- School of Cultures, Languages and Area Studies, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, United Kingdom

Due to increasing mediatisation of societies and the global diffusion of English, previous research has paid a great deal of attention to the use of English in contact with other linguistic resources. Traditionally, the focus in studies on global Englishes is predominantly on verbal resources, which are often examined in media corpora. The recent paradigmatic shift towards a conceptualisation of language as a social practice, however, also acknowledges other resources such as music, images and sounds as part of semiotic assemblages in the process of meaning-making. This paper contributes to this current debate and argues for a more holistic view on language illustrated by examples of the use of global Englishes in German radio media texts. The examples show the complexities of translingual and transmodal practices in mass media communication and how English linguistic resources are deeply entangled with other semiotic resources and thereby locally appropriated in semiotic assemblages to stimulate the listener's visual imagination and achieve communicative success in a non-visual medium.

Introduction

When people think about language, they usually think of words and sentences in the form of oral conversations or written texts. This prioritisation of the verbal aspects of communication is also present in the study of English worldwide. The English language has been the centre of attention in the field of World Englishes, which is mainly interested in the spread and development of varieties of English across the globe (amongst others Kachru, 1985; Schneider, 2007; Mair, 2013; Onysko, 2016). In relation to the global dissemination of English linguistic resources, there is also research on what is frequently called anglicisms, namely English words and phrases that are used in many domains in localities of the expanding circle (Kachru, 1985) where English does not hold an official status, such as in France, Italy, Spain and Germany (Picone, 1996; Onysko, 2007; Furiassi, 2010; Pulcini et al., 2012; Andersen, 2015).

Recently, however, the predominant focus on verbal resources in the study of English worldwide has come under criticism since, when we take a closer look at communication, there is a lot more to say than what the focus on verbal language is able to reveal (see Pennycook, 2017, 2020; Canagarajah, 2018a; Li, 2018). There are, for example, sounds, silence, music and gestures that are language too since they are part of the semiotic practices we engage in. These modes, as they are called, are “socially shaped and culturally given semiotic resource[s]” (Kress, 2010, p. 79) and contribute a great deal to how we make meaning of the world and how we communicate it. According to Canagarajah, “these broader semiotic resources not only account for the meaning of words in an interaction, they themselves contribute meanings that need to be taken into account in order to explain intelligibility and communicative success in specific interactions” (2018a, p. 806).

Researchers in critical sociolinguistics have therefore drawn on the notion of multimodality as developed in social semiotics and related fields (amongst others Van Leeuwen, 1999; Bateman, 2008; Kress, 2010; Burn, 2014; Stöckl, 2016) to facilitate an analysis of meaning-making that goes beyond verbal resources in linguistic analyses and have at the same time developed this concept further. Rather than viewing meaning-making as a compilation of several, separate modes or independent channels of meaning, as implied by the term “multimodal” (Van Leeuwen, 1999; Kress, 2010), Pennycook (2007), for example, has proposed the term transmodality to describe the fact that verbal language does never occur in isolation but is always part of an assemblage of several semiotic modes. In addition, unlike the concept of multimodality, the notion of transmodality is rooted in the perspective that Blommaert (2010) has referred to as the sociolinguistics of mobility. In this paradigm, language is viewed as consisting of mobile linguistic resources, and the boundaries between individual “languages” are considered as socially and politically constructed. A key argument within this perspective is that we have to overcome the structuralist legacy that is inherently part of concepts such as “multilingualism” or “varieties of English,” which merely multiply the number of bounded “languages” and thereby reify the monolithic concept of language they originally have set out to supersede (cf. Kachru, 1985). The concept of transmodality therefore complements the critical sociolinguistic concepts of translingualism (Canagarajah, 2013) and translanguaging (Creese and Blackledge, 2011; Otheguy et al., 2015; Li, 2018), which state that people make use of a repertoire of various semiotic resources rather than of separate languages or varieties thereof. Such a holistic perspective on language also requires a re-evaluation of the traditional distinction between text and context since “features we may have treated as part of context may constitute an assemblage that is integral to meanings and communication” (Canagarajah, 2018b, p. 34). Taken together these critical concepts question the separability of different modes of meaning-making and call for a reconceptualisation of language as a trans-lingual, trans-semiotic and trans-modal practice. Against this theoretical background, Canagarajah (2013) and Pennycook (2007) use the term global Englishes to highlight the need for focussing on local social and cultural practices associated with the worldwide use of mobile Englishes.

