- Department of English, Indiana University of Pennsylvania, Indiana, PA, United States

Investigations of the expressive writing paradigm have shown that writing about one's experiences have positive effects on wellbeing. Understanding the writing processes facilitating self-discovery which underpin these positive outcomes is currently lacking. Prior research has suggested two writing processes that can lead to discovery: (1) Knowledge Constituting involving the fast synthesis of verbal and non-verbal memory traces into text; and (2) Knowledge Transforming involving controlled engagement with written text for revision. Here, two genres—autoethnographic poetry and freewriting–were studied as they manifest a different pattern design for Knowledge Constituting and Knowledge Transforming. One hundred and seventeen, L1 English speaking participants from 3 northwestern universities in the US completed a two-stage, genre specific writing process. Participants were randomly assigned to a writing condition. Poetry writers first did a Knowledge Constituting writing task followed by a Knowledge Transforming task. Freewriters repeated a Knowledge Constituting task. Participants completed insight and emotional clarity scales after stage one and stage two. Data was analyzed using a two-way repeated measures ANOVA with one between (writing condition) and one within subject (time of prompt) variables. Descriptive results show that it is the Knowledge Constituting process which elicits high levels of insight and emotional clarity for both genres at the first time point. Knowledge Transforming at time-point 2 significantly reduced insight. While Knowledge Constituting at time-point 2 significantly increased emotional clarity. The results provide initial support for the position that it is the Knowledge Constituting writing process which facilitates self-discovery and underpins writing-for-wellbeing outcomes.

Introduction

Writing about one's experiences has been shown to have positive effects on one's psychological wellbeing (Lepore et al., 2002; Frattaroli, 2006; Pennebaker and Chung, 2007; Lepore and Kliewer, 2013; Kállay, 2015). The majority of this research has been conducted in relation to the expressive writing paradigm developed by Pennebaker (Pennebaker and Beall, 1986). Research into this writing genre has been useful in helping to elucidate the role self-writing might play in alleviating a range of psychological and physiological situations. However, while the therapeutic intervention is writing, the actual processes of this writing which lead to these positive outcomes have not been investigated. Moreover, it has been pointed out that expressive writing might not be the only writing intervention that facilitates wellbeing and that additional genres of writing should be considered for this function (Deveney and Lawson, 2021). The current paper has two central aims in relation to the scholarship on writing for wellbeing. First, the current study provides initial information on the writing processes underpinning writing-for-wellbeing by addressing the timed development of insight and emotional clarity in two authentic genres. Second, the current study widens the types of genres to be considered in relation to writing-for-wellbeing research by investigating autoethnographic poetry writing and freewriting.

Expressive writing and its explanations

Expressive writing as an approach for addressing traumatic and upsetting experiences was developed by Pennebaker and Beall (1986). In their initial study, college students were asked to write about difficult experiences they have had for 15 min a day for four consecutive days. The writing itself was characterized by the request that the participants write about their “deepest thoughts and feelings” without paying too much attention to issues of form and grammar. Interestingly, data that was collected 4-months after this four-day writing experience showed that participants had a significantly decreased number of health center visits and self-reported health problems when compared to a control group (Pennebaker and Beall, 1986). This intriguing outcome in terms of physical wellbeing facilitated by a simple writing intervention led to a large number of studies using a similar paradigm with a range of populations. The results of these studies support positive health and psychological outcomes. For example, in relation to physical outcomes, expressive writing studies have shown decreased hospitalization, physical complaints, respiratory difficulties, cardiovascular issues, fatigue, and chronic pain (Hockemeyer and Smyth, 2002; Rosenberg et al., 2002; Norman et al., 2004; McGuire et al., 2005; Danoff-Burg et al., 2006). On the psychological side, expressive writing studies have shown decreased levels of distress, anxiety, depression, suicidal ideation, and grief (Nishith et al., 2002; Antal and Range, 2005; Graf et al., 2008; Range and Jenkins, 2010). While not all applications of the expressive writing paradigm have produced such impressive results, overall, there is a body of data from large scale meta-analyses that this writing practice does have positive physiological and psychological effects (Frattaroli, 2006; Kállay, 2015).

In light of these outcomes, it is worth considering what the explanations of these effects are. How does expressive writing interact with an individual's health and psychological state? Frattaroli (2006) in a meta-analysis of expressive writing outcomes proposes three theoretical explanations of how this type of writing functions:

a) Inhibition Theory: Based on the Freudian concept of catharsis, the core explanatory aspect of this theory is that expressive writing has positive effects on wellbeing because the writer can disclose thoughts and feelings about the experience that they have internally inhibited. This self-imposed constraint on expression causes feelings of stress and anxiety which in turn negatively impact health and psychological wellbeing. Once, these thoughts and feelings are disclosed, there is a reduction in the levels of anxiety and an associated increase in a sense of wellbeing (Lepore and Smyth, 2002).

b) Cognitive-Processing Theory: The core explanatory aspect of this theory is that through expressive writing participants gain insight into their experiences. Pennebaker (1993) found that expressive writers who had increased wellbeing also tended to use more insight and causation words in their writing. These same participants explained that the value of expressive writing was in its ability to help them explain to themselves what had happened.

c) Self-Regulation Theory: The core aspect of this theory is that through expressive writing which channels both emotions and thoughts concerning one's own experience, the writer develops a sense of control over those emotions and thoughts. Basically, writing about an experience allows participants to observe, understand and regulate their thoughts and emotions (Lepore et al., 2002). Once writers know and understand their experiences and emotions, they can develop a sense of mastery over their experiences which reduces anxiety and stress and enhances a sense of wellbeing (Lepore et al., 2002).

These explanations of the wellbeing effect of expressive writing start at the point that some level of new insight or emotional understanding has already emerged. But it should be remembered that actual intervention is writing and as such we can assume that there is some aspect in the writing process itself that facilitates and underpins the emergence of insight and emotional clarity. As such the question is what are these writing processes and how are they manifest? In the next section, scholarship on the way writing facilitates processes of self-discovery will be presented.

Writing processes of discovery

Within the cognitive scholarship on writing, there is agreement that writing not only involves communicating ideas but also a process of self-discovery (Flower and Hayes, 1980; Bereiter and Scardamalia, 1987; Galbraith, 2009). While there is agreement that discovery is part of the process of writing, there is disagreement over how this is achieved. Early approaches to this question situated discovery as an aspect of more expert writing related to active problem solving (Flower and Hayes, 1980; Bereiter and Scardamalia, 1987). The basic idea of this approach is that when expert writers are required to solve a rhetorical problem in their writing this leads to insight. As writers try to make the text match the rhetorical aspects of an assigned writing task, they need to reformulate and revise their ideas as well as their written text which leads to the development and emergence of alternative set of ideas, a greater sense of clarity concerning the content of the writing, new thoughts and feelings (Flower and Hayes, 1980; Bereiter and Scardamalia, 1987).

