94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

BRIEF RESEARCH REPORT article

Front. Commun., 15 December 2022

Sec. Multimodality of Communication

Volume 7 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2022.1059131

This article is part of the Research TopicRecontextualization: Modes, Media, and PracticesView all 6 articles

The profound establishment of text-based interaction via mobile messenger services has not only changed interpersonal communication, but also reshaped its quotability. Drawing on the notion of recontextualization, this paper investigates the cross-media transfer-and-transformation of text messages from their former confidential contexts into public media environments. The data are drawn from the media discourse on the corruption affair of the Austrian People's Party (ÖVP), which was triggered by the publication of confidential chat messages in the fall of 2021. Comparing the presentation of text messages in the journalistic media with their intertextual antecedents (in investigative files and related documents), the analysis highlights several linguistic and visual transformations. The findings demonstrate how formerly private chat interactions have been represented in media discourse and reveal different multimodal forms of cross-media quotation, ranging from linguistic replay and visual restaging to elaborate forms in which text messaging is audio-visually re-enacted. These modes of cross-media recontextualization differ in the degree to which the mediality of the digital chat discourse is conveyed or imitated. Through this media linguistic lens, the study contributes to the theory of recontextualization and raises the question what concept of quotation and re-enactment is appropriate and linguistically due in the age of a deep digitalization of everyday communication.

Instant messaging (IM) technology has significantly changed the way we communicate in everyday life. Chat is one of the earliest Internet services and modern IM applications rank among the most widely used smartphone apps. In a very broad sense, chat discourse can be characterized as a form of computer-mediated communication (CMC): dialogic, sequentially organized interchanges conducted via communication technologies (Beißwenger and Lüngen, 2020; p. 1). While linguistic research on quotation has explored recontextualization in various CMC genres (Bublitz and Hoffmann, 2011; Arendholz, 2015; Gruber, 2017), less attention has been paid to cross-media recontextualization of CMC and IM chat.

Following Linell (1998), I consider cross-media recontextualization as the transfer-and-transformation of discourse fragments from one medial environment (in this case: IM apps) to a distinctly different environment (e.g., online forums, newspapers, television broadcasts, etc.). As such, cross-media recontextualization entails not only a shift in meaning, but also a shift in semiotic modes. Cowan and Kress (2017, p. 53) have stressed that cross-mode transfer of meaning, such as in the transcription of research data, “is never a simple process of “replication” but a process of “re-constitution” or “re-materialization.” It is always the making of a new sign.” From this multimodal perspective, cross-media recontextualization always relies on specific means of notation. For instance, one may use screenshots as a notational resource to share chat conversations in an online forum. Using such notational resources transforms the original discourse fragments and creates new materials, like IM chats turning into static image files, and introduces entirely new affordances, like the ability to label and pixelate (Pfurtscheller, 2022).

Cross-media recontextualization of chat discourse also has the potential to transform addressee and visibility, turning private conversations into public ones. Unlike (semi-)public forms of CMC conducted via online forums and social media platforms, mobile IM services (such as WhatsApp, iMessage, Signal, WeChat, etc.) are generally geared toward private use. This feature is particularly relevant in the case of journalistic reporting and quoting in the media (Haapanen and Perrin, 2017). While public social media posts on Twitter and Instagram regularly surface as journalistic sources and thus become part of (digital) news stories (Bouvier, 2019; Johansson, 2019), public recontextualization of private chat messages usually only occurs in the case of leaked documents (Pollak, 2021).

This paper explores the public recontextualization of private IM chat discourse in the case of the Austrian People's Party (ÖVP) corruption affair, a case in which journalists had to report on a large influx of private chat messages from high-ranking politicians. In 2021, a corruption probe and the disclosure of IM chat messages led, among other things, to the resignation of Austrian Chancellor Sebastian Kurz. During its investigations, the public prosecutor's office responsible for corruption had seized several cell phones, including that of Thomas Schmid, a civil servant loyal to Kurz's conservative party and a close intimate of the chancellor. Schmid was secretary general of the finance ministry under Kurz' leadership and later head of Austrian state holdings group ÖBAG, a state-owned holding company that acts as a sovereign wealth fund. As of June 30, 2022, ÖBAG controls 10 state-owned investments with a total value of ~33.13 billion euros (ÖBAG, 2022). In June 2021, Thomas Schmid was forced to resign as director (Murphy, 2021). In October 2021, raids were carried out at the central office of the Austrian People's Party (ÖVP) and at the Ministry of Finance (Klenk and Staudinger, 2021; Nikbakhsh and Melichar, 2021). Due to the accusations of embezzlement and bribery, Sebastian Kurz resigned as Chancellor on October 9. The former “political wunderkind” (Karnitschnig, 2021) announced his complete retirement from politics in December 2021 and now works for tech billionaire Peter Thiel (Eder, 2021).

