94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Commun., 10 January 2022

Sec. Media Governance and the Public Sphere

Volume 6 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2021.817285

Political campaign communication has become increasingly hybrid and the ability to create synergies between older and newer media is now a prerequisite for running a successful campaign. Nevertheless, beyond establishing that parties and individual politicians use social media to gain visibility in traditional media, not much is known about how political actors use the hybrid media system in their campaign communication. At the same time, the personalization of politics, shown to have increased in the media coverage of politics, has gained little attention in the context of today’s hybrid media environment. In this research we analyze one aspect of hybrid media campaign communication, political actors’ use of traditional media in their social media campaign communication. Through a quantitative content analysis of the Facebook, Twitter and Instagram posts of Finnish parties and their leaders published during the 2019 Finnish parliamentary elections, we find that much of this hybridized campaign communication was personalized. In addition, we show that parties and their leaders used traditional media for multiple purposes, the most common of which was gaining positive visibility, pointing to strategic considerations. The results have implications for both the scholarship on hybrid media systems and personalization of politics.

The use of social media has become an everyday activity in political campaign communication (Enli, 2017), allowing political actors to bypass traditional media and connect directly with the public (Larsson and Kalsnes, 2014). Parties and candidates regularly use social media platforms to inform voters about their strengths and policies and to encourage people to vote, donate, and volunteer for the campaign (Hixson, 2018). As social media are, by definition, personalized media (Metz et al., 2020), they also enable relationships between individual candidates and the public (Small, 2017). This has been argued to increase the personalization of politics (e.g., Enli and Skogerbø, 2013), a process where individual politicians, their personal lives, and personal characteristics become more important at the expense of parties and issues (Van Aelst et al., 2012).

According to Chadwick (2013), however, what is interesting is not the use of social media itself but how it acts as a part of the hybrid media system. In this system, the boundaries between older and newer media become porous, with actors “creating, tapping and steering information flows” across and between older and newer media to suit their goals (Chadwick et al., 2016, p. 4). In political campaign communication, this manifests in the way that political actors use social media not only to bypass traditional media but also to benefit from it, with all traditional campaign events—such as televised debates, news media, and press conferences—now “documented, debated and mentioned” on social media (Enli, 2017, p. 51). According to Karlsen et al. (2016), campaigns can only succeed if they manage to create synergies between social and traditional media.

Enli and Moe (2013) and Jungherr (2016) have called for more research on the intermedia activities of political campaigns. So far, much of this research has focused on analyzing traditional media and whether political actors’ social media use leads to visibility in traditional media (e.g., Wells et al., 2016; Francia, 2018; Kruikemeier et al., 2018). The other half of the equation—or how traditional media influences political actors’ communication in social media—has been largely ignored by scholars. The synergies between traditional and social media are acknowledged by most scholars, with Chadwick et al. (2016) noting that a large portion of the campaign content discussed online is hybrid, first appearing in television or newspapers before traveling to social media. Nevertheless, exactly how this happens and for what purposes have so far gained little scholarly attention. Equally little is known about how the personalization trend has been influenced by the emergence of the hybrid media system, as personalization is still mostly analyzed in the separate contexts of traditional media or (to a lesser extent) social media (Otto et al., 2018).

In our research, we contribute to this gap in research. In an analysis of the hybrid media campaign communication of the 2019 Finnish parliamentary elections, we ask: how and to what extent did parties and their leaders use traditional media in their social media campaign communication? Through a quantitative analysis of the types, functions, and levels of personalization of traditional media shared, we examine whether political actors’ traditional media sharing appears to be strategic and what purposes this behavior has. We extend the existing literature on hybrid media systems by broadening the understanding of how hybrid media campaign communication can benefit political actors. Finally, we examine the implications of the hybrid media system for personalization of politics.

There are two reasons why undertaking such an analysis is justifiable. First, analyzing the mechanisms of how content travels on social media is required to understand how news affects the knowledge, attitudes, and behavior of the public (Chadwick et al., 2018). This is essential in the case of political actors who use traditional media content as campaign material in social media. This content is then often circulated further by the supporters of the party or the candidate, increasing its visibility and lifespan (Harder et al., 2016). As the number of people using social media to find and consume news increases (Newman et al., 2016), so does the likelihood that the news they encounter is no longer objective but interpreted to them through the political actors’ agenda. Second, not all news sharing is conducive to democracy, as evidenced by the rise of misinformation, disinformation, and fake news (Chadwick et al., 2018). For this reason, it is necessary to understand what kind of traditional media content is shared by political actors and which objectives are fulfilled with this type of hybrid media campaign communication.

The research is set in the context of Finland, a parliamentary democracy with high media consumption (Strandberg and Carlson, 2021) and social media use in elections by both candidates and the public (Strandberg and Borg, 2020), making it an ideal case for our study.

The rise of digital media has led to a process of change in which media systems around the world have become increasingly hybrid (Chadwick, 2013). Chadwick (2013) characterized the hybrid media system as “built upon interactions among older and newer media logics—where logics are defined as technologies, genres, norms, behaviors and organizational forms—in the reflexively connected fields of media and politics” (p. 4). In the hybrid media system, different forms of media not only compete for audiences but also complement, benefit, and learn from one another. The emergence of the hybrid media system is visible in the different ways of producing, distributing, and using news (Klinger and Svensson, 2015) and in intermedia agenda setting, characterized as instances when the media agenda is shaped by other media (Sweetser et al., 2008).

