- School of International Studies, Sun Yat-sen University, Zhuhai, China

Recent years have witnessed a flourishing development in the field of Public Relations (hereinafter as PR), which adjusts its scholarly attention from the quantitatively inclined studies on behavioral effectiveness to more of a critical discussion about social power and ideological influence within PR practice, consequently in favor of an interpretivist approach with a qualitative methodology toward a holistic analysis of a series of PR performances. Driven by the rise of this critical perspective in qualitative PR research, this paper aims to argue for a critical PR approach, tentatively by integrating a linguistic perspective from Critical Discourse Studies to discuss crisis communication as a social practice. Technically drawing on the theories of Political Public Relations (PPR in short) and Critical Discourse Studies, the proposed framework attaches equal importance to ideology, power, and identity instead of merely management function. It is illustrated that a critical investigation of PR performances approaches both media and institutional discourses, which are constructed by different social actors to frame a crisis and issue immediate responses, exercise its power control and maintain stakeholder relationships, and ultimately restore media and institutional images. On the one hand, the embedded ideologies enacted by the institutional control the media power and construct positive image representations. On the other hand, in order to exercise its administrative control, the institution must emphasize the need for all the stakeholders and the affected group to devote to resolving the crisis. The paper then concludes that the integrated framework together with the qualitative method of linguistic analysis offers PR scholars insights into the relationship between discourse, ideology, and crisis communication, as well as proposes implications on the interdisciplinary research from which general qualitative researchers could benefit. Hopefully, this integrated approach to crisis communication will contribute to broadening the research scope of analyzing communication as a social practice toward a comprehensive model.

Introduction

Conceptually speaking, Public Relations (PR) refers to the professional competence of an organization to communicate with the public, to assess and negotiate its management performances based upon the rapidly changing situations and stakeholder relationships (Chia, 2012, p. 11). With the frequent incorporation of public relations ideas into political communication, scholars have also started to analyze how institutional agents such as the central government and the political parties reproduce, monitor, and politicize their conveyed information (see Boukala, 2014; Boyd and Kerr, 2016; Krzyzanowski, 2018). Consequently, political public relations (PPR), recognized as an area of political studies, comes in and covers the domains of PR, political communication and political science. McNair (2011) summarized the history of PPR in his book An Introduction to Political Communication, and addressed four aspects: media management, image management, internal communications, and information management. According to Strömbäck and Kiousis (2011, p. 8), PPR refers to the process in which “an organization or individual actor for political purposes, through purposeful communication and action, seeks to influence and to establish, build and maintain beneficial relationships and reputations with its key publics to help support its mission and achieve its goals”. Thus, PPR is concerned with public relations under the political context, which aims to handle mutual/multiparty relations, address political issues by employing successful communication actions and effective strategies, maintain institutional and individual images.

Traditionally, whether in terms of business organizations or political institutions (collectively as institutions or institutional discourse), (P)PR studies are predominantly behaviorist and quantitatively inclined, technically measuring the institutions and the stakeholder groups' communication and management performances regarding the level of competence as well as the degree of effectiveness. Nevertheless, the past decade has witnessed the rise of another research approach, which employs a critical dimension in discussing the PR issues (Martinelli, 2011, p. 44). More specifically, studies of this aspect invite an interpretivist approach to unveil the ideological impact exerted on the target stakeholders, thus in favor of a qualitative methodology toward a holistic analysis. Thematically, Edwards (2016) summarizes the history of PR especially the emergence of criticism in the field with three consecutive periods of development. Initially, PR started as a field for the staff of an organization only to learn about the specific skills, techniques and management functions. That is to say, to manage stakeholder relations calls for the staff to grasp professional skills and fulfill the strategic goals. Later, PR was further established by industrial practitioners as a crucial practice in the business industry, emphasizing the role that PR knowledge plays in relationship management. PR researchers paid their attention not only to the theoretical knowledge but also to their workplace practice. A critical investigation into PR issues was conducted later and topics such as gender and racial discrimination first appeared in PR literature across different disciplines (e.g., sociology, cultural studies, and political science) (see Toth and Heath, 1992 for Rhetorical and Critical Approaches to Public Relations; Heath et al., 2009 for Rhetorical and Critical Approaches to Public Relations II; L'Etang et al., 2016 for The Routledge Handbook of Critical Public Relations). With the development of PR fostered by scholars and practitioners, crisis management finally becomes a crucial topic of critical investigation in PR studies, e.g., communication and power in society (Edwards, 2016, p. 20). Nowadays, critical studies of public relations in this aspect have flourished and focused on the manipulated use of media, corporate, and government power in handling a series of political, social, and natural crises. Driven by the rise of this critical perspective in qualitative PR research, this paper argues for a critical PR approach to crisis communication by integrating two perspectives: Public Relations and Critical Discourse Studies.

PR Perspective: Crisis Response as Material Action

Crisis, Crisis Recognition, and Response as Part of the Communication Process

According to Coombs (2007, p. 2-3, as cited in Coombs, 2010, p. 19), the term “crisis” is generally defined as “the perception of an unpredictable event that threatens important expectancies of stakeholders and can seriously impact an organization's performance and generates negative outcomes”. Based on the definition, three features are identified in times of a crisis: first of all, a crisis is typically unexpected to occur for the target and the audience, involving “non-routine events” and causing “a high degree of uncertainty and anxiety” (Wang, 2016); second, the interest groups known as stakeholders must be addressed in a series of crisis events; third, whether it is a business organization, or a political institution or any other agents, a crisis results in negative consequences.

To dip into a comprehensive analysis of crisis communication and management, Coombs (2007, 2012, 2015) proposes a three-stage approach: precrisis, crisis event and postcrisis, of which crisis recognition and response are prioritized. Crisis recognition refers to the process in which a crisis is announced and confirmed through framing by different institutional agents (business, political, and media agents) depending on three factors of the crisis nature: crisis dimensions, expertise of the dominant coalition and persuasiveness of the presentation (see Coombs, 2015, p. 111). After crisis recognition, crisis response is the first step to its material actions during the series of crisis events. On receiving the latest information, a crisis management team is required to inform both internal and external stakeholders of its comments, plans and actions. During the communication process, in principle the team should respond quickly, be consistent and open (Coombs, 2015, p. 130); crisis response should contain instructing information to avoid severe damage, adjusting information for reputational management (Coombs, 2015, p. 139).

