94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Commun., 13 July 2023

Sec. Language Communication

Volume 8 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2023.1159026

This article is part of the Research TopicCulture and Second Language (L2) Learning in Migrants, Volume IIView all 7 articles

Refugees and immigrants differ in their reasons for migration and their criteria for entry into Canada. While economic immigrants migrate to other countries voluntarily, refugees are forced to leave their countries due to fear of death or persecution. Due to the difference in the nature of resettlement, assumptions exist that immigrants and refugees may differ in terms of emotional well-being, social adjustment and acculturation, and second language learning outcomes. To assess these assumptions, this study was conducted on a sample (N = 45) of newcomer Iranian immigrants (Mage = 19.24, SD = 2.06) and refugees (Mage = 23.15, SD = 4.02). The participants completed a series of questionnaires regarding their English language and literacy skills, acculturation, socioeconomic status, emotional well-being, and potential traumatic experiences in the past. This study examined the relationships among these variables for the two groups. The refugees scored lower on variables related to socioeconomic status and had lower English skills than the immigrant group. English word reading and vocabulary were related to second language reading comprehension for immigrants, but only word reading was related to reading comprehension for refugees. The experienced trauma was significantly higher among the refugees. However, the trauma was not a significant predictor for any of the English proficiency skills. Acculturation was related to English reading comprehension, and enculturation was negatively associated with English vocabulary and reading comprehension for refugees but not for immigrants. The findings point to similarities and differences between refugees and immigrants. Recommendations to facilitate resettlement are discussed.

The acquisition of oral language and literacy skills in the dominant societal language are crucial for future achievement and integration of newcomers. Canada has historically been considered an immigration country and welcomes on average 235,000 newcomers a year (Statistics Canada, 2016). The number of people escaping violence worldwide is the highest since World War II (United Nations High Commission on Refugees: UNHCR, 2021a). A large body of research exists regarding the acquisition of second language (L2) oral proficiency and literacy in immigrants (Bigelow and Tarone, 2004; Kurvers, 2015), and some research exists regarding the links between language skills and acculturation in immigrants (Jia et al., 2014). However, little research examines these constructs in refugees with the focus on acculturation and wellbeing (Phillimore, 2011; Hormozi et al., 2018). To our knowledge, no research compares immigrants and refugees on language, literacy and acculturation (Maehler et al., 2021). The implicit assumption is that refugees have lower language proficiency and skills than other economic immigrants (Canada) (see below for a description of the Canadian immigration system). With the rise in the number of refugees, it is important to understand issues related to migration, L2 acquisition and acculturation in refugees. The present study examined similarities and differences between immigrant and refugee newcomers on L2 vocabulary and literacy as well as acculturation. The participants were newcomers from Iran to Canada and shared the same culture and first language (L1), Farsi.

According to the United Nation's criteria for seeking refugee status, claimants must demonstrate a well-founded fear of persecution due to their religion, race, nationality, membership in a particular social or political group, or displacement due to war. As of 2023, Iran is ranked fourth among Canada's top 10 countries of birth of recent immigrants (Statistics Canada, 2017), and Iranian refugees rank as the third highest group claiming refugee status in Canada (Immigration Refugee Board of Canada, 2022b). These emigrants from Iran could potentially differ from refugees from other countries with high rates of applications for asylum, who have experienced trauma due to violence, civil war, lack of food or access to healthcare (UNHCR, 2021b). Currently, there are no wars in Iran, and the main reasons for leaving the country would be the fear of persecution due to political activities, religious beliefs, or being a part of the LGBTQ community (UNHCR, 2021b).

Many refugees live in transitional, temporary locations until UNHCR officers review their claim for refugee status and determine eligibility for permanent resettlement. This process may take several years to complete (UNHCR, 2021b).1 Temporary settlement in transit countries may mean disruption in schooling for younger individuals with many refugees leaving school prior to completing high school and entering the workforce in these transitional contexts to earn money to survive. The negative experiences of refugees can lead to psychological trauma and adverse effects on academic adjustment and achievement (Banyard and Cantor, 2004), as well as on general social adjustment and acculturation (Iversen et al., 2014). Furthermore, there is evidence that poor mental health, such as trauma, and other psychological issues can have detrimental impacts on second language (L2) learning outcomes (e.g., Rashtchi et al., 2012; Zhou, 2016). These experiences of refugees contrast with the experiences of immigrants to Canada.

The Canadian immigration system is unique, as it has strict criteria for immigrant eligibility. Potential immigrants are allocated points for education, personal wealth, work experience and language proficiency in one of the two official languages (i.e., English, French) (Government of Canada, 2021). These points are used to determine eligibility. As a result of this policy, immigrants to Canada have high levels of post-secondary education with 40% of immigrants aged 25–64 having a bachelor's degree or higher as compared to just under one-quarter of the Canadian-born population of the same age (Statistics Canada, 2016).

Assumptions exist that refugees may have lower SES or lack the motivation to adopt the new culture of the host country (Djuve and Kavli, 2019). However, research comparing refugees and immigrants is lacking, and attitudes and policies related to refugees are usually based on intuitions and not on research evidence. Although studies have focused on the negative factors related to language acquisition and social adjustment in refugees (Finn, 2010), one longitudinal study reported that compared to economic immigrants, refugees perform better in terms of social adjustment, acculturation and economic growth in their new host country in the long term (Cortes, 2004). These findings might be due to the fact that refugees who had escaped their home country, might be unable to return, while immigrants might have this option if they choose (Cortes, 2004; Sheikh and Anderson, 2018). Therefore, refugees show greater investment in their new host country as it is their only choice to build a future. Previously discussed examples of differences between refugees and immigrants may play an important role in the ease of acculturation and language acquisition (Iversen et al., 2014). The present study aims to deepen our understanding by examining of similarities and differences between Iranian immigrant and refugee youth and young adults, by examining L1 and L2 oral language and literacy skills, and acculturation.

Iranian immigrants and refugees to Canada offer a unique opportunity to examine relations among language and literacy skills and acculturation in people who speak the same language and share the same heritage culture but emigrate for different reasons. Iran is a country in the Middle East where the official language is Farsi. Additionally, English is not an official language in Iran, nor is it taught as part of the official curriculum. In the recent past, some government authorities had recommended banning the teaching of English in schools (Thomson Reuters, 2018). However, some higher socio-economic status (SES) families opt to enroll in private English language schools or classes. Based on the relative scarcity and cost of these programs, many Iranians are not fluent English speakers prior to moving to Canada. Due to their reasons for migration, refugees are expected to have lower levels of English proficiency as they left their country quickly without having established a plan to emigrate. Also, refugees might not have had the financial resources or time to enroll in English classes prior to migration.

