94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Commun., 30 October 2023

Sec. Health Communication

Volume 8 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2023.1154297

This article is part of the Research TopicThe Creation and Impact of Visual Narratives for Science and Health CommunicationView all 9 articles

Objective: The goal of this study was to evaluate the impact of a visual social media health campaign. The #1in10 campaign was co-created by the Danish Endometriosis Patient Association and women with endometriosis.

Methods: Seven semi-structured interviews were conducted with campaign participants to evaluate their experience of participating. The interviews were then analyzed thematically. Social media metrics on the reach of the campaign were gathered to assess how the campaign had performed.

Results: Seven themes were identified in the interviews: (1) Taboo, (2) Visibility, (3) Awareness, (4) Acknowledgment, (5) Empowerment, (6) Patient Experts, and (7) Community. Throughout the interviews, the women conveyed that they found their participation in the campaign meaningful, as it contributed to creating awareness and recognition of a disease otherwise surrounded by taboo and stigma. Social media metrics show how the #1in10 campaign reached both people inside and outside the endometriosis community. Across the FEMaLe Project's three social media platforms, 208 (51.5%) of engagements were with patients with endometriosis, 96 (23.7%) were with FEMaLe employees and advisers, 94 (23.3%) were with the general public, and 6 (1.5%) were with policymakers. In the month the #1in10 campaign was released, the FEMaLe Project's Twitter and Instagram accounts had more impressions than almost any other month that year (except January on Twitter and November on Instagram). The FEMaLe Project's LinkedIn had the same number of impressions as in other months.

Discussion: The study shows that the #1in10 social media campaign had an impact on three levels: on an individual level for the participating patients, on a communal level for people with endometriosis, and on a wider societal level. The participating patients felt empowered by their involvement with the campaign and the act of coming forward. The participants acted on behalf of their community of people with endometriosis, in the hopes that it would raise awareness and acknowledgment. In return, the community engaged with the campaign and added significantly to the dissemination of its message. On a societal level the campaign has caught particular attention and engagement compared to other posts made on the same social media accounts.

Social media constitutes a unique arena, where everyone with internet access can easily find, generate, and share content with the world. For many users, it is a common place to seek out information (Chen and Wang, 2021). On an individual level, social media can provide supportive spaces for like-minded people to engage with each other. Social media also facilitates the exchange of discourses and knowledge about potentially sensitive health issues (Zhang et al., 2017). However, the ease with which everybody can produce, and post, content can result in an overload of information of varying accuracy or even outright misinformation (Arena et al., 2022), creating what is referred to as an infodemic (King and Lazard, 2020). The inherent risk of misinformation makes it difficult to assess the validity of the content on social media (Arena et al., 2022).

Despite these identified risks, social media continues to be an important sphere for healthcare communication and an ideal place for activist agendas within the health domain (Rus and Cameron, 2016; Stellefson et al., 2020; Urban and Holtzman, 2023). It is often utilized by health organizations to raise awareness, promote actions, address health problems, or advocate for change in public policies related to health issues (Fu and Zhang, 2019; Tomlinson, 2023).

An example of this is the endometriosis social media health campaign (#1in10 campaign) by the Danish Endometriosis Patient Association (DEPA). Endometriosis is a chronic systemic disease in which tissue similar to the lining of the uterus grows outside of the uterus, typically in the abdominal cavity causing, bleeding, inflammation, adhesions, and scar tissue (Zondervan et al., 2020; Taylor et al., 2021). Endometriosis is estimated to affect one in ten women of reproductive age and an unspecified number of transgender, genderfluid, and non-binary people globally (Holowka, 2022). There is, however, still a lack of awareness around this condition, which is accompanied by severe underfunding for research and innovation as well as very few available treatment options (Ellis et al., 2022). The most common symptom of endometriosis is pain, e.g., chronic pelvic pain or pain related to menstruation (Zondervan et al., 2020). Since the bodily sensation of pain is inherently difficult to communicate to people who do not experience similar pain sensations, endometriosis is a predominantly invisible disease (Whelan, 2003). Furthermore, endometriosis is a relatively unknown disease. This lack of awareness, combined with stigma and taboo associated with menstrual health, contribute to an average world-wide diagnostic delay of 7 years (Zondervan et al., 2020).

In the summer of 2021, DEPA launched the first series of the #1in10 campaign on Facebook and Instagram. The campaign was led by a Danish journalist, who was herself a patient with endometriosis. It was designed as an informational campaign to convey the struggles of living with endometriosis. In the creation of the #1in10 campaign, DEPA reached out to their members with endometriosis to engage them in a co-creation process. They were asked to submit a photograph of themselves and formulate a question based on their own experiences with endometriosis. Questions included: “Why must I live in constant pain?” or “Why is my disease not being taken seriously?” Each social media post then consisted of one photograph, the name and age of the woman in the photograph, and her question (Figure 1). Following the first release of the campaign in 2021, a second series was released later that year, with a total of 25 different patient submissions being posted.

In 2022 the EU-funded Horizon 2020 research and innovation project Finding Endometriosis using Machine Learning (FEMaLe, Grant No. 101017562) entered a collaboration with DEPA to translate 15 of the patient questions into English and visually redesign the campaign to fit FEMaLe's visual identity and guidelines for co-branding (Figure 2). It was then promoted through FEMaLe's social media accounts on Instagram, Twitter, and LinkedIn, as part of the worldwide endometriosis awareness month of March 2022.

Several of the questions in the #1in10 campaign revolve around the patients' struggles with pain. Pain should be understood in accordance with the newest definition by The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP): “An unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with, or resembling that associated with, actual or potential tissue damage” (Raja et al., 2020, p. 2). They add that pain is always a personal experience. Likewise, in a study of endometriosis, Whelan states: “Pain is ineffable and elusive; it confounds the grasp of language and objectification. As an experience, pain is utterly private and subjective, and, consequently, it creates a divide between sufferer and observer” (Whelan, 2003, p. 464).

In contrast to the IASP definition, the health care system often approaches pain from a biomedical point of view (De Ruddere and Craig, 2016; Ilschner et al., 2022). This view posits that pain needs to be proven “objectively” through psychical findings to be valid (Atkinson, 1988). Health care professionals often use the Numeric Rating Scale as a tool to “measure” pain for which patients are asked to classify their pain on a scale from 0 to 10 (Bourdel et al., 2014). This is an attempt to objectify the otherwise subjective and intangible experience of pain. However, studies show that health care professionals tend to score the patients' pain lower than the patients do themselves (Ruben et al., 2018), which supports the claim that pain is always subjective and cannot be objectified (Raja et al., 2020). The patient's pain assessment is not always deemed as valid (Hintz, 2022; Ilschner et al., 2022). Indeed, health care professionals tend to believe that patients exaggerate their claims to pain when there are no correlating physical findings (Hintz, 2022; Ilschner et al., 2022). This is a particular problem for people with endometriosis, because the extent of pathology and pain experiences rarely match (Zondervan et al., 2020). On top of this problem of communicating and validating pain, people with endometriosis face the challenge that pain related to menstruation is commonly seen as “normal,” “harmless,” and not worthy of further attention or treatment (Seear, 2009). As a result, people with endometriosis can feel neglected or even mistreated (Whelan, 2007; Hudelist et al., 2012).

