- Department of Communication, Georgia State University, Atlanta, GA, United States

This study reconsiders the concepts of representative form and visual ideographs in the context of collectives-in-formation heavily reliant on the online environment to communicate with global audiences. Focusing on the online media products of ISIS, the study conducts a quantitative content analysis of over 9,000 images that the group distributed from 2014 to 2020, coupled with a qualitative assessment of the group's religious and institutional contexts. The findings add to current understandings of how reconstituted communities develop visual ideographs by showing how predictable constellations of iconic and non-iconic compositional elements combine to create representative forms and how non-parodied images can also function as ideographs. The study also documents that ISIS uses differential language-based targeting strategies for visual ideographs and demonstrates how institutional definitions can serve as critical intervening variables for understanding the reinforcing relationship that can exist between icons and verbal ideographs.

Introduction

In an article written more than two decades ago, Edwards and I revealed an important nexus that exists between visual images and ideology (Edwards and Winkler, 1997). Believing that conventional theories of genre, culture types, icons, and metaphors were insufficient to account for the ideological force of the parodied versions of the Iwo Jima memorial, we used Baty's (1985) notion of representative character and Burke's (1969) notion of the representative anecdote as the foundational basis for our conceptualization of representative form (for more on representative anecdotes, see Brummett, 1984). We demonstrated how representational form expands McGee's (1980) concept of the ideograph—that is, “a one-term sum of an orientation” (p. 7)—into the visual realm in limited instances. Subsequent studies have indexed and explained the functions of visual ideographs, but the vast majority have focused on media products circulating in the offline environment that reinforced and challenged various aspects of existing, internationally recognized states. The online environment, however, changes the communicative context as it capitalizes on the affordances of visual images in ways that expand opportunities for reconstituting communities across national borders. This study examines the media products of ISIS distributed from 2014 to 2020 to explore how textual and visual ideographs, icons, and intervening variables function for communities-in-formation seeking to attract and sustain online global audiences.

Contributions to existing research

Our 1996 study sparked a lively debate among communication studies scholars as to the appropriateness of expanding ideographic studies into the visual realm. Some refused to accept any departure from McGee's (1980) original definition of ideographs—that is, terms of ordinary political discourse that have flexible and adaptive meanings capable of uniting communities, that warrant the use of power in ways considered antisocial or eccentric under normal circumstances, and that embody culture-bound meanings (e.g., Hariman and Lucaites, 2003). Those advocating this more conventional approach maintained that some visual images function as icons (not ideographs) that do cultural work by “reproducing ideology, communicating social knowledge, shaping collective memory, modeling citizenship, and providing figural resources for communicative action” (Hariman and Lucaites, 2003, p. 9). Others avoided the controversy altogether by refusing to depict visual images as either ideographs or icons. Pineda and Sowards (2007), for example, maintain that certain visual images serve as negative counterpoints to the dominate culture by expressing “cultural citizenship, civic virtue, and democratic participation” (p. 167) with no mention of whether their analyzed images qualify as icons or ideographs.

Those who accepted that visual images could qualify as ideographs focused on expanding understandings of how visual ideographs operate. Recognizing that visual ideographs are often “framed and managed by discourses of the hegemonic elite” (p. 288), Cloud (2004), for example, explores how such images function to index verbal ideographs by rendering such terms less abstract for members of the collective. Cox (2016) and Long (2020) maintain that visual ideographs can redefine and reframe cultures with unintended, long-term consequences, with Cox (2016) adding that visual ideographs, in certain contexts, can work within visual narratives to accomplish their cultural purposes. Finally, Palczewski (2005b) insists that visual ideographs encompass both performative and propositional functions that make arguments visible that would otherwise remain hidden.

Certain scholars weighed in on the debate by expanding the definition of ideographs. Ewalt (2011), for example, shows how verbal ideographs, visual ideographs, and space-based experiences combine synchronically to reinforce ideological perspectives. Enck-Wanzer (2012) goes further to offer a fully revised definition of ideographs: “(a) the verbal, visual, and embodied symbolic repertoire that (b) is defined by, and in turn defines, the social imaginary, which (c) facilitates ideologically, historically, and doctrinally constrained modes of stranger relationality” (p. 50). Importantly, Enck-Wanzer's conception highlights the need for scholars to move beyond conventional ideographic assessments associated with long-standing communities (e.g., the United States) to place a stronger focus on the experiences of collectives-in-formation.

This study augments the work on visual images and ideology in three ways. First, it explores how visual ideographs operate to attract global adherents in the online environment. Previous analyses mostly focus on how ideographs and icons function in offline environmental contexts. This work explores photographs displayed in magazines (Cloud, 2004), images reproduced and circulated on postcards (Palczewski, 2005a,b), graphical illustrations displayed in comic books (Cox, 2016), images appearing on placards and billboards at rallies or parades (Hayden, 2009; Enck-Wanzer, 2012), media photographs of foreign flags flown at cultural gatherings (Pineda and Sowards, 2007), photographs drawn from traditional offline media sources (Hariman and Lucaites, 2003), and spatial experiences associated with physical places (Ewalt, 2011).

Yet, visual messaging has a distinct ability to matter in the context of the online environment. Visual images are more likely to attract viewer attention than information delivered via textual or oral modalities (Graber, 1990; Pfau et al., 2006), a factor with unique importance in the glutted online information environment. Viewers are also more likely to believe (Barry, 1997; Finnegan, 2001; Pfau et al., 2006), quickly process (Pfau et al., 2006) and recall (Newhagen and Reeves, 1992; Knobloch et al., 2003) visual images, which in tandem work to address the short dwell times of viewers who “surf the web.” The capacity of images to convey ideological propositional content (O'Loughlin, 2011; Zelizer, 2018) and heighten emotional responses (Lang et al., 1996; Cantor, 2002; Nabi, 2003; Hariman and Lucaites, 2007) may also help motivate online sympathizers to change their group affiliations. Finally, the use of visual images assists in overcoming language barriers that challenge attempts to reach and convince wide-ranging subgroups of global citizens to eschew their previous identity formulations and join new collectives.

Despite the value of visuals in the online messaging process, only a small number of ideographic studies have examined media products distributed online. Stassen and Bates (2020), for example, analyze online memes associated with <angry white male> around the confirmation hearings of Brett Kavanaugh. The authors conclude that online memes, when viewed in combination with one another, can create an ideological narrative to “represent and perpetuate factions” (p. 351). Moreover, Lokmanoglu (2021) examines online graphical illustrations of ISIS coins in the group's economic messaging to explain how imagined objects can also perform as visual ideographs in the online environment.

By examining the totality of image content in ISIS's three most prominent online publications distributed in English and Arabic over a 6-year period, this study expands upon previous understandings of how visual ideographs work for communities-in-formation seeking to recruit from globally dispersed audiences. In short, it explores how non-parodied images can function as visual ideographs to help aggregate online adherents. Further, it demonstrates how visual ideographs can help address the diverse range of situational experiences and the wide array of previous identity formations that challenge emergent groups' abilities to recruit potential members from global audiences. Finally, it shows how visual ideographs can function as key components of language-based targeting strategies for emergent groups.

