- 1Department of Communication, Université de Montréal, Montreal, QC, Canada

- 2Department of Communication, Baylor University, Waco, TX, United States

This article explores the theoretical terrain surrounding compassion in organizational settings to clarify how conceptually (dis)similar concepts like social support, team care, and organizational compassion manifest different agentic perspectives on compassion. Toward this end, we articulate a working definition of compassion and suggest that a communicative frame focused on intersubjective sense-making and interpretation can deepen our understanding of who is responsible for care and compassion within organizations. Existing research on this subject considers who or what provides compassion—individuals, teams, policies—and how compassion can assuage suffering and promote individual and organizational flourishing. Extending this work, we document core dimensions of each form of compassion for greater conceptual clarity and precision, proposing a metaphor for each. Finally, we reflect on the implications of each type of compassion for resilience and the ways current notions of compassion typify the rationality/emotionality duality and gendered nature of emotion work in organizations.

Introduction

In a time marked by burnout, quiet quitting, and the great resignation, it is imperative to better understand how compassion is communicated in organizational settings. However, whom or what should we study to learn about its accomplishment? Prior research suggests that compassion, as a form of social support, mitigates the effects of workplace stress and decreases burnout and intent to leave (Wright and Nicotera, 2015). Compassion implicates emotions and relationships, both of which are core to organizational experience (Frost, 1999), where positive emotions and social interactions can contribute to happiness and meaningfulness at work (Gavin and Mason, 2004; Cheney et al., 2008) and improve worker productivity (Gottschalk et al., 2006). In contrast, negative emotions can lead to burnout and turnover. Compassion as a response to suffering in organizational settings may therefore be linked to improved outcomes for both employees and organizations.

Given the importance of compassion for organizational flourishing, compassion is surprisingly difficult to define and operationalize (Lown et al., 2016; Strauss et al., 2016; Feo et al., 2018; Ledoux et al., 2018; Durkin et al., 2019). To address this issue, this narrative review documents the core dimensions of various forms of organizationally based compassion, proposes a metaphor that encapsulates the specific view of compassion that emerges, and reflects on the impact each type of compassion has on resilience. Understanding the compassion-resiliency nexus is crucial for managers and organizational leaders seeking to foster compassion in their workplaces, particularly in health and social service organizations where compassion is core to organizational sustainability. This next section explains our selection of the literature for this narrative review.

Selection of literature

While systematic reviews evaluate the quality of empirical studies and scoping literature reviews classify and synthesize research findings within a specific domain, narrative reviews provide a critical overview of published research (Byrne, 2016). Building on our prior work (Fox et al., 2022), we intuited that compassion ranges from a dyadic exchange between two people to emotional support anchored in and implemented through work teams and organizational systems. Therefore, we searched for peer-reviewed publications that focused on how compassion was enacted at organizational, team, and interpersonal levels (within organizational contexts) in the Web of Science, Social Science Abstracts, Communication Abstracts, Business Source Premier, and Sociological Abstracts databases, as well as Google Scholar. Keywords included “organisation*” OR “organization*,” “compassion,” and “definition.” Although conceptual articles and chapters were especially relevant, we included definitions and examples of organizational compassion from empirical studies in organizational communication and management studies scholarship when these were available. We excluded work that took a biological, psycho-physiological, and clinical approach to compassion (e.g., Seppälä et al., 2017).

As we read through the literature, we developed an emergent conceptual framework that distinguished three forms of compassion: compassion in organizations, namely social support and team care, and organizational compassion, which focuses on compassion by organizations. We begin by providing a working definition of compassion and its relation to what it ultimately aims to promote in organizational settings: resilience.

Compassion and resilience

Existing definitions usually divide compassion into three subprocesses, which include cognitive (noticing), moral (feeling, empathizing with), and behavioral (responding) dimensions. Each subprocess is inherently communicative, involving intersubjective sensemaking between the persons offering and receiving compassion. As a process of continually checking in with others, noticing begins with a deep awareness (Ho et al., 2016) and recognition of suffering, pain, and distress (Lown et al., 2016). Compassion next requires “establishing a connection with another person's hurt, anguish, or worry” (Kanov et al., 2004, p. 813), an empathic concern or identification with another's emotional and bodily experiences (Hergue et al., 2018). Nussbaum (2001) combines cognitive and moral dimensions, describing the need for “imaginative reconstruction of the experience of the sufferer” (p. 327). Most importantly, compassion involves a behavioral dimension or a decision to act in consequence to alleviate the pain or suffering, even if it cannot eliminate it (Frost et al., 2000; Kanov et al., 2016; Ledoux et al., 2018). As Aboul-Ela (2017) notes, compassionate acts can vary considerably: verbal support; empathic listening; gestures of emotional, informational, financial, or spiritual support; flexible workplace practices; and caregiving among co-workers.

Researchers and managers often attempt to foster compassion at work because of compassion's positive impact on resilience. Resilience refers to the ability of individuals, groups, organizations, and even entire communities to bounce back or absorb strain from adverse conditions following disruptions, crises, disasters, or ongoing burdens (Vogus and Sutcliffe, 2007; Buzzanell, 2010, 2018). Resilience allows for re-establishing severed or disrupted connections and reconfigures networks. According to Buzzanell, resilience contributes to a return to normalcy, rekindles organizational routines, and enables teams to stabilize their performance and engage in goal-directed activities (Williams and Shepherd, 2017; Stoverink et al., 2020).

Given the important links between compassion at work and resilience, we turn now to a discussion of three forms of compassion within organizational settings that we identified in the organizational communication and management literature, namely social support, team care, and organizational compassion, to then explore what each form means for resilience.

Social support

Social support refers to an interpersonal, dyadic helping relationship where partners engage in supportive communication processes, in hopes of easing, validating, or empathizing with the suffering member's experiences (House, 1981; Heaney, 1991; Kahn, 1993; Boren, 2017). Although some argue that social support is not a form of compassion because it focuses primarily on responding to suffering (Kanov et al., 2004), most definitions of social support include an emotional response (feeling) as a core component, presumably to suffering that the supporter notices. Hence, we include social support as a form of compassion. Social support typically involves a relationship wherein supporters (1) demonstrate emotionally sustaining behaviors that communicate care, concern, and affiliation to sufferers; (2) offer advice, suggestions, and guidance that increase an individual's capacity to withstand disruptions (i.e., resilience); and (3) provide material or financial assistance with completing tasks (Cobb, 1976; Pearson, 1986). Social support is thus framed as a helping behavior by a social supporter with more resources, information, and connections than the supportee.

