95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

CONCEPTUAL ANALYSIS article

Front. Commun. , 03 September 2021

Sec. Culture and Communication

Volume 6 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2021.705142

This article is part of the Research Topic Songs and Signs: Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Cultural Transmission and Inheritance in Human and Nonhuman Animals View all 20 articles

Intra- and inter-generational family singing is found throughout the world’s cultures. Children’s songs across many traditions are often performed with adult family members, whether simultaneously (in unison or harmony) or sequentially (as in call-and-response). In one corpus of printed children’s songs, however, such musical partnering between young and old was scripted, arguably for the first time. Children’s periodicals and readers in late eighteenth-century Germany offered a variety of poems, theatricals, riddles, songs, stories, and non-fiction content, all promoting norms around filial obedience, virtue, and productivity. Readers were encouraged to share and read aloud with members of their extended families. But the “disciplining” going on in this literature was as much emotional as it was moral. Melodramatic plots to dialogues, plays, and Singspiele allowed for tenderness and affection to be role-played in the family drawing room. And the poems and songs included in and spun off from these periodicals constituted, for the first time, a shared repertoire meant to be sung and played by young and old together. Duets for brothers and sisters, parents and children—with such prescriptive titles as “Brotherly Harmony” and “Song from a Young Girl to Her Father, On the Presentation of a Little Rosebud”—not only trained children how to be ideal sons, daughters, and siblings. They also habituated mothers and fathers to the new culture of sentimental, devoted parenthood. In exploring songs for family members to sing together in German juvenile print culture from 1700 to 1800, I uncover the reciprocal learning implied in text, music, and the act of performance itself, as adults and children alike rehearsed the devoted bourgeois nuclear family.

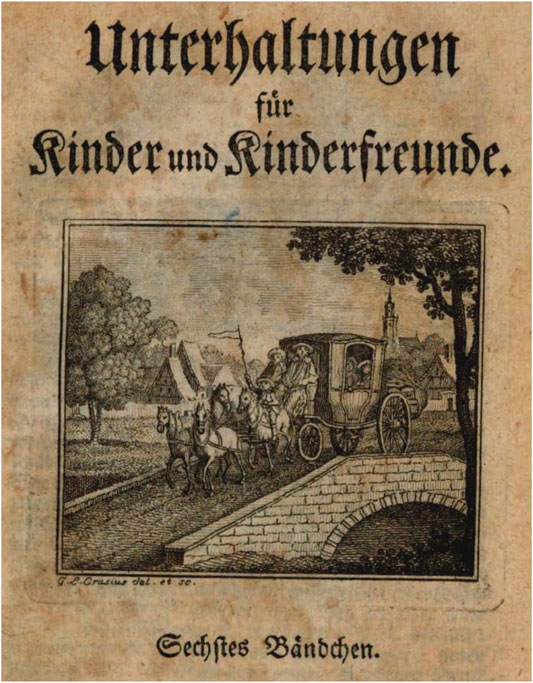

In 1783, the author and pedagogue Christian Gotthilf Salzmann gave over an entire volume of his children’s periodical Unterhaltungen für Kinder und Kinderfreunde (Entertainments for Children and Children’s Friends, 1783:6) to an account of his family’s 5-day “road trip” from Dessau to Erfurt, in Thuringia. Thuringia is where Salzmann—a teacher at the innovative Dessau-based educational institution the Philanthropinum—was born and raised. He longed to bring his family back to his Vaterland to visit their grandmother. The title-page illustration to the volume shows the family in a coach and four crossing a bridge, as though just leaving Dessau at their journey’s outset. A man and woman sit on the coach box, while two children peek out from the coach window, and a young boy rides one of the horses while waving a flag (Figure 1). The boy’s excitement at the adventure to come is palpable, and this illustration would have prompted a similar excitement in the periodical’s readers as they “joined” the seven Salzmann children, their parents, their coachman, and their maid on the journey. “Let’s go to Erfurt! Let’s go to Grandmother!” the children cry (5).

