- Department of Experimental Psychology, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom

The “phantasmagoria” is a term that originally referred to the ghost lantern shows first staged in France at the end of the 18th Century by the Belgian inventor and entertainer Étienne-Gaspard Robertson. The question to be addressed in this review concerns the link between the phantasmagoria (defined as a ghostly visual entertainment) and the multisensory sensorium (or sensory overload) of the fairground and even, in several other cases, the Gesamtkunstwerk (the German term for “the total work of art”). I would like to suggest that the missing link may involve the ghost attractions, such as Dr. Pepper's Ghost (first developed at the Royal Polytechnic Institute in London in the 1860s), and the Phantasmagoria, that were both promoted in fairgrounds across England in the closing decades of the 19th Century.

Introduction

The “phantasmagoria” originally referred to the ghost lantern show that originated in France at the end of the 18th Century (see Barber, 1989; and Mannoni and Brewster, 1996, for reviews). But what, exactly, is the link is between the phantasmagoria (as a historic form of ghostly visual entertainment) and the multisensory sensorium to be found at the fairground or theme park. In this review, I would like to suggest that the missing link may involve the ghost shows/attractions, including Dr. Pepper's Ghost (patented in 1863; and popularized at the Royal Polytechnic Institute in London; Dircks, 1863; Pepper, 1890),1 and the Phantasmagoria that were both promoted (as a form of entertainment) in fairgrounds across England and the US in the closing decades of the 19th Century. Intriguingly, over the last decade or so, there has been something of a revival of interest in Pepper's Ghost-type illusions, amongst a public who has long forgotten the origins of this effect (e.g., see Ganz, 2012; Kennedy, 2012; see also Lekowski, 1996; Price, 2015; Gingrich, 2016), hence reintroducing an air of mystery that had been lost to previous audiences.

In this review, I trace the history of the “phantasmagoria”. Originally, the term referred to a disturbing perceptual (though, in fact, it primarily seems to have referred to a unisensory visual) experience or illusion.2 The architectural theorist, Pérez-Gómez (2016, p. 14–15) defines the phantasmagoria as a unisensory phenomenon when he writes at one point that: “captivated by purely visual phenomena, by the phantasmagoria of the city.” In particular, the term was used when referring to a frightening, and for some occasionally terrifying (Warner, 2006–2007, p. 6), horror ghost illusion/show first staged at the end of the 18th Century in France (Ndalianis, 2004). The original term “Fantasmagorie” is derived from the Greek for “phantasm assembly” (see Castle, 1988; Barber, 1989, p. 74). In the decades that followed, this form of entertainment gained widespread popularity in North America, England, and several other European countries (including Spain; see Barber, 1989, for a review). In the latter half of the 19th Century, the visual illusion created by Professor John Henry Pepper3 of London's Royal Polytechnic Institute on Regent Street, allowing for the visual images/ghosts displayed to become far more dynamic than had been the case previously (“Reynaud's Optical Theater”, 1892), was incorporated into everything from fairground shows, to theatrical and operatic performances by traveling theater companies (see Burdekin, 2015, for a review). The visual illusion underpinning Dr. Pepper's Ghost was also incorporated and further developed by magicians as a new form of “visual conjuring” (see Barnouw, 1981, p. 24; Steinmeyer, 2003)4.

Phantasmagoria as multisensory overload in the fairground/theme park

Focusing on the opening decades of the 20th Century, Sally Lynn (2006) charts the emergence of kinaesthetic thrills as part of early theme park rides. She describes theme parks such as Luna Park on Coney Island (Register, 2001), as “fantasy lands”. Elsewhere, Pursell (2013, p. 75) refers to the experiential offerings that such venues provided as a kind of “industrial saturnalia”. Intriguingly, Lynn repeatedly mentions the “phantasmagoria” and the sensory overload that such theme parks may have presented to their visitors. As Kasson (1978, p. 49) puts it: “photographs give some indication of this [environmental phantasmagoria], but they alone cannot do it justice… Instead he invites the reader to envision the total-body experience of pleasure seekers at Coney Island: We must try to imagine the smells of circus animals, the taste of hot dogs, beer and seafood, the jostle of surrounding revelers, the speed and jolts of amusement rides, and, what especially impressed observers, the din of barkers, brass bands, roller coasters, merry-go-rounds, shooting galleries... above all, the shouts and laughter of the crowd itself.” (as cited in Lynn, 2006, p. 304). Notice here how the term “phantasmagoria” refers to the total multisensory milieu, or sensorium (see Jütte, 2005, on the notion of the “sensorium”), of the patrons' experience of the fairground/amusement park. There can be little doubting that such multisensory overload/overstimulation was to leave a lasting impression on many of those who visited.

The Gesamtkunstwerk as phantasmagoria

Another context in which the term phantasmagoria is sometimes mentioned is in relation to Richard Wagner's notion of the Gesamtkunstwerk, or total work of art (Paulin, 2000; see also Joe and Gilman, 2010; John, 2010). Here, the term describes an awe-inspiring and/or possibly overwhelming form of art, an immersive multisensory experience that ideally engaged all (or at the very least several) of the audience's senses, often facilitated by means of the latest in technological innovation. For instance, Adorno (2005, p. 80) once described the Wagnerian phantasmagoria as “the earliest wonder of technology”. Benjamin also famously discussed Wagner's opera as a kind of phantasmagoria (see Daub, 2009).5 In fact, Tresch (2011, p. 17) writes that: “Grand opera in its entirety has been seen as mass-produced phantasmagoria, mechanically produced illusion presaging the commercial deceptions of the society of the spectacle.” Later, Tresch wrote that “the most “spectacular” public performances of the period addressed not just the eye but the ear with sound, speech, and music, creating immersive, fully embodied, and shared experiences. These were audiovisual phantasmagoria, performances meant to generate thrills and perceptual disorientations by overwhelming a combination of the senses.” (Tresch, 2011, p. 20, italics in original). Tresch uses the term phantasmagoria, then, not merely to refer to a form of sensory deception, but also to refer to various audiovisual forms of entertainment, playful illusion, and scientific/instructive “edutainment” (e.g., Gunning, 2009; see Podestà and Addis, 2007, on the notion of “edutainment”; and see Muelrath, 2018; Slessor, 2018; Steinbock, 2019, for other contemporary uses of the term “phantasmagoria”)6.

