- Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, Universiti Brunei Darussalam, Bandar Seri Begawan, Brunei

This paper focuses on aspects of language contact, specifically Malay and English in the domain of social media. Key components of the theoretical framework are world Englishes being by definition code-mixed varieties, and the complementary notions of nativization (of English) and englishization (of Malay, in this case). Texts examined and analyzed are from Whatsapp chats and groups, with the consent of all participants, and from public social media sites in the Malay world, mostly Negara Brunei Darussalam (henceforth Brunei) but also Malaysia. Brunei is known for having a very high percentage of social media use per head of population, with especially high levels of use of Instagram and Facebook, as well as discussion forums such as Reddit. In their social media interactions Bruneians and Malaysians have a range of language choices, from monolingual English to monolingual Malay, and varying degrees of code-mixing or translanguaging. Many Bruneians and Malaysians are multilingual, and thus may have more than two languages as resources to draw on. Analysis of threads of discussion forum postings on the same topic demonstrate the multilingual repertoire of participants, for whom any of the available language choices are unmarked. This is in part owing to the use of English as one medium of education alongside Malay: consistently in Brunei since 1985, inconsistently in Malaysia since 1963. The conclusion of the paper raises two questions: whether it is valid to posit the language of social media as a new variety comprising both local and global influences and inputs, and whether social media is a driver of change in varieties of English in Southeast Asia.

Introduction

Bearing in mind the title and the importance of this research topic, “Englishes in a Globalized World: Exploring Contact Effects on Other Languages,” it is necessary at the outset to state that this article is not just about Englishes. It attempts to highlight the salience of the “other languages.” World Englishes are by definition code-mixed or translanguaging varieties (McLellan, 2020), and this article draws on the kueh lapis (Malay, “layer cake”) analogy used by Haji-Othman and McLellan (2014) with reference to Brunei. This was developed as a means of showing that English, in Brunei and Malaysia, as elsewhere in multilingual societies, is just one language among many, akin to the many layers of a layer cake, a delicacy in Borneo. Haji-Othman (2012, p. 175–190) sums up the issue succinctly in the Brunei context in his chapter entitled “Is it always English? Dueling aunties in Brunei Darussalam,” which aptly envisages English and Malay as two dueling aunties competing for influence. The complementary notions of nativization (of English) and englishization (of local languages), developed by Kachru (2005, p. 113–117) are adopted as a basis for discussion of features of Malay/English language contact phenomena. The interconnected notions of code switching, code mixing, language alternation and translanguaging are outlined below.

The Context: Brunei

Negara Brunei Darussalam (henceforth Brunei) is a small Malay Islamic Sultanate located on the north-western coast of the island of Borneo, with a coastline of about 160 km on the South China Sea. It is surrounded on the other three sides by the East Malaysian state of Sarawak, which also divides the Temburong District from the other three Brunei administrative districts, Brunei-Muara, Tutong and Belait. The total land area is 5,675 km2. The population of about 453,600 (http://www.deps.gov.bn/SitePages/Population.aspx) is concentrated along a narrow coastal strip and consists of Brunei Malays (66%), Chinese (11%), other indigenous groups (3%), with the remainder (20%) comprising other Borneo-indigenous groups such as Iban, and a still substantial number of expatriate workers who are temporary residents. Brunei's core national philosophy and ideology is Melayu Islam Beraja (Malay Islamic Monarchy). The Malay component refers to the official language, Bahasa Melayu (standard Malay), as designated in the 1959 Constitution, although the main lingua franca and the default language for everyday communication is the distinctive Brunei variety of Malay. Since 1985, 1 year after the resumption of full independence, Brunei has had a bilingual Malay and English language-in-education policy, with some subjects taught through the medium of (standard) Malay, and others, including Science and Mathematics, taught in English-medium. Under the current Sistem Pendidikan Abad ke-21 (“Education System for the twenty-first century”) English-medium operates right from pre-school through all levels (Haji-Othman et al., 2019). Hence most Bruneians under 35 years of age and educated to secondary-level or beyond are proficient in both standard and Brunei Malay, and in English (Goode, 2020).

