95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Commun. , 20 September 2022

Sec. Culture and Communication

Volume 7 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2022.1000849

This article is part of the Research Topic Translation and Interpreting as Communication: Issues and Perspectives View all 10 articles

Communication has been conceptualized and studied in a wide range of disciplines. However, very few communication theories or models have explicitly incorporated interpreting as an indispensable process to achieve communicative goals in intercultural and interlinguistic settings where communicative parties do not share a common language. By the same token, despite a strong emphasis of interpreting as “a communicative pas de trois”, there is much remaining to be explored in how existing communication theories and models could be drawn on and adapted to shed light on the key communication issues in interpreting studies. In view of such a distinct gap attributed to a striking lack of attention from both communication and interpreting scholars, as highlighted in this special issue, the author develops a symbolic interactionist model of interpreter-facilitated communication with a focus on exploring how an interpreter's identification with self-meanings and role management, which is key to their intrapersonal covert rehearsal process, impact on their interpreting decisions and behaviors. Through one-to-one interviews with three professional interpreters from the National Register of Public Service Interpreters, it is found that the interpreters' identification with particular self-meanings at the intrapersonal level, which gives rise to identity integration, identity accumulation and disidentification strategies, has impacted on how they managed various challenges at the interpersonal level, such as the impossibility of the neutrality expectation, dealing with inappropriate non-interpreting demands from communicative parties, and resolving identity conflicts linked to communicative contexts.

Communication constitutes one of the most complex, interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary concepts which has been theorized from a vast range of disciplinary perspectives oriented in humanities, social science and natural science, such as literary, linguistic, anthropological, sociological, psychological, neurological, and mathematical, to name but a few (Krauss and Fussell, 1996; Craig, 1999). Amongst numerous existing communication theories and models, very few have explicitly incorporated or considered interpreting as an integral component in their theorizations. By the same token, despite postulations of interpreting as a communicative activity (e.g., Wadensjö, 1998; Mason, 2005; Angelelli, 2012), there is still much work to be done to explore how existing interdisciplinary or multidisciplinary communication theories and models can be drawn on or adapted to expound pertinent communication issues that contribute to expanding and deepening our knowledge of interpreting (e.g., Ingram, 1974/2015, 1978; Wilcox and Shaffer, 2005; Deng, 2018). In view of this distinct gap as highlighted in this special issue, I shall draw on transactional communication model research and the symbolic interactionist approach to communication, in order to develop a symbolic interactionist model of interpreter-facilitated communication which situates interpreting in a larger and more holistic communicative process and, therefore, illuminates some key communication issues in face-to-face interpreting.

Communication constitutes a fluid theoretical construct that connects and flows through diversified disciplines. Encompassing as the term indicates, it runs the risk of “becoming an amorphous catch-all term” that may “mean all things to all men” (Luckmann, 1993, p. 68). Therefore, a meaningful discussion of how it can enrich our knowledge of interpreting requires a clearly defined focus that is conducive to achieving the research aim in this study. The paper will start with a brief review of research conceptualizing the mechanism of a communicative process and highlight that the model theorized in this research bears the fundamental characteristics of the dynamic transactional communication approach. In the respect of the sociological/dialectic relationship between the communicative components, this study will employ the symbolic interactionist perspective of communication which seeks to understand how meanings are co-constructed and emerging from reciprocal interactions between communicative agents in the social environment and how symbols, including language, are used to communicate meanings and to make sense of the world from communicators' own perspectives (Aksan et al., 2009). The proposed symbolic interactionist model of interpreter-facilitated communication conceptualizes interpreting as an integral part of a broader communicative loop where the integrity of the event under study, i.e., the social communication facilitated through interpreting, is preserved by paying attention to a multitude of variables and illustrating their mutual influences upon each other in a holistic, heuristic, and dialectic manner.

Language and communication – human's unique ability “to symbolize with virtually unlimited flexibility” (Bowman and Targowski, 1987) – has been the center of intellectual pursuit since Aristotle's conceptualization of public speaking communication process for more than 2,000 years ago. In recent decades, one of the best-known communication process models constitutes (Shannon, 1949), Mathematical Theory of Communication where communication is depicted as a linear process through which a message is conveyed from a source sender to a destination receiver through (electronic) transmission channels. Shannon (1949) and other linear communication models feature communication as a one-way message transmission and are recognized as inadequate to represent the complex dynamics of human communication. In an effort to account for more relevant interpersonal, social and cultural components of the communication process, subsequent theorists (e.g., Schramm, 1954; Westley and MacLean, 1957), posit interactive models that accentuates communication process as a two-way interaction where receiver actively provides feedback to sender, and both sender and receiver encode and decode messages in the communicative context influenced by interpersonal and sociocultural variables relevant to the communication event.