FIGURE 1. Title page, Salzmann, Unterhaltungen für Kinder und Kinderfreunde, vol. 6 (Leipzig, 1783), detail. Courtesy of Bayerische Staatsbibliothek München, shelfmark Paed.pr. 2984-5/6, urn:nbn:de:bvb:12-bsb10760929-8.

But travel in eighteenth-century Germany was uncomfortable, dangerous, even life-threatening, compounding an already-high infant and child mortality rate in eighteenth-century Europe of 25–40% (Volk and Atkinson, 2013). And Salzmann chose to undertake this journey in March, before winter was past. On the third day, the family meets with a snowy wind and icy path that slows down their horses. Everyone is freezing. Salzmann begins to hear the children whimper at the cold, which he describes as the only kind of travel hazard for which he has no tolerance. “Truly, my friends,” he warns his readers, “if one of you wishes to travel with me one day, you have to promise me (not to complain); otherwise, as soon as you start crying over things that cannot be changed, I will jump out of the coach and let you drive on alone” (55). Luckily, his wife finds a way to restore the peace and “open those mouths that were about to freeze over.” She begins to sing the Lied “Rosen auf den Weg gestreut” (Roses Strewn Upon the Path), a 1776 poem by Ludwig Christoph Heinrich Hölty that had been set by Johann Friedrich Reichardt in his 1779 collection Oden und Lieder as “Lebenspflichten” (Duties of Life) (Figure 2). Salzmann describes the family joining in, while he “sang the bass line from my coach box. Thus we forgot the cold and hardship, and sang until we came to Buttstädt” (55).

FIGURE 2. Reichardt, “Lebenspflichten” (text: Hölty), from Oden und Lieder (volume 10) (Berlin, 1779).

Readers encountering the off-set text at this point in the volume might have found themselves singing along with the shivering Salzmann family. After all, Hölty’s poem was well-known, while Reichardt’s Oden und Lieder was already a popular song collection.

Rosen auf den Weg gestreut! Roses strewn upon the path!

Und des Harms vergessen! And forget all harm!

Eine kleine Spanne Zeit Only a small span of time

Ward uns zugemessen. Was granted to us.

Heute hüpft im Frühlingstanz Today the happy boy

Noch der frohe Knabe; Still leaps in the spring dance;

Morgen weht der Todtenkranz Tomorrow the funeral wreath

Schon auf seinem Grabe. Will already waft over his grave.

(Reichardt, 1779, 16).

It is a strange song for the mother to have chosen to comfort and distract the children, painting a somber picture of fleeting youth and life. Over eight quatrains, a boy’s spring dance gives way to a funeral wreath upon his grave; a young bride’s path to the altar is followed by her lying on the funeral bier. This song is, in other words, a memento mori. Despite its rather grim subject matter, the Salzmann family takes it up enthusiastically, with the father’s bass suggesting a choral performance, as recommended by Reichardt in his jovial, D-major setting, with its instruction “Auch im Chor zu singen” (also to be sung in a choir). This morbid text and jaunty tune was music that was meant to be shared.

The song keeps the Salzmann family warm—or at least distracted—until they complete this stage in their journey. Its success at warding off the dreaded “whining” is clearly meant to inspire readers to draw on song at similar moments of danger or disharmony. It is no surprise, then, that Salzmann pauses his account here, as he has already done before, for a didactic aside. “Singing,” he says, “is very common in my house” (55–56). He describes other occasions on which his children sing together, advising all his readers to learn to sing from and with their friends. That way they can avail themselves of all the wonderful songs by the great German poets of the age, “bringing yourselves and others great joy” (57).