Although Iranian immigrants and refugees might differ on English acquisition, they have a common L1. Farsi is an Indo-European language which differs from English in many ways. These differences can have an impact on English (L2) acquisition. Farsi's writing system is similar to Arabic and is written from right to left (Nassaji and Geva, 1999). There are 32 letters in the Farsi alphabet that are similar to Arabic letters, with the Farsi alphabet having four additional letters. Only long vowels are represented by alphabet letters, while short vowels are represented as diacritics. Words in Farsi have a consonant-vowel structure (e.g., CVCV) with regular and consistent letter-sound mappings. Therefore, exposure to written Farsi provides little direct assistance in reading English, an irregular and inconsistent writing system which uses the Roman alphabet.

Furthermore, the grammatical structure of Farsi is different from English (Nassaji and Geva, 1999). The most common syntactic word order in Farsi is: subject + object + complement + verb, in contrast to English word order which is: subject + verb + object. Similar to English, Farsi uses concatenative morphological markers. However, Farsi verbs are more complex with simple and compound verbs and markers for first, second and third-person singular and plural. In terms of nouns, linguistic differences might present some challenges for Farsi-English speakers. For example, the default and most common version of a Farsi noun is its singular form, with plurals marked by a number modifier. Gender in Farsi is marked lexically by compounding rather than grammatically. The present study examined similarities and differences in L2, English, skills as a function of immigration status.

Reading comprehension skills are important because they are required for higher academic achievement and career attainment (Abdur-Rahman et al., 1994; Cook, 2006). One model of reading comprehension, the simple view of reading (SVR), posits that Reading Comprehension = Decoding x Linguistic Comprehension (R = D × LC) (Gough and Tunmer, 1986). If either decoding (word reading) or listening comprehension has a value of 0, the individual's reading comprehension level will equal 0 (Gough and Tunmer, 1986). Components of decoding, specifically orthographic and phonological processing skills, were significant contributors to L2 reading comprehension, silent word reading rate, and single word reading in Farsi-English speaking adults (Nassaji and Geva, 1999). Nassaji and Geva (1999) found significant correlations between speed and accuracy on L2 measures of phonological, orthographic, syntactic, and semantic skills. Decoding and linguistic comprehension skills in English tend to be lower for immigrants and refugees due to a lack of exposure to English (Rott, 1999). Additionally, differences between Farsi and English oral and written language processes suggest that exposure to one language does not result in automatic “transfer” of skills to the other language.

Successful integration involves social engagement in and acculturation to one's new community. Culture refers to the set of meanings, beliefs, values, and understandings, which are held by a group of people (Shore, 2002). Acculturation is the process by which individuals adapt to their new country and culture, as they integrate their original culture with the new one (Berry, 1997). This process leads to the changes in the individual's values, attitudes, behaviors, and identities (Berry, 2003). Sociocultural adaptation includes a person's effectiveness in communicating with others, including language and literacy skills, and fitting into the cultural norms of the new society (Jia et al., 2014; Ferreira et al., 2017). Enculturation is defined as maintaining cultural affiliations and values with one's culture of origin (Berry, 1997).

Canadian research findings suggest that it is possible for immigrants to increase feelings of affiliation to mainstream culture while maintaining affiliation to their heritage culture (Berry, 1997). These findings suggest that enculturation and acculturation can be measured separately, on independent continua (Berry, 1997). Research has shown that changes in cultural affiliation or acculturation have a positive effect on language and literacy skills in the language of the country to which a person immigrates (Schumann, 1986). In a reciprocal relationship, one important predictor of successful acculturation involves how well an individual can understand and use the dominant societal language of their new host country. However, the evidence is mixed in terms of the relations between acculturation and language and literacy (Gardner et al., 1999). The present study compared Iranian refugees and immigrants to Canada on English language and literacy skills as well as cultural adaptation as a function of the method of migration.

Acculturation and participation within a new society may facilitate L2 acquisition. Nassaji (2015) discusses interactional feedback, which occurs during communicative interactions with others. For instance, when an individual with lower English proficiency speaks to a person who has a higher level of English proficiency, the former person may receive explicit feedback by being corrected by the latter person, or implicit feedback by simply hearing the correct pronunciation or grammar. This form of learning is called the “negotiation and modification” process, which helps to address common linguistic and communication challenges encountered by newcomers when speaking their L2 (Nassaji, 2015).

Studies also suggest the importance of proficiency in the language spoken by the mainstream culture to facilitate adaptation to a new culture (Zane and Mak, 2003). For example, different ethnic groups demonstrated different patterns of acculturation in educational settings (Hsiao and Wittig, 2008). Additionally, academic acculturation has been considered important for the academic success and integration of university students from other cultures (Cheng and Fox, 2017). Additionally, studies examining L2 development in refugees use inconsistent definitions and methodologies which make it difficult to generalize findings (Damaschke-Deitrick et al., 2021). Therefore, it is important to consider similarities and differences between immigrants and refugees of specific cultural backgrounds because these variables affect adaptation and academic success in a new host country (Naidoo, 2015). In the case of Iranian immigrants and refugees, large Iranian communities exist in some Canadian cities such as Toronto, Vancouver, or Montreal (Statistics Canada, 2016). Iranian newcomers who are not fluent in English can engage in activities within the Iranian community such as shopping, medical appointments, and many other daily activities, which may lead to few opportunities and little need to interact with other parts of Canadian society that require English language proficiency. The focus of the present study was to examine relations among levels of cultural affiliation, method of migration and language and literacy skills for newcomers from Iran living in Canada.

In 2022, Canada's population is estimated at just over 39 million people (Statistics Canada, 2022). In 2022, the Government of Canada announced plans to admit approximately 500,000 immigrants per year from 2023 to 2025 (Immigration Refugee Board of Canada, 2022a). With this rate of immigration admissions, Canada admits the equivalent of 5% of its total population every 10 years. Therefore, different aspects of migrants' characteristics, such as their mental health, education, integration into the mainstream culture, and their contribution to the workforce, have implications for Canadian society. To our knowledge, no studies compare newcomer immigrants and refugees, specifically those who emigrated from Iran to Canada. Furthermore, although the relationships among acculturation and acquiring the host country's language have been studied to a certain degree, the number of studies that focus on contextual and individual factors related to newcomer migrants, especially refugees, is limited (Maehler et al., 2021), especially in relation to migrants to Canada. The present study examined similarities and differences in the level of English language and literacy skills and socio-cultural variables between immigrants and refugees to Canada with different premigration and immigration experiences. However, given that this study examines the same country of origin, specific L1 factors and cultural variables are expected to be similar across groups.

This study examined the following questions.

1. Do Iranian immigrants and refugees differ on English language and literacy skills, and cultural adjustment after their arrival to Canada?

2. Are interrelations among skills similar or different for the two groups?

3. Do Iranian immigrants and refugees differ in terms of rates of experienced trauma? How is the presence of trauma related to L2 skills among Iranian migrants?

The present study explored similarities and differences among Iranian refugees and immigrants, in terms of acculturation and English language skills. A series of standardized and experimental measures and questionnaires were administered to determine performance on language and literacy measures. This study considered the relations among language, literacy and socio-cultural variables. The Iranian immigrants and refugees were recent immigrants to Canada.

