- Social and Global Studies Centre, School of Global, Urban and Social Studies, RMIT University, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

Nation states increasingly apply electronic surveillance techniques to combat serious and organised crime after broadening and deepening their national security agendas. Covertly obtained recordings from telephone interception and listening devices of conversations related to suspected criminal activity in Languages Other Than English (LOTE) frequently contain jargon and/or code words. Community translators and interpreters are routinely called upon to transcribe intercepted conversations into English for evidentiary purposes. This paper examines the language capabilities of community translators and interpreters undertaking this work for law enforcement agencies in the Australian state of Victoria. Using data collected during the observation of public court trials, this paper presents a detailed analysis of Vietnamese-to-English translated transcripts submitted as evidence by the Prosecution in drug-related criminal cases. The data analysis reveals that translated transcripts presented for use as evidence in drug-related trials contain frequent and significant errors. However, these discrepancies are difficult to detect in the complex environment of a court trial without the expert skills of an independent discourse analyst fluent in both languages involved. As a result, trials tend to proceed without the reliability of the translated transcript being adequately tested.

1 Introduction

Electronic surveillance technology is an effective means of collecting evidence used to prosecute serious and organised crime. Evidence presented in drug-related trials is often in the form of audio recordings of conversations held in LOTE. The recordings are usually obtained through telephone interception or covertly placed listening devices. The audio recordings are presented as primary evidence in the form of an audio file. To make sense of the evidence, the audio files are accompanied by transcripts in English having been translated from languages other than English (LOTE). These translated transcripts often contain drug-related code words and jargon.

Research conducted at RMIT University, Melbourne, Australia aimed to determine the reliability of translated transcripts presented as evidence in court in drug-related trials. The research focused on determining:

1) What evidence, if any, points to systemic deficiencies in language capability relied upon to combat illicit drug-related crime?

2) How do identified deficiencies affect the judicial process?

3) What causal factors contribute to these deficiencies?

2 Context of the Research

The context of this enquiry is framed within two key areas as follows: at the micro level involving linguistic analysis of translated transcripts from electronic surveillance related to serious and organised crime revealing evidence of language capability deficiency; and at the macro level where analysis findings reveal causal factors leading to the distortion of evidence in court trials.

Evidence of deficiencies at the micro level show that translated transcripts of intercepted telephone calls presented as evidence in court used to prosecute serious and organised crime contained significant errors, many of which were not detected by the court. At the macro level, the research revealed significant deficiencies in interpreter and translator training, workplace practices, and the process of skills recognition of professional interpreters and translators. Collectively, the data provide evidence of systemic deficiencies in language capability and, when viewed through the lens of criminal justice, the findings reveal significant and systemic distortions of evidence presented in criminal trials presenting a clear risk to the integrity of the judicial process.

3 Literature Review

Review of the literature reveals a gap in knowledge relating to the accuracy, or perceived accuracy, of translated transcripts used for evidentiary purposes, particularly relating to drug-related code words and jargon from languages other than English (LOTE) used as evidence in court. This is most likely due to the unique specialist skills and experience required to conduct this type of research. [Moreno (2004), 34] noted a lack of empirical research concerning the accuracy of alleged drug-related codewords presented as evidence in court, stating that “There is no indication in any related literature that there has ever been a real effort to study or test the reliability of any drug jargon definitions.” A review of the literature at the time of writing reveals that the empirical research discussed in this paper is unique and fills the gap in knowledge Moreno had previously identified. Importantly, [Moreno (2004), 35] states that “[t]he problem with the lack of objective data is that it prevents judges from measuring the reliability of this evidence pretrial and, once admitted, prevents jurors from gauging its weight,” adding that “In the context of drug jargon interpretation, judges and juries cannot measure the probability that expert testimony is reliable by comparison to a professional standard or empirical evidence.” More recently, [Capus and Griebel (2021), 74] researched the visibility of translators responsible for producing translated transcripts, and state that research in this area is lacking. A review of the literature reveals that this research may be the first to contain objective empirical data that sheds light on deficiencies in translated transcripts that often remain undetected during drug-related trials.

3.1 Transcription: A Specialised Skill

Transcribing LOTE directly into written English is a specialised skill not normally practiced by community interpreters and translators. Highly developed listening skills are required of the translator or interpreter to capture important elements of evidentiary value when producing translated transcripts. National skills recognition of interpreters and translators is the responsibility of the National Accreditation Authority for Translators and Interpreters (NAATI). NAATI, a private business owned by the state and federal governments of Australia, conducts testing for interpreters and translators and issues certification for successful candidates. It also recertifies those interpreters and translators who successfully revalidate their skills. The transcription of spoken LOTE into written English is a specialised skill that is not tested nor certified by NAATI. Law enforcement agencies rely upon professional certification of interpreters and translators issued by NAATI as a minimum level of proficiency for producing translated transcripts for evidence in court. NAATI testing does not specifically address transcription skills and NAATI does not provide formal skills recognition for this form of specialised skill.

3.2 Transcription Approaches

Translators and interpreters who participated in the research claimed that they had not been given specific training on transcription methodology prior to being tasked with producing translated transcripts for evidentiary purposes. Court interpreters agreed at interview that producing translated transcripts is a specialised skill requiring high-order listening skills above those required for community interpreting. In Australia, it is common practice for the law enforcement translator or interpreter to transcribe the intercepted language other than English (LOTE) directly into written English for evidence purposes. Courts are not provided with a transcript of the intercepted spoken LOTE in the source language (the LOTE). Australian courts are provided with the audio recording of intercepted communications and a translated transcript in English. Therefore, the transcription process is not transparent to the court, the Prosecution or the Defence.

Australia has yet to establish nationally recognised guidelines to produce translated transcripts for court purposes. The research revealed that there was a high level of inter-dependance relied upon by interpreters and translators tasked with producing translated transcripts. Participants stated that they learn from each other in the absence of formal transcription training and skills recognition. The reported ad-hoc nature of acquiring transcription skills presents an unacceptable risk that systemic deficiencies in approaches to the transcription task will remain embedded within the law enforcement transcription environment.

The National Association for Judiciary Interpreters and Translators (NAJIT) in the US published a position paper providing “general guidelines and minimum requirements for transcript translation in any legal setting” (NAJIT, 2009). In the US, it is mandatory that transcription is conducted by transcribing the spoken LOTE into written LOTE by one person, then the written LOTE is translated into English by a certified translator. The Home Office in the United Kingdom has produced guidelines for the engagement of interpreters in criminal investigations where transcription is required. These guidelines are not made available to the public and carry a privacy marking of “Official Sensitive” [Home Office (2021), 13].

The US approach provides a clear audit trail of how the intercepted speech was transcribed and translated when presented as evidence in court. However, this is a process not normally practiced in Australia. Transcribing from spoken LOTE directly into written English, as practiced in Australia, is likely to result in evidence presented in the form of disjointed and mostly non-sensical English purported to have been said in the intercepted LOTE. The reason for using this method in Australia is assessed as being driven by financial resource constraints and the absence of policy guidance in relation to the methodology to be used when producing translated transcripts for evidentiary purposes.