The Context: Malaysia

Malaysia comprises the Malay Peninsula, bordering Thailand on the north and Singapore in the south, and two states on the island of Borneo, Sabah, and Sarawak. Based on the 2010 census, the total population of Malaysia was 28.3 million, with 20% of the population living in Sabah and Sarawak (dosm.gov.my). The ethnic breakdown in Malaysia is 67% Malays and indigenous groups, 25% Chinese, 7% Indians (7.3%), and 1% classified as others (e.g., Malaysians with Portuguese or Dutch ancestry). In Peninsular Malaysia, Malays make up 63% of the population (dosm.gov.my) while the indigenous groups, known as Orang Asli, comprise ~0.7% of the population (https://www.jakoa.gov.my/data-terbuka-sektor-awam/). In East Malaysia, the Kadazan make up 26% of Sabah's population, while the Iban comprise 30.3% of the total population in Sarawak (dosm.gov.my). The language landscape in the public sector, including education, began to shift upon independence, which was first granted to the Malay Peninsula, Malaya, in 1957. Malay (Bahasa Malaysia) was declared as the national language (Article 152 of the Federal Constitution of Malaysia, 1963) as a means of promoting and creating a common national identity for the new nation which then comprised the Malay Peninsula, Sabah and Sarawak, and Singapore. Singapore left the Federation in 1965. At independence, there were schools with different mediums of instruction and curricula. Following independence, Malay began to replace English in government administration and public education. This process continued until the 1990s, when Science and Technology degree programmes, including Medicine, reverted to being taught in English-medium. In 2001 Malaysia reverted to English-medium for Science and Mathematics, then in 2009 this decision was reversed yet again, on mainly political, not educational grounds, and Malay-medium was reintroduced. Currently a “Dual Language Programme” is in place, allowing some schools a measure of choice as to medium of education for Science and Mathematics, including for public examinations. The changes in policy have done little to redress the rural-urban imbalance: in cities and large towns English functions as a second language; in rural areas English is effectively a foreign language, little used outside school classrooms.

Along with neighboring Southeast Asian nations Singapore and the Philippines, Brunei and Malaysia are categorized as “outer-circle” in Kachru's (2005) Three Circles model of world Englishes, since English has many intranational functions and both have distinct and well-described varieties of English, which are used between Bruneians and between Malaysians at varying levels of formality. It is beyond the limited scope of this article to give full descriptions of the linguistic and discoursal features of Brunei and Malaysian Englishes: for these, readers may refer to Deterding and Salbrina (2013) for Brunei English, and to Azirah and Tan (2012), among many other studies, for Malaysian English.

Social Media In Brunei And Malaysia

Brunei is among the nations with the highest proportion of internet connection to its population with 95%. Of these 99% are active social media users (Kemp, 2021a). Among the most popular platforms are WhatsApp, Instagram and the Brunei Subreddit discussion forum. Wood (2016) highlights the importance of social media platforms for the development of Brunei English, owing to their popularity among younger bi- and multilingual Bruneians. This trend has become more pronounced since early 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic first reached Brunei, necessitating lockdowns, restrictions on travel, and working and studying from home. This has led, in Brunei and Malaysia as elsewhere, to even greater reliance on social media. As “unregulated spaces” (Sebba, 2009), publicly available social media platforms offer an opportunity to examine emerging and shifting patterns of language choice and use.

Social media penetration and use in Malaysia is also high: there are 84.2% internet users and 86% social media users in the nation's population of 32.57 million (Kemp, 2021b). Whatsapp, Facebook and Instagram are among the most popular social media platforms in both countries.

Theoretical And Analytical Frameworks Adopted

In the field of World Englishes (WEs), Kachru's (2005) interrelated notions of “nativization” of English and “englishization” of local languages are highly relevant to Brunei and to Malaysia. Kachru regards these as “two Janus-like faces of language contact situations involving English” (p. 135). These form the basis for discussion of Malay-English language contact in social media texts. Language contact affects the phonology, syntax, discourse and lexis of the languages concerned, both historically and even more so in the present time with the expanding affordances of social media. The insights of Makoni and Pennycook (2007, 2012) on disinventing and reconstituting languages, of Schneider (2014), on the evolutionary dynamics of WEs, and Schneider (2016) on hybrid Englishes, have influenced my views about WEs being by definition mixed codes (McLellan, 2020). Saraceni (2020, p. 716–717), notes that monolingual views of language and communication are challenged and lack relevance in Asian contexts, where boundaries between languages are fluid: fixed and bounded ideas of “native” languages, first, second and foreign languages are less applicable. According to Heryanto (2007, p. 43), the term “language” itself is not readily applicable in Southeast Asia, as it is not equivalent to the Malay term bahasa, which derives from the Sanskrit bhāşā and has a broader connotational range comprising culture, politeness, upbringing and education.

With reference to the study of language use in social media, especially in multilingual contexts, Seargeant and Tagg (2014, p. 2) observe that “online social media are having a profound effect on the linguistic and communicative practices in which people engage, as well as the social groupings and networks they create.”

Code Switching/Code Mixing/Language Alternation/Translanguaging?