In political campaign communication, hybridity manifests in political actors that operate in hybrid media landscapes, using traditional media and social media interchangeably for campaign purposes (Skogerbø and Krumsvik, 2015). The hybrid media system can shape electoral outcomes by benefitting parties and candidates who know how to master the system’s modalities (Chadwick et al., 2016). For instance, both Barack Obama’s 2008 victory and Donald Trump’s 2016 victory in the United States presidential elections have been attributed to their successful use of the hybrid media system (Chadwick, 2013; Francia, 2018).

One of the key aspects of the hybrid media system is the concept of power (Chadwick, 2013). Therefore, it is not surprising that much of the research on hybrid media campaign communication has focused on the power relations between traditional media and social media. Some examples are analyses of the agenda-setting power of social media in relation to traditional media (Conway-Silva et al., 2018; Seethaler and Melischek, 2019) or the ability of traditionally powerful or non-powerful political actors in using social media for gaining visibility in traditional media (Skogerbø and Krumsvik, 2015; Wells et al., 2016; Kruikemeier et al., 2018). Additionally, scholars have analyzed the dual screening of political content, such as televised campaign debates (e.g., Hawthorne et al., 2013; Vaccari et al., 2015).

In hybrid media campaign communication, social media can function as a tool for gaining visibility in traditional media and influencing the traditional media agenda or for bypassing traditional media. What has largely been left unconsidered is the third role of social media—namely, how social media can be used in sharing traditional media content online and contributing to the content’s visibility (Singer, 2014). This is routinely done by journalists and other media actors who share links to their news stories on social media in the hopes of attracting more audience for their content (Ju et al., 2014). However, political actors can also engage in sharing traditional media content on their social media accounts (Skogerbø and Krumsvik, 2015) by, for instance, announcing upcoming media appearances (Hixson, 2018) or sharing links to mass media content, such as online newspapers (Baxter and Marcella, 2012; Klinger, 2013).

This type of hybrid media sharing can be beneficial for political actors for multiple reasons. First, circulating traditional media content on multiple platforms extends its lifespan and visibility (Harder et al., 2016). By sharing positive content on social media, political actors can ensure that it is seen by as many people as possible. Second, while sharing traditional media content on social media, political actors can also comment on the content and give their own ideological slant, thus influencing how audiences perceive said content. This becomes visible during, for example, televised debates, when “party soldiers” mobilize to write on social media to support their candidates and denounce opponents (Jensen and Schwartz, 2020). Third, information originating from traditional media sources is typically perceived as more reliable than information originating from social media (Johnson and Kaye, 2014); thus, sharing this content can act as a form of rhetorical support and strengthen the social media message (Skogerbø and Krumsvik, 2015).

Although the fact that political actors engage in sharing traditional media content on social media has been acknowledged by scholars (Chadwick et al., 2016), few studies so far have attempted to quantify this sharing behavior. These include Klinger. (2013) study on the 2011 Swiss elections, in which she noted that 13% of parties’ Facebook and Twitter posts contained mass media references, and Hixson. (2018) analysis of the tweet functions of the 2016 United States presidential elections, in which tweets on upcoming media appearances were a clear minority. Skogerbø and Krumsvik (2015) studied the intermedia agenda setting between newspapers, Facebook, and Twitter during the 2011 Norwegian local elections, finding that 21% of candidates’ social media posts contained links to local or national media. However, this analysis only calculated references to newspaper media, and not all media. Therefore, more information is needed on this aspect of hybrid media campaign communication. For this reason, our first research question is as follows:

RQ1. To what extent did parties and their leaders use traditional media in their social media posts during the 2011 Finnish parliamentary elections?

The use of social media has been argued to increase the personalization of politics (e.g., Enli and Skogerbø, 2013), a key concept of mediated political communication. Personalization describes a process of change in which 1) individual politicians become more visible in mediated political communication and 2) there is increased interest in the personal characteristics and lives of leading politicians in particular (Van Aelst et al., 2012). For Adam and Maier (2010), personalization constitutes a process in which individual politicians become the “main anchor of interpretations and evaluations in the political process” (p. 213).

Previous research and literature reviews have shown that media reporting of politics has become more personalized over time (Karvonen, 2009; Adam and Maier, 2010). However, this applies only to traditional media, as the personalization of political communication in the context of social media has not been systematically studied so far (Rahat and Kenig, 2018), although individual studies have shown that politicians’ social media posts also contain personalized elements (e.g., Kruikemeier et al., 2013; Small, 2017; Bronstein et al., 2018; Rahat and Kenig, 2018; Otto et al., 2018). There is a lack of research analyzing personalization in the context of hybrid media systems.

It is likely that personalization is also a feature of hybrid media campaign communication. What is not known is whether personalization occurring on social media is, first and foremost, a feature of social media, hybrid media, or both. Traditional media has an inherent tendency for personalized reporting (Langer, 2007), and televised events, such as election debates, emphasize individuals by default (Hayes, 2009). This means that political actors wishing to share traditional media content online are likely to come across a large portion of content that is already personalized, increasing the likelihood of personalized hybrid media content. On the other hand, the so-called social media logic also heavily emphasizes the private and the personal (Enli and Skogerbø, 2013), rewarding politicians for sharing personal content (Metz et al., 2020). Investigating the matter extends our understanding of both the hybrid media system and the personalization of politics. Therefore, we ask:

RQ2. To what extent was the traditional media content about parties and their leaders shared on social media personalized, and how did it compare to social media posts that did not contain traditional media?

