- Netherlands Institute for the Study of Crime and Law Enforcement, Amsterdam, Netherlands

The effects of working circumstances and intended uses on the transcripts of police interrogations cannot be underestimated. In the Netherlands, police transcripts are usually drawn up in the course of the interrogation by the interrogator or, when two police officers conduct the interrogation, by the reporting officer. Contemporaneous transcription involves the interrogators in a complex configuration of interactional commitments. They have to find a way to coordinate the talk and the typing, they must transcribe the talk of an event they themselves participate in, they must do justice to the suspects' story while also taking into account the intended readership of the police report, and they must produce a document that can serve as an official piece of evidence in the criminal case. In studying recorded police interrogations and their transcripts I realised that my own transcripts are also related to their intended uses and to my working circumstances. My transcriptions are much more detailed than those of the police, which draws the attention to the differences between them. The most noticeable difference is that police transcripts focus on substance and mine on interaction. Police transcripts are meant to be evidence of the offence and mine of the talk. But there are also similarities. Both police transcripts and those of mine are selective. Police transcripts orient to their relevance for building a case, mine orient to their relevance for my research questions. Both police transcripts and those of mine treat the transcript as the talk it is meant to represent. For a criminal case this means that in court suspects are held accountable for what the police wrote down as their statement, which disregards the fact that the police transcript is a coproduction.

Introduction

A feature characteristic of institutional life is the production and use of documents, many of which contain transcripts of spoken interaction. As these transcripts are usually written by employees of the institution, and as they are meant to accommodate the needs of their institutional users, I shall call them “institutional transcripts”. “Academic transcripts” are drawn up not just to document what has taken place, but also to observe, analyse and understand it. The aim of this paper is to foster awareness of the affordances and limitations of institutional and academic transcripts for those who draw them up and for their professional users. To this end, I shall analyse police transcripts of suspect interrogations, and investigate my own academic transcripts by comparison. The focus will be on how the practical circumstances of transcribing may affect the transcripts.

I take an ethnomethodological and conversation analytic perspective. Whereas ethnomethdologists have studied texts or documents in their own right, CA studies tend to approach texts or documents as integral parts of many types of talk-in-interaction, especially institutional interaction (cf. Clayman, 1990; Drew, 2006; Mondada and Svinhufvud, 2016). The ethnomethodological view of considering documents as oriented to their future uses and as affected by the practical circumstances of their construction is documented in Garfinkel's work on clinic records (Garfinkel, 1967). Garfinkel (in collaboration with Egon Bittner) drew attention to the fact that documents do not merely describe and represent an outside reality, but that they can be understood as objects in their own right and with their own dynamics. The purpose of these documents is not so much to give an objective representation of the events, but to anticipate future readership and to make available displays of justifiable work or “correct procedures” (see also: Zimmerman, 1969; Smith, 1974, 2001; Harper, 1998; Watson, 2009; Lynch, 2015).

Conversation Analysts focus the attention on the sequential organisation of talk (Sacks et al., 1974). Each turn at talk displays the speaker's understanding of the previous turn and projects the range of activities available to the next speaker (Heritage, 1984). It is not the analyst's interpretations or intuitions that count, but the interpretation of the participants themselves as shown in the sequential organisation of their talk, which can then be an important resource for the analyst. Jefferson's work on transcription for conversation analysis (e.g., Jefferson, 1983, 2004) has become the standard for conversation analytic transcription. The idea is to capture as many elements in these transcripts as is necessary for a detailed analysis. Although transcription is meant to represent the original talk in some way, it is always selective and never to be seen as the ultimate representation. It has been observed that the choices made in transcriptions are linked to the contexts of their production and reception, such as purpose, anticipated audiences, and identity of the transcriber. Transcripts thus testify to the circumstances of their creation and intended use (Bucholtz, 2000: 1440; Mondada, 2007).

Initially, Conversation Analytic studies were based on audio materials. The increasing use of video recordings opened up new areas of research, including the study of gaze, gesture, body posture, and manipulation of artifacts (e.g. Goodwin, 1996; Mondada, 2018). This led to studies of multiple simultaneous activities. The question to be answered is then how these different activities are managed and coordinated in time (Haddington et al., 2014; Mondada, 2014). Mondada (2014) has proposed a systematic ordering of multiple activities based on their temporal position in the interaction. One end of the continuum is occupied by activities that are engaged in simultaneously (the parallel order), the other by activities that remain separate and alternate mutually (the exclusive order). In between are those activities that are coordinated and intertwined with one another (the embedded order). Most often multiple activities are managed by switching from one type of organisation to another.

My research into the ways in which police officers interrogate suspects and report their talk is focused on the organisation of talking and typing, and on the effects of practical circumstances on the talk, the typing and the texts of the transcripts (Komter, 2019). Studying the transcripts of police officers made me think about those of my own, so I decided to investigate the possible effects of my own working conditions and purposes on my transcriptions.

My materials include 34 audio recordings of police interrogations of “ordinary” street crimes, the police reports1 of these interrogations, and my transcripts of the interrogations.2 Because police officers are aware of the risks of their job, risks that may involve putting unacceptable pressure on suspects to confess, most of the police interrogations that we were allowed to record concern common street crimes such as drug dealing, robbery, or theft.

It is not my intention to present my materials and my practices as characteristic of institutional and academic transcription, but rather as examples of specific instances of transcripts of Dutch police interrogations. The fragments presented here are chosen not only to reflect the various conditions under which police officers perform their dual tasks of interrogating and reporting, but also to demonstrate and account for the choices I made for my transcriptions. In the following sections I shall first discuss some of the interactional arrangements in police interrogations for combining talking and typing, after which I examine the practical circumstances of my own transcriptions and the bases of the choices I made in transcribing these interrogations.

Practical Circumstances of Police Reporting

A characteristic feature of Dutch interrogations is the practice of contemporaneous transcription, which means that police officers must find a way of coordinating talking and typing. The organisation of talking and typing varies with the number of interrogators. “solo” interrogations are conducted by a single interrogator, who has to combine and coordinate talking and typing. In solo interrogations the typing alternates with the talk as question-answer-typing sequences (Komter, 2002–2003, 2006; Van Charldorp, 2011).

In “duo” interrogations the interactional organisation of the event is different: it affords opportunities for a division of labour between the two police officers and it provides for different forms of speakership and recipiency. The interactional organisation of the talk is more complex than in the “solo” interrogations as there is also room for interaction between the two police officers and between the reporting officer and the suspect. The usual division of labour in “duo” interrogations is that one of the police officers does the typing and the other does (most of) the questioning. This results in a simultaneous production of the talk and the typing, and for an orientation to interrogating and statement taking as appropriate simultaneous activities. In other words, in solo interrogations the activities are organised serially, and in duo interrogations concurrently (see: Haddington et al., 2014).