Terminology in this field is a fraught and contentious area. It would be a fallacious oversimplification to claim that the terms are interchangeable, and arguing the merits and limitations of each would detract and distract from the main purpose of this article. Having used the term “language alternation” (henceforth LA) in McLellan (2005), I continue using it here, but am aware that translanguaging has gained credence in recent years and has outgrown its original domain, the analysis of teacher and student interaction in multilingual classroom contexts (Garcia and Li, 2014; Li, 2018, 2019).

With specific reference to multilingual online discussion forums such as Kytölä (2012) offers valuable insights on methods of both text selection and analysis, including the importance of going beyond the surface features of discussion forum texts such as LA and covering “naming (one's screen persona), heading (discussion topics), bracketing,….., slogans aphorisms, signatures” (Kytölä, 2012, p. 122).

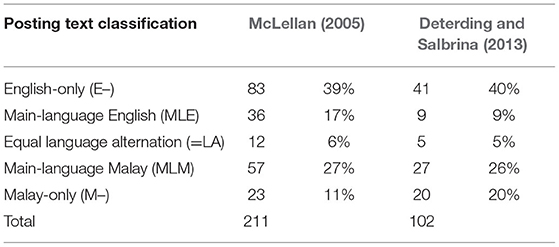

As an analytical framework, the classification of social media texts into five categories, used by McLellan (2005), and subsequently by others (Deterding and Salbrina, 2013; ‘Aqilah, 2020) is adopted for initial quantitative analysis. This aims to establish the frequency of LA as against monolingual English and monolingual Malay social media texts:

• monolingual English (E–)

• main language-English with some Malay (ML-E)

• equal language alternation of Malay and English (=LA)

• main language-Malay with some English (ML-M)

• monolingual Malay (M–).

It is axiomatic that monolingual texts are of equal interest and importance to texts which show a measure of LA. The temptation to label either monolingual texts or texts showing LA as “marked” or “unmarked” is therefore resisted, since the Bruneian and Malaysian text producers may choose any of these five, confident in the knowledge that they will be intelligible to their readers or interlocutors. Table 1 shows the percentage of texts in the five categories in the corpus analyzed by McLellan (2005), and in a comparable corpus analyzed by Deterding and Salbrina, 2013, both corpora being collected from Brunei public discussion forums.

From the figures in Table 1, from McLellan (2005), there is a slight predominance of English over Malay as the choice for the main language, 56.4–37.9%. In terms of monolingual against mixed-language postings there is a near even split, 106 E- and M-, as against 105 showing some measure of alternation between languages. On the basis of the findings outlined in Table 1, the presence of some degree of LA is the norm for ML-Malay postings, whereas monolingual English is the norm for ML-English postings (McLellan, 2009). The figures obtained in the later study by Deterding and Salbrina (2013) demonstrate largely similar patterns.

Whilst lexical features of LA are perhaps the most evident surface feature for analysis using this framework, grammatical congruence and non-congruence between English and Sebba (1998) are also key aspects of any analysis of LA patterns. As discussed by McLellan (2009, p. 6), there are three major areas of morphosyntactic non-congruence:

• Noun phrase structure

• Pluralization of nouns

• Verb inflections.

English noun phrases have normally modifier-head constituent order (“my red car”), whilst in Malay, including Brunei Malay, the default order is head-modifier (“kereta merah saya”). In lines 1 and 3 of example (5) below, “abis bat” and “habis bat” (“dead battery”) demonstrate the choice of English head-modifier order in the mixed noun phrase. In other instances the Malay order is found.

There is also non-congruence in how noun pluralization is marked: bound morpheme -s in English, reduplication of the noun in Malay (bunga-bunga, “flowers”) if plurality is not evident from the context. Again, in mixed noun phrases either the English or the Malay pattern may occur: the English plural is retained on “others” in the mixed sentence in example (1)1:

But in (2), Malay reduplication is used for the English noun:

Also found, though less often, is the use of the English -s plural suffix on Malay nouns.

Malay verbs, unlike English, do not have morphological suffix inflections marking tense, voice and aspect. Instead these are marked adverbially. Text (3) from is a mixed sentence in which “kana” is the passive voice marker.

This observes phrase structure rules of both English and Malay. Elsewhere in mixed verb phrases uninflected English verb base forms may be found, as in example (4):

This shows dominance of Malay syntax through the non-appearance of the English -ed past participle marker.

These examples of morphosyntactic congruence and non-congruence show how non-congruence can be resolved by bilingual mixed text producers, illustrating the interface and interaction between Malay and English in social media texts.

