- Learning and Teaching, The University of Newcastle, Callaghan, NSW, Australia

Much research into language contact, specifically on anglicisms in German, investigates the appearance and use of English borrowings in the print media published in Germany, Austria, or Switzerland. While these publications are intended for a German-speaking audience in majority German-speaking countries, it remains to be explored what happens to English loans when they appear in a German-language publication produced in a majority English-speaking country. This raises questions about how the local environment, issues and events related to the country of publication are represented lexically to a local audience who are familiar with these concepts in English. Using both quantitative and qualitative methods, I analyze a selection of anglicisms related to Australia in a corpus of 25,147 types and 223,671 tokens from the Australian-published German-language newspaper Die Woche. The findings indicate that most of these anglicism types occur within the semantic fields of place and society. The frequency and distribution of various types, such as adapted and unadapted borrowings, loan translations and loan renditions, including flagged lexical units and codeswitching, appears to be determined mostly by authorship and intended audience of individual articles rather than the newspaper as a whole. Articles attributed to the dpa (Deutsche Presse-Agentur “German Press Agency”) contain a higher incidence of loan translations, loan renditions, and flagging devices, particularly of proper nouns, than those attributed to local journalists. While this may allow international readers of the articles distributed via the dpa to better understand Australian events, institutions, social phenomena, and place, it may have a distancing or even alienating effect for local German speakers, situating them outside mainstream Australian society.

Background: Anglicisms in German

Corpus analyses on anglicisms in the German print media have been ongoing since at least the late 1950s (e.g., Zindler, 1959; Carstensen, 1965; Yang, 1990; Donalies, 1992; Langer, 1996; Plümer, 2000; Adler, 2004; Onysko, 2007; Knospe, 2014). Der Spiegel, in particular, appears to have attracted the most research interest and has been considered a conduit of English lexical items into German (Carstensen, 1965, p. 22) due to its modern, cutting-edge journalistic style influenced by American models such as Time magazine (Onysko, 2007, p. 99). One of the functions of anglicisms in news articles is to provide an accurate representation of the topic itself, its background, and the location of events taking place in an English-speaking country, in addition to providing a strong sense of the atmosphere, or local color, of the places and people that the journalistic report is about. Authors achieve this function by including the original English titles of, for example, institutions, or the terms denoting the cultural characteristics or political phenomena (Plümer, 2000, p. 259) that are often embedded within the culture and do not occur in the borrowing language (Onysko and Winter-Froemel, 2011, p. 1,553; Plümer, 2000, p. 259).

However, not all authors researching anglicisms include proper nouns in their analyses (e.g., Onysko, 2007; Burmasova, 2010; Pulcini et al., 2012; Zenner et al., 2012; Gottlieb et al., 2018). One such author is Yang (1990, p. 119), who excluded from his analysis of anglicisms in Der Spiegel proper nouns indicating people, places, and institutions, e.g., the names of presidents (e.g., Carter, Reagan), cities (e.g., New York, London, Hollywood), and political terms (e.g., Commonwealth, Labor Party, State Department). However, excluding proper nouns from anglicism studies dispenses with a rich source of stylistic information, semantic connotation, and uniqueness, as Plümer (2000, p. 259–266) argues. Therefore, she included the names of institutions such as Air Force, College, and Buckingham Palace as important indicators of local color in her study on the use of anglicisms in major newspapers and television news programs in Germany and France. Nevertheless, the inclusion of proper nouns needs to be considered according to certain guidelines. For example, names of people, such as Carter and Reagan mentioned above, currencies, and the names of private commercial enterprises may well be excluded from analysis because these may be used around the world and provide little information on English influence on any given language. However, the names of geographical locations, education institutions, as well as political and legal terms present an interesting area for exploration, particularly when such entities originate in the Anglosphere and are presented in both their original and translated forms. It warrants investigating to what extent translations of such terms do occur in a particular text, especially considering the overall context.

Thus far, research on anglicisms in general has relied on data obtained from publications appearing in majority German-speaking countries. However, German is also spoken as a minority or migrant language in many countries around the world, including Australia, where German-language radio broadcasts, podcasts, internet sites, and print media are produced for a local audience. This leads, then, to the research questions guiding this paper, namely, what happens in the German-language print media published outside Europe for German speakers in English-dominant countries such as Australia? How is Australia, its icons, culture, institutions, and way of life portrayed—through the use of unadapted anglicisms or other means such as loan translations of autochthonous terms?

The structure of this paper is as follows: I will first introduce the definition of anglicism and the terminology used, before explaining the source and procedure of data extraction for analysis, including limitations. Then, I will provide quantitative results and explore specific examples in a qualitative manner and conclude by suggesting refinements for further research.

Materials and Methods

This section contains a brief description of the source for the corpus under investigation, as well as the theoretical background and methods used to create the dataset for analysis. It concludes with a summary of the issues and limitations encountered.

The Die Woche Corpus

The corpus of 25,147 types and 223,671 tokens used in this study derives from 201 editions (June 2017–July 2021) of Australia's only surviving German-language newspaper, Die Woche. Founded in 1957, this weekly publication has a current readership of over 30,000 across the country (Die Woche Australien, 2017)1 and is available in printed and electronic formats. Since its inception, the newspaper has provided the German-speaking public with articles on politics, economics, science, society and culture, and sport from Europe and Australia. It provides news on local events within the local German-speaking community and social clubs and is a means of connecting and informing the widely dispersed German-speaking community in Australia. It acts as a platform for businesses catering toward residents with a German, Austrian, or Swiss heritage, and advertises legal and health services where community members can use the German language with service providers.

In every 24-page edition of Die Woche, one page each is dedicated to news items specifically related to Australia and New Zealand, and it is these articles only that I used to source the lexical items in this study. Doing so not only increases the likelihood of the authors using English sources in their writing (Fiedler, 2012, p. 249), but it also provides the opportunity to explore how Australian culture and society is portrayed to German speakers living in the country.

The journalistic team consists of ten reporters based in Australia and in Europe and sources many articles from the dpa (Deutsche Presse-Agentur) “German Press Agency” which are available to media outlets internationally. This means that the newspaper has a duality of intended audiences. It contains not only articles written by local reporters for the local readership of German speakers participating in mainstream Australian society and who are exposed to Australian cultural concepts and Australian English, but also articles intended for a German-speaking audience abroad who do not have such familiarity or exposure to Australian society or concepts.

Creating the Dataset

To identify those anglicisms that refer to some specific aspect of Australia, its society, culture, geography, etc., I applied the broad definition of anglicisms proposed by Gottlieb (2005), p. 163 as “any individual or systemic language feature adapted or adopted from English, or inspired or boosted by English models, used in intralingual communication in a language other than English.” I interpreted this definition to also include what may be considered borderline anglicisms such as kangaroo, koala, and emu. None of these three is attested in the reference work on anglicisms in German, the Anglizismen Wörterbuch (Carstensen and Busse, 2001), while only kangaroo is classified as an anglicism in the Dictionary of European Anglicisms (Görlach, 2001, p. 174), and both kangaroo and emu are listed as having English origins in Duden Online.2 Despite this, I included all three here because of their iconic representation of Australia and while they may have origins among Australia's Indigenous languages (kangaroo and koala) and Portuguese (emu), these terms have spread to other languages through English.

I broadly refer to the lexical items under investigation here as Australia-related anglicisms. These reflect either uniquely Australian concepts (including landscape features such as Lake Mungo or cultural events such as Australia Day, etc.), or those that appear within the broader Commonwealth (e.g., political concepts such as Prime Minister), or broader still, those lexical items that derive from the Anglosphere but still have a strong association with Australia (e.g., sports such as surfing) and mostly do not occur within the German-speaking language and cultural areas. This also extends to proper nouns that refer to, for example, places, universities, and organizations. These are of interest because they may appear in both unadapted and adapted forms, thus providing some insight into the results of language contact beyond unadapted loans.

