- 1Psycholinguistics and Cognition Lab, Concordia University, Montréal, QC, Canada

- 2Research Group on Language, Action and Thought, Donostia-San Sebastián, Spain

Some theorists argue that Grice's account of metaphor is intended as a rational reconstruction of a more general inferential process of linguistic communication (i.e., conversational implicature). However, there is a multi-source trend which treats Grice's remarks on metaphor as unabashedly psychological. The psychologized version of Grice's view runs in serial: compute what is said; reject what is said as contextually inappropriate; run pragmatic processing to recover contextually appropriate meaning. Citing data from reaction time studies, critics reject Grice's project as psychologically implausible. The alternative model does not rely on serial processing or input from what is said (i.e., literal meaning). I argue the serial processing model and its criticisms turn on a misunderstanding of Grice's account. My aim is not to defend Grice's account of metaphor per se, but to reinterpret auxiliary hypotheses attributed to him. I motivate two points in relation to my reinterpretation. The first point concerns the relationship between competence and performance-based models. To the second point: Several of the revised hypotheses make predictions that are largely consistent with psycho and neurolinguistic data.

1. Introduction

Grice did not say much about metaphor. What he did say about it followed almost entirely from his treatment of conversational implicatures (CIs). Nevertheless, this has not prevented widespread circulation of the phrase “Gricean model” within certain streams of metaphorology.1 Grice's account of metaphor is important to those of us working in metaphor research for at least two reasons. First, it engenders an analytic claim about rational conversational practices. Second, it naturally lends itself to be understood as generating certain testable hypotheses. The usual criticisms of the performance model are that it falsely predicts that certain processes are carried out during comprehension, and that the processes in question are psychologically implausible. In this article, I detail the criticisms leveled against the performance model. I argue that the criticisms turn on a strawman of Grice's competence model. I demonstrate this by carefully weighing Grice's rational program against the empirical model it allegedly engenders. I endeavor to establish empirical claims that are in fact warranted by Grice's rational account. To do this, I ask whether the task can be carried out in good faith, and whether it can provide researchers with an alternative, empirically useful account of metaphor processing.

To anticipate my general conclusion, I claim that Grice's comments on metaphor are useful in developing an alternative empirical model that can withstand criticisms launched against its manifestation as the “indirect access model” (hereafter: indirect model).2 This opens the possibility of developing an empirically oriented, roughly, but deeply Gricean research program.3

To my estimation, there are at least two core assumptions over which disputes of metaphor processing are raised. The first is the temporal equivalence claim, the second is the cognitive equivalence claim. The temporal claim refers to the time course of processing metaphorical and literal sentences. The cognitive claim refers to the generality of the cognitive mechanism(s) involved in processing metaphorical and literal sentences. I briefly discuss these claims below. I return to them in subsequent sections.

Grice's account of metaphor has been attacked on two fronts as psychologically implausible: On one front, it is criticized by psychologically oriented pragmatic accounts (e.g., Stern, 2000; Bezuidenhout, 2001; Recanati, 2001; Hills, 2004; Carston, 2008; Sperber and Wilson, 2008; Nogales, 2012), and on the other front by psycho- and Cognitive Linguistics (e.g., Lakoff and Johnson, 1980; Gibbs, 1990; Gibbs and Tendahl, 2006; Thibodeau and Durgin, 2008).4

I follow influential scholarship (Gibbs, 1994; Coulson and Matlock, 2001; Camp, 2006c; Bambini and Resta, 2012; Weiland et al., 2014; Bambini et al., 2016, 2021; Rapp et al., 2018; Patalas and de Almeida, 2019; Pissani and de Almeida, 2022) in referring to this group as “direct access theorists”. I acknowledge that there is a diversity of positions amassed under this banner.5 I focus on their commonalities. Direct access theorists support and promote a “direct access model” (hereafter: direct model) of metaphor interpretation. The direct model is marketed as a psychologically plausible competitor to the indirect model.

Patalas and de Almeida (2019) provide a useful description of the debate over these two models in the empirical literature. According to them, direct access theorists claim that, like literal sentence processing, “metaphors are immediately comprehensible by the linguistic system” (Patalas and de Almeida, 2019, p. 2530—italics mine). Regarding the temporal claim, direct access theorists are committed to the idea that literal and metaphorical sentence processing occur in the same time course. The way in which direct theorists specify the cognitive claim is captured in the following quote by Rumelhart:

The distinction between literal and metaphorical language is rarely, if ever reflected in a qualitative change in the psychological processes involved in the processing of that language. (Rumelhart, 1993, p. 72—italics mine)6

By contrast, the indirect model predicts that metaphors take longer to process than literal control items, and that metaphor comprehension requires additional cognitive processing in comparison to literal control items. I argue that the indirect model is the result of equivocating the pragmatic logic of implicature interpretation with an empirical comprehension procedure (Saul, 2002b; Reimer, 2013). The latter carries assumptions that cannot reasonably be attributed to the former. For this reason, I refer to the indirect model as a strawman.

I defend the Gricean model by rejecting a subset of the auxiliary hypotheses attributed to it. The Gricean strawman, I claim, is the result of misconceptions concerning CIs. However, I do not defend Grice's project in all its details. I acknowledge and identify several shortcomings with Grice's rational model and my reinterpretation of the performance model.

The article is laid out in the following way: In Section 2, I provide Grice's brief comments on metaphor. I raise several issues with it. I bracket some to focus on those relevant to my present aims. Section 3 provides illustrations of the commitments and predictions of the indirect and direct models. I discuss the aims of Gricean pragmatics, the logic of CIs—and by extension, metaphor. Section 4 is the pivot of the article. Guided by discussions in the previous sections, I circumvent the strawman by reinterpreting Grice's view in a more empirically charitable way. I specify auxiliary empirical hypotheses that more accurately reflect the rational model. Section 5 surveys current psycholinguistic evidence on metaphor processing. The data collected from this survey allows me to compare the direct model with the revised Gricean model. Section 6 highlights those aspects of Grice's theory of metaphor that are in want of elaboration, and where it simply goes wrong. Section 7 offers some concluding remarks.

2. Grice and metaphor

Nearly all that Grice had to say about metaphor is found in a few short passages in “Logic and Conversation”. His treatment of metaphor is an extension of the more general discussion of CIs, the Cooperative Principle (CP), and its attendant maxims of conversation. This framework provides a tool for understanding how discourse participants negotiate meaning beyond an utterance's semantic profile.

According to Grice, speakers intend for their audience to recognize the content of a CI guided by mutually shared rational principles and maxims of conversation, sophisticated patterns of reasoning about the mental states of interlocutors, particular facts about the meaning of the sentence uttered (implicating their semantic competence), and the context of utterance (implicating their pragmatic competence). Grice wrote:

Metaphor. Examples like You are the cream in my coffee characteristically involve categorical falsity, so the contradictory of what the speaker has made as if to say will, strictly speaking, be a truism; so it cannot be THAT that such a speaker is trying to get across. The most likely supposition is that the speaker is attributing to his audience some feature or features in respect of which the audience resembles (more or less fancifully) the mentioned substance. (Grice, 1975, p. 53)

Grice's just-quoted single example of a metaphor is “You are the cream in my coffee”.7 He claims that the speaker flouts the maxim of Quality and thereby conversationally implicates some further proposition where the intended meaning “more or less fancifully' resembles the cream in the speaker's coffee. So, for Grice, a speaker utters a sentence, that p (“You are the cream in my coffee”), whose meaning is fixed by the conventional meaning of the constituent words in the utterance. The speaker makes it obvious to the listener that her main communicative intent is to convey something different, that q (e.g., “you are an important part of my life”, etc.) given mutually shared assumptions made relevant by the sentence uttered and the context in which it occurs.8

Here, I would like to describe several issues that philosophers of language have voiced with Grice's formulation and to clarify my own position on their importance and relevance to the aims in this article.