This incident provides an ideal opportunity to explore different modes by which chat discourse is recontextualized across media. In media coverage, private chat messages were quoted extensively, and considering the political controversy, several Austrian media outlets also published the full (albeit partially redacted) investigation files and forensic chat transcripts (Klenk and Staudinger, 2021; Nikbakhsh and Melichar, 2021; zackzack.at, 2021). In addition to traditional forms of quoting, the novel situation of having to report on chats has also led to more innovative modes. Approaching these quotation practices as a cross-media recontextualization, I examine the ways in which the leaked IM chat discourse is covered in Austrian news media. My goal is to identify distinct types of cross-media recontextualization. For this, I focus on two research questions: In what ways and with which notational resources are chat messages recontextualized? And how is the specific mediality of IM communication taken into account in cross-media recontextualization?

To examine the cross-media recontextualization of IM chat discourse, I collected two data sets. For journalistic news coverage, I compiled a corpus of print and online articles, as well as television news broadcasts. I used the APA Defacto database, which contains all Austrian daily newspapers, radio and TV broadcasts, magazines, and specialized media. This large database is suitable for a multimodal analysis, because not only text, but also the original layout of news stories is provided. For data collection, I searched the archive for the appropriate keywords (“chat,” “text messages,” etc.), filtered the results manually and compiled a corpus of the full texts. In the case of the news broadcasts, I limited myself to the public service offerings. The program Zeit im Bild of the Austrian Broadcasting Corporation (ORF) is one of the most important and most watched programs in Austria. Selected news broadcasts featuring leaked IM chats were retrieved from the archives of the ORF and processed by transcription for the multimodal analysis.

The second data set containing investigation files and forensic data was created to survey the source baseline of journalistic coverage. These files have been sourced from media reports and internet searches. Since there are often multiple versions of the documents in circulation and the PDF files are searchable in different ways, I merged the transcripts, OCRed them, and prepared them for comparison with the media coverage. The level of redaction of personal information in these leaked documents varies. I am aware of the ethical issues, and in conducting my investigation I was very careful not to further disclose or disseminate any personal information about individuals that appeared in the investigation files. Since much of the material has already been publicized and widely distributed by Austrian media, it can be assumed that this study will have no negative impact in this regard.

To identify and group the types of cross-media recontextualization, I used qualitative methods of multimodal analysis. Following Ledin and Machin (2019) I considered the texts as “meaningful wholes,” examining the outer form/contextual configuration and inner structure/design of the recontextualized semiotic materials. On this basis, I have clustered the emergent forms of cross-media representation into groups. The selection process was iterative. In several circles, I selected and examined media reports until reaching saturation, meaning that no new forms of recontextualization emerged in the material. In this manner, I analyzed in detail a total of 36 out 190 items. Focusing on distinctive differences in the way IM messages are rendered, I then attempted to name and explain the specific features of cross-medial recontextualization based on prototypical examples.

The media coverage of the ÖVP corruption affair is centered on providing textual evidence. To present this evidence, practitioners employ different forms of cross-media recontextualization. The qualitative analysis revealed four types or modes of cross-media recontextualization, covering procedures of transcription, textual replay, visual restaging, and multimodal reenactment (see Figure 1).

The first recontextualization procedure involves transcription. During the corruption probe, the formerly private IM chats, some of which were deleted by the participants, are reconstructed from various storage media and backups, and transfered/transformed into forensic transcripts. This entextualization (Bauman and Briggs, 1990) of the chat discourse as forensic transcripts is the initial, crucial step in an intertextual chain that constitute a shift from private to increasingly public contexts.

Journalistic modes of cross-media recontextualization differ in the way the mediality of the chat discourse is handled. The analysis revealed a varying extent to which the mediality of IM communication is reduced or even restaged and fabricated. A very common form of transfer is the reproduction of individual scripted chat messages by way of direct quotations. Such forms of textual replays feature solely linguistic modes of reproduction, in which the chat messages are rendered using common forms of quotation and incorporated straight into the body of the news story. Since the only available means of notation are written language or speech, the mediality of the chats can only be marked on a linguistic meta-level. The original mediality of IM chat communication is thereby very much reduced. In many cases, all that remains is the remark that quoted statements originate from IM chats. I call these procedures of invoking the original context by means of meta-communicative indications medial indexing.