Institutional Image Repair and Situational Crisis Communication

Crisis response is essential to image construction in the following ways. First of all, if communication fails in a crisis, institutional image will be damaged or collapse. Second, communication between both internal and external stakeholders contributes to a better understanding until the crisis settlement; otherwise, institutional reputation may endure a dramatic decline. Third, feasible or convincing solutions need to be conveyed to the key publics through successful communication skills for image repair. Recent studies have already illustrated how the business organizations and political institutions rebuild their images or promote their reputation, with much attention to two PR theories: Benoit (1997) image restoration theory and Coombs' (2015) situational crisis communication theory.

Benoit (1997) proposed five image repair strategies (with tactics) of maintaining institutional reputation: denial, evasion of responsibility, reduction of offensiveness, corrective action, and mortification. Guided by this theory, scholars have conducted abundant studies on national image repair in crisis, e.g., Hurricane Katrina in US (Liu, 2007; Benoit and Pang, 2008; Benoit and Henson, 2009) and product recall crisis in China (Cai et al., 2009). For example, Benoit and Henson (2009) discuss President Bush's image repair discourse on Hurricane Katrina but focuses on one single speech with three strategies: bolstering (as of reducing offensiveness), defeasibility (evading responsibility), and corrective action. They think the federal response and the strategies used did not manage to persuade US citizens. For instance, defeasibility is considered as inappropriate when the government could not justify its inefficiency (Benoit and Henson, 2009, p. 44). Overall, President Bush was criticized for being slow and inefficient in response and the administration got scolded for being incompetent in handling the emergency issues especially after 9/11, and his role as US President failed to live up to the public expectations. Another study by Cai et al. (2009) investigates how China managed its government image by handling public diplomacy affairs in a product recall crisis in the year 2007. By analyzing official statements, press transcripts and news materials, the study concludes that China employed different image repair strategies to project an image transformation from a “hurried and harried” to “surer and more determined” country (Cai et al., 2009). The theory with its strategies and tactics helps to analyze the effectiveness of crisis responses toward the political goal of image restoration.

Building on image repair theory, Coombs (2015) proposes the situational crisis communication theory (SCCT) to evaluate the reputational threat in times of a crisis event, which produces a more specific PR method to address image issues. In SCCT, the crisis management team should locate the crisis type(s), refer to the crisis history, and attend to its prior reputation (Coombs, 2015, p. 150-151). Importantly, Coombs makes a detailed list of response strategies with regard to four postures: denial, diminishment, rebuilding and bolstering. The first strategy is denial, which includes attacking the accuser and scapegoating. Attacking the accuser means refuting the accusation from the counterpart and scapegoating means putting the blame on others. The second strategy is diminishment, including excusing and justification. Making an excuse refers to the process of finding reasons for the crisis and the behavior. The third is rebuilding, with compensation and apology. Responsible actors have to compensate and apologize for the misdeeds. The last strategy bolstering, which means boasting of the good traits of the stakeholders, is divided into reminding, ingratiation and victimage. According to Frandsen and Johansen (2017, p. 110-111), Coombs' SCCT offers guidelines to maintain institutional reputation, negotiated based upon the “causal attribution process” starting from analyzing crisis type(s), intensifying factors, attribution of crisis responsibility to selection of appropriate response strategies.

The above-mentioned are what Hearit (2021) called “message strategies”, whose study helps PR scholars and practitioners to identify the most appropriate pattern(s) of response in different contexts of a crisis together with their evaluation, yet disregarding the social, cultural, and ethical situations. A narrative approach to crisis communication has become an alternative instead to elaborate on the “storytelling strategies” employed in institutional crises, paying equal attention to the narrative form as well as universal nature (Marson, 2014). In fact, Sellnow et al. (2019) have mentioned that the ambiguity of a crisis generates a “narrative space” of interpretations, which consists of the initial debatable narratives, then a more dominant description, and finally crisis implications. In this process, Hearit (2021) summarizes two guiding principles of offering the crisis narrative accounts, namely fidelity and coherence, both contributing to a meaningful as well as consistent construction of a crisis.

CDS Perspective: Crisis Communication as Social Practice

Introduction to Critical Discourse Studies

As a sub-branch under PR, research on crisis communication addresses the response strategies selected, the stakeholder relationships negotiated, and the communication power enacted. Recent scholars have argued for a new PR research orientation, which emphasizes the need to employ a critical approach for examining social factors and their ideological effects on PR practices (Martinelli, 2011, p. 44). The focus, shifting from management to ideology, necessitates a better understanding about PR in terms of social power and influence (McKie and Munshi, 2009). Inspired by the theoretical input in this aspect, this paper aims to integrate a linguistic perspective from Critical Discourse Studies (CDS) to discuss crisis communication as a social practice, where PR-related actors construct or reproduce crisis reality in and through discourse.

CDS started from the idea of Critical Linguistics (CL), which first appeared in Language and Control (Fowler et al., 1979). Later, Fairclough (1989) coined the term of Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) in the field, which is defined by interpreting linguistic features and in particular how ideology and power via discourse influences the use of language. The common goal of CDA (CDS) is to demonstrate the seemingly “normal or neutral” techniques of shaping “the representation of events and persons for particular ends” (Machin and Mayr, 2012, p. 5). As a critical approach to discourse studies, CDS aims to deal with a social problem and focuses on how it is represented through discourse, involving not only a text analysis but also a critical evaluation. Discourse, power and ideology are the key words in CDS. First, discourse does not simply refer to “an extended stretch” of language, but “a socially constructed knowledge of some social practice” (Foucault, 1977, as cited in Van Leeuwen, 2008, p. 6). Secondly, power is discussed with domination, which reveals the unequal relationship between the social actors. Ideology is “a coherent and relatively stable set of beliefs or values” (Wodak and Meyer, 2016, p. 8-9) and contributes to “maintaining [,] transforming power relations” (Reisigl and Wodak, 2016, p. 25).

