- 1Institute of Social Sciences, University of Hildesheim, Hildesheim, Germany

- 2Institute of Social Sciences, Heinrich Heine University of Düsseldorf, Düsseldorf, Germany

- 3SayWay GmbH, Cologne, Germany

- 4Center for Advanced Internet Studies (CAIS), Bochum, Germany

While the political communication and participation activities of young adults are changing, this is often not adequately captured by research due to a too narrow conceptualization of the phenomenon. Our approach conceptualizes political communication as activities comprising the reception of political content, interpersonal communication regarding political issues and political participation. We incorporated both analog and digital media, as well as different forms of political participation, to reflect the complex reality of political communication activities of young adults in the digital age. On the basis of a sample from 2013, we investigated the patterns of political communication of young adults (ages 18–33 years). This age group represents the first generation to have grown up under the ubiquitous influence of the internet and other modern information technologies. In addition, we examined factors influencing the formation of different political communication patterns of this generation. Results of cluster analyses demonstrated that young adults should not be seen as a homogeneous group. Rather, we found six communication types. Interestingly, no online-only type of political communication was revealed, By applying multinomial logistic regression analysis, we were able to demonstrate that socio-demographic variables, individual resources and cognitive involvement in politics influence the likelihood of belonging to more active political communication types. The present study investigated various information and communication opportunities of young adults, and is rare in terms of the richness of data provided. Our conceptual innovative approach enables a better understanding of young adults’ complex political communication patterns. Moreover, our approach encourages follow-up research, as our results provide a valuable starting point for intergenerational comparisons regarding changes in political engagement among young adults in Germany, as well as for cross-country analysis regarding different generations of young adults.

Introduction

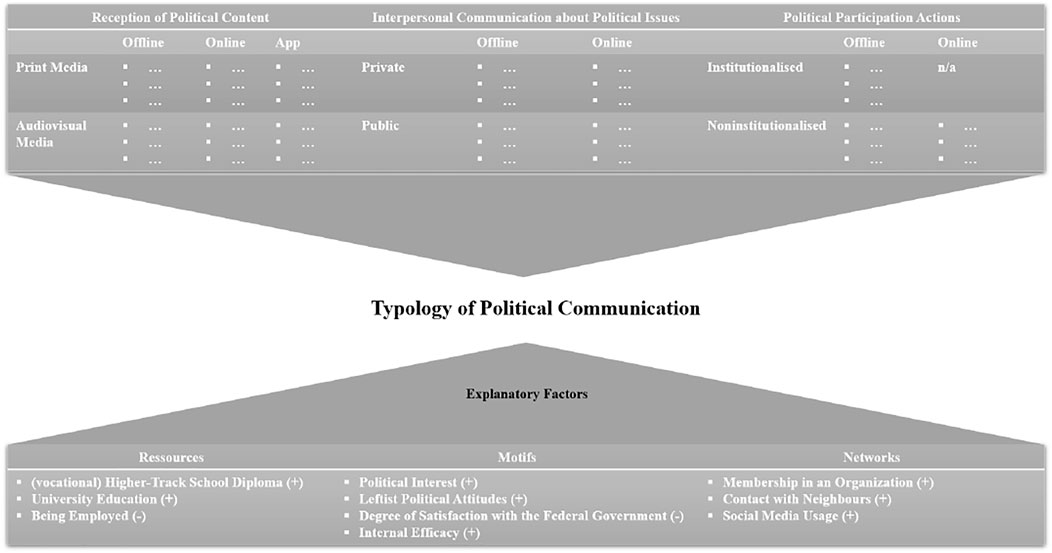

The political communication of adolescents and young adults has long been viewed critically (Mengü et al., 2015; Pontes, Henn and Griffiths 2019, 3–4). Only climate change and the Fridays for Future Movement, which began in 2019, appear to have increased political engagement among youth. Prior to this, adolescents were generally considered to be politically disinterested—especially in comparison to earlier generations (Bessant 2021, 153; Spöri, Oross and Susánszky 2020, 5). This view was supported by the declining voter turnout and the low membership rate of young people in political organizations such as political parties. At the same time, social media sites such as Facebook are also used by young people for political information and communication activities, and online-based forms of participation such as posting opinions on social media have been highly popular for a long time (Yamamoto, Kushin, and Dalisay, 2015, p. 881). For many years, young people have been faced with almost endless opportunities “to engage and express themselves and to participate politically” (Andersen et al., 2020, p. 2). This development has led some authors to believe that traditional forms of political communication and participation are gradually being replaced by online-based forms. However, empirical studies providing a general overview of political participation and communication activities are lacking. While the political communication and participation activities of young adults are changing, this is often not adequately captured by research due to a too narrow conceptualization of the phenomenon, which may have painted an incomplete picture of young adults’ political engagement in the past. This is especially true with regard to communicative forms of political action, which have become very important for young adults’ political activities due to the rise of social media (Vromen and Michael., 2015). Empirical studies providing a general overview of political participation and communication activities of young adults online and offline are lacking. Moreover, we do not have substantial empirical information on the complex political communication patterns of the first cohorts to have grown up in the era of ubiquitous technology, including computers and the Internet, and we do not know the reasons why these young people communicated as they did almost a decade ago. The above remarks emphasize the close connection between political communication and political participation. In addition to the reception of political content and interpersonal communication on political issues, it is necessary to take into account political participation, as the behavioral component of a modern understanding of political communication (Andersen et al., 2020, p. 15; McLeod, Scheufele, and Moy, 1999; Verba, Schlozman, and Brady, 1995). Owing to the Internet, and especially online social networks such as Facebook and Instagram, it is now possible to influence collectively binding decisions through communicative actions. Indeed, for many years, the Internet has played a particularly important role for political protest movements (Kneuer and Richter, 2016). The boundaries between acts of political communication and political participation seem to be increasingly dissolving, and reception, discussion, and participation often take place simultaneously (Bennett and Segerberg, 2013). Accordingly, all aspects of political engagement should be considered together. Political communication is therefore understood to include the following sub-activities: 1) reception of political content, 2) interpersonal communication about political issues, and 3) concrete political participation actions (Emmer, Vowe, and Wolling, 2011). This definition of the phenomenon of political communication simultaneously considers the above-mentioned dissolving boundaries between acts of political communication and political participation while also providing a comprehensive concept of political communication.

We aimed to identify overarching patterns of political communication of young adults in Germany and to explain them. This was possible due to a representative survey among young adults which we conducted in 2013. The survey covered various forms of political communication activities as well as hypothetical explanatory factors. At the time of the survey, the participants were aged between 18 and 33 years. This sample allows us to investigate the political communication patterns of young adults from the generation of the so-called digital natives (Prensky 2001), whilst trying to bridge the artificial division into digital and analog political communication. We focused on one country—Germany—in order to avoid possible contextual effects. The first research question was as follows: Which patterns of political communication are prevalent among young adults in Germany and what significance do online-based political communication activities have for young adults in Germany compared to traditional forms of political communication (RQ1)? In order to better understand the communication behavior of young adults from the generation of digital natives, we developed hypothetical explanatory factors, which we tested empirically. This led to the second research-guiding question: Which factors influence the formation of different political communication patterns among young adults in Germany (RQ2)?