Visual tools are especially good for communicating such complex and intangible concepts as pain as well as creating attention and engagement. Therefore, visualizations are used more and more in health communication campaigns, such as the #1in10 campaign (Cluley et al., 2021; Jarreau et al., 2021). Visual communication takes several forms, but the visual format used in health communication is often story driven and humanized. This can foster empathy and make the intangible suffering of others relatable (Ali and Rogers, 2022; Bartel, 2022). The use of visuals has long served as a method in qualitative research to explore the everyday life of different groups of people, including illness experiences (Hussain, 2022). Photo-elicitation allows patients to control how they present themselves and their experiences (Frith and Harcourt, 2007), as was done when the participants were asked to photograph themselves, as co-creators of the #1in10 campaign. The campaign can be understood as co-created in the widest sense, as two or more people took part in the creative process of designing the campaign (Sanders and Stappers, 2008). The participating women were involved in the creation of the content of the campaign and thereby the expression and message of the campaign. Co-creation may provide the patients with a sense of agency and move them away from the passive sick role (Paulovich, 2015). Since they have a unique insight into living with a disease, co-creating a health communication campaign with patients ensures sustainability of the campaign, the relevance of the campaign to the issues facing their community, and enhance the likelihood of meaningful impact (Lefebvre et al., 2020).

There is a general underlying assumption that utilizing social media for health promotion effectively increases the likelihood that audiences will consequently take action (Freeman et al., 2015; Chen and Wang, 2021). To evaluate engagement with audiences using social media, three levels can be operationalized, as suggested by Neiger et al. (2012):

(1) Low engagement—users prefer content, e.g., a “like” on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, or LinkedIn.

(2) Medium engagement—users share content to influence others, e.g., retweeting on Twitter, reposting on Linkedin, etc.

(3) High engagement—users act or participate in offline interventions upon being exposed to social media campaign posts, e.g., donate money, etc.

However, it takes limited effort to engage with a campaign on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram or LinkedIn, and no direct link between the amount of likes' and the likelihood of behavior change has been proven (Freeman et al., 2015). This phenomenon, known as “slacktivism,” illustrates that there is often a disconnect between awareness and offline action (Glenn, 2015). Furthermore, social media has even been criticized for lowering the level of commitment and activity critical for any given campaign's success (Freeman et al., 2015).

Considering these contrasting perspectives on the potential of social media to engender positive health outcomes, Chen and Wang (2021) have identified a need for further research regarding the evaluation of impact when using social media in health interventions. Therefore, by assessing the co-created #1in10 campaign, based on visual communication, the aim of the current study is to examine how a social media health campaign creates impact.

A mix of qualitative and quantitative methods were used to examine the impact of the campaign.

A qualitative approach of individual semi-structured interviews, was chosen to assess the impact of the #1in10 campaign for the participants.

The 15 women, who contributed to the English version of the #1in10 campaign, were initially invited by DEPA on behalf of the researchers to participate. Researchers then sent out an informed consent form regarding participation by e-mail to interested participants. Only after having received a signed copy of the informed consent form, a time and date for the interview was agreed. All 15 women responded positively to the request of an interview, but only seven returned the signed consent form and participated in the study. The seven interviews were held during November and December 2022. They were conducted virtually via an online video connection (Zoom) and lasted between 35 and 70 min each. With the consent of the participants, interviews were video and audio recorded. The interviews were conducted by two independent researchers (DS, IH). As Danish was the native language of both interviewers and interviewees, the interviews were conducted in Danish.

At the time of the interview, participants were between 21 and 49 years of age and had all been diagnosed with endometriosis, though some had been living with the diagnosis for more than 20 years, while others had only recently been diagnosed. All participating women had experienced several years of diagnostic delay ranging from two to 17 years from onset of symptoms to diagnosis. Details concerning demographics and endometriosis history of the participants are found in Table 1.

There were three parts to the interviews. The first part of the interviews was phrased as a questionnaire asking basic demographical questions about the women's age, family situation, occupation, etc., with very little room for deviation. The second and third parts of the interviews were conducted as semi-structured interviews. Some questions were asked to explore certain assumptions about the impact of the campaign. The interviews also included several open-ended questions, which offered participants the space to direct the interviews in the manner that made the most sense for them. This space for improvisation allowed interviewers and participants to pursue any new and exciting themes that might occur (Franks, 2002). In the second part, participants were asked about their experiences with endometriosis; their symptomatic history, their diagnostic journey, and their current condition and quality of life. The third part was focused specifically on the campaign and their personal experiences, thoughts, worries, and hopes before, during, and following, the release of the campaign (Appendix 1).

The interview recordings were transcribed using an online automated transcriber (transkriptor.com). As automated transcribers are generally still very insufficient when it comes to transcribing the Danish language, it was necessary to manually revise all the transcriptions. The Danish transcripts were then subjected to thematic analysis, using an inductive/deductive hybrid approach, as described by Fereday and Muir-Cochrane (2006). This approach followed 6 steps of analysis. In the present analysis, steps 2 and 3 were merged. The approach is presented as a step-by-step procedure, although the analysis was an iterative process.

Step 1. Based on the interview guide, an a priori template for the codebook was developed (Figure 3).

Step 2 and 3. Researchers familiarized themselves with the transcripts. The codebook was tested and verified by applying the codes to two of the transcribed interviews. Some of the codes were given new names, and new codes were added to the codebook.

Step 4. The transcripts were uploaded to QSR Nvivo 12 (2022), and the codes were matched with segments of data deemed representative. Multiple codes could be matched with the same segment. This stage was guided, but not confined, by the preliminary codes. During the coding of transcripts, inductive codes were assigned to segments of data that described a new theme observed in the text.

Step 5. Codes were connected as themes and patterns in the transcripts were generated.

Step 6. Themes were further clustered and previous stages were closely scrutinized to ensure that the generated themes were representative of the initial codes. This process involved several iterations, before the final analytical themes were agreed.

For further details on the process see Figure 3.

A quantitative approach was chosen to assess the impact of both the Danish and the following joint English #1in10 campaign(s).

Data were determined using Facebook and Instagram “Insights” as well as LinkedIn and Twitter “Analytics,” both of which provide aggregated information about user interactions. Each social media platform provides different metrics, which is why data were recorded separately. The definitions of the various social media metrics are provided in Table 2. Metrics for the 37 Facebook posts and 35 Instagram posts in Danish were collected on December 16, 2022. Metrics for the 3 LinkedIn posts, the 15 Instagram posts, and the 14 Twitter posts in English were collected on December 23, 2022.

Neiger et al. (2012) proposed stratifying social media engagement into three levels. As previously mentioned, however, the third level that Neiger et al. (2012) suggests is difficult to measure because there is no direct link between engagement on social media and offline interventions. Furthermore, due to the algorithms in use on the different social media platforms, a “like” may have the same effect as a “re-post,” when it comes to advancing exposure. Therefore, in the present study engagement was stratified into two levels in line with Freeman et al. (2015): those with low level of online engagement (those passively following content without further interaction, i.e., “lurking”), and those with high level of engagement (those interacting with social media campaign materials such as “liking” and posting original content). In addition, the highly engaged online audience of the English #1in10 campaign were identified and categorized into four groups: “patients,” “FEMaLe staff and advisers,” “general public,” and “policymakers.” This was done manually by identifying each person and categorizing them based on information available on their social media accounts.

Descriptive statistics for each post, e.g., likes, impressions, discovery, and reach, as well as mean and standard deviations per platform were determined using Microsoft Excel version 16.68 (2022).

The study was pre-registered at the Danish Data Protection Agency through Aarhus University's internal registration (journal number: 2016-051-000001, running number: 2854). The participants signed a consent form informing them of the possibility of withdrawal and confidentiality. The consent form was provided by Aarhus University and was aligned with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) that has been implemented in the European Union (The European Parliament The Council of the European Union., 2016; Danish Ministry of Justice, 2018).

In keeping with the spirit of the campaign, participants' real names were used when referring directly to a specific person. It was deemed impossible to ensure complete anonymity, as only 15 women participated in the English version of the campaign, which makes it easy to identify any of them. As it is common procedure to anonymize all informants in qualitative studies like this, and if necessary, even change information such as age and gender, all participants consented specifically to the use of their name and age in this study.

