- 1Department of Media Studies, Institute of Cultural Studies (Institut für Kulturwissenschaft), Koblenz, Germany

- 2Fachbereich, University of Koblenz-Landau, Koblenz, Germany

The aim of this article is to explain multimodal coherence-making as a transcribing practice and how this can be used to teach multimodal, narrative, and media competences in different genres. In multimodal arrangements, language makes images readable in specific ways and images make language understandable in different ways. This results in an abductive understanding process that can be used in teaching and learning contexts. This idea of meaning-making is based on the social semiotic approach of style. According to the understanding of semiotic meta functions, this approach considers style as the practice of selecting, forming, and composing semiotic resources. These stylistic practices realize a subjective appropriation of discursive and habitual patterns, which are carried out within the semiotic and technological dispositions (affordances) of the situationally used media infrastructures. In this sense, digital storytelling is a multimodal style practice with digital tools. Multimodal storytelling in educational contexts means that teachers and learners are prompted to bring the communicative functions of text, image, video, and audio into narrative coherence. Based on a journalistic Instagram story, this article reconstructs the media-practical, multimodal, and narrative skills that are prototypically necessary. Based on this analysis, these competencies are operationalized to make them usable for new teaching/learning arrangements using digital storytelling.

Introduction

“The teaching professions face rapidly changing demands, which require a new, broader, and more sophisticated set of competences than before. The ubiquity of digital devices and applications, in particular, requires educators to develop their digital competence.” (Redecker, 2017).

The European Commission describes the current teaching/learning situation on its website for its educational policy initiative as “The European Framework for the Digital Competence of Educators” (European Union, 2017). The concept of digital storytelling presented in this contribution relates to this initiative in two ways. On the one hand, digital stories can be used to communicate knowledge in an addressee-oriented manner. On the other hand, digital storytelling can be used as a production-oriented learning practice for knowledge acquisition. This contribution focuses on the second practice. It assumes that the creative and narrative processing of knowledge through media not only trains learners in practical media competence, but also allows the knowledge to be transferred into sustainable application strategies. However, these strategies aim at the semiotic and narrative production of coherence under the influence of media infrastructures (or digital media dispositif). For this reason, this contribution begins by clarifying these influences before turning to coherence making as a transcribing learning practice.

It is positive that the policy initiative of the EU is no longer limited to just imparting media technical skills. The focus is on the ability to analyze and reflect on digital information and to handle it responsibly. Communicative skills that are necessary for collaborative work and for the production of media content are also emphasized. This specification can be implemented through the method of digital storytelling. It is a didactic and methodical instrument that teachers can use to enable learners to process topics and educational subjects in a narrative manner and to reconstruct them creatively. To do this productively, three crucial communicative skills are required from a social semiotic or media semiotic point of view (cf. Bateman et al., 2017): theoretical and practical media, semiotic-multimodal, and rhetorical-narrative competences. Thus, the semiotic awareness of the communicative function of different semiotic modes and the knowledge of the formative influence of the media infrastructure on communication become constitutive of digital competences. Furthermore, in digital storytelling, these competences are not only used in an analytical way, but also for a creative transfer. To meet these challenges in a creative and motivating way, this article presents the first draft concepts of social semiotic didactics of digital storytelling. Such didactics are currently being developed in a more extensive research context to support digitization in schools and universities (DigiKompASS) at the University of Koblenz. DigiKompASS is funded by the “Foundation Innovation in University Teaching”.

The goal of the project is to give teachers epistemological, media theoretical, and specific didactic-methodological orientation regarding how digital tools can be used in the specific teaching context for producing stories. It has to be taken into account that learners with their smartphones already have digital all-rounders in their pockets; they constantly use them in daily (social media) life to tell stories about themselves and others or events in a multimodal manner. Moreover, schools and universities are also increasingly equipped with digital infrastructures in the course of digitization initiatives in teaching. Didactics of digital storytelling attempt to show ways in which digital tools can be used to produce text, photography, audio, and video to convert school or scientific content into digital stories. The methods developed in the project DigiKomPASS take the learners' everyday social media practices as a starting point and use their media routines to acquire specific knowledge. The aim is to impart medial, multimodal, and narrative skills to ensure empowered participation in the digital world (cf. Council of Europe, 2022). Learners and teachers should be able to produce and receive digital forms of communication such as “scrollytelling,” slidecasts or podcasts, titled picture galleries, etc. This makes it necessary to consciously deal with the medial and semiotic potential of the different forms of digital communication as well as with their socially conventionalized genre regimes to communicate successfully.

Medial, semiotic, and narrative skills require the ability to create coherence. This contribution considers this creation of coherence as a central learning act. In the media-technical field, the selection and application competence of certain digital tools is required to bring the technical knowledge and the creative possibilities of the learners into a coherent relationship with the communicative goals. In the semiotic field, the aim is to change different semiotic resources, which can be used through the selected media, into coherent messages. And in the narrative field, the required skillset is ultimately about creating coherence by developing the plot logically and/or making it interesting dramaturgically.

Epistemically, digital storytelling didactics assume that the abductive construction of these coherences between language and image elements in a specific medial infrastructure (media dispositif) and their arrangement according to narrative logics result in a special learning process. According to Jäger (2002), this abductive creation of coherence is conceptualized as a transcribing practice. This is meaning-making, which makes one semiotic resource legible through the others. In this process, mental scripts of the signs are produced, which are abductively combined to construct coherence. This happens when the communicators recognize the semantic connections between the semiotic resources by making some aspects of the cultural and situational contexts relevant. Certain elements are thereby made salient accordingly, while others fade into the background. This multimodal framing (cf. Kress, 2010) is part of the learning process as a transcribing coherence-making practice.