New technological developments, such as digital newspapers, television, and radio programs, allow political actors to share a wide range of content with a few clicks. However, not much is known about the types of traditional media content political actors prefer to use in their social media campaign communication. In the age of fake news, understanding political actors’ use of traditional media becomes increasingly important, as it can have implications on democracy. For instance, Chadwick et al. (2018) established a link between sharing tabloid news and democratically dysfunctional misinformation and disinformation behaviors on Twitter. Although this study looked at the behavior of the public instead of political actors, there is no reason to think that political actors would be exempt from this kind of behavior.

Despite the importance of the topic, a limited number of studies have analyzed the types of traditional media shared by political actors. In their study, Skogerbø and Krumsvik (2015) revealed that candidates in the 2011 Norwegian local elections were more likely to redistribute content from local than from national media, showing that local considerations were emphasized. It is also likely that television is favored by political actors, with Chadwick et al. (2016) arguing that the majority of important campaign events first take place on television before being distributed to online media. This is likely the case, especially with Twitter, where political discussions have been shown to spike during media events, such as televised election debates (Larsson and Moe, 2012). In addition, the Twitter-specific practice of dual-screening televised debates (Hawthorne et al., 2013; Vaccari et al., 2015) may increase shares of televised content on Twitter. However, it is not known whether this applies to other platforms as well. Therefore, our third research question is as follows:

RQ3. What types of traditional media content did parties and their leaders use in their social media campaign communication?

At its core, political campaign communication is functional in its nature (Benoit, 2007), with most election campaigns aiming at, if not winning the election, then at least maximizing the share of votes (Strömbäck and Kiousis, 2014). This means that all the resources of a campaign should be dedicated to communicating with and persuading voters (Hixson, 2018). Therefore, it is also likely that political actors’ use of the hybrid media system also has specific functions aimed at persuading voters and gaining votes.

The idea of functionality is perceived differently by different scholars. According to Benoit. (2007) functional theory of political campaign discourse, the communicative functions of a campaign are limited to establishing preferability compared to other candidates and include three options: a candidate can display their own strengths, attack the weaknesses of the opponent(s), or defend themselves against attacks from the opponent(s). These functions can occur at either the policy or character level. On the other hand, Hixson (2018) identified a total of 18 tweet functions in his analysis of the 2016 United States presidential elections. However, some of these functions were directed at ensuring the success of a campaign—for example, asking people to donate money or volunteer—rather than aiming to establish the preferability of the candidate. This suggests that compared to more structured forms of campaigning, such as televised debates or television spots, social media campaign communication can have multiple functions. Therefore, it is likely that hybrid media campaign communication would be a combination of both types of functions.

There is little research on hybrid media campaign communication from the perspective of functional theory. Nevertheless, adopting this perspective is useful, as it allows us to examine how political actors perceive the benefits of using traditional media in their social media campaign communication. For this reason, our fourth and final research question is as follows:

RQ4. What were the functions of the traditional media content shared by parties and their leaders in their social media campaign communication?

In this paper, we use the dichotomous terms “social media” and “traditional media.” Nevertheless, our focus is not on emphasizing their differences but on analyzing how one is intertwined with the other in the political campaign communication of Finnish parties and their leaders as part of the hybrid media system.

The research data were collected during the active campaign period of the 2019 Finnish parliamentary elections (a month-long period before election day, from March 14 to April 14, 2019) from the public social media accounts of the nine parties and their leaders who had formed the parliament in the 2015–2019 term (listed below in Table 1).

Previous research on political communication in social media has largely consisted of single-platform studies, which makes it difficult to draw any conclusions about the use of social media in general (Nelimarkka et al., 2020). For this reason, our research data were gathered from three platforms: Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. These were the three most used platforms by candidates in the 2019 Finnish parliamentary elections (Strandberg and Borg, 2020). In these elections, all nine parties had Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram accounts, and all nine leaders had a Twitter account. All but one leader had a public Facebook page, and seven of the nine leaders had a public Instagram account.

The social media data were extracted using different tools: the Facebook data for party leaders were gathered using Facepager (Jünger and Keyling, 2019) and that for parties using NodeXL (Smith et al., 2010). Instagram data were collected manually using screenshots. For Twitter, a custom script was developed to access tweets from the Twitter API. The research data included all public posts made by parties and their leaders during the month-long period. In the case of Twitter, retweets and replies were also included in the data, in addition to the original posts. With Facebook and Instagram, the research data included only original posts. External URLs were also included, while private messages or posts were not collected.

The research data consisted of 4,063 social media posts by parties and 1,471 social media posts by party leaders. At the time of the analysis, some of the posts were no longer available or contained broken hyperlinks; these were excluded from the data. These figures were small: 73 posts by parties (1.80% of all posts) and 63 posts by party leaders (4.28% of all posts). The final dataset consisted of 3,990 posts by parties (2,557 Twitter posts, 1,139 Facebook posts, and 294 Instagram posts) and 1,408 posts by party leaders (878 Twitter posts, 393 Facebook posts, and 137 Instagram posts).

