95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Commun. , 08 November 2021

Sec. Science and Environmental Communication

Volume 6 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2021.723999

This article is part of the Research Topic Communication, Race, and Outdoor Spaces View all 10 articles

Rural, coastal communities in the Jobos Bay region of southeastern Puerto Rico confront disproportionate harms as an energy sacrifice zone. This space is constituted by imported fossil fuel dependency, economic and climate injustices, environmental racism, ecocide, US colonialism and imperialism, neoliberalism, and racial capitalism. In response, many grassroots actors mobilize against the toxic assault on their communities to push for alternatives beyond the suffocating status quo via apoyo mutuo [mutual support]. This survival work and movement building occur literally in “the outdoors” and in other intertwined multispecies environments, challenging narrow, oppressive colonial, and consumerist constructs that reduce “the outdoors” to recreation and thus erase the numerous ways that people labor in, honor, and defend places and spaces to lead good lives. Thus, critical examinations of communication and race/racism/racialization in and about this colonial US territory must grapple with the brutalities and pain caused by systemic and structural cruelties and translate how, where, and with whom self-determined and potentially liberatory environmental and energy justice advocacy takes shape to refuse a trauma-only narrative. Studying these embodied and emplaced efforts positions energy and power broadly construed, including in the form of collective action. This article centers on the collaborative energies of local grassroots actors and scholars who ideologically and politically align and who value working together toward anti-colonial praxis. To provide one example of how these collaborations can yield public-facing projects that contribute to struggles tied to the survival and well-being of the most impacted communities, this essay focuses on the creation of an environmental justice children’s book. This bilingual text documents and translates the pollution caused by a US-owned, coal-fired power plant and mobilizations to topple this corporate invader. The article concludes by reflecting on some of the difficulties and possibilities that emerged during multi-year coalitional relationships that inform and exceed the children’s book. To reject racist and colonial dominant assumptions and discourses about outdoor spaces as only privileged recreational areas or as a “blank slate” devoid of people and culture, this project narrates how grassroots organizers and scholars persist in continued study and struggle for power(ful) transformations in Jobos Bay and beyond.

Quieren detener la propagación del coronavirus, pero nadie mira la plaga mayor que seguirá matándonos día a día por los siguientes años. Hay una pandemia mayor que el COVID-19 y sólo tiene tres letras: AES. [They (government officials) want to stop the spread of the coronavirus, but no one looks at the bigger plague that will continue killing us day by day for the following years. There is a bigger pandemic than COVID-19 and it only has three letters: AES.]1

-Mabette Colón Pérez, student and community activist, Guayama, Puerto Rico

Applied Energy Services (AES) is responsible for the US-owned 454-megawatt carbonera [coal-fired power plant] that Mabette Colón Pérez describes in this interview with Puerto Rican writer and community activist Víctor Alvarado Guzmán, 2020.2 Since 2002, Colón Pérez and her coastal neighbors have been forced to host this unwanted occupying “plaga,” which is one of Puerto Rico’s two most polluting power plants (Santiago and Gerrard, 2021). This facility operates in the rural, southeastern municipality of Guayama in the Jobos Bay region and ecosystem, where residents have a median annual household income of $15,000 (Lloréns, 2016). To witness this powerhouse and its five-story high coal ash heap is to confront the material entanglements of an imported fossil fuel-dependent economy, economic and climate injustices, environmental racism, ecocide, US colonialism and imperialism, neoliberalism, and racial capitalism (Lloréns, 2020; Onís, 2021). Simultaneously, the carbonera creates an urgent need for communally self-determined environmental and energy justice that counters the colonial framing of “the great outdoors.”3 This “frontier mythology [is] built on white heteronormative masculinity and a eugenicist investment in able white bodies” that is tied to logics and discourses of possession, national belonging, and “consumer citizenship” (Wald, 2018, pp. 53, 63). In contrast, for Jobos Bay area residents, the outdoor spaces and places they experience are for working, honoring, and defending, as their survival depends on interconnected multispecies environments that are poisoned by numerous forms of pollution. Accordingly, Colón Pérez’s cautionary statement elucidates the high stakes for opposing the toxic AES site and its diffusion in the form of cenizas [coal ash] along a “death route” (Lloréns and Santiago, 2018a; Lloréns, 2020). This lethal “life cycle” begins with extracting coal in Colombia, which then is transported to Puerto Rico and, because of reckless storage and disposal practices, has harmed human and more-than-human bodies in this colonial US territory, the Dominican Republic, and Florida (see Figure 1).4 This material exigency necessitates transforming energy and power broadly construed “from below” (García-López, 2020).

FIGURE 1. The AES plant, photographed here in May 2015, permeates natural and human-made borders via coal ash dispersal, including in previous uses of this toxic substance as fill and building material. Image credit: Catalina M. de Onís.

US colonialism, imperialism, neoliberalism, and racial capitalism have been met with tenacious resistance from grassroots groups in southeastern Puerto Rico, exemplified by Colón Pérez, and many of her neighbors, as well as supporters throughout the archipelago and in the US diaspora (Berman Santana, 1996; Lloréns, 2021; Onís et al., 2020a). These energy actors5 have opposed and worked toward alternatives to multinational corporations and polluting fossil fuel plants that have treated the Jobos Bay region and its mixed-race and Afro-descendant residents as a “peripheral sacrifice zone within a periphery” (Lloréns, 2018). Historically, many community members labored on sugarcane plantations and faced generations of displacement and migration between the United States and Puerto Rico’s archipelago because of the precarities and abuses inherent in the capitalist, topdown production model (Berman Santana, 1996; Lloréns, 2016). This past and present dispossession, accelerated by earthquakes and increasingly intense and frequent hurricanes linked to global heating, necessitates imagining and implementing the anti-colonial alternatives advocated by many grassroots energy actors. These approaches to convivir (coexist) otherwise advance local self-determination and community-designed and -directed projects and experiences that cultivate habitable spaces for life-giving and -sustaining relations amid compounding crises (Atiles Osoria, 2014; Onís, 2018a; Onís, 2018b; Lloréns and Santiago, 2018b; Lloréns and Stanchich, 2019; Garriga-López, 2020; Soto Vega, 2020). As this essay describes, these activities and practices often are energized by enactments of apoyo mutuo [mutual support] that value interspecies relationalities. These literal and figurative sites of “survival work,” accompanied by struggles for systemic root changes, are in direct tension with and exist beyond racial capitalism and colonialism (García-Quijano and Lloréns, 2017; Spade, 2020, p. 1).

Writing with great concern for Puerto Rico, as a member of the US Puerto Rican diaspora, I join this special issue on “Communication, Race, and Outdoor Spaces” with an interest in environmental and energy justice from an anti-colonial position that centers embodied, emplaced ways of being, knowing, and communicating in rural, coastal, and archipelagic communities. To do so, this essay understands “nature and environment as relational sites for navigating both embodied racial identities and ecological space and place” (Nishime and Hester Williams, 2018, p. 4). Examining these “racial ecologies” emphasizes the connections between co-constituting environments and race/racialization, which “shift and change over time but are always intertwined” (Nishime and Hester Williams, 2018, p. 4). Calling out and combatting the white supremacy, racism, and capitalist economic exploitation that cause disproportionate experiences with toxic exposures and environmental degradation, many environmental justice scholars, advocates, and activists long have insisted that “the environment” is not a place apart, set aside only for recreation, but rather is where people live their lives (Di Chiro, 1996; Pezzullo, 2007; Sandler and Pezzullo, 2007). Challenging this false boundary involves delinking from narratives, tropes, and discourses that uphold the master framing of “the great outdoors” as a white ecotopia that finds its resilient strength in the colonial binaries of “polluted” and “pollutable,” “pristine” and “pure,” and “wild nature” and “civilization” (Buescher and Ono, 1996; Enck-Wanzer, 2011; Park and Pellow, 2011; Wanzer-Serrano, 2015; Sifuentez, 2016; García-Quijano and Lloréns, 2017; Castro-Sotomayor, 2019). Furthermore, divisionary constitutions of and assumptions about “the outdoors” and “the indoors” should be troubled because these in and out markers are diffuse, permeable, fluid, and mutable. As the environmental justice adage makes clear: “The wind blows, and the water flows” (Pezzullo and Depoe, 2010, p. 89). Contextual and cultural differences also matter for communicating indoor and outdoor spaces, as communities interact with/in environments differently based on natural and built conditions and the privileges and precarities they experience (Park and Pellow, 2011).6 Echoing and extending these crucial challenges to privileged preservation, conservation, and sustainability discourses and their consumerist investments, this article highlights power and energy as key interrelated concepts for analysis and for impelling tangible action.