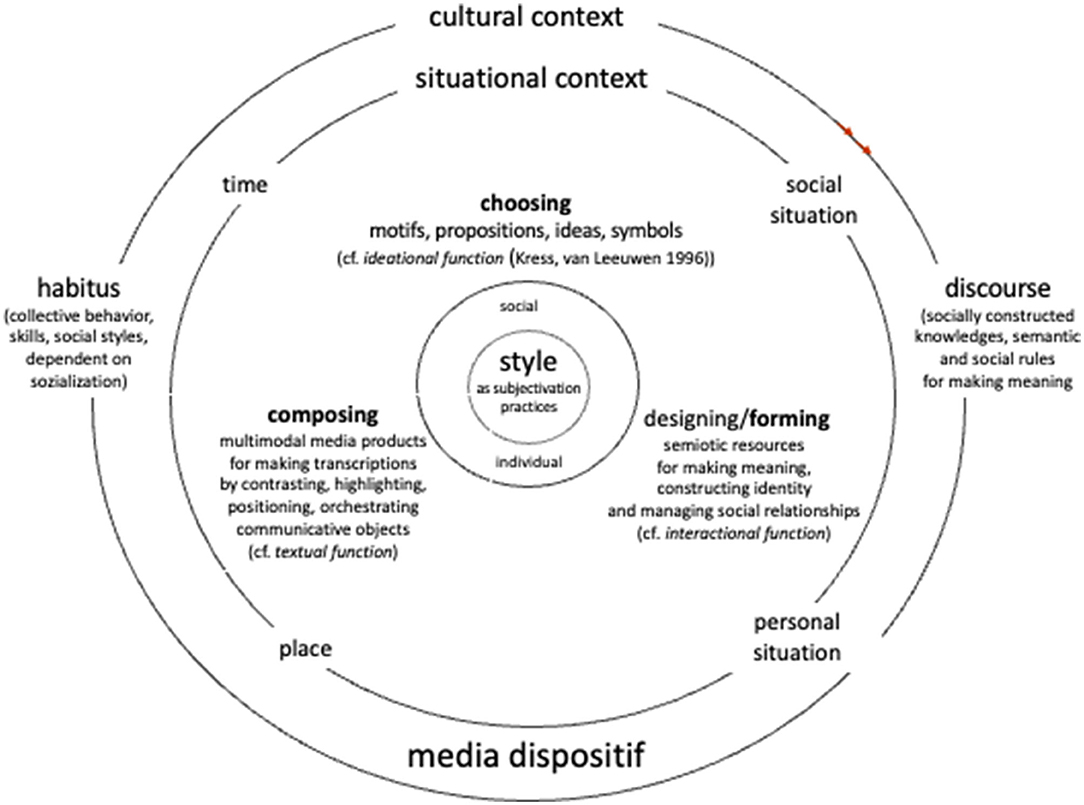

To bring these multimodal phenomena into a narrative coherence, journalistic genres such as reports or features are used. This gives dramaturgical and stylistic orientation about what is happening around the protagonists and their identity-constructing actions. Often this could happen through a protagonist who is confronted with certain factual or personal challenges that they have to deal with in the process of the story. In the story, the protagonists present themselves in a specific appearance and interaction with their situational, spatial, and social contexts. The resulting performances give them a certain identity. To achieve this, teachers and learners need a clear understanding of these narrative practices as semiotic and medial work. They need to know how identity can be constructed using certain semiotic modes in certain situational and cultural contexts. This is done through style practices, which are the identity-creating selection (choosing), shaping (forming), and composing of semiotic resources. According to the social semiotic metafunctions (representational, interactive, and compositional functions, cf. Kress and van Leeuwen, 2021), these style-practices are carried out under subjective consideration of communicative-discursive and habitual patterns in certain media settings. Thus, a reflective approach to this media infrastructure requires its conceptual explication.

In accordance with these conceptual frameworks, media, semiotic/multimodal, and narrative competences are subsequently defined and described as practices of digital storytelling. Finally, a journalistic Instagram story is presented analytically to show how digital storytelling could be implemented ideally. The aim is to show which media, semiotic, and narrative practices are used in this story to enable a corresponding didactic and reflective transferability to the teaching context. This reference to journalistic storytelling should serve as an inspiration for the production of stories in the classroom, as journalism has been experimenting with different formats of digital storytelling for a long time. Even in such a supposedly simple format as the Instagram story, the necessary media, semiotic, and narrative skills are already evident. These can be transferred to other formats of digital storytelling such as multimodal “scrollytelling.” Audio and video formats, such as podcasts or explanatory videos, can also be created with these skills because of the ability to assess the media-technical, semiotic and narrative potential of the tools used for this.

Media Competence: Reflexion on the Digital Media Dispositif as the Institutional Context of Digital Storytelling

Digital storytelling is practiced with digital media. First, these offer a plenum of semiotic modes: moving images, text, and sound can also be used instead of just photographs, diagrams, and spoken words. Moreover, digital media also structure these multimodal communication practices. Therefore, it makes sense for teachers and learners to deal with this digital infrastructure conceptually. An established concept for this approach is the notion of media dispositif. Dispositif is a notion that translates Foucault's (1980) understanding of multidirectional and multifaceted power relations and their effects into an analytical category. With regard to the media dispositif, there are two dominant principles that organize communication behavior in digital media contexts and the interpretation of media content. First, there is the technical infrastructure with certain material affordances. It is the canvas that structures the semiotic toolbox and the accessibility of the addressees as well as the possibility of reciprocal interaction (Bateman et al., 2017; Stöckl, 2019, p. 64). Then, there are certain rules of communication and role models, which are based on genre specifications. Both principles rely on the participants' knowledge of the media interaction and its cultural and situational contexts. The cultural context provides the semantic rules and the hegemonic knowledge in the form of discourses. The genre rules and style patterns are also adopted mimetically by (media) socialization and are enacted by habitual social styles. Situational contexts are the media infrastructures that are used for concrete communication, including their specific affordances (Meier, 2021).

