- Department of Humanities, University of Turin, Turin, Italy

The article focuses on Renaissance emblematics and its privileged relationship with metaphor, considered in the light of contemporary theories as an inherently tensional form, steeped in interchange and transition and heavily relying on a basically conflictual dynamic. Though often dismissed as an academic, antiquarian form of figurality or as a pleasing symbolical form steeped in monologic stability, emblematics was in fact conceived as a brand-new hybrid textual mode whose complex interplay of signs favored multiplied discursive models and the constant relay between visual and textual elements, between abstract conceptualization and thoughts-made-visible. The paper, in other words, will try to reassess and re-evaluate emblematics as a profoundly plural form of communication whose connections with metaphor were much deeper and qualitatively different than it is usually thought. This slant approach to what is conventionally considered a tame example of early modern textuality highlights, on the contrary, its idiosyncratic meaning procedures: the metaphorical conceptualizations of emblematic compositions were not necessarily based on similarity and testify to their cognitive potential which ushered in an idea of communication as projective and dislocating, as a dialogic space allowing for the paradoxical copresence of ideological consistency and its deconstruction.

1. Introduction

This article focuses on Renaissance emblematics1 and its privileged relationship with metaphor, considered in the light of contemporary theories as an inherently tensional form, steeped in interchange and transition and heavily relying on basically conflictual dynamics. After a general discussion of emblematics and its features, the paper will try to reassess and re-evaluate it as a profoundly plural form of communication whose connections with metaphor were much deeper and qualitatively different than it is usually thought. This slant approach to what is conventionally considered a tame example of early modern textuality highlights, on the contrary, its idiosyncratic meaning procedures: the metaphorical conceptualizations of emblematic compositions were not always based on similarity but often conflictual and testify to their cognitive potential which ushered in an idea of communication as a dialogic space allowing for the paradoxical copresence of ideological consistency and its deconstruction.

After an introductory presentation of some fundamental aspects of emblematics and metaphor, the article will discuss some theoretical issues and concrete examples in which the relationship between metaphor and emblematics features prominently and opens stimulating hermeneutic paths.

2. Theoretical background

2.1. Emblematics

Though often dismissed as an antiquarian form of figurality, or as a pleasing symbolical expression steeped in monologic stability and surreptitiously employed to manipulate its audience, Renaissance emblematics was in fact conceived as a brand-new textual form2 whose hybrid nature and interplay of signs seemed to open up ground-breaking epistemological perspectives. In particular, it seemed to satisfy the need for a kind of knowledge which could express material concepts in an intuitive way: through its union of figurative and poetic language, two completely diverse forms were forcibly joined in a syntagmatic unity which was transformed and fulfilled at a higher level in the form of a paradigmatic course of action or an exemplary anecdote with sweeping effects. Emblematic writers were enthused over the revolutionary possibilities opened up by this new construct: the “what”—the meaning—could be shaped by the “how”—the mode of its comprehension and vice versa; the interaction between visual and verbal elements favored multiplied discursive models and the constant relay between abstract conceptualization and thoughts-made-visible; Neoplatonic and Neoaristotelian paradigms could be (though not always deliberately or consciously) mixed; symbols and analogies could be used in a rhetorical as well as metaphorical way.3 The “invention” of emblematics, in other words, was the proof that mankind had found an advanced form with a wide cognitive scope which could expand human faculties and make communication basically akin to divine knowledge.4

These features had a profound impact on the reader response that authors anticipated: on the one hand, the union of two different modes of perception provided writers with a new language, reliable and adaptable, and qualified to “redistribue la fragmentation de tous les aspects de l'univers à l'intérieur d'une recréation poétique et du monde et des lettres” (Spica, 1996, p. 230). On the other, the importance of the interpretative moment and the repeated appeal on the reader's ability to infer the message implied a parallel proliferation of meanings: the necessity of deriving interpretations from the interaction of the visual and textual elements meant that any emblematic composition was able to produce cognitive effects not only by conveying clear, universal moral messages (for example, strengthening traditional assumptions), but also by inducing the active participation of a hermeneutically committed reader in the negotiation of meanings. After all, emblematics did not aim at duplicating already known information and theorists stressed that texts should never repeat or simply describe what was already evident in the picture or vice versa.

In short, emblematics was seen as a pioneering and incredibly effective intellectual instrument, which sat at the very heart of foundational epistemological debates in the early modern period concerning which signs were expressive and how they meant. Despite its quaint and apparently frivolous nature, it can be considered as a wide cultural index, as a space serving as both meeting ground and battle ground for encoded but heterogeneous sign systems, as a conflictual cognitive field, as a form able to appropriate and reactivate collective memories and unspoken attitudes and to provide “partisan representations of discursive and pictorial traditions and mentalités” (Wagner, 1996, p. 37).

Unsurprisingly, these innovative features of emblematics were contained and progressively distorted by an anchorage practice5 which prevented its multiplicity from thriving, ultimately transforming this form into a homogeneous, static site of ideological as well as semiotic coherence. Readers, who were trusted to imagine a whole range of premises or draw conclusions for themselves, were progressively limited in their freedom and encouraged to pursue an effortless hermeneutic approach and accept the one, predetermined meaning. The latter model was obviously functional to a more pervasive ideological practice, particularly evident in religious emblematics, where texts featured a monologic consistency and a prevalence of what Foucault (1983) would call resemblance over similitude, functional to interpellating readers and “re-creating” their souls and bodies. This, however, was not a uniform and successful practice, with some borderline cases whose idiosyncratic meaning procedures ushered in an idea of communication as projective and dislocating.

2.2. Emblematics and metaphor

From a certain point of view, the relationship between emblematics and metaphor is so obvious that it could be taken for granted as a matter of fact. The reliance on symbolical conventions and on metaphorical procedures of signification was so strong that imprese were often identified with metaphors and, well into the seventeenth century, Tesauro summarized and perfected a century of theories “subsuming visual and verbal manifestations of ingegno under an ‘interdisciplinary' notion of metaphor” (Gilman, 1978, p. 14). In his Idea delle perfette imprese, a short unpublished treatise probably composed before 1629, Tesauro (1975, p. 38) had already stressed that imprese featured “una perfetta somiglianza di proporzione” (a perfect similarity of proportion) emphasized by an “arguto motto” (witty motto) and that their invention was a splendid gift from the poets “essendo quelle sopra qualche metafora fabricate” (they being constructed on some metaphor; 1975: 45). Then, in his later and most famous treatise, Tesauro (1670, pp. 635–636) explicitly associated impresa and metaphors, defining it “metafora in fatti” or “metafora dipinta” (actual metaphor and painted metaphor) and concluding that “la Perfetta Impresa è una metafora” (the most perfect impresa is a metaphor).

