- Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, North South University, Dhaka, Bangladesh

Risk communication during COVID-19 is essential to have support, but it is challenging in developing countries due to a lack of communication setup. It is more difficult for the low-income, marginal communities, and specifically, women in developing countries. To understand this, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic, we conducted a qualitative study among N = 37 women (urban 20, rural = 17) across Bangladesh that presents the risk communication factors related to social and financial challenges. It reveals that the majority of the urban communities lack communication with local authorities, where urban low-income communities are the worst sufferers. Due to that, the majority of the urban participants could not get financial support, whereas the rural participants received such support for having communications with local authorities during the pandemic. However, access to technology helped some participants share and receive pandemic-related information about risk communication, and the adoption of financial technology helped to get emergency financial support through risk communication. Moreover, this work is expected to understand the role of risk communication during the COVID-19 pandemic among women in Bangladesh.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought social and economic impact on global communities and impacted the health sector (Jadoo, 2020). Risk communication helps at this point where it refers to the entire communication framework that engages the authorities, policymakers, implementors, scientists, media, and general people in the process of knowledge sharing to address the problem with clarity (Smillie and Blissett, 2010). However, low-resource countries were mainly affected by the pandemic, where low-income and marginal communities faced harsher challenges due to a lack of communication setup (Hamzah et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2020). Among them, women have been impacted in developing countries worldwide, legging a scope for deeper investigation (Van Barneveld et al., 2020). This case study looks at urban and rural women in Bangladesh in terms of their challenges and opportunities, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic around risk communication.

The importance of risk communication was evident during the COVID-19 pandemic. Risk communication is considered necessary where a rich set of guidelines define how to avoid challenging situations as defined by various guidelines (Johnson and Angell, 1998; The Royal Society, 2000; Smillie and Blissett, 2010). The World Health Organization has presented guidelines for risk communication and community engagement (RCCE) (World Health Organization, 2021). Risk communication was essential for marginal and hard-to-reach communities as seen in many developing regions and developed countries (Mottaleb et al., 2020; Van Barneveld et al., 2020). However, there was the presence of misinformation, an overflow of information referred to as infodemic, and the spread of rumors in cases where risk communication was not clear (Islam et al., 2020; Reddy and Gupta, 2020; Solomon et al., 2020; Shahi et al., 2021).

There was clear evidence in scholarly research that top-down risk communication has taken place where authority-imposed decision-making was followed in many countries from developing countries in Africa and Asia (Ahmed et al., 2020a,b; Adebisi et al., 2021; Shammi et al., 2021). The studies suggest that the top-down risk communication process often fails to include low-income and marginalized populations. Moreover, research shows that the communication process is not trusted by the general population and the presence of other challenges, as shown in a study concentrating on African countries (Adebisi et al., 2021). On the other hand, there has been a limited number of studies showing bottom-up approaches for risk communication where communities have engaged—as seen among the migrant workers of Singapore (Tam et al., 2021), among the state-level community management in Kerala, India (Rahim and Chacko, 2020).

As a resource-constrained country with a large population base, Bangladesh initiated risk communication during the pandemic by declaring and implementing an authority-imposed lockdown (Dhaka Tribune, 2022). But this communication was top-down, and some marginal communities failed to comprehend clear instructions (Ahmed et al., 2020a,b). For example, the Ready-Made Garments (RMG) workers were unsure about joining their work, showing a lack of clear risk communication with directions (Ahmed et al., 2020a,b). However, a lack of study contrasts the risk communication challenges across urban and rural communities in a resource-constrained country setup. Moreover, there is a requirement to look at the possible role of technology in risk communication.

In another aspect, access to technology helps in risk communication during emergencies, but there have been sociocultural barriers where women have been underrepresented in technology usage as shown in recent scholarly studies where patriarchal challenges have impacted technology access (Ahmed et al., 2016; Sambasivan et al., 2018, 2019; Sultana et al., 2018). Access to technology also opens up dimensions for adopting fintech, where it has been shown that the recent pandemic has brought opportunities and emergency support through using financial technology, allowing contactless transactions (Jahangir Rony et al., 2021). This work similarly aims to focus on an in-the-moment study during this COVID-19 pandemic contrasting urban and rural communities in terms of effective risk management followed by the lockdown period in Bangladesh, considering risk communication opportunities where technology can be a vehicle.

We have qualitatively studied N = 37 (urban 20, rural = 17) women through 7 different focus group discussions (FGD) in urban and rural areas setup covering three different divisions of Bangladesh. The communities in the focus groups were different. The study has revealed the communities' variety of income and education levels, where we have found that around 49% of the participants have faced financial difficulties during the COVID-19 pandemic. The rural communities were connected to the local governance, leaders, and NGOs and received financial support, more or less. Alternatively, the majority of the urban participants were disconnected from the local authority and did not get and seek help from anywhere due to social prejudice. Also, the low-income communities in urban areas suffered the most as they were digitally disconnected and could not receive information regarding COVID. Those who have technology access can connect with the updates of media, share and receive COVID-19-related information about risk communication, and fintech adoption further helps obtain financial support through risk communication. Moreover, the study findings show that technology usage in risk communication can be supportive for communities during difficult times.

