists, metaphor research is still providing fruitful ground for studying the interrelation between language and thought. Since then, metaphor has been addressed by a myriad of disciplines from different angles. In the midst of this proliferation, the field has now reached the fully-fledged status of “Metaphor Studies.”

However, in the attempt to answer the call for a cognitive commitment by drawing on other disciplines (Lakoff, 1990), the main locus of cognition that can be empirically observed has been at times overlooked. Along with a multidisciplinary stance, the “systematic analysis of linguistic expressions” should lie at the core of Cognitive Linguistics (Gibbs, 1996; p. 42). Moreover, the binary opposition between conventional and novel metaphors has generated a biggest chasm at the heart of the field, leading to the appraisal of the latter as sporadic, extraordinary artifacts.

In opposing rare monosemy (Abass, 2007), metaphor is a universal artful means that expands the boundaries of meanings (Lundmark, 2005; Gan, 2015). If on the one hand novel metaphors create new conceptual boundaries where the older ones have been unset (Ricoeur, 1973), on the other hand they are potential future linguistic commonalities. At times, they can enter common usage and be lexicalized in the dictionary, thereby disguising their nature. At others, they preserve polysemy in the main locus of creativity: sentences (Ricoeur, 1973; p. 100). Insofar as texts “mean something as a whole” (Attardo, 1994; p. 69; Hempelmann, 2017), treating metaphor as a naturally occurring (Semino, 2008), dynamic phenomenon of discourse (Cameron, 2003) lying at the intersection of linguistic, textual, and conceptual factors allows us to investigate how complex meaning relations emerge in translation (Rizzato, 2021).

Along with the centrality and universality of the conceptual nature of metaphor, Translation Studies have inherited the neglection of its creative and textual factors at play in discourse (Schäffner, 2004; Dorst, 2016; Hong and Rossi, 2021; Rizzato, 2021). This is evident both in the bulk of studies addressing (mostly literary) professional translators' behavior (e.g., Jensen, 2005; Meneghini, 2018; Rojo and Meseguer, 2018; Kalda and Uusküla, 2019) and in the somewhat sparse ones that focus on students (e.g., Massey and Ehrensberger-Dow, 2017; Philip, 2019).

1.1. Metaphor, creativity, and humor

Novel metaphors have been largely equated to rhetorical figures and therefore mostly relegated to the backdrop against which Conceptual Metaphor Theory (Lakoff and Johnson, 1980) gathered momentum: the literary realm. As Cameron and Deignan (2006: 672) argue, “cognitive linguists do not generally seek to provide an account of novel metaphor use in non-literary discourse,” mostly because of the apparent entropy of creative, idiosyncratic uses of language that does not align with the systematic motivation of conventionalized metaphors.

Traditionally, linguistic creativity was conceived of as not observable for occurring mostly at the parole level. In the generativist literature, it was then addressed as a natural mechanism of language production, therefore as mostly structural and rules (or principles) governed (Zawada, 2006). Such a view of creativity as creation, however, cannot give account of non-systematic, ad-hoc creations that require forms of momentary, situated cognition (Langlotz, 2016). Moreover, if the generation of syntactic and morphological structures is to a certain extent predictable, lexical creativity is less foreseeable and high-paced. It is not always possible to predict which lexical novelties will go beyond the parole level to become langue. The chief contrast, however, does not lie in the dichotomy sentences-words, as both are constrained by a set of norms and stem from speakers' need to express meanings not available in the standard repertoire (Zawada, 2006). It resides in the opposing forces of semiotic entities, signs, which are closed and finite, and semantic ones, the vehicles of meanings, which refer to the extralinguistic world and are therefore infinite (Ricoeur, 1973).

As preconceptual and prelinguistic, creativity is the need of novelty that discerns the continuum of the reality yet to be expressed via the most economical instrument as possible: our code. As linguistic, it is sensible to context and resides in sentences (Ricoeur, 1973). Under this view, it encompasses a wide range of phenomena which are placed along a continuum where the structural, predictable creation lies at the opposite end of the unpredictable (pre)conceptual creativity that drives it (Zawada, 2006). In accordance with such a view of creativity, metaphor is semantic innovation and discourse feature at the same time. By virtue of being a creative way of conveying messages, it interacts with other discourse mechanisms which mirror “playful human intelligence”, like humor (Langlotz, 2016).

Classical theorists of linguistic humor, who find their pioneer in Attardo, mostly fall back on the theory of Incongruity-Resolution and on Greimas' notion of isotopy, of comprehension as disambiguation (Krikmann, 2009). The former posits that humor relies on the functional ambiguity (Ricoeur, 1973) and consequent incongruity stemming from polysemous language production. However, while polysemy is a feature of both words and sentences, ambiguity is a phenomenon of discourse emerging from the preservation of the former (Ricoeur, 1973). In the following examples:

1. Eliza passed the English exam.

2. Today, the sun is shining.

the first sentence is unlikely to generate ambiguity as it respects the Gricean relevance principle and delivers the information needed to decode the message (Grice, 1975). The second one, on the contrary, might induce the receiver to pause and formulate hypotheses on whether the sender intended the message in the literal, meteorological sense, or in the figurative one. The disambiguation is thus subdued to further contextual information.

Since any type of text can be ambiguous without being humors (Partington, 2009), especially if taken out of context (Attardo, 1994; Aarons, 2017), functional ambiguity was soon deemed as essential but not fully distinctive in humor identification. Conversely, incongruity remains the mainstream parameter. However, not all the humor is based on the incongruous juxtaposition of meanings/words. In Raskin's (1984: 110) famous example:

3. ‘Is the doctor at home?’, the patient asked in his bronchial whisper. ‘No’, the doctor's young and pretty wife whispered in reply. ‘Come right in’.

a more evident script and a more hidden one, the one involving a doctor and the one involving a husband/lover respectively, form semantic networks of both lexical and non-lexical elements (Chiaro, 2017; Navarro, 2019). In this case, the two scripts are not “semantically incompatible” (Attardo, 1994: 133; Krikmann, 2009: 18) or “do not fit with our world view” (Navarro, 2019). By contrast, the membership categorization device in our mind that ascribes activities or characteristics to a group of people, namely to lexical elements (Housley and Fitzgerald, 2002), allows us to see the two personal categories (doctor and husband) as compatible and to understand the joke with such ease.

As ambiguity and possible incongruity nourish other figural speech like sarcasm and irony (Joshi et al., 2015), the specificity of humor might reside in marked and unmarked informativeness (Giora, 1991). Differently from informative texts that reduce the uncertainty of different interpretations, in this forced joke:

4. A: Did you take a bath? A man asked his friend who had just returned from a resort place

B: No, only towels

the unprototypical script of stealing towels is inserted in the set of more prototypical and therefore accessible actions that can happen in a resort frame (e.g. washing oneself). Substituting the second exchange with a more informative answer (e.g. “no, I only took a shower”) would explicate the implicatures, the surprise effect would be hindered, and the joke ruined (Giora, 1991; p. 472).

Like any discourse segment, text jokes present a manifold structure where the presentation of the input is followed by a comprehension mechanism subdivided in prediction, confirmation, and readjustment (if necessary). However, in jokes a surprise effect prevails (Giora, 1991). The punch line “only towels” is in fact a breach of expectations (Veale, 2004). Language communication requires fast processing of information, of context cues, and is dependent on our expectancy grammar (Oller, 1976; p. 4), a hypothesis internal generator underlying productive and receptive language skills. On a broad scale, language processing is a hypothesis making mechanism, as we are constantly monitoring what comes after (Oller, 1976).

By the same token, in the sentence “The first thing that strikes a stranger in New York is a taxi” (Raskin, 1984: 26), the two scripts, experiencing a sudden feeling and being hit by a car, are not utterly incongruous, otherwise the polysemous mechanisms that conventionally equates the experience of an extremely strong emotional state with a physical one (e.g., lightning) would be incongruous as well. In this specific case, it is the distance between the two meanings, along with their conceptual connection, that is emphasized to create the linguistic jocularity. More specifically, the two meanings that are competing are firstly momentarily fused and then separated, before being combined again to cause witty amusement (Kyratzis, 2003).

The disjunctor, the verb to strike, triggers a switch in the script, breaking the linear interpretation of the segment and changing the direction of the comprehension (Aljared, 2017). When the reader stops at the disjunctor, they are compelled to backtrack and revise their interpretation. A connector, the ambiguous term, usually precedes the disjunctor or they can coincide, like in this case, and prompts the script overlapping (Attardo, 1994). On these premises, in most humor the comprehension appears to be dislocated in a subsequent string of text and in time (Attardo, 1994).

While the doctor and the bath examples are types of jokes, the taxi one is a form of pun, the most common type of humor (Kyratzis, 2003). Broadly speaking, a pun is a specific form of humor that exploits the structural characteristics of a language system “to bring about a […] confrontation of two (or more) linguistic structures […]”. These linguistic structures have “more or less different meanings” triggered by “more or less similar forms” (Delabastita, 1996; p. 128).