In the light of these recent developments around the conceptualisation of language, this paper follows Canagarajah's (2018a) call to broaden the scope of analysis in research on the worldwide use of English by including other modes besides speech and writing but also by acknowledging the interaction between English and other linguistic resources in analyses of meaning-making. Taking Canagarajah's (2018a) example of the use of English in interpersonal workplace communication between non-native speakers of English as a point of departure, I will show that a translingual and transmodal perspective can also help us to better understand how English linguistic resources are embedded in the semiotic assemblages of representations of events in mass media messages. While recent studies on global Englishes in social media have already adopted translanguaging and transmodality approaches (Sharma, 2012; Sultana and Dovchin, 2017; Baker and Sangiamchit, 2019), the way journalists use English linguistic resources as part of transmodal assemblages to achieve communicative success in traditional mass media messages has been largely overlooked in World Englishes and anglicism research (amongst others Yang, 1990; Glahn, 2002; Mesthrie, 2002; Adler, 2004; Zenner et al., 2012; Makalela, 2013; Lee, 2014; Gottlieb, 2015). I will focus on German radio media in this paper since Germany is one of the localities in the expanding circle where present-day dynamics of mobile Englishes can be observed (Schneider, 2014; Onysko, 2016). The German radio media are not only affected by global cultural flows and the associated diffusion of English but are also part of the dissemination processes of new words, mostly in the form of anglicisms in Germany, as well as of Anglo-American popular culture including music, trends and technological advances (Schaefer, 2019, 2021a,b).

To compensate for radio's lack of visual elements, radio journalists rely on several auditory modes to produce meaning, which are orchestrated in a complex acoustic mix of mainly speech, music and sounds to grab the listeners' attention and to emulate a multisensory effect (Crisell, 1986; Shingler and Wieringa, 1998; Miller, 2018). People listen to the radio in many everyday contexts, such as at home, whilst driving or at the shopping centre. Therefore, radio functions as a background medium, and the components of a radio broadcast and how the medium's message is constructed to achieve communicative success often go unnoticed. I will show that this auditory-only medium reveals complex, transmodally composed meanings to stimulate the audience's imagination and to enable the listener to “visualise” events reported on by journalists. These transmodally composed meanings are worthy of our attention to improve our understanding of the functions of English linguistic resources and their local appropriation through their entanglement with other semiotic resources in mass-mediated communication. For my examples of radio texts, I draw on a large adult contemporary1 radio corpus containing 60 h of radio morning show content, which I compiled in 2016 as part of a larger, ongoing research project on the use of English linguistic resources by German radio journalists. While I focus on the embeddedness of English linguistic resources in semiotic assemblages in the two examples below, there are also other factors that shape the use of global Englishes by German radio journalists, which I have elaborated on in previous studies. These include broadly speaking, the individual journalist (including his/her language perceptions) (see Schaefer, 2021a), the media organisation (including radio format, genre and domain) (see Schaefer, 2019, 2021a), the broadcasting system (public service vs. private radio stations) and the global/cultural background (see Schaefer, 2021b).