A second way this study contributes to understandings of ideographs is by focusing on the process for how visual ideographs evolve in the context of online collectives-in-formation. While a substantial body of scholarship has explored how ideographic meaning shifts over time, little theoretical attention has focused on how ideographs come into being. Lucaites and Condit (1990) offer a key exception by explaining that over time, one-term sums of an orientation move from their status as labels, to key components of repeated societal narratives within a collective, to ideographs that define the boundaries of a culture. Whether their articulated evolutionary process applies either in the case of visual ideographs or in the context of stand-alone, emergent communities operating online, however, remains unexplored. Stassen and Bates (2020) offer a starting point when they argue that visual ideographs only emerge after online audiences generate a compilation of memes in response to a controversial event. This study expands on their finding by examining how a constellation of icons and compositional elements connected to the definitional characteristics of ideographs merge to form representative visual forms for global collectives in formation.

The third key insight of this analysis involves an expanded understanding of how visual icons and term-based ideographs intersect to mark a culture. Palczewski (2005a) first explores this important area of inquiry by showing how visual icons and related non-iconic images can reinforce the disciplinary norms of verbal ideographs. Hayden (2009) adds that patterned uses of visual images associated with verbal ideographs help fix the terms of the debate between conflicting ideological perspectives. Here, I emphasize the need to consider the importance of intervening variables in such processes by building on a specific portion of Enck-Wanzer (2012) revised definition of an ideograph, namely “doctrinally constrained modes of stranger relationality” (p.6).

Materials and methods

This study examines how ideographs function in relation to the visual images in the online media campaign of ISIS. In 2006, al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI) distanced itself from its parent organization (al-Qaeda) by creating and rebranding its own reconstituted collective. Over time, the group evolved under various names including the Islamic State in Iraq (ISI), the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), and the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL). Eventually, the group settled on the moniker “Islamic State” in June of 2014. The group posted more than 200 media products per month during its peak production period (Milton, 2016), a distribution level that decreased when the group lost most of its controlled territory to U.S.-led coalition forces in 2017–2018 (Milton, 2018). At the time of this writing, however, the group continues its media campaign with almost weekly installments of distributed online materials. ISIS's demonstrated ability to attract tens of thousands of recruits from more than 80 countries in support of its cause illustrates both the global reach and arguable success of its online media products (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2016).

To identify ISIS's ideographs in its online media publications, this study analyzes the text and images in each of the 15 issues of the group's English magazine Dabiq (2014–2016), the text and images in each of the 13 issues of the group's multilingual magazine Rumiyah (2016–2017), and the images in the first 143 issues of its weekly Arabic newsletter al-Naba (2015–2020). The dataset includes 4,810 images, with 1,473 images from Dabiq, 565 images from Rumiyah, and 2,772 images from al-Naba. The combined dataset includes 58 percent of its images from Arabic publications and 42 percent from English magazines.

This study draws from a long-term effort to analyze the visual imagery in the online publications of al-Qaeda and ISIS from 2009 to 2022 involving more than 30 coding categories for more than 9,000 images. It conducts a quantitative content analysis to identify the recurrent compositional elements of ISIS's visual icons and ideographs. The coding instrument previously developed for the larger project underwent multiple pilot iterations based on images extracted from one issue of Dabiq magazine until a minimum intercoder reliability score of 0.80 using Cohen's kappa existed for each coding category. After the finalization of the codebook, a corps of coders received both written and oral instructions on the details of the revised instrument. Two coders analyzed each image, with a third coder available to resolve discrepancies.

A two-step process identifies this study's appropriate categories of analysis. First, the revised codebook includes the religion category from the larger corpus due to ISIS's heavy use of religious topics in its recruitment appeals to Muslims worldwide, as well as the group's documented success in recruiting from countries with Arabic as the dominant language and Islam as the dominant faith (Dodwell et al., 2016). Additionally, this study assesses any coding category available from the larger project that relates to McGee's (1980) defining characteristics of an ideograph. For the coding categories in this analysis, as well as the intercoder reliability scores for each coding category, see Table 1.

Working from McGee's (1980) assumption that all ideographs are ordinary terms in political discourse and applying it to the visual context, this study uses the coding option with the highest frequency within the religion category—tawhid—as its starting point of comparison. Chi square analyses ascertain (1) any significant differences between images displaying the tawhid gesture and those present in the aggregated group of remaining coding options available in the religion category, and (2) whether ISIS's use of tawhid images, and the compositional components incorporated within them, vary between the group's Arabic and English publications. Sharpe (2015) approach of comparing observed vs. expected cell frequencies falling more than one standard deviation (±1.96) from the mean detects compositional elements that function as primary drivers of any significant findings. P-values at or below 0.001 level denote significant findings.

To examine the relationship between ISIS's ideographs, icons, and “doctrinal constraints on modes of social relationality” (Enck-Wanzer, 2012, p. 50), certain definitions serve as the basis of the analysis. The study utilizes McGee's (1980) defining characteristics of an ideograph expanded to encompass visual instantiations of the concept, as well as Enck-Wanzer's (2012) expansion of the concept to social imaginaries for reconstituted groups. For icons, it relies on Olson's (1987) definition: “a visual representation so as to designate a type of image that is palpable in manifest form and denotative in function” (p. 38). For the institutional definitions illustrating doctrinal constraints, it builds on Damanhoury's (2021) insight that ISIS's visual media campaign stands in opposition to the definition of a state agreed to by nations attending the 1933 Montevideo Convention on the Rights and Duties of States held by the International Conference on American States. As the Montevideo Conventions currently serve as the basis of the United Nation's international standards for state recognition, the study examines visual images that relate to the four qualifications of a state outlined in Article 1 of the Conventions: “a permanent population, a defined territory, government, and the capacity to enter into relations with other states” (Montevideo Convention, 1993).

Results

Visual ideographs

To unite the members of its reconstituted collective, ISIS borrows a foundational visual practice widely known to its online targeted, global audience. Signaling tawhid is the gesture of raising one's index finger to denote one's belief in monotheism and that the only God is Allah. It is an integral part of the lives of Muslims who, as they complete their required five daily prayers, use the gesture of monotheism at least nine times each day. The gesture occurs as Muslims repeat shahada, one of the five foundational pillars of Islam, to bear witness that there is no God worthy of worship but Allah, and that the Prophet Muhammad is his final Messenger. Participation in Muslim prayer rituals begin as early as the age of seven, with devout families enforcing the practice by the time the child turns 10 years of age. Further, those who choose to denounce other previous religious affiliations and accept Islam as their faith of choice utilize shahada as a testament of belief in tawhid in their required conversion ritual. Finally, immediately before their deaths, Muslims often receive encouragement from other members of the faith to utter shahada in hopes of easing their passage to heaven in the afterlife (Islamic-relief.org.UK, 2022). The appearance of the monotheism gesture is so commonplace in global Muslim culture that its use occurs outside of its conventional sacred contexts. For example, Dele Alli, three-time top scorer in the English Premier soccer league over the past 5 years, has repeatedly utilized the gesture to celebrate his successful goals, a move that spread across social media with viewers (mostly youth) mimicking it around the world in posts of their own (Dator, 2018).