CDS Research on Institutional Image and Crisis Representation

CDS research into the study of institutional image and crisis management focuses upon media representations of institutional images in a crisis (e.g., Carvalho, 2006; Caldas-Coulthard, 2007; Jahedi and Abdullah, 2012; Wang and Liu, 2015; Kalim and Janjua, 2019; Zappettini and Krzyzanowski, 2019), and the discursive construction of identities in a business organization or political institution (e.g., Wodak et al., 2009; Aydin-Düzgit, 2014; Peng et al., 2021). On the one hand, news reports of a national crisis can be seen as recontextualized information concerning a crisis in the political context. On the other hand, the use of discursive strategies by the government or institutional actors contributes to revealing the “constructed institutional identities” (Aydin-Düzgit, 2014, p. 364). In fact, CDS scholars have utilized different approaches to analyzing institutional images and crisis issues such as Fairclough's (1992, 1995, 2001) three-dimensional model (TDM) for elaborating upon the dialectical relationship between discourse and social change; Wodak and Meyer (2009) discourse-historical approach (DHA) for addressing “identity management and increased public self-reflection” (Wodak et al., 2009, p. 2), Van Leeuwen (2008) discourse as recontextualized social practice. These approaches emphasize the roles that the political, institutional and media agents play in reframing institutional crises. For instance, to investigate the media representations of Iran's national image, Jahedi and Abdullah (2012) discuss the use of language and its ideological construction of Iran in New York Times by integrating Halliday's Systemic Functional Grammar (SFG) and Fairclough's TDM. The study examines the process types of SFG and analyses how the Iran-related participants were represented as social actors, which construes ideological meanings in the system. Analysis of the thematized structures and the lexical choices in news discourse suggest a negative orientation of depicting Iran as a threatening outsider which is associated with extremism, threat and anti-democracy. Fairclough's TDM model directs the audience to critically understand language in news discourse as a social practice. Other studies discuss the 2003 SARS outbreak in distant suffering reports (Joye, 2010), China's bullet-train crash (Wang and Liu, 2015), the risk conflicts and mediatized debate on GM food (Maeseele, 2015), Sweden's wildfire (Öhman et al., 2016), terrorist attack in Pakistan (Kalim and Janjua, 2019), Britain's exit from EU (Zappettini and Krzyzanowski, 2019), Google and Apple's crisis communication in China (Peng et al., 2021), etc.

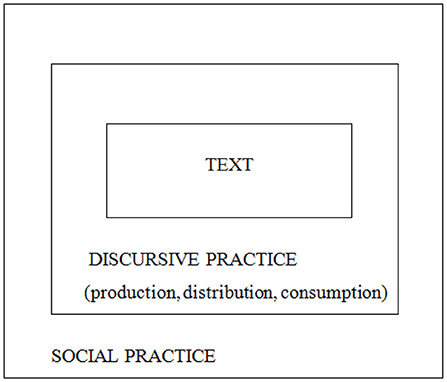

Fairclough's Three-Dimensional Model for Discourse and Social Change

Theoretically, to address discourse and social change, a three-dimensional model (TDM) of critical discourse analysis was proposed by Norman Fairclough in his well-known book Discourse and Social Change (1992), presented in Figure 1 (Fairclough, 1992, p. 73; Fairclough, 1995, p. 96-98 for a detailed version; Fairclough, 2001 for an improved model). According to Fairclough (1995), there are three dimensions in analyzing the discourse of a social event, including the linguistic text, discourse practice, and sociocultural practice. Consequently, analysis of discourse should be three-dimensional: “linguistic description of the language text, interpretation of the relationship between the (productive and interpretative) discursive processes and the text, explanation of the relationship between the discursive processes and the social processes” (Fairclough, 1995, p. 97). Specifically, in the first dimension, formal properties of the text are discussed such as grammar, vocabulary and text structure; in the second dimension, the processes of text production (socially positioned producers), the distribution and consumption (intertextuality and interdiscursivity) are involved; as for the last dimension, ideology, power and social practice are examined (Fairclough, 1992, p. 75, 78, 86).

A Critical PR Approach to Crisis Communication: 3 Steps

Integrating PR and CDS I: Framing Crises Through Media Discourse

The first aspect of the critical investigation into PR studies relates to communication power in and through media discourse, whose analysis focuses on how media sources as an important social agent exercise their huge power on framing social reality. According to Herman and Chomsky (2008, p. 61), during information dissemination, the mass media “inculcate individuals with the values, beliefs, and codes of behavior that will integrate them into the institutional structures of the larger society”, whose roles must be fulfilled via “systematic propaganda”. The consequence is that a crisis tends to be handled in the report by imposing an ideological perspective on the public and prompting this opinion to be accepted as a piece of fact (Ciofalo et al., 2015, p. 4). Pavelka (2015, p. 2163) raises the term “media manipulation”, holding that the texts are produced by the agents (actually text producers) as part of their communication tools and behavior to restructure social and cultural reality. Moreover, media coverage would contribute to negotiating and shaping the citizens' perception of the crisis (Bos et al., 2016, p. 97), and thus influence their own personalized framing (Van der Meer and Verhoeven, 2013). In that case, crisis communication under the political context embraces the feature of “framing”, which is equal to “emphasizing or deemphasizing particular aspects of political or social reality”, with applications in framing situations, attributes, risks, actions and responsibility (Hallahan, 2011, p. 178-191). These “systems of frames” are activated by the ideological language, whose repeated use contributes to normalizing the seemingly neutral messages (Lakoff, 2010, p. 72).

News media can be seen to report the event before, during and after a crisis. Apart from media power, Kapuściński and Richards (2016) examine framing effects on the audience perception of a crisis, based on which they categorize the framing types into “equivalency framing” and “emphasis framing”. Equivalency framing occurs when “different but logically equivalent words” are used to convey opposing crisis effects such as “5% unemployment” or “95% employment”; emphasis framing refers to the process in which “alternative” aspects of the crisis are emphasized among the facts such as “more advantages over disadvantages” (Kapuściński and Richards, 2016, p. 236-237). Other studies center not only on traditional (printed) media, but on social media, whose role is to escalate the communication effect and improve its efficiency and effectiveness of response (see Graham et al., 2015; Zhu et al., 2017; Cheng, 2020).

Integrating PR and CDS II: Negotiating Strategies via Institutional Discourse

The second aspect of the critical investigation into PR studies illustrates how crisis response as a social action can be constructed by the source agent. Due to the mystery or high stakes of a crisis, institutional responses and its actions play an important role in managing its reputation in the short/long term (Chewning, 2015, p. 73). Traditionally, PR researchers did not pay enough attention to the political establishment; instead, more emphasis was stressed on business organizations. For example, Berg and Robb (1992) examine the management performances of the company Kraft USA in a crisis about cheese promotion, in which a prize-winning game was designed for its products but encountered serious problems with printing errors. This PR study is later compared with two paradigm cases of Johnson & Johnson's product tampering case (the Tylenol case) and the Chrysler Motor fraud case. The research highlights the use of relevant cases in developing crisis management strategies, and contributes to the PR approach by what is called from a “generic” angle (see Berg and Robb, 1992, p. 108). Specifically, they suggest what Simons (1986, p. 36-37, as cited in Berg and Robb, 1992, p. 108) called “persuasive discourse”, which can be constructed in PR studies to identify the generic features and rules, summarize the most suitable patterns (of strategies) in use. More importantly, stakeholder engagement, which technically refers to “a process by which an organization engages relevant stakeholders for a clear purpose to achieve accepted outcomes” (Walker et al., 2015), has been a frequently used strategy of managing crisis preparedness and response (see Walker et al., 2015; Ahmed et al., 2020; Fissi et al., 2022). In fact, Arnold et al. (2012) have used critical discourse analysis as part of an integrated approach to discuss how diverse stakeholders reestablished the concept of expert knowledge, negotiated the use of power, and manage uncertainty or conflict in an adaptive collaborative management workshop.