Solo Interrogations, Monologue Style

When asked, police officers consider contemporaneous transcription in solo interrogations a necessary evil, as it detracts attention from what they consider to be the core business of the event: interrogating the suspect (Malsch et al., 2012). This is corroborated by my findings that show how investigative questioning may be incompatible with contemporaneous transcribing, especially during antagonistic episodes in interrogations conducted by a single interrogator (Komter, 2002–2003, 2003, 2019).

Police manuals and instructions urge interrogators to start the interrogations with open questions about what happened. The idea is that open questions stimulate suspects to feel at ease and to tell their own version of the events. This enables the interrogator to report the suspect's “own words”, which makes it more difficult for the suspect to withdraw his statement afterwards. Moreover, the length of the answers to open questions will provide the interrogator with enough material to ask new questions (Van den Adel, 1997).

However, the advice to start the interrogation with an open question does not take into account that open questions generate undirected answers, which may not contain the information required for a legally adequate piece of evidence. Another constraint on the management of open questions is, that the answers may be too long to remember and to write down in one go. In a number of interrogations in my materials police officers start with an open question about what happened without writing anything down, after which they recycle the story and report it bit by bit.

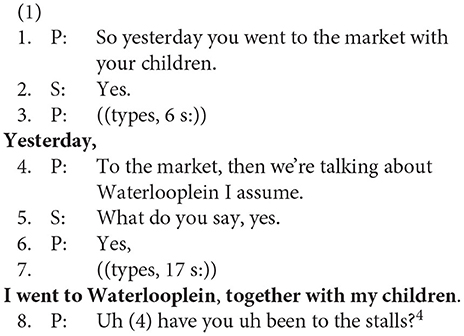

The next fragments are from an interrogation for a case of theft. The suspect initially denies her involvement in the events but eventually she confesses (see Komter, 2003). After the exchanges about the suspect's personal details and her living circumstances (the “social interrogation”), the interrogator (P) begins the interrogation proper by asking the suspect (S) to tell him what happened. He then recapitulates what she told him. According to the suspect, the events took place at “the market” (the text written down in the police report is transcribed in bold, underneath the lines that indicate P's typing):3

We see here that every now and again the interrogation comes to a halt while the interrogator is typing. At the same time, the question-answer-typing (Q-A-T) format makes the typing an integral component of the interaction. It is noticeable that P stops his typing (line 4) in order to specify the location of the events as “Waterlooplein” instead of “the market.” This is important information for the prosecutor, who has to indicate the time and place of the offence in the indictment. The monologue style of the report transforms the interaction into a seemingly volunteered narrative by the suspect.

P's recapitulation (line 1) works to round off the suspect's “free story” and to embark on the reporting of it. It is a formulation used to demonstrate understanding of the suspect's prior talk (Heritage and Watson, 1979). As it projects confirmation, it serves as a “candidate recordable” that elicits not only the suspect's agreement with the formulation but also with the text to be written next. P's typing (lines 3 and 7) transforms the interactional organisation of the talk into a question-answer-typing (Q-A-T) format. The Q-A-T format is found especially in the uncomplicated, routine episodes of the interrogations. It consists minimally of one question-answer exchange, but more often there is a series of questions and answers preceding the typing (Komter, 2006). During the typing, the suspect usually waits for the interrogator to ask the next question.

P's typing activities have “turn-like” features, as they start at transition relevance places in the suspect's talk, and they occupy the floor. Moreover, they can be understood as third position actions, serving as a sign of acceptance and understanding of the suspect's prior answer. The difference with conversational turn-taking is that the setting is “partially opaque” (Goodwin, 2000: 1508), in the sense that the suspect does not know what the interrogator is writing, nor how long the typing will last. Thus, as long as the typing occupies the floor, there is no transition relevance place for suspects to take the next turn. As interrogators generally take the turn after the typing, the Q-A-T format reinforces the interrogator's position of initiative and control.

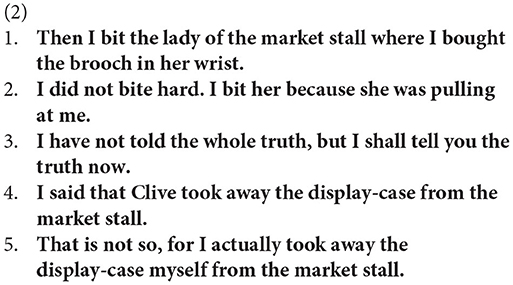

As the tension in the interrogation increases, the interrogator suspends the typing for a while and directs his attention exclusively to the suspect instead of to the screen of the PC. The next fragment is part of the police transcript (the numbering is added by me):

Denying suspects do not usually change their position without inducement from the interrogators. The text gives no information about what actions the interrogator actually took, nor how much effort it took to persuade the suspect to confess. Indeed, a comparison with the talk in the interrogation shows that between lines 2 (“I bit her because she was pulling at me”) and 3 (“I have not told the whole truth”) there is half an hour of interaction that is not written down, in which the interrogator gradually steers the suspect toward her admitting not having told the truth. At this point the interrogator takes a break, in which the suspect goes to the toilet, after which the interrogator gives her a glass of water. He continues:

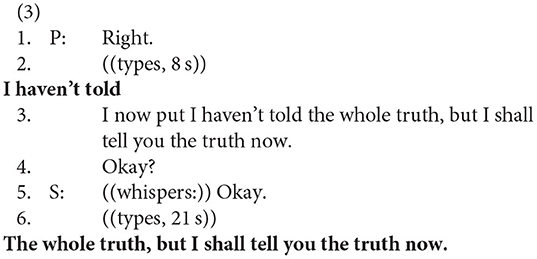

P‘s resumption of typing indicates that a different type of activity is relevant now beside interrogating her: from now on, he will be taking down her statement again. The whole episode of steering S toward a confession is retrospectively treated as “off the record”. The talk in the interrogation will be talk-for-the-record again, the story that the suspect will tell will be the truth, and the truth will be recordable as piece of evidence.

The shift between the two activities of interrogating and typing is achieved explicitly; P does not only tell S that he types, but also what he types (line 3). Moreover, he asks for S's permission and agreement with the text to be written. In doing this, he constructs this moment as point of no return. With her support he writes down that she will tell the truth now, which involves her changing her story in such a way that a confession becomes relevant. P's articulation of what he is about to report suggests that it is now too late for her to go back on her promise, as the text written down constrains S's options.