These ideas stressed that emblematic artifacts were far from being the static, idiosyncratic creations of pedantic antiquarians and that their metaphorical affiliation was deeper than a superficial connection with a rhetorical figure. Emblematics was deemed superior to other existing forms of communication because its metaphorical features allowed for new possibilities to analyze and “tell” the world. The cognitive bearings and the peculiar capacity of teaching in an entertaining way thanks to its bimedial nature meant that an emblematic artifact, while customarily aiming at conveying messages in a pleasant but unambiguous way, was in fact a very complex artifact and featured syncretical elements, combined and valorised in their diversity in order to make the message richer and more fulfilling. The co-presence of verbal and visual elements, joined together though keeping their prerogatives, also implied a marked revision of the traditional roles and claims of communication in early modern discussions on the ways meaning was produced and figures signified: emblematic compositions utopistically tried to produce granted and reliable signs in a new form, “writable” texts whose non-artistic status underscored a typically unstable referential quality and stimulated the reader's hermeneutic cooperation.

These peculiar features demonstrate that emblematics can be fruitfully read in the light of some contemporary critical approaches, such as Conceptual Metaphor Theory, which stressed the inherently metaphorical nature of human communication.6 However, when authors discussed the quality of their works and customarily defined metaphors from a comparative perspective,7 they always had in mind a trope in which the function of designation had lost its centrality in favor of more conflictual aspects. Taegio (1571, p. 15v) for example, recommended that from both the figure and the motto “ne deriui non certezza, ma dubbio … Tal che di due cose incerte & imperfette ne riesca una certa, & perfetta” (derive not certainty but doubt … so that out of two uncertain and imperfect things a certain and perfect one may come out). Twenty years later, Capaccio (1592, p. 48v) explicitly praised emblematic compositions featuring “due Figure contrarie per antipatia, come il Fuogo col Leone, e con l'Elefante il Porco” (two figures contrasting each other due to antipathy, such as the fire and the lion, or an elephant and a hog) because an impresa which “haurà questa contraria maniera di Comparatione, sarà bella, e giudiciosa, più che quando gli ogetti saranno di Comparatione vniforme” (will have this contrary way of comparison will be more beautiful, and sensible, than when objects will feature a uniform comparison).

Emblematists would have undoubtedly subscribed to Ricœur's idea that the “tendency toward further development distinguishes metaphor from the other tropes, which are exhausted in their immediate expression” (2003, p. 224), because their emblematic constructs did not pursue a mere resemblance doubling what was clearly visible, but rather a similitude capable of revealing what known, recognizable objects hid behind the film of familiarity. Metaphors, in other words, were not only linguistic tools deployed to confirm shared concepts and ultimately overcome differences between apparently distant realities; the metaphorical quality which was extolled in an emblematic text was its capacity of generating new, creative conceptualizations.

This proves that emblematics shared with metaphors the same epistemological potential as described by recent scholars such as Black (1962), Ricœur (2003), or Prandi (2017), who variously highlighted their projective nature, their inherently dynamic and even conflictual essence. The open-endedness of metaphoric interpretation and the resulting wide range of implications that may be recovered are exactly what authors of imprese or emblems were after. Indeed, it was exactly the tendency of metaphors to transfer a concept into an alien domain which was prized for its cognitive bearings and as a pleasant instrument of interaction and creation.

Prandi (2017, p. 114) convincingly stressed that any metaphor “stems from the transfer of a concept into a strange domain” and that conflict is an inherent characteristic of metaphors and figurative language. In his view, conflictual metaphors are the consequence of a contingent interpretation of expressions that do not match with a consistent conceptual model, even if they follow a customary scaffolding at a syntactical level8: this means that “a conflict is not a structural property of the expression, but the outcome of a choice made by the interpreter” (2017, p. 42). Conflictual metaphors do not originate from the polysemy inherent in language, but from the perception of a set of inconsistent relations and a contingent interpretation of complex meanings. In other words, a “normal” linguistic form is used to convey new meanings and modify the consistent conceptual structures belonging to a shared heritage of everyday notions and expressions.

These ideas are particularly pertinent to emblematics: emblematists drew abundantly on metaphor because it was the most powerful and productive conceptual tool they could use to reassess the whole traditional lore of proverbs, commonplaces, and popular wisdom on which their compositions were built. The positive modification of an established vision of the world produced by the interaction between words and images meant that these artifacts refused to be merely perfunctory, claiming, on the contrary, the right to negotiate the world and create new meanings. By avoiding direct, referential descriptions in favor of more heuristic and creative conceptualizations, emblematic constructs fostered a tensional approach aiming at the same extension of knowledge as Carston (2010, p. 298) carved out for metaphor: “what a metaphor does is bring to our attention aspects of the topic that we might not otherwise notice, by provoking us or nudging us to ‘see' the topic in a new or unusual way”.

Similarly, the co-presence of incompatible elements (the verbal and the visual text, real objects and abstract categories, impossible chronologies and topographies and so on) in an otherwise well-arranged and disciplined formal text (an impresa or an emblem) implied a conflict between literal and metaphorical interpretation, a reinterpretation of the concepts and realities inherent in the tenor, a valorization of metaphor not in its substitutive but in its predicative aspect: in metaphors, Ricœur (2003, p. 292) suggested, “The copula is not only relational. It implies besides, by means of the predicative relationship, that what is redescribed; it says that things really are this way.”

3. Discussion

3.1. Body and soul

The ideological and critical background outlined above provides a useful framework to recontextualize and discuss a few issues involving the relationship between metaphor and emblematics. Early modern treatises on emblematics, particularly the Italian ones on imprese,9 made subtle distinctions and precise qualifications to define the various features of emblematic compositions, but all of them devote extensive treatment to the relationship between the verbal and visual parts, customarily describing them as the soul and the body.10 This metaphorical conceptualization is particularly significant for a “new” form that allowed authors to use visual and verbal elements together, though their union was far from being innocuous. After all, in most Medieval thinkers, the source of truth was placed within the soul, while knowledge based on the senses was deemed as basically unreliable, necessary only to get along in the world, a doubtful mirror of a transient world if not a vehicle of temptation, which could not lead to happiness and produced a dangerous involvement of the soul with bodily sensations.