In an effort to represent the participants as faithfully and respectfully as possible, all the quotes included in this article were translated from Danish into English to the best of the authors' ability. As the main priority was to preserve the substance and message of the quote, a direct translation was not always achievable.

Most of the seven participants describe how they faced challenges in getting diagnosed with endometriosis either because of misdiagnosis or because their symptoms were dismissed when seeking medical assistance. For example, one of the women, Linda aged 47, visited her general practitioner with severe menstrual pain, when she was 14 years old and was told: “Well, it hurts to be a woman.”

Every woman was affected differently by endometriosis in her everyday life. Nevertheless, all women experienced some sort of pain or fatigue either as a result of the disease or because of side effects from the prescribed medicines which they have been taking many years. All women described their quality of life as more or less reduced compared to not having to live with endometriosis.

The thematic analysis resulted in seven overall themes emerging from the interviews: (1) Taboo, (2) Visibility, (3) Awareness, (4) Acknowledgment, (5) Empowerment, (6) Patient Experts, and (7) Community.

Many of the women felt the need to hide their daily struggles with endometriosis in order to maintain a “normal” life. Ida reflected on this point:

“I'm not the kind of person who complains all the time and needs attention. Often, I have kept quiet when I have felt truly awful, because I didn't want others to see. I don't know why I think like that. If someone else got migraines or diabetes, people would know that they would be sick from time to time and not find it strange. But if you never let on that you are sick and you are frequently unwell, then it is invisible. I feel like it is in some ways my own fault, that it remains invisible, because I always put on a smile.”

Similarly, Linda talked about how she once tried to keep quiet about her endometriosis because of embarrassment and modesty. Several women mentioned how endometriosis is difficult to talk about, because it is tightly connected to menstrual health, which is a subject that is often surrounded by taboo, stigma, and shame. However, Linda came to realize that she not only wanted to, but also felt compelled to, overcome this embarrassment so that she neither contributed to the taboo nor the invisibility of the disease:

“No, I do not want to uphold the shame of it. What if my children get it?”

Both Linda and Ida expressed a wish to break their silence to make the disease more visible.

When they first joined the campaign, some of the women had to overcome some initial concerns with regards to engaging in open communication about such an intimate part of their lives. To Anne, it felt slightly like being exposed:

“It's obviously very personal. It's not just a new profile picture.”

Anne said this was not necessarily a bad feeling, but she was very aware of the intimate nature of what she shared.

The feeling of being exposed was reflected in comments the women received from friends and family after the campaign was released. Christina said:

“They said it was really cool to come forward with my picture […] that I had the courage to do so. Many people actually considered this to be quite brave.”

Throughout all the interviews, it was frequently clear that endometriosis and menstrual health in general could be a sensitive topic.

Most women felt that their disease was made less legitimate, because people could not see any visible signs. Sofie observed that, before she underwent surgery and had visible scars to show, people did not recognize how serious and debilitating endometriosis could be. The scars made her condition tangible. Anne learned, that before they saw the campaign, people at her job did not know she was sick, even though her pain and fatigue made it impossible for her to work full time. Christina said that it would be easier to make people understand and recognize her situation if she had a broken leg and a cast. Linda's experience of her disease being disregarded was a main motivational factor for her to participate in the campaign:

“I want to show young people, women in general, that they are being taken seriously [when they experience endometriosis symptoms]. Because many of us were simply dismissed.”

Although it might seem “scary” (Sofie) to share one's personal medical history through publicly posting name, age and picture, the women found this aspect of the campaign important, and no one had any doubts about committing to doing so. Kirsten said:

“Definitely, I found it meaningful to participate. Because I can help provide a face, a picture to make visible that there is something important, that needs more attention out there.”

Several women thought that the campaign was made stronger and more effective by using their pictures and names, because it made the invisible sensations of pain evident. Ida said:

“I think it makes a huge difference to see another human—a face. It is easier to sympathize. […] I think I remember some of the other women from the campaign, because I can recollect their faces. When I first saw it and then read the question, I thought to myself: wow, you can see, how much this affects her.”

When something is made visible, it is much easier to understand, relate to and even manage. For Anne, being able to see the physical effects of endometriosis was very important for her ability to cope with it:

“I was allowed to see recordings of some of my own operations. I needed that; I still do. It is important for my learning to cope with the situation and understand, okay, that is not how it is supposed to look, something is wrong inside me. It is not just something in my head, there really is something wrong with me.”

By posting visuals that clearly show the struggles and possible consequences of having endometriosis, these women were able to challenge common misconceptions, like the belief that endometriosis is “just a bad period,” Linda said. Prior to participating in the campaign, some of the women used their personal Facebook or Instagram account to visually share their experiences with endometriosis. Linda had previously posted a picture of her temporary ostomy on Instagram, which she received following surgery related to endometriosis. For some women, participating in the campaign was their first time visually coming forward with their own endometriosis experiences on social media. The women shared the hope that making the disease visible would lead to more awareness.

Several women stated that this awareness was especially important for the sake of the next generation of people with endometriosis. Linda said:

“Every time someone hears the word ‘endometriosis' they might at some point in the future recognize the symptoms, and maybe someone will be diagnosed a little sooner.”

Anne expressed a similar sentiment. Even though she did not expect to obtain better treatment for herself, she still found the fight for more awareness to be essential. She said:

“More awareness can hopefully lead to more and better treatments. It is too late for me, but the women who are born today, who will experience the first symptoms in around 13 years, it is for them that I do it.”

In this quote, Anne indicated that her desire to help the next generation derived from her own difficult diagnostic journey and subsequent treatment. Christina also highlighted her own bad experience with the health care system as her main motivation for participating and fighting actively for better treatments in the future. She felt like she has been a “guinea pig” throughout her treatment, and she further said:

“I have experienced going to my doctor and being viewed as psychologically unstable, because I have an illness that you can't necessarily see. I would like to change that perception of women.”

The women thus wanted to create more awareness to make it easier for lay people, as well as health care professionals, to recognize the symptoms of endometriosis and thereby reach a diagnosis earlier.

The women predominantly received reactions from friends and family either in-person or on social media regarding their participation in the campaign. All the reactions were positive. Some people told them they were “brave” or “cool” for coming forward, or people showed their empathy and willingness to learn more. Anne described this as “an acknowledging pat on the back,” which made her feel seen and grateful. Sofie also pointed out that, regardless of how vulnerable it might make one feel, coming forward was needed in order to receive support and generate recognition.

Though many women described how they had already learned to cope with endometriosis and accepted living with the disease prior to participating in the campaign, they expressed that the mere existence of the campaign, as well as their participation in it, had a significant impact for them. Kirsten said:

“I have always willingly talked about my condition with endometriosis if people asked […] But participating in this campaign knowing someone kickstarted it to create attention makes me feel more… I was about to say justified, when I talk about it. It isn't something I need to keep a secret or talk about embarrassingly in short sentences […] A campaign like this makes me feel like there is something backing it up and acknowledging it. More than there was before, for sure.”

Kirsten addressed how contributing to creating awareness through participating in the campaign gave her a sense of validation.

Ida said that the increased focus and emphasis on endometriosis that was engendered by the realization, and subsequent evaluation, of the #1in10 campaign (alongside her own engagement with endometriosis accounts on Instagram) enabled her to “stand taller” when telling people about the challenges that endometriosis poses in her everyday life. She stated that it should not be like this, but her experience was that this increased focus made people take it more seriously. Christina had the same realization some years ago. Contributing to increasing awareness of endometriosis was important for her personal growth and her ability to live a full life with endometriosis. On her participation in the #1in10 campaign, she said:

“[…] The invisible is made visible […] I think showing the other side of the coin maybe just makes you feel more whole. I think many of my friends, also my close friends, have gotten a different insight into me and my life. They experienced me as energetic and well-functioning, which might be because I had to compensate for the bad days. So, I think they have gotten the whole Christina.”