Semiotic Assemblages on German Radio

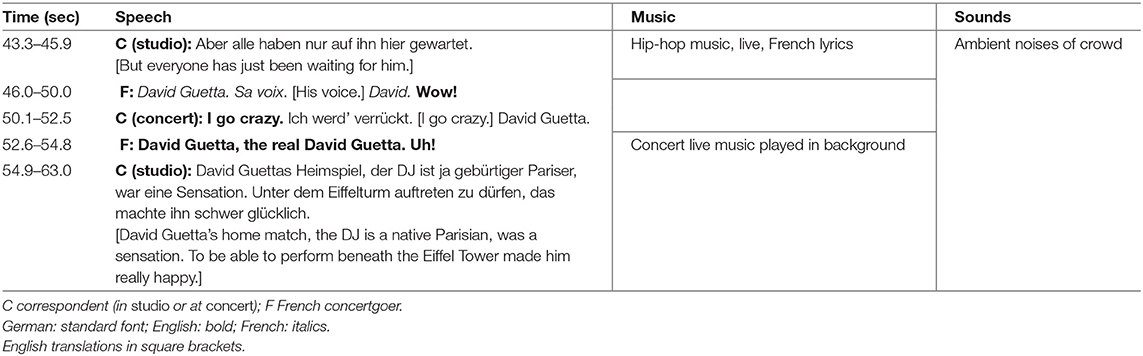

The first example from German radio that highlights the complex interplay of modes and the role of English in this context is a foreign correspondent's report about a concert which took place in the context of the 2016 European football championship in France. The excerpt shown in Table 1 is taken from a report (90 s in length) in which the correspondent shares his experiences of the concert held in the fan area beneath the Eiffel Tower with the radio station's audience back in Germany. The report begins with a description of the security checks necessary for concertgoers to be admitted to the actual event, which contains several French utterances played in the background and a French direct quote of a concertgoer (translated into German by the correspondent). These elements set the scene of the large-scale event at the Eiffel Tower and are used by the journalist to create authenticity. The excerpt from the journalistic piece in Table 1 shows how the concert audience has experienced the highlight of the event, the performance of the French DJ David Guetta.

As becomes evident from this example, the modes of sound, speech and music interact to create an authentic representation of the concert happenings and to allow the listener to generate a visual image of the event. The report consists of narrative parts recorded by the journalist in studio and of on-scene recordings, which becomes evident to the listener through the change in sound characteristics between the portable recorder and the in-studio recording equipment. Throughout the report, the atmosphere on location is upheld by ambient noises of the large crowd at the concert and at times live music played in the background. The correspondent takes on two distinct personae in the report, which are also mirrored in his linguistic choices. Through the voiceover narration recorded in studio, he acts as an omniscient narrator, who addresses his radio audience and comments on the happenings from an observer's perspective using past tense.

On location, however, the reporter's role is more complex. In contrast to his factual tone in the omniscient narration in studio, the foreign correspondent's word choice and voice at the scene mirror the international setting and the cheering atmosphere at the concert. His excitement for the appearance of the DJ is expressed by the tone of his voice when he shouts “I go crazy. Ich werd' verrückt. David Guetta.” On location, the correspondent is part of the crowd, therefore, a participant at the event interacting with other concertgoers. This becomes evident from non-verbal features such as the loudness and clarity of the voices of both the journalist and a French concertgoer, in contrast to the ambient sound of the crowd cheering at the concert, implying that the two are interlocutors standing next to each other, addressing each other. In their short conversation, the German correspondent and the French spectator perform translanguaging by means of the two interlocutors making use of their expanded language repertoire in the form of English resources. In addition, what is interesting to note here is that the utterance “I go crazy. Ich werd' verrückt. David Guetta” by the journalist indicates that his message is not only a response to the French concertgoer's exclamation, but that the translation of I go crazy by the correspondent is additionally directed at the radio audience at home in Germany, allowing the listener to become part of the excitement shared by the two concertgoers in conversation. The journalist's interactions at the scene therefore connect several communicative levels. In addition to his role as a participant of an international event on location, the correspondent moves into the role of the reporter who caters for his radio audience's linguistic needs in terms of comprehensibility on a translocal level. In line with the reporter's dual role on location, the English phrase I go crazy also has a dual function. On the one hand, it is part of his translingual practice with the French concertgoer, where the journalist makes use of shared English resources to facilitate communication with his immediate surroundings at the concert. On the other hand, it functions to symbolise the international character of the event (in conjunction with the French elements) for the radio station's audience. This dual function of the English phrase only becomes evident through the transmodal assemblage of verbal resources (i.e., the translation for the German radio audience) and non-verbal features, as mentioned above, creating an image of spatial proximity between the two concertgoers.