The distinction between body and soul acquired a new dimension after Giovio, in his seminal treatise, resorted to the same metaphor to describe the structural basis of imprese, although it was detached from moral issues to be specifically applied to an epistemological dimension. The correct balance between words (the soul) and images (the body) implied exhilarating but also dramatic epistemological negotiations between the verbal and the visual: since emblematic constructs were composite, hybrid signs, they also abolished the conventional separation between visual representation and linguistic reference and could thus overcome the Platonic stigmas against writing as a place of non-presence (denounced in Phaedrus) and images as false simulacra (condemned in the Republic). Emblematics was thus repeatedly stretched between the attempt to reconcile the visual-verbal dualism to extract knowledge from it, and the stimulating possibility of producing new constructs in which meaning potentials were left to proliferate in a sort of chain reaction; between an attenuating, didactic use in which images increasingly became mere illustrations of verbal texts, and an intensifying, productive use stressing the “mutual” reading of text and image.

The creation of this visuo-verbal experience inevitably entailed a model of communication in which the idea of a fixed, hierarchical relationship between authors and readers was repeatedly questioned: a dynamic, multi-layered textual form, theoretically prone to manifold interpretation, inevitably triggered a more unstable and performative form of viewership, activated by and dependent on a participatory reader, which in turn triggered fundamental questions involving the agency of texts.11

The resort to the body/soul metaphor quintessentially summarized this opposition: the theoretical discussions and definitions of early modern theorists extended the inherent tension of the human source domain into a conflictual conceptualization correspondent to the conflict between the two forms. When Giovio's terminology was partially superseded by Ruscelli's, the agonic relationship between words and images became even more central and, though it often resulted in the victory of the verbal over the figural12 the necessary coexistence of visual and verbal elements meant that emblems and imprese were inherently paragonal meaning structures in which two opposing and apparently mutually exclusive forms were artificially made to coexist within the same representational space. This, in turn, means that emblematic constructs should be addressed as tensional forms in which the presence of heterogenous forms artificially bound together bore special cognitive relevance, and in which the decorative and moral functions could never erase the dynamic and conflictual nature of these artifacts. This may appear surprising if seen in the light of the huge corpus of comparative studies on emblematics which tend to privilege its cultural associations or intertextual allusions; however, an emblematic composition must not necessarily be treated as a “homogeneous site of ideological and semiological coherence” and can be more fruitfully approached as a “space of dispersion and sedimentation in which conflicting possibilities work in parallel with—or, in certain cases, against—authorial cl/aims and objectives” (Mermoz, 1989, p. 502).

Emblematics can then be considered as a privileged cultural moment in which some recent critical issues concerning the agonic relationship between the verbal and the visual found an initial, embryonical instance: the possibility of a semiotic regime where the world of things was inherently penetrated by discourse, together with the disruptive potential of a tensional, bimedial form, will acquire paramount importance in post-structuralist studies such as Foucault's or Barthes'. When Mitchell (1986, p. 49) discussed the conflictual relationship between poetry and painting, he again resorted to the body/soul metaphor, claiming that there are

powerful distinctions that effect the way the arts are practiced and understood. […] there are always a number of differences in effect in a culture which allow it to sort out the distinctive qualities of its ensemble of signs and symbols. These differences, as I have suggested, are riddled with all the antithetical values the culture wants to embrace or repudiate: the paragone or debate of poetry and painting is never just a contest between two kinds of signs, but a struggle between body and soul, world and mind, nature and culture.

Also Wagner's of discussion iconotexts13 is particularly interesting form the perspective of emblematics, since he defines iconotexts as artifacts “in which the verbal and the visual signs mingle to produce rhetoric that depends on the co-presence of words and images” and, more specifically, “integrate the semantic (denotative and connotative) meaning of the written texts that are iconically depicted, urging the ‘reader' to make sense with both verbal and iconic signs in one artifact” (Wagner, 1996, p. 16). This definition, which underscores how “the visual is as rhetorical as the verbal” (p. 33), could be easily applied to emblematics, although Wagner himself (p. 16) too hastily dismisses this possibility asserting that emblems were “a classical example of iconotexts which are, however, pre-determined in that the reader was expected to recognize and accept commonplace assumptions”. On the contrary, as was repeatedly stressed above, in emblematics words and images were mutually interpenetrating (what Wagner terms intermediality: p. 17) and there was mobile intertextuality between texts and images when it came to semantic and rhetorical relations, so the reader was invited not to forget that this “mutual illumination” must not erase the difference and différance in each medium and between them.

3.2. Hermeneutic practices

Although the preceding section testifies to the conflictual nature inherent in emblematic artifacts, mirrored by a parallel conflictual metaphorical juxtaposition, it must be stressed that their primary function was never to create ambivalent compositions or foster ambiguity. The possible indeterminacy derived from lexical and meaning aspects, not from the structural construction of an emblem, even though the co-presence of visual and verbal elements, as argued above, made them a dialectical field of forces which were inevitably to be recognized and negotiated. As Pinkus (1996, p. 8) rightly stresses, “a hybrid, or combinatory, form like the emblem might effectively temper writing with images to mediate fears of misreading or dissimulation”, but at the same time “the copresence of both word and image only increases the silence emitted, so the form could potentially be replenished with meaning by readers who are ill prepared to extract the one, true significance”.

In a way, the metonymic evolution of emblematics was an inevitable consequence of the attempt to contain the conflictual metaphorization triggered by this tension between visual and verbal. After all, emblems themselves were born as a “bourgeois” form, a repository of moralistic ornaments in the form of Latin epigrams composed over several years by a learned Milanese jurist with an eminently practical function (see Alciato, 1531). However, even if they were less “noble” than imprese, emblems were structurally and semiotically more complex, with longer and more particularized texts accompanying more assorted and elaborated images, thus requiring a prolonged reading process.14 The general idea of creating a text to convince and persuade in an entertaining way progressively yielded to a parallel necessity of limiting the multiplicity of meanings and painstakingly guiding their interpretation by making them as univocal as possible: the reciprocal mirroring of figures and words, which should induce an active appreciation from the reader in a sort of intellectual short circuit, was increasingly transformed into a sort of duplication, two media put together with illustrative and descriptive aims so as to circumscribe, contain and direct interpretation.