Next, we describe the political engagement of young adults, outline the current state of research regarding the usage of different media, and present the Civic Voluntarism Model (CVM) of Verba et al. (1995) as a solid basis for our own model. We then describe the dataset and the operationalization, as well as our methodological approach. Subsequently, we present the empirical results, before finally concluding with answers to the posed research questions and suggesting future research paths.

Political Engagement of Young Adults—Patterns and Explanations

For many years, a significant decline in young adults’ participation in formal politics (Henn and Foard 2014, 361–62), as well as with regard to the consumption of television news, daily newspapers, news magazines and weekly newspapers has been observed (Yamamoto et al., 2015). Young people prefer digital media, such as social media or Netflix (Matrix 2014). It has been noted for some time that young people deploy fundamentally different forms of information seeking about politics and of becoming politically active. Younger adults make intense use of digital media to express themselves (Jones, 2020, p. 543), but also to obtain political information and to organize themselves politically (Bond, Marín, Dolch, Bedenlier, and Zawacki-Richter, 2018, p. 4; Campos et al., 2018, p. 503; Figeac et al., 2020, p. 667). For the United States , it has already been shown that Facebook is the most important source of political information for a younger age cohort (Mitchell et al., 2015, p. 8). Moreover, in recent years, there has been a marked increase in the area of interpersonal political communication via online media such as Facebook—albeit with a low overall level (Andersen et al., 2020, p. 11). It should be mentioned that political messages have a particular effect on an individual when they are received by a friend, as one experiences every day on social networks. Online social networks also have the character of entertainment media and therefore represent a lower-threshold information opportunity than party newspapers or party websites, and might thus also attract politically disinterested citizens (Quinlan, Gummer, Roßmann, and Wolf, 2017, p. 2). In addition, digital media can meet the widespread need for less formalized, time-limited participation opportunities (Schlozman, Verba, and Brady, 2010, p. 498).

Previous studies have found that young adults participate primarily in low-threshold forms of online participation, e.g., by linking to online social networks or participating in online petitions. One observation seems to be that on the Internet, preference is given to those forms of communication for political purposes that are easy to learn and uncomplicated to use (Vromen and Michael., 2015, 84). Online activism is also criticized with regard to its alleged individualistic nature, “as those involved select issues on the basis of reputational benefits, rather than collective rewards” (Dennis 2019, 124). Nevertheless, empirical findings suggest that the expansion of the information repertoire through the Internet not only leads to an intensification of political communication activities among those who were already active, but also to the activation of new recipient groups, especially among younger users (Gil de Zúñiga et al., 2009; Campbell and Kwak, 2010; Emmer et al., 2011). All in all, there is good reason to state that the evidence regarding a mobilizing effect of the Internet on political communication is still mixed. However, the question arises why some young people make use of the additional opportunities for political participation offered by the Internet, while others remain apathetic or rely on traditional forms of political influence such as voting and party work.

To explore this question, we draw on the most widely used model for explaining political actions, the Civic Voluntarism Model (CVM) of Verba et al. (1995). The CVM provides different explanatory approaches and thus the potential to connect different communication patterns with various explanatory factors. These authors deal with the question of why some individuals do not participate politically, and propose the following answers: “because they can’t, because they don’t want to, or because nobody asked” (Verba et al., 1995, p. 271). “They can’t” refers to a lack of resources, e.g., cognitive skills; “they don’t want to” implies a lack of motivation, e.g., a lack of political interest or a lack of faith in one’s own ability to shape policy; and “nobody asked” refers to a lack of integration in social networks which potentially have a mobilizing effect. Verba et al. (1995) begin by recognizing that political participation is a demanding and challenging activity that requires certain intellectual abilities. Thus, in order to understand and participate in a political issue, it is first of all necessary for a person to be able to determine his or her interests, position and concerns. A person primarily learns communicative, cognitive and organizational skills, also known as civic skills, in the various educational institutions (Verba et al., 1995, p. 271). Such skills are all the more important the more demanding the participation action is.

In addition to resources, the model contains a second block of explanatory factors for political participation: “Willingness” is assumed to be of crucial importance for political participation. There are various incentives and cognitive preconditions that drive people to get involved in politics. A central motive that promotes political participation is a person’s general political interest. Furthermore, the individual’s assessment of his or her own ability to exert influence is seen as a decisive determinant of political participation actions. People with a higher level of political self-confidence (internal efficiency) will participate more strongly in politics than those with lower self-confidence (Brady, Verba and Schlozman 1995; Mannarini et al., 2008, 98; Verba, Schlozman and Brady 1995). Moreover, one should consider explanatory factors of social psychology. In particular, dissatisfaction with the current representatives of the political system can be a strong incentive to work towards change (van Stekelenburg and Klandermans, 2013). Against the background of politically engaged young adults in Germany coming traditionally from the political left, we expect that a leftist attitude will increase individual political communication activities. Yet, the digital sphere is nowadays suspected to be dominated by right-wing activists (Krämer et al., 2021, 241). Several years ago, by contrast, online media was used much more actively by the political left than by the political right. Anti-globalization protests against the World Bank and other institutions of modern capitalism were prevalent among the youth (Kneuer and Richter 2016; Penney and Dadas 2014; van Gelder and Ruth., 2011; Vegh 2003). Moreover, climate change activism was dominated by left-wing activists who were highly active online (Knudsen., 2012). Thus, we assume that a leftist attitude will also increase online-based forms of political communication in our sample. Whether or not this has changed over time would be an interesting follow-up question and could be investigated by comparing our results with more recent research data.

The third block of explanatory factors in the CVM encompasses the observation that political participation has a strong social component (Putnam, Leonardi, and Nanetti, 1993). Relationships with other people who are politically active are a strong incentive to become politically active as well. In addition, stronger social networking increases the likelihood that a person will become aware of certain problems or opportunities for participation. Friends, acquaintances and family members function as recruitment networks in this sense. It can be argued that resources and motives relevant to participation can also be developed through social participation in associations (Lowndes 2004, 45; Putnam 1995, 667). As content on social media “is accompanied by different social cues”, e.g., “a comment by the friend who recommended it” (Andersen et al., 2020, p. 101), we need to consider the fact that interpersonal relationships are increasingly taking place in virtual space. It can therefore be assumed that social contacts on the Internet have a similar effect on political participation to personal contacts.

Against the backdrop of the CVM, we assume, first, that those young people who are equipped with more cognitive resources (higher education) belong to a type that communicates politically in an intense manner. The same is assumed for young adults who have a deeper cognitive involvement in politics (political interest, political self-efficacy and a leftist attitude) and an apathy towards the government. In addition, involvement in (digital) networks should have a positive effect on the political communication behavior of young adults, which is why socially well-integrated young adults should be more likely to belong to a politically active type than young people who are less well integrated in this respect. Finally, as political engagement is time-consuming for young adults (Bakker and Vreese, 2011; Bode, 2017), we expect young adults in employment to be less politically active than those who have more leisure time.