Study Method

Overview and Participant Recruitment

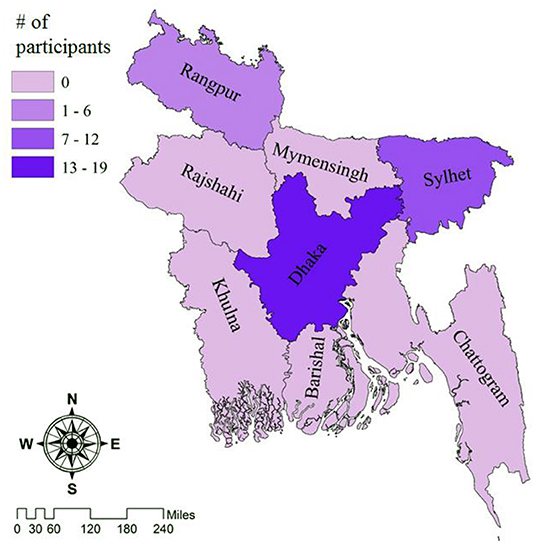

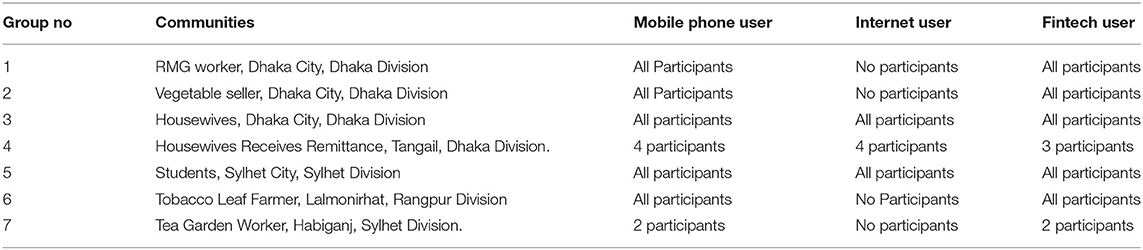

This study was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic in Bangladesh, and we considered the risk communication challenges and opportunities of marginal communities. This was a qualitative study on N = 37 participants in Bangladesh's urban and rural setup ranging from Dhaka, Sylhet, and Rangpur divisions (Figure 1) from February 2021 to December 2021. We conducted seven focus group discussions (FGD) in the native Bengali language in a semi-structured format. We recruited the participants through key informants in such areas who are locally trusted and have communications with local communities. These key informants connected with us through known contacts. First, we recruited three key informants from three separate divisions. Then we discussed the study objectives with them, and then they explored and helped recruit and connect the participants to particular locations. We present the participants' details in Table 1. During the discussion on the pandemic period, we ensured to follow strict safety protocols—ensuring social distance, providing masks and sanitizers as defined by the Ministry of Health and World Health Organization (Ministry of Health Family Welfare, 2021; World Health Organization, 2021).

Discussion Method and Study Moderation

We prioritized participants' preferences for the discussion as the COVID-19 pandemic is ongoing. The participants of consideration were working during the study period and preferred in-person focus group discussion sessions in places of their preference which took place in the participants' residents in most cases. Each discussion took nearly 60–180 min on average, and around 10 h of discussions were conducted. The discussions were participatory, and we audio-recorded each discussion with multiple recording devices to reduce missing data with participants' consent. Five researchers were present in each discussion, one was leading the discussions, and the rest of the researchers took notes and helped with follow-up questions. The generic format remained to seek stories and experiences around topics with follow-up notes based on person-specific details.

Qualitative Content Analysis

All the discussions conducted in the Bengali language were transcribed and translated into English for coding analysis. The thematic content analysis was performed using Atlas.Ti software (Atlas.ti, 2022). The content analysis started after the first discussion of this study because it provided better context-based understanding, which was also mutually apprised with the relevant data (Glaser and Anselm, 2017). During the analysis phase, researchers jointly participated in initial coding from transcriptions. The inductive content analysis method (Braun and Clarke, 2006; Elo and Kyngas, 2008) was followed to identify the key themes from participants' discussions, create affinity diagrams for groping, and generate major categories. Through discussion among the authors regarding the codebook, the authors generated the key themes of the findings.

Study Incentive and Ethics

The Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved the study, and each participant provided verbal and signed consent. Study participants were explained the study before the discussion session; each participant received food and a gift equivalent to BDT 1000.

Findings

The findings consist of an overview of the participants in the communities, reflections on financial and social challenges along with technology-initiated opportunities as presented in the following subsections.