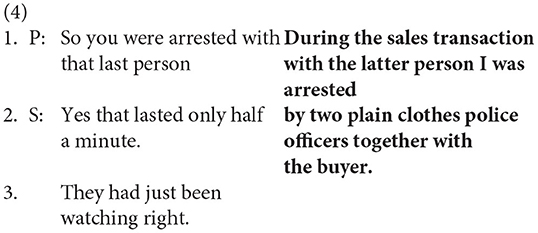

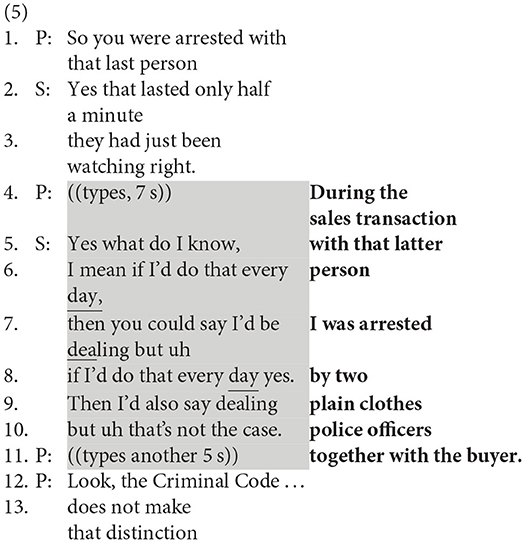

The text of the next fragment is from an interrogation in a case of drug dealing. In a street in Amsterdam notorious for drug dealing activities, the police had been watching the suspect's actions for a while. In the course of his third drug deal he was arrested. P recapitulates S's description of his arrest (the written text is presented in the right hand column):

P recapitulates the suspect‘s prior talk with a formulation (line 1; Heritage and Watson, 1979) that projects a confirmation, the answer to which allows him to report that there has been a “proper arrest”, because the suspect has been caught in the act. Moreover, he adds a lot of information in the police report that is not talked about in the interrogation. This can be attributed to the two “directions” of the police report: it is meant to look backward as representation of the talk in the interrogation, and forward in anticipation of the needs of future readers of the report. His additions and the stilted style in which the suspect seems to express himself suggest that the interrogator is orientated more to the prospective readers than to the suspect's original talk.

Let us now consider the interactional organisation of talking and typing. As S goes on talking after P has started typing, I shall transcribe the simultaneity of the talk and the typing, and suggest what text is typed when. The concurrent talk is transcribed by gray shading, to exhibit the simultaneousness of the talk and the typing.5

As in fragment 1, the interrogator recapitulates prior talk and listens to the suspect's confirmation before starting to write (lines 1–3). Although P allows the suspect to finish his utterance, the text of his subsequent typing shows that he only pays attention to S's confirmation (“Yes”, line 2). This then provides him with the opportunity to reformulate and elaborate his summary, as his entry into the police report shows.

The episode starts off as a Q-A-T sequence. However, in this instance S does not wait for P to ask a next question, but picks up his talk 7 seconds after the start of the typing. The suspect not only takes the story further than the question asked for, but his elaborations also portray his doings as “normal” activities in everyday life. His additions resemble the “narrative expansions” identified by Galatolo and Drew (2006), that are produced to defend a person against a possible allocation of blame implied in the question. The absence of a slot for S's defensive elaborations, and the apparent urgency of his defensiveness, prompt his early response. When he is done, P completes his typing after 5 seconds (line 11). His next turn exhibits that he has heard the suspect's contributions (lines 12–13), but he does not write them down.

My materials show that interrogators tend to continue with their typing when suspects talk simultaneously, and that what suspects say simultaneously tends not to be written down. At the end of the interrogation the suspect reads the transcript, is asked if he agrees with it and signs it. In my materials, suspects never complain of items that have not been written down.

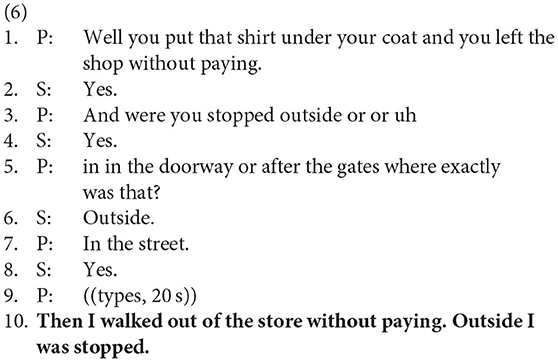

One of the arguments police officers gave for their dislike of contemporaneous reporting was that it interferes with the flow of the conversation (Malsch et al., 2012). On the other hand, police officers have no problems with picking up the thread of prior talk, because they have only to look at the screen to see where they have left off. In the next fragment from a case of shoplifting the last sentence on the screen reads: On the ground floor I took a T-shirt worth Fl. 15,- from a rack and put it under my coat. P continues:

P reads from the screen in front of him what he has typed last, transforms it into a sentence addressed to the suspect (“you put that shirt under your coat”, line 1) and proposes a “reasonable” future recordable (“you left the shop without paying” line 1). The suspect's response (line 2) is both a confirmation and permission for it to be written down. Thus, the transcript-thus-far is used as a resource to carry on the interrogation where it was left off, and as a means to take the suspect's story further.

In sum, solo interrogations are organised as a series of Q-A-T sequences, especially in the unproblematic parts of the interrogations. The Q-A-T sequence is accomplished by a piecemeal elicitation of “chunks” of information and by writing them down step by step. The typing is accompanied by a temporary shift from a mutual focus on the interaction to divergence, where the attention of the interrogator is directed toward the screen of his PC.

A constraint on the typing is the problem of reporting answers to open questions. In the more problematic episodes there may be a suspension of the typing, signifying that the unreported talk is “off the record” for the time being. This testifies to a potential incompatibility of talking and typing, as the interrogators” attention to the screen would reduce the intensity of their questioning. In addition, police interrogators may be reluctant to put their more adversarial actions on display.

Duo Interrogations, Question-Answer Style

The usual division of tasks in duo interrogations is that one police officer asks the questions and the other writes down the talk. There are various ways in which the interrogating officers encourage and inform the reporting officers' writing tasks. For example, interrogators sometimes explicitly instruct reporting officers on what to write, and in some cases they slow down their talk and articulate it as if dictating a text to the reporting officer. At a more implicit level, the interrogating officers may show an awareness of the reporting officers' tasks at hand by leaving pauses for the typing or by producing utterances that could facilitate the reporting, for example repeats of the suspects' answers (Komter, 2019). This shows that the division of labour is not just an instance of a participation format that consists of separate activities, but that it provides for the collaborative constitution of a shared stance (Goodwin, 1996: 375).

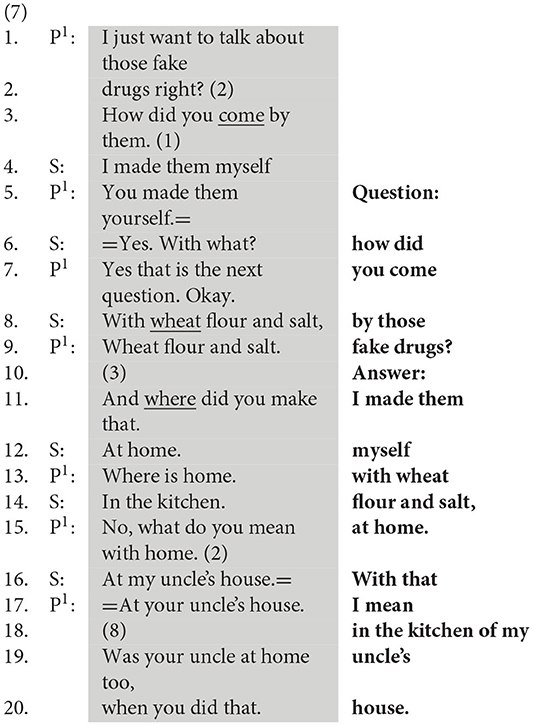

The next fragment, in the question-answer style,6 is an example:

As the typing is almost continuous, it is difficult to ascertain exactly when what text is typed. By the time P1 asks his question (line 3) the reporting officer (P2) is still typing up the prior talk. It can be suggested that at the same time she orients to the talk, as she suspends her typing during the suspect‘s answer (line 4). The first potential moment for her to report the question-answer exchange is after that, but it is possible that she is still finishing typing up prior talk. In either case, it will be clear that the typing lags behind, and that the pauses left by the interrogator are not long enough for her to keep up with the talk.

