- Rhetoric and Professional Communication, Iowa State University, Ames, IA, United States

Introduction: This paper explores whisper networks, which are informal communication networks women use to share information about sexual harassment and sexual harassers in the workplace. Women use whisper networks to share information about people known for sexual harassment or assault. This study offers an innovative approach to studying the nuances and dynamics of sexual harassment and communication in the workplace by focusing on women's experiences in whisper networks.

Methods: To examine these back-channels, I conducted 20 semi-structured interviews with participants who participated in whisper networks in their organizations. Using grounded theory, I established three emergent theories about the purposes whisper networks serve in organizations.

Results: Whisper networks (1) serve as protection in organizational cultures of harassment and (2) help women make sense of their harassment experience through sensemaking. Whisper networks also serve the purpose of (3) identifying harassers because harassers are not readily apparent when entering a new work situation.

Discussion: These findings establish a baseline of theories to explain whisper networks' purposes and offer theoretical and practical implications for future research on sexual harassment, whisper networks, and informal communication networks.

1. Introduction

More than a third of American women have experienced unwanted and inappropriate sexual advances from male coworkers, and 25% of the women polled revealed that sexual advances had been perpetrated by someone in a position of power or influence over their work situation (Langer and Langer, 2017). Additionally, formal reports of sexual harassment to the EEOC increased by 3% between 2018 and 2021 (U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, 2022). However, numbers gathered through official formal reports are often skewed because in many places it is unsafe for women to report sexual harassment through formal organizational structures [Feldblum and Lipnic, 2016; Dougherty, 2022; U.S. EEOC, 2022; National Sexual Violence Resource Center, n.d.]. For example, when women report harassment, they are often overlooked, their morals may be questioned, and they often face reputational harm (Feldblum and Lipnic, 2016).

It is impossible to fully understand issues around sexual harassment by looking at the numbers from national polls and reports, because formally reporting sexual harassment often places women in precarious positions where they may not be believed, may face reputational harm, and may even be transferred to another department or demoted (Bergman et al., 2002; Cortina and Berdahl, 2008; Feldblum and Lipnic, 2016; Dougherty, 2022). Many strides have been made in developing sexual harassment policies and training, but the rising rates of sexual harassment show a need to develop a more nuanced understanding of organizational cultures and communication. To better understand sexual harassment and communication, I examined whisper networks, which are the informal communication systems that women use to warn other women about people known for hostile sexism and sexual harassment (McDermott, 2017; Meza, 2017). Whisper networks operate under the radar and understanding this network of informal communication helps us better understand complexities of sexual harassment in organizations.

Women create whisper networks to support each other and share protective information about potentially dangerous colleagues. Communication in whisper networks is not necessarily whispered—it is more complicated. Whisper is a metaphor for information given behind the scenes or without the knowledge of those who hold power. The phrase “on the down-low” is a colloquial but descriptive way to think about how communication works in whisper networks. When people share information in a whisper network, there is an unspoken expectation that the listener will keep the information secret “on the down-low” and will only share that information with trusted others. Whisper networks constitute alliances where secrets are passed privately by women to warn others about known risks of sexual harassment. They function to fill gaps in problematic reporting systems. Kaplan (2017), a reporter for Columbia University's daily newspaper, shared an example of how whisper networks regularly function:

“Hey, I know your're in a club/show/class with [name]. Just be careful; he's not a great guy.” At that moment, sometimes they'll offer a hug. Sometimes it's a knowing nod, a flash of recognition in their eyes. Regardless, the message is loud and clear: Stay away. He might hurt you. I want you to be safe. He's done it before, and he'll do it again. You hear this and ask no questions; you file it in your brain, and then you map out which groups you'll now avoid and when you'll stop going to a particular dining hall for lunch. You strategize (p. 1).

In this example, the woman shares information about a known harassment risk using an indirect warning and non-verbal cues. The person receiving the message understood that there was a risk without being told explicit details.

Many scholars have shown that harassment in organizations is a communication problem (Dougherty and Smythe, 2004; O'Leary-Kelly et al., 2004; McDonald et al., 2011; Dougherty, 2022), and decision-makers in these cultures may not hold the perpetrators accountable and can hide the harassment from work records. Formal reports about sexual harassment rarely work in favor of the people willing to talk about them (Feldblum and Lipnic, 2016), so often, this communication goes unseen and understudied. Using whisper networks to further understand communication that has heretofore been highly overlooked is essential for organizational, political, and management leaders who desire to make sexual harassment policies that make a difference. My research on whisper networks establishes a baseline to understand how whisper networks function in organizations and allows for new insights into the purposes whisper networks serve.

2. Literature review

Whisper network research is important to our understanding of organizational communication because it examines what happens under the surface. Whisper networks, notably, exist to solve problems created by other forms of communication. This study examines information shared between people in an organizational context and how whisper network communication fills spaces where protection is necessary due to organizational cultures or oversights (Clair, 1999; Deetz, 2000; McDonald et al., 2011; Clair et al., 2019). Organizational cultures are built through communication, including what is assumed normal, acceptable, or permissible. People sustain organizational cultures through communicating and working through their experiences (Dougherty and Smythe, 2004), but little research has been done about how organizational cultures are built from hidden communication.

2.1. Communication

When women cannot talk about sexual harassment in their organization, it perpetuates the idea that sexual harassment doesn't exist or isn't that bad (Ford et al., 2021). Additionally, sexual harassment can be overlooked or silenced by organizations claiming to have strong protections against sexual harassment (Dougherty, 2022). When harassing behavior is normalized, it can also cause women not to share their accounts of sexual harassment because they don't seem “that bad” compared to other stories (Robillard, 2021). Women need trusted communication channels to protect themselves and others and validate that their experiences are indeed sexual harassment (Scarduzio et al., 2018). However, stories do not have to be ‘that bad” to show up in a whisper network.

Communication networks are created when messages are shared between nodes (the individuals involved) through edges (the relationship between the nodes). A network tie, meaning communication between two or more participants shared through a communication edge, is a fundamental structural concept in communication networks (Hazleton and Kennan, 2000). The network is created when messages are passed along communication edges between multiple nodes.1 Even if the information is received unintentionally, that woman becomes part of the whisper network (Carter, 2021). Women in whisper networks may or may not know each other, but a network edge is created about the risk of sexual harassment. Whisper network edges are created through the sharing of whisper network messages.

2.2. Sexual harassment

Sexual harassment is a way to maintain toxic power dynamics (Dougherty, 2022). In fact, “sexual dominance, coercion, and control; sexual objectification, touching, unwanted attention, gendered teasing, put-downs, and humiliation can all accomplish these ends” (Hershcovis et al., 2021, p. 3). In 2016, the U. S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) recovered $164.5 million for allegations of sexual assault (Feldblum and Lipnic, 2016), and while the bottom line is important in organizations, it is not the only important loss. Sexual harassment in an organization threatens a person's sense of community and belonging. Even the threat of harassment affects one's sense of community and safety (Gilligan, 1982; Svoboda and Crockett, 1996). Beyond the harm that comes from sexual harassment incidents, there is a risk that reporting will amplify the social and emotional damage to the target by a harasser.

2.2.1. Targets

Sexual harassment comes at a steep cost to targets. They experience mental, physical, and economic harm. Additionally, where sexual harassment is visible, organizations suffer from decreased productivity, increased turnover, and negative reputational ramifications (Feldblum and Lipnic, 2016). The emotional toll reported by targets of sexual harassment is high. “Among those who have experienced unwanted workplace-related sexual advances, 83 percent say they're angry about it, 64 percent felt intimidated by the experience, and 52 percent say they were humiliated. About three in ten felt ashamed” (Krackhardt and Kilduff, 1990, p. 1). Sexual harassment causes emotional harm, but there are additional potential costs if a target decides to report the harassment formally.