Critical environmental and energy justice communication studies support collective struggles for dismantling racial capitalism, environmental racism, coloniality, and US empire building (Melamed, 2011; Pulido, 2016a; Pulido, 2016b; Pellow, 2018). Grassroots energy actor and scholar colaboradores [collaborators] may work together to record, translate, analyze, critique, share, magnify, and reanimate different rhetorical materials.7 These expressive energies strive to reimagine dominant coloniality-laden understandings of “outdoor spaces” as a “blank slate” for wealthy occupiers and investors (Onís, 2021, p. 69). Jobos Bay area communities experience extreme pollution and extraordinary beauty in “the outdoors,” where they live, labor, rest, organize, and make camp to rebel against injustice.8 Many residents also participate in subsistence fishing and crabbing, which carries cultural significance, enacts an alternative economy, and provides sustenance (García-Quijano and Lloréns, 2017). Full access to unthreatened places and spaces for various activities and purposes is vital for communities fighting to survive and to live good lives, as they respond to and resist everyday stressors (e.g., anti-Black racism, poverty, colonialism and coloniality, English monolingualism, and toxic air, water, soil, noise, and light pollution) and acute climate- and energy-related emergencies (e.g., hurricanes, extreme heat, and prolonged blackouts) linked to disaster and colonial capitalism. Thus, the ways in which energy actors communicate what “the outdoors” means and for whom marks a crucial site of study, contestation, and struggle that animates this essay and its contributions to what I call Puerto Rican environmental and energy communication studies.

To document and translate possibilities for coalitional work that critically engages oppressive and oppositional conceptualizations of “communication, race, and outdoor spaces,” this essay presents its contributions in four parts. First, I describe my positionality and connections to Puerto Rico in terms of familial, kinship, and research ties. After expressing these multiple un/belongings, which inform and complicate how I understand and approach Puerto Rico, I cite a blend of literature on decolonial, energy, Puerto Rican, archipelagic, and environmental communication studies to call for centering anti-colonial imaginings and methods in environmental and energy justice scholarship. To elucidate why this emphasis matters, I provide an overview of the US colonial territory’s complex energy politics. Second, I describe how many residents in Jobos Bay communities have responded to exploitation and dispossession by cultivating relationalities that envision and enact alternatives. These efforts are apparent in the ways in which several energy actors and groups honor and nourish interconnectedness and reciprocal relations via apoyo mutuo. Such an approach also can be translated to grassroots energy actor and scholar collaborations that practice a similar ethic of care toward struggling for environmental and energy justice in many relational spaces that take place literally in “the outdoors” and in other areas that shape and are shaped by interspecies connectivities. Third, I present a case study of how several coauthors and I created a bilingual environmental justice children’s book: La justicia ambiental es para ti y para mí/Environmental Justice Is for You and Me. This interdisciplinary, intergenerational, and archipelagic-diasporic project provides an example of how knowledges about audience, translation, storytelling, message framing, energy politics, and more can provide applied communication offerings to support struggles for material transformations linked to master and marginalized articulations of “outdoor spaces.” Fourth and finally, I conclude by reflecting on the pitfalls and possibilities of engaging in grassroots energy actor and scholar collaborations and their significance for anti-colonial methods and praxis that prioritize, learn from, and consensually work in coalition with those most impacted by environmental and energy injustices. In doing so, this essay aims to translate and amplify ongoing collective action by local organizers and their accomplices in the US Puerto Rican diaspora to imagine and implement alternative relationships with power and energy in their many forms.

Since 2014, first as a graduate student and now as a professor, I have studied and supported self-determined grassroots environmental and energy justice communication and material struggles during extended visits to Puerto Rico and remotely in the continental United States. As a Puerto Rican, Spanish American, and Irish American woman, who was born and raised in the US diaspora, my family history, white-passing and financial privileges, bilingualism (including frustrating struggles to learn Spanish more fully, while sometimes being disciplined for speaking the language), and multiple un/belongings profoundly shape how I understand, relate to, and write and talk about this Caribbean archipelago. I hold the multiple roles of a family member, friend, researcher, teacher, diasporic co-conspirator, and more. My positionality, identities, and kinships result in the liminal contradiction of feeling and being connected to and disconnected from Puerto Rico, including coastal communities, such as Mayagüez, my grandmother’s birthplace. In response to these complexities, across time and space, I have attended carefully to power differentials to try to refuse extractivist research that reproduces oppressive relations and structures when interacting with grassroots energy actors in Jobos Bay communities. While a thorough discussion of these experiences exceeds the space available in this article, I describe this reflexive process in Energy Islands: Metaphors of Power, Extractivism, and Justice in Puerto Rico (Onís, 2021).

Given my many privileges and the disproportionate power I hold as a scholar who can reach and influence multiple audiences, critical and collaborative “radical reflexivity” that seeks to dismantle oppressive relations marks a key site for countering the neoliberal capitalist and colonial currents that power academia (Tuck and Yang, 2013; Temper et al., 2019, p. 3; Lee and Ahtone, 2020; Lechuga, 2021). Settler colonialism and coloniality are foundational to dominant communication studies assumptions and practices, including in environmental and energy communication studies (Enck-Wanzer, 2011; Castro-Sotomayor, 2019; Banerjee and Sowards, 2020; Lechuga, 2020). Most academic institutions uncritically applaud scholarship that makes a department or university advance its “engaged research,” without considering how these interactions may fail to care about the political, material consequences of recording and circulating experiences, struggles, and stories to reach wider audiences. The language of “civic engagement,” “listening to,” “amplifying,” and “collaborative research,” among other related concepts and practices, easily can replicate paternalistic and other colonial relationships related to energy and power in certain contexts (Alcoff, 1991; Tuck and Yang, 2013; Wald, 2018). Accordingly, contemplations of what (not) to record and tell, how, when, where, and by and with whom are imperative for navigating difficult tensions that arise in applied communication collaborations that refuse academic pressures and messages to “produce” and “engage” more. Ethically collaborating with frontline/coastline communities—home to many residents who resist and refuse their exploitation and expulsion—requires addressing asymmetrical power relations among collaborators, attending carefully to values, and challenging normative practices and assumptions (Hale, 2006; Lotz-Sisitka et al., 2016; Temper et al., 2019; Pellow, 2020). These focus areas are essential for examining race/racism/racialization in “outdoor spaces” to advance critical environmental and energy justice communication studies that support self-determined movement struggles and the local people who energize them (Pellow, 2018).

Energy justice scholars and practitioners in the United States and Puerto Rico have done well to trouble dominant energy studies that neglect or oversimplify difference and inequities, which too often separate technological transformations from culture and power. These researchers explain that conceptualizing energy transitions as only about technology challenges seriously overlooks the many power inequities shaping these controversies and possibilities (Castro-Sitiriche, 2019; Fortier et al., 2019; O’Neill-Carrillo et al., 2017; O’Neill-Carrillo et al., 2019). Energy studies must account adequately for how privilege and precarity impact the lived experiences of individuals, families, and communities struggling for sustainable jobs, clean air and water, and the protection of places and people about which they care (Teron and Ekoh, 2018). This critical attention evinces the importance of situated, place-based analyses of energy in/justice in practice, including in non-continental spaces, to consider and contribute to “archipelagic rhetoric” (Na’puti, 2019).

Islands and archipelagoes tend to be homogenized by a colonial, imperial gaze that erases marginalized histories, ongoing existences, and differential experiences in various spaces. This Othering is fueled and maintained by hierarchies that are constituted by discourses, narratives, tropes, and policies that communicate the binaries of inferior and superior and disposable and dominant. Puerto Rico, the former colonial “rich port” of Spain (1493–1898) and now the colonial “unincorporated territory” of the United States (since 1898), fits this description. The archipelago’s coastal regions long have been targeted and occupied by the US military and sugarcane, fossil fuel, biotechnology, and pharmaceutical industries (Berman Santana, 1996; García-Quijano and Lloréns, 2017). This system of exploiting people and environments has come at a very high cost that includes and exceeds grave economic injustices that have been unevenly experienced.