This example reveals a complex orchestration of English linguistic resources and other semiotic resources that acoustically reconstructs the highlight of the international event for the German target audience, stimulating the listener's visual imagination of the event and thereby connecting the local radio audience to a more global context. It additionally demonstrates that taking a closer look at these transmodal representations of events in mass-mediated communication allows us to reveal complex communicative functions of English linguistic resources deeply entangled in semiotic ensembles that contribute to achieving communicative success.

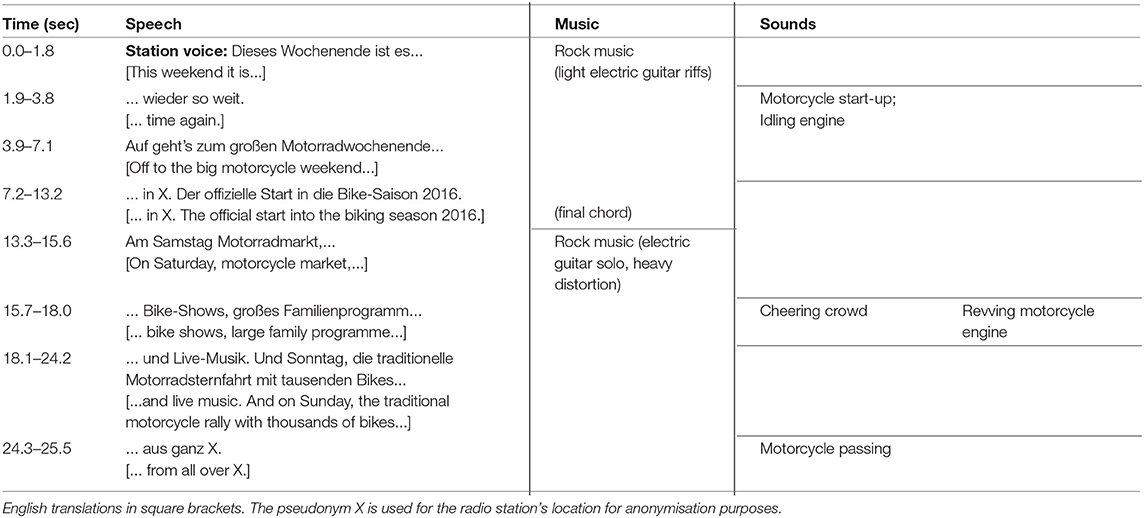

The second example from German radio shown in Table 2 is a promotion piece about an event sponsored by a radio station in which English loanwords are used. I will focus on the function of the English linguistic resource Bike, appearing also in the compound nouns Bike-Saison “biking season” and Bike-Show in the promotion piece, and how it is embedded in the ensemble of semiotic modes. When we consider the lexical meaning of Bike, the loanword is polysemous in German and can refer to different classes of two-wheeled vehicles, namely bicycles and motorcycles2. More specifically, it can be used to refer to various types of these vehicles, such as mountain bikes, pedelecs, superbikes and cruiser motorbikes. The actual meaning of the term in this promotion piece and therefore the type of event advertised by the radio station only becomes evident through the transmodal assemblage it is used in.