The emotional cost of reporting can be overwhelming and often ineffectual. Reporting sexual harassment can be intimidating and emotionally draining. In most cases, reporting hurts the person who reports more than the reported person (Bergman et al., 2002; McDonald et al., 2011). By fighting sexual harassment using formal reporting systems, women risk their relationship with the organization (Dougherty, 1999) and reporting puts women's interpersonal relationships at risk. Even with systems supposedly built to keep women safe, sexual harassment is a problem for organizations. A sexual harassment experience alters a woman's ability to move through her daily world. It can affect her self-identity (Shupe, 2020). It puts her in a position where she must decide if what she went through is real and worth reporting (Hlavka, 2014). She knows that little may be done to keep her safe, even if she is believed. This puts the target in a position where she feels the burden of sexual harassment and understands the potential for reputational harm and broken relationships. Women need a way to work through their sexual harassment experience and regain some power over their narrative.

2.2.2. Bystanders

Bystanders or observers respond to sexual harassment depending on the context in which they witness it. If a bystander sees sexual harassment as an ambiguous action or does not feel responsible for saying something, they are less likely to intervene (Bowes-Sperry and O'Leary-Kelly, 2005). Additionally, the power differential between the harasser and the harassed often extends to bystanders because of the multiple exigencies that make it hard for targets to report (Keyton et al., 2018). Manning (in Keyton et al., 2018) discussed the difficulty of stepping in during social situations.

The only thing I felt I could do was offer vague warnings to others to stay away from possible harassers. Even then, it is risky to suggest to a colleague that someone they might have to work with could be sexually aggressive. It puts both me and those I originally saw being harassed in danger of retaliation (p. 673).

Like individual targets of sexual harassment, bystanders need to be able to contextualize the situation around the harassment. Bystanders can be important in stopping sexual harassment, but organizational leaders should not assume that people automatically know how to stand up against sexual harassment (Dougherty, 2017; Keyton et al., 2018). Contextualization is as important for bystanders as targets, and this research into whisper network communication adds to our contextual understanding of sexual harassment.

2.2.3. Organizations

Organizational cultures are built from the larger national dialogue, meaning maintaining cultures of harassment can happen simply by changing nothing. Perpetrators don't need to establish a culture of harassment because it is maintained by those who take no action to stop it. Historically, organizations needed an extra push to address how women were treated (Cortina and Berdahl, 2008). Sexual harassment is insidious, and organizations where sexual harassment is normalized can obscure women's ability to understand their experiences or seek protection. When sexual harassment happens consistently, it becomes normalized; once something is normalized, it is no longer seen as harassment (Dougherty, 2009). Members of organizations with high levels of sexual harassment may conclude that sexual harassment is simply “how things are” and brush off the unwanted advances as just how things work. When sexual harassment is viewed as normal, there is little chance that organizational authorities will feel obligated to create policy changes or provide opportunities for better training (Cortina and Berdahl, 2008). When an organization does not protect the people, who live and work in the culture, other systems surface to help transfer knowledge because of the understanding women share about what is and is not worthy of calling sexual harassment (Dougherty and Smythe, 2004).

3. Methods

For this study, I chose a qualitative approach to generate rich insights on an understudied phenomenon and to focus on each individual's experience. I gathered one-on-one interviews with participants who had experiences with sexual harassment and whisper networks. To recruit participants, I used a call for participants that included the definition of whisper networks and explained the time commitment for the interviews. I recruited participants through social media by posting a call for participants to my personal Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram pages. Friends, family, and colleagues re-posted my call on their social media accounts. I also used snowball sampling by asking participants to recommend others who might want to contribute their stories. Snowball sampling is often used when the research examines hidden populations or populations that have a reason to shield themselves from public ridicule (Browne, 2005). Whisper networks, by definition, are hidden networks, so I asked participants to share my information with others they knew in their whisper networks. Snowball sampling is useful because it expands the potential participant pool by finding participants that were not reached by the researcher's original call and who might be difficult to access without the intermediary participant (Tracy, 2013). Participants were often aware of others in their networks who had similar experiences and were willing to share my call for participants. Most participants referred to their family members and friends who had participated in whisper networks instead of people from the same organizations.

I conducted 20 semi-structured virtual interviews by phone or Zoom, depending on participant preference. The age of participants ranged from 18 to 64, with almost half of the participants falling between the ages of 35–44. Participants were primarily white. One participant was Latinx, and one did not report their race. Educational levels varied between high school graduates and PhDs. A majority of participants held master's degrees. The lean toward highly educated participants may come from an unspoken rule about participating in research, and from higher education systems having significant power differentials in the hierarchy (Thomas and Kleinman, 2023). Even though a majority of participants held master's degrees there was still a strong range of educational levels.

Participants varied in marital status, including single, married or partnered, divorced, and widowed, with the majority reporting that they were married or in a domestic partnership. Most participants were employed full-time, but others were self-employed, employed part-time, or currently a student. Participants came from various occupations, including the service industry, business, law, STEM, education, banking, veterinary medicine, and art. They held various positions in their workplaces, including executives, managers, productions, marketing, assistants, analysts, accountants, attorneys, professors, and human resources. Additionally, participants came from various economic backgrounds with household incomes ranging from zero to over $250,000.

All interviews were audio-recorded and later transcribed. I used a semi-structured list of questions to stay focused on whisper networks while allowing participants to elaborate on their stories. I began each interview by asking participants about a whisper network in which they had participated. Participants were also asked questions such as: How did you know you could trust someone with whisper network information? What words or phrases let you know someone is sharing whisper network information? To maintain privacy, all pseudonyms were used for all participants.