On the other hand, there are also forms of recontextualization in which the media environment of IM chat discourse is recreated using visual means. In contrast to textual replay, such forms of visual restaging present the quoted chat discourse in their sequential context, replicating the usual look of IM apps. Such procedures of restaging mediality can be labeled as medial mimicry.

As a third possibility, the analysis of news videos has identified forms of multimodal reenactment. In addition to the visual restaging, the chat communication here is not only recreated by the media, but also extended by additional semiotic means. In these dynamic forms of recontextualization, the chat sequences are dynamically faded in and re-voiced by narrators. Through a procedure that can be called semiotic extension, the original mediality of the IM messages is changed (for example, by shortening the sequences in time) and amplified (for example, through visual and prosodic shaping).

In what follows, I focus on and elaborate these three modes and procedures of cross-media recontextualization in news media.

Following a common pattern, journalistic reporting is typically characterized by the interweaving of individual quotes into a text. Journalists “shift back and forth in their production of news when looking for material and embedding it into a new textual context” (Johansson, 2019, p. 134). One option for cross-media recontextualization is to reproduce excerpts from IM chat discourse as written quotations, using common journalistic recontextualization procedures (Haapanen, 2017). Consider the following examples from three different news stories, all relating to the same chat interaction that points to possible corruption in the appointment of the chief executive of ÖBAG, a holding company of Austrian state-owned enterprises.

(1) Als die gesetzliche Grundlage für den neuen Posten in der ÖBAG gegeben war, schrieb Blümel—damals Kanzleramtsminister—an Schmid: “Schmid AG fertig.” Dieser antwortete: “Habe noch keinen Aufsichtsrat” (FAZ).

When the legal basis for the new post at ÖBAG was in place, Blümel—then Minister of the Chancellor's Office—wrote to Schmid: “Schmid Co. done.” The latter replied: “Don't have a supervisory board yet” (FAZ).

(2) Nachdem das neue ÖBAG-Gesetz am 11. Dezember 2018 im Nationalrat beschlossen wurde, kommentiert das der damalige Regierungskoordinator Blümel in einer Nachricht an Schmid so: “SchmidAG fertig!” Und fügt ein Bizeps-Emoji hinzu (Kurier.at).

After the new ÖBAG law was passed in the National Council on December 11, 2018, Blümel, the government coordinator at the time, commented in a message to Schmid: “SchmidCo. done!” And adds a biceps emoji (Kurier.at).

(3) “Schmid AG fertig!,” kommentierte das Blümel in einer Nachricht unter Hinzufügung eines Kräftigen-Oberarm-Emojis (Standard.at).

“Schmid Co. done!,” Blümel commented in a message, adding a strong-upper-arm emoji (Standard.at).

The quoted excerpts are extracted from dialogical sequences of chat discourse and presented in the form of isolated direct quotations. In textual replays of the chat discourse, the mediality of the IM services is not apparent and recedes into the background. Embedded in the news story, the extracts are recontextualized as chat messages only through meta-linguistic means (using meta-communicative labels like chat message, in a message to, etc. or with the use of verba dicendi like wrote, comments etc.). An interesting detail is the question of how the emojis, which appear in great numbers in the original IM chats, are dealt with in recontextualization. No textual replays in the data set reproduce the emojis as such in direct quotations. What can be observed instead is meta-communicative commentary on emoji usage, as in examples (2) and (3) above This, too, can be considered part of the reflexive procedure of medial indexing, pointing to the media origins of the IM chat discourse.

Such textual replay of IM chat discourse leads to fragmented and highly selective recontextualization of isolated fragments. Figure 2 shows a comparison of three online articles. All three articles are among the first online articles on the case and were all published around noon on 28/3/2021. In the visualization, direct quotations from the investigation files are shown in red, and direct quotations from other sources are shown in blue. Some editorial notes are also present in the direct quotations (marked green). All articles open by contextualizing the story. The first step is to explain what happened and to provide background information about the investigation and the people involved. Direct quotes then follow in the latter half of the text. In particular, the article from Presse.com is very quote-heavy in the second half. The other two articles also quote other sources. At the end of the Derstandard.at article, for example, politicians from the opposition have their say, and their reactions to the publication are also quoted by Kurier.at. The journalists' goal here is not to reconstruct single conversations in detail. Rather, the aim is to establish contexts and clarify what is newsworthy about the documents that have emerged. For this purpose, a textual replay of the chat discourse is adequate. On the one hand, the contextualization provides a temporal framework. The incidents extend over a period of multiple years. Most of the chat messages quoted are several years old. Also, the confrontation of the statements made at that time (in the chats) with recent comments, newly obtained from the persons concerned, is an important aspect.