The data were analyzed using quantitative content analysis, which is especially suitable for the analysis of different political messages (Benoit, 2011). We adopted a single social media post as the unit of analysis. For Facebook and Twitter, our analysis focused on text and any possible hyperlinks, while for Instagram, also images were analyzed, as they are central to the platform’s logic.

The analysis consisted of several phases. We first categorized all posts based on whether they included traditional media. A post was defined to include traditional media if: 1) the post contained a hyperlink leading to an external traditional media outlet, 2) the post contained explicit reference(s) to traditional media content, such as a direct quote by a party leader during a televised election debate, or 3) the post urged audiences to view specific traditional media content, (e.g., televised debate.)

We next categorized all posts as personalized or not personalized. The concept of personalization consists of three aspects: 1) the visibility of politicians, 2) the visibility of politicians’ personal characteristic, and 3) the visibility of politicians’ private lives. The visibility of politicians can be studied by counting the number of items mentioning at least one politician. (Van Aelst et al., 2012). Therefore, a post was categorized as personalized if: 1) the post or shared media referenced a politician by name, 2) the post was written by a politician who spoke in the first person, or 3) the post or media shared contained information about a politician’s personal characteristics or private life. After categorizing all posts in this way, we compared the personalization levels of posts containing traditional media shares with posts that did not contain traditional media.

In the third phase, we took the social media posts containing traditional media shares and categorized them based on the types of traditional media shared. Our definition of traditional media included different types of newspapers (both websites and print versions), television (both linear and streaming services), radio (both digital and streaming services), digital media (news platforms without a print presence), and partisan media, such as party newspapers. Websites and blogs were not classified as traditional media. In individual cases, several types of traditional media were shared in one post; in these situations, the item was categorized once into each of the applicable categories.

Finally, we determined the functions of the social media posts that contained traditional media shares and compared them to the functions of the posts that did not contain traditional media. The basis of this part of the analysis was formed by Benoit. (2007) functional theory of campaign discourse, which argues that election candidates use three functions—acclaims, attacks, and defenses—to appear preferable to other candidates. The applicability of functional theory to Finnish political culture has been criticized in the past, as Finnish political discussions include elements that do not belong to any of these categories (Isotalus, 2011; Paatelainen et al., 2016). Therefore, additional categories were created inductively during the analysis process through a close reading of the data.

This resulted in seven functions: 1) acclaims (stressing the candidate’s advantages or strengths), 2) attacks (attacking or criticizing the opponents), 3) defenses (refuting an attack by opponents), 4) added visibility (encouraging the reader to learn more about the candidate outside social media), 5) media criticism (criticizing the accuracy and objectivity of traditional media, allowing the candidate to challenge their media portrayal), 6) political analysis (showing the expertise, knowledge, and empathy of the candidate), and 7) other or unclear. The last category included posts where miscellaneous greetings, jokes and messages with no apparent purpose were presented.

When determining the function of a post, both its content and that of the traditional media shared were considered. For example, a newspaper article that was neutral in tone was categorized as an acclaim if it was used for that purpose in a social media post by a party leader. Similarly, a newspaper article criticizing one party leader or party was categorized as an attack, even if it was not accompanied by any comments when shared on social media. Posts with multiple functions were categorized according to the most prevalent function.

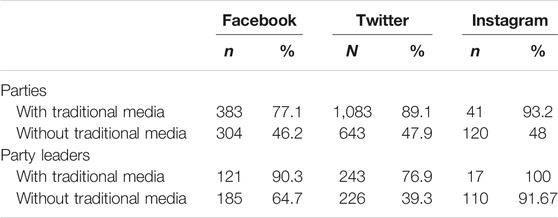

We first asked to what extent parties and their leaders utilized traditional media in their social media posts. The results showed that traditional media shares formed a significant portion of parties’ and their leaders’ social media campaign communication. Out of the 3,990 social media posts published by parties, 1,755 posts (44%) contained references to traditional media. On the other hand, the party leaders published 1,408 social media posts altogether, of which 467 posts (33.2%) included traditional media material. Traditional media were shared on all three platforms (Table 2).

Of the three social media platforms, Twitter registered the highest percentage of traditional media shared, followed by Facebook, and finally Instagram, where the portion of shared material was the lowest. Parties shared traditional media more often than party leaders.

Second, we asked to what extent traditional media shares were personalized and how this compared to the social media posts that did not contain traditional media. The nine parties published 3,990 social media posts altogether, of which 2,573 posts (64.5%) were personalized. The party leaders published 1,408 posts in total, of which 902 posts (64.1%) were personalized. The social media posts containing traditional media were more personalized than those without traditional media (Table 3). The differences between the two types of posts were statistically significant: χ2 (df = 1) = 24.04, p < 0.0001 (party leaders’ posts) and χ2 (df = 1) = 134.11, p < 0.0001 (parties’ posts).

Over four fifths of the parties’ and leaders’ posts that contained traditional media were personalized, while the corresponding figure for social media posts without traditional media was closer to half of all posts. There were differences between the social media platforms, as outlined in Table 4.

TABLE 4. Personalization of social media posts on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram (with and without traditional media).

For both parties and their leaders, Instagram contained the highest percentage of personalized posts, even if the posts did not include traditional media material. In the case of parties, Twitter posts were more personalized than Facebook posts regardless of traditional media material shared. Party leaders’ Facebook posts were more personalized than Twitter posts.

Our third research question concerned the types of traditional media shared. The analysis showed that parties and their leaders utilized a wide range of traditional media in their social media posts, as presented in Table 5.