One of the ways in which interrogators take the work of the reporting officers into account is to repeat the suspect's answer, followed by a pause. There are three repeats in this fragment (lines 5, 9 and 17). The first repeat is followed immediately by the suspect's confirmation and by his production of what would be the next logical question (line 6). The suspect's answer to this question is then followed by the second repeat (line 9). This time the interrogating officer (P1) is in the position to leave a pause after the repeat (line 10), as the suspect waits for the next question. P1's next question (line 11) does not at first receive what he considers to be a complete answer, as is evidenced by his further questioning about the meaning of the suspect's answer “at home” (line 12). The suspect's final answer “at my uncle's house” (line 16) is then accepted by P1 with a repeat followed by an eight second pause (lines 17–18).

The combination of repeats and pauses attends both to the “recordability” and to the “typability” of the talk. P1s choice of repeats suggests the recordability of the substance of the text to be written down and his leaving pauses promotes the “typability” of this text (cf. Moerman, 1988: 54). The inclusion of the pauses is not P1s decision alone, as S takes the opportunity to respond to P1s first repeat (lines 5-6). Although the pauses facilitate the typing, they are much shorter than the “typing turns” in the solo interrogations. P1 apparently relies on P2's capacity to listen and type at the same time.

It can be noted that four questions are asked (lines 3, 7, 11 and 15), whereas only one question is reported (lines 5–9, right hand column). Thus, the suspect is reported to answer “more than the question”. This is common practice in question-answer police reports, as it is a way for the reporting officer to deal with the constraints of time. In the question-answer style transcripts in my materials about one in six of the questions asked are written down (De Boer, 2014), resulting in a “monologisation” of the Q-A style reports (Komter, 2019).

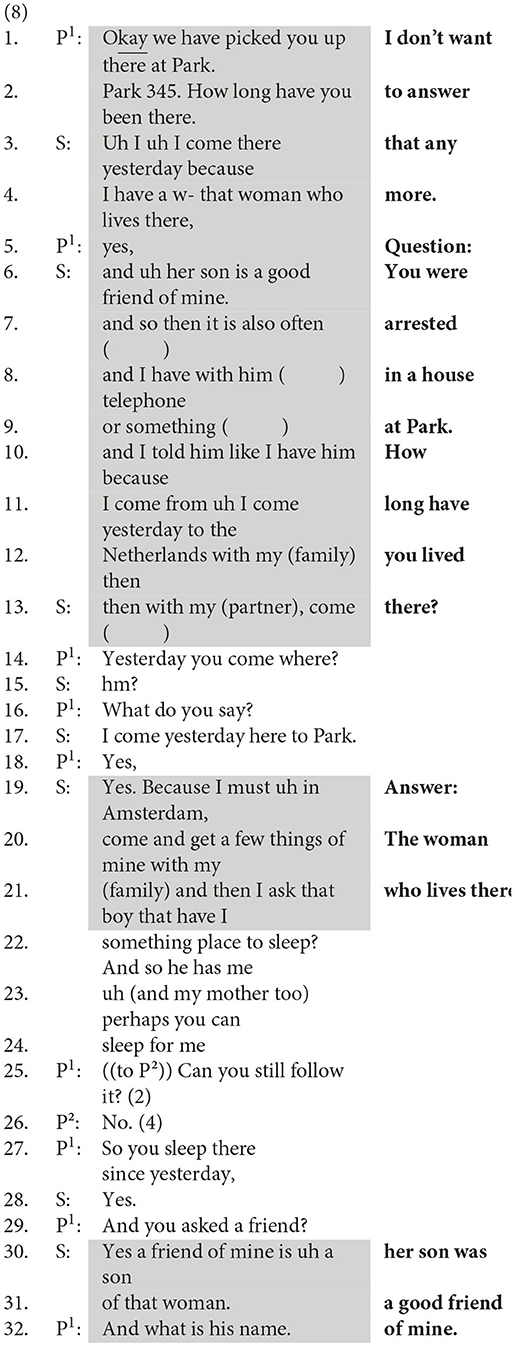

The next excerpt shows problems not only with the intelligibility of the suspect's talk, but also with the teamwork. The suspect is a man from Sudan, who speaks a kind of Dutch that is difficult to understand. The interrogators suspect that he is an illegal immigrant and that he has been staying in The Netherlands for some time. The suspect does not want to answer the repeated questions by the interrogator about how he travelled to the Netherlands. The case related interrogation begins with P1 recapitulating the conditions of the suspect's arrest, followed by a question about the duration of his stay thus far. In the meantime the reporting officer is still writing down the suspect's prior answer:

Let us first examine the talk. The suspect answers the interrogator's question about the duration of his stay immediately (“I come there yesterday”, line 3), but then he continues by giving what seems to become an account (“because … that woman who lives there”, lines 3-4). P1 encourages him to proceed with a continuer “yes” (line 5), after which the suspect goes on with a long uninterrupted turn (lines 6-13). His account is rambling and difficult to understand, but P1 gives him the scope to expand and does not ask for clarification until line 14. One phrase that can be understood is S's virtual repetition of “I come there yesterday” (lines 3 and 11). This is then taken up by P1 for further detailing (line 14). After the suspect provides the answer (“I come yesterday here to Park”, line 17) P1 utters another “yes” continuer (line 18), which is followed by what appears to be the suspect's motivation for coming to the address where he was arrested.

At the end of this P1 turns toward P2 to ask if she can still follow it (lines 25–26). Here the participation status of the participants changes: the interrogator draws the reporting officer into the interaction, while the suspect is temporarily excluded. The shortness of P2s answer displays an orientation to minimal intrusiveness and characterise the exchange as a form of “byplay”, which does not terminate their prior alignment but holds it in abeyance to be reengaged at a next moment (Goffman, 1981: 155). The 4 second pause marks an interactional “no man's land” after which the original participation format is reinstated. P1 “recycles” the suspect's narrative by repeating some items in combination with some further questioning (lines 27–32).

There are three periods of typing in this episode (lines 1–13, 19–21 and 30–32). P2 stops the typing for a short while when P1 asks questions for clarification and S answers (lines 14–18). When the typing is halted a second time this may have been a sign for P1 to ask P2: “can you still follow it” (line 25). On P2's negative answer (line 26), P1's subsequent recycling of the suspect's original answer (line 27) may be produced as a “candidate recordable” to enable P2's reporting of it (see the formulations in fragments 1 and 4).