On the origins of the phantasmagoria as visual ghost show

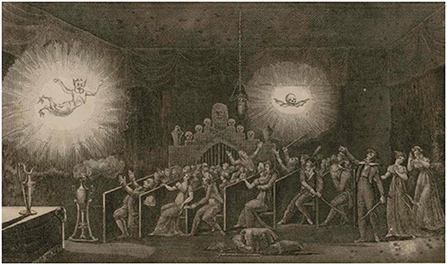

Barber (1989) dates the origins of the phantasmagoria, or ghost lantern show, where shadows of skeletons and ghosts were projected on screens and walls in darkened atmospheric environments, to the end of the 18th Century in France. Barber argues that Étienne-Gaspard Robertson's Fantasmagorie (coined from the Greek “Phantasmagoria”, meaning assembly of phantasms; Warner, 2006–2007 was probably the most influential magic lantern ghost show of the early 19th century (Robertson, 1831).7 According to Barber, Robertson who came from Liège, Belgium, first staged his exhibition at the Pavillon de l'Echiquier in Paris in around 1799 (though earlier dates have been mentioned by others). For instance, Barnouw (1981, p. 19) dates Robertson's arrival in Paris 5 years earlier, to 1794. The exhibition soon moved to an abandoned chapel (abandoned by the resident nuns following the 1790 Revolution; see Mannoni and Brewster, 1996, p. 403), around December 23rd, 1798 (see Mannoni and Brewster, 1996) the Gothic convent at the Couvent des Capucines, in Paris, where it played for six years (see Barber, 1989, p. 74). According to Barnouw (1981, p. 19), this move may have happened as early as 1797 (Appropriately enough, the latter venue had formerly held the skeletal remains of monks.) An engraving that appears at the front of Robertson's book highlight the rear-projection of the slides onto smoke that were an occasional feature of the early fantasmagoria (see Figure 1), along with the more conventional screen-based projections (see Barnouw, 1981; Chapter 3. The Fantasms; see also Ndalianis, 2004).

Figure 1. Early image of the phantasmagoria. https://webarchive.nla.gov.au/awa/20040204192315/http://www.acmi.net.au/AIC/PHANTASMAGORIE.html.

Although the focus in many of the written accounts of the phantasmagoria has been specifically on ghostly visual apparitions,8 Barber (1989, p. 84) notes how in Robertson's staging was: “Designed to appeal to popular audiences, the Phantasmagoria made use of music, sound effects, and the commentary of a narrator to enliven the otherwise silent image.” Barber describes the audiovisual experience that could be expected from the phantasmagoria's creator as follows “…Robertson quickly extinguished the light so as to plunge the room in total darkness for the next hour and a half. This in itself was frightening enough, but to increase the terror he proceeded to lock the doors. The audience then heard the noise of rain, thunder, and a funereal bell calling forth phantoms from their tombs, and Franklin's Harmonica, a form of musical, water-filled glasses, provided a haunting sound which served both here and throughout the show to mask of the goings-on behind the scenes.” (Barber, 1989, p. 74–75; Hecht, 1984). Barber goes on to suggest that: “Robertson was actually more than a lanternist, and the Fantasmagorie could be called a true multimedia event.” (Barber, 1989, p. 77). It can, then, perhaps be suggested that what really helped to elevate this form of entertainment over earlier unisensory (visual) lantern shows was the incorporation of an auditory, or multisensory, element into proceedings. By adopting a broader definition of the term, Tresch (2011) suggests that such audiovisual phantasmagoria were not altogether unheard of in France in the middle of the 19th Century. Given the growing interest in multisensory experience design (see Velasco and Obrist, 2020), one might also consider whether contemporary practice might have anything to learn from the entertaining antics of such early showmen?

One surviving playbill from 1802 describes the magician Paul de Philipsthal bringing his Phantasmagoria to London's Lyceum Theater on The Strand (see Barber, 1989, p. 78–79; Barnouw, 1981, p. 23), though, according to Barber, the show started in late 1801. Ghost lantern shows were a very popular form of entertainment in the opening decades of the 19th Century in the US and England, being particularly popular in the US between 1803 and 1839 (Barber, 1989, p. 78).9 However, one of the fundamental limitations that may well have led to their eventual demise as a form of popular entertainment was the static nature of the images shown; Being painted on glass, they lacked the necessary vitality (see Hopkins, 2020, p. 7). By enabling the projection of living people into the air (Hopkins, 2020, p. 8), Dr. Pepper's Ghost, a Victorian device for creating animated ghostly illusions on the stage (Burdekin, 2015), was to change all that.

On the popularizing of visual illusions at the royal polytechnic institute

London's Royal Polytechnic Institute first opened its doors to the public in August of 1838 (Brooker, 2007).10 In the years that followed, the venue became famous for popularizing science by means of public demonstrations. The shows put on at the institute evolved with the development of a variety of ghostly visual illusions (e.g., Speaight, 1963, 1989; Weeden, 2008). In the 1860s, the then director of the Institute, Dr. Pepper created, or better said helped to develop, a clever system for projecting living persons in the air (Pepper, 1890). Although there is some controversy surrounding the original development of the idea for the invention, it appears to have been first suggested by Henry Dircks, a civil engineer, in 1858;11 Thereafter, in 1862, it was modified by Prof. John Pepper, a chemist, inventor, and showman (Weeden, 2008), as well as director of the Institute. A patent application was filed in 1863 (Pepper and Dircks, 1863; Burdekin, 2015).12

Surprisingly, a very similar apparatus may well already have been used several decades earlier for an 1824 staging of Faust in London. According to Burwick (1990, p. 188), reflections were used in a scene where Mephistopheles carries Faustus through the air. Brewster (1832) also outlined the basic idea of using double mirror reflections to give the impression that the actors standing below the stage floating on it in his book, Natural Magic. Meanwhile, Wilkie (1900) mentions early performances involving ghosts that would also seem to predate Pepper's patent. Nevertheless, despite these earlier examples, it was Pepper who was subsequently popularly credited with the innovation.