The tensional features of emblematic constructs, in other words, were not erased but redirected in order to exploit them for moral edification, even though this ideological practice was typically hidden behind the veil of merely witty, delightful entertainment.15 The images, accompanied and interpreted by the verbal part, were fundamental to spark off the process of personal meditation, striking the reader's imagination and triggering emotions, but this was not the end of meditation because sensible forms must be abandoned at some point in a process of gradual abstraction leading to spiritual realities. From this point of view, images and figurative language were no more vehicles of truth but disposable imaginative aids for the anagogical advancement of the reader.16 Quarles (1635, sig. A3r) made this explicit from the outset of his book by reminding the reader that an emblem was a “silent Parable” which must be “presented so as well to the eye as to the ear”. It was basically a return to some well-established rhetorical strategies, such as the resort to enargeia through eye-catching images: Wilson's Arte of Rhetorique, the most popular Elizabethan treatise on rhetoric, recommended that “Images must bee set foorth, as though they were stirring, yea, they must be sometimes made ramping, & last of al, they must be made of things notable, such as may cause earnest impression of things in our minde” (Wilson, 1909, pp. 213-14).

Yet, the cognitive potential of the union of words and images was too powerful to be perfectly contained. Alternative interpretations and implications were always possible especially in those cases where long comments interacted with plurisemiotic images. The resort to longer texts, in other words, seemed to guarantee a canonical, orthodox interpretation but, at the same time, exposed the emblematic composition to the dangers of hermeneutic plurality.

An interesting example is provided by Rollenhagen's emblem 20 of his Nucleus Emblematum Selectissimorum (Rollenhagen, 1611), reused and radically transformed by Wither in his Collection of Emblemes (Wither, 1635). As is well known, the images in both books are the same (in his warning “To the Reader” Wither made no bones about declaring the excellence of Crispijn van de Passe's engravings): in the case of emblem 20, the figure shows a young, bare-chested man in the foreground holding a sieve over his head during a storm (the intensity of the rain is clearly expressed by the thick series of lines radiating from the cloud above); at his back, four hens (one spreading her wings, another one pecking something from the ground) are gathered near an empty farm cart, while in the background two people and a dog rush across an open space bounded by a village to find a shelter from the pouring rain. The image (Figure 1) is surrounded by a puzzling Latin motto, (TRANSEAT) which finds a similarly surprising explanation in the short text below it: “Perfer et obdura: Tempestas transeat olim,/Fulgebit puro laetior axe dies.” In short, the emblem is a positive, optimistic invitation to endure and hang on, because the storm will end soon and the sun will shine brighter.

Figure 1. From Rollenhagen (1613, p. 20).

However, the whole composition features a series of elements which are clearly at odds with this interpretation. The idea of transience is clearly evoked through the sieve the young man holds above his head, but, as it turns out, it is meant in a more far-fetched way, not to describe the water literally sifting through its holes but to remind that the rain will stop and the sun will shine back soon. The contrast between the foreground and the background scene can also be interpreted as a confirmation of this: while gloomy clouds overhang the village in the far background and the people in the open space rush desperately to find shelter, the characters in the foreground give a radical different impression, the man in full light walking leisurely with the sieve above his head and the hens at his back calmly bearing the rain, perhaps already sensing the imminent return of the sun (from this point of view the radiating lines coming from the cloud seem to anticipate the radiating rays of the sun).

All this amounts to an inconsistent conceptualization of impermanence, in which the starting point is a concrete object metonymically connected to the idea of passing but here valorised as a conflictual metaphor to invite the reader to resort to his/her hermeneutic abilities, actively interpret the composition and eventually modify his/her perception of reality. Apparently, the emblem proposes a static example which progressively unfolds all its multiple configurations of ideas, ultimately amounting to a conflictual conceptual representation of Heraclitus' most famous idea that “everything flows” astoundingly evoked by the projection from the concrete domain of the sieve. In other words, impermanence is not the end of the story, it is used as an invitation to hang on in the rain but also in the act of interpretation: even more symbolically, it induces to look at the silver linings in life, because even the worst situations do not last forever and a positive outcome will emerge.17

The proliferation of meanings, however, does not stop here. The invitation “Perfer et obdura” irresistibly recalls Catullus' self-addressed invitation in carmen VIII to be strong and firm after the final break-up of his relationship with Lesbia. This potential amorous allusion further augments the emblem's resonance: are we reading a transposition of Catullus' poem, in which the end of a turbulent love relationship is conceptualized as pouring rain? Is the young man's ridiculous attempt to shelter his head with a sieve a metaphorical conceptualization to signify the inanity of sheltering from a loving passion, even if it has just ended sadly? Is the young man ironically “quoting” the poem, presenting his case as different from Catullus' (he must hold out because in the end things will get better, whereas the lovesick fool Latin poet tries to cheer himself up even though there will not be a positive outcome)? Is the emblem an invitation for readers to stop deluding themselves and be strong like Catullus, facing optimistically every day's difficulties instead of complaining? Are readers invited to consider the beauty of the young man's half naked body, stop being fools who worry and work hard instead of enjoying their lives and its pleasures? Or is the allusion to Catullus' poem simply meant to stress the illusory, transient nature of desire which will fade away like rain through a sieve?

In any case, the interaction of the visual elements and the verbal allusions reinforce the impression of a centrifugal emblematic composition in which the words of the accompanying text do not tie themselves coherently to the image. The emblem amounts to a concrete, agonic ground where the verbal and the visual define two mutually distinct discursive regimes which coexist in a deconstructive activity investing both expression and signification. More importantly, it demonstrates that the teeming relationship between the visible and the expressible opens up a collateral meaning space on whose core lies a discourse imbricated in the unconscious energy of desire. In this emblem, designation has lost its centrality, it has been made permeable to libidinal forces, it has turned into the “figural” theorized by Lyotard (2001) as “more than a chiasmus between text and figure–it is a force that transgresses the intervals that constitute discourse and the perspectives that frame and position the image” (Rodowick, 2001, p. 2).

Whatever our interpretation of Rollenhagen's emblem, the allusion to Catullus' poem imposes a powerful input on the composition, reminding readers that the practice of vision imposed by emblematics was always a staggering world rife with desire. Having no pretensions to univocity, and relying more on conflictual conceptualizations than on moralistic truths, the emblem annihilates any tendency to monolithic textualism and valorises the emblematic montage as a paragonal blend where intellectual and intuitive cognition negotiates with desire and affects. The composite nature of the emblem makes the experience of reading not merely visual or intellectual, but fully embodied and affected by the material properties of the object, thereby producing outstanding cognitive effects.