Analysis And Discussion Of Examples

Brunei: Whatsapp

‘Aqilah (2020) compares WhatsApp two-party chats with multi-party groups, showing that patterns of alternation between Brunei Malay and English are similar to those found in face-to-face spoken interaction. She received the informed consent of all chat and group participants, and found a predominance of monolingual messages in both chats (64.8%) and in groups (73.2%), but a significant minority of messages with some LA. Example (5) is from a group chat between four participants:

Whatsapp chats are asynchronous, but ‘Aqilah is able to establish, through referring to time stamps, that this and similar interactions occurred with minimal intervals between turns, hence the group chat resembles face-to-face conversation. Intrasentential LA is evident in all the four messages, in spite of their brevity, and both languages contribute to the grammar and to the meaning. The conversation is designated = LA, with 13 words of Malay and 11 English. This short text serves as an example of Brunei English in a social media context. It shows informal features known to occur across social media worldwide, namely sentence fragments and abbreviations in both Malay (“mcm,” macam, like; “ckp,” cakap, say) and English (‘Dunno'). The repeated Malay adjective occurs once with Brunei Malay spelling (‘rusak'), reflecting Bruneian pronunciation, and three times with standard Malay spelling (‘rosak'). Likewise there is one token of ‘abis' (Brunei Malay) and one of the standard form ‘habis' (finish(ed)).

Brunei: The Brunei Subreddit

The Brunei Subreddit (https://www.reddit.com/r/Brunei/) is a public discussion forum. It is available for all to read, but requires a username and password for those posting messages. As of 3 June 2022 it has 43,000 members, 8% of the nation's total population. Formerly the community (site managers) expected postings to be in English in the “random” discussion threads opened three times per week, but there has been an observable move toward higher frequency of use of Brunei Malay and of Malay-English LA in the past year, although the majority of postings are still in English-only. Every Monday, though, a thread “Lakastah bekurapak dalam Bahasa Melayu pada hari Isnin” (‘Let's talk in Malay on Mondays') is opened. The use of Malay is strictly observed in this thread, in line with the warning (in English), “This is a thread to practice your Malay language, and posts not following this format will be removed/downvoted.”

In code-mixed Brunei social media texts, the predominant pattern is standardized English alternating with Brunei Malay, as demonstrated in this example (6) from a posting in the Brunei Subreddit from 2019.

Text (6) is mainly Malay (ten words), with seven words of English. It is classified as equal language alternation (=LA), since both languages contribute to both the grammar and the lexical content.

Thus, although Bruneians predominantly choose to use English in social media, this is not to the exclusion of Brunei Malay. Hayani Nazurah (2021) finds that, in contrast to her corpus of Brunei Subreddit postings where English-only predominates, her corpus of 59 postings from the Brunei FM Facebook forum are 59% main-language Malay (ML-M) and 23% monolingual Malay (M-).

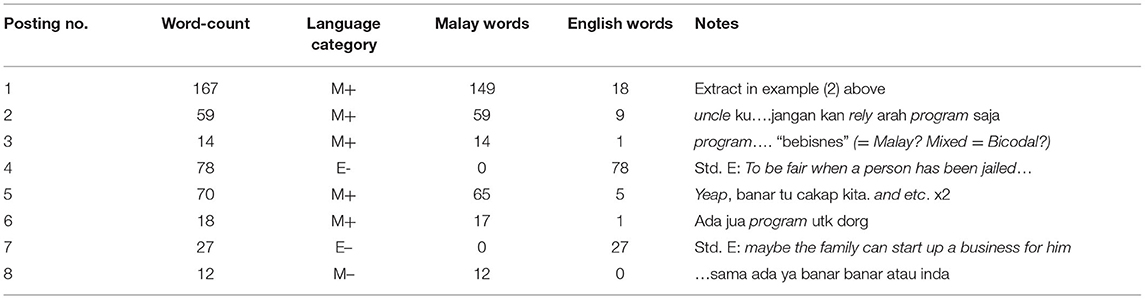

Table 2 shows an analysis of the thread from which example text (2) is taken, a discussion on the topic of employment of former prisoners.

The thread consists of eight postings, with four of the five language categories represented. Postings 4 and 7 are in monolingual English (E-) with no Malay, and posting 8 is in monolingual Malay (M–). The other five are in main-language Malay (M+) with some English insertions. The eight postings are from six different posters, as is evident from their Reddit nicknames (not given here for ethical reasons). One of those who posted twice used the same language choice, M+, for postings 1 and 5; the other used M+ in posting 3 and M– in posting 8. However, the English lexemes in posting 3, as noted in Table 2, are questionable: “program” is frequently used in Malay; “bebisnes” can be viewed as a case of intra-word mixing, a bicodal word, as it has the Malay actor-focus prefix “be-” with the English-derived root word “bisnes” (business), showing modification to comply with Malay orthography, which is phonemic. The issue of words crossing from one language to another is discussed below in the section on englishization.