Being a borderline phenomenon (Krikmann, 2009), puns usually overlap with bridge metaphors, the most common type of indirect metaphor, especially in advertising and headlines. As ludic uses of language, they resemble Leeper's optic illusions that, nearly simultaneously and most probably deliberately, disclose a more basic, concrete meaning, and a more abstract, figurative one at the same time (Nacey, 2013; p. 182). For instance, in the church inscription “Exercise daily. Walk with the Lord” (Nacey, 2013; p. 172), the image of physical exercise is fused with the spiritual mundane one evoked by the prepositional phrase “with the Lord.”

While it is easier to distinguish jokes and non-jokes for the narrative, usually punch-lined nature that generates surprise in the former (Giora, 1991; Dore, 2015), it is not as straightforward to tell a pun and a non-pun apart. The problem is that while surprise and laughter are more quantifiable, the intellectual amusement that characterizes puns is a more elusive concept (Schoos and Suñer, 2020). Due to their common dyadic nature, research has fallen short on drawing the line between metaphors and puns. While a pun is metaphorical if it entails a more concrete and a more abstract meaning, bridge metaphors and puns cannot always be discerned, as the answer would probably lie in the intention of the speaker/writer. In the scarce extant literature on this matter, the emphasis has been put on the domain boundaries, suppressed in metaphor and maintained in humor (Hempelmann and Miller, 2017). Briefly put, humor is not inherently metaphorical, and a metaphor becomes humorous if the speaker, intentionally or unintentionally, brings the attention to the boundaries of the two domains to emphasize their distance and to create friction. If metaphor enhances the similarities, humor plays on differences (Krikmann, 2009) to generate conceptual conflicts.

Polysemy and ambiguity, incongruity/opposition, comprehension delayed; reinterpretation, and disambiguation usually guide the distinction between humor and non-humor. As none of these parameters are devoid of drawbacks, a taxonomy at hand for the present purpose could focus on the semantic/phonological features involved (Attardo, 1994). Generally, puns can rely on morphological, syntactic and lexical features, and can be subdivided into syntagmatic (or horizontal), and paradigmatic (or vertical) puns. In the first both linguistic elements, or sound strings (SS), are present (“A: Where is the rent? B: In my trousers”). In the latter only one SS is visually available and the other one has to be retrieved by the reader (“A: I'm Toulouse-Lautrec. B: Where are you going to lose him?”) (Attardo, 1994; Partington, 2009; Aarons, 2017). On a broader scale, the former is a type of phonological semantic puns, whereas the latter is a phonological syntactic one (Aarons, 2017). In sum, puns can exploit the signifier(s) and the signified (i.e. its polysemy). In the first case, the sound features involved would rely on homonymy (same wording and sound), mostly homography rather than homophony solely, and rarely on paronymy (similar sounds) (Vandaele, 2011).

1.2. Metaphor, translation, and specialized discourse

The research traditions of metaphor and translation are deeply intertwined. On the one hand, translation has been investigated, at times too simplistically, in metaphorical terms (St. André, 2017). On the other hand, the way metaphors are rendered in another language has revealed the underlying cognitive processes at play when translating. In concert with the major trends in Translation Studies, metaphor translation research has in turn gradually disengaged from the purely linguistic-level of equivalence-based approaches (Newmark, 1988), to extensively delve into the pragmatic notion of skopos and to marginally disentangle the fabric of discourse (Dorst, 2016).

Two shifts have proved to be particularly advantageous in the study of metaphor translation: the descriptive and the cognitive ones. As it is primarily conceptual and linguistic at the same time, rather than rhetorical solely (Lakoff and Johnson, 1980), metaphor has no longer been addressed as a prospective translation problem in prescriptive approaches (e.g. Newmark, 1988), but as a solution in descriptive paradigms, therefore in retrospection (van den Broeck, 1981; Schäffner, 2004; Toury, 2012).

Mandelblit (1995) was among the first scholars to adopt the cognitive vantage point on metaphor translation by stressing the importance of shared (SMC) or different mapping conditions (DMC), where the latter might incur higher cognitive load and conceptual shifts. As the corroboration of the theory provided by Al-Zoubi et al. (2006) points out, even in the case of shared conceptual conditions, different linguistic instantiations can occur. For instance, while English and Italian share the mapping conditions of TIME IS MONEY, in Italian time cannot be spent as if it were money, unless a bizarre calque is chosen when translating (Rizzato, 2021). Conversely, the conventional metaphor to waste time poses no challenge when rendered from English into Italian, as the concept is derived in both languages from to waste money. In such a vein, translating conventional metaphors means to transpose the commonalities through which conventional metaphors address reality, while it becomes a matter of reproduction of semantic conflicts in novel ones (Prandi, 2012).

The creative metaphor in Emily Brontë's verse “winter pours its grief in snow” (Prandi, 2012; p. 149), for instance, generates a conflict in our mind where the image of winter pouring liquid in a container is competing with our common understanding of seasons. In order to carry out such an action, winter needs to acquire anthropomorphic features, and, at the same time, grief needs to be transformed into a more tangible entity, into a liquid that can flow in its container: snow (Prandi, 2012). When tension arises from preserving polysemy, it originates from conventional metaphors too, as novel metaphors seldom stem from lexicalized ones. A case in point is the above-mentioned taxi example (“The first thing that strikes a stranger in New York is a taxi”), where the verb to strike generates a semantic contextual tension from punning on a conventional, bridge metaphor. Here the two meanings, the more concrete and the more metaphorical one, are contextually concurrent and, as complex, need to stretch into the fabric of discourse to be framed (Prandi, 2017).

Bridge metaphors, puns and their overlapping (conflictual metaphorical polysemy henceforth) are more than play with words and sounds, they are play with ideas in a cooperative meaning construction. When framed into discourse length, any linguistic form acquires a communicative intent (Widdowson, 2007). If the addressee is in the same paratelic, non-serious state (Navarro, 2019), the text becomes dialogic (Bakhtin, 1982). Differently from forced humor where the intentions of the first speaker are compelled into a different interpretation by a second one, in written puns (or in conflictual polysemy in general), the reader is called to indulge themselves in ending the lexical conflict they are presented with (Attardo, 1994; Partington, 2009). In essence, conflictual meanings signal the parts of the text on which the reader should linger longer. If the pun is solved, a virtual intimacy bonds the sender and the receiver (Zawada, 2006). This is especially so for homonyms which disguise their nature and could lead the most attentive of the readers to think of themself as the only ones able to spot them (Bartezzaghi, 2017).

These assumptions might attest to the extensive use of conflictual metaphorical polysemy in many types of specialized texts, especially advertising and tourism discourse. In inflight magazines, for instance, a hybrid genre combining both, the potential tourist-client is guided, while already traveling, into a fictional world where the potential future destination is depicted as an agent, mostly through movement verbs (Cappelli, 2007) and metaphors. While becoming an active participant, future tourists are infotained, informed and amused at the same time (Maci, 2012; Khan, 2014; Dorst, 2016; Djafarova, 2017).

In preserving conflictual metaphorical polysemy, what tourism advertising exploits is not the indirect use of persuasive meanings, but the ostentation of the playful, cognitive overload required in the comprehension process. If comprehension is the reduction of multiple readings, jokes require higher reading times (Giora, 1991). Although reception and comprehension have long been regarded as synonyms, lexical conflicts are not merely receipted but constructed in an active form of meaning making. After the mere reception of the message, when letters and words are automatically decoded, comprehension proper emerges from the interaction between the message received and the recipient's world knowledge (Royer and Cunningham, 1981). This process thus generates a mental representation in our mind enriched by the world knowledge that has become part of the comprehended message.

2. Materials and methods

The bulk of studies addressing metaphor translation is mostly descriptive, corpus-based, and product-oriented (Rosa, 2010). Furthermore, considering the significant scholar attention directed to professionals and conventional metaphors (e.g., Prandi, 2012; Sjørup, 2013; Hewson, 2016; Jabarouti, 2016; Kalda and Uusküla, 2019), student translators' behavior and novel metaphors are still not sufficiently addressed (some exceptions being Jensen, 2005; Massey and Ehrensberger-Dow, 2017; Nacey, 2019; Nacey and Skogmo, 2021), especially in relation to discourse (perhaps with the sole exception of Figar, 2019).

To remedy these shortcomings, the theoretical framework of Descriptive Translation Studies (Toury, 2012) is in this study combined with cognitive approaches to metaphor translation. The aim is therefore twofold: to investigate the strategies adopted by student translators when addressing creative metaphors and to discuss whether and how local and textual metaphors have a different bearing on the translation task. While we cannot directly observe metaphorical reasoning in the mind (Gibbs, 2017; Steiner, 2021), the translation strategies adopted can be interpreted as the tangible indicators of intangible, mental processes (Lörscher, 2005; p. 599; Chesterman, 2020; p. 32). Going beyond a mere product-oriented analysis, a process-oriented discussion of the way metaphors are perceived is also built upon the data collected through a retrospective report.