Given the criteria for immigrating to Canada, we predicted that Iranian immigrants would perform significantly better compared to Iranian refugees on all English language and literacy measures. The present study examined relations among cognitive-linguistic and socio-cultural variables related to reading comprehension for refugees and immigrant groups. The cognitive-linguistic variables were consistent with components of the simple view of reading, specifically decoding and vocabulary.

The sample (N = 45) consisted of the two groups categorized based on method of migration, specifically new immigrants, and refugees. Twenty refugees (12 males, eight females) (Mage = 23.15, SD = 4.02), and 25 immigrants (14 males, 11 females) (Mage = 19.24, SD = 2.06) were recruited for this study.

All the participants were Iranians who had migrated and settled in Canada within 24 months of the data collection. Iran's education system requires students to study for 12 years before entering post-secondary studies, normally at age 18. Based on their age, some participants in the refugee group had disrupted schooling (N = 14).

The participants received a questionnaire that examined demographic information and language use. They also were administered a battery of standardized language and literacy measures as well as measures of cultural affiliation. Due to the potentially limited levels of English language fluency of the participants, all the consent forms and instructions as well as the demographic and socioemotional measures were translated into Farsi. The researcher was also fluent in Farsi and English.

Demographic information was collected, including the participants' age, gender, and ethnicity, as well as the languages that they speak. Participants were asked about their length of residence in Canada, the number of years they studied English, and when they last attended school. The participants were also asked about their scores on English standardized assessments performed at government-funded agencies, or alternatively, their IELTS or TOEFL scores. The assessments were completed upon arrival or shortly after settling in Canada. The immigrant and refugee groups were also asked to rate their own and their parents' English language proficiency on a 4-point scale ranging from a score of 1 for “no fluency at all”, to a score of 4 for “completely fluent”.

All participants were asked about their parents' education and occupation in their native country as measures of socio-economic status.2 The parental education level and occupation were then ranked in terms of socio-economic status based on Four-Factor Index of Social Status (Hollingshead, 2011). The Hollingshead Index assigns numeric points for the highest level of education attained by the parents using a 7-point scale where higher numbers represent higher levels of education attainment. Furthermore, Hollingshead's occupational scale assign numeric points for occupation categories using a 9-point scale where higher numbers represent higher status employment.

Participants were asked about the people they reside with currently and their proximity to family members to assess familial financial and social support. Participants were also asked to specify their highest level of education and their current and former occupations if applicable. The demographic measure was translated and administered in Farsi.

This measure surveyed the participants' language use and preferences in terms of cultural affiliations and activities. The goal was to examine the participant's level of involvement with Anglo-Canadian culture and/or Persian/Iranian culture. The Vancouver Index of Acculturation (VIA) (Ryder et al., 2000) is comprised of 27 statements about activities related to culturation affiliation that are rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from “Not at all” to “Almost always”. Twelve statements asked about mainstream culture in terms of how often participants engaged in daily activities associated with the new culture, while 15 statements measured maintenance of their heritage culture with similar items (adapted from Ryder et al., 2000). For example, participants' affiliation with Canadian culture was measured using statements such as “I enjoy watching movies in English”, while affiliation with their heritage culture was measured using “I enjoy watching movies in Farsi”. Similar statements were provided for preferences for food, activities, and socialization. This measure was highly reliable for both mainstream and heritage culture with the Cronbach's alpha 0.85 and 0.91, respectively (Ryder et al., 2000).

To test the participants' vocabulary, the Expressive One-Word Picture Vocabulary Test (EOWPVT) (Gardner, 1990) was administered. The participants named the objects, actions or concepts presented in pictures (maximum 170). The initial items include high-frequency words such as “bird,” “scissors,” and “bus.” The objects and their labels became progressively more difficult, with low frequency vocabulary such as “louver” and “trellis”. The test was terminated after six consecutive errors or when the participant reached the final item. The test's reliability for internal consistency ranges between 0.93 and 0.97 across all ages.

Word reading was measured using a subtest of the Test of Word Reading Efficiency (TOWRE) (Torgesen et al., 1999). This measure assessed the participants' sight word recognition efficiency. The items ranged from short, high-frequency words such as “is,” “up,” and “cat” to longer words such as “instruction”, and “transient” (maximum 104). The test was discontinued after 60 s or six consecutive errors. The average alternate forms and test-retest reliability for subtests was over 0.90.

The Woodcock-Johnson Test of Achievement III, Passage Comprehension (WJ III: Woodcock et al., 2001) was used to measure reading comprehension in English. The participants responded to questions in order to measure their comprehension of the passages they read. The initial passages included short, simple passages to allow the participants to succeed. For instance, the participants read: “When you go to the library, you will find many things to [blank]”, where the correct response was “read”. The passages became gradually longer and more difficult with more complex sentences and lower frequency words. The test was terminated after either six consecutive errors, or when the participant had completed the entire test. The median test-retest reliability coefficient was 0.92 (McGrew and Woodcock, 2001).

The participants were asked to reply “Yes”, “No” or “Prefer not say” to the following question: “Have you ever been seriously afraid for your safety in your own home?” If the participant chose “Yes” for the previous question, he or she was asked the following open-ended question: “Would you like to tell me why?”. Due to the concerns about provoking negative feelings related to the potential past traumatic experiences, the question was left open-ended without asking any specific details. Implicit in the wording of these questions was the opportunity for the participants to refuse to respond.

This measure consisted of six questions, which aimed to examine the participants' emotional states within the past 30 days before completing the questionnaire. The scale is designed to be self-administered and the participants are asked to rate their restlessness, nervousness, hopelessness, depressed feelings, worthlessness, and difficulty with completing tasks (Kessler et al., 2002). Participants chose a response to the questions on a 5-point Likert scale to questions about anxiety, depression and other socio-emotional symptoms. For instance, the participants were provided with a statement that read “In the past 30 days, I have felt anxious”, and the participants were asked to choose a number from 1 (not at all) to 5 (all the time).

Participant recruitment was conducted in southern Ontario, Canada. Recruitment was conducted using snowball sampling, ads, and community outreach. To recruit participants, a series of flyers and ads were posted in the areas with a high Iranian population. To recruit refugee participants, the researchers reached out to community shelter staff to determine if clients were willing to participate in the study. Both Iranian immigrants and Iranian refugees were asked to refer other immigrants or refugees who they thought would fit the research criteria. The participants received a monetary incentive as compensation for their time after participating in the study. Each participant attended the data collection session individually. The researcher was present to collect the data face to face (testing was conducted prior to COVID-19). This study was reviewed and approved by the university Research Ethics Board and all participants were treated in accordance with APA/CPA ethical guidelines.