Materials and Methods

We sought to identify and explain overarching political communication patterns of young adults on the basis of data which we collected in 2013 and which we present in the form of this article for the first time. Specifically, we designed an online survey that was completed by participants who were registered with the online access panel provider “respondi”. The field phase of this study took place from August 22–31, 2013. The sample was drawn on the basis of the quota characteristics age, gender and education. The quota characteristics are based on the German population statistics for the age groups 18–29 years and 15–35 years. Young adults born between 1980 and 1994 constituted the target group for the survey. Thus, at the time of the survey, they were aged between 18 and 33 years. After completion of data cleaning, the final sample comprised 910 persons. The data can be regarded as approximately representative of the German online population aged between 18 and 33 years, and are therefore suitable for deriving in-depth statements on the political communication behavior of this age group.

We distinguished between receptive, interpersonal and participatory political communication, and differentiated these three dimensions into offline and online activities in order to cover different forms of the manifold possibilities to communicate politically and condense them into communication types. A total of 13 scales were formed: six scales for receptive political participation, four for interpersonal political participation and three for action-oriented political participation. These scales were used as type-forming variables in a cluster analysis in order to identify patterns of individual political communication and participation. Receptive political communication was operationalized in two steps: First, respondents were asked to indicate which daily newspapers, weekly news magazines, and weekly newspapers they usually read to obtain political information. No explicit distinction was made between the print version, the website and the apps of the newspapers or magazines. The following questions were then asked individually: Do you use 1) the print edition of the newspaper/magazine, 2) the website of the newspaper/magazine, or 3) the app of the newspaper/magazine? The respondents were also asked to indicate which news programs and political TV programs they watch to gather political information.

With regard to interpersonal political communication, we distinguished between different degrees of publicity: expressions of political opinion in the private sphere and in the public sphere. This distinction was based on the consideration that people communicate politically in public in a different way than in their private environment. For instance, people may not wish to disclose their political views in public because they fear negative consequences. Conversely, people who position themselves publicly on a political issue are usually pursuing a specific purpose—for example convincing others of their views or mobilizing them to act. With regard to participatory political communication characteristics, participants were asked about activities that extend to institutionalized participation offerings, such as voter participation and membership of political organizations. Additionally, the survey also considered non-institutionalized forms of participation. A distinction was made between offline and online activities. Most of the explanatory variables were operationalized using common indicators (e.g., civic skills were operationalized by a young person’s educational and vocational level).

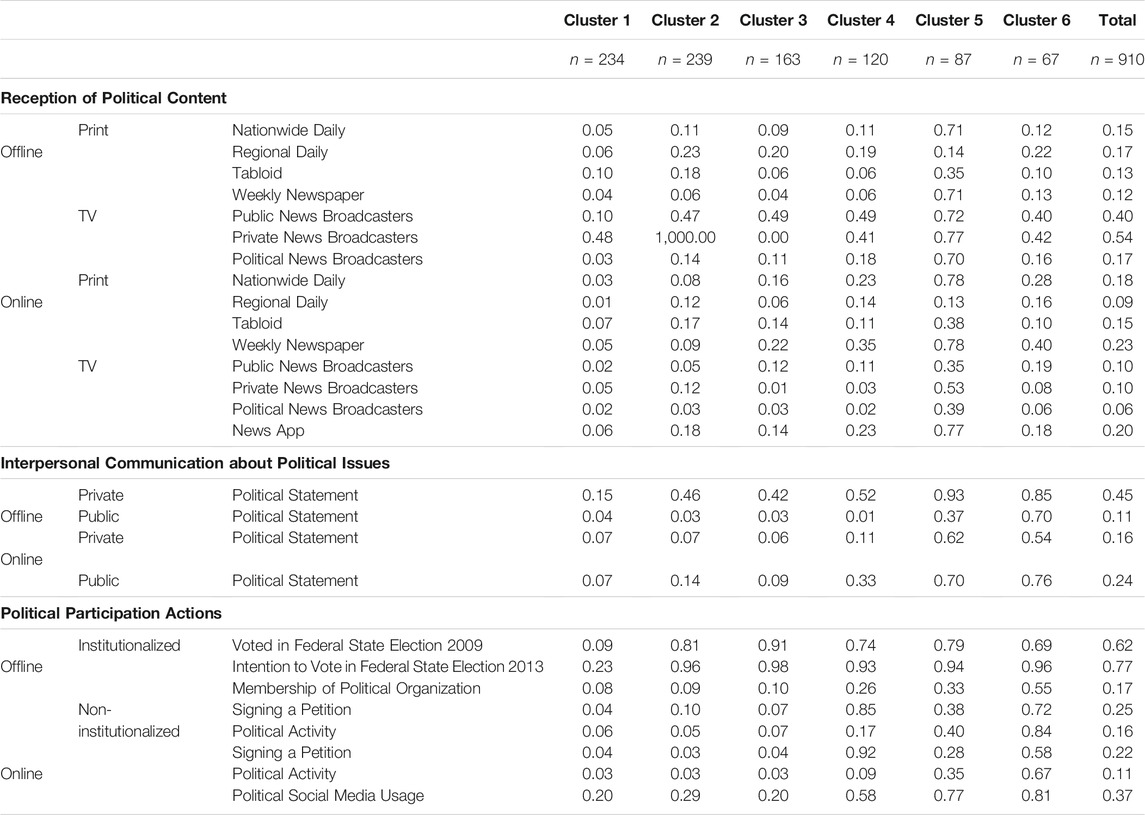

A hierarchical cluster analysis with simple matching and city block was used to identify patterns of political communication. To determine the number of clusters, a screen diagram was constructed, in which the number of clusters on the X-axis and the fusion values of the clusters on the Y-axis were plotted. Here, the highest fusion value was used to start with, resulting in a decreasing curve. This is therefore referred to as an inverse screen test. The number of clusters can be read off at the point in the diagram where a bend in the curve appears for the first time (“elbow criterion”). The “kink” is shown for six clusters. It can therefore be assumed that the optimal number of clusters is six. For a more precise characterization of the types, it is recommended to perform a K-means cluster analysis based on the results obtained so far. With the help of this procedure, the results can be further refined, which allows a better interpretation of the types. In contrast to the hierarchical cluster analysis, the K-means cluster analysis is a partitioning procedure. Based on an algorithm, the cases are assigned to the individual clusters in such a way that the variance within the clusters is minimized. This assumes that the number of clusters is known; therefore, the procedure is usually performed after a hierarchical cluster analysis (Filho et al., 2014; Hagenaars, 2006). The final distribution of cases was as follows: Cluster 1 (n = 234 or 26 %) and Cluster 2 (n = 239 or 26 %) had a roughly equal share; Cluster 3 was slightly smaller (n = 163 or 17 %). As will be shown later on, these clusters are politically rather passive types. The remaining 30 percent (n = 274) of respondents were distributed among the three active types as follows: Cluster 4 with n = 120 (13 %), Cluster 5 with n = 87 (10 %) and Cluster 6 with n = 67 (7 %).

In order to identify possible explanations for the type affiliation, as the second objective of our study is to explain the identified communication patterns of young adults, multinomial logistic regression analyses were conducted. This method requires a category to which the others should refer, and it is recommended to choose a category that is clearly defined and has a sufficiently large number of cases. To simplify the interpretation of the results, all independent variables were dichotomized. Figure 1 illustrates the described procedure graphically.