Given the inherent multimodality of IM chat discourse, reporting on the leaked conversations lends itself to a more visual form of presentation that goes beyond direct quotes. The study identified several modes of cross-media recontextualization that recreated the chat messages through visual means, mimicking the aesthetics of IM chat. These include all forms of recontextualization in which the chat discourse is placed in a visual arrangement that mimics the medial environment of IM apps and services. In other words, the mediality of the IM chat sequences is being emulated and visually fabricated. This form of recontextualization can be called visual restaging because there are no authentic screenshots, but the IM chat discourse reconstructed from the leaked investigative files is repackaged into chat visuals. For this purpose, various features of the media environment of IM chats are mimicked.

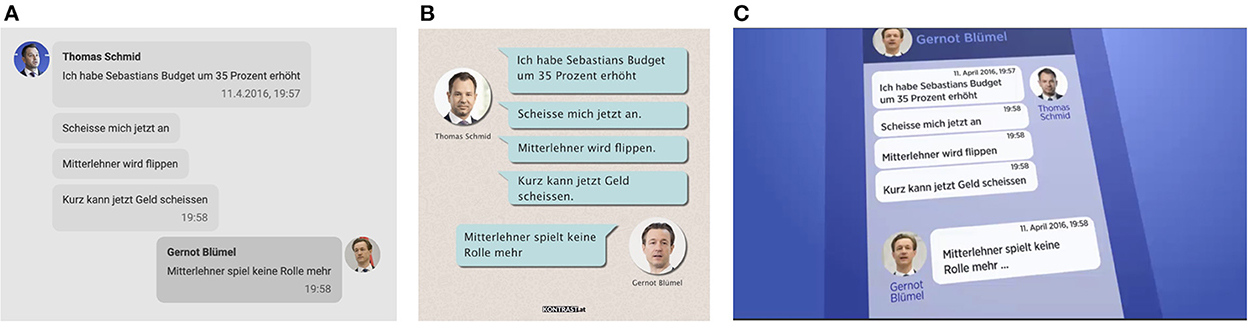

Figure 3 shows excerpts from three different examples of journalistic media coverage that showcase this medial mimicry in cross-media recontextualization. In all three of them, the same chat interaction is being restaged. While there are some minor differences in visual design, the same conventionalized forms of presentation are used in all of them. All examples show the IM chat in its interaction sequence by visually restaging the chat discourse in a custom-made “screen protocol,” a basic unit of CMC (Beißwenger and Lüngen, 2020, p. 10). The individual posts are represented using colored rectangles (in B they are speech bubbles). In (A) and in (C) these posts are also marked via timestamps. In addition, there are small portrait pictures of the two interlocutors, which are also labeled with names in (B) and (C). This design element of the portrait pictures indicates the visual fabrication of the chat transcripts, as it does not belong to the typical interface design of IM apps.

Figure 3. Three examples of cross-media recontextualization through visual restaging of chat discourse. (A) derstandard.at, (B) kontrast.at, and (C) Zeit im Bild.

Through this visual restaging, the recontextualized discourse segments are showcased as IM chat messages. While cross-media quotation in the mode of textual replay weaves textual messages very selectively into the article text, visual restaging aims to map the textual messages into a fabricated interaction environment. The mediality of IM communication is more clearly recreated by this visual design than forensic protocols do. By presenting a fabricated IM chat environment, these forms of cross-media recontextualization foreground mediality very clearly. Due to the multimodal design, however, contextualizing cues that are called for in the coverage are not integratable within the visual ensemble. As forms of cross-media recontextualization, visual restaging therefore rarely stands alone, but functions as a node of larger news stories in which other forms of cross-media recontextualization also occur.

As a third mode of cross-media recontextualization, the study identified forms in which the IM chat discourse is not only presented in visually restaged IM environments, but also re-enacted to a much greater extent. This is particularly evident in the case of TV news coverage. Here, the IM chat discourse is recontextualized in the form of multimodal reenactments, where chat messages are displayed using dynamic graphic animations and re-voiced by journalists. Thus, in these forms of recontextualization, even more semiotic qualities are added that were not present in the original media context. As a result, the IM chat discourse is not only contextualized, but also semiotically transformed and extended by the journalists.