First, Grice assumes that speakers flout the maxim of Quality to produce a metaphor. Some commentators suggest that this requires deliberate and rational thinking process that are psychologically implausible. As Recanati (2001) has pointed out, the interpretation of many metaphors does not seem to require lengthy, on-line reasoning processes to determine their meaning. However, it is also true that novel, creative and poetic metaphors often involve more explicit reflection to grasp their complex and nuanced meaning. A general theory of metaphor must account for these observations. So far, Grice's view seems to intuitively capture only poetic and novel metaphors.9

There is a second and related worry to the previous point concerning novel, creative and poetic metaphors. Pragmatic theories in general—not simply Grice's—fail to address the fact that metaphors are often used to bring about psychological effects that are not easily captured in truth-conditional terms. Often, metaphors serve as tools to induce new ways of thinking and feeling about some topic (Davidson, 1978; Camp, 2003, 2006b, 2008). Case in point, Grice's own example above evokes a complex and nuanced set of attitudes and imagistic qualities of the speaker's intended referent. Failure to account for this fact points to a lack of explanatory resources in Grice's account that are needed to make sense of the array of communicative effects other than the transmission of propositional content (Camp, 2003, p. 39–40). Because we systematically use language to convey more than propositional content, we need some reasoned explanation of this ability.

A third problem is the vagueness of Grice's account of the rhetorical figures more generally. He tells us that the interpretation of metaphor and other figurative uses of language, such as irony and hyperbole involve calculating some related, speaker-intended meaning. What is unclear is how listeners discriminate between the various tropes. In other words, Grice's account underspecifies the interpretation procedure.10

Fourth, Grice tells us a speaker is “making as if to say” something categorically false in uttering a metaphor. Yet, Grice's own remarks suggest, and some of his commentators seem to agree, that implicatures arise when the speaker gets across more than she says. More precisely, implicatures are carried by the saying of what is said. However, making as if to say is a case in which nothing is said. If so, we need a story that tells us what caries the metaphorical meaning.11

Fifth, it is not a necessary condition that a metaphorical utterance be “categorically false” on a literal reading. In some cases, an utterance is “semantically unimpeachable but can still be used metaphorically” (Camp, 2003, p. 6). For some metaphors, the question of truth does not come into play. To illustrate this point, consider a twice-true metaphor (1),12 a negative metaphor (2),13 and an imperative metaphor (3):

(1) Moscow is a cold city.

(2) Bill is not a wolf.

(3) Go out there floating like a butterfly and stinging like a bee!

In each example, the speaker does not mean what is literally encoded, but intends the listener to interpret the utterance metaphorically. In (1) the literal meaning is true. Examples (2) and (3) do not convey a true affirmative proposition. (2) is a negation, and what is said is true, while (3) is an imperative so that there is no proposition being asserted. If a metaphorical meaning is triggered by its blatant falsehood, then Grice's account does not provide us with any explicit way to deal with cases where some expression is intended metaphorically but is not a categorically false statement.

Sixth, most theories of metaphor (including Grice's) tend to focus on the standard, predicative nominal [a is (an) F] structure. However, metaphors vary from this template which may in fact introduce a whole series of interpretive complexities for pragmatic models. Consider a non-exhaustive list of some of these lesser-studied metaphorical structures: 14

(4) Odysseus has returned home.

The above represents an example of a metaphorical use of a (fictional) proper name.

(5) A sharp mind can solve this problem.

The above represents an example of an adjectival metaphor.

(6) The sun blazes bright today; the clouds flee from his mighty beams.

The above represents an example of a sentential metaphor where the target is not explicitly mentioned (Camp, 2006c, p. 161). With the right supportive context, however, we can interpret (6) as a description of Achilles on the battlefield.15

Finally, Grice's account has no obvious answer to the unidirectionality problem of metaphor interpretation. Consider the following set of utterances:

(7) Some surgeons are butchers.

(8) Some butchers are surgeons.

The propositions expressed by (7) and (8) are logically equivalent: (∃x)(Sx&Bx) = (∃x)(Bx&Sx). If what is said is the truth-conditional content, one must conclude that what is said is the same in both cases. However, what is said can be more than truth-conditional content. Bach (1994) has suggested that what Grice has in mind by what is said should be taken as a structured proposition:

(7s) [SOME, [CONJ, [[x is a surgeon], [x is a butcher]]]

(8s) [SOME, [CONJ, [[x is a butcher], [x is a surgeon]]]

SOME is the property of being a non-empty set, CONJ is the truth function of conjunction. Commutativity of conjunction is a law of classical logic. So, it is difficult to determine how these propositions are different. If they express the same structured proposition, then what is said is the same in both cases. If these two utterances say the same thing, and what is said carries the implicated content, then how can (7) and (8) generate different interpretations? In other words, how can (7) implicate something negative about surgeons, whereas (8) implicates something positive about butchers?16

Despite these issues, they do not undermine the general picture I aim to develop: I am not interested in ironing out what Devitt (2021) refers to as the “metaphysics of the meaning-properties” (i.e., I am not interested in addressing the question “what is a metaphor?”), nor am I interested in what speakers do in uttering a metaphor. Rather, I am interested in investigating how listeners generate metaphorical meaning.17 Thus, only issues one to three will be of concern to me in what follows. On a related note, I do not enter the Literalist-Contextualist controversy on the place of metaphor in interpretation.18 I leave it to the reader to decide whether my interpretation of Grice comports well with views that treat metaphor as a species of implicature, if its implicature-adjacent or something else altogether.

3. The psycholinguistic strawman

In general, it is assumed that metaphorical interpretations, like other conversational inferences (e.g., scalar implicatures, conversational implicatures, etc.), involve a stage of computation where the listener generates inferences about the speaker's attitudes and communicative intentions.19 I mentioned that Grice's theory of metaphor begins from the intuition that in speaking metaphorically, speakers undertake speech acts conveying contents that are distinct from the linguistic meaning of the sentence uttered. Thus, to interpret the metaphor, the listener reasons through several pieces of input including what they assume are the speaker's manifest communicative attitudes and intentions, the conventional meanings of the words uttered, their mode of combination, and the broader conversational context.

Grice's project is often criticized for being too psychologically complex. This criticism turns on a mischaracterization of CIs (Saul, 2002b; Camp, 2003; Bach, 2006; Moore, 2014; Geurts and Rubio-Fernández, 2015). Grice never speculated about psychological process nor the “temporal development of cognitive processes behind metaphor” (Bambini and Resta, 2012). Nevertheless, Grice's rational reconstruction of the pragmatic logic involved in communication “paved the way to a consideration of pragmatics at the interface between language and cognition” (Bambini and Resta, 2012). But so-called “cognitive pragmatics” is psychological. One highly influential research program aimed at developing a comprehensive, cognitively oriented pragmatics is Relevance Theory.20 According to these folks,

“pragmatics” is a capacity of the mind, a kind of information-processing system, a system for interpreting a particular phenomenon in the world, namely human communicative behavior[…] It is a proper object of study itself, no longer to be seen as simply an adjunct to natural language semantics. (Carston, 2002a, p. 128–129)

The components of the theory are quite different from those of Gricean and other philosophical descriptions; they include online cognitive processes, input and output representations, processing effort and cognitive effects. (Carston, 2002a, p. 129)

Here, Carston underlines the differences between the components and object of study in pragmatics for RT and those for Grice. Of course, one may disagree with what pragmatics ought to study, and how one ought to study it, but such disagreements are not per se an indictment of Grice's own project qua rational model: The two approaches may peacefully coexist—in principle. So, what of the controversy? Consider Wilson (2000) remarks on Grice's claims about deriving conversational implicatures (and by extension, metaphors). She writes:

Grice seems to have thought of the attribution of meaning as involving a form of conscious, discursive reasoning […] It is hard to imagine even adults going through such lengthy chains of inference in the attribution of speaker meanings. (Wilson, 2000, p. 415–416—italics mine)

Geurts and Rubio-Fernández identify three assumptions (read: misconceptions) at work in Wilson's understanding of Grice project:

(1) Gricean pragmatics adopts a mentalistic stance in the sense that it is concerned with the internal states and processes underlying interpretation.

(2) These states and processes are available to consciousness.

(3) It's all way too complicated: in reality, interpretative processes are a lot simpler than Grice would have us believe.