Though all of Puerto Rico demonstrates long histories of environmental and energy injustices, the southeastern region exhibits heightened environmental racism, given the disproportionate impacts of polluting power plants on the low-income and -wealth individuals who live there, many of whom are mixed-race and Afro-descendant people (Lloréns, 2014; García-Quijano et al., 2015; Lloréns, 2016; García López et al., 2017; Lloréns and Santiago, 2018a; Lloréns, 2021; Onís, 2021). Residents rely on surrounding environments for food, income, and recreation while practicing communal belonging and honoring coastal traditions and ways of surviving, such as subsistence fishing (García-Quijano et al., 2015; García-Quijano and Lloréns, 2017; García-Quijano and Poggie, 2020). These lifeways face serious threats, as Jobos Bay communities are toxically assaulted (Pezzullo, 2006). Studies link the relentless noise, air, water, soil, and light pollution to respiratory problems (e.g., asthma, sinusitis, chronic bronchitis), skin rashes, cardiovascular illnesses, cancer, and reproductive injustices, including spontaneous abortions (Santiago, 2012; Alfonso, 2016; Albarracín et al., 2017; Lloréns and Santiago, 2018b; Feliciano and Green, 2018; Alfonso, 2019a; Alfonso, 2019b; Fox, 2021).

The owners and managing officials of the AES coal plant are responsible for many of these public health and environmental and energy injustices. The facility’s combustion residual waste (coal ash) contains arsenic, lead, cadmium, and other heavy metals (Garrabrants et al., 2012). As Puerto Rican journalist Omar Alfonso documents, residents and coalitional partners have organized vigorously for the removal of many tons of coal ash on the AES property and throughout Puerto Rico, the cleanup of this byproduct that has been dispersed and used throughout their neighborhoods, and the ultimate closure of the carbonera. Over the years, land, air, and water defenders have employed a variety of strategies and tactics, including encampments, physically blocking trucks with their bodies, and legislative activities (Lloréns, 2016; Lloréns, 2020). Members of the grassroots Resistencia contra la quema de Carbón y sus Cenizas tóxicas (la Resistencia RCC) and Comunidad guayamesa unidos por tu salud, among others, often have faced intense repression and brutal force from police (LeBrón, 2019; Onís et al., 2020a). Also, motivating mobilizations is local knowledge that the carbonera has contaminated the South Coast Aquifer, the sole source of drinking water for tens of thousands of residents. At the same time, community members encounter water rationing to address ongoing drought and scarcity concerns caused by, in part, centralized fossil fuel plants, which heavily rely on water for their operations (Santiago and Gerrard, 2021). In January 2020, the then Puerto Rican governor signed a law that would ban the accumulation of more than 180 days’ worth of coal ash waste on the AES property (Cortés-Chico, 2020). In response, several public hearings on the proposed regulation were held, and disputes regarding enforcement by Puerto Rico’s Department of Natural and Environmental Resources are ongoing, including in the form of demonstrations using the slogan “Una sola lucha” [“One Single Struggle”] to express the multiple, interrelated harms inflicted upon residents and the spaces where they live. Given these exigencies, while all people in Puerto Rico experience some form of toxic pollution with the ubiquity and banality of chemical exposures today, Jobos Bay communities live in an energy sacrifice zone (Pezzullo, 2014; Hernández, 2015; Lloréns, 2016; Onís, 2017; Onís, 2021). More recently, in spring and summer 2021, environmental, community, agricultural, labor, religious, and other groups raised their voices to demand greater enforcement of penalties for illegal coal ash dumping and increased communication when communities have been exposed to coal ash, among other demands. This activism is part of the long-term struggle to rid Puerto Rico of the AES coal-fired power plant and in response to a 2021 regulation by the Department of Natural and Environmental Resources, which governs the illegal dumping and spreading of coal ash in Puerto Rico.

In addition to disproportionate impacts from the siting of power plants and the “life cycle” of the fossil fuels they burn, the archipelago’s centralized power system relies on risky and inequitable transmission and distribution lines from the rural south to urban areas in the north. Seventy percent of power is generated in the southern coastal region, yet only about 30 percent is consumed there. Furthermore, Jobos Bay communities are often the first to lose electricity and one of the last to regain it, as metropolitan San Juan and other tourist regions are prioritized by the Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority (PREPA). This arrangement provides a material reminder of whose existences are marked as exploitable and expendable and whose lives are valued in the service of capital—in the form of tourism and other business interests. This system also evinces which communities experience energy privilege, and which do not, as this inequitable reality calls attention to how racialization, racism, colorism, income and wealth, geographies, and other factors affect communities differently, including blackouts and toxic exposures (Onís, 2018a; Schneider and Peeples, 2018; Castro-Sitiriche, 2019; Onís, 2021).

Further contributing to this serious problem are damaging energy policy and business agreements. In June 2021, key functions of PREPA, the local power authority, were privatized in a neoliberal, colonial takeover by LUMA Energy. This joint US-Canadian business “collaboration” denies many PREPA employees and union workers possibilities for continuing in their previous positions and increases the existing financial burden that residents pay on their electricity bills. These monthly costs already are two to three times more than the average US household, as ratepayers are forced to finance the power utility’s heavy debt burden and continued reliance on imported fossil fuels, which make up 97 percent of Puerto Rico’s energy mix (US Energy Information Administration, 2020; Conant, 2021; Onís and Lloréns, 2021; Sanzillo, 2021; UTIER, 2021). LUMA is positioned to profit from billions of dollars in FEMA disaster recovery funds to rebuild or “harden” the existing power grid with imported methane gas and more fossil fuel infrastructure. Local attorney and community activist Ruth “Tata” Santiago (2021) argues that the plan is untenable, especially given that “Cambio PR and the Institute for Energy, Economics and Financial Analysis set out a detailed path to achieve 75 percent renewable power generation in 15 years.” Santiago and many other supporters of the Queremos Sol (2020) [We Want Sun] plan are working to transform the entire electric system, by shifting to distributed, onsite rooftop solar installations organized at the local community level, and coupled with battery energy storage systems, power electronics, energy efficiency, literacy, demand response, job creation, and other related programs. This approach would revolutionize Puerto Rico’s current infrastructure and mitigate long-experienced inequitable power realities that are as much about electric power as they are about people power. Financial and political barriers greatly impede this renewable energy alternative and its connections to self-determined environmental and energy justice. Significantly, while women are not the ones typically visible on rooftops for grassroots project installations, they offer essential scaffolding to these and many other projects by sustaining different relationships, often behind the scenes and in less elevated ways—literally and figuratively (Lloréns and Santiago, 2018a; Lloréns, 2021). As local grassroots activists, labor union members, and other outraged residents persist in seeking a different energy present and future, for now, the colonial territory’s electric grid is controlled by LUMA corporate actors who know little about the local power utility, Puerto Rican culture, or the Spanish language, resulting in major communication barriers, power outages and blackouts, and so much more (Onís and Lloréns, 2021).

This complex milieu and its sites of material struggle challenge master and simplistic framings of Puerto Rico’s so-called “natural disasters,” which carry life and death consequences that are bound to the electric power system. During the 2017 hurricanes that pummeled the Antilles and the wave of earthquakes and aftershocks a few years later, the fragile transmission and distribution system and centralized power plants faced major, multi-month disruptions to their operations (Orama-Exclusa, 2020; Santiago et al., 2020a; Santiago et al., 2020b). While these outcomes caused problems for everyone, for those requiring oxygen therapy, dialysis, and chilled medications, the stakes of power loss were especially high. Accordingly, in addition to questioning how “natural” these experiences are, this article resists narratives that reduce climate and other related disruptions only to events, which erase the ways in which acute shocks are inseparable from oppressive everyday stressors (Lloréns et al., 2018; Onís, 2018a; Onís et al., 2020b). These violent and traumatic experiences are not isolated and intertwine with deeply entrenched systems, structures, practices, discourses, stories, tropes, and assumptions of colonialism, neoliberalism, and racial capitalism that are resilient and require dismantling to create different existences and relationalities beyond a damage-centric narrative (Tuck, 2009; Tuck and Yang, 2013; Pulido, 2016a, 2016b; Carillo Rowe and Tuck, 2017; Banerjee and Sowards, 2020; Onís et al., 2021b). Many people and groups in and around Jobos Bay are doing this daily work via grassroots organizing that reclaims “outdoor spaces” for their own communities on their own terms.