However, if we look at the text that is typed up contemporaneously by P2, we see that she wrote down the question (lines 5–13, right hand column) in the course of the talk between P1 and the suspect, but missed the answer (“I come there yesterday”, line 3). Instead, in spite of P1's question for clarification and the suspect's answer about the day of his arrival (lines 14 and 17), and in spite of P1's reformulation (line 27) she wrote down the account about “the woman who lives there” and her son (right hand column, lines 19–21 and 30–32). This text corresponds with the suspect's talk directly following his answer (lines 4 and 6).

These troubles may be attributed to the fact that the suspect's talk is rather unintelligible and that P1 allows him some scope for continuing his narrative. P1 appears to listen to the suspect's account as a “free” story, and to give him the opportunity to present his version of the events without interference. As mentioned above, this occurs quite often in solo interrogations, after which the interrogator recycles the suspect's story as a Q-A-T format to accommodate the typing. In duo interrogations, as the example shows, the “free story” may be incompatible with a parallel organisation of talking and typing.

Because of the differential pace of talking and typing, P2 writes down a selection or summary of the talk. P2 has selected the item of “the woman who lives there… her son is a good friend of me” (lines 4 and 6) for inclusion in the report. It can be expected that her problems are a result of the circumstance that from the moment that she misses the suspect's answer (line 3: “I come there yesterday”) and writes down the next item (lines 4 and 6: “the woman who lives there…”) she listens for possible continuations of the text on the screen. These troubles are likely to result from diverging orientations: P1 listens for the story or for elements in the story to be taken up later, while P2 listens for the typing and for the text: she has to combine the writing down of previous talk with listening for what to write next, while taking into account the text already on the screen. It is the kind of “practical listening” that exhibits their different tasks at hand.

Summary

In “duo” interrogations the typing has a less prominent position than in solo interrogations: it does not occupy the floor and the moments of typing onset or typing completion have less sequential relevance for the talk. Duo interrogations show various degrees of “teamwork”. Interrogators may facilitate the writing by repeating an answer and by leaving pauses for the typing, or they may follow their own plan and leave it up to the reporting officer to decide what to write. Reporting officers are dependent on the interrogating officers for allowing them the time to write, and interrogating officers depend on the reporting officers' skill in keeping up with the talk and selecting the relevant items for the report.

However, when interrogating officers leave pauses for the reporting officer after a “recordable” answer of the suspect, these pauses are usually not sufficient to complete the reporting of prior talk. This makes for a more complex writing task than in the ‘solo” interrogations as, beside the problems resulting from the constraints of time, the reporting officers have to remember and write up past talk, see to it that the text of the current writing is in line with the text already on the screen, and at the same time listen to current talk for future “recordables”. The simultaneity and the differential pace of talking and typing affect the typing more than in the “solo” interrogations; it may result in mishearings, in a more selective reporting, and in a “monologisation” of Q-A style reports.

Conclusion

I have presented the fragments of police transcripts as examples of the coordination of the talk and the typing in solo and duo interrogations, and of the ramifications of contemporaneous talking and typing. In a broader sense, these fragments can be seen as instances of the impact of practical circumstances and purposes on the actions of the interrogators and on the texts of their transcripts.

Contemporaneous transcription inevitably leads to selective transcripts. The fragments shown here show two writing styles: the monologue and the question-answer style. The monologue style reads as a statement volunteered by the suspect, the question-answer style includes the interrogators” activities. Although the question-answer style police transcripts are more transparent, this is deceptive as most of the questions asked are not reported. Whatever the writing style, the police transcript is always a summary of the talk that focuses on substance rather than on interaction.

The practice of contemporaneous transcription of police interrogations entails a coordination of talking and typing. In solo interrogations this is predominantly accomplished exclusively, where the two activities alternate as question-answer-typing sequences. The separation of talking and typing is achieved by the suspects' waiting for the interrogator to finish the typing, and by the interrogators' disregard of the suspect's contributions during the typing. However, this organisation can develop into a more parallel organisation when suspects choose to add elaborations to their answer during the typing.

In duo interrogations there is usually a division of tasks, which allows the talking and the typing to be produced simultaneously. The temporal organisation of the two activities is more precarious than in the solo interrogations. The interrogator takes into account the tasks of the reporting officer, by repeating the reportable items and by leaving pauses for the writing. But a repeat does not necessarily result in the reporting of the required answer, and the pauses are usually too short for the reporting officer to keep up with the talk. This may result in a suspension of the typing or in a misrepresentation of the talk.

Thus, the talk, the typing and the text are inextricably interwoven. The talk is not merely a search for the truth about what happened but it is also directed at eliciting recordable answers that may contribute to building a case. The typing is not merely an activity for reporting what has been said but it is also part of the interaction between the interrogator and the suspect or, tacitly or explicitly, between the interrogator and the reporting officer. And, especially in the solo interrogations, the police transcript is not merely a document in which what is said is laid down, but it actively informs and directs the interrogation.

Practical Circumstances of Academic Transcription

One of the practical circumstances that researchers have to deal with is the nature and quality of the recordings. The first series of 20 interrogations was collected around the turn of the century, when interrogations for “ordinary” street crime were usually conducted by one interrogator, and when the usual format was the monologue style. After a series of miscarriages of justice in the first decade of the century, it became more common to conduct the interrogations with two police officers, in the question-answer style. So the second collection of 14 interrogations differs in reporting style and number of interrogators.

Police interrogations are difficult to come by. During the entry negotiations I had to appease the worries of the officials I approached who were afraid that the recording process might interfere with the management of the interrogations. As the recording equipment we used was small, and as I thought it would be adequate for our purposes, I opted for audio recordings. If I had known the importance of the typing for the organisation of police interrogations beforehand, and if I had known that I wanted to include the texts of the police reports in my transcriptions, I would have tried to install some kind of a text tracking device through a connection between the audio-recorder and the computer that would enable me to trace exactly what was typed when. And to be able to analyse the embodied manifestations of the interrogators' dual attention to the screen and the suspect, I would have preferred video instead of audio recordings.

It is a feature of academic transcription that the research questions develop in the course of getting familiarised with the materials through transcribing them. This entails a constant movement between research questions and transcription (Mondada, 2007: 810). In the course of this process, I had to make decisions about whether to insert the text of the police report in the transcripts, how to transcribe the talk and the typing, the coordination of talking and typing, the amount of detail, and the translation. And I had to reconsider these choices whenever I thought there were better ones.

The Talk and the Text

In the early stages of my work I decided to insert the text of the police reports into my transcripts, in order to show comparisons of the talk with the text. This was easy for the Q-A-T sequences, as I transcribed the typing as transcriber's note, for example: ((types, 20 seconds)) and underneath that the corresponding text in bold (see fragments 1, 3 and 6). I got into trouble when the typing and the talk co-occurred. I solved that by constructing two columns, with the interaction in the left hand column and the corresponding text of the police report in the right hand column (see fragment 4).