Problems have been identified with evidence in the form of recordings, transcripts, and translations presented in US courts. Fishman (2006) states that juries may find recordings played in English difficult to understand as they often contain nuances, codewords, jargon and/or idioms. Written translated transcripts are often distributed to jurors as an aid to understanding the content of recordings. This is particularly the case where the translated transcript contains jargon, codewords or slang translated from a LOTE. Jurors cannot make use of evidence in the form of audio recordings of conversations held in LOTE unless they are assisted with an English translation. The level of subjectivity is significantly increased when a LOTE has been translated into English, as the translating and interpreting process is “much more an art than a science, let alone a mechanical process” [Fishman (2006), 476]. Laster and Taylor (1995) and Nakane (2009) share this viewpoint.

3.3 Transcription Accuracy

Transcribing covertly obtained recordings in LOTE that contain code words and/or jargon is complex. The process involves an approach requiring the translator to adopt translation strategies that seek to preserve notions of translation accuracy to preserve the integrity of the evidence. Translators are required to exercise critical decision making when producing translated transcripts for evidentiary purposes. Without a systematic approach to transcribing from LOTE into English, the resultant product is likely to contain errors bringing into question the key attribute of reliability and may be subject for unjustified interference by the translator. It is often the case that the translator struggles to transfer exact meaning into English due to distinct differences between languages. Exact meaning is elusive and the distance between an utterance in a LOTE and how it has been translated largely depends upon context. [Baker (2011), 60–61], states that:

Accuracy is no doubt an important aim in translation, but it is also important to bear in mind that the use of common target-language patterns which are familiar to the target reader plays an important role in keeping the communication channels open.

In reference to the field of forensic translation, [Darwish (2012), 75], states that it is important that “evidentiary clues are not sacrificed for the sake of naturalness.” The author concedes that it is inevitable that compromises will have to be made, although the preservation of meaning should be maintained being careful to avoid unjustifiable intervention or interference by the translator. A sound approach to the translation process will lower the risk of evidence being intentionally or inadvertently distorted. Specialised skills training and knowledge is required to produce covertly obtained translated transcripts. Darwish proposes that “in most situations” translated documentation presented as evidence is translated by those who have significant biases or are “simply incompetent.” The author states that this adversely affects forensic analysis and may contribute to miscarriages of justice (2012, 19). The concerning issue of transcript translation not being adequately assessed for reliability is not peculiar to the Australian context. [NAJIT (2009), 6] states that “transcript translation remains an area that is not uniformly regulated in courts nationwide.”

Translators working for law enforcement are required to transfer equivalent meaning at word and, where possible, sentence level as closely as possible while also conveying sense. NAJIT guidelines (2009, 6) state that translations should contain attributes of accuracy and completeness and, where appropriate, be natural and idiomatic while faithfully reflecting register, style, and tone of the original text. However, NAJIT has not provided a definition of accuracy. The idea of accuracy is an ambiguous concept in terms of the translation process and when faced with evaluating a translated text. First, the translator conducts an analysis of the original text and then interprets what the text means within the context it is placed. The translator is also required to consider the assumed meaning intended by the originator of the source utterance in LOTE. Once the translator has formed an impression of context, the process of transcribing the original text into English can begin. Therefore, it is important that the translator has access to information about context extrinsic of the original text as part of the analysis and decision-making process. Only then is the translator suitably equipped to transfer intended meaning from LOTE into English while preserving the evidentiary value of the original text. [NAJIT (2009), 6] notes that contextual information may assist the translator in “comprehending distorted sound” or clarifying “ambiguous utterances” but with an emphasis that any final translation should contain “only what he or she actually hears in the source recording.”

Fraser et al. (2011) researched the potential influence on the hearer of recorded conversations from “priming” their senses by providing them with background information. The research revealed that it is likely that people will hear what they expect to hear based on extrinsic information provided prior to listening to the recording. It follows that law enforcement translators may also be influenced by background or intelligence information when transcribing intercepted communications. This creates a dilemma for the law enforcement translator where they either produce a translated transcript in a vacuum without information relating to context, or they have access to background information that may influence what they hear in the source recording. Whichever approach is taken to the transcription process, the law enforcement translator still needs to document what was heard and, as closely as possible, convey the communicative function of the intercepted utterances in a format acceptable as evidence. Ideally, the final product is a translated transcript in English that makes sense. Hence, the importance of transcribing the spoken LOTE into written LOTE prior to it being translated into English so that transparency of the transcription process is achieved. This way, any influence of priming or unjustified intervention by the translator can be more easily detected during a quality control process.

It is highly probable that the translator will interfere during the translation process. Translators should declare where they have interfered during the translation process to convey sense. [House (2009), 42] proposes that “a translated text can never be identical to its original, it can only be equivalent to it in certain aspects.” This raises a dilemma when it comes to the quality control of translated transcripts. When assessing translations for accuracy, equivalence, and objectivity, one may arrive at alternative acceptable translated versions of the original LOTE text. Internal consistency, linguistic integrity and translation integrity are dependent upon the strategies applied by the translator. Attempting to maintain a balance between readability and accuracy is an inherent part of the transcription process (cf. Tilley, 2003).

Importance of contextual information to the translation process cannot be underestimated. Consensus in relation to translation accuracy is dependent upon a mutually agreed perspective of what is known and what is expected. In criminal trials, the Prosecution and the Defence are required to agree that the translated transcripts are accurate prior to a trial commencing. However, the notion of accuracy is often determined at word level. The contextual meaning of words contained in translated transcripts is determined by the jury through the adversarial process. Prior to hearing arguments put by the Prosecution and the Defence, the jury is provided with a copy of the translated transcripts in English. The jury will then hear what the Prosecution and Defence allege those utterances mean within the alleged context of the evidence presented. The jury, being the trier of fact, is charged with determining the accuracy and reliability of the evidence presented at trial.

3.4 Translated Transcripts and the Expert Witness

The practice of calling police officers as expert witnesses in relation to the translation of code words and jargon is a significant area of investigation in this research. Police officers often provide expert witness testimony to explain the meanings of terms and phrases contained in translated transcripts. This is to assist the jury to understand the alleged context in which the intercepted conversations in LOTE took place. Expert witness testimony in these circumstances is often delivered by monolingual police officers who further interpret the meaning of alleged drug-related code words contained in translated transcripts.

Police officers in the United States routinely testify on the modus operandi of drug traffickers and dealers and how drug jargon is to be translated. Moreno (2005) states that they are called upon to testify by the Prosecution on the basis that:

1) Illicit-drug offenders routinely use drug-related codewords and jargon.

2) Jurors are unlikely to understand drug-related terminology without expert assistance.

3) Police officers are proficient in the identification and translation of drug-related jargon

It has been shown that Judges are reluctant to question the expertise of police officers who testify as expert witnesses called to explain the meaning of drug-related code words and jargon (Moreno, 2005). In United States v. Boissoneault 926 F.2d 230, 23 (2d Cir. 1991) the court of appeal held that “experienced narcotics agents may explain the use and meaning of codes and jargon developed by drug dealers to camouflage their activities.” However, jurors may become confused when hearing testimony proffered by a police officer who is both the police investigator and the expert witness. The confusion arises from the question of whether the testimony is based on the police officer’s general experience or whether the testimony is drawn from the officer’s role as investigator. Moreno (2005) asserts that the court will usually accept expert evidence proffered by police officers as credible and accurate.