As our sample derives from a cross-sectional study, the criticism may be raised that it cannot be used to infer causality because a temporal sequence cannot be established. It is widely assumed that to investigate cause and effect, a longitudinal or experimental study is necessary. However, both methods are time and cost-intensive and are thus rarely used in social science. In addition, this view has been challenged (Wunsch, Russo and Mouchart 2010). Nevertheless, this aspect should be taken into account while reading the results.

Results

This section is structured based on the two main research questions, starting with the results of the K-means cluster analysis. Subsequently, we present the results of the multinomial logistic regression analysis to investigate potential explanatory factors for the type affiliation. The results are then discussed according to the types that have already been labeled on the basis of their main characteristics.

Table 1 shows the results of the K-means cluster analysis. Characteristic for Cluster 1 is the extremely low voter turnout compared to all other types. The young adults in this cluster have an extremely limited repertoire of information channels. Individuals belonging to this type consume political information almost exclusively from private TV news broadcasts, and do not use online media to search for political information at all. Moreover, these individuals do not take part in political discussions, either offline or online. The voter turnout in this group is on a very low level, and other forms of offline participation do not take place. Online, these individuals occasionally participate politically in online social networks. Cluster 1 is referred to as “Political Apathetics” due to the extensive lack of political activity. Overall, the Political Apathetics can be characterized as a type with low political activity and low online affinity (Table 1).

Clusters 2 and 3 have a very similar profile, with the main differences lying in the area of receptive political participation. While the proportion of recipients of private news broadcasts is particularly high in Cluster 2, members of Cluster 3 prefer public service news broadcasts. Cluster 2 is therefore called “Passive Entertainment-oriented” and Cluster 3 “Passive Information-oriented”. The Passive Entertainment-oriented mainly use TV news as a source of political information offline, giving private news programs priority over public news programs. Only a minority use regional daily newspapers. Online media play no role in the search for political information. Discussions about politics only take place offline and only in a private context. Voter turnout is high, but other forms of offline participation play no role. A minority are politically active in online social networks. Overall, the Passive Entertainment-oriented can be characterized as a type with moderate political activity and low online affinity. The passive entertainment-oriented individuals correspond to the average of the sample in nearly all characteristics and can therefore be characterized as mainstreamers (see Table 1).

The Passive Information-oriented use offline, mainly public news broadcasts to obtain political information. Their rejection of tabloid media, especially private news broadcasts, is striking. Just as with the Passive Entertainment-oriented, only a minority use regional daily newspapers. Online, a small proportion of the Passive Information-oriented obtain information about politics from the websites of news magazines. Discussions about politics only take place offline and only in a private context. Voter turnout is high, but other forms of offline participation do not play a role. Online, a minority are politically active in social networks. Overall, the Passive Information-oriented can be characterized as a type with medium political activity and medium online affinity.

The members of Cluster 4 are characterized in particular by a high willingness to participate in petitions and intensive use of online social platforms for political purposes. These both represent low-threshold forms of (online) participation, which is why Cluster 4, in reference to Füting (2011), is called “Comfortable Moderns”. The characterization of this type as “comfortable” is related to the nature of its political participation. Although a quarter of the Comfortable Moderns claim to be active in a political organization, most participation activities tend to be low-threshold and occasional. By far the most common form of participation - apart from voter participation - is participation in (online) petitions. In online social networks too, the Comfortable Moderns are more active than the average person. Offline, the Comfortable Moderns inform themselves about politics almost exclusively through public and private news broadcasts. A minority also use the websites of national daily newspapers and news magazines as a source of political information. A small proportion also use news apps. Discussions about politics usually take place offline and in a private setting. A small proportion also express themselves publicly, but only online. Voter turnout is high, and the Comfortable Moderns also participate very intensively in petitions offline. A minority are active in political organizations. Online participation in petitions is also a top priority. The Comfortable Moderns are also politically active in online social networks. Overall, the Comfortable Moderns can be characterized as a type with medium political activity and a high online affinity (Table 1).

Cluster 5 has a particularly extensive and intensively used repertoire of information, so this type is referred to as “News Junkies”. The News Junkies have a very broad information repertoire. Offline, in addition to public and private news broadcasts and political TV magazines, these individuals also use national daily newspapers and news magazines as sources of political information. Online, the News Junkies inform themselves about politics primarily on the websites of national daily newspapers and news magazines, and news apps are also used intensively. Offline, the News Junkies mainly talk about politics in private circles, but rarely express themselves publicly. Online, on the other hand, they often take part in both private and public discussions. Voter turnout is high, and a minority are also active in political organizations. A small proportion participate offline in petitions and other non-institutionalized forms of participation. Online, the News Junkies are politically active primarily in online social networks. A minority participate in online petitions and other non-institutionalized forms of participation. Overall, the News Junkies can be characterized as a type with high political activity and a high affinity for online participation.

In contrast, Cluster 6 focuses more on interpersonal and participatory political communication. Once again in reference to Füting (2011), this type is referred to as “Organized Extroverts”, since institutionalized political participation is particularly pronounced here. Organized Extroverts inform themselves about politics offline mainly through public and private news broadcasts; a minority also use regional daily newspapers. Online, they primarily use Internet sites of news magazines as sources of political information, and to a lesser extent Internet sites of national daily newspapers. Organized Extroverts participate very intensively in political discussions, regardless of whether they take place in public or private, online or offline. In addition to a high voter turnout, Organized Extroverts are also characterized by a high proportion of membership of political organizations. They also participate intensively in petitions and other non-institutionalized forms of offline participation. Online, Organized Extroverts are politically active primarily in online social networks, but they also participate in large numbers in online petitions and other non-institutionalized forms of participation. Overall, the Organized Extroverts can be characterized as a type with high political activity and a high online affinity.