Indeed, Kanov et al. (2004) speak about using social support to “replenish” colleagues, who are metaphorically presented as empty vessels and need to be (re)filled by their co-workers (see also Dutton et al., 2014). Dutton et al. (2002) describe a hospital where employees donate paid vacation or personal days to organizational members who need time off due to painful or difficult circumstances. This idea of fullness on the side of the social supporter is complemented by images of strength. The literature speaks of the informational and reframing aspects of social support as a “buffer” that builds supportees' repertoire of coping strategies and reduces the sense of environmental threat through cognitive relabeling and re-appraisal. As the job demands and resources model suggests (see Bakker and Demerouti, 2007), social support increases workers' access to and use of resources such that they can better cope with their job's demands.

Importantly, social support is presented as a positive organizational phenomenon that helps supportees manage stress and improve their mental and physical wellbeing. Yet, social support can increase suffering for three reasons. First, when interactions degenerate into co-rumination (dwelling on the negative dimensions or the unresolvable nature of problems) or impede problem-solving, social support can worsen distress (Boren, 2014). Second, models of social support presume that distress is visible to supporters. Boren and Veksler's (2015) model of communicatively restrictive organizational stress (CROS) indicates that some workers are unable to communicate their stress to others due to institutional privacy policies, desire to save face, or lack of trust within co-worker relationships. In these circumstances, noticing subtle cues during daily interactions—the first subprocess of compassion—can become difficult if not impossible (Kanov et al., 2004). For those needing support, stress increases as “a result of the frustration associated with learning that one's perceptions of availability of support were inaccurate” (Boren, 2017, p. 7). To overcome this difficulty, which impedes the actualization of social support, we perhaps need to shift the first key process of compassion from “noticing” (Kanov et al., 2004) to “recognizing” (Miller, 2007). Way and Tracy (2012) explain this difference:

Noticing, by definition and theorization, suggests awareness, attention, and observation. Recognizing goes further and implies noting the meanings of communication behaviors as well as the meanings of what is not being communicated. Recognizing implies that we understand the value in others' communicative cues, timing, and context, as well as the cracks and schisms between various messages. (p. 301)

Third, while social support is unidirectional in any given episode, there is an underlying expectation of reciprocity between members over longer periods of time. In other words, the support network must be equitable to be sustainable in the long run. This supports the moral code at work, where nobody is exempt from productivity norms.

Team care

Team care is another form of organizationally based compassion that, like social support, is not necessarily institutionalized or supported by the organization. Team care involves collective compassionate practices that are embedded in a “care system,” where dyads, groups, teams, or even entire organizational units mitigate burnout and emotional distress by sharing significant occupational stressors. Studies of team care foreground team cohesion, relational collaboration, and co-worker interdependence, which help team members to heal or recover from suffering and strengthens workplace commitment, particularly when the broader organization and leadership team engage in compassionate care (Grant et al., 2008; Powley, 2009; Lilius et al., 2011; Madden et al., 2012; Simpson et al., 2013; Afifi, 2018). It is worthwhile noting that organizational systems and practices such as compassionate leadership facilitate team care (Vogel and Flint, 2021; Fox et al., 2023); when organizations fail to cultivate team care, team members risk burnout long-term.

Importantly, compared to social support which involves a unidirectional helping relationship between a supporter and a supportee, team care is reciprocal and continually circulating among collaborators. This systemic view of team care suggests a different metaphor for compassion, namely that of a self-regulating thermostat. As shared stress levels rise, collaborators adjust, pulling together to provide the mutual care needed to weather the storm. Yet, the metaphor indicates that team care has upper limits. Once this is reached, co-workers may deliberately decide not to “notice” suffering, because when “our hearts go out to [others] through our sustained compassion, our hearts can give out from fatigue” (Radey and Figley, 2007, p. 207). Team care thus exemplifies what Mumby and Putnam (1992) term “bounded emotionality,” which encourages workers to express feelings and develop caring communities, but simultaneously restricts emotional expression through “negotiated feeling rules, which mark members' needs and limitations” (Ashcraft and Kedrowicz, 2002, p. 93).

The expectation of bounded give-and-take in team care underscores team care's negotiated nature in both proactive and reactive ways (Way and Tracy, 2012). For instance, Lilius et al.'s (2011) study within a medical billing unit identified reactive team-level practices such as “help-offering,” which normalized “needing help and receiving help, minimizing feelings of strain, embarrassment, or inadequacy” (p. 879). At the same time, team members proactively constrained when, how much, and how often colleagues could discuss suffering, by indicating that conversations about certain subjects needed to draw to a close. These findings suggest that compassion in organizational settings is not just in the eye of the “supporter” or the “sufferer,” but must be collectively negotiated (Simpson et al., 2013).

The centrality of such negotiation highlights the need for a more relational conceptualization of the second and third subprocesses of compassion, “feeling” and “responding” (Kanov et al., 2004). Miller (2007) suggests that “connecting” rather than “feeling” better captures the relational nature of compassion. Way and Tracy (2012) concur, proposing the notion of “relating,” which expresses a shared sense of self in a consubstantial relationship: a tight connection that facilitates communication and understanding and that goes beyond “simply engaging in cooperative activity. It is a feeling of mutuality that enables individuals to share the emotions, values, and decisions that allow them to act together” (Gossett, 2002, p. 386).

The thermostat metaphor also seems to indicate that the sub-processes of compassion are not necessarily linear (Way and Tracy, 2012), but overlapping and recursive. Thinking of team care as mutually negotiated yet bounded points to the need to bolster team care with organizational support when members' needs surpass teams' capacity to meet them. For example, some frontline health care personnel implemented a buddy system during the COVID-19 pandemic, where peers with similar career stages, workplace responsibilities, and shared life circumstances engaged in rapid-fire check-ins (1–10 min) two to three times per week. Together, they listened, validated the other's emotions, and developed strategies to deal with changing circumstances (Albott et al., 2020). Yet, if suffering became too intense to be regulated within the dyad, individuals could be referred to designated mental health consultants for additional support or to other professionals outside the organization. We discuss the contours of organizational compassion in the following section.

Organizational compassion

Although team care can inspire compassionate relationships among co-workers and with managers (Frost, 1999; Ferris et al., 2009; Sias, 2014), organizational compassion occurs when compassion is coordinated and managed by the organization itself. For some organizations in health and social care, support, and emergency services, whose mission includes addressing human pain and suffering, a “collective compassion capability may be particularly important for sustained organizational survival and effectiveness” (Kanov et al., 2004, p. 810). When we speak about organizational compassion, we mean the individuals, routines, policies, and built spaces and so forth that “speak for” the organization (Cooren, 2012) and that communicate compassion. It is thus more than the sum of aggregated individual workers' compassionate behavior (Madden et al., 2012) and involves an ongoing, systemic capacity to notice, feel, and respond to suffering (Frost, 1999; Frost et al., 2000, 2006; Kanov et al., 2004; Dutton et al., 2006). Others have proposed four rather than three processes: noticing, empathizing, assessing the context and causes of suffering, and responding (NEAR) (see Dutton et al., 2014; Simpson and Farr-Wharton, 2017).