Initial analyses included group comparisons on demographic variables, language and literacy and socio-cultural measures. Then analyses were conducted to examine variables related to language and literacy skills for the immigrant and refugee groups. SPSS software was used to analyze the data. The means, frequencies and standard deviations were calculated for all the measures. No ceiling or floor effects were found. Raw scores were used for all the analyses as norms on the standardized measures are not applicable for the two Iranian groups. Appropriate analyses were conducted to ensure homogeneity of variance for the comparison analyses.

The descriptive analyses for the groups revealed no differences in the length of time that the immigrants and refugees were present in Canada. There were no significant differences between the refugee and immigrant groups in terms of the presence of family members, or other relatives in Canada (see Table 1).

Analyses were performed on the English scores that the two groups reported obtaining upon their arrival in Canada. These scores were based on their English assessment results performed either at English assessment centers in Canada, or their TOEFL or IELTS scores submitted upon arrival. The assessment scores were divided into four categories: Basic (1), Beginner (2), Intermediate (3), and Advanced (4) to allow for comparisons across measures. Immigrants had higher scores (M = 3.16, SD = 0.48) than the refugee group (M = 1.70, SD = 0.65). On average, immigrants scored at an intermediate level for English fluency, while refugees scored at a basic level on their initial English tests.

A Pearson Chi-square test was conducted to compare the participants' migration category and the presence or absence of trauma. Some participants in each of the two groups reported a traumatic experience in their past. Although the participants were given the option for “prefer not to answer”, none of the participants chose that option, and they responded with either “yes” or “no,” which justified using a Chi-Square test. The results of the Pearson Chi-square test showed that immigrants and refugees differed in terms of the number of reported traumatic experiences, where refugees reported significantly higher rates of trauma, = 4.54, p = 0.033.

Furthermore, although some immigrants still reported traumatic experiences, upon reviewing the participants' responses to the qualitative portion of the trauma questionnaire, it was revealed that the notion of traumatic experiences was different between the two groups. For example, the refugees' traumatic experiences included fear of persecution, torture, or loss of their life. In contrast, the immigrant group reported similar psychological traumas related to issues such as fear of being alone at home or witnessing their parents arguing.

To examine the migrants' psychological distress level post-migration, their total score on the Kessler Psychological Distress test was calculated. There were no significant differences between refugees (M = 21.85, SD = 6.20), and immigrants (M = 22.01, SD = 5.60) in terms of their psychological distress, F(1,41) = 0.007, p = 0.934.

A series of one-way ANOVA tests was conducted. The effects of trauma on refugees and immigrants were analyzed separately; the aggregated data for both refugees and immigrants were examined as well. The presence of trauma was not a significant predictor for any of the English fluency skills for either group. The aggregated data also showed no significant effects of trauma across all the participants in this study (see Table 2).

A one-way ANOVA was conducted to compare the groups on their SES. Parental education and parental occupation were used as the socio-economic factors in this study. The one-way ANOVA results revealed statistically significant differences in indicators of socio-economic status based on participants' migration category. The refugees and immigrants differed significantly on paternal education, F(1,42) = 4.58, p = 0.038, maternal education, F(1,41) = 7.42, p = 0.009, paternal occupation, F(1,35) = 11.57, p = 0.002, and maternal occupation, F(1,37) = 4.97, p = 0.032, with the immigrant group having higher scores (see Table 3). The percentage of parents who had completed post-secondary education was high for both samples. For the refugees, 55% of fathers and 30% of mothers had completed at least a university degree, while for the immigrants, 72% of the fathers and 62% of the mothers had completed at least a university degree.

Socio-cultural variables included in the analysis were mainstream acculturation, and heritage enculturation measure. Iranian refugees and Iranian immigrants did not differ significantly in terms of either mainstream acculturation or heritage enculturation (see Table 2). In addition, both groups endorsed a significantly larger percentage of enculturation items than acculturation items, 57.4 vs. 38.7% for the refugees, t(17) = 7.03, p < 0.001, and 55.8 vs. 39.8% for the immigrants, t(19) = 5.75, p < 0.001. However, the subscales were not significantly correlated with each other for the refugee or immigrant groups, rs = −0.215 and −0.057, ps > 0.05.

The differences between the two groups in terms of English language and literacy were assessed using three measures: the Woodcock-Johnson reading comprehension, the Expressive One-Word Picture Vocabulary and the Test of Word Reading Efficiency. One-way ANOVA results revealed a statistically significant difference in English skills based on the participants' migration type. Immigrants scored significantly higher on English passage comprehension, M = 19.47, SD = 5.16, in comparison to the refugees, M = 12.10, SD = 3.68, F(1,43) = 30.08, p < 0.001. Moreover, the immigrants had significantly higher English vocabulary knowledge M = 65.77, SD = 23.58, when compared to the refugees, M = 41.80, SD = 14.59, F(1,43) = 16.04, p < 0.001. Additionally, the immigrants scored higher on the English word reading efficiency, M = 82.04, SD = 9.17, than the refugees, M = 67.15, SD = 10.02, F(1,43) = 28.06, p < 0.001 (see Table 2).

The relationships among socio-cultural, language and literacy variables were examined for the Iranian refugees, and Iranian immigrants. Bivariate correlations were calculated for each group for the variables in the study (see Table 4). For the refugees, the three literacy variables were moderately to highly correlated, rs = 0.556–0.729, ps < 0.05. Acculturation was highly correlated with English reading comprehension, but heritage enculturation was negatively correlated with English vocabulary and English word reading fluency (see Table 4). In terms of relations among SES variables and linguistic measures, refugees' maternal occupation was positively correlated with English word reading and the participants' English assessment results.

For the immigrants, reading comprehension was related to vocabulary r(23) = 0.600, p = 0.002 and word reading efficiency r(24) = 0.669, p < 0.001. Both parents' occupations, as well as maternal education were positively correlated with the participants' English skills, rs = 0.457–0.591, ps < 0.05 (see Table 4). The results of the correlational analyses were used to examine variables related to reading comprehension and vocabulary.