In the Flower and Hayes (1980) cognitive model of writing, there are three basic writing processes: (1) Planning—including content generation, organization and goal-setting; (2) Translating—the technical movement of ideas and memories into text; and (3) Revising—the editing of written text that has already been produced. For Flower and Hayes (1980) the process of discovery is situated within the Planning and Revising processes and as a result of the task requirements of a rhetorical situation. Bereiter and Scardamalia (1987) are more specific in where they situated the problem solving, discovery process. They propose that there are two different models of writing: Knowledge-Telling and Knowledge-Transforming. In this formulation, Knowledge-Telling (like the Translation process in Flower and Hayes, 1980) does not involve a process of discovery. Knowledge-Telling is a set of processes by which knowledge is retrieved from long-term memory and transferred into written text. Discovery is solely situated in the Knowledge-Transforming model. In the Knowledge-Transforming model expert writers try a range of different solutions the rhetorical writing problem they are facing. This finding of different options involves the reformation of ideas, evaluation of content and revision of the text (Bereiter and Scardamalia, 1987).

A later model which directly addresses discovery in writing proposes an additional process by which discovery emerges. The dual-process model of discovery (Galbraith, 1999, 2009; Galbraith and Baaijen, 2015) proposes that in addition to the process of discovery found in problem-solving, revision processes, that the text generation process also involves self-discovery. Thus, there are two modes or mechanisms by which discovery emerges during writing—text production from episodic and autobiographic memory (termed the Knowledge Constituting discovery process) and revision of produced text in relation to specified rhetorical goals (termed the Knowledge Transforming discovery process).

As elaborated by Galbraith (1999, 2009), text production involves discovery because the original memories that are stored in episodic and autobiographical memory are not necessarily coherent or organized. They can be sensory and non-verbal (Galbraith, 1999, 2009; Galbraith and Baaijen, 2015). According, text production is not a simple and direct process but rather involves the dynamic reconstitution in words or sensory information in episodic memory. This verbal reconstruction in short bursts of language and writing creates the event or memory anew (Galbraith, 1999, 2009; Galbraith and Baaijen, 2015). The key aspect in this process is that the production of writing forces the explication in words of an experience that was not fully verbal before and self-discovery emerges as a result of this process of writing.

The second process for discovery in writing is similar to those already proposed by Flower and Hayes (1980) and Bereiter and Scardamalia (1987). The core assumption is that rhetorical problem-solving involving evaluation, revision, and rewriting reformulates the text that emerged through the text production stage. Baaijen and Galbraith (2018) specify that during this stage it is not so much that new ideas are generated but rather that the existing text is reorganized and more coherently presented. This reorganization and evaluation lead to increased understanding of what has been said and what the experience being described means. For the dual-process model, this revision process is aligned with semantic memory in which there is far greater coherence in relation to what one knows and can state in language explicitly (Baaijen and Galbraith, 2018).

This discussion involves different initial positions over the timing and ways in which discovery emerges in writing. If Flower and Hayes (1980) and Bereiter and Scardamalia (1987) are correct, discovery only emerges from the revision (Knowledge Transforming) processes directed at the solution of a rhetorical problem. Text production (Translation and Knowledge Constituting) would not involve any increase in discovery. If the dual-process model (Galbraith, 1999, 2009; Galbraith and Baaijen, 2015) is correct, discovery would emerge in both the text-production and text-revision processes of writing. Furthermore, as Baaijen and Galbraith (2018) specify that if both Knowledge Constituting and Knowledge Transforming were present it should elicit the highest levels of discovery possible. Thus, we have a set of hypotheses concerning the type of writing process which might elicit insight and emotional clarity (Knowledge Constituting and Knowledge Transforming) and the degree and timing at which this would occur. Succinctly stated, we can hypothesize that:

1) Both the Knowledge Constituting and Knowledge Transforming writing processes have the potential to elicit high levels of insight and emotional clarity;

2) That repeating the Knowledge Constituting writing process will further heighten levels of insight and emotional clarity;

3) And that a Knowledge Transforming writing process following a Knowledge Constituting process will further heighten levels of insight and emotional clarity.

In addition to this set of hypotheses concerning the relationship of the two writing processes, we can further hypothesize about the relationship of these underpinning writing processes and the theoretical explanations of how expressive writing facilitates wellbeing. Central to the inhibition explanation of expressive writing is the idea of overcoming the self-imposed constraints on the expression of traumatic experiences (Lepore and Smyth, 2002). The Knowledge Constituting writing process involves the fast transition of sensory and non-verbal information into text (Galbraith, 1999, 2009; Galbraith and Baaijen, 2015). This writing process includes both a technical writing method and psychological process for overcoming the self-imposed constraint on knowing more fully the content of an autobiographical traumatic experience. The Knowledge Constitution process generates text that is not particularly controlled at the point of its initial constitution (Galbraith and Baaijen, 2015). The focus of attention is on verbalizing what has been remembered in sensory and non-verbal ways and not on the monitoring of this information. Once it is written, it is in the purview of the writer and has by definition been discovered or disclosed to that writer. As such there would seem to be an explanatory overlap between the Knowledge Constituting writing process and Inhibition Theory in that a surprising disclosure takes place that has therapeutic value.

The Knowledge Constituting writing can also be seen to be related to the Cognitive Processing explanation of expressive writing. Key to this explanatory theory of expressive writing is the idea that the writer develops an increased cognitive ability to explain to themselves the events that they experienced (Pennebaker, 1993). The Knowledge Constituting process provides increased verbalized information about the writer's undisclosed, non-verbal memories of the expressed experience. This increased degree of verbalized description could facilitate more insight into one's own experience as the writer has more information to work with.

Knowledge Transforming writing process could also have a role in relation to Cognitive Processing explanation of expressive writing. Knowledge Transforming is a writing process which evaluates and reorganize generated text (Flower and Hayes, 1980; Bereiter and Scardamalia, 1987; Galbraith, 1999, 2009; Galbraith and Baaijen, 2015). These processes of evaluation and reorganization may allow new ways of conceptualizing one's own experience to emerge. Taken together, the processes Knowledge Constituting and Knowledge Transforming would seem aligned with a Cognitive Processing explanation of expressive writing with the former process providing additional information to work with and the later process involving evaluating and reconceptualizing one's experience leading to enhanced insight and understanding.