As the PR discipline developed, not only management actions but also rhetorical strategies of both source and stakeholder agents are discussed during a crisis, in which the narration of a crisis by the source agent can be perceived as a response to legitimize its action and behavior, to convince the stakeholders of its competence and willingness to fulfill responsibility, and ultimately to downplay the crisis (Heath, 2004, p. 169-170, as cited in Boys, 2009, p. 294; Fonseca and Ferreira, 2015; Hansson, 2015). For example, during the crisis of clerical sexual abuse, Boys (2009, p. 297) finds that the United States Council of Catholic Bishops performed active operations as the defensive initiatives in positioning itself in the crisis, narrated in a “declarative” and “proactive” tone; and the second tactic is “silence” as a response. The analysis of rhetoric helps to demonstrate how the tactics are drawn on to publicize the actions and realize the desired management outcomes, and the use of response strategies has currently become the focus, not only on immediate reaction, but also on how the institution would answer in response to those unfavorable media reports. Nijkrake et al. (2015, p. 87) attach importance to institutional communication, especially the response strategies against a series of negative comments, indicating that the crisis is framed by the media reports from the aspects of conflict, crisis responsibility, economic losses and human-interest messages.

Integrating PR and CDS III: Locating Institutional Power, Ideologies, and Values

To initiate an integrated approach to PR studies means to attach equal importance to ideology and power instead of merely management function. As one of the first few scholars to reflect on critical perspectives for analyzing PR, Toth (2009) focuses more on how PR contributes to social changes, and to “disrupt our beliefs about organizations and public” (Toth, 2009, p. 53). In her historical preview, feminism and postmodernism were the first topics discussed within critical studies. Feminist criticism, studied under the PR approach, regards gender differences as “social constructions”, categorized as a stereotype to achieve imbalance in those PR positions, exposing both men and women to “narrow self-identities” (Toth, 2009; see Aldoory, 2009; Fitch, 2016 for other feminist studies). As for postmodernism in a narrow sense, a philosophical movement that calls for a more in-depth understanding about the role of ideology in power control, critical researchers endeavor to uncover the unequal power relations of institutional biases, currently backed up by the more powerful agents (Toth, 2009, p. 53). A topic of branding or reputation promotion can be found in Dolea (2016), highlighting the ideological influences of neoliberalism, which means that the central government and other political institutions are faced with fierce market competition and required to employ the strategic measures to build a positive image in the global market. PR comes in as international relations and communication management are prioritized in national branding. Other studies can be found such as in Waymer and Heath (2016), who aim to discuss the notion of race and the problem with racism via institutional discourse. More recently, Brunner and Smallwood (2019) propose an integrated approach called public interest relations (PIR) to address the negotiable relationship between public interest (social goodwill and community trust) and institutional goals. In their opinion, PIR should be enacted as an institutional value that encourages social changes, earns mutual trust and establishes goodwill in the long-term management; three PIR practices are technically involved, i.e., creation of space for facilitating dialogues, amplification of diverse voices and debatable viewpoints, suggestions on social and ethical issues for balancing short-term and long-term institutional missions (Brunner and Smallwood, 2019; Anderson, 2021). With that said, Johan et al. (2020) further conclude conflict management through stakeholder collaboration helps PR practitioners to consider more of public interests in the decision-making process, thus establishing a new institutional identity toward social stability and peace.

Discussion

Toward a Critical PR Approach to Analyzing Crisis Communication

This paper proposes an integrated approach to the studies on crisis communication, specifically a critical public relations approach to crisis response and image rebuilding. In fact, few studies have been conducted in the past decade integrating linguistic and management theories (except for Phillips et al., 2008; Motion and Leitch, 2016). Phillips et al. (2008) attempted to apply CDS theories to analyzing strategic management as a branch of business organization and management studies. They discuss the relationship between discourse and strategy, proposing a discursive model with three distinct approaches: narrating the rhetoric of strategy at the textual level; getting actors involved at the discourse level externally and internally; working out logics (“systems of shared meanings”) outside the institution at the social level (Phillips et al., 2008, p. 781). Their study provides management researchers with an outline of what to be considered in conducting a strategic management analysis. Fairclough's TDM approach is used as an effective way to analyze the management response represented by text (written) and talk (spoken) through institutional discourse. Besides, Motion and Leitch (2016) initiate a critical PR approach, with Foucault's problematization and Fairclough's TDM approach as the theoretical foundations of the research agenda. Problematization as a technique works in the study of institutional PR where the general goal of critical scholars is to “problematize public relations practices designed to normalize discourse transformations and create legitimacy for privileged power regimes or instances of power relations” (see Motion and Leitch, 2016, p. 144). In terms of the TDM approach to a social problem, texts under the PR mode involve not only the written language, but also other multimodal resources; discourse practice can be connected with the strategies, relationships, and the decision-making processes; social practice is intended to study “institutional stability or change”, and ultimately ideology in the broader and social context (Motion and Leitch, 2016, p. 146). However, Motion and Leitch do not elaborate on the process of doing a CDA, including how the theories of PR and CDS can be integrated toward a critical PR approach. Moreover, not enough details are explained about crisis communication as an important sub-area.