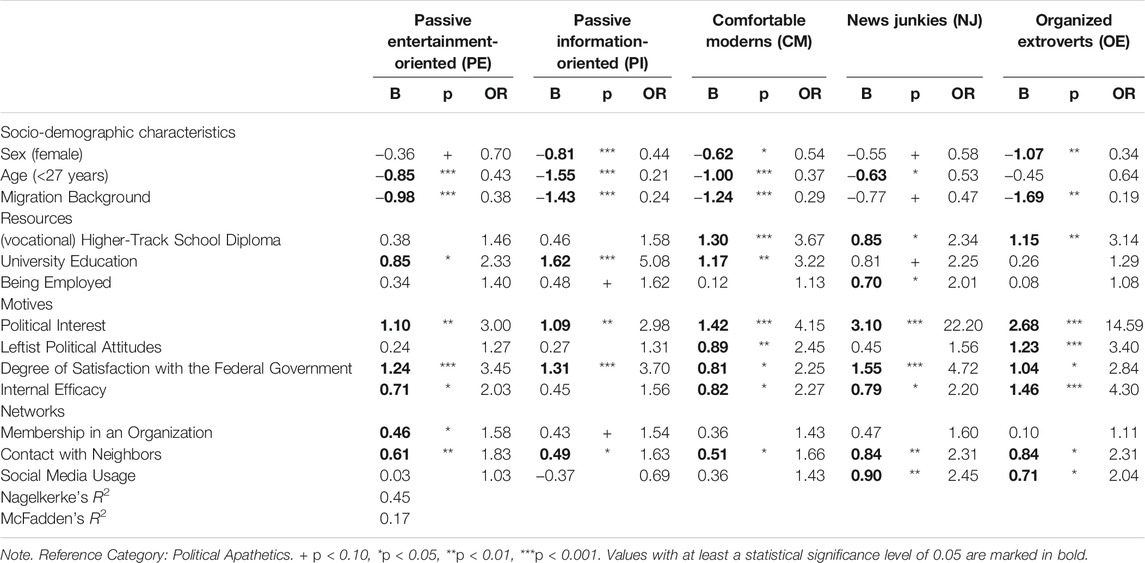

To answer the question regarding the factors influencing the type affiliation, a multinomial logistic regression analysis was conducted (Table 2). Using statistical methods, we sought to investigate to what extent the explanatory factors from our model (socio-demographic characteristics, resources, motives and networks) increase the probability that a person will belong to one of the communication types. Political Apathetics served as the reference category. With n = 234 cases, this is the second largest group within the sample. In addition, Political Apathetics exhibit a particularly clearly defined behavioral pattern because their political communication activities are far below average in all areas. For this reason, it can be assumed that significant differences with respect to the various influencing factors are most likely to be seen in the comparison between the Political Apathetics and the other types. The regression models were initially conducted separately for socio-demographic characteristics, resources, motives and networks. Only those variables that had a significant influence were considered in the model presented below.

With regard to socio-demographic effects, we found that women were approximately 66 % less likely to fall into the category of organized extroverts, as the most politically active type of communication (Exp (B) = 0.34, p < 0.01). Moreover, men were more likely to belong to communication types other than the reference category of Political Apathetics. Besides gender, age also exerted an influence, as a younger age had a significant negative influence on membership of all types compared to the Political Apathetics. The strongest negative effect of age was observed with respect to the affiliation to the Passive Information-oriented cluster. For example, a person who is at least 27 years old was approximately 79% less likely (Exp (B) = 0.21, p < 0.00) to be a passive information-oriented person than a person below the age of 27. Furthermore, young adults with a migration background showed a lower probability of belonging to a politically active communication type. In view of the findings that being a woman and having a migration background showed negative effects, it seems evident that certain social groups that are affected by experiences of exclusion in many respects tend to be passive in the political sphere.

In addition to socio-demographic characteristics, we also tested the effects of individual resources. Young adults with at least a (vocational) higher-track school diploma from the German tripartite secondary school system were more than twice as likely to belong to the Comfortable Moderns than respondents with a lower level of education (Exp(B) = 3.67, p < 0.01). Similar results emerged for the Organized Extroverts (Exp(B) = 3.14, p < 0.00) as well as for affiliation to the cluster News Junkies, albeit somewhat weaker (Exp(B) = 2.34, p < 0.05). Active political communication is apparently strongly related to certain civic skills that can be acquired in the course of higher school education. Thus, a further inequality factor is revealed: The (formal) educational level of a young adult in Germany influences his or her political communication behavior. The influence of a university education on the communication type is less clearly interpretable: Although all types showed a higher rate of academics than the reference category, there was no linear relationship between the academic level and the level of activity, as was observed in school education. Compared to the reference category, academics were more likely to belong to the Passive Entertainment-oriented cluster (Exp(B) = 2.33, p < 0.05), the Passive Information-oriented cluster (Exp(B) = 1.62, p < 0.00) and the Comfortable Moderns (Exp(B) = 1.17, p < 0.01). However, the study did not reveal a significant influence on the affiliation to the News Junkies and the Organized Extroverts. This suggests that an academic education does not necessarily lead to more political activity. The same applies to being in employment: This factor only showed a significant positive effect for News Junkies (Exp(B) = 2.01, p < 0.05), and had no statistical significance for any of the other types.

The third block of explanatory factors is composed of individual motives and psychological predispositions. First, political interest showed a high and positive correlation with the affiliation to a politically active type. All types exhibited a significant positive regression coefficient, i.e., they had a higher proportion of politically interested respondents than the reference category. The odds ratio increases almost linearly as we move to the right in the table (Table 2). Politically more active types thus exhibit a higher level of political interest. Besides the political interest, we found that leftist political attitudes exerted a significant positive influence on falling into the clusters Comfortable Moderns (Exp(B) = 2.45, p < 0.05) and Organized Extroverts (Exp(B) = 1.23, p < 0.00). Yet, the political orientation had no statistically significant influence on the affiliation to the other types. Another psychological predisposition in our model is the degree of satisfaction with the Federal government. This factor indeed increased the probability of belonging to all types. Satisfaction had the strongest effect on belonging to the News Junkies cluster (Exp(B) = 1.55, p < 0.00), the Passive Entertainment-oriented cluster (Exp(B) = 1.24, p < 0.00) and the Passive Information-oriented cluster (Exp(B) = 1.31, p < 0.00).

In contrast, the probability of belonging to the Comfortable Moderns (Exp(B) = 0.81 p < 0.05) and Organized Extroverts (Exp(B) = 1.04, p < 0.05) was not as strongly influenced by political satisfaction. Thus, we are far away from having found some kind of a linear relationship between the political activity profile and the satisfaction with the Federal government. The influence of political self-confidence (internal efficiency) on the type affiliation is easy to interpret: The affiliation to one of the politically active types (Comfortable Moderns, News Junkies, Organized Extroverts) was more strongly influenced by the internal efficiency than was the case for the two politically passive types. Therefore, it can be stated that individuals with a stronger political self-confidence (internal efficiency) are more likely to be politically active than individuals with a lower political self-confidence.

The variables from the fourth block of potential explanatory factors were not consistently relevant. For example, membership of a political organization only showed a significant positive effect for the affiliation to the Passive Entertainment-oriented cluster (Exp(B) = 1.58, p < 0.05). This variable had no statistically verifiable significance for membership of the other types. In contrast, the influence of neighborhood contact exerted a consistent positive influence on not falling into the reference category. For activity in online social networks, this only applied for the affiliation to one of the two most active types: News Junkies (Exp(B) = 2.45, p < 0.01) and Organized Extroverts (Exp(B) = 2.04, p < 0.05). The other types were not significantly influenced by this variable. This suggests that individuals who use online social networks more intensively are more likely to be politically active than individuals who do so less often. Last but not least, it should be mentioned that our model shows a good explanation of variance, with 45 percent, pointing to the good explanatory power of our model.

Discussion

In popular and sometimes also in scientific discourse, young adults are often described as individuals without interest in politics and therefore apathetic. If, by way of exception, they unexpectedly become politically active, they are then viewed as ‘digital natives’ who particularly make use of online media. This is linked to the assumption that young people have a higher online affinity and more knowledge of digital media than older people. As such, it is widely assumed that young adults solely use digital technologies for their political activities—if they are politically active at all. With regard to the first generation to have grown up in the digital age in Germany, however, this assumption cannot be clearly proven. On the basis of data from 2013, which we presented here for the first time, the assumption of apolitical digital natives needs to be reconsidered, as this generation is by no means a homogeneous group, but consists of a large number of very different subgroups. The social differentiation within young adults’ political participation, as already demonstrated by Henn and Foard (2014) with regard to Britain, to name but one such study, cannot be emphasized enough. In the present study, we incorporated both analog and digital media as well as different forms of political participation in order to reflect the complex reality of political communication activities of young adults in the digital age. We are not aware of any study with comparable scope and complexity regarding young adults’ political engagement. Only through this approach was it possible to identify six different types: 1. Political Apathetics, which is by far the least politically active type. Private news broadcasts serve as their only source of political information, and online political content is generally avoided. Members of this type rarely talk to others about political issues and have a very low voter turnout. 2. The Passive Entertainment-oriented young adults use both private and public TV news for political information, but generally avoid political content online. In private circles, political issues are discussed at least occasionally, but almost exclusively offline. Members of this type vote in elections, but are not politically active beyond that. 3. The Passive Information-oriented type differs from the aforementioned two types primarily in that Passive Information-oriented individuals avoid tabloid media as sources of political information. They mainly use public TV news, while political content on the web is hardly ever used. Moreover, interpersonal political communication takes place exclusively offline and in private surroundings. As can also be observed for the Passive Entertainment-oriented young adults, voting in elections is the only form of political participation.