The Self-Regulation explanation of expressive writing is primarily aligned with the Knowledge Transforming writing process. Self-Regulation involves an increased sense of control and mastery over an experience (Lepore et al., 2002). A sense of mastery over the experience should psychologically reduce anxiety, stress and depression associated with prior traumatic experiences (Lepore et al., 2002). Knowledge Transforming is a writing process designed to construct coherence in writing through monitoring, editing and restructuring generated text (Flower and Hayes, 1980; Bereiter and Scardamalia, 1987; Galbraith, 1999, 2009; Galbraith and Baaijen, 2015). In this writing process the writer is actively engaged in modifying and reorganizing the text that has been generated by a prior stage of writing. A sense of control over the experience itself could emerge as the writer is actively engaged in evaluating and presenting in a coherent way their description of the experience. The overlap between the Self-Regulation explanation of the wellbeing effects of expressive writing and the Knowledge Transforming process resides in the rewriting/reorganization of the experience itself. The writer is actively changing, deleting and moving text around so as to create a description that the writer feels is more coherent. Theoretically this writing process could lead to the feeling of having mastered and understood the experience being described thus facilitating the type of outcomes described in relation to expressive writing.

Freewriting and autoethnographic poetry writing

In order to explore the hypotheses concerning the writing processes of discovery, two specific genres of writing were chosen for investigation—freewriting and autoethnographic poetry writing. These genres were chosen because of the way they interact with processes of discovery. Freewriting, initially developed by Elbow (1973) within the context of the freshman Composition classroom, is defined as a timed, quick writing exercise focused on the spontaneous production of language without the inhibiting processes of correct grammar, word choice, and text organization (Elbow and Belanoff, 2000). It is a prevalent pedagogical writing practice within Composition classrooms utilized for initial text production.

The pedagogy of freewriting involves instructing students to keep writing for 15 min any ideas or thoughts that come into their mind at that moment time and most importantly to just keep writing without bothering about concerns with accuracy or linguistic correctness (Elbow, 2000; Elbow and Belanoff, 2000). It is a form of written stream of consciousness without editing. Focused or directed freewriting, a later version of this pedagogy, involves the specification of a topic, question or experience for freewriting (Fishman, 1997; Somerville and Crème, 2005). The focused freewrite is designed to provide a free-flowing set of thoughts on a specific topic and thus generate insight into that topic (Li, 2007).

The genre of autoethnographic poetry writing as implemented within the Composition classroom setting was developed by Hanauer (2010, 2021). Building upon prior work into the uses of poetic form for research purposes (Richardson, 1990, 1997, 2003; Furman, 2004, 2006; Langer and Furman, 2004; Prendergast, 2009; Hanauer, 2020). Hanauer (2010) proposed and then studied a systematic protocol for the writing of autoethnographic poetry for people who have not necessarily been exposed to poetry writing previously and are not training to be poets. This process of writing a poetic autoethnography (Hanauer, 2010, 2021) involves two basic stages:

a) Significant Memory Elicitation: In the initial stage the writer is asked to relive a significant memory from their life in a sensory-rich, detailed manner. The prompt requests sensory information concerning the experience and the writer is asked to write as many notes as they can on the memories they have. The writer is told that these notes do not need to be coherent.

b) Imagistic Poetry Writing and Revision: In the second stage, the writer chooses a specific image from the notes they have written which captures, in their mind, the central meaning and feeling present within their experience. They are then asked to carefully describe that sensory image and to revise it until it matches as closely as possible their relived memory of the experience.

As seen in Hanauer's (2010) monograph, this protocol was used with over 100 students over 6 years and produced more than 1,000 poems dealing with meaningful personal experiences.

The aim of poetic autoethnography is similar to that of phenomenology (Hanauer, 2021) in that the writer (or thinker) is directed through a process which explicates an individual's consciousness of their own experience (Giorgi et al., 2017). According to Hanauer (2010) this poetry writing process produces an “individual, subjective, emotional, linguistically-negotiated understanding of personal experience” involving “multisensory, emotional information that reconstructs for the reader the experience of the writer” (p. 137). Discovery emerges through this process as a result of the surprise that the writer has in reliving and then reflecting (and selecting) on their own experience. This genre is based on the empirical models of poetry which specify that poetry writing involves two basic sets of processes: a creative-associative stage of poetry writing and a stage of controlled revision (Schwartz, 1983; Armstrong, 1984, 1985, 1986; Gerrish, 2004; Hanauer, 2010; Liu et al., 2015; Peskin and Ellenbogen, 2019).

Empirical design, hypotheses, and research questions

The current study investigates the writing processes which underpin wellbeing outcomes by considering discovery outcomes in the two genres of freewriting and autoethnographic poetry writing. While not presenting a full empirical design, the two genres investigated here offer two different manifestations of self-discovery through writing processes. Freewriting, similar to expressive writing, consists of a repeated Knowledge Constituting (free text generation) writing process; while autoethnographic poetry writing involves a Knowledge Constituting process followed by a Knowledge Transforming (text evaluation and revision) process. As such, these genres map neatly with the hypotheses which emerged in the discussion of the current state of understanding of writing processes and discovery. Firstly, we can investigate whether these writing processes elicit high levels of discovery (defined here as insight and emotional clarity). The following research questions specify this aspect of the study:

1. To what extent does the Knowledge Constituting writing process elicit high levels insight and emotional clarity?

2. To what extent does the Knowledge Transforming writing process elicit high levels of insight and emotional clarity?

Secondly, as a result of the nature of the way the specific genres of freewriting and autoethnographic poetry are implemented as writing practices we can also address the issue of timing and writing process. Accordingly, we can also ask the following questions:

3. Do insight and emotional clarity increase at the Knowledge Transformating stage following Knowledge Constituting (as manifest in poetic autoethnographic writing)?

4. Do insight and emotional clarity increase with the repetition of two stages of Knowledge Constituting (as manifest in freewriting)?

These four questions which emerge from the connections between current scholarship on discovery in writing and the specific genres of freewriting and autoethnographic poetry will direct the current study.

Methods

Participants

One hundred and seventeen first-language English speaking students were participants in this study. The students were drawn from freshman Composition classes from three different Northwestern universities in the US. The students were randomly assigned to either the poetry writing (n = 60) or the freewriting (n = 57) conditions. There were 49 women, 65 men and 3 who gender identified as Other. The age range was from 18 to 25. Randomization was evaluated and the proportion of participants by age and gender was found to be non-significant for the randomly selected groups [Gender X2 (2, n = 117) = 0.42, p = 0.81; Age X2 (5, n = 117) = 2.82, p = 0.73]. All data was collected in accordance with the ethical requirements of the Indiana University of Pennsylvania IRB (#19-194).

Measurement instruments

The current study collected data by modifying two existing rating scales: insight and emotional clarity scales. In this study, the process of self-discovery was conceptualized as involving an understanding or insight about prior experience and as having enhanced emotional clarity in relation to one's own experience. The insight scales were adapted from Grant et al. (2002) and consisted of the following items:

1. I have a clear idea about why I behaved the way I did in this experience

2. I understand this experience

3. I can make sense of this experience

The emotional clarity scales were adapted from Gratz and Roemer (2004) and consisted of the following items:

1. I know exactly how I am feeling about this event

2. I am clear about my feelings about this event

3. I have difficulty making sense out of my feelings about this event

4. I have no idea how I am feeling about this event

5. I am confused about how I feel about this event

Both sets of scales were implemented with a 7-point (1 = Strongly Disagree−7 = Strongly Agree) matrix style question using the Qualtrics web-based survey tool.