To enact organizational compassion, organizations must legitimize compassion sub-processes and weave them into organizational systems, values, and routines. Organizational compassion also emerges in mindful, collective “care-fulness” (Kanov et al., 2004) about organizational processes, policies, resource allocation, and role distribution. We propose that the metaphor underpinning organizational compassion is one of suffering as toxic until shared and diffused. That is, suffering is presented as noxious for the individual when it is carried alone; compassion, which diffuses suffering throughout the organization, makes it visible, normal, and less harmful.

The first compassion sub-process, collective noticing, requires shared appreciation that suffering or unmet needs exist, by “heighten[ing] members' vigilance for pain and provid[ing] a language with which to identify it” (Kanov et al., 2004, p. 816). Here, suffering's visibility does not depend solely on interpersonal familiarity and empathic sensitivity but how organizations allow their members to signal their need for compassion. Although many organizations continue to individualize suffering by communicating private helpline numbers to employees in distress (Hewison et al., 2019) or putting the onus on workers to access employee assistance programs (Roche et al., 2018), it is also possible for organizations to invest in resources, programs, and tools that foster noticing. One key organizational resource is the built environment, which can constrain or cultivate interaction and thus the ability to notice others' suffering. As Trzpuc and Martin's (2010) architectural analysis of medical-surgical nursing units demonstrates, poor spatial design reduces interpersonal visibility and accessibility to others. Easier to change than the built environment is the option to create time to notice and interact. Regular discussions and practices such as debriefing and sharing facilitate collective compassion. Juvet et al.'s (2021) study on resilience strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic reported staff appreciation for morning meetings that began by “checking in with everyone, leaving time for questions and the expression of any fears. All topics, even private ones, could be discussed” (p. 7).

We are more ambivalent about Kanov et al.'s (2004) enthusiasm for technologies that automatically signal employee distress, as visibility implies surveillance, loss of worker autonomy, and organizational judgments about individuals' “compassion worthiness” (Simpson et al., 2014). CISCO's CEO, for example, is notified within 48 hours when employees experience serious health issues or a bereavement in the family (Kanov et al., 2004). To avoid “Big Brother” monitoring that informs organizations of suffering regardless of workers' personal preferences about how to segment their working and personal lives, initiatives should be assessed by compassion receivers. This potentially dark side of organizational compassion highlights the need to hone how we perform “noticing.” As discussed in the section on social support, Miller's (2007) notion of “recognizing” entails personalization or “noticing details about another's life so that the compassionate response can be made in the most appropriate manner” (p. 235). Speed, scope, and the scale of compassionate responses must be balanced against customization (Simpson et al., 2020).

Embedding the second organizational compassion sub-process, collective feeling, at an organizational level requires organizational cultures that acknowledge and authorize discussions of the emotional dimensions of work. However, professional socialization can work against an organizational culture of compassion. Workers who experience pressure to maintain “a stiff upper lip” (Nissim et al., 2019, p. 36) find themselves unable to dismantle established emotion rules (Kramer and Hess, 2002). Organizations wishing to foster compassion must also consider how occupational hierarchies inhibit employees who fear manifesting vulnerability in front of subordinates and supervisors.

Compassionate leaders can make important changes in a compassionate organization's “social architecture,” which comprises social networks, roles, routines, culture, leadership, and stories told (Dutton et al., 2006; Worline and Dutton, 2017). Yet, normalizing negative emotions and empowering employees to express feelings can backfire. Ashcraft and Kedrowicz (2002) studied a domestic violence shelter, where emotional expression was an institutionalized organizational norm. Volunteer workers found full-time staff's positive emotional support to be inauthentic and excessive, missing the mark of what they needed in terms of compassion. Instead, volunteer workers wished to receive multi-faceted feedback that incorporated informational and appraisal support as well as emotional encouragement. Interventions such as post-event analysis could be a more appropriate form of organizational compassion. For instance, interdisciplinary teams in a Belgian neonatal intensive care unit conducted post-event analysis 2 weeks after every child's death (Minguet and Blavier, 2018). Team members collectively made sense of how they had worked together, articulated their emotional reactions, and reflected on the quality of their work practices, as the suffering associated with death was as much a professional crisis as a personal one. Combining feelings with cognitive evaluations spurred changes in clinical practice. “Feeling” as a compassionate process generated preventative as well as reactive responses, better captured by Way and Tracy's (2012) term, “(re)acting.”

The third process, collective responding, involves a coordinated behavioral response where multiple organizational members respond compassionately. Some compassion researchers suggest that certain people or groups should take on this responsibility for the organization, thus compartmentalizing compassionate responding. Kanov et al. (2004) write, “We can imagine the existence of pockets of compassion in an organization, such that some departments or divisions exhibit more compassion than others, this often varying over time and across situations” (p. 821). Yet, delegating compassion to organizationally recognized compassionate leaders is problematic because it downplays the role played by informal “compassion leaders” who instigate social support and team care. Others argue that organizations can become compassionate in an organic, unplanned, bottom-up way, without input from managers (Simpson et al., 2020). Madden et al. (2012), for example, propose that organizational actors who expand their roles to integrate compassionate action eventually modify the whole system: Permission to go beyond one's role “morphs into obligation” (p. 699) as the extra-role acts become an in-role requirement. They do not, however, mention the possibility that this process could reinforce gender and occupational stereotypes. Leaving compassion to individuals, groups, or departments who are presumed to have a “natural” tendency to care for others also ignores the responsibility that all individuals have to both receive and give care (Tronto, 2013).

Another dark side of compartmentalized organizational compassion is its contribution to compassion fatigue resulting from constant exposure to suffering (Figley, 2002; Frost, 2003; Jacobson, 2006). Some leaders and managers, whom the organization designates as “toxic handlers,” end up “contagiously” absorbing others' pain and hurt (Frost, 2003; Anandakumar et al., 2007; Simpson et al., 2013). Kahn's (2019) study describes how employees who feared compassion fatigue engaged in “distress organizing.” They developed protective interpersonal walls that made them impervious to others' emotional state and shut down the space and time for relationships that exposed them to suffering. Unfortunately, Kahn's findings show that dispassionate responding leads to emotional isolation and exhaustion, which increases rather than reduces distress. Consequently, organizations must create a collective sense of responsibility for giving compassion.

In addition, organizational distribution of resources that enable compassion must give all workers the chance to receive compassion. If compassionate responses at the organizational level are perceived to be arbitrary, unfair, or due to favoritism (du Gay, 2008), being a compassion receiver can inspire jealousy (Simpson and Berti, 2020). For instance, Kirby and Krone (2002) found that employees did not use family leave because coworkers who did not need it complained about unfairness and having to “pick up slack.” This suggests that programs and policies that contribute to human flourishing for all employees should accompany initiatives to promote compassion, thus moving the discussion from compassion as undermining fairness to compassion as promoting equity (Simpson and Berti, 2020).

