94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

BRIEF RESEARCH REPORT article

Front. Commun., 29 April 2022

Sec. Culture and Communication

Volume 7 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2022.900257

This article is part of the Research TopicThe Nature of Human Experience with Language and EducationView all 18 articles

Body dissatisfaction has become increasingly common among women and young adults and has only become worse in the digital age, where people have increased access to social media and are in constant competition and comparisons with their “friends” on their different social media platforms. While several studies have looked at the relationship between social media and body dissatisfaction, there is an obvious dearth of empirical studies on the mediating role of social anxiety- a gap this study hoped to address. Using a cross-sectional research design, this study examined the mediating role of social anxiety on the relationship between social media usage and body dissatisfaction. The sample consisted of 432 students from Kampala International University and Victoria University in Uganda. The findings show a significant positive relationship between social media usage and body dissatisfaction. The findings prove that heavy users of social media are significantly more likely to suffer from body dissatisfaction. In a similar vein, the findings show that there is a significant positive relationship between social media usage and social anxiety. This suggests that people that frequently make use of social media have a much higher chance of suffering from social anxiety, that is the inability or difficulty to engage in social interactions, than people that rarely or moderately make use of social media. Finally, findings show that social anxiety mediates the relationship between social media usage and body dissatisfaction. It indicates that people with high levels of social anxiety are more likely to suffer from body dissatisfaction as a direct result of heavy social media usage. These findings imply that although heavy users of social media tend to have a more negative perception of their body, if these same users can properly engage in social interactions, then this might mitigate the negative effects of social media usage (in terms of body dissatisfaction).

Body dissatisfaction usually arises as a result of negative thoughts or feelings about one's body image. Perception of one's body image is, therefore, a prerequisite to feelings of body dissatisfaction. Body image is often described as a person's perception, emotions, and thoughts about their body (Jiotsa et al., 2021). Body images are usually a reflection of their mirror image, combined with social expectations of what a good or bad body is. This conception of body image is created by using body ideals as promoted by mainstream media, society, peers, and family (Greene et al., 2017).

Media has been playing a role in exposing people to what they consider the ideal body right from a young age (Blowers et al., 2003). Children are told that a certain actress has the best body, and a certain athlete has the perfect physique and so they grow up thinking anything short of that is not sought after. So, depending on what that image is at a particular time, people are somewhat conditioned by the mass media and popular culture to seek such an image which in certain cases may result in body dissatisfaction. So, in a culture or a period where thinness is seen as ideal, overweight people will increasingly feel discontented with their bodies and seek ways to “improve” which may lead to an increase in eating disorders and anorexia (Stormer and Thompson, 1996). Moreover, body dissatisfaction is characterized by a difference in perception between one's real body and their ideal body.

As mentioned above and according to numerous studies, body dissatisfaction is a major factor in the development of eating disorders (Attie and Brooks-Gunn, 1989; Killen et al., 1996). People drastically reduce their food intake which can lead to anorexia or even dramatically increase their food consumption which can, in turn, lead to obesity. Social comparison is another major factor that greatly influences body image satisfaction or dissatisfaction. Social comparison is often combined with the internalization of the ideal body image and affects how individuals perceive their body image. Studies have shown that individuals who compare their physical attributes to people they think are more beautiful than them are significantly more likely to be dissatisfied with their body image and to develop eating disorders (Dittmar and Howard, 2004; Corning et al., 2006; McKee et al., 2013; Ferguson et al., 2014). Social media has by its very definition made it easier and increasingly more likely for users to compare themselves to others in terms of social acceptance yardsticks/standards, like beauty, success, ability, etc. As earlier stated, these comparisons combined with the reach and ubiquity of social media tend to negatively impact body dissatisfaction among social media users.

Anxiety has also been linked to higher social media usage and emotional investment in body image (Jenkins-Guarnieri et al., 2013). However, as explained in the next section, not many studies have considered the mediating role of anxiety on the relationship between social media usage and body dissatisfaction, an aim that this study aims to achieve.

This study, therefore, seeks to find out how social anxiety influences the relationship between social media usage and body dissatisfaction among university students in Uganda. The assumption is that social media usage plays a role in the development of body dissatisfaction. The researchers posit that university-aged individuals, especially women, will be most likely to be negatively impacted by social media usage. However, the researchers want to test whether social anxiety (or lack of) can mediate the relationship between social media usage and body dissatisfaction.

This study was premised on two theories, namely, social identity theory and social comparison theory.

Social media makes it possible for its users to explore, control, and manage their online identities which may influence their sense of self-worth (Taylor-Jackson and Moustafa, 2021). Social media users more often than not project the best versions of themselves, because, most times, they have control over what other people can see and know about them. They decide what needs to be shared and thereby knowingly or unknowingly control how people perceive them. The perception of themselves they create online might not be attainable in the real world. Social media users have the means to edit their pictures to appear slimmer, fairer, or even in a completely different location. Once the users are fully immersed in their self-constructed social media world, their “real-life identity” may get distorted (Taylor-Jackson and Moustafa, 2021). According to Aiken (2016), the act of portraying one's “aspirational self” online can have a deleterious effect on their future self-perception and mental wellbeing if care is not taken.