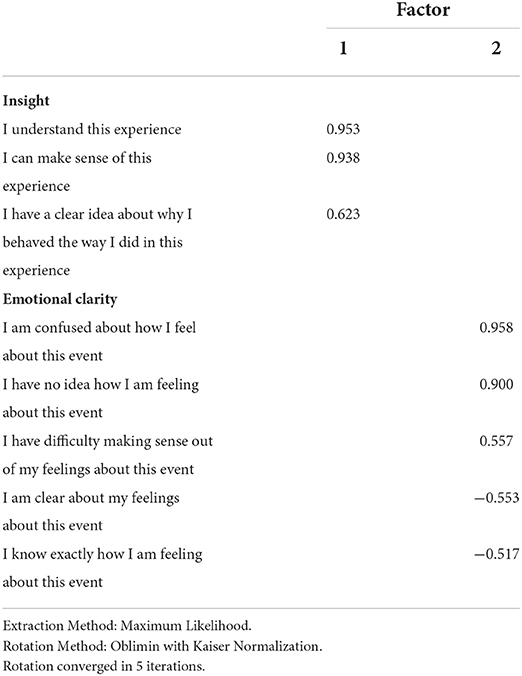

Prior to usage of these scales in the research setting, the underpinning dimensionality and reliability of the scales was psychometrically evaluated. Since these items were adapted from existing and psychometrically validated scales, a factor analysis rather than a principal component approach was utilized. One hundred and sixty-eight first language composition students, drawn from a similar sample as the core study, completed the insight and emotional clarity scales following a short memory elicitation writing task. A maximum likelihood factor analysis with direct Oblimin rotation with an unspecified factor solution was conducted. Participant to variable ratio was 24:1 and sampling adequacy was evaluated using a Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) analysis; the KMO value of 0.75 supports a suitable sample size for factor analysis. Descriptive statistics for each of the rating items used in the factor analysis were calculated to make sure that the assumption of normality was not violated. Bartlett's test indicated that the data was suitable for a factor analysis (x2 [28] = 606.7, p < 0.001). Observation of the scree plot and usage of the Kaiser criterion suggested a two-factor solution with items aligned with the original structure of the scales for insight and emotional clarity. The first factor accounted for 52.5% of the variance and the second factor accounted for 16.7% of the variance. Table 1 presents the obtained pattern matrix for the set of items and each of the factor loadings. As can be seen in Table 1, the emergent factors and their associated items correspond to the original insight and emotional clarity scales. The internal consistency of the two scales was evaluated using Cronbach's alpha. Each of the scales had an acceptable level of consistency (Insight Cronbach's Alpha = 0.88; Emotional clarity Cronbach's Alpha = 0.83). Based on this data the insight and emotional clarity scales were considered psychometrically valid for the current study.

Writing process materials

This study utilized two different writing processes—autoethnographic poetry writing and freewriting—each of which was directed by two writing prompts. The autoethnographic poetry writing process was conducted in two stages and followed the prompts from Hanauer (2010). The initial stage consisted of a text-production prompt concerning a significant moment of life and the second stage of imagistic poetry writing and text-revision. The specific prompts were as follows:

• Autoethnographic Poetry Text-Production Prompt

“Please think of a significant moment from your life. Choose a moment that you still remember vividly and a moment that in some way changed your life. Close your eyes and relive that moment. Make sure you feel it, see it, smell it, hear, it and taste it. Slowly relive in your mind the whole of the experience. In the space below, write out as many notes as you can about this life changing memory. If necessary close your eyes again and write out more notes. Your notes do not have to be coherent”

• Poetry Writing and Text-Revision Prompt

“Think very carefully about the significant experience you have just chosen. What do you think is the central moment of this experience? Try to pinpoint the central feeling that accompanies this significant moment. Try to find a scene, object or action that summarizes the meaning of this event for you. In the space below, write a succinct, focused, sensory poetic description. Describe just one thing—the most important image of that whole experience. Look at the image you wrote. Think carefully about the words you chose for this description. Ask yourself about the associations of each word and the meanings that it creates. Revise your poem and write it again as a poem.”

The second writing process consisted of freewriting and was based on Elbow's (1973) development of this writing approach. This process was conducted in two stages with an initial freewriting text production prompt relating to an everyday experience followed by a second freewriting text-production prompt relating the same experience. The specific prompts were as follows.

• Initial Freewriting Text-Production Prompt

“In the space below, I would like you to write about the event that happened to you today. Write whatever you think about this event. Don't worry about spelling, sentence structure, or grammar. The only rule is that once you begin writing, continue to do so until your time is up. You will be writing for 3 min.”

• Second Freewriting Text-Production Prompt

“In the space below, I would like you to write some more about the event that happened to you today. Write whatever you think about this event. Don't worry about spelling, sentence structure, or grammar. The only rule is that once you begin writing, continue to do so until your time is up. You will be writing for another 3 min.”

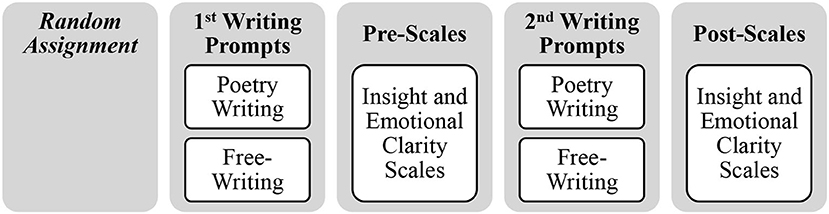

Procedure

The data for this study was collected using the online survey tool Qualtrics. The survey was designed to both collect quantitative responses as well as model the two different writing processes: autoethnographic poetry writing and freewriting. On signing into the survey, participants were randomly assigned to one or the other of the writing processes. The survey directed each participant through either an autoethnographic poetry or freewriting process. Following the informed consent process, each participant was given the first writing prompt (either for freewriting or poetry writing—see Section Writing process materials above) and 3 min to complete the task. Immediately following the first prompt each participant completed the first set of insight and emotional clarity scales. On completion of these ratings, each participant was given the second writing prompt according to their assigned writing process. The second writing process was also allotted 3 min for completion. At the end of the second writing period, each participant immediately completed the second set of ratings for both insight and emotional clarity. The final sections of the survey collected relevant demographic information. Figure 1 offers a schematic representation of the overall data collection design.