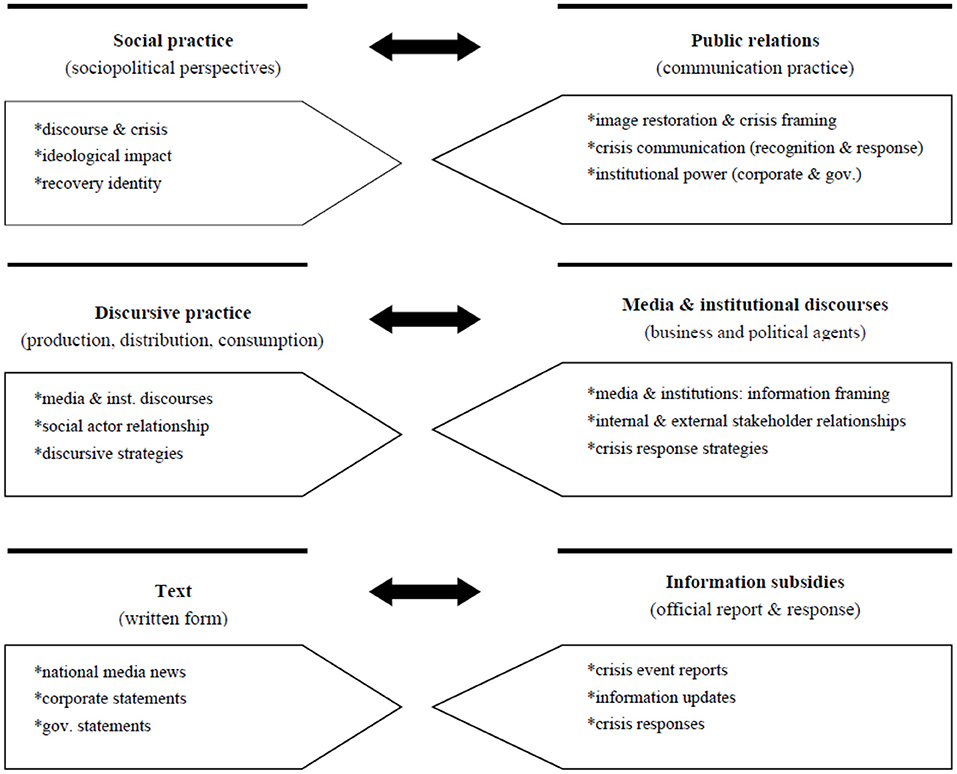

To Critique Public Relations as a Social Practice: A Proposed Framework

Based on the previous discussions of CDS and PR, a theoretical framework is proposed for analyzing institutional communication and management, specifically drawing upon Fairclough (1992) three-dimensional model (TDM) and the designated use of crisis response strategies. Fairclough's TDM theory contributes by discussing the dialectical relationship between discourse and social practice, when institutional communication should be addressed in terms of three levels of discourse practices: textual, discursive, and social practice. The use of crisis response theories contributes when information subsidies (e.g., state media reports, information updates and responses), stakeholder relationships and general PR practices are elaborated in parallel with the three levels of practices (see the figure below for the integration).

As Maeseele (2015) said, CDS aims to “reveal the role of discursive strategies and practices in the creation and reproduction of (unequal) relations of power, which are understood as ideological effects” (Maeseele, 2015, p. 282). Crisis communication as a social practice can be analyzed to illustrate how the institution employs crisis response strategies in times of a crisis to control information flow, counter criticism, and maintain its image. Both perspectives are complementary of each other and should be combined as a critical PR approach to the case studies of image building and crisis response. The framework above was developed through combining CDS and PR to achieve a better understanding of crisis response and image building through media and institutional discourses. The integrated approach should be used based on these principles: first, the research is supposed to be event-based, for which the crisis will be divided into several phases with different response strategies adopted by the internal stakeholders; second, the study may not be restricted to one discourse, but apply in different discourses, either spoken or written (e.g., media and institutional discourses), which are created by media and organizational agents in PR practices; third, crisis communication is recognized as a crucial part of PR, but the integrated approach should also involve other aspects such as media communication and relationship management, to which the applicability of the research could still be extended.

Contributions of a Critical PR Approach to Crisis Communication

As Richardson (2007) mentioned, “CDA approaches discourse as a circular process in which social practices influence texts, via shaping the context and mode in which they are produced, and in turn texts help influence society via shaping the viewpoints of those who read or otherwise consume them” (Richardson, 2007, p. 37). Regarding crisis communication as a type of social practice, a critical investigation into PR practices approaches both media and institutional discourses, constructed by the state media and the stakeholder nation or institution to frame the crisis, issue immediate responses, and restore its media and institutional images.

Relationship Between Discourse, Crisis, and Communication Practices

Crises are “socially produced and discursively constituted” phenomena since media and institutional discourses contribute to generating, eliminating, operating and tackling different crisis situations (De Rycker and Mohd Don, 2013, p. 4). Under this circumstance, crises are presumed to be subjective “constructions” of social events, as political agents such as the establishment tend to redefine the crisis situations, initiate possible actions, and further maintain positive stakeholder relationships (De Rycker and Mohd Don, 2013, p. 10-11). Stakeholder institutions are expected to undergo a series of responses and actions through institutional discourse. Whether managing the immediacy or gaining perceived control of the crisis, these institutions attempt to neutralize the negative impact, argue for the sense of professionalism and credibility, boasted of the positive traits maintained. Meanwhile, the pro-institutional media would foreground leadership roles, sense of trustworthiness and solidarity.

Media Discourse, Institutional Discourse, and Ideological Impact

One implication is that the stakeholder institutions would convey ideologies through media and institutional discourses, especially when they address the series of crisis communication and management efforts and stakeholder relationships. Jones (2012, p. 14) said that, “In some respects, ideologies help to create a shared worldview and sense of purpose among people in a particular group”. In that case, these “shared” ideas or conveyed values will play an important role in shaping the point of views about the institution's communication performances in tackling the crisis, known as ideological impact in conducting PR practices.

In terms of state media reports, positive representations of the stakeholders or stakeholder institutions can be seen as image restoration efforts. Technically recognized as part of information framing, the pro-institutional reports are expected to convey the sense of solidarity while depicting the institutions as being effective and efficient. The full support for and enthusiasm toward the affected group are extensively reported, with a faithful attempt to handle the external stakeholder connections. In this way, media discourse can be constructed to sensitize the key publics to the patriotic feelings for a united impression as well as an image of solidarity between the institutions and other key stakeholders. Similarly, the institutional responses, issued by the political or corporate agents, are expected to provoke the sense of solidarity, or their collective performances in and through institutional discourse. Specifically, institutional discourse can be constructed to narrate the entire management as in a process of engaging the internal members and prioritizing stakeholder interests to strengthen their confidence in terms of crisis handling.

Communication Power, Institutional Recovery, and Identity

The integrated approach also reveals how the use of communication power contributes to rebuilding a recovery institutional identity. In fact, Smudde and Courtright (2010) have summarized the relationship between PR and power, and also pointed out three dimensions of power nurtured in PR practices: hierarchical, rhetorical, and social power. Their idea indicates that the hierarchical dimension of power is concerned with “control and authority” as well as “domination and oppression”, with prominent leadership skills and roles presented for the organization to implement “power strategies” and exercise its administration. The rhetorical dimension of power contributes to demonstrating the impact and the effectiveness in using different “communication acts” or “tactics”, realized through linguistic tools and discourse. The social dimension of power is then determined by the stakeholder relationships and based on their shared ethics and collective performances toward professionalism.