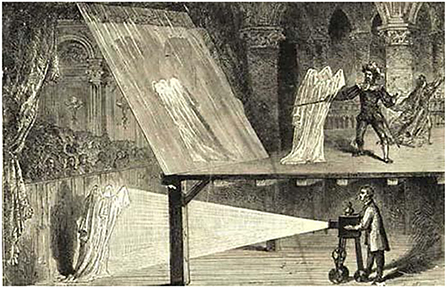

At the Royal Polytechnic Institute, a person situated below the stage could be made to appear as though they were standing on the stage with the actors via the clever use of lighting and mirrored glass. Importantly, if done well, this deceit was invisible to the audience (see Figure 2). Typically, the glass was hidden away from the audience's view during the majority of the performance, and only hauled out from the bespoke deep slots set in the stage using ropes as and when required (see Pepper, 1890, p. 10–11; Steinmeyer, 2003, p. 37). To work effectively, the illusion required the auditorium to be completely dark (Taylor, 1863, p. 307). According to Burdekin (2015), the best view of the illusion would have been from the theater's front stalls (which could be booked for a price). According to Steinmeyer's authoritative account of the history of the Pepper's Ghost illusion, the ghostly apparition would lie on an inclined place at c. 45 degrees [see the illustrations in Steinmeyer (2003), p.s 34, 37].13 Burdekin (2015) presents a slightly different arrangement with the ghostly actor(s) standing in the pit (known as “the oven” because of the heat from the powerful lamps) with their actions being reflected onto the glass via a mirror. This arrangement is also the one that appears in Ganot (1872); Pepper (1890), see also Groth (2007; Figures 5, 6; ‘The magic lantern: How to buy and how to use it, and how to raise a ghost (“by a mere phantom”). 1880').

Figure 2. Phantasmagoria display from the opening pages of Robertson (1831).

In a work originally published in 1898, Hopkins (2020) explains the workings of a wide range of magic tricks and stage illusions, including one by the name of “Metempsychosis” [see also Brooker, 2007, on metempsychosis, first introduced in 1879, according to Weeden (2008), p. 94]. This appears very similar to Dr. Pepper's Ghost, though it incorporates the use of horizontal, rather than vertical, reflection, thus allowing both real actor and ghost to stand upright on stage (and at the same time presumably avoiding the heat of the oven). According to Hopkins, metempsychosis was a joint invention of Messrs. Walker and Pepper of London, invented by the former with the latter helping to perfect it (Hopkins, 2020, p. 532).14 It would seem that essentially the same visual illusions could have been obtained using either Dr. Pepper's Ghost or Metempsychosis, though the former undoubtedly became much more well-known. Indeed, as we will see in the next section, over the following 40 years, the illusion was to travel far beyond the confines of the Royal Polytechnic Institute stage.15

From the royal polytechnic institute to the fairground via the theater

The very first performance of Dr. Pepper's Ghost on December 24th, 1862, involved a ghost materializing in a scene from “The Haunted Man and The Ghost's Bargain” (Dickens, 1848) performed on the small stage at the Royal Polytechnic Institute with Pepper himself apparently reading the script (Steinmeyer, 2003; Groth, 2007, p. 29). According to Groth, this choice of fiction may have been especially appropriate given the shared interest of Dickens and Pepper in the fallibility of perception and memory. Pepper made an estimated £12,000 in 15 months when using the illusion at the Royal Polytechnic (see Pepper, 1890, p. 35; Burdekin, 2015), suggesting that something like 240,000 visitors came through the Institute's doors during this period. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the Pepper's Ghost illusion was initially staged in performances involving ghosts (see Pepper, 1890). Theaters soon licensed the idea, and the illusion was also popular at the opera.16 Hopkins (2020, p. 8) notes how the apparatus for producing the Pepper's Ghost illusion was often used thereafter in further dramatizations of Charles Dickens's “The Haunted Man” (see also Carlson, 2014), as well as in other works such as Bluwer's “Strange Story”, and Dumas' “Corsican Brothers”.

In his enlightening review, Russell Burdekin (2015) writes of how various traveling companies of actors, including one company by the name of The Original Pepper's Ghost and Spectral Opera Company, put on various popular plays and operas during this period (see Burdekin, 2015). According to Burdekin, both the spectral opera shows and the ghost shows disappeared following the advent of film (another form of illusion). That said, the ghostly themes permeated early film, with Barnouw highlighting the close link between Pepper's Ghost, visual conjuring, and the early development of film (Barnouw, 1981, p. 41). Indeed, in his authoritative account of the evolution of stage magic, Steinmeyer (2003) traces the profound influence that the Dr. Pepper's Ghost illusion had on the development of “visual conjuring” that became so popular in the years after Pepper's illusion was first introduced to the public on the Institute's London stage.

Pepper aggressively protected the patent challenging several unlicensed theatrical productions (see Standard, 1863, p. 3 Steinmeyer, 2003, p. 36, 40). According to Steinmeyer (2003, p. 40): “Pepper attempted to stop these unauthorized copies in Britain. A Mr. King was forced to withdraw his illusion from the British music halls, but not every showman respected Pepper's claim.” Ghost illusions were also a popular form of entertainment in France (Steinmeyer, 2003, p. 41; Burdekin, 2015). However, given the existence of an earlier French patent filed in 1852 by Pierre Séguin (see Steinmeyer, 2003, p. 33), and given the peculiarities of French patent law, Pepper was unable to protect his invention over there (Burdekin, 2015), nor was he able to protect it in the US (Wobensmith, 1928; Loew, 2012). Jackson (2019, p. 67) also reports a London “comic burlesque” from 1865 entitled Hodge Podge using “Pepper's Ghost” throughout the performance he claims that “the latest theatrical special effect, a version of which was on display in virtually every music hall in the capital”.