Signaling tawhid serves as a symbol representing a core belief that unites many of the 1.8 billion global Muslims around the Islamic faith (Haq, 1983). Its meaning is flexible and adaptive, as no single interpretation of the Qur'an or the Hadiths (i.e., collected reports of the words and accounts of the daily practices of the Prophet and his companions) governs how individuals should demonstrate their allegiance to Allah (Abu-Deeb, 2000; Kahha and Erlich, 2006; Sands, 2006; Sookhdeo, 2006; Blanchard, 2007; Comerford and Britton, 2018). Accordingly, various interpretations of the core principle create an accommodating environment whereby individuals with disparate beliefs and expectations can still unite as followers of Islam.

Despite its daily recurrence and flexible meaning, tawhid fails to qualify as a visual ideograph for mainstream Muslim communities. More specifically, it is not a visual symbol that “warrants the use of power, excuses behavior and belief which might otherwise be perceived as eccentric or antisocial and guides behavior and belief into channels easily recognized by a community as acceptable and laudable” (McGee, 1980, p. 15). By far, most Muslims located around the globe are peaceful and do not conduct themselves in antisocial or eccentric ways. While some individuals mischaracterize all Muslims as being committed to violent jihad to ensure the global supremacy of the Islamic faith, the term “jihad” for most simply means “to strive” on a personal level and “as a tenet of sharia,… refers to the effort to achieve a moral aim, which could be an armed struggle against injustice, the desire to better oneself morally, or the pursuit of knowledge, for example” (Robinson, 2021, para 10).

To unite Muslims behind its cause, ISIS might well have chosen to repeatedly display one iconic image of the gesture to perform the cultural work needed for its emergent community. Yet, the group's images showing the gesture of monotheism vary widely (e.g., see Figures 1, 2). The demographics and identity of the humans serving as photo subjects change from photograph to photograph. The locational scenes, the presence or absence of vehicles, the number of humans within the frame, the positional stance of the photo subjects (e.g., sitting, standing, etc.), the choice of clothing, and the presence of facial coverings also differ in substantial ways. In short, any one single ISIS photograph displaying the gesture of monotheism embodies too many differences from other images showing the gesture to qualify as iconic.

Instead, ISIS's patterned reliance on a predictable constellation of compositional elements intersects with the definitional components of the ideograph to elevate the iconic gesture of signaling tawhid into the visual ideograph <tawhid>. The group reinforces the ordinary nature of the symbol's usage in its political discourse by including 253 images in their online publications (5.3 percent of the dataset) that display photo subjects raising their index finger. With one in every 20 ISIS photographs featuring this gesture of monotheism, the group regularly reminds its followers of its core beliefs that most devout Muslims have recognized since their childhoods. The <tawhid> images in ISIS publications also emphasize the normality of the gesture by varying the background settings of the photographs. The online publications feature photo subjects raising their index fingers as they are about to sacrifice their lives in martyrdom operations, as they are going off to battle, as they walk around ISIS's self-proclaimed caliphate, and even when, as children, they are playing in playgrounds located inside the caliphate.

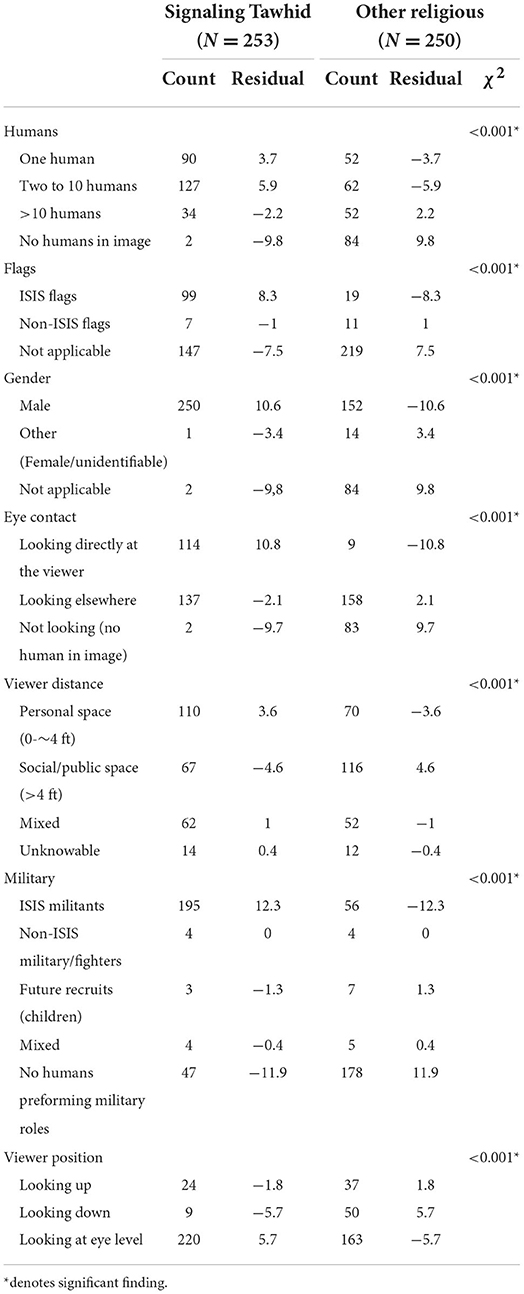

ISIS's <tawhid> images also work to unify the group's community of Muslim followers. As previously mentioned, the gesture of monotheism itself unites members of all Muslim collectives (mainstream and extreme) behind the core Islamic belief that only one God exists and that God is Allah, albeit in a flexible enough way to permit multiple interpretations by the disparate followers of Islam. Additionally, various compositional elements associated with community in ISIS's religious images vary based on whether the tawhid gesture is present (see Table 2). For example, ISIS emphasizes the communal nature of its own reconstituted collective by displaying an unexpectedly high number of <tawhid> images showing gatherings of between two to ten humans, a visual element that repeatedly emphasizes the brotherhood of group's male members. The <tawhid> images also include a much higher than expected presence of an ISIS flag, a compositional element that brands the photo subjects as members of the group. The higher-than-expected use of <tawhid> images photographed from a personal distance also contributes to the sense of community, as previous work documents how such a photographic strategy magnifies viewers' perceptions that they share a close, personal association with the photo subject(s) (Jewitt and Oyama, 2008). Finally, the higher-than-expected number of <tawhid> images shot at eye level stress the viewer's equal status with the photo subject (Mandell and Shaw, 1973; Fahmy, 2004), a factor that implies that current and future ISIS members have equivalent value for the group.