Looking at the politically active types, 4. the Comfortable Moderns use private and public TV for political news consumption. Moreover, they gather information on politics via various online media, such as the websites of news magazines and national daily newspapers. In the private sphere, they almost exclusively talk offline about political issues, whereas in public they tend to position themselves online. Even outside of elections, the Comfortable Moderns are very active politically, both online and offline. Particularly noticeable is the intensive participation in petitions. 5. The News Junkies, as another politically active type, have the most extensive information repertoire; they obtain information from a variety of offline and online political sources. Interpersonal political communication is also strongly developed. In their private environment, they usually express themselves on political issues offline, and in public they tend to do so online. They take part in a variety of political actions both online and offline, but there is no clear focus. Finally, 6. the Organizational Extraverts are less interested in political information than the News Junkies, but still use a variety of different information sources, especially online. A characteristic feature of the Organizational Extraverts is that they are not afraid to stand up publicly for their political convictions - not only online but also offline, e.g., by speaking out at meetings. Of all types, the Organizational Extraverts has the highest percentage of members of political organizations.

Somewhat surprisingly, our findings revealed that online media have played only a subordinate role in the individual political communication of young adults in Germany. Two thirds of the young adults in our sample do not use the Internet for political purposes, or do so only to a very limited extent. Political information is received only incidentally by this group of people, e.g. through news broadcasts on television.

In addition to identifying political communication patterns, the study also aimed to explain factors influencing the affiliation to different political communication types. We found that resources, motives and networks each make a significant contribution to explaining the individual political communication of young adults in Germany. Among the resources, education, and particularly school education, should be highlighted. The results underscore the central importance of education for political participation of young adults, as other studies have demonstrated before, e.g., for Britain (Henn and Foard 2014; Keating et al., 2010, 18–21), the European Union (Kitanova 2020, 828), and the United States (Flanagan et al., 2012). Thus, it is safe to state that education is indisputably among the best predictors of political engagement of young people, no matter how broadly or narrowly the concept is defined.

In contrast, the assumed negative effect of employment could not be confirmed. From the set of motives, political interest yielded the strongest effects on the political communication patterns of young adults in Germany, as it significantly increased the likelihood of belonging to one of the active communication types. The same holds true for political orientation and political self-confidence. Satisfaction with the performance of the Federal government also showed a significant explanatory power for not belonging to the reference category of the politically apathetic type. However, there was no linear relationship between the level of this variable and the intensity of political communication. With regard to an individual’s social integration, only the activity in online social networks proved to be a relevant explanatory factor for type affiliation. In contrast, membership of voluntary organizations, the frequency of meetings with friends and the frequency of Internet use had no measurable influence. Overall, political interest stands out as an explanatory factor. Of all the variables tested, political interest had the strongest influence on type affiliation, thus empirically confirming one basic assumption of the CVM most clearly: The higher a young person’s political interest, the more pronounced his or her political communication activities are.

With regard to the frequency of Internet use, our result directly contradicts the findings of Nam (2012, 95), using data from a United States.-based national survey conducted 2005. He demonstrated that the likelihood to participate in online politics by those who are disengaged offline “rises significantly if they use the internet more frequently”, This contradiction illustrates well, how strong political engagement, as well as its explanation, is dependent on time and location. Patterns and explanation of political communication both are in constant flux. TheCVM appears as a constant as it has proven its worth for the matter of interest here. It has been demonstrated, once again, that the model can be used to explain very different modes of political participation. Nevertheless, it should be critically noted that we only slightly modified the CVM, even though it was not explicitly developed to explain the political participation of young adults. The relatively large proportion of unexplained variance indicates that explanatory factors other than those tested could be important for the political communication of young adults. In particular, ethical and moral incentives are becoming increasingly important for young people, as Fridays For Future shows. Gandhi’s “be the change you want to see in the world” is possibly a strong incentive for young people to get involved in politics and has been discussed for some time under the heading of “lifestyle politics” (Moor, 2017). A modification of the CVM to include variables like ethical concerns, which have proven to be useful in recent research on the political participation of young adults, would be a sensible next step in order to provide an even better description of the phenomenon to be explained. Against the background of increasing political involvement of young people and the influence of such movements on political decisions, the question of who these young people actually are is more pressing than ever. In addition, the measurement of education might be modified, as civic educational programs for youth, with a special focus on political engagement, are becoming ever more popular (Middaugh and Joseph 2009).

It remains to be said that birth cohorts are by far not as homogeneous as is suggested by ever new labels. Rather, the data presented once again point out that modern societies are fragmented in many ways. Our findings that young adults’ political communication in Germany is heterogeneous and that their communication patterns are shaped by different social predictors support the findings from other countries, including the above-mentioned research by Kitanova (2020) and Henn and Foard (2014). It can therefore not be assumed that only digital communication and participation will take place in the future, and nor that conventional forms of political commitment will disappear. However, due to significant technological changes (specifically with regard to social media) and the changed usage patterns of younger people, digital forms of political communication in the future might be more prevalent than was the case in the past. Nevertheless, empirical findings, including our own, suggest that there will be an increasing hybridization of political (youth) involvement and no online-only type of political communication. Research on the political engagement of young people during the phases of the Covid-19 pandemic-related lockdowns have demonstrated well the strong interdependency of online and offline activism (Soler i Mati et al., 2020). Online activism appear to enhance - not replace - existing offline participatory modes, as previous studies have already suggested (Nam 2012, 95–96). Interestingly and in line with previous findings, our results suggest a positive effect of social media usage on political participation (Nam 2012; Viola 2020; Vissers and Stolle 2014). Thus, one might conclude that the Internet usage as such is not increasing political engagement, but the usage of social networking sites. Since our concept of political activism includes voting, which is usually seen as an indicator for a person’s general trust in the political system, our results regarding social media are a little bit in contrary to the contemporary perspective on social media, which are alleged to constitute a danger to democracy (Hiaeshutter-Rice, Chinn and Chen 2021). Our findings, as well as previous studies that have demonstrated a reciprocal relationship between social media activism and political engagement offline (Vissers and Stolle, 2014, 273), suggest a more differentiated view on the impact of social media on democratic political systems. Either way, politics, as well as academic research has to recognize that young people’s lives, including their political activities, in the modern world are often digitally mediated (Viola 2020). Future research should further elaborate on the hybridization of political engagement of young people, as it is very likely that the online and offline spheres will continue to converge.

