- 1Interdisciplinary Graduate School, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, Singapore

- 2School of Humanities, College of Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, Singapore

Singapore, a young nation with a colonial past from 1819, has seen drastic changes in the sociolinguistic landscape, which has left indelible marks on the Singapore society and the Singapore deaf community. The country has experienced many political and social transitions from British colonialism to attaining independence in 1965 and thereafter. Since independence, English-based bilingualism has been vigorously promoted as part of nation-building. While the roles of the multiple languages in use in Singapore feature prominently in the discourse on language planning, historical records show no mention of how these impacts on the deaf community. The first documented deaf person in archival documents is a Chinese deaf immigrant from Shanghai who established the first deaf school in Singapore in 1954 teaching Shanghainese Sign Language (SSL) and Mandarin. Since then, the Singapore deaf community has seen many shifts and transitions in education programming for deaf children, which has also been largely influenced by exogeneous factors such as trends in deaf education in the United States A pivotal change that has far-reaching impact on the deaf community today, is the introduction of Signing Exact English (SEE) in 1976. This was in keeping with the statal English-based bilingual narrative. The subsequent decision to replace SSL with SEE has dramatic consequences for the current members of the deaf community resulting in internal divisions and fractiousness with lasting implications for the cohesion of the community. This publication traces the origins of Singapore Sign Language (SgSL) by giving readers (and future scholars) a road map on key issues and moments in this history. Bi- and multi-lingualism in Singapore as well as external forces will also be discussed from a social and historical perspective, along with the interplay of different forms of language ideologies. All the different sign languages and sign systems as well as the written/spoken languages used in Singapore, interact and compete with as well as influence each other. There will be an exploration of how both internal factors (local language ecology) and external factors (international trends and developments in deaf education), impact on how members of the deaf community negotiate their deaf identities.

Introduction

The Singapore deaf community co-exists with the wider Singapore society. Therefore, language and identity issues in the Singapore deaf community are closely interrelated to and shaped by language and identity issues in the broader Singapore context. It is essential to get an insight into the multilingual ecology of Singapore and the interplay of language ideologies first, to understand the ecology of the deaf community. Language ideologies comprise people’s covert and overt thoughts, ideas, attitudes, and beliefs about languages and varieties in terms of the value assigned to them, whether they are perceived as superior or inferior, and the language practices they employ (Webster and Safar, 2020; Woolard, 2021). This publication details how bi-and multi-lingualism in Singapore give rise to language ideologies which influence both hearing and deaf Singaporeans’ interactions, communication, and evaluation of their own and others’ language practices in Singapore in two main related sections: 1) the linguistic ecology of multilingual Singapore society and 2) the linguistic ecology of the Singapore deaf community.

The Linguistic Ecology of Multilingual Singapore Society

According to Mallikarjun (2019), the linguistic landscape refers to a static picture of a place where its language features are visible while linguistic ecology refers to the dynamic relationships and changes that occur between languages in an environment. Riney (1998) details six different types of interrelated language shift phenomena which have occurred over the past several decades because of key historical events since British colonialism from 1819 to 1961 as well as Singapore’s language policy and planning initiatives. These language shifts include the following changes:

i. from Indian languages originally spoken by the Indians who were brought to Singapore by the British in the 1930s and 1940s as apprentice servants, to English and Malay,

ii. to Malay as a minority language when it was previously used as a lingua franca

iii. from Chinese dialects such as Hokkien, Teochew, Cantonese and so on originally spoken by the Chinese immigrants to Mandarin as a lingua franca among the Singaporean Chinese community

iv. to English having the status of a lingua franca and mother tongue when it was previously considered a mere ‘working language’

v. from non-standard forms of bilingualism to English-mother tongue bilingualism;

vi. in progressing to literacy and biliteracy from non-literacy and semi-literacy.

Judging by the census data in 2020 (Department of Statistics Singapore, 2021), these predictions have been largely borne out. In 1965, when Singapore achieved independence as a nation, the country was situated in a multilingual ecology and attempting to move away from the influence of colonialism. Countries in Southeast Asia such as Myanmar, Thailand and Laos promoted linguistic nationalism where language policy and planning and nation-building efforts demonstrated resistance against colonialism in the form of promoting a common national language, which are Burmese, Thai and Laotian respectively (Tan, 2021). Each of these countries have similar post-colonial stories as they all went through the process of deciding on a common national language whilst grappling with their newly minted identities, including how this negotiation was going to ensue between the colonial language and the local languages. Ng and Cavallaro (2019) compared post-colonial evolution in Hong Kong, Malaysia and Singapore and pointed out that despite the similarities in colonial history and ethnic composition, the Singapore trajectory is a unique one which saw dramatic transformations in the linguistic landscape and ecology in the last 50 years.

During the entire period of the British colonialism from 1819 to 1961, English was the language of administration in Singapore (Riney, 1998). The sociolinguistic landscape in Singapore has been widely discussed and the following is drawn from Ng and Cavallaro (2019); Ng et al. (2021) and Nah, et al. (2021). In the 1950s, Singapore designated English, Mandarin, Malay and Tamil as the official languages and implemented English as a lingua franca to encourage social cohesion and racial harmony among the Chinese, Malays and Indians, which were the three main ethnic groups in the country. English was perceived as a neutral language and effective for interethnic communication since it did not belong to any of the local speech communities and its use would not privilege one ethnic group over another and would promote equality (Tan, 2021). Furthermore, the Singapore government felt that English was necessary for pragmatic and economic reasons, especially for the country’s survival as a nation since it facilitated access to the wider world (Wee, 2003). This pragmatism, also referred to as linguistic instrumentalism, views language/s not just as integral to the maintenance of an individual’s cultural or ethnic identity, but also as commodifiable resources in a community because of its value and ability to achieve national goals. This philosophy is reflected in three key language campaigns: 1) the Bilingual Policy, 2) the Speak Mandarin Campaign, and 3) the Speak Good English Movement. These campaigns shape the sociolinguistic reality of Singapore today and the following sections will briefly outline how these campaigns eventually exert an influence on the local deaf community and their attitudes to language use.

Bilingual Policy

The English-mother tongue bilingual school policy adopted in 1966 gives bilingualism in Singapore a meaning of its own as the terms “first language”, “second language” and “mother tongue” are defined differently from those commonly seen in linguistics definitions (Saravanan, et al., 2007). Several authors have written about the impact of the bilingual policy post-independence (e.g., Ng et al., 2021; Mathews, et al., 2017; Saravanan, et al., 2007). The following is a brief discussion of the impact of the bilingual policy which requires English to be the first language of instruction in schools, with the other official languages labelled as “mother tongues” and acquired as second languages. The “mother tongues” were assigned according to ethnic background and are Mandarin, Bahasa Melayu, and Tamil for the Chinese, Malays and Indians respectively, regardless of what the speakers’ first languages are (Saravanan, et al., 2007). This association of mother tongues with ethnic backgrounds rather than the language spoken in the home means that the “mother tongues” studied at schools as second languages may not reflect the first language of the students. The mother tongues are seen to provide “cultural ballast” which are there to contain the complete dominance of English (Vaish, 2008).

According to Wee (2003), the concept of ‘linguistic instrumentalism’ justifies the existence and privileging of the use of the English language across all domains of Singapore society because it is viewed as a world language that facilitates greater access to economic progression, information, higher status and quality of life in society. He further argues that other languages are perceived as delaying such access or even when regarded as important, they are treated as preserving cultural heritage or “cultural repositories”. Therefore, English became a dominant language due to government official language policy, its widespread use by the media and the Speak Good English Movement in 2000 (Bolton and Ng, 2014; Tan 2014; Tang, 2018). Tan (2014) argues that since English is the lingua franca among different racial groups in Singapore, the state should assign it ‘mother tongue’ status, as not identifying it as such, opposes the actual language practices in Singapore. Consequently, the rising dominance of English across every domain in Singapore such as business, law and education, even discussed as early as the 1980s, has led to the decline of the use of mother tongues as well as other Chinese and Indian varieties. Members of the public have voiced their concerns that the prestige of English and its ubiquitous use have caused the standards of mother tongues to decline (TODAYonline, 2013).