Social identity theory describes self-concept and the feeling of self-worth is derived from the perceived membership of a certain group or class within a given society (Turner and Oakes, 1986). Because social groups/online communities are limitless, it might be mentally and psychologically exhausting for individuals to build networks and maintain a particular image across those various groups. Turner and Oakes' (1986) study is particularly relevant to this study because it shows how social groups one belongs to or aspires to belong to can impact their mental wellbeing and lead to a deluge of mental issues including, but not limited, to body dissatisfaction.

As one seeks to define their online and real-life identity, they often compare themselves to people they think are better. So, for social media users, there is a tendency to compare themselves to models, actors, and influencers while using them as the standard to gauge their progress. This action is often referred to as social comparison. Social comparison theory by Festinger (1954) posited that people evaluate their self-worth, value, and abilities by comparing themselves to other people. There are two forms of comparisons according to Festinger, namely; upward comparison and downward comparison.

Upward comparison is a situation where individuals compare themselves to people they think are doing better than them in terms of what their concern is at that moment. So, for someone concerned with success, they might compare themselves with more successful people, depending on how they define success. People concerned with body image will compare themselves with people they think, or society says, are prettier. Upward comparison has been linked with a decline in levels of self-esteem. Vogel et al. (2014) explained that social media makes comparison a lot easier. The study by Vogel et al. further explained that this relationship was mediated by increased exposure to profiles with positive content, like healthy lifestyle regiments, motivational quotes, and so on. The implication is that the more people make use of social media, the lower their self-esteem is unless they are also highly exposed to positive content on a platform. Similarly, studies by Feinstein et al. (2013), showed that people who make a lot of comparisons on social media have a significantly higher number of depressive symptoms than those who do not compare themselves to others. Downward comparison on the other hand refers to when individuals compare themselves with people they perceive to be less fortunate. In a lot of cases, people do this to improve their sense of self-worth and self-enhancement.

Downward or upward comparison is made easier when one uses social media because social media is a window through which people experience new worlds and share experiences that would have otherwise remained inaccessible. So, in the quest to find an identity or a social group to belong to, people seek out those that are similar or who they aspire to be and “follow” them. By following them, and getting drawn into their reality, the chances of becoming behaviorally or psychologically influenced become increasingly more likely.

These theories are relevant to this study because they explain the relationship between social media usage, group identity, and perception. Furthermore, the theories explain why this relationship exists. By understanding the relationship between these two variables, it will be easier to understand how anxiety mediates the relationship.

Social media refers to different internet-based platforms that allow users to connect and interact with one another in different formats- pictures, texts, videos, and many others (Jarrar et al., 2020). According to Statista (2021), 3.78 billion people worldwide are social media users, representing over 50% of the world population. Therefore, understanding the impact of social media usage on body image is important because people spend 2 h and 25 min on social media on average every single day (Chaffey, 2021). Kim (2017) explained that understanding the impact of social media on the wellbeing of individuals is important considering the increasing levels of mental health issues. Addiction to social media is well-documented and has long been considered a major issue in academia (Kim, 2017; Coyne et al., 2020; Karim et al., 2020).

Social media, according to Keles et al. (2020) can be considered double-edged, meaning that it has its benefits and its drawbacks. The benefits of social media include the creation of platforms for people to express themselves in a way that might have otherwise been difficult to attain. Social media also allows people to receive social support at a level that is almost impossible offline (Deters and Mehl, 2013; Lilley et al., 2014; Lenhart et al., 2015). On the flip side, various studies have also shown a significant positive relationship between social media usage and psychological problems. For instance, a study reviewing 11 previous research papers studying social media usage and depression in children and young adults showed a statistically significant relationship between the two variables (McCrae et al., 2017). A similar study analyzing 23 different pieces of research on Facebook usage and psychological issues among young adults and adolescents showed a correlation between the variables (Marino et al., 2018), an indication that the more young adults and adolescents make use of social media, the higher the likelihood that they will develop psychological problems.

Contrary to the above, one major factor influencing the relationship between mental health and social media usage is social support. Social media allows people to strengthen their relationships with existing friends and cultivate new relationships online, which in turn can help reduce the feeling of isolation and loneliness, thereby indirectly improving the mental wellbeing of users (O'Keeffe et al., 2011). Various studies have shown that people with low social support tend to have more mental health issues than people with a strong social support system or network (Maulik et al., 2011). While it does appear that social support (which social media makes easy and convenient to get) is very important to the mental well-being of people, Teo et al. (2013) indicated in their studies that the quality of this support is even more important than the quantity. People might have a lot of friends on social media platforms and still feel alone and rejected, while others with a low friend count might get all the support they need online. This is a reflection on the types of interactions and relationships one has on social media and can be the major factor in determining how one sees themselves and their place in society.

Body image issues have become a front-burner issue in the media, academia, and psychology. Studies have shown that young adults, and adolescents, especially females, suffer a lot from body dissatisfaction. In a study by FHEHealth (2020), on body image and social media usage, 1,000 men and woman were surveyed, and the findings showed, among other things, that 87% of women compared their bodies to other people on social media, as compared to 65% of men who did the same. Based on the same study, 50% of women thought they look worse than those they compared with on social media, while about 37% of men thought the same. In realization of the impact of social comparison on the mental health of people, Norway, in 2021, passed the “Retouched photo law” as an amendment to the country's Marketing Control Act. The Norwegian Ministry of Children and Families explained that the law was created to “raise awareness among people that the perfect bodies in advertisements do not show people as they appear in real life” (The Washington Post, 2021).