Intra- and intra-generational family singing is found throughout the world’s cultures (Brand, 1986; Trehub, Unyk, & Trainor, 1993; Trehub et al., 1997; O’Hagin and Harnish, 2003; Custodero, 2006). Children’s songs and nursery rhymes are often performed with adult family members, whether simultaneously (in unison or harmony) or sequentially (as in call-and-response) (Berger and Cooper, 2003; Edwards, 2011). In one corpus of printed children’s songs, however, such musical partnering between young and old was scripted, arguably for the first time. These songs appeared in the juvenile print culture of late eighteenth-century Germany (Brüggemann and Ewers, 1982; Rehle, 1989; Mittler and Wangerin, 2004). Emerging from the “moral weeklies” popular among adult readers, children’s periodicals and digests offered a variety of poems, theatricals, riddles, songs, stories, and non-fiction content, all promoting norms around filial obedience, virtue, and productivity. The periodicals often presented a fictional family as a model for readers, who were encouraged to share the content aloud with members of their own extended families. But the “disciplining” going on in this literature was as much emotional as it was moral. Melodramatic plots to dialogues, plays, and Singspiele allowed for tenderness and affection to be role-played in the family drawing room. And the poems and songs included in and spun off from these periodicals constituted, for the first time, a shared repertoire meant to be sung and played by young and old together. Duets for brothers and sisters, parents and children—with such prescriptive titles as “Brotherly Harmony” and “Song from a Young Girl to Her Father, On the Presentation of a Little Rosebud”—not only trained children how to be ideal sons, daughters, and siblings. They also habituated mothers and fathers to the new culture of sentimental, devoted parenthood.

In what follows, I explore songs for family members to sing together in German children’s literature before 1800. These songs appeared in children’s periodicals, digests, and play collections (either as freestanding songs or embedded in theatricals), and as separately published song collections and vocal scores. In surveying this repertoire and its early reception, I uncover the reciprocal learning implied in text, music, and the act of performance itself, as adults and children alike rehearsed the devoted bourgeois nuclear family.

Depending on how they are counted, some forty to fifty German-language children’s periodicals were published in the last third of the eighteenth century, beginning in 1771–72 (Wild, 1987). With average print runs of 1,000, and assuming an average of roughly ten readers per copy (Uphaus-Wehmeier, 1984), we can estimate a total readership of up to 500,000, or around 2.5% of the roughly twenty million inhabitants of the German-speaking lands (Köberle, 1972; Heckle, 1987). Modeled on the moralische Wochenschriften (moral weeklies) popular with adult readers, these periodicals offered a range of edifying amusements: poems, theatricals, riddles, songs, stories, illustrations, and non-fiction content (Mueller, 2021). Like novels, fairy tales, and fables, periodicals belong to the genre of recreational literature, one of a number of genres of eighteenth-century German children’s literature that also includes moral instruction, religious tracts, and educational textbooks in reading, writing, arithmetic, and other subjects (Brüggemann and Ewers, 1982). The periodicals were meant to be shared by all members of a family, read aloud and—in the case of songs and theatricals—performed in the home, in one’s “kleinen Familientheater” or little family-theater, as it was sometimes called (Hiller, 1778).

The most influential, if not the first of the children’s periodicals, was Der Kinderfreund, published in Leipzig from 1775 to 1782. Der Kinderfreund was edited by the poet, playwright, librettist, critic, and pedagogue Christian Felix Weisse (Hurrelmann, 1974; Abert and rev. Bauman, 2001; Mai, 2003; Löffler and Stockingern, 2006). Der Kinderfreund went through four editions extending to 1805, had a print run of at least 10,000, and may have been read by as many as 100,000 children in Germany alone, according to one estimate (Hurrelmann, 1974). Der Kinderfreund’s material was presented within a moralizing frame narrative starring a model family, led by a kindly paterfamilias named Herr Mentor. The name was a clear reference to Telemachus’ tutor in Homer’s Odyssey, known to many eighteenth-century readers through Fénelon ( 1699). Mentor and his friends provide the four Mentor children with a panoply of poems, songs, stories, skits, and plays, all inspired by episodes in the children’s everyday life—from a casual stroll in the woods, to a catastrophic fire in a nearby town, to the sudden illness of elder daughter Lottchen. This content helps the family to process their experiences, while also conveying moral lessons. Emily Bruce has argued that the frame narratives not only showed Der Kinderfreund’s readers how to behave; “(T)he lesson also models a way to read, with the fictional frame children discussing the story they have just heard with their father, identifying with the characters, and investing the story with meaning (from) their quotidian life” (Bruce, 2015, 65). This was, in other words, a shared learning process. Erziehung and Bildung (roughly, education and upbringing) preoccupied many German Enlightenment thinkers, particularly as a means of raising productive bourgeois subjects and thereby increasing the power of the state (whether it be Prussia or the Habsburg lands). And as a corollary to the rise in companionate marriage in the late Enlightenment, the sympathetic bonds between members of an elementary family were increasingly felt to be crucial to those larger projects (Hurrelmann, 1974; Dettmar, 2002). Familial affection of course predated its enshrining in print; what was new, rather, was the notion that this affection must be both choreographed and put on display.