The analysis of threaded discussion forum postings, in which the participants use different language choices, demonstrates that they are not constrained in the choices they make, as they are aware that any of the five shown in Tables 1, 2 are fully intelligible. But the postings with LA will not be intelligible to anyone not proficient in Brunei Malay, hence although the Brunei Subreddit is open-access and free for anyone world-wide to read, few if any non-Bruneians are part of the online community who read this Subreddit, and even fewer non-Bruneians post messages on it.

Examples (7) and (8) are taken from Brunei Subreddit postings in Brunei English showing LA. (7) is classified as main-language English, E+:

Example (7) here demonstrates LA in single Malay nouns within an English grammatical frame, whereas in (8), as in example (6), both Malay and English contribute to both the grammar and to the lexis, and this text is therefore =LA.

In example (9), from Hayani Nazurah (2021), the English phrasal verb ‘give up' is written as “gibap”:

Pronunciation spellings such as “gibap” here, and also “bisnes,” discussed above and in section analysis and discussion of examples below, occur often, and demonstrate the affinity of social media text with spoken interaction, in which such forms also occur.

Brunei: Instagram

According to Kemp (2021a), Instagram (IG) is the fifth most used social media platform globally, and the platform's potential advertising audience is 70.5% of the total population of Brunei aged 13 or over. Studies have been conducted of language use on IG by government ministries: Muhammad Nabil (2021) analyzed IG use by three Brunei government ministries, Education (Islamic), Religious Affairs and Health, in terms of their language use, including responses by the Brunei public. For Religious Affairs all the IG communications are announcements in Malay or Arabic, and there are no responses. The Education and Health Ministries use both Malay and English for announcements and media releases, and both languages are found in responses, reactions and queries to these. Since the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic the Ministry of Health's IG communications have taken on greatly increased importance, with daily briefings and media conferences chaired by the Minister of Health along with other ministers, at which both Malay and English are used, often with LA.

In a study of commercial advertising and customer responses on IG in Brunei, Diyanah Maimunah (2021) found that English was the preferred language by advertisers, although some included LA or were in Malay only. In an online survey she conducted, young Bruneian IG users aged 18–26 reported a preference for mixed Malay and English when responding to IG advertisements, assuming that any of the five code choices would be acceptable and effective. She gives an example of an E+ advertisement with only one word of Malay by Stack, a local burger restaurant, which generated a higher number of responses in Brunei Malay than in English. This is an exception to the more frequent pattern of customers responding use the same code choice among the five as in the initial advertisement.

Brunei: Facebook Status Updates

Nurdiyana and McLellan (2016) analyzed a corpus of 239 Facebook status updates by Bruneians, with their informed consent. 8.8% of these were in Malay only, 60.3% were in English only, and 25.5% had some mixing of English and Malay. The figures do not add up to 100% because Arabic, frequently mixed with Malay by Bruneians, was also part of the analysis. Some examples from this corpus follow:

Both these major syntactic LA strategies signal high levels of bilingual Malay-English proficiency, including the ability to alternate without breaking the syntactic constraints of either language (Muysken, 2000, p. 122). Example (12) shows rich intrasentential mixing, whilst (13) is a trilingual posting:

This trilingual example (13) begins with the Arabic greeting, followed by the Malay conjunction “pasal” governing an English noun phrase. The first sentence ends with the Malay question tag “kh” (short for “kah?”). The second sentence reverts to English prior to a further switch to Malay for the adjective “bisai.” In line with the grammar of Malay there is no copular verb in either sentence: as shown in the free translation, this would be required in standard English.

These examples from Facebook status updates provide further evidence of the diverse patterns of LA in this social media, again demonstrating that all the five code choices, monolingual or mixed, are acceptable and used.

Malaysia: Online News Media Reader Responses

This section is adapted from McLellan (2016). The print media in West Malaysia publishes monolingual Bahasa Malaysia, English, Chinese and Tamil newspapers, but the Malaysian Borneo states of Sabah and Sarawak have newspapers which are bilingual such as the Utusan Borneo, published in Sarawak in Bahasa Malaysia and in the indigenous Iban language (once weekly). In Sabah the trilingual New Sabah Times has sections in English, Bahasa Malaysia, and in the indigenous Kadazandusun language. All are available online as well as in print versions.