The Speak Mandarin Campaign

In the early 1900s, the popularity of Chinese medium schools increased, and Mandarin Chinese was adopted as the standard language of instruction, thereby demoting other Chinese languages such as Hokkien, Teochew and Cantonese to vernaculars (Riney, 1998). By 1956, Mandarin Chinese already had a strong foothold in the Chinese community, especially in the domain of education, because of the establishment of Nanyang University in the same year that adopted Mandarin Chinese as a language of instruction. Ng et al. (2021) pointed out that despite the increasing influence and prestige of Mandarin Chinese in Singapore, many Singaporeans started to show a preference for English-medium education in the 1950s. This was due to its more promising job prospects as English-educated Singaporeans were earning higher incomes and had a higher employability rate compared to those who were Chinese-educated (Kuo, 1985). This caused a decline in student enrollment in non-English medium schools until 1987 when the last Chinese medium school closed (Abshire, 2011; Ho, 2016). In 1979, the ‘Speak Mandarin Campaign’ was introduced by the Singapore government to facilitate Singaporeans’ progress in learning Mandarin Chinese. As a result, many Singaporean Chinese have reported increasing the use of English and Mandarin in their homes as indicated by responses to census questionnaires in each succeeding decade (Liang, 2015). This has caused a significant decline in the use of Chinese regional varieties.

Singapore’s multiracial policy was to ensure that Mandarin, Malay and Tamil be accorded equal language statuses and economic value in order to uphold the nation’s principles of multiracial equality and egalitarianism (Wee, 2003; Schiffman, 2007). However, the acquisition of Mandarin has been promoted due to China’s rising economy in the global scene, thus leading to Mandarin becoming a popular choice of language even among non-Chinese who lobbied schools to give their children the option of studying it (Simpson, 2011). Said (2019) pointed out that there remains an imbalance that indicates a preference for Mandarin over Malay and Tamil, as reflected in the Singapore government’s top-down constitution processes and allocation of resources for mother tongue learning. Despite the active promotion of Mandarin Chinese as a lingua franca among Chinese Singaporeans, English still features more prominently in the discourse and continues to dominate the linguistic ecology of Singapore (Cavallaro et al., 2021). This observation is consolidated in the 2020 census, which shows a significant 6% decline in the use of Mandarin Chinese among Chinese Singaporeans (Cavallaro and Ng, 2021). This is the first downturn in Mandarin ascendency since 1979. At the same time, English use in the community has increased by 10%.

Malay has been retained as a national language or assigned “ceremonial” role that is visible on an international level for historical and policy reasons, while Tamil is deemed as politically insignificant (Kadakara, 2015). This was to establish some form of political safety net since Singapore is a small ethnically Chinese dominant nation surrounded by Malay and Muslim countries (Riney, 1998). The Malay community also comprises different dialects of the Malay language and other languages such as Javanese, Boyanese and Batak. Although the Malay community has been viewed as more successful conservators of their language in comparison with other ethnic communities, there is an apparent shift from Malay to the increasing use of English, especially among the younger generations and those from higher socioeconomic and education backgrounds (Mirvahedi and Cavallaro, 2019). This is confirmed in the 2020 census which indicates a dramatic 17.5% increment in the use of English by Singaporean Malays. The public have expressed skepticism of the government’s case for the economic value of Malay because Singaporeans in general are more impressed with the economic potential of China compared with its neighboring countries such as Malaysia, Indonesia and Brunei (Wee, 2003). As English is one of the working languages in Malaysia, it is possible for business transactions in the country to be accessible in English. However, it is imperative to know Mandarin to access similar economic opportunities in China. Therefore, this weakens the necessity of learning Malay. Malay, however, retains a more important position than Tamil because the Malays are demographically stronger and are symbolically seen as the indigenous occupants of Singapore.

The Indian community constitutes approximately 7% of the overall population of Singapore. It consists of a Tamil majority and speakers of northern Indian languages such as Bengali, Malayalam, Punjabi, and Hindi, as well as a small percentage who acquired Malay. In the 18th century, Tamil was introduced into Singapore by Indian immigrants from Tamil Nadu and only 3–4% of the population currently speak the language (Singapore Department of Statistics, 2000; Saravanan, et al., 2007; Singapore Association for the Deaf, 2020). This is essentially about half of the Indian population. As monolingual Tamil speakers were perceived as “uneducated”, the Tamil elite increasingly enrolled their children in English-medium schools instead of Tamil-medium schools until Tamil-medium education ceased completely in 1982 (Riney, 1998). There is also a lack of language maintenance of Tamil in the homes as those who are better educated tend not to use it as a home language (Schiffman, 2003). Between 1980 and 2000, the use of English dominated the homes of Indian families and increased, while the use of the Tamil language in homes dwindled (Saravanan, et al., 2007). The fact that Tamil is not necessary in business dealings and work contexts, accelerated its decline in use (Wee, 2003).

The Speak Good English Movement and the Singlish Debate

Due to the intermingling among the different ethnic groups over time and the different languages in contact with each other, a local vernacular called Singlish or Singapore Colloquial English, which interweaves English with Mandarin, Malay, Tamil and Hokkien words, and adopts Chinese grammatical structures, became a fixture in local communication within and across ethnic groups, mainly in informal settings and sometimes even in formal settings (Kramer-Dahl, 2003; Wee, 2013; Tan, 2015l; Cavallaro and Chin, 2014). As Singlish differs from the grammatical conventions of Singapore Standard English, the Singapore government introduced the Speak Good English Movement in 2000, to promote the use of Singapore Standard English or “proper English” and to discourage Singaporeans from using Singlish. This sparked off the “Singlish debate” which is dominated by the voice of the Singapore government (Bokhorst-Heng, 2005). The debate occurred between politicians who promoted standard English, “expert voices” of linguists and academics who claimed Singlish to be a marker of the Singaporean identity, and voices of the public in the press (Bokhorst-Heng, 2005; Tan, 2016). Cavallaro and Ng (2009) and Cavallaro, et al. (2014) found that sentiments of Singaporeans toward Singlish including those who support its use, remain deeply divided. On the one hand, they found overt positive affirmation for Singlish that is not supported by the matched-guise findings. As matched guise studies measure covert attitudes, they explained this schism in the findings by positing that Singaporeans may see the use of the colloquial variety as something that is more appropriate for private domains.

The findings that Singapore Colloquial English was rated lower in both status and solidarity traits in comparison to Singapore Standard English, contradicted preconceived perspectives and expectations of Singapore Colloquial English as a marker of strong solidarity in Singaporeans. This was a surprising result as this is in contrast with several similar studies which indicate that the speaker with the regional or colloquial accent or variety was rated more positively on solidarity traits than the speaker of the standard accent (Cheyne, 1970; Giles, 1971). These studies show that Singlish has a low status and is stigmatised in Singapore society while Singapore Standard English is associated with prestige and high status. Ng, et al. (2014) further attested this through a language accommodation study which found that speakers that had diverged to Singapore Standard English were given more positive ratings compared to those who used Singapore Colloquial English in a sales context. The Singaporean participants firmly prefer sales assistants to maintain the use of English even in situations when it is customary for shop assistants to accommodate to the language choice of the customers.

Singapore’s nation-building agenda is rife with debates surrounding language meanings and language practices, resulting in different perspectives on definitions of Singlish and which definitions are correct (Bokhorst-Heng, 2005). At the heart of the debates are the tensions resulting from “glocalism” that involve two distinct constructs of national language ideologies: “internationalism” versus “national identity”, representing different perspectives of how an ideal Singapore and citizenship is defined. The case of Singlish and the ideology of a standard language has resulted in intra-language discrimination, as evident by the varying perspectives of interlocutors in the Singlish debate where there is devaluation of the non-standard variety by one camp and the defense of Singapore Colloquial English by the other camp (Wee, 2005).