Such didactic reflections are very important for practical use in existing teaching contexts. Digital storytelling projects must be closely coordinated with the curriculum and other subjects. A complete teaching unit is particularly suitable for a first attempt in which the teacher can work on an easily accessible topic using a simple media infrastructure. In this way, teachers can familiarize themselves with the desired and given affordances of the available digital devices, such as smartphones and authoring tools, and can choose the right one for their teaching goals. The technical media affordances structure how the semiotic practices are materialized (textual, pictorial, and audiovisual) and how the communication is constituted (one-directional or bidirectional communication and synchronic or asynchronic communication). Teachers and learners need to know which semiotic functions the chosen tools provide and how they can be used for effective messages. With regard to the functional, economic, and legal conditions, individual camera apps and post-processing tools as well as the possible formats of the publication must be considered.

The reflection on the media dispositif is not limited to the relationship between media affordances and the subject, but also includes its institutional character, which has conventionalized certain systems of knowledge and modes of behavior. In the teaching context, there must also be clarity about licensing and copyright matters: which images can be used, or how can researched texts be edited? Questions of media ethics also need to be clarified: what can be said and what cannot be said or what can be shown and what cannot be shown?

These sociocultural expectations are also enacted by the orientation toward certain genre conventions within a particular discourse. While a discourse allows meanings to be realized within a particular universe of ideas that has a socio-conceptual location, the genre offers a schematic structure supporting the achievement of certain communicative purposes (Swales, 1990, p. 58; Kress, 2010, p. 114). Moreover, genre mediates between social and semiotic by helping to determine the social as well as the communicative function of a communicative act. In this sense, genres are communicative patterns that help to create messages and respond to them in a socially acceptable way as well as to understand these messages within the semantic universe of a particular discourse. Thereby, they are characterized by typical content and plots organized by “certain rules, prescriptions, traditions, ingrained habits, role models, etc.” (van Leeuwen, 2004).

Reflecting on which genre to choose is also essential when planning the courses, as this provides orientation for the semiotic and narrative design of the stories that the learners are supposed to produce. Based on the journalistic genre of reportage or feature, for example, factual information can be enacted in a way it exits and close to personal experiences.

Bateman et al. (2017) conceptualized the interplay of media material, semiotic modes, discourse semantics, and communicative genres in an innovative model of the canvas of the media, which also makes the special nature of digital storytelling clear. It describes how media materiality is related to the social rules of communication. Bateman et al. call the surface of the media canvas because it is the material ground on (through) which semiotic resources materialize or appear. This medial materialization process of the signs is also part of the meaning-making process in the sense of McLuhan (2001) the medium is the message. By giving the materialized phenomena sign functions, the media consumer turns them into a meaningful regularity because this meaning-making process articulates certain discourse semantics with certain social rules and conventions. According to these media-theoretical concepts, the digital stories produced in the teaching/learning context can not only be planned and designed, but also evaluated. The concepts make the necessary interplay of medial, semiotic, and narrative skills clear. While the media skills were treated primarily as competent handling of media affordances, this article focuses more strongly on the semiotic or multimodal and narrative skills in the production of digital stories and their effects on learning.

Multimodal Competence: Transcriptivity as an Abductive Doing of Multimodality

Multimodal competence for digital storytelling is the ability to select, design, and compose semiotic resources in a narrative manner. This requires knowledge of the communicative functions of semiotic resources and their meaningful interaction (O'Halloran and Victor, 2014). In order to clarify this interaction in the production and reception process of digital storytelling, the concept of transcriptivity might be helpful. Consequently, multimodal competence is the ability of coherent transcribing. Transcriptivity focuses on meaning-making by the correspondence of the same and different modalities of semiotic resources, such as language and image. The reference to a certain discursive knowledge is generated through the intersemiotic transcription of different semiotic modes (Jäger, 2002, p. 28). Based on the semiotic model of de Saussure, Jäger assumes that only the coupling of different tokens or types of signs makes them mutually readable. The media linguist Holly (2015) explains this principle as a result of various “transcription” processes, such as paraphrasing, explication, explanation, commentary, or translation, which are either “intramedial” (mediating within the same semiotic mode) or “intermedial” (mediating between different semiotic modes). For example, a term is transcribed “intramedialy” if it is explained in more detail below. An image is transcribed “intermedialy” if it is combined with a verbal title and the recipients create a coherent unit of meaning.

Jäger (2002, p. 30) describes these coherent making transcriptions as dynamic processes. They consist of an interplay between pretexts, scripts, and transcripts in the semiotic work of an individual, with the scripts to be understood as overrides or translations that are derived from the pretexts (e.g., language or pictorial symbols) as transcripts. The meaning of an audiovisual text or video is generated through the interpretative merging of the created pretext meanings of the various semiotic modes, such as moving images and spoken language, into an integrating transcript, which constitutes the multimodal text meaning of a certain “scrollytelling” or Instagram story, YouTube video, etc. The principle of transcriptivity is also effective in video editing, which is made up of different cuts and sequences that are put together dramatically by the producer, and the viewer transcribes the individual sequences into a coherent plot.