Millikan (1984, p. 69), Sperber and Wilson (1995), and Origgi and Sperber (2000) raise similar issues about Gricean communication arguing that it is a non-starter because it involves intentions about intentions, etc., and the recognition of all these higher-order intentions on the part of the listener. Even though some proponents of RT seem to acknowledge that Grice was concerned with the pragmatic logic, we observe elsewhere the equivocation between defining his rational model of metaphor interpretation with their empirical project of explaining metaphor comprehension. Witness the equivocation in Carston's claims below:

Grice intended his account as a reconstruction in wholly rational analytical terms of whatever subpersonal processes actually go on in comprehension. (Carston, 2012, p. 474)

Compare the above quote with the subsequent text:

However, in the early days of experimental investigation of the online processing of non-literal language, Grice's work was the dominant pragmatic account, so experimental psychologists took it as the starting point for constructing a processing model. As such, it predicts that the interpretation of a metaphorical utterance (or, indeed, the interpretation of any of the other tropes) is a three step process: (a) the hearer, expecting literal truthfulness (as required by the maxim of truthfulness), tries the literal interpretation first; (b) then rejects it on the basis of its blatant falsehood (or blatant uninformativeness or irrelevance); and (c) then proceeds to infer the intended nonliteral interpretation […] The prediction, then, is that a metaphorical use of language should take longer to process and understand than a comparable literal use. This hypothesis has been extensively tested and has repeatedly been found to be false. (Carston, 2012, p. 474–475—italics mine)

One methodological paradigm used to measure online processing costs is the self-paced reading task. In general, self-paced reading measures the speed (i.e., reaction time) by which a metaphor is read and processed. The outcome of the task is compared to structurally similar literal sentences. By taking the difference in reading time between metaphorical and literal sentences, researchers make predictions vis-à-vis the cognitive cost associated with sentence processing across the conditions (e.g., literal and metaphorical items). Results from previous research in this paradigm (Harris, 1976; Glucksberg et al., 1982; Pollio et al., 1984; Keysar, 1989; Biava, 1991; Mcelree and Nordlie, 1999) support the idea that metaphors take longer to process.21 This is taken as evidence that metaphor processing is more cognitively.

Further, Carston claims that:

construed as a comprehension model, Grice's account of metaphor fares badly and its not clear that its construal (merely) as a rational reconstruction stands up against evidence of this sort either. (Carston, 2012, p. 475—italics mine)

To this end, Cartson writes that implicatures must be calculable.22 She states that the inferential process requires

the implicature and what is said (the “explicature” in her terminology) to function independently in the hearer's mental life. This, she says, requires that what is implicated cannot entail what is said (Saul, 2002b, p. 360).

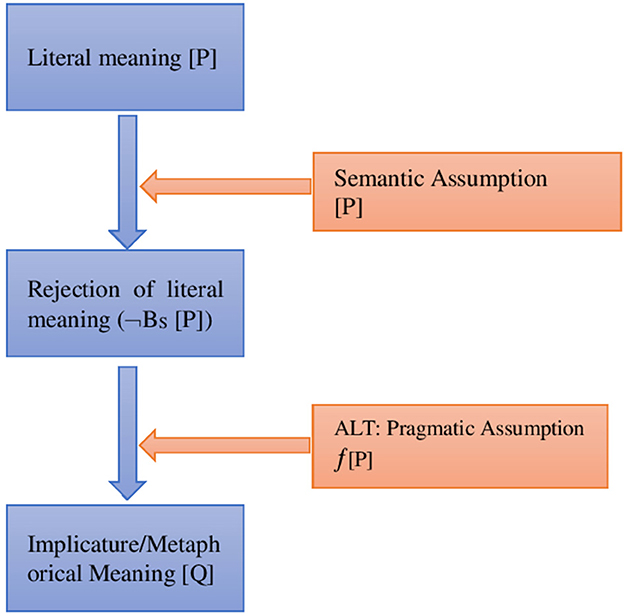

The idea that what is said and what is implicated must “function independently…” leads RTs to treat the comprehension process as being explicit to the listener, “calculated” in discrete, sequential stages (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Indirect access model: serial processing stages in the computation of meaning for utterances with potential metaphorical implicatures.

Here, the metaphorical meaning [Q] is a member of a set of possible pragmatic alternatives Q ∈ {Q, Q′, Q″, …} that are the outputs of pragmatic adjustment, f , of the conventional/literal meaning of the sentence [P] in the discourse context. I capture this in the following way: [Q] ∈ ALT[Q].

In Gricean terms, [P] represents the content of what is said/making as if to say,23 i.e., the content of the sentence assigned by the grammar together with the assignment of values to indexicals, resolution of ambiguity, and reference fixing. The semantic assumption provides the listener with a means to reject [P]. Here, (¬BS[P]) captures the listener's assumption that the speaker does not believe that [P]. The listener's semantic competence in a language, L, aids in their assumption that the speaker, S, did not mean to say that [P], but something else [Q]. The pragmatic assumption, among other things, is the assumption that the speaker is being cooperative and intends to communicate something beyond the meaning of the sentence [P].

The listener uses contextual information, background knowledge, and mutual beliefs about the discourse context and inferences about the speaker's intentions to provide themselves with a set of defeasible, alternative (ALT) meanings, where one or more of the alternative propositions [e.g., Q, Q', Q”, etc.] are part of the speaker's intended meaning [Q]. The point I wish to stress is that this model is claimed to follow from Grice's rational account.

Accordingly, the indirect model is cashed out as a serial processing model where the metaphorical meaning is generated by a clash with the literal meaning of the utterance in some discourse context, C, and what the listener believes about the speaker's beliefs, intentions, etc., (BS). Here is the process rendered in discrete computational stages:

Stage 1: Compute the conventional meaning of the utterance, [P].

Stage 2: Given the clash between semantic and contextual input, reject [P].

Stage 3: Calculate contextually appropriate meaning, [Q].

Here, the literal meaning, [P], acts as input in the determination of the figurative meaning, [Q]. Importantly, the meaning, [Q], conveyed by the speaker is constrained by the conventional meaning, [P]. If we put this picture together with Wilson's and Carston's comments above, we can identify six auxiliary hypotheses that constitute the indirect model:

(i) The comprehension procedure is a serial process;

(ii) The processor always begins from conventional word meaning and proceeds to the metaphorical meaning in discrete stages;

(iii) The utterance's literal meaning facilitates metaphor comprehension;

(iv) The process is explicitly available (i.e., available to consciousness);

(v) Metaphorical sentences take longer to process than their literal counterparts;

(vi) Metaphor processing exerts extra cognitive cost relative to literal control items.

We are told this picture “naturally follows” from Grice's comments from which we can derive empirical predictions. Although it is inviting to understand Grice in this way, we should not be led into temptation.

3.1. From competence to performance

Grice's model of interpretation belongs to a theory of competence; investigation into comprehension is performance based.24 The former specifies how listeners determine the content of an expression used metaphorically—whether the listener succeeds is another story.25 For Grice, interlocutors approximate ideal communicative exchanges. Claims about how listeners derive the speaker's intended meaning are claims approximating ideal rational audiences and are therefore not empirical. Theories of competence make no predictions about how our knowledge systems are used to answer questions about, for example, the length of time it takes to compute the inferences or whether such inferences are “cognitively costly” in comparison to some other class of linguistic stimuli.

Of course, there are numerous attempts to relate competence models to performance models. For example, Bresnan and Kaplan (1982) “Competence Hypothesis' spells out a means for doing so. Relating competence models to performance models requires the generation of auxiliary assumptions determining the performative aspects. My reading of much of the experimental literature on metaphor involving Grice's competence theory is that the model has been unreasonably extended to a theory of performance. The six auxiliary assumptions are precisely what are at issue.

I contrast the commitments of the indirect model above with those of the direct model below:

(I) Metaphor processing is direct26;

(II) Metaphor comprehension is automatic27;

(III) Metaphor comprehension does not exert extra cognitive costs relative to literal control items;

(IV) Metaphor processing is the same as literal language processing28.

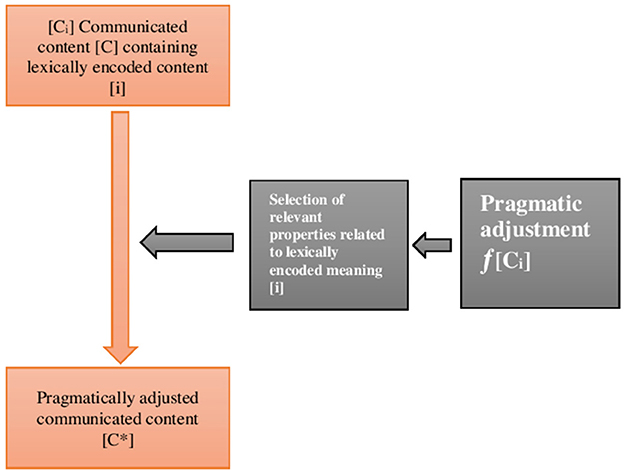

Figure 2 illustrates the direct access model:

Figure 2. Direct access model: processing stages in the computation of meaning for metaphorically intended utterances.