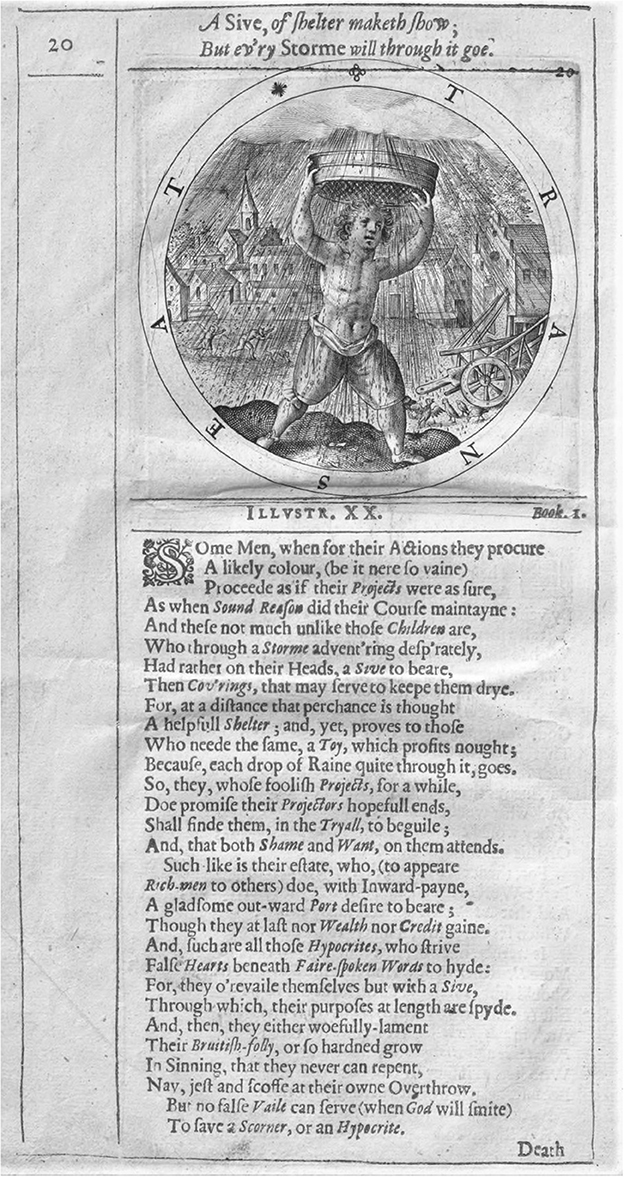

Wither's version of the emblem is radically different (Figure 2). The short introductory couplet which introduces the composition (A Sive, of shelter maketh show; / But ev'ry Storme will through it goe; Wither, 1635, p. 20) immediately narrows down its content transforming it into a meditation on false appearances: no hermeneutic initiative is elicited from the reader, no stretching of imagination is encouraged, no conflictual conceptualization is triggered, no intertextual allusion to a distraught love passion is possible: the attention of the reader is just focused on the sieve which is taken in its exclusively material meaning as an ineffective shelter, not as a polysemous symbol of transience. The narrative character of the accompanying text is restricted and contained, aiming at conveying a single, central idea, the illogical action of the young man as a moral illustration of another illogical behavior which must be censored (hypocrisy). Visual and verbal are not put together and left free to interact in unpredictable ways: their association is governed by a methodical and rigid criterion and each detail is given a precise meaning. In short, there is no centrifugal input for the reader to start from the composition and infer or build new meanings, there is just a centripetal force which gets stronger and stronger in conveying and guiding the reader's attention and interpretation of a text in which pre-eminence is given to the verbal part, while the visual component is more and more relegated to the function of mere illustration.

Figure 2. From Wither (1635, p. 20).

The underlying principle of the composition, therefore, is an attenuating pursuit of equivalence based on similarity. There is no metaphorical conceptualization which deploys conflictual projection to valorise possible dialogical openings, no different interpretations of the compositions, no alternative meanings produced by the multi-layered image. The metaphorical nature of the sieve is clearly expressed, transformed into a comparison with a clear moral content. Even the possible ambiguity of the motto is here exclusively interpreted in its negative literal meaning (water flows through a sieve so the man you see here is doing something absurd) whereas in Rollenhagen's composition it was the element which triggered the surprising, positive idea that everything passes.

And yet, the choice itself of a long, severe reproof on those who “for their Actions … procure/A likely colour” (ll. 1-2) ironically reverberates on the author himself and his book. The “Preposition to this Frontispiece ” which opens the Collection, for example, features a clearly antiphrastic strategy which apparently dismisses and disclaims the carefully crafted design and metaphorical richness of the image (made by the famous engraver William Marshall):18 the original design was to be a “plaine Invention” whereas the image is a worthless misinterpretation of the author's true intention. On second thought, however, “Those Errors, and Confusions, which may, there, / Blame-worthy (at the first aspect) appeare” turned out to be fit and usable because the “Graver (by meere Chance) had hit / On what, so much transcends the reach of Wit, / As made it seeme, an Object of Delight”, so much so that the reader is even invited to watch more carefully and try to decipher the meaning of the enigmatic picture:

And, here it stands, to try his Wit, who lists

To pumpe the secrets, out of Cabalists.

… Moreover, tis ordain'd,

That, none must know the Secrecies contain'd

Within this Piece; but, they who are so wise

To finde them out, by their owne prudencies;

And, hee that can unriddle them, to us,

Shall stiled be, the second Oedipvs.

Wither's initial rhetoric of disowning is, thus, a contrived but conventional form of authorizing and commending his book, a formula of mock-modesty which aims at underscoring the value of his highly wrought artifact. A similar effect is obtained by the ambiguous, double-dealing strategy in the warning “To the Reader”: on the one hand, the author stresses that he has “ever aymed, rather to profit my Readers, than to gaine their praise” (sig. Av) and that his written intervention rescued and dignified the original “dumbe Figures, little usefull to any but to young Gravers or Painters; and as little delightfull, except, to Children, and Childish-gazers: they may now be much more worthy; seeing the life of Speach being added unto them, may make them Teachers, and Remembrancers of profitable things” (sig. A2). On the other, he admits that his “Illustrations” are the first that came to his mind, susceptible of improvement and limited by the formal requirements of the printed page:

I have not so much as cared to find out their meanings in any of these Figures; but, applied them, rather, to such purposes, as I could thinke of, at first sight; which, upon a second view, I found might have beene much betterd, if I could have spared time from other imployments. Something, also, I was Confined, by obliging my selfe to observe the same number of lines in every Illustration; and, otherwhile, I was thereby constrained to conclude, when my best Meditations were but new begunne: which (though it hath pleased Some, by the more comely Vniformitie, in the Pages) yet, it hath much injured the libertie of my Muse. (sig. A2)

Also, the highly rhetorical “Authors Meditation upon Sight of his Picture” which closes the introductory material, is yet another occasion for Wither to dislocate his authority and role in order to celebrate them.19

This whole strategy, then, does not seem to testify to an “awkward relationship of the author to his material” (Bath, 1994, p. 129): the symbolical images of the frontispiece and of the various emblems in the book can be acceptable only after they have been deconstructed in their literal, face value. But the ultimate purpose is not just to make a sophisticated self-celebration to extol the validity of what the reader has in front of him. As Wither openly admits, he does not think his “Illustrations … will be able to teach any thing to the Learned”, whereas

they that have most need to be Instructed, and Remembred, (and they who are most backward to listen to Instructions, and Remembrances, by the common Course of Teaching, and Admonishing) shall be, hereby, informed of their Dangers, or Duties, by the way of an honest Recreation before they be aware (sig. A2).