While the concept of transcriptivity makes the practice of meaning-making in the mutual reference of signs plausible, it still leaves two gaps:

1. How does the reference to the world take place in this practice?

2. How are priorities organized in this practice?

To answer the first question, I refer to Bateman et al. (2017). They describe the process of meaning-making as an abductive discourse interpretation. With reference to the meaningful discourses about the world, this is brought into connection with the signs (signified/signifier). Bateman et al. (2017, p. 63) summarize:

“Discourse interpretation is a form of abductive reasoning where the sign-user, or person interpreting some signs, makes hypotheses in order to ‘explain' the coherence of what they are interpreting. This crucial facet of sign use has been neglected for a long time but is now beginning to reassert itself as the actual process of making meanings comes back into the foreground. The notion of interpretation as making discourse hypotheses can be usefully applied in linguistics in relating parts of a text to one another; but it can equally well be applied in visual studies to combining contributing parts of an image.”

They also explain “abductive reasoning” as a “process of abduction that can be described as ‘reasoning to the best explanation'.” This statement leads to question two, which abduction does not fully explain. Priorities or saliences are realized through subjective orientation to discursively mediated concepts of normality. These concepts are suggested by the cultural and situational contexts of current communication. The subjective relevance of the communicators is based on dealing with these contexts. Thus, this setting of relevance does not take place autonomously, but is a dialectic result of individual and social style practices. These notions of normality are also a legacy of the subjective appropriation of social norms. Relevance is thus expressed as multimodal framing, which highlights certain semiotic performances of certain aspects of discourse more than others. This focus (salience) also shows which discourse aspects in this communication situation count as said or showable and which tend not to be discussed. The multimodal framing described here organizes the coherent selection, formation, and composition of the semiotic resources used for communication, and multimodal storytelling as well as their discourse-representing function. Digital storytelling then creates awareness of these meaningful practices and trains the rhetorical, strategic, or narrative use via digital media. This is explained in more detail in the following section.

Narrative Competence: Stylish Identity-Telling as an Educational Hero's Journey

The affordances of the digital media dispositif constantly animate users to receive and produce digital stories. Family, friends, and members of professional organizations communicate increasingly with digital audio and text messages as well as photographs and videos. Stories are often told in order to be considered esthetically pleasing, trustworthy, and reliable. People express themselves or give information through stories. Social success is more and more dependent on self-presentation on social media applications and the stories you tell there. Conceptually, this can be described with Goffman's (1956) notion of presentation of self in the everyday life and with Bourdieu's (1986) concept of social capital. The users construct identity through impression management, which is accomplished through semiotic work.

Young people, in particular, use their smartphones this way. They make themselves the protagonist of these. Therefore, it makes sense to use this narrative motivation for teaching stories (cf. Rubio-Hurtado et al., 2022). To do so, existing storytelling skills must be further professionalized. To increase narrative competence, teaching should therefore combine findings from multimodality research with practices of professional storytelling from journalism or literature. Multimodality research reconstructs the different functions of modalities in the semiotic work. The affordances of semiotic modes also refer to their potentials and limitations in their representational functions. Kress, for example, describes the different logics of the modes of image and language this way:

“The resources of the mode of image differ from those of either speech or writing. (…) While speech is based on the logic of time, (still) image is based on the logic of space. It uses the affordances of a surface: whether page or canvas, a piece of wall or the back or front of a T-shirt. In image, meaning is made by the positioning of elements in that space, but also by size, colour, line and shape. Image does not ‘have' words; it uses ‘depictions'. Words can be ‘spoken' or ‘written', images are ‘displayed'” (Kress, 2010, p. 82).

Thus, the different affordances of modes can be used for digital storytelling. But according to Stöckl (2019, p. 65), a distinction must be made between semiotic and medial affordance, which is dealt intensively below.

Images enable the communicator to show objects simultaneously and in detail; written or spoken words make something rational plausible. These modes locate objects in the space–time continuum. Looking at it in this way, affordances of modes and media are materialized in any media product. The production and reception of these narrative products are shaped by the influences of the cultural contexts habitus and discourse which, on the one hand, have led to the specific material affordances of signs and media and, on the other hand, have constituted the social rules for their use. This manifests itself in the media dispositif, in which the media-material infrastructure with a certain specific pattern of communication (genre conventions) comes together. Thus, the habitus suggests the social rules of communicative behavior as social conventions of style practices. The relevant (hegemonial) discourse formation provides the framework of knowledge or the semantic rules. For teaching digital storytelling, this means that the discourse practices (topics, terminology, and topoi) of the specific subject or discipline must be taken into account. While cultural and social science subjects have always told stories about overcoming cultural and social challenges, natural science subjects first have to develop ways of narrating their findings. However, data and science journalism also demonstrate very well how such findings can be transferred into narrative formats. This is why the last section of this contribution will illustrate such a narrative version of a natural scientific topic.

The example shows how the plot can be influenced by situational, contextual factors like the place, the time or the social status in which the protagonist interacts.

The model of style (Figure 1) surveys the dimensions of multimodal storytelling. It clarifies how the storyteller chooses, forms, and composes semiotic resources to make messages communicable in cultural and situational contexts. In this sense, semiotic modes are stylized artifacts (cf. van Leeuwen, 2021) that are materialized through and with different sorts of media, depending on their respective affordances.

Figure 1. Style practices as multimodal construction of identity in the form of subjective choosing, forming, and composing semiotic resources (cf. Meier, 2014).

Within these implicit potentials and limitations of the cultural and situational contexts, the learners do the storytelling in their own styles. This “personal stylistic way” is how the semiotic resources (like lines, shapes, space, or sound) are chosen, formed, and composed depending on the goals of the storyteller and how they prioritize the context factors. These style practices (Figure 1) are the semiotic work needed to construct a protagonist's identity, more specifically, the way the semiotic resources are intentionally chosen, formed, and composed to constitute this character and how they (inter)act in certain environments signals taste, attitude, and their ability to change the plot of the story.