However, this did not give any insight into the moments in the interrogation in which the texts were typed by the police officer. So I reconstructed what was typed up when. This was more or less easy in the interrogations with one interrogator (see fragment 5), but more difficult in the interrogations with two interrogators where talking and typing co-occur (fragments 7 and 8). The reconstruction of the moments when the texts were typed is based on an inspection of the following:

1. the correspondence between the talk and the text;

2. the differential pace between the talk and the typing;

3. the text follows the talk;

4. the length of the talk and the approximate length of the typing;

5. break off of typing may signify a completion of the text thus far.

This is the most problematic feature of my transcription, but the nature of my recordings makes it impossible to be more exact. For the problematic episodes I have “try-typed” the Dutch text and compared its duration with the duration of the talk in the audio recording of the episode. These ways of reconstructing what was typed when shows that in these circumstances the text lags considerably behind the talk.

Talking and Typing

As I became familiarised with the materials, I soon realised that the typing was more than just a pause in the talk or a background noise, because what I first transcribed as pauses were much noisier and longer than conversational pauses, and they clearly embodied specific activities of the police officers. Moreover, I had to find a solution to the problem of transcribing the co-occurrence of talking and typing.

There is no standard way of transcribing keystrokes. Zimmerman (1992) uses dashes to indicate keyboard activity. Whalen's transcription (Whalen, 1995) uses different symbols to indicate keystrokes, space bar, tab, back-tab, return, cursor, and arrow keys. Van Charldorp distinguishes between louder (X) and softer (x) keystrokes (Van Charldorp, 2011). Greatbatch et al. (1995) use symbols that differentiate between keystrokes, keystrokes that are pressed with greater force than normal, and return keystrokes.

In those cases where there was co-occurrence of talking and typing I used ### symbols to indicate the typing, and the overlap symbol [to indicate at what moments the talk and the typing co-occurred (see Komter, 2006). The problem with this notation is that it creates the impression that an audio recording allows the transcriber to hear and transcribe every single keystroke separately. I therefore decided to transcribe the talk and the typing not as two different lines but as one, the typing marked by a shade of gray covering the simultaneous talk, as a more direct way to accentuate the simultaneity of the two different activities (fragments 5, 7 and 8; Komter, 2019). I realise that this involves a loss of detail regarding variations in keystroke activity.

Amount of Detail

The basic principle of Conversation Analytic transcription is “to get as much of the actual sound as possible into our transcripts, while still making them accessible to linguistically unsophisticated readers” (Sacks et al., 1974: 734). While my transcripts give a more complete and more detailed account of the talk than do the police transcripts, they are less detailed than the usual Jeffersonian transcript notations.

Decisions about the degree of detail in academic transcripts depend on their relevance for the research questions and analytic perspective (Hepburn and Bolden, 2012: 73–74). And, conversely, the research questions may be adapted on the basis of what emerges in the process of transcription. As research questions may change in the course of getting familiarised with the data, it would be sensible to start out with a detailed Jeffersonian transcription, to diminish the chance that you are missing something essential (Jefferson, 1983).

On the other hand, there are practical considerations. The bulk of my materials led me initially to make more global transcriptions, until I could decide what phenomena were worth studying in more depth. As my research questions became more definitive, I adapted the transcription accordingly. Moreover, as I aimed for a broader audience, I was faced with the choice between detail and readability. I made use of Jeffersonian transcription notations as much as I thought I needed and added some of my own when I thought I needed them.

Translation

As I published most of my analyses in English I had to translate the original Dutch transcripts. Translations can never represent the phonetic details of the original talk, so only those features of the standard transcript notation have been preserved that are compatible with the translation: intonation, stress, pauses and overlap. Thus, it is inevitable that translation increases the distance between the transcript and the original talk. The challenge is to capture in the translation the salient details of the original language.

The usual way to present translated transcriptions to an English speaking readership is a three-line transcription, where the first line is the original transcript, the second line a word-by-word translation into English, and the third line an idiomatic translation that is meant to capture the conversational style of the talk (cf. Hepburn and Bolden, 2012: 68–69). For my purpose this turned out to be impractical, as I decided to transcribe the talk, the typing and the text in one and the same excerpt. So I chose the solution of presenting the original Dutch examples in an appendix (see Appendix). Another argument against the three-line transcription is that, when the publication has restrictions on the size of the article, the inclusion of the transcript in the original language leaves less space for analysis and discussion (Slembrouck, 2007).

Discussion

The transformation of talk into writing allows for the transportation of the resulting written texts to readers who may use these texts in the performance of their professional tasks. As this is a crucial element of professional practices, this holds for the professionals in the criminal law process but also for academics who study and transcribe the talk. In fact, the transformation of talk into writing is one of the basic tools of conversation analysis, as transcription is the instrument for making talk in interaction available for inspection, reproduction and publication. Although the transcriptions made in conversation analytic studies are obviously constructed to be more accurate and complete representations of the talk-in-interaction than police transcripts, the principle is the same: talk is transformed into written materials that are easier to manage than live talk because they are fixed and transportable, so that they can be made accessible to a particular readership to serve specific ends. Below I shall discuss differences and similarities between police transcripts and my academic transcripts related to participation, purpose, relevance and selectivity, and to the status and treatment of the transcripts.

Participation

Police officers are participants, who are transcribing the talk in the interrogation that they are conducting. They are active speakers and hearers, monitoring the suspects' ongoing talk for inserting their own contributions and responses. They listen for understanding and for responding, but also for the recordability of the suspects' answers. On top of this, they must make a transcript, while being involved in the moment-by-moment contingencies of the configurations of their interactional commitments. A feature of contemporaneous transcription is that the completion of the interrogation coincides with the completion of the police transcript. When the participants have signed the police report, both the interrogation and the report are brought to an end.

Whereas the police transcripts were completed and ready to be sent off to the desks of those who would deal with the case, mine had yet to begin. I collected the recordings and the police reports and, in the relative peace and quiet of my office I could begin to play and replay the recordings, not only to understand what the participants were saying, but also to inspect more closely the phenomena that I discovered in the materials as I progressed with the transcription. This is a solo-activity as it is not embedded in interaction with others. It is similar to the activities in solo interrogations as it involves a continual shift of attention between the recording equipment and the screen of the PC, between listening and writing. Because the transcription relies on recordings instead of on participation, academic transcripts are only completed when they appear in print. But even then, they remain open for discussion and revision (cf. Bucholtz, 2007).

The transcription of audio or video recordings of talk and action involves a change of perspective, as the unique and ephemeral moments of the event are reproduced as moments in the recording, which can be played and replayed by observers who were not necessarily present at the time and did not take part in the interrogations. Thus, the sources of transcripts, live or recorded interaction, affect participation and perspective, and are therefore sources of differences between the texts of the transcripts.