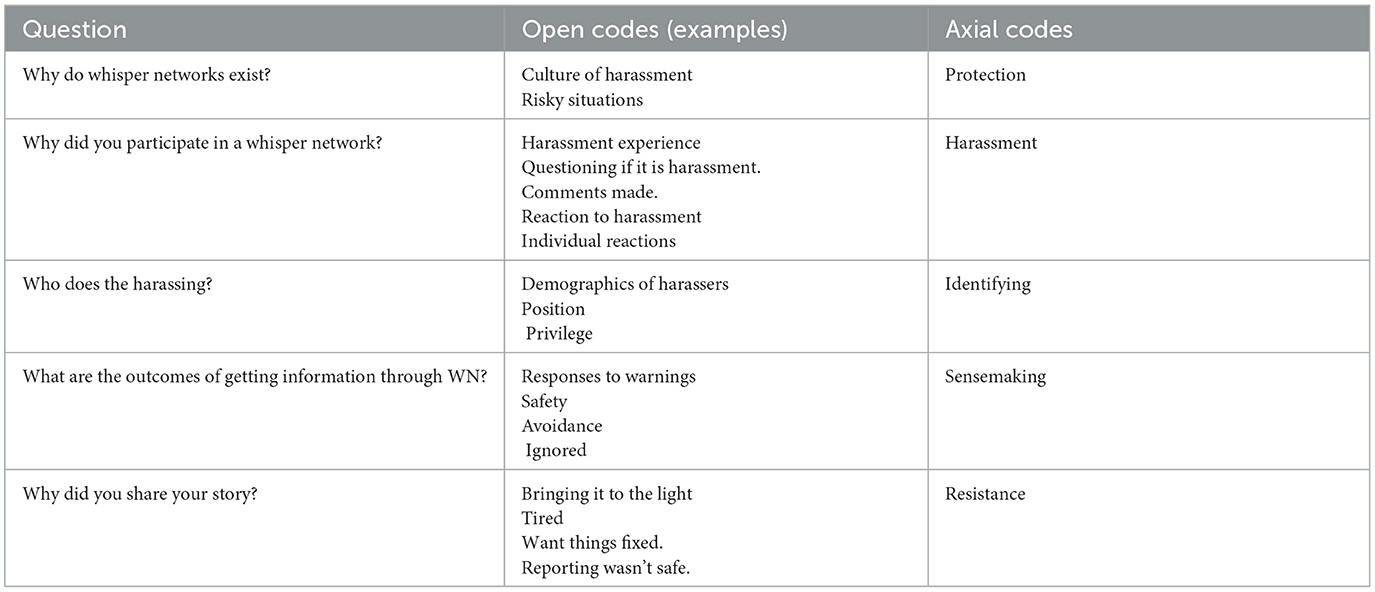

I examined the data using a grounded theory (Glaser and Strauss, 1965; Corbin and Strauss, 1990; Charmaz, 2006; Charmaz et al., 2018) coding structure where I added notations to each line of the interview to look for repeated patterns and ideas. Categories began to emerge, and I used constant comparison of concepts and categories to further refine the interpretation of the initial codes. As I identified categories that needed deeper inquiry, I added questions to clarify and deepen the emerging theories. I gathered interviews until theoretical saturation was evident and the categories and codes remained consistent. I evaluated relationships between categories and codes to look for theories about how whisper networks work, how they develop, how they compare to other networks, and why they happen under certain conditions (Saldaña, 2021) (Table 1).

Grounded theory allowed me to focus on listening to women's stories and examine how whisper networks create social relationships, group behaviors, and social processes (Chun et al., 2019). This paper does not use quotes from every participant. Instead, I use examples that best exemplify each theory. I drew several examples from one of the final interviews because Claire's stories offered clear insights into the theories about the purposes that whisper networks serve.

4. Results

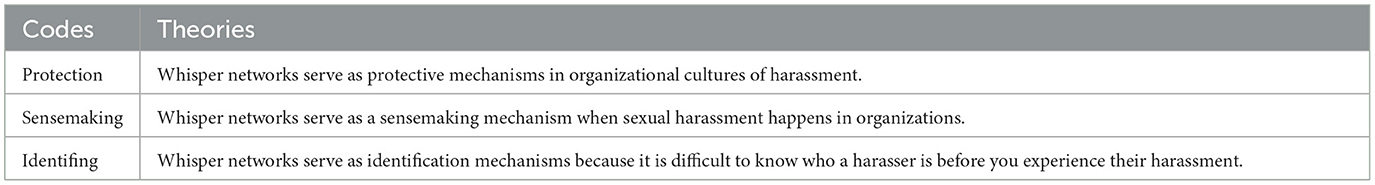

I will begin with an overview of purposes, as seen through how a whisper network functions. Emergent theories explain “the phenomena in terms of how they work, how they develop, how they compare to others, or why they happen under certain conditions” (Saldaña, 2021, p. 315). Table 2 shows how the final themes were used to develop theoretical explanations for purposes whisper networks serve in organizations.

The first theme addresses the need for protection in cultures of harassment. Cultures of harassment are created or maintained in environments where sexual harassment is built into the organizational culture (Chira and Einhorn, 2017; Breger et al., 2019). Whisper networks protect women from potential harassment when there is a culture of harassment in their organization. Two subthemes explain ways that organizations create or maintain these cultures of harassment. In a culture of harassment, sexual harassment is not taken seriously, and reporting sexual harassment is risky. This data shows that another purpose of whisper networks is to help participants make sense of their experiences and find support. Finally, whisper networks can help people identify harassers because it is impossible to know who participates in harassment without experiencing harassment or without help from the whisper network.

The purpose of whisper networks can most easily be seen by looking at how they function. A function can broadly be described as what something does, while purpose is more easily understood as the function's reason. In other words, the purpose is answered by asking why women share information about sexual harassment in whisper networks. For example, whisper networks function to protect, inform, bypass reporting systems, encourage, dismantle silence, and uncover harassers. Whisper networks' purpose(s) can be answered by questioning why they perform the functions of protecting, informing, resisting/bypassing, encouraging, and dismantling silence. Data from these interviews indicate that the purposes of whisper networks are 2-fold—whisper networks help women feel/be safer at work, and they help women feel less alone in experiencing sexual harassment.

Interestingly, nearly every participant shared their experiences of sexual harassment as a way to frame their experiences with whisper networks. The cultural pervasiveness of sexual harassment is why women often share sexual harassment information inside whisper networks. To build a stronger framework for the analysis, I will share several participants' descriptions of their experiences with sexual harassment to establish that cultures of harassment exist. Second, I examine three preliminary theories about the purposes whisper networks serve in organizations (protection, sensemaking, and identification) that either fulfill the purpose of helping women feel safer at work or feel less alone as they make sense of harassment.

4.1. Theory 1: whisper networks serve as protective mechanisms in organizational cultures of harassment

Women need ways of protecting each other and themselves when there is an organizational culture of harassment. Protection is the main purpose that whisper networks serve, so the examination of protection is longer than the other two theories combined. It was important to frame protection with an explanation of participants' experiences with sexual harassment, an examination of how cultures of harassment are built and maintained, and the features of reporting (not taken seriously and risk) that necessitate the use of whisper networks.

Cultures of harassment are created when people think harassment is acceptable or funny, and they are maintained by leaders who remain silent when they receive information about sexual harassment or when they let harassment slide by without comment or correction. Cultures of harassment can also be maintained when reports of sexual harassment are not taken seriously or when a woman is at higher risk if she reports than if she stays silent. Women need protection from sexual harassment in organizations because organizational cultures still largely hurt women who report harassment through formal reporting systems. The stories they shared confirm and expand earlier research about cultural foundations that support sexual harassment, the amount and amplitude of sexual harassment in organizations, and how little their willingness to report through formal structures mattered in keeping other women safe.

4.1.1. Experiences with sexual harassment

Several participants reported that they first used whisper networks because of sexual harassment at their first jobs, but their context for understanding sexual harassment began early in childhood. Others explained that because sexual harassment is a cultural expectation, they were unsure their experiences were worth reporting. Whisper networks are necessary because the risk of sexual harassment starts early, and the need for protection is undaunting. Carmen pointed out that she had been on watch since she was a little girl.

I think, as a girl, you learn pretty quickly. We hear comments like [about harassers], “They make you feel yucky” it's kind of how we explain stuff to the girls, you know. Just like, “They make you uncomfortable,” and you're just like, “That's weird.” I mean, you know, I think especially for girls, you just, unfortunately, you get used to it sometimes.

Carmen's understanding of sexual harassment was shaped in her childhood and led her to be vigilant throughout her life. Her experiences exemplify what several participants explained about how cultures of harassment had been part of their workplace experiences for as long as they had worked. Carmen shared her experiences with sexual harassment at her first job as a waitress at a steakhouse when she was fifteen and talked about how three adult managers continuously made comments.

There were three male managers, there was like a general manager and then the assistant managers, and they would make weird comments. And it was just like that awkward like, “Oh, that's weird,” you know, but no one said anything. Like no one did anything. We just…I never even told my parents because I was just like, that's weird…like weird old pervy men.

The older managers would make comments, but since no one did anything about it, she and her co-workers assumed they had to deal with the harassment. I asked her how the whisper network helped. She shared,

If you needed to request time off, you had to go in there, and it was always like, “Take someone with you,” or they would make comments like, “Oh, you want that day off? Like you want to come to the office with me?” Like, haha, just joking.