To put it under a crisis context, the hierarchical dimension of power is reflected in the way the institution exercises its administrative control and maintain the sense of authority, which include demonstrating information validity and showcasing leadership roles by fulfilling institutional commitments. Moreover, the social dimension of power is implemented by establishing stakeholder relationships and enhancing positive mutual impact, which include emphasizing collective interests, foregrounding support, and boasting of the positive traits conveyed and commitments fulfilled. Finally, whether successfully or not, the rhetorical dimension of power is manipulated to defend response effectiveness, institutional misbehavior and the joint decisions, which is equal to excusing the institution from different aspects of criticism during the crisis. The three dimensions of power, realized through the use of communication actions and strategies, contribute to achieving the ultimate goal of institutional recovery. The institution in this process endeavored to redefine the possible breakthroughs, respond to the external suspicions and resolve different levels of crisis, in order to prove its firm beliefs in the resolution and establish a recovery identity.

Conclusion and Limitations

Drawing on the theories of (political) public relations and critical discourse studies, this paper has proposed a critical public relations approach to crisis communication, which hopefully will contribute to broadening the research scope of analyzing communication and management as a social practice toward a comprehensive model for both PR and CDS scholars. Moreover, it invites an interpretivist approach to unveil the ideological impact exerted throughout the management process due to the recent rise of a critical perspective in qualitative PR research.

Despite the contribution mentioned, the present study still has its limitations, one of which is the possibility of incorporating stakeholder engagement into the framework as another crucial part of institutional crisis communication. Except for the second level of discursive practice which emphasizes handling stakeholder relationships (see Figure 2 above for internal and external stakeholder relationships), the paper does not specify the process of “stakeholder identification” (Ulmer and Sellnow, 2000), the necessity to “establish value positions” with key stakeholders precrisis and after the crisis (Ulmer, 2001), their value maximization and interest legitimacy (Alpaslan et al., 2009), all supported by the stakeholder theory or relevant models. Future studies should continue to improve the integrated framework in these areas.

In a nutshell, the proposed framework integrating PR and CDS with the qualitative method of linguistic analysis offers PR scholars insights into the relationship between discourse, ideology and crisis communication, and gives methodological implications about the interdisciplinary research from which qualitative PR researchers could benefit.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ahmed, S. A. K. S., Ajisola, M., Azeem, K., Bakibinga, P., Chen, Y. F., Choudhury, N. N., et al. (2020). Impact of the societal response to COVID-19 on access to healthcare for non-COVID-19 health issues in slum communities of Bangladesh, Kenya, Nigeria and Pakistan: Results of pre-COVID and COVID-19 lockdown stakeholder engagement. BMJ Global Health. 5, 3042. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003042

Aldoory, L.. (2009). “Feminist criticism in public relations: How gender can impact public relations texts and contexts,” in Rhetorical and Critical Approaches to Public Relations II, eds. R. L. Heath, E. L. Toth, and D. Waymer (New York, NY; London: Routledge), 110–123.

Alpaslan, C. M., Green, S. E., and Mitroff, I. I. (2009). Corporate governance in the context of crises: towards a stakeholder theory of crisis management. J. Contin. Crisis Manag. 17, 38–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-5973.2009.00555.x

Anderson, L. B.. (2021). Serving public interests and enacting organisational values: an examination of public interest relations through AARP's Tele-Town Halls. Public Relations Rev. 47, 109. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2021.102109

Arnold, J. S., Koro-Ljungberg, M., and Bartels, W. (2012). Power and conflict in adaptive management: analysing the discourse of riparian management on public lands. Ecol. Soc. 17, 119. doi: 10.5751/ES-04636-170119

Aydin-Düzgit, S.. (2014). Critical discourse analysis in analysing European Union foreign policy: prospects and challenges. Cooper. Confl. 49, 354–367. doi: 10.1177/0010836713494999

Benoit, W. L.. (1997). Image repair discourse and crisis communication. Public Relat. Rev. 23, 177–187. doi: 10.1016/S0363-8111(97)90023-0

Benoit, W. L., and Henson, J. (2009). President Bush's image repair discourse on Hurricane Katrina. Public Relat. Rev. 35, 40–46. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2008.09.022

Benoit, W. L., and Pang, A. (2008). “Crisis communication and image repair discourse” in Public Relations: From Theory to Practice, eds. T. Hansen-Horn, and B. Neff (Boston, MA: Pearson Allyn and Bacon), 244–261.

Berg, D. M., and Robb, S. (1992). “Crisis management and the “paradigm case”,” in Rhetorical and Critical Approaches to Public Relations, eds. E. L. Toth, and R. L. Heath (Hillsdale, NJ: LEA Publishers), 93–109.

Bos, L., Lecheler, S., Mewafi, M., and Vliegenthart, R. (2016). It's the frame that matters: immigrant integration and media framing effects in the Netherlands. Intern. J. Intercult. Relat. 55, 97–108. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2016.10.002

Boukala, S.. (2014). Waiting for democracy: political crisis and the discursive (re)invention of the ‘national enemy' in times of ‘Grecovery'. Discourse Soc. 25, 483–499. doi: 10.1177/0957926514536961

Boyd, J., and Kerr, T. (2016). Policing ‘Vancouver's mental health crisis': a critical discourse analysis. Crit. Public Health. 26, 418–433. doi: 10.1080/09581596.2015.1007923

Boys, S.. (2009). “Inter-organisational crisis communication: exploring source and stakeholder communication in the Roman Catholic clergy sex abuse case,” in Rhetorical and Critical Approaches to Public Relations II, eds. R. L. Heath, E. L. Toth, and D. Waymer (New York, NY; London: Routledge), 290–309.

Brunner, B. R., and Smallwood, A. M. K. (2019). Prioritising public interest in public relations: public interest relations. Public Relat. Inquiry. 8, 245–264. doi: 10.1177/2046147X19870275

Cai, P. J., Lee, P. T., and Pang, A. (2009). Managing a nation's image during crisis: a study of the Chinese government's image repair efforts in the “Made in China” controversy. Public Relat. Rev. 35, 213–218. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2009.05.015

Caldas-Coulthard, C. R.. (2007). “Cross-cultural representations of “otherness” in media discourse,” in Critical Discourse Analysis: Theory and Interdisciplinarity, eds. G. Weiss, and R. Wodak (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan), 272–296.

Carvalho, A.. (2006). Representing the politics of the greenhouse effect: discursive strategies in the British media. Cri. Discour. Stud. 2, 1–29. doi: 10.1080/17405900500052143

Cheng, Y.. (2020). The social-mediated crisis communication research: revisiting dialogue between organisations and publics in crises of China. Public Relat. Rev. 46, 1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2019.04.003

Chewning, L. V.. (2015). Multiple voices and multiple media: co-constructing BP's crisis response. Public Relat. Rev. 41, 72–79. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2014.10.012

Chia, J.. (2012). “Public relations in the twenty-first century,” in An Introduction to Public Relations and Communication Management, 2nd Edn. eds. J. Chia, and G. Synnott (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 1–20.