Television was the most shared type of traditional media for both parties (50.3% of all media shares) and their leaders (39% of all media shares). After television, parties most often shared content from partisan media (16.5% of all media shares), followed by newspapers (16.4%) and digital media (7.9%). For party leaders, newspapers (23.1%) and digital media (13.5%) were more popular than partisan media (12.4%). For both parties and their leaders, afternoon papers and radio were the least referenced types of traditional media.

A closer look at the three social media platforms revealed some differences. Television was the most often shared media type for parties in the case of Twitter (61.3%) and Instagram (79.6%) but not on Facebook, which fell second to partisan media outlets (29.2–22.7%) and where the types of media shared were divided more evenly. In the case of party leaders, television was the most popular type of traditional media shared on all three platforms. However, the percentage of television content shared was highest on Instagram (70.6%), while on the other two platforms, the types of traditional media party leaders shared were divided more evenly (37.4% on Facebook and 38% on Instagram). Facebook was the only platform where both digital media (19.4%) and afternoon papers (19.4%) were more popular than newspapers (18.7%).

Finally, our fourth question concerned the functions of traditional media shared by parties and their leaders in their social media posts and how these compared to the functions of social media posts without traditional media. The results of this analysis are presented in Table 6.

In the case of parties, the most common function of posts containing traditional media was acclaims (35.6%), followed by added visibility (32%) and political analysis (17.4%). Acclaims (34.3%) and added visibility (28.4) were also the two largest categories in the party posts that did not contain traditional media, but instead of political analysis, the third largest category was other or unclear (18.1%). Attacks were more common in party posts containing traditional media (12.7%) than in those without traditional media (4.7%). Defenses and media criticism were both rare, regardless of whether the parties’ posts shared traditional media content or not. There was a statistically significant difference between the parties’ posts that contained traditional media and those that did not: χ2 (df = 6) = 331.03, p < 0.0001.

As for party leaders, the most common function of posts containing traditional media content was added visibility (34.9%), followed by acclaims (26.1%) and attacks and political analysis (both 11.1% of the posts that contained traditional media). The most common function of the party leader’s posts that did not contain traditional media was added visibility (29.9%), followed by other or unclear (29.4%) and acclaims (21.6%). There were again significantly fewer attacks (4.1%) in the party leader posts that did not contain traditional media compared to the party leader’s posts that did. Defenses and media criticism were again rare, regardless of whether the party leader’s posts contained traditional media or not. There was a statistically significant difference between the party leaders’ posts that contained traditional media and those that did not: χ2 (df = 6) = 160.53, p < 0.0001.

There were no significant differences between the three social media platforms.

Previous research has shown that traditional media also retains its agenda-setting power in the hybrid media system, determining which topics are brought up and discussed on social media (e.g., Harder et al., 2016; Langer and Gruber, 2021). Our results are in line with this research, as the analysis performed here shows that traditional media content formed a significant portion of the social media campaign communication of parties and their leaders during the 2019 Finnish parliamentary elections. Parties and their leaders commented on news, encouraged their audience to consume traditional media content, live-tweeted election debates, and shared links to party leaders’ interviews. This aligns with the suggestion of Chadwick et al. (2016), who argued that “much of the campaign communication discussed online is hybrid, initially beginning life on television or in the press and then travelling across online media through campaign promotion and/or citizen discussion” (p. 4).

Our results indicate that parties’ and their leaders’ use of traditional media in their social media campaign communication was, to at least some extent, strategic. This became visible in the differences between the three social media platforms, suggesting that the affordances and genres of the platforms were considered when choosing to share certain types of traditional media content (for an overview of the genres and affordances of social media platforms, see Kreiss et al., 2018). The types of traditional media shared were also chosen strategically. The type of media that was most often shared was television, which is also often regarded as the most influential media in political campaign communication (Jensen and Schwartz, 2020). By encouraging the audience to watch televised debates and interviews and by sharing soundbites from these interviews, parties and their leaders can harness the power of television on social media. Equally significant was what was not shared. Although afternoon papers actively write about politics, it was rare for parties and their leaders to share content from these papers on their social media, suggesting that they perceived other kinds of content as more useful for their ethos building. Finally, the functions of traditional media shares also point to strategic considerations. Added visibility and acclaims were the two most common functions of posts containing traditional media, demonstrating that the primary purpose of hybrid media campaign posts was to provide positive visibility and publicity to individual politicians.

Our results also provide a new understanding of the concept of personalization of politics. The use of social media in political communication has been argued to increase the personalization of politics, as social media logic favors personal connections and personal stories (e.g., Enli and Skogerbø, 2013). In our analysis, however, we concluded that social media posts containing traditional media were more personalized than posts not including traditional media, suggesting that it may be more appropriate to speak of hybrid media personalization rather than social media personalization. Therefore, traditional media does not only influence the topics that are discussed online but also how and through which perspective they are discussed. On the other hand, the fact that most of the traditional media content shared was personalized also suggests that this kind of hybrid media campaign communication was perceived first and foremost as a tool for providing added positive visibility to candidates, again implying strategic considerations.