Let us first look at some further clues on the verbal level. The use of the German word Motorrad “motorcycle” as modifier of the compound noun Motorradwochenende “motorcycle weekend” in the promotion piece gives some indications that the event will centre around motorised vehicles, instead of bicycles. However, even in combination the English and German linguistic resources only give a rough idea of what the event is about since, in this sense, they are both hypernyms for a class of vehicles, which still leaves uncertainty regarding the type of motorcycles the event centres around. The modes of sound and music close this gap by creating an acoustic image, a soundscape so to speak, of the event. The engine sounds accompanying the promotion conjure up images of heavy choppers or cruisers which evoke stereotypes associated with the American motorcycle brand Harley Davidson or similar brands. This imagery is supported by the rock music played in the background, which together with the engine sounds rather conjures up German clichés of American motorcycle ideology often related to US-specific cultural concepts such as the Route 66 and the motion picture Easy Rider, rather than to the Moto GP racing series. The English linguistic resource Bike, therefore, functions in orchestration with the stereotypic engine sounds and the rock music played in the background to represent American biker ideology and lifestyle. This imagery conveyed at the opening of the promotion piece is additionally strengthened by the term Bike-Show, which in this context relates the event to a particular type of motorcycle competition originating in the USA.

What is interesting to note here, however, is that the sounds of heavy chopper or cruiser bike engines and the rock music played together with the information provided verbally to this point may lead to a misinterpretation by the target audience regarding the type of event promoted. The event is seemingly portrayed as a meeting of this particular biker community only or at best motorcycle enthusiasts who share an interest in American motorcycle culture more generally. To avoid such unintended interpretations on behalf of the listener, the station has included additional verbal clues by using the phrase großes Familienprogramm “large family programme,” which reframes the meaning of the promotion piece and the meaning of the semiotic resources used to this point by portraying an event that everyone who wants to have a good time can attend.

As this example shows, the actual function of the English word Bike in this piece only becomes evident from the interplay of the different modes of speech, music and sounds used to acoustically represent this social event, which together provide a description of the American atmosphere that the station's audience can expect to find when attending this particular event. This semiotic ensemble, however, becomes reframed onto a local scale by making clear on a verbal level through other linguistic resources that this is an event adapted to a wide and at the same time local audience. The meaning of the English loanword Bike in this context is therefore co-constructed through its embeddedness in an assemblage of the modes of music, speech and sound, which together kindle a visual imagery of the event with the listener.

The Need for a Critical Perspective on Mass Media Language

As my examples from German radio content have shown, a holistic, translingual and transmodal approach acknowledging semiotic assemblages can widen our understanding of the complex entanglements of English linguistic resources with other semiotic resources and thereby of their local appropriation in mass media content. In line with Canagarajah's (2018a) observations, the examples discussed in this paper have furthermore revealed how these diverse semiotic resources are used by journalists on radio to achieve communicative success. Sounds, music and speech all contribute meaning in human interaction. Sounds and music can co-construct the meaning of a verbal resource, which shows that other semiotic resources besides speech are not simply part of the context but an intrinsic part of translingual practices. Furthermore, we have seen that various semiotic resources are used on radio to substitute the missing visual elements by creating acoustic representations of events stimulating the listener's imagination. As stated by Canagarajah (2018a), Li (2018), and Pennycook (2017, 2020), in times of increased mobility of cultural and linguistic resources across space and time, it is necessary to make way for new approaches to language that allow for a better understanding of linguistic and cultural diversity and of the communicative functions of English in its entanglements with other semiotic resources in the expanding circle and beyond. Especially since global Englishes can be found in various communicative formats and contexts around the world—including on public signage, in the media, in classrooms, or at the workplace—we need to broaden our conceptualisation of language to allow for a deeper insight into social practices of meaning-making at large.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author Contributions

SS was the sole author of this article. Data used in this article was compiled by SS.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^Adult contemporary stations target an audience between 25 and 49 years of age and play mainstream pop-music.

2. ^see ‘Bike', in: DWDS – Digitales Wörterbuch der deutschen Sprache, edited by Berlin-Brandenburgische Akademie der Wissenschaften. Available online at: https://www.dwds.de/wb/Bike (accessed June 20, 2021).