The existence of the #1in10 campaign and the supportive reactions from people who had seen it, gave the participating women a sense of empowerment.

Sofie pointed out that the #1in10 campaign was made more impactful because the content was co-produced with patients:

“[…] It makes it more personal. You get the subjective experience instead of just facts about what it is and how it can affect the body. How is it really for those who actually live with it? How is it experienced? I think it makes it more tangible for the ones who don't live with it.”

The women believed that their subjective experiences provided them with important expertise on endometriosis. This sense of being experts was strengthened by the fact that the women frequently had to advocate for themselves and act as their own doctor, even though they did not always feel qualified to do so. Hanne said:

“When I go to the doctor and say that I am tired, they can't do anything for me. So, I had to figure out for myself what I could do to get more energy.”

Kirsten traveled to Romania to undergo surgery that she could not access in Denmark:

“I find it scary to think that they would have put me on public benefits instead of looking for a method to help me, which I then found myself.”

The women felt these experiences were the result of a general lack of knowledge about endometriosis, limited treatment options, and the need for more health care protocols on how to handle symptoms of endometriosis before and after diagnosis. As patients, the women had a bodily knowledge of endometriosis, which they felt made them uniquely capable of producing more knowledge on the subject, hopefully fostering better treatment options and health care protocols in the future. Their bodily knowledge was yet another reason behind their belief that the #1in10 campaign was strengthened by their willingness to share their experiences openly and honestly.

Several women mentioned how their shared bodily knowledge of the struggles with endometrioses made them understand each other in a way that nobody else did. Christina said:

“When you are with your girlfriends…They can't relate to all the challenges you have had throughout life. Then it feels good to be able to recognize yourself in someone else who have either gone through the same things or are going through the same, right?”

Hanne likewise stated:

“I have been to an endometriosis lecture, where a person said, that we all know how much it can hurt to fart. I found that funny, because no one else knows. It really hurts.”

To experience this acceptance from others with the same struggles was very important for many of the women. Especially when participating in the #1in10 campaign, they found it comforting to know that it was a shared endeavor in which many other people with endometriosis participated. Sofie stated that this was crucial for her, when agreeing to participate, and she said that it made her feel less exposed. Ida likewise said that it was a nice feeling to stand “shoulder by shoulder” in the #1in10 campaign. She felt that the participation of several women in different age groups and with different backgrounds would support the message that endometriosis is something that needs to be taken seriously. Ida said:

“You get sad to see how many women who struggle with this and say the same things as you, because when you have experienced it on your own body you know what it entails. So, it always hurts seeing a face saying: ‘I feel like this…' But in a way it also makes it easier to handle, as you know you are not the only one feeling like this.”

Prior to the #1in10 campaign, all women were in some way engaged in endometriosis patient communities with most of them being active on social media. There are several Danish language endometriosis patient communities on Facebook; one of them is DEPA's account. It varied among the women how active they were in such groups and on such platforms. However, they expressed that they tended to use these platforms primarily for seeking advice from people with similar experiences or giving others advice. Some of the women followed endometriosis accounts on Instagram, either individual people, who share their experiences, or organizations that share facts and relatable content. The women expressed that patient communities, either physical or online, gave them the opportunity to find themselves reflected in someone else and gain understanding.

Most of the women talked about feeling gratitude toward all the women who came before them, and who have previously been fighting for awareness and recognition. Anne said:

“I wanted to give my support. I was so grateful to all the others who had the energy to fight for more awareness. I wanted to help. Because we [as a community] depend upon this effort. It is necessary if we want things to change. Someone must lead the way, and I wanted to go along and contribute with whatever I can. It is important.”

Hanne similarly stated:

“I thought it was nice that I could contribute. Those in the patient association work hard for us. If I could give just a little bit back, I wanted to do so.”

This wish to repay the kindness of previous endometriosis patients by fighting for better treatment for future patients, was a common motivational factor for participating in the campaign.

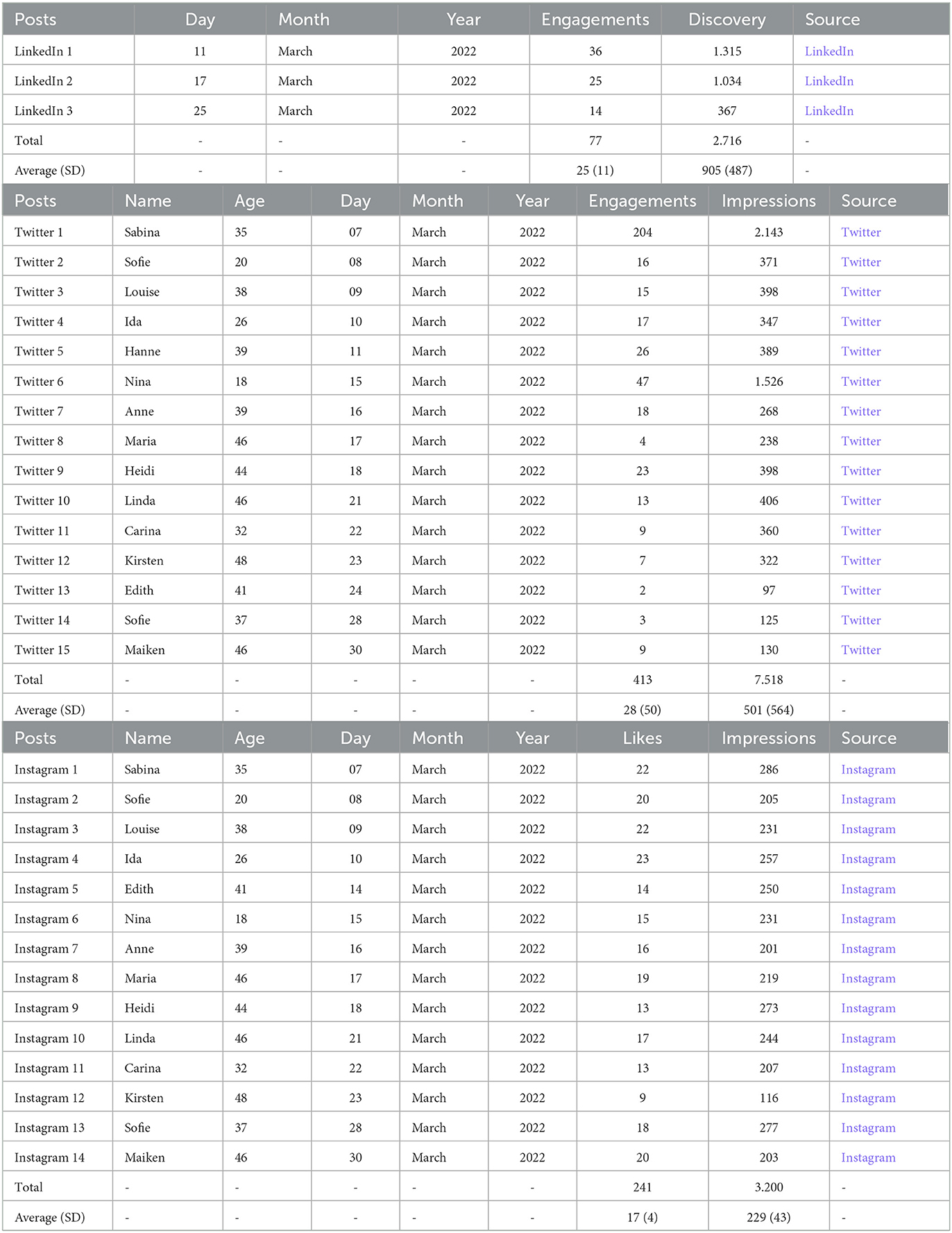

Analyses of social media metrics for the different posts are shown in Tables 3–5.

Table 5. Metrics of the #1in10 endometriosis social media posts by FEMaLe Project's LinkedIn, Twitter, and Instagram (in English).