Here, the communicated content [C] includes lexically encoded concepts containing encoded information [i]. The function, f represents pragmatic adjustment. It includes a contextual parameter. The utterance of [Ci] results in a selection process of the relevant information contained in it that will be raised to contextual salience where f functions over the communicated content to adjust [Ci] yielding the communicated content [C*]. Unlike the Gricean model, there is no semantic assumption which yields the conventional meaning of the sentence. Rather, the processor pursues a path from the content expressed to generate a contextually strengthened meaning. Thus, the path from [Ci] to [C*] is direct (I). The application of the pragmatic function, f , is subpersonal, and therefore automatic (II). The model predicts that metaphorical uses of language do not exert extra costs relative to literal language (III). Finally, the comprehension process is universal (IV). That is to say, the process(es) that yield(s) meaning for literally intended language is the same (or nearly similar) for metaphor processing. Together (I) and (II) specify the temporal equivalence claim, and (III) and (IV) specify the cognitive equivalence claim.

4. Avoiding the strawman

In this section, I develop a streamlined performance model that is not as computationally “hopeless” or “psychologically implausible” as suggested by direct access theorists. A rational explanation asks “What makes a certain metaphorical meaning ϕ derivable?”, whereas a psychological explanation asks “What do listeners do to derive the metaphorical meaning ϕ?” (see Yavuz, 2018, p. 20). Grice is often misrepresented as pursuing the latter question. Consequently, one pervasive mischaracterization conflates the logic of implicature calculation with the sequential and discrete stages of implicature processing:

It might seem, then, that grasping what someone implicates requires first determining what they are saying. However, this is not true and something that Grice was not committed to. It's a mistake to suppose that what is said must be determined first or to suppose that Grice supposed this. (Bach, 2006, p. 25)

There are numerous cases where it is clear-cut that an interlocutor determines the implicature well-before the speaker finishes what s/he said—Grice was completely aware of this. Often implicature calculation is made on the fly and does not require the discrete stages of serial processing (i.e., a series of discrete stages of calculation and rejection of the relevant input) to determine the speaker's meaning:

[I]f in response to an utterance of “No man is an island,” someone says “Some men are peninsulas, some men are volcanoes, and some men are tornadoes,” in order to figure out what the speaker means you do not have to figure out first that he does not mean that some men are peninsulas, some men are volcanoes, and some men are tornadoes. Similarly, if you're discussing a touchy subject with someone and they say, “Since it might rain tonight, I'd better bring in the laundry, clean out my parents' gutters, and find my umbrella,” you could probably figure out before they were finished saying all this that they were implicating that they did not want to discuss the touchy subject any further. (Bach, 2006, p. 26)

If pragmatic processes are not always open to conscious reflection, as Bach points out, then armchair criticisms about their complexity must be qualified. Furthermore, there is no good reason to suppose that unconscious processes are simple. Geurts and Rubio-Fernández ask us, somewhat rhetorically:

What could be easier than seeing a chair, for example? Anyone with normal or corrected-to-normal vision can do it; even young children do it with ease. Nevertheless, all textbooks agree that the mental processes underlying visual perception are bafflingly intricate, and the complexity of Gricean reasoning pales when compared to that of seeing a chair. If we are to gauge the complexity of mental processes, introspective evidence is as good as no evidence, and more misleading. (Geurts and Rubio-Fernández, 2015, p. 452).

The point I wish to draw attention to is that the Gricean framework describes constitutive “ingredients” for metaphor interpretation, the purpose of which is to

make explicit why the hearer is entitled to draw certain inferences from the speaker's utterances…These protracted trains of thought are hypothetical; they merely serve to unveil the pragmatic logic of a linguistic act. (Geurts and Rubio-Fernández, 2015, p. 449)

For Grice, the “pragmatic ingredients” for metaphor include the contribution from semantic (i.e., conventional meaning) and pragmatic knowledge systems (i.e., the conversational context, general background knowledge, and the listener's beliefs about the speaker's intentions, etc.) guided by patterns of communicative behavior. This does not include cognitive load nor processing speeds. In light of this discussion, I reject auxiliary hypotheses (i), (ii), (iv), and (v), and I significantly qualify (vi) in light of Grice's view of calculability: Grice wrote that “the presence of a conversational implicature must be capable of being worked out” and “even if it can in fact be intuitively grasped, unless the intuition is replaceable by an argument, the implicature will not count as an implicature”.

Grice's use of the emphatic adverb “even” together with the conditional “if” and the adverb “intuitively” suggests a contrast between CIs (and by extension, metaphors) grasped intuitively (i.e., unreflectively) and metaphors grasped intellectually (i.e., reflectively). In other words, sometimes sustained and thoughtful attention is needed to calculate an implicature, sometimes it is not. Intuiting the meaning of a metaphor implies a quick and frugal process indicative of the time course involved in processing the meaning of dead (e.g., “I'm burnt out”), prosaic and conventional metaphors (e.g., “My lawyer is a shark”). This process is contrasted with reflective reasoning, implying a protracted, discursive, and sustained comprehension process indictive of poetic and novel metaphors (e.g., “Life is but a walking shadow”). This difference in calculation is supported by Grice's distinction between generalized (GCI) and particularized conversational implicatures (PCI).29

The performance model I offer is committed to the following auxiliary hypotheses:

(X) Literal meaning aspects30 are processed and facilitate the comprehension procedure of the metaphorical meaning;

(Y) Metaphorical meaning may be grasped unreflectively (i.e., intuitively) or reflectively (i.e., intellectually);

(Z) The meaning of a metaphor must be in principle replaceable by an argument.

Although there is no explicit specification of a temporal claim, (Y) can be interpreted as a commitment to temporal flexibility between metaphor types mentioned above. Notice, however, that we are blocked from deriving a claim of either the homo- or heterogeneity between metaphoric and literal sentence processing times. Regarding the cognitive claim, (X) and (Y) together can be interpreted as committed to qualitative processing differences between metaphorical and literal sentences.

Commitment to (X) follows from two considerations noted above. The first follows from Grice's account of CIs in general. Grice is quite clear to inform us that the literal meaning plays an important role in what a speaker is likely conveying by their utterance. The second is that, as Bach (2006) reminds us, Grice recognized that an interlocutor is able determine the meaning of an implicature (and by extension, a metaphor) without having to fully determine what the speaker said. For Grice's rational model requires that the “conventional meaning must always be part of an explanation on how interlocutors interpret each other's utterances” (Yavuz, 2018, p. 51). Thus, it seems that conventional/literal meaning constitutes an important aspect of metaphor processing in general “even if it rarely emerges as its output” (Camp, 2016, p. 134). Determining exactly what aspects of literal meaning play a role and how requires further empirical investigation.

(Y) stems from the observation that some metaphors are intellectually stimulating/demanding, while others are easily grasped. Not surprisingly, however, it fails to specify factors that predict whether a given metaphor is grasped in one way or another.

(Z) follows from my reading of the calculability criterion. It stipulates that interlocutors ought to be willing to justify their understanding of the implicature, and they must be capable (to a certain degree) of providing justification(s) by replacing what is intuitively grasped by arguments that reflect the intended meaning (Camp, 2006a, 2008; Sbisà, 2006).31

Additionally, I want to point out that hypotheses (X)–(Z) may well include further sets of claims derived from Grice's account. Take (Y) for instance: The distinction between intuitive and intellectual engagement with metaphors is suggestive of certain further predictions for the comprehension of dead, conventional, poetic and novel metaphors. This spectrum is correlated with Grice's comments on GCIs and PCIs. Reimer (2013) has argued that PCI comprehension is correlated with second-order Theory of Mind (ToM)—roughly, the ability to attribute (true/false) mental states to the mentals states of others (e.g., Mary falsely believes that p). Reimer derives this prediction from Grice's more general comments on listeners engaged in reasoning about the mental states of their interlocutors to explain and predict their communicative behavior. Thus, we should expect that comprehension of metaphors involving PCIs (e.g., poetic metaphors) to require second-order ToM.32

In the next section, I attempt to determine whether my interpretation has any psychological validity. I do not include hypothesis (Z) in my overall pursuit for two reasons: First, it is partially a sociological issue pertaining to discourse participants giving and asking for reasons (i.e., practical demands for clarity and justification occurring “in the wild”). Second, it is partially a philosophical question that pertains to approximation and paraphrase, that is, whether metaphorically intended meaning can be cashed out by literal paraphrase, and whether paraphrase is exhaustive of metaphorical meaning.33