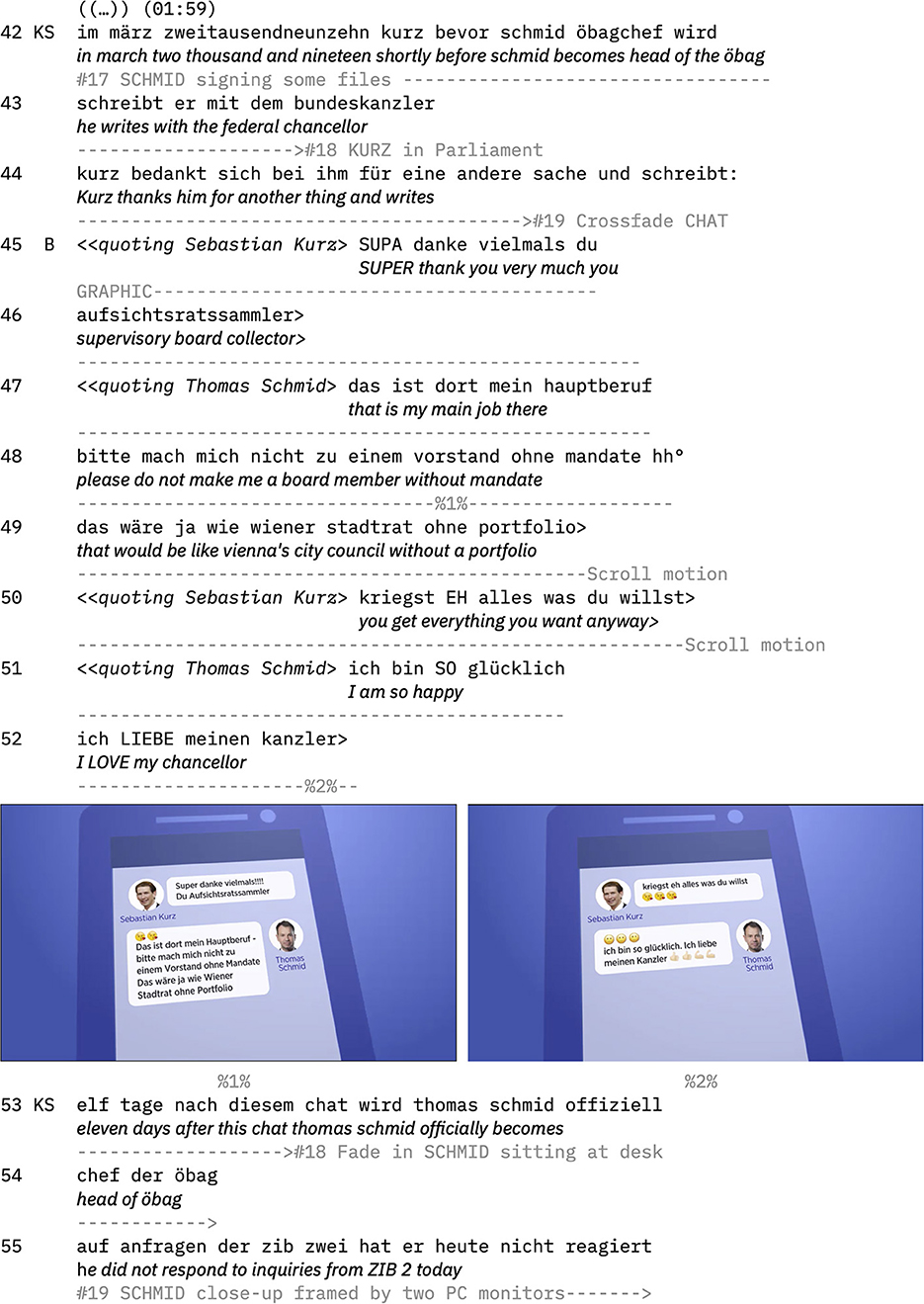

Let's look at an example from the TV news program Zeit im Bild (Figure 4). The entire news report features four chat fragments in the form of multimodal reenactments. I have chosen the end of the segment, in which an IM chat interaction between Thomas Schmid and the then Chancellor Sebastian Kurz is re-enacted. The segment consists of archive images and the chat graphics and the off-camera voices of two ORF journalists who also produced the whole news piece (in the verbal transcript: KS and B).

Figure 4. Transcript of a multimodal reenactment of a IM chat fragment. (ZIB 2 am Sonntag, broadcast on March 28, 2021 at 9:48 p.m.).