One major affordance of online editions of newspapers is reader response, where readers are invited to post their responses to the reports, editorials and feature texts. These have the same interactional features as threaded online discussion forums, and one report can provoke a series of responses akin to a face-to-face conversation. They are moderated by the newspaper staff, and responses deemed inappropriate, offensive or potentially libelous are deleted.

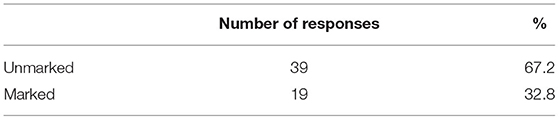

A small corpus of 18 texts with 58 reader responses was collected from the Utusan Borneo and the Borneo Post newspapers between September 2013 and June 2014. These were analyzed in terms of markedness, defined in this context as instances where the language choice of the reader response differs from that of the original posting. An unmarked response is one which uses the same language as the newspaper report. Table 3 gives basic information about this corpus.

Table 3. Language choice in 58 reader response texts in the Borneo Post and Utusan Borneo, Sarawak, Malaysia.

Almost one-third of the reader responses show a language choice which differs from the news report. Text (14) is an example where the response text is code-mixed Malay and English, whilst the original Borneo Post report was in English.

This reader response is in main-language Malay, with three English noun-phrase insertions, all flagged with inverted commas, and one in Iban, “miring” (Iban blessing ceremony).

Example (15) shows a response in English to a report of a road accident in the Iban-language section of Utusan Borneo.

This example shows a higher level of syntactic complexity and lexical density than the response text (14) above, hence it is more formal. Reader response texts can have variable levels of formality, because the asynchronous format of this online genre permits readers to take time in planning their texts before posting them.

As with the Brunei Subreddit discussion forum, Instagram and Facebook texts, some of the reader response texts demonstrate LA between Malay and English, with Iban as a further possible language choice. Example (16) below is one of nineteen responses to a Borneo Post report. Of these, three show Malay/English LA and another is in monolingual Malay.

The pattern of LA in example (16) is intersentential E>M>E>M.

The style is less formal than the monolingual English response text in example (15), and is closer to the conversational discourse found in example (14). The language alternation is a contributing factor to the informality.

In instances where there is LA, or where the reader responses are in a different language to that of the original online news report, there is an assumption that readers share the same multilingual competences as the text producers, and that they will have no problem understanding the response texts. The texts which show a measure of LA thus demonstrate how English coexists and functions as a resource, alongside the other available languages, for the online text producers. These examples from Malaysian online media texts show similar patterns to those from the Brunei social media platforms: all the five possible choices in Table 1 are available, and those responding to postings feel under no constraint to retain the same language choice as the original media report or forum posting, as they know that their responses will be intelligible to readers.

The Other Side Of The Coin: Englishization Of Malay

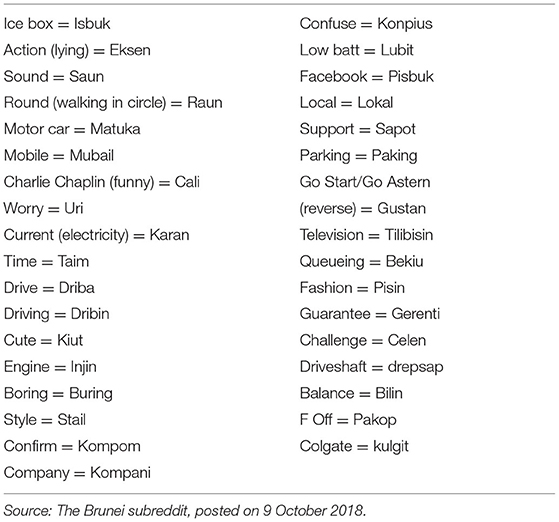

As noted in the introduction, language contact works bidirectionally, and there is ample evidence in Malay texts on social media of the influence of English, leading to englishized or anglicized Malay as an area of investigation. In addition to examples discussed above, Hayani Nazurah (2021) notes the of “tym” or “tyme,” deriving from English “time,” but used as a conjunction to mean “when” in past-tense narratives in a Brunei Subreddit text. Hence this is a shift of word-class. She also notes examples of pronunciation spellings “sinsas” (census) and “mudipait” (modified). A Brunei Subreddit posting from 2018 gives a longer list of mostly pronunciation spellings and other translingual forms used creatively by Bruneians when speaking or interacting in social media in Brunei Malay in Table 4.