In other words, his text (a collection of 200 emblems assembled in a single, wonderfully illustrated volume which clearly only the rich and learned could afford) is for those who refuse instruction and the common forms of teaching and warning, that is, exactly those learned men mentioned above who need a more sophisticated and radical tuition: they will be honestly recreated (entertained, but also re-created) without even realizing it.

One would be tempted to say that the same accusation of falsity and hypocrisy which emblem 20 stigmatizes so vehemently is in fact one of the structural principles on which the whole Collection is built: the author's moralistic denunciation of insincerity and pretense is not very different from the folly of those who use a sieve as a shelter, both are actions “Through which, their purposes at length are spyde” (l. 24).

4. Conclusion

The idea of emblems and imprese as dislocating iconotextual constructs positively contributes to unsettling some critical judgments traditionally passed on them and grasp their genuine cognitive potential. In particular, emblematics' relationships with metaphor are an extremely fruitful field of investigation touching some fundamental epistemological underpinnings of early modern textuality. The metaphorical affiliations of emblematic compositions entailed a much deeper and more sweeping relationship than a general, predictable similarity between symbolical forms of expressions; for this reason, as this article tried to demonstrate, a stylistic approach to emblematics and its use of conflictual metaphorical conceptualizations seems particularly rewarding and goes a long way toward accounting for a textual form whose idiosyncratic meaning procedures ushered in an idea of communication as projective and dislocating, as a dialogic space allowing for the paradoxical copresence of ideological consistency and its deconstruction.

Undoubtedly, the “didactic turn” which made emblematic texts more and more descriptive caused an inversely proportional reduction of the reader's hermeneutic intervention: no metaphorical effort was invited; the idea of a meaning in progress was superseded; the text was no longer a starting point but the arrival of a meaning process which was set out and imposed from the outset. The emblematic text, in other words, progressively lost its allusive and stimulating aspects, forsaking symbolization in favor of description, becoming more and more exhaustive in order to stave off alternative interpretative possibilities: as Miller (1992, p. 69) perfectly summarizes in his discussion on illustration, “The elucidation of the graphic would interfere with the free growth of the verbale illustration, shade it, stunt it.”

Later writers simply exploited the representative power of visual and verbal elements, leaving the cognitive dimension of their structural union aside: the teeming multiplicity of symbolical signification got attenuated and the verbal part was assigned the guiding role of providing the correct interpretation of the image. On the one hand, by describing and explaining what was already visible, the accompanying words did not aim at shifting signification to a different level. On the other hand, the image was made into a pleasing illustration to help memory and strike the imagination, emptied out of its signifying potentials, more and more an anchorage than a relay. The original, swarming relationship between emblematics and metaphor was thus radically revised and morphed into something completely different.

However, the manifold opportunities provided by the emblematic form could not be perfectly contained and, for this reason, the article also tried to shed light on some hermeneutic and ideological questions, drawing on some of the textual-conceptual functions analyzed by critical stylistics. The specific connotations, presuppositions and implicatures emerging from the different metaphorical conceptualizations discussed above encouraged the discussion of the positionings and negotiations of authors who variously dealt with the inherently plural modes of emblematic signification. Similarly, the insistence on the bimedial nature of emblematics and the importance of its integrated model of textual meaning-making is clearly redolent of multimodal studies focusing on how different semiotic resources and modes are integrated in their communicative functions and how representational and communicational modes are intrinsically connected.20

Of course, the article would have benefited from the investigation of a greater number of exemplary case studies and from more diverse critical methods, but such additions would have required more space than the one allowed for the present paper. The ideas presented here, however, hopefully proved that such complex, multifaceted textual forms as emblems and imprese require an equally wide critical approach, in which stylistics and metaphor studies may be fruitfully deployed in a synergetic way. Their joint use might also be integrated and supplemented with the insights and critical tools of corpus linguistic methodologies, text world theory, critical metaphor analysis, or social semiotics, in order to develop a larger theoretical framework and open up new perspectives to account for the cognitive, hermeneutic, and ideological richness of emblematics.21

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Funding

Local research funds (BORD_RILO_21_01)—Dipartimento di Studi Umanistici.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^The term will be used throughout the essay to allude to the symbolical form which was concretely embodied by emblems and imprese. The difference between the two is not easy to draw as confirmed by the title of the famous collection by the German Gabriel Rollenhagen, Nucleus emblematum selectissimorum. Quae Itali vulgo impresas vocant (Rollenhagen, 1611). In this paper the two terms will be used in their customary meanings: an impresa was a symbolic composition made up of a motto (inscriptio) and a (usually symbolic) image (pictura), had a strictly personal and programmatic character (hence its name) and it was tied to specific circumstances; the emblem had a motto, a symbolic image and an accompanying, longer text (subscriptio) which emphasized its more didactic and general character. The bibliography on emblematics is huge: see the classic studies by Gombrich (1948), Praz (1964) and the more recent ones by Russell (1985, 1995), Bath (1994), Pinkus (1996), Spica (1996), Manning (2002), Visser (2005), Graham (2016, 2017), and Benassi (2018), which offers the most updated discussion on this topic.

2. ^Ammirato (1562, p. 32) stressed that the “meraviglia” of an emblematic construct was produced by the coupling of two intelligible entities which produce something new, which is not that particular verbal or visual part but “quel misto, o terzo, che risulta, & nasce dalla sentenza, et dalla cosa, o imagine riceuuta” (that mix, or third element, which derives and was born from the saying and the thing or received image. All translations are mine unless specified otherwise). Bargagli (1594, p. 14) made a sort of genealogy of the various “modi vsitati dall'huomo, del palesare i propi concetti suoi” (wonted ways employed by men to reveal their conceptions) culminating with imprese “questo eccellente mostro di Natura fabbricando opere di figure di cose, e di voci insieme” (this excellent monster of Nature by contriving works which join figures of things and of voices together). Tesauro as well highlighted the novelty of imprese claiming that they were born together with poetry and painting but with a special cognitive capacity, since the poetic quality of this “sign” made it “più nobile” (nobler) and “più difficile” (more difficult), overcoming all the other persuasive arts (Tesauro, 1670, p. 625).