Research has been conducted in relation to potential systemic biases in the judicial system, but few studies have been carried out on the reliability of translated transcripts (Nunn, 2010). Nunn’s research revealed that transcripts are subject to distortion to add weight to the evidence in favour of the Prosecution in criminal trials and estimates that 81 per cent of “wiretaps” relate to targeting the illicit-drug trade. Importantly, Nunn (2010) found systemic police bias influenced the transcription process. A police officer with relevant experience, training and knowledge may give evidence as an expert witness in relation to drug-related code words as they appear in a translated transcript into English, however, this testimony is based upon the assumption that the translated transcript is accurate. This research reveals that trials commence without the accuracy of translated transcripts having been challenged due to resource constraints. This therefore increases the potential risk of accused persons not receiving a fair trial.

4 Methods

Identifying potential or actual deficiencies in foreign language capability relied upon by law enforcement agencies requires access to reliable and credible sources of data that is not subject to publication restrictions due to the sensitive nature of law enforcement or national security related operations. The public court system provides an opportunity to observe and collect qualitative and quantitative data relating to serious and organised crime available in the public domain. The triangulation of four data collection methods ensured validity and reliability of the research findings. The first method involved observation of three drug-related trials held in the County Court of Victoria from 2012 to 2014. These trials provided direct access to audio recordings in Vietnamese and associated translated transcripts relied upon by law enforcement agencies used as evidence to prosecute persons accused of carrying out acts of serious and organised crime. The translated transcripts were produced by community interpreters and/or translators employed by law enforcement agencies, many of whom are contractors also working for one or multiple government and private agencies. Extracts from translated transcripts contained in this paper provide a detailed analysis of evidence revealing Australia’s deficiencies in the forensic translation process. The second approach was to interview County Court judges, Prosecution and Defence barristers, Court Interpreters, and interpreters/translators who had experience in relation to producing translated transcripts presented as evidence in court. Third, transcripts from court proceedings were analysed. The fourth method involved quantifying data retrieved from the AUSTLII database.1

This article draws mainly on the first tier of data collection conducted during the observation of three criminal trials heard in the Victorian County Court between May 2012 and March 2014 where translated transcripts were used as evidence. The field researcher2 recorded courtroom activity through extensive note taking to document details and events as electronic recording of trials is not permitted in the Victorian County Court.

Observation of the three trials enabled the development of a data collection strategy to answer the previously mentioned research questions. The field researcher is a professional Vietnamese translator with experience in transcribing intercepted communications for law enforcement and military purposes. Therefore, data collection efforts were focused on trials where translated transcripts from Vietnamese to English were presented as evidence in drug-related cases. The translated transcripts were of conversations held in Vietnamese that had been covertly recorded by telephone interception or listening device. The field researcher directly observed more than 100 h of trial proceedings across the three separate trials comprising the three case studies in addition to a further three trials on an opportunity basis. Participant-observation methods were not applied. The researcher did not attempt to influence the conduct of the three trials or the court environment during the observation period. The researcher listened to the covertly obtained telephone intercept and listening device recordings containing conversations in Vietnamese played to the court. Using detailed notes, the researcher then compared what he had heard and documented with the corresponding translated transcript in English which was read aloud to the court by an appointed court official.

The researcher documented examples of errors detected in the translated transcripts which are presented in the Results (cf. Section 5). The findings from Tier 1 established a platform from which to design other methods of data collection which were applied in Tiers 2, 3, and 4. As the findings from Tiers 2, 3, and 4 also contribute to the Discussion (cf. Section 6), a brief description of each method follows (cf. Gilbert, 2014).

Evidence of significant errors contained in translated transcripts was detected during observation of trials at Tier 1. Examples of discourse analysis conducted during Tier 1 Case Study 1 are provided (cf. Section 5). The data collection method used in Tier 2 was in the form of questionnaires and interviews. Key stakeholders provided valuable information concerning the preparation of translated transcripts. The sample populations engaged for data collection at this level included judicial officers of the Victorian County Court, barristers, court interpreters, community interpreters/translators who had previously been engaged by law enforcement agencies to conduct transcription tasks for evidentiary purposes. Participants with appropriate skills, knowledge and experience relating to the production and use of translated transcripts from LOTE were selected based on their ability to provide relevant information. A focused and targeted approach was necessary due to the small number of suitable participants who were able to provide information about the specialist areas of transcription for law enforcement, legal processes, intelligence, court interpreting and transcription for military purposes. Participants were issued with written information explaining how the information they provided would be analysed and presented. Closed, multi-choice questions were used in the questionnaires (cf. Gilbert, 2014, Appendices F to I). Questionnaires preceded a second level of data collection in the form of in-depth interviews. Participants were advised that they could withdraw from the process at any point if they wished to do so. The interviews and questionnaires were designed to collect information relating to 1) evidence of language capability deficiencies in the non-traditional security sector of law enforcement; and 2) how language capability relied upon in the military environment for transcription tasks compares with the principles and methods applied in the law enforcement working environment.

Tier 3 involved the collection of court transcripts and discourse analysis of the collected data from three criminal trials involving serious and organised crime specifically related to illicit-drug activity. Each trial was categorised as a separate case study. The Victorian Government Registration Service provided access to court transcripts that were used to triangulate the data collected in Tiers 1 and 2. The Australasian Legal Information Institute (AUSTLII at austlii.edu.au) provided information for Tier 4. Four appealed cases were analysed and a keyword search on “code words” was conducted. The four case reports recorded details of drug-related trials. Translated transcripts had been admitted as evidence in the four trials containing alleged drug-related code words. The cases selected were heard in the Victorian Supreme Court of Appeal and the New South Wales Criminal Court of Appeal. This data collection method and subsequent analysis revealed the approach the courts take to allowing or disallowing evidence proffered by expert witnesses relating to the content of translated transcripts. The four cases reflected contention in relation to the alleged meaning of drug-related code words.

A systematic method of triangulating the data was used to process the data provided by participants. Data saturation was achieved to the point where no new categories were identified. Commenting on discourse analysis, [Wood and Kroger (2000), 81] emphasise the importance of having sufficient data to arrive at a reliable and well-grounded conclusion regardless of whether data saturation has been achieved. The authors find that when considering the data collected for discourse analysts “bigger is not necessarily better.” Due to the specialised areas under investigation in this study, enough data were collected to establish evidence of deficiencies in language capability relied upon by law enforcement for evidentiary purposes, specifically in relation to alleged illicit-drug activity.

5 Results

Significant distortions of meaning were detected in translated transcripts across three separate trials. Each trial represents a case study for the purposes of this research. Translated transcripts from intercepted telephone conversations and listening device recordings were proffered as evidence in the three Vietnamese drug-related trials. Court transcripts containing expert opinion evidence proffered by police officers concerning the alleged meaning of drug-related code words were also analysed.