According to the popular narrative, the Dr. Pepper's Ghost illusion then took on a life of its own in mainstream theaters only thereafter to be found as a fairground attraction (Groth, 2007, p. 57; Burdekin, 2015). As a case in point, the author's great-great-grandfather Randall Williams, known as ‘the King of Showmen', frequently presented Dr. Pepper's Ghost and the Phantasmagoria around the Northern England fairground circuit during the 1880s and well into the 1890s (Starsmore, 1975, p. 65–66; Heard, 2002, 2008; “Professor Randall Williams' Great Ghost Show”, 1881; Gashinski, 2011).17 It must remain, at least for now, open to speculation as to whether Williams himself visited the Royal Polytechnic Institute and took the idea away to develop it for use on the fairground. Relevant in this regard, according to the reminiscences of one traveling showman, a number of showmen did indeed make their way to the Royal Polytechnic Institute in order to see Pepper's show, and try to figure out how exactly the illusion worked. That said, given Pepper's aggressive attempts to protect his invention, the question remains as to how/why Randall Williams and other showmen were allowed to promote Dr. Pepper's illusion, given that they often referred to the patented illusion by name. It is unclear whether the fairground version was phantasmagoric in name only (Barber, 1989, p. 82–83; “The Phantasmagoria Effect”, 1879) and/or whether or not the presentation of Dr. Pepper's Ghost was licensed for use on the fairground by Williams.18

Unfortunately, the precise nature of the proceedings/entertainments that took place behind the flaps of the fairground tent is obviously very difficult to reconstruct in hindsight given the lack of physical artifacts from this era. In the absence of both written records and physical relics, most evidence concerning the emergence of the phantasmagoria as a fairground entertainment in the latter half of the 19th Century must rely on newspaper advertisements (promoting the arrival of the fair) and subsequent reports from those who had attended. At the same time, however, one can find occasional descriptions, such as Sellman (1975, p. 4–11), describing life on the road for such fairground ghost shows, while George Speaight, 1989, p. 23–24) describes content of one such show, as involving an auditory component (comprising both speech and music).

Coda: From the phantasmagoria to the emergence of the moving picture

The popularity of shows such as Dr. Pepper's Ghost and the Phantasmagoria on the fairground were short-lived, stretching primarily through the 1870s and 1880s. In part, this is because such illusory images were soon replaced by the arrival of moving pictures (Mellor, 1996)—another kind of ghost show—and thereafter, the fairground bioscope shows (Barnouw, 1981, p. 63; Toulmin, 1998; “The fairground bioscope shows, n.d.”).19 It should also be noted that the emergence of increasingly thrilling fairground rides may have also played its part (see Spence, 2022, for a review). Groth (2007, p. 65) notes that: “Randall Williams's popular walk-up version of the ghost show in the 1890s did lead to his “Grand Phantascopical Exhibition” at the World's Fair in Islington in 1896, which included the first fairground cinema.” (see also Heard, 1996, p. 3). And while a number of the earliest film showings included music [including one put on at Windsor Palace, for royalty, see Barnes (1983, p. 132)], it is unclear how common such multimedia presentations were in the very early days of moving pictures. Here, once again, the research to date concerning the films shown at the bioscope shows is very limited, leading the film historian Barnes (1983, p. 177) to note that: “Much research needs to be done on the fairground film shows” (see also Loew, 2012).

The Original Pepper's Ghost and Spectral Opera Company, which was founded in 1869, survived till end of century according to Burdekin (2015). Burdekin further writes that: “By the turn of the century the companies, followed soon after by the ghost shows, had disappeared altogether hastened on their way by the advent of film and its much greater potential for illusion, which “put quite in the shade the extraordinary optical delusions effected by ‘Pepper's Ghost' some years ago” (italics in original). In fact, one of the first people to show moving pictures on the fairground was none other than the King of Showmen himself, Randall Williams with what was proudly described as the largest organ in the North (Barnes, 1967, 1983; Mellor, 1996).20 By 1897, though, many other showmen were also presenting films on the fairground (see Barnes, 1983, p. 176–177). Williams showed one of the films taken of Queen Victoria's jubilee using cinematograph cameras.21 Even the Royal Polytechnic got in on the act, with Burdekin (2015) noting that Pepper's Ghost was revived by Pepper at Christmas 1889 and was also one of the events included in a Victorian Era show at Earl's Court to celebrate Queen Victoria's reign as part of her diamond jubilee in 1897 (see Morning Post, 1897, p. 1). However, cinema soon came to replace the traveling fairground (bioscope) shows and music-hall entertainments (Quigley Jr. 1948, pp. 75–79; Barnes, 1976, 1983, p. 177; Sanger, n.d.).22 There were a number of important developments of the technology in the early 1900s including the Viennese Kinetoplastikon, Messter's Ton/Bild, and the Alabastra (see Loew, 2012, for a detailed review). The Alabastra involved a film being projected using the Pepper's Ghost set-up in front of a stage. Looking back, it is interesting to see the skepticism that some in the business had about whether multiple-reel film drama would ever take off (see Schwarz, 1992; Loew, 2012, p. 155).

Magic, mysticism, and education/entertainment

Interest in ghostly apparitions and spirit imagery (a phantasmagoria in other words) did not disappear entirely with the popular emergence of photography and the moving image. As highlighted by Tompkins (2019), the fascination with spirit photography continued into the early decades of the 20th Century amongst those wanting (or offering) to make contact with the dead/spirit world. Such pursuits were especially popular following the massive loss of life resulting from the First World War.23 In fact, it has been suggested that spiritualists were regular attendees at the early performances of the Pepper's Ghost illusion at London's Royal Polytechnic Institute too, though Pepper himself apparently chose to ignore all the mail he received from them (see Evans, 1909, p. 89; Steinmeyer, 2003). By contrast, the spirit mediums who so irritated the likes of magician Houdini pretended to be making contact with the other side (see also Houdini, 1909, 1924; Robert-Houdin, 1975; Tompkins, 2019). Though, as Barnouw (1981, p. 24) notes, some spiritualists also seized on the opportunities provided by the phantasmagoria (Taylor, 1863, p. 307, even mentions the link with spirit photography in the first year in which the ghost illusion was presented).