Diverging from the practices and beliefs of mainstream Muslim communities, however, ISIS adds compositional elements to <tawhid> images that warrant anti-social or eccentric behaviors in ways that vary from the group's other forms of religious imagery (see Table 2). Two compositional elements are particularly relevant in this regard. First, the <tawhid> images display much higher-than-expected presence of the group's militant fighters as they prepare for or celebrate martyrdom operations or battles against opposing state/regional forces. The second added compositional element is the higher-than-expected use of direct eye contact in ISIS's <tawhid> images, a standard visual strategy used to convey domination, power, and influence (Tang and Schmeichel, 2015). Visually incorporating both the motives and means to enact future violence, ISIS's <tawhid> images fill in the missing definitional characteristic of the ideograph in ways that divide its collective from the mainstream Muslim community.

Finally, ISIS's <tawhid> images reinforce a culture-based meaning for the group's adherents. The gesture of monotheism separates Muslims from those that believe in Gods other than Allah, those who believe in multiple Gods, or those who believe in no God at all. ISIS, however, goes further by including a gender-based compositional element that displays a much higher-than-expected use of male photo subjects (for more on ISIS's gender-based ideology and its application in practice, see Margolin and Winter, 2021). The almost exclusive reliance on males (with only one image displaying an unidentifiable gender as the exception) emphasizes the patriarchal culture of the ISIS collective.

Audience targeting and visual ideographs

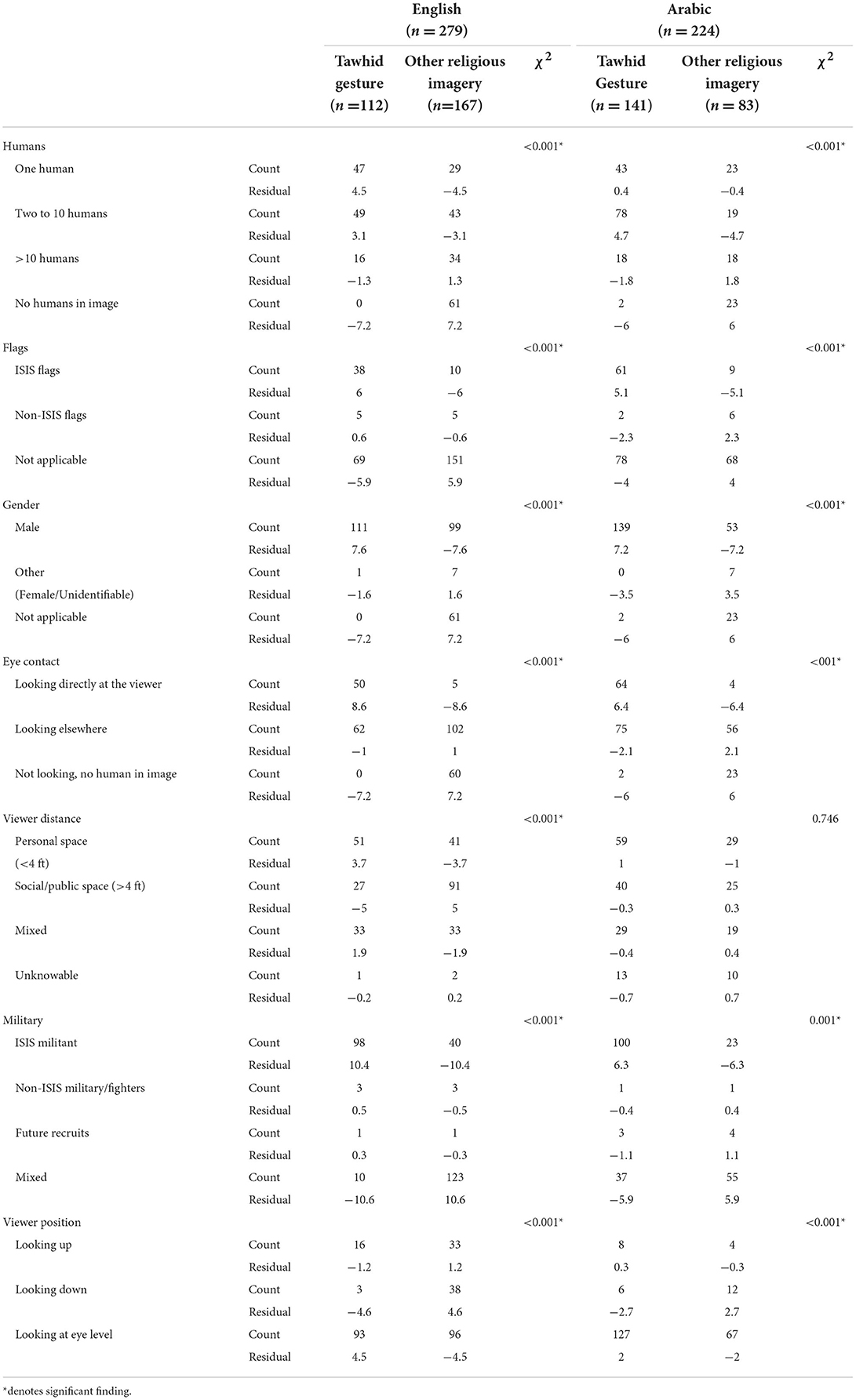

ISIS displays <tawhid> images in all its online publications, but the ideograph's frequency of use varies based on the language of the publication [χ2(5, N = 667) = 21.769, p <0.001]. <Tawhid> images appear at a much higher than expected rate in the group's Arabic newsletter and a much lower than expected rate in the English magazines. Such a distribution pattern is consistent with the fact that most Arabs, while not a monolithic entity, are Muslims (Iftikhar, 2018), a key target audience for ISIS.

However, the compositional components that extend ISIS <tawhid> images beyond the iconic gesture of monotheism remain generally consistent for the Arabic newsletter and English publications (see Table 3). For example, three of the four compositional elements reinforcing the unity of ISIS's Muslim community—the presence of 2–10 group members, the presence of ISIS flags, and the positioning of photo subjects at eye level—all exceed expected levels in the group's <tawhid> images for the publications regardless of language. The only exception is the use of personal distance, where no significant difference appears between the use of <tawhid> images in the different language publications. The compositional elements associated with antisocial behavior (e.g., dominance and power displays by militia groups), however, are also consistent between the different language publications. The presence of featured ISIS militants is far higher than expected in both the English and Arabic publications, as is the use of direct eye contact to denote dominance and power.