Furthermore, a study by Ferguson et al. (2014) who went a bit further by comparing the effect of traditional media (TV), peer relations, and social media on body dissatisfaction found out that peer competition and social media usage both predicted, to varying degrees, negative body image outcomes. Although their findings clearly show that peer pressure had more of a negative effect on body image perception and social media has more of an effect on peer competition, the findings by Ferguson et al. do not show a direct relationship between social media usage and body dissatisfaction, it does prove that social media increases peer competition which in turn can lead to feelings of body dissatisfaction.

Based on the foregoing, the following hypothesis was proposed:

H1: there is a significant positive relationship between social media usage and body dissatisfaction among university students in Uganda.

Preoccupation with social media by university students can manifest in the form of spending too much time on social media, having a strong motivation and inclination to make use of social media, and can lead to adverse effects on their social, professional, personal life, and mental wellbeing (Andreassen and Pallesen, 2014). The recent Covid-19 related lockdowns all over the world have forced people to seek solace and connection online and have led to an increasing reliance on social media for the littlest social connection. The pandemic and its resultant lockdowns have prolonged the time spent on social media generally and have led to an emergence of problematic social media usage and therefore might have negatively impacted the mental health of university students (Jiang, 2021).

Studies by Lepp et al. (2014) showed that prolonged and problematic use of social media can lead to increased levels of anxiety. A study by Thorisdottir et al. (2019) detailed social media use and anxiety levels among Icelandic youths and found that passive use of social media led to greater anxiety symptoms among both males and females. Their study also found that excessive use of social media, either passive or active, among students, invariably led to problematic use of social media which in turn could result in higher levels of anxiety. In a similar vein, studies by Hussain and Griffiths (2018) and Wong et al. (2020) found a significant relationship between problematic social media usage and anxiety.

Furthermore, studies by Zsido et al. (2020) on social fears and social media usage, found that individuals with social anxiety issues and low self-esteem tend to prefer computer-mediated communication instead of face-to-face communication which in turn can lead to excessive or pathological use of social media as a means to compensate for their lack of social interactions in real life.

A more recent study by Zsido et al. (2021) on the role of maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies and social anxiety in problematic smartphone and social media use, reaffirms the relationship between social anxiety and social media usage. They explained that “individuals who are highly socially anxious prefer computer-mediated communication over face-to-face communication possibly due to the control and social liberation that it provides” (p. 1). Their findings showed a direct significant relationship between social anxiety and pathological social media usage. Based on the foregoing, it is clear that the negative impacts of social media usage usually manifest only when there is excessive usage of the platforms. Individuals that reported medium to low usage frequency do not usually develop these issues.

Based on this, the researchers propose the following hypothesis:

H2: There is a significant positive relationship between social media usage and anxiety levels among university students.

Social anxiety is usually a result of a personal evaluation of one's social situation, be it real or imagined (Schlenker and Leary, 1982). Previous studies showed that social comparison is linked to feelings of social anxiety (Jiang and Ngien, 2020). Social comparison, as earlier explained, consists of people's natural inclination to evaluate and compare their situation, skills, identity, and even performance with others (Festinger, 1954). Both upward and downward comparisons have been shown to often harm the mental wellbeing of individuals (Gilbert, 2000; Stein and Sareen, 2015). Antony et al. (2005) explained this by stating that people who compare themselves to other people (either upward or downward comparison) are significantly more likely to care about how other people perceive them which can affect their mental wellbeing (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Weeks et al. (2009) in their study on social comparison and social anxiety found out that social comparison was positively related to social anxiety, as well as increased fear of public scrutiny. In a similar study carried out by Mitchell and Schmidt (2014), the findings suggested that there is indeed a causal relationship between social comparison and social interaction anxiety. Also, Gregory and Peters (2017) concluded that social comparison is a major predictor of social anxiety disorder.

From the foregoing, it is clear that social media encourages social comparison, which in turn can have a negative impact on the anxiety levels of social media users. While these relationships appear to be well-established, very little is known about the mediating role of social anxiety on the relationship between social media usage and body dissatisfaction. This study is premised on the assumption that people with high levels of social anxiety will be more likely to suffer from body dissatisfaction irrespective of their social media usage. Based on the foregoing, the following hypothesis was developed:

H3: There is a mediating effect of social anxiety on the relationship between social media usage and body dissatisfaction.

The study made use of a cross-sectional research design. The cross-sectional study design is a type of observational design, and it investigates the outcome and exposures of the study participants at the same time. Questionnaires were distributed to study participants at the same time and the responses to the questionnaires were analyzed and interpreted. Participants were informed about the study's aim and were assured of confidentiality before they were asked to fill out the questionnaires.

This study population consisted of students of Kampala International University and Victoria University in Uganda. This demographic was selected because the study focuses primarily on adolescents and young adults. This demography of respondents is predominantly university students since they fall between the ages of 18 and 25 mostly. The institutions were selected because they are situated in Kampala, which is the major city in Uganda and has good internet connectivity (a prerequisite for using social media). By selecting university students in Kampala, the researchers were fairly confident that the respondents will be aware of and make use of social media. Also, the participants are expected to be literate enough to understand the study and answer the questions.