Analytical approach

The design of the current study involves the comparison of two different writing processes and the development of insight and emotional clarity over two data collection points. As such the design involves one within-subjects (2 data collection time points) and one between-subjects (2 writing processes) variable. The appropriate analysis for this type of design is a two-way repeated measures ANOVA with one-between and one-within subjects factor. This analysis was conducted independently for each of the measurement variables: insight and emotional clarity. To simplify the interpretation of the descriptive data, the three negatively worded emotional clarity scales were reversed coded so that higher levels of this scale translated into higher levels of emotional clarity. All analyses were conducted using SPSS V.28.

Results

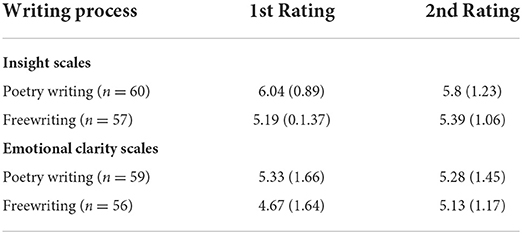

Table 2 summarizes the descriptive statistics for poetry and freewriting on the insight and emotional clarity scales at two time points. For both the insight and emotional clarity scales the mid-point of 4 represents a neutral position (Neither agree nor disagree) concerning the participants self-evaluation of the emergence of self-discovery. As can be seen in Table 2, for the insight scales, at the 1st prompt (Knowledge Constituting) the average response is in positive territory for both poetry writing and the freewriting. The average response for poetry writing is 2.04 points (29.1%) above the central point of the scale and for freewriting it is 1.19 points (17%) above. For the emotional clarity scales at the 1st prompt Knowledge Constituting stage, the poetry writing process is 1.33 points (19%) and the freewriting process 0.67 points (9.6%) above the central point of the scale. At the 1st prompt Knowledge Constituting stage, the poetry writing prompt elicits higher ratings than the freewriting with an average 0.85 points (12.1%) higher ratings on the insight scale and 0.66 points (9.4%) on the emotional clarity scales.

Table 2. Mean and standard deviation for insight and emotional clarity scales for poetic and freewiting processes at two points.

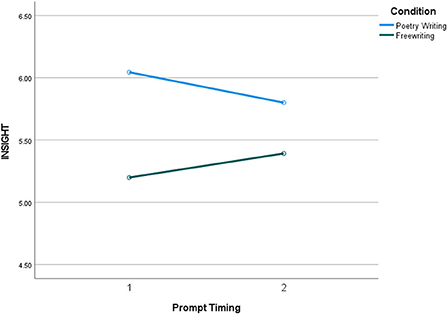

For the 2nd prompt, the question of interest is the relationship to the ratings after the first prompt. The poetry writing process involved a move from a Knowledge Constituting to a Knowledge Transforming writing process. As can be seen in Table 2, at the 2nd prompt for the insight scales we find an average 0.24 points (3.4%) decrease in average ratings when compared to the 1st prompt outcomes. This rating is still above the central point of the scale by 1.8 points (25.7%). For the emotional clarity scales the transition to the 2nd prompt Knowledge Transforming poetry writing/revision process, there is a slight decrease of 0.05 points (0.7%) at the second stage. This average rating is 1.28 points (18.3%) above the central point of the scale. As can be seen in Table 2 and Figures 2, 3, for the poetry writing process the transition from Knowledge Constituting to Knowledge Transforming involved a decrease in the overall average rating for both the insight and the emotional clarity scales.

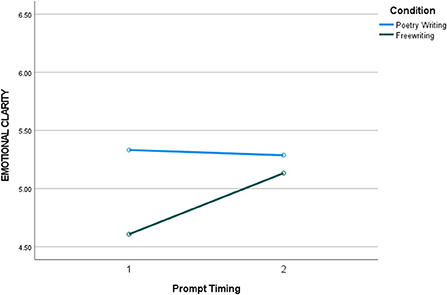

Figure 3. Line chart comparing 2 writing conditions for levels of emotional clarity at two time points.

The freewriting process involved a repetition of the Knowledge Constituting process. As can be seen in Table 2, for the insight scales the second prompt elicited a 0.2 point (2.8%) increase in average rating over the 1st prompt ratings. This average rating is 1.28 points (18.3%) above the central point of the scale. For the emotional clarity scales the second prompt elicited a 0.46 point (6.6%) increase over the first prompt. This average rating is 1.13 points (16.1%) above the central point of the scale. As can be seen in Table 2 and Figures 2, 3, for the freewriting process the repetition of the Knowledge Constituting process involved an increase in the overall average rating for both the insight and emotional clarity scales.

In order to evaluate the trends seen in the descriptive data, a two-way repeated measures ANOVA with one-between and one-within subjects factor was calculated for each of the outcome measures of insight and emotional clarity. The between-subjects categorical variable consisted of two levels of writing process (poetry or freewriting) and the within-subjects variable consisted of the two timings (1st and 2nd prompts). For the insight data, as an initial stage of the analysis, the analysis of the equality variance-covariance matrices of difference scores between groups (Weinfurt, 2000) was evaluated. Box's M-value was 24.55 with a significance level of 0.001. This test result suggests evidence of a violation of homogeneity of covariance matrices. However, multivariate tests are relatively robust with groups sizes that do not diverge from a 1.5 ratio of largest n divided by smallest n (Pituch and Stevens, 2016). For this study, the ratio of largest n to smallest n was 60/57 = 1.05 suggesting the analysis can be reported.

For the multivariate tests, there is a significant insight-prompt time x writing condition interaction, Wilk's lambda = 0.94, F(1, 115) = 7.28, p = 0.008. This significant interaction for the insight measure suggests that the two writing processes elicited different patterns of insight elicitation. There was no main effect for the timing of the prompts, Wilk's lambda = 0.99, F(1, 115) = 0.1, p = 0.75. Tests of within-subjects effects have the same results with a significant interaction (with a small effect size of η2 = 0.06) and a non-significant main effect for the timing of the writing prompt.

Levene's test of equality of error variances was calculated as part of the assumptions for the Test of Between-Subjects Effects. Levene's test was significant for the initial writing prompt (F = 6.81, p = 0.01) but not for the second writing prompt (F = 1.18, p = 0.28). This suggests a violation of this assumption at the first time point. However, when groups are of an equivalent group size this violation is less of inhibiting issue and as such the analysis was continued. Tests of Between-Subjects Effects found a significant main effect for the writing process condition, F(1, 115) = 10.08, p = 0.002 with a small effect size of η2 = 0.08.

In order to further understand the nature of the significant interaction between the timing of the prompt and writing process condition, pairwise comparisons using Least Significant Differences were calculated. There was a significant difference (p = 0.001) between the two writing conditions at the first time point but not at the second time point (p = 0.06). There was also a significant decrease for insight ratings for the poetry writing task from the first to the second prompt (p = 0.03). But the pairwise comparison for the freewriting task did not find a significant increase between the first and second prompt.