The focus of the Danish #1in10 campaign in autumn 2021 was on Facebook and Instagram where DEPA had the largest social media following.

In total, 37 #1in10 posts were shared on DEPA's Facebook page; 23 in the first posting round (62%) and 14 in the second (38%). The campaign had a total Facebook reach of 161.279. In the first Facebook posting round, it had a reach of 130.275 (80.8%), followed by 31.004 (19.2%) in the second round. The campaign on Facebook received a total of 2.752 likes; 2.209 in the first round (80.3%) and 543 in the second (19.7%). The mean reach of the featured Facebook posts in the first round (Mean = 5.664; SD = 2.417) was more than two and a half times higher than in the second (Mean = 2.215; SD = 965), which is in line with the mean number of likes on Facebook in the first round (Mean = 96; SD = 42) was almost two and a half times higher than in the second (Mean = 39, SD = 14).

Instagram campaign performance using social media metrics differed from Facebook data. In total, 35 #1in10 posts were shared through DEPA's Instagram account; 23 (66%) in the first posting round and 12 (34%) in the second. The campaign left a total of 46.044 impressions; 31.024 (67.4%) in the first posting round and 15.020 (32.6%) in the second. The campaign received a total of 2.037 likes on Instagram; 1.521 (74.7%) in the first round and 516 (25.3%) in the second. The mean impressions of the featured Instagram posts in the first round (Mean = 1.349; SD = 303) was close to the second (Mean = 1.252; SD = 183), while the mean likes in the first round (Mean = 64; SD = 20) was notably higher than in the second (Mean = 47, SD = 9).

The mean reach per post was more than three times higher on Facebook (Mean = 4.358) than Instagram (Mean = 1.315), the mean engagements per post on Facebook (Mean = 74) was closer to Instagram (Mean = 58).

During Endometriosis Awareness Month in March 2022, the focus of the English #1in10 campaign was on Twitter, Instagram, and LinkedIn (as the FEMaLe Project has the largest social media following on these platforms).

In total, 3 #1in10 posts were shared through the FEMaLe Project's LinkedIn profile. The campaign had a total discovery of 2.716, and the posts received a total of 77 engagements. Each of the featured LinkedIn posts had a mean discovery of 905 (SD = 487) and a mean engagement of 25 (SD = 11). A total of 15 #1in10 Tweets were posted via the FEMaLe Project's Twitter account. The campaign left a total of 7.518 impressions, and the posts received a total of 413 engagements. Statistics revealed a mean impression of 501 (SD = 564) and a mean engagement of 28 (SD = 50) of each of the featured Tweets. Furthermore, a total of 14 #1in10 posts were shared through the FEMaLe Project's Instagram profile. The campaign left a total of 3.200 impressions, and the posts received a total of 241 engagements. Statistics revealed a mean impression of 229 (SD = 43) and a mean engagement of 17 (SD = 4) of the featured Instagram posts. The mean reach per post was highest on LinkedIn, followed by Twitter, and Instagram, while the mean engagement per post was highest on Twitter, closely followed by LinkedIn, and Instagram.

The #1in10 posts received a total of 404 likes across all social media platforms. LinkedIn created 77 engagements, out of which 70 (91%) were likes—and the rest either comments or reposts, Twitter performed a total of 413 engagements, out of which 93 (23%) were likes—and the rest either retweets or replies, and Instagram contributed with a total of 241 likes. Instagram was the most successful social media platform with regards to securing high level of online engagement, when measured by the number of likes (60%), followed by Twitter (23%), and LinkedIn (17%).

As seen in Table 6, engagements across the social media platforms were sorted into four categories: (1) community members, (2) FEMaLe Project staff, incl. advisers, (3) the general public, and (4) policymakers. Across all platforms the English #1in10 campaign engaged patients with endometriosis the most (N = 208, 51.5%), followed by FEMaLers (N = 96, 23.7%) and the general public (N = 94, 23.3%), and, to a modest degree, policymakers (N = 6, 1.5%). Members of the community were primarily engaging with Tweets and Instagram posts, while FEMaLers and the general public interacted with LinkedIn posts, whereas policymakers engaged with LinkedIn posts and Tweets.

Social media metrics for the FEMaLe Project's LinkedIn, Twitter, and Instagram accounts in 2022 are shown in Table 7. The FEMaLe Project's Twitter data show how the 15 campaign Tweets, an integral part of the 35 total Tweets in March, contributed to leaving the second most impressions of all months in 2022. Similarly, Instagram data reveals how the 14 campaign posts, the majority of the 20 total posts in March, contributed to stimulating engagements from followers and leaving the second most impressions of all months in 2022, only succeeded by November. The three #1in10 posts on LinkedIn in March did not perform differently compared to posts in the other months.

The #1in10 campaign has created various kinds of impact on three different levels: individual, communal, and societal.

For participating patients, the act of coming forward created a space for more dialogue, which is otherwise challenged by the taboos surrounding endometriosis. This validated their daily struggles and gave them a sense of empowerment. The participating patients felt that they belonged to a community of people with endometriosis which fostered support that is vital for their ability to cope with their disease. Coming forward was a form of activism on behalf of the community, which reinforced their sense of unity and solidarity with the community.

The #1in10 campaign reached many individuals, both within and outside the endometriosis community. Furthermore, the FEMaLe Project's social media metrics revealed that the campaign materials had better engagement compared to other types of posts. As such, the campaign has successfully reached and engaged society outside the endometriosis community.

Studies have highlighted the anonymous aspect of the internet as a factor of why different patient groups might benefit from social media use. It can work as a shield against stigma and disapproval which creates the opportunity for patients more truly to express themselves (Bargh et al., 2002; Naslund et al., 2016). On the contrary, this study has demonstrated how the act of coming forward, with name, age and picture, can give a sense of individual empowerment and validation. People with endometriosis may benefit from revealing their personal identity when participating in social media health campaigns, as it can be a tool to overcome normalization, stigmatization, and taboo (Bobel and Fahs, 2020; Tomlinson, 2021).

The women in this study expressed how coming forward in the campaign created an opportunity and an occasion to talk about their invisible disease and everyday struggles with people, who neither knew they had endometriosis nor how it really affected them. Some women stated how the campaign made it possible for them to answer questions and challenge misconceptions. Since they gained recognition and acknowledgment from participating in the campaign, the women felt empowered. Furthermore, the women expressed how seeing the other women in the campaign had an impact on their individual feeling of empowerment. It generated comfort to see the faces of other women in whom they could recognize their own experiences. This has also been examined in relation to other patient groups. In a study on eating disorders amongst boys and men, Bartel (2022) argued that seeing photographs of other boys and men with eating disorders could reduce their sense of isolation through fostering feelings of solidarity. Indeed, participants expressed that, because they found a concrete person to whom they could relate, this helped them to feel validated and break the taboo. Through these photographs, the boys and men were able to challenge the perception of eating disorders as only a “girl's illness” (Bartel, 2022). Similarly, the #1in10 campaign challenged the perception of endometriosis as “just a bad period.”

Participating in the campaign gave the women a sense of agency. Using photo-elicitation, the women themselves decided how they wanted to appear on their photograph and what message they wanted to convey. As Holowka (2022) argued, it is important to raise awareness of lived experiences, as such insights can help reveal the gaps in endometriosis care. In line with [Paulovich' (2015) argument], the current study showed how social media health communication campaigns can give voice to patients with endometriosis, thereby giving them feelings of control and ownership. On their road to diagnosis, the participants in this study begrudged the fact that they had been compelled to advocate for themselves in situations that they believed should not demand such self-reliance (such as when trying to persuade doctors of their pain).