From the recipient's point of view, the stylistic performance of the protagonist indicates unintentionally whether their self-presentation and communicative problem-solving are successful or not in a narrative-logical manner. It is successful if the recipient attributes coherence to the protagonist identity and their actions in the story framework and if the differently used semiotic resources and modes can be transcribed into a coherent multimodal text with an overall message. To carry out this in a semiotically functional and narratively exciting way, the medial, multimodal, and narrative skills need to be trained. The following section is intended to illustrate this semiotic work using a journalistic example taken from the internet. In this way, a professional example of digital storytelling is used as an ideal type. It is intended to provide orientation for factual storytelling in the teaching/learning context.

Style Practices for Storytelling: an Example

This section illustrates how digital storytelling can be used to communicate knowledge as a creative documentation of learning. The example is a very simple form of multimodal storytelling. However, it shows prototypical features that can also be transferred to more complex formats such as “scrollytelling” reports. In the following, the production of such multimodal storytelling in the format of an Instagram story for training practical media, multimodal, and narrative competence will be shown.

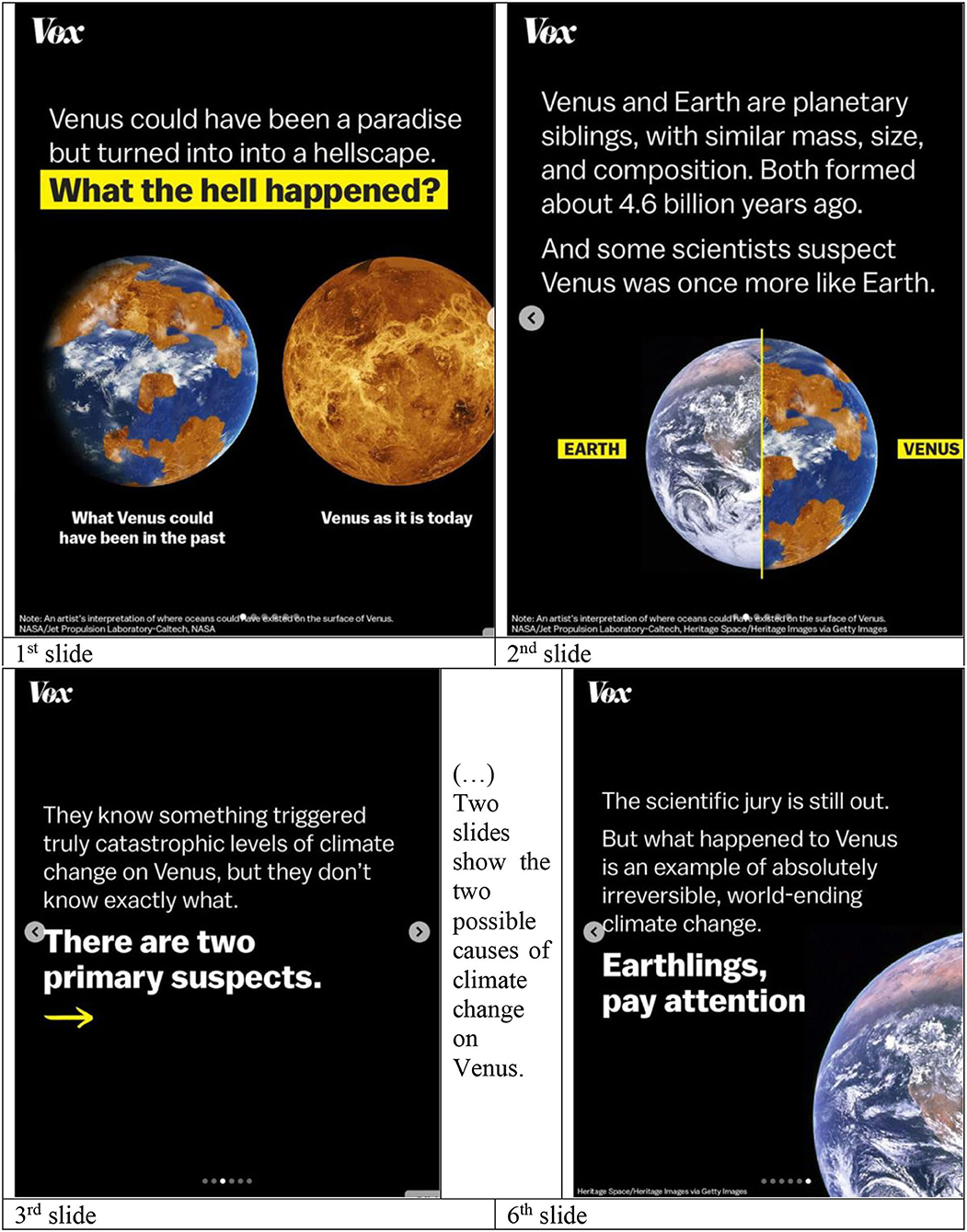

The example comes from the Instagram presence of the news provider Vox Media. The main news website Vox (https://www.vox.com) was launched in 2018. The philosophy of Vox and its cross-media online journalism is to present knowledge and breaking news in a media-appropriate and user-friendly format. They use their home page and channels on YouTube, Facebook, and Instagram, and the news and stories they present are adapted to these different forms of online communication. The Instagram story about the possible climate change on Venus and a comparison to a possible future of climate change on Earth is used here as an example. The screenshots show four of the six slides. The accompanying Instagram post is combined with text that appears permanently next to the slides and is scrollable. However, this is not further considered here.