Participants also talked about how they have “just always known” that girls need to stick together. Claire pointed out that she learned whisper network information because people with older sisters shared information. Her friend's “sister [had] graduated from college, so there was like knowledge being passed down. We learned to share whisper network information to keep each other safe.” Culture influences how we communicate about sexual harassment (Brickell, 2006; Hlavka, 2014), and when you have been in a culture that supports sexual harassment since childhood, it can be difficult to assess if what you are experiencing is sexual harassment (Dougherty, 2009).

Participants also talked about not knowing if they had participated in whisper networks because the information was more like an open secret, meaning that it was something that everyone just knew. While the information is rarely whispered, it is shared quietly, privately, or through coded messages. For instance, Carmen said, “It wasn't like a whisper, in a way where, ‘Hey, don't do this,' you know. ‘Just kind of keep it on the down-low.”' Information is shared secretly, but often among women, the information is an open secret. For example, Jenny said her harasser had an open file, and his harassment was not a secret, but there wasn't enough proof, so he was not held accountable. In Claire's story, the harasser was close to retirement. Everyone knew that the harasser was close to retirement, so the harasser would not be accountable for their actions. Open secret/no accountability situations force people to use whisper networks to protect others and are endemic to many different organizational cultures of harassment. Many organizations still maintain a strong culture of harassment (Chira and Einhorn, 2017; Breger et al., 2019). These interviews corroborate research that says sexual harassment reporting is problematic for those who have been sexually harassed and for bystanders (O'Leary-Kelly et al., 2004; Feldblum and Lipnic, 2016). The interviews also confirmed that the problems with sexual harassment are built into organizational systems (Dougherty and Smythe, 2004; Hertzog et al., 2008).

4.1.2. Cultures of harassment

Cultures of harassment are built and maintained when the organization's culture is built around a dominant male experience, and the status quo is maintained when women are labeled as problems if they speak up about sexual harassment. Claire said she was expected to put up with harassment to be part of the team. She talked about the whisper network when she was a female graduate student in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, & Math). Claire felt she needed to show solidarity with her harassers to succeed in her field. She understood that she was experiencing sexual harassment but thought she had to comply. She had one colleague from graduate school with whom she continued to share whisper network information. They shared a whisper network in graduate school and have continued to work together on projects.

My grad school sister and I collaborate, I was finishing up a grant just this morning, and she goes, you know, the two of us could have raised hell about just the comments or, you know, we're the ones driving people home after they were drunk. But we were “cool,” and so we're very successful tenured professors now. We were always in the room. This is an awful thing to think about. Just that level of sexual environment we were in all the time.

Claire refers to her whisper network throughout the following excerpts as “we.” “We” is about other women in her cohort, especially the friend she still collaborates with. She believed that if she had reported sexual harassment, she would not have had the opportunity to succeed. Her harassment experience was normalized as quid pro quo (Dougherty, 2001). She talked about a mentality that women must conform to or put up with sexual harassment if they want to succeed.

There was a guy in our program who was always pushing. Right? So, it is complicated for a woman in STEM because if you're not in the room, you're not in the papers. If you're not in the room, you're not in the projects. And if you are someone who fusses or makes you know, whatever, then you're not going to be in the room. So that's always really…it's a hard line for women to walk.

She contextualized her experience with one colleague who regularly harassed her by pointing out that he (and others) had multiple sexual exploits. “A couple of the guys who, you know, they screw around while they're out at field sites. Like, one of them screwed a postdoc when it was overseas, you know, married guys. Right?” When she shared her side note about “married guys”, she looked at me with a half-smile and nodded. Clair continued by explaining that she could not report because if she had reported it, the university would have taken her off the projects to “protect her,” but that would have also been detrimental to her ability to succeed.

He and I have written two papers together, like whatever. He was always pushing the line, always. But it's a joke, right? Always just joking, like, “Yeah, you know, if you guys do XYZ, I'll totally help you out with your analyses.” No, come on, man, because…Oh, I'm just kidding, you know, whatever that kind of stuff. Right. And, and push that line and push that line, where you're like, it's exhausting and, but it's also normalized. And I remember I was pregnant during one of these things, and he's like…come on, hug me goodbye, and it was just awful. It wasn't as easy to sort of live with that kind of stuff.

This example shows a culture of harassment because the harasser expected the women to laugh off his sexual harassment. He thought it was no big deal, and neither should they. This type of story confirms other research about workplace sexual harassment that women and men do not view sexual harassment the same way (Dougherty and Smythe, 2004). That difference in standpoint was difficult for Claire to navigate. In addition, the culture of harassment was maintained by a departmental structure where she could not report without career-altering consequences. She explained the circumstances that allowed him to prosper while the women she worked with continued suffering.

He had a powerful, hot-shot advisor, and we were pretty aware of that. Well, we didn't think we'd ever get protection from the school if we said that we didn't like how he talked to us. Plus, it means that he was all he was a guy's guy, so we would definitely not be on projects and stuff, so it just sucked. Right? So, we did two projects together, which eventually we had papers on over the last 10 years. And it was always like, “Hey, we're gonna do a Skype meeting…turn your cameras on. I wanna be able to see your tits…you guys are beautiful today.” So that was a normal call. Right? “Oh, I'm just joking. Don't be so sensitive,” But you know, we just hated it.

Claire said that women in her graduate cohort maintained a whisper network, shared important information about how to succeed in a culture of harassment, and helped her cope with the sexual harassment, but looking back on her experiences in graduate school, there was still pain. The whisper network was filling the two stated purposes of whisper networks. It helped Claire make sense of her experience and helped the women protect each other. She described the persistence and hostility of her harasser and how the system protected him by ensuring that they would have been excluded from important papers and projects if she or her friend reported. Claire explained the culture of harassment further. “But that was also women in science. You're stepping into such a boy space. Even now, there's a certain amount of pay-to-play, right? You tolerate their hyper-sexualized jokes, or they're getting drunk or whatever else.” Pay-to-play is a term used in gaming culture, meaning that if you want to be good at a game, you must pay for perks continuously. She understood that she could report but felt stuck in a culture of harassment and expected quid pro quo.

She explains, “Oh, I'm sure if I shared that during grad school, you know, [the university] would have raised holy hell. The problem is that I also would have been viewed as a difficult creature.” She could have reported this culture of harassment, but it would have cost her because it would have redefined what type of person she was and identified her as difficult. The culture of harassment went even deeper for Claire.

The whisper network shared information that helped women in the department “read the room” correctly and helped them survive the harassment without giving up their opportunities for success. She explained that the leaders of the department maintained a culture of harassment by implying that the female students were the problem instead of the harassment.

We never felt safe protesting locker talk. Well, no kidding. Look what happens, you know. One of the lead, big honchos there was fired, but he was setting the tone. We definitely read the room correctly, you know, so they would have said, “Oh, these girls have problems, they're difficult,” so, you know, it's probably good, we didn't make a fuss. It was a challenge.

Using the whisper network helped them survive the harassment without giving up their opportunities for success. Claire was not the only participant who talked about the “boys club”. Victoria shared an experience where the “boys club” network upheld a culture of harassment by not sharing information that could have kept her safe. On the contrary, her colleagues prioritized protecting the harasser.

Well, at my first university, it was my first job as an assistant professor on the tenure track, and there was a senior man in the department who was pretty awful. He regularly sexually harassed people, including me…. And I ended up being really angry with a number of my male colleagues who had enough power that they could have protected me. They could have told me from the beginning that he was a problem.

Victoria points out that she had colleagues that could have protected her. They had power, and they knew about the problem, but in a culture of harassment, the protection and privacy of the harasser is often valued over the protection of sexual harassment targets. Every participant shared examples of sexual harassment and how it was perpetuated in their organizations through cultures of harassment which are upheld when (1) harassment is not taken seriously, and (2) reporting is risky.