3. ^On these aspects see Klein (1957).

4. ^Le Moyne (1666, p. 11) was outspoken in associating the synthetic quality of emblematics to divine communication: “Surquoy, si je ne craignois de monter trop haut, & d'en dire trop, je dirois qu'il est de la Devise en cela, comme de ces images universelles données aux Esprits superieurs, qui representent en un moment, et par une notion simple & degagée”.

5. ^As Barthes (1977) suggested, in relay texts words and images stand in a complementary relationship which ultimately guarantees the unity of the message and its performance as a meaningful story. Anchorage, on the contrary, characterizes those texts in which the linguistic message no longer guides identification but the interpretation of the images they refer to, constituting a kind of vice which guides the text and limits the projective power of the image.

6. ^The bibliography on Conceptual Metaphor Theory is broad. Apart from such fundamental classics as Lakoff and Johnson (1980) and Lakoff and Turner (1989), most ideas and theoretical issues are usefully summarized by Kövecses (2015).

7. ^Bargagli (1594, p. 37) saw the impresa as an “espressione di singolar concetto d'animo, per via di similitvdine” (expression of a singular concept of the soul, by way of similitude). Similarly, Capaccio (1592, p. 53r) averred that an impresa was “fondata nella Comparatione” (founded on comparison) and that comparison was “quasi forma dell'Impresa” (almost the form of the impresa; 71r). Taegio (1571, p. 16r) suggests that the meaning and noble concept of an impresa is visible “sotto il vago, leggiadro, & trasparente velo d'una accomodata similitudine” (under the charming, lovely and transparent veil of a convenient similarity).

8. ^An inconsistent sentence “violates no formal distributional restriction. On the contrary, it is precisely its formal scaffolding, which is insensitive to the pressure of the connected concepts, that gives a sentence the strength to put together atomic concepts in a creative way” (Prandi, 2017, p. 56).

9. ^As Russell (1985, p. 31) reminds, in France devices tended to be simpler and endowed with practical functions, whereas in Italy imprese “tended to be more abstract, complex and conceit-like” and theoretical discussions were accordingly more widespread because of the wider range of symbolic motifs and the higher complexity of their interaction between verbal and visual parts.

10. ^Ruscelli (Giovio, 1556, p. 208) was particularly exacting as to the necessary coexistence of words and images intertwined in an analogical relationship, so that figures without mottos (or vice versa) did not mean anything and only “insieme uengano à rappresentare interamente l'intentione dell'Autor dell'Impresa” (together they come to represent fully the intention of the author of the impresa). Ammirato (1562, p. 10), too, stressed the link between words and images defining an impresa as a significant form “sotto un nodo di parole, & di cose” (under a knot of words, and things). On the various aspects of the body-soul dichotomy see the monographic issue of Emblematica (2002).

11. ^An emblematic creation was, by definition, co-created by the author and the reader and its impact as work of art was coproduced, confirming that “Relations are not just modes of regulation or encroachment, but inescapable conditions of being. In short, attachment and mediation are not obstacles to art's agency but essential preconditions of agency” (Felski, 2017, p. 169). On the concept of agency see Gell (1998).

12. ^On this see especially Mitchell (1986) and Gilman (1989).

13. ^On iconotexts see also Louvel (2011).

14. ^Being strictly personal and temporary statements, imprese were more prone to rely on metaphorical conceptualization, but something similar also happened to them: Paradin (1551) was a mere presentation of devises with just the motto and the image. Paradin (1557), however, radically changed the nature of the book: longish explanations were added to provide background information on the bearers of each impresa and a moralistic interpretation of the composition.

15. ^Whitney, for example, reminded his readers that obscurity amplifies the pleasure of discovering and understanding maintaining that the emblem is “some wittie deuise expressed with cunning woorkemanship, somethinge obscure to be perceiued at the first, whereby, when with further consideration it is vnderstood, it maie the greater delighte the behoulder” (Whitney, 1586: To the Reader). Stirry, in the ideologically rife year 1641, presented his emblematic book to his “iudicious Reader” as an “Aegyptian Dish drest after the English Fashion” (Stirry, 1641, sig. A2), resorting to the usual metaphor and rhetoric of the pleasant and mysterious symbolical composition even though his evident purpose was to level a bitter attack against the Church of England and to impose a very precise set of values on his readers.

16. ^On these aspects see Falque (2017).

17. ^From this point of view the emblem is similar to n. 26, which curiously presents a similar image with a squirrel patiently enduring a heavy rain, and to emblem 82 in Rollenhagen (1613), the collection which provided the materials for Wither's Books 3 and 4.

18. ^For a full analysis of the frontispiece see Bath (1994, pp. 111-15).

19. ^This feature of Wither's volume did not pass unnoticed even in its own times: in his 1644 poem Aqua Musae, John Taylor, the “water poet” (Bath, 1994, p. 129) attacked Wither for being a sort of turncoat and reinforced this accusation by denouncing Wither's distancing from his books: “Thy picture to thy bookes was printed, put / With curious workmanship engrav'd and cut: / And verses under it, were wisely pend/Which fooles suppos'd were written by some friend. / Which God knowes, thou, I, and a thousand know, / Those lines (thy selfe praise) from thy selfe did flow, / Thou dotedst so upon thine owne effigies, It look'd so smugge, religious, irreligious, / So amiable lovely, sweet and fine, / A phisnomie poetique and divine: / 'Till (like Narcissus) gazing in that brook, / Pride drown'd thee, in thy selfe admiring book”.

20. ^On critical stylistics see Jeffries (2010). On multimodal analysis see Kress and Van Leeuwen (1996), O'Halloran and Smith (2011), and Jewitt et al. (2016).

21. ^For a recent survey on corpus stylistics see McIntyre and Walker (2019). On text world theory see Gavins (2007) and Gavins and Lahey (2016). On critical metaphor analysis see Charteris-Black (2004). On social semiotics see Van Leeuwen (2005). For some tentative steps in the direction of using a stylistic approach to emblematics see Borgogni (2015, 2019).

References

Bath, M. (1994). Speaking Pictures. English Emblem Books and Renaissance Culture. London; New York, NY: Longman.

Benassi, A. (2018). “La filosofia del cavaliere”. Emblemi, imprese e letteratura nel Cinquecento. Lucca: Maria Pacini Fazzi Editore.