The sample examined is composed of 73 Italian students of a BA in translation and presents an intermediate level of English proficiency. Since students' specialization was translation of tourist texts from English into Italian, their L1, the material used for the data elicitation consists of 5 short texts taken from EasyJet's inflight magazine Traveler. It is important to stress that the students did not receive explicit training on how to identify metaphors and translate them, nor were they previously exposed to the metaphors targeted in this study. The rationale is that the way students spontaneously deal with novel metaphors might shed light on whether and how creativity needs to be explicitly addressed in Translation Pedagogy.

The texts were purposely selected for being highly metaphorical in nature and for presenting both isolated non-conflictual metaphors (N = 31) and conflictual ones clustered in other textual patterns (N = 28) (Cameron, 2003; Dorst, 2016). This way students would be mainly challenged by a varied typology of individual and patterning metaphors rather than other lexical, textual or pragmatical features (Nacey and Skogmo, 2021).

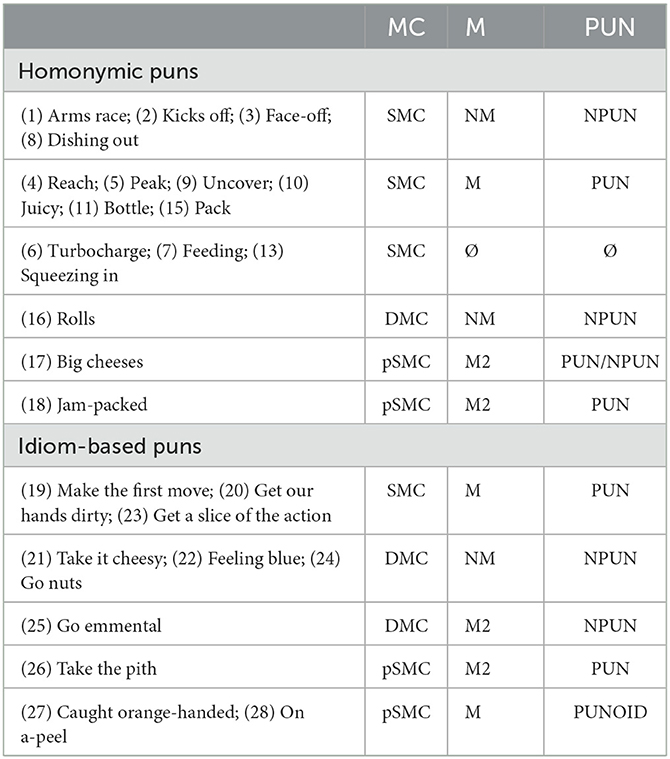

The non-conflictual metaphors include mostly prepositions and expressions like behind the scenes, rumbling and get in Text 1, comes and DNA in Text 2, matching and panels in Text 4. The conflictual ones can in turn be subdivided into homonymic (N = 18) and idiom-based puns (N = 10), the latter relying on paronymy via substitution (take it cheesy or take the pith), insertion (go emmental), extension (Feeling blue? There is a cheese for that) or alteration (get off on a-peel) (Partington, 2009). Since the classification of conflictual metaphorical polysemy explained in paragraph 1.2 is not devoid of problems, the bridge metaphors found in the texts will be treated as potential puns.

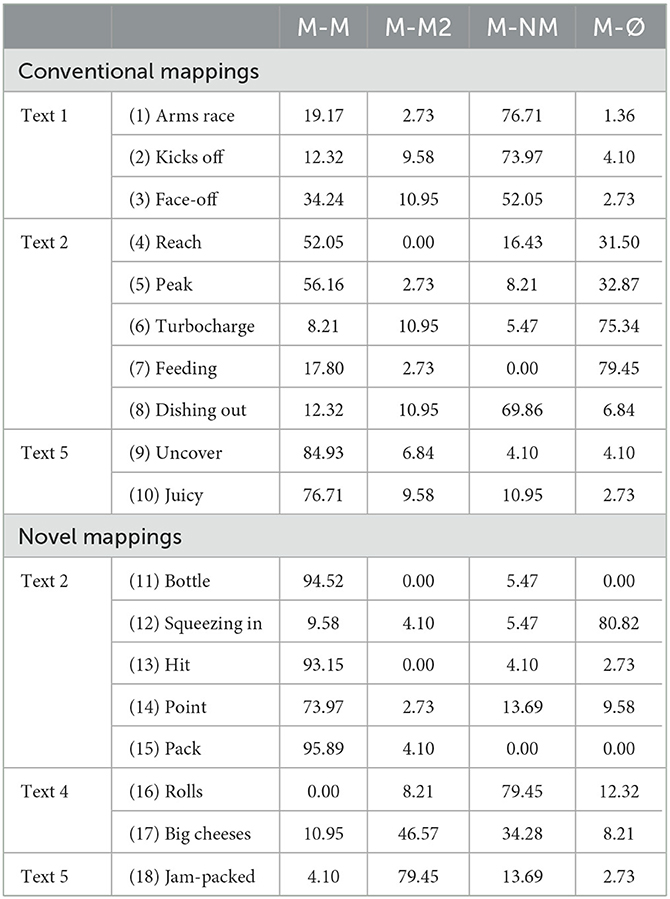

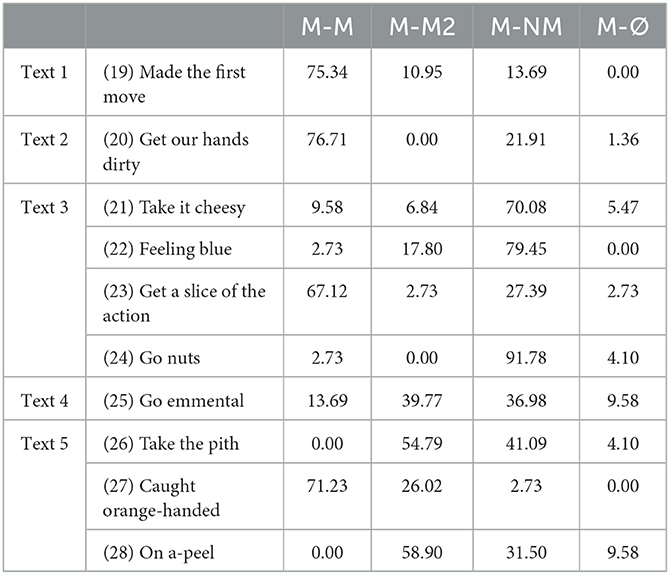

While the homonymic puns pivot on both conventional mappings, if a more concrete and a more abstract meaning is documented in the dictionary, and on novel ones, if the extension of the meaning of the word or expression is contextual (see Table 1), idiom-based puns stem from conventional metaphors (see Table 2). In the former, the tension arises between the conventionalized meaning and the contextual one (Samaniego Fernández, 2002), in the latter punning consists in de-automatizing the figurative meaning and revitalizing the literal one (Kyratzis, 2003). However, the metaphors based on conventional mappings can also bring about conflictual polysemy in a specific context of use. For instance, the adjective juicy in uncover a juicy crime (see Text 2 in Appendix B) usually presents two conventionalized meanings: being full of juice and being interesting. In this context, it is unusually juxtaposed to a theft of oranges, evoking the in absentia image of spilling orange juice but referring in presentia to an interesting event. The same can be inferred for bottle, as usually bottles contain liquids, not karma.