The three main ethnic groups—Chinese, Malay and Indians, have seen an increasing use of English over time, indicating a gradual move to homogeneous bilingualism or English-dominated bilingualism as evident by English-mother tongue repertoires of Singaporeans (Riney, 1998). This lends support to Tan’s (2021) argument that multilingualism in Singapore is a “myth”. She made an interesting interpretation of Singapore’s highly promoted bilingual policy and that multilingualism is actually a façade for a de jure monolingual Herderian language policy. The Herderian ideal aspires to maintain the “one nation, one language” philosophy or linguistic homogeneity (Bauman and Briggs, 2003). This is achieved through “hierarchical multilingualism” within the official languages as well as “controlled multilingualism” where the mother tongues function as “control languages” for the three main ethnic groups to discourage each ethnic community from using several languages. Therefore, the Singapore government’s intentions clash with how realities play out in language policy. The policy was ostensibly for societal multilingualism but not individual bilingualism as Prime Minister Lee (1984) stated in his speech at the opening of the Speak Mandarin Campaign on 21 September that:

“Few children can successfully master two languages plus a dialect. Indeed very few can speak two languages equally well. The reason why most societies are monolingual is simple: most human beings are equipped by nature to cope with only one language.

If we want our bilingual policy to succeed, we must lighten our children’s learning load by using Mandarin as the mother tongue in place of dialect. Studies show that students from Mandarin-speaking families consistently do better in their examinations than those from dialect-speaking homes. It could be the parents of such students are better educated. It must also be because they have no extra load of dialect words and phrases to carry” (p. 1).

The Linguistic Ecology of the Singapore Deaf Community

The above linguistic backdrop in the Singapore multilingual ecology set the stage and sent ripples through the Singapore deaf community, where a similar trend echoing what is happening elsewhere in Singapore is observed. Perceptions and attitudes among hearing Singaporeans towards the official languages have also infiltrated the Singapore deaf community and has influenced their language practices and ideologies toward SgSL, other spoken/sign languages and sign systems. These language ideologies have been influenced by factors described earlier such as language policy in the education system as well as nation-based initiatives such as linguistic instrumentalism and official national recognition of languages. External factors such as the influence of deaf education trends from the United States on deaf education in Singapore have also shaped language ideologies and language practices. Given the different statuses of the official languages in Singapore, it is hardly surprising that SgSL although considered by the Singapore Deaf community to be part of Singapore’s linguistic diversity, has yet to attain official recognition as a national sign language (Lee, 2016).

For a deeper insight into the language and identity issues confronting the deaf community to date, it is necessary to trace the origins and the evolutionary trajectory of SgSL. This necessitates a simultaneous exploration of the history of deaf education.

The Origins and Evolution of SgSL

Fontana, et al. (2017) indicate that sign language change in Italian Sign Language has been influenced by the individual background characteristics of signers, changes in how language is processed and understood, and shifting dynamics of groups who use the language as well as the contexts the languages are used in. Research into the etymology of American Sign Language (ASL) signs show how ASL originated from and is related to early French Sign Language (LSF) as well as to contemporary LSF (Supalla and Clark, 2015). SgSL seems to have followed a similar historical trajectory in its development to ASL. SgSL has its roots in Shanghainese Sign Language (SSL), which later came into contact with and was influenced by ASL, Signing Exact English (SEE), and locally developed signs (Lee, 2016). The deaf community has developed signs to represent local words such as “durian”, “rojak”, “Raffles”, “cheongsam”, “orchard road” and ‘satay (Goh, 1988). This includes Singlish words such as “kaypoh” (Chinese origin) which means “busybody”, and “alamak” (Malay), equivalent to “Oh my God!”.

The term “Singapore Sign Language” (SgSL) was officially coined in 2007 after being called “Native Sign Language” (NSL) for many years (Project Proposal- Singapore Sign Language (SgSL) Sign Bank and Community Engagement Project (Phase II): Development of Singapore Sign Language (SgSL) Sign Bank Project, 2014). Some deaf individuals perceived SEE as sign language that was “not natural” and phased it out with SgSL classes in 2015 at the Singapore Association for the Deaf (SADeaf). The first SgSL Level 1 and 2 classes commenced in April 2015 and have been running since then. The origins and evolution of SgSL are detailed in the next section, which highlights how significant events in the history of deaf education in Singapore resulted in language change.

The History of Deaf Education in Singapore

The First Deaf School in Singapore

A review of archival sources indicates that the histories of deaf people’s lives in Singapore prior to the early 1950s appear to be undocumented. Therefore, accounts of deaf people’s lives when Singapore was established as a British colony as well as during the Japanese occupation of Singapore during World War II (WWII) seem to have been lost or ignored. Based on published and unpublished archival sources, the historical evolution of SgSL has spanned almost 7 decades since the inception of the Singapore Chinese Sign School in the 1950s by Peng Tsu Ying. The following biographical information about Peng is drawn mainly from (Argila 1975; Argila 1976).

Peng became deaf when he was 5 years old. His parents brought him to Hong Kong and enrolled him in the Hong Kong School for the Deaf which was an oral school but allowed the use of sign language during and outside of school hours. During the Japanese invasion of Hong Kong in Dec 1941, Peng managed to return to Shanghai in a Japanese cargo ship. When he arrived in Shanghai, he attended Chung Wah School for the Deaf for his secondary education.

After WWII (1948), Peng moved to Singapore with his family. He was not able to locate any deaf people, which prompted him to put up an advertisement in the Chinese newspaper advertising educational opportunities for deaf children. Many parents with deaf children contacted him to teach their children privately. As there was no deaf school in Singapore at that time, Peng taught from his parents’ home.

Peng’s classes indicated the advent of deaf education in Singapore and a new life for generations of deaf children. In 1954, Peng and his deaf wife, established the first deaf school in Singapore and named it the Singapore Chinese Sign School for the Deaf. They utilized the techniques and the sign languages they acquired in Hong Kong and Shanghai. The languages used as the medium of instruction in the school was SSL and written Chinese. In 1953, Mrs E. M. Goulden, a British lady, started an oral class that had nine deaf children. This led to the establishment of the Singapore Oral School for the Deaf where English was adopted as the medium of instruction (Lim, 1977).

In 1963, The Singapore Chinese Sign School for the Deaf merged with the Singapore Oral School for the Deaf (Singapore School for the Deaf 50th Anniversary Celebration 1963–2013, 2013). It was renamed the Singapore School for the Deaf, which had an oral section and a sign section.

Other Deaf Schools Established in the 1950s

In 1956, the Canossian School for the Deaf was established by two Italian nuns to teach hearing impaired children English via oral methods (Lim n.d; Canossian School, 2020). It also used the Total Communication philosophy for a period starting around the 1970s before gradually preparing to transition to oralism between 1986 to 1988 (Canossian School for the Hearing Impaired, 1993). The school switched completely to a full oral approach by 1994 (Ho, personal communication, 2021).

In 1957, the Singapore Deaf and Dumb Art Institution was founded by Joseph Koo Ming Kang, a deaf man, who had moved to Singapore from Shanghai (Deaf and Hard of Hearing Federation Singapore, 2016). He had acquired his craft at the Deaf and Dumb Art School in Shanghai. At the Singapore Deaf and Dumb Art Institution, painting classes were conducted from Mondays to Thursdays, while Fridays were allocated to teaching Chinese writing and SSL. The institution closed in 1982 (Teo, personal communication, 2021).

The Advent of the Total Communication Philosophy and the Spread of SEE

The history of Deaf education, language and communication modes in Singapore seem to follow closely the shifting trends in Deaf education in the United States . The developments that occurred in the United States spread to Singapore about a decade or more later. The introduction of Signing Exact English-II (SEE-II) courses at Gallaudet College in Washington DC were influenced by trends in Deaf education in the United States in the 1960s that were started by deaf individuals (Holcomb, 2014). A new approach called Total Communication (TC) by Roy Kay Holcomb known as the father of TC, had started to spread in 1968 because a full oralism approach used in deaf schools was not always working (Holcomb, 2014). At that time, the TC philosophy was perceived to be child-centered and aimed to cater to the individual communication needs of the child and how he or she learned best. This could include a combination of speaking, hearing, signing, fingerspelling, reading, writing, drawing or any other strategies for communication that made information accessible to deaf children and catered to their individual learning style. According to Tevenal and Villanueva (2009), the term TC became interchangeable with simultaneous communication (SimCom), which refers to the teaching method of producing a sign for every single word in a spoken utterance.