Black, M. (1962). “Metaphor”, in Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society 55, 1954, 273–294, reprinted in M. Black, Models and Metaphors: Studies in Language and Philosophy. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Borgogni, D. (2015). Stylistics and emblematics: accounting for the evolution of English emblematics from a relevance theoretic perspective. Quaderni di Palazzo Serra 27, 93–129.

Borgogni, D. (2019). Discourse and representation in emblematics: hermeneutic and ideological implications of stylistic and cognitive analyses” Linguist. Literat. Stud. 2, 75–86. doi: 10.13189/lls.2019.070206

Carston, R. (2010). Metaphor: ad hoc concepts, literal meaning and mental images. Proceed. Aristotel. Soc. 110, 295–321. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9264.2010.00288.x

Charteris-Black, J. (2004). Corpus Approaches to Critical Metaphor Analysis. New York, NY: Macmillan.

Emblematica (2002). Volume 12. Monographic issue on Body and Soul: Papers from the 26th Annual Conference of the Association of Art Historians, eds P. M. Daly, D. Russell, D. Graham, and M. Bath (New York, NY: AMS Press).

Falque, I. (2017). Geert grote and the status and functions of images in meditative practices. GEMCA Papers Progress 4, 15–28.

Gavins, J., and Lahey, E., (eds.) (2016). World Building. Discourse in the Mind. London; New York, NY: Bloomsbury Academic.

Gilman, E. B. (1978). The Curious Perspective. Literary and Pictorial Wit in the Seventeenth Century. New Haven, CT; London: Yale University Press.

Gilman, E. B. (1989). Interart studies and the ‘imperialism' of language. Poetics Today, Art Literat. 10, 5–30. doi: 10.2307/1772553

Giovio, P. (1556). Ragionamento di Mons. Paolo Giovio … Con un Discorso di Girolamo Ruscelli intorno allo stesso soggetto. Venezia: Ziletti.

Gombrich, E. H. (1948). Icones symbolicae. The visual image in neo-platonic thought. J. Warburg Courtauld Instit. 11, 163–192. doi: 10.2307/750466

Graham, D. (2016). ‘Piece out our imperfections with your thoughts': Lessons from the History of Emblem Studies. Emblematica 22, 1–42.

Graham, D. (2017). Preface, prescription, and principle: the early development of Vernacular Emblem Proto-theory in France. Janus 6, 1–31.

Jewitt, C., Bezemer, J., and O'Halloran, K. (2016). Introducing Multimodality. Abingdon; New York, NY: Routledge.

Klein, R. (1957). La théorie de l'expression figurée dans les traités italiens sur les imprese, 1555-1612. Bibliothèque d'Humanisme et Renaiss. 19, 320–342.

Kövecses, Z. (2015). Where Metaphors Come From. Reconsidering Context in Metaphor. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kress, G., and Van Leeuwen, T. (1996). Reading Images: The Grammar of Visual Design. London; New York, NY: Routledge.

Lakoff, G., and Turner, M. (1989). More than Cool Reason. A Field Guide to Poetic Metaphor. Chicago, IL; London: The University of Chicago Press.

Le Moyne, P. (1666). De l'art des devises. Paris: chez Sebastien Cramoisy, and Sebastien Mabre Cramoisy.

McIntyre, D., and Walker, B. (2019). Corpus Stylistics. Theory and Practice. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Mermoz, G. (1989). “Rhetoric and episteme: writing about ‘art' in the wake of post-structuralism”. Art History 12, 497–509. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8365.1989.tb00372.x

Mitchell, W. J. T. (1986). Iconology. Image, Text, Ideology. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

O'Halloran, K. L., and Smith, B. A., (eds.) (2011). Multimodal Studies. Exploring Issues and Domains. Abingdon; New York, NY: Routledge.

Pinkus, K. (1996). Picturing Silence. Emblem, Language, Counter-Reformation, Materiality. Ann Arbor, MI: The University of Michigan Press.

Prandi, M. (2017). Conceptual Conflict in Metaphors and Figurative Language. New York, NY: Routledge.

Praz, M. (1964). Studies in Seventeenth-Century Imagery. 2nd edn. Roma: Edizioni di Storia e Letteratura.

Ricœur, P. (2003). The Rule of Metaphor. The Creation of Meaning in Language. London; New York, NY: Routledge.

Rodowick, D. N. (2001). Reading the Figural, Or Philosophy after the New Media. Durham; London: Duke University Press.

Rollenhagen, G. (1611). Nucleus Emblematum Selectissimorum. Quae Itali vulgo impresas vocant. Coloniae: apud Io[n]ne[m] Iansoniu[m] bibliopola[m] Arnhemie[n]se[m].

Rollenhagen, G. (1613). Gabrielis Rollenhagii Selectorum Emblematum Centuria Secunda. Coloniae: apud Io[n]ne[m] Iansoniu[m] bibliopola[m] Arnhemie[n]se[m].

Russell, D. (1995). Emblematic Structures in Renaissance French Culture. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press. doi: 10.3138/9781442623477

Spica, A.-E. (1996). Symbolique humaniste et emblématique. L'évolution et les genres (1580-1700). Paris: Honoré Champion Éditeur.

Stirry, T. (1641). A rot amongst the bishops: or, A Terrible Tempest in the Sea of Canterbury, Set Forth in Lively Emblems to Please the Judicious Reader. London: R.O. and G.D.

Visser, A. S. Q. (2005). Joannes Sambucus and the Learned Image: The Use of the Emblem in Late-Renaissance Humanism. Leiden: Brill.

Wagner, P., (ed.). (1996). Icons-Texts-Iconotexts: Essays on Ekphrasis and Intermediality. Berlin; New York, NY: de Gruyter.

Wilson, T. (1909). Arte of Rhetorique (ed. by G. H. Mair), fac-simile of the 1560 edition. Oxford: Clarendon.

Keywords: emblem, impresa, conflictual metaphor, early modern textuality, critical stylistics, representation and communication, multimodality

Citation: Borgogni D (2023) Emblematics and metaphor: theoretical facets and hermeneutic issues. Front. Commun. 8:1176742. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2023.1176742

Received: 28 February 2023; Accepted: 07 April 2023;

Published: 26 April 2023.

Edited by:

Ilaria Rizzato, University of Genoa, ItalyReviewed by:

Aoife Beville, University of Naples “L'Orientale”, ItalyDonatella Montini, Sapienza University of Rome, Italy

Valerie Marie Anne Hayaert, University of Warwick, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2023 Borgogni. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Daniele Borgogni, ZGFuaWVsZS5ib3Jnb2duaUB1bml0by5pdA==

Daniele Borgogni

Daniele Borgogni