KS leads the sequence with contextual information by datelining the sequences and naming the participants (lines 42–43). The quoted chats are extracted from a longer conversation. The journalist only mentions the antecedents (“Kurz thanks him for another thing”) but does not elaborate (line 44). This is followed by the multimodal re-enactment. The segment presents a graphic insert showing a stylized mobile phone screen (line 45–53). This visual restaging is, in the case of this dynamic overlay, however, remodeled multimodally. On the one hand, by a phased fade-in of the chat messages, appearing piece by piece alongside the narration of the chat messages. On the other hand, by B, who voices the chat messages of Kurz and Schmid. In this process, the originally written chat messages are performed verbally and shaped prosodically (e.g., in lines 45, 50, 51). The takeover of chat messages on the screen is quite literal, even emojis are included. Again, there is a considerable transformation of the original materials. However, the temporal dynamics of the rendering does not coincide with the original situation. In the journalistic reenactment, responses have to be instantaneous and synchronous, while in the written chat interaction a typical quasi-synchronous time relationship dominates, frequently with several minutes passing between turns. While such realism would not be suitable for television news, the cross-media recontextualization in this mode exhibits a completely different temporal dynamic and conversational character than the original source material of the IM chats.

In this paper, quotation was considered as a practice of recontextualization, not within individual CMC genres, but rather as a cross-media procedure by which discourse fragments from CMC are repurposed and reworked into other media domains, such as news media. In the face of technological advances, media convergence and “emergent CMC modes,” Herring (2019, p. 47) has proposed a theoretical reconceptualization of CMC that is inherently multimodal, extending the historical research focus on purely text-based CMC modes. Besides the need to conceptualize IM chat discourse on its own as multimodal, multimodality matters especially when it comes to cross-media recontextualization. Analyzing the processes of cross-media transfer-and-transformation exposes textual changes such as simplification or elaboration (Linell, 1998; p. 155), but also shifts in the multimodal configurations of the source materials and the (sometimes newly introduced) multimodality of the recontextualized discourse fragments.

Contrary to previous political scandals in Austria, the corruption affair of the Austrian People's Party (ÖVP), which in time of writing has not yet been definitively resolved, is explicitly about textual evidence. Much like Pollak (2021) observed for the recontextualization of internal documents in the case of the Snowden Leaks, here too evidence is made accessible through entextualization (Bauman and Briggs, 1990). In the present case, it is the leaked files of the prosecution investigation and, more precisely, the forensic transcripts contained therein that make the chat messages “decontextualizable” (Bauman and Briggs, 1990, p. 73), thus producing circulable texts and enabling cross-media quotation in the first place. Entextualized in this way, the private discourse of the politicians of the Austrian People's Party (ÖVP) could be widely quoted, reported on, and publicly scrutinized.

The analysis of journalistic news media revealed three modes of cross-media recontextualization that differ significantly in the way they embrace the mediality of IM chat discourse. The patterns found in the analysis indicate the different ways in which journalists deal with the new challenge of reporting on digital discourse such as chat messages. Arguably, these differences are grounded in conventionalized and emerging quoting practices in media (Haapanen and Perrin, 2017). As might be expected, well-established procedures of recontextualization continue to be used even when dealing with novel sources such as IM chat discourse. In addition to cross-media recontextualization in a purely textual mode, however, there is apparently also a strong incentive to represent the dialogic-sequentially organized chat discourse in a visual and multimodal mode that in some ways mimics mobile messenger communication. Journalistic recontextualization of IM chat discourse anticipates the audience's expected experience with CMC genres. An investigation of the mediation work manifested in the course of cross-media recontextualization can therefore also provide insights into existing conceptions of CMC and inform research that explores media ideologies (Gershon, 2010) by examining the metalanguage we use to talk about technologies and media in everyday life. By indexing and restaging certain aspects of chat mediality, the journalistic representations draw on shared experiences with this form of communication, thus revealing socially shared notions of messenger communication that have solidified as conceptualizations. Further research should not only focus more on the mediality of quotation practices, but also investigate to what extent mediality is co-transmitted or re-enacted in recontextualization practices. This would contribute to a more complete picture of how journalists proceed in taking over media material, which aspects of the mediality of recontextualization are highlighted and for what purpose.

Recontextualization as theoretical lens highlights shifts in meaning. The questions of what is discarded and what is newly added in the process of cross-media transfer-and-transformation are relevant for CMC.

The investigated case is remarkable for Austrian media discourse because here, for the first time, emojis were reproduced on a large scale as utterances of political actors. Emojis are ubiquitous in political discourse, but on the side of citizens. The novelty of the case studied is that the use of emojis by political actors themselves were also in the spotlight. This is linked to a second novelty, namely the need to reflect emojis in political quotations. The analysis showed that only in visual forms of visual staging or multimodal reenactments, emojis also appear as pictorial signs. In journalistic reporting in print media and online media, however, emojis are more strongly commented on meta-linguistically. This also reveals procedures of verbalization of emojis that are also to be expected in other forms of cross-media quotation should also be investigated more closely regarding the broad linguistic research on emojis.