References

Adler, M. (2004). Form und Häufigkeit der Verwendung von Anglizismen in deutschen und schwedischen Massenmedien. [PhD dissertation]. Jena: Friedrich Schiller University Jena.

Andersen, G. (2015). “Pseudo-borrowings as cases of pragmatic borrowing: Focus on anglicisms in Norwegian,” in Pseudo-English: Studies on False Anglicisms in Europe, eds C. Furiassi and H. Gottlieb (Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton). doi: 10.1515/9781614514688.123

Baker, W., and Sangiamchit, C. (2019). Transcultural communication: Language, communication and culture through English as a lingua franca in a social network community. Lang. Intercult. Commun. 19, 471–487. doi: 10.1080/14708477.2019.1606230

Bateman, J. A. (2008). Multimodality and Genre: A Foundation for the Systematic Analysis of Multimodal Documents. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan. doi: 10.1057/9780230582323

Blommaert, J. (2010). The Sociolinguistics of Globalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511845307

Burn, A. (2014). “The kineikonic mode: Towards a multimodal approach to moving-image media,” in The Routledge Handbook of Multimodal Analysis, 2nd edition, ed C. Jewitt (London: Routledge).

Canagarajah, S. (2013). Translingual Practice: Global Englishes and Cosmopolitan Relations. Abingdon: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203073889

Canagarajah, S. (2018a). The unit and focus of analysis in lingua franca English interactions: In search of a method. Int. J. Bilingual Educ. Bilingualism 21, 805–824. doi: 10.1080/13670050.2018.1474850

Canagarajah, S. (2018b). Translingual practice as spatial repertoires: Expanding the paradigm beyond structuralist orientations. Appl. Linguist. 39, 31–54. doi: 10.1093/applin/amx041

Creese, A., and Blackledge, A. (2011). Separate and flexible bilingualism in complementary schools: Multiple language practices in interrelationship. J. Pragmatics 43, 1196–1208. doi: 10.1016/j.pragma.2010.10.006

Glahn, R. (2002). Der Einfluß des Englischen auf gesprochene deutsche Gegenwartssprache: Eine Analyse öffentlich gesprochener Sprache am Beispiel von “Fernsehdeutsch”. 2nd edition. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.

Gottlieb, H. (2015). “Danish pseudo-anglicisms: A corpus-based analysis,” in Pseudo-English: Studies on False Anglicisms in Europe, eds C. Furiassi and H. Gottlieb (Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton). doi: 10.1515/9781614514688.61

Kachru, B. B. (1985). “Standards, codification and sociolinguistic realism: The English language in the Outer Circle”, in English in the World: Teaching and Learning the Language and Literatures, eds R. Quirk and H.G. Widdowson (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Kress, G. R. (2010). Multimodality: A Social Semiotic Approach to Contemporary Communication. London: Routledge.

Li, W. (2018). Translanguaging as a practical theory of language. Appl. Linguistics 39, 9–30. doi: 10.1093/applin/amx039

Mair, C. (2013). The world system of Englishes: Accounting for the transnational importance of mobile and mediated vernaculars. English World-Wide 34, 253–278. doi: 10.1075/eww.34.3.01mai

Makalela, L. (2013). Black South African English on the radio. World Englishes 32, 93–107. doi: 10.1111/weng.12007

Mesthrie, R. (2002). Mock languages and symbolic power: The South African radio series Applesammy and Naidoo. World Englishes 21, 99–112. doi: 10.1111/1467-971X.00234

Miller, B. M. (2018). “The pictures are better on radio”: A visual analysis of American radio drama from the 1920s to the 1950s. Histor. J. Film Radio Television 38, 322–342. doi: 10.1080/01439685.2017.1332189

Onysko, A. (2007). Anglicisms in German: Borrowing, Lexical Productivity, and Written Codeswitching. Berlin: De Gruyter. doi: 10.1515/9783110912173