5. Recent experimental evidence on metaphor processing

Recall that the direct model found support for it's claim via self-paced reading paradigm. However, these studies were not by themselves sufficient to establish the temporal and cognitive claims. Questions regarding the role of literal word meaning, cognitive cost, and processing speeds can be measured by more fine-grained methodologies. Additionally, I invite the reader to think about “cognitive effort” as the volume and the kind of cognitive resources exploited in the retrieval of meaning—and not simply processing speed. For “finding that two cognitive tasks have similar reaction times does not necessarily imply that they are served by common brain pathways” (Stringaris et al., 2007).34

In this section I survey empirical literature on metaphor processing that I have mentioned elsewhere (Genovesi, 2020). I include a discussion of two meta-analyses involving fMRI conducted by Vartanian (2012) and Rapp et al. (2012). Both studies use an activation likelihood estimation (ALE) method to discern dissociable neural pathways involved in metaphor comprehension in comparison to literal language processing. I provide recent data from research using pupillometry, and developmental research on metaphor performance.35

5.1. Psycho- and neurolinguistic research

Psycholinguistics has identified numerous factors that contribute to the automaticity of metaphor comprehension. These include conventionality, familiarity, aptness, animacy, and the larger communicative context—i.e., whether a context biases a metaphorical reading (Cacciari and Glucksberg, 1994). Novel metaphors have been observed to take longer to process than both literal and conventional metaphorical control items (Blasko and Connine, 1993). In addition, Bowdle and Gentner (2005) observed that novel similes are processed significantly faster than novel metaphors. This research suggests that it is not the unfamiliar juxtaposition of terms but rather the explicitness of literality that exerts an effect on processing time. Among unfamiliar metaphors, highly apt meanings are interpreted quickly, although not as quickly as literal meanings while less apt metaphors take significantly longer to process.

In neurolinguistics, electroencephalography (EEG) and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) are used to trace the early processing strategies of comprehension at the cognitive and neural level. Notable event-related potential (ERP) studies conducted in various languages offer compelling evidence of processing costs associated with metaphors relative to literal control sentences: In English: Coulson and Van Petten (2002), Lai et al. (2009), and De Grauwe et al. (2010); in French Pynte et al. (1996); in Hebrew, Arzouan et al. (2007); in Italian Resta (2012); in German, Weiland et al. (2014). The studies reported an enhanced N400.

The N400 is a negative-going waveform representing an event related potential (ERP) linked to meaning comprehension. It has been identified as a stable component in metaphor research, typically thought to be associated with a search in semantic space triggered by the processor identifying an aberrance in comprehension. The presence of an N400 is thus taken to reflect extra processing effort.36

Pynte et al. (1996) and Lai et al. (2009) manipulated the familiarity of the metaphors and the surrounding context. Results indicated a pronounced N400 for all metaphors. Amplitudinal variations were understood as a function of the examined factors (e.g., unsupportive context increased N400 amplitude). Importantly, Pynte et al. (1996) notes that

Metaphors do not form a homogeneous category. There is a continuum from “lexical” metaphors, whose meanings are probably stored in the mental lexicon (e.g., “X is a pig”), to completely new ones.37 The consequence is that no general account of metaphor comprehension can be proposed. Some metaphors seem to be “directly” understood, even when presented in isolation, while others cannot be understood without the help of a least some contextual support.38 (Pynte et al., 1996, p. 312)

Although it would be more than a stretch to claim that Grice's account was equipped to deal with this observation, his distinction between intuitive and reflective understanding is at the very least amenable to it in a way that the indirect model is not.

To address the role of literal meaning in conventional metaphor comprehension, Weiland et al. (2014) employed ERP in combination with a masked priming paradigm to investigate the direct and indirect models. The indirect model predicts that literal meaning is activated in the early stages of processing. The direct model predicts that the processor only has to access the literal or metaphorical meaning.39 The masked priming paradigm taps into “automatic and strategy-free lexical processing” (Forster, 1998, p. 203).40 To this end, they compared literal and metaphorical sentences with and without masked priming. Specifically, they tested whether a probe (e.g., “furry”) word associated with the literal meaning of the target word (e.g., “hyenas”) facilitates or hinders comprehension across conditions (e.g., literal condition: “The carnivores are hyenas…”; metaphorical condition: “the children are hyenas”). They reasoned that facilitation should be reflected in reduced N400 amplitudes. The authors claimed that the indirect model predicts that the literal prime should have no negative (and even a facilitating) effect on the computation in both literal and metaphorical conditions. In conditions without priming, the results showed an enhanced N400 in comparison to literal control sentences. Conditions with masked priming resulted in reduced N400. The researchers claimed this reduction was due to the fact that the semantically related prime, which preceded the onset of the target word, facilitated (eased) the processing of the target during the lexical access phase. By contrast, unrelated prime words elicited a hampering effect reflected in a pronounced N400.41

Several fMRI studies observed differences in brain-regional recruitment between metaphors and literal controls. For example, Mashal et al. (2007), Stringaris et al. (2007), and Ahrens et al. (2007) observed lateral differences in hemispheric activation and regional differences between metaphors and literal sentences. A previous study by Mashal et al. (2005) observed significant involvement of the right hemisphere—particularly in the posterior superior temporal sulcus (PSTS) in processing non-salient (low-apt) meanings of novel metaphors. The PSTS is associated with creative tasks such as verbal problem solving, verbal creativity, and multisensory processing (Jung-Beeman et al., 2004).

Stringaris et al. (2007)42 observed that metaphoric sentences recruit the left inferior frontal gyrus (LIFG) and the left thalamus. The LIFG is a key brain region for the comprehension of non-literal stimuli whose functional role includes several cognitive operations, such as word cohesion and integration into meaningful sentences (Bookheimer, 2002; Badre and Wagner, 2007; Menenti et al., 2009). Another function is meaning regulation among multiple competing responses during sentence comprehension (Gabrieli et al., 1998; Petrides, 2005; Sakai, 2005; Turken and Dronkers, 2011). For example, the interactions between BA 47 and left middle temporal gyrus select candidate meanings, keeping them in short-term memory throughout sentence processing and integration into the context (Turken and Dronkers, 2011). The LIFG is associated with Brodmann's area 44, 45 (together, Broca's area), and 47—commonly referred to as our language processing network. Crucially, the same activation patterns were not observed in literal control sentences.

Ahrens et al. (2007) observed differences between conventional metaphors, anomalous metaphors, and literal controls. Anomalous metaphors differed from literal controls by increased bilateral activation of the frontal temporal gyri. Conventional metaphors differed by a slight amount of increased activation in the right inferior frontal temporal gyrus (RIFG). Although the linguistic role of the RIFG is controversial, it's coactivation with the LIFG have been observed (Bulut, 2022). Some of its noted functions include metaphorical language processing (Gainotti, 2016), and processing of contextual and coherent meaning (Vigneau et al., 2011).

Activation of the RH in verbal creativity tasks is interpreted as consolidating distant and multimodal semantic relationships in metaphorical comparisons according to studies conducted on subjects with left (LHD) and right hemisphere damage (RHD) (Rinaldi et al., 2004). In two studies, subjects listened to sentences containing metaphoric expressions. Subjects were presented with four pictures that were related either to the metaphoric or literal meaning of the sentences, or to a single word in the sentences. In a visuo-verbal task, patients were asked to point to the picture that they felt represented the meaning of the sentence. RHD patients preferred pictures related to literal meaning but were able to explain verbally the metaphoric meaning of the sentences, suggesting that without the aid of the RH, and the PSTS in particular, preference for metaphorical interpretation can be overridden for LH preference of the literal interpretation.

Vartanian (2012) conducted a meta-analysis on the extant literature of metaphor processing in neuroimaging studies—specifically fMRI. Results show the activation of the rostro-lateral prefrontal cortex (RLPC), as well as several other structures that fall within the brain's fronto-parietal system. In particular, it reveals three significant clusters of activation: the dorso-lateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), temporal pole, and cingulate gyrus. These clusters correspond to Brodmann's area: 9/46; 38; 24/32. Activation of the prefrontal cortex (PFC) extending across the dorsal and ventral (inferior) regions was reported in a number of studies (see Vartanian, 2012, p. 310). Other relevant activations included the left cingulate gyrus, the adjacent medial frontal gyrus, and the anterior cingulate cortex. The cingulate gyrus is known to be an important part of the brain's frontal attentional control systems (Carter et al., 1997). Furthermore, activations in the left temporal pole have a well-established role in text comprehension. The DLPFC plays a key role in the brain's working memory (WM) system. Taken together, these observed activations indicate that metaphors exert greater demands on WM and text comprehension resources by recruiting brain regions not observed to be as active in the literal control tasks.