Cooperation and affection between adults and children were key tenets of the German educational reform movement known as Philanthropinism, which we already encountered through Salzmann. Established by Johann Bernhard Basedow in the 1770s, Philanthropinism emphasized play-based learning and cultivating joy and pleasure in parent-child and teacher-student relationships. In addition to treatises and institutions that propagated Philanthropinism, periodicals like Der Kinderfreund were an important means of popularizing its principles (1776:3, 132–138). On a broader level, from its title to every detail of its form and content, Der Kinderfreund emphasized friendship between adults and children. In the very first issue, Mentor professed to love his children “more than all the treasures of the earth, more than the whole world, yes, I almost want to say, more than my life” (Mueller, 2013, 143). It is this insular, all-consuming devotion that I wish to trace in domestic songs for children to perform with their family members.

Music-making served as both a model and catalyst for the emotional habituation of parents and children to the new ideal of the sentimental, devoted family. Even before Weisse started publishing Der Kinderfreund, there already existed a repertoire of Kinderlieder (children’s songs) published in collections and other periodicals and aimed at a young readership (Smeed, 1988; Schilling-Sandvoß, 1996; Freitag, 2001; Buch, 2014). Most Kinderlieder collections appeared in the same cities that produced the majority of children’s literature as a whole: Leipzig and Berlin, the centers of north German publishing and music printing. With multiple editions, high-profile subscribers, and frequent reviews in periodicals like the Allgemeine deutsche Bibliothek, Mannigfaltigkeiten, and the Hamburg Unterhaltungen, Kinderlieder collections and Kinderlieder in children’s periodicals enjoyed wide circulation and critical reception, similar to their counterparts in devotional and domestic Lieder for adult consumers (Head, 1999; 2013; Gramit, 2002; Parsons, 2004; Joubert, 2006).