However, as they willingly participated in the #1in10 campaign, they framed their advocacy as a form of agency rather than a burden. As they possessed crucial insights into living with endometriosis, the women were “experts by experience” (Bartel, 2022). Thanks to the campaign, they could use this position to educate and engender reflection both from people inside and outside health care settings (Bartel, 2022). Furthermore, as Lorenz (2015) argued, seeing experience through the eyes of those who suffer can be a way to generate empathy and understanding. The agency enabled the individual woman to “stand taller” (Ida). Some women, who had not previously publicly discussed their experiences of endometriosis, said that they would like to continue to contribute to the subject in this manner.

In a variety of ways, the participating women highlighted the significance of connecting with other people with endometriosis with whom they could identify, exchange experiences, and share information. This was especially important considering the lack of understanding or outright dismissal the participating patients regularly faced from others who did not have endometriosis, and therefore did not understand the severity of the condition. Since they had previously felt that they were alone in their in-depth understanding of what it means to live with debilitating pain or fatigue, several of the participants felt relief when they first connected with other people with endometriosis. This feeling of unity, which is based on shared bodily knowledge, denotes an inherent sense of community.

This “community” of people, who share the unique experience of living with endometriosis, is what Whelan (2007) calls an “epistemological community”: “a group which shares a body of knowledge and a set of standards and practices for developing and evaluating knowledge” (Whelan, 2007) She found that such a community generates reciprocal validation and social support for community members (Whelan, 2007). Studies have long shown that perceived social support has a positive effect on mental and physical wellbeing and is integral to people's ability to cope with disease (Jacobson, 1987; Uchino et al., 1996; Ribera and Hausmann-Muela, 2011). This echoes the relief that the women in the #1in10 campaign experienced when connecting with their epistemological community.

Many of the participating women felt immense gratitude toward those from the community who had previously come forward to talk openly about endometriosis and this encouraged them to want to come forward themselves. Many expressed a keen wish to promote awareness, knowledge, and support for the sake of the people who will be diagnosed with endometriosis in the future. This was their primary motivation for participating in the #1in10 campaign. Their hope was that future people with symptoms of endometriosis might be better equipped to recognize the symptoms and feel more able to advocate for themselves when needed and, as such, receive a diagnosis sooner. By participating in the #1in10 campaign, the women were thus engaging in activism on behalf of their epistemological community. This indicated that they felt a strong sense of belonging to the community, which fostered solidarity and reciprocal responsibility. Indeed, as a sense of solidarity with others has been shown to reduce menstrual stigma, activists in the wider menstrual health movement have underlined the importance of fostering solidarity among women and other people who menstruate (Fahs, 2016; Tomlinson, 2021).

The epistemological community can also be observed online, where community members form connections and gather into groups via social media. Several previous studies have shown how people with endometriosis frequently use social media for health purposes. On social media, people with endometriosis can find support and understanding as well as obtain new knowledge (Holowka, 2022; Metzler et al., 2022; Missmer et al., 2022; van den Haspel et al., 2022). Likewise, the patient participants of this study all used, or had used, social media to connect with other people with endometriosis as well as to share, or to find, more information.

The #1in10 campaign was yet another opportunity for the participants to share their personal experiences of endometriosis with other members of the community. In fact, more than half of the engagements with the #1in10 campaign (N = 208, 51.5%) came from people with endometriosis. Additionally, it allowed them to inform the general public of the often-debilitating nature of endometriosis. The fact that the #1in10 campaign was co-produced with identifiable members of the endometriosis community, and their accounts were legitimized by DEPA and the FEMaLe Project, helped to validate the shared information in the eyes of the general public.

Social media metrics showed how March 2022 in general, and the #1in10 campaign in particular, performed better in terms of achieving engagements than other 2022 posts made by the FEMaLe Project. This speaks to the overall success of the campaign in reaching an audience. The quantitative data showed that 48.5% (N = 196) of the engagements with the social media campaign were from people outside the epistemological community. Almost half of these (N = 96, 23.7%)were from FEMaLe Project staff and advisers; people already engaged with endometriosis in some way. However, the remaining half (N = 94, 23.3%) covered the general public and therefore this group was comprised of people who did not necessarily work with, or have any knowledge about, endometriosis.

The #1in10 campaign performed comparatively well on all social media platforms, as evident by the fact that it contributed to leaving the second most impressions on both the FEMaLe Project's Twitter and Instagram accounts in 2022. On Twitter, it was only exceeded by January in all probability because of the newsworthiness of the launch of the French national strategy to combat endometriosis. On Instagram it was only succeeded by November, because of a joint event with the Endometriosis UK charity (51.300 followers).

This campaign has caught particular attention and engagement. Previous studies of similar health campaigns have argued that co-creation and visual tools are essential in creating this attention and engagement. Co-creation ensures that the message is aligned with the interest of the patient group and that visual representations command attention and foster empathy (Lefebvre et al., 2020; Cluley et al., 2021; Jarreau et al., 2021; Ali and Rogers, 2022; Bartel, 2022). It can therefore be assumed that co-creation and the visual representations had a significant impact on the level of engagement achieved by the #1in10 campaign.

It appears that no long tradition for studying the impact of social media health campaigns exists and no strong precedence for a specific methodological approach is available. One of the strengths of this study is the mixed methods approach where (1) the use of qualitative methods allows for an examination of the participating women's subjective experiences of co-creating the #1in10 campaign and belonging to the epistemological community of people with endometriosis, and (2) the use of quantitative methods allows for an overview of the reach of the #1in10 campaign and how the community and the general public engaged with it. The use of a mixed methods approach is therefore crucial to examine the impact of the #1in10 campaign. Yet, each method also has strengths and limitations on its own.

The seven participants of this study constitute a demographically diverse group (Table 1), and their experiences of living with endometriosis are rather different. However, the participants are not representative of all people with endometriosis, as the study is affected by considerable sampling bias. Studies have shown that people who actively engage with patient communities on social media are those who are most affected by their disease (Josefsson, 2005; van den Haspel et al., 2022). As participants of this study are recruited through DEPA, it can be assumed that they are among the patients most affected by endometriosis. Additionally, 15 women initially expressed an interest in participating in the current study, but eight failed to return a signed consent form and were thus not interviewed. It is possible, albeit improbable, that they chose to withdraw from the interview, because they had a negative experience participating in the campaign. If this is the case, this is a perspective that is entirely overlooked in the analysis. That being said, it might also be that the potential interviewees forgot to return the consent form, did not have time to do the interview, or had a flare up of their symptoms, so they did not feel well enough to participate after all. Despite both known and potential sampling biases, the aim of the qualitative part of the study remains the same; to study a few particular women and their situated experiences. It has never been the goal to conclude anything general or universal about people with endometriosis.

Traditionally within research, social media metrics have been considered as mere indicators of use and visibility. More recently, they have been used to measure interaction and circulation across different online communities (Díaz-Faes et al., 2019), which is the case for the present study. Young et al. (2020) found that social media metrics summarizing aggregate activity allow for insights into the extent of engagement with campaign content that leave less room for human error than traditional ways of manually tallying metrics. Thus, the use of social media metrics can help researchers understand the degree to which a campaign is eliciting appropriate levels of participation. In this study the use of social media metrics adds to the traditional data collection and analysis, e.g., social media metrics enable the identification of the specific people, who engage with the #1in10 campaign content.

The social media metrics collected in this study are dependent on the networks already established and surrounding both DEPA's and the FEMaLE Project's social media accounts. This creates a sampling bias, as the existing followers of these accounts become the primary audience of the campaign, and their willingness to engage is vital for the dissemination. Neither DEPA nor the FEMaLe Project have paid for promotion of content.

As it takes limited effort to engage with a campaign on social media, online engagement is not tantamount to offline action. This study is therefore not able to suggest actual behavior or attitude changes based on social media metrics. Further studies on this topic might ideally include qualitative perspectives and experiences from the audience of the #1in10 campaign, such as members of the epistemological community as well as the general public, as they can provide a broader insight into how the campaign is received and acted upon. This could provide more knowledge about why people engage with the campaign, and whether the #1in10 campaign fulfills the participants' hopes for the campaign: to put endometriosis on the societal and political agenda and thereby increase awareness, attract more funding for research and innovations as well as establish better treatment options for all.