Compassion's conceptual consequences for responsibility and resilience

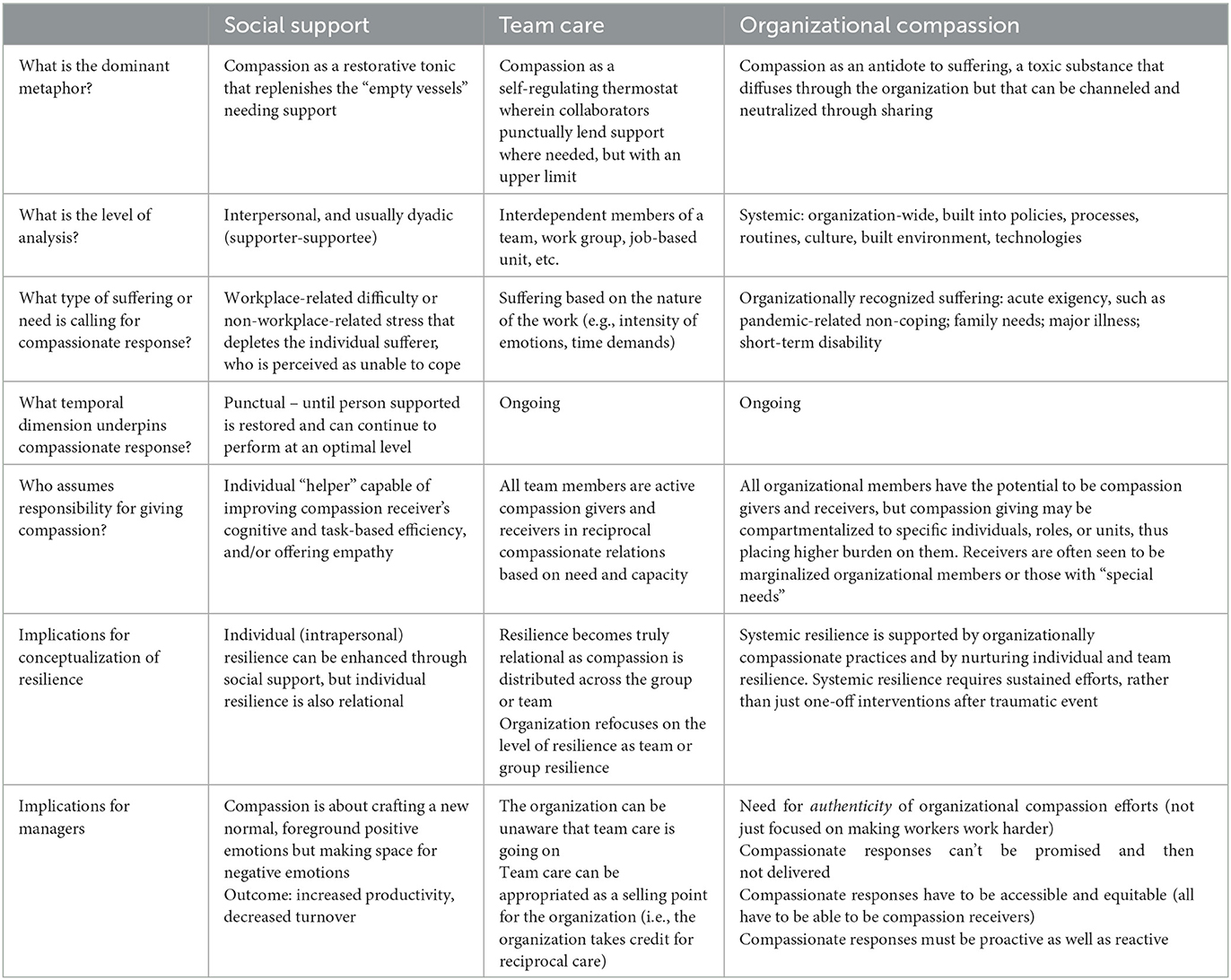

Our conceptual review has described the contours of three forms of compassion within and by organizations: social support, team care, and organizational compassion (see Table 1). The metaphors describing suffering and compassion that underpin each approach indicate who takes responsibility for compassion and to what extent compassionate responding is personalized or institutionalized.

Importantly, rather than advocating for a specific form of promising compassionate practice, we propose that organizations weave them together, because social support, team care, and organizational compassion have strengths that balance out their respective weaknesses. Moreover, as we will explain in this section, each form contributes to developing and reinforcing resilience at a different level. We also integrate practical implications for managers and other organizational leaders.

Our discussion of social support confirms that such support fosters individual resilience through interpersonal communication. Social support's interpersonal character tells us that individual resilience is not just intrapersonal but relational. This relational understanding of resilience, however, differs in some ways from Buzzanell's (2010) depiction of communicative resilience. The five key processes Buzzanell elaborates (crafting normalcy; affirming identity anchors; maintaining and using communication networks; putting alternative logics to work; and downplaying negative feelings) emphasize the importance of rational thinking, which downplays negative emotions and discomfort and enables individuals to prioritize productive responses to disruptive events. For instance, it is thought that resilient organizational members acknowledge but minimize negative feelings such as fear, distress, and concern associated with disruption. This allows them to cultivate positive emotions like hopefulness and self-efficacy that help them mobilize the informational, relational, and material resources they need to engage in forward-looking action and transformation (Buzzanell, 2018). In contrast, because compassionate communication includes interpersonal actions such as verbal support and empathically listening to another's suffering, social support does not require supportees to downplay their emotions in order to cope and keep moving forward. Conceptually, the relational nature of compassionate social support suggests that there may well be a place for negative emotions in resilience precisely through dyadic interpersonal communication.

Practically, socially supportive relationships, where discussion of difficulties and suffering is permitted, may serve as “oases of compassion” within compassionately arid or hostile organizational environments (Frost et al., 2000, p. 38). Although their existence contributes to increased resilience, productivity gains, and reduced turnover (Shatté et al., 2017; Underdahl et al., 2018), the negative emotions they enable organizational members to process may remain invisible to managers and other organizational leaders, as they are hidden within the folds of dyadic relationships and kept out of the public eye. Lack of visibility can be problematic because organizations can fail to support the supporters: Because social support tends to exist on an ad-hoc basis among organizational members in relationship with one another, it may deplete compassion quickly. Hence, we urge managers and other organizational leaders to recognize dyadic social support and to sustain the crafting of a new “compassionate normal,” where there is the space and safety needed for emotional expression, both positive and negative.

However, as we saw with team care as a form of compassion in organizational settings, the survival of the team as an emotionally self-regulating system does require bounded emotionality (Buzzanell, 2018), which circumscribes the expression of negative emotions. This has two clear implications for managers and other organizational leaders. First, organizations should recognize that resilience is not only individual but also relational, reciprocal, and collective, existing at the team or group level and dependent on compassion distributed among collaborating members. Communication processes between team members may provide support or re-establish normalcy and routines that build or sustain resilience. Second, as with social support, managers may be unaware that team care is occurring, but inadvertently (or even intentionally) “take credit” for the performance of a compassionately well-regulating team, which might lead to bitterness or cynicism on the part of team members. Hence, to foster and nurture team care, managers must be cognizant of team members' reciprocal compassion and provide environments that facilitate the team's engagement in compassionate communication (Dubois et al., 2020).