Crucially, however, the Dr. Pepper' Ghost illusion and the phantasmagoria shows were explicitly promoted as scientific illusion, not reality (e.g., at the Royal Polytechnic Institute; see Barber, 1989, p. 78), with the audiences actively encouraged to rationally demystify the optical phenomena they were exposed to Groth (2007, p. 49), Gunning (2007). Indeed, according to Pepper himself, his shows were designed to contrast “real science… with unreal science called Spiritual Manifestations.” (see Brooker, 2007, p. 203). The Royal Polytechnic Institute's dual function of popularizing science and as a place of entertainment, of course, resonating with contemporary attempts to promote the public understanding of science through multisensory/multimedia entertainments. Here, it is also worth stressing the fact that the phantasmagoria shows on the fairground were similarly promoted as a form of ‘secular entertainment' (Warner, 2006–2007, p. 5).24

Conclusions

In conclusion, the missing link between the phantasmagoria, as spectral illusion show and the phantasmagoric multisensory overload of the fairground/theme park/Gesamtkunstwerk can be traced back to the closing decades of the 19th Century when Victorian ghost shows such as Dr. Pepper's Ghost and the Phantasmagoria were such a popular feature of the fairground circuit in England. Although first introduced, explained, and patented by one Prof. Pepper (at that time, the director of London's Royal Polytechnic Institute), they were subsequently extensively promoted by a number of international fairground showmen including the original “King of Showmen”, Randall Williams. While the original meaning/reference of the term phantasmagoria (as visual apparition) may have been replaced by the term's use to describe an overstimulation of the senses, one with a possibly negative valence [hinting at sensory deception/disorientation; Lynn (2006), Tresch (2011)], there is also a sense that technology is involved in the realization (e.g., Adorno, 2005), be it of people, ghosts, or actors. This then links to the use of the term when describing Wagner's Gesamtkunstwerk (Daub, 2009; Joe and Gilman, 2010).

Given that Dr. Pepper' Ghost illusion and the phantasmagoria shows were explicitly promoted as scientific illusion, not reality (e.g., Barber, 1989, p. 78; Groth, 2007, p. 49; Gunning, 2007), it is interesting to return to consider the contemporary use of this optical trick, where the effect (and possibly also the intention) would appear to be to mystify audiences as to how exactly it is achieved, having the latter questioning what is “real” and what is not (e.g., see Ganz, 2012; Gingrich, 2016).

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Funding

CS was supported by the AHRC grant (AH/L007053/1) Rethinking the Senses.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The handling editor AN declared a past collaboration with the author.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^The patent (# 326), entitled “Improvements in Apparatus to be used in the Exhibition of Dramatic and other Like Performances”, was filed on February 5th, 1863.

2. ^Ghosts and skeletons perhaps not being expected to reveal themselves by the sound of their voice, nor the smell of their old bones (though see Ranasinghe et al., 2019, for one contemporary attempt to imagine/introduce the latter; and Gunning, 2007, p. 102–103, on ghosts and their various unisensory and multisensory manifestations).

3. ^The honorific title apparently given by the Institute itself (see Brooker, 2007, p. 190).

4. ^The latter contrasting with the sleight of hand tricks that had been the mainstay of the art of ledgerdemain previously (see Steinmeyer, 2003).

5. ^Benjamin (1999, p. 18) also considered the world's fair as a kind of phantasmagoria (Ogata, 2002).

6. ^Barber (1989, p. 84) also points to Nathaniel Hawthorne's frequent use of the term in his writings, citing the example of a character in The House of the Seven Gables (1851) who would “hang over Maule's well, and look at the constantly shifting phantasmagoria of figures produced by the agitation of the water over the mosaic work of colored pebbles at the bottom.” (Hawthorne, 1963, p. 142). A couple of decades later, Lewis Carroll released a book of poems entitled Phantasmagoria (see Carroll, 1869; Warner, 2006–2007).

7. ^Indeed, Barber (1989) notes how phantoms had occasionally been shown in lantern shows during the 17th and 18th Century, such as, for example, Huygens' device known as ‘the lantern of fright' (see van Nooten, 1972).

8. ^Here it is perhaps interesting to consider why the phantasmagoria was only ever a unisensory visual phenomenon. This may reflect nothing more than the ubiquitous dominance of the visual (e.g., Crary, 1992; Gunning, 2007; Hutmacher, 2019; Spence et al., 2020), and of the more rapid advance of technologies for controlling/reproducing visual and opposed to auditory/olfactory stimuli (see Spence et al., 2020). That said, there is a long history of phantom voices, stretching back to the ancient Greek oracles, as discussed by Steven Connor (2000) (see also Banks, 2001, on the notion of “ghost voices”). Under the appropriate conditions, such disembodied voices could be made to commune with real actors and/or religious figures. Why, one might ask, not also consider this as a kind of phantasmagoria?

9. ^It is interesting to note, in passing, how the other “King of Showmen”, the legendary P. T. Barnum (see Steinmeyer, 2003; Barnum, 2017), although being active on both sides of the Atlantic over the same period, rarely seems to have engaged in such visual conjuring. Barber (1989, p. 84) notes how: “In 1889, for instance, Frank Hoffman, a showman with the Barnum and Bailey Circus, presented “supernatural illusions and visions exhibiting a series of startling, theosophical delusions and ethereal phantoms by modern scientific means” in a “black tent” darkened to keep out light.” (see Barnum and Bailey show route book of the season of, 1889). Unfortunately, however, early commentators complained about the three pieces of glass he used being visible on stage, thus breaking the illusion (Posner, 2007, p. 200).

10. ^The Royal Polytechnic Institute finally closed its doors in September 1881 (Brooker, 2007; Weeden, 2008).