Digital skills in the form of practical media, multimodal, and narrative skills are illustrated using an example story.

Dealing With the Media Dispositif as Media Competence

The media-practical competence expresses itself in the media product. This includes the production of individual slides and their publication on Instagram. The slides must be designed according to the media conditions of Instagram, especially in terms of format, slide counts, and text length. The layouts can be designed using a graphic program, such as Photoshop or InDesign. However, they can also be made by means of templates or for free in special Instagram posting tools, such as Canva (canva.com) or Adobe Cloud Express (previously: Adobe Spark). All these tools have their own technical prerequisites that need to be mastered. Especially, the intuitively fast and useful templates have strong restrictions on the individual design options. However, they also offer a lot of benefits because design skills such as changing the color, shape, or proportions are not required. While text production for Instagram only has to deal with the constraints of the Instagram content management system, photograph, and graphic processing depend on the design competence of the producer and their tools. Instagram also offers some image-editing tools for this purpose; however, these are limited and hardly suitable for further postproduction. Here, it is up to the media-practical competence of the teacher to assess this. In addition, if Instagram is to be used in a school context, for example, data protection issues and privacy concerns must of course be taken into account. This is also part of the necessary media competence of the teacher. Through training they must be able to assess the legal, functional, and communicative potential of the digital tools to put together a toolbox according to the framework conditions and the expected skills of the learners.

In the present case, the news provider Vox Media has a professional graphics department, so that proportions, distances, color and shaping, and color saturation and temperature of the images will be strategically calculated and implemented in line with the company's corporate identity guidelines (Figure 2). In addition, the communication-strategic use of Instagram, which can also be a part of practical media competence, have been considered. Vox is not limited to the presentation of its content on the main website but also present on various online media channels. Vox operates these in accordance with the respective requirements of these social media platforms. As Instagram is one of the most important social media platforms for younger people, the media company is moving toward its target group and offers content in accordance with the communication styles common on Instagram. Certainly, the reason behind it is to reach potential customers or readers and to advertise the central homepage.

Figure 2. Vox (2022) (https://www.instagram.com/p/CXUf4iOu28U/, accessed March 20, 2022).

Style Practice of Choosing Semiotic and Narrative Competence

Multimodal competence (cf. Stöckl, 2010) is shown in the ability to use the described semiotic style practices in an understandable, genre-, addressee-, or cooperation-oriented manner. The aim is to show that the communicators are able to produce multimodal, coherent texts in accordance with the existing media, cultural, and situational contexts. It is the semiotic competence that is able to choose, form, and compose semiotic resources to achieve specific communicative goals.

Focused on the choosing, the objects, contents (denotations), concepts, and notions of the multimodal artifact are highlighted, as well as the selected semiotic modes with which they were expressed. In pictorial communication, it is, above all, important to determine the main motif to be able to classify its stylistic construction of identity and its function as a protagonist for the further storyline. Possible symbolizations or metaphors of this main motif can also be mentioned, which are given certain rhetorical functions through reference to the existing contexts. The selection (the first style practice) of the objects, motifs, and concepts to be communicated can be understood as the first semiotic competence. It is the cultural ability, rhetorically, that associate signifiers with meaningful discourses. It is also the semiotic competence that is able to do this with different modes. In this way, communicators can differentiate between the showing function of the image and the narrative, explanatory, classifying function of language, depending on the cultural contexts. However, if the image appears in sequences as in comics or film, this modality can also represent a narrative progression.

The first slide of the example discussed here makes this particularly clear as it exemplifies the different semiotic functions of language and image. Visually, it shows two round phenomena that can be identified as planets in different conditions. Linguistically, the planets are described as different possible stages of the planet Venus. Thus, the linguistic signs name these visual phenomena and locate them in the space–time continuum. In addition, an outcry is articulated linguistically. The indication of authorship is also shown by the logo of the news provider. The slide also includes the verbal question: “What the hell happened?” after it was stated at the top that Venus was once a paradise that turned into a hellish landscape. It has been proven that the semanticization of images makes the audience consider them first. Their simultaneous and figurative appearance makes them more dominant than language, and so Venus as the main pictorial motif can also be determined as the most important theme of the slide. The linguistic parts of the slide (see the style practices below) can also be semantically linked to the subject of the picture, thereby further qualifying the identity of Venus. This makes Venus the action-driving protagonist of the entire slidecast.

Style Practice of Forming as Semiotic Competence

Focused on the style practice of forming, questions of analysis arise regarding the communicative design of the visual and verbal phenomena, sound, typography, and graphics. This includes all meaningful elements of the media products and how these create the identity of the protagonist and organize the relationship between the protagonist and the recipient. In a personality representation as done by influencers, such elements are, for example, outfits, gestures, facial expressions, status, attitude, poses, and special rhetorical skills.

As described, the considered slides treat the planet Venus as the protagonist, but in the accompanying text, scientists drive the plot by exploring the possible causes of climate change on Venus. However, I limit myself here to the production and analysis of the slides. The first thing that catches the eye in the first slide is the colored round areas in the center of the slides (i.e., the planets). Second, the question is highlighted: “What the hell happened?” It is written in bold, larger than the other parts of the text, and highlighted in yellow. The captions are smaller, white, and in bold typography. The text parts at the top are also in white and appear slightly larger. While all of the written parts are plain and sans serif, the logo of the news provider Vox appears in its own artistically designed, bold typo with serifs and italics. This marks Vox as a dynamic breaking-news producer in terms of the newspaper and the suggestion of movement created by the use of italics.