However, it must be pointed out that our study suffers from two shortcomings: First of all, one might criticize the fact that the survey was conducted almost a decade ago. While we agree that it is not possible to derive conclusions about today’s young adults from the investigated sample, we would argue that our sample provides valuable information about the politicization of young adults from a previous generation which was often labeled as apolitical and suggested to be almost only active in the digital sphere, if active at all. Both assumptions can be challenged on the basis of our results, which enable a better understanding of young adults born between 1980 and 1994 in Germany and clear up the myth of a rather apolitical generation that exclusively uses digital media. These findings also foster a better understanding of present-day young adults’ political activities, as our results indicate that it is not true that climate change and the Fridays for Future Movement have created the first politicized generation since the famous 1968 movement. Rather, each generation consists of very different subgroups, some of which are more politically active than others. Moreover, our results clearly show that young adults make use of manifold communication activities and are not limited to digital media. We are convinced that this is also true for subsequent generations, as evidenced by the young adults who participate offline and online in climate protest. Second, it should be emphasized that our conclusions are based on data from one country. Strictly speaking, therefore, it is not possible to draw conclusions on the political communication activities of young adults from the generation of digital natives in countries outside Germany. Nevertheless, our findings provide a valuable starting point for intergenerational comparisons regarding changes in political engagement among young adults in Germany, as well as for cross-country analysis regarding different generations. In addition, the present study offers an empirically substantiated innovative examination approach with regard to young adults’ political activities.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

Author MS was employed by the company SayWay GmbH.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Professor Matt Henn, Dr. Julianne Viola and Professor David Samuel Layfield for their valuable and constructive suggestions during the publishing process and Professor Peter Hartmann and Dr. Ole Kelm for their helpful comments and ideas during the planning and development of this research work. We acknowledge financial support by Stiftung Universität Hildesheim.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2021.729519/full#supplementary-material

References

Andersen, K., Ohme, J., Bjarnøe, C., Bordacconi, M. J., Albæk, E., and Vreese, C. de. (2020). “Generational Gaps in Political Media Use and Civic Engagement: From Baby Boomers to Generation Z,” in Routledge Studies in media, Communication, and Politics (Abingdon, Oxon, N Y: Taylor & Francis, Routledge).

Bakker, T. P., and de Vreese, C. H. (2011). Good News for the Future? Young People, Internet Use, and Political Participation. Commun. Res. 38 (4), 451–470. doi:10.1177/0093650210381738

Bennett, L., and Segerberg, A. (2013). “The Logic of Connective Action: Digital Media and the Personalization of Contentious Politics,” in Cambridge Studies in Contentious Politics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Bode, L. (2017). Gateway Political Behaviors: The Frequency and Consequences of Low-Cost Political Engagement on Social Media. Soc. Media + Soc. 3 (4), 205630511774334. doi:10.1177/2056305117743349

Bond, M., Marín, V., Dolch, C., Bedenlier, S., and Zawacki-, R. O. (2018). Digital Transformation in German Higher Education: Student and Teacher Perceptions and Usage of Digital media. Int. J. Educ. Tech. Higher Edu. 15 (1). doi:10.1186/s41239-018-0130-1

Brady, H. E., Verba, S., and Schlozman, K. L. (1995). Beyond SES: A Resource Model of Political Participation. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 89, 271–294. doi:10.2307/2082425

Campbell, S. W., and Kwak, N. (2010). Mobile Communication and Civic Life: Linking Patterns of Use to Civic and Political Engagement. J. Commun. 60 (3), 536–555. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2010.01496.x

Campos, R., Simões, J. A., and Pereira, I. (2018). Digital Media, Youth Practices and Representations of Recent Activism in Portugal. Communications 43 (4), 489–507. doi:10.1515/commun-2018-0009

de Moor, J. (2017). Lifestyle Politics and the Concept of Political Participation. Acta Polit. 52 (2), 179–197. doi:10.1057/ap.2015.27

Dennis, J. (2019). Beyond Slacktivism: Political Participation on Social Media. Interest Groups, Advocacy and Democracy Series. Cham: Springer International Publishing. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-00844-4

Emmer, M., Vowe, G., and Wolling, J. (2011). Bürger online: Die Entwicklung der politischen Online-Kommunikation in Deutschland. Konstanz: UVK-Verlags-Gesellschaft.

Figeac, J., Smyrnaios, N., Salord, T., Cabanac, G., Fraisier, O., Ratinaud, P., et al. (2020). Information-sharing Practices on Facebook during the 2017 French Presidential Campaign: An "unreliable Information Bubble" within the Extreme Right. Communications 45 (s1), 648–670. doi:10.1515/commun-2019-0193

Filho, D. B. F., Rocha, E. C. d., Júnior, J. A. d. S., Paranhos, R., Silva, M. B. d., and Duarte, B. S. F. (2014). Cluster Analysis for Political Scientists. Am 05 (15), 2408–2415. doi:10.4236/am.2014.515232

Flanagan, C., Finlay, A., Gallay, L., and Kim, T. (2012). Political Incorporation and the Protracted Transition to Adulthood: The Need for New Institutional Inventions. Parliamentary Aff. 65 (1), 29–46. doi:10.1093/pa/gsr044

Füting, A. (2011). “Wie kommunizieren die Deutschen über Politik? Eine typologische Längsschnittanalyse. [How Do Germans communicate about politics? A longitudinal typological analysis],” in Bürger online. Die Entwicklung der politischen Online-Kommunikation in Deutschland. Editors J. Wolling, G. Vowe, and M. Emmer (Konstanz: UVK), 219–244.

Gil De Zúñiga, H., Puig-I-Abril, E., and Rojas, H. (2009). Weblogs, Traditional Sources Online and Political Participation: an Assessment of How the Internet Is Changing the Political Environment. New Media Soc. 11 (4), 553–574. doi:10.1177/1461444809102960

Henn, M., and Foard, N. (2014). Social Differentiation in Young People's Political Participation: The Impact of Social and Educational Factors on Youth Political Engagement in Britain. J. Youth Stud. 17 (3), 360–380. doi:10.1080/13676261.2013.830704

Hiaeshutter-Rice, D., Chinn, S., and Chen, K. (2021). Platform Effects on Alternative Influencer Content: Understanding How Audiences and Channels Shape Misinformation Online. Front. Polit. Sci. 3. doi:10.3389/fpos.2021.642394

Jones, R. H. (2020). Creativity in Language Learning and Teaching: Translingual Practices and Transcultural Identities. Appl. Linguistics Rev. 11 (4), 535–550. doi:10.1515/applirev-2018-0114

Keating, A., Kerr, D., Benton, T., Mundy, E., and Lopes, J. (2010). Citizenship Education in England 2001– 2010: Young People’s Practices and Prospects for the Future: The Eighth and Final Report from the Citizenship Education Longitudinal Study. London: Department of Education.

Kitanova, M. (2020). Youth Political Participation in the EU: Evidence from a Cross-National Analysis. J. Youth Stud. 23 (7), 819–836. doi:10.1080/13676261.2019.1636951

Kneuer, M., and Richter, S. (2016). “Global Crisis - National Protests. How Transnational Was the Online Communication of the Occupy and Acampada Indignation Movements?” in Political Communication in Times of Crisis. Editors Ó.G. Luengo (Berlin: Logos Verlag), 193–209.