Combining qualitative and quantitative methods, this study has demonstrated that the #1in10 campaign had an impact on three different levels: individual, communal, and societal.

On an individual level the campaign fostered empowerment for the participating women, because they felt that their participation contributed to making their struggles visible, known, and acknowledged.

The participants took part in the campaign on behalf of their community of people with endometriosis, in the hopes that their acts of activism would benefit future members of the community. As 51.5% (N = 208) of the engagements with the campaign were made by members of the community, it is evident that the campaign resonated with the community. As such, the community was vital for both the creation and the dissemination of the campaign.

The #1in10 campaign performed comparatively well with regards to creating engagements on social media—not just within the community but also in the wider society. While this does not necessarily entail a change in attitude or behavior, it suggests that the co-created and visual nature of the campaign had an impact on the audience.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

DS, IH, KH, and UK coordinated the project, conceived and designed the study, and drafted the manuscript. DS, IH, and UK executed the study and obtained the data. All authors analyzed and interpreted the data, critically revised the manuscript, read and approved the final manuscript, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

This article is part of the project Finding Endometriosis using Machine Learning (FEMaLe), which has received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant no. 101017562). This work was also supported by the Leverhulme Trust under Grant ECF-2019-232.

Thank you to DEPA for helping with recruiting participants. Thank you to all the participants for making the time for an interview. This would not have been possible without your contribution.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2023.1154297/full#supplementary-material

Ali, P., and Rogers, M. (2022). “Use of personas and participative methods when researching with hard-to-reach groups” in Arts Based Health Care Research: A Multidisciplinary Perspective, ed. K. Hinsliff-Smith, J. McGarry and P. Ali (Cham: Springer), 41–50. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-94423-0_4

Arena, A., Espoti, E. D., Orsini, B., Verrelli, L., Rodondi, G., Lenzi, J., et al. (2022). The social media effect: the impact of fake news on women affected by endometriosis. A prospective observational study. Eur. J. Obstetr. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 274, 101–105. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2022.05.020

Atkinson, P. (1988). “Discourse, descriptions and diagnosis: reproducing normal medicine” in Biomedicine Examined. Culture, Illness and Healing, eds. M, Lock and D. Gorden (Alphen aan den Rijn: Kluwer Academic Publishers), 179–204. doi: 10.1007/978-94-009-2725-4_8

Bargh, J. A., McKenna, K. Y. A., and Fitzsimons, G. M. (2002). Can you see the real me? Activation and expression of the “true self” on the internet. J. Soc. Issu. 58, 33–48 doi: 10.1111/1540-4560.00247

Bartel, H. (2022). “A “girls” illness?” Using narratives of eating disorders in men and boys in healthcare education and research,” in Arts Based Health Care Research: A Multidisciplinary Perspective, ed. K. Hinsliff-Smith, J. McGarry and P. Ali (New York: Springer), 69–84. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-94423-0_6

Bobel, C., and Fahs, B. (2020). “The messy politics of menstrual activism,” in The Palgrave Handbook of Critical Menstruation Studies, ed. C. Bobel, I. Winkler, B. Fahs, K. A. Hasson, E. A. Kissling and T.A. Roberts, (Singapore: Palgrave), 1001–1018. doi: 10.1007/978-981-15-0614-7_71

Bourdel, N., Alves, J., Pickering, G., Ramilo, I., Roman, H., and Canis, M. (2014). Systematic review of endometriosis pain assessment: how to choose a scale? Hum. Reprod. Update 21, 136–52. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmu046

Chen, J, and Wang, Y. (2021). Social media use for health purposes: systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 23, e17917. doi: 10.2196/17917

Cluley, V., Bateman, N., and Radnor, Z. (2021). The use of visual images to convey complex messages in health settings: Stakeholder perspectives. Int. J. Healthc. Manag. 14, 1098–1106. doi: 10.1080/20479700.2020.1752983

Danish Ministry of Justice (2018). Lov om supplerende bestemmelser til forordning om beskyttelse af fysiske personer i forbindelse med behandling af personoplysninger og om fri udveksling af sådanne oplysninger (databeskyttelsesloven). Nr. 502. Available online at: https://www.retsinformation.dk/eli/lta/2018/502 (accessed January 03, 2023).

De Ruddere, L., and Craig, K. D. (2016). Understanding stigma and chronic pain: a-state-of-the-art review. Pain 157, 1607–1610. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000512

Díaz-Faes, A. A., Bowman, T. D., and Costas, R. (2019). Towards a second generation of ‘social media metrics': Characterizing Twitter communities of attention around science. PLoS ONE14, e0216408. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0216408

Ellis, K., Munro, D., and Clarke, J. (2022). Endometriosis is undervalued: a call to action. Front. Glob. Womens Health 10, 54. doi: 10.3389/fgwh.2022.902371

Fahs, B. (2016). Out for Blood: Essays on Menstruation and Resistance. New York: University of New York Press.

Fereday, J., and Muir-Cochrane, E. (2006). Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: a hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. Int. J. Qualit. Methods 5, 80–92. doi: 10.1177/160940690600500107

Franks, M. (2002). Feminisms and cross-ideological feminist social research: standpoint, situatedness and positionality – developing cross-ideological feminist research. J. Int. Women's Stud. 3, 38–50.

Freeman, B., Potente, S., Rock, V, and McIver, J. (2015). Social media campaigns that make a difference: what can public health learn from the corporate sector and other social change marketers? Public Health Res. Pract. 25, e2521517. doi: 10.17061/phrp2521517

Frith, H., and Harcourt, D. (2007). Using photographs to capture women's experiences of chemotherapy: reflecting on the method. Qualit. Health Res. 17, 1340–1350. doi: 10.1177/1049732307308949

Fu, J. S., and Zhang, R. (2019). NGOs' HIV/AIDS discourse on social media and websites: technology affordances and strategic communication across media platforms. Int. J. Commun. 13, 25.

Glenn, C. L. (2015). Activism or “slacktivism?”: digital media and organizing for social change. Commun. Teach. 29, 81–85. doi: 10.1080/17404622.2014.1003310

Hintz, E. A. (2022). “It's all in your head”: a meta-synthesis of qualitative research about disenfranchising talk experienced by female patients with chronic overlapping pain conditions. Health Commun. 38, 2501–2515. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2022.2081046

Holowka, E. M. (2022). Mediating pain: navigating endometriosis on social media. Front. Pain Res. 3, 889990. doi: 10.3389/fpain.2022.889990

Hudelist, G., Fritzer, N., Thomas, A., Niehues, C., Oppelt, P., Haas, D., et al. (2012). Diagnostic delay for endometriosis in austria and germany: causes and possible consequences. Hum. Reprod. 27, 3412–3416. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des316

Hussain, S. A. (2022). Sharing visual narratives of diabetes on social media and its effects on mental health. Healthcare 10, 1748. doi: 10.3390/healthcare10091748

Ilschner, S., Neeman, T., Parker, M., and Phillips, C. (2022). Communicating endometriosis pain in France and Australia: an interview study. Front. Glob. Womens Health 3, 765762. doi: 10.3389/fgwh.2022.765762

Jacobson, D. (1987). The cultural context of social support and support networks. Med. Anthropol. Quart. 1, 42–67. doi: 10.1525/maq.1987.1.1.02a00030

Jarreau, P. B., Su, L. Y.-F., Chiang, E. C.-L, Bennett, S. M., Zhang, J. S., et al. (2021). COVID issue: visual narratives about COVID-19 improve message accessibility, self-efficacy, and health precautions. Front. Commun. 6, 712658. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2021.712658

Josefsson, U. (2005). Coping with illness online: the case of patients” online communities. Inf. Soc. 21, 133–141. doi: 10.1080/01972240590925357

King, A. J., and Lazard, A. J. (2020). Advancing visual health communication research to improve infodemic response. Health Commun. 35, 1723–1728. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2020.1838094

Lefebvre, R. C., Chandler, R. K., Helme, C. D., Kerner, R., Mann, S., Stein, M. D., et al. (2020). Health communication campaigns to drive demand for evidence-based practices and reduce stigma in the HEALing communities study. Drug Alcohol. Depend. 217, 108338. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108338

LinkedIn. (n.d.). Post analytics for your content. Linked Help. Available online at: https://www.linkedin.com/help/linkedin/answer/a516971 (accessed January 03, 2023)..