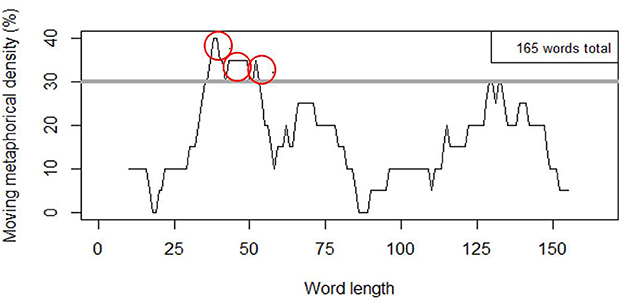

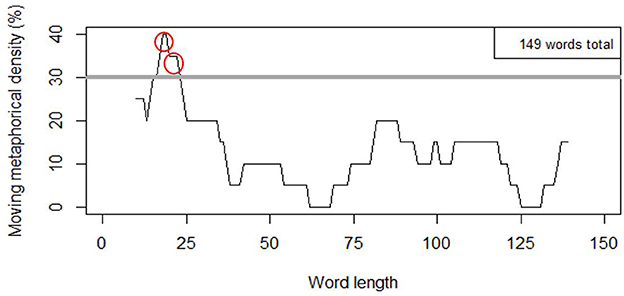

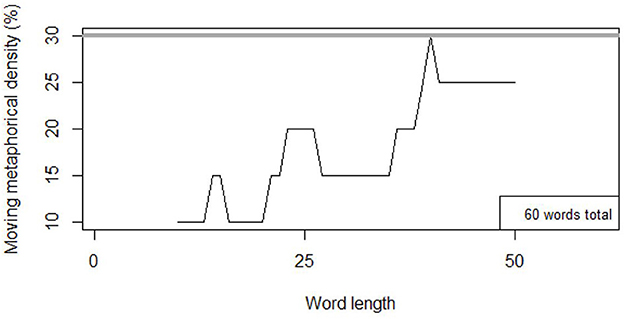

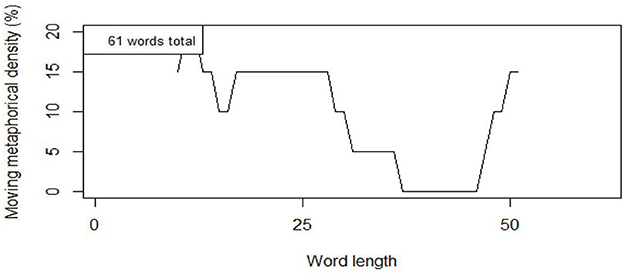

The individual conflictual metaphors identified depict feelings, events, and choices by drawing predominantly on two metaphorical themes: MOVEMENT (in the form of WAR and SPORT) and FOOD. These themes are locally interrelated and give rise to clusters of metaphors aiming at preserving the coherence of the text (Kimmel, 2010). As a discourse-oriented approach to local metaphors can be operationalized if the investigation starts from the latter (Dorst, 2016), first individual metaphors were manually identified through the MIP(VU) method (Steen et al., 2010), then clusters where discerned by calculating the Moving Metaphoric Density (MMD). In this cumulative frequency procedure (Pollio and Barlow, 1975; Cameron and Stelma, 2004; Nacey, 2019), the total number of metaphors is divided by the arbitrary number of 20 (the interval) and multiplied by 100. The MMD is then marked on the midpoint of progressively longer intervals (1-20; 2-21; 3-22; etc.). However, the presence of multiple related metaphors in the same discourse is not always a cluster, which is instead recognized as such in relation to its surroundings, as a sudden increase in the MMD (>30%) (Cameron and Stelma, 2004; Littlemore et al., 2014; Dorst, 2016; Nacey, 2019). When visually displayed (Figures 1–5), this procedure showed significant bursts of metaphors (Cameron and Stelma, 2004) occurring at the beginning of Text 1 and 2 (see Appendix B).

Since MIP(VU) can mostly identify lexicalized metaphors, it can only marginally detect novel ones. If the expression does not present a more concrete, basic meaning in the dicitonary (MacMillan Dictionary, 2023), it cannot be considered metaphorical. In the case of bridge metaphors and puns, however, a more concrete meaning is oftentimes realized contextually. Cases in point are jam-packed and some of the idiom-based puns that could not be marked as metaphorical (i.e. cheesy, go nuts, go emmental, caught orange handed and a-peel). Consequently, the MMD of the three last texts is higher than what the histograms show.

Whitin the clusters, different topical patterns (Cameron and Stelma, 2004) tend to intertwine and revolve around the two metaphorical themes identified (Dorst, 2016). For instance, arms race, the pun in the title, is later repeated in the body of Text 1 (Dorst, 2016) where the theme of WAR/SPORT is extended through the lexical items kicks off and face-off. In line with Figar (2019), Text 1 emulates the cluster dynamicity typical of marketing discourse. In this text, CONFLICT metaphors are employed to bring the reader into the action and to guide them to see arms race as a “race of arms”. Moreover, this initial WAR expression (arms race) is mixed with SPORT metaphors (kicks off, face-off and made the first move) in the body of the text. While WAR metaphors frame a particular representation, SPORT ones extend it (Koller, 2003).

Intertextually, we find another SPORT metaphor in Text 2: reach peak smugness. While the twofold metaphor WAR/SPORT (Koller, 2003) recurs also in Text 2 (hit, point), the FOOD theme is the most recurrent one as it refers to different topics in 4 out of 5 texts: the smoothie that is good for the planet, and for our conscience too (Text 2); the vegan cheese (Text 3); the cheese festival (Text 4) and the theft of oranges (Text 5).

Besides metaphor patterning, other translation challenges can be posed by the presence of SMC (e.g. kicks off; face-off ), partially SMC (e.g. big cheeses, jam-packed, take the pith) or DMC (e.g. rolls; go nuts; take it cheesy) and by conflictual metaphorical polysemy (homonymic and idiom-based puns). To classify the metaphors the students opted for when completing the task, MIP(VU) was also adapted to the Italian translations provided by the informants by using appropriate dictionaries for the target language (i.e. Treccani and Sabatini Colletti) (Treccani, 1929; Sabatini and Colletti, 2004). The strategies used were therefore labeled through Toury's framework which presents the potential benefits of considering renditions that enrich the target text with metaphors absent in the source one (see strategies 5 and 6) (Toury, 2012):

1. Metaphor into same metaphor (M=M)

2. Metaphor into different metaphor (M-M2)

3. Metaphor into non-metaphor (M-NM)

4. Metaphor into zero (complete omission) (M-Ø)

5. Non-metaphor into metaphor (NM-M)

6. Zero into metaphor (addition, with no linguistic motivation in the source text) (0-M).

Moreover, to examine the translations of the puns, the strategies were further classified through Delabastita' guidelines (1993):

1. PUN > PUN: the pun is translated if its polysemy and homonymy are preserved;

2. PUN> PUNOID: the pun is rendered into a pseudopun by using another rhetorical device (e.g. rhyme, alliterations, repetition, or irony);

3. PUN>NPUN: the pun is omitted.

As a compensation for the loss in the latter two strategies, addition (Delabastita, 1993) by permutation in previous or subsequent segments of the text (Holst, 2010) can occur in the form of NONPUN>PUN or ZERO>PUN.

Since neither Toury's nor Delabatista's frameworks can provide information about students' awareness of the local and textual metaphors (Maalej, 2008; Nacey and Skogmo, 2021), the data collected on the product (i.e., multiple translations of the same metaphor) is corroborated with delayed online evidence of possible mental processes. Two days after the translation task, completed in 2 h by using both offline and online tools (like dictionaries or search engines), the students were asked to self-assess the challenges faced. Through open-ended questions, they were instructed to reread the texts, report the words or phrases they considered difficult and explain why.

In the texts selected, most metaphors are indirect. At times, metaphorical expressions can be signaled by expressions like kind of or sort of (like in the case of the size of Greenland in Text 1). At others, punning on bridge metaphors and textual patterning can also function as signaling, as invitations to tune the brain into a figurative mode (Nacey, 2013). However, this does not guarantee that a metaphorical textual representation (Tian, 2020) is at play in the participants' minds.

3. Results

The analysis of the translations, presented thoroughly in Appendix A, revealed that non-conflictual metaphors, which are neither clustered nor interrelated, posed no challenge in the translation task, as they were all rendered metaphorically using the strategy M-M. Eight of the conflictual metaphors presented in Table 2 (reach, peak, uncover, juicy, bottle, hit, point, and pack) were also translated adopting the same strategy. These encouraging results could initially imply that students tried to preserve the metaphorical nature of the addressed items. However, the non-metaphorical translations used for the lexemes (1), (2), (3), and (8), notwithstanding the presence of a conventionalized, highly accessible counterpart in the target language, might reveal that the isomorphic strategies are actually mirroring a direct transfer (Holst, 2010). The seemingly automatic preservation of contextual (conflictual) meaning in combination with similar mapping conditions can in fact spontaneously produce metaphors (Gebbia, forthcoming). For instance, uncover juicy crime was perhaps rendered as scoprire un crimine succoso by selecting the first accessible meaning of each component.

Seemingly, the literal strategies used for (1), (2), (3), and (8) reveal the tendency to neutralize the metaphorical charge of the expressions by choosing a less connotative sense that successfully gets the message across. For arms race, the WAR expression corsa agli armament/alle armi was disregarded in favor of the more neutral competizione (backtranslation: competition). Kicks off was rendered as inizia/ha inizio (“begins/has begun”). The alternative calcio di inizio, chosen by the 12.32% of the sample, changed in turn the syntactical structure of the sentence but preserved the SPORT domain by conveying the image of the first kick that signals the beginning of a soccer game. Likewise, face off was translated as confronto/scontro in lieu of a sportive faccia a faccia, while dishing out was rendered as consegnerà/darà (backtranslation: will give) instead of servirà, where only the latter comes from the FOOD domain (Gebbia, forthcoming).

The predilection for an explicitation micro-strategy (Holst, 2010), however, is detrimental to the conflictual metaphorical polysemy evoked by the texts both locally and textually. The clusters at the beginning of Text 1, for instance, rotate around the ACTION verbs/nouns arms race, kicks off and face off, which are not only play with words but also on words as arms, kicks, face stem from the domain of BODY PARTS, usually involved in WAR or SPORT EVENTS. Ultimately, not preserving them in the translation process results in overlooking the communicative effect of the text (Gebbia, forthcoming).

By contrast, the predominant micro-strategy used in correspondence to the clusters of Text 2 is deletion (M-Ø). As Table 2 shows, although the majority of the sample (75.34% and 72.60%) preserved the metaphors (4) reach and (5) peak, a high percentage chose to delete them. This tendency increases with (6) turbocharge and (7) feeding, despite the presence of shared mapping conditions in Italian that could have favored the translation outcome. While literal translations are usually regarded as renditions close to the original, omission is considered a more creative strategy departing more extensively from the source text (Nugroho, 2003; Holst, 2010; Ageli, 2020). However, in this case, omission might indicate a compensation mechanism for the hampered comprehension caused by the clustering of metaphors. By means of example, these students' translations:

Thought you'd reached peak smugness by squeezing in your five-a-day? What if you could turbocharge that glow by feeding your conscience too?