To examine and intervene in the energy-related problems and associated inequities and cruelties confronted by people in the Jobos Bay region, attending to environmental and energy justice communication via apoyo mutuo, or autogestión [communal self-reliance], provides one way of framing how grassroots energy actors coexist (García-Quijano and Lloréns, 2017; García-López, 2020). These worldmaking possibilities enact other ways of living beyond and in opposition to state and corporate violence that regularly marginalizes, harms, and suppresses communities in the archipelago, especially defiant individuals and groups. Alternative relational structures and actions are not inherently liberatory, however, if they fail to refuse single-issue politics and avoid vital analyses of intersectionality (Soto Vega and Chávez, 2019). This caution also applies to grassroots energy actor and scholar relationships that engage in translational acts to communicate environmental and energy justice from an anti-colonial perspective. This difficult work involves both co-creating spaces with marginalized individuals who express interest in collaboration to broaden and/or deepen critical understandings and co-conspiring to uproot (or at least to erode) oppressive conditions, systems, and relations. Such a complex process is evident in coalitional organizing in southeastern Puerto Rico.

Members of the Iniciativa de Ecodesarrollo de Bahía de Jobos (IDEBAJO) [Ecodevelopment Initiative of Jobos Bay] organize their actions and relationships using mutual support. Group contributors, and the organizers and ancestors who preceded them, raise awareness about and intervene in urgent environmental and energy problems that implicate corporate polluters, the power utility, the Department of Natural and Environmental Resources, greedy developers, and local and US policies that sicken Jobos Bay communities. Composed of and serving residents from Salinas, Guayama, and other nearby rural municipalities, collaborators know intimately the urgent need for alternatives that advance public health and communal self-determination. Accordingly, IDEBAJO members dedicate their energies to sparking, sustaining, and strengthening educational programming and capacity building for the restoration of natural habitats, including the sustainable use and protection of coastal lands and waters. Their efforts illuminate the shared understanding that caring for various environments creates spaces for and necessitates the exercise of community power (Berman Santana, 1996).

IDEBAJO members communicate their values and vision for the present and future in diverse projects. The group initiated and maintains a radio program turned podcast called Desde el barrio [From the Neighborhood]. For the interviewers and interviewees who make this production possible, their neighborhood consists of physical homes, community centers, schools, parks, boating and fishing areas, mangrove forests, and much more. In these spaces, they coordinate a just hurricane recovery campaign, cultivate community gardens, and organize Construyendo Solidaridad desde el Amor y la Entrega [Building Solidarity through Love and Commitment], a project that involves (re)building homes for unhoused people. Group members also collaborate on smaller actions, exemplified by July 2021 cleanup efforts on the grounds of a now closed school in Aguirre, not far from Guayama. On the group’s Facebook page, one member described the experience as for the “bien común” [“common good”] and “un paso por la esperanza” [“one step for hope”].9 The organization’s collaborators also share their specialized abilities related to vocational trainings, including as electricians and lawyers. For example, in addition to her advocacy and activist work with IDEBAJO, Santiago offers pro bono legal services that involve preparing documents, offering juridical advice, and representing community members or groups in administrative proceedings and in the courts. In exchange, she often receives food (e.g., vegetarian meals, seafood, and fruit) and car maintenance mechanical support. Grassroots organizer Carmen De Jesús, who frequently collaborates with Santiago, reflected on their communal efforts in this way: “En cuanto a la comunidad, diría que estamos encaminándonos a rescatar esos lazos sociales que fueron creados por nuestros antecesores: el ayudarnos, compartir lo que tenemos, preocuparnos por los demás, demostrar amor y empatía.” [“Regarding the community, I would say that we are aiming to rescue our social ties that were created by our ancestors: to help each other, to share what we have, to care about others, to demonstrate love and empathy.”]

IDEBAJO members coordinate with several affiliated groups, including the Comité Diálogo Ambiental [Environmental Dialogue Committee]. In spring 2020, in consultation with Santiago, Dr. Lloréns and I coauthored the “Agua, Aire y Energía Limpia” [“Water, Air, and Clean Energy”] grant proposal. This action was intended to support collaborators’ self-determination for their own community-centered investigations and interests, rather than any academic agendas. While it is important to be critical of the ways in which appealing to grant funding calls and funder dictates can limit liberatory possibilities, considering different ways that scholarly training can be repurposed to contribute to political struggles matters, as does considering situations when applying for and receiving grant money may not always compromise radical reimaginings. In this case, the Comité Diálogo Ambiental drew on the funds to make El poder del pueblo [The Power of the People] documentary, led by local community filmmaker José Luis “Chema” Baerga Aguirre, with associated film screenings and discussions planned. The group also is conducting community science trainings to measure and monitor air, soil, and water quality and is offering technical support for onsite/rooftop solar installations for communities closest to the carbonera.10

Accompanying these efforts, since 2006, Comité Diálogo Ambiental has organized an annual, week-long José “Cheo Blanco” Ortiz Agront Convivencia Ambiental [Environmental Coexistence] camp. The experiences planned and facilitated by organizers exemplify apoyo mutuo, as volunteers, many of whom are women, prepare meals, serve as chaperones, and lead workshops (García-Quijano and Lloréns, 2017; Lloréns and Santiago, 2018b; Alvarado Guzmán, 2019; Onís, 2021). These contributions are key for ensuring the camp is financially accessible to all, which is especially important given pervasive economic injustices in Jobos Bay. Organizers also include local youth who, together with older collaborators, center local ecological knowledges and place-based ways of understanding and valuing language and culture, informed by fishers, elders, artists, technical experts, and other participating community members and guests (see Figure 2). The camp also endeavors to affirm young people’s embodied knowledge(s) and observations about their communities during activities that cultivate spaces for individual and communal self-determination, which I witnessed directly as a volunteer in 2014 and more recently during distanced electronic communication.11 In 2020, the camp was delivered online for the first time in 15 years because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

FIGURE 2. Convivencia Ambiental youth participants and event organizers woke up early for a bird-watching excursion in July 2014. As a material reminder of the Jobos Bay area’s experiences with exploitation and dispossession, the Aguirre sugar mill ruins persist in the background. Image credit: Catalina M. de Onís.

Whether in person or virtual, the space-making generated by Convivencia Ambiental organizers and participants marks a significant alternative to a system that regularly devalues “non-expert” local knowledges and threatens community member well-being and survival. Furthermore, the camp challenges colonial and consumerist understandings of “the outdoors.” As a radical rejection of this orientation, these young energy actors experience coexistence, interdependence, agency, and community building beyond dominant preservation, conservation, and sustainability discourses and the constraints of racial capitalism. Together, organizers refuse constrictive narratives of the outdoors that exclude, discipline, and erase how different people and groups coexist in these spaces, including by advancing political struggle and change. Thus, Convivencia Ambiental calls attention to and creates literal and figurative spaces for learning, advocacy, and resistance for collective action.

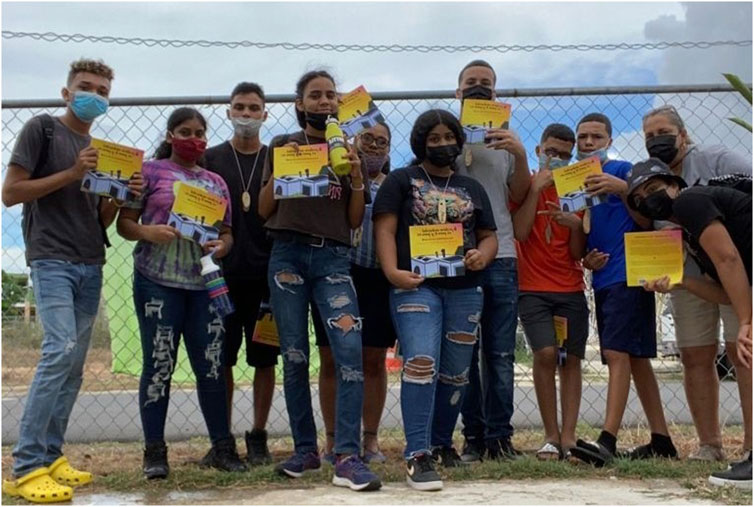

In 2021, camp programming returned to in-person events, coordinated by determined young organizers who wanted to ensure opportunities for local youth continued, during the pandemic. Among a host of activities, including being interviewed for the Desde el barrio podcast, Convivencia Ambiental energy actors received and read the bilingual children’s book La justicia ambiental es para ti y para mí/Environmental Justice Is for You and Me.12 This collaborative project narrates experiences with environmental in/justice in Jobos Bay communities for young people and provides a case study for communicating the intersection of energy, community power, environmental racism, and “outdoor spaces” (see Figure 3).