Overview of the Communities

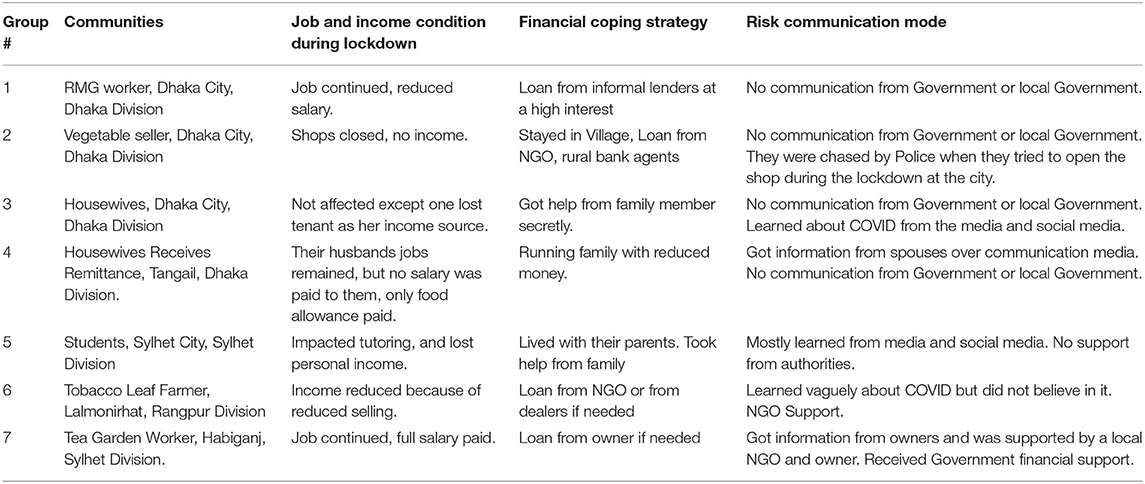

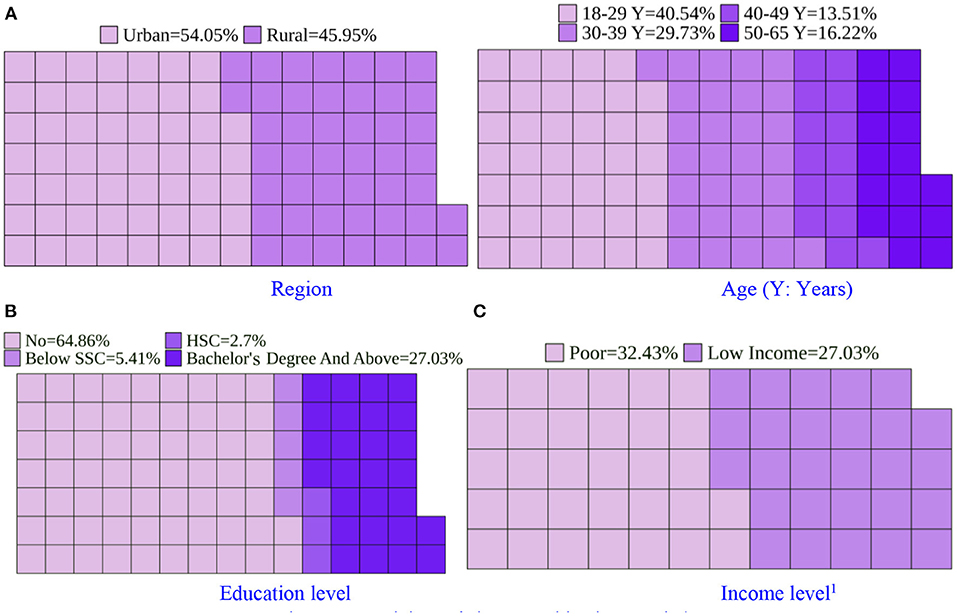

In this study, the participants were from different socioeconomic backgrounds where 54.05% of the participants were from urban areas and 45.95% of the participants were from rural areas (Figure 2A). Most participants were young and were aged below 40 years (Figure 2A). In addition, 64.86% of the participants did not have any education while only 27.03% of the participants had a Bachelor's degree and above (Figure 2B). Exploring the participants' income levels based on the Pew Research Center's classification (Kochhar, 2015), we found that 32.43% of the participants were poor while only 27.03% of the participants had a low income (Figure 2C).

Figure 2. Participants' demographic characteristics. (A) Region and Age (Y: Years). (B) Education level. (C) Income level. 1Nine participants (24.32%) were housewives and 6 participants (16.22%) were students for whom income level classification was not applicable due to not having any personal income.

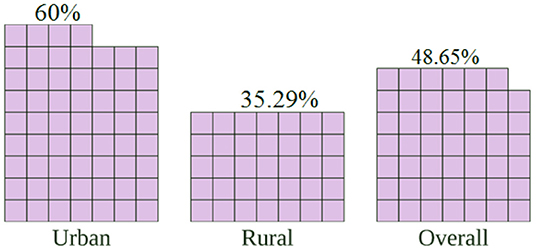

During the pandemic, people faced barriers in different cases. Among the participants of our study, 48.65% faced a negative impact on finance (Figure 3). In addition, we found that though 60% of the participants in urban areas faced a negative impact, this percentage was lower in the case of rural participants where 35.29% faced a negative impact on finance.