4.1.2.1. Harassment is not taken seriously

Broader organizational issues create the purposes in which whisper networks become necessary. For example, when harassment is not taken seriously, women use whisper networks to share information and protect one another from sexual harassment. In a continuation of Claire's story, multiple women found each other through whisper networks and submitted a formal sexual harassment report about the man who had harassed Claire relentlessly throughout graduate school. Their university would not take action on the reports. At a conference, one of the women in Claire's whisper network shared details about the case, and Claire told her that this man had sent many inappropriate comments in private messages. Her friend asked Claire if she would be willing to share the private messages the man sent. Claire went through the online chats and added evidence to what the four women were reporting. After sharing information with the Title IX office, she received a phone call to discuss her report. She expressed anger at their lack of action.

The Title IX officer called me to talk through it, and I just laid into him. I was like, “Listen; I am furious that I have to do this because if you guys would listen to your four Ph.D. professors—women who have come forward—if you listen to the women in your organization. I shouldn't have to do this. Now you guys are a bunch of assholes.” I just said that flat out. He was like, “Because we need your hard data.” I was like, “You have four witnesses. What else do you need?” He's like, “Well, you know your screenshots tell a pretty interesting story.” Like, “Yes, they do.” But it tracks, whatever. Anyway, they didn't fire him. They gave him an ongoing one-year contract to teach in a different department.

The Title IX office and the university did not take reports from multiple female faculty members seriously. Even with written and verifiable evidence, the harasser was given a proverbial slap on the wrist and moved to a different department. Whisper networks will continue to be necessary for the women around him because the harasser is now simply working with a different group of people who do not know about his past harassment.

Another participant, Everly, talked about the graduate student whisper network and how it helped her find others who had noticed the harassment of two professors in the department. When students decided to make a more formal report, it was not taken seriously. She said that the group tried to bring it up with “other professors, like with like the chair, or sort of like the people with power to do something, they pulled me and other students who have similar problems [into a meeting].” In the meeting, the department leaders said, “those professors are retiring. You know, this year or next year, so it won't be a problem for much longer,” or “thank you for telling me. We already know we can't do anything about it. They're set up to retire.” However, she said that,

The professors didn't actually leave because then they were emeriti and would still teach classes. And so that was one of the reasons why I felt it was important to keep participating in that whisper network so, like, even if graduate students weren't signing up to, like, be advisees, with a few professors who retired, like they would still take their classes and could still have, you know, negative interactions with them.

Her interactions with the department taught her that sexual harassment would not be taken seriously and showed her that whisper networks were important because they were the only way she felt she could keep other graduate students safe. Everly also shared an experience she had during a Title IX training where graduate student questions about sexual harassment were not taken seriously.

It was during Title IX training. And a graduate student asked very, honestly, genuinely like, “How do you protect yourself against harassment and Title IX violations when you're at a conference, say, and you're trying to like make a professional connection? And, you know, a panelist asks you out for drinks, or asks you out to dinner, or asks you to go to their hotel room to talk more about the topic?” And the female professor said, “Well, you know, we all know who…you know there's a list, we all know who's on. So just don't, you know…know who's on the list and just don't interact with them. Don't let yourself get in a sticky situation.” That's super problematic. And the graduate student asked, “Where's the list? How do I know about the list?” The professor was like, “We already know, and if you don't, and you're stupid, you are responsible for it happens to you.” But that was kind of how things were approached. It was like you…like it's your fault if you get into a weird relationship with the professors, and you don't know that they're exploitative or predatory or whatever.

Everly's experiences at her university built on one another to solidify her belief that the whisper network was a necessary communication network because the organization would never take graduate student safety seriously.

Jessie's story is a particularly strong example of how her job did not take sexual harassment seriously. She talked about her experience in the service industry when someone fired for sexual assault was hired back within 6 months. Jessie first explained her colleague's experience with harassment to share the story.

The guy came into the cooler and then just like cornered her and kissed her straight on the lips. It was like very, very, very creepy and very uncomfortable. Luckily, he was fired, but after but six months, he got hired back in the same position that he was in. We got a warning before he got hired again, and management just told us, “Do not talk to him, like don't give him any weird ideas.” It was like we were somehow giving him weird ideas!

I asked Jessie to tell me more about how the man got rehired. She told me the kitchen manager checked with her before re-hiring the man. But her protestation was not taken seriously.

He asked, “How would you feel if I hired this guy back? I thought that he was joking, so I just started laughing. But he was like, “No, but seriously….” I was like, “I would literally hate you. He put so many women in situations that made them unbearably uncomfortable, and after I got off work, I could see the look in his eyes.” But the kitchen manager was like, “He doesn't need any training.” I can only say what I can say. But the kitchen manager hired him anyway.

The harasser's previous experience as kitchen staff and the convenience of the hiring manager outweighed the safety of the women he worked with. Jessie turned to the whisper network to help other women at her company stay safe.

When he got hired back on, I immediately talked to the servers and front-of-house workers, like, “Hey, Sis, I don't want this to happen to you. We don't want it to happen again to any of you, so like, just stay out, don't talk to him.”

Participants gave ample examples of how their organizations did not take harassment seriously. In many cases, everyone knew, but nothing was done to protect them or hold the harasser accountable, so participants protected each other by sharing information through whisper networks. In Jessie's experience, she made a purposeful whisper network because she already knew that the man was a harasser.

4.1.2.2. Reporting harassment is risky

Whisper networks are necessary because it can be risky to formally report sexual harassment because of the time it takes, and the risk to the reporter because of retaliation, gossip, or mental health. The amount of risk a woman perceives when they think about reporting comes from a variety of factors such as self-doubt (O'Leary-Kelly et al., 2004), overlapping marginalization (Keyton et al., 2018), organizational hierarchy (Keyton et al., 2018), and (non)support from others they talk to (O'Leary-Kelly et al., 2004). The following examples show the different levels of risk women felt for reporting or fighting back against harassment.

Gloria, was physically assaulted and sexually harassed but could not get help from her institution, and her harasser was not held accountable. She went to the director of graduate studies, her department chair, people in the graduate college (2 times), and the Ombuds office (3 times). These entities were in the reporting structure, but each time Gloria reached out for help, the people who should have helped her be safe made the situation worse.

There have been so many grievous abuses in my nine years as a graduate student. And every time I go to the university…nine times out of ten, the university makes the situation worse. I'm told it's my fault…There is no response. There is no accountability. I remember one time I went to the Ombuds office, and they said, “Well, what do you want to get out of this?” And I'm like, “Accountability for the person who has done this.” And that was just not something that registered with them.

Gloria experienced inaction from several departments when she tried to report, which maintained the culture of harassment, but she also faced a bigger risk when she tried to tell her immediate supervisors.

Yeah, um, I was physically assaulted by a professor in [name of department]. And I shared that with my advisor, who was a woman and was the program director at the time. I also shared it with the department chair, who was a man. And their responses were, “It's your fault.”

Gloria reported to her supervisors but quickly realized she would not receive help. It was doubly risky because she was also blamed for being the instigator of her sexual harassment. Gloria's story is a prime example of the claim that every woman in her status as a woman has experienced the accusation of being an active agent in her own objectification (Walsh et al., 2017). Gloria experienced sexual harassment but was viewed as an active agent in her own assault. Gloria's story is an example of multiple cultures of harassment that come from inside departments and is supported by her entire organization's culture of harassment and lack of accountability. She wishes that someone had warned her. She questioned herself after being assaulted and wondered if having a whisper network could have helped her handle things differently.

I often wish I'd known, you know, if somebody had warned me about [assaulter] then…I certainly would have handled them differently because I would have made a formal complaint to the university rather than just telling. I don't know if that would have done anything, you know. Maybe I should have charged him with assault. So, I do it [participate in whisper networks] because I want people, like I said, to be armored or to be aware. And to not be, oh my gosh, this is my fault, you know?