FIGURE 3. Convivencia Ambiental organizers, including Yaminette Rodríguez (second from right), incorporated La justicia ambiental es para ti y para mí/Environmental Justice Is for You and Me into 2021 programming to resonate with the theme “En nuestro planeta interconectado sobrevivimos junt@s” [“On our interconnected planet we survive together”]. This photo was taken in Coquí, Salinas, Puerto Rico. Image credit: Ruth Santiago, Yaminette Rodríguez, and Gerardo Cruz Pedragon.

In Puerto Rico, communicating different experiences often is constrained by English monolingualism and US cultural assumptions that function as powerful symbols and tools of white supremacy, coloniality, and racial capitalism (Onís, 2015; Onís, 2016; Sowards, 2019). For anti-colonial methods and praxis, “rethinking how research is conducted in non-white, non-English language, non-dominant cultures is one way to advance environmental justice, particularly through engaged scholarship that includes deliberation, participation, and decolonization” (Banerjee and Sowards, 2020, p. 4). Given that Jobos Bay residents are mixed-race, Afro-descendant, Spanish speaking, economically oppressed, and from marginalized rural and coastal areas, this article contributes to this “rethinking” of environmental justice research, which also carries strong implications for energy justice theories, methods, and practices. These concerns and actions are inseparable from translating racialization and racism that shape and are shaped by various spaces that complicate “the outdoors.” In addition to literal acts of translation between different languages (e.g., Spanish and English) and more figurative ones (e.g., communicating concepts in accessible ways to different audiences), translation also can function “as an epistemological device with the potential of fostering the constitution of spaces for civic action to thrive” (Castro-Sotomayor, 2019, p. 2). As the previous section explained, one way in which this civic action for anti-colonial environmental and energy justice may transpire is by drawing on mutual support networks to reach, learn from, and collaborate with other energy actors and groups. These relational efforts occur in a variety of spaces, including on community center grounds where air pollution is visible and disrupts healthy respiration, during a summer camp that cultivates socio-ecological consciousness and action for and by local youth, and even in the pages of a children’s book that narrates the activism of student energy actors to encourage their peers and younger generations to join in struggle.

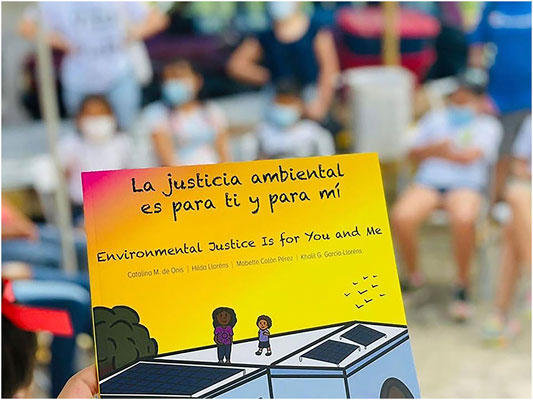

La justicia ambiental es para ti y para mí/Environmental Justice Is for You and Me is a bilingual Spanish- and English-language text that was written during 2020–2021. Dr. Hilda Lloréns, Mabette Colón Pérez, whose perspective is documented in this article’s epigraph, and Dr. Lloréns’s son and middle-schooler Khalil G. García-Lloréns joined me in writing this children’s book. Colón Pérez also illustrated various locations and experiences in and around Jobos Bay to accompany her “ecotestimonio” of growing up near the coal plant (Tarin, 2019). My coauthors and I translated this testimony for a younger audience and then integrated the material into a section called “La historia de Mabette” [“Mabette’s Story”] to constitute the book’s core. Surrounding this section, the text presents information about the socio-ecological context, provides definitions, and invites young readers, using “you” language, to think about how the book relates to them. To do so, La justicia ambiental es para ti y para mí describes how the environmental justice movement discourse and frame take shape in Puerto Rico-based struggles against the AES coal plant and features Colón Pérez’s experiences of enjoying Jobos Bay’s beauty in her younger years. However, because of the coal plant, as she grew older, she no longer could swim or fish with her relatives because of the polluted water. Colón Pérez describes how her neighbors became sick, which motivated her to join a local group and to raise her voice, which later informed her involvement with the Convivencia Ambiental camp. In addition to those living in her area of southeastern Puerto Rico, the book also tries to reach youth throughout the world who speak/read Spanish and/or English and who are interested in learning about environmental justice and advocating for their own communities (see Figures 4, 5).

FIGURE 4. La justicia ambiental es para ti y para mí book cover depicts the importance of learning about, installing, and maintaining distributed solar power, as energy actors, including young community members, literally take this power into their own hands. Image credit: Andrea Ruiz Sorrentini.

FIGURE 5. Youth participants in Puerto Rico’s Aula en la Montaña program read and discussed the book in September 2021 to commemorate International Literacy Day. University of Puerto Rico Professor Sandra Soto Santiago (left back corner) co-organized the event (https://www.portal.editoraemergente.com/colaboraciones/). Image credit: Sandra Soto Santiago.

After the main text concludes, the book provides a glossary of relevant terms and selections from the 17 Principles of Environmental Justice.13 Members of the First National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit drafted these priorities in October 1991 in Washington, D.C. Thirty years since their writing, these principles continue to guide many aspects of the environmental justice movement, which extends beyond US continental and colonial borders. In this section, my coauthors and I chose to highlight specific environmental justice principles that we thought were especially relevant for young people, including “the education of present and future generations which emphasizes social and environmental issues, based on our experience and an appreciation of our diverse cultural perspectives” (Onís et al., 2021a, p. 50). As just one example of why engaging interconnected ecological and cultural differences matters, the book features an illustration of students on their way to school, passing by mangroves (see Figure 6). Literally, on the frontlines of climate disruption, these coastal forests are jeopardized by the same unsustainable, lethal systems that threaten the human and more-than-human communities they protect (García-Quijano et al., 2015).

FIGURE 6. Mangroves are a vital part of Puerto Rico’s coastal ecosystem. Convivencia Ambiental participants experience different activities that honor these life-giving and -sustaining forests that store carbon and help to mitigate erosion and sea-level rise. In 2017, organizers centered these vital structures in the theme “Mi comunidad entre las raíces del manglar” [“My community among the roots of the mangrove forest”]. Image credit: Mabette Colón Pérez and Editora Educación Emergente.

In crafting this book and its components, my coauthors and I embodied the role of translators, as we moved between different linguistic and material, and digital spaces to amplify conversations and actions for environmental and energy justice. Sensing the urgency of worsening environmental degradation and climate disruption and the associated disproportionate impacts, we confronted the challenge of addressing young people in accessible ways, such as communicating the complicated topics of injustice and pollution in multiple languages. This translational work informed our multipronged efforts to reach researchers, teachers, students, and others who find the Spanish and/or English languages accessible, as well as to reach the most-impacted community members, whose stories and struggles constituted the exigency for this book project. As part of the “Otra escuela” [“Another School”] series, Puerto Rican publisher Editora Educación Emergente published the e-book for no-cost download on its website (https://www.editoraemergente.com/en/home/122-environmental-justice-is-for-you-and-me.html). Editor Dr. Lissette Rolón Collazo also worked with my coauthors and me to produce paperback copies of the book for purchase online, with all royalties to be donated to Convivencia Ambiental (https://www.editoraemergente.com/es/inicio/125-la-justicia-ambiental-es-para-ti-y-para-mi.html). Based on conversations about distribution, Dr. Rolón Collazo sent 40 book copies to Santiago, a Convivencia Ambiental camp coordinator, to incorporate into programming and for wider sharing. Additionally, accompanying numerous other dissemination efforts, I coordinated with the editor to have one dozen books sent to Vieques, a municipality east of Puerto Rico’s largest island, for presentations and distribution to local elementary schools. To increase online access, a link to the children’s book is included on El poder del pueblo [The Power of the People] website (https://elpoderdelpueblo.com). In consultation with IDEBAJO and Comité Diálogo Ambiental members, I created this resource hub, which includes a Convivencia Ambiental 2019 video, composed by IDEBAJO member Alvarado Guzmán (mentioned in this article’s introduction), information about a community-produced documentary on the carbonera and distributed rooftop solar, various virtual panel recordings, and articles and books about grassroots struggles in Jobos Bay communities. Exemplified by this public-facing communication, in some situations, it may be best to offer non-research creative energies, when scholarship, including on-site field research, might not be what is needed most by communities.14