Purpose

Another source of differences is the orientation to the intended uses of the transcripts. Police transcripts are meant to serve the legal professionals who will deal with the case in later stages of the criminal process as basis for their decision-making. Police transcripts are oriented to what the suspects have told the interrogators about “the facts”, rather than to the interactional contexts of the creation of the transcripts. They are summaries of the interrogations, not only because of the circumstances of contemporaneous transcribing but also because judges are satisfied with a police report that contains a “factual representation” of what the suspect told the police (Franken, 2010: 406), rather than being burdened with a verbatim transcript.

My aim is, among other things, to observe and analyse the work of police officers in the interrogation room for academic publication. The aim of my transcripts is to gain insight into the processes by which police transcripts are produced. A result of the differences in purpose and use of the transcripts is that my transcripts are much more detailed and cover the whole of the interaction in the interrogations. Moreover, my transcripts changed in the course of my research as my understanding of the role of the typing, of the coordination of talking and typing and of the impact of the written texts on the interaction increased.

Thus, the purpose of police transcripts is to create a document that can serve as evidence in a criminal case; academic transcripts can also be considered as evidence, but they are evidence of the talk, not of the offence. Although the purposes of the two types of transcript differ, they are similar in that they are both meant to be a representation of the talk, and they are both “recipient designed”, as they take into account their future readership.

Relevance and Selectivity

When asked, police officers say that they do not aspire to transcribe the whole interrogation, but that they only write down what is relevant for the case (Malsch et al., 2012). One may wonder what they mean by “relevant”. It has been observed for the UK that what is written down in the police transcript (the ROTI), is more relevant for the prosecution than for the defense (Haworth, 2018). In my Dutch police transcripts I found that there is an orientation to building a case, but not specifically for prosecutors.7

As I have shown, my transcriptions were modified and adapted to what I thought at that moment was relevant for my research questions and necessary for my analyses. Another type of academic selectivity is the choice of fragments to be analysed and discussed in the publications. Police transcripts are meant to cover all the relevant items of the entire interrogations, and so are mine in the first instance. But when I come across a phenomenon worthy of further study, I do a “data run” in my materials to find similar or dissimilar instances. From these instances I select those fragments that I can build upon to further my analyses. And when preparing a publication I make another selection of instances that will fit the organisation of the publication and the publication standards.

As judges, prosecutors and defense lawyers select items from the police reports in the execution of their professional tasks, so do I. Thus, police transcripts and my academic transcripts are different in the amount of detail they contain, but similar in that they are constructed on the basis of their relevance for the uses to which they are put.

The Status and Treatment of Transcripts

What struck me when I studied the references to and quotations from the police reports by the judges in court was that, even when it was clear that the sentences they read aloud would never be uttered like that by a suspect (see for example fragment 2), judges treated the suspects as having said what was written down in the police report as their own production, and held them accountable for it (Komter, 2019). This can be attributed to the language ideologies of decontextualised fragments and of narrator authorship (Eades, 2012: 447–448), which encompass a disregard of the interactional context in which the suspect's statement was elicited, and ignore the co-authorship of the police transcripts.

I realised that I am doing something similar. I refer to my transcription as if it were the talk rather than a representation of the talk (see my treatment of the examples 1–8). I also realised that this is common practice in Conversation Analytic or Discourse Analytic research publications (but see: Haworth, 2018). My research aims are to analyse the talk, not the transcript, and to compare the police transcript with the talk in the interrogation, not with my transcript. Yet, when it comes to write down and publish my results, I can only demonstrate differences between two kinds of text: the institutional transcripts of the police officers and my academic transcripts.8

The legal professionals who deal with police transcripts later on in the criminal process must know that what they read cannot be exactly the same as what the suspect actually said, and academic professionals know that transcripts can never capture all the details of talk in interaction. The habit of treating the text as the talk, both by institutional and academic professionals, can be explained by the focus on their primary tasks. For legal professionals these are to study and decide on a criminal case, for academics to study the talk. Institutional and academic professionals, for all practical purposes, take transcripts at their face value, as this is part of their professional routine and instrumental for getting their work done. At the same time, academic and institutional professionals should be aware of the specific limitations of their transcripts, as the stakes are high. For criminal law practice the quality of the transcripts may ultimately affect the justice of the criminal process, for academic research the validity of the findings.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the data are subject to restrictions of the Dutch Prosecution Office. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to the Dutch Prosecution Office.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Funding

This publication was funded by the VUvereniging publication fund.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful for the pertinent and insightful comments of the anonymous reviewers.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2022.797145/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^Police reports are documents that contain the necessary administrative items and the police transcript of the interrogation (see: Komter, 2019). They are used in court as official pieces of evidence.

2. ^Of these interrogations and police reports, 20 were collected by me and 14 by Tessa van Charldorp.

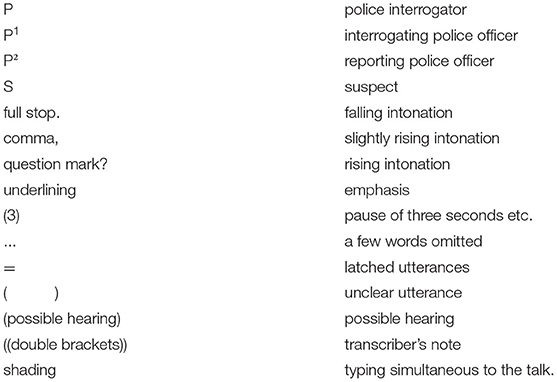

3. ^Transcription conventions

4. ^For the original Dutch examples see the Appendix.

5. ^This is an approximation, as it is impossible to ascertain the exact placement of the text.

6. ^My police materials contain transcripts in three writing styles: monologue style, question-answer style, and recontextualised monologue or “you ask me” style (see Komter, 2019).

7. ^This may be related to differences between the accusatorial and inquisitorial criminal law systems.

8. ^Occasionally, publications contain links to the sound clips of the articles. See: https://www.sscnet.ucla.edu/soc/faculty/schegloff/sound-clips.html.

References

Bucholtz, M. (2000). The politics of transcription. J. Pragmatics 32, 1439–1465. doi: 10.1016/S0378-2166(99)00094-6

Bucholtz, M. (2007). Variation in transcription. Discourse Stud. 9, 784–808. doi: 10.1177/1461445607082580

Clayman, S. (1990). From talk to text: newspaper accounts of reporter-source interactions. Media Cult. Soc. 12, 79–103. doi: 10.1177/016344390012001005

De Boer, M. (2014). “Ik Zal Het in Die Bewoordingen op Papier Zetten”. De Verschillen Tussen Politieverhoren en Processen-Verbaal. [“I Shall Put It on Paper in Those Words”. The Differences Between Police Interrogations and Police Reports]. NSCR Report.

Drew, P. (2006). “When documents ‘speak': documents, language and interaction,” in Talking Research: Talk and Interaction in Social Research Methods, eds. P. Drew, G. Raymond, and D. Weinberg (London: Sage), 63–80.