Discourse analysis of the recorded Vietnamese conversations revealed that the word “thingy” had been incorrectly used in the English transcripts and was not used by the accused as a code word for drugs. Rather, the word “thingy” appeared in the English transcripts instead of using optimally appropriate anaphoric and exophoric reference words such as “it,” “that” and “there.” Further evidence confirmed that the word “thingy” was misused as a code word for drugs among Vietnamese interpreters and translators working for law enforcement agencies. During one of the case studies, a translator responsible for producing a translated transcript containing numerous references to the word “thingy” was called to give evidence in court. The translator giving evidence stated that interpreters and translators working on law enforcement drug-related operations routinely use the word “thingy” when they were unsure of what was being referred to in intercepted conversations. The use of “thingy” and other phenomena identified in the analysis of translated transcriptions from the case studies in this research are presented below.

5.1 Case Study 1

The trial was held in the County Court of Victoria. The accused person was being tried for allegedly having imported a commercial quantity of heroin and had been charged with drug-trafficking offences. Translated transcripts of conversations held in Vietnamese between the accused and other persons were presented as evidence. The translated transcripts were produced by a community translator under contract to a law enforcement agency. Police used methods of telephone interception and covertly placed listening devices to obtain the audio recordings. The brief of evidence presented by the Prosecution in this case also included other forms of evidence such as expert witness testimony, documents, witness statements, and various items. Vietnamese court interpreters assisted the court and interpreted for the accused when the accused gave evidence as a witness in his own defence.

The court played the intercepted audio recordings of conversations in Vietnamese aloud during the trial. This was necessary because the accused was giving evidence. It was therefore necessary that a translated transcript in English of the intercepted recordings in Vietnamese was read to the court so that the jury and court officials could understand what was allegedly contained in the recordings. The format established by the court for examination and cross-examination of the witness was implemented as follows:

• Counsel draws reference to an audio recording of utterances related to the line of questioning during examination or cross-examination of the accused.

• A court interpreter advises the accused that an audio recording is about to commence.

• The audio recording in Vietnamese is played to the court.

• The translated transcript in English is then read to the court by an independent court official.

• Counsel continues with the line of questioning with reference to the recorded conversations.

• The court interpreter interprets Counsels’ questions from English to Vietnamese for the witness.

• The witness replies in Vietnamese.

• The court interpreter interprets the witness’ response from Vietnamese into English for the court.

This method was implemented to enable all present in the court to understand the evidence and legal proceedings in English and Vietnamese.

Problems concerning the translated transcripts were observed on the first day of the trial. The field researcher compared the audio recordings of Vietnamese conversations played to the court with the translated transcript read to the court in English. Significant errors of distortion, omission and unjustified additions were identified in the translated transcripts that contained numerous serious English grammatical errors. In relation to “correctness” of translating evidentiary documents, [Darwish (2012), 66], states that “a grammatical mistake that disguises itself as another correct grammatical form may not be detected as such and may cause interference with the original intents of the message.” It became apparent that this type of translator interference was evident in the translated transcripts presented at the trial.

A Victoria police officer gave evidence as an expert witness during the trial. The officer proffered expert opinion evidence explaining the meaning of alleged code words and jargon as they appeared in the translated transcripts. The researcher observed that poor lexical choices and misinterpretations contained in the translated transcript were further interpreted by the police officer for the court. The police officer gave evidence that the words “thingy,” “gear” and other words as they appeared in some segments of the translated transcript were references to heroin. Words alleged to be either code words or jargon became the focus of the study. It was noted that the word “thingy” as it appeared with the context of the translated transcript does not have a direct lexical equivalent in Vietnamese. The Vietnamese word “ấy” had been frequently translated as “thingy.” The Vietnamese word “ấy” is an exophoric or anaphoric reference word meaning this, it, or that. In some contexts, it may also be used to refer to a third person. However, the word had been poorly translated as the English word “thingy.” This mistranslation resulted in large sections of the translated transcript containing non-sensical English.

Further errors and inconsistencies were identified in the translated transcripts. These errors adversely affected communication between the witness and court officials causing significant delays and confusion. The only persons who were aware of significant errors contained in the translated transcript were the court interpreters present in the courtroom and the field researcher. This is because they were proficient in both languages. It is assessed that most errors contained in the translated transcripts remained undetected by the judge, jury and the rest of the court. Some areas of the translated transcript were challenged by the Defence.

Observations of trial proceedings indicated that:

• significant errors appeared throughout the translated transcript

• a further level of interpretation of what was contained in the translated transcript was applied when the court interpreter remedied mistakes contained in extracts of the translated transcripts cited by counsel during examination of the witness

• court interpreters did not voluntarily draw the court’s attention to errors contained in the translated transcript

• legal argument transpired about the meaning of utterances contained in the translated transcripts.

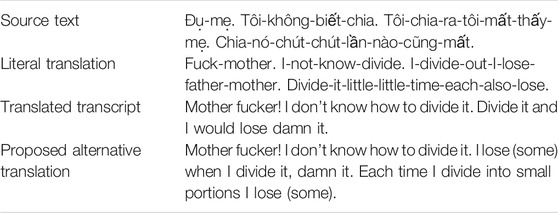

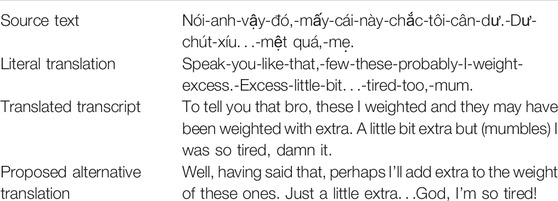

The researcher recorded notes during observation of this trial for subsequent discourse analysis of selected utterances heard in Vietnamese when audio recordings were played to the court. The audio recordings in Vietnamese were transcribed into written Vietnamese and then translated into English. The examples below contain grammar analysis of the translated transcript extracts revealing significant errors of translator interference. The following five utterances are part of a conversation intercepted by a covertly placed listening device. The translated transcript was presented as evidence in court. The Prosecution alleged that the intercepted conversation was held between two persons in a room engaged in the act of dividing heroin for subsequent distribution. The audio recording has been transcribed from the intercepted Vietnamese speech and is labelled “Source text.” A word-for-word literal translation from Vietnamese to English is then provided. This is followed by the corresponding translated transcript that was read to the court so that the judge and jury may make sense of the intercepted conversation in Vietnamese. Finally, a proposed alternative translation produced by the field researcher in consultation with a professional Vietnamese court interpreter of 25 years’ experience is provided. A critical analysis of the selected utterances is then provided to help the reader understand where the distortion of meaning and/or omission occurs. It is noted that a transcript of the original audio recording in Vietnamese is not provided to the Court. Only the original audio recording and a translated transcript in English are made available to the Court as evidence.

The following data (utterances one through five) are reproduced from Gilbert, 2014 (cf. Gilbert 2017).

1) Utterance One

There is an omission in the translated transcript. The final statement “Each time I divide into small portions I lose (some)” does not appear in the translated transcript. This is assessed to be a serious error as it adversely affects the element of textual cohesion when considered within context of the utterances that follow.