11. ^According to Weeden (2008, pp. 73–74): “Dircks certainly began the process. He presented a model of his ‘phantasmagoria' at the British Association for the Advancement of Science meeting in Leeds in 1858. He was, though, apparently disappointed when no theater manager expressed interest in his invention, but the design in its original form was impractical.”

12. ^Though Loew (2012, p. 88) notes how Pepper's Ghost is really a variation on an optical illusion first described by the Italian natural philosopher Giambattista della Porta in 1558 (see Pepper and Dircks, 1863; Porta, 2005, p. 340).

13. ^That being said, it is worth noting that the practicing magician fails to reveal a number of the secrets involved in the various illusions that he describes.

14. ^Meanwhile, another illusion, entitled “Ampitrite” involved the vertical reflection of a woman who would lie horizontally on a rotating table raised above the floor, once again set below the level of the stage (Hopkins, 2020, pp. 61–62). The latter arrangement would give the audience the visual impression that the actor was spinning in mid-air (see also Lano, 1957, for one subsequent example of this set-up being incorporated into a magic routine). Intriguingly, however, while Hopkins references the Royal Polytechnic Institute (Hopkins, 2020, pp. 7–8), he never mentions the Dr. Pepper's Illusion or Phantasmagoria ghost show by name (perhaps linked to the patent issues mentioned above).

15. ^It has been suggested that the presentation of Dr. Pepper's Ghost was probably what inspired the Lumière Brothers to exhibit their cinematography in England for the first time at the Royal Polytechnic Institute (Mannoni, 2000).

16. ^Though not always successfully (see Sutcliffe, 2005, p. 8).

17. ^Castle (1988, p. 40) writes: “Traveling motion-picture shows in rural England before 1914 often took the form of ghost-shows. The showman Randall Williams was among the first to exhibit moving pictures as part of his Ghost Show in the 1890s.”

18. ^Heard (2006, p. 230–231), notes the similarity between the subjects explored at the Polytechnic and Phantasmagoria presentations.

19. ^Relevant here, the first Kinetoscope peepshow was created in North America by Thomas Edison in 1894. In fact, by the end of 1896, films being shown as part of the program in almost every music hall across the land (Barnes, 1983, p. 177).

20. ^The northern industrial cities of Bradford and Leeds were important centers, alongside London, in the development of cinematography (Barnes, 1983).

21. ^Though credit for the original presentation in Bradford (on the evening of the Diamond Jubilee day (22nd June, 1897) goes to local film company (Messrs. R. J. Appleton and Co. of Bradford) and the Bradford Argus newspaper (see Barnes, 1983, p. 189). The film was shown in the town square to a crowd of 1,000 at midnight (after being developed and printed in a specially fitted carriage on the train on the way up).

22. ^Unfortunately, however, Randall Williams died unexpectedly in Grimsby, in November, 1898, after attending Hull Fair, thus cutting short his career (see “Death of Randall Williams. A noted showman, 1898”; Gashinski, 2011). Somewhat confusingly, one of his sons-in-law, a Richard Monti, took to presenting himself as Randall Williams and toured with “Professor Randall Williams” bioscope show' until 1916 when, apparently, it was abandoned in a field outside Silsden (Mellor, 1996). This observation relevant to the earlier point concerning the lack of physical relics relating to the phantasmagoria and bioscope shows.

23. ^Furthermore, the approach embodied by Dr. Pepper's Ghost was subsequently used when introducing special effects in film-making (not to mention appearing in head-up displays in fighter jets and cars, as well as teleprompters; Steinmeyer, 2003, p. 336; see also Loew, 2012).

24. ^Consistent with such a view it is worth noting the absence of mystics and magicians on the fairgrounds (this contrasting with the notion of the Gypsy fortune teller; Jones, 1986, p. 45; Okely, 1983; though see Frost, 2015).

References

Banks, J. (2001). Rorschach audio: ghost voices and perpetual creativity. Leonardo Music J. 11, 77–83. doi: 10.1162/09611210152780728

Barber, X. (1989). Phantasmagorical wonders: the magic lantern ghost show in Nineteenth Century America. Film Hist. 3, 73–86.

Barnes, J. (1983). The rise of the cinema in Great Britain: The beginnings of the cinema in England 1894-1901 (Vol. 2; Jubilee Year 1897). London, UK: Bishopsgate Press.

Barnum and Bailey show route book of the season of 1889. Barnum and sole owners of the Greatest Show on Earth 1889, Joe Meyer, P. T. p. 14.

Benjamin, W. (1999). The arcades project (trans. H. Eiland & K. McLaughlin). Harvard, IL: Belknap Press/Harvard University Press.

Brewster, D. (1832). Letters on Natural Magic: Addressed to Sir Walter Scott. London, UK: John Murray.

Brooker, J. (2007). The polytechnic ghost: Pepper's Ghost, metempsychosis and the magic lantern at the Royal Polytechnic Institution. Early Popular Visual Culture. 5, 189–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/17460650701433517. doi: 10.1080/17460650701433517

Burwick, F. (1990). Romantic drama: From optics to illusion. In S. Peterfruend (Ed.), Literature and science: Theory and practice. Boston: Northeastern University Press. p. 167–208.

Carlson, M. (2014). “Charles Dickens and the invention of the modern stage ghost,” in Theatre and ghosts, Luckhurst, M., and Moran, E. (Eds.). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 27–45. doi: 10.1057/9781137345073_2

Castle, T. (1988). Phantasmagoria: Spectral technology and the metaphorics of modern reverie. Critical Inquiry. 15, 26–61. doi: 10.1086/448473

Connor, S. (2000). Dumbstruck: A Cultural History of Ventriloquism. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198184331.001.0001

Crary, J. (1992). Techniques of the Observer: On Vision and Modernity in the Nineteenth Century. MIT Press: Cambridge, MA.

Daub, A. (2009). “Sonic dreamworlds: Benjamin, Adorno, and the phantasmagoria of the opera-house,” in A companion to the works of Walter Benjamin, Goebel, R. G. (Ed.). Rochester, NY: Camden House. p. 273–294.