Ciofalo, G., Di Stefano, A., and Leonzi, S. (2015). “Framing reality: power and counterpower in the age of mediatisation,” in Power and Communication: Media, Politics and Institutions in Times of Crisis, eds. S. Leonzi, G. Ciofalo, and A. Di Stefano, (Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing), 1–10.

Coombs, W. T.. (2007). Ongoing Crisis Communication: Planning, Managing and Responding, 2nd Edn. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Coombs, W. T.. (2010). “Parameters for crisis communication,” in The Handbook of Crisis Communication, eds. W. T. Coombs, and S. J. Holladay (Chichester; Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell), 1–53.

Coombs, W. T.. (2012). Ongoing Crisis Communication: Planning, Managing and Responding, 3rd Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Coombs, W. T.. (2015). Ongoing Crisis Communication: Planning, Managing and Responding, 4th Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

De Rycker, A., and Mohd Don, Z. (2013). Discourse and Crisis: Critical Perspectives, eds. Philadelphia, PA: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Dolea, A.. (2016). “The need for critical thinking in country promotion: Public diplomacy, nation branding, and public relations,” in The Routledge Handbook of Critical Public Relations, eds. J. L'Etang, D. McKie, N. Snow, and J. Xifra (London; New York, NY: Routledge), 274–288.

Edwards, L.. (2016). “A historical overview of the emergence of critical thinking in PR,” in The Routledge Handbook of Critical Public Relations, eds. J. L'Etang, D. McKie, N. Snow, and J. Xifra (London; New York, NY: Routledge), 16–27.

Fairclough, N.. (1995). Critical Discourse Analysis: The Critical Study of Language. London: Longman.

Fairclough, N.. (2001). “The discourse of new labor: critical discourse analysis,” in Discourse as Data, eds. M. Wetherell, S. Taylor, and S. Yates (London: Sage in Association with The Open University), 229–266.

Fissi, S., Gori, E., and Romolini, A. (2022). Social media government communication and stakeholder engagement in the era of Covid-19: evidence from Italy. Int. J. Public Sector Manag. 35, 276–293. doi: 10.1108/IJPSM-06-2021-0145

Fitch, K.. (2016). “Feminism and public relations,” in The Routledge Handbook of Critical Public Relations, eds. J. L'Etang, D. McKie, N. Snow, and J. Xifra (London; New York, NY: Routledge), 54–64.

Fonseca, P., and Ferreira, M. J. (2015). Through ‘seas never before sailed': Portuguese government discursive legitimation strategies in a context of financial crisis. Discour. Soci. 26, 682–711. doi: 10.1177/0957926515592780

Foucault, M.. (1977). Language, Counter-Memory, Practice: Selected Essays and Interviews, eds D. F. Bouchard (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press).

Graham, M. W., Avery, E. J., and Park, S. (2015). The role of social media in local government crisis communications. Public Relat. Rev. 41, 386–394. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2015.02.001

Hallahan, K.. (2011). “Political public relations and strategic framing,” in Political Public Relations: Principles and Application, eds. K. Hallahan (New York, NY; London: Routledge), 177–213.

Hansson, S.. (2015). Discursive strategies of blame avoidance in government: a framework for analysis. Discour. Soc. 26, 297–322. doi: 10.1177/0957926514564736

Hearit, K. M.. (2021). A blame narrative approach to apologetic crisis management: the serial apologiae of United Airlines. Public Relat. Rev. 47, 102106. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2021.102106

Heath, R.. (2004). “Telling a story: a narrative approach to communication during crisis,” in Responding to Crisis, eds D. Millar and R. Heath (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum), 167–168.

Heath, R.L., Toth, E.L., and Waymer, D. (2009). Rhetorical and Critical Approaches to Public Relations II, eds. New York, NY; London: Routledge.

Herman, E. S., and Chomsky, N. (2008). Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media. London: The Bodley Head.

Jahedi, M., and Abdullah, F. S. (2012). The ideological construction of Iran in the NYT. Austr. J. Linguist. 32, 361–381. doi: 10.1080/07268602.2012.705579

Johan, R. R., Hastjarjo, S., and Satyawan, I. A. (2020). Stakeholder collaboration to build peace through public interest relations (PIR) (Study on the commemoration of Suran Agung confict in Madiun). Informasi. 50, 137–152. doi: 10.21831/informasi.v50i2.29786

Jones, R. H.. (2012). Discourse Analysis: A Resource Book for Students. London; New York, NY: Routledge English Language Introductions.

Joye, S.. (2010). News discourses on distant suffering: a critical discourse analysis of the 2003 SARS outbreak. Discour. Soc. 21, 586–601. doi: 10.1177/0957926510373988

Kalim, S., and Janjua, F. (2019). #WeareUnited, cyber-nationalism during times of a national crisis: the case of a terrorist attack on a school in Pakistan. Discour. Commun. 13, 68–94. doi: 10.1177/1750481318771448

Kapuściński, G., and Richards, B. (2016). News framing effects on destination risk perception. Tourism Manag. 57, 234–244. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2016.06.017

Krzyzanowski, M.. (2018). “We are a small country that has done enormously lot”: the ‘refugee crisis' and the hybrid discourse of politicizing immigration in Sweden. J. Immigr. Refugee Stud. 16, 97–117. doi: 10.1080/15562948.2017.1317895

Lakoff, G.. (2010). Why it matters how we frame the environment. Environ. Commun. 4, 70–81. doi: 10.1080/17524030903529749

L'Etang, J., McKie, D, Snow, N., and Xifra, J. (2016). The Routledge Handbook of Critical Public Relations, eds. London; New York, NY: Routledge.

Liu, B. F.. (2007). President Bush's major post-Katrina speeches: enhancing image repair discourse theory applied to the public sector. Public Relat. Rev. 33, 40–48. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2006.11.003

Machin, D., and Mayr, A. (2012). How to do Critical Discourse Analysis: A Multimodal Introduction. London: Sage.

Maeseele, P.. (2015). Risk conflicts, critical discourse analysis and media discourses on GM crops and food. Journalism. 16, 278–297. doi: 10.1177/1464884913511568

Marson, S.. (2014). “Lock the doors”: toward a narrative-semiotic approach to organisational crisis. J. Bus. Techn. Commun. 28, 301–326. doi: 10.1177/1050651914524781

Martinelli, D. K.. (2011). “Political public relations: remembering its roots and classics,” in Political Public Relations: Principles and Applications. eds. D. K. Martinelli (New York, NY; London: Routledge), 33–53.