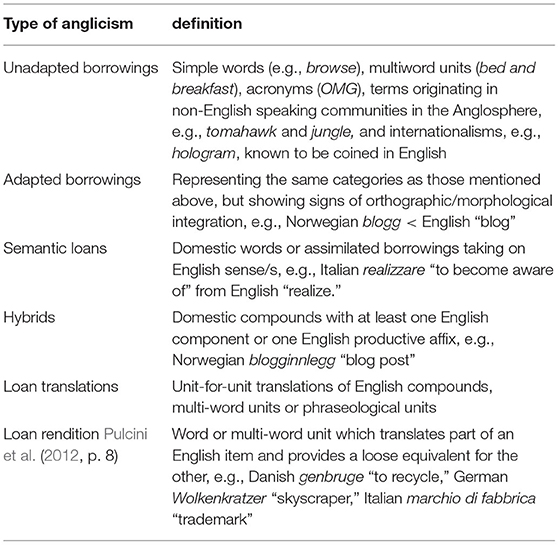

I classified these anglicisms into the categories detailed in Gottlieb et al. (2018, p. 7), supplemented by Pulcini et al. (2012, p. 8). An adaption of these categories is included in Table 1. I then used the concordance program AntConc (Anthony, 2021) to search each word individually and ascertain its forms, i.e., to allow for various grammatical affixes showing gender, plurality, case, etc., and to produce a type and token count. The most common and easily identifiable anglicisms are the unadapted borrowings. These are items clearly imported from English and retain their English orthography and morphology, e.g., Harbor Bridge. Those items that are adapted borrowings are also easily identifiable as originating in the Anglosphere, but have become morphologically and/or orthographically integrated, e.g., Kricket “cricket.” A semantic loan is an instance where an English meaning is applied to an existing autochthonous form, such as feuern “to fire” which has taken on the English sense “to dismiss someone from a job,” in addition to the earlier senses including “to shoot (a weapon).” Hybrids are forms where both domestic and English components are combined to form compounds such as Cricket-Spiel “cricket game.”

Table 1. Typology of anglicisms, adapted from Pulcini et al. (2012, p. 8) and Gottlieb et al. (2018, p. 7).

The final two categories, loan translations and loan renditions, are sometimes excluded from analyses of anglicisms because they are not easy to detect (Gottlieb et al., 2018, p. 7; Hunt, 2019, p. 30; Onysko, 2019, p. 188). Loan translations are those that are element-by-element translations of multi-element English words or phrases, leading to such examples as Goldküste “Gold Coast” and Todesotter “death adder.” Loan renditions are similar to loan translations except that only one element is directly translated and the other more loosely, e.g., Feuerwehr Westaustralien “Western Australian Fire Services” (literally “Fire Brigade Western Australia”) and Oberste Richterin “High Court Judge (f.),” (literally “highest judge”).

To identify the themes in which these Australia-related anglicisms are used, I labeled each lexical item according to its semantic field. That is, I grouped the items depending on their broad meaning or related subjects and labeled them accordingly. For example, I included King Billy-Kiefer “King Billy pine,” Mulgaschlange “mulga snake/king brown snake” and Penguin Parade within the semantic field of flora/fauna, and Backpacker-Steuer “backpacker tax,” Liberal Party, and Working Holiday Visum “working holiday visa” within the semantic field political/legal.

In addition to individual items, I also included code-switches in my analysis because they can also provide a good deal of insight into language contact situations and have particular pragmatic effects (Onysko, 2007, p. 89–91). However, there is debate surrounding the difference between borrowing and code-switching (see, e.g., Myers-Scotton, 1992; Clyne, 2003, p. 70–76; Knospe, 2014, p. 92–112; Poplack, 2018, Ch. 9; Gottlieb, 2020, p. 84–86; Schaefer, 2021, p. 573–574), and in synchronic analyses of language contact such as this, it is difficult to draw a clear distinction between the two (Gardner-Chloros, 2010, p. 195). However, in this paper, I take what might be considered a prototypical, narrow approach toward this issue. I restrict the concept of borrowing to that of single lexical items only, meaning that, in written discourse, prototypical code-switches are considered phrasal units or full sentences intended for plurilingual audiences (Gottlieb, 2020, p. 85; Matras, 2009, p. 110–114; Poplack, 1993, p. 255–256; Winford, 2003, p. 107–108). Therefore, all instances of English lexical items appearing in the Die Woche corpus are treated as borrowings and are only treated as code-switches when it is clear from the context that an English user is the source and recipient of a message, such as in quotations, or when an entire sentence is in English.

At the same time, it is useful to recognize that code-switching and borrowing appear on a continuum (Clyne, 2003, p. 71) and many of the items under investigation appearing on this continuum are flagged. Referred to as metacommunicative markers by Fiedler (2012), or alterity markers by Winter-Froemel (2021, drawing on Pflanz, 2014), flagging devices in written discourse mark non-canonical lexical items through the use of quotation marks or italics (Saugera, 2012, p. 138–140) indicating that the items do not belong to the matrix clause and thus form “lexical islands” (Onysko, 2007, p. 296). Other flagging devices include paraphrasing, near-synonyms, translations and explanations in the surrounding text (Sharp, 2007, 234).

Excluded from this study are lexical items that are clearly of English origin but define concepts not specifically associated with Australia. An example of such a term is Lockdown, an attempt by governments to reduce the spread of the COVID-19 virus by temporarily requiring residents to stay at home and by moving most retail and business activity online. Furthermore, I excluded the names of private companies because generally they do not undergo morphological or orthographical adaptation and thus provide little insight into language contact processes.

Issues and Limitations of the Study

In analyzing the use of Australia-related anglicisms, various issues concerning not only the methodology but also the materials and typology need to be taken into account. Firstly, the corpus also contains articles on topics from New Zealand. However, to overcome this and to focus only on topics related to Australia (with which I am more acquainted and am able to identify more easily), I first found the lexical items under investigation in the printed editions of the corpus that focused on Australia before searching for them in the concordance software. It is here that I remind the reader that all quantitative results (i.e., type and token counts) should be considered indicative only, where the main aim is to investigate a few select items in-depth, not overall anglicism use in the newspaper.

Secondly, this paper, with its qualitative methodology, includes an interpretive analysis of the content. As such, it involves a degree of subjectivity based on my own personal, cultural, and linguistic background, current context as an L1 user of Australian English and citizen of that country. With such reliance on personal intuition, there is a risk of introducing bias, and it also means that the study is not replicable. However, it is also common in the field of anglicism research for the investigator to rely on a degree of native-speaker intuition in identifying and classifying anglicisms, particularly in instances involving the interpretation of texts and the function of lexemes (see, e.g., Burmasova, 2010, p. 50; Onysko, 2007, p. 173; Zindler, 1959, p. 2). Furthermore, the precise definition of many terms in the field are still debated among lexicographers, and thus are open to interpretation. I aim to be as objective as possible here, while acknowledging that true objectivity in such an endeavor is impossible.

Thirdly, the corpus materials, as with many other similar studies, relied on the print media as a data source. As such, the source is written, highly edited, targets specific readers, and contains stories considered to be of interest to the public by the editorial team. In addition, the corpus is restricted further to only those articles making reference to Australia, and thus, is not comparable to other studies of anglicisms in the print media in general, nor is it truly indicative of the use of anglicisms in Australian German.