One morphosyntactic feature of englishization involves Malay affixes attached to English root words in ML-M texts, as is the case for “berbisnes” mentioned in section analysis and discussion of examples. Example (17), from the Brunei Subreddit (25 April 2022) shows the Malay prefix “be”- affixed to the originally English “disiplin”:

Example (18), also from the Brunei Subreddit (25 April 2022), shows the Malay possessive suffix “-ku” affixed to the originally English noun “boss.”

These demonstrate integration of originally English words into Brunei Malay, and can be seen as reshaping and repossession of the English words, as well as a blurring of boundaries between the two languages, a consequence of extended language contact.

Conclusion

There are two core questions arising from this investigation which can be addressed here, although perhaps not fully answered:

• Is it valid to posit the language of social media as a new variety comprising both local and global influences and inputs?

It is evident that the increased availability and popularity of social media is bringing about changes in patterns of language use. “Lol” (laugh out loud), for example, is now used as a finite verb taking -s, -ing and -ed suffixes. But from the examples presented and discussed here it is also evident that social media platforms are not pushing users toward the use of monolingual English. Patterns of mixing are found, many of which reflect those found in everyday informal conversation. The subsections under 4 and 5 above, when compared and contrasted, show varying patterns of lexical and morphosyntactic LA, and varying patterns of intra-and intersentential mixing. So it may be more reasonable to posit a range of new varieties, not just a single social media variety, which are developing within the diverse social media platforms in Brunei and Malaysia.

• Is social media driving changes in varieties of World Englishes in Southeast Asia?

The evidence assembled here suggests that this question could be answered in the affirmative, provided that there is acceptance of the premiss of World Englishes being by definition code-mixed varieties demonstrating features of the other languages in the multilingual ecologies of nations such as Brunei and Malaysia where distinct varieties of English have developed. Even in monolingual English texts, variable features such as countability of nouns (“an advice,” “equipments,” “furnitures”) may occur, caused in part by the influence of Malay (McLellan, 2020, p. 428–430). However, in spite of the evidence of the wide spread and increasing importance of social media in both Brunei and Malaysia, discussed above, the answer to this major question must remain tentative, owing to the synchronic nature of the data collected and discussed in this paper. Further research into social media language choice and contact patterns could be conducted using longitudinal data collection methods and more extensive textual corpora.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^Example texts: layout and interlinear glossing conventions:

M3, F5, F6, F2: codes for male and female Whatsapp chat and group participants

Italics, English.

Normal font Malay.

BBR, abbreviation.

Ar., Arabic.

DM, discourse marker.

1, first person pronoun.

3, third person pronoun.

DEM, demonstrative.

NEG, negation.

PASS, passive.

POSS, possessive.

RDP, reduplication.

REL, relative.

SG, singular.

References

‘Aqilah, A. (2020). Language Choice and Code Switching in Brunei in Synchronous Electronically Mediated Communication. PhD thesis, FASS, Universiti Brunei Darussalam.

Azirah, H., and Tan, R. (2012). “Malaysian English,” in Englishes in South East Asia: Features, Policy and Language in Use, eds E. L. Low and A. Hashim (Amsterdam: John Benjamins), 55–74. doi: 10.1075/veaw.g42.07has

Deterding, D., and Salbrina, H. S. (2013). Brunei English: A New Variety in a Multilingual Society. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer Verlag.

Diyanah Maimunah, K. (2021). Language Patterns of Online Advertisements and Responses on Bruneian Instagram (Final-Year Research Report). Universiti Brunei Darussalam, Brunei Darussalam.

Garcia, O., and Li, W. (2014). Translanguaging: Language, Bilingualism and Education. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Goode, C. (2020). English language in Brunei: use, policy, and status in education: a review. Indonesian J. English Language Teach. 15, 21–46. doi: 10.25170/ijelt.v15i1.1411

Haji-Othman, N. A. (2012). “Is it always English? ‘Duelling aunties' in Brunei Darussalam,” in English Language as Hydra: Its Impact on Non-English Language Cultures, eds V. Rapatahana and P. Bunce (Clevedon: Multilingual Matters), 175–190. doi: 10.21832/9781847697516-016

Haji-Othman, N. A., and McLellan, J. (2014). English in Brunei. World Englishes 33, 486–497. doi: 10.1111/weng.12109

Haji-Othman, N. A., McLellan, J., and Jones, G. M. (2019). “Language policy and practice in Brunei Darussalam,” in The Routledge International Handbook of Language Education Policy in Asia, eds A. Kirkpatrick and A. Liddicoat (London: Routledge), 314–325. doi: 10.4324/9781315666235-22

Hayani Nazurah, Y. H. (2021). Code-Switching in Online Interactions: Comparative Study of Facebook and Reddit Comments by Bruneian Users (Final-Year Research Report). Universiti Brunei Darussalam, Brunei Darussalam.