Around the same period that TC was introduced, a few versions of Manually Coded English such as Seeing Essential English I (SEE-I) by David Anthony and Signing Exact English II (SEE-II) by Gerilee Gutason were created with the objective of improving deaf children’s literacy skills by making English visible on the hands. (Coryell and Holcomb, 1997; Zak, 2005). Both these sign systems incorporate the grammatical markers of English such as articles, determiners, auxiliary verbs and conjunctions, visually where every single word in a sentence is signed. It provides a visual representation of English grammatical markers as it was believed to enable Deaf children to acquire English better (Zak, 2005). The difference between SEE-I and SEE-II is very slight–SEE-II has ASL signs for compound words such as butterfly while SEE-I has two separate signs for the individual words in compound words. “SEE-I and SEE-II are different as “SEE-I utilizes signs for all morphemes (prefixes, roots, and suffixes) and some are further divided (e.g., the word “motor” is signed with two signs)” whereas in “SEE-II each English word is signed differently, and those words for which there are no signs are fingerspelled” (Luetke-Stahlman, and Milburn, 1996, p. 30). For some words in the past tense, the sign for the free morpheme for REACH or NICE is produced first and the bound morpheme or suffix markers “–ed” or–ly respectively is fingerspelled and added at the end of the free morpheme. Later on, the TC philosophy, SEE-I and SEE-II spread to other parts of the world.

According to Moriarty (2020), the proliferation of ASL signs, particularly in Indonesia and Cambodia, was caused by key historical events and sign language ideologies through deaf education projects, international development initiatives and tourism. In Indonesia, the TC philosophy was adopted and focused on spoken Indonesian and accompanying signs from Signed Indonesian (Branson and Miller, 2004). Signed Indonesian comprises a set of frozen signs including signs for suffixes and prefixes that resembles the written and formal conventions of the language and is devoid of the fluidity and flexibility that natural sign languages possess. The implementation of similar colonial methods incorporating TC and ASL/SEE in deaf education which displaced indigenous sign languages are also evident in other global south countries such as Trinidad and Tobago as well as Guyana (Ali, et al., 2021). In Singapore, there is a similar historical trajectory of ASL/SEE-II colonialism via deaf education initiatives.

The TC philosophy and SEE was brought to the Singapore School for the Deaf by Lim Chin Heng, a former student at the Singapore Chinese Sign School for the Deaf and who studied at Gallaudet College in Washington DC in the 1970s. The following biographical information about Lim Chin Heng is drawn mainly from Integrator (1995), Tiger (2008), Yeow (1995), Lim (1977), and Parsons (2005).

Lim was enrolled in the Singapore Chinese Sign School for the Deaf in 1955 and graduated from the school in 1965. When Lim completed his primary education in 1965, which was the year Singapore attained its independence, there was no secondary school for the deaf and none of the regular schools accepted any deaf students due to lack of appropriate resources to cater to their individualized needs. Consequently, Lim’s family sent him to the American School for the Deaf to pursue his high school education. Upon graduation, Lim went to Gallaudet College in Washington DC where he earned a degree in mathematics (1970–1975) and a master’s degree in education (1979–1981). He had full access to and participated actively in social, cultural and sporting activities while at Gallaudet College. During this time, he developed leadership skills and a desire to advocate for deaf people in Singapore.

In 1974, Lim volunteered at the Singapore School for the Deaf and SADeaf during his summer holidays. During this time, he decided to give up his plans to settle in the United States and resolved to return home for good. Upon his return to Singapore in the mid-1970s, Lim started as a volunteer tutor at the Singapore School for the Deaf upon Peng’s request due to a shortage of teachers at the school. After seeing evident progress in his students, he became motivated to become a full-time teacher for the deaf and returned to Gallaudet College to get his master’s degree in education.

Since young, Lim used ‘natural’ signs from SSL that he acquired from interaction with his peers at the Singapore Chinese Sign School for the Deaf before he went to the United States (Tiger, 2008) He claimed that it was an eye-opener for him when he saw students at Gallaudet using the Simultaneous Method to communicate. From his perspective, it was intelligible and the most effective way to learn English. He took up a course in SEE-II during his graduate education course at Gallaudet College and learned that fingerspelling after signing each word was an efficient way of reinforcing letters of the alphabet that were not visible solely by lipreading.

Deaf students at the Singapore School for the Deaf who were taught via the oral method or SSL, were struggling and not doing well in the Primary School Leaving Examinations (PSLE). The older deaf students appeared to perform better academically after Lim introduced American signs, the TC method and SEE-II as these methods helped them to comprehend their classes better. Lim attempted to convince some teachers of the effectiveness of this method, but they did not believe his claims initially.

One deaf adult suggested tracking the deaf children’s progress in English, Mathematics and Science to prove that TC was the best way to educate deaf children. A group of deaf adults voted in favor of TC being the best method for educating deaf children. They passed the SEE measure with government acclaim. From 1976, the whole school adopted the TC approach in alignment with the SADeaf’s official policy (Chua, 1990). When TC was fully implemented at the school, the oral section was renamed the “English section” while the sign section was renamed the “Chinese section” (Lim, personal communication, 2021).

From several accounts (Singapore Disabled People’s Association, 1995), Lim was a dedicated and committed teacher. The students not only saw him as a tutor but also as a mentor and a role model. Lim was also serving as the Honorary Treasurer on the Board of Management of the Disabled People’s Association. Renowned for his significant contributions to the Singapore deaf community especially for introducing ASL, SEE, and the TC philosophy to Singapore in 1975, Lim was awarded the title of Outstanding Deaf Citizen for the year during SADeaf’s 40th anniversary in 1995.

Frances Parsons–World Traveller and Advocate of TC Philosophy in Different Countries

Frances Parsons, a deaf professor at Gallaudet College, set out on a 10-years trip around the world in 1971 to several countries to advocate for the use of the TC philosophy in Deaf education after visiting schools in South America (Traveler Says: Americans Are Spoiled, 1981; Parsons, 1976). The following biographical information about Parsons is drawn mainly from (Parsons, 1976; Reilly and McIntire, 1980; Parsons, 2005).

Parsons went to Argentina, Iran, South Korea, Thailand, Burma, India, Malaysia, the Philippines, Ethiopia, Kenya, Madagascar, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Singapore and so on. In 1976, Parsons, who was touted as the global ambassador of TC by that time, arrived in Singapore. Parsons described how oralism and lip-reading presented barriers to the development of deaf children in education and stated that:

“The solution to this problem is the use of structural signed language. For years oral-trained deaf children stop talking, verbally, the moment they leave the classroom and revert to gestures. These natural gestures, unlike structural signed language, have no grammar, syntax and tense. That retards mental and educational development. Since hand gestures are the natural expression of the deaf, a scientific controlled language form like structural signed language should be accepted and taught to ensure that the communication of the deaf has the same language structure of the hearing people. Concept gestures are very limited in contrast to proper structural signs. Structural signed language can be used with equal ease and understanding not only among the deaf but also between the deaf and the hearing” (Parsons, 1976, p. 3).

As aforementioned, changes to Deaf education in Singapore began in 1975 when Lim, introduced SEE-II and TC to the Singapore School for the Deaf after graduating from Gallaudet College. In 1976, Parsons was invited to train educators of the Deaf in Singapore how to use TC by demonstrating the combined method where sign and speech were used simultaneously. During the teachers’ meeting, Parsons compared “unstructured signs” (natural gestures) from SSL with SEE-II, perceived as structured signs that represented English grammar, tense and syntax, with the support of Mr Lee, an officer at SADeaf. Consequently, Peng decided to do away with SSL and implemented the use of SEE-II. Observations that the students were using what was perceived as “unstructured” signing constantly and had only a few hours of classes of reading and writing in Chinese at school, led to this decision. Therefore, the Singapore School for the Deaf began to incorporate SEE-II signs with spoken English in 1977 by fully implementing the TC approach and phased out the Chinese Sign Section by 1978 (Gertz and Boudreault, 2015). This move was also in conformity with the Singapore government’s implementation and objectives of an English-bilingual policy for education in 1966 (Ng et al., 2021).

Other Deaf Education Developments

The English-bilingual policy implemented prevailed throughout the 1960s until today. However, the Deaf community was not integrated into this planning. In 2019, the Ministry of Education extended the Compulsory Education Act to students with disabilities making it compulsory for them to attend special education schools (Teng and Goy, 2016). Therefore, prior to 2019, students with disabilities were exempted from compulsory education and they did not enjoy the same privileges of compulsory education afforded to non-disabled students. This constrained deaf Singaporeans’ access to language and ‘mother tongue’ acquisition, as well as interaction with the wider bilingual community.