A study by Yang and Shu (2016) looked at literal and fictive motion sentences. The authors found that sentences about fictive motion (e.g., “the highway runs through the house”) elicit strong activity in the right parahippocampal gyrus. The same area is elicited in literal motion sentences (e.g., the man goes through the house). The parahippocampal gyrus is a gray matter cortical region that surrounds the hippocampus. Previous studies have found this region to be crucially involved in encoding and recognizing spatial information. These findings suggest that the mechanisms through which we grasp our literal, embodied, real-world motion utterances facilitate the computation of more abstract and figurative ones.

Results from a divided visual field study conducted by Forgács et al. (2014) suggested that conventional metaphors are processed more quickly than novel metaphors. One plausible explanation is that speakers do not require explicit and prolonged reflection when interpreting conventional metaphors. On the other hand, novel metaphors require more processing because, as the authors of the study suggested, processing delays are likely attributable to the complexity and abstractness of the intended figurative meaning.

A meta-study conducted by Rapp et al. (2012) examined 38 fMRI studies on non-literal language, 24 of which examined metaphors. The most important results for metaphors were obtained in the following analyses; Meta-analysis 2: non-salient metaphoric stimuli vs. literal sentences: The activation clusters were predominantly in the LH, with strongest activation in the left thalamus. Meta-analysis 3: non-salient or novel metaphoric stimuli vs. literal sentences: The most pronounced activation cluster was found in the left middle/IFG. There was moderate bilateral activation. Meta-analysis 5: metaphor: The strongest activation cluster was found in the left parahippocampal gyrus, the next most pronounced was in the left IFG (Brodmann area 47/45). The main observation from all 38 studies was the predominance of a left lateralized network: Specifically, the left and right IFG, the left middle/superior temporal gyrus, and some contributions from the medial prefrontal, superior frontal, cerebellar, parahippocampal, precentral and inferior parietal regions (Rapp et al., 2012, p. 605).43 The major activation differences between metaphorical and literal language is reflected in the left cerebral hemisphere (LIFG). The analysis did not find overwhelming evidence in favor of RH laterality. Rather, the level of activation was interpreted as “moderate”44 with less than one-third of studies analyzed reporting little or no activation.

5.2. Research from pupillometry

The first study to use pupillometry to investigate conventional metaphorical processing was conducted by Mon et al. (2021). Pupil dilation can provide a finer temporal granularity compared to responses measured by fMRI analysis. Additionally, it captures long-lasting physiological arousal and cognitive engagement unlike short-lived responses in analysis of ERP components. Pupil dilation is a reliable indicator of the firing of neurons in the locus coeruleus (LC). The LC is anatomically and functionally connected to the amygdala. Activation of the amygdala is associated with heightened emotional arousal or focused attention to relevant and salient stimuli (Garavan et al., 2001; Hamann and Mao, 2002; Seeley et al., 2007; Costafreda et al., 2008; Cunningham and Brosch, 2012). Furthermore, previous fMRI research (e.g., Citron and Goldberg, 2014; Citron et al., 2016, 2020) has demonstrated that it is a key brain region implicated in metaphor comprehension. Mons et al. sought to determine whether conventional metaphors are more engaging45 than literal paraphrases and concrete descriptions (the latter two serving as control items) on the basis of increased neural activity reflected in pupil dilation. To address this, the investigators exploited stimulus-evoked pupil dilation as an “implicit and time-sensitive index of focused attention or task engagement” (Mon et al., 2021, p. 11).

The results of the study showed increased pupil dilation when listeners comprehended sentences containing conventional metaphors in comparison to literal paraphrases (which conveyed a similar meaning) or concrete descriptions (which shared similar words). Moreover, results indicated that greater dilation seemed to be caused by greater degree of metaphoricity (with relevant variables such as familiarity, plausibility, valence, intensity, and complexity taken into account). Nevertheless, heightened pupil dilation in response to conventional metaphors was found regardless of whether metaphoricity was treated as a categorical (i.e., as a condition) or continuous variable, and regardless of whether pupil dilation was considered at the onset of the target phrase, or from after it until 2 s beyond the target phrase.

Dilation responses to literal paraphrases and concrete sentences were indistinguishable, despite including different words and conveying different meanings. The same study also used a set of surveys to determine whether participants perceived metaphorical sentences as more emotionally or cognitive engaging than control items, and which among the three items conveyed a “richer meaning”. It was determined that the rich meaning conveyed even by conventional metaphors occurs as soon as the target is recognized and integrated into the larger context of the sentence. The researchers point out that choosing the metaphorical sentence over literal paraphrases was correlated with the gradient degree of metaphoricity. The studies were unable to determine whether heightened engagement with metaphorical descriptions was due to increased cognitive or emotional processing. Nevertheless, the results support the idea that metaphors are psychologically engaging in comparison to literal control items and concrete descriptions.

5.3. Developmental research

If metaphor processing is qualitatively different than literal language processing, we could reasonably expect them to have different developmental trajectories. There is a great deal of developmental research that supports the idea that metaphor performance has a distinct developmental trajectory that increases with age as a consequence of the maturation of distinct brain processes (Rapp et al., 2012, p. 608). Metaphor comprehension has been observed as developing late in comparison with literal language performance, with some studies indicating that the process continues past early adolescence. One factor assumed with decreased metaphor performance in younger children is underdeveloped brain processes. One study, comparing three groups of participants-−11-year-olds, 15-year-olds and young adults (~21 years of age)—demonstrated that the ability to process and interpret metaphors is a task that demands contributions from relational verbal reasoning (i.e., analogical and class-inclusion reasoning) and executive functioning abilities including inhibitory processes, attentionally controlled resources, and WM (Carriedo et al., 2016). The study predicted that the ability to interpret metaphors relies on relational reasoning abilities and is supplemented by executive functioning abilities. If relational reasoning was the only factor at play in interpretation, then one should not expect to see developmental differences since most children acquire these abilities at age 11, while executive functioning processes have not yet fully matured.

Results showed that metaphor interpretation improves across development. Specifically, although the ability to understand metaphors is present by age 11, there is clear progress from 11 to 15, and from 15 to young adulthood—especially when “metaphors are unfamiliar and are difficult to understand due to the absence of a context” (Carriedo et al., 2016, p. 15). At the age of 15, it was determined that different measures of executive functioning, including updating and suppression of information in WM, resistance to proactive interference, conjointly with relational verbal reasoning, made significant contributions to metaphor interpretation.

Analysis by age shows that updating information in WM and cognitive inhibition develop until late adolescence (with some processes related to inhibition developing beyond that developmental stage). At age 11, children cannot benefit from WM processes to understand metaphors. At age 15, executive functioning is considerably consolidated, adolescents benefit from general WM processes. Interestingly, in young adults, executive processes failed to have a significant explanatory effect on interpretation unless the task demanded interpretation of a novel metaphor in the absence of context. The researchers speculate that this is due to young adults exploiting more developed semantic knowledge and having higher reading experiences.

Willinger et al. (2019) compared groups of 7, 9, and 11-year-olds. They found that metaphor identification—which the authors interpreted as the ability to detect metaphoric contents by successful differentiation between metaphor-relevant and non-relevant stimuli—and metaphor comprehension—defined as the ability to comprehend and verbally explain metaphors—increased with age. The study supports the idea of ongoing development with to respect to metaphor performance. Ultimately, metaphor interpretation is a cognitive ability that requires consolidation of a host of cognitive (verbal reasoning strategies, executive functioning) and social (semantic and world knowledge, reading experience) factors over time.