The two planets depicted have a high color saturation. The image on the left is also characterized by the strong warm/cold contrast through the symbolic blue of the seas and the brown, suggesting continents. This is reminiscent of pictorial representations of planet Earth, even if the land formation differs from terrestrial continents. The white flakes, which look similar to clouds, also support the impression of being similar to Earth. The planetary image on the right, titled “Venus as it is today,” is remarkable for its saturated yellow–brown gradients, as well as furrows and crater structures on the surface. These also result in strong light/dark contrasts and an impression of chaos and eruption. The brown also signifies a lack of life, especially in contrast to the Earth. In addition to these identity-forming designs of the main motif, its arrangement, which produces the relationship between motif and recipient, must be considered. This too needs semiotic competence, because communicators have to calculate the effects of typography, camera actions, perspectives, and image sections. In this case, the recipient is placed face-to-face with the two images. The perspective realized here simulates a view at the earth directly from space. In this way, the viewer also becomes a planet (maybe Earth) looking at (the neighboring planet) Venus. However, this perspective does not appear unusual here, but rather follows viewing habits known from astronomy lessons and textbooks. The question highlighted in yellow is visually more striking. Marked in terms of content and typography, it is a cry of despair aimed directly at the viewer. This is addressed emotionally with strong words like paradise, hell, and hellscape. The recipient is involved in the current climate debate about Earth and is confronted with the supposedly similar fate of Venus with a deadly end.

The narrative design of the communicative artifacts described here (the style practice of forming) is based on the communicative experiences and genre knowledge of the communicator. Genre knowledge, in particular, includes communicative patterns for the organization of social relationships. The slide adopts design patterns from textbooks to be classified in the educational context. At the same time, the slide departs from the neutral educational genre and presents a loud cry of despair about not knowing why the climate on Venus has changed so much. This genre contrast in one communicative product has a specific effect on the recipient. Visually, it informs the recipients about the current and possible former state of Venus and verbally, it gives advice. With this genre contradiction, the media product makes you read the other slides to be able to resolve this contradiction. This already leads to narrative competence, which is mentioned in the next section.

The Style Practice of Composing as Multimodal and Narrative Competence

The analysis of composing examines the communicative practice of arranging the individual communicative phenomena and the resulting transcription processes. Here, the focus is on how the positioning of the communicative entities makes them mutually readable and which protagonist's actions or storylines are interpreted from this. In this way, the semiotic competence of signification is combined with the narrative competence of understanding to produce dramaturgically designed multimodal semiosis; that is, the ability to construct coherent multimodal text meanings from the individual signs by transcribing them. As already shown, the transcriptions are structured by multimodal framings. These are realized visually through the production of form, color, and content contrasts. These contrasts create saliences that emphasize certain details while others fade into the background. Narrative competence makes it possible to recognize these focuses in reception and to arrange them dramatically in production.

In addition, there is the ability to understand how the identity of a protagonist is related to their social, cultural, and local (>situational) contexts, which problems or options can be expected from this, and how these can be logically changed by the actions of the protagonist. This is also illustrated with the example.

Slide one presents all communicative entities on a black surface, which combines the individual phenomena into a multimodal text. At the same time, the color black symbolizes the color of space. In addition, this dark background creates maximum contrast and thus highlights the individual artifacts. After Venus has been recognized as the protagonist of the story, the recipient collects further information about the identity (status) and the contexts. This process of understanding is structured by the simultaneous presentation of the planets as a before-and-after dramaturgy. The two views are semantically supported through the mention of the change which turned the planet from paradise to hell. This information becomes a cliff-hanger because of the emotional question about the reasons. This cliff-hanger is also emotionally charged because a possible parallel to climate change on Earth can be drawn. This parallelism is intensified in the second slide by graphically combining Earth and Venus into one imaginary planet. The similarities are also explicitly emphasized in the explanatory text, so that the audience understands that a similar catastrophic scenario is also possible for Earth. In the following slides, however, this parallelism is not continued; instead, the individual reasons for climate change on Venus are discussed. Finally, however, the parallelism is again constructed with the depiction of the Earth and a warning to earthlings to beware of irreparable damage to the climate.

Narrative competence enables multimodal coherence not only in the different modes presented simultaneously, but also in their linear sequence. The given and the new are compared intuitively and the change is interpreted as a narrative progression. Again, transcribing is done by the communicators to reconstruct a coherent overall meaning of the ongoing plot of the text. Above all, as in comics, coherences are created between the panels so that the flow of action between the scenes is not interrupted. Narrative competence is thus the ability to frame different modalities according to current communication situations and to bring them into a coherent unit of meaning. Furthermore, it includes the possibility of recognizing the associated problems and possible solution developments as action steps according to a narrative plan that brings a certain protagonist with certain characteristics into a certain action situation. As a media producer, it is important to plan this plot and the message before digital production and to calculate the appropriate sign modalities in terms of communication strategy.

Conclusion

The aim of this contribution is to explain multimodal coherence-making as a transcribing practice and how this can be used to train multimodal, narrative, and media competences. In multimodal arrangements, language makes images readable in specific ways and images make language understandable in different ways. This results in an abductive understanding process that can be made use of in teaching and learning contexts.

To this end, the institutionalized modes of action of the digital-media dispositif were first described. The basic idea was that media infrastructures and semiotic modalities bring specific materialities with them, which cause certain affordances. Thus, how the semiotic modality can be used for communication (e.g., written or spoken language and static or moving images) depends on the media affordances, and the form of communication depends on the affordances of the semiotic modes used in each case: A picture can show things in great detail, but a text can classify things in the time–space continuum. Media-materiality in the form of a digital video platform can make a video perceptible, whereas the affordances of a newspaper do not allow this. These material possibilities and restrictions are combined in the institutionalized media dispositif with social rules and conventions that dictate the practices of what can be said and shown in certain situational and cultural contexts.