(S12) Avevi pensato di raggiungere il massimo del compiacimento mangiando tutte le tue 5 porzioni di verdure giornaliere e nutrendo la tua coscienza? (backtranslation: Did you think you reached the peak of smugness by eating all your 5 portions of vegetables and feeding your conscience?)

(S23) Mangi 5 porzioni di verdure al giorno? E se potessi nutrire anche la tua coscienza? (backtranslation: Do you eat 5 portions of vegetables a day? What if you could feed also your conscience?)

(S39) Mangi molte verdure? E se potessi mettere il turbo anche alla tua coscienza? (backtranslation: do you eat a lot of vegetables? What if you could turbocharge your conscience?)

(S54) E se potessi raggiungere il limite delle 5 porzioni giornaliere più velocemente nutrendo la tua coscienza?” (backtranslation: What if you could reach your five-a-day faster by feeding your conscience?).

Result in condensed, paraphrased sentences that appear to have the sole aim of expressing the main message of the passage.

Differently from homonyms that mostly occur in the clusters at the beginning of Texts 1 and 2 (see Supplementary Table 4 in Appendix A for an overview of their translations), the idiom-based puns appear in shorter texts with a narrative structure that emulates the scripts typical of jokes (see Supplementary Table 5 in Appendix A). This is especially true for Text 5 where the narration depicts Seville oranges as so delicious to be object of a criminal action. The story also takes an unexpected turn with the punch line “the thieves will no doubt (wait for it) get off on a-peel,” which gives rise to a catchy and humorous ending.

While the presence of homonyms is concealed in the fabric of the texts (Jared and Bainbridge, 2017), idiom-based puns might be easier to notice, especially in the case of structural alterations (e.g. the aforementioned eye pun get off on a-peel). The predominance of M-M and M-M2 translations for metaphors 19, 20, 23, 27, and 28 might thus lie in these assumptions.

As it stands, (19) made the first move, (20) get our hands dirty and (23) get a slice of the action could also be instances of direct transfer, since the counterpart of the former two idioms is highly accessible in Italian. Similarly, a simple transposition of the compositional meaning of get a slice of the action generates a metaphor in the target text. The creative renditions of (25) go emmental, (27) caught orange-handed and (28) on a-peel, in turn, might be indicative of the activation of the metaphor device. Although rendering go emmental as imbufalirsi substitutes craziness with anger, it similarly creates a conflictual polysemy in the target language that exploits an Italian type of cheese, mozzarella di bufala, derived from a subtype of bovines. An extended idiom was instead used for the altered one caught orange-handed, which was translated as colti con le mani nel sacco (di arance), maintaining the image of the oranges and the metonymy THE HANDS STAND FOR THE CULPRIT. In turn, avranno salva la buccia/la pelle (backtranslation: will have their skin saved) does not maintain the domain of LAW, thereby changing the metaphor (M-M2). More specifically, buccia metonymically refers to the skin of a fruit, while pelle to the life of a human being.

The same strategy was used for the paradigmatic pun (26) take the pith, altered in its structure by substituting fifth with the paronymic pith. In this case, arrivare al succo o al nocciolo does not preserve the LAW domain of the expression in absentia but renders the idea of the essence of a fruit. Yet, a vast majority of the sample (41.09%) rendered take the pith literally. Perhaps on the face of different mapping conditions, similar challenges were probably posed by (22) feeling blue and (24) go nuts. The idiom Feeling blue? in Text 3 is extended and complemented by the exclamation There is a cheese for that. Here, the color is not only suggesting a sad feeling but is also indicating the marbled patterns of molded cheeses. In Italian, fermented cheeses are oftentimes referred to as “blue”, but the color does not assume emotional connotations. Therefore, it was translated mostly literally as ti senti triste? (backtranslation: are you feeling sad?) and only marginally metaphorically (M-M2) as ti senti giù?, which in turn relies on the spatial metaphor SAD IS DOWN. As for go nuts, probably forged by relexicalization (i.e. acquisition of new meaning) (Partington, 2009) on the same structure of go global/green, it was rendered as scegli le noccioline, neglecting the image of becoming extremely excited and preferring the sole one of “choosing nuts”, therefore a vegan cheese.

Relexicalization, extremely common in most phraseplay, is also active in the altered idiom (21) take it cheesy. After the original idiom (take it easy) is brought back to its multicomponential nature where each word is processed individually, it is delexicalized to generate a new expression that does not virtually attain any new meaning (Partington, 2009). However, take it cheesy, the expression in presentia, shares more meaning with the expression in absentia (take it easy), while conveying the feeling of cheese. This linguistic illusion enables our brain to adopt a stereoscopic or gestaltic vision and to perceive two meanings concomitantly, one in the foreground and one in the background (Giora, 1991; Nacey, 2013).

Since English and Italian are mostly conceptually close but syntactically and phonological anisomorphic (Ozga, 2011), paradigmatic puns based on paronymy (i.e., take it cheesy, go emmental, take the pith, orange-handed and on a-peel) might pose a translation challenge. While in most puns rendering both the content and the duality of the original pun can be a challenge (Chiaro, 2010), preserving the fourfold structure of paradigmantic puns based on paronymy is an even more ambitious, at times unrealistic, goal to attain as it would mean to maintain the element in presentia, the one in absentia and their respective semantics.

As Table 3 shows, the translation of metaphors was also hindered by different mapping conditions. For instance, not only does (16) rolls convey the image of something arriving on wheels and in large amount, but it could also refer to cheese rolls. While this verb was mostly rendered as arrivare (79.45%) (“to arrive”), the only metaphorical attempt is represented by substituting the original image with the one of lending a ship in approdare (8.2%).

Generally, preserving the metaphor results in preserving the pun as well. As metaphors (15, 16) and (24) show, changing the metaphor (M2) can also maintain the pun if the source and target language share similar mapping conditions. This is not the case for (25) go emmental in its mostly adopted rendition uscire di testa (backtranslation: go out of own's head), which preserves the meaning of becoming excited but not the type of cheese. As for big cheeses, this compound can be rendered in Italian as either pesci grossi or as pezzi grossi. Both these metaphors convey the metaphor IMPORTANT IS BIG but only the latter creates a pun as pezzo, a “piece” of something, could stand for a piece of cheese, while pesci (“fish”) clearly cannot.

Like big cheeses, jam-packed is also based on partially SMC as the counterpart stracolmo is grounded on the same image schema of CONTAINER but lacks the idea of a jam encapsulated in the etymology (Hoad, 1996). In turn, a punoid is generated through the insertion of a parenthetical explanation in colti con le mani nel sacco (di arance) (backtranslation: caught with one's hands in the sack of oranges) offered as translation of metaphor (27). Similarly, the rendition of the eye pun get off on a-peel as avranno salva la buccia/pelle (backtranslation: they will save their peel/skin) preserves the image schema of the CONTAINER (skin), that metonymically stands for someone's life, but omits the formal feature, therefore generating a punoid.

Lastly, it is surprising to note that although most of the puns found in the clusters were reported as challenging, students did not highlight their figurative charge as the main reason for the difficulties faced while completing the task and explained that in most cases (87%) they could not find the correct contextual meaning in the dictionary. Another case in point is the fact that no student adopted the last strategy in Toury's framework and did not try to compensate for the loss of metaphoricity in other parts of the text. When the reproduction of the entertaining function of the source text is not as straightforward, compensation could actually constitute a valuable functional approach (Chiaro, 2010).

These findings add evidence to the hypothesis of direct transfer underlying the renditions that maintain the metaphorical charge of some of the conflictual expressions. Despite their creative and deliberate nature, local puns and their patterning did not disclose their metaphoricity. The questions thus arise of how students can be taught to identify conflictual meanings and of whether cursory or sporadic instances of individual invention can become the norm in the translation classroom.

4. Discussion

Despite the directionality of the task, the sample showed an inclination to explain puns, rather than translate them. At the micro-level, this explicitation strategy is reflected in the predisposition toward literal translations that predilect the more neutral, less connotative meaning. In a given context, we are primed to prefer an interpretation over another one (Giora, 1991). When translating from the L2 into the L1, however, the literal meaning of a figurative expression might exert a negative priming effect (Saygin, 2001) in the comprehension process and might hinder the inferencing mechanism essential in decoding conflictual metaphorical polysemy.

Being predominantly engaged in a sense-oriented approach (Lörscher, 2005), the students' semantic translations (Ageli, 2020) generate, at the macro-level, informative, clearly understandable texts. This isomorphic behavior, however, fails to reproduce the pragmatical effect of the source texts, as not preserving the local metaphors is detrimental to the textual persuasive function. If on the one hand, the explicit meanings are successfully conveyed, the implicit ones are lost and the communicative, appealing effect is toned down. As a result, the target texts appear simpler than the original one in terms of lexical diversity and of the dialogic nature of the metaphors. In other words, students' textual representations (Tian, 2020) do not appear metaphorical in the main, as omitting local metaphors or changing semantic domains results in a loss of the original metaphorical themes.