5.4. Discussion

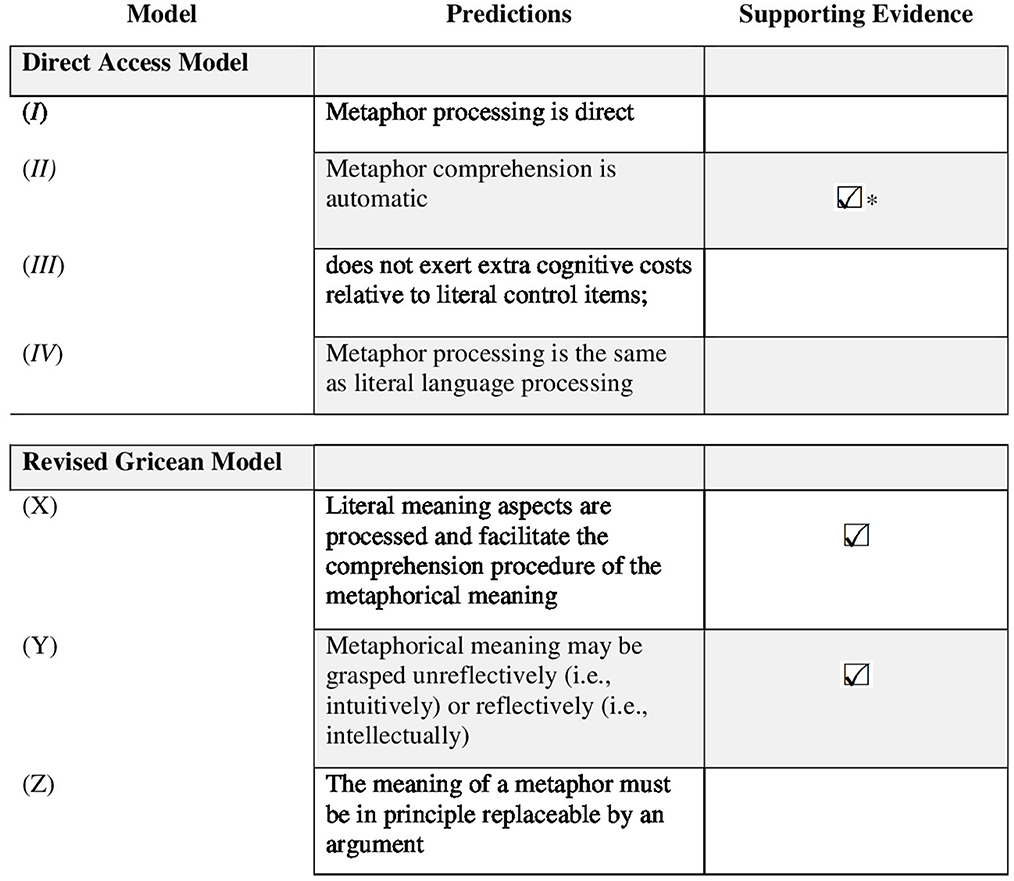

The above allows us to draw the following conclusions: First, literal meaning aspects play a crucial role in metaphor comprehension. Second, metaphor processing is a cognitive tasks that requires greater cognitive flexibility than literal language processing. The results cited above significantly qualify hypothesis (II). I represent this with the asterisk (*) in Figure 3 below. Whether a metaphor is interpreted automatically or not depends on a host of related factors. For example, dead and conventionalized metaphors—as well as novel metaphors backed with enough supporting context—may in fact be comprehended at a subpersonal level. Nevertheless, literal meanings aspects are always computed. Results from (I), (III), and (IV) are contradicted. (see Figure 3 below).

Figure 3. Predictions of the direct model and revised Gricean model of metaphor processing and supporting evidence.

The Gricean model I have teased out from Grice's rational account of metaphor finds support for the facilitating role played by the literal meaning in the construction of metaphorical meaning. However, nothing I have cited indicates that the procedure is borne out in discrete, serial stages. Grice was unconcerned about this and his rational model makes no claims about it. I return to this point below.

6. A programmatic sketch

The previous discussion may have provided sufficient evidence to vindicate Grice's theory of metaphor from the strawman, but it is not without its deficits. There are several outstanding issues regarding metaphor that Grice's account does not anticipate, is silent on, or simply gets wrong. For one, on the theoretical side of things, an adequate theory of metaphor must specify the distinctive principles of metaphor interpretation. Namely, it must identify the mutually shared patterns of thought on which metaphor rests, and on which the speaker intends her audience to engage to infer the metaphorically intended meaning. Grice has not provided a satisfactory response to this issue.

Grice treats metaphor as a species of implicature. As such, he tells us that it must be capable of being “worked out' by the listener. Grice claimed that a metaphor is worked out in the following way: “The most likely supposition is that the speaker is attributing to his audience some feature or features in respect of which the audience resembles” (Grice, 1975, p. 53). Admittedly, this is not extremely helpful. As I mentioned in Section 2, a number of theorists (e.g., Carston, 2002b; Wearing, 2006; Wilson and Carston, 2007; Sperber and Wilson, 2008) have demonstrated convincingly that metaphors are more intimately connected with conventional word meaning and behave differently in conversation than paradigmatic CIs.

Although Grice acknowledged that metaphors have cognitive content, he failed to acknowledge their non-cognitive import, i.e., poetic, imagistic, and affectively-laden qualities (Davidson, 1978; Camp, 2008). On the empirical side of things, echoing Davidson, Camp writes “rich, poetic metaphors, are important and powerful communicative tools precisely because they can induce in their hearers' new ways of thinking and feeling about the subject under discussion” (2003, p. 39). This is attested to by neurolinguistic evidence (Section 5) that demonstrates the activation of neuro-anatomical regions associated not simply with contextual knowledge, but imagining, simulated embodiment, and affective states.

Grice's account of metaphor was followed by extensive work on the indirect access model. The empirical questions to which Grice's rational model was said to address include, “does the system compute in serial or in parallel?”, “What information does the system have access to at each stage in the computation procedure?”, and “What constitutes a stage in the procedure?” (Chemla and Singh, 2014a). The model answers these questions by claiming that metaphor comprehension is a discrete, serial procedure with metaphorical meaning arising post-compositionally. If my arguments in the last few sections have been persuasive, then there is reason enough to suppose that this view does not belong to Grice—nor should we suppose that he would have endorsed it. Specifying how the computational mechanism(s) are instantiated and take place in the minds of speakers requires significant departure from Grice's project.

6.1. Alternatives

In this section, I offer, some alternatives to the indirect access model. On the surface, these alternatives are compatible with the hypotheses of the Gricean model I outlined in Section 4.46 One alternative: top-down pragmatic and bottom up syntactico-semantic comprehension procedures occur in parallel and are cognitively penetrable. Some evidence in support of this hypothesis can be found in Egorova et al. (2013). The team investigated the neural processing of two types of speech acts: Naming and Requesting. Results showed surprisingly early access to pragmatic and social knowledge (~120 ms) after the onset of the critical word. The researchers claim that this is nearly the same time as, or even before, the earliest brain manifestations of semantic word properties could be detected. The team concluded that pragmatic reasoning occurs “in parallel with other types of linguistic processing, and thus supports the near-simultaneous access to different subtypes of psycholinguistic information” (Egorova et al., 2013, p. 1—italics mine). This hypothesis rules out the possibility of the autonomy of the language to compose syntactic structure and semantic meaning on its own.

Another alternative includes parallel processing but specifies an early lexical processing procedure that is informationally encapsulated. This allows for a “best of both worlds” solution. For example, suppose that much of what we read and hear is influenced by contextual factors from previous discourse moves, including more global expectations and experiences where

pragmatic influence can come from the existence of “conversation scripts” and stereotypical exchanges, as where an utterance of “Just these” is heard as expressing that these are the only items I wish to purchase now when uttered at a cash register in a shop. (Borg, 2016, p. 514)

Support for this alternative can be found in the scalar implicature community, but also from folks with interests in presupposition and polarity items. Some of the relevant contributions include Schlenker (2008), Huang and Snedeker (2009), Chierchia et al. (2012), Chemla and Bott (2013), Chemla and Singh (2014a,b); van Tiel and Schaeken (2017), and Domaneschi and Di Paola (2018). Accordingly, we can, in principle, specify the contribution made by the language parser and pragmatic system independently of one another. This alternative forces us to reconsider how we understand seriality, opening up the possibility for viewing top-down pragmatic processes and bottom-up syntactico-semantic processes as working cooperatively, despite being structurally distinct in relevant ways.

A third alternative may be that one processing method is selected over the other based on the level of metaphoricity, familiarity, etc., the supporting context, and the speaker's deliberate intentions to “use a metaphor as a metaphor” (Steen, 2015).

A weak version of the Gricean model I sketched would find empirical support for hypotheses (X) and (Y). Together, they predict that metaphorical uses of language are not processed equivalently to literal uses of language. Thus, the model rejects the cognitive equivalence claim held by direct access theorists. The Gricean model finds support from the studies surveyed in Section 5. A stronger version of the model would corroborate all three hypotheses, (X), (Y), (Z). Yet, even if empirical data corroborates one or all the auxiliary hypotheses, a comprehensive and psychologically robust model of metaphor processing would still be far off. For example, empirical specification would still be needed to determine exactly which mechanisms are involved and how they interact over the time-course of metaphor processing from utterance uptake to (and in the most successful cases) appraisal and appreciation of the utterance. Additionally, a comprehensive model should specify whether and how the mechanisms involved in generating metaphorical inferences differ from other tropes. Furthermore, a comprehensive model of metaphor processing would need to mesh empirically and philosophically with our broader understanding of language, thought, and communication.