Figure 3. Percentage of urban, rural, and all participants (overall) who faced a negative impact on finance.

Communities Faced Financial Difficulties and Social Challenges

Financial Difficulties

The communities have mostly suffered from the COVID-19-imposed lockdown that resulted in financial difficulties; the majority were losing or getting reduced wages regardless of their living area. Their sufferings during the pandemic went beyond the health problems shared by the study participants, which were impacted by minimal risk communication. Most participants struggled with financial difficulties; they did not receive clear directions on seeking financial assistance as COVID affected their monthly income source. We found that mostly the urban participants were disconnected from local authorities. On the other hand, the rural participants received little assistance from local authorities and nearby supporting Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs).

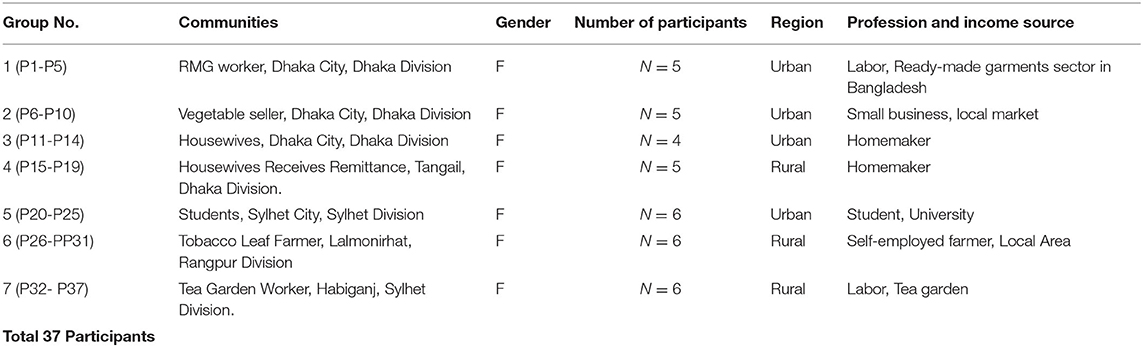

Table 2 summarizes the participants' job conditions, income, and coping strategies during the pandemic. It shows that three communities (Groups 2, 4, and 5) lost their monthly income and did not receive financial support from any authority. The communities were the vegetable sellers from Dhaka city, who usually earn daily on selling vegetables in the local market, and a student group from the Sylhet city who used to earn pocket money from tutoring. Due to the pandemic, they could not move to their workplaces, which impacted their earnings. Accordingly, the rural community consisted of homemakers depending on the foreign remittance of their husbands. During the pandemic, their husbands did not receive their salaries, resulting in the homemakers not receiving money and struggling hard to survive. At this point, a participant, P15, shared how her husband working in Singapore ate less to save money and shared that amount with his family.

On the other hand, the Ready-Made Garments (RMG) workers (Group 1) received partial payment and could not earn the overtime allowance during the same period. The urban homemakers had steady incomes in families except for one who was a widow and depended on her income from house rents which she lost during the same period. The tobacco farmers and tea garden workers received their regular income. The tea garden workers (Group 7) working in the formal earning sector received monthly payments. Also, the tobacco leaf farmers' (Group 6) income had been reduced because of the reduced selling of their crops at the local market, which comes with financial difficulties, but they received support from local NGOs.

The financial difficulties were similar among communities as the flow of income was hampered. The major challenge was to continue surviving during that time. The living cost varied for urban and rural areas, and at this point, urban communities suffered to pay the home rent when communities lost their regular income. For example, the vegetable sellers from Dhaka lived in their respective villages to minimize their living costs during the lockdown time. On the other hand, the rural communities lived with their residents and mainly were concerned with food costs because the communities were closely connected in rural areas. For seeking financial support, the knowledge regarding this varied among participants where we found social prejudice behind seeking help during difficult times. For example, the urban participants were worried about the surrounding environment as the homemaker participant from the Dhaka division did not want to share her financial difficulties. Similarly, a vegetable seller did not want her house owner to know about her financial struggle during the pandemic, as participant P7 shared as follows:

“We feel ashamed when we cannot give house rent. Sometimes we cook chicken, then our house owner comes to our door and says you eat good food, but you don't give me the house rent. It is better to eat rice with salt rather than this kind of word.”- P7, Female, Age 50-65, Vegetable Seller, Urban, Dhaka.

However, the perception differed in rural setups. The community supported each other financially during difficult times. The study also showed the availability of financial services varied in urban and rural scenarios. The urban participants were not well-informed about formal financial services to receive loans and borrowed from informal lenders with extremely high-interest rates. On the other hand, the rural participants were closely connected with the financial system supported by Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) or agent banking that served at their doors and were supported by those communities in need. Also, as the participants shared, we found that the rural communities, such as tobacco leaf farmers and tea garden workers, were financially supported by their owners in case of emergencies during the pandemic.

Social Challenges

The social challenges were prominent for certain participants of a few communities where a summary of the major social challenges faced is presented in Table 3. The challenges varied based on the economic conditions of the communities that were intense in the urban regions as shared by the participants.