As ambiguous combination of two meanings based on similarity of sound/form, puns trigger a conflict in the recipient's mind. As such, puns are cognitively interesting, or difficult to decode and translate. Indeed, depending on the degree of entrenchment of its meanings and on the encyclopedic and lexical knowledge that the recipient possesses, the disambiguation process might not be as automatic for non-native speakers (Lundmark, 2005). Moreover, because of the phonological anisomorphism of English and Italian, preserving both the formal and semantic features of conflictual metaphorical polysemy could be an unattainable goal (Chiaro, 2017). This is probably why students mostly preserved the meanings of the puns and rarely maintained both the sign(s) and the signifier(s). This was especially so when paronymy was at play (take it cheesy, go emmental, take the pith) or it interacted with alteration (on a-peel).

Perhaps out of the fear of departing too much from the original text, the students did not venture into possible creative renditions. Only a minority of the sample tended to create metaphors out of novel mappings, whereas the majority relied more heavily on conventional ones. Translations like braccio di ferro (backstranslation: arm wrestling) for arms race, ripieni di marmellata (backtranslation: full of jam) for jam-packed or prendila con un cheese (backtranslation: take it with a “cheese”, that is a smile) a bilingual pun that preserves both the form and meaning of take it cheesy, are rare exceptions. This is in line with Atari (2005) and Jensen (2005) who found that students tend to avoid knowledge-based strategies in favor of language-based ones requiring a less cognitive load, namely a less articulated inferencing mechanisms.

When humor “does not travel well” in the translation process (Chiaro, 2017; p. 414), the combination of linguistic and cultural specificity of jokes or witticisms constitute the major obstacles to a functional translation. On the one hand, humor is generated by the combination of wit on words, which relies on language, and wit on facts, which rely on a complex repertoire of world knowledge (Chiaro, 2017). On the other hand, humor appreciation is culturally dependent and what is considered amusing in a language/culture might be less so in another. Students' L2 and L1 proficiency, along with their encyclopedic knowledge or cultural competence, could thus contribute to the predilection for more creative strategies and, as such, could be objects of future investigations.

Differently from linguistic creativity, creativity in translation is to a certain extent constrained by the local and global features of the source text. Therefore, it should be object of explicit training (Rojo and Meseguer, 2018). Moreover, when creativity emerges from the conflictual meanings evoked by metaphors, it is subdued to metaphor competence, to the ability to comprehend and use metaphors in a language, in this case in L2 (Danesi, 1992; Littlemore and Low, 2006). As Table 3 showed, puns can be maintained if the metaphor they exploit is preserved or recreated as well.

While cognitively oriented approaches have been proved to be beneficial to the translation of metaphors (Hanić et al., 2016), Conceptual Metaphor Theory solely (e.g., Jabarouti, 2016) cannot consider the complexity of local and textual mechanisms at play when bridging literal and figurative meanings. While in some cases a conceptual metaphor may motivate linguistic expressions (like KARMA IS A LIQUID which motivates bottle good karma), in other cases it is a matter of underlying image schemas (such as the CONTAINER that motivates jampacked vehicles) or of interacting semantic domains (e.g., SUSTAINABILITY, GOOD KARMA and FOOD in Text 2 or CRIME and FOOD in Text 5). As seen earlier, interacting metaphorical themes, rather than overarching conceptual metaphors in the form of A IS B, emerge at the discourse level (MOVEMENT AND FOOD).

Combining a conflict-based paradigm with the main tenets of metaphor competence would in turn address the pragmatical competence essential when translating semantic tensions (Vandaele, 2011; Rizzato, 2021). After explicit training on the dialectic of metaphors, translator students can learn to make informed, creative choices, locally and consequently textually, if the improvement of their strategic sub-competence (PACTE) follows Hewson' three stages 2016. The preparation phase includes the identification of the problems through inferencing processes and deep analysis. It is followed by the translation proper, aiming at reproducing local and global cohesiveness (Delabastita, 1994). The last phase, the revision one, can therefore be the locus of creative rewriting. Since translating conflicts might mean to manage linguistic and conceptual asymmetries (Massey and Ehrensberger-Dow, 2017), in this phase students could evaluate whether their translation reproduce or create new tensions in the target text.

As it lies both in the creations and in the creators, in the problem solving and in the solutions found, creativity has been proved to be related to longer revision (Rojo and Meseguer, 2018). Since reflective competence is a prerequisite for textual analysis skills (Massey and Ehrensberger-Dow, 2017), the preparation phase is the most crucial one and could develop inferencing mechanisms as follows (Gebbia, forthcoming):

1. Is the word/expression polysemous?

2. Is the literal meaning suppressed?

Yes → It is not a pun

No → It is a play with words

→ 2.2. Is the form relevant? Has the form been altered?

Yes → It is also a play on words (i.e. play on sounds).

If possible, reproduce or recreate a play on words in the TL

No → Try to preserve only the polysemy

Subsequently, a guided deep analysis of the linguistic choices of the source text could be initiated by these questions:

1. Is the pun based on a conventional metaphor? Can you find two meanings (one literal, one metaphorical) in the dictionary?

2. What are the two semantic domains creating a conflict in this context?

3. What are the associations foregrounded in the conflict?

Conversely, the revision phase could be prompted by these questions:

1. Can you preserve the two meanings by preserving at least one of the semantic domains used in the source metaphor?

2. Can you preserve the form too? If not, can you change the pun by substituting it with an altered or extended idiom?

3. Are metaphors reiterated, connected within the same text or in between texts? Which semantic domains are valuable to the overall function of the text?

In light of the explanations offered in the self-report and in line with Jin and Deifell (2013), students rely on the resources used to decipher contextual meanings, even novel ones, and tend to choose the first accessible option they encounter. As the facets of students' extralinguistic knowledge might not align with those of native speakers, instrumental competence, the ability to exploit the resources at hand (PACTE, 2011), should lie at the core of the revision (Hewson, 2016). Students should be sensitized on how to engage in longer negotiations with the source text and to find alternatives to the normative solutions in the extra linguistic knowledge documented in the resources used.

Going beyond the established discussion in grammatical and lexical terms, textual competence should in turn be addressed in the revision phase. In a cognitive vein, it should be treated as “an integrated competence in presenting the mental representations prompted by the ST in a coherent and justifiable manner in the TT” (Tian, 2020; p. 124). It should thus revolve around the notion of scenes/frames (Hewson, 2016) or text worlds (Tian, 2020), and the local metaphors should be investigated as world-building elements (Tian, 2020) in order to identify the elements to keep, sacrifice or reframe.

In sum, Hewson's three stages combined with a conflict-based approach that favors local and textual inferencing mechanisms can help students to move from a holistic approach to an analytical one, to finally shift to a synthesis phase where they can appreciate the communicative functions of local metaphors as fundamental means of textual cohesion.

5. Conclusions

Metaphors mostly originate from the need of expanding the boundaries of words to express “new semantic situations” (Ricoeur, 1973; p. 107). Under this view, not only is metaphor an established way of understanding and talking about a more abstract concept in terms of a more concrete one, but also artful creation which may eventually give rise to linguistic conventionalities. What is ultimately universal about metaphors, then, is the (pre)conceptual creativity that drives novel and conventional linguistic usage.

Conceivably, it is going beyond the systematicity of metaphors to delve into the dynamics of creativity that we can give account of metaphor as both linguistic and conceptual (Cameron and Deignan, 2006). If conventional metaphors are residual creativity stemming from the common behaviors of a linguistic/cultural community, novel ones represent a self-propelled mechanism of linguistic change (Maturana and Varela, 1991), rather than mere deviations from the norm.

Since translator students are challenged by conflictual metaphors, both locally and textually, well-established cognitive-oriented strategies should be combined with conceptual conflict models (Prandi, 2017; Rizzato, 2021) to raise awareness of the pragmatical interconnections of metaphors in discourse. As a starting point, metaphor translation competence could be put into the limelight of Translation Pedagogy by exploiting the metalinguistic power of puns. Ambiguity and conflictual meanings are not an essence of words, like polysemy, but a relation in discourse (Ricoeur, 1973). For their poetic and interpersonal function (Koller, 2003), puns can be a stimulating task that forces students to put themselves in the audience's place and to look at the interaction of meanings. Moreover, translator students should learn to feel comfortable at departing from the source text and leaving implicit meanings “between the lines.” To help them in such endeavor, guided inferencing mechanisms should corroborate the development of strategic competence as a prerequisite for the textual one.