We have also shown that traditional media shares have many functions in the social media campaign communication of parties and their leaders, the most common of which are added visibility and acclaims. However, these were also two of the most common functions of social media posts that did not contain traditional media, which tells us that the parties and their leaders perceived social media as suitable platforms for this type of campaign communication in general. Nevertheless, using traditional media for acclaiming can act as a form of rhetorical support, as on social media, it can be more credible to share praise written by others instead of praising oneself (Malhotra and Malhotra, 2016). Therefore, sharing positive evaluations written by seemingly objective journalists can help parties and their leaders establish preferability on social media. Similarly, using traditional media content to attack opponents may be an effective strategy in election campaign communication, as, according to previous research, using a surrogate to attack opponents may help protect the candidate from the voter backlash linked to perceived mudslinging (Benoit, 2007). It is likely that this was acknowledged by the parties and their leaders, as the social media posts with traditional media contained more attacks than the posts without traditional media.

Benoit. (2007) functional theory of political campaign discourse formed the basis for our functional analysis. Previously, the theory was applied in the analysis of the 2006 (Isotalus, 2011) and 2012 Finnish presidential debates (Paatelainen et al., 2016). In this study, we applied a modified version of the theory, which included only the main communicative functions and disregarded the subcategories of policy and character. As with previous studies on Finnish presidential elections, the results showed that not all parties’ and their leaders’ social media posts fit the categories of functional theory. The previous studies have suggested that the functions of Finnish campaign discourse should also include an analysis of the current situation, in which the candidates attempt to position themselves as experts (Isotalus, 2011; Paatelainen et al., 2016). The same function could be identified here, supporting the argument that these expressions of expertise are indeed a function of Finnish political campaign discourse. Moreover, while a large percentage of the functions connected to establishing preferability, our results showed that the hybrid media campaign communication of parties and their leaders also had other functions, such as increasing the candidates’ visibility or functions related to making the campaign a success (Hixson, 2018).

As with all studies, ours has certain limitations. First, the analysis focused only on parties and their leaders; including a larger number of candidates may have influenced the results. Second, the research data were collected during a month-long period before the parliamentary elections; it is possible that traditional media is utilized differently outside of the active campaign period. Third, our decision to adopt a single post as the unit of analysis may have impacted the results, as especially long Facebook or Instagram posts may have served multiple functions and included both personalized and non-personalized elements.

Overall, the results show that parties and their leaders in Finland actively use hybrid media systems to their advantage to produce added visibility and establish preferability in relation to opponents. Their use of hybrid media is highly personalized, suggesting the existence of hybrid personalization.

Although this research was set in the Finnish context, thus providing specific results on the Finnish campaign communication environment, these results may also apply to other national contexts. Yet, this requires more research in different contexts and elections. So far, research on political communication in hybrid media systems has largely been focused on how politicians can use social media in order to gain traditional media visibility; our research broadens existing knowledge on the hybrid media system by showing how politicians utilize it beyond gaining traditional media visibility.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

All authors contributed equally to the planning of the research project. Data gathering was performed by LP and EK. The first version of the research paper was written by LP, with EK and PI participating equally in the editing and revising phase.

This research paper is based on a research project funded by the CV Akerlund Media Foundation.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The authors would like to thank Jari Jussila for his help with the project.

Adam, S., and Maier, M. (2010). “Personalization of Politics A Critical Review and Agenda for Research,” in Communication Yearbook. Editor C. T. Salmon (London, UK: Routledge), 34, 213–257. doi:10.1080/23808985.2010.11679101

Baxter, G., and Marcella, R. (2012). Does Scotland ‘like’this? Social media Use by Political Parties and Candidates in Scotland during the 2010 UK General Election Campaign. Libri 62 (2), 109–124. doi:10.1515/libri-2012-0008

Benoit, W. L. (2011). “Content Analysis in Political Communication,” in The Sourcebook for Political Communication Research. Editors E. P. Bucy, and R. L. Holbert (London, UK: Routledge).

Bronstein, J., Aharony, N., and Bar-Ilan, J. (2018). Politicians’ Use of Facebook during Elections: Use of Emotionally-Based Discourse, Personalization, Social media Engagement and Vividness. Ajim 70 (5), 551–572. doi:10.1108/ajim-03-2018-0067

Chadwick, A., Dennis, J., and Smith, A. P. (2016). “Politics in the Age of Hybrid media: Power, Systems and media Logics,” in The Routledge Companion to Social Media and Politics. Editors A. Bruns, E. Gunn, E. Skogerbø, A. O. Larsson, and C. Christensen (London, UK: Routledge), 1–33.

Chadwick, A. (2013). The Hybrid media System: Politics and Power. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Chadwick, A., Vaccari, C., and O’Loughlin, B. (2018). Do tabloids Poison the Well of Social media? Explaining Democratically Dysfunctional News Sharing. New Media Soc. 20 (11), 4255–4274. doi:10.1177/1461444818769689

Conway-Silva, B. A., Filer, C. R., Kenski, K., and Tsetsi, E. (2018). Reassessing Twitter’s Agenda-Building Power: An Analysis of Intermedia Agenda-Setting Effects during the 2016 Presidential Primary Season. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 36 (4), 469–483. doi:10.1177/0894439317715430

Enli, G., and Moe, H. (2013). Introduction to Special Issue. Social media and Election Campaigns—Key Tendencies and Ways Forward. Inf. Commun. Soc. 16 (5), 637–645. doi:10.1080/1369118x.2013.784795