The social struggles were unique among various communities. An urban housewife participant, P14, a widowed housewife relying on house rent, entirely lost her income during the lockdown when her tenants left the city and discontinued their contract. While the participant was struggling monetarily, she could not bear to ask anyone for help. She was living with her two small children, from whom she also tried to hide her financial struggle. Accordingly, the urban vegetable sellers were concerned about others and what others might think about them if they asked for help.

Similarly, the urban student group did not face any social barrier except for personal discomfort in seeking support from parents. However, the urban RMG workers' social struggles were slightly different as they were concerned about their job security since a few previous RMG workers lost their jobs when they had COVID symptoms mentioned by the RMG workers. Also, there was a constant fear of staying healthy among them while the work continued throughout the lockdown period.

The rural communities socially struggled differently while more concerned about family members. As housewives from rural areas, the participants shared about their spouses working abroad as laborers who were not earning money during the lockdown situation. The housewives and families depending on their husbands' remittance struggled during the pandemic while their husbands shared as little as they could be saving money from their food allowances. The struggle was present, and so was the empathy among each other. However, the housewives did not ask for help from others as people around them might know their spouses have no income abroad. A rural participant, P17, shared her financial struggle as:

“He went there and started working at the construction site. During coronavirus, he had no work and no income there. He was just sitting idle there. The owner paid the food cost only. He doesn't say anything negative to me, because we might get tense. Now he can send money once every two months. If he sends money every month, he will face difficulties there.”- P17, Female, Age 30-39, Remittance Family, Rural, Tangail.

Similarly, the participants from tea garden workers remained secluded by the authorities in their workplace during the lockdown. The social barriers shared by these participants covered their concerns about family members who were living away from the tea garden. The problems were more around their worries about others. It must be noted that the community support was more substantial in rural regions compared to the urban participants.

Risk Communication

We found a clear difference in risk communication between communities through this study. The rural participants were connected to family members, local leaders, NGOs, and local government authorities. The participants, having husbands working abroad shared that they received clear directions and guidelines from their workplaces abroad and shared them with their wives through phone calls. The other rural communities received financial and social support by communicating with local NGOs or leaders. We also found that the rural communities also maintained strict rules and regulations regarding staying locked at home, as shared by the participants. One rural participant shared how a local youth would monitor local activities to ensure everyone remains at home and are safe. In this way, many of these participants were ahead in learning about the possible spread of COVID and safety measures before the central directions by the government authorities. The majority of the urban participants had access online, were connected to the media, and received recommendations and messages regarding the COVID situation and support without being connected to any local authorities or leaders. The low-income communities had limited access to online media, and they struggled to get information and COVID situation and support. For example, an urban participant P8 shared how she was chased by Police when she was trying to sell vegetables during the authority-imposed lockdown—she tried to continue her operations being in desperate need of money. The incidents show a lack of clear communication about the risk of selling products during the lockdown among urban participants.

“During Corona, we cannot do the business well. We fled as soon as we saw the police coming to us. They shouted at us extremely. Sometimes they kicked the goods crate. We cannot do anything. We are weak.”- P8, Female, Age 30-39, Vegetable Seller, Urban, Dhaka.