Eades, D. (2012). The social consequences of language ideologies in courtroom cross-examination. Lang. Soc. 41, 471–497. doi: 10.1017/S0047404512000474

Franken, A. A. (2010). Regels voor het strafdossier [Rules for the criminal case file]. Delikt en Delinkwent 40, 403–418.

Galatolo, R., and Drew, P. (2006). Narrative expansions as defensive practices in courtroom testimony. Text Talk. 26/6, 661–698. doi: 10.1515/TEXT.2006.028

Goodwin, C. (1996). “Transparent vision,” in Interaction and Grammar, E. Ochs, E.A. Schegloff, S.A. Thompson (eds.). (Cambridge ST: Cambridge University Press), 370–404.

Goodwin, C. (2000). Action and embodiment within situated human interaction. J. Pragmatics 32, 1489–1522. doi: 10.1016/S0378-2166(99)00096-X

Greatbatch, D., Heath, C., Luff, P., and Campion, P. (1995). “Conversation analysis: human-computer interaction and the general practice consultation,” in Perspectives on HCI. Diverse Approaches, A. F. Monk, and G. N. Gilbert (London: Academic Press), 199–222.

Haddington, P., Keisanen, T., Mondada, L., and Nevile, M. (2014). “Towards multiactivity as a social and interactional phenomenon,” in Multiactivity in Social Interaction: Beyond Multitasking, eds. P. Haddington, T. Keisanen, L. Mondada, and M. Nevile (Amsterdam; Philadelphia: John Benjamins), 3–32.

Harper, R. H. R. (1998). Inside the IMF. An Ethnography of Documents, Technology and Organisational Action. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Haworth, K. (2018). Tapes, transcripts and trials: the routine contamination of police interview evidence. Int. J. Evid. Proof. 22, 428–450. doi: 10.1177/1365712718798656

Hepburn, A., and Bolden, G. B. (2012). “The Conversation Analytic approach to transcription,” in The Handbook of Conversation Analysis, eds. J. Sidnell, and T. Stivers. Chichester: Wiley Blackwell, 57–76.

Heritage, J., and Watson, R. (1979). “Formulations as conversational objects,” in Everyday Language. Studies in Ethnomethodology, ed. G. Psathas (New York, NY: Irvington Press), 123–162.

Jefferson, G. (1983). Issues in the transcription of naturally-occurring talk: caricature versus capturing pronunciational particulars. Tilburg Pap. Lang. Lit. 34, 1–12.

Jefferson, G. (2004). “Glossary of transcript symbols with an introduction,” in Conversion Analysis: Studies From the First Generation, ed. G. H. Lerner (Amsterdam; Philadelphia: John Benjamins), 13–31.

Komter, M. L. (2002–2003). The construction of records in Dutch police interrogations. Inf. Des. J. Docum. Des. 11, 201–213. doi: 10.1075/idj.11.2.12kom

Komter, M. L. (2003). The interactional dynamics of eliciting a confession in a Dutch police interrogation. Res. Lang. Soc. Interact. 36, 433–470. doi: 10.1207/S15327973RLSI3604_5

Komter, M. L. (2006). From talk to text: the interactional construction of a police record. Res. Lang. Soc. Interact. 39, 201–228. doi: 10.1207/s15327973rlsi3903_2

Komter, M. L. (2019). The Suspect's Statement: Talk and Text in the Criminal Process. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lynch, M. (2015). “Turning a witness: the textual and interactional production of a statement in adversarial testimony,” in Law at Work. Studies in Legal Ethnomethods, eds. B. Duprez, M. Lynch, and T. Berard (Oxord: Oxford University Press), 163–189.

Malsch, M., de Keijser, J., de Gruyter, M., Komter, M. L., and Elffers, H. (2012). Het Opmaken Van Proces-Verbaal Van Een Verdachtenverhoor: Ervaringen en Oordelen Van Verbalisanten [The Construction of a Police Report of Suspect Interrogations: Experiences and Opinions of Reporting Officers]. Amsterdam: NSCR report.

Moerman, M. (1988). Talking Culture. Ethnography and Conversation Analysis. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Mondada, L. (2007). Commentary: transcripts variations and the indexicality of transcribing practices. Discourse Stud. 9, 809–820. doi: 10.1177/1461445607082581

Mondada, L. (2014). “The temporal orders of multiactivity: operating and demonstrating in the surgical theatre,” in Multiactivity in Social Interaction. Beyond Multitasking, eds. P. Haddington, T. Keisanen, L. Mondada, and M. Nevile (Amsterdam; Philadelphia: John Benjamins), 33–75.

Mondada, L. (2018). Multiple temporalities of language and body in interaction: Challenges for transcribing multimodality. Res. Lang. Soc. Interact. 51, 85–106. doi: 10.1080/08351813.2018.1413878

Mondada, L., and Svinhufvud, K. (2016). Writing-in-interaction. Studying writing as a multimodal phenomenon in social interaction. Lang. Dialog. 6, 1–53. doi: 10.1075/ld.6.1.01mon

Sacks, H., Schegloff, E. A., and Jefferson, G. (1974). A simplest systematics for the organization of turn-taking for conversation. Language 50, 696–735. doi: 10.1353/lan.1974.0010

Slembrouck, S. (2007). Transcription - the extended directions of data histories: a response to M. Bucholtz's ‘Variation in transcription'. Discourse Stud. 9, 822–827. doi: 10.1177/1461445607082582

Smith, D. (1974). The social construction of documentary reality. Sociol. Inquiry 44, 257–268. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-682X.1974.tb01159.x

Smith, D. (2001). Texts and the ontologies of organization. Stud. Cult. Organ. Soc. 7, 159–198. doi: 10.1080/10245280108523557

Van den Adel, H. M. (1997). Handleiding Verdachtenverhoor. Handhaving, Controle en Opsporing in de Praktijk (Manual for Suspect Interrogation. Upholding the Law, Control and Detection in Practice). Den Haag: VUGA.

Watson, R. (2009). Analysing Practical and Professional Texts: A Naturalistic Approach. Farnham: Ashgate.

Whalen, J. (1995). “A technology of order production: computer-aided dispatch in public safety communication,” in Situated Order. Studies in the Social Organization of Talk and Embodied Activities, eds. P. Ten Have, and G. Psathas (Washington, DC: University Press of America), 187–230.

Keywords: conversation analysis, police interrogations, transcription, multiactivity, ethnomethodology

Citation: Komter M (2022) Institutional and Academic Transcripts of Police Interrogations. Front. Commun. 7:797145. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2022.797145

Received: 18 October 2021; Accepted: 03 March 2022;

Published: 12 August 2022.

Edited by:

Juan Carlos Valle-Lisboa, Universidad de la República, UruguayReviewed by:

Lorenza Mondada, University of Basel, SwitzerlandChuanyou Yuan, Guangdong University of Foreign Studies, China

Renata Galatolo, University of Bologna, Italy

Copyright © 2022 Komter. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Martha Komter, bWtvbXRlckBuc2NyLm5s

Martha Komter

Martha Komter