Thinking about and practicing alternative collaborations between grassroots energy actors and scholars is vital work for communicating and experiencing coexistence in shared and distinct spaces. Such attention creates openings for and may necessitate coalition that can be experienced electronically in what I call “e-advocacy.” This method involves “maintaining ties and coalitional solidarities across time and space that extends the field” (Onís, 2021, p. 21). As with in-person interactions, this collaborative concept and practice, which takes form in distanced digital and virtual exchanges, provide both possibilities and pitfalls in particular contexts.15 In the case of the children’s book, adapting to authors’ preferred communication modes (e.g., email, Facebook messaging, WhatsApp, and phone texts) and navigating different time zones and electric power disruptions amid competing responsibilities are just a few examples of e-advocacy negotiations that my Puerto Rican coauthors and I experienced in our different locations in the archipelago and in the US diaspora during the pandemic. These e-advocacy reflections encourage an archipelagic understanding that is both literal and figurative, as individuals interested in examining race/racism/racialization and “the outdoors” can study material archipelagoes as well as metaphoric archipelagic formations, bridging different communities together in coalitional acts (Reyes-Santos, 2015; Onís, 2021). This archipelagic thinking and relating also can involve combining multiple disciplinary and other knowledges (Stephens and Martínez-San Miguel, 2020).

To enact this archipelagic-diasporic collaboration, making the children’s book required interdisciplinary and intergenerational energies. Though creating a text that communicated environmental justice struggles in Puerto Rico to young readers grew from an idea I had held for some time, my coauthors transformed this project in ways that far exceeded my initial hopes for the book’s creation and its potential circulation and reception. To co-generate La justicia ambiental es para ti y para mí, Dr. Lloréns, an anthropologist, and I drew on our knowledges of audience adaptation and interdisciplinary understandings of Latina/o/x and Puerto Rican studies, environmental and energy justice studies, ethnography, and narratives, while shifting attention from our well-established practice of writing for adults to coauthor with and center young people as the primary audience. Dr. Lloréns’s experience as a parent and reader of many children’s books was very helpful for revising the initial draft to make it accessible to young readers. This feedback, in close consultation with her son, García-Lloréns, included bolding certain terms and sentences for emphasis, simplifying language, reducing the amount of content per page, and adding a glossary. Similarly, Colón Pérez offered key contributions that resonated with the communication studies concepts of voice, storytelling, and visual rhetoric. These indispensable offerings constituted much of the book’s content. Together, my coauthors offered me—someone who does not often read to children—an opportunity to think more critically about content and form in relation to different audiences.

The collaborative process that resulted in La justicia ambiental es para ti y para mí required moving outside of familiar writing spaces and revealed that such a deviation carries the potential for informing and (re)shaping how scholars translate ideas. While the children’s book implicitly tells a story of energy justice struggles, introducing this movement frame and discourse, in addition to environmental justice, likely would have overwhelmed a single project directed toward a young audience. However, I emphasize both environmental and energy justice in this article because of the importance of these overlapping and different movement frames and discourses for assisting academic and other concerned audiences with understanding lived experiences in Jobos Bay communities. For this essay and its interest in joining critical conversations about communication, race/racism/racialization, and “outdoor spaces,” to engage one concept without the other would have presented an incomplete account, given grassroots activism and existing scholarship about these efforts that highlight entwined self-determination struggles. By interweaving environmental and energy justice throughout this article, I hope that communicating the latter movement frame and discourse may be thought-provoking for many readers. Ultimately, the process of writing and reflecting on this children’s book illuminated constraints that I often have struggled with when translating my research for both academic and popular press audiences: weighing the dis/advantages of introducing and explaining fewer concepts and arguments, while also considering how excluding certain terms and ideas may reduce a project’s contributions and impact.

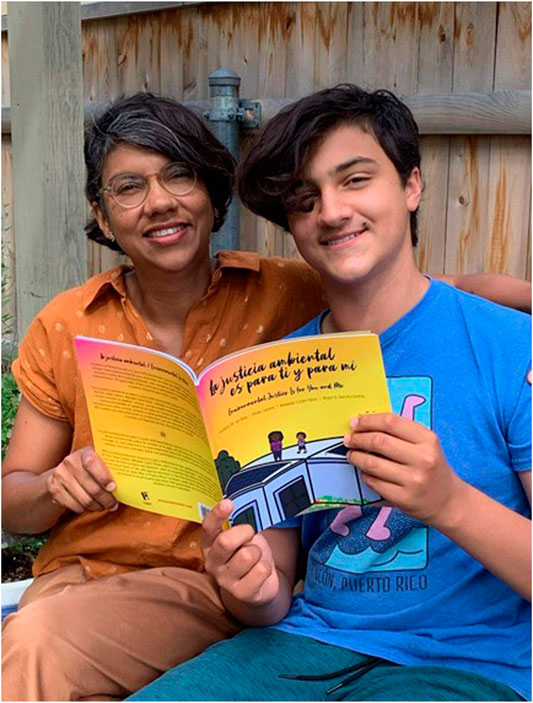

Accompanying my thoughts about this project, I include the perspectives of Colón Pérez, García-Lloréns, and Dr. Lloréns, whose collaborative energies made this bilingual book possible (see Figures 7, 8). Their reflections demonstrate the importance of applied, public-facing communication that seeks to increase environmental justice awareness and action.

FIGURE 7. Mabette Colón Pérez spent many hours making the illustrations for the children’s book and already has read the text to Arizbeth, who she is expecting in Fall 2021. Image credit: Margarita Pérez.

FIGURE 8. Dr. Hilda Lloréns and her son, Khalil, share the material result of their familial book project. Image credit: Carlos G. García-Quijano.

The reason I wanted to work on this project was to spread the message to children. I hope that my images can express what happened in my community and that they can understand in a clear way the importance of environmental conservation. The part that I enjoyed most about the process was creating images for each page and the cover… I hope that this raises awareness about our natural resources and the importance of always caring for them.

-Mabette Colón Pérez16

I wanted to participate in this project because I felt that more children around the world and in the United States specifically needed to know about the environmental injustices going on in some of the places they call home. Before taking part in the writing of this book I had very little knowledge of Mabette’s story, and I found her story a great inspiration for myself and I enjoyed translating her story into child-friendly language. I hope that readers will learn about what they can do to stop environmental injustice from happening in their communities and to feel empowered to speak out about environmental injustices.

-Khalil G. García-Lloréns

I wanted to work on making knowledge about environmental justice and the importance of safe keeping the environment and the planet accessible to younger readers. For me, the most enjoyable aspects of the project were working collectively and cross-generationally in telling this important story. I hope readers learn about environmental threats facing our communities and that they become informed and empowered to act for environmental justice in small and big ways! I hope that this librito [little book] is a beacon of light in the greater fight to achieve environmental justice.

-Dr. Hilda Lloréns

These coauthor reflections reveal the themes of caring for environments; working within and across generations for co-learning; inspiring collective environmental justice actions, especially among young people; and translating. Together, these areas mark key spaces for continuing to communicate the high stakes of these struggles for livable and flourishing communities.

In addition to including what the book coauthors experienced and their hopes for the project’s potential impacts, it matters to consider how others not directly involved with the book’s writing view its offerings. When asked about the significance of this bilingual children’s publication, Santiago reflected:

The transformation of the energy system in Puerto Rico requires a new way of thinking and envisioning how we produce, transport, modify, consume, and relate to power. People and communities need to see themselves as active participants in energy issues, not just passive consumers. Changing views, perspectives, roles, hearts, minds, the whole culture around energy necessitates a wide array of approaches. Educating about energy issues is paramount. La justicia ambiental es para ti y para mí bilingual children’s book is a creative contribution to the vital educational process that needs to happen to reach all audiences and the public… Reading Mabette’s story about the terrible impacts of the coal-fired power plant close to her community will help others understand why it’s so important to end fossil combustion to generate energy. The children’s book will help youngsters and their families, teachers, and other community members to grow their empathy and solidarity with the communities that centralized, fossil-fired generation overburden.