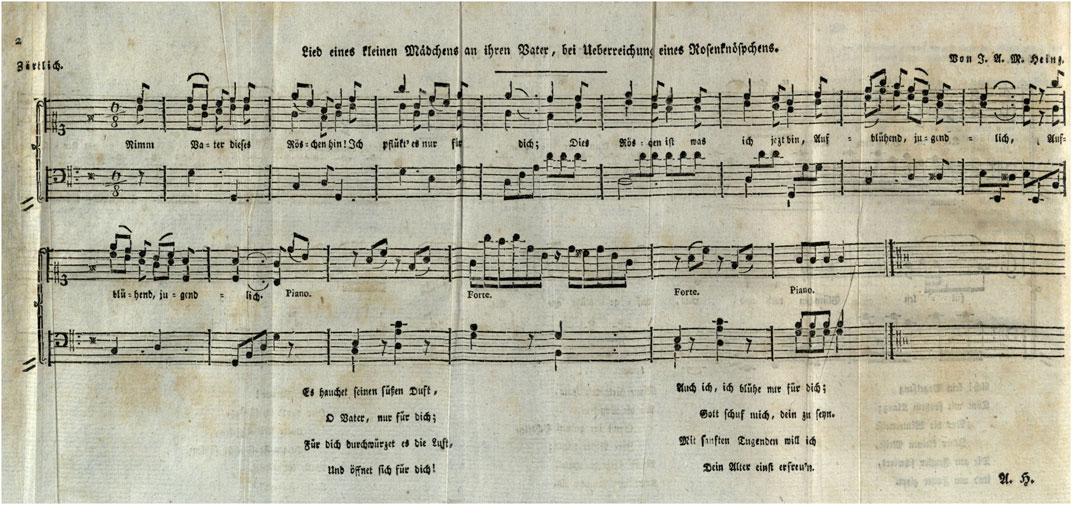

The subject matter of these songs ran the gamut, as with children’s periodicals—from the change of seasons, to building a snowman, to a sibling’s case of smallpox, to the sudden death of a playmate. Those intended for children or parents to sing to or with each other (Table 1) were often explicit in their moralizing. Songs sung by a child to a parent were both performative and demonstrative: they inculcated filial values in children, and gave them a means of affirming those values to their parents while also learning the basics of singing technique and the conventions of domestic music. An example is “Lied eines kleinen Mädchens an ihren Vater, bei Ueberreichung eines Rosenknöspchens” (Song from a Little Girl to Her Father, On the Presentation of a Little Rosebud), which appeared in Amaliens Erholungsstunden (Amalia’s Recreational Hours), a periodical dedicated “to Germany’s daughters” and edited by the Stuttgart-based author, publisher, and philosopher Marianne Ehrmann (1791:2.1, after 286). In the poem (by “A. H.”), a girl presents a rosebud to her father, declaring:

I plucked it just for you;

This rosebud is what I am today,

Blooming, youthful.

It breathes its sweet fragrance,

O father, only for you;

[…] And opens up for you!

[…] I too bloom only for you,

God made me to be yours

With gentle virtues I will

Bring joy to your old age.