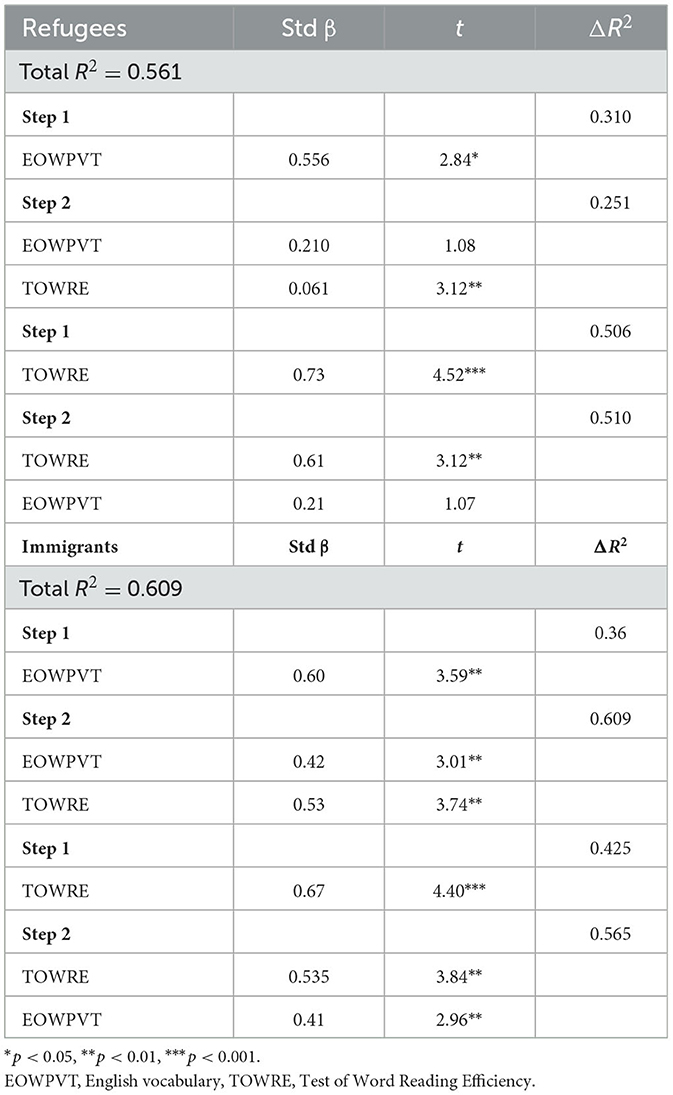

We explored linguistic variables related to English reading comprehension for refugees and immigrants. Consistent with the simple view of reading, English vocabulary and word reading efficiency were selected as predictor variables. English vocabulary was entered as the first step of a 2-step hierarchical regression analysis, and English word reading efficiency was entered as the second independent variable in the final model. For completeness the order of the variables was reversed. The results for each group are provided below.

The total variance explained by the final model for English reading comprehension was R2 = 0.561, F(2,17) = 10.88, p = 0.001. Word reading efficiency was the only variable uniquely related to English reading comprehension, explaining 25.1% of the variance for the refugees, β = 0.610, t(17) = 3.12, p = 0.006 (see Table 5). Vocabulary did not contribute significant variance in reading comprehension for this group as the first or second step.

Table 5. Summary of hierarchical regression analysis: English variables as predictors of English reading comprehension for refugees and immigrants.

The total variance explained by the final model for English reading comprehension was R2 = 0.609, F(2,22) = 17.104, p < 0.01. Both English vocabulary skills, β = 0.425, t(24) = 3.01, p = 0.006, and English word reading efficiency, β = 0.529, t(22) = 3.74, p = 0.001, were significantly related English reading comprehension in the final step for the immigrant group (see Table 5). To explore this relationship further, the same analysis was conducted with the order of independent variables in the hierarchical regression reversed. The results of these analyses revealed that vocabulary and word reading explained 11% and 24.9% unique variance in reading comprehension, respectively (see Table 5).

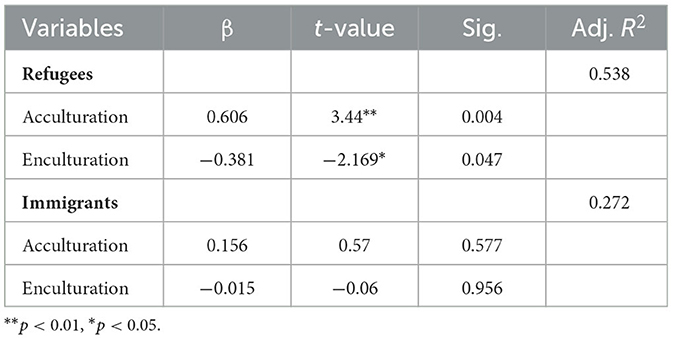

To explore if socio-cultural variables were related to English reading comprehension for refugees and immigrants, acculturation and heritage enculturation were entered as independent variables in a linear regression analysis. The results of the analyses for each group are provided below.

The linear regression model with both variables was significant with a total R2 = 0.538, F(2,17) = 8.47, p = 0.003. Acculturation was significantly positively related to English reading comprehension for the refugee group, β = 0.606, t(17) = 3.44, p = 0.004. Enculturation was significantly negatively related to English reading comprehension in the refugee group, β = −3.81, t(17) = −2.16, p = 0.047 (see Table 6).

Table 6. Acculturation and heritage enculturation variables as predictors for English reading comprehension among Iranian refugees.

The linear regression model with both variables was not significant, R2 = 0.027, F(2,16) = 0.218, p = 0.806. Neither acculturation nor enculturation were significantly related to English reading comprehension in the immigrant group (see Table 6).

To explore relations between socio-cultural variables and English vocabulary for refugees, and immigrants, acculturation and heritage enculturation were entered as independent variables in a linear regression analysis. The results regarding each group are provided below.

The linear regression model with both predictors produced a significant R2 = 0.416, F(2,17) = 5.33, p = 0.018. Enculturation was significantly negatively related to English vocabulary for the refugees, β = −0.472, t(17) = −2.38, p = 0.030. Acculturation was not significantly related to English vocabulary (see Table 7).

The linear regression model with both predictors was not significant, R2 = 0.064, F(2,16) = 0.546, p = 0.590. Neither acculturation nor enculturation were significantly related to English vocabulary in the immigrant group (see Table 7).

To examine the effects of language exposure through socialization with Farsi or English speakers, participants' responses to questions in the acculturation scale that queried socialization with English-speaking and Farsi-speaking individuals were analyzed separately. The results showed no significant differences between Iranian immigrants and refugees regarding socialization with English-speaking people in the community F(1,40) = 0.790, p = 0.379, having English-speaking friends, F(1,40) = 1.51, p = 0.226, or having Farsi speaking friends F(1,40) = 0.332, p = 0.568.

Group differences were found in variables related to SES. The immigrants had a higher SES level than the refugee group, with the parents of the immigrant group having higher levels of parental education and occupation. For example, on average, fathers of refugees had completed some college while mothers had completed high school. For the immigrants, on average the fathers had completed college or university, while the mothers had at least some college. The group differences are likely related to the point-system used to determine eligibility to immigrate to Canada. However, most of the parents of the immigrants and refugees had some post-secondary education in their home country. These findings are consistent with data from Statistics Canada, reporting that 40% of immigrants aged 25–64 had a bachelor's degree or higher as compared to just under one-quarter of the Canadian-born population of the same age (Statistics Canada, 2016).