The intersection of icons, ideographs, and institutional definitions

ISIS utilizes a one-term sum of an orientation— <caliphate>— to both eschew the international standards of nation-state actors and encapsulate the social imaginary of Muslims governing the ummah (that is, the entire global community of Muslims). The label appears repeatedly in the text of ISIS's online publications, videos, speeches, and children's textbooks, as well as in discussions in the group's designated online chatrooms. The term unites many Muslims because of its roots in the first Caliphate led by the Prophet Muhammad. Its flexible meaning becomes apparent from the differing interpretations of prophetic rule adopted by the next four Caliphs: Abu Bakr al-Siddiq who ruled for 2 years, Umar ibn al-Khattab for 10 years, Uthman ibn Affan for 12 years, and Ali ibn Abi Talib for 6 years. ISIS publications insist that in the contemporary environment, a new <caliphate> under ISIS control will appear after the period of the forceful and harsh kingdom along the group's epochal timeline (e.g., From hijrah to khalifah, 2014). The cultural resonance and meaning of the prophecy for the group's target audience stems from its origins in the Qur'an and various hadiths (McCants, 2014). Much of ISIS's online media campaign works to fill out the specific propositional content associated with the group's <caliphate>. Besides having a specific meaning for its Muslim culture, the <caliphate> warrants the use of power by positioning ISIS in direct opposition to the territory and populations of internationally recognized states.

After ISIS announced itself as the new <caliphate>, the broader global community of Muslims—even other extremist groups— did not readily accept its self-characterization (Bunzel, 2015). While sacred texts of Islam do prophesize that another caliphate will emerge, the leader who should serve as the next caliph remains an open question. To address this challenge, ISIS uses a repeated set of icons to contest existing, recognized states and to bolster its positioning as the anticipated, socially imagined caliphate for Muslims living around the globe.

The ISIS visual icon that responds to the Montevideo Convention's requirement for states to have defined territories is the black flag. Emblazoned across the top of ISIS flag in white lettering are the words “La ‘ilaha’illa-Ilah” (There is no God but God). Below a white circle with black lettering reads “God Messenger Mohammad,” a likely reference to the Seal of Mohammed that the Prophet used to communicate his leadership of the Caliphate to other leaders in the region (Prusher, 2014). Muslims located around the globe acknowledge that the Prophet Mohammed used a black flag to distinguish his forces from those of his enemies. The Abbasid caliphate also used a black flag to serve as its official emblem beginning in 750 C.E. In the more contemporary environment, the Taliban, al-Nusra Front, the Chechen fighters and Hizb ut-Tahrir have used the icon in their militant campaigns (Bahari and Hassan, 2014). While never directly mentioned in the Qur'an, the references in the Hadith to the black flag nonetheless create an alternative social imaginary to current, institutionally sanctioned states:

The Hadith prophesise the emergence of an army from an area known as Khurasan (the region constituting Afghanistan, Central Asia, Iran and parts of Pakistan today) flying the black flag before the end of this world. From this army, the Muslim Mahdi (“Messiah”) will arise and lead it to achieve decisive victory against enemies of Islam, to finally restore the glory of Islam (Bahari and Hassan, 2014, p. 17)

In ISIS's online media products, the black flag appears 455 times, or in 9.5 percent of the images in the online publications in the study's sample (e.g., see Figure 3). ISIS uses the black flag to mark control over the lands formerly controlled by internationally recognized state actors; it also uses the emblem to mark the group's “territory,” or posts in the online environment.

ISIS employs an iconic sword in response to the Montevideo Conventions' second requirement of statehood—a permanent population. The historical roots of the sword and its use in the control of captured populations date back to the days when Muslim armies defeated the Byzantine and Persian empires (Cengiz, 2021). In this early period, the template for captives was straightforward:

As Islam spread to new territories, inhabitants were offered three choices: 1. conversion to Islam and full membership or citizenship; 2. “protection”—Jews and Christians, known as “People of the Book” (i.e., those who possessed a sacred book) in exchange for payment of a head or poll tax (jizyah) possessed a more limited form of citizenship as “protected people” (dhimmi), by which they were allowed to practice their faith and be ruled in their private lives by their own religious leaders and law; or 3. combat or the sword for those who resisted and rejected Muslim rule (Silvers et al., 2009).

For ISIS's <caliphate>, the sword regularly appears in the group's law enforcement images (n = 188, 3.9 percent), as well as in many of its advertisements and posters featured in the collective's produced videos and publications (Koch, 2018 e.g., see Figure 4). ISIS displays iconic swords to illustrate its control over populations located inside its controlled territories. As early as 2004, the group, known then as al-Qaeda in Iraq, beheaded free-lance radio tower repairman Nicholas Berg after capturing him in Iraq. The online video of Berg's decapitation went viral with more than 15 million views before its removal (Talbot, 2015). ISIS's subsequent beheadings of American journalists James Foley and Stephen Sotloff, as well as British aid workers David Haines and Allan Henning, reinforced the group's ultimate decision-making authority over individuals located inside its territories. As ISIS exercises its control over foreign citizens within its controlled lands, it demonstrates that existing internationally recognized states lack full control over their own populations. ISIS underscores the message in its videos of captured British journalist John Cantlie, who relays that the group will release captive citizens in exchange for ransom money and denounces nations who have lost their citizens due to their unwillingness to comply with ISIS's ransom demands. As the ultimate decider of life and death punishments, ISIS presents itself as the alternative entity of population control in the <caliphate>.

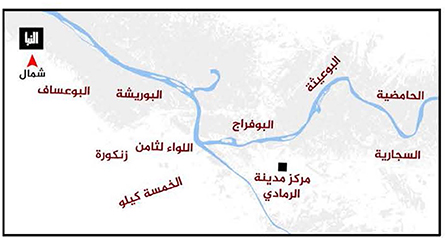

ISIS utilizes maps of its <caliphate> to address the Montevideo Convention's requirement for state governance. Evoking the memory of previous Caliphates who had increased the reach of Muslim governance in expansive ways, the maps visually document the ISIS's achievements in relation to the group's off-repeated goal to “remain and expand.” Islam's first four Caliphs expanded Muslim rule over Iraq, Syria, Egypt, and parts of Persia. The Umayyad Caliphate obtained Muslim control from lands stretching from Spain to India (Expansion of Islamic civilization, 2022). ISIS includes 73 images of maps (1.5 percent of the total dataset) in its online publications, with the vast majority of those focusing on territories that the group governs (e.g., see Figure 5). Through erasure of internationally recognized state boundaries, the maps of the <caliphate> visually reject the historically recognized boundaries that emerged after Great Britain and France divided the lands of the Ottoman empire under the 1916 Sykes-Picot agreement. ISIS's imagined alternative <caliphate> displays flexible boundaries of governmental control, as the group assumes administration responsibilities commiserate with its territorial gains and losses. In 2013, the group displays maps showing Africa, central Asia, and southern Europe as locations within its envisioned social imaginary. In 2014, the group releases a map showing it control over 16 provinces located in bulk of Iraqi and Syrian territory. By 2016, the map of the <caliphate> covers 30 provincial territories (Offenhuber, 2018). Even as the group loses governing control of its previous <caliphate> parameters, the maps still show areas like the Iraq Province, the Yemen Province and the Levant Province that continue to eschew long-established, state boundaries (Winkler and Damanhoury, 2002).