The age range (18–25 years old) was selected because current literature suggests that they are more likely to make use of social media and also be concerned about body image than any other age category (Duggan, 2015). The second inclusion criterion was that all participants in this study must be aware of and make use of at least 2 different social media platforms. In total, 432 students participated in this study (52% of which are females while 48% are male). The average age of the respondents was 21.3 years.

The researchers sent out a notice to students in both universities, clearly stating the criteria for selection to participate in the study. Based on this communication, over 557 students from both institutions indicated interest. After this stage of the selection process, the researchers removed students that did not meet the criteria, for instance, anybody above the age of 25 was disqualified from participating. At the end of this exercise, 432 students were left and allowed to participate in this study. The selected students were asked to report to the main auditorium at Victoria University, and the main hall of Kampala International University on different days (1 day apart for students from VU and those from KIU) where the purpose of the study was once again explained to them and their consent was collected.

See Table 1 below for detailed demographic data.

To collect pertinent data, the researchers opted to make use of questionnaires that combine the following scales: Body Dissatisfaction Subscale from EDI-III (Garner, 2004), The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), The Multidimensional Scale of Facebook Use (MSFU) by Frison and Eggermont (2015), and The Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS) (1987) (Leonard and Blane, 1988).

Section one of the questionnaire collected demographic data like age, course of study, income level, gender, and marital status. Section one also included the inclusion criteria question of social media usage. Respondents were required to confirm whether or not they make use of social media and the types of social media platforms they use frequently.

Section two of the questionnaire looked at social media usage. In this section, respondents were required to answer the questions as required in The Multidimensional Scale of Facebook Use (MSFU). Section three of the questionnaire included questions related to body dissatisfaction. This section of the questionnaire adopted the Body Dissatisfaction Subscale from EDI-III which was specifically designed to measure body dissatisfaction.

Finally, Section four of the questionnaire required the participants to answer questions related to anxiety. This section sought to find out whether the respondents suffer from anxiety or not. The Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS) was adopted for use in this section. The LSAS is a 24-item interviewer-rated scale that measures fear and avoidance (each on four-point scale) reported in social interaction and performance situations (Liebowitz, 1987). The LSAS has demonstrated validity and reliability as a self-report measure. Separate indices can be calculated for fear and avoidance factors for both social interaction and performance. Reliability for the fear and avoidance subscales has ranged from 0.81 to 0.92 and from 0.83 to 0.92, respectively (Orsillo, 2001).

While distributing the questionnaires, the researchers made use of stratified random sampling, to separate students in the Social Sciences and Arts from those in the STEM field. This way every program category is represented in the study. The breakdown of the distribution is as follows.

The fundamental purpose of using statistical analysis to analyze data “is to assist in establishing the plausibility of the theoretical model and to estimate the degree to which the various explanatory variables seem to be influencing the dependent variable” (Coorley, 1978, p. 13). In the same vein, the main objective of this study was to empirically examine the mediating effect of social anxiety on the relationship between social media usage and body dissatisfaction among university students in Uganda. Accordingly, the raw data must be subjected to certain preliminary tests (Hair et al., 2010). JAMOVI 1.8.4.0 software was used for data coding, tests for missing data, outliers, internal consistency, and normality. The current study made use of the “MEDMOD” library in JAMOVI to test the hypotheses for mediation.

The internal consistency was good (Social media use: α = 0.88, 95% CI[0.86, 0.89]; ω = 0.89, 95% CI[0.85, 0.90], n items = 13, Social anxiety: α = 0.87, 95% CI[0.85, 0.88]; ω = 0.86, 95% CI[0.84, 0.89], n items = 24, and body dissatisfaction.: α = 0.86; 95% CI[0.84, 0.87]; ω = 0.88, 95% CI[0.85, 0.91], n items = 10).

Scatterplot of standardized residuals showed that the data met the assumptions of homoscedasticity, and linearity, and the residuals were approximately normally distributed and contained no outliers (Std. Residual Min = −2.13, Std. Residual Max = 2.91). Multicollinearity was not a problem (Social media use, Tolerance = 0.92, VIF = 1.06; Social anxiety, Tolerance = 0.94, VIF = 1.03) and the assumption of independent errors (Durbin-Watson value = 2.1) was equally met.

Hypothesis: There is a mediating effect of social anxiety in the relationship between social media usage and body dissatisfaction.

To achieve the main objective of this study, which was to examine the mediating effect of social anxiety on the relationship between social media usage and body satisfaction, mediation was tested using the MEDMOD library in JAMOVI and the results indicated a significant positive relationship between social media use and body image dissatisfaction (r = 0.420, p < 0.001), suggesting that heavy social media users tend to feel more dissatisfied with their body image. Also, a significant positive relationship between social media use and social anxiety (r = 0.316, p < 0.001) was found, suggesting that the more anxious a person feels, the more likely the person spends more time or uses social media and vice versa.