Dickens, C. (1848). The Haunted Man and the Ghost's Bargain. A Fancy for Christmas Time. London, UK: Bradbury and Evans. doi: 10.1093/oseo/instance.00122012

Dircks, H. (1863). The ghost! As Produced in the Spectre Drama: Popularly Illustrating the Marvellous Optical Illusions Obtained by the Apparatus Called the Dircksian Phantasmagoria. London, UK: Spon.

Ganot, A. (1872). Natural History for General Readers [Ed. and trans. E. Atkinson]. London, UK: Longmans.

Ganz, J. (2012). How that Tupac hologram at Coachella worked. NPR, April 17th. Available online at: https://www.npr.org/sections/therecord/2012/04/17/150820261/how-that-tupac-hologram-at-coachella-worked?t=1655822946052 (accessed July 10, 2022).

Gashinski, P. (2011). “Wanted, a few useful people for the ghost business”: The story of Victorian showman Randall Williams. Atikokan, Ontario: Self-published.

Gingrich, O. (2016). Evoking presence through creative practice on Pepper's ghost displays. (PhD Thesis). Bournemouth University, Faculty of Media and Communication.

Groth, H. (2007). Reading Victorian illusions: Dickens's ‘Haunted Man' and Dr. Pepper's ‘Ghost'. Victorian Studies. 50, 43–65. doi: 10.2979/VIC.2007.50.1.43

Gunning, T. (2007). To scan a ghost: the ontology of mediated vision. Grey Room. 26, 94–127. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20442752. doi: 10.1162/grey.2007.1.26.94

Gunning, T. (2009). “The long and short of it: Centuries of projecting shadows from natural magic to the Avant-Garde,” in The art of projection, Douglas, S., and Eamon, C. (Eds.) Ostfildern, Germany: Hatje Cantz Verlag. p. 23–35.

Heard, M. (1996). Introduction. The true history of Pepper's Ghost. By John Henry Pepper. 1890. Facsimile ed. London, UK: Projection Box. p. I–VI

Heard, M. (2002). Giving up the Ghost. The Galloper. Available online at: http://fairgroundheritage.org.uk/learning/thefairgroundshow/givinguptheghost/ (accessed July 10, 2022).

Heard, M. (2008). Phantasmagoria: Spirit Visions, Metaphors, and Media into the Twenty-First Century. Hastings, UK: Projection Box.

Hecht, H. (1984). The history of projecting phantoms, ghosts and apparition's. New Magic Lantern J. 3, 2–6.

Hopkins, A. A. (2020). Magic: Stage Illusions, Special Effects and Trick Photography (with an introduction by H. R. Evans). New York, NY: Dover Publications.

Hutmacher, F. (2019). Why is there so much more research on vision than on any other sensory modality? Front. Psychol. 10, 2246. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02246

Jackson, L. (2019). Palaces of Pleasure: From Music Halls to the Seaside to Football, How the Victorians Invented Mass Entertainment. London, UK: Yale University Press. doi: 10.12987/9780300245097

Joe, J., and Gilman, S. L. (Eds.). (2010). Wagner & cinema. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

John, B. (2010). “Gesamtkunstwerk,” in See this sound: Audiovisuology. An interdisciplinary survey of audiovisual culture, Daniels, D., Naumann, S., and Thoben, J. (Eds.). Köln: Verlag der Buchhandlung Walter König. p. 141–150.

Jones, E. A. (1986). Yorkshire Gypsy Fairs, Customs & Caravans: 1885–1985. Beverley, East Yorkshire: Hutton Press.

Jütte, R. (2005). A History of the Senses: From Antiquity to Cyberspace (trans. James Lynn) (Chapter 2 – Conceptions: The Sensorium). Cambridge, UK: Polity Press. p. 20–53.

Kasson, J. F. (1978). Amusing the Million: Coney Island at the Turn of the Century. New York, NY: Hill & Wang.

Kennedy, G. D. (2012). Coachella 2012: Tupac 'Responds' to his Reincarnation. The Los Angeles Times.

Lynn, S. (2006). Fantasy lands and kinesthetic thrills. Senses Society. 1, 293–309. doi: 10.2752/174589206778476289

Mannoni, L. (2000). The Great Art of Light and Shadow. Archaeology of the cinema [Trans. R Crangle]. Exeter: University of Exeter Press.

Mellor, G. J. (1996). Movie Makers and Picture Palaces: A Century of Cinema in Yorkshire 1896-1996. Bradford, West Yorkshire: Bradford Libraries.

Muelrath, F. (2018). “Phantasmagoria and the Trump Opera,” in Critical Theory and Authoritarian Populism, Morelock, J. (Ed.). London, UK: University of Westminster Press. p. 229–247.

Ndalianis, A. (2004). Neo-Baroque Aesthetics and Contemporary Entertainment. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. doi: 10.7551/mitpress/4912.001.0001

Ogata, A. F. (2002). Viewing souvenirs: peepshows and the international expositions. J. Design Hist. 15, 69–82. doi: 10.1093/jdh/15.2.69

Okely, J. (1983). Traveller gypsies. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511621789

Paulin, S. D. (2000). “Richard Wagner and the fantasy of cinematic unity: The idea of the Gesamtkunstwerk in the history and theory of film music,” in Music and cinema, Buhler, J., Flinn, C., and Neumeyer, D. (Eds.). Middletown, CO: Wesleyan University Press. p. 58–84.

Pepper, J., and Dircks, H. (1863). The Patent Ghost. Available online at: https://prismic-io.s3.amazonaws.com/add2020/463b8f29-4573-41a6-96e6-583c13b1f63e_The-Patent-Ghost.pdf (accessed July10, 2022).

Pepper, J. H. (1890). The True History of the Ghost: And all About Metempsychosis. London, UK: Cassell & Company.