Figure 2 presents the line chart for the insight data. The findings of the insight scale section of this study can be summarized in relation to Figure 2. First there is a difference between the two writing conditions. This is substantiated both by the significant interaction and the significant between-subjects main effect for condition. The trajectory of insight development between the two writing processes is different. As clearly seen in Figure 2, poetry writing has higher initial average ratings for the Knowledge Constituting writing process (prompt 1) which is significantly reduced with the Knowledge Transforming revision task (prompt 2). Reversely, for the freewriting task we have an initial level of insight which increases at the second repetition of the Knowledge Constituting prompt but is not significantly different. While with the first prompt there is a significant difference between poetry and freewriting processes, there is no significant difference after the second writing prompt. This seems to suggest a different trajectory of response for insight in the two writing conditions.

A two-way repeated measures ANOVA with one-between and one-within subjects factor was also calculated for the emotional clarity data. Box's M-value was 2.94 with a significance level of 0.41 suggesting that there was no violation of the assumption of homogeneity of covariance matrices. The multivariate tests revealed a significant emotional clarity-prompt time x writing condition interaction, Wilk's lambda = 0.95, F(1, 113) = 6.21, p = 0.01. There was also a main effect for the timing of the prompts, Wilk's lambda = 0.96, F(1, 113) = 4.41, p = 0.04. Tests of within-subjects effects have the same results with a significant interaction (with a small effect size of η2 = 0.04) and a significant main effect for the timing of the writing prompt (with a small effect size of η2 = 0.05).

Levene's test of equality of error variances was calculated as part of the assumptions for the Test of Between-Subjects Effects. Levene's test was not significant for the initial writing prompt (F = 0.01, p = 0.91) or the second writing prompt (F = 2.93, p = 0.09). This suggests we do not have a violation of this assumption. Tests of Between-Subjects Effects did not find a significant main effect for the writing process condition, F(1, 113) = 2.98, p = 0.09.

In order to further understand the nature of the significant interaction between the timing of the prompt and writing process condition, pairwise comparisons using Least Significant Differences were calculated. As with the insight data, for the emotional clarity scales there was a significant difference (p = 0.02) between the two writing conditions at the first time point but not at the second time point (p = 0.53). There was not a significant decrease for emotional clarity ratings for the poetry writing task from the first to the second prompt (p = 0.78). But the pairwise comparison for the freewriting task found a significant increase between the first and second prompt (p = 0.002).

Figure 3 presents the line chart for the emotional clarity data. As seen in Figure 3, the direction of the two writing conditions is different. This is supported by the significant interaction between prompt time and writing condition. The slope for the poetry writing process is flat and without a significant difference for emotional clarity ratings. The slope for freewriting involves an increase with significantly higher ratings at the second prompt. At the first time point, the poetry writing process has a significantly higher rating than the freewriting prompt. But this difference disappears at the second time point. This suggests a different trajectory of response for the development of emotional clarity for the two writing processes.

Discussion

The central aim of the current study is to provide initial information on the writing processes underpinning writing-for-wellbeing by addressing the timed development of insight and emotional clarity in freewriting and autoethnographic poetry writing. The analyzed data reveals a complex pattern of responses which requires a degree of explication in order to address the current question of how self-discovery emerges.

In relation to the questions about whether self-discovery is situated in the Knowledge Constituting (text generating), the Knowledge Transforming (text revision) stages of writing or a combination of the two processes, the current results provide preliminary evidence that it is the Knowledge Constituting process which produces self-discovery. In autoethnographic poetry writing, Knowledge Constituting (text generating) produced higher levels of insight than Knowledge Transforming (text revision) and in freewriting repeated Knowledge Constituting produced higher levels of emotional clarity at the second time point. While these two results were situated in different writing processes, they both demonstrate that Knowledge Constituting (text generating) increases aspects of self-discovery. The current results do not support the hypothesis that either insight or emotional clarity is increased through the Knowledge Transforming (text revision) process. For poetry writing, there was a significant decrease in insight following a limited Knowledge Transforming (revision) process while emotional clarity stayed at the same level. Thus overall, the results presented here support the preliminary claim that Knowledge Constituting has a positive effect on self-discovery and Knowledge Transforming does not. These results explicate and support the position on text generation proposed in the dual model theory of discovery but do not support the role specified for the text revision process (Galbraith, 1999, Galbraith, 2009; Galbraith and Baaijen, 2015; Baaijen and Galbraith, 2018).

The second set of questions in this study address the development of insight and emotional clarity in two different progressions: (1) Knowledge Constituting = > Knowledge Transforming (poetry writing); and (2) Knowledge Constituting = > Knowledge Constituting (freewriting). The hypothesis from Baaijen and Galbraith (2018) is that Knowledge Transforming following Knowledge Constituting would produce increases in self-discovery. The data from the current study of autoethnographic poetry writing does not support this outcome. For the insight measure there was a significant decrease following Knowledge Transforming and for emotional clarity the outcomes basically stayed the same without a significant difference. For the repetition of the Knowledge Constituting process (freewriting) there was a non-significant increase for insight and a significant increase for emotional clarity concerning personal experience at the second prompt. The significant interaction found for writing condition and prompt timing on the insight and emotional clarity measures results from the difference in the trajectories of these different writing process progressions. Based on current data, the repetition of Knowledge Constituting would seem to be more conducive to self-discovery.

One effect was the significant difference between poetry writing and freewriting following the 1st Knowledge Constituting (text generation) prompt. For both insight and emotional clarity after the first prompt, poetry writing elicited significantly higher ratings than freewriting. It should be noted that there are two core differences between the prompts used for each writing process and each difference could have contributed to this significant result. The poetry writing prompt directs the participant to relive in sensory terms the experience they are thinking of and requests that the participant focus on a highly significant event. The freewriting prompt only has the requirement that the writer continue to write for 3 min without stopping and focuses on an everyday event. The data shows that the focusing on sensory information concerning a significant event elicits high levels of insight and emotional clarity. Since the current study did not have a baseline with which to compare the two genres, it is unclear if it is the significance of the event or the reliving through sensory information that directs this increase in ratings. While this result is interesting, it needs to treated with some caution because of both the potential confounding and lack of baseline data. However, it is possible that an increased focus on significant events and sensory data increases the self-discovery effects of this Knowledge Constituting prompt. Theoretically this would be in line with Galbraith and Baaijen (2015) claims for Knowledge Constituting.