McKie, D., and Munshi, D. (2009). “Theoretical black holes: a partial A to Z of missing critical thought in public relations,” in Rhetorical and Critical Approaches to Public Relations II. eds R. L. Heath, E. L. Toth, and D. Waymer (New York, NY; London: Routledge), 61–75.

McNair, B.. (2011). An Introduction to Political Communication, 3rd Edn. London; New York, NY: Routledge.

Motion, J., and Leitch, S. (2016). “Critical discourse analysis: a search for meaning and power,” in The Routledge Handbook of Critical Public Relations. eds. J. L'Etang, D. McKie, N. Snow, and J. Xifra (London; New York, NY: Routledge), 142–150.

Nijkrake, J., Gosselt, J. F., and Gutteling, J. M. (2015). Competing frames and tone in corporate communication versus media coverage during a crisis. Public Relat. Rev. 41, 80–88. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2014.10.010

Öhman, S., Nygren, K. G., and Olofsson, A. (2016). The (un)intended consequences of crisis communication in news media: a critical analysis. Crit. Discour. Stud. 13, 515–530. doi: 10.1080/17405904.2016.1174138

Pavelka, J.. (2015). Strategy and manipulation tools of crisis communication in printed media. Soc. Behav. Sci. 191, 2161–2168. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.04.294

Peng, C., Liu, S., and Lu, Y. (2021). The discursive strategy of legitimacy management: a comparative case study of Google and Apple's crisis communication statements. Asia Pacific J. Manag. 38, 519–545. doi: 10.1007/s10490-019-09667-z

Phillips, N., Sewell, G., and Jaynes, S. (2008). Applying critical discourse analysis in strategic management research. Org. Res. Methods. 11, 770–789. doi: 10.1177/1094428107310837

Reisigl, M., and Wodak, R. (2016). “The discourse-historical approach,” in Methods of Critical Discourse Analysis, 3rd Edn. eds R. Wodak and M. Meyer (Los Angeles, CA; London: Sage), 23–57.

Richardson, J. E.. (2007). Analysing Newspapers: An Approach from Critical Discourse Analysis. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Sellnow, T. L., Sellnow, D. D., Helsel, E. M., Martin, J. M., Parker, J. S., et al. (2019). Risk and crisis communication narratives in response to rapidly emerging diseases. J. Risk Res. 22, 897–908. doi: 10.1080/13669877.2017.1422787

Simons, H. W.. (1986). Persuasion: Understanding, Practice and Analysis. 2nd Edn. New York, NY: Random House.

Smudde, P. M., and Courtright, J. L. (2010). “Chapter 12: public relations and power,” in The SAGE Handbook of Public Relations, 2nd Edn. eds R. L. Heath (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage), 177–190.

Strömbäck, J., and Kiousis, S. (2011). “Political public relations: defining and mapping an emergent field,” in Political Public Relations: Principles and Applications, eds. J. Strömbäck and S. Kiousis (New York, NY; London: Routledge), 1–32.

Toth, E. L.. (2009). “The case for pluralistic studies of public relations: Rhetorical, critical, and excellence perspectives,” in Rhetorical and Critical Approaches to Public Relations II. eds. R. L. Heath, E. L. Toth, and D. Waymer (New York, NY; London: Routledge), 48–60.

Toth, E. L., and Heath, R. L. (1992). Rhetorical and Critical Approaches to Public Relations, eds. Hillsdale, NJ: LEA Publishers.

Ulmer, R. R.. (2001). Effective crisis management through established stakeholder relationships: Malden Mills as a case study. Manag. Commun. Quart. 14, 590–615. doi: 10.1177/0893318901144003

Ulmer, R. R., and Sellnow, T. L. (2000). Consistent questions of ambiguity in organisational crisis communication: jack in the box as a case study. J. Bus. Ethics. 25, 143–155. doi: 10.1023/A:1006183805499

Van der Meer, T. G. L. A., and Verhoeven, P. (2013). Public framing organisational crisis situations: social media versus news media. Public Relat. Rev. 39, 229–231. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2012.12.001

Van Leeuwen, T.. (2008). Discourse and Practice: New Tools for Critical Discourse Analysis. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Walker, A. H., Pavia, R., Bostrom, A., Leschine, T. M., Starbird, K., et al. (2015). Communication practices for oil spills: stakeholder engagement during preparedness and response. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess. Int. J. 21, 869. doi: 10.1080/10807039.2014.947869

Wang, X. Q.. (2016). People's motivation to participation in social network sites, subsequent behaviours, and situation self-awareness following a crisis: evidence from the MH370 flight incident. Aust. J. Inform. Syst. 20, 1–22. doi: 10.3127/ajis.v20i0.1218

Wang, W. W., and Liu, W. H. (2015). Critical discourse analysis of news reports on China's bullet-train crash. Stud. Literat. Lang. 10, 42–49. doi: 10.3968/6401

Waymer, D., and Heath, R. L. (2016). “Critical race and public relations: the case of environmental racism,” in The Routledge Handbook of Critical Public Relations, eds. J. L'Etang, D. McKie, N. Snow, and J. Xifra (London; New York, NY: Routledge), 289–302.

Wodak, R., de Cillia, R., Reisigl, M., and Liebhart, K. (2009). The Discursive Construction of National Identity. 2nd Edn. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Wodak, R., and Meyer, M. (2009). Methods of Critical Discourse Analysis (Introducing Qualitative Methods Series). 2nd Edn, eds London: Sage.

Zappettini, F., and Krzyzanowski, M. (2019). The critical juncture of Brexit in media and political discourses: from national-populist imaginary to cross-national social and political crisis. Crit. Discour. Stud. 16, 381–388. doi: 10.1080/17405904.2019.1592767

Keywords: public relations (PR), communication practice, critical perspective, Critical Discourse Studies (CDS), ideology, power, identity

Citation: Wang H (2022) To Critique Crisis Communication as a Social Practice: An Integrated Framework. Front. Commun. 7:874833. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2022.874833

Received: 13 February 2022; Accepted: 26 April 2022;

Published: 16 May 2022.

Edited by:

Satveer Kaur-Gill, Massey University, New ZealandReviewed by:

Bahtiar Mohamad, Universiti Utara Malaysia, MalaysiaSibo Chen, Ryerson University, Canada

Copyright © 2022 Wang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Huabin Wang, d2h1YWJAbWFpbC5zeXN1LmVkdS5jbg==

Huabin Wang

Huabin Wang