Onysko, A. (2016). Modeling World Englishes from the perspective of language contact. World Englishes 35, 196–220. doi: 10.1111/weng.12191

Otheguy, R., García, O., and Reid, W. (2015). Clarifying translanguaging and deconstructing named languages: A perspective from linguistics. Appl. Linguistics Rev. 6, 281–307. doi: 10.1515/applirev-2015-0014

Pennycook, A. (2007). Global Englishes and Transcultural Flows. Abingdon: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203088807

Pennycook, A. (2017). Translanguaging and semiotic assemblages. Int. J. Multilingual. 14, 269–282. doi: 10.1080/14790718.2017.1315810

Pennycook, A. (2020). Translingual entanglements of English. World Englishes 39, 222–235. doi: 10.1111/weng.12456

Picone, M. D. (1996). Anglicisms, Neologisms and Dynamic French. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. doi: 10.1075/lis.18

Pulcini, V., Furiassi, C., and Rodríguez González, F. (2012). “The lexical influence of English on European languages: From words to phraseology,” in The Anglicization of European Lexis, eds C. Furiassi, V. Pulcini and F. Rodríguez González (Amsterdam: John Benjamins), 1–26. doi: 10.1075/z.174.03pul

Schaefer, S. J. (2019). Anglicisms in German media: Exploring catachrestic and non-catachrestic innovations in radio station imaging. Lingua 221, 72–88. doi: 10.1016/j.lingua.2019.01.002

Schaefer, S. J. (2021a). English on air: Novel anglicisms in German radio language. Open Linguistics 7, 569–593. doi: 10.1515/opli-2020-0174

Schaefer, S. J. (2021b). Hybridization or what? A question of linguistic and cultural change in Germany. Globalizations 18, 667–682. doi: 10.1080/14747731.2020.1832839

Schneider, E. W. (2007). Postcolonial English: Varieties Around the World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511618901

Schneider, E. W. (2014). New reflections on the evolutionary dynamics of World Englishes. World Englishes 33, 9–32. doi: 10.1111/weng.12069

Sharma, B. K. (2012). Beyond social networking: Performing global Englishes in Facebook by college youth in Nepal. J. Sociolinguist. 16, 483–509. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9841.2012.00544.x

Stöckl, H. (2016). “Multimodalität - Semiotische und textlinguistische Grundlagen,” in Handbuch Sprache im multimodalen Kontext, eds N. Klug and H. Stöckl (Berlin: De Gruyter). doi: 10.1515/9783110296099-002

Sultana, S., and Dovchin, S. (2017). Popular culture in transglossic language practices of young adults. Int. Multilingual Res. J. 11, 67–85. doi: 10.1080/19313152.2016.1208633

Van Leeuwen, T. (1999). Speech, Music, Sound. London: Macmillan Education. doi: 10.1007/978-1-349-27700-1

Yang, W. (1990). Anglizismen im Deutschen: Am Beispiel des Nachrichtenmagazins Der Spiegel. Tübingen: Niemeyer. doi: 10.1515/9783111676159

Keywords: global Englishes, German, transmodality, translanguaging, radio, media, semiotics, mobility

Citation: Schaefer SJ (2022) Global Englishes and the Semiotics of German Radio—Encouraging the Listener's Visual Imagination Through Translingual and Transmodal Practices. Front. Commun. 7:780195. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2022.780195

Received: 20 September 2021; Accepted: 16 February 2022;

Published: 05 April 2022.

Edited by:

Peter Siemund, University of Hamburg, GermanyReviewed by:

Sebastian Knospe, Polizeiakademie Niedersachen, GermanyJaime Hunt, The University of Newcastle, Australia

Copyright © 2022 Schaefer. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sarah Josefine Schaefer, c2FyYWguc2NoYWVmZXJAbm90dGluZ2hhbS5hYy51aw==

Sarah Josefine Schaefer

Sarah Josefine Schaefer