Lorenz, L. S. (2015). A way into empathy: A “case” of photo-elicitation in illness research. Health 15, 259–275. doi: 10.1177/1363459310397976

Meta Business Help Centre. (n.d a). Facebook post reach. Available online at: https://www.facebook.com/business/help/2259679990843822?ref=search_new_3 (accessed January 03, 2023).

Meta Business Help Centre. (n.d b). Instagram post reach. Available online at: https://www.facebook.com/business/help/4308719409201466?helpref=searchandsr=1andquery=instagram%20reach (accessed January 03, 2023).

Meta Business Help Centre. (n.d c). Impressions. Available online at: https://www.facebook.com/business/help/675615482516035 (accessed January 03, 2023).

Metzler, J. M., Kalaitzopoulos, D. R., Burla, L., Schaer, G., and Imesch, P. (2022). Examining the influence on perceptions of endometriosis via analysis of social media posts: cross-sectional study. JMIR Form Res. 6, e31135. doi: 10.2196/31135

Missmer, S. A., Tu, F., Soliman, A. M., Chiuve, S., Cross, S., Eichner, S., et al. (2022). Impact of Endometriosis on women's life decisions and goal attainment: a cross-sectional survey of members of an online patient community. BMJ Open 12, e052765. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-052765

Naslund, J. A., Aschbrenner, K. A., Marsch, L. A., and Bartels, S. J. (2016). The future of mental health care: peer-to-peer support and social media. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 25, 113–122. doi: 10.1017/S2045796015001067

Neiger, B. L, Thackeray, R., Van Wagenen, S. A., Hanson, C. L., West, J. H., Barnes, M. D., et al. (2012). Use of social media in health promotion purposes, key performance indicators, and evaluation metrics. Health Promot. Pract. 13, 159–164. doi: 10.1177/1524839911433467

Paulovich, B. (2015). Design to Improve the Health Education Experience: using participatory design methods in hospitals with clinicians and patients. Visible Lang. 49, 1–2.

Raja, S. N., Carr, D. B., Cohen, M., Finnerup, N. B., Flor, H., and Gibson, S., et al. (2020). The revised international association for the study of pain definition of pain: concepts, challenges, and compromises. Pain 161, 1976–1982. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001939

Ribera, J. M., and Hausmann-Muela, S. (2011). The straw that breaks the camel's back: redirecting health-seeking behavior studies on malaria and vulnerability. Med. Anthropol. Quart. 25, 103–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1548-1387.2010.01139.x

Ruben, M. A., Blanch-Hartigan, D., and Shipherd, J. C. (2018). To know another's pain: a meta-analysis of caregivers' and healthcare providers' pain assessment accuracy. Ann. Behav. Med. 52, 662–685. doi: 10.1093/abm/kax036

Rus, H. M., and Cameron, L. D. (2016). Health communication in social media: message features predicting user engagement on diabetes-related Facebook pages. Ann. Behav. Med. 50, 678–689. doi: 10.1007/s12160-016-9793-9

Sanders, E. B.-N., and Stappers, P. J. (2008). Co-creation and the new landscapes of design. CoDesign 4, 5–8. doi: 10.1080/15710880701875068

Seear, K. (2009). The etiquette of endometriosis: Stigmatisation, menstrual concealment and the diagnostic delay. Soc. Sci. Med. 69, 1220–1227. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.07.023

Stellefson, M., Paige, S. R., Chaney, B. H., and Chaney, J. D. (2020). Evolving role of social media in health promotion: updated responsibilities for health education specialists. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17, 153. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17041153

Taylor, H. S., Kotlyar, A. M., and Flores, V. A. (2021). Endometriosis is a chronic systemic disease: clinical challenges and novel innovations. Lancet 397, 10276. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00389-5

The European Parliament and The Council of the European Union. (2016). Regulation (EU) 679 of the European Parliament and the Council of 2016 on the Protection of Natural Persons with regard to the Processing of Personal Data and on the Free Movement of Such Data, and Repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation). (europa.eu) (accessed January 03, 2023).

Tomlinson, M. K. (2021). Moody and monstrous menstruators: the Semiotics of the menstrual meme on social media. Soc. Semiot. 31, 421–439. doi: 10.1080/10350330.2021.1930858

Tomlinson, M. K. (2023). “Periods don't stop for pandemics”: the implications of COVID-19 for online and offline menstrual activism in great britain. Women Stud. Commun. 43, 289–311. doi: 10.1080/07491409.2023.2222365

Twitter. (n.d.) Account settings. About your activity dashboard. Definitions. Twitter Help Center. Available online at: https://help.twitter.com/en/managing-your-account/using-the-tweet-activity-dashboard (accessed January 03 2023).

Uchino, B., J, N., Cacioppo, T., and Kiecolt-Glaser, J. K. (1996). The relationship between social support and physiological processes: a review with emphasis on underlying mechanisms and implications for health. Psychol. Bull. 119, 448–531. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.119.3.488

Urban, A., and Holtzman, M. (2023). Menstrual stigma and Twitter. Sociol. Focus, 56, 483–496. doi: 10.1080/00380237.2023.2243588

van den Haspel, K., Reddington, C., Healey, M., Li, R., Dior, U., and Cheng, C. (2022). The role of social media in management of individuals with endometriosis: a cross-sectional study. Aust. N Z J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 62, 701–706. doi: 10.1111/ajo.13524

Whelan, E. (2003). Putting pain to paper: endometriosis and the documentation of suffering. Health 7, 463–482. doi: 10.1177/13634593030074005

Whelan, E. (2007). “No one agrees except for those of us who have it”: endometriosis patients as an epistemological community. Sociol. Health Illness. 29, 957–982. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2007.01024.x

Young, L. E., Soliz, S., Xu, J. J., and Young, S. D. (2020). A review of social media analytic tools and their applications to evaluate activity and engagement in online sexual health interventions. Prev. Med. Rep. 3, 101158. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2020.101158

Zhang, X., Liu, S., Deng, Z., and Chen, X. (2017). Knowledge sharing motivations in online health communities: A comparative study of health professionals and normal users. Comput. Hum. Behav. 75, 797–810. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2017.06.028

Keywords: visual representation, social media metrics, pain, epistemological community, communication, engagement, patient participation, qualitative method

Citation: Stanek DB, Hestbjerg I, Hansen KE, Tomlinson MK and Kirk UB (2023) Not “just a bad period”— The impact of a co-created endometriosis social media health campaign: a mixed methods study. Front. Commun. 8:1154297. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2023.1154297

Received: 31 January 2023; Accepted: 09 October 2023;

Published: 30 October 2023.

Edited by:

António Fernando Coelho, University of Porto, PortugalReviewed by:

Ana Margarida Sardo, University of the West of England, United KingdomCopyright © 2023 Stanek, Hestbjerg, Hansen, Tomlinson and Kirk. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ditte Bonde Stanek, ZGJzQHBoLmF1LmRr; Ida Hestbjerg, aWRoZUBwaC5hdS5kaw==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.