Finally, taking an approach beyond focusing on adapted and unadapted borrowings to include indirect loans such as loan translations and loan renditions may also be problematic. This is mostly because identifying such borrowings from a purely lexical point of view is difficult, and a keen sense of etymology is often required. Despite this, some indirect borrowings were identifiable and worthy of investigation as they provide insight into the variety of Australia-related anglicisms in the corpus and how Australia is portrayed in the newspaper overall.

Findings and Discussion

This section contains both the numerical and qualitative findings of the analysis. Following each point is a brief discussion.

Type and Token Count

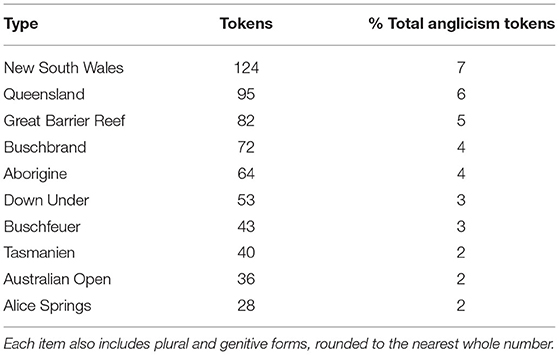

The total dataset of Australia-related anglicisms consists of 375 types and 1,653 tokens deriving from 261 English etymon types. Almost all lexical items in the dataset are nouns, except for one type and 53 tokens of Down Under (appearing both as an adverb as well as a noun). Table 2 shows the frequency of the ten most frequent Australia-related anglicisms representing between 2 and 7% of anglicisms in the dataset. These include the two states of New South Wales and Queensland (with 124 and 95 tokens, respectively), the Great Barrier Reef (82 tokens), Buschbrand “bushfire” (72 tokens), Aborigine (64 tokens each), Down Under (53 tokens), Buschfeuer “bushfire” (43 tokens), Tasmanien “Tasmania” (40 tokens), Australian Open (36 tokens), and Alice Springs (28 tokens).

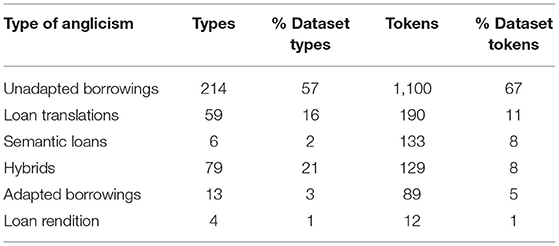

Categorizing the tokens into borrowing types (as shown in Table 3), reveals that unadapted borrowings are the most frequent, with two-thirds of tokens (67%) in the dataset belonging to this category. This is followed by loan translations at 11%, with the remaining categories of semantic borrowings, hybrids, adapted borrowings, and loan renditions each below 10%.

Table 3. Total anglicism types and tokens for the dataset per type of borrowing, rounded to the nearest whole number.

Unadapted Borrowings and Loan Translation of Proper Nouns

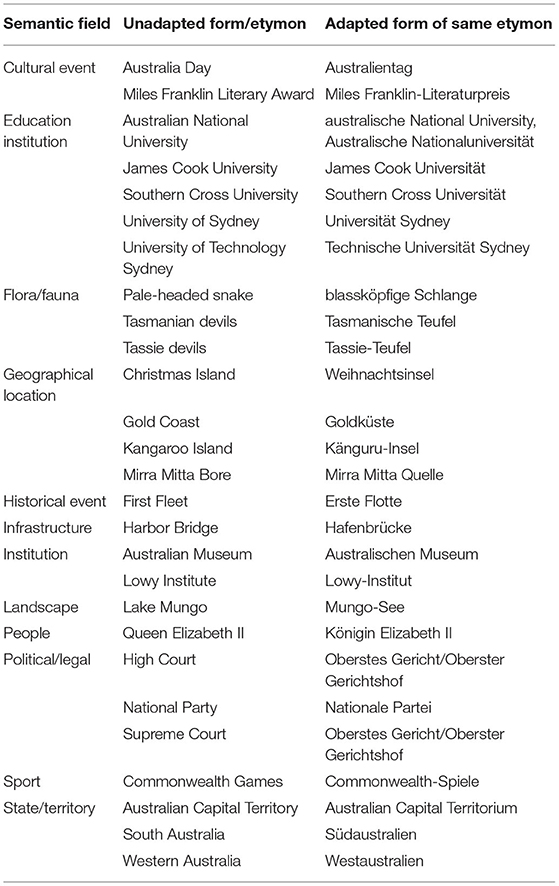

There are 27 instances where both unadapted and adapted forms of the same proper noun appear (see Table 4). Most of the adapted forms are either loan translations, e.g., Hafenbrücke for “Harbor Bridge” or Weihnachtsinsel for “Christmas Island,” or partial loan translations such as Commonwealth-Spiele for “Commonwealth Games.” Sometimes both forms occur within the same article.

Table 4. Unadapted and adapted forms of the same etymon co-existing in the dataset, per semantic field.

There are four instances of loan renditions modeled on proper nouns. Interestingly, there was no difference made between the High Court (dealing with federal matters) and the Supreme Court (at the state level), with Oberstes Gericht and Oberster Gerichtshof being used synonymously in both instances. While both back-translate to “highest court,” the use of the capital letter < o> here indicates that it is a proper noun (20 tokens) rather than a common noun (14 tokens). Similarly, the office of High Court Judge is referred to as Oberste Richterin “highest judge” (marked here for feminine gender). A similar lack of distinction between federal and state levels occurs with the use of the title Premierminister(in). Here, the term is used to refer to both the prime minister, leader of the federal parliament, and premier, leader of each state's parliament.

There may be several reasons for including both unadapted borrowings and loan translations of the same proper nouns. Loan translations provide an accurate and factual representation of their etymons, whereas unadapted forms also add local color. Similarly, particularly if both forms appear in the same article, the variation may also be an aid to understanding, or simply a means of providing lexical variation. Nevertheless, the use of both forms of proper nouns, especially those referring to geographical locations, demonstrates that such categories form their own specific area outside mainstream anglicism studies, beyond the general lexicon (Burmasova, 2010, p. 159). As such, they warrant their own type of investigation outside the scope of this paper.

As for the loan renditions of proper nouns, making an unclear distinction between levels of the legal and parliamentary systems might not be important. This is especially so when they are presented to an international audience because the court proceedings, and results thereof, are the focal point in each article, and not necessarily the particular level of the legal system at which the trials take place. Similarly, the distinction in jurisdiction between a High Court Judge and Supreme Court Judge diminishes when the focus is placed on the crime or the outcome of the trial. Nevertheless, the same cannot be said for the blurred boundaries between Prime Minister, and Premier, where the former is the leader of the national parliament, and is active on a global stage, while the latter is relevant only at the state level.

Semantic Loan: Busch “Bush”

The lexeme Busch is the only example in the corpus that may be classified as a semantic loan, that is, where an autochthonous term takes on an English meaning. In the Die Woche corpus, there are 138 tokens of the lexeme Busch, manifested mostly in lexical compounds such as Buschbrand/Buschfeuer “bushfire,” Buschland “bushland,” and Buschwanderer “bushwalker.” Specifically, there are 72 tokens of Buschbrand, 41 tokens of Buschfeuer (appearing to be more closely modeled on the English compound), in contrast to the mere six tokens of the native equivalent of Waldbrand “forest fire.”

In German, indeed also in British English, the noun Busch “bush” generally refers to a shrub; however, in Australian English (as well as other varieties of English spoken in Britain's former colonies, such as South Africa and New Zealand), a further layer of meaning has been added. In its entry for bush, the Oxford English Dictionary Online includes the definition:

9. a. … Woodland, country more or less covered with natural wood: applied to the uncleared or untilled districts in the former British Colonies which are still in a state of nature, or largely so, even though not wooded; and by extension to the country as opposed to the towns (“bush, n. 1”, 2021).