In the process of cross-media recontextualization, the investigated modes of quoting IM chat discourse refocus selected chat messages or sequences and reevaluate the private conversations in the context of corruption investigations. The more closely individual chat sequences are reproduced and visually staged as a whole, the more pronounced the highlighting function becomes. I would like to suggest calling this type of quoting ostentatious quoting. Here, the chats are allowed to speak more strongly for themselves. On the one hand, this allows for less fragmentation and fragmenting compared to forms of textual replay. On the other hand, the (former) private chat conversations are also exposed and showcased to a greater extent. This is particularly noticeable in the elaborately produced form of multimodal reenactment. In this form of cross-media recontextualization, the private conversations are brought onto a public stage and performed anew for everyone.

The multimodality of the recontextualized IM fragments can also related to the implicit claims of authenticity that speakers always make whenever they report the speech of themselves or others. As Jones (2014, p. 204) points out, “intermedial entextualiziation of enquoted utterances inevitably raises questions about the representational adequacy of the target medium.” Bearing this in mind, journalistic efforts to emulate the chats in a fabricated IM design can also be seen as a strategy of controlling and/or manufacturing authenticity.

That in the case of the Corruption Affair of the Austrian People's Party the perceived desire to provide such ostentatious quotations of the IM chat discourse is obvious in light of the prolonged intensity with which this pattern was used. This need is obvious even beyond a purely journalistic reprocessing. Vienna's Burgtheater, for example, staged a reading of the chat discourse in cooperation with the daily newspaper Der Standard on Oct. 16, 2021, in which the messages were recited by actors. Here, the present contextualization is limited to a mere chronological classification. This indicates that the political relevance of the chats was already sufficiently known to the audience and could therefore be taken for granted. The entire event was streamed live on YouTube and published as a video clip (Burgtheater, 2021).

The public interest in such forms of ostentatious recontextualization is therefore evident. For journalistic genres, however, the question is whether such restagings are appropriate or adequate. Given the eminent impact of cross-media recontextualization practices on public discourse, further research effort can and should also embrace a critical perspective, extending multimodal research toward critical discourse analysis (Ledin and Machin, 2019). For practitioners, cross-media quotation presents a new challenge that will continue to be relevant. Media linguistics research can also help further clarify the consequences, effects, and risks of such and other forms of cross-media recontextualization.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

The Open Access publication fee was financed by the publication fund of the Vice Rectorate for Research and the Faculty of Language, Literature and Culture of the University of Innsbruck.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Arendholz, J. (2015). “Quoting in online message boards: an interpersonal perspective,” in The Pragmatics of Quoting Now and Then (Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton), 53–70. doi: 10.1515/9783110427561-004

Bauman, R., and Briggs, C. L. (1990). Poetics and performance as critical perspectives on language and social life. Ann. Rev. Anthropol. 19, 59–88. doi: 10.1146/annurev.an.19.100190.000423

Beißwenger, M., and Lüngen, H. (2020). CMC-core: a schema for the representation of CMC corpora in TEI. Corpus 20, 4553. doi: 10.4000/corpus.4553

Bouvier, G. (2019). How journalists source trending social media feeds. J. Stud. 20, 212–231. doi: 10.1080/1461670X.2017.1365618

Bublitz, W., and Hoffmann, C. R. (2011). ““Three men using our toilet all day without flushing—this may be one of the worst sentences I've ever read”: quoting in CMC,” in Proceedings: Anglistentag 2010 Saarbrücken, eds J. Frenk, and L. Steveker (Trier: WVT), 433–47. Available online at: https://opus.bibliothek.uni-augsburg.de/opus4/frontdoor/index/index/docId/56557 (accessed September 30, 2022).

Burgtheater, W. (2021). Causa Kurz: Die Chatprotokolle|Burgtheater. Causa Kurz: Die Chatprotokolle. Available online at: https://www.burgtheater.at/causa-kurz-die-chatprotokolle (accessed September 30, 2022).

Cowan, K., and Kress, G. (2017). “Documenting and transferring meaning in the multimodal world,” in Remixing Multiliteracies: Theory and Practice from New London to New Times, eds F. Serafini, and E. Gee (New York, NY: Teachers College Press), 50–61.

Eder, M. (2021). Billionaire Peter Thiel Hires Austria's Disgraced Former Chancellor. New York, NY: Bloomberg. Available online at: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-12-30/billionaire-thiel-gives-austria-s-former-wunderkind-a-job (accessed September 30, 2022).