Knudsen, B. T., and Stage, C. (2012). Contagious Bodies. An Investigation of Affective and Discursive Strategies in Contemporary Online Activism. Emot. Space Soc. 5 (3), 148–155. doi:10.1016/j.emospa.2011.08.004

Krämer, B., Fernholz, T., Husung, T., Meusel, J., and Voll, M. (2021). Right-Wing Populism as a Worldview and Online Practice: Social Media Communication by Ordinary Citizens between Ideology and Lifestyles. Eur. J. Cult. Polit. Sociol. 8 (3), 1–30. doi:10.1080/23254823.2021.1908907

Lowndes, V. (2004). Getting on or Getting by? Women, Social Capital and Political Participation. The Br. J. Polit. Int. Relations 6, 45–64. doi:10.1111/j.1467-856X.2004.00126.x

Mannarini, T., Legittimo, M., and Talò, C. (2008). Determinants of Social and Political Participation Among Youth. A Preliminary Study. Psicología Política 36, 95–117.

Matrix, S. (2014). The Netflix Effect: Teens, Binge Watching, and On-Demand Digital Media Trends. Jeunesse 61, 119–138. doi:10.1353/jeu.2014.0002

McLeod, J. M., Scheufele, D. A., and Moy, P. (1999). Community, Communication, and Participation: The Role of Mass Media and Interpersonal Discussion in Local Political Participation. Polit. Commun. 16 (3), 315–336. doi:10.1080/105846099198659

Mengü, S. Ç., Güçdemir, Y., Ertürk, D., and Canan, S. (2015). Political Preferences of Generation Y University Student with Regards to Governance and Social Media: A Study on March 2014 Local Elections. Proced. - Soc. Behav. Sci. 174, 791–797. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.01.616

Middaugh, E., and Joseph, K. (2009). Online Localities: Implications for Democracy and Education. Yearb. Natl. Soc. Study Edu. 108 (1), 192–218.

Mitchell, A., Gottfried, J., and Matsa, K. E. (2015). Millennials and Political News: Social Media – the Local TV for the Next Generation? Available at: http://www.journalism.org/2015/06/01/millennials-political-news/(Accessed August 17, 2018).

Nam, T. (2012). Dual Effects of the Internet on Political Activism: Reinforcing and Mobilizing. Government Inf. Q. 29, S90–S97. doi:10.1016/j.giq.2011.08.010

Penney, J., and Dadas, C. (2014). (Re)Tweeting in the Service of Protest: Digital Composition and Circulation in the Occupy Wall Street Movement. New Media Soc. 16 (1), 74–90. doi:10.1177/1461444813479593

Pontes, A. I., Henn, M., and Griffiths, M. D. (2019). Youth Political (Dis)engagement and the Need for Citizenship Education: Encouraging Young People's Civic and Political Participation through the Curriculum. Educ. Citizenship Soc. 14 (1), 3–21. doi:10.1177/1746197917734542

Prensky, M. (2001). Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants Part 1. On the Horizon 9 (5), 1–6. doi:10.1108/10748120110424816

Putnam, R. D. (1995). Tuning in, Tuning Out: The Strange Disappearance of Social Capital in America. PS: Polit. Sci. Polit. 28 (4), 664–683. doi:10.2307/420517

Putnam, R. D., Leonardi, R., and Nanetti, R. (1993). Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Quinlan, S., Gummer, T., Roßmann, J., and Wolf, C. (2017). ‘Show Me the Money and the Party!’ - Variation in Facebook and Twitter Adoption by Politicians. Inf. Commun. Soc. 7, 1–19. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2017.1301521

Schlozman, K. L., Verba, S., and Brady, H. E. (2010). Weapon of the Strong? Participatory Inequality and the Internet. Perspect. Polit. 8 (02), 487–509. doi:10.1017/s1537592710001210

Soler i Martí, R., Ferrer-Fons, M., and Terren, L. (2020). The Interdependency of Online and Offline Activism: A Case Study of Fridays for Future-Barcelona in the Context of the COVID-19 Lockdown. Hipertext.net 21, 105–114. doi:10.31009/hipertext.net.2020.i21.09

Spöri, T., Oross, D., and Susánszky, P. (2020). Active Youth? Intersections 6, 4. doi:10.17356/ieejsp.v6i4.792

van, and S. Ruth (Editors) (2011). This Changes Everything: Occupy Wall Street and the 99% Movement (San Francisco, Calif., London: Berrett-Koehler; McGraw-Hill). Available at: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&scope=site&db=nlebk&db=nlabk&AN=407714.

van Stekelenburg, J., and Klandermans, B. (2013). The Social Psychology of Protest. Curr. Sociol. 61 (5-6), 886–905. doi:10.1177/0011392113479314

Vegh, Sandor. (2003). “Classifying Forms of Online Activism.: The Case of Cyberprotests against the World Bank,” in Cyberactivism: Online Activism in Theory and PracticeMartha McCaughey and Michael D. Ayers, 71–95 (Hoboken: Taylor & Francis).

Verba, Sidney., Lehman Schlozman, Kay., and Brady, H. E. (1995). Voice and Equality: Civic Voluntarism in American Politics. 4. Printing. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard Univ. Press.

Viola, Julianne. K. (2020). Young People's Civic Identity in the Digital Age. Palgrave Studies in Young People and Politics Ser. Cham: Springer International Publishing AG. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-37405-1

Vissers, S., and Stolle, D. (2014). Spill-over Effects between Facebook and On/Offline Political Participation? Evidence from a Two-Wave Panel Study. J. Inf. Tech. Polit. 11 (3), 259–275. doi:10.1080/19331681.2014.888383

Vromen, A., and Michael, A. (2015). Xenos, and Brian Loader. “Young People, Social Media and Connective Action: From Organisational Maintenance to Everyday Political Talk. J. Youth Stud. 18 (1), 80–100. doi:10.1080/13676261.2014.933198

Wunsch, G., Russo, F., and Mouchart, M. (2010). Do We Necessarily Need Longitudinal Data to Infer Causal Relations? Bull. Sociological Methodology/Bulletin de Méthodologie Sociologique 106 (1), 5–18. doi:10.1177/0759106309360114

Keywords: political communication, political participation, digital media, youth, young adults, multinomial logistic regression analysis, typology of political communication, digital natives

Citation: Datts M, Wiederholz J-E, Schultze M and Vowe G (2021) Political Communication Patterns of Young Adults in Germany. Front. Commun. 6:729519. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2021.729519

Received: 23 June 2021; Accepted: 29 October 2021;

Published: 29 November 2021.

Edited by:

Matt Henn, Nottingham Trent University, United KingdomReviewed by:

Julianne Viola, Imperial College London, United KingdomDavid Samuel Layfield, University of Maryland University College, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2021 Datts, Wiederholz, Schultze and Vowe. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mario Datts, bWFyaW8uZGF0dHNAdW5pLWhpbGRlc2hlaW0uZGU=

Mario Datts

Mario Datts Jan-Erik Wiederholz2

Jan-Erik Wiederholz2 Gerhard Vowe

Gerhard Vowe