There are limitations to the current study that should be addressed in the evaluation of the results presented here. First, the writing process explored here was exceedingly short and consisted of only 6 min of writing. The usual format of both freewriting and poetry writing involves a much longer time line. This might be especially important for the Knowledge Transforming (text revision) stage of the poetry writing process. Just 3 min for evaluation, revision and rewriting might not be enough to really complete this type of writing. Hence, the results that show detrimental effects for Knowledge Transforming on insight should be considered preliminary. A longer timeline might produce higher levels of insight and indeed the results presented involving decreases in insight might just be an initial stage before new insight evolve and part of a process by which initial insights are dislodged so that new insights can emerge. Second since the writing processes used in the current study were modeled on existing genres, the design is not perfectly symmetrical. This leads to some open questions about what led to the current results. A more complete design would have had conditions for focusing on significant and everyday events, direct elicitation of sensory data, and would have had a repeated text production process for poetry and a text revision condition for freewriting. This asymmetrical design based on existing writing practices for autoethnographic poetry and freewriting does include some confounding that will require additional research to resolve. Thirdly, the current design did not include any baseline evaluations. Thus, any comparisons between the two genres are not really possible as we do not know if this a random group effect or the result of the intervention type. Finally, this is a relatively small-scale study with only 50± participants in each writing condition. Larger scale data would be helpful in providing a more solid basis for the results presented here.

To date, we only have one type of writing that has been extensively studied in terms of its effect on wellbeing. Expressive writing has been shown to produce positive effects on wellbeing (Lepore et al., 2002; Frattaroli, 2006; Pennebaker and Chung, 2007; Lepore and Kliewer, 2013; Kállay, 2015). In terms of the results of the current study, certain writing processes seem to underpin these effects. First, expressive writing is similar to freewriting in that it involves repeated writing on the same experience. Secondly it involves the instruction of not focusing on linguistic form or accuracy. As such, expressive writing is basically a repeated Knowledge Constituting writing process. Expressive writing also shares an aspect of the poetry writing process in that the request is to write about a significant event. Overall, based on the current results expressive writing repeated over several iterations focusing on significant and traumatic personal events should elicit increases in both insight and emotional clarity. The theoretical explanation for this would seem to reside in the increased amount of information that is disclosed through the movement of non-verbal and sensory information into written text which provides more detail relating to the experience itself. Thus, the Knowledge Constitution writing process facilitates a process of conscious psychological disclosure concerning the experience. The current study points to the ways in which the actual writing process involved in expressive writing might function in facilitating wellbeing.

The aim of the current study was to provide some initial data on the writing processes of self-discovery which may underpin the development of wellbeing. The main finding of the current study is that Knowledge Constituting elicits high levels of insight and may increase emotional clarity following a repetition. Autoethnographic poetry writing and freewriting involved different trajectories to achieve self-discovery. For poetry writing, it was the writing prompt which asked for sensory information and a significant event that produced high levels of insight and emotional clarity. For freewriting, it was the repetition of the text production process that increased emotional clarity. Both of these processes could be easily replicated in a variety of educational, research and clinical settings for both investigating and improving wellbeing.

The study also offers two new genres that can be used in future research on the ways in which writing can enhance wellbeing. Far more research, with a wider set of genres needs to be conducted in order to understand the ways in which writing can offer relief to writers and enhance their wellbeing. The hope is that this study which provides initial results in this direction will encourage others to further investigate these issues.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because protected by IRB statement that this should not be shared with anyone beyond the researcher. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to aGFuYXVlckBpdXAuZWR1.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by IRB Indiana University of Pennsylvania. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

The design, data collection, analysis, and writing were all conducted by DH.

Funding

Publication fees for this article were paid by the Faculty Publication Support Fund 22-223 from Indiana University of Pennsylvania.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Antal, H. M., and Range, L. M. (2005). Psychological impact of writing about abuse or positive experiences. Violence Victims 20, 717–728. doi: 10.1891/088667005780927458

Armstrong, C. (1984). A Process Perspective in Poetic Discourse (Report No. CS 208-227). New York, NY: Conference on College Composition and Communication.

Armstrong, C. (1985). Tracking the Muse: The Writing Processes of Poets (Report No. CS 209-683). Cambridge: Conference on College Composition and Communication.

Armstrong, C. (1986). The Poetic Dimensions of Revision. New Orleans, LA: Conference on College Composition and Communication.

Baaijen, V. M., and Galbraith, D. (2018). Discovery through writing: relationships with writing processes and text quality. Cogn. Instruct. 36, 199–223. doi: 10.1080/07370008.2018.1456431

Bereiter, C., and Scardamalia, M. (1987). The Psychology of Written Composition. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Danoff-Burg, S., Agee, J. D., Romanoff, N. R., Kremer, J. M., and Strosberg, J. M. (2006). Benefit finding and expressive writing in adults with lupus or rheumatoid arthritis. Psychol. Health 21, 651–665. doi: 10.1080/14768320500456996

Deveney, C., and Lawson, P. (2021). Writing your way to well-being: an IPA analysis of the therapeutic effects of creative writing on mental health and the processing of emotional difficulties. Counsell. Psychother. Res. 22, 1–9. doi: 10.1002/capr.12435

Elbow, P., and Belanoff, P. (2000). A Community of Writers: A Workshop Course in Writing. Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill.

Fishman, S. M. (1997). Student writing in philosophy: a sketch of five techniques. New Direct. Teach. Learn. 69, 53–66. doi: 10.1002/tl.6905

Flower, L. S., and Hayes, J. R. (1980). The cognition of discovery: defining a rhetorical problem. College Composit. Commun. 31, 21–32. doi: 10.2307/356630

Frattaroli, J. (2006). Experimental disclosure and its moderators: a meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 132, 823–865. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.6.823

Furman, R. (2004). Using poetry and narrative as qualitative data: exploring a father's cancer through poetry. Families Syst. Health 22, 162–170. doi: 10.1037/1091-7527.22.2.162

Furman, R. (2006). Poetic forms and structures in qualitative health research. Qual. Health Res. 16, 560–566. doi: 10.1177/1049732306286819

Galbraith, D. (1999). “Writing as a knoweldge constituting process,” in Knowing What to Write: Conceptual Processes in Text Production, eds M. Torrance and D. Galbraith (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press), 139–160.

Galbraith, D. (2009). Writing as discovery. Brit. J. Educ. Psychol. Monogr. Ser. II 6, 5–26. doi: 10.1348/978185409x421129

Galbraith, D., and Baaijen, V. M. (2015). “Conflict in writing: actions and objects,” in Writing(s) at the Crossroads: The Process/Product Interface, ed G. Cislaru (Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing), 253–276. doi: 10.1075/z.194.13gal

Gerrish, D. T. (2004). An examination of the processes of six published poets: seeing beyond the glass darkly (Ph.D. dissertation). New Brunswick: Rutgers, State University of New Jersey.