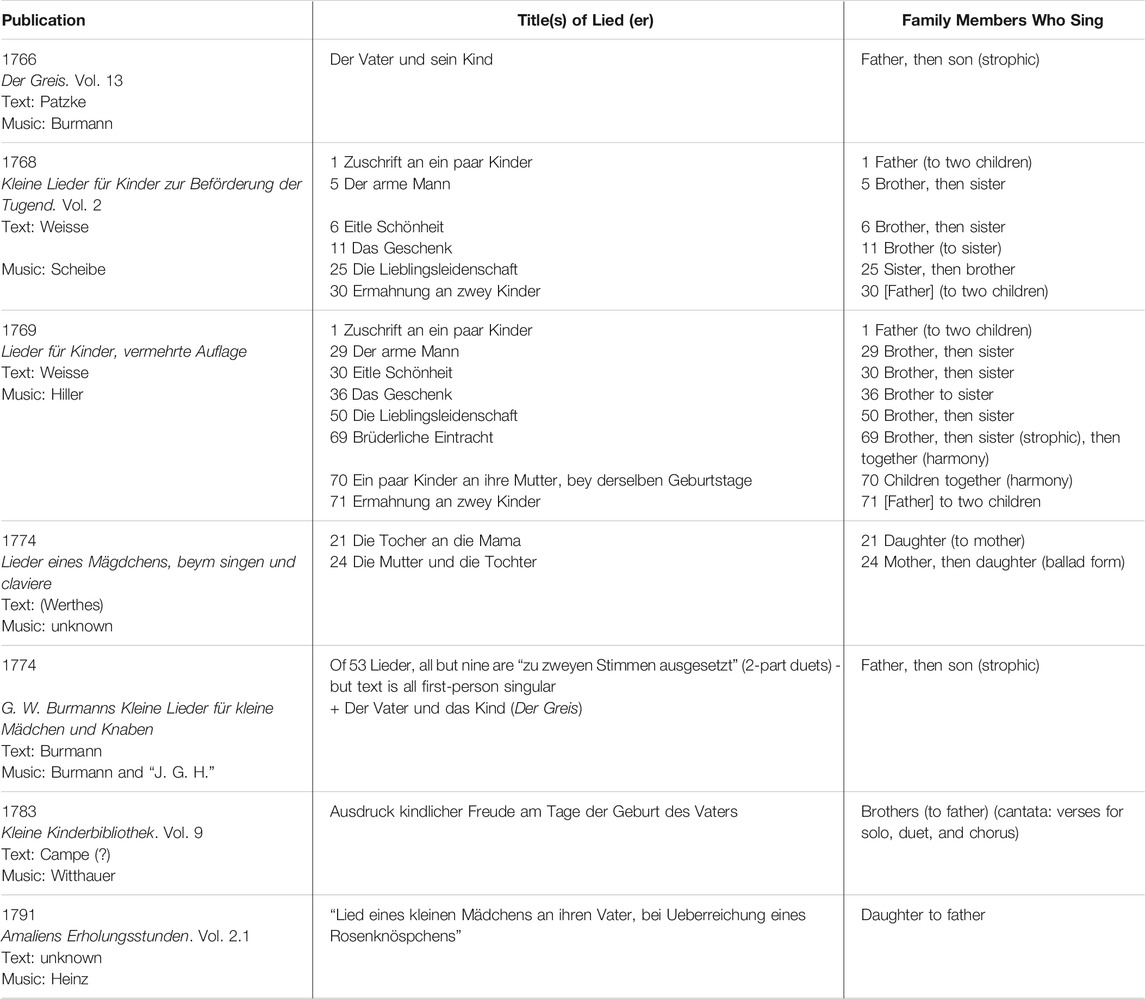

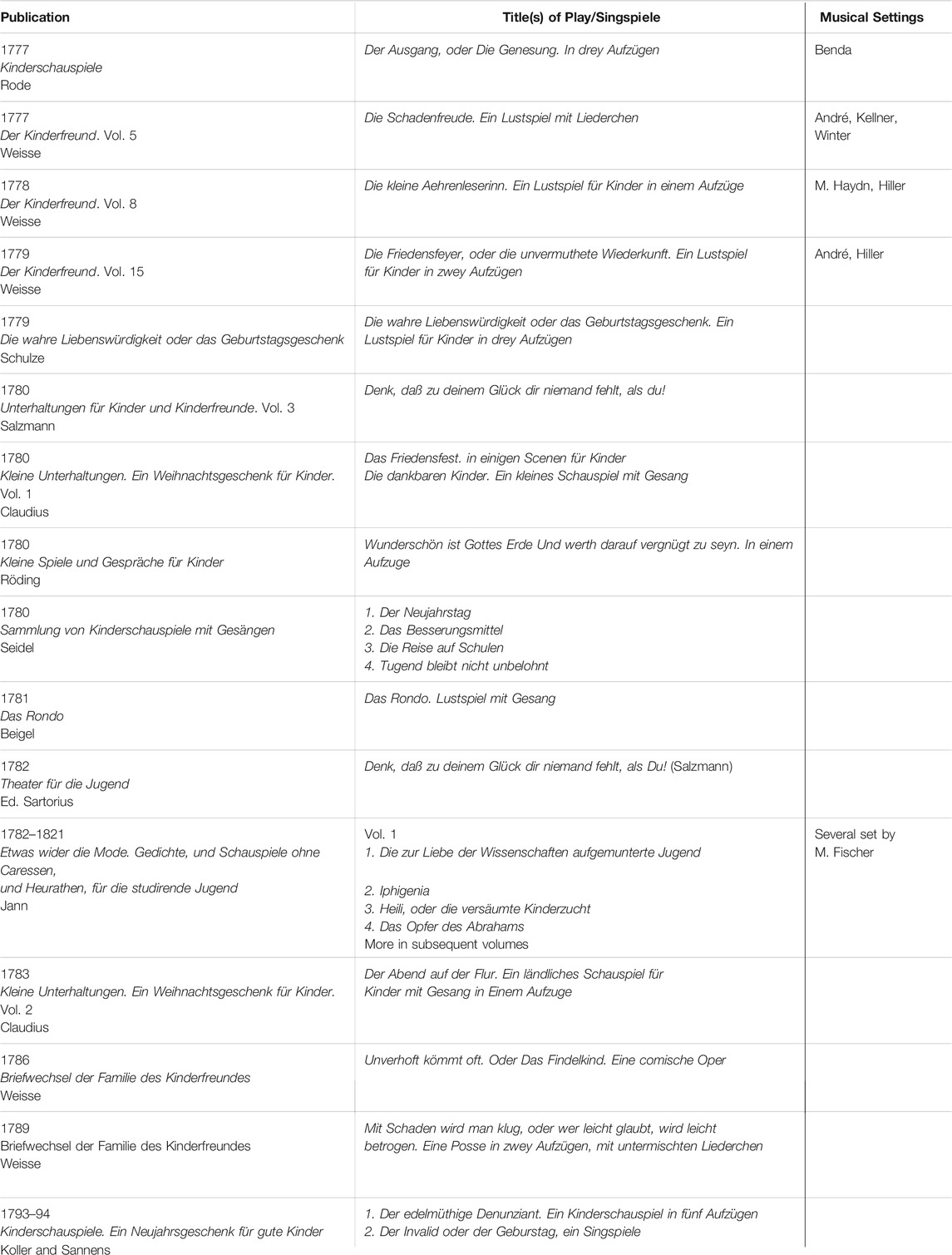

TABLE 1. Lieder for Multiple Family Members in Selected Juvenile Periodicals and Kinderlieder Collections, 1760–1800.

The strophic setting, by the music teacher and composer Johann Adolarius Martin Heinz (based in Ehrmann’s home town of St. Gallen, Switzerland), is a mere 14 bars long, ten for the voice followed by a 4-bar codetta for the keyboard (Figure 3) (Düll and Wallnig, 1996). As was typical for Kinderlieder, Heinz uses a predictably diatonic melody in the major mode, harmonized almost exclusively in thirds, unfolding in a pastoral 6/8 m. A brief excursus into the relative minor extends the consequent phrase, allowing for a repeat of the fourth line of each stanza and a satisfying return to the tonic.

FIGURE 3. Heinz, “Lied eines kleinen Mädchens an ihren Vater, bei Ueberreichung eines Rosenknöspchens” (text: “A. H.”), from Amaliens Erholungsstunden (1791:2.1, after 286). With the kind permission of the University and City Library of Cologne. Shelfmark 2C9064-1791,1/2.

Songs like these certainly staged a certain surveillance of filial virtue. But the genre also called for active participation by parents, as made explicit in songs written for them to sing to their children—what we might call “Elternlieder,” as a counterpart to Kinderlieder. Elternlieder reinforced the intergenerational dialogue modeled in the surrounding periodical (Smeed, 1988; Buch, 2014). Weisse’s book of poems Lieder für Kinder (1767)—which was set by at least three different composers within several years—is bookended by two such Elternlieder, thus encouraging parental participation any time the collection was opened. The collection begins with “Zuschrift an ein paar Kinder” (Letter to a Pair of Children) (Weisse, 1767), which puts a new spin on the classical “hymn to the Muse”: here, the father’s inspiration is his children, along with his own “väterliche Liebe” (fatherly love). The father returns to close the collection with the equally sentimental “Ermahnung an zwey Kinder” (Exhortation to Two Children) (Weisse, 1767), a doting, nostalgic evocation of filial play.