The dynamic transactional communication type of model, in which this proposed model falls, highlights that both communicative agents actively participate in the communication process without distinguishing sender from receiver as both on the sending and receiving ends of the process. Communication is suggested to involve interactions that occur at two separate levels. One is at an interpersonal level between the communicative agents, and the other is at the intrapersonal psychological level of the individuals and occurs when they interact with their knowledge base. The two types of interactions take place concurrently and seamlessly to divulge shared information, which forms the basis for co-creating meanings. This type of model serves to illustrate the dynamicity, unrepeatability, and continuity of the communicative process of humans where meanings are constantly co-created and shared (Parackal et al., 2021). The process featuring the proposed symbolic interactionist model of interpreter-facilitated communication in this study reflects the two levels of interaction/communication happening inter- and intra-personally, with a focus on exploring how activities of connecting with internal knowledge base at the intrapersonal sociopsychological level impact on interpreter's output behavior managing interactions at the interpersonal level.

Central to the symbolic interactionist approach is the interest in conceptualizing how individuals use language and symbols to create meanings, making sense of their world from their sociopsychological perspective, and to develop social structures through repeated and interactive communication. The dynamic overarching framework constitutes a bottom-up approach where individuals are conceived as agentic and autonomous in developing their self-meanings and, in the meantime, as integral and interdependent in co-creating and co-constructing their social environment through the continuous social process of communicating and interacting with others (Carter and Fuller, 2015). Philosopher, sociologist and sociopsychologist Mead's (1934) thinking provided the major thrust and influence on much current conceptualization of the self, communication and society, giving rise to “the most fully developed and central components of” symbolic interactionism (Burke and Stets, 2009, p. 32). Mead (1934) believes that socialized humans have three key capacities to enable them to carry out complicated internalized analysis before performing a particular communicative act with a view to inducing a desirable outcome. They comprise the capacity to use symbols, including languages, bodily gestures and significant objects, to construct and communicate meanings; the reflexive capacity to act upon the self as an object and the social environment to which the self is oriented, and to develop pertinent self-meanings; and the empathetic capacity to take the role of the other, and thus able to understand the other's attitudes and to evaluate things/situations from the other's perspective. The self also has the ability to decipher the position that one occupies in the social environment in relation to others and develops conscious goals. The self, Mead suggests, adapts to, adjusts and changes their environment and their own behavior through communication with others in order to achieve their own/shared communicative goals.

Following Mead, Hulett (1966, p. 5) further fleshes out the dialectic relationship amongst the self, communication, and society by positing a symbolic interactionist model of human communication with a view to theorizing “the processes and mechanisms of human communication on the social, interpersonal level where they actually operate, and that envisages whole persons as the units1 involved in the process.” Hulett argues that a communication model constructed entirely from the symbolic interactionist viewpoint would offer a distinct advantage of postulating a single but multilevel conceptual scheme “where some communicative events take place within and others take place between the individuals involved,” and thus “could provide the linkages between levels” and of how activities taking place at one level may be influenced by activities at another level (Hulett, 1966, p. 8).