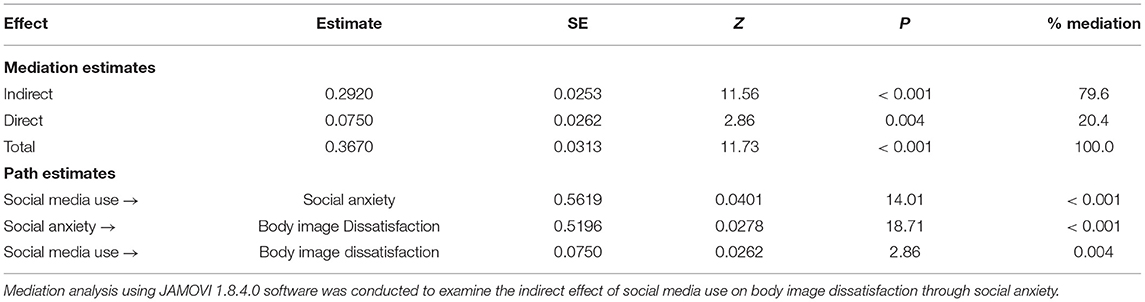

The results of the mediation show that social media use is positively correlated to social anxiety β = 0.562, SE = 0.040, z = 14.01, p < 0.001, and body image dissatisfaction is positively related to social anxiety, β = 0.520, SE = 0.028, z = 18.71, p < 0.001. Moreover, social media use has a positive relationship with body image dissatisfaction β = 0.075, SE = 0.026, z = 2.86, p < 0.001.

The effect of social media use on levels of body image dissatisfaction is partially mediated via the level of social anxiety. As Table 2 illustrates, the regression coefficient between social media use and levels of body image dissatisfaction and the regression coefficient between social anxiety and levels of body image dissatisfaction are significant. The indirect effect was 0.292., and this indirect effect is statistically different from zero, as shown by a 95% bootstrap confidence interval ranging from 0.2341 to 0.3502 which is above zero. The indirect effect is statistically significant (p < 0.001).

Table 2. Mediation estimates of the mediating effect of social anxiety on the relationship between social media usage and body dissatisfaction.

The indirect effect of 0.292 means that two participants who differ by one unit in their reported social media use are estimated to differ by 0.292 units in their reported body image dissatisfaction. As a result, heavy users of social media were more likely to experience social anxiety (due to the positive value obtained), which in turn translates into higher levels of body image dissatisfaction (due to the positive value obtained).

The result of hypothesis 1 testing, showed a significant positive relationship between social media use and body image dissatisfaction. This supports the findings by FHEHealth (2020) where an extensive study was carried out targeting over 1,000 participants. The findings showed that over 85% of women and 65% of men who used social media regularly compared their bodies to other people on social media. Of this number, 50% of the women ended up feeling that they look worse than people they competed with on social media. Their findings showed a clear relationship between the frequency of social media usage and body dissatisfaction. Other studies have addressed the issue of body dissatisfaction as a psychological issue and have found that the more time spent on social media, the higher the likelihood of the user to develop an unrealistic definition of beauty, which in turn can lead to higher levels of body dissatisfaction (Maulik et al., 2011; O'Keeffe et al., 2011; Teo et al., 2013). By proving hypothesis one correct, this finding supports those of Ferguson et al. (2014) who also found out that social media usage increases social comparison which in turn can lead to increased levels of body dissatisfaction among pathological users of social media.

The results of hypothesis 2 testing showed a significant positive relationship between social media use and anxiety. The implication of this is that the more people make use of social media, the higher the likelihood of developing anxiety issues is. This finding supports those of Lepp et al. (2014) who found out that prolonged and problematic use of social media can lead to an increase in levels of anxiety. Similarly, findings by Thorisdottir et al. (2019) which showed that problematic use of social media can lead to higher levels of anxiety, are supported. Although studies by Thorisdottir et al. (2019) differentiated social media usage into passive and active usage, their findings showed that irrespective of the type of usage, the more time spent on social media, the higher the tendency for users to develop anxiety problems. This finding lends credence to those by Zsido et al. (2020, 2021) who found a significant relationship between social anxiety and social media usage which implies that the more people make use of social media, the higher the tendency that they will develop high levels of body dissatisfaction.

Hypothesis 3 was tested using mediation analysis and the result showed that social media use is positively correlated to social anxiety. It also showed a positive relationship with body image dissatisfaction. The findings further showed that the effect of social media use on levels of body image dissatisfaction is partially mediated via the level of social anxiety. The findings showed that heavy users of social media were more likely to experience social anxiety which in turn translates into higher levels of body image dissatisfaction.

Based on this finding, it can be concluded that users that frequently make use of social media, referred to in this study as heavy users, are significantly more likely to develop social anxiety which in turn will invariably lead to high levels of body dissatisfaction. The implication is that users that suffer from social anxiety are more likely to feel the negative effect of heavy social media usage, especially in the form of body dissatisfaction. The findings of this study support those by Gregory and Peters (2017) who concluded that social comparison on social media is a major predictor of social anxiety disorder. However, it is clear from the literature above that very little is known about the mediating role of social anxiety on the relationship between social media usage and body dissatisfaction. The findings of this study are unique in the sense that the study charts a new course in understanding the relationship between social media usage and body dissatisfaction by introducing a hardly discussed variable into the mix, namely, social anxiety.