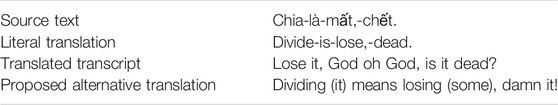

2) Utterance Two

A statement and an idiomatic exclamation appear in the source text. The audio recording did not contain any question related to something or someone being dead as it appears in the translated transcript. The literal meaning of the Vietnamese idiomatic expression “chết” is “dead” in English. However, in the above context, the expression “chết” is used to denote frustration and can be optimally translated idiomatically as “damn it!” as shown above. During the trial, the Prosecutor asked a non-English speaking witness to clarify, through a court interpreter, what or who was “dead.” This resulted in significant confusion and delay during the trial. The issue was not satisfactorily resolved, and the line of questioning was dropped after the issue was eventually clarified by a Vietnamese court interpreter. The translated transcript also contains the expression “God oh God.” This is assessed to be an unjustified addition. The audio recording did not contain an idiomatic expression that justifies the insertion of “God oh God.” This is assessed to be an example of interpreter interference.

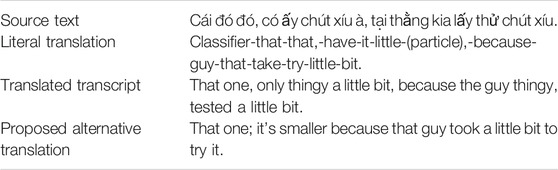

3) Utterance Three

The extract of the translated transcript above contains the word “thingy.” At this trial a police officer proffered expert opinion evidence that the word “thingy” was a reference to heroin. Appearance of the word “thingy” renders this segment of the translated transcript nonsensical. The choice to use the word is assessed as unjustified translator interference and renders the translation awkward, ambiguous and lacking coherence. It is assessed that the jury would increasingly rely upon the expert evidence provided by the police officer in this trial to understand this part of the transcript that contains the word “thingy.” This has significant implications for the defendant due to the inherent bias of the word being described by the police officer as code word for drugs. Significant distortion is contained in this part of the translated transcript. It is assessed that the word “thingy” in this context is highly unlikely to be a reference to heroin. Rather, it is an example of translator interference resulting in a poor translation.

4) Utterance Four

The word “thingy” appears again in the above extract. However, there is no Vietnamese word in the audio recording that be attributed to the word “thingy.” The use of the word “thingy” as it appears in this segment is assessed to be a significant mistranslation.

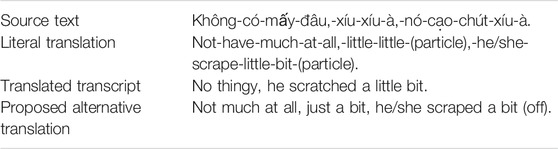

5) Utterance Five

The translated transcript contains an incorrect translation of the phrase “Nói anh vậy đó” which has been translated into English as “To tell you that bro.” The way this has been translated causes a break in textual cohesion with the previous utterance. An alternative and arguably more appropriate translation is “Well, having said that …” as shown in the proposed alternative translation above. Unjustifiable intervention by the translator is evidenced by using the word “bro” which is assessed to have originated from the translator having had access to extra-linguistic knowledge of the assumed context (in this case drug-related activity). This appears to have influenced the translator’s choice of register. The word “you” instead of the word “bro” is assessed to be more appropriate in this context noting its evidentiary value.

5.2 Additional Data Collection

In addition to the trial discussed in Case Study 1, two further drug-related trials were also observed in the County Court of Victoria. Telephone intercept and listening device recordings in the Vietnamese language formed part of the brief of evidence in both trials. The alleged accuracy of the contents of the telephone intercept transcript was challenged by the Defence. The translated transcripts were not read aloud to the court in these trials. Important to this research, the law enforcement translator who had transcribed the recorded conversations from Vietnamese into English was called to give evidence as an expert witness. The translator was questioned by counsel in relation to the alleged accuracy of the translated transcripts. The translator giving evidence admitted to making several errors contained in the translated transcripts of which were subsequently amended as appropriate. Notably, the person who gave evidence of having transcribed the audio recordings gave evidence that the person did not hold professional qualifications as a translator but held qualifications as a professional interpreter.

Errors contained in the translated transcripts resulted in significant delays. References to Vietnamese names throughout the trial caused confusion for the jury. The word “thingy” was frequently heard when extracts of the translated transcripts were referred to by counsel. In both trials the Prosecution alleged that the English word “thingy” as it appeared in the translated transcripts meant drugs.

In addition to qualitative interviews and quantitative analysis of court transcripts, the data collection strategy included a keyword search of “thingy” at the Australasian Legal Information Institute (AUSTLII) website. The database returned a range of trials where twenty-five references to the word “thingy” had been identified. Three references were associated with cases outside Australia. A breakdown of the types of cases where twenty-two references to “thingy” appears is as follows: sex offences (14), theft (2), drugs (3), and other (3). Two of the three drug-related cases contained references to the word “thingy” drawn from translated transcripts. The likelihood that the use of the word “thingy” by law enforcement translators is cross-jurisdictional was established. One of the drug-related cases was heard in the New South Wales Court of Criminal Appeal in 2010 and the other in the Victorian Supreme Court of Appeal 2011. In both trials the word “thingy” was contained in translated transcripts from Vietnamese derived from electronic surveillance. The results of the keyword search reveal that the word “thingy” forms part of a genre of language unique to the specialist field of producing Vietnamese drug-related translated transcripts.

5.3 Summary

Extracts from the translated transcript in Case Study 1 contain significant errors of translation due to unjustifiable translator intervention and poor word choices. The utterances lack coherence across the five samples as demonstrated when compared with the proposed alternative translations. An inconsistent approach seems to have been adopted by the translator. Forensic translation requires the translator to apply a consistent approach to ensure logical coherence at all levels of text. The sampled translations demonstrate a failure of cohesion at lexical, sentence and text levels. Nevertheless, prior to commencement of the trial at Case Study 1, the Prosecution and Defence counsels agreed that the translated transcript containing the above extracts was accurate.

6 Discussion

6.1 Implications of Language Deficiencies for the Judicial System

Significant errors contained in translated transcripts are compounded when monolingual police officers provide expert witness testimony concerning the meaning of alleged drug-related terms appearing in translated transcripts from LOTE. Evidence from a police officer to the effect that the word “thingy” is a reference to drugs increases the risk of the accused not receiving a fair trial.

The data samples provide evidence that the information relied upon by the jury is confusing and cannot stand alone without further interpretation being applied by another source of information. As the translated transcripts are assessed to be potentially misleading and confusing, it can be argued that the evidence might have been excluded in accordance with Sections 135 and 137 of the Evidence Act 2008 (Vic) (“the Act”) had the translated transcripts been properly assessed for reliability in terms of accuracy prior to commencement of the trial. At Section 137 of the Act, it is stated that “in a criminal proceeding, the court must refuse to admit evidence adduced by the prosecutor if its probative value is outweighed by the danger of unfair prejudice to the accused.” The court relies heavily upon the Defence and the Prosecution agreeing to the translated transcripts being accurate when balancing the “probative value” of the evidence against the “danger” of unfair prejudice.