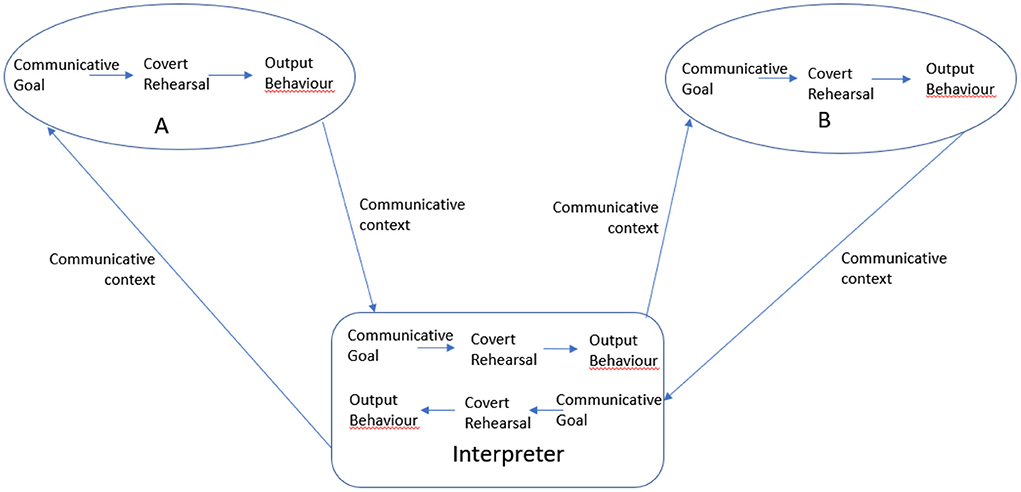

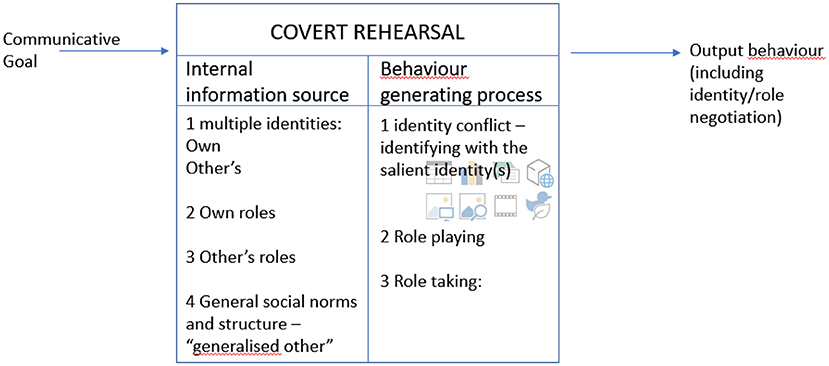

The symbolic interactionist model of interpreter-facilitated communication proposed in this study will draw on the strengths of the intrapersonal and the interpersonal levels of conceptualizations featuring both the dynamic transactional model approach and the symbolic interactionist perspective. It has a distinct interest in how interpreters engage with and draw on their own sociopsychological knowledge base at the intrapersonal level to generate appropriate output behavior by incorporating and probing Hulett's (1966) conceptual notion of covert rehearsal process. It posits a new symbolic interactionist communicative process where interpreting constitutes an integral part of the communicative events. The interpersonal and the intrapersonal levels of the symbolic interactionist model of interpreter-facilitated communication are represented in the Figures 1, 2.

Figure 1. Interpersonal feedback loop of the symbolic interactionist model of interpreter-facilitated communication.

Figure 2. Intrapersonal level of covert rehearsal (revised based on Hulett, 1966).

From a symbolic interactionist point of view, human communication is always initiated in a social situation which informs people of their particular communicative goals. In line with their goal, A generates and transmits a message to encourage B to respond with a cooperative behavior conducive to helping A achieve their goal. The symbolic interactionist model highlights that between the stage of communicative goal and the act of producing an output behavior, there exists an important intrapersonal stage of covert rehearsal (Hulett, 1966) where each communicator, including the interpreter, actively draws on their internal information source to interpret the input pattern of the communicative goal and organizes their forthcoming output behavior. The term “output behavior,” rather than “interpreting,” is adopted to describe the interpreter's act because after connecting with their internal information source, the interpreter may decide against simply interpreting the message as shown in many existing studies (e.g., Angelelli, 2004; Inghilleri, 2012; Yuan, 2022). Therefore, the term “output behavior” is more encompassing in representing the social act that an interpreter may take. In the communication loop, output behavior creates the communicative context that influences the input pattern of the message receiver's communicative goal.

At the intrapersonal level, covert rehearsal is suggested to include “internal information source” that communicators draw on to organize their respective actions and “behavior generating process” where they make decisions on how to develop and perform an output behavior that can effectively solicit desired responses (Hulett, 1966, p. 18). In particular, the internal information source comprises important symbolic interactionist ideas of self-concept/identity, role and social norms and structure, or the “generalized other” in Mead's (1934, p. 144) language. According to the symbolic interactionist framework, a communicator deciphers their place/role in a social structure and develops self-meanings associated with that role. Depending on the relationship they have with others in the social structure, the communicator must understand and incorporate others' expectations of how they should behave when taking that role. Social norms define the nature of a communicative event and limit the repertoire of appropriate behavioral strategies that a communicator can mobilize when taking certain roles. Therefore, during the process of generating output behavior, a communicator will actively access and assess the information source of their own self-meanings and identify with those self-meanings considered to be most salient in the communicative context and take actions to fulfill the role requirement, i.e., role playing. In the meantime, the communicator must be mindful of what relevant self-meanings other may claim or pursue at the communicative event which could influence other's role-playing and role-taking patterns.

The intrapersonal level of the model shows that covert rehearsal constitutes an important step through which all the participating communicators' output behaviors are evaluated and generated. Therefore, notions of identity, role and society are key to understanding an individual's, such as an interpreter's sociopsychological process that has a significant impact on their behavior at the interpersonal level.

How do the notions of identity, role and society impact on people's decision-making and behavior has been the center of symbolic interactionist pursuit. Identity represents a set of self-meanings and values we claim and uphold when assuming a variety of roles associated with the positions we occupy in the social structure. Society is a complex system featuring numerous embedded interwoven networks. A social person often occupies multiple positions in these networks which gives rise to varied self-meanings in relation to the other. For example, a person may have the identity of a parent in relation to their child, may assume the identity of an interpreter in relation to the others in the communicative event who rely on their interpreting, and may also possess the identity of a political party member dedicated to political objectives shared by the other party members.

Burke and Stets (2009) suggest that the types of identity a social person may possess should be taxonomised on three bases: roles, persons and groups. Role identity entails components of the self that correspond to the social roles we play (Grube and Piliavin, 2000). It is developed in response to social expectations of certain behaviors a person should display/perform when taking up a role. For example, “interpreter” constitutes an important role identity when one assumes the role of facilitating interlinguistic, intercultural and/or inter-semiotic communication. During the process of facilitating communication, there are long-established social expectations of how an interpreter should behave which are systematically articulated and regulated in the code of conduct for interpreters; that is, the interpreting ethics.