To respond to the Montevideo Convention's expectation that states have the capacity to join into alliances with other states, ISIS repeatedly displays images of bay'ah, or a life-long oath of allegiance to their group's leader. The origins of bay'ah date back to the time of the Prophet Mohammed. According to historical accounts of the bay'ah al-‘Aqabah, the Prophet introduced the people of Medina to Islam, received bay'ah from his followers, received assurances from them that they would fight to protect him and other followers of Islam, and promised the reward of heaven to those who fulfilled this covenant with God (Faruqi, 2009). Accordingly, bay'ah serves as a vital politico-legal principle which binds the ummah with the occupant of the office of the caliphate (Faruqi, 2009, p. 65). The number of bay'ah images in ISIS online publications is comparatively small in comparison to the other icons used to counter the definitional characteristics of a state (n = 60; 1.2 percent), likely because of the restricted opportunities the group had to experience and celebrate allegiance pledges. In November of 2014, the leader of ISIS received bay'ah from sympathetic, jihadist groups in Sinai, Algeria, and Libya, while in March of 2015, Boko Haram in Nigeria made the pledge (Fromson and Simon, 2015). As each group bears allegiance, ISIS repeatedly shows photographs of groups of men standing in a circle with one of their hands piled upon the others at the center of the configuration (see Figure 6). The identity of the photo subjects in these celebrations of bay'ah are often unclear, as ISIS photographed many of the participants from the back or a side view. The various settings for the pledges are also ambiguous, occurring in non-descript rooms which serve as sharp visual counterpoints to embassies—the physical manifestations of state alliances (Winkler and Damanhoury, 2002). While bay'ah does not demonstrate that groups like ISIS have the capacity to enter into alliances with other recognized states, the iconic representation of the pledge does create a social imaginary for a different world order where the <caliphate> and its allies would prevail.

Discussion

This study of ISIS's online media publications illustrates that collectives-in-formation can utilize non-parodied images as visual ideographs. For ISIS, <tawhid> is a visually patterned, aggregated configuration of iconic and non-iconic compositional elements that encompasses both the propositional content and affective dimensions of its ideology. The group's usage of the ideograph demonstrates that emergent groups can target audiences by varying the frequency of visual ideographs within multilingual online publications, while still retaining the integrity of the patterned usage of compositional elements that initially elevated the icon into the ideograph. In the process, visual ideographs help respond to the challenge of the amorphous global audience by ‘co-locating’ potentially, like-minded adherents.

The experience with <tawhid> is also revealing about the process for how images evolve into visual ideographs for reconstituted collectives. Differing from the evolutionary process that Lucaites and Condit (1990) extract from their research into verbal ideographs, ISIS begins by borrowing a foundational visual icon well known to a broader collective that the group targets as its base for recruitment. Then, the group couples the icon with a constellation of other compositional elements to reconstitute the image into a representative form that defines its own collective. This last step necessarily involves adding a patterned series of compositional elements to fill in and complete the requisite definitional characteristics of the ideograph. When repeatedly merged in patterned ways, the new formations can warrant the use of power in ways typically considered antisocial or eccentric under normal circumstances.

ISIS's demonstrated reliance on added compositional elements also helps explain why many of the early studies identifying visual ideographs have focused on parodied images. Memes, cartoons, and other parodied images routinely rely on a constellation of compositional components that have, at their foundation, a recognizable icon. The added compositional elements similarly complete the visual ideograph in ways that either reinforce or challenge existing social boundaries.

Visual icons used in the ISIS online media products provide a lens for understanding the nuanced intersections between verbal ideographs and icons, at least in the context of collectives-in-formation. Institutional definitions, initially brought into being to sustain existing power hierarchies, serve as noteworthy intervening variables for understanding the full meaning of icons that reinforce verbal ideographs. While each of ISIS's icons identified here (i.e., the black flag, the sword, the borderless map, and bay'ah celebrations) has its own discrete meaning, the full denotative function of these symbols only emerges after a full consideration of the institutional definitional context (i.e., the Montevideo Convention's requirements for statehood) and the synchronic relationship each has with the others.

This analysis also demonstrates the types of icons that have a strong capacity to reinforce verbal ideographs. Icons of particular interest are those that both challenge institutionalized definitions and connect to a well-defined, alternative social imaginary. Another discerning factor is a recognizable transhistorical subjectivity for the community targeted for reconfiguration. Supplementing Charland's (1987) poignant insight that the use of transhistorical subjectivities contribute to a timeless sense of identity for collectives-in-formation, this study reveals how ISIS uses iconic symbols from Islamic history to help entice individuals to eschew their existing identity affiliations and shift allegiances to the <caliphate>. Both the visual ideograph (i.e., <tawhid>) and the icons linked to the verbal ideograph (i.e., <caliphate>) serve as an interconnected set of reinforcements for ISIS's preferred transhistorical subjectivity by recalling past Muslim glories when the modern-day, institutional definitions of states were not in operation. By evoking a different period of power relations, the historical references recall a recognizable social imaginary known to ISIS's diverse, widely dispersed, potential set of followers.

The findings here likely have implications that extend beyond the case of ISIS. Secessionist movements, rebel groups, and other collectives that harbor less ambitious objectives share the goal of wanting to reconstitute current identity formations. In addition, such groups have ideographs and icons available to mine for the accomplishment of their objectives. Future studies should determine if emergent communities seeking to attract global members based on secular, rather than religious, ideologies use patterned forms of iconic and non-iconic compositional elements to create visual ideographs. They should also seek to identify if other types of intervening variables help illuminate how icons reinforce verbal ideographs. Finally, they should examine if non-violent emergent groups utilize the strategies identified here for how icons, ideographs, and institutional definitions intersect for building communities.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Funding

The research was supported by the Air Force Office of Scientific Research Grant No #FA9550-15-1-0373.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Author disclaimer

Any opinions, findings, or recommendations expressed are those of the author alone and do not reflect the views of the Air Force Office of Scientific Research, the Air Force, or the Department of Defense.

References

Abu-Deeb, K. (2000). Studies in the Majiiz and Metaphorical Language of the Qur'an: Abu 'Ubayda and al-Sharif al-Rac;li. London: Routledge.

Bahari, M., and Hassan, M. H. (2014). The black flag myth: an analysis from hadith studies. Counter Terrorist Trends and Analyses. 6, 15–20. Available online at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/26351277

Barry, A. (1997). Visual Intelligence: Perception, Image, and Manipulation in Visual Communication. Albany: SUNY Press.

Baty, S. P. (1985). American Monroe: The Making of a Body Politic. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Blanchard, C. M. (2007). “Islam: Sunnis and Shiites,” in: Focus on Islamic Issues, ed. C. D. Malbouisson (New York: Nova Science Publishers), 11–20.