Different patterns were found for the two groups for English skills. In comparison to the immigrants, refugees had lower skills for all the English measures, specifically vocabulary, word reading and reading comprehension as well as lower English language scores reported at the time of migration. The differences between these Iranian immigrant and refugee groups could be related to multiple factors. For example, preparation for migration may include acquiring the language of the host country. Members of the Iranian immigrant group might have been planning to immigrate to Canada. Parents could have enrolled themselves or their children in English language classes to enhance their chances of getting admitted to Canada by gaining increased points in terms of fluency in one of Canada's official languages. Learning English could also facilitate a transition to Canadian society and future academic success in Canada. In contrast, refugees were forced to leave their country without prior preparation, which could preclude learning English. The data revealed that the immigrants had significantly higher English skills upon arriving in Canada, which supports the above explanation. Another possible explanation for the differences in English skills is the higher SES of the Iranian immigrant group. Higher parental education likely resulted in greater financial resources available to pay for English lessons while in Iran. Finally, higher levels of parental education are associated with a greater likelihood of seeking enriching educational opportunities for their children, such as learning English outside of school.

The comparison of the Iranian immigrant and refugee groups also included examining which variables were related to English reading and vocabulary. The variables related to English reading comprehension were compatible with components associated with the simple view of reading. Consistent with research examining the simple view of reading in readers of different skill levels (Catts et al., 2005), English word reading was the only cognitive-linguistic variable related to English reading comprehension for the refugee group. The refugee group could be viewed as beginner learners of English for whom decoding skill was still the main variable related to comprehending English text. On the other hand, both English word reading, and English vocabulary knowledge were related to English reading comprehension in the Iranian immigrant group, who were the more advanced learners of English. Although English word reading was still an important factor in comprehending English text, vocabulary knowledge provided a source of variability beyond single word decoding (Proctor et al., 2012; Gottardo et al., 2018). Research conducted with a group of adult native English speakers with a wide range of skills shows the role for word reading and vocabulary in relation to text comprehension (Braze et al., 2007). These differential predictors of reading comprehension in learners of different abilities are compatible with previous research conducted with monolingual English-speaking children and youth (Catts et al., 2005) as well as with adolescent immigrants who are newcomers compared to established immigrants (Pasquarella et al., 2012). Therefore, both components of reading comprehension, specifically word reading and vocabulary, should be assessed when evaluating literacy in newcomer English L2 learners.

The findings of this study are consistent with other Canadian data that demonstrates that enculturation and acculturation are orthogonal (Berry, 1997). The current findings provide insight into the relationship between L2 acquisition and cultural adjustment with a focus on Iranian immigrants and refugee youth and young adults in Canada. For the refugees, the acculturation and enculturation variables functioned in predictable ways, with acculturation being positively related to English reading comprehension, while enculturation was negatively related to English vocabulary and reading comprehension. Another possible factor for the refugees could be the desire to integrate into Canadian culture, which linked acculturation/enculturation to L2 oral proficiency.

Neither acculturation nor enculturation was related to English vocabulary or reading comprehension for the Iranian immigrant group. Therefore, cultural affiliation was not related to English language proficiency in this group. These findings suggest that sources of variability in reading comprehension in this group were related to cognitive-linguistic skills acquired through formal education. These findings are consistent with patterns found for intermediate learners as described by the simple view of reading (Catts et al., 2005).

Another important factors to consider are similarities and differences between refugees and immigrants in their socialization with English-speaking peers. These interactions can lead to informal learning, a process known as “negotiation and modification” (Nassaji, 2015). The results suggested that the two groups did not differ in terms of their socialization tendencies as measured by considering only the parts of acculturation measure related to socialization after arrival to Canada. However, the differences in terms of English proficiency between the two groups seemed to be present upon arrival to Canada, with immigrants having a significantly higher English knowledge based on their assessments. These differences could be due to the immigrants' enrolment in English classes before migrating to Canada. These superior English language skills continue to be present at the time of data collection. These findings align with the expectations for each group concerning their reasons for migration and their ability to plan. Additionally, past trauma were not related to differences in English proficiency in these groups, and the two groups did not differ significantly in terms of recent psychological distress.

The study's findings might be unique to the Canadian context or to Iranian immigrants and refugees. The results can assist in reconciling previous results regarding the relations between language and literacy skills and acculturation for immigrants and refugees. Many studies do not explicitly differentiate between immigrant and refugee participants. For instance, the refugees' lower English literacy skills indicate the need for greater language learning supports for refugees in Canada to facilitate language acquisition among the refugee population. This study confirms the importance of providing more support for refugees in Canada to address the strengths and challenges that refugees face.

As the results showed, heritage enculturation among refugees was significantly negatively related to English vocabulary and reading comprehension and, by extension, English language proficiency and achievement. The findings from this study suggest that educators take a more flexible approach, recognizing the different linguistic needs of newcomers in relation to language and literacy classes based on the strengths and difficulties commensurate with different groups of learners. For instance, refugees may benefit more from a more extensive focus on vocabulary, as well as more general support to learn English due to their lower English language skills. Better English language skills can lead to greater educational and occupational opportunities for refugee newcomers. Conversely, more interaction with English speakers can lead to better language skills and more opportunities for acculturation for the refugee group (Naidoo, 2008; Nassaji, 2015). For the immigrants, the lack of a relationship between the cultural affiliation variables and English proficiency suggests a different path. For example, structured English language instruction or enrollment in post-secondary education could enhance English language and literacy skills in this group.

Although the results of this study revealed no observed significant effects of traumatic experiences on language skills, it is still important to consider the higher prevalence of trauma among the refugee population. Therefore, educators and other service providers who work with the refugee population should consider the prevalence of trauma among refugees, and its potential effects on learning and social functioning, beyond the findings discussed in this study.

One of the major considerations regarding this study is the sample size with about 20 participants per group. The limited number of participants would negatively impact the sample power for the analyses. Therefore, the small sample size must be taken into consideration when drawing conclusions from this study. Further studies with larger sample sizes could further examine the topics examined in this study. However, it is important to explore optimal strategies to ensure refugees' participation and elaboration on their feelings and experiences. This issue was also present when conducting this study, specifically when it came to asking the participants about their traumatic experiences in the past. To ensure the participants' comfort with sharing information and minimizing the risk of provoking adverse emotional responses, the question about the trauma was broad and brief. The main reason to take this approach was that a deeper exploration of the trauma may have provoked potential PTSD symptoms that may have required skilled mental health workers to address such adverse effects. Therefore, to further explore the trauma factor, a collaboration with researchers and clinicians or mental health experts would be ideal.

During the course of this study, it was noticed by the researchers that refugees were significantly more hesitant to participate in the study due to reported privacy concerns and fear of potential data leaks to the government of the country they had fled. They were also worried about potential negative impacts on their immigration status in Canada. It was challenging to reassure the participants that their identifying information would be protected and that no one besides the researchers would have access to such information. This constraint should be an essential consideration for researchers interested in conducting research with refugees in terms of building a good rapport with the participants. For this study, steps were taken to ensure the participants felt safe to share their experiences, including having the principal investigator be a member of the community. However, it is still expected that the participants, especially the refugees, may be hesitant to share their experiences. These issues further emphasize the need for more studies, specifically on the refugee population, to ensure further understanding of this group and their needs.