Fostering compassion in organizational systems and practices not only benefits individual and team resilience but systemic resilience at the organizational level. Indeed, a similarity across the compassion and resilience literatures is that both can be viewed as relational, systemic processes within organizational contexts. An entire organization may be considered to be compassionate and/or resilient in its processes, procedures, and offerings to members. Compassion by the organization requires mindful noticing, feeling, and responding to be embedded in organizational systems, policies, and routines. Similarly, organizational resilience flows from a systemic ability to absorb strain, adapt, and transform in the face of challenges and keep action moving forward through intentional redundancies, slack, and margin (Weick and Sutcliffe, 2001; Roeder et al., 2021). Like resilience at the community level, organizational resilience demands that whole systems can “anticipate and plan for events before they occur” (Houston, 2018, p. 19).

In their systematic review, Barasa et al. (2018) suggested that building organizational resilience requires organizations to invest in appropriate resources; prepare for acute shocks and routine, everyday stressors; create multiple alternative courses of action when adverse events occur; develop collaborative organizational cultures; and frame shocks as opportunities for learning. We see a conceptual and practical resonance between the two concepts. Just as organizational resilience requires preparation or planned resilience, organizational compassion requires proactive decisions about organizational spaces, resources, timetables that offer opportunities to interact with others, and policies that address employees' needs. Organizational resilience also includes adaptive resilience, whereby organizations react to acute shocks and develop new capacities: Likewise, organizational compassion needs to use multiple, individualized pathways, rather than imposing a one-size-fits-all approach, and to spread the responsibility for compassion widely within the organization. We appreciated Barasa et al.'s insistence on everyday resilience that considers routine or chronic suffering as requiring an organizational response, so that compassionate responses are not limited to punctual interventions during or after a traumatic event or period (e.g., organizational helplines during the COVID-19 pandemic; Hewison et al., 2019). Truly systemic cultures of compassion sustain organizational resilience.

The implications for managers and organizational leaders are multiple. First, they should not instrumentalize organizational compassion as a means to promote workplace flourishing and thereby enhance worker output. To avoid cynicism and disengagement, it is essential that workers perceive organizational efforts to foster compassion as authentic and genuinely motivated by concern for their wellbeing. Compassion's ability to be (mis)used as a tool for enhancing organizational productivity merits additional attention. Given that the scope of this paper is primarily to describe our emergent conceptual framework on organizational compassion, we encourage future work to examine how organizations can avoid manipulating compassion as a (managed) tool for gain (public-facing research networks such as the Positive Communication Network, https://positivecommunication.net, and the Compassion Lab, https://compassionlab.com, could inspire organizational initiatives). Second, managers and organizational leaders must follow through on promises of organizational compassion and ensure that organizational responses are accessible and equitable, so that those in need do not fear stigmatization when they benefit from them. In the case of family leave, for example, an equitable compassionate response might offer time off to everyone for non-work-related commitments. Third, because not everyone has the agency to find or use organizationally compassionate responses to their suffering, organizations should promote proactive as well as reactive responses to suffering. For instance, managers who are mindful of members' suffering could proactively suggest organizational supports that sufferers might be unaware of. Third, organizations must decide how they will recognize, incite, and reward in/formal compassion leadership in ways that do not make compassionate labor burdensome for those who carry it out.

Unanswered questions and future directions for theorizing compassion in organizational settings

By schematizing the literature on three forms of compassion in organizational settings, this narrative review provides greater conceptual clarity and precision in our theorization and application of organizationally based forms of compassion. Yet, we note several surprising blind spots that compassion-centered research in organizations has tended to overlook.

First, although recent theoretical work has highlighted the paradoxical nature of compassion (Simpson and Berti, 2020; Simpson et al., 2020; e.g., compassion as both sentimental and rational; a sign of weakness and of strength; individual-level support and institutional policy response), most empirical studies continue to replicate the rationality/emotionality duality in organizations – and to privilege rationality (Putnam and Mumby, 1993). As we have shown, definitions of organizational compassion show organizational members cognitively assessing the context and causes of suffering and rationally deciding how to respond, as well as showing empathy (Simpson et al., 2020). Scholarly studies on the outcomes of compassion show that organizations can appropriate compassion for rational, instrumental purposes such as reducing workplace stress and trauma (Miller, 2007). Similarly, compassionate team care produces more satisfied, committed workers (Nissim et al., 2019). Thus, by attending to individuals' emotional needs through compassion, organizations “use emotions for rationalized ends” (Dougherty and Drumheller, 2006, p. 218).

Consequently, future studies should consider how compassion acts as a form of emotional control in organizations, which may constrain or discipline other forms of compassionate emotional expression. That is, organizations can foster workers' understanding of compassion as noticing, listening, and affirming in ways that say “I see your pain and I'm here for you.” This understanding creates and solidifies emotional display rules that dictate that more volatile forms of compassion are inappropriate: Whereas listening attentively to a teary colleague or offering him a quick hug might be organizationally acceptable, loudly weeping together, embracing another's body, and other passionate displays of compassion likely fall outside the bounds of acceptable, and rational, forms of compassion. As Dougherty and Drumheller (2006) note, “Rationality is considered to be the desired process in organizations in which members are controlled, efficient, goal oriented, and strategic. Organizations become weak and irrational when emotions cloud judgment and members show passion or develop caring relationships” (p. 233). Future research should highlight how compassion can be communicated in complex and/or extreme forms.

Relatedly, compassionate care and forms of communicating vary based on geographical, cultural, political, and social patterns or differences within organizations. Enacting compassion across physical divides (hybrid work policies mean that coworkers are no longer physically co-present, necessitating online compassion) and ideological/political divisions (toxic office politics and political polarization create workplaces where colleagues do not like or trust each other) is certainly no small feat. Future research must consider how to cultivate and communicate organizationally based compassion when workers feel distanced from colleagues, managers, and even the organization itself.

Another avenue for future research is the interplay between gender ideals and organizational compassion. Gender organizes our language and discursive practices in ways that (re)create masculine and feminine divisions of emotional labor (Buzzanell, 1995). Because compassion requires sensitivity toward others, a mindfulness toward collective wellbeing, and a legitimization of emotions in the workplace, assumptions about who is doing this emotional work abound. Current conceptualizations of compassion are immersed in the performance of femininity, especially when compassion is understood as being weak rather than strong (Simpson and Berti, 2020). For example, empirical studies of “compassion fatigue” originated among nurses (Abendroth and Flannery, 2006)—a profession with gendered assumptions—where the prolonged stresses that accompany caring for others generate an industry-specific type of burnout (Miller, 2007). Frequently, compassion fatigue is treated as a condition that individual workers need to mitigate or overcome, rather than the result of a gendered organizational performance. Whether intentional or not, when a gendered social identity bears the brunt of compassion's negative consequences, it “elucidates how occupations come to appear ‘naturally' possessed of features that fit certain people yet are improbable for others” (Ashcraft, 2013, p. 6).