As described earlier, deaf education in Singapore has undergone numerous changes since the merger of the Chinese Sign School for the Deaf and the oral school for the deaf. Later, other educational settings were established that adopted completely oral modes or integration programs. Cochlear implants were introduced to Singapore starting from the late 1980s onwards after it was invented in 1982 (Alexander Graham Bell Association for the Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing n. d.; Cochlear Ltd. 2016; Singapore General Hospital 2016). There were also mainstream secondary schools that enrolled deaf students and adopted the TC philosophy as well as others that adopted the oral-only approach. Some of the deaf children who went through the oral method of teaching, acquired SgSL later in life. Others also opted for mainstream schools with no additional teacher of the deaf support.

In 2017, the Singapore School for the Deaf closed due to dwindling enrollments (Teng, 2017). In 2018, Mayflower Primary School started enrolling deaf students. The school which is perceived as adopting a bilingual approach to deaf education provides an SgSL program in its mainstream curriculum (Ong, 2019). This is in alignment with the philosophy of the World Federation of the Deaf (2016) which advocates for bilingual education in national sign languages for deaf children, instead of sign systems. The Singapore Association for the Deaf (2018), who is an Ordinary member of the WFD, oversees the running of the bilingual program at Mayflower school. However, there remains a lack of linguistics research on SgSL to support the development of the bilingual program.

Akbar and Ng (2020) pointed out that the change from SEE to SgSL in deaf education settings in Singapore has resulted in deaf children indicating a preference to use SgSL over SEE. The parents accommodate their deaf children’s language choices but experience conflicting feelings concerning the use of SgSL due to inadequate support from the government and the school. They found that a popular opinion among hearing parents was the belief that SEE is superior to SgSL as they perceived SEE as a high language variety and SgSL as a “broken” form of English or a “lazy” manner to communicate.

All these developments in education have shaped deaf individuals’ identity formations, ideologies, and language practices. Additionally, the three key language campaigns that shape the Singapore multilingual ecology are intertwined with significant developments related to language policy in Deaf education. They are:

1. Bilingualism (1966)

i) English is promoted as a lingua franca across the different ethnic groups.

ii) “Mother tongues” to provide “cultural” ballast.

Singaporeans who are between 50 years old and above were born or living in the bilingual policy period.

2. Speak Mandarin Campaign (1979)

i) Promotes Mandarin Chinese as a lingua franca in the Singaporean Chinese community at the expense of the vernaculars.

Singaporeans who are below 50 years old were born during the Speak Mandarin Campaign period.

3. Speak Good English Campaign (2000)

i) Focus is on Singapore Standard English and prescription of Singlish (Cavallaro et al., 2021).

As this campaign is actively ongoing, all Singaporeans are affected by it and in particular, we can expect those who are 40 and below to be completely English dominated.

The corresponding profiles for deaf Singaporeans are as follows:

The majority of deaf Singaporeans between the ages of 15–24 years are more likely to have grown up oral with cochlear implants, with a small percentage who grew up signing as seen by the declining numbers of deaf students at the now defunct Singapore School for the Deaf over the years. Some who grew up acquiring spoken language acquired some SEE or SgSL later in life, after completing their secondary school education. Those who are between 25 and 40 years old are likely to constitute the majority of deaf Singaporeans who grew up oral and acquired signing later in life. The number of signers between 25 and 40 years old would be higher compared to the group aged 15–24 years old. For those 41–60 years old, the number of signers would be higher compared to the two younger age groups. As for those 61 and above, the number of signers would be higher compared to the three younger age groups. This is also the age group who learned SSL and Chinese at the Singapore School for the Deaf and experienced the change to SEE and English. Based on Tay’s (2016) observations, the number of deaf signers increase with age and the number of deaf people who were taught via the oral approach and who have cochlear implants increase with the younger generations as most of them either attended an oral deaf school or a mainstream school.

Webster and Safar (2020) pointed out that sign languages are not always passed on through generational transmission in the same way that spoken languages are, because majority of deaf children are born to hearing parents and do not have the opportunity to acquire the national sign language from birth. This impacts the issue of language ownership. In this regard, the concept of “native” user of the language differs for sign and spoken language users (Webster and Safar, 2020). Therefore, based on the profiles of deaf Singaporeans described earlier on, SgSL is an endangered language because it is not being passed down to the younger generations. Interactional dynamics in the Singapore Deaf community restricts opportunities to acquire the language because there is limited intermingling between the younger and older deaf people.

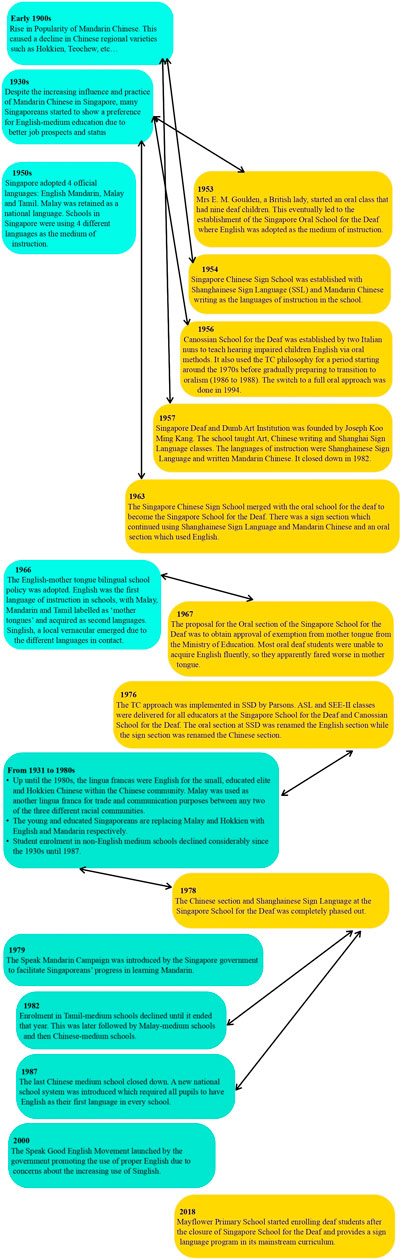

The following timeline summarises the information presented from the discussion thus far. Figure 1 shows the development of language policy and education in the broader Singapore context and the Singapore deaf community over the course of history.

FIGURE 1. Development of language policy and education in the broader Singapore context and the Singapore deaf community.

Language policy in deaf education was influenced by language policy initiatives in Singapore as well as external influences from deaf education in the United States. The rise in popularity of Mandarin Chinese medium schools in the 1900s in Singapore led to the decision to use SSL and written Chinese as the languages of instruction at the Singapore Chinese Sign School for the Deaf. In the 1930s, despite the increase in use of Mandarin Chinese, the language was still overshadowed by the more dominant English due to Singaporeans showing a preference for English-medium education.

The implementation of the English-mother tongue bilingual school policy eventually led to the exemption of mother tongue for deaf students at the Singapore School for the Deaf from November 1967 (Lim, personal communication, 2021). Deaf students in the oral section were struggling to acquire English and it was assumed for them that it was easier to focus on acquiring one language instead of two languages as mandated by the bilingual policy. This is in keeping with the prevalent erroneous assumption that individuals who have atypical developmental profile are not capable of learning more than one language (Cruz-Ferreira and Chin, 2010). The proposal by the Oral section of the Singapore School for the Deaf sought the Ministry of Education’s approval for the exemption from mother tongue for deaf students who were trained via the oral approach. Later on, the deaf students who were educated via the TC approach in the Sign section asked why they had to be exempted from mother tongue because they were able to acquire English successfully (Lim, personal communication, 2021). Therefore, deaf children do not have the agency to make decisions on whether to learn their mother tongue as it is a decision by the school and the parents.

From 1931 to 1980s, young and educated Singaporeans were increasingly shifting to the use of English and Mandarin. Enrollment in non-English medium schools declined considerably. In 1976, the TC philosophy was implemented in SSD which saw the introduction of SEE and English. This eventually led to the complete phasing out of the Chinese section in 1978, which was in alignment with the English-bilingual policy in promoting English as a first language. In 1982, enrollment in Tamil medium schools closed, followed by Malay medium schools (Riney, 1998). The last Chinese medium school shut its doors in 1987 and a new national school system was introduced that year which required all students have English as a first language in school. Therefore, there is a clear interrelation between events that occurred in the Singapore multilingual context and the Singapore Deaf Community.