Further evidence was obtained revealing that significant errors contained in translated transcripts are likely to go undetected at trial. A Defence barrister commented during interview that nobody really knows whether the translated transcripts are accurate or not. Translated transcripts are rarely assessed to determine accuracy due to either the unavailability of funding from Legal Aid or a failure to have them evaluated by an independent certified translator. During one of the case studies the judge described the difference between translation accuracy at word level and the meaning of utterances contained in the translated transcript. The rationale behind this reasoning provided an avenue by which the translated transcript could be admitted as “accurate” but only so far as it is accuracy applies to words on a page. The judge explained that, while the words on their own may be accurate translations, it is for the jury in its capacity as the trier of fact to decide what the words in the translated transcript mean within an alleged context. There is usually only one version of the translated transcript presented to the court to assist the jury. No alternative versions are considered other than those interpretations arising from legal argument over the content of the translated transcript. The important attribute of context within which a conversation takes place is critical in the translator’s decision-making process when deriving sense from intercepted utterances. Translators and interpreters with experience in producing translated transcripts stated during interviews that background and intelligence information about the covertly recorded conversations was not made available to them to assist with making sense of the intercepted utterances. They stated that this information was withheld from them for reasons of impartiality and to preserve the integrity of the evidence. Therefore, the translator producing the transcript applies a further level of interpretation when producing the transcript based on their personal knowledge, experience and assumptions of context. [Viaggio (1991), 37] emphasises that “[t]ranslation, as any other kind of communication, still succeeds as long as sense is conveyed, while it fails completely and inescapably if it is not.” It follows that the originator’s intended sense of the intercepted utterances is subject to distortion through the translation process when the translated transcripts are prepared for court. Further interpretation of what is contained in the translated transcript is applied by Counsel during the trial.

The nonsensical extracts from a translated transcript that form examples provided in this paper reveal what happens when sense is not adequately conveyed. The outcome is simply words on a page requiring further interpretation for the jury to understand what those words mean. The word “thingy” is a case in point. The data shows that inappropriate use of the word “thingy” is indicative that systemic mistranslations occur in translated transcripts, and they may remain undetected during court proceedings. This opens the door for expert opinion evidence proffered by police officers to interpret such terms for the jury in a realm of significant uncertainty. It is possible, if not probable, that the probative value of the translated transcripts would have been outweighed by the risk of prejudicial effect on the accused had the translated transcript been adequately evaluated for reliability prior to the commencement of trial. It follows that the probative value of the expert opinion evidence in this case may have also been significantly reduced had the significant errors contained in the translated transcripts been identified prior to the trial commencing. Judicial officers and barristers commented at interview that there is a tendency to expect that translated transcripts presented at trial are accurate. Interviews with Vietnamese court interpreters revealed that significant errors of translation are commonplace in translated transcripts from the Vietnamese language. They stated that they avoid alerting the court to errors contained in translated transcripts citing their ethical obligation to remain impartial forbids them from doing so. Interviews were held with Vietnamese translators and interpreters who had experience in producing translated transcripts for evidentiary purposes. They revealed that the word “thingy” had been misused in translated transcripts. They also commented that the word first appeared in Vietnamese drug-related cases in NSW and Victorian courts at least 14 years prior to the time of interview and reaffirmed that it is a term that appears to be peculiar to Vietnamese drug-related cases.

While collecting data during the observation phase of the research, a Vietnamese interpreter was subpoenaed to assist the court with disputed aspects of a translated transcript. Under cross-examination, the interpreter was asked to explain when the word “thingy” was used in translated transcripts. The interpreter stated:

Sometimes we have different Vietnamese words we use, but basically the appropriate way is when we don’t know for sure what that object is or are and when they use that word and we don’t know for sure, then I put the word “thingy,” because sometimes they will say, “ấy”—they just use the word “that one” or “cái.” It could mean anything so I just put the word “thingy” meaning that we are not so sure of what they are talking about.

The Prosecution had alleged that “thingy” was a code word for heroin. Translated transcripts across three Vietnamese drug-related trials contained numerous occurrences where the word appeared seemingly out of context. It was established that the word “thingy” is a cross-jurisdictional phenomenon frequently occurring in Vietnamese drug-related translated transcripts in NSW and Victorian criminal cases. A search of the AUSTLII database at the time of writing reveals that the word “thingy” appeared in a translated transcript presented as evidence at a Vietnamese drug-related trial in the County Court of Victoria in May 2017 in DPP v Agbayani (2017) VCC 723 (June 8, 2017). Again, the word appeared out of context but was not referred to in the court transcript as a code word for drugs.

The problematic misuse of the word “thingy” has been identified in another language. A Chinese interpreter with experience in producing drug-related translated transcripts who participated in the research stated that the word “thingy” was used in a drug-related translated transcript from Chinese. The interpreter explained that use of the word “thingy” came from advice provided by a Vietnamese interpreter who was a colleague of interviewee and was also working for the same law enforcement agency. It is evident that a genre of discourse specific to the specialist area of producing translated transcripts has been in existence for several years and that not only is it cross-jurisdictional, but it has also been used in translated transcripts from at least one other language than Vietnamese. The research has established that the problem of nonsensical English appearing in translated transcripts arises from the translator attempting to preserve the integrity of the evidence by applying accuracy at word level at the sacrifice of conveying sense.

6.2 The Police Expert Witness

Investigating police officers often proffer expert opinion evidence in relation to the alleged meaning of drug-related jargon and code words. It has been established that drug traffickers’ jargon is a specialised body of knowledge allowing police officers to give evidence as experts to explain drug-related terminology. In United States v Boissoneault, the court of appeal held that “experienced narcotics agents may explain the use and meaning of codes and jargon developed by drug dealers to camouflage their activities.” Police officers are rarely challenged in relation to the reliability of their expert opinion evidence as the aspect of determining reliability rests with the trier of fact. In Australia, Section 79(1) of the Uniform Evidence Act requires that expert opinion evidence is proffered by a person who has “specialised knowledge”; that the specialised knowledge is based on the person’s training, study or experience; and the opinion is “wholly or substantially” based on that specialised knowledge.

The research findings reveal a significant bias towards the Prosecution case as a result of inadequate translation quality control procedures. The High Court considered the issue of expert evidence in Dasreef Pty Ltd. v Hawchar with Heydon J3 stating:

Opinion evidence is a bridge between data in the form of primary evidence and a conclusion which cannot be reached without the application of expertise. The bridge cannot stand if the primary evidence end of it does not exist. The expert opinion is then only a misleading jumble, uselessly cluttering up the evidentiary scene.

The dangers of experts proffering their opinion without proper scrutiny of the primary data was discussed in In HG v The Queen (1999) HCA 2; (1999) 197 CLR 414 at [44] Gleeson CJ said:

Experts who venture “opinions,” (sometimes merely their own inference of fact), outside their field of specialised knowledge may invest those opinions with a spurious appearance of authority, and legitimate processes of fact-finding may be subverted.