Surprisingly, rarely does gender appear as a central, constitutive feature of scholarly work on compassion in organizational contexts. Instead, researchers treat gender as an adjacent attribute of industries where compassion is requisite. Take for instance Way and Tracy's (2012) influential work on conceptualizing compassionate communication within hospice care. While attending to how compassion is a complex, embodied communicative act that requires empathy and connection to another person, this work never mentions gender. Similarly, Miller's (2007) research on compassionate communication within human service work describes compassion as an other-centered emotional accomplishment that is marked by displays of warmth, concern, and recognition of another's suffering, yet it makes no reference to gender. Instead, assumptions about who is doing human service work requiring compassion are taken for granted. In other words, the gendered, macro-level social scripts that organize the micro-level communication of compassion are rendered invisible (Kirby, 2007).

Future work, then, must focus more on the intersection and interplay between gender, occupational identity, and assumptions about who should be “doing” compassion-based labor within organizations. To be clear, we are not arguing that gender is naturally predictive of compassionate communication. Instead, we advance the idea that gender has been a historically overlooked means for both studying and promoting compassion, particularly in research that studies the helping professions. Moving forward, we advocate for normalizing the sharing of negative emotions and the cultivation of empathic concern across gender identities.

In closing, we revisit our opening question: Whom or what should we study to learn about compassion in organizational settings? Our work describes how compassion is communicated at multiple levels in organizations, and how it relates to individual, collective, and systemic resilience. Rather than reproducing the view that there are certain groups or people who are (more easily) equipped to do the work of compassion, we recognize that the communication of compassion should be, can be, is for everyone.

Author contributions

KM co-conceptualized the topic, led the project, manuscript writing, literature search, and selection and analysis of articles for the conceptual review. SF co-conceptualized the topic and contributed to the analysis and writing of the manuscript. JF contributed to conceptualizing and writing future research directions. AR contributed to conceptualizing and writing about resilience. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

Open access was enabled by funds from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (grant number 435-2020-1274).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Aboul-Ela, G. M. B. E. (2017). Reflections on workplace compassion and job performance. J. Hum. Values 23, 234–243. doi: 10.1177/0971685817713285

Afifi, T. D. (2018). Individual/relational resilience. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 46, 5–9. doi: 10.1080/00909882.2018.1426707

Albott, C. S., Wozniak, J. R., McGlinich, B. P., Wall, M. H., Gold, B. S., Vinogradov, S., et al. (2020). Battle buddies: rapid deployment of a psychological resilience intervention for health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Anesthesia Anal. 131, 43–54. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000004912

Anandakumar, A., Pitsis, T. S., and Clegg, S. (2007). “Everybody hurts, sometimes: The language of emotionality and the dysfunctional organization,” in Research Companion to the Dysfunctional Workplace: Management Challenges and Symptoms, eds J. Langan-Fox, Cooper CBE, C. L., and R. J. Klimoski (London: Edward Elgar).

Ashcraft, K. L. (2013). The glass slipper: “Incorporating” occupational identity in management studies. Acad. Manage. Rev. 38, 6–31. doi: 10.5465/amr.2010.0219

Ashcraft, K. L., and Kedrowicz, A. A. (2002). Self-direction or social support? Nonprofit empowerment and the tacit employment contract of organizational communication studies. Commun. Monograph. 69, 88–110. doi: 10.1080/03637750216538

Bakker, A. B., and Demerouti, E. (2007). The job demands-resources model: State of the art. J. Managerial Psychol. 22, 309–328. doi: 10.1108/02683940710733115

Barasa, E., Mbau, R., and Gilson, L. (2018). What is resilience and how can it be nurtured? A systematic review of empirical literature on organizational resilience. Int. J. Health Policy Manage. 7, 491–503. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2018.06

Boren, J. P. (2014). The relationships between co-rumination, social support, stress, and burnout among working adults. Manage. Commun. Q. 28, 3–25. doi: 10.1177/0893318913509283

Boren, J. P. (2017). “Social support,” in International Encyclopedia of Organizational Communication, eds C. R. Scott and L. Lewis (New York, NY: Wiley).

Boren, J. P., and Veksler, A. E. (2015). Communicatively restricted organizational stress (CROS) I: Conceptualization and overview. Manage. Commun. Q. 29, 28–55. doi: 10.1177/0893318914558744

Buzzanell, P. M. (1995). Reframing the glass ceiling as a socially constructed process: Implications for understanding and change. Commun. Monographs 62, 327–354. doi: 10.1080/03637759509376366

Buzzanell, P. M. (2010). Resilience: talking, resisting, and imagining new normalcies into being. J. Commun. 60, 1–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2009.01469.x

Buzzanell, P. M. (2018). Organizing resilience as adaptive-transformational tensions. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 46, 14–18. doi: 10.1080/00909882.2018.1426711

Byrne, J. A. (2016). Improving the peer review of narrative literature reviews. Res. Int. Peer Rev. 1, 1–4. doi: 10.1186/s41073-016-0019-2

Cheney, G., Zorn, T. E., Planalp, S., and Lair, D. J. (2008). Meaningful work and personal/social well-being: Organizational communication engages the meanings of work. Annal. Int. Commun. Assoc. 32, 137–185. doi: 10.1080/23808985.2008.11679077

Cobb, S. (1976). Social support as a moderator of life stress. Psychosomatic Med. 38, 300–314. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197609000-00003

Cooren, F. (2012). Communication theory at the center: Ventriloquism and the communicative constitution of reality. J. Commun. 62, 1–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2011.01622.x

Dougherty, D. S., and Drumheller, K. (2006). Sensemaking and emotions in organizations: Accounting for emotions in a rational(ized) context. Commun. Stu. 57, 215–238. doi: 10.1080/10510970600667030

du Gay, P. (2008). “Without affection or enthusiasm”: problems of involvement and attachment in “responsive” public management. Organization 15, 335–353. doi: 10.1177/1350508408088533

Dubois, C. A., Borgès Da Silva, R., Lavoie-Tremblay, M., Lespérance, B., Bentein, K., Marchand, A., et al. (2020). Developing and maintaining the resilience of interdisciplinary cancer care teams: an interventional study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 20, 1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-05882-3

Durkin, J., Usher, K., and Jackson, D. (2019). Embodying compassion: a systematic review of the views of nurses and patients. J. Clin. Nurs. 28, 1380–1392. doi: 10.1111/jocn.14722

Dutton, J. E., Frost, P. J., Worline, M. C., Lilius, J. M., and Kanov, J. M. (2002). Leading in times of trauma. Harvard Bus. Rev. 80, 54–61.