Another limitation included the existence of familial variables that were not measured in this study. For instance, family members of newcomer immigrants may not be required to achieve the strict immigration criteria, such as having knowledge of English (Refugees and Citizenship Canada, 2019).

Finally, the Iranian immigrants and refugees were selected based on their status as newcomers with <2 years of residency in Canada. Longer-term effects of immigration status on language and literacy skills and acculturation might reveal different and interesting patterns. Additionally, 2 years might not be a sufficient length of time to demonstrate the effects of living in Canada on L2 skills and acculturation.

Despite the limitations, this study revealed some interesting findings. The results of the current study are consistent with the simple view of reading model in terms of the contributions of word reading and vocabulary to reading comprehension. However, group differences were found based on English language proficiency and the variables related to reading comprehension. In addition, acculturation and enculturation were related in predictable ways to reading comprehension and vocabulary knowledge for the refugee group but not for the immigrant group. Both groups of newcomers reported relatively high levels of parental education, which is contrary to stereotypes held by the many laypersons and the media, especially for refugees. The findings point to the importance of examining and questioning popular misconceptions about groups of immigrants and refugees and the importance of basing policy decisions on empirical findings.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Research Ethics Board, Wilfrid Laurier University. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

AJ and AG conceived the presented idea. AJ performed the participant recruitment and data collection. AG verified the analytical methods and supervised the findings related to the current study. Both authors contributed to the final manuscript and discussed the results.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. ^The present study was conducted prior to the COVID19 pandemic, which has exacerbated wait times and immigration challenges.

2. ^Although family income is often used to measure SES in non-immigrant families, many immigrants are under-employed and therefore income often does not match with other indicators of SES.

Abdur-Rahman, V., Femea, P., and Gaines, C. (1994). The nurse entrance test (NET): An early predictor of academic success. Assoc. Black Nurs. Fac. 5, 10–14.

Banyard, V. L., and Cantor, E. N. (2004). Adjustment to college among trauma survivors: an exploratory study of resilience. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 45, 207–221. doi: 10.1353/csd.2004.0017

Berry, J. W. (1997). Immigration, acculturation and adaptation. Appl. Psychol. 1, 5–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-0597.1997.tb01087.x

Berry, J. W. (2003). “Conceptual approaches to acculturation,” in Acculturation: Advances in Theory, Measurement, and Applied Research, eds K. Chun, P. Balls-Organista, and G. Martin (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association Press), 17–37. doi: 10.1037/10472-004

Bigelow, M., and Tarone, E. (2004). The role of literacy level in second language acquisition: doesn't who we study determine what we know? TESOL Q. 38, 689–700. doi: 10.2307/3588285

Braze, D., Tabor, W., Shankweiler, D. P., and Mencl, W. E. (2007). Speaking up for vocabulary: reading skill differences in young adults. J. Learn. Disabil. 40, 226–243. doi: 10.1177/00222194070400030401

Catts, H. W., Hogan, T. P., and Adlof, S. M. (2005). “Developmental changes in reading and reading disabilities,” in The Connections between Language and Reading Disabilities, eds H. W. Catts, and A. G. Kamhi (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers), 25–40.

Cheng, L., and Fox, J. (2017). Assessment in Language Classroom: Teachers Supporting Student Learning. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Cook, J. D. M. (2006). The Relationship Between Reading Comprehension Skill Assessment Methods and Academic Success for First Semester Students in a Selected Bachelor of Science in Nursing Program in Texas (Doctoral dissertation). Texas A&M University. Available online at: https://hdl.handle.net/1969.1/4728 (accessed June 27, 2023).

Cortes, K. E. (2004). Are refugees different from economic immigrants? Some empirical evidence on the heterogeneity of immigrant groups in the United States. Rev. Econ. Stat. 86, 465–480. doi: 10.1162/003465304323031058

Damaschke-Deitrick, L., Wiseman, A. W., Fleckenstein, J., Maehler, D. B., P'́otzschke, S., Ramos, H., et al. (2021). “Language as a predictor and an outcome of acculturation: A review of research on refugee children and youth,” in International Perspectives on School Settings, Education Policy and Digital Strategies: A Transatlantic Discourse in Education Research, 1st Edn, eds A. Wilmers and S. Jornitz (Verlag Barbara Budrich), 110–119. doi: 10.2307/j.ctv1gbrzf4.9

Djuve, A. B., and Kavli, H. C. (2019). Refugee integration policy the Norwegian way – why good ideas fail and bad ideas prevail. Transfer 25, 25–42. doi: 10.1177/1024258918807135

Ferreira, A., Gottardo, A., Javier, C., Schwieter, J. W., and Jia, F. (2017). Reading comprehension: the role of acculturation, language dominance, and socioeconomic status in cross-linguistic relations. Rev. Espanola Ling. Aplicada 29, 613–639. doi: 10.1075/resla.29.2.09fer

Finn, H. B. (2010). Overcoming barriers: adult refugee trauma survivors in a learning community. Tesol Q. 44, 586–596. doi: 10.5054/tq.2010.232338

Gardner, M. F. (1990). EOWPVT-R: Expressive One-Word Picture Vocabulary Test, Revised. Novato, CA: Academic Therapy Publications.

Gardner, R. C., Masgoret, A.-M., and Tremblay, P. F. (1999). Home background characteristics and second language learning. J. Lang. Soc. Psychol. 18, 419–437. doi: 10.1177/0261927X99018004004

Gottardo, A., Mirza, A., Koh, P. W., Ferreira, A., and Javier, C. (2018). Unpacking listening comprehension: the role of vocabulary, morphology and syntax in reading comprehension. Read. Writing Interdiscipl. J. 31, 1741–1764. doi: 10.1007/s11145-017-9736-2

Gough, P. B., and Tunmer, W. E. (1986). Decoding, reading, and reading disability. Remedial Special Educ. 7, 6–10. doi: 10.1177/074193258600700104

Government of Canada (2021). Summary of Maximum Points Per Factor for Express Entry Candidates. Available online at: https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/services/immigrate-canada/express-entry/eligibility/criteria-comprehensive-ranking-system/grid.html (accessed January 24, 2023).

Hollingshead, A. B. (2011). Four factor index of social status. Yale J. Sociol. 8, 11–53. doi: 10.1016/j.materresbull.2011.04.018

Hormozi, T., Miller, M. M., and Banford, A. (2018). First-generation Iranian refugees' acculturation in the United States: a focus on resilience. Contemp. Fam. Ther. 40, 276–283. doi: 10.1007/s10591-018-9459-9

Hsiao, J., and Wittig, M. A. (2008). Acculturation among three racial/ethnic groups of host and immigrant adolescents. Am. J. Commun. Psychol. 42, 286–297. doi: 10.1007/s10464-008-9205-9

Immigration Refugee Board of Canada (2022b). Refugee Protection Claims (New System) by Country of Alleged Persecution (2021). Available online at: https://irb.gc.ca/en/statistics/protection/Pages/RPDStat2021.aspx (accessed January 24, 2023).