When determining relevance of expert opinion evidence, it is argued that the monolingual police officer should be required to establish the reliability of their opinion when providing interpretations of terms appearing in translated transcripts alleged to be code words for drugs. On a technical point, the primary evidence comprises the sounds recorded on the audio file. Translated transcripts from LOTE derived from the audio files are termed secondary evidence and are presented to the jury with an appropriate direction delivered by the judge. Therefore, the reliability of expert opinion testimony is inextricably linked to the accuracy of the translated transcripts. This raises the prospect that words contained in translated transcripts may mean something other than what a police officer as an expert witness purports them to say. It follows that the notion of factual assumptions drawn from translated transcripts can be challenged on the grounds of reliability of any opinion expressed in relation to sense or intended meaning.

The reliability of expert opinion evidence proffered by police officers in relation to drug-related code words translated from a LOTE has been challenged in appeals cases. In the case of Pham, Van Diep; Tran John Xanvi v R the New South Wales Court of Criminal Appeal considered grounds of appeal relating to the conviction of the appellants found guilty of supplying prohibited drugs including heroin, cocaine and ice (crystalline methamphetamine). The first ground of appeal was that the trial judge erred in allowing a NSW police officer to proffer expert evidence.

At trial, the police officer testified to the meaning to alleged code words contained in translated transcripts of recorded conversations from intercepted telephone conversations in Vietnamese. There was no explicit reference to drugs made in any of the translated transcripts. The Court of Criminal Appeal reported that “[t]he Crown’s case was that when one appreciated the code was present one could interpret the conversations as ones relevant to the dealing in drugs in question.”

The police officer proffered evidence that the word “cabinet” is commonly used as a drug-related term referring to the prohibited drug ice. The officer relied upon his experience and a number of reference sources. The officer stated that his opinion was based on “a translation of a Vietnamese word which literally [led him] to believe the word cabinet is another word for fridge.” The police officer referring to his notes explained that “[t]he word “fridge” in Vietnamese is in my knowledge is made up of two words being To and Lun, now I don’t profess to have the tone marks or the pronunciation correct in those words.”

During cross-examination, the police officer stated that the information upon which he has provided an opinion is consistent with drug-related terminology relating to the drug ice or crystalline methamphetamine. The officer also gave evidence that the word “to” in isolation is consistent with references to the drug ice or crystalline methamphetamine and added that the words “to” and “to lun” are interchangeable. During cross-examination, the officer also stated that the words “old man” refer to heroin. He stated that his opinion was based on previous calls he had seen.

The police officer informed the court that he was unable to properly write or pronounce Vietnamese words. However, the officer’s expert opinion evidence was allowed and he provided expert opinion evidence on the meaning of individual Vietnamese words and their meanings when combined with other lexical units. From the information made available in the court report, the police officer relied heavily upon the discretion of the translator when making critical choices during the translation process. At trial, the police officer cited the word “to” (properly written as tủ) as being interchangeable with “to lun” (properly written as tủ lạnh). He stated that both Vietnamese terms are consistent with reference to the drug ice.

The word tủ forms part of many other words in Vietnamese relating to any box-shaped container. For example, a wardrobe in Vietnamese is a tủ aó and a safe is a tủ sắt. The term “cabinet” in English may well be drug jargon used to refer to the drug ice. However, what appears in the English transcript will depend on what lexical choices are made by the translator when translating the word tủ into English. The words “cabinet,” “container,” “box” or “trunk” are all acceptable translations. In Vietnamese, the words “fridge” and “refrigerator” are written and spoken the same way in the Vietnamese language. While the Vietnamese compound word tủ lạnh may be translated into English as either “fridge” or “refrigerator,” it is not possible to abbreviate the Vietnamese word so that one or the other component of the disyllabic word only means “fridge” instead of “refrigerator.” The Vietnamese word đồ is a further example of a Vietnamese word that is often skewed during translation to the advantage of the Prosecution. The word is often translated as “gear” in drug-related trials when optimally it means “stuff” or “things.” Police officers giving expert opinion evidence have referred to the word “gear” as being consistent with drug-related terminology. The weight of the evidence is arguably diminished if the translator translates the Vietnamese word đồ as “stuff” for inclusion in the translated transcript. The word “stuff” instead of “gear” would not provide a monolingual police officer the leverage the officer requires to inform the jury that “stuff” is consistent with drug-related terminology, whereas the word “gear” is most likely to go unchallenged. It has been clearly demonstrated that expert opinion evidence proffered by police officers hinges upon the choices the translator makes when producing the translated transcript. The key question is whether the monolingual police officer as expert witness is “wholly or substantially” basing their expert opinion on specialised knowledge, training, and experience or whether the expert opinion is a further interpretation based on their understanding of lexical choices made by a translator who produced the translated transcript.

In Nguyen v R the NSW Criminal Court of Appeal considered expert opinion evidence proffered by a NSW police officer who was a native speaker of Vietnamese. The officer gave his opinion relating to the meaning of drug-related code words. The police officer was reported to have had extensive experience listening to recordings of conversations about the supply of prohibited drugs and “had become extremely familiar with drug related terminology, drug related prices and the methods of operation of drug-dealers.” It was held that the police officer “could give evidence to the meaning of words and expressions recognised as argot of the drug trade.” However, the trial judge also stated that

… it is impermissible to give evidence of what a person means when he uses certain words and phrases, that is a witness cannot give evidence of what is in the mind of the person who is speaking or speculate as to what he is meaning.

The judge’s statement is interesting when considering that the translator who produces the translated transcript does so without knowing all there is to know about the context within which the intercepted conversation is taking place. The translator must speculate at some point in relation to the meaning of words and phrases he or she hears and the sense that the originator of the utterances intends to convey. The translator is compelled to speculate because he/she is not a party to the conversation but simply a witness to it. The translator produces a translated transcript in a context-deficient environment and therefore will need to speculate. Available extra-linguistic information such as intelligence support is withheld from the translator to maintain the integrity of the evidence relied upon by the Prosecution. Should the translator be provided with all background and intelligence information available, the Defence may argue that the law enforcement translator was primed through the provision of extrinsic information relating to drug-related activity under investigation. Translators and interpreters interviewed during the research cited this as a reason why translators apply a literal approach to translation when producing translated transcripts. As shown in this article, this results in awkward sentence structures and significant distortions of meaning. [Viaggio (1991), 32] clearly summarises the translator’s dilemma when producing translated transcripts while attempting to preserve evidentiary value:

Every single utterance can have countless senses. Sense is, basically, the result of the interaction between the semantic meaning of the utterance and the communication situation, which in turn is its only actualiser. Out of situation, and even within a linguistic context, any word, any clause, any sentence, any paragraph, and any speech may have a myriad of possible senses; in the specific situation—only one (which can include deliberate ambiguity). The translator ideally has to know all the relevant features of the situation unequivocally to make out sense.

The translator’s dilemma described above is arguably inescapable and can only be resolved through an agreed consistent approach to the task of producing translated transcripts. There will always remain reasonable doubt in relation to the accuracy of translated transcripts while context underpinning intercepted conversations is not made known to the translator responsible for producing them. Context is an integral part of translation and is based on assumptions of meaning. [Gutt (1998), 46] states that successful communication is predicated upon values of consistency and is context dependent. This is because the author of the source text has intentionally crafted the communication produced in a format that is optimally relevant to the intended audience. Without access to all available contextual information surrounding the intercepted utterances, the translator can only assume the contextual framework within which the conversation takes place between the author and intended recipient. The translator will therefore inevitably intervene during the translation process bringing their own understanding of reality to the translated transcript. The lexical choices made by translators when producing translated transcripts are likely to have a significant impact on the outcome of court decisions noting that a further layer of interpretation is usually provided by police officers as expert witnesses.