Dutton, J. E., Workman, K. M., and Hardin, A. E. (2014). Compassion at work. Ann. Rev. Org. Psychol. Org. Behav. 1, 277–304. doi: 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091221

Dutton, J. E., Worline, M. C., Frost, P. J., and Lilius, J. M. (2006). Explaining compassion organizing. Admin. Sci. Q. 51, 59–96. doi: 10.2189/asqu.51.1.59

Feo, R., Kitson, A., and Conroy, T. (2018). How fundamental aspects of nursing care are defined in the literature: a scoping review. J. Clin. Nurs. 27, 2189–2229. doi: 10.1111/jocn.14313

Ferris, G. R., Liden, R. C., Munyon, T. P., Summers, J. K., Basik, K. J., Buckley, M. R., et al. (2009). Relationships at work: toward a multidimensional conceptualization of dyadic work relationships. J. Manage. 35, 1379–1403. doi: 10.1177/0149206309344741

Figley, C. R. (2002). “Introduction,” in Treating Compassion Fatigue, eds C. R. Figley (London: Routledge), 1–14.

Frost, P. J. (1999). Why compassion counts! J. Manage. Inquiry, 8, 127–133. doi: 10.1177/105649269982004

Frost, P. J., Dutton, J. E., Maitlis, S., Lilius, J. M., Kanov, J. M., Worline, M. C., et al. (2006). “Seeing organizations differently: three lenses on compassion,” in The Sage Handbook of Organization Studies, 2nd Edn (London: Sage), 843–866.

Frost, P. J., Dutton, J. E., Worline, M. C., and Wilson, A. (2000). “Narratives of compassion in organizations,” in Emotion in Organizations, ed S. Fineman (London: Sage), 25–45.

Gavin, J., and Mason, R. (2004). The virtuous organization: the value of happiness in the workplace. Org. Dyn. 33, 379–392. doi: 10.1016/j.orgdyn.2004.09.005

Gossett, L. (2002). Kept at arm's length: Questioning the organizational desirability of member identification. Commun. Monograph. 69, 385–404. doi: 10.1080/03637750216548

Gottschalk, M., Munz, D. C., and Grawitch, M. J. (2006). The path to a healthy workplace: a critical review linking healthy workplace practices, employee well-being, and organizational improvements. Consult. Psychol. J. Prac. Res. 58, 129–147. doi: 10.1037/1065-9293.58.3.129

Grant, A. M., Dutton, J. E., and Rosso, B. D. (2008). Giving commitment: employee support programs and the prosocial sensemaking process. Acad. Manage. J. 51, 898–918. doi: 10.5465/amj.2008.34789652

Heaney, C. A. (1991). Enhancing social support at the workplace: assessing the effects of the caregiver support program. Health Educ. Q. 18, 477–494. doi: 10.1177/109019819101800406

Hergue, M., Lenesley, P., and Narme, P. (2018). (2019). Satisfaction au travail et culture managériale empathique en EHPAD: étude exploratoire dans deux établissements. NPG Neurologie - Psychiatrie - Gériatrie 19, 23–29. doi: 10.1016/j.npg.2018.09.004

Hewison, A., Sawbridge, Y., and Tooley, L. (2019). Compassionate leadership in palliative and end-of-life care: a focus group study. Leadership Health Serv. 32, 264–279. doi: 10.1108/LHS-09-2018-0044

Ho, A. H. Y., Luk, J. K. H., Chan, F. H. W., Chun Ng, W., Kwok, C. K. K., Yuen, J. H. L., et al. (2016). Dignified palliative long-term care. American J. Hospice Palliative Med. 33, 439–447. doi: 10.1177/1049909114565789

Houston, J. B. (2018). Community resilience and communication: dynamic interconnections between and among individuals, families, and organizations. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 46, 19–22. doi: 10.1080/00909882.2018.1426704

Jacobson, J. M. (2006). Compassion fatigue, compassion satisfaction, and burnout: Reactions among employee assistance professionals providing workplace crisis intervention and disaster management services. J. Workplace Behav. Health, 21, 133–152. doi: 10.1300/J490v21n03_08

Juvet, T. M., Corbaz-Kurth, S., Roos, P., Benzakour, L., Cereghetti, S., Moullec, G., et al. (2021). Adapting to the unexpected: Problematic work situations and resilience strategies in healthcare institutions during the COVID-19 pandemic's first wave. Safety Sci. 139, 105277. doi: 10.1016/j.ssci.2021.105277

Kahn, W. A. (1993). Caring for the caregivers: patterns of organizational caregiving. Admin. Sci. Q. 38, 539–563. doi: 10.2307/2393336

Kanov, J. M., Maitlis, S., Worline, M. C., Dutton, J. E., Frost, P. J., Lilius, J. M., et al. (2004). Compassion in organizational life. Am. Behav. Sci. 47, 808–827. doi: 10.1177/0002764203260211

Kanov, J. M., Maitlis, S., Worline, M. C., Dutton, J. E., Frost, P. J., Lilius, J. M., et al. (2016). Compassion in organizational life. Am. Behav. Sci. 47, 808–827.

Kirby, E. (2007). Book review: reworking gender: a feminist communicology of organization. Manage. Commun. Q. 21, 284–294. doi: 10.1177/0893318907306040

Kirby, E. L., and Krone, K. (2002). “The policy exists but you can't really use it:” Communication and the structuration of work-family policies. J. Appl. Commun. Research, 30, 50–77. doi: 10.1080/00909880216577

Kramer, M., and Hess, J. A. (2002). Communication rules for the display of emotions in organizational settings. Manage. Commun. Q. 16, 66–80. doi: 10.1177/0893318902161003

Ledoux, K., Forchuk, C., Higgins, C., and Rudnick, A. (2018). (2018). The effect of organizational and personal variables on the ability to practice compassionately. Appl. Nurs. Res. 41, 15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2018.03.001

Lilius, J. M., Worline, M. C., Dutton, J. E., Kanov, J. M., and Maitlis, S. (2011). Understanding compassion capability. Hum. Relat. 64, 873–899. doi: 10.1177/0018726710396250

Lown, B. A., McIntosh, S., Gaines, M. E., McGuinn, K., and Hatem, D. S. (2016). Integrating compassionate, collaborative care (the “Triple C”) into health professional education to advance the triple aim of health care. Acad. Med. 9, 310–316. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001077

Madden, L. T., Duchon, D., Madden, T. M., and Plowman, D. A. (2012). Emergent organizational capacity for compassion. Acad. Manage. Rev. 37, 689–708. doi: 10.5465/amr.2010.0424

Miller, K. I. (2007). Compassionate communication in the workplace: exploring processes of noticing, connecting, and responding. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 35, 223–245. doi: 10.1080/00909880701434208