Social identity refers to the ways that a social person's self-concepts are based on their membership of a social group and together with emotional and valuational significance attached to that group membership (Campbell, 2011). For example, the statement that “I am a qualified interpreter registered with the National Register of Public Service Interpreters (NRPSI)” constitutes a distinct claim of social identity. The statement implies that the interpreter belongs to a recognized and reputed professional group whose membership can only be secured through attaining required qualifications and experiences. It constitutes an in-group membership where members are committed to protecting and promoting group reputation and prestige by providing high standard professional services, distinguishing themselves from non-NRPSI qualified interpreters, and therefore, members develop emotional and valuational significance attached to the group and its status. The in-group claim may demonstrate an intention to highlight the intergroup differences in quality and standard assurance by explicating the person's in-group membership. Social identity constitutes a key concept within which intergroup distinctions and discrimination are studied.

Person identity is based on a view of the self as a unique individual, distinct from other persons by the qualities or characteristics one internalizes as their own, such as priding oneself as a social being with exceptionally high moral standards. Moral identity constitutes an important person identity, and it is considered a source of moral motivation bridging moral reasoning (our evaluative judgments on whether certain behaviors are socially just or unfair) to moral actions. Therefore, it is suggested that people with a stronger sense of moral identity will be more likely to do what they believe is right, and more likely to show enduring moral commitments (Blasi, 2001). Yuan (2022) points out that an interpreter's moral identity and its relationship to role identity constitute two uncharted areas in interpreting research. Yuan (2022) illustrates with examples from a professional interpreter where their moral identity (the self-concepts prompting personal actions that promote social justice) and their role identity (the self-concepts encouraging behaviors in conformity with professional ethics) required different courses of actions. It is found that when facing such intrapersonal identity conflicts, the interpreter has taken actions guided by their salient identity that occupies a higher position in the identity salience hierarchy while doing their best to mitigate threats to self-meanings and values underpinning the other identity.

Drawing from the above, such relevant research questions duly arise: (1) How does an interpreter manage and identify with a multitude of self-meanings vis-à-vis their professional role, which is central to their covert rehearsal? (2) What is the impact on their output behavior? (3) How may an interpreter decide to perform and negotiate their identity/role at the interpersonal level? These are the three questions that this research seeks to address.

To explore this, one-to-one interviews with three professional interpreters, who are members of the National Register of Public Service Interpreters (NRPSI), are conducted to delve into their reflections on how their sense of self and perceptions of other may have impacted on their decisions, attitudes and behaviors during the process of facilitating communication. All the interviewed interpreters possess certified public service interpreting qualifications and have been practicing members at NRPSI for at least 8 years. All the interviews are conducted in English language, and in a private setting that encourages uninterrupted elaborations. All the interviewed interpreters are highly competent in elaborating their ideas in English without any difficulty. The researcher has made conscious efforts not to lead the interpreters' answers. For example, the interpreters were not informed of the research purpose before or during the interview processes. Moreover, open-ended questions are formulated to elicit spontaneous and rich responses. The researcher has also made efforts not to interrupt the interpreters' thought process by giving ample time for reflections and pauses. The open ended questions include: How do you see yourself when helping people to communicate with each other at various settings?; What do you think how others see you at those events and why?; Can you recall some interpreting occasions that have stood out for you and what happened?; What do you think of your decisions made there and then, and why?. Further probing questions are initiated to prompt deeper reflections when an interpreter has completed the account of an incident or it is clear that their thought process has come to an end. Examples of such prompt questions are: How did you feel about it?; Why did you make that decision?; How do you perceive your decision or what you did at the time?; and so on.

All the interviews are transcribed verbatim for analysis. The transcriptions retain all the original verbal features, including fillers, hesitations, repetitions, self-corrections, ellipses and ungrammatical expressions, to reflect the authenticity and the communicative style of the interviews. Ungrammatical expressions in oral communication are common even amongst the native-English speakers. They do not reflect the interviewees' (lack of) linguistic competence in English.

The interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) process is employed as it emphasizes the researcher's role in actively engaging with and interpreting the research subjects' efforts of making sense of their lived experiences, in this study, their interpreting experiences (Smith et al., 2009). This is achieved by the researcher reading through the transcriptions repeatedly, making descriptive, linguistic, and conceptual notes (Yuan, 2022), and extrapolating shared experiential statements among the interpreters. For confidentiality, the interpreters' names are replaced with the following pseudo-names in the analysis: Michael, Sandra, and Kathleen. The University of Birmingham research ethical guidelines are fully abided by where all the interpreters' consents to interview and to be video-recorded for research purposes are obtained beforehand and they have been informed that they have the right to withdraw from the interview whenever they wish to do so.

Existing studies have critically examined the issue of interpreter's neutrality through various social lenses, such as the framework of emotional labor (Ayan, 2020), the stakeholders' expectations in diversified communicative settings (Clifford, 2004), and the narrative concept in situations of conflict (Baker, 2006). This study, for the first time, approaches it from the perspective of interpreter's identification with self-meanings.

The interviewees' comments (see Appendix 1) communicate that it is difficult to identify with the absolute neutrality role and how the role is described in the NRPSI Code of Conduct. They point out that the rules2 around neutrality must be subject to interpretation for them to provide meaningful guidance. Nevertheless, the interpreters are seen to have varied views on how such rules should be interpreted and what constitute appropriate strategies and behavioral choices that are fit and acceptable within the neutrality boundary.