Role of Technology During COVID-19 Pandemic

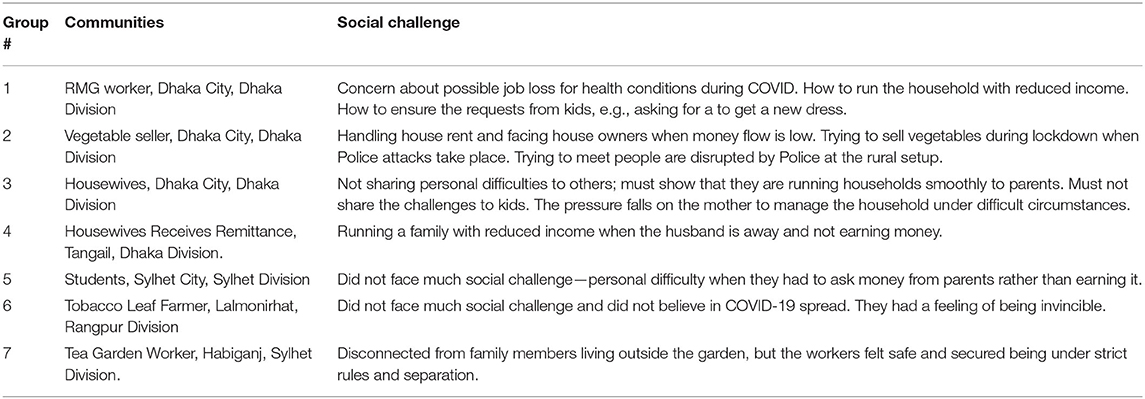

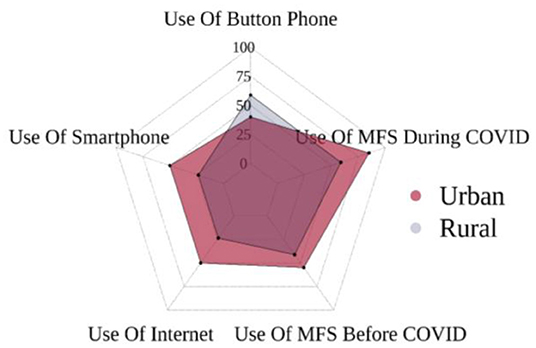

The technology worked as a vehicle for risk communication for a few communities. The technology usage and access to the internet varied among the participant groups. In Figure 4, we have seen that the participants from the urban area had higher access to smartphones and the internet while the participants from the rural area had more increased access to button phones. Accordingly, fintech worked as a channel of financial support during the COVID pandemic. We found that though the fintech or MFS (mobile financial service) usage was lower among the rural areas' participants, more than 75% of the urban and rural areas used MFS during the pandemic. We have summarized the communities' phone, internet, and mobile-based fintech usage in Table 4. Access to technology was visible among communities with education and better economic stability.

Figure 4. Difference between the urban and rural participants in terms of percentage of participants using button phone, smartphone, internet, mobile financial service (MFS) before COVID, and MFS during COVID.

The communities having access to the internet and familiarity with technology, e.g., the student group from urban areas and the housewives of urban and rural areas, were able to share and receive pandemic-related information about risk communication. In contrast, the majority of the communities from rural areas could not do that as they lacked online access. Also, the low-income and low-literate urban communities faced the similar situation as the rural communities. Some of the urban housewife participants shared getting lots of information, and one referred to feeling overloaded with all the information. The communities with basic digital connectivity, working under a structured working environment, e.g., RMG workers, received pandemic-related information from factory owners to measure risk communication unlike previous scholarly articles referring to confusion among RMG workers (Ahmed et al., 2020a,b). Being minimally exposed to digital content, these communities did not share about feeling burdened with information. The participants who were disconnected digitally relied on secondary information. Some participants shared being invincible during the pandemic, which is a misconception that could place them at risk.

As the access to technology helped in risk communication, at this point, the fintech option helped many participants to get financial support through contacts. We found the role of fintech prominent during the pandemic as it offered simple cashless transaction options using mobile phones through MFS (mobile financial systems). An urban housewife received cash support from a family member living in a different city using MFS. The garment workers and foreign remittance payments switched to fintech during the pandemic, and two participants received government support during the pandemic through MFS. An RMG worker, P2, shares her experience of MFS as follows:

“Our monthly salary was paid through bkash. So we have to use baksh. During the lockdown, those who didn't have bkash, they opened an account. Because they didn't make hand-to-hand transactions. Send money in bkash. Whatever they sent it was through bkash. They didn't give money face to face.”- P2, Female, Age 18-29, RMG Worker, Urban, Dhaka.

Discussion and Conclusion

In this study, we have explored N = 37 women participants from urban and rural areas of three divisions in Bangladesh to understand the risk communication during the COVID-19 pandemic through the financial and social challenges they have faced. The findings of this study show the financial and social challenges of the communities were common and varied among communities and possible technology opportunities helped regarding risk communication.

In this study, the majority of the rural communities benefited from the closely connected structure where local governance, leaders, and NGOs were contact points for risk communication. Also, the empathy among the communities living in rural areas was able to deal with the pandemic by helping each other compared to the participants living in urban areas. Also, some communities were disconnected and struggled with risk communication and guidance about where to seek possible support. Community-oriented support in rural areas is similar to existing successful risk communication efforts shared in scholarly work (Adebisi et al., 2021; Tam et al., 2021). There was also successful community engagement where bottom-up communication took place in Kerala, Vietnam, and Singapore, covering developing and developed countries (Adebisi et al., 2021; Tam et al., 2021; Thanh, 2021). This community engagement allows trusted communication, including unheard voices toward the top hierarchy, and can effectively manage risk in a situation such as a pandemic, as suggested by the WHO (World Health Organization, 2021). Resource-limited regions can significantly benefit from adequate risk communication at the community level. According to existing literature and findings, incorporating community models in the urban areas, particularly in areas where low-income communities reside, would better-manage difficult situations. The community-centered risk management can be incorporated into future policies for the country's disaster and risk management, considering the success stories.

Technology has been an enabler in risk communication. It helped a majority of the urban participants and a few rural participants but many remained digitally disconnected. Technology access points designed around the communities to disseminate and share information can open up ways for risk communication in Bangladesh, considering the broad mobile phone penetration in the country (Alam et al., 2019; BTCL, 2022). On the other hand, there are some limitations to excessive technology usage. For example, sharing misinformation, the proliferation of rumors, and a term used as infodemic refers to the flooding of information spreading fast based on technology platforms (Islam et al., 2020; Reddy and Gupta, 2020; Solomon et al., 2020; Shahi et al., 2021). However, the benefits of technology offering resources are expected to add value to the communities. The technology access points must ensure propagation and sharing of information from trusted sources through verification and awareness generation against the existing phenomena. Becoming familiar with technology reduces the existing digital divide as the lack of familiarity is a significant barrier to technology access for women (Sambasivan et al., 2019). Access to technology opens up opportunities in accessing fintech that can be an enabler in empowering women, particularly during the ongoing pandemic, as shown in the existing scholarly work (Jahangir Rony et al., 2021). However, if the technology is not carefully designed, the design may impose patriarchal and social practices that hamper women's technology access (Mustafa et al., 2019).