Although future studies could probably operationalize conflict-based paradigms in the vein of the one here proposed and corroborate it with more in-depth online interviews, this study has yielded important findings on the relevance of explicit training for translation creativity. Puns, as linguistic games, are the epitome of the creativity underlying conceptual conflicts by means of preserving polysemy at the word level, and generating ambiguity, at the discourse one. They can thus function as a metalinguistic laboratory where students can explore the creative possibilities the source language exploits and the ones the target one has to offer.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to express her gratitude to Susan Nacey for her invaluable guidance on the methodological aspects of this study.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2023.1177658/full#supplementary-material

References

Aarons, D. (2017). “Puns and tacit linguistic knowledge”, in The Routledge Handbook of Language and Humor, ed. S. Attardo (New York, Abingdon: Routledge), 80–94. doi: 10.4324/9781315731162-7

Ageli, N. (2020). Creativity in the use of translation microstrategies by translation students at The University of Bahrain. Intern. J. Linguist. Lit. Tran. 3, 7–17. doi: 10.32996/ijllt.2020.3.10.2

Aljared, A. (2017). “The isotopy disjunction model,” in The Routledge Handbook of Language and Humor, ed. S. Attardo (New York, Abingdon: Routledge), 64–79. doi: 10.4324/9781315731162-6

Al-Zoubi, M. Q., Al-Ali, M. N., and Al-Hasnawi, A.R. (2006). Cogno-cultural issues in translating metaphors. Perspectives: St. Transl.14. 230–239. doi: 10.1080/09076760708669040

Atari, O. (2005). Saudi students' translation strategies in an undergraduate translator training program. Meta 50, 180–193. doi: 10.7202/010667ar

Bartezzaghi, S. (2017). “Dire quasi le stesse due cose,” in Giochi di Parole E Traduzione Nelle Lingue Europee, eds. F. Regattin and A. Pano Alamán (Bologna: Quaderni del Centro di Studi Linguistico-Culturali. Atti di Convegni 5), 1–6.

Cameron, L., and Deignan, A. (2006). The emergence of metaphor in discourse. Appl. Linguist. 27, 671–690. doi: 10.1093/applin/aml032

Cappelli, G. (2007). “The translation of tourism-related websites and localization: problems and perspectives,” in Voices on Translation, ed. A. Baicchi (RILA-Rassegna Italiana di Linguistica Applicata, Bulzoni Editore, Roma), 1–23.

Chesterman, A. (2020). “Translation, epistemology and cognition,” in The Routledge Handbook of Translation and Cognition, eds. F. Alves and A. L. Jakobsen (Abingdon/New York: Routledge), 25–36. doi: 10.4324/9781315178127-3

Chiaro, D. (2010). “Translation and humor, humour and translation,” in Translation, Humour and Literature, ed. D. Chiaro (London/New York: Continuum), 3–29. doi: 10.1093/applin/ams036

Chiaro, D. (2017). “Humor and translation,” in The Routledge Handbook of Language and Humor, ed. S. Attardo (New York, Abingdon: Routledge), 414–429. doi: 10.4324/9781315731162-29

Danesi, M. (1992). “Metaphorical competence in second language acquisition and second language teaching: the Neglected dimension,” in Georgetown University Round Table on Languages and Linguistics, eds J. E. Alatis, H. E. Hamilton, and A. H. Tan (Washington: Georgetown University Press), 489–500.

Delabastita, D. (1993). There's a Double Tongue: An Investigation into The Translation of Shakespeare's Wordplay with Special Reference to Hamlet. Amsterdam/Atlanta: Rodopi. doi: 10.1163/9789004490581

Delabastita, D. (1994). Focus on the pun: wordplay as a special problem in translation studies. Target. 6, 223–243. doi: 10.1075/target.6.2.07del

Delabastita, D. (1996). Introduction. The Translator. 2, 127–139. doi: 10.1080/13556509.1996.10798970

Djafarova, E. (2017). The role of figurative language use in the representation of tourism services. Athens J. Tour. 4, 1–15. doi: 10.30958/ajt.4.1.3

Dore, M. (2015). “Metaphor, humour and characterisation in the TV comedy programme Friends,” in Cognitive Linguistics and Humor Research, eds. G. Brône, K. Feyaerts and T. Veale (Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton), 191–214. doi: 10.1515/9783110346343-010

Dorst, A. G. (2016). “Textual patterning of metaphor,” in The Routledge Handbook of Metaphor and Language, eds. E. Semino and Z. Demjén, Z. (Abingdon/ New York: Routledge), 178–193.

Figar, V. (2019). Evaluating the “dynamics” of a metaphor cluster through the relevant dimensions of individual metaphorical expressions. Phil. Med. 11, 233–248. doi: 10.46630/phm.11.2019.15

Gan, X. (2015). A study of the humor aspect of English puns: views from the relevance theory. Theory Pract. in Lang. St. 5, 1215. doi: 10.17507/tpls.0506.13

Gebbia C. A. (forthcoming). “Creativity and metaphor translation competence: the case of metaphorical puns,” in Language in Educational and Cultural Perspectives, eds. B. Lewandowska-Tomaszczyk? and M. Trojszczak (Springer).

Gibbs, R. W. (1996). “What's cognitive about cognitive linguistics,” in Linguistics in the Redwoods: The Expansion of a New Paradigm in Linguistics, ed. E. Casad (Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter), 27–53. doi: 10.1515/9783110811421.27

Giora, R. (1991). On the cognitive aspects of the joke. J. Prag. 16, 465–485. doi: 10.1016/0378-2166(91)90137-M

Grice, H. P. (1975). “Logic and conversation”, in Syntax and Semantics: Speech Acts, eds. P. Cole and J. L. Morgan (New York: Academic Press), 41–58. doi: 10.1163/9789004368811_003

Hanić, J., Pavlović, T., and Jahić, A. (2016). Translating emotion-related metaphors: a cognitive approach. ExELL. 4, 87–101. doi: 10.1515/exell-2017-0008

Hempelmann, C. F. (2017). “Key terms in the field of humor,” in The Routledge Handbook of Language and Humor, ed. S. Attardo (New York, Abingdon: Routledge), 34–48. doi: 10.4324/9781315731162-4

Hempelmann, C. F., and Miller, T. (2017). “Puns: taxonomy and phonology,” in The Routledge Handbook of Language and Humor, ed. S. Attardo (New York, Abingdon: Routledge), 95–108. doi: 10.4324/9781315731162-8

Hewson, L. (2016). Creativity in translator training: between the possible, the improbable and the (apparently) impossible. Linguaculture. 7, 9–25. doi: 10.1515/lincu-2016-0010

Hoad, T. F. (Ed.). (1996). The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology. Oxford: Oxford University.

Holst, J. L. F. (2010). Creativity in Translation – A Study of Various Source and Target Texts. [dissertation/bachelor thesis]. [Aarhus]: Aarhus School of Business.

Hong, W., and Rossi, C. (2021). The Cognitive Turn in Metaphor Translation Studies: A Critical Overview. Jour of Trans Stu. 5, 83–115.

Housley, W., and Fitzgerald, R. (2002). The reconsidered model of membership categorization analysis. Qual. Res. 2, 59–83. doi: 10.1177/146879410200200104

Jabarouti, R. (2016). A semiotic framework for the translation of conceptual metaphors. Trad. Sig. Text. Prat. 7, 85–106. doi: 10.4000/signata.1185

Jared, D., and Bainbridge, S. (2017). Reading homophone puns: evidence from eye tracking. Can. J. Exp. Psy. 71, 2–13. doi: 10.1037/cep0000109

Jensen, A. (2005). Coping with metaphor. A cognitive approach to translating metaphor. HERMES 18, 183–209. doi: 10.7146/hjlcb.v18i35.25823

Jin, L., and Deifell, E. (2013). Foreign language learners' use and perception of online dictionaries: a survey study. J. On. Learn. Teach. 9, 4.

Joshi, A., Sharma, V., and Bhattacharyya, P. (2015). “Harnessing context incongruity for sarcasm detection,” in Proceedings of the 53rd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 7th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 2: Short Papers), eds. C. Zong and M. Strube (Bejing: Association for Computational Linguistics) 757–762. doi: 10.3115/v1/P15-2124

Kalda, A., and Uusküla, M. (2019). The role of context in translating colour metaphors: an experiment on English into Estonian translation. Op. Linguist. 5, 690–705. doi: 10.1515/opli-2019-0038

Khan, S. (2014). Word play in destination marketing: an analysis of country tourism slogans. TEAM. 11, 27–39.

Kimmel, M. (2010). Why we mix metaphors (and mix them well): discourse coherence, conceptual metaphor, and beyond. J. Prag. 42, 97–115. doi: 10.1016/j.pragma.2009.05.017

Koller, V. (2003). Metaphor clusters, metaphor chains: analyzing the multifunctionality of metaphor in text. Metaphorik.de 5, 115–134.

Krikmann, A. (2009). On the similarity and distinguishability of humour and figurative speech. Trames.13, 14–40. doi: 10.3176/tr.2009.1.02

Kyratzis, S. (2003). Laughing metaphorically. Metaphor and humour in discourse. Paper presented at the 8th International Cognitive Linguistics Conference (Theme Session: Cognitive Linguistic Approaches to Humour). University of La Rioja.

Lakoff, G. (1990). Cognitive versus generative linguistics: How commitments influence results. Lang. Comm. 11, 53–62. doi: 10.1016/0271-5309(91)90018-Q

Lakoff, G., and Johnson, M. (1980). Metaphors We Live By (1st ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Langlotz, A. (2016). “Language, creativity, and cognition,” in The Routledge Handbook of Language and Creativity, ed. R. H. Jones (New York, Abingdon: Routledge), 40–60.