And more precisely, in the Australian Oxford English Dictionary, this particular meaning is indicated as belonging to Australian English:

3. (Aust.) natural vegetation.

• a tract of land covered in this.

4. (Aust.) country in its natural uncultivated state.

5. (Aust.) rural as opposed to urban life; the country as opposed to the town (“bush, 1”, 2004).

Thus, in Australian English, bush can refer not only to a shrub, but also forest, forested areas, and the countryside, and even includes small villages in rural areas. It is a culturally important, almost mythical location, connoting danger, hardship, and the pioneering spirit of the first white colonialists, while it retains a romantic sense of nostalgia that rests at the heart of many Australians, despite nearly 90% of them living in urban areas (Maude, 2018, p. 187). Bushfires, too, are an entrenched part of Australian life, particularly for those living in rural areas and the outer suburbs of Australia's cities. It is these additional layers of meaning that are evident in the German use of Busch in the corpus.

Reference to First Nations Peoples

The corpus contains 14 types and 64 tokens of the lexeme Aborigine. Thirteen types and 20 tokens appear as specifiers in hybrids, such as Aborigine-Flagge “Aborigine flag,” Aborigine-Kunst “Aborigine art,” and Aborigine-Mann “Aborigine man.” In contrast, only three types and tokens of Aboriginal occur: once in the unadapted borrowing Aboriginal Guide, once in the campaign Aboriginal Lives Matter, and once in the hybrid Aboriginal-Urbevölkerung “Aboriginal native-inhabitants.”

This provides perhaps the most striking piece of evidence for how a lexeme may diverge semantically in different languages. While the anglicism form in the Die Woche corpus appears to have retained its original neutral tone to refer to the original inhabitants of Australia, in modern Australian English, it has acquired negative connotations and is now considered taboo and offensive. The preferred current terms include Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders, First Nations peoples, or Aboriginal people (Korff, 2020). While there may be diversity of opinion within the community over which of the above three terms most people identify as being, Aboriginal appears to be the most common, unless referring specifically to people of Torres Strait Island origin.

Semantic Fields

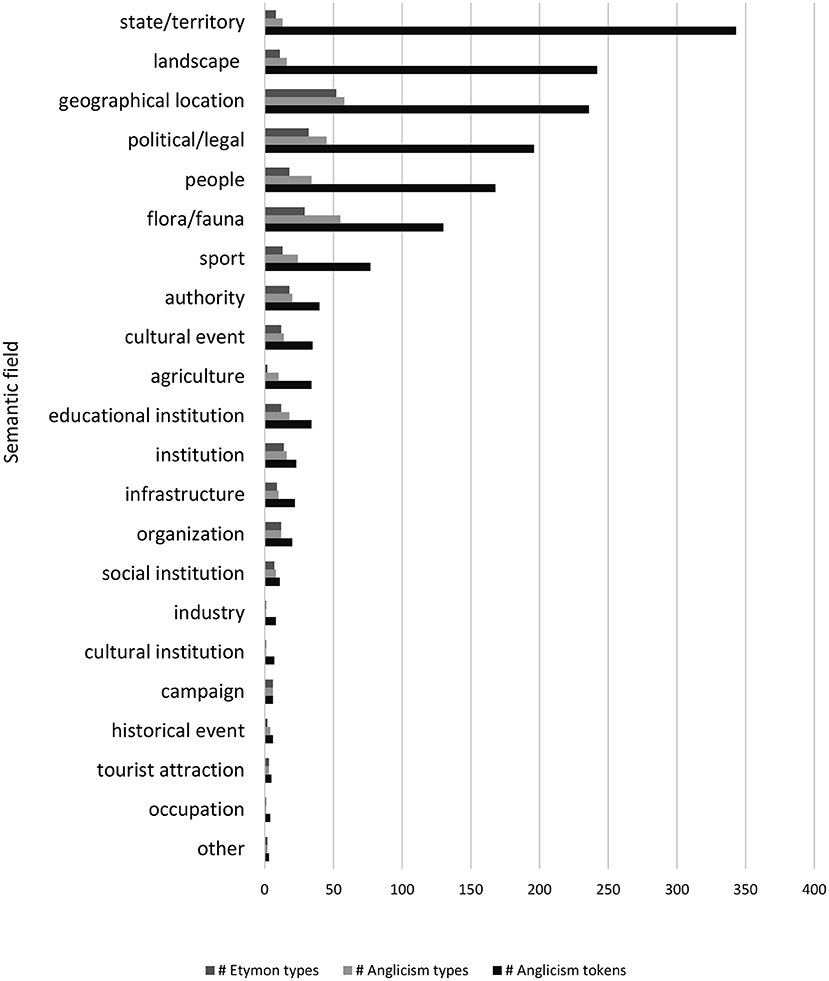

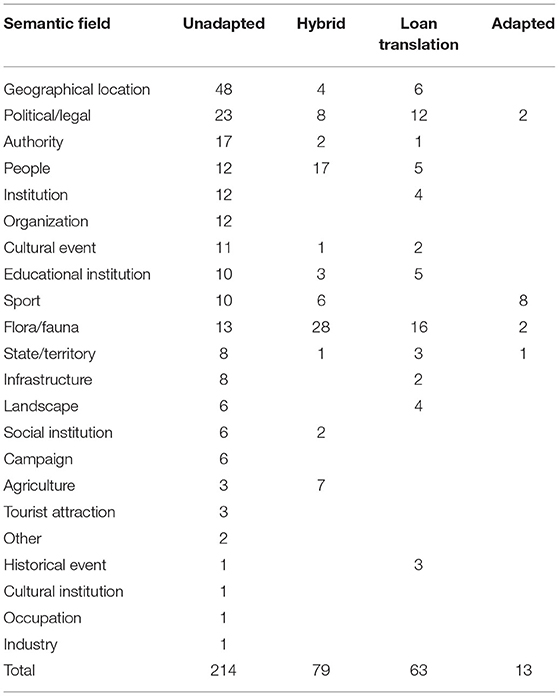

There are 22 semantic fields that I identified in the dataset. As shown in Figure 1, the most frequent (considered here to be those with a total token frequency of 50 or more) indicate a focus on place, and include names of states or territories (e.g., New South Wales, Queensland), landscape features (e.g., Margaret River, Uluru), and geographical locations (e.g., Tamarama Beach, The Entrance). This is followed by those anglicisms in politics and law (e.g., Labor-Partei “Labor Party,” High Court), references to people (e.g., Aussies, Crocodile Hunter), flora/fauna (e.g., King Billy-Kiefer “King Billy pine,” Box Jellyfish), and then sport (e.g., Cricket, Tour Down Under). A breakdown of semantic fields by borrowing type can be seen in Table 5, which indicates that the most common are unadapted borrowings (213 types), followed by hybrids (79 types), then loan translations (63 types) and adapted loans (14 types).