This work exploring the communities qualitatively shows the challenges and opportunities for women in Bangladesh in terms of risk communication. The study shows that the low-income communities in urban areas are neglected compared to the rural communities showing the closer connection of local authorities and leadership in rural setups that help in emergencies. It shows the requirement to enhance current risk communication strategies in urban areas. The study findings can design and define policies that are supportive for communities during difficult times.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary materials, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by IRB (2020/OR-NSU/IRB/1201), North South University. The researchers provided written informed consent to the participants to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

NA worked on major paper writing. RR worked on reframing and updating the paper. ASi worked on formalizing the findings. MA worked on visual representation. All of the researchers are involved in field research, analysis and paper writing, and modification. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This research was funded by the Gates Foundation and supported by North South University Human Computer Interaction (NSUHCI) and Design Inclusion and Access Lab (DIAL) of North South University, Bangladesh Grant No. INV_005970.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adebisi, Y. A., Rabe, A., and Lucero-Prisno, D. E. III. (2021). Risk communication and community engagement strategies for COVID-19 in 13 African countries. Health Promot. Perspect. 11, 137–147. doi: 10.34172/hpp.2021.18

Ahmed, N., Rony, R. J., and Zaman, K. T. (2020a). Design thinking around Covid-19: focusing on the garment workers of Bangladesh. Interactions 27, 10–11. doi: 10.1145/3406034

Ahmed, N., Rony, R. J., and Zaman, K. T. (2020b). Social distancing challenges for marginal communities during COVID-19 pandemic in Bangladesh. J. Biomed. Anal. 3, 5–14. doi: 10.30577/jba.v3i2.45

Ahmed, S. I., Ahmed, N., Hussain, F., and Kumar, N. (2016). “Computing beyond gender-imposed limits,” in Proceedings of the Second Workshop on Computing within Limits, 1–7. doi: 10.1145/2926676.2926681

Alam, G. M., Alam, K., Mushtaq, S., Khatun, M. N., and Mamun, M. A. K. (2019). Influence of socio-demographic factors on mobile phone adoption in rural Bangladesh: policy implications. Inform. Dev. 35, 739–748. doi: 10.1177/0266666918792040

Atlas.ti (2022). Available online at: https://atlasti.com (accessed February, 2022)

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

BTCL (2022). Bangladesh Telecommunications Company Limited. Available online at: http://www.btcl.gov.bd/ (accessed February 4, 2022).

Dhaka Tribune (2022). Coronavirus: Bangladesh Declares Public Holiday From March 26 to April 4. Available online at: https://archive.dhakatribune.com/bangladesh/2020/03/23/govt-offices-to-remain-closed-till-april-4 (accessed February 2, 2022).

Elo, S., and Kyngas, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. J. Adv. Nurs. 62, 107–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

Glaser, B. G., and Anselm, L. S. (2017). Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203793206

Hamzah, F. B., Lau, C., Nazri, H., Ligot, D. V., Lee, G., Tan, C. L., et al. (2020). CoronaTracker: worldwide COVID-19 outbreak data analysis and prediction. Bull. World Health Organ. 1, 1–32. doi: 10.2471/BLT.20.255695

Islam, A. N., Laato, S., Talukder, S., and Sutinen, E. (2020). Misinformation sharing and social media fatigue during COVID-19: An affordance and cognitive load perspective. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 159, 120201. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2020.120201

Jadoo, S. A. A. (2020). COVID-19 pandemic is a worldwide typical biopsychosocial crisis. J. Ideas Health 3, 152–154. doi: 10.47108/jidhealth.Vol3.Iss2.58

Jahangir Rony, R., Shabnam Khan, S., Sinha, A., Saha, A., and Ahmed, N. (2021). “COVID has made Everyone Digital and Digitally Independent”: Understanding Working Women's DFS and Technol*ogy Adoption during COVID Pandemic in Bangladesh,” in Asian CHI Symposium 2021, 202–209. doi: 10.1145/3429360.3468212

Johnson, T., and Angell, M. (1998). Improving public understanding guidelines for communicating emerging science on nutrition, food safety, and health. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 90, 194–199. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.3.194

Kochhar, R. (2015). “A Global Middle Class Is More Promise than Reality: From 2001 to 2011, Nearly 700 Million Step Out of Poverty, but Most Only Barely”. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center.

Ministry of Health Family Welfare (2021). Available online at: http://www.mohfw.gov.bd/ (accessed March 7, 2021).