The knowledge of the affordances of digital media and the institutional conditions of the digital media dispositif as well as the semiotic affordances of the different modes of signs enable teachers and learners to use digital media maturely and strategically. The knowledge of multimodal and narrative coherence construction enables teachers and learners to use digital media for creative knowledge communication in the form of digital storytelling. The didactic considerations presented here should make this clear. This is based on the social semiotic approach of style as suggested by Meier (2014). In this approach, style is understood as the practice of selecting, forming, and composing semiotic resources. These stylistic practices realize a subjective appropriation of discursive, genre, and habitual patterns, which are carried out within the semiotic and technological dispositions of the situationally used media infrastructures. In this sense, this contribution made clear that digital storytelling is multimodal style practice with digital tools. Multimodal storytelling in educational contexts means that teachers and learners are prompted to bring the communicative functions of text, image, video, and audio into narrative coherence.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Bateman, J., Wildfeuer, J., and Hiippala, T. (2017). Multimodality: Foundations, Research and Analysis – A Problem-Oriented Introduction. Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter.

Bourdieu, P. (1986). “The forms of capital,” in Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, ed J. G. Richardson (New York, NY: Greenwood Press), 241–258.

Council of Europe (2022). Digital Citizenship Education Handbook. Available online at: https://rm.coe.int/prems-003222-gbr-2511-handbook-for-schools-16x24-2022-web-bat-1-/1680a67cab

European Union (2017). DigCompEdu. Available online at: https://www.coe.int/en/web/digital-citizenship-education/-/2022-edition-of-the-digital-citizenship-education-handbook (accessed March 28, 2022).

Foucault, M. (1980). “The confession of the flesh” interview 1977,” in Power/Knowledge Selected Interviews and Other Writings, ed C. Gordon, 194–228.

Goffman, E. (1956). The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. Edinburgh: University of Edinburgh Social Science Research Centre.

Holly, W. (2015). “Bildinszenierungen in Talkshows. Medienlinguistische Anmerkungen zu einer Form von ‘Bild-Sprach-Transkription,'” in Polit-Talkshow. Interdisziplinäre Perspektiven auf ein multimodales Format, eds H. Girnth and S. Michel (Stuttgart: ibidem), 123–144.

Jäger, L. (2002). “Transkriptivität. Zur medialen Logik der kulturellen Semantik,” in Transkribieren, eds L. Jäger and G. Stanitzek (München: Fink), 19–41.

Kress, G. (2010). Multimodality. A Social Semiotic Approach to Contemporary Communication. London: Routledge.

Kress, G., and van Leeuwen, T (2021). Reading Images. The Grammar of Visual Design. London: Routledge.

Meier, S. (2014). Visuelle Stile. Zur Sozialsemiotik visueller Medienkultur und konvergenter Design-Praxis. Bielefeld: transcript.

Meier, S. (2021). “‘Multimodalität in medialen Dispositiven': Konzeptuelle Anregungen zum institutionellen Zeichenhandeln in medienkulturellen und medientechnologischen Infrastrukturen,” in Medien, Materialität und Zeichen. Neue Impulse zu einer semiotischen Medientheorie, eds J. Brückner, S. Meier, M. Dang-Anh, D. Reelstab (Themenheft), 2021, Band 41, Heft 1-2/2019.

O'Halloran, K. L., and Victor, L. F. (2014). “Systematic functional multimodal discourse analysis,” in Interactions, Images, and Texts: A Reader in Multimodality, eds S. Sigrid Norris and C. D. Maier (Boston/Berlin: de Gruyter), 137–55.

Redecker, C. (2017). “European Framework for the Digital Competence of Educators: DigCompEdu,” in ed Y. Punie (Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union) Available online at: https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/bitstream/JRC107466/pdf_digcomedu_a4_final.pdf

Rubio-Hurtado, M.-J., Fuertes-Alpiste, M., Martínez-Olmo, F., and Quintana, J. (2022). Youths' posting practices on social media for digital storytelling. J. New Approaches Educ. Res. 11, 97–113. doi: 10.7821/naer.2022.1.729

Stöckl, H. (2010). “Sprache-Bild-Texte lesen. Bausteine zur Methodik einer Grundkompetenz,” in Bildlinguistik, eds H. Diekmannshenke, M. Klemm, and H. Stöckl (Berlin: Erich-Schmidt), 43–70.

Stöckl, H. (2019). “Linguistic multimodality – multimodal linguistics. A state-of-the-art sketch,” in Multimodality. Towards a New Discipline, eds J. Wildfeuer, J. Jana Pflaeging, J. John Bateman, S. Ognyan, C. I. Tseng (Berlin/Boston: de Gruyter), 41–68.

Swales, J. M. (1990). Genre Analysis: English in Academic and Research Settings. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Keywords: digital storytelling, media dispositif, digital, multimodal and narrative competences, (visual) identity, style practices, medial and semiotic affordances, cultural and situational context

Citation: Meier S (2022) Digital Storytelling: A Didactic Approach to Multimodal Coherence. Front. Commun. 7:906268. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2022.906268

Received: 28 March 2022; Accepted: 20 June 2022;

Published: 19 July 2022.

Edited by:

Hartmut Stöckl, University of Salzburg, AustriaReviewed by:

Elise Seip Tønnessen, University of Agder, NorwayArlene Archer, University of Cape Town, South Africa

Copyright © 2022 Meier. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Stefan Meier, c3QubWVpZXJAdW5pLWtvYmxlbnouZGU=

Stefan Meier

Stefan Meier