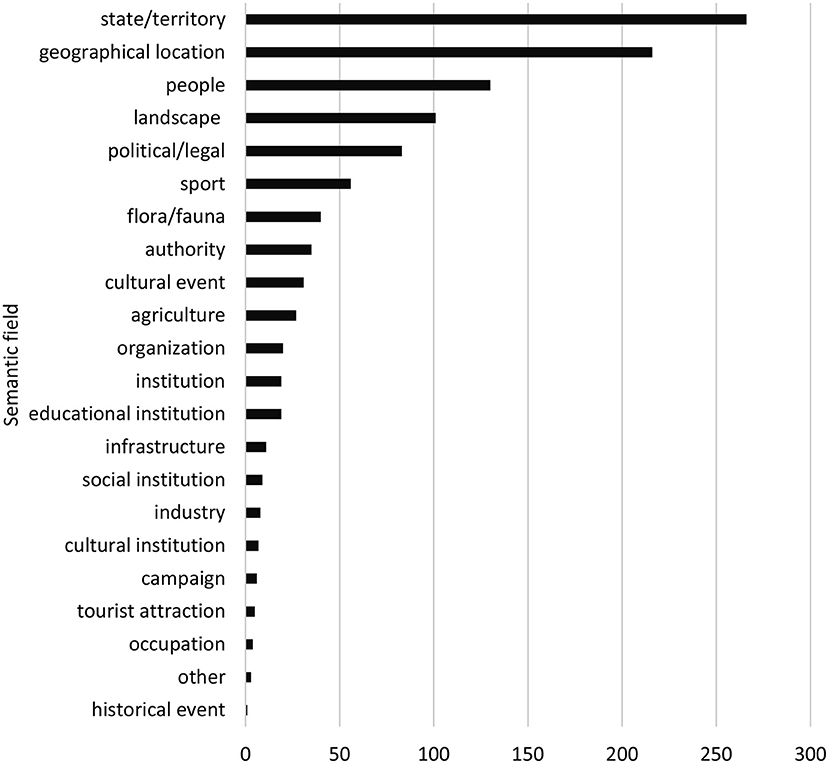

Focusing on unadapted anglicisms, as shown in Figure 2, there is a slight rearrangement in the order of semantic fields containing 50 or more tokens. Broadly, those lexical items belonging to the themes of place (e.g., states or territories, geographical location, and landscape) and society (e.g., people, politics, and sport) still dominate in the dataset. However, excluded from this list of semantic fields with 50 or more tokens is the field of flora/fauna. Here, there is a preference for hybridization and loan translation over unadapted borrowings. Those with simple descriptive titles, such Tasmanische Teufel “Tasmanian Devils” (14 tokens) and blassköpfige Schlange “pale-headed snake” (2 tokens) are more easily translated, negating the need for unadapted borrowing, whereas some animal names such as kangaroo are orthographically adapted (in this case to Känguru), while others, such as koala are left unadapted. Considering that there are 56 types of flora/fauna lexical items in the dataset and only 13 of them are unadapted reflects not only animal naming conventions, but may also suggest the intended audience for these lexical items are German speakers abroad via the dpa network, where clarity of meaning is preferred over preservation of the English label.

Code-Switching

The dataset includes four clear examples of code-switches. The first is an intersentential code-switch, acting as commentary, the second is written on a banner, the third is an indirect greeting in a quoted message on social media, and the fourth is a term of address in quoted speech. In three of the four cases, the code-switches appear to be a deliberate choice by the author for specific stylistic effects. The following shows each example of code-switching in the dataset, with the particular code-switched elements underlined here for emphasis, followed by an interpretation of its effect.

The first example of a code-switch occurs in an article reporting on the 61st annual ball of the German-Austrian Society in Cabramatta (Sydney).

(1) Und als Vorspeise mein Leibgericht: Hühnersuppe. Absolutely delicious. Zum Dessert dann Apfelstrudel und Eiscreme—wer kann diesem Menü wohl widerstehen? (Birgit Myrach, Issue 10, 2017)

[And for entrée, my favorite dish: chicken soup. Absolutely delicious. Then for dessert, apple strudel and ice cream—who can resist this menu?]

In this article, the local reporter, Birgit Myrach, provides an account of the evening's proceedings, listing prominent community members in attendance and, as shown here, describing the evening's fare. This code-switched text functions as a direct comment by the author in her otherwise all-German prose. Furthermore, it is not flagged in any way: The English adjective phrase is not presented in quotation marks or in italics, nor is any translation offered. This suggests an assumption that the readership is familiar enough with English to understand this comment. Unlike the other articles containing code-switches below, this one stands out as being attributed to a local author reporting on a local community event for a local audience.

The second example of code-switching appeared on a sign held up by crew members aboard the cruise ship Artania when leaving Fremantle Harbor, south of Perth.

(2) Das Schiff verabschiedete sich mit Hornsignalen, auf den Decks winkten Crewmitglieder den Menschen im Hafen zu. ≪Thank you Fremantle≫, war auf einem Transparent mit Herz zu sehen. (dpa, Issue 16, 2020)

[The ship bade farewell by blasting its horn, crewmembers waved to the people along the harbor. “Thank you Fremantle” could be seen on a banner along with a heart].

The German-operated ship had been docked in quarantine in March–April 2020 because of multiple COVID-19 cases on board, many of which required hospitalization. The city of Perth had organized for ~850 passengers and crew members to alight the ship and, under strict quarantine conditions, to board charted flights to Germany. The remaining 400 on board, mostly crew members, departed for Germany on the ship.

Similar to example (1), the recipient of the message is important, but instead of the reader of the newspaper receiving the written information, readers of the sign reported about within the article are significant. The code-switched text in (2), “Thank you Fremantle,” was intended for locals waving farewell to the cruise ship on the dock as it left port in Western Australia. Here, rather than using English to provide a commentary on the article's content, the unnamed dpa author gives an accurate portrayal of the sign's simple message that would not be as accurately purveyed had he/she translated the sign into German. Furthermore, most German speakers would arguably understand the phrase “thank you,” thus negating the need for a translation.

The third example of code-switching occurred in a message on the social media platform Twitter by Scott Morrison, the Prime Minister of Australia, in a tweet congratulating Boris Johnson on his re-election:

(3) ≪Sag G'day zu den stillen Briten von uns≫, fügte er hinzu und bezog sich damit auf die Unterstützer Johnsons. (dpa, Issue 50, 2019)

[“Say g'day to the quiet Britons for us,” he added, referring to Johnson's supporters].

Instead of the entire tweet being translated into the Standard German “Grüß den stillen Briten von uns” (literally “greet the quiet Britons from us”) or similar, the original greeting “g'day,” an abbreviated form of “good day,” is retained. The inclusion of the code-switch appears to be for stylistic purposes, that is, to provide the desired connotation intended in the English original form. In using this informal greeting, the prime minister depicts himself as being down-to-earth, friendly, and relaxed (positive qualities that are strongly associated with the stereotypical Australian character), especially when compared to the more formal variant. Using this casual greeting to the head of the British parliament also portrays the stereotypical Australian value of egalitarianism and as such, provides an excellent example of local color. However, at the same time, the effect of this casual greeting may be lost on many users of German outside Australia because it requires familiarity with Australian culture and its variety of English to understand the connotations evoked.

The fourth code-switch is the only one appearing in quoted speech. It is in an article containing various critiques of Australia's policy on energy production and the environment:

(4) “Prime Minister, sagen Sie das den schon 17 Ländern auf der ganzen Welt, die heute mehr als 90% ihres Stroms aus erneuerbaren Energien erzeugen,” bittet Professor Flannery. (Unattributed, Issue 42, 2018)

[“Prime Minister, tell that to the 17 countries around the world who already produce more than 90% of their power from renewable sources” requests Professor Flannery].

Here, retaining the address term Prime Minister within the translated quote, has the effect of providing a sense of local color by using the English title for the head of the Australian government. While translated equivalents of the title exist in German, such as Premierminister or Ministerpräsident, neither of those would represent the Australian parliamentary system as accurately as the English.

Overall, there are few instances of code-switching in the corpus. Out of those that do occur, only one, as shown in example (1) might be considered a true code-switch in the sense that it appears in a text that has presumably not been translated from English. While examples (2–4) are each unique in that they are from a handwritten sign directed toward local Australians, a written quote to an English speaker, and a spoken quote to an English speaker, respectively, they are all similar in that they are examples of code-switches appearing in translated texts. And as such, they appear to be more deliberate choices by the author as an indication of local Australian color, particularly (2) and (3) which are attributed to the dpa.