Pérez-Gómez, A. (2016). Attunement: Architectural Meaning After the Crisis of Modern Science. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. doi: 10.7551/mitpress/10703.001.0001

Podestà, S., and Addis, M. (2007). “Converging industries through experience,” in Carù, A., and Cova, B. (Eds.). Consuming Experience. London, UK: Routledge. p. 139–153.

Porta, J. B. (2005). Natural Magick (1658). Sioux Falls, SD: NuVision Publications. doi: 10.5479/sil.82926.39088002126779

Posner, D. N. (2007). Spectres on the New York stage: The (Pepper's) Ghost craze of 1863. in Representations of death in nineteenth-century US writing and culture, Frank, L. E. (Ed.). Aldershot: Ashgate. p. 189–205. doi: 10.4324/9781351150248-13

Price, L. (2015). The Modi Effect: Inside Narendra Modi's Campaign to Transform India. Quercus Books.

Pursell, C. (2013). Fun factories: inventing American amusement parks. Icon. 19, 75–99. Available online at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/i23785838

Quigley, M. Jr. (1948). Magic Shadows: The Story of the Origin of Motion Pictures. Georgetown: Georgetown University Press.

Ranasinghe, N., Koh, K. C. R., Tram, N. T. N., Liangkun, Y., Shamaiah, K., Choo, S. G., et al. (2019). Tainted: an olfaction-enhanced game narrative for smelling virtual ghosts. Int. J. Hum. Comput. 125, 7–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhcs.2018.11.011

Register, W. (2001). The Kid of Coney Island: Fred Thompson and the Rise of American Amusements. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

“Reynaud's Optical Theater”. (1892). Scientific American. 67, 215. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican10011892-215

Robert-Houdin, J. E. (1975). The Secrets of Stage Conjuring Travelling Shows and Roundabouts. Blandford: Oakwood Press.

Robertson, E-G. (1831). Mémoires: Récréatfis, scientifiques et anecdotiques d'un physician-aéronaute, Vol. 1 [Memories: Recreative, scientific, and anecdotal of a doctor-pilot]. Paris: Chez l'auteur et à? la Librairie de Wurtz. Available online at: https://www.loc.gov/item/32006148/

Schwarz, W. M. (1992). Kino und Kinos in Wien: Eine Entwicklungsgeschichte bis 1934 [Cinema and cinemas in Vienna: A history of development until 1934]. Vienna: Tuna & Kant.

Sellman, A. (1975). Travelling shows and roundabouts (Locomotion Papers 84). Snape Maltings: Oakwood Press.

Slessor, C. (2018). Let them eat cake: Urbain Dubois. Architectural Review. Available online at: https://www.architectural-review.com/essays/let-them-eat-cake-urbain-dubois.

Spence, C. (2022). From the fairground sensorium to the digitalization of bodily entertainment: Commercializing multisensory entertainments involving the bodily senses. Senses Society. 17, 153–169. doi: 10.1080/17458927.2022.2066434

Spence, C., Youssef, J., and Kuhn, G. (2020). Magic on the menu: where are all the magical food and beverage experiences? Foods. 9, 257. doi: 10.3390/foods9030257

Steinbock, E. (2019). “Shimmering phantasmagoria: Trans/Cinema/Aesthetics in an age of technological reproducibility,” in Shimmering images: Trans cinema, embodiment, and the aesthetics of change, Steinbock E. (Ed.). Duke University Press. p. 21–60. Available online at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv125jq9c.6

Steinmeyer, J. (2003). Hiding the Elephant: How Magicians Invented the Impossible. London, UK: Arrow Books.

Sutcliffe, A. (2005). The ghost illusion on the Birmingham stage, 1863–1900. Part 1: 1863–7. N. Magic Lantern J. 10, 7–11.

Taylor, J. T. (1863). ‘Notes' harmonious and discordant, on various subjects. Br. J. Photograp. 10, 306–308.

‘The magic lantern: How to buy and how to use it and how to raise a ghost (“by a mere phantom”)'. (1880). London, UK: Houlston.

‘The fairground bioscope shows'. (n.d.). National Fairground Circus Archive. Sheffield: The University of Sheffield. Available online at: https://www.sheffield.ac.uk/nfca/researchandarticles/bioscopeshows (accessed July 10 2022).

Toulmin, V. (1998). Randall Williams - King of Showmen: From Ghost Show to Bioscope. Projection Box.

Tresch, J. (2011). The prophet and the pendulum: sensational science and audiovisual phantasmagoria around 1848. Grey Room. 43, 16–41. doi: 10.1162/GREY_a_00030

van Nooten, S. I. (1972). Contributions of Dutchmen in the beginnings of film technology. J. Soc. Motion Pict. Eng. 81, 119. doi: 10.5594/J05657

Velasco, C., and Obrist, M. (2020). Multisensory Experiences: Where the Senses Meet Technology. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/oso/9780198849629.001.0001

Warner, M. (2006–2007). Darkness Visible: The View From the shadows. Cabinet, 24 (Winter). Available online at: https://www.cabinetmagazine.org/issues/24/warner.php (accessed July 10, 2022).

Weeden, B. (2008). The Education of the Eye: History of the Royal Polytechnic Institution 1838 – 1881. Cambridge, UK: Granta Editions. doi: 10.2307/j.ctv6zd979

Keywords: phantasmagoria, Dr. Pepper's Ghost, entertainment, fairground, Gesamtkunstwerk, illusion

Citation: Spence C (2022) The phantasmagoria: From ghostly apparitions to multisensory fairground entertainment. Front. Commun. 7:894078. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2022.894078

Received: 15 March 2022; Accepted: 28 June 2022;

Published: 27 July 2022.

Edited by:

Anton Nijholt, University of Twente, NetherlandsReviewed by:

Stephan Packard, University of Cologne, GermanyOliver Gingrich, Bournemouth University, United Kingdom

Lik Hang Lee, Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology, South Korea

Copyright © 2022 Spence. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Charles Spence, Y2hhcmxlcy5zcGVuY2VAcHN5Lm94LmFjLnVr

†ORCID: Charles Spence https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2111-072X

Charles Spence

Charles Spence