The ‘Mother Tongue’ Issue in the Singapore Deaf Community

Although Singapore’s economic success can be attributed to the enactment of Singapore’s language policies and planning, there are also negative repercussions such as English-dominated bilingualism or more homogenous bilingualism (Riney, 1998), an increasing reduction in multilingualism, suppression of local creative expressions in English, and communicative dislocation in family units and among different generations of Singaporeans (Cavallaro et al., 2014). This dislocation is even more pronounced in the Singapore Deaf community. Loh (2021) describes SgSL as a “mother tongue orphan” as it cannot be associated with any specific ethnicity and “sits uncomfortably in the state’s language schema” because it does not have the same prestige as English.

Despite the implementation of the English-bilingual policy which requires all Singaporeans to learn English and a mother tongue according to ethnicity, deaf Singaporeans are exempted from their second language or mother tongue (Loh, 2021). Consequently, several deaf interviewees reported experiencing “a sense of alienation” from both their mother tongue and SgSL. However, the data also reflected that the SgSL situation might be changing as more deaf Singaporeans are also beginning to embrace SgSL as their language and as integral to their deaf identity. Tay’s (2018) observations reveal the contested status of SgSL, evident by the perpetual division in the Singapore Deaf community with regards to language practices. This debate is specifically between the use of SEE and SgSL and to a lesser degree, other forms of signing such as PSE. Not knowing their mother tongue has also impacted deaf Singaporeans’ access to the mediascape and religion which will be addressed in the next section.

The Singapore Deaf Community’s Lack of Access to the Mediascape and Religion

According to Vaish (2007), 66.7% of the Chinese children who participated in the study indicated their preference for English TV programs and movies and a quarter identified having a favourite programs in Mandarin. In follow-up studies, the Chinese children indicated that they enjoyed English movies with Mandarin subtitles or English shows dubbed in Mandarin as well as foreign cartoons dubbed in Mandarin that also had English subtitles. 76.4% of the Indian children who were surveyed stated their preference for English programs although 18% indicated that they had a favourite programs in Tamil. Findings for the Malay children were different compared to the Chinese and Indian children as the Malay children spent most of their TV time watching mainly English programs. Therefore, instead of only the dominance of English, the way in which languages are used in the ‘mediascape’ indicates that non-English languages and cultures are being consumed, and it is through movies, songs, and TV programs in the mother tongues that Singaporean children are provided access to wider networks and cultural capital (Vaish, 2007). At first glance, it seems that the Malay children may experience a similar sense of alienation from their mother tongue as deaf individuals based on their media consumption of English programs. However, they can still access English programs without any captions or even if the captions are in a language they do not know, because they are able to hear the audio.

In the case of deaf people, the sense of isolation is compounded further in the ‘mediascape’ through lack of access to programs in both their mother tongue and English. They cannot access English programs with Chinese subtitles if they did not take Mandarin Chinese as a mother tongue, nor English programs without any captions because they cannot hear the English audio. Although they can access local Chinese dramas and movies with English subtitles, they are not able to access Chinese programs with no captions or with Chinese captions. The same scenario also applies to Malay and Tamil children who are deaf. Therefore, deaf children in Singapore who have exemption from mother tongue do not enjoy the same level of access to TV programs and movies that hearing children do.

To exacerbate this exclusion, there is also limited access to live SgSL interpreters on the news. It is only provided on important occasions such as the May Day message. This is partly due to a shortage of interpreters in Singapore. SADeaf’s (2020/2021) annual report indicates that there are only six full time interpreters working at the association, which also provides training for interpreters. According to The Singapore Association for the Deaf (2020), the May Day message on April 30, 2020, by Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong, was the first to have sign language interpreters on the Channel 5 “Live” TV broadcast. Since November 30, 2012, when the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD) was ratified in Singapore, SADeaf has advocated for interpreters and subtitles to be provided in all national broadcast. The National Day Rally on August 26, 2012, featured live sign language interpreters for the first time, but there was no subtitling (The Straits Times, 2012). However, since 2006, the evening news on Channel 5 has real-time English subtitles daily (Infocomm Media Development Authority, 2021), except for the ‘live news report’ section, but no sign language interpreters. This shows an improvement in access to the news for the deaf but it is far from adequate. Although there is some visibility of SgSL interpreters in the news, this is a far cry from the access provisions by other countries in the region such as Malaysia where Bahasa Isyarat Malaysia (BIM) or Malaysian Sign Language interpreters interpret the Malay news on a regular basis and was already in place as far back as 1986 (Ang, 2020).

The lack of access to TV programs in SgSL and ethnic languages is not the only issue facing the deaf community. They also lack access to their mother tongue in the religious domains and are excluded from such discourse. Vaish (2008) found that although English overshadows Mandarin, Malay and Tamil in the education system, in the media and public sectors as well as in family and friendship networks, the mother tongues prevail over English where religion is concerned. For the Malay and Indian ethnic groups, the respective heritage or ethnic language is dominant for them in the religious domain as well as Arabic and Sanskrit (Vaish, 2008). However, for the Chinese, the use of English or Mandarin are predominant in Christianity and Buddhism respectively. Deaf Singaporeans from these ethnic groups are therefore, automatically excluded from participation in these religious activities due to their lack of access to the heritage languages, although a few local churches offer sign language interpreting for church services.

As aforementioned, deaf people feel a sense of alienation toward their mother tongue and SgSL which has limited their access to different aspects of life in Singapore society. This has also influenced the construction of their deaf identities and language practices which will be discussed in the following section.

Deaf Identities and Language Practices in the Singapore Deaf Community

Organizational restructuring at SADeaf along with deaf education trends have resulted in the emergence of the SgSL versus SEE debate, which has shaped deaf identities and language practices today among deaf Singaporeans (Tay, 2018). A native SSL deaf signer also revealed that those of his generation who experienced the change from SSL to SEE at the Singapore School for the Deaf still communicate among themselves privately in SSL (Neo, personal communication, 2019). However, during interactions with the wider deaf community, they switch to SgSL because they feel embarrassed to use SSL and view SgSL as superior. There is also evidence of language contact between SgSL and BIM as approximately 10 deaf Malaysians studied at the Singapore School for the Deaf and then returned to Malaysia (Chong, 2018).

Tay (2016) researched language and identity in the Singapore Deaf Community as part of a summer internship at SADeaf. She posed questions related to identity and language usage to 48 participants in the form of semi-structured interviews, of which 45 are Chinese, 2 are Malay and 1 of Indian descent. She also conducted participant observation at deaf events such as the Singapore Deaf Youth Camp. This led to discussions on identity descriptors and which language/s deaf Singaporeans supported in different contexts and the rationale behind their language choices. Some interviewees requested to have their interview in English where they typed their responses to questions on Google Hangouts while others gave consent to be filmed.

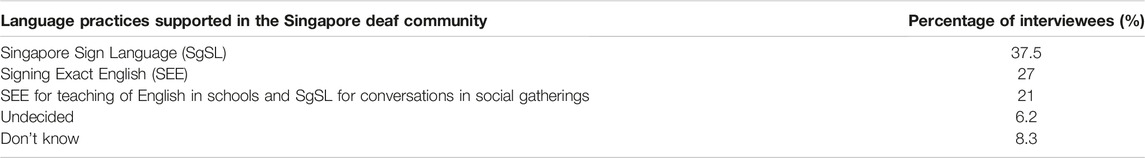

The participants identified with a range of identity descriptors. These include D/deaf, hard-of-hearing, hearing-impaired, deaf-mute, Persons with Hearing Loss (PWHL), and Non-Signing Hearing Impaired (NSHI). These labels are currently used in the discourse of the Singapore Deaf community as well as the wider Singapore society. In the press, the term “deaf and mute” was used as late as 2016, 2017 and 2020 (Chew, 2016; Tan, 2017; Chua, 2020). In 2016, the incident over the deaf cleaner being labelled as “deaf and mute” in The Straits Times (Chew, 2016), also sparked much agitation and discussion among the deaf community. Tay’s (2016) findings also revealed a varied support for language practices in the deaf community. As seen in Table 1, 37.5% of participants supported the use of SgSL, 27% supported SEE, 21% supported SEE for the teaching of English in schools and SgSL for conversations in social gatherings. The remaining 14.5% were either undecided or did not know. Based on observations, the forms of signing that some interviewees used can be perceived by the deaf community as more naturalistic or “SgSL-like” or “ASL-like” and others as more English-like or ‘SEE/Pidgin Signed English (PSE)-like’.