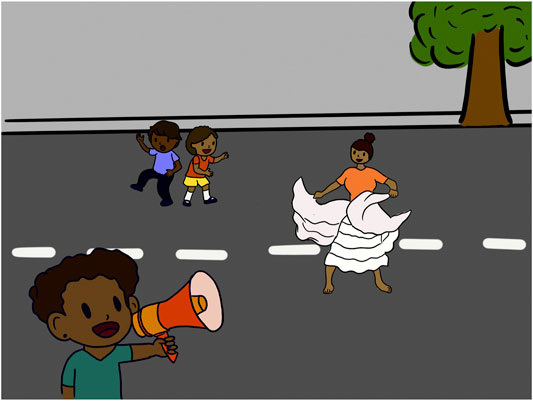

The issues, concerns, and possibilities raised by Santiago encourage younger community members to exercise their potential for advancing the well-being of their communities, which is constituted by both electric and people power in varied spaces. Urging these actions challenges corporate polluters, corrupt government officials, and other enablers who treat Puerto Rico, especially its coastal regions, as a site of exploitation and a playground for the rich. La justicia ambiental es para ti y para mí insists on a different future, one where children and those who support them push back at the poisoning of their communities to reclaim their places of play, protest, and so much more (see Figure 9).

FIGURE 9. Dance, music, resistance, and community endurance long have been co-constitutive in Puerto Rico. Image credit: Mabette Colón Pérez and Editora Educación Emergente.

This article chronicles how grassroots mobilizations among IDEBAJO and Comité Diálogo Ambiental members and their coalitional partners work to transform energy infrastructure and hierarchical power dynamics to radically rethink, communicate, and enact different relationships with energy and power in various spaces. By understanding environmental and energy justice as a form of mutual support that is inseparable from the capacious concepts of power and energy, this article builds a case for Puerto Rican environmental and energy communication studies. Focusing on Puerto Rico is important for evincing the resilient entangled roles of imported fossil fuel dependency, economic and climate injustices, environmental racism, ecocide, US colonialism and imperialism, neoliberalism, and racial capitalism that threaten individual and communal well-being. In response to these oppressive systems, structures, and practices, many energy actors seek alternatives rooted in coexisting with and caring for multiple spaces beyond “mainland,” English-speaking contexts. Colón Pérez’s and other residents’ stories of survival, persistence, transgression, and alternative constructions provide crucial counternarratives of how power, energy, and all the relations they constitute take shape from the coastal, intertidal ground up. Centering these powerful stories and embodied, emplaced experiences, this article featured the making and sharing of an environmental justice bilingual children’s book as an exemplar of one of the many ways scholars can contribute to anti-colonial environmental and energy justice communication, particularly by joining efforts to create educational spaces that also encourage spaces for action. While this process is different from direct, on-the-ground (or in-a-boat) contributions, the children’s book offers a form of e-advocacy that connects with and seeks to support grassroots organizing. Recording, translating, and circulating different stories is one way that “Seguimos en la lucha” (“We continue in the struggle”), as Santiago shared in a winter 2021 email exchange with several Puerto Rico and US diasporic group members.

This discussion section offers some critical reflections on what this collective action entails and the obstacles and opportunities for such work. I highlight the challenging and remotivating aspects of this project in the hope that these offerings might create space for additional conversations and continued exertions that respond to the urgent colliding crises that are inextricable from studies of racial ecologies and “communication, race, and outdoor spaces.” Though these concluding ideas could be marked thematically and numerically for clarity, the material that follows takes a fluid form to reflect the interconnected nature of archipelagic spaces and places that enliven this essay.

Attending to the complexities of energy and power can motivate collaborative work across many years and miles that approach grassroots energy actor and scholar relations as potentially coalitional spaces. This labor involves looking toward the coalitional “horizon of possibility” that is mutable, fluid, and temporally and spatially uncertain (Lugones, 2003; Chávez, 2013, p. 8). Much like how apoyo mutuo can enact relationalities of communal care, interconnection, and struggle, so too can grassroots energy actor and scholar collaborations. That written, the framing of “grassroots energy actor and scholar” used in this essay risks overlooking and oversimplifying how people may hold multiple roles and responsibilities related to and exceeding research. For example, community members who energize grassroots movements are knowledge creators, sharers, and keepers, who know their lived experiences better than anyone else, while scholars might simultaneously generate content for peer-reviewed journals and apply some of the insights they write and teach about to engage in direct political struggle as energy actors. Furthermore, some researchers who center environmental and energy justice topics in their intellectual and other work are members of the same communities in which they conduct their studies (Bullard, 2014; Onís and Pezzullo, 2017; Lloréns and Santiago, 2018a; Marrero, 2021). Exemplifying these multiple roles, Abrania Marrero (2021), who was born in Puerto Rico and trained in nutritional epidemiology and biostatistics in the United States, works in her rural Puerto Rican community to reclaim agricultural practices and spaces for decolonial food relations. She insists that communities already “had been living—thriving, really—in kinship and in the forest long before any white-savior scientist came to document their plight.” Marrero (2021) continues: “Knowledge generation must be in the hands of those whose lives are at stake. As researchers, we must learn that power already exists among the marginalized. We do not ‘empower’—we help activate and advocate for the un-suppression of that power.” This un-suppression necessitates approaches that challenge oppressive relationships rooted in stubborn logics and discourses, narratives, tropes, and other rhetorical materials of conquest.17

This article joins anti-colonial and decolonial studies scholars who refuse knowledge creation and dissemination that advances empire’s unquenchable, expansive desire for more, represented by universities and disciplines that actively contribute to the settler colonial project and empire building (Tuck and Yang, 2013; Lee and Ahtone, 2020; Lechuga, 2021). This entanglement is apparent in extractivist knowledge production in everyday and acute crisis contexts (Garriga-López, 2020). In acts of refusal, scholars can work with communities that agree to collaborations by confronting systemic problems to locate and contribute to dismantling systems of power, while also engaging in collective action for “resistance, reclaiming, recovery, reciprocity, repatriation, [and] regeneration” to cultivate a “relationship of repair” (Tuck and Yang, 2013, p. 244; Ybarra, 2018, p. 28). Anti-colonial methods and praxis place marginalized community member interests and struggles first, as these individuals make critical engagements possible, and they can be harmed in the process (Madison, 2012; Smith, 2012; Onís, 2016; Ybarra, 2019; Onís, 2021). Even when scholars and local group collaborators align ideologically and share relational affinities, researchers, practitioners, grassroots group members, and other energy actors must consider what can go well and wrong, and for whom. One risk of coalitional work is that those involved might neglect to reflect on their own participation in contributing to oppressive relations and structures, including about race (Chávez, 2021). Thus, delving deeply into the many manifestations and functions of racism and racialization—at different levels, ranging from interpersonal to institutional—is imperative for scholars interested in master and marginalized communicative constructions of outdoor and other spaces. This attention often requires significant amounts of extra labor, resistance, and patience to do coalitional work that ethically contributes to anti-colonial environmental and energy justice communication.

Ways of relating otherwise are undervalued in official measures of academic “productivity” and/or disciplined by the academy. To illustrate, for the children’s book to be categorized by my university as “research,” I knew that publishing a peer-reviewed article, rather than asking for the book to be treated as its own intellectual project, was required for the text to “count” beyond service. This reality exists even though Dr. Lloréns and I applied our intellectual and other energies in ways that were no less challenging than what tends to be recognized by universities as “academic” work (e.g., peer-reviewed articles and books published by university and other presses). This labor certainly was different from more accepted and expected forms of research and publication, but that does not make the text less relevant. In fact, this project resulted in far greater interest from different publics than my previous forms of academic and popular press writing, which suggests the importance of rethinking and contesting constraining systems and structures that limit the ways that scholars do work in the world “to ensure… multiple opportunities to be curious, or to make meaning in life” (Tuck and Yang, 2013, p. 237; Ybarra, 2019). Translation emerges as a key practice for navigating these limitations and possibilities. Describing work done in one space in another space is necessary to make work “legible” for different audiences in neoliberal universities and departments, while also working to break (from) such structures and the discourses and other rhetorical materials that uphold them. The fact remains, however, that scholars can exhaust their energy supplies, especially when existing in a system that actively works against alternative, liberatory worldmaking. These academic spaces, structures, and norms paradoxically spotlight (for superficial “diversity and inclusion” purposes), discipline, and devalue translation labor. For some of us, confronting this treatment epitomizes our daily struggles to survive in the academy, while trying to make space for life-giving projects and relationships that are shaped profoundly by translation in multilingual and other spaces (Onís, 2015; Castro-Sotomayor, 2019; Sowards, 2019; Maldonado, 2020; Martínez Guillem, 2021).