Brummett, B. (1984). Burke's representative anecdote as a method in media criticism. Crit. Stud. Media Commun. 1, 161–176. doi: 10.1080/15295038409360027

Bunzel, C. (2015). From Paper State to Caliphate: The Ideology of the Islamic State. Available online at: https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/The-ideology-of-the-Islamic-State-1.pdf (accessed August 8, 2022).

Cantor, J. (2002). “Fright reactions to mass media,” in Responding to the Screen, eds. J. Bryant and D. Zillman (Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum), 287–306.

Cengiz, M. (2021). Beheading as a signature method of jihadist terrorism from Syria to France. Int. J. Criminol. 8, 65–80. doi: 10.18278/ijc.8.2.4

Charland, M. (1987). Constitutive rhetoric: the case of the peuple Québécois. Q. J. Speech. 73, 133–150. doi: 10.1080/00335638709383799

Cloud, D. L. (2004). To veil the threat of terror: Afghan women and the <clash of civilizations> in the imagery of the U.S. war on terrorism. Q. J. Speech. 90, 285–306. doi: 10.1080/0033563042000270726

Comerford, M., and Britton, R. (2018). Struggle over scripture: Charting the rift between Islamist extremism and mainstream Islam. Available online at: https://institute.global/sites/default/files/inline-files/TBI_Struggle-over-Scripture_0.pdf (accessed May 17, 2022).

Cox, T. L. (2016). The postwar medicalization of <family> planning: Planned parenthood's conservative comic, escape from fear. Women's Stud. Commun. 39, 268–288. doi: 10.1080/07491409.2016.1194936

Damanhoury, K. E. (2021). “The visual depiction of statehood in Daesh's Dabiq magazine and al-Naba' newsletter.” in: Networking Argument, ed. C. Winkler (New York: Routledge), 224–229. doi: 10.4324/9780429327261-33

Dator, J. (2018). Dele Alli's finger glasses goal celebration is everywhere. But can you actually do it? SB Nation. Available online at: https://www.sbnation.com/lookit/2018/8/27/17788234/dele-alli-finger-glasses-goal-celebration-can-you-do-it (accessed August 11, 2022).

Dodwell, B., Milton, D., and Rassler, D. (2016). The Caliphate's Global Workforce: An inside look at the Islamic State's Foreign Fighter Paper Trail. Combating Center of Terrorism at West Point. Available online at: https://ctc.usma.edu/app/uploads/2016/11/Caliphates-Global-Workforce1.pdf (accessed November 18, 2019).

Edwards, J. L., and Winkler, C. K. (1997). Representative form and the visual Ideograph: The Iwo Jima image in editorial cartoons. Q. J. Speech. 83, 289–310. doi: 10.1080/00335639709384187

Enck-Wanzer, D. (2012). Decolonizing imaginaries: Rethinking “the people” in the Young Lords' church offensive. Q. J. Speech. 98, 1–23. doi: 10.1080/00335630.2011.638656

Ewalt, J. (2011). A colonialist celebration of national <heritage>: verbal, visual, and landscape ideographs at Homestead National Monument of America. West. J. Commun. 75, 367–385. doi: 10.1080/10570314.2011.586970

Expansion of Islamic civilization. (2022). The Pluralism Project: Harvard University. (n.d.) Expansion of Islamic civilization. Available online at: https://hwpi.harvard.edu/files/pluralism/files/expansion_of_islamic_civilization_2.pdf (accessed May 24, 2022).

Fahmy, S. (2004). Picturing Afghan women: a content analysis of AP wire photographs during the Taliban regime and after the fall of the Taliban regime. Int. Commun. Gaz. 66, 91–112. doi: 10.1177/0016549204041472

Faruqi, M. Y. (2009). The bayah as a politico-legal principle: the prophet (SAW), the Fuqahā' and the Rāshidun Caliphs. Intellect. Discourse. 17, 65–82. Available online at: https://journals.iium.edu.my/intdiscourse/index.php/id/article/view/3

Finnegan, C. A. (2001). The naturalistic enthymeme and visual argument: Photographic representations in the “skull controversy.” Argum. Advocacy. 37, 133–149. doi: 10.1080/00028533.2001.11951665

From hijrah to khalifah. (2014). Dabiq. 1, 34–40. Available online at: https://jihadology.net/2014/07/05/al-%e1%b8%a5ayat-media-center-presents-a-new-issue-of-the-islamic-states-magazine-dabiq-1/ (accessed July 5, 2014).

Fromson, J., and Simon, S. (2015). ISIS: the dubious paradise of apocalypse now. Survival. 57, 7–56. doi: 10.1080/00396338.2015.1046222

Graber, D. A. (1990). Seeing is remembering: How visuals contribute to learning from television news. J. Commun. 40, 460–477. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.1990.tb02275.x

Hariman, R., and Lucaites, J. L. (2003). Public identity and collective memory in US iconic photography: The image of “accidental napalm.” Crit. Stud. Media Commun. 20, 35–36. doi: 10.1080/0739318032000067074

Hariman, R., and Lucaites, J. L. (2007). No Caption Needed: Photographs, Public Culture, and Liberal Democracy. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Hayden, S. (2009). Revitalizing the debate between <life> and <choice>: The 2004 March for Women's Lives. Commun. Crit./Cult. Stud. 6, 111–131. doi: 10.1080/14791420902833189

Iftikhar, A. (2018). “Shattering the Muslim monolith.” in On Islam: Muslims and the Media, eds. R. Pennington and H. E. Kahn (Indianapolis, IN: Indiana University Press), 18–26. doi: 10.2307/j.ctt2005rsc.6

Islamic-relief.org.UK (2022). Shahada [Shahadah]-A profession of faith. Available online at: https://www.islamic-relief.org.uk/islamic-resources/5-pillars-of-islam/shahada/ (accessed May 12, 2022).

Jewitt, C., and Oyama, R. (2008). “Visual meaning: a social semiotic approach.” in Handbook of Visual Analysis (7th ed., Vol. 1), eds. T. van Leeuwen and C. Jewitt (London, England: Sage), 134–156. doi: 10.4135/9780857020062.n7

Kahha, M., and Erlich, H. (2006). Al-Ahbash and Wahhabiyya: interpretations of islam. Int. J. Middle East Stud. 38, 519–538. doi: 10.1017/S0020743806412459

Knobloch, S., Hastall, M., Zillmann, D., and Callison, C. (2003). Imagery effects on the selective reading of internet newsmagazines. Commun. Res. 30, 3–29. doi: 10.1177/0093650202239023

Koch, A. (2018). Jihadi beheading videos and their non-jihadi echoes. Perspect. Terror. 12, 24–34. Available online at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26453133

Lang, A., Newhagen, J., and Reeves, B. (1996). Negative video as structure: Emotion, attention, capacity, and memory. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media. 40, 460–477. doi: 10.1080/08838159609364369

Lokmanoglu, A. (2021). Imagined Economics: An Analysis of Non-state Actor Economic Messaging [dissertation]. Georgia State University, Atlanta, Georgia.