Six campaign slogans in the corpus form a particular subset of code-switches and all appear in articles written by dpa journalists. Therefore, it can be assumed that these authors must also consider readers outside Australia. All examples appear once only in the corpus, apart from that shown in (5) which appears twice in the same article. They are as follows:

(5) ≪Fly me to the Supermoon≫ (dpa, Issue 21, 2021)

- this is in reference to a campaign slogan for an airline offering chartered flights from Sydney out over the Pacific Ocean to get a better view of the blood moon and lunar eclipse appearing in May 2021;

(6) ≪Aboriginal Lives Matter≫ (dpa, Issue 23, 2020)

- this is a local variant of the Black Lives Matter movement;

(7) #aapneedsyou (AAP braucht Dich) (dpa, Issue 38, 2020)

- a hashtag with the aim of crowdsourcing funds to save the Australian Associated Press (AAP), which was in financial difficulty and under threat of administration;

(8) ≪Holiday Here This Year≫ (Urlaub hier dieses Jahr) (dpa, Issue 42, 2020)

- a tourism campaign slogan encouraging Australians to holiday within their own country;

(9) ≪pee, poo and (toilet) paper≫. Auf Deutsch: ≪Pipi, Kacke und (Toiletten-)Papier≫ (dpa, Issue 14, 2020)

- an awareness campaign on what does (and more specifically, does not) belong in sewerage systems; and

(10) ≪Save the Tasmanian Devil≫ (≪Rettet den Tasmanischen Teufel≫) (dpa, Issue 13, 2017)

- a program designed to prevent the Tasmanian Devil from dying out due to Devil Facial Tumor Disease.

An interesting feature of these campaign slogans is that (5) and (6) are not translated, whereas (7–10) are. Example (5) is a play on the song title Fly me to the Moon, popularized by many popular singers including Frank Sinatra, and thus, would appear to be familiar enough to the German-speaking audience abroad as to not require translating. Similarly, example (6), a local variant of the global Black Lives Matter movement, would undoubtedly be familiar with a German-speaking audience abroad as well (The English form Black Lives Matter slogan also appears twice in Issue 24, 2020). However, the remaining slogans are much more specific to the local context and are translated. These campaign slogans, as longer strings of text flagged with quotation marks and, in some cases, translations, clearly do not belong to the matrix language. As such, the sense of local color that they provide and as their translated forms appear to be for the benefit of those outside Australia who are reading the articles through the dpa network.

Finally, considering that prototypical code-switches are intended for plurilingual audiences, the untranslated code-switches as exemplified above indicate an expectation that the audience is proficient enough in English to understand them. Thus, these code-switches may be included as a stylistic device to add local color and specific nuance and meaning to the texts. However, these effects are diminished in those code-switches that are translated. Indeed, these may not be considered full code-switches as such because the apparent necessity of providing a translation assumes that the audience lacks the English proficiency to make sense of the original phrasal units. Therefore, the sense of local color, while still present, is no longer as strong because the assumption about reader proficiency appears to have changed.

Flagged Lexical Units

Multiple anglicisms appearing in the dataset are marked with quotation marks. For example, the anglicism Aussies appears twice flagged within the same issue, as shown in (11) and (12):

(11) Dieses Jahr aber sind die ≪Aussies≫ mit etwas anderem beschäftigt. (dpa, Issue 04, 2020)

[But this year, the Aussies are occupied with something else]

(12) Wie geht das Leben für die ≪Aussies≫ weiter? (dpa, Issue 04, 2020)

[How will life go on for the Aussies?]

However, in a separate issue, it is unflagged:

(13) “Ich frage für 40.000 gestrandete Aussies, die nicht nach Hause in ihr Land kommen können, nachdem sie seit zwölf Monaten ohne Unterstützung oder Essen oder auch nur ein Dach über ihrem Kopf leben” (Barbara Barkhausen, Issue 14, 2021)

[I am asking for 40,000 stranded Aussies who cannot come home to their own country after they have been living without support or food or even a roof over their heads for 12 months].

This excerpt here is from an article by local reporter Barbara Barkhausen and is not attributed to the dpa. Hence, it is a clear example of a local author writing for local readers and for whom Aussie is a common term. The remaining examples of flagged lexical units all appear in articles attributed to the dpa.

In some cases, complex flagging occurs. Not only orthographically marked, but also reformulated is the example of the surrounding region of Canberra, the nation's capital city:

(14) ≪Australian Capital Territorium≫ (ACT)—so heißt die Region um die Hauptstadt (dpa, Issue 05, 2020)

[“Australian Capital Territory” (ACT)—that is the name of the region around the capital city].

Indeed, example (14) could also be viewed as being triple marked because it appears in quotation marks, it is a partial loan translation (i.e., by translating the third element of the name from Territory to Territorium), and it is followed by an explanatory statement. That such marking occurs at all indicates a view from the outside, that is, from the point of view of a dpa article with an international audience in mind, because the local readership would not need such clarification.

Two forms of Tasmanian Devils appear in the corpus. There are two tokens flagged with double quotation marks and one token of the hypocoristic ≪Tassie Devils≫. Both the partial translation of Tassie-Teufel (2 tokens) and the loan translation Tasmanische Teufel (14 tokens) remain unflagged.

Two further examples of multiple flagging through quotation marks and as direct translation refer to two people treated as national heroes for particular acts of rebellion and defiance. They are Egg Boy (Issue 22, 2019) and Trolley Man (Issue 46, 2018). Egg Boy refers to Will Connolly, who broke an egg onto the head of Senator Fraser Anning who notoriously drew a connection between Muslim immigration and terror attacks. At first, only the direct translation ≪Jungen mit dem Ei≫ (literally “boy with the egg”) appears in the headline in quotation marks. Later in the same article, the anglicism appears flagged both with a preceding explanatory text and then is followed by the direct translation. Here, there also is the indication that the audience for this article is not limited to Australia, since the locational context, indicated by the preposition phrase “In seiner Heimat” “in his homeland” appears targeted to readers outside Australia:

(15) In seiner Heimat nennt man ihn ≪Egg Boy≫, den ≪Jungen mit dem Ei≫. (dpa, Issue 22, 2019).

[In his homeland he is called “egg boy,” the “boy with the egg”].

Similarly, Trolley Man is flagged multiple times by quotation marks as well as a loose translation. The nickname was given to a member of the public, Michael Rogers, who used a shopping trolley to prevent a knife-wielding terrorist from continuing his rampage through a busy pedestrian mall in Melbourne. In the headline, the nickname appears without any translation or explanation:

(16) Melbournes ≪Trolley Man≫—Ein Held muss vor Gericht (dpa, Issue 46, 2018).

[Melbourne's “Trolley Man” — A hero has to go to court].

Later, after several sentences explaining how the homeless man came to receive this nickname, the label appears again in quotation marks, but this time followed by a loose translation:

(17) Rogers wurde für seinen Einsatz als ≪Trolley Man≫ (der Mann mit dem Einkaufswagen) gefeiert. (dpa, Issue 46, 2018)

[Rogers was hailed for his actions as the “Trolley Man” (the man with the shopping trolley”)].

In addition to orthographical flagging, some lexical items receive multiple linguistic flags. For example, Australia Day occurs 10 times in the corpus. In addition to when it appears unflagged as Australientag, the following show some of the various flagging devices given to this item:

A definition (underlined here for emphasis) in the sentence following the term:

(18) … sollte es demnach auch zu den Feiern zum Australia Day am Samstag brütend heiß werden. Am Nationalfeiertag gedenken die Australier… (dpa, Issue 04, 2019)

[… it should therefore also be scorching hot for the celebrations for Australia Day on Saturday. On the national public holiday, the Australians commemorate …].