Littlemore, J., Krennmayr, T., Turner, J., and Turner, S. (2014). An investigation in metaphor use at different levels of second language writing. Appl. Linguist. 35, 117–144. doi: 10.1093/applin/amt004

Littlemore, J., and Low, G. (2006). Metaphoric competence, second language learning, and communicative language ability. Appl. Linguist. 27, 268–294. doi: 10.1093/applin/aml004

Lörscher, W. (2005). The translation process: methods and problems of its investigation. Meta. 50, 597–608. doi: 10.7202/011003ar

Lundmark, C. (2005). Metaphor and creativity in British magazine advertising, [dissertation/PhD thesis]. [Luleå]: Luleå tekniska universitet.

Maalej, Z. (2008). Translating metaphor between unrelated cultures: a cognitive-pragmatic perspective. Sayyab Tran. J. 1, 60–82.

Maci, S. M. (2012). “Glocal features of in-flight magazines: when local becomes global. An explorative study,” Altre Modernità, (Confini mobili: lingua e cultura nel discorso del turismo), 196–218.

MacMillan Dictionary (2023). Free English Dictionary and Thesaurus. Available online at: https://www.macmillandictionary.com/

Mandelblit, N. (1995). The cognitive view of metaphor and its implications of translation theory. Tran. Mea. Part 3, 482–495.

Massey, G., and Ehrensberger-Dow, M. (2017). Translating conceptual metaphor: the process of managing interlingual asymmetry. Res. Lang. 15, 173–189. doi: 10.1515/rela-2017-0011

Maturana, H. R., and Varela, F. J. (1991). Autopoiesis and Cognition: The Realization of the Living (Vol. 42). London: Springer Science and Business Media.

Meneghini, N. (2018). “Metaphors and translation. Some notes on the description of pain,” in A Twelfth Century Persian Poem. In Between Texts, Beyond Words: Intertextuality and Translation, ed. N. Pesaro (Venezia: Edizioni Ca' Foscari), 65-86. doi: 10.30687/978-88-6969-311-3/004

Nacey, S. (2013). Metaphors in Learner English. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing. doi: 10.1075/milcc.2

Nacey, S. (2019). “Development of L2 metaphorical production,” in Metaphor in Foreign Language Instruction 42, eds. A. M. Piquer-Píriz and R. Alejo-González (Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter), 171–196. doi: 10.1515/9783110630367-009

Nacey, S., and Skogmo, S. F. (2021). Learner translation of metaphor: Smooth sailing? Metaphor Soc. World. 11, 212–234. doi: 10.1075/msw.00016.nac

Navarro, B. M. (2019). ‘Humour in interaction and cognitive linguistics: critical review and convergence of approaches. Compl. J.Eng. St. 27, 139–58. doi: 10.5209/cjes.63314

Nugroho, R. A. (2003). The use of microstrategies in students' translation: a study on classroom translation process and product. UNS J. of Lang. St. 2, 1-21. doi: 10.20961/prasasti.v2i1.316

Oller, J. W. (1976). Evidence for a general language proficiency factor: An expectancy grammar. Die neueren sprachen. 75, 165–174.

Ozga, K. (2011). On Isomorphism and Non-Isomorphism in Language: An Analysis of Selected Classes of Russian, Polish and English Adverbs within the Communicative Grammar Framework. Łódz: Primum Verbum.

PACTE (2011). Results of the validation of the PACTE translation competence model. Translation problems and translation competence. Methods and Strategies of Process Research, eds. C. Alvstad, A. Hild and E. Tiselius (Amsterdam: Benjamins), 317–343. doi: 10.1075/btl.94.22pac

Partington, A. (2009). A linguistic account of wordplay: the lexical grammar of punning. J. Pragmatics – J. Prag. 41, 1794–1809. doi: 10.1016/j.pragma.2008.09.025

Philip, G. S. (2019). “Metaphorical reasoning in comprehension and translation: An analysis of metaphor in multiple translations,” in Metaphor in Foreign Language Instruction 42, eds. A. M., Piquer-Píriz and R. Alejo-González (Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter), 129–146. doi: 10.1515/9783110630367-007

Pollio, H. R., and Barlow, J. M. (1975). A behavioural analysis of figurative language in psychotherapy: One session in a single case study. Lang. Sp. 18, 236–54. doi: 10.1177/002383097501800306

Prandi, M. (2012). A plea for living metaphors: conflictual metaphors and metaphorical swarms. Met. Symbol. 27, 148–170. doi: 10.1080/10926488.2012.667690

Prandi, M. (2017). Conceptual Conflicts in Metaphors and Figurative Language. New York: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315208763

Ricoeur, P. (1973). Creativity in language. Phil. Today. 17, 97–111. doi: 10.5840/philtoday197317231

Rizzato, I. (2021). Conceptual conflicts in metaphors and pragmatic strategies for their translation. Front. in Psy. 12, 662276. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.662276

Rojo, A., and Meseguer, P. (2018). Creativity and translation quality: opposing enemies or friendly allies? HERMES – J. Lang. Comm. Business 57, 79–96. doi: 10.7146/hjlcb.v0i57.106202

Rosa, A. A. (2010). “Descriptive Translation Studies (DTS),” in Handbook of Translation Studies eds. L. van Doorslaer and Y. Gambier (Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company), 94–105. doi: 10.1075/hts.1.des1

Royer, J. M., and Cunningham, D. J. (1981). On the theory and measurement of reading comprehension. Cont. Edu. Psyc. 6, 187–216. doi: 10.1016/0361-476X(81)90001-1

Sabatini, F., and Colletti, V. (2004). Il Sabatini Coletti. Dizionario della Lingua Italiana. Rizzoli Larousse.

Samaniego Fernández, E. (2002). Translators' English-Spanish metaphorical competence: impact on the target system. Elia 3, 203–218.

Saygin, A. P. (2001). Processing Figurative Language in a Multi-Lingual Task: Translation, Transfer and Metaphor. Proceedings of corpus-based and processing approaches to figurative language workshop. Corp. Linguist, Lancaster: Lancaster University.

Schäffner, C. (2004). Metaphor and translation: some implications of a cognitive approach. J. Prag. 36, 1253–1269. doi: 10.1016/j.pragma.2003.10.012

Schoos, M., and Suñer, F. (2020). Understanding humorous metaphors in the foreign language: a state-of-the-art review. Zeitschrift für Interkulturellen Fremdsprachenunterricht. 25, 1446.

Semino, E. (2008). Metaphor in Discourse. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511816802.015

Sjørup, A. C. (2013). Cognitive Effort in Metaphor Translation: An Eye-tracking and Key-logging Study. [dissertation/PhD thesis]. [Copenhagen]: Copenhagen Business School.

St. André, J. (2017). Metaphors of translation and representations of the translational act as solitary versus collaborative. Tran. Studies. 10: 3, 282–295. doi: 10.1080/14781700.2017.1334580

Steen, G., Dorst, A. G., Herrmann, J. B., Kaal, A., Krennmayr, T., Pasma, T., et al. (2010). A Mtehod for Linguistic Metaphor Identification. Amsterdam: Benjamins. doi: 10.1075/celcr.14

Steiner, E. (2021). “Translation, equivalence, and cognition,” in The Routledge Handbook of Tran. Cognition, eds. F. Alves and A.L. Jakobsen (New York: Routledge), 344–359. doi: 10.4324/9781315178127-23

Tian, L. (2020). “Revisiting textual competence in translation from a text-world perspective,” in Translation Education. A Tribute to the Establishment of World Interpreter and Translator Training, eds. J. Zhao, D. Li and L. Tian (Singapore: Springer) 121–134. doi: 10.1007/978-981-15-7390-3_8

Toury, G. (2012). Descriptive Translation Studies: And Beyond. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing. doi: 10.1075/btl.100

Treccani (1929). Vocabolario Italiano. Available online at: https://www.treccani.it/vocabolario/

van den Broeck, R. (1981). The limits of translatability exemplified by metaphor translation. Poetics Today. 2, 4. 73–87. doi: 10.2307/1772487

Vandaele, J. (2011). “Wordplay in translation,” in Handbook of Translation Studies (Vol. 2), eds. Y. Gambier and L. van Doorslaer (Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company), 180–183. doi: 10.1075/hts.2.wor1

Veale, T. (2004). Incongruity in humor: root cause or epiphenomenon? Humor: International J. Hum. R. 17, 419–428. doi: 10.1515/humr.2004.17.4.419

Keywords: novel metaphors, conflictual metaphors, conceptual metaphor theory, metaphor clusters, humor, metaphor translation competence

Citation: Gebbia CA (2023) Translator learners' strategies in local and textual metaphors. Front. Commun. 8:1177658. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2023.1177658

Received: 01 March 2023; Accepted: 14 April 2023;

Published: 03 May 2023.

Edited by:

Ilaria Rizzato, University of Genoa, ItalyReviewed by:

Stefania Gandin, University of Sassari, ItalyMirko Casagranda, University of Calabria, Italy

Copyright © 2023 Gebbia. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Chiara Astrid Gebbia, chiara.a.gebbia@uia.no

Chiara Astrid Gebbia

Chiara Astrid Gebbia