Furthermore, the findings of this study partially support the social identity theory which posits that people derive a sense of self-worth by the inclusion or acceptance into a certain group or class in society (Turner and Oakes, 1986). Findings of this study have shown that if people do not meet the perceived standards set by people they look up to on social media in terms of beauty, then they begin to lose their sense of self-worth and start feeling like they are not as good or as beautiful. The support is partial because it was not fully confirmed in this study that people seek to belong to a certain group or merely just want to look like their social media mentors, influencers, or idols. By not distinctly studying this, it will be difficult to categorically state that the social identity theory was fully confirmed. The findings of this study however fully support the social comparison theory because the study shows that people who make frequent use of social media define or evaluate their sense of self-worth, beauty, and value based on their perception of others on social media. By proving this hypothesis right, the researchers have shown that people most engage in upward comparison on social media which in turn has an effect on their self-esteem and leads to body dissatisfaction.

This study has charted a new course in the study of social media usage, mental health, and its manifestations on youths and young adults. By examining the mediating role of social anxiety on the relationship between social media usage and body dissatisfaction, this study has approached media effects studies from a novel perspective. The issue of body dissatisfaction among today's youths is a front-burner issue and has become one of the most talked-about issues in modern media. Body positivity and acceptance are encouraged and actively sought in both academic and general society, so any study that clarifies this issue and sheds light on the root causes of body dissatisfaction will surely help in developing a long-lasting solution using modern-day techniques.

This study sought to find out the mediating role of social anxiety on the relationship between social media usage and body dissatisfaction. The findings of this study showed a significant positive relationship between social media usage and body dissatisfaction. The findings proved that heavy users of social media are significantly more likely to suffer from body dissatisfaction. In a similar vein, the findings also showed that there is a significant positive relationship between social media usage and social anxiety. This suggested that people that frequently make use of social media have a much higher chance of suffering from social anxiety than people that rarely or moderately make use of social media. Finally, findings showed that social anxiety mediates the relationship between social media usage and body dissatisfaction. It indicated that people with high levels of social anxiety are more likely to suffer from body dissatisfaction as a direct result of heavy social media usage.

In the literature review, it was mentioned that Norway has passed legislation that makes it compulsory for influencers to indicate that their pictures have been retouched. This is in a bid to significantly reduce body dissatisfaction and unhealthy beauty standards in Norway. Whether this initiative will be effective in improving body positivity in Norway remains to be seen. However, the researchers think this is a worthwhile idea and recommend that other countries, especially the more socially influential ones do the same thing. This should not be limited to social media but should also be introduced in popular culture like film and music. More realistic and everyday-looking people should be projected on the big screen and in music videos to promote the idea of a more diverse definition of beauty.

This study was limited to university students in Uganda, the decision to focus on university students was because they fall within the age bracket of social media users according to Facebook analytics and other social media data. However, there is a need to expand this study beyond university students, as a lot of individuals outside the university environment are also ardent users of social media and maybe affected differently. Given this, the researchers are recommending a more holistic study that considers the wider society and other media forms (such as TV) and how they affect the perception of body dissatisfaction among their users.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary materials, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Kampala International University and Victoria University. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

YJ: research design and variables definition, initial data analysis, and finalizing the findings. AA: collecting the data and literature review. GN: data analysis and drafting the findings. All authors worked on the last version of the paper.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®). American Psychiatric Publishing. doi: 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

Andreassen, C. S., and Pallesen, S. (2014). Social network site addiction-an overview. Curr. Pharm. Des. 20, 4053–4061. doi: 10.2174/13816128113199990616

Antony, M. M., Rowa, K., Liss, A., Swallow, S. R., and Swinson, R. P. (2005). Social comparison processes in social phobia. Behav. Ther. 36, 65–75. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(05)80055-3

Attie, I., and Brooks-Gunn, J. (1989). Development of eating problems in adolescent girls: a longitudinal study. Dev. Psychol. 25, 70–79. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.25.1.70

Blowers, L. C., Loxton, N. J., Grady-Flesser, M., Occhipinti, S., and Dawe, S. (2003). The relationship between sociocultural pressure to be thin and body dissatisfaction in preadolescent girls. Eat. Behav. 4, 229–244. doi: 10.1016/S1471-0153(03)00018-7

Coorley, W. W.. (1978). Explanatory observation studies. Educ. Res. 7, 9–15. doi: 10.3102/0013189X007009009

Corning, A., Krumm, A., and Smitham, L. (2006). Differential social comparison processes in women with and without eating disorder symptoms. J. Couns. Psychol. 53, 338–349. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.53.3.338

Coyne, S. M., Rogers, A. A., Zurcher, J. D., Stockdale, L., and Booth, M. (2020). Does time spent using social media impact mental health?: An eight year longitudinal study. Comput. Hum. Behav.104:106160. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2019.106160

Deters, F. G., and Mehl, M. R. (2013). Does posting Facebook status updates increase or decrease loneliness? An online social networking experiment. Soc. Psychol. Pers. Sci. 4, 579–586. doi: 10.1177/1948550612469233

Dittmar, H., and Howard, S. (2004). Thin-ideal internalization and social comparison tendency as moderators of media models' impact on women's body-focused anxiety. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 23, 768–791. doi: 10.1521/jscp.23.6.768.54799

Duggan, M.. (2015). The Demographics of Social Media Users in 2015. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center.