A definition preceding the term within the same sentence:

(19) Mit Partys und Protesten hat Australien am Freitag seinen Nationalfeiertag begangen, den Australia Day. (dpa, Issue 04, 2018)

[On Friday, Australia celebrated its national public holiday, Australia Day, with parties and protests].

A longer explanatory text following the term, providing further situational context of the article:

(20) Am Sonntag war Australia Day—ein umstrittener Feiertag in Australien, weil er zum Ärger der Ureinwohner an die britischen Siedler erinnert. (dpa, Issue 04, 2020)

[Sunday was Australia Day—a controversial public holiday in Australia because, much to the anger of the Indigenous people, it is a reminder of the British settlers].

With an explanation in a new sentence after the term:

(21) Jetzt also der Australia Day. Er erinnert daran, wie die Briten 1788 in Sydney landeten, um dort eine Kolonie für Häftlinge zu errichten. (dpa, Issue 04, 2020)

[And now Australia Day. It commemorates how the British landed in Sydney in 1788 to establish a colony for convicts].

Triple-flagging with quotation marks followed by a translation, and then explanation:

(22) Am ≪Australia Day≫ (Australientag) erinnert das Land an die Ankunft der britischen Ersten Flotte 1788, mit der die europäische Besiedlung des fünften Kontinents begann. (dpa, Issue 19, 2017)

[On “Australia Day” (Australia Day), the country commemorates the arrival of the British First Fleet in 1788, with which the European colonization of the fifth continent began].

Multiple types of flagging may appear on lexical items that are repeated within the same article. For example, there are three tokens of ≪Box Jellyfish≫, a highly venomous jellyfish (chironex fleckeri) found in the tropical waters of Australia, appearing in the same article. When it is introduced in the article headline, it is marked with quotation marks and a definition:

(23) ≪Box Jellyfish≫—Hochgiftige Qualle tötet Jugendlichen in Australien (dpa, Issue 09, 2021)

[“Box Jellyfish” — Highly venomous jellyfish kills boy in Australia].

only to be translated in the first sentence of the article as the unflagged hochgiftige Würfelqualle:

(24) Im Norden Australiens ist ein Jugendlicher durch den Stich einer hochgiftigen Würfelqualle ums Leben gekommen. (dpa, Issue 09, 2021)

[In northern Australia, a youth was killed by a highly poisonous box jellyfish].

The third time the sea creature is mentioned, it is followed with Seewespe “see wasp,” a translation of an alternative, but less common, English name for box jellyfish, in parentheses:

(25) Der 17-Jährige sei vor zehn Tagen beim Schwimmen an der Landzunge Cape York von den Tentakeln eines sogenannten Box Jellyfish (Seewespe) getroffen worden. (dpa, Issue 09, 2021)

[The 17-year-old was touched by the tentacles of a box jellyfish (sea wasp) 10 days ago while swimming on the Cape York headland].

No longer requiring explanation or translation the final time it is mentioned, it remains unflagged inside a direct quote:

(26) ≪Wir sehen in unseren Gewässern sowohl Box Jellyfish als auch andere Quallenarten, die das Irukandji-Syndrom verursachen≫, warnten die Behörden. (dpa, Issue 09, 2021)

[We see both box jellyfish and other species of jellyfish that cause Irukandji syndrome in our waters,” the authorities warned].

The above examples show that flagging of Australia-related anglicisms is prevalent in articles written by journalists for the dpa. Analyzing the examples of flagging in the corpus reveals that a single word may appear in one article: (a) within quotation marks, (b) within quotation marks and in translated form, and (c) within quotation marks, in translated form, and accompanied by an explanation. The inclusion of flagged lexical units and codeswitches in the dpa articles may have the effect of placing local readers outside the English-speaking mainstream, as if they were peering in on a culture and society that they are not familiar with or part of, while for international readers, these flagging devices may provide local color and, in some cases, may assist in clarification of unfamiliar terms.

Conclusion

While the tradition for anglicism research has often been to use the print media published for German speakers living in German-speaking countries as a data source, this paper has applied a different approach by exploring the way that Australia, its icons, culture, institutions, and way of life have been portrayed using anglicisms in an Australian-published German-language newspaper.

It appears that a complex situation concerning the target readership influences the way Australia is portrayed in Die Woche, particularly when regarding the frequency of unadapted loans, loan translations, and loan renditions used to represent the broad themes of place and society. Because the newspaper under consideration here is published in Australia, there would be the assumption that its target audience of German speakers living there is quite familiar with Australian English and is also acquainted with Australian concepts, geography, and society, etc. This, then suggests that there should be little need for loan translations or loan renditions, or even flagging of English lexical items, meaning that the number of unadapted anglicisms appearing within the corpus would be higher than attested. Nevertheless, only slightly more than half of all tokens in the dataset are in their original English form. While this oscillation between unadapted forms and adapted forms (including loan translations and loan renditions) adds lexical variety to the articles, there was a surprisingly high incidence of othering via the use of flagging devices on these unadapted lexical items. This has the effect of drawing the readers' attention to these items and marks them as being outside the recipient language.

Many articles within the newspaper are attributed to the dpa which reaches an international readership beyond the newspaper itself, including monolingual speakers of German in Europe. This would account for the relatively high number of loan translations and flagged lexical units and phrases than that which would be expected in a local publication for German speakers living in Australia. This would also explain the frequent appearance of the lexeme Aborigine, and its various hybridized forms, which has undergone semantic shift to become taboo in Australian English. While the inclusion of unadapted Australia-related anglicisms provides local color imagery, it risks a lack of understanding on the part of readers abroad who may be less familiar with English lexical items denoting place names, geographical locations, etc., within Australia. This, then, appears to create the need for many of the loan translations and/or flagging devices seen in the dataset.

The result of this, at times disjointed, combination of articles produced by local reporters for a local audience and articles produced for an international audience can sometimes lead to an othering effect upon the local reader, removing him or her from mainstream English-speaking Australia society and positioning him or her as an outsider looking in. Regarding this paper, it unfortunately leads to an unclear picture about the actual use of Australia-related anglicisms in German as used in Australia. To overcome this, future research in this area would benefit from using a dataset derived from a larger corpus, while at the same time, narrowing the focus by including only those articles specifically intended for a local audience written by local journalists. This would then allow for a comparison with a similarly large corpus sourced from the German print media, to give a better indication of how anglicisms are used in Australian German to represent concepts, phenomena, and cultural and societal artifacts related to Australia.

Data Availability Statement

Non-copyrighted data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation. The copyrighted data analyzed in this study was obtained from https://www.diewoche.com.au. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

I would like to offer my sincerest gratitude to the publishers of Die Woche, Australia-News.De Pty Ltd., in particular editors Dieter Herman and Marion Althaus, for providing me with the pre-published articles in .txt format that I used to compile the corpus for this study. Also, I would like to express my great appreciation to the reviewers and editors for providing such highly valuable suggestions, advice, and encouraging comments on an earlier draft of this article. Lastly, I wish to thank the other presenters and audience at the LCTG5 conference in Klagenfurt in September 2021 for their inspiration and motivation.

Footnotes

References

“bush, 1”. (2004). In Australian Oxford Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Available online at: https://www-oxfordreference-com.ezproxy.newcastle.edu.au/view/10.1093/acref/9780195517965.001.0001/m-en_au-msdict-00001-0007658 (accessed February 27, 2022).