6.3 Causal Factors of Mistranslation

Analysis of courtroom interactions and court records indicates that errors in the translated transcripts of recorded conversations have the potential to undermine the integrity of evidence in drug-related cases. Causal factors attributed to these errors include the absence of a nationally recognised standard providing guidance for the production of translated transcripts for evidentiary purposes, inadequate interpreter/translator specialised training in producing translated transcripts, workplace influences, and inadequate quality control measures used to check translated transcripts for correctness and reliability prior to being presented as evidence in court. Systemic misuse of the word “thingy” by law enforcement translators of Vietnamese conversations is evidence of deficiencies in appropriate specialised training and skills recognition. Restricted access to essential background information providing context to the translator is also a contributing causal factor. Translators and interpreters referred to the transcriber’s dilemma as being one where they are required to produce an “accurate” translation in the absence of extra-linguistic information to assist them when determining context. This explains why translated transcripts often do not make sense as evidenced by the data used in this paper (cf. Section 5).

7 Conclusion

This paper provided evidence that translated transcripts presented in court frequently contain significant errors that distort evidence used to prosecute serious and organised crime. Key causal factors that adversely affect the reliability of translated transcripts were identified as deficiencies in areas of specialised training, skills recognition and workplace practices. The reliability of evidence supported by translated transcripts may be further diminished through expert witness testimony provided by police. Effective national policy-making is required to establish appropriate forensic translation training and skills recognition to meet national security objectives and to provide for a fair judicial system. The implications of deficiencies in Australia’s forensic translation capability increases the risk of innocent people being convicted and the guilty set free. It is a timely call for national policy-making concerning forensic translation.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by College Human Ethics Advisory Network, RMIT University. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author Contributions

DG devised the project and carried out the data collection and analysis. GH took responsibility for the ethical integrity of the project. DG took the lead in writing the manuscript and GH provided critical feedback and helped shape the research, analysis and manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the School of Graduate Research, RMIT University and the many research participants for their significant contributions that made this research possible.

Footnotes

1The collection of data in this research was approved by the College Human Ethics Advisory Network, RMIT University Approval number CHEAN A 0000015703-09/13 dated 7th November 2013

2Dr David Gilbert (First author)

3No relation to the second-named author

References

Agbayani, D. P. P. v. (2017). DVCC 723. Available at http://www.austlii.edu.au/cgi-bin/viewdoc/au/cases/vic/VCC/2017/723.html?context=1;query=agbayani%20;mask_path= (Accessed on: November 24, 2021).

Capus, N., and Griebel, C. (2021). The (In-)Visibility of Interpreters in Legal Wiretapping – A Case Study: How the Swiss Federal Court Clears or Thickens the Fog. Int. J. Lang. L. 10, 73–98. doi:10.14762/jll.2021.73

Darwish, A. (2012). Forensic Translation: An Introduction to Forensic Translation Analysis. Paterson Lakes, Victoria: Writescope.

Fishman, C. S. (2006). Recordings, Transcripts, and Translations as Evidence. Wash. L. Rev. 81, 473–523.

Fraser, H., Stevenson, B., and Marks, T. (2011). Interpretation of a Crisis Call: Persistence of a Primed Perception of a Disputed Utterance. Ijsll 18 (2), 261–292. doi:10.1558/ijsll.v18i2.261

Gilbert, D. (2017). “Electronic Surveillance and Systemic Deficiencies in Language Capability: Implications for Australia’s Courts and National Security,” in Proof in Modern Litigation: Evidence Law and Forensic Science Perspectives. Editors D. Caruso, and Z. Wang (Adelaide: Barr Smith Press), 127–128.

Gilbert, D. (2014). Electronic Surveillance and Systemic Deficiencies in Language Capability: Implications for Australia’s National Security. [dissertation]. [Melbourne, Vic]: RMIT University.

Gutt, E. (1998). “Pragmatic Aspects of Translation: Some Relevance-Theory,” in The Pragmatics of Translation. Editor L. Hickey (Great Britain: Cromwell Press Ltd).

Home Office (2021). Criminal Investigations: Use of Interpreters. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1007407/criminal-investigations-use-of-interpreters-v6.0-ext.pdf (Accessed September 16, 2021).

Laster, K., and Taylor, V. L. (1995). The Compromised “Conduit”: Conflicting Perceptions of Legal Interpreters. Criminology Aust. 6, 9–14.

Moreno, J. A. (2005). Strategies for Challenging Police Drug Jargon Testimony. Criminal Justice 20, 28–37.

Moreno, J. A. (2004). What Happens when Dirty Harry Becomes an (Expert) Witness for the Prosecution? Tulane L. Rev. 79, 1–55.

NAJIT (2009). NAJIT Position Paper: General Guidelines and Minimum Requirements for Transcript Translation in Any Legal Setting, Atlanta, GA: National Association of Judiciary Interpreters & Translators. Available at: https://najit.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Guidelines-and-Requirements-for-Transcription-Translation.pdf (Accessed September 18, 2021).

Nakane, I. (2009). The Myth of an “Invisible Mediator”: An Australian Case Study of English–Japanese Police Interpreting. Portal J. Multidisciplinary Int. Stud. 6 (1), 1–16. doi:10.5130/portal.v6i1.825

Nunn, S. (2010). “Wanna Still Nine-Hard?”: Exploring Mechanisms of Bias in the Translation and Interpretation of Wiretap Conversations. Surveill. Soc. 8, 28–42. doi:10.24908/ss.v8i1.3472

Queen, H. G. v. (1999). HCA 2; (1999) 197 CLR 414. Available at https://jade.io/article/68118 (Accessed on: November 24, 2021).

Tilley, S. A. (2003). “Challenging” Research Practices: Turning a Critical Lens on the Work of Transcription. Qual. Inq. 9, 750–773. doi:10.1177/1077800403255296

Viaggio, S. (1991). Contesting Peter Newmark. Rivista Internazionale di Tecnica della Traduzione 0, 27–58.

Keywords: translation, transcription, covert recordings, drug investigations, forensic linguistics, language policy, evidence, interpreting

Citation: Gilbert D and Heydon G (2021) Translated Transcripts From Covert Recordings Used for Evidence in Court: Issues of Reliability. Front. Commun. 6:779227. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2021.779227

Received: 18 September 2021; Accepted: 03 November 2021;

Published: 03 December 2021.

Edited by:

Emma Richardson, Aston University, United KingdomReviewed by:

Chuanyou Yuan, Guangdong University of Foreign Studies, ChinaVeronica Bonsignori, Foro Italico University of Rome, Italy

Copyright © 2021 Gilbert and Heydon. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Georgina Heydon, Z2VvcmdpbmEuaGV5ZG9uQHJtaXQuZWR1LmF1

David Gilbert

David Gilbert Georgina Heydon

Georgina Heydon