Michael suggests that the “neutrality” expectation of his role identity conflicts with his human identity by commenting that “A person who's neutral is devoid of … a soul.” His identification with the superordinate categories of human qualities (Carmona et al., 2020), which is developed through life experiences and knowledge advancement, gives rise to his beliefs and values that are consistent with the broad characteristics of humanity, and therefore, in his view, prevents him from acting in a neutral and devoid manner. In the meantime, Michael also shows a standpoint that opposes interpreters taking on an advisory role by offering direct advice to the communicative party. This is in line with interpreting ethics and his role identity. Michael's identifications with his human identity and with the non-advisory aspect of his role identity, and his dis-identification from the absolute neutrality expectation may produce emergent internal tensions, ambiguity, and paradox (Knights and Willmott, 1999), and may lead to identity ambivalence – contradictions between one's self-meanings and the expectations that society has of them (Davis, 1994). Identity integration, achieved through devising a meta-identity, is suggested in identity literature as one of the coping strategies to enable individuals to relate and embrace discrete identities as synergistic and interdependent (Gotsi et al., 2010), thus helping to achieve intrapersonal identity harmony. In this case, Michael perceives himself “as a value adder,” a meta-identity that offers a superordinate self-categorization of being a helpful person (his human identity) and being a professional (his role identity) at the same time. In his view, the contradictions between self-meanings and social expectations are reconciled and synergized within this meta-identity. Influenced by the core self-meanings conceptualized in this meta-identity of a value adder, Michael proposes an interpreting strategy of signposting as a solution to maintaining an interpreter's professionalism and managing communicative incidents where one party is given inaccurate information during the communication process. He expresses his belief that the strategy of signposting enables him to “act within the boundaries, and it doesn't compromise the integrity of the setting itself, and the integrity of the people involved in that setting” (Michael's original comments). Michael gives an example of signposting as “saying: ‘have you heard of the Citizens Advice Bureau? So, maybe you know, if you've, if you would like some further advice on certain such point in your situation, your case, maybe you could visit your local CAB.' So in that case, the interpreters just signpost some NGOs, you know, that might be able to provide support” (Michael's original comments).

Echoing Michael's viewpoints, Sandra also expresses in her remarks an attitude at odds with the absolute neutrality expectation of an interpreter's role identity. Sandra is qualified as an interpreter and as a lawyer. Her role identity as a qualified lawyer is seen to have consistently impacted on her decision-making and her output interpreting behavior. As Sandra reports, she often observes in the magistrate and the crown courts where some legal clerks, who do not possess appropriate legal qualifications, claim the identity of qualified lawyers, and perform in front of the other party such a self-proclaimed role identity by introducing themselves as “I'm your lawyer.” This, as reported, causes a communicative dilemma for Sandra. As a lawyer herself, Sandra is acutely aware of the professional differences between a legal clerk and a qualified lawyer. She is in a position to recognize the false claim and the inappropriate performance of such a role identity by one of the communicative parties, i.e., the legal clerk, to the disadvantage and ignorance of the other party, e.g., an asylum seeker. Her comments reflect her belief that had the absolute neutrality rule been followed in interpreting faithfully such a false claimed identity, she would have been “involved in some kind of deception.”

Moreover, the identity of a qualified lawyer in this case constitutes not only a role identity that enables Sandra's informed insights into the untruthful identity claim, but also a social identity that has contributed to establishing her positive ingroup distinctiveness against outgroup discrimination, as shown in her description of the legal clerks as “they don't have any legal qualifications, or not to my knowledge … these so-called lawyers aren't in fact qualified lawyers.” The outgroup pronoun “they” and the pejorative adjective “so-called” communicate Sandra' salient attitude of distancing herself from and disapproving of the legal clerk's untruthful identity performance.

Sandra has expressed at the interview positive self-perceptions on possessing the social and role identity of a qualified lawyer in addition to her role identity as a qualified interpreter by commenting: “I'm definitely different to many colleagues … because I do have legal qualifications … it's definitely an advantage, in my opinion, to have legal qualifications.” Hennekam (2017) finds that individuals, when managing multiple identities at play, may develop an identity accumulation strategy where the transferability of the skills attained in different types of activities is stressed as a strength and enrichment, equipping them with more creative solutions to personal or communicative problems. Such an identity accumulation strategy, combined with the intergroup prejudice analyzed as above, may have prompted her decision to initiate identity negotiation by indirectly challenging the legal clerk's untruthful identity claim. By using a broader category of “legal representative” and by informing, in an on-record manner, the legal clerk of such a change of identity category, Sandra performs a discursive identity negotiation in the interpreting to redress the identity discrepancy at the interpreter-facilitated communicative event.

Kathleen offers an example where she believes cultural references must be incorporated in the interpreting which in her view “are essential for the communication process.” She illustrates through this example the difficulties of identifying with the absolute neutrality expectation of her role identity, and the confusion such an expectation leads to: “Do I add it? Don't I add it?” Kathleen draws on her own life experiences, when she was living in her home country, to inform the psychiatric nurse of the possible cultural information that may have influenced the patient's behavior during the medical assessment. Her decision and behavior of providing such an input in a proactive way, instead of upon request, demonstrate her move to dis-identify with the expectation of absolute neutrality, and her possible perceptions of self as a cultural enabler, similar to Michael's view of self as a value-adder.