Enli, G. S., and Skogerbø, E. (2013). Personalized Campaigns in Party-Centric Politics: Twitter and Facebook as Arenas for Political Communication. Inf. Commun. Soc. 16 (5), 757–774. doi:10.1080/1369118x.2013.782330

Enli, G. (2017). Twitter as arena for the Authentic Outsider: Exploring the Social media Campaigns of Trump and Clinton in the 2016 US Presidential Election. Eur. J. Commun. 32 (1), 50–61. doi:10.1177/0267323116682802

Francia, P. L. (2018). Free media and Twitter in the 2016 Presidential Election: The Unconventional Campaign of Donald Trump. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 36 (4), 440–455. doi:10.1177/0894439317730302

Harder, R. A., Paulussen, S., and Van Aelst, P. (2016). Making Sense of Twitter Buzz: The Cross-media Construction of News Stories in Election timeMaking Sense of Twitter Buzz. Digital Journalism 4 (7), 933–943. doi:10.1080/21670811.2016.1160790

Hawthorne, J., Houston, J. B., McKinney, M. S., and Baumgartner, J. C. (2013). Live-tweeting a Presidential Primary Debate: Exploring New Political Conversations. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 31 (5), 552–562. doi:10.1177/0894439313490643

Hayes, D. (2009). Has Television Personalized Voting Behavior? Polit. Behav. 31 (2), 231–260. doi:10.1007/s11109-008-9070-0

Hixson, T. K. (2018). “Tweets as Tools—Exploring the Campaign Functions of Candidates’ Tweets in the 2016 Presidential Campaign,” in The Presidency and Social media: Discourse, Disruption, and Digital Democracy in the 2016 Presidential Election. Editors D. Schill, and J. A. Hendricks (London, UK: Routledge), 263–281.

Isotalus, P. (2011). Analyzing Presidential Debates: Functional Theory and the Finnish Political Culture. Nordicom Rev. 32 (1), 31–43. doi:10.1515/nor-2017-0103

Jensen, J. L., and Schwartz, S. A. (2020). The 2019 Danish General Election Campaign: The 'Normalisation' of Social Media Channels? Scand. Polit. Stud. 43 (2), 96–104. doi:10.1111/1467-9477.12165

Johnson, T. J., and Kaye, B. K. (2014). Credibility of Social Network Sites for Political Information Among Politically Interested Internet Users. J. Comput-mediat Comm. 19, 957–974. doi:10.1111/jcc4.12084

Ju, A., Jeong, S. H., and Chyi, H. I. (2014). Will Social Media Save Newspapers? Journalism Pract. 8 (1), 1–17. doi:10.1080/17512786.2013.794022

Jünger, J., and Keyling, T. (2019). Facepager. An Application for Automated Data Retrieval on the Web. Available at: https://github.com/strohne/Facepager/.

Jungherr, A. (2016). Twitter Use in Election Campaigns: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Inf. Tech. Polit. 13 (1), 72–91. doi:10.1080/19331681.2015.1132401

Karlsen, R., Enjolras, B., Stromer-Galley, J., and Chadwick, A. (2016). Styles of Social media Campaigning and Influence in a Hybrid Political Communication System: Linking Candidate Survey Data with Twitter Data. The Int. J. Press/Politics 21 (3), 338–357. doi:10.1177/1940161216645335

Karvonen, L. (2009). The Personalization of Politics: A Study of Parliamentary Democracies. Colchester: ECPR Press.

Klinger, U. (2013). Mastering the Art of Social Media. Inf. Commun. Soc. 16 (5), 717–736. doi:10.1080/1369118x.2013.782329

Klinger, U., and Svensson, J. (2015). The Emergence of Network media Logic in Political Communication: A Theoretical Approach. New Media Soc. 17 (8), 1241–1257. doi:10.1177/1461444814522952

Kreiss, D., Lawrence, R. G., and McGregor, S. C. (2018). In Their Own Words: Political Practitioner Accounts of Candidates, Audiences, Affordances, Genres, and Timing in Strategic Social media Use. Polit. Commun. 35, 8–31. doi:10.1080/10584609.2017.1334727

Kruikemeier, S., Gattermann, K., and Vliegenthart, R. (2018). Understanding the Dynamics of Politicians' Visibility in Traditional and Social media. Inf. Soc. 34 (4), 215–228. doi:10.1080/01972243.2018.1463334

Kruikemeier, S., Van Noort, G., Vliegenthart, R., and de Vreese, C. H. (2013). Getting Closer: The Effects of Personalized and Interactive Online Political Communication. Eur. J. Commun. 28 (1), 53–66. doi:10.1177/0267323112464837

Langer, A. I. (2007). A Historical Exploration of the Personalisation of Politics in the Print Media: The British Prime Ministers (1945-1999). Parliamentary Aff. 60 (3), 371–387. doi:10.1093/pa/gsm028

Langer, A. I., and Gruber, J. B. (2021). Political Agenda Setting in the Hybrid media System: Why Legacy media Still Matter a Great deal. Int. J. Press/Politics 26 (2), 313–340. doi:10.1177/1940161220925023

Larsson, A. O., and Kalsnes, B. (2014). 'Of Course We Are on Facebook': Use and Non-use of Social media Among Swedish and Norwegian Politicians. Eur. J. Commun. 29 (6), 653–667. doi:10.1177/0267323114531383

Larsson, A. O., and Moe, H. (2012). Studying Political Microblogging: Twitter Users in the 2010 Swedish Election Campaign. New Media Soc. 14 (5), 729–747. doi:10.1177/1461444811422894

Malhotra, C. K., and Malhotra, A. (2016). How CEOs Can Leverage Twitter. MIT Sloan Manage. Rev. 57 (2), 73–80.