Long, B. (2020). Ammar's banksy-style ad campaign: An analysis of verbal and visual Ideographs and synchronic dimension. Vis. Commun. Q. 27, 98–108. doi: 10.1080/15551393.2020.1732220

Lucaites, J. L., and Condit, C. E. (1990). Reconstructing <equality>: Culturetypal and counter-culture rhetorics in the martyred black vision. Commun. Monogr. 57, 5–24. doi: 10.1080/03637759009376182

Mandell, L. M., and Shaw, D. L. (1973). Judging people in the news-unconsciously: Effect of camera angle and bodily activity. J. Broadcast. 17, 353–362. doi: 10.1080/08838157309363698

Margolin, D., and Winter, C. (2021). Women in the Islamic State: Victimization, support, collaboration, and acquiescence. Available online at: https://mena-studies.org/women-in-the-islamic-state-victimization-support-collaboration-and-acquiescence/ (accessed May 2, 2002).

McCants, W. (2014). Islamic State Invokes Prophecy to Justify its Claim to Caliphate. Available online at: https://www.brookings.edu/blog/markaz/2014/11/05/islamic-state-invokes-prophecy-to-justify-its-claim-to-caliphate/ (accessed May 21, 2022).

McGee, M. C. (1980). ‘The “ideograph”: a link between rhetoric and ideology. Q. J. Speech. 66, 1–16. doi: 10.1080/00335638009383499

Milton, D. (2016). Communication breakdown: unraveling the Islamic State's media efforts. Available online at: https://ctc.usma.edu/communication-breakdown-unraveling-the-islamic-states-media-efforts/ (accessed January 17, 2017).

Milton, D. (2018). Down, but not out: An updated examination of the Islamic State's visual propaganda. Available online at: https://ctc.usma.edu/app/uploads/2018/07/Down-But-Not-Out.pdf (accessed January 29, 2019).

Montevideo Convention. (1993). Montevideo Conventions on the Rights and Duties of States: Article 1. Available online at: https://www.ilsa.org/Jessup/Jessup15/Montevideo%20Convention.pdf (accessed May 28, 2022).

Nabi, R. L. (2003). “Feeling” resistance: Exploring the role of emotionally evocative visuals in inducing inoculation. Media Psychology. 5, 199–223. doi: 10.1207/S1532785XMEP0502_4

National Bureau of Economic Research. (2016). Where are ISIS's foreign fighters coming from. The Digest. Available online at: https://www.nber.org/digest/jun16/where-are-isiss-foreign-fighters-coming (accessed May 2, 2002).

Newhagen, J., and Reeves, B. (1992). The evening's bad news: Effects of compelling negative television news images on memory. J. Commun. 42, 25–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.1992.tb00776.x

Offenhuber, D. (2018). Maps of Daesh: The cartographic warfare surrounding insurgent statehood. GeoHumanities. 4, 196–219. doi: 10.1080/2373566X.2017.1402688

O'Loughlin, B. (2011). Images as weapons of war: representation, mediation and interpretation. Rev. Int. Stud. 37, 71–91. doi: 10.1017/S0260210510000811

Olson, L. (1987). Benjamin Franklin's pictorial representations of the British colonies in America: a study in rhetorical iconology. Q. J. Speech. 73, 18–42. doi: 10.1080/00335638709383792

Palczewski, C. (2005a). The male madonna and the feminine Uncle Sam: Visual argument, icons, and ideographs in 1909 anti-woman suffrage postcards. Q. J. Speech. 91, 365–394. doi: 10.1080/00335630500488325

Palczewski, C. (2005b). “Picturing public argument against suffrage: 1909 anti-suffrage postcards,” in Critical Problems in Argumentation, ed C. A. Willard (Washington, DC: National Communication Association), 319–328.

Pfau, M., Haigh, M., Fifrick, A., Holl, D., Tedesco, A., Cope, J., et al. (2006). The effects of print news photographs on the casualties of war. J. Mass Commun. Q. 83, 150–168. doi: 10.1177/107769900608300110

Pineda, R. D., and Sowards, S. K. (2007). Flag waving as visual argument: 2006 immigration demonstrations and cultural citizenship. Argum. Advocacy. 43, 164–174. doi: 10.1080/00028533.2007.11821672

Prusher, I. (2014). What the ISIS flag says about the militant group. Available online at: https://time.com/3311665/isis-flag-iraq-syria/ (accessed May 22, 2022).

Robinson, K. (2021). Sharia: The intersection of Islam and the law. Available online at: https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/understanding-sharia-intersection-islam-and-law (accessed May 18, 2022).

Sharpe, D. (2015). Your chi-square test is statistically significant: Now what? Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 20, 2–10. doi: 10.7275/tbfa-x148

Silvers, P. V., Seesemann, R., Schoeberlein, J., Gladney, D. C., Lawrence, B. B., Bokhari, K., et al. (2009). “Islam,” in The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World, ed. J. L. Esposito. Available online at: https://global.oup.com/academic/product/the-oxford-encyclopedia-of-the-islamic-world-9780195305135?cc=us&lang=en&

Sookhdeo, P. (2006). Issues in interpretating the Koran and Hadith. Connections. 5, 57–82. doi: 10.11610/Connections.05.3.06

Stassen, H. M., and Bates, B. R. (2020). Beers, bros, and Brett: Memes and the visual ideograph of the <angry white man>. Commun. Q. 68, 331–354. doi: 10.1080/01463373.2020.1787477

Talbot, D. (2015). Fighting ISIS Online. Available online at: https://www.technologyreview.com/2015/09/30/165550/fighting-isis-online/ (accessed May 2, 2022).

Tang, D., and Schmeichel, B. (2015). Look me in the eye: Manipulated eye gaze affects dominance mindsets. J. Nonverbal Behav. 39, 181–194. doi: 10.1007/s10919-015-0206-8

Winkler, C. K., and Damanhoury, K. E. (2002). Proto-state Media Systems: The Digital Rise of Al-Qaeda and ISIS. New York: Oxford University Press.

Keywords: ideograph, images, representative form, icons, ideology, constitutive rhetoric, ISIS

Citation: Winkler CK (2022) Revisiting representative form in ISIS media: How emerging collectives reconstitute communities in the 21st century. Front. Commun. 7:968302. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2022.968302

Received: 13 June 2022; Accepted: 02 August 2022;

Published: 08 September 2022.

Edited by:

Sabine Tan, Curtin University, AustraliaReviewed by:

Molly Ellenberg, University of Maryland, College Park, United StatesRasha El-Ibiary, Future University in Egypt, Egypt

Copyright © 2022 Winkler. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Carol K. Winkler, Y3dpbmtsZXJAZ3N1LmVkdQ==

Carol K. Winkler

Carol K. Winkler