Disidentification conceptualizes how one situates themselves within and against the discourses we are called to identify with (Muñoz, 1999). In the context of interpreting, disidentification entails the rejection of hegemonic role interpellations and the effort to enlarge the autonomous spaces for self-identification. It is adopted by the interviewed interpreters to tackle and challenge unrealistic role expectations and to call for more dynamic role definitions for public service settings that incorporate/take into account and respect qualified interpreters' self-meanings subsumed under their human identity and their professional judgements. Through disidentification, identity integration (devising a meta-identity), and identity accumulation, the interpreters are seen to develop communicative strategies which are guided by their identification with the self-meanings that are conceived as pertinent and salient to the communicative settings.

Sociopsychologists (Burke and Stets, 2009; Swann, 2012) assert that, in social interactions, people take active actions in the pursuit of maintaining a valued and coherent self and ensuring that the upheld self-meanings would be recognized and accepted by communicative partners. Identity-confirming evaluations offer coherence between self-meanings and others' views, while the opposite instigates incongruence and arouses conscious efforts to redress the discrepancy. Burke and Stets (2009) define the process as identity verification where a communicator develops evaluations of the consistency between the self-claimed identity and the other-perceived identity, and takes active steps to eliminate any disturbance that contributes to the discrepancy. Sandra, Kathleen, and Michael report incidents where communicative parties' behaviors threatened the interpreters' role identity, and the interpreters took actions to verify and uphold their role identities.

Sandra offered examples where immigration interviewers sought direct advice from her by asking “Miss XXX, what do you think about such and such?”. The question constitutes an invitation for advice and Sandra's response communicates her salient view of such invitation as a disturbance to her role identity in the communicative event. Sandra is seen to reject the advisor identity imposed on her by highlighting the remit of her role identity as a professional interpreter: “I am not allowed to give an opinion… I'm not allowed to give you that, sort of, you know, answer”. By the same token, Kathleen's experience shows a similar inappropriate appropriation of the interpreter's role identity. As she reports, her institutional client has developed an expectation of her taking on the role identity of an interviewer for the police owing to her repeated experience with them. Kathleen's actions demonstrate her perception of such a behavior as a threat to her role identity as a professional interpreter. She makes remarks about using interpreting ethics as a weapon to fend off the imposed non-interpreter role identity in that context, which in her views, not only helps to verify her role identity as a professional interpreter but also avoids damaging her relationship with the institutional client. Michael makes comments on how he consciously shifts and adjusts his spatial positions in relation to his communicative parties as a strategy of discouraging any potential disturbance or threat to his role identity as a professional interpreter. These examples reflect that at interpreter-facilitated events, communicative parties may develop inappropriate expectations or demands of how the interpreters should do their work, either due to their lack of understanding of an interpreter's role identity or their possible perceptions of interpreters as exploitable resources. Such inappropriate expectations or demands from the communicative parties lead to disturbances or threats to an interpreter's role identity. The interviewed interpreters are seen to take actions to verify their role identities as professional interpreters and to reject imposed non-interpreter role identities by highlighting their role remit (I am not allowed to …), using interpreting code of conduct as a weapon, or changing physical positions to set boundaries at the communicative event.

Identity represents the fundamental sets of values that define who we are, and it is emotionally invested. If verification of one type of identity requires involvement in situations or events that threaten the person's upheld values or beliefs underpinning another identity, intrapersonal identity conflict ensues. A person may feel they must give precedent to one set of self-meanings and values over another (Caza et al., 2018). Identity conflict can be particularly problematic when a considerably high degree of dissonance is experienced and one feels they cannot satisfy role requirements of each identity (Karelaia and Guillen, 2014; Rabinovic and Morton, 2016). Under such circumstances, they are likely to take decisive actions to voluntarily disassociate themselves from the identity to which they are less committed, with a view to eliminating the incompatibilities among the meanings and values.

At the interview, Sandra and Kathleen gave examples where interpreters choose not to take on certain interpreting assignments because verification of the role identity as a professional interpreter in those contexts requires participation in activities that directly oppose to or threaten their social identities underpinned by salient religious beliefs or parental attachment. Activation of these two distinct social identities is foreseen as incompatible and conflicting, by some interpreters, with their role identity. Therefore, those interpreters are observed to actively disassociate themselves from their role identity owing to stronger commitment to the social identities. Michael, on the other hand, provides an example where an interpreting client – a psychiatric hospital – presents persistent challenges for him to properly verify his role identity because the hospital never gives any briefing prior to interpreter-facilitated events where communication often involves potentially violent patients suffering from psychiatric disorders. Michael clearly sees this as a threat to his role identity verification and has made a conscious decision of severing his working relationship with that client to eliminate the threat. Michael highlights throughout the interview that it is of great importance that public service interpreters should be briefed prior to interpreting assignments, but this seldom happens in reality.