Mottaleb, K. A., Mainuddin, M., and Sonobe, T. (2020). COVID-19 induced economic loss and ensuring food security for vulnerable groups: policy implications from Bangladesh. PLoS ONE 15, e0240709. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0240709

Mustafa, M., Mazhar, N., Asghar, A., Usmani, M. Z., Razaq, L., and Anderson, R. (2019). “Digital financial needs of micro-entrepreneur women in Pakistan: is mobile money the answer?,” in Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1–12. doi: 10.1145/3290605.3300490

Rahim, A. A., and Chacko, T. V. (2020). Replicating the Kerala state's successful COVID-19 containment model: insights on what worked. Indian J. Commun. Med. 45, 261. doi: 10.4103/ijcm.IJCM_598_20

Reddy, B. V., and Gupta, A. (2020). Importance of effective communication during COVID-19 infodemic. J. Family Med. Primary Care 9, 3793. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_719_20

Sambasivan, N., Batool, A., Ahmed, N., Matthews, T., Thomas, K., Gaytán-Lugo, L. S., et al. (2019). “They Don't Leave Us Alone Anywhere We Go' gender and digital abuse in South Asia,” in Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1–14. doi: 10.1145/3290605.3300232

Sambasivan, N., Checkley, G., Batool, A., Ahmed, N., Nemer, D., Gaytán-Lugo, L. S., et al. (2018). “Privacy is not for me, it's for those rich women': performative privacy practices on mobile phones by women in South Asia,” in Fourteenth Symposium on Usable Privacy and Security (SOUPS 2018), 127–142.

Shahi, G. K., Dirkson, A., and Majchrzak, T. A. (2021). An exploratory study of covid-19 misinformation on twitter. Online Soc. Networks Media 22, 100104. doi: 10.1016/j.osnem.2020.100104

Shammi, M., Bodrud-Doza, M., Islam, A. R. M. T., and Rahman, M. M. (2021). Strategic assessment of COVID-19 pandemic in Bangladesh: comparative lockdown scenario analysis, public perception, and management for sustainability. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 23, 6148–6191. doi: 10.1007/s10668-020-00867-y

Smillie, L., and Blissett, A. (2010). A model for developing risk communication strategy. J. Risk Res. 13, 115–134. doi: 10.1080/13669870903503655

Solomon, D. H., Bucala, R., Kaplan, M. J., and Nigrovic, P. A. (2020). The “Infodemic” of COVID-19. Arthritis Rheumatol. 72, 1806–1808. doi: 10.1002/art.41468

Sultana, S., Guimbretiére, F., Sengers, P., and ad Dell, N. (2018). “Design within a patriarchal society: Opportunities and challenges in designing for rural women in Bangladesh,” in Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1–13.

Tam, W. J., Gobat, N., Hemavathi, D., and Fisher, D. (2021). Risk communication and community engagement during the migrant worker COVID-19 outbreak in Singapore. Sci. Commun. 44:240–251. doi: 10.1177/10755470211061513

Thanh, P. T. (2021). Can risk communication in mass media improve compliance behavior in the COVID-19 pandemic? Evidence from Vietnam. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy. doi: 10.1108/IJSSP-05-2021-0122

The Royal Society (2000). Scientists and the Media: Guidelines for Scientists Working with the Media and Comments on a Press Code of Practice. London: The Royal Society. Available online at: http://www.royalsoc.ac.uk.

Van Barneveld, K., Quinlan, M., Kriesler, P., Junor, A., Baum, F., Chowdhury, A., et al. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic: Lessons on building more equal and sustainable societies. Econ. Labour Relat. Rev. 31, 133–157. doi: 10.1177/1035304620927107

World Health Organization (2021). Bangladesh. Available online at: https://www.who.int/countries/bgd/ (accessed March 7, 2021).

Keywords: risk communication, COVID-19 pandemic, technology access, financial technology, women in Bangladesh

Citation: Ahmed N, Rony RJ, Sinha A, Ahmed MS, Saha A, Khan SS, Abeer IA, Amir S and Fuad TH (2022) Risk Communication During COVID-19 Pandemic: Impacting Women in Bangladesh. Front. Commun. 7:878050. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2022.878050

Received: 17 February 2022; Accepted: 07 April 2022;

Published: 18 May 2022.

Edited by:

Douglas Ashwell, Massey University Business School, New ZealandReviewed by:

Rafael Obregon, UNICEF United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund, United StatesDewi Rokhmah, University of Jember, Indonesia

Copyright © 2022 Ahmed, Rony, Sinha, Ahmed, Saha, Khan, Abeer, Amir and Fuad. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nova Ahmed, bm92YS5haG1lZEBub3J0aHNvdXRoLmVkdQ==

Nova Ahmed

Nova Ahmed Rahat Jahangir Rony

Rahat Jahangir Rony Anik Sinha

Anik Sinha Md. Sabbir Ahmed

Md. Sabbir Ahmed Anik Saha

Anik Saha Syeda Shabnam Khan

Syeda Shabnam Khan Ifti Azad Abeer

Ifti Azad Abeer Shajnush Amir

Shajnush Amir