The interviewees consistently referred to SEE which is synonymous to SEE-II in the Singapore context. It is not apparent whether they knew the difference between SEE-II and SEE-I. Below are two commentaries containing excerpts from the interviews on deaf identity and language.

Excerpt 1.

Q: How would you identify yourself? As Deaf, hard-of-hearing or hearing impaired?

A: To be honest, I don’t really have a strong identity in the sense that I use different words to describe myself to different groups of people. To hearing people, I call myself hearing impaired in order for them to understand me quickly. As for deaf people, it depends on who. To the older deaf, I’ll say I’m hard of hearing even though I’m deaf because they understand it as deaf who can talk. To younger deaf, I’ll just say that I’m deaf. I don’t use the big D or the small d because they don’t understand the difference. To me, I feel that I have hearing difficulties which makes certain tasks more difficult for me but with the right support, I can do many things. So, I don’t have a fixed term to identify myself.

(Derrick (Pseudonym), CM062016, p. 57 Lines 1–9)

Excerpt 2.

Q: What is your perspective of SEE? Do you think it benefits Deaf children? Does it help with reading or writing skills?

A: Yes, SEE is a must! Sure, it benefits deaf children. As it enforces the sentence to be gestured out word by word in a proper flow. I see most of deafs normally writing in broken English so I believe SEE would help develop good writing skills.

Q: What about CSL1 or SgSL?

A: CSL-Chinese Sign Language?

Q: Yeah Chinese Sign Language. that’s what you grew up learning right?

A: Ah, that’s by no choice, I had to communicate with my mother and siblings. For SgSL, I am not familiar with it, hence can’t comment on it.

Q: Do you value CSL?

A: Not really, CSL is similar to Native Sign Language (NSL) (gesturing only important words), i.e. if you want to say you want to go to toilet, you just gesture “go toilet”.

(Jonathan (Pseudyonym), CM062016, p 53–54, Lines 17–34, Lines 1–2)

The above commentaries suggest that identity and language practices are fluid depending on context. Tay (2018) also found ideological parallels between Singlish and SgSL where both were perceived similarly and stigmatised as “broken English” and more appropriate for conversations between family and friends. “Broken English” is perceived as forms of English that do not conform with grammatical conventions of Singapore Standard English. Similar attitudes between Singapore Standard English (Wee, 2013) and SEE (Tay, 2018) are apparent, as both are considered ‘proper’ for use in education and more formal settings. Singapore Colloquial English and Singapore Standard English are used for different functions; Singlish is more commonly used when conversing with family and friends, while Singapore Standard English is used with educators, employers, government officials or foreigners (Echaniz, 2015). Therefore, perceptions of ideologies and features pertaining to Singlish and Singapore Standard English have influenced perceptions of ideologies and features in SgSL and SEE respectively.

Taking into account the different sign systems and sign/spoken languages used in the Singapore deaf community, findings reveal that the explanatory frameworks for relationships between language usage and identity markers were not consistent, or “fluid” across interviewees and situations (Tay, 2016). For example, SEE, ASL, SgSL and PSE were identified as forms of signing that Deaf people use and others as forms of signing that hard-of-hearing people use. The data shows a very active debate on which language should be used in the community. Interviewees do not share a common view of SgSL as the natural language of deaf people in Singapore, or even what constitutes SgSL or SEE. Some individuals view SgSL as an indication of “broken English,” incomplete, and/or view SEE as good for teaching English. The data also indicated that language and identity are linked in some expectable and surprising ways. As seen in the commentary, SSL is perceived as inferior to SgSL which means that the older generation of SSL users are stigmatised and the language is dying out in a similar fashion to local Chinese and Indian vernaculars. Although SgSL is understudied as a language and stigmatised in the same way as Singlish, SSL is stigmatised to a larger extent than SgSL. Amid the SgSL versus SEE debate, SSL is almost completely overlooked by the local deaf community.

Translanguaging in the Singapore Deaf Community

While the majority of Singaporeans are moving towards individual bilingualism, bi- and multi-lingualism in the Deaf community manifest differently. Sign language communities, characterised by sign multilingualism, have “cross-signing,” “sign-switching,” “sign-speaking,” and multimodality (Zeshan and Webster, 2019; Kusters et al., 2020). Some deaf individuals have SgSL and English as their main languages and/or a sign system like PSE, SEE or SimCom. Singaporean identity in deaf individuals is reflected in their similar ideologies toward Singlish and SgSL as well as SEE and Singapore Standard English. There are also deaf individuals who travel and know some International Sign (IS) and ASL. Therefore, ironically outside the regulatory machines of the state, Singaporean deaf signers are prolifically multilingual and this is reflected in the fluid occurrences of multiple systems and languages in their repertoire. De Meulder, et al. (2019) highlighted translanguaging practices in the context of deaf signers which focuses on sensorial accessibility and involve a wide range of semiotic resources for communication such as mouthing, speaking, signing, gesturing, writing, typing, fingerspelling, pointing, and use of technologies. The situation is in the Singapore Deaf community is very similar with additional layers of Singlish, Singapore Standard English, SEE, SgSL and other local languages.

Limitations of the Study

This study has some limitations. There were only two Malays and one Indian among the interviewees compared to 45 Chinese. Therefore, this research study has a lack of cultural representation and balance in views. Furthermore, only four educators whose contributions to deaf education and sign language evolution are mentioned. Lastly, there is a lack of historical documentation on the language situation of deaf people and their lived experiences prior to the early 1950s. Therefore, although there are existing historical sources and research on the broader Singapore context before the post-colonial period as far back as the early 1900s, the lack of historical evidence on deaf lives before the 1950s makes it challenging to draw accurate parallels between the deaf linguistic ecology and the hearing Singapore linguistic ecology in that period. A piece of the puzzle appears to be missing.

Discussion

As seen from the description in preceding sections, the Singapore government’s intention with regards to language policy initiatives was to promote multilingualism and recognise linguistic diversity. However, the adoption of hierarchical and controlled multilingualism promotes monolingualism in practice. This has resulted in more homogenous bilingualisms and a move toward monolingualism instead of the intended multilingualism. Schutter (2021) states that for advocates of linguistic minorities and language rights the Herderian ideal is both a blessing as well as a curse because it promotes linguistic diversity but is expressed as monism. Internal language planning and language attitudes in Singapore, significant events such as the promoting of bilingualism, the Speak Mandarin Campaign and the Speak Good English Campaign, as well as external forces in Deaf education, have shaped the language practices, ideologies and identities of the sign language community in Singapore.

There are similar trends in deaf education and ASL/SEE colonialism in global south countries that are reflected in the Singapore context. There is a nexus in the researchers’ findings on the preconceived attitudes and beliefs of the status of sign languages in the primary historical sources written by Peng, Lim, and Parsons, particularly regarding the supremacy of English which is evident by promoting the use of SEE/TC and ASL. Fontana, et al. (2017) stated that changes in language ideologies have resulted in novel linguistic practices. Changes in ideologies in the deaf community over time have shaped deaf Singaporeans’ language practices. Translanguaging practices in the Singapore deaf community have revealed that deaf Singaporeans are actually multilingual although the state’s definition of multilingualism indicates otherwise.

It remains unclear what the “mother tongue” of the deaf community is. Deaf people are left out of the mother tongue debate because they did not have the agency to decide for themselves regarding learning mother tongue and nor were they seriously considered in the process of deliberation. The same applies to SgSL as majority of deaf people are born to hearing parents who decide the oral route for them at birth with no exposure to SgSL until later in life. The choice of exemption from mother tongue indicates that English is perceived as more important and mother tongue as unimportant. The fact that deaf Singaporeans are using another mode, they are automatically considered to be linguistically challenged and are therefore not advised to learn another language or to be multilingual. Tay (2016) recalls when she asked an elderly deaf person what languages he knew, he only mentioned the spoken languages, not the sign languages despite him being fluent in more than one sign language. This indicates his belief that sign languages are not bonafide languages like spoken languages are. Therefore, there is a big question surrounding how language and culture is “inculcated” for deaf Singaporeans because they do not know their mother tongue and majority acquire SgSL later in life.