In this paper, a symbolic interactionist model of interpreter-facilitated communication is proposed to address the lack of attention to interpreting mediation in the existing communication models. With a view to probing how an interpreter's covert rehearsal components at the intrapersonal level impact on their output interpreting behavior at the interpersonal level, the researcher explores with three professional interpreters, who are active members of the National Register of Public Service Interpreters (NRPSI), how their self-meanings, their perceptions of other's expectations, and their evaluations of other's behavior as well as the communicative context have impacted on how they carry out the interpreting tasks. It is found that all the interviewed interpreters do not identify with the absolute neutrality role stipulated in the NRPSI code of conduct, due to the perceived conflict with the interpreter's human identity, the consequence of rendering the interpreter to be involved in deception, and the confusion preventing the interpreter to represent the essential cultural elements key to the communication process. It is shown at the interview that identity integration (devising a meta-identity), identity accumulation and disidentification strategies have been developed to enable the interpreters to tackle the problems and infeasibility arising from the absolute neutrality expectation. The interpreters also report that at interpreter-facilitated events, they have to take actions to address communicating parties' inappropriate expectations and demands, in order to protect and verify their role identity as professional interpreters. To achieve this, rejecting imposed non-interpreter role identities, either directly or indirectly using code of conduct as a shield, or changing spatial positions to set boundaries has been adopted to verify their role identities as professional interpreters. Last but not least, it is demonstrated that when intrapersonal identity conflicts arise in situations where activation and verification of a professional interpreter's role identity pose a great threat to their committed social identities underpinned by religious beliefs or parental attachment, interpreters are seen to actively disassociate themselves from such communicative contexts which trigger activation of their role identity.

This research constitutes the first effort to examine an interpreter's sociopsychological process at the intrapersonal level and its impact on their interpreting behavior at the interpersonal level, situated within a symbolic interactionist communication model. In future studies, key issues around communicating parties' covert rehearsal processes, the impact on interpreter's output behavior, and how identity is discursively performed, negotiated, and represented at interpreter-facilitated events should be investigated to provide illuminating answers enriching our understanding of interpreting as socially shaped and socio-psychologically engaged communicative activities.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by University of Birmingham Ethics Review Manager. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2022.1000849/full#supplementary-material

1. ^Emphasis in italics added by the author.

2. ^5.4 Practitioners shall interpret truly and faithfully what is uttered, without adding, omitting or changing anything; in exceptional circumstances a summary may be given if requested.

5.9 Practitioners carrying out work as Public Service Interpreters, or in other contexts where the requirement for neutrality between parties is absolute, shall not enter into discussion, give advice or express opinions or reactions to any of the parties that exceed their duties as interpreters; Practitioners working in other contexts may provide additional information or explanation when requested, and with the agreement of all parties, provided that such additional information or explanation does not contravene the principles expressed in 5.4. (National Register of Public Service Interpreters Code of Conducts accessible via https://www.nrpsi.org.uk/for-clients-of-interpreters/code-of-professional-conduct.html).

Aksan, N., Kisac, B., Aydin, M., and Demirbuken, S. (2009). Symbolic interaction theory. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 1, 902–904. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2009.01.160

Angelelli, C. V. (2004). Medical Interpreting and Cross-Cultural Communication. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511486616

Angelelli, C. V. (2012). The sociological turn in translation and interpreting studies. Transl. Interpreting Stud. 7, 125–128. doi: 10.1075/tis.7.2.09con

Ayan, I. (2020). Re-thinking neutrality through emotional labour: the (in)visible work of conference interpreters. TTR Traduct. Terminol. Redaction. 33, 125–146. doi: 10.7202/1077714ar

Baker, M. (2006). Translation and Conflict: A narrative Account. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203099919

Blasi, A. (2001). “Moral motivation and society: Internalization and the development of the self,” in Moral und Rechtim Diskurs der Moderne. Zur Legitimation Geselleschaftlicher Ordnung, eds G. Dux, and F. Welz (Opladen: Leske and Budrich), 313–329. doi: 10.1007/978-3-663-10841-2_14

Bowman, J., and Targowski, A. (1987). Modelling the communication process: the map is not the territory. J. Bus. Commun. 24, 21–34. doi: 10.1177/002194368702400402

Burke, P. J., and Stets, J. E. (2009). Identity Theory. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195388275.001.0001

Campbell, L. (2011). More similarities than differences in contemporary theories of social development?: a plea for theory bridging. Adv. Child Dev. Behav. 40, 337–378. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-386491-8.00009-8

Carmona, M., Sindic, D., Guerra, R., and Hofhuis, J. (2020). Human and global identities: different prototypical meanings of all-inclusive identities. Polit. Psychol. 41, 961–978. doi: 10.1111/pops.12659

Carter, M. J., and Fuller, C. (2015). Symbolic interactionism'. Available online at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/303056565_Symbolic_Interactionism (accessed: April 25, 2022). doi: 10.1177/205684601561