Gloria feels like participating in a whisper network could have helped her avoid harassment and know what to do after the experience. She faced the consequences women often fear when reporting. Sexual harassment reporting feels risky when a woman must juggle an endless array of questions in her mind. She may wrestle with her belief that there will be a social and emotional fall-out of reporting through official channels, so women turn to whisper networks to share information. Beyond the risk of maintaining an educational opportunity or a job, another risk of reporting is the emotional toll on the person who has been sexually harassed.

Women face an emotional toll when sexually harassed, which continues while deciding what to do (O'Leary-Kelly et al., 2009; Feldblum and Lipnic, 2016). Leah was sexually harassed while in graduate school and found out about other women who were being sexually harassed. She received information through the whisper network, and having the information made her feel responsible for protecting others. “The information came naturally, like through conversation. And then I realized this person has some connection to this inappropriate faculty member…then I felt it was my responsibility to share some of that.” She used whisper networks because she felt responsible for keeping other women safe. Once she knew of others who had been hurt, she decided to report them, which caused further emotional harm. Leah explained that there was an emotional toll because the investigation was lengthy. She had learned through her whisper networks that this person had a long history of being inappropriate, and she had been part of the investigation for over a year. It was ending, and she felt frustrated about how long it took. She talked about the emotional toll of getting through an investigation.

I mean, it has just been a, you know, kind of a slap on the wrist kind of situation where…and it's very disheartening. I recently finished this investigation, which was almost a year-long process. And it was emotionally, like, hard to go through. And at the end, you know he…the report was just like, yeah, this probably happened, and this person is, you know, has some history of being inappropriate and not understanding boundaries.

For Leah, the emotional toll was 2-fold. The process of reporting and investigating sexual harassment was long, and afterward, the organization weakened the terms they used to describe the sexual harassment experience. The phrasing “probably” and “some history” downplays the severity of the harassment experience. Near the end of the investigation, Leah received a phone call asking what she thought should happen to the harasser. This phone call caused more emotional stress.

The chair of the Ph.D. department called me and asked if I felt the person should be fired. And I said, “I honestly don't know,” and “I don't want to be part of that,” you know, “Don't put that on me.” And she said, “Yeah, that makes a lot of sense.” She just wanted to get my input about what I felt should happen. And I said, “You know, I do think that this person has some issues with how he engages with students, and I can only imagine how that might look with students who have, you know, even less power than I did.”

Leah was almost finished with her Ph.D. when she decided to make the report, so she felt like she had some footing as a near-equal. She felt reporting was risky but worried about the women who remained or later entered the department. She was also concerned that her harasser would twist the story to make her look like the villain.

It actually took me a full year to report it because it's just, it's hard to make that decision. But when I did, I was already a faculty member somewhere else, so there was no fear that he could harm me in any way. But even so, it was still really emotionally hard and nerve-wracking, just in general. And I did have that fear that he was… he can twist the story so that it turns out he's the victim, and I'm like, I don't know some sex-crazed person or something.

Leah faced the emotional cost of the length of the process, the responsibility she carried when asked for her input, and the possibility that her story would get twisted by the perpetrator to make her look bad. However, she also talked about how the whisper network needed to be part of the process because there was a strong risk that the perpetrator's punishment could leave him in a situation where women had to interact with him. She had made a complaint, and “There was an investigation, but it was one of those situations where there were no witnesses, and no, you know, video or audio or anything like that. And so, he remained in the department.” The whisper network was important because even when someone takes the risk and reports, they still have the strong potential to work with the person they reported.

The examples in this section show women's lived reality when dealing with sexual harassment and examine the purpose of whisper networks as a protection network in cultures of harassment when harassment is not taken seriously or when reporting harassment is risky. When sexual harassment is seen as just the way things are, harassment cultures are reified. The examples also show that whisper networks are for women who need safer channels to discuss, make decisions, and collaborate when harassment is not taken seriously, or the cost of reporting is high.

4.2. Theory 2: whisper networks serve as a sensemaking mechanism when sexual harassment happens in organizations

Whisper networks serve as a sensemaking mechanism. Sensemaking is the process people go through as they try to understand their experience and make it fit into narratives they already have (see: Weick, 1995; Dougherty and Smythe, 2004). After a woman experiences sexual harassment, she may need ways to understand the reality of what happened. She might ask things like, Am I crazy? Do you think he misunderstood my intention? Did I do something wrong? If women are lucky, they find support—someone to say, you are not crazy. He should not have done that to you. As the term implies, these reality checks are done in secret. Women whisper and network to make meaning of their own experiences to keep others from the same fate. Allowing space for women to share stories, be heard, and make sense of their experiences is another purpose whisper networks serve and can be seen through seven properties of sensemaking: identity, retrospective, ongoing, enactive, based on extracted cues, social, and plausible (Weick, 1995). Several of these sensemaking properties can be seen in participants' experiences with whisper networks.

Sensemaking is a retrospective function that can help people understand harassment after it happens (Weick, 1995; Dougherty and Smythe, 2004). Gloria, who tried to report and was told it was her fault she was assaulted, talked to a friend in her whisper network to make sense of the situation, and her friend helped her realize that “It takes two to tango. But when somebody has a history, then you might want to think that maybe this is not entirely my fault, and I should not be the one that should be held responsible for this.” Other participants talked about using the whisper network to help others understand their experiences and fears. Sensemaking is also based on identity construction and is a social phenomenon (Weick, 1995; Dougherty and Smythe, 2004). When someone experiences trauma, they may have a crisis of identity and meaning (Zehr, 2001), and sensemaking can help women better understand the shame they experience from sexual harassment. Emma talked about the shame and stigma accompanying women whenever she tries to report harassment. She felt whisper networks were safer because people could share their stories or give warnings without harming themselves.

It's really important that these stories get shared as much as they can be, even when they're anonymous, even when we don't know the whole story; it helps people understand how common this is. We use whisper networks—because we don't have a better way to talk about it yet. Because there's so much shame…there's so much shame and so much stigma on people who come forward—that it's like women have found whisper networks as a way to communicate around that—to get around the shame and just say, “Okay, but just like FYI, don't talk to him.”

Emma felt like whisper networks helped her make sense of harassment because, in whisper networks, she didn't have to experience the same level of shame.

Past experiences also influence plausibility (Weick, 1995; Dougherty and Smythe, 2004). For an event to make sense, it needs to seem plausible. In other words, sensemaking can happen in whisper networks instead of formal reporting because, in whisper networks, people feel that they are more likely to be believed when they talk about sexual harassment. They are believed because the story seems plausible to others who have experienced sexual harassment. Claire explained how difficult it is to get people to believe you when you discuss sexual harassment.

I think every woman has to speak up because, apparently, it takes 30 women for every one man for it to not be he-said, she-said. And by the way, it drives me crazy because it's never he-said, she-said. It's like our ex-president has 25 examples of she-said, and when he-said, apparently America said, “Go fuck yourself.”

Claire's experiences led her to believe that women are not often believed, so she uses whisper networks regularly. Jessie wishes more women were in power because they are more likely to believe and understand.

I just wish people felt good enough to report it more. This is coming from somebody who tries to report it when it happens. I also wish more women were in power because they get it a little more. Like when I tried to report it, it wasn't taken seriously. I didn't give up—like I kept telling different managers until somebody finally believed me, but it took a long time.

Jessie feels like believing people is a large part of getting people to share their stories and explained, “I just think it is important to know that there are people like me who want to make sure that other women feel heard and are protected. We need to make it known a little more that people will believe them.”