Minguet, B., and Blavier, A. (2018). Formaliser l'intervention collective pour soutenir la résilience individuelle: modèle d'une analyse post-événementielle dans l'accompagnement des décès d'enfants en milieu hospitalier. Le Travail Humain 81, 173–204. doi: 10.3917/th.813.0173

Mumby, D. K., and Putnam, L. L. (1992). The politics of emotion: a feminist reading of bounded rationality. Acad. Manage. Rev. 17, 465–486. doi: 10.2307/258719

Nissim, R., Malfitano, C., Coleman, M., Rodin, G., and Elliott, M. (2019). A qualitative study of a compassion, presence, and resilience training for oncology interprofessional teams. J. Holistic Nursing, 37, 30–44. doi: 10.1177/0898010118765016

Nussbaum, M. C. (2001). Upheavals of Thought: The Intelligence of Emotions. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Pearson, J. E. (1986). The definition and measurement of social support. J. Counsel. Dev. 64, 390–395. doi: 10.1002/j.1556-6676.1986.tb01144.x

Powley, E. H. (2009). Reclaiming resilience and safety: resilience activation in the critical period of crisis. Hum. Relat. 62, 1289–1326. doi: 10.1177/0018726709334881

Putnam, L. L., and Mumby, D. K. (1993). “Organizations, emotion and the myth of rationality,” in Emotion in Organizations, eds S. Fineman (London: Sage), 36–57.

Radey, M., and Figley, C. (2007). The social psychology of compassion. Clin. Soc. Work J. 35, 207–214. doi: 10.1007/s10615-007-0087-3

Roche, A., Kostadinov, V., Cameron, J., Pidd, K., McEntee, A., Duraisingam, V., et al. (2018). The development and characteristics of employee assistance programs around the globe. J. Workplace Behav. Health, 33, 168–186. doi: 10.1080/15555240.2018.1539642

Roeder, A. C., Bisel, R. S., and Morrissey, B. S. (2021). Weathering the financial storm: a professional forecaster team's domain diffusion of resilience. Commun. Stu. 72, 1–16. doi: 10.1080/10510974.2020.1807379

Seppälä, E. M., Simon-Thomas, E., Brown, S. L., Worline, M. C., Cameron, C. D., Doty, J. R., et al. (2017). The Oxford Handbook of Compassion Science. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Shatté, A., Perlman, A., Smith, B., and Lynch, W. D. (2017). The positive effect of resilience on stress and business outcomes in difficult work environments. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 59, 135–140.

Sias, P. M. (2014). “Workplace relationships,” in The Sage Handbook of Organizational Communication, eds L. L. Putnam and D. K. Mumby (London: Sage), 375–399.

Simpson, A. V., and Berti, M. (2020). Transcending organizational compassion paradoxes by enacting wise compassion courageously. J. Manage. Inquiry, 29, 433–449. doi: 10.1177/1056492618821188

Simpson, A. V., Clegg, S., and Pina e Cunha, M. (2013). Expressing compassion in the face of crisis: organizational practices in the aftermath of the Brisbane floods of 2011. J. Contin. Crisis Manage. 21, 115–124. doi: 10.1111/1468-5973.12016

Simpson, A. V., Clegg, S., and Pitsis, T. (2014). Normal compassion: a framework for compassionate decision-making. J. Business Ethics 119, 473–491. doi: 10.1007/s10551-013-1831-y

Simpson, A. V., and Farr-Wharton, B. (2017). NEAR Organizational Compassion Scale: Validity, reliability and correlations. Paper presented at the Australian and New Zealand Academy of Management (ANZAM), RMIT, Melbourne Australia.

Simpson, A. V., Farr-Wharton, B., and Reddy, P. (2020). Cultivating organizational compassion in healthcare. J. Manage. Org. 26, 340–354. doi: 10.1017/jmo.2019.54

Stoverink, A. C., Kirkman, B. L., Mistry, S., and Rosen, B. (2020). Bouncing back together: Toward a theoretical model of work team resilience. Acad. Manage. Rev., 45, 395–422. doi: 10.5465/amr.2017.0005

Strauss, C., Taylor, B. L., Gu, J., Kuyken, W., Baer, R., Jones, F., et al. (2016). (2016). What is compassion and how can we measure it? A review of definitions and measures. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 47, 15–27. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2016.05.004

Tronto, J. C. (2013). Caring Democracy: Markets, Equality, and Justice. New York, NY: New York University Press.

Trzpuc, S. J., and Martin, C. (2010). Application of space syntax theory in the study of medical-surgical nursing units in urban hospitals. Health Environ. Res. Design J. 4, 34–55. doi: 10.1177/193758671000400104

Underdahl, L., Jones-Meineke, T., and Duthely, L. M. (2018). Reframing physician engagement: An analysis of physician resilience, grit, and retention. Int. J. Healthcare Manage. 11, 243–250. doi: 10.1080/20479700.2017.1389478

Vogel, S., and Flint, B. (2021). Compassionate leadership: How to support your team when fixing the problem seems impossible. Nursing Manage. 28, 32–41. doi: 10.7748/nm.2021.e1967

Vogus, T. J., and Sutcliffe, K. M. (2007). “Organizational resilience: Towards a theory and research agenda,” in Paper Presented at the 2007 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man and Cybernetics.

Way, D., and Tracy, S. J. (2012). Conceptualizing compassion as recognizing, relating and (re)acting: a qualitative study of compassionate communication at hospice. Commun. Monograph. 79, 292–315. doi: 10.1080/03637751.2012.697630

Weick, K. E., and Sutcliffe, K. M. (2001). Managing the Unexpected: Assuring High Performance in an Age of Complexity. London: Jossey-Bass.

Williams, T. A., and Shepherd, D. A. (2017). To the rescue!? Brokering a rapid, scaled and customized compassionate response to suffering after disaster. J. Manage. Studies 55, 910–942. doi: 10.1111/joms.12291

Worline, M., and Dutton, J. E. (2017). Awakening Compassion at Work: The Quiet Power That Elevates People and Organizations. London: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Keywords: compassion, organizational compassion, social support, team care, resilience, rationality, emotion work, gender and compassion

Citation: McAllum K, Fox S, Ford JL and Roeder AC (2023) Communicating compassion in organizations: a conceptual review. Front. Commun. 8:1144045. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2023.1144045

Received: 13 January 2023; Accepted: 03 July 2023;

Published: 19 July 2023.

Edited by:

María Dolores Ruiz Fernández, University of Almeria, SpainReviewed by:

Peter McGhee, Auckland University of Technology, New ZealandPatrice Buzzanell, University of South Florida, United States

Copyright © 2023 McAllum, Fox, Ford and Roeder. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kirstie McAllum, a2lyc3RpZS5tY2FsbHVtQHVtb250cmVhbC5jYQ==

Kirstie McAllum

Kirstie McAllum Stephanie Fox

Stephanie Fox Jessica L. Ford2

Jessica L. Ford2 Arden C. Roeder

Arden C. Roeder