Caza, B. B., Moss, S., and Vough, H. (2018). From synchronizing to harmonizing: the process of authenticating multiple work identities. Admin. Sci. Q. 63, 703–705. doi: 10.1177/0001839217733972

Clifford, A. (2004). Is fidelity ethical? The social role of the healthcare interpreter. TTR Traduct. Terminol Redaction 17, 89–114. doi: 10.7202/013273ar

Craig, R. T. (1999). Communication theory as a field. Commun Theory 9, 119–161. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2885.1999.tb00355.x

Deng, W. (2018). The neutral role of interpreters under the cognitive model of interpreting. Adv. Soc. Sci. Educ. Humanit. Res. 204, 375–378. doi: 10.2991/essaeme-18.2018.69

Gotsi, M., Andriopoulos, C., Lewis, M., and Ingram, A. (2010). Managing creatives: paradoxical approaches to identity regulation. Hum. Relat. 63, 781–805. doi: 10.1177/0018726709342929

Grube, J. A., and Piliavin, J. A. (2000). Role identity, organizational experiences, and volunteer performance. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 26, 1108–1119. doi: 10.1177/01461672002611007

Hennekam, S. (2017). Dealing with multiple incompatible work-related identities: the case of artists. Pers. Rev. 46, 970–987. doi: 10.1108/PR-02-2016-0025

Hulett, J. E. (1966). A symbolic interactionist model of human communication: part one: the general model of social behavior; the message-generating process. AV Commun. Rev. 14, 5–33. doi: 10.1007/BF02768507

Inghilleri, M. (2012). Interpreting Justice: Language, Ethics and Politics. London & New York: Routledge.

Ingram, R. (1974/2015). “A communication model of the interpreting process,” in The Sign Language Interpreting Studies Reader, eds C. Roy, and J. Napier (Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing), 22–28.

Ingram, R. (1978). “Sign language interpretation and general theories on language, interpretation and communication,” in Language Interpretation and Communication, eds D. Gerver, and H. W. Sinaiko (New York, NY: Plenum Press), 109–118. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-9077-4_11

Karelaia, N., and Guillen, L. (2014). Me, a woman and a leader: positive social identity and identity conflict. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 125, 204–219. doi: 10.1016/j.obhdp.2014.08.002

Knights, D., and Willmott, H. (1999). Management Lives: Power and Identity in Work Organizations. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. doi: 10.4135/9781446222072

Krauss, R. M., and Fussell, S. R. (1996). “Social psychological models of interpersonal communication,” in Social Psychology: Handbook of Basic Principles, eds E. E. Higgings, and A. Kruglanski (New York, NY: Guilford Press), 655–701.

Luckmann, T. (1993). “On the communicative adjustment of perspectives, dialogue, and communicative genres,” in Language, Thought, and Communication: A Volume Honoring Ragnar Rommetveit, ed A. H. Wold (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 25–61.

Mason, I. (2005). “Projected and perceived identities in dialogue interpreting,” in Translation and the Construction of Identity, eds J. House, M. Rosario, M. Ruano, and N. Baumgarten (Seoul: IATIS), 30–52.

Muñoz, J. E. (1999). Disidentifications: Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Parackal, M., Parackal, S., Mather, D., and Eusebius, S. (2021). Dynamic transactional model: a framework for communicating public health messages via social media. Perspect. Public Health. 141, 279–286. doi: 10.1177/1757913920935910

Rabinovic, A., and Morton, T. A. (2016). Coping with identity conflict: perceptions of self as flexible versus fixed moderate the effect of identity conflict on well-being. Self Identity 15, 224–244. doi: 10.1080/15298868.2015.1117524

Schramm, W. (1954). The Process and Effects of Mass Communication. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Shannon, C. E. (1949). The Mathematical Theory of Communication. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Smith, J. A., Flower, P., and Larkin, M. (2009). Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis: Theory, Method and Research. London: Sage

Swann, W. B. Jr. (2012). “Self-verification theory,” in Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology, eds P. A. M. A. Van Lange, W. Kruglanski, and E. T. Higgins (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications), 23–42. doi: 10.4135/9781446249222.n27

Westley, B. H., and MacLean, M. S. (1957). A conceptual model for communications research. Journal. Q. 34, 31–38. doi: 10.1177/107769905703400103

Wilcox, S., and Shaffer, B. (2005). “Towards a cognitive model of interpreting,” in Topics in Signed Language Interpreting, ed T. Janzen, 1st ed. (Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing), 27–50. doi: 10.1075/btl.63.06wil

Keywords: symbolic interactionist perspective to communication, interpreter-facilitated communication, identity, role, covert rehearsal

Citation: Yuan X (2022) A symbolic interactionist model of interpreter-facilitated communication—Key communication issues in face-to-face interpreting. Front. Commun. 7:1000849. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2022.1000849

Received: 22 July 2022; Accepted: 29 August 2022;

Published: 20 September 2022.

Edited by:

Binhua Wang, University of Leeds, United KingdomReviewed by:

Haiming XU, Shanghai International Studies University, ChinaCopyright © 2022 Yuan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xiaohui Yuan, eC55dWFuQGJoYW0uYWMudWs=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.