“bush, n. 1”. (2021). OED Online. Oxford University Press. Available online at: https://www.oed.com/view/Entry/25179?rskey=Mm9NHe&result=1&isAdvanced=false (accessed October 29, 2021).

Adler, M. (2004). Form und Häufigkeit Der Verwendung von Anglizismen in Deutschen und Schwedischen Massenmedien. (Dissertation), Friedrich-Schiller-Universität, Jena (Germany).

Burmasova, S. (2010). Empirische Untersuchungen der Anglizismen im Deutschen am Material der Zeitung Die Welt (Jahrgänge 1994 und 2004). Bamberg: University of Bamberg Press. doi: 10.26530/OAPEN_368157

Carstensen, B. (1965). Englische Einflüsse auf die Deutsche Sprache nach 1945. Heidelberg: Carl Winter Universitätsverlag.

Carstensen, B., and Busse, U. (2001). Anglizismen-Wörterbuch. Der Einfluß des Englischen auf den Deutschen Wortschatz nach 1945. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

Clyne, M. (2003). Dynamics of Language Contact. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511606526

Die Woche Australien (2017). Available online at: https://www.diewoche.com.au/geschichte-der-zeitung/ (accessed August 10, 2021).

Donalies, E. (1992). Hippes hopping und toughe trendies. über “(neu)modische”, noch nicht kodifizierte anglizismen in deutschsprachigen female-yuppie-zeitschriften. Deutsche Sprache 2, 97–110.

Fiedler, S. (2012). “Der elefant im raum. The influence of English on German phraseology,” in The Anglicization of the European Lexis, eds C. Furiassi, V. Pulcini, and F.R. Gonzaléz (Amsterdam: John Benjamins), 239–259. doi: 10.1075/z.174.16fie

Gardner-Chloros, P. (2010). “Contact and code-switching,” in The Handbook of Language Contact, ed R. Hickey (Somerset: John Wiley & Sons), 188–207. doi: 10.1002/9781444318159.ch9

Görlach, M. (2001). A Dictionary of European Anglicisms: A Usage Dictionary of Anglicisms in Sixteen European Languages. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gottlieb, H. (2005). “Anglicisms and translation,” in In and Out of English: For Better or Worse, eds G. Anderman, and M. Rogers (Clevedon: Multilingual Matters), 161–184. doi: 10.21832/9781853597893-014

Gottlieb, H. (2020). Echoes of English: Anglicisms in Minor Speech Communities - with Special Focus on Danish and Afrikaans. Berlin: Peter Lang. doi: 10.3726/b15937

Gottlieb, H., Andersen, G., Busse, U., Mańczak-Wohlfeld, E., Peterson, E., and Pulcini, V. (2018). Introducing and developing GLAD - the global anglicism database network. ESSE Messen. 27, 4–19.

Hunt, J. W. (2019). Lexical hybridization of English and German elements: a comparison between spoken German and the language of the German newsmagazine Der Spiegel. Stud. Linguist. Univer. Iagellon. Cracovien. 136, 107–120. doi: 10.4467/20834624SL.19.010.10605

Knospe, S. (2014). Entlehnungen oder Codeswitching? Sprachmischungen mit den Englischen im Deutschen Printjournalismus. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.

Korff, J. (2020). What is the Correct Term for Aboriginal People?. Available online at: https://www.creativespirits.info/aboriginalculture/people/how-to-name-aboriginal-people (accessed September 4, 2021).

Langer, N. (1996). Anglizismen in der deutschen Pressesprache. Untersucht am Beispiel von den Wirtschaftsmagazinen 'CAPITAL' und 'DM'. Wettenberg: VVB Laufersweiler.

Matras, Y. (2009). Language Contact. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511809873

Maude, A. (2018). Geography and powerful knowledge: a contribution to the debate. Int. Res. Geogr. Environ. Educ. 27, 179–190. doi: 10.1080/10382046.2017.1320899

Myers-Scotton, C. (1992). Comparing codeswitching and borrowing. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 13, 19–39. doi: 10.1080/01434632.1992.9994481

Onysko, A. (2007). Anglicisms in German: Borrowing, Lexical Productivity, and Written Codeswitching. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. doi: 10.1515/9783110912173

Onysko, A. (2019). “Processes of language contact in english influence on German,” in English in the German-Speaking World, ed R. Hickey (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 185–207. doi: 10.1017/9781108768924.010

Onysko, A., and Winter-Froemel, E. (2011). Necessary loans - luxury loans? Exploring the pragmatic dimension of borrowing. J. Pragmat. 43, 1550–1567. doi: 10.1016/j.pragma.2010.12.004

Pflanz, M-L. (2014). Emprunt lexical: existe-t-il une typologie de la phase néologique? Neologica. 8, 157–183. doi: 10.15122/isbn.978-2-8124-2999-6.p.0157

Plümer, N. (2000). Anglizismus - Purismus - Sprachliche Identität: Eine Untersuchung zu den Anglizismen in der Deutschen und Französischen Mediensprache. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.

Poplack, S. (1993). “Variation theory and language contact,” in American Dialect Research: Celebrating the 100th Anniversary of the American Dialect Society, 1889–1989, ed D. R. Preston (Philadelphia, PA: John Benjamins Publishing Company). doi: 10.1075/z.68.13pop

Poplack, S. (2018). Borrowing: Loanwords in the Speech Community and in the Grammar. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/oso/9780190256388.003.0004

Pulcini, V., Furiassi, C., and Rodríguez González, F. (2012). “The lexical influence of english on European languages: from words to phraseology,” in The Anglicization of European Lexis, eds C. Furiassi, V. Pulcini, and F. R. González (Amsterdam: John Benjamins), 1–24. doi: 10.1075/z.174.03pul

Saugera, V. (2012). How english-origin nouns (do not) pluralize in French. Lingvist. Investigat. Int. J. Linguist. Lang. Resourc. 35, 120–142. doi: 10.1075/li.35.1.05sau

Schaefer, S. J. (2021). English on air: novel anglicisms in German radio language. Open Linguist. 7, 569–593. doi: 10.1515/opli-2020-0174

Sharp, H. (2007). Swedish–English language mixing. World Engl. 26, 224–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-971X.2007.00503.x

Winter-Froemel, E. (2021). “Appealing though nebulous? introducing the concepts of accessibility and usability to loanword research [Conference presentation],” Language Contact in Times of Globalization 5 (LCTG 5). Klagenfurt: The University of Klagenfurt.

Yang, W. (1990). Anglizismen im Deutschen: Am Beispiel Des Nachrichtenmagazins Der Spiegel. Tübingen: Max Niemeyer. doi: 10.1515/9783111676159

Zenner, E., Speelman, D., and Geeraerts, D. (2012). Cognitive Sociolinguistics meets loanword research: measuring variation in the success of anglicisms in Dutch. Cogn. Linguist. 23, 749–792. doi: 10.1515/cog-2012-0023

Keywords: anglicisms, Australia, English, German, borrowing, language contact, code-switching (CS)

Citation: Hunt JW (2022) Snakes, Sharks, and the Great Barrier Reef: Selected Use of Anglicisms to Represent Australia in the Australian German-Language Newspaper, Die Woche. Front. Commun. 7:818837. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2022.818837

Received: 20 November 2021; Accepted: 13 April 2022;

Published: 20 May 2022.

Edited by:

Peter Siemund, University of Hamburg, GermanyReviewed by:

Sarah Josefine Schaefer, University of Nottingham, United KingdomSebastian Knospe, Polizeiakademie Niedersachen, Germany

Copyright © 2022 Hunt. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jaime W. Hunt, amFpbWUuaHVudEBuZXdjYXN0bGUuZWR1LmF1

Jaime W. Hunt

Jaime W. Hunt