Sensemaking works through enaction because people aren't just acting in an environment; they create the environment (Weick, 1995). Victoria said she is now an active member of whisper networks because no one had told her about a departmental harasser until after it had already happened to her. “They could have told me from the beginning that he was a problem. And you know that's why I've been vigilant as I have been. It makes me upset when people walk into situations and don't know what's happening, and nobody with knowledge helps them.” While sensemaking can help women better understand and make sense of their experiences, it does not always help women see who is and is not risky when they enter a new situation. Sexual harassers are hard to identify without the help of a whisper network. The third purpose of whisper networks is the identification of sexual harassers.

4.3. Theory 3: whisper networks serve as identification mechanisms because it is difficult to know who a harasser is before you experience their harassment

Harassers do not wear a big sign to let people know they are a risk. They look and act like everyone else. In fact, Emma commented that her harasser was “A super nice guy, as they always are.” Whisper networks are important because women cannot automatically tell if a nice guy is nice or if he is a harasser who puts on a nice guy mask. Participants repeatedly identified harassers in hindsight, but it is difficult to know who is risky. In the following section, I present participants' reported demographics of harassers, their positionality in the organization, and the types of organizations where harassers operate. I have italicized demographic or descriptive words that participants shared to highlight the impossibility of knowing who poses a threat of harassment. The words show positive and negative traits, but they are not consistent. Whisper networks function to protect women because it is nearly impossible to profile a harasser to avoid them.

Whisper networks are well-situated to preemptively communicate the risk of harassment. Even when whisper network information is an open secret, new people must be informed. Olivia talks about her first whisper network experience after college when she started working at a large law firm and how women in the whisper network warned her about some of the men at the firm.

So, you know, looking back, I would say, like, my first job outside of law school, working for a large law firm in [city]. I was told by quite a few different women just to, you know, expect to be excluded from certain client meetings or dinners, or because, you know, the men would tell, you know, sexist, inappropriate jokes, they would go to strip clubs. And, you know, women clearly weren't welcome.

Olivia needed a whisper network to help her understand ways she might face harassment, and who the harassers were. Her organization's culture was steeped in harassment because of men who told inappropriate jokes and took clients to strip clubs. Women in the firm protected each other and warned new members about the culture.

Carmen talked about the managers at the steakhouse where she worked and how at age 15, she didn't know how to deal with grown men. “All the managers, in my mind, were old, but they're probably like in their 30s. They were like they were all married or had kids, and we were high school girls. We didn't know what to do; it was just that awkward.” Claire was similarly young when she had to make decisions about dealing with a teacher who was a known harasser. She talked about when she applied to be a teacher's aide for her high school math teacher. He would add comments to his request for a teaching assistant about wanting a TA with big boobs, but no one was enforcing rules about sexual harassment in the 90s. Claire also talked about being harassed by a leader in her church. “He told me how to masturbate. I was 13 years old.” In these examples, the harasser was in a position of trust and worked with teen girls. Participants learned to identify harassers through the whisper network early because the adults, who should have been safe, were not. Profiling harassers does not seem to get easier, even with experience, because nice does not always mean safe.

Rebecca said it is important to be aware of overly friendly people, and Emma talked about a professor who presented as nice but was known for sexually harassing undergraduates.

I don't think that the students, for the most part, know that there's anything creepy or weird about him. He's very friendly. He's one of those professors who let everybody call him by his first name and is just like everybody's buddy… That's his approach to teaching that he's your pal, your smart friend.

Sometimes whisper networks are needed for identification because harassers send mixed messages. Rebecca shared the profile of the harassing supervisor she had at a law firm. She pointed out that he was intimidating and flirtatious and would “use his marriage and kids as an excuse to invite new young employees to his home.” Rebecca got caught in his flirtations because no one warned her. She used the whisper network to help other women figure out what he was like in hopes they could avoid the same problems. Sometimes the harassment is blatant, but the purpose of identification is to keep others out of dangerous situations. Victoria talked about her experience as a faculty member at two different universities, “Both of which had faculty members that were either sexual harassers or very aggressive and difficult with students. Some of these folks, who sexually harass or are aggressive, are also highly manipulative and like playing with people.” In all these situations, women would have struggled to identify a harasser until they had a bad experience or got information through the whisper network. Even when people can spotlight an identifiable characteristic of a harasser, those characteristics are not always transferable to the next experience or organization. Whisper networks exist because safety feels ambiguous when you cannot easily assess who might be dangerous.

In this section, I have identified three theories about the purposes whisper networks serve in organizations. First, whisper networks serve as protection in cultures of harassment. Cultures of harassment are formed and maintained when harassment is not taken seriously, and reporting harassment is risky. Second, whisper networks serve as a sensemaking mechanism when women share and hear stories in whisper networks. Finally, women can help identify harassers by using whisper networks.

5. Discussion

Whisper networks' first purpose in organizations is to protect women who work in organizations where a culture of harassment is prevalent. The data from this study supports earlier studies done about sexual harassment in organizations (Dougherty, 2001, 2017; Scarduzio et al., 2018), confirms reports of problematic reporting systems (Bowes-Sperry and O'Leary-Kelly, 2005; Langer and Langer, 2017; Hershcovis et al., 2021), and corroborates research about the risks women face when reporting sexual harassment (Cortina and Magley, 2003; Cortina and Berdahl, 2008; Dougherty, 2009). Whisper networks are essential communication systems that exist to keep women safe when sexual harassment is not taken seriously or when formal reporting systems are risky for the person who experiences sexual harassment. This research on whisper networks adds depth to previous research because it looks at the stories shared in backchannels instead of formal reporting structures or formal policies. For example, whisper networks form as sexual harassment is discussed behind closed doors or over a glass of wine.

Moreover, participants shared stories about working in places where harassment is the expected norm. Not only did they feel like it was the normal culture of their organization, but many reported that it was a culture they had experienced from a young age. Some harassment was accepted enough to happen openly and often. For some, sexual harassment was so common that it was an anticipated joke when middle-aged men worked with teenage girls. Cultures of harassment were exemplified by one participant who saw her professors joking about Title IX and making light of a student's desire to know who was unsafe to speak to at conferences. Participants talked about the lack of accountability for supervisors who were repeatedly reported for sexual harassment. Adding this research on whisper networks reifies how often women dealt with cultures of harassment behind the scenes and gives insights into their awareness of toxic systems even before sexual harassment occurs. These cultures of harassment are maintained by systems where sexual harassment is not taken seriously and when it is risky to report sexual harassment.

Additionally, whisper networks serve as protection when harassment is not taken seriously. Participants shared several experiences where sexual harassment was not taken seriously by their organization. I found that sexual harassment was not taken seriously in high schools, service jobs, universities, churches, and professional offices through participants' stories. Participants shared stories about when they tried to report professors who repeatedly sexually harassed students. Those reports were not taken seriously, and one participant was told to be patient because the harasser would retire soon. That professor retired but remained a guest instructor for many years after. When multiple women reported repeated sexual harassment from a colleague, they were turned away because they had no physical evidence. Sometimes this erasure is called silence, but communication in whisper networks information is not necessarily silenced or erased. Instead, the information goes underground and is shared quietly by women trying to protect other women.