7. Discussion

In this article, I have given an account of Grice's rational model of metaphor interpretation. According to a multisource trend in metaphorology, that account was treated as making certain empirical claims. I drew out six auxiliary hypotheses. I claimed that these hypotheses made a strawman of Grice's account. In defense of Grice, I argued that the goal of Gricean pragmatics is to offer rational explanations of utterance interpretation and explicate the pragmatic logic behind our inferential patterns of thought. I used these observations to sketch a more charitable and streamlined empirical picture of Grice's rational model with three auxiliary assumptions (that can be further specified). I have shown that my Gricean alternative is broadly consistent with recent scientific data on metaphor processing. I offered this model as a contender to the direct and indirect model.

Nevertheless, there are plenty of fundamental questions raised by this picture—more than it is possible to address in this article, and which inspire further empirical specification. Some of these questions include, “what are the distinctive, mutually shared patterns and processes of thought on which metaphorical comprehension relies?” “Does metaphor comprehension differ from the comprehension of other tropes?” “What aspects of lexical meaning are accessed and when?” “Does processing of linguistic and contextual meaning happen in parallel?” The fact that there are open questions does not mean that Grice is no help at all. Far from it: The Gricean model of metaphor processing I sketch represents a viable research paradigm in metaphorology by (i) outlining candidate empirical hypotheses which can be specified by further sets of assumptions, and (ii) establishing a relation between the rational intentional level of our knowledge system and the online processing of our performance system.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Funding

Research for this article was funded by a post-doctoral fellowship from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC) 435-2016-1574 and by grants from the National Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) RGPIN/05044-2014.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Josu Acosta, Paul Chellew, Eros Corazza, Roberto G. de Almeida, María de Ponte, Patrick Duffley, Beñat Esnaola, Yolanda García, Ekain Garmendia, Christoph Hesse, Jacob Hesse, Rob Hunter, Kepa Korta, El Mustapha Lemghari, David Mandel, Genoveva Martí, Nathan Matthews, Bingzhuan Peng, John Perry, Laura Pissani, Michael Pleyer, Andrea Raimondi, Michael Shaffer, Ella Wehrmeyer, and three reviewers for their helpful and constructive feedback on earlier drafts of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^It is not entirely clear from where the psychologized version of Grice's account of metaphor arises. The earliest accounts attributing psychologized claims to Grice's theory of conversation (in some relevant sense) seem to be contextualist criticisms of the borderline Grice drew between what is said and what is implicated. See Saul (2002b) for discussion.

2. ^In the empirical literature, Grice's model is referred to as the “indirect access model” the “three-stage model”, and “classic pragmatic model”. In this article, I use the terms “Gricean model” and “indirect (access) model”. The former refers to any empirical (i.e., performance) model attributed to Grice's account of metaphor interpretation. By the latter, I refer to the specific model attributed to Grice by his critics. To avoid confusion, I do not use the terms “three-stage model”, “standard model”, nor “classic pragmatic model”.

3. ^See Dänzer (2021) for a defense of Grice's rational program as a psychologically plausible research paradigm. The author provides detailed account of the explanatory project of Gricean pragmatics. He argues for a nuanced view of Gricean pragmatics that seeks psychological explanations of utterance interpretation that are cognitively real in a “clear and robust sense”.

4. ^Notable attempts have been made to bring together psychologically oriented pragmatic models, such as Relevance Theory, with models in Cognitive Linguistics (see, especially Gibbs and Tendahl, 2006; Tendahl and Gibbs, 2008; Tendahl, 2009; Wilson, 2011).

5. ^See Carston (2010), Rubio-Fernández et al. (2015, 2016) for a revised version of the direct access model that departs and qualifies some of the core tenants of the earlier model. Carston (2010), for example, has proposed a dual-route processing model. One route is rapid, local, on-line concept construction. The other is more global and reflective, where literal meaning “lingers” throughout the comprehension process. Carston observes that the literal meaning plays an essential role in the processing of poetic and novel metaphors. I believe the view of the Gricean model I develop is compatible in many ways with Carston's proposal. The alternative Gricean model I sketch makes a stronger claim than Carston's in that it predicts that aspects of the literal meaning are always involved in the comprehension procedure.

6. ^Similarly, Relevance Theorists have argued that the notions of literal meaning and literal use are not useful in a theory of communication (Allot and Textor, 2022, pp. 4). Rather, they endorse a view of lexical pragmatics that views figurative uses of language, including hyperbole and metaphor as no different in kind than literal and loose uses of language, such that “there is no mechanism specific to metaphors, and no interesting generalization that applies only to them” (Sperber and Wilson, 2008, p. 97). Proponents of Conceptual Metaphor Theory (CMT) claim that “much of our ordinary conceptual system and the bulk of our everyday conventional language are structured and understood primarily in metaphorical terms” (Lakoff and Johnson, 1980, p. 453—italics mine).

7. ^Interestingly, after discussing both irony and metaphor, Grice observes that it is possible to combine the two: “I say You are the cream in my coffee, intending the hearer to reach first the metaphor interpretant ‘You are my pride and joy' and then the irony interpretant “You are my bane”” (Grice, 1975, p. 53). For further discussions on the priority of the metaphor “interpretant”, and ironic metaphor compounds, see Popa-Wyatt (2017a,b) and Stern (2000).

8. ^Some misunderstandings with Grice's account of metaphor originate from different understandings of the phenomenon under discussion. Grice, for example, understands metaphor as a trope. Alternatively, Cognitive Linguists, following Lakoff and Johnson (1980) highly influential Conceptual Metaphor Theory, understand metaphor to mean a conceptual “cross domain mapping” and largely focus on conventional and dead linguistic metaphors as evidence of their conceptual underpinnings. Furthermore, it could be argued that what Grice had in mind by metaphor is similar to what Ricoeur (1987) refers to as “la métaphore vive”, or to what Steen (1992, 2000, 2008, 2015) refers to as a “deliberate” use of metaphor, or White's (1996) conception of poetic metaphors. The guiding idea is that the audience is explicitly aware that some bit of language is being used metaphorically. This fact nearly guarantees that the audience will process it in a way that is similar to the indirect model.

9. ^See Genovesi (2023) for a Gricean-inspired response to this issue.

10. ^Some authors (e.g., Searle, 1993; Camp, 2003; Genovesi, 2023) regard the generality as a virtue of the theory because it “demonstrates that we are appealing to principles of interpretation we already need for other purposes” (Camp, 2003, p. 36).

11. ^A more general, and perhaps accurate, restatement of the picture is that a speaker conveys something (that she does not always, strictly speaking, say) by “putting it that way”. However, I shall not pursue this line of thought here. I am concerned with metaphor comprehension, not with what speakers do in uttering them.

12. ^A twice true metaphor is one that is true on a literal and metaphorical reading.

13. ^A negative metaphor is a metaphorical utterance under the scope of the negation operator.

14. ^I do not provide a classification of metaphors in this article. However, see Tirrell (1991), Miller (1993), White (1996), and Camp (2006c) for some suggestions.

15. ^Despite their departure from the standard [a is [an] F] structure, it is not obvious that a Gricean account would fail to meet the particular challenges posed by these examples. Grice, and Gricean-inspired accounts, can appeal to the cognitive effects associated with metaphor as the mechanism by which the listener interprets the metaphorically intended meaning (Camp, 2006c, p. 161).

16. ^I owe this example and explanation to Yavuz (2018, p. 35). Although, the author does note refer to the issue as the “unidirectionality problem”.

17. ^For although “the processes that the hearer uses to interpret an utterance might indeed provide evidence about an utterance's meaning-property… they do not constitute it” (Devitt, 2021, p. 124).

18. ^See Stern (2006) for an excellent review of and response to the debate.

19. ^There is of course wide disagreement about the precise nature of the inferences involved and about the division of labor between conventional meaning and rational inference.

20. ^Relevance Theory has gained significant traction in contemporary pragmatic research. They provide a highly plausible, comprehensive, psychologically oriented pragmatics programme. Their praises and criticisms of Gricean pragmatics are widespread and impactful.

21. ^See Holyoak and Stamenković (2018) for a review of the relevant psycholinguistic research. For a critical review of studies comparing processing times between metaphorical and literal sentences, see Hoffman and Kemper (1987).