Considering the overall discussion, we can make the case that both hearing and deaf Singaporeans who co-exist in the Singapore multilingual ecology are “mother tongue orphans” in different ways. This is evident in the endangerment of their native tongues such as Chinese and Indian dialects as well as SSL and SgSL. We are same yet different. Snoddon and Weber (2021) posit that a bimodal bilingual approach to deaf education reaps interpersonal and cognitive benefits for deaf children because it provides them access to multilingual contexts, and this affords them the opportunity to innovate when using the multiplicity of languages and varieties in their communicative practices. They also highlight the shortcomings of language policy in deaf education across different countries which have deprived deaf children of access to a good quality sign language-based education. Through a plurilingualism and translanguaging lens, they challenge the oversimplistic notion of monolingualism, and point out the complications that accompany it especially for sign language bilingual programs. This is critical for the development of multilingual deaf identities and the active citizenship of every deaf Singaporean in accessing and participating in various facets of life in Singapore.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author Contributions

PT is the first author, corresponding author and the initiator of the project. She crafted the initial draft of the paper. In 2016, PT did a research project on language and identity during an internship at the Singapore Association for the Deaf. She also collected archival data about the history of Deaf linguistics in Singapore. The findings of the interviews PT conducted are documented and analysed in the paper.

BN is PT’s PhD supervisor at NTU and the second author. BN gave feedback on drafts pointing PT to relevant research for background reading on the Singapore linguistic ecology. She helped shape the discussion on multilingualism and linguistic ecology and provided feedback on the structuring of academic argument.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to all the deaf participants for participating in the research project on language and identity under the purview of the Singapore Association for the Deaf (SADeaf) in 2016. Thank you to SADeaf for granting permission to cite the data from the submitted research report. Some historical sources that are referenced were obtained from the Gallaudet University Archives. A special thank you to Jessica Mak for her guidance whilst doing my internship at SADeaf and to Lim Chin Heng for his generosity in sharing archival materials on Singapore deaf history. Thank you to Dr Audrey Cooper from Gallaudet University for her feedback on the research project conducted in 2016. Lastly, we are grateful to IGP (Interdisciplinary Graduate Programme) and the School of Humanities in Nanyang Technological University for the funding assistance to make this publication possible.

Footnotes

1*Note: During the interview, the interviewer posed the question regarding CSL which actually refers to SSL in Singapore. The interviewer should have used SSL instead when framing the question as SSL is more commonly used by the deaf instead of CSL. Therefore, it is an oversight on the researcher’s part. In this instance, CSL and SSL are used interchangeably in the Singapore context but there are many varieties of CSL in mainland China.

References

Akbar, M. A., and Ng, B. C. (2020). Family Language Policies of Families with Deaf Children in Singapore. Singapore: Nanyang Technological University.

Ali, K., Braithwaite, B., Dhanoolal, I., and Snoddon, K. (2021). Sign Language-Medium Education in the Global South. Deafness Edu. Int. 23 (3), 169–178. doi:10.1080/14643154.2021.1952507

Ang, M. V. (2020). Tan Lee Bee: Meet the Interpreter Known for Her Animated Sign Language on National TV. SAYS Available at: https://says.com/my/news/meet-the-sign-language-interpreter-famous-for-her-many-facial-expressions-on-national-tv.

Argila, C. A. (1975). An Interview with Peng Tsu Ying: Singapore’s ‘man for All Seasons’. The Deaf American, 9–11.

Argila, C. A. (1976). Deaf Around the World: Singapore -- the Tides of Change. The Deaf American, 3–5.

Bauman, R., and Briggs, C. L. (2003). Voices of Modernity: Language Ideologies and the Politics of Inequality. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bokhorst-Heng, W. D. (2005). Debating Singlish. Multilingua - J. Cross-Cultural Interlanguage Commun. 24 (3), 185–209. doi:10.1515/mult.2005.24.3.185

Bolton, K., and Ng, B. C. (2014). The Dynamics of Multilingualism in Contemporary Singapore. World Englishes 33 (3), 307–318. doi:10.1111/weng.12092

Branson, J., and Miller, D. (2004). The Cultural Construction of Linguistic Incompetence through Schooling: Deaf Education and the Transformation of the Linguistic Environment in Bali, Indonesia. Sign Lang. Stud. 5 (1), 6–38. doi:10.1353/sls.2004.0021

Canossian School for the Hearing Impaired (1993). 1993 Annual Report. Singapore: National Council of Social Services.

Cavallaro, F., and Chin, N. B. (2014). “2. Language in Singapore: From Multilingualism to English Plus,” in Challenging the Monolingual Mindset. Editors J. Hajek, and Y. Slaughter, 33–48. doi:10.21832/9781783092529-005

Cavallaro, F., and Chin, N. B. (2009). Between Status and Solidarity in Singapore. World Englishes 28 (2), 143–159. doi:10.1111/j.1467-971X.2009.01580.x

Cavallaro, F., and Ng, B. C. (2021). “Multilingual City: Singapore 2020 [conference Presentation],” in Multilingualism, Migration and the Multilingual City Symposium, Singapore and Exeter, United Kingdom. July 5-6.

Cavallaro, F., Ng, B. C., and Seilhamer, M. F. (2014). Singapore Colloquial English: Issues of Prestige and Identity. World Englishes 33 (3), 378–397. doi:10.1111/weng.12096

Cavallaro, F., Xin Elsie, T. Y., Wong, F., and Chin Ng, B. (2021). “Enculturalling” Multilingualism: Family Language Ecology and its Impact on Multilingualism. Int. Multilingual Res. J. 15 (2), 126–157. doi:10.1080/19313152.2020.1846833

Chew, H. M. (2016). Caught on Video: Woman Rants against ‘deaf and Mute’ Cleaner at Jem Foodcourt, the Straits Times. Available at: https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/caught-on-video-woman-rants-against-deaf-and-mute-cleaner-at-jem-foodcourt.

Cheyne, W. M. (1970). Stereotyped Reactions to Speakers with Scottish and English Regional Accents. Br. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 9, 77–79. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8260.1970.tb00642.x

Chin Ng, B., and Cavallaro, F. (2019). “3. Multilingualism in Southeast Asia: The Post-Colonial Language Stories of Hong Kong, Malaysia and Singapore,” in Multidisciplinary Perspectives on Multilingualism, the Fundamentals. Editors S. Montanari, and S. Quay (Berlin, Germany: De Gruyter), 27–50. doi:10.1515/9781501507984-003

Chong, V. Y. (2018). The Development of Malaysian Sign Language in Malaysia. J. Spec. Needs Edu. 8, 15–24.

Chua, A. (2020). Deaf and Mute Karang Guni Uncle’s home Decluttered Thanks to Charity, Was Given Food and Pillows. MSNEWS. Available at: https://mustsharenews.com/deaf-mute-karang-guni/.

Chua, T. T. (1990). Methods of Teaching Deaf Children in Singapore and Malaysia. Teach. Learn. 11 (2), 12–20.

Coryell, J., and Holcomb, T. K. (1997). The Use of Sign Language and Sign Systems in Facilitating the Language Acquisition and Communication of Deaf Students. Lshss 28, 384–394. doi:10.1044/0161-1461.2804.384

Cruz-Ferreira, M., and Chin, N. B. (2010). “Chapter 15 Assessing Multilingual Children in Multilingual Clinics,” in Multilingual Norms. Editor M. Cruz-Ferreira (New York: Peter Lang), 343–396.

Davis, J. E. (2011). Discourse Features of American Indian Sign Language. Academia.edu - Share Research. Available at: http://www.academia.edu/4058353/Discourse_Features_of_American_Indian_Sign_Language.

De Meulder, M., Kusters, A., Moriarty, E., and Murray, J. J. (2019). Describe, Don't Prescribe. The Practice and Politics of Translanguaging in the Context of Deaf Signers. J. Multilingual Multicultural Dev. 40 (10), 892–906. doi:10.1080/01434632.2019.1592181