Giorgi, A., Giorgi, B., and Morley, J. (2017). “The descriptive phenomenological psychological method,” in The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research in Psychology, 2nd Edn., eds C. Willig and W. Stainton Rodgers (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage), 176–191. doi: 10.4135/9781526405555.n11

Graf, M. C., Gaudiano, B. A., and Geller, P. A. (2008). Written emotional disclosure: a controlled study of the benefits of expressive writing homework in outpatient psychotherapy. Psychother. Res. 18, 389–399. doi: 10.1080/10503300701691664

Grant, A. M., Franklin, J., and Langford, P. (2002). The self-reflection and insight scale: a new measure of private self-consciousness. Soc. Behav. Pers. 30, 821–836. doi: 10.1037/t44364-000

Gratz, K. L., and Roemer, L. (2004). Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 26, 41–54. doi: 10.1023/B:JOBA.oooooo7455.08539.94

Hanauer, D. (2010). Poetry as Research: Exploring Second Language Poetry Writing. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. doi: 10.1075/lal.9

Hanauer, D. (2021). “Poetic writing research: the history, methods, and outcomes of poetic (auto) ethnography,” in Handbook of Empirical Literary Studies, eds D. Kuiken and A. Jacobs (Berlin; Boston, MA: De Gruyter), 421–448. doi: 10.1515/9783110645958-017

Hanauer, D. I. (2020). Writing mourning: a poetic autoethnography on the passing of my father. Qual. Inq. 27, 37–44. doi: 10.1177/1077800419898500

Hockemeyer, J., and Smyth, J. (2002). Evaluating the feasibility and efficacy of a self-administered manual-based stress management intervention for individuals with asthma: results from a controlled study. Behav. Med. 27, 161–172. doi: 10.1080/088964280209596041

Kállay, E. (2015). Physical and psychological benefits of written emotional expression: review of meta-analyses and recommendations. Eur. Psychol. 20, 242–251. doi: 10.1027/1016-9040/a000231

Langer, C. L., and Furman, R. (2004). Exploring identity and assimilation: research and interpretive poems. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung 5, 1–13. doi: 10.17169/fqs-5.2.609

Lepore, S. J., Greenberg, M. A., Bruno, M., and Smyth, J. M. (2002). “Expressive writing and health: self-regulation of emotion-related experience, physiology, and behavior,” in The Writing cure: How Expressive Writing Promotes Health and Emotional Well-Being, eds S. J. Lepore and J. M. Smyth (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association), 99–117.

Lepore, S. J., and Kliewer, W. (2013). “Expressive writing and health,” in Encyclopedia of Behavioral Medicine, eds M. D. Gellman and J. R. Turner (New York, NY: Springer), 735–741.

Lepore, S. J., and Smyth, J. M., (eds.). (2002). The Writing Cure: How Expressive Writing Promotes Health and Emotional Well-Being. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Li, L. Y. (2007). Exploring the use of focused freewriting in developing academic writing. J. Univ. Teach. Learn. Pract. 4, 1–16. doi: 10.53761/1.4.1.5

Liu, S., Erkkinen, M. G., Healey, M. L., Xu, Y., Swett, K. E., Chow, H. M., et al. (2015). Brain activity and connectivity during poetry composition: toward a multidimensional model of the creative process. Hum. Brain Mapp. 36, 3351–3372. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22849

McGuire, K. M. B., Greenberg, M. A., and Gevirtz, R. (2005). Autonomic effects of expressive writing in individuals with elevated blood pressure. J. Health Psychol. 10, 197–207. doi: 10.1177/1359105305049767

Nishith, P., Resick, P. A., and Griffin, M. G. (2002). Pattern of change in prolonged exposure and cognitive-processing therapy for female rape victims with posttraumatic stress disorder. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 70, 880–886. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.4.880

Norman, S. A., Lumley, M. A., Dooley, J. A., and Diamond, M. P. (2004). For whom does it work? Moderators of the effects of written emotional disclosure in a randomized trial among women with chronic pelvic pain. Psychosom. Med. 66, 174–183. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000116979.77753.74

Pennebaker, J. W. (1993). Putting stress into words: Health, linguistic and therapeutic implications. Behav. Res. Ther. 31, 539–548.

Pennebaker, J. W., and Beall, S. K. (1986). Confronting a traumatic event: toward an understanding of inhibition and disease. J. Abnormal Psychol. 95, 274–281.

Pennebaker, J. W., and Chung, C. (2007). “Expressive writing, emotional upheavals, and health,” in Silver Foundations of Health Psychology, ed H. S. Friedman (New York, NY: Oxford University Press), 263–284.

Peskin, J., and Ellenbogen, B. (2019). Cognitive processes while writing poetry: an expert-novice study. Cogn. Instruct. 37, 232–251. doi: 10.1080/07370008.2019.1570931

Pituch, K. A., and Stevens, J. P. (2016). Applied Multivariate Statistics for the Social Sciences, 6th Edn. New York, NY: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315814919

Prendergast, M. (2009). “Introduction: The phenomena of Poetry in research,” in Poetic Inquiry: Vibrant Voices in the Social Sciences, eds M. Prendergast, C. Leggo, and P. Sameshima (Rotterdam: Sense Publishers), xix–xlii.

Range, L., and Jenkins, S. R. (2010). Who benefits from Pennebaker's expressive writing? Research recommendations from three ender theories. Sex Roles 63, 149–163. doi: 10.1007/s11199-010-9749-7

Richardson, L. (1990). Writing Strategies: Reaching Diverse audiences. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. doi: 10.4135/9781412986526

Richardson, L. (1997). “Poetic representation,” in Handbook of Research on Teaching Literacy through Communication and Visual Arts, eds J. Flood, S. Brice Heath, and D. Lapp (New York, NY: Simon and Schuster Macmillan), 232–238.

Richardson, L. (2003). “Writing: a method of inquiry,” in Collecting and Interpreting Qualitative Materials, eds N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage), 499–541.

Rosenberg, H. J., Rosenberg, S. D., Ernstoff, M. S., Wolford, G. L., Amdur, R. J., Elshamy, M. R., et al. (2002). Expressive disclosure and health outcomes in a prostate cancer population. Int. J. Psychiatry Med. 32, 37–53. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0192729

Schwartz, M. (1983). Two journeys through the writing process. Coll. Composit. Commun. 32, 188–201. doi: 10.2307/357406

Somerville, E. M., and Crème, P. (2005). Asking Pompeii questions: a co-operative approach to writing in the disciplines. Teach. Higher Educ. 10, 17–28. doi: 10.1080/1356251052000305507

Keywords: poetry, writing, expressive writing, wellbeing, insight, discovery, emotional clarity, autoethnography

Citation: Hanauer DI (2022) The writing processes underpinning wellbeing: Insight and emotional clarity in poetic autoethnography and freewriting. Front. Commun. 7:923824. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2022.923824

Received: 19 April 2022; Accepted: 21 September 2022;

Published: 13 October 2022.

Edited by:

Guan Soon Khoo, University of Texas at Austin, United StatesReviewed by:

Jennifer E. Graham-Engeland, The Pennsylvania State University (PSU), United StatesEileen Bendig, University of Ulm, Germany

Copyright © 2022 Hanauer. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: David I. Hanauer, aGFuYXVlckBpdXAuZWR1

David I. Hanauer

David I. Hanauer