Heryanto, A. (2007). “Then there were languages: Bahasa Indonesia was one among many,” in Disinventing and Reconstituting Languages, eds S. Makoni and A. Pennycook (Clevedon: Multilingual Matters), 42–61.

Kemp, S. (2021a). Digital 2021: Brunei Darussalam – Data Reportal. Available online at: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2021-brunei-darussalam (accessed November 3, 2021).

Kemp, S. (2021b). Digital 2021: Malaysia – Data Reportal. Available online at: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2021-malaysia (accessed November 5, 2021).

Kytölä, S. (2012). “Multilingual web discussion forums: theoretical, practical and methodological issues,” in Language Mixing and Code-Switching in Writing: Approaches to Mixed-Language Written Discourse, eds M. Sebba, S. Mahootian and C. Jonsson (Abingdon: Routledge), 106–127.

Li, W. (2018). Translanguaging and Code-Switching: What's the Difference? OUP Blog. Avaialble online at: https://blog.oup.com/2018/05/translanguaging-code-switching-difference/?fbclid=IwAR2DZVo5F7H6xSpzZIPLD4i2yKHXFcBjK_xZsqbDSItD2AuxqMlWNSynFDY (accessed November 5, 20210).

Li, W. (2019). Translanguaging as a practical theory of language. Applied Linguistics 39, 9–30. doi: 10.1093/applin/amx039

Makoni, S., and Pennycook, A. (2007). Disinventing and Reconstituting Languages. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

McLellan, J. (2005). Malay-English Language Alternation in Two Brunei Darussalam Online Discussion Forums. Ph.D. thesis, Curtin University of Technology, Australia.

McLellan, J. (2009). When two grammars coincide: Malay-English code-switching in public on-line discussion forum texts. Int. Sociol. Association RC25 Newsletter 5, 1–22.

McLellan, J. (2016). “English and other languages in the online discourse of East Malaysians,” in English in Malaysia: Current Use and Status, eds T. Yamaguchi and D. Deterding (Leiden: Brill), 125–146.

McLellan, J. (2020). “2nd edn Mixed codes and varieties of English,” in The Routledge Handbook of World Englishes, eds T. A. Kirkpatrick (Abingdon: Routledge), 425–441. doi: 10.4324/9781003128755-28

Muhammad Nabil, K. H. (2021). Examining Language Use by the Ministry of Education, Ministry of Health and Ministry of Religious Affairs on Instagram (Final-Year Research Report). Universiti Brunei Darussalam, Brunei Darussalam.

Muysken, P. (2000). Bilingual Speech: A Typology of Code-Mixing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nurdiyana, D., and McLellan, J. (2016). Gender and code choice in Bruneian Facebook status updates. World Englishes 35, 571–586. doi: 10.1111/weng.12227

Saraceni, M. (2020). “Globalization and Asian Englishes,” in The Handbook of Asian Englishes, eds K. Bolton, W. Botha and A. Kirkpatrick (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Blackwell), 707–724. doi: 10.1002/9781118791882.ch31

Schneider, E. W. (2014). New reflections on the evolutionary dynamics of World Englishes. World Englishes 33, 9–32. doi: 10.1111/weng.12069

Schneider, E. W. (2016). Hybrid Englishes: an exploratory survey. World Englishes 35, 1–16. doi: 10.1111/weng.12204

Seargeant, P., and Tagg, C., (eds.) (2014). The Language of Social Media: Identity and Community on the Internet. NewYork: Palgrave Macmillan.

Sebba, M. (1998). A congruence approach to the syntax of code switching. Int. J. Bilingualism 2, 1–19. doi: 10.1177/136700699800200101

Sebba, M. (2009). Unregulated Spaces: Exploring the Potential of the Linguistic Margins. Available online at: http://www.ling.lancs.ac.uk/staff/mark/unreg.pdf (accessed October 21, 2015).

Keywords: contact, Malay-English, nativization, englishization, social media, translanguaging

Citation: McLellan J (2022) Malay and English Language Contact in Social Media Texts in Brunei Darussalam and Malaysia. Front. Commun. 7:810838. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2022.810838

Received: 08 November 2021; Accepted: 21 June 2022;

Published: 15 July 2022.

Edited by:

Peter Siemund, University of Hamburg, GermanyReviewed by:

Brian Hok-Shing Chan, University of Macau, ChinaGerhard Leitner, Freie Universität Berlin, Germany

Copyright © 2022 McLellan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: James McLellan, amFtZXMubWNsZWxsYW5AdWJkLmVkdS5ibg==

James McLellan

James McLellan