Feinstein, B. A., Hershenberg, R., Bhatia, V., Latack, J. A., Meuwly, N., and Davila, J. (2013). Negative social comparison on Facebook and depressive symptoms: rumination as a mechanism. Psychol. Pop. Media Cult. 2, 161–170. doi: 10.1037/a0033111

Ferguson, C. J., Muñoz, M. E., Garza, A., and Galindo, M. (2014). Concurrent and prospective analyses of peer, television and social media influences on body dissatisfaction, eating disorder symptoms and life satisfaction in adolescent girls. J. Youth Adolesc. 43, 1–14. doi: 10.1007/s10964-012-9898-9

Festinger, L.. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Hum. Relat. 7, 117–140. doi: 10.1177/001872675400700202

FHEHealth (2020). Body Image and Social Media Questionnaire. Available online at: https://fherehab.com/news/bodypositive/

Frison, E., and Eggermont, S. (2015). The impact of daily stress on adolescents' depressed mood: the role of social support seeking through Facebook. Comput. Hum. Behav. 44, 315–325. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2014.11.070

Garner, D. M.. (2004). Eating Disorder Inventory-3: Professional Manual. Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc.

Gilbert, P.. (2000). “Social mentalities: Internal ‘social' conflict and the role of inner warmth and compassion in cognitive therapy,” in Genes on the Couch: Explorations in Evolutionary Psychotherapy, eds P. Gilbert and K. G. Bailey (Routledge), 118–150.

Greene, J., Cohen, D., Siskowski, C., and Toyinbo, P. (2017). The relationship between family caregiving and the mental health of emerging young adult caregivers. J. Behav. Health Serv. Res. 44, 551–563. doi: 10.1007/s11414-016-9526-7

Gregory, B., and Peters, L. (2017). Changes in the self during cognitive behavioural therapy for social anxiety disorder: a systematic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 52, 1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2016.11.008

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., and Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective, 7th Edn. Pearson Education International.

Hussain, Z., and Griffiths, M. D. (2018). Problematic social networking site use and comorbid psychiatric disorders: a systematic review of recent large-scale studies. Front. Psychiatry 9:686. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00686

Jarrar, Y., Awobamise, A., Nnabuife, S., and Nweke, G. E. (2020). Perception of pranks on social media: clout-lighting. Online J. Commun. Media Technol. 10:e202001. doi: 10.29333/ojcmt/6280

Jenkins-Guarnieri, M. A., Wright, S. L., and Johnson, B. (2013). Development and validation of a social media use integration scale. Psychol. Pop. Media Cult. 2, 38–50. doi: 10.1037/a0030277

Jiang, S., and Ngien, A. (2020). The effects of instagram use, social comparison, and self-esteem on social anxiety: a survey study in Singapore. Soc. Media Soc. 6, 1–10. doi: 10.1177/2056305120912488

Jiang, Y.. (2021). Problematic social media usage and anxiety among university students during the COVID-19 pandemic: the mediating role of psychological capital and the moderating role of academic burnout. Front. Psychol. 12:612007. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.612007

Jiotsa, B., Naccache, B., Duval, M., Rocher, B., and Grall-Bronnec, M. (2021). Social media use and body image disorders: association between frequency of comparing one's own physical appearance to that of people being followed on social media and body dissatisfaction and drive for thinness. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18:2880. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18062880

Karim, F., Oyewande, A. A., Abdalla, L. F., Chaudhry Ehsanullah, R., and Khan, S. (2020). Social media use and its connection to mental health: a systematic review. Cureus 12:e8627. doi: 10.7759/cureus.8627

Keles, B., McCrae, N., and Grealish, A. A. (2020). A systematic review: the influence of social media on depression, anxiety and psychological distress in adolescents. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 25, 79–93. doi: 10.1080/02673843.2019.1590851

Killen, J. D., Taylor, C. B., Hayward, C., Haydel, K. F., Wilson, D. M., Hammer, L., et al. (1996). Weight concerns influence the development of eating disorders: a 4-year prospective study. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 64, 936–940. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.64.5.936

Kim, H. H.. (2017). The impact of online social networking on adolescent psychological well-being (WB): a population-level analysis of Korean schoolaged children. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 22, 364–376. doi: 10.1080/02673843.2016.1197135

Lenhart, A., Smith, A., Anderson, M., Duggan, M., and Perrin, A. (2015). Teens, Technology and Friendships. Available online at: http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/08/06/teens-technology-and-friendships/

Leonard, K. E., and Blane, H. T. (1988). Alcohol expectancies and personality characteristics in young men. Addict. Behav. 13, 353–357. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(88)90041-x

Lepp, A., Barkley, J. E., and Karpinski, A. C. (2014). The relationship between cell phone use, academic performance, anxiety, and Satisfaction with life in college students. Comp. Hum. Behav. 31, 343–350. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2013.10.049

Liebowitz, M. R.. (1987). Social phobia. Mod. Probl. Pharmacopsychiatry. 22, 141–173. doi: 10.1159/000414022

Lilley, C., Ball, R., and Vernon, H. (2014). The Experiences of 11–16 Year Olds on Social Networking Sites. NSPCC. Available online at: https://www.nspcc.org.uk/globalassets/documents/research-reports/experiences-11-16-year-olds-socialnetworking-sites-report.pdf