When participants talked about risk or safety, they recognized that risk could take many forms, and some risks are more difficult to deal with than others. For example, participants discussed risks such as self-doubt or not knowing how the report would be received. They asked questions like; will I be believed? Will the harasser retaliate? Will I have to work with this person even though they know I reported them? These concerns might seem light on the surface, but it is a daunting proposition to face a harasser day in and day out after reporting. Women reported risking the loss of friendships and connections that had previously been important to them and the potential mental health risks. Additionally, women worried about retaliation on their reputation, humiliation, becoming the subject of office gossip, or being labeled a troublemaker or dramatic, which puts them at risk of losing their job or not getting a promotion. Each of these risks is life-altering, and some women cannot afford, financially or otherwise, to take those risks. The risks of reporting sexual harassment have been well-documented (Svoboda and Crockett, 1996; Dougherty and Smythe, 2004; O'Leary-Kelly et al., 2004). This study expands the literature by exposing how these risks are communicated between women as they share information, plan, or sympathize with one another.

The next theory that surfaced is that whisper networks allow women to make sense of their sexual harassment experiences. Sexual harassment does not necessarily make sense when it happens, and women who experience sexual harassment at work need a way to make sense of their experience and decide how they want to proceed. For some participants, whisper networks were a way to process their experiences; others made sense of their experiences as they found other women in the whisper network who had experienced sexual harassment from the same perpetrator. Whisper networks serve the purpose of helping women make sense of their experiences of harassment, but they also provide a pathway to formal reporting when women began sensemaking together. They found each other through the whisper network and then were able to make formal complaints. Some of the complaints were successful, while others showed further evidence of cultures of harassment. Participants showed how collective resistance is possible when information is shared. Sometimes whisper networks facilitate collective resistance that can lead to reporting through formal structures (Alvinius and Holmberg, 2019). Repeatedly participants shared stories about care and concern from others in their whisper network, and several stories ended in a collective response or action. The data in this study backs up what other scholars have found about the power of collective care and response instead of leaving targets to deal with or handle harassment alone (Lutgen-Sandvik, 2006; Tye-Williams and Krone, 2017; Alvinius and Holmberg, 2019). In fact, sharing stories of resistance is one way women can change the harassment narrative and say “we resisted” instead of wondering if the harassment was “bad enough to report” (Cermele, 2010). An important takeaway is that women use whisper networks to build community and courage to deal with sexual harassment in their organizations.

Finally, whisper networks help women know who has been accused of or who is a threat for sexual harassment. Participants gave me ample examples of the harassers in their organizations, but these did not come from their inherent ability to pick a harasser out of a crowd. They either learned who the harassers were through bad experiences, or someone in the whisper network gave them a heads-up. In the interviews, women shared the profiles of the people who were known harassers, and it became apparent that harassers cannot be typecast. Harassers look and sound like everyone else. They come from all income levels and educational levels. They can be outgoing, charming, sweet, and friendly. Harassers can be any age—old, young, or in-between. They hold many positions, some powerful and some less powerful. They can be religious or secular. They can be drinking or sober. It is hard to know who is risky unless you experience sexual harassment yourself or find the protection of a whisper network. Whisper networks can help women bridge the gap in protection when they enter a new organization by alerting them about known harassers.

6. Limitations

Limitations included a lack of diversity in participant demographics. The call for participants began with my personal social media accounts which may have contributed to most participants being white and highly educated. However, participants came from a wide variety of jobs, and many shared stories from both current and previous jobs. It should also be noted that participants in this study were self-selected and had the ability to identify sexual harassment in their personal experiences. Similar research should be done with a broader pool of participants to add layers of understanding based on diversity and life experience.

Research on bullying indicates that the most effective way to receive organizational intervention is when several employees come together to engage in collective resistance (Lutgen-Sandvik, 2006; Tye-Williams and Krone, 2017). Future research should examine how whisper networks might help targets organize and develop strategies for reporting mistreatment. Whisper networks could function as an important mechanism that can fuel organizational change.

7. Conclusion

This examination of the purposes whisper networks serve in organizations sheds important light on why sexual harassment has remained a prominent issue in organizations. It also points to broader organizational issues that discourage women from reporting sexual harassment and continue sharing important protective information secretly in informal networks.

Whisper networks are an overlooked and under-researched subculture of networked communication, but the interviews show that women build communities of protection, care, and understanding. It is aptly named the “whisper” network because whispers are intimate. From a young age, we learn to whisper about things that might get us in trouble, things that might bring humiliation or danger, and secrets that might hurt someone else. Whispers are also often brief, which means they can only be shared with people who are finely tuned into the meaning of what we want to share. They often indicate the lack of safety in speaking out loud, so a whisper network allows stories about sexual harassment to stay quiet but still get to those at risk. Because whisper networks are just beginning to be studied in academia, this study provides a theoretical foundation for how protective communication functions in organizations. Importantly this study is framed through the viewpoint of women who use whisper networks to protect other women.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available due to participant privacy. Requests to access the anonymized datasets should be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Institutional Review Board (IRB), Iowa State University. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Acknowledgments

I want to thank Stacy Tye-Williams for being my committee chair and the best mentor a human could ask for. Thanks to Craig Rood, Anne Kretsinger-Harries, Maggie LaWare, and Kelly Odenweller for their guidance, support, and feedback. I sincerely appreciate those willing to participate in these interviews, without whom this dissertation would not have been possible. Finally, I am overwhelmingly thankful for the support from my partner, family, friends, colleagues, and the faculty and staff at Iowa State University's department of Rhetoric and Professional Communication.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^If the information is only passed between two people that group is better labeled as a dyad.

References

Alvinius, A., and Holmberg, A. (2019). Silence-breaking butterfly effect: Resistance towards the military within #MeToo. Gender Work Organ. 26, 1255–1270. doi: 10.1111/gwao.12349

Bergman, M. E., Langhout, R. D., Palmieri, P. A., Cortina, L. M., and Fitzgerald, L. F. (2002). The (Un)reasonableness of reporting: antecedents and consequences of reporting sexual harassment. J. Appl. Psychol. 87, 230–242. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.87.2.230

Bowes-Sperry, L., and O'Leary-Kelly, A. M. (2005). To act or not to act: the dilemma faced by sexual harassment observers. Acad. Manag. Rev. 30, 288–306. doi: 10.5465/amr.2005.16387886

Breger, M. L., Holman, M. J., and Guerrero, M. D. (2019). Re-norming sport for inclusivity: how the sport community has the potential to change a toxic culture of harassment and abuse. J. Clin. Sport Psychol. 13, 274–289. doi: 10.1123/jcsp.2019-0004

Brickell, C. (2006). The sociological construction of gender and sexuality. Sociol. Rev. 54, 87–113. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-954X.2006.00603.x

Browne, K. (2005). Snowball sampling: Using social networks to research non-heterosexual women. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 8, 47–60. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000081663

Carter, R. (2021). “It's the Only Thing We Have”: Whisper Networks among Women Theater Actors (Theses and Dissertations—Communication). University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY, United States.

Cermele, J. (2010). Telling our stories: the importance of women's narratives of resistance. Viol. Against Women 16, 1162–1172. doi: 10.1177/1077801210382873

Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis. London; Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Charmaz, K., Thornburg, R., and Keane, E. (2018). “Evolving grounded theory and social justice inquiry,” in The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research, 5th Edn, eds K. D. Norman, and Y. S. Lincoln (Los Angeles, CA; London; New Delhi; Singapore; Washington, DC; Melbourne, VIC: SAGE), 411–43.

Chira, S., and Einhorn, C. (2017). How Tough Is It to Change a Culture of Harassment? Ask Women at Ford. The New York Times. Available online at: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2017/12/19/us/ford-chicago-sexual-harassment.html (accessed May 16, 2022).

Chun, T. Y., Birks, M., and Francis, K. (2019). Grounded theory research: a design framework for novice researchers. SAGE Open Med. 7, 205031211882292. doi: 10.1177/2050312118822927

Clair, R. P. (1999). standing still in an ancient field: a contemporary look at the organizational communication discipline. Manag. Comm. Q. 13, 283–293. doi: 10.1177/0893318999132005