Immigration Refugee Board of Canada. (2022a). Supplementary Information for the 2023-2025 Immigration Levels Plan. Available online at: https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/news/notices/supplementary-immigration-levels-2023-2025.html (accessed June 27, 2023).

Iversen, V. C., Sveaass, N., and Morken, G. (2014). The role of trauma and psychological distress on motivation for foreign language acquisition among refugees. Int. J. Cult. Ment. Health. 7, 59–67. doi: 10.1080/17542863.2012.695384

Jia, F., Gottardo, A., Koh, P. W., Chen, X., and Pasquarella, A. (2014). The role of acculturation in reading a second language: Its relation to English literacy skills in immigrant Chinese adolescents. Read. Res. Q. 49, 251–261. doi: 10.1002/rrq.69

Kessler, R. C., Andrews, G., Colpe, L. J., Hiripi, E., Mroczek, D. K., Normand, S. L. T., et al. (2002). Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol. Med. 32, 959–976. doi: 10.1017/S0033291702006074

Kurvers, J. (2015). Emerging literacy in adult second-language learners: a synthesis of research findings in the Netherlands. Writ. Syst. Res. 7, 58–78. doi: 10.1080/17586801.2014.943149

Maehler, D. B., Pötzschke, S., Ramos, H., Pritchard, P., and Fleckenstein, J. (2021). Studies on the acculturation of young refugees in the educational domain: a scoping review of research and methods. Adolesc. Res. Rev. 6, 15–31. doi: 10.1007/s40894-019-00129-7

McGrew, K. S., and Woodcock, R. W. (2001). Technical Manual. Woodcock-Johnson III. Itasca, IL: Riverside Publishing.

Naidoo, L. (2008). Supporting African refugees in Greater Western Sydney: a critical ethnography of after-school homework tutoring centres. Educ. Res. Policy Pract. 7, 139–150. doi: 10.1007/s10671-008-9046-1

Naidoo, L. (2015). Educating refugee-background students in Australian schools and universities. Intercult. Educ. 26, 210–217. doi: 10.1080/14675986.2015.1048079

Nassaji, H. (2015). The Interactional Feedback Dimension in Instructed Second Language Learning: Linking Theory, Research, and Practice. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Nassaji, H., and Geva, E. (1999). The contribution of phonological and orthographic processing skills to adult ESL reading: Evidence from native speakers of Farsi. Appl. Psycholing. 20, 241–267. doi: 10.1017/S0142716499002040

Pasquarella, A., Gottardo, A., and Grant, A. (2012). Comparing factors related to reading comprehension in adolescents who speak english as a first (L1) or second (L2) language. Scient. Stud. Read. 16, 475–503. doi: 10.1080/10888438.2011.593066

Phillimore, J. (2011). Refugees, acculturation strategies, stress and integration. J. Soc. Policy 40, 575–593. doi: 10.1017/S0047279410000929

Proctor, C. P., Silverman, R. D., Harring, J. R., and Montecillo, C. (2012). The role of vocabulary depth in predicting reading comprehension among English monolingual and Spanish–English bilingual children in elementary school. Read. Writ. 25, 1635–1664. doi: 10.1007/s11145-011-9336-5

Rashtchi, M., Zokaee, Z., Ghaffarinejad, A. R., and Sadeghi, M. M. (2012). Depression. Does it affect the comprehension of receptive skills? Neurosci. J. 17, 236–240. Available online at: http://nsj.org.sa/content/17/3/236.abstract

Refugees Citizenship Canada. (2019). Family Class: The Application Process. Available online at: https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/corporate/publications-manuals/operational-bulletins-manuals/permanent-residence/non-economic-classes/family-class-process.html (accessed June 27, 2023).

Rott, S. (1999). The effect of exposure frequency on intermediate language learners' incidental vocabulary acquisition and retention through reading. Stud. Second Lang. Acquisit. 21, 589–619. doi: 10.1017/S0272263199004039

Ryder, A. G., Alden, L., and Paulhus, D. L. (2000). Is acculturation unidimensional or bidimensional? A head-to-head comparison in the prediction of demographics, personality, self-identity, and adjustment. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 79, 49–65. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.79.1.49

Schumann, J. H. (1986). Research on the acculturation model for second language acquisition. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 7, 379–392. doi: 10.1080/01434632.1986.9994254

Sheikh, M., and Anderson, J. R. (2018). Acculturation patterns and education of refugees and asylum seekers: a systematic literature review. Learn. Individ. Differ. 67, 22–32. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2018.07.003

Statistics Canada (2016). 150 Years of Immigration in Canada. Avaailable online at: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11-630-x/11-630-x2016006-eng.htm (accessed January 30, 2023).

Statistics Canada (2017). Table 2 top 10 Countries of Birth of Recent Immigrants, Canada, 2016. Available online at: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/171025/t002b-eng.htm (accessed January 24, 2023).

Statistics Canada (2022). Canada's Population Estimates, Third Quarter 2022. Government of Canada. Available online at: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/221221/dq221221f-eng.htm (accessed April 20, 2023).

Thomson Reuters. (2018). Available online at: https://www.reuters.com/article/iran-english/iran-bans-english-in-primary-schools-after-leaders-warning-idINKBN1EW0L7?edition-redirect=in

Torgesen, J. K., Wagner, R. K., and Rashotte, C. A. (1999). TOWRE: Test of Word Reading Efficiency. Austin, TX: Pro-ed.

UNHCR (2021a). UNHCR Refugee Statistics (2021). Available online at: https://www.unhcr.ca/in-canada/refugee-statistics/ (accessed January 27, 2023).

UNHCR (2021b). UNHCRResettlement (2021). Available online at: https://www.unhcr.org/resettlement.html (accessed January 27, 2023).

Woodcock, R., McGrew, K., and Mather, N. (2001). Woodcock-Johnson III Tests of Achievement. Riverside Publishing.

Zane, N., and Mak, W. (2003). “Major approaches to the measurement of acculturation among ethnic minority populations: A content analysis and an alternative empirical strategy,” in Acculturation: Advances in Theory, Measurement, and Applied Research, eds K. M. Chun, P. B. Organista, and G. Marín (American Psychological Association), 39–60. doi: 10.1037/10472-005

Keywords: second language literacy development, second language (L2) acquisition, acculturation, immigration, refugees, social adjustment, English as a second language (ESL)

Citation: Jasemi A and Gottardo A (2023) Second language acquisition and acculturation: similarities and differences between immigrants and refugees. Front. Commun. 8:1159026. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2023.1159026

Received: 05 February 2023; Accepted: 21 June 2023;

Published: 13 July 2023.

Edited by:

Guillaume Thierry, Bangor University, United KingdomReviewed by:

Katarzyna Jankowiak, Adam Mickiewicz University, PolandCopyright © 2023 Jasemi and Gottardo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ali Jasemi, YWphc2VtaUB3bHUuY2E=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.