Marino, C., Gini, G., Vieno, A., and Spada, M. M. (2018). The associations between problematic Facebook use, psychological distress and well-being among adolescents and young adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 226, 274–281. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.10.007

Maulik, P., Eaton, W., and Bradshaw, C. (2011). The effect of social networks and social support on mental health services use, following a life event, among the Baltimore epidemiologic catchment area cohort. J. Behav. Health Serv. Res. 38, 29–50. doi: 10.1007/s11414-009-9205-z

McCrae, N., Gettings, S., and Purssell, E. (2017). Social media and depressive symptoms in childhood and adolescence: a systematic review. Adolesc. Res. Rev. 2, 315–330. doi: 10.1007/s40894-017-0053-4

McKee, S., Smith, H. J., Koch, A., Balzarini, R., Georges, M., and Callahan, M. P. (2013). Looking up and seeing green: women's everyday experiences with physical appearance comparisons. Psychol. Women Q. 37, 351–365. doi: 10.1177/0361684312469792

Mitchell, M. A., and Schmidt, N. B. (2014). An experimental manipulation of social comparison in social anxiety. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 43, 221–229. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2014.914078

O'Keeffe, G., and Clarke-Pearson, K. Council on Communications Media (2011). The impact of social media on children, adolescents and families. Pediatrics 124, 800–804. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0054

Orsillo, S. M.. (2001). “Measures for social phobia,” in Practitioner's Guide to Empirically Based Measures of Anxiety. AABT Clinical Assessment Series, eds M. M. Anthony and S. M. Orsillo (New York, NY: Klumer Academic/Plenum Publisher), 165–187.

Schlenker, B. R., and Leary, M. R. (1982). Social anxiety and self-presentation: a conceptualization model. Psychol. Bull. 92, 641–669. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.92.3.641

Statista (2021). Number of Social Network Users Worldwide From 2017 to 2025. Available online at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/278414/number-of-worldwide-social-network-users/

Stein, M. B., and Sareen, J. (2015). Generalized anxiety disorder. N. Engl. J. Med. 373, 2059–2068. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1502514

Stormer, S. M., and Thompson, J. K. (1996). Explanations of body image disturbance: a test of maturational status, negative verbal commentary, social comparison, and sociocultural hypotheses. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 19, 193–202. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-108X(199603)19:2<193::AID-EAT10>3.0.CO;2-W

Taylor-Jackson, J., and Moustafa, A. (2021). The relationships between social media use and factors relating to depression. Nat. Depression 171–182. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-817676-4.00010-9

Teo, A., Choi, H., and Valenstein, M. (2013). Social relationships and depression: ten-year follow-up from a nationally representative study. PLoS ONE 8:e62396. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062396

The Washington Post. (2021). Why Experts Say Norway's Retouched Photo Law Won'T Help Fight Body Image Issues. Available online at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/wellness/photo-edit-social-media-norway/2021/07/08/f30d59ca-df2c-11eb-ae31-6b7c5c34f0d6_story.html

Thorisdottir, I. E., Sigurvinsdottir, R., Asgeirsdottir, B. B., Allegrante, J. P., and Sigfusdottir, I. D. (2019). Active and passive social media use and symptoms of anxiety and depressed mood among icelandic adolescents. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 22, 535–542. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2019.0079

Turner, J. C., and Oakes, P. J. (1986). The significance of the social identity concept for social psychology with reference to individualism, interactionism and social influence. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 25, 237–252. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8309.1986.tb00732.x

Vogel, E. A., Rose, J. P., Roberts, L. R., and Eckles, K. (2014). Social comparison, social media, and self-esteem. Psychol. Pop. Media Cult. 3, 206–222. doi: 10.1037/ppm0000047

Weeks, J. W., Rodebaugh, T. L., Heimberg, R. G., Norton, P. J., and Jakatdar, T. A. (2009). “To avoid evaluation, withdraw”: fears of evaluation and depressive cognitions lead to social anxiety and submissive withdrawal. Cogn. Ther. Res. 33, 375–389. doi: 10.1007/s10608-008-9203-0

Wong, A., Ho, S., Olusanya, O., Antonini, M. V., and Lyness, D. (2020). The use of social media and online communications in times of pandemic COVID-19. J. Intensive Care Soc. 22, 255–260. doi: 10.1177/1751143720966280

Zsido, A. N., Arato, N., Lang, A., Labadi, B., Stecina, D., and Bandi, S. A. (2020). The connection and background mechanisms of social fears and problematic social networking site use: a structural equation modeling analysis. Psychiatry Res. 292:113323. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113323

Keywords: social anxiety, body dissatisfaction, body image, social media use, body satisfaction

Citation: Jarrar Y, Awobamise AO and Nweke GE (2022) The Mediating Effect of Social Anxiety on the Relationship Between Social Media Use and Body Dissatisfaction Among University Students. Front. Commun. 7:900257. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2022.900257

Received: 20 March 2022; Accepted: 11 April 2022;

Published: 29 April 2022.

Edited by:

Ahmet Güneyli, European University of Lefka, TurkeyReviewed by:

Metin Ersoy, Eastern Mediterranean University, TurkeyCopyright © 2022 Jarrar, Awobamise and Nweke. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yosra Jarrar, eWphcnJhckBhdWQuZWR1

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.