Gershon, I. (2010). Media ideologies: an introduction. J. Ling. Anthropol. 20, 283–293. doi: 10.1111/j.1548-1395.2010.01070.x

Gruber, H. (2017). Quoting and retweeting as communicative practices in computer mediated discourse. Discourse Context Media 20, 1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.dcm.2017.06.005

Haapanen, L. (2017). Monologisation as a quoting practice: obscuring the journalist's involvement in written journalism. J. Pract. 11, 820–839. doi: 10.1080/17512786.2016.1208057

Haapanen, L., and Perrin, D. (2017). “Media and quoting,” in The Routledge Handbook of Language and Media, edited by Colleen Cotter and Daniel Perrin, 1st Edn (London: Routledge), 424–41. doi: 10.4324/9781315673134-31

Herring, S. C. (2019). “The coevolution of computer-mediated communication and computer-mediated discourse analysis,” in Analyzing Digital Discourse, eds P. Bou-Franch, and P. Garcés-Conejos Blitvich (Cham: Springer), 25–67. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-92663-6_2

Johansson, M. (2019). “Digital and written quotations in a news text: the hybrid genre of political opinion review,” in Analyzing Digital Discourse, eds P. Bou-Franch, and P. Garcés-Conejos Blitvich (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 133–162. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-92663-6_5

Jones, G. M. (2014). “Reported speech as an authentication tactic in computer-mediated communication,” in Indexing Authenticity, eds V. Lacoste, J. Leimgruber, and T. Breyer (Berlin: De Gruyter), 188–208.

Karnitschnig, M. (2021). Sebastian Kurz: From Political Wunderkind to Rogue Operator. Arlington County: Politico. Available online at: https://www.politico.eu/article/house-of-sebastian-kurz/ (accessed September 30, 2022).

Klenk, F., and Staudinger, M. (2021). Die Akte Kurz. Vienna: Falter Verlagsgesellschaft. Available online at: https://www.falter.at/zeitung/20210512/die-akte-kurz (accessed September 30, 2022).

Ledin, P., and Machin, D. (2019). Doing critical discourse studies with multimodality: from metafunctions to materiality. Crit. Discourse Stud. 16, 497–513. doi: 10.1080/17405904.2018.1468789

Linell, P. (1998). “Approaching dialogue: talk, interaction and contexts in dialogical perspectives,” in Impact: Studies in Language and Society, Vol. 3 (Amsterdam: Benjamins).

Murphy, F. (2021). Head of Austrian State Holdings Group, Stung by Texts with Kurz, Quits. London: Reuters. Available online at: https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/head-austrian-state-holdings-group-stung-by-texts-with-kurz-quits-2021-06-08/ (accessed September 30, 2022).

Nikbakhsh, M., and Melichar, S. (2021). WKStA führt Bundeskanzler Kurz als Beschuldigten. Vienna: Kurier Zeitungsverlag und Druckerei. Available online at: https://profil.at/oesterreich/wksta-fuehrt-bundeskanzler-kurz-als-beschuldigten/401379449 (accessed September 30, 2022).

ÖBAG (2022). Das Portfolio der ÖBAG. Vienna: OEBAG. Available online at: https://www.oebag.gv.at/organisation/portfolio/ (accessed September 30, 2022).

Pfurtscheller, D. (2022). “Zitieren via screenshot. Digitale Pragmatik und Medialität bildbasierter Zitierpraktiken” in Digitale Pragmatik, eds S. Meier-Vieracker, L. Bülow, R. Mroczynski, and K. Marx (Heidelberg: Metzler), 109–126.

Pollak, C. (2021). Legitimation and textual evidence: how the snowden leaks reshaped the ACLU's online writing about NSA surveillance. Written Commun. 38, 380–416. doi: 10.1177/07410883211007870

zackzack.at (2021). Der Kurz-Akt. London: zackzack.at. Available online at: https://zackzack.at/2021/05/12/der-kurz-akt (accessed September 30, 2022).

Keywords: quotation, recontextualization, news discourse, political communication, media linguistics, multimodality

Citation: Pfurtscheller D (2022) From private phones to public screens: Cross-media recontextualization of chat discourse in the case of the Austrian ÖVP corruption affair. Front. Commun. 7:1059131. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2022.1059131

Received: 30 September 2022; Accepted: 28 November 2022;

Published: 15 December 2022.

Edited by:

Helmut Gruber, University of Vienna, AustriaReviewed by:

Dezheng Feng, Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong SAR, ChinaCopyright © 2022 Pfurtscheller. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Daniel Pfurtscheller, ZGFuaWVsLnBmdXJ0c2NoZWxsZXJAdWliay5hYy5hdA==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.