Translational acts constituting collaborative work also may be impacted by financial realities that enable and constrain possibilities for communicating messages with different individuals and groups. Working with a Puerto Rican press to publish La justicia ambiental es para ti y para mí resulted in greater promotional support and thus more (free) downloads than if the text had been self-published, which was the initial plan. However, this formal e-publishing approach cost several hundred dollars. Given that many people in Puerto Rico and the United States requested paperback copies, including for libraries, the printed alternative to the e-version also cost several hundred dollars, as did the purchasing and mailing of book copies for distribution and educational programs in various locations. Additionally, some of the coauthors drew on personal funds to ensure that the Puerto Rico-based artist and storyteller (Colón Pérez) could be paid for her labor. Without university funding support, the book’s formal publication—both in digital and paperback form—would have taken far longer and might not have been realized. Thus, individuals interested in doing similar work would be wise to consider financial realities and how to make decisions in specific situations that address accessibility and other interrelated concerns.

While this article has stressed the importance of translating grassroots organizing and people power, studying how the environmental and energy justice frames and discourses are coopted in institutional spaces also is important for mapping complex, competing, and complementary power struggles. For example, in 2021, the US Department of Energy declared energy justice a priority, while the White House created the Environmental Justice Advisory Council to address environmental racism, the climate crisis, and disproportionate impacts (The White House, 2021a; Dept. of Energy, 2021). Notably, Santiago is a member of this council. Her selection offered many IDEBAJO and Comité Diálogo Ambiental members and others struggling for livable, just relations hope that Puerto Rico’s urgent, colliding crises might receive some attention and tangible support.18 That written, as these movement frames and discourses become institutionalized and appropriated in policy agenda setting, concerned energy actors should be wary of how this increased language traction and circulation is functioning and for whom. Many scholars have troubled how the state’s inclusionary efforts maintain existing power relations and systems, while continuing to dispossess, discipline, cage, poison, and murder the most marginalized and subjugated people (Cacho, 2012; Pulido, 2016b; Pellow, 2018, 2020). Thus, attending to the many spaces in which environmental and energy justice terminology circulates and how these movement frames and discourses are translated, by whom, and with what consequences marks an urgent area for analysis, critique, and other actions.

The fluid reflections composing this final section implicate space-making in multiple ways and seek to resonate with and challenge oppressive conceptions of communicating race/racism/racialization in “the outdoors.” As with other places on Earth, these expressive acts continue to carry high stakes in Puerto Rico. In summer 2021, the US House Natural Resources Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations held a hearing on how to proceed with the AES coal plant. Both LUMA Energy and AES representatives refused to attend. With their absence and ongoing exploitative actions, industry members and crony capitalist politicians continue to enable the coal plant “plaga” described by Colón Pérez in this essay’s opening. However, these abuses are not left unchallenged. For example, in testimony materials for the hearing, grassroots members insisted that full remediation of the plant site and many other contaminated areas must occur along with providing reparations to community members. Given that remediation can cause fugitive coal ash dust, “cleanup” will not be easy in any sense of the word. And yet, although IDEBAJO and Comité Diálogo Ambiental collaborators and other coalitional partners are tired, and although many grassroots energy actors and their neighbors are sick, they continue to do what they always have done when met with forces that seem insurmountable. Residents gather, share stories, provide mutual support, build coalitions, and plan uncompromising alternatives. In doing so, Jobos Bay community advocates and activists tenaciously continue “en la lucha” for self-determined environmental and energy justice.

The content for this article was gathered and analyzed by the author and is informed by previous research that follows IRB conditions for access.

The legal guardians/next of kin of photographed minors signed media release forms for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data, which were provided by and submitted to adult organizers of the youth educational events described in this article.

The author confirms that she wrote this article. However, the collaborative energies of many contributors inspire this essay, as described in Acknowledgments.

The University of Colorado Denver financially supported parts of this research project, including publishing costs and purchasing copies of the children’s book for distributing and educational programming in and beyond Puerto Rico.

The author collaborates with the southeastern Puerto Rico grassroots groups featured in this article. Echoing critiques by other anti-colonial scholars, conflict of interest statements often function to uphold whiteness, a structure, ideology, and discursive space that this journal’s special research topic engages and that this article challenges. Thank you to Professor Mohan J. Dutta for making this problem visible in a summer 2021 Facebook post.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Though my name is listed as the author, this article has many coauthors. Thank you to Dr. Hilda Lloréns, Mabette Colón Pérez, and Khalil G. García-Lloréns for working with me on the children’s book described in this essay and for generously sharing their reflections on the experience. Our intergenerational collaboration made for a joy-filled and life-giving project. I especially appreciate Colón Pérez’s artistic and other communicative energies throughout the book’s creation. Colón Pérez, Dr. Lloréns, and Ruth “Tata” Santiago provided images and helpful comments on this essay, further contributing to their immeasurable support over the years. Editora Educación Emergente editors Dr. Lissette Rolón Collazo and Dr. Beatriz Llenín-Figueroa were enthusiastic partners during the book’s production and promotion process, and it has been an honor to collaborate with this Puerto Rican publisher. Also key for supporting the children’s book and this article, Michelle A. Médal patiently coordinated numerous funding logistics. I also thank Nitza M. Hernández-López, Jocelyn Géliga Vargas, Mariana Teresa Hernández, Yaminette Rodríguez, Gerardo Cruz Pedragon, Carlos G. García-Quijano, Margarita Pérez, Carmen De Jesús, Sandra Soto Santiago, Andrea Ruiz Sorrentini, and Adneris Hernández Rivera for contributing to this article. Thanks to the “Communication, Race, and Outdoor Spaces” topic editors, especially Drs. Carlos A. Tarin, Jen Schneider, and Peter K. Bsumek, and to the reviewers for their smart comments to improve this essay. This article is dedicated to Arizbeth Soto Colón and to all of Puerto Rico’s young people and other youth throughout the world who are dreaming of and developing alternative futures by taking power into their own hands to build more livable, just, and sustainable communities.

1Alvarado Guzmán, V. (2020, Apr. 22). Más letal el coronavirus en residentes expuestos a la contaminación de la planta de carbón en Guayama, El Patriota del Sur (blog). Available at: https://elpatriotadelsur.blogspot.com/2020/04/mas-letal-el-coronavirus-en-residentes.html?m=1.

2Following Holling and Calafell (2011), I avoid signaling out Spanish words in this essay by maintaining regular font, rather than using italics. I provide English-language translations in brackets.

3Like environmental and climate justice, energy justice research stems from movement organizing that centers the disproportionate impacts caused by an extractivist economy and other interrelated concerns that harm the lived experiences of Black, Indigenous, and other People of Color, as well as low-income and low-wealth communities. This movement, frame, and discourse engages global and regional climate disruption, energy poverty, the fossil fuel and renewable energy industries, decarbonization, decentralization (i.e., changing from centralized, large infrastructure to distributed, small systems and creating horizontal forms of people power), democratization via direct participation, and decolonization. These final four concepts and practices—decarbonization, decentralization, democratization, and decolonization—are indispensable components of energy justice in Puerto Rico. Accordingly, they should be struggled for simultaneously “to avoid reaffirming oppressive power dynamics that benefit from isolating and overlooking other entwined concepts and practices” (Onís, 2021, p. 55–56).

4The Florida area targeted for receiving the Guayama plant’s coal ash, Osceola County, is one of the fastest-growing places for Puerto Ricans in the United States, many of whom left the archipelago following Hurricanes Irma and María (Calma, 2019). For a more thorough discussion of AES and resistance to this facility and its operations, consult the University of California Press webpage for my book, Energy Islands: Metaphors of Power, Extractivism, and Justice in Puerto Rico, which provides a downloadable portion of the introduction: https://www.ucpress.edu/book/9780520380622/energy-islands.