Metz, M., Kruikemeier, S., and Lecheler, S. (2020). Personalization of Politics on Facebook: Examining the Content and Effects of Professional, Emotional and Private Self-Personalization. Inf. Commun. Soc. 23 (10), 1481–1498. doi:10.1080/1369118x.2019.1581244

Nelimarkka, M., Laaksonen, S.-M., Tuokko, M., and Valkonen, T. (2020). Platformed Interactions: How Social media Platforms Relate to Candidate-Constituent Interaction during Finnish 2015 Election Campaign. Soc. Media + Soc. 6 (2), 1–17. doi:10.1177/2056305120903856

Newman, N., Fletcher, R., Levy, D. A. L., and Nielson, R. K. (2016). Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2016. Oxford, UK: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

Otto, L. P., Glogger, J., and Maier, M. (2018). Personalization 2.0?—Testing the Personalization Hypothesis in Citizens’, Journalists’, and Politicians’ Campaign Twitter Communication. Communications 44 (4), 359–381. doi:10.1515/commun-2018-2005

Paatelainen, L., Croucher, S., and Benoit, W. L. (2016). A Functional Analysis of the Finnish 2012 Presidential Elections. Stud. Media Commun. 4 (2), 70–80. doi:10.11114/smc.v4i2.1826

Rahat, G., and Kenig, O. (2018). From Party Politics to Personalized Politics? Party Change and Political Personalization in Democracies. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Seethaler, J., and Melischek, G. (2019). Twitter as a Tool for Agenda Building in Election Campaigns? the Case of Austria. Journalism 20 (8), 1087–1107. doi:10.1177/1464884919845460

Singer, J. B. (2014). User-generated Visibility: Secondary Gatekeeping in a Shared media Space. New Media Soc. 16 (1), 55–73. doi:10.1177/1461444813477833

Skogerbø, E., and Krumsvik, A. H. (2015). Newspapers, Facebook, and Twitter—Intermedial Agenda Setting in Local Election Campaigns. Journalism Pract. 9 (3), 350–366. doi:10.1080/17512786.2014.950471

Small, T. A. (2017). “Parties, Leaders and Online Personalization: Twitter in Canadian Electoral Politics,” in Twitter and Elections Around the World: Campaigning in 140 Characters or Less. Editors R. Davis, C. Holtz-Bacha, and M. R. Just (London, UK: Routledge), 173–190.

Smith, M., Ceni, A., Milic-Frayling, N., Shneiderman, B., Mendes Rodrigues, E., Leskovec, J., et al. Social Media Research Foundation(2010). NodeXL: A Free and Open Network Overview, Discovery and Exploration Add-In for Excel 2007/2010/2013/2016. Available at: http://www.smrfoundation.org.

Strandberg, K., and Borg, S. (2020). “Internet Ja sosiaalinen media osana vaalikampanjaa [Internet and Social media as a Part of the Election Campaign],” in Politiikan ilmastonmuutos: Eduskuntavaalitutkimus 2019 [Climate Change in Politics: Parliamentary Election Survey 2019]. Editors S. Borg, E. Kestilä-Kekkonen, and H. Wass (Helsinki: Ministry of Justice, Reports and Guidelines), 103–123.

Strandberg, K., and Carlson, T. (2021). “Media and Politics in Finland,” in Power, Communication, and Politics in the Nordic Countries. Editors E. Skogerbø, Ø. Ihlen, N. N. Kristensen, and L. Nord (Gothenburg: Nordicom), 69–89.

Strömbäck, J., and Kiousis, S. (2014). “Strategic Political Communication in Election Campaigns,” in Political Communication. Editor C. Reinemann (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter), 249–266.

Sweetser, K. D., Golan, G. J., and Wanta, W. (2008). Intermedia Agenda Setting in Television, Advertising, and Blogs during the 2004 Election. Mass Commun. Soc. 11 (2), 197–216. doi:10.1080/15205430701590267

Vaccari, C., Chadwick, A., and O'Loughlin, B. (2015). Dual Screening the Political: Media Events, Social media, and Citizen Engagement. J. Commun. 65 (6), 1041–1061. doi:10.1111/jcom.12187

Van Aelst, P., Sheafer, T., and Stanyer, J. (2012). The Personalization of Mediated Political Communication: A Review of Concepts, Operationalizations and Key Findings. Journalism 13 (2), 203–220. doi:10.1177/1464884911427802

Keywords: campaign communication, hybrid media system, social media, content analysis, personalization

Citation: Paatelainen L, Kannasto E and Isotalus P (2022) Functions of Hybrid Media: How Parties and Their Leaders Use Traditional Media in Their Social Media Campaign Communication. Front. Commun. 6:817285. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2021.817285

Received: 17 November 2021; Accepted: 20 December 2021;

Published: 10 January 2022.

Edited by:

Pradeep Nair, Central University of Himachal Pradesh, IndiaReviewed by:

Argyro Kantara, Cardiff University, United KingdomCopyright © 2022 Paatelainen, Kannasto and Isotalus. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Laura Paatelainen, bGF1cmEucGFhdGVsYWluZW5AdHVuaS5maQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.