These two examples are typical of the Kinderlieder repertoire in that the unmarked parent is always the father. Mothers almost never “speak” in the texts of these songs. The only time they appear to be referenced, in fact, is as dedicatees—as in Weisse’s “Auf das Bildniß einer geliebten Mutter” (On the Portrait of a Beloved Mother), or his duet, Ein paar Kinder an ihre Mutter, bey derselben Geburtstage (A Pair of Children to Their Mother, on Her Birthday), both of which were new for the revised, expanded second edition of Lieder für Kinder, this time with musical settings by Hiller (1769). Hiller, a composer and pedagogue, was already Weisse’s frequent collaborator on Singspiele (plays with music) for the commercial stage (Bauman, 1985; Krämer, 1988; Abert and Bauman, 2001; Joubert, 2006), and was responsible for the vast majority of song settings in Der Kinderfreund as well as composing songs for at least three of Weisse’s children’s theatricals.

The textual silence of mothers is part and parcel of the paternalism of the (overwhelmingly male) authors of children’s periodicals. Wild (1987) describes the mother’s role in this literature as “Stellvertreterin des Vaters” (father’s deputy), executing and enforcing paternal decisions and orders—an example of which we have already seen with the opening excerpt from Salzmann’s Unterhaltungen, where the mother began to sing the Lied as a way to comfort the freezing children and appease the easily angered father. Indeed, the two children in Weisse’s “Ein paar Kinder” praise their mother with improbable omniscience: their line “Your concerned, alert gaze/Always hangs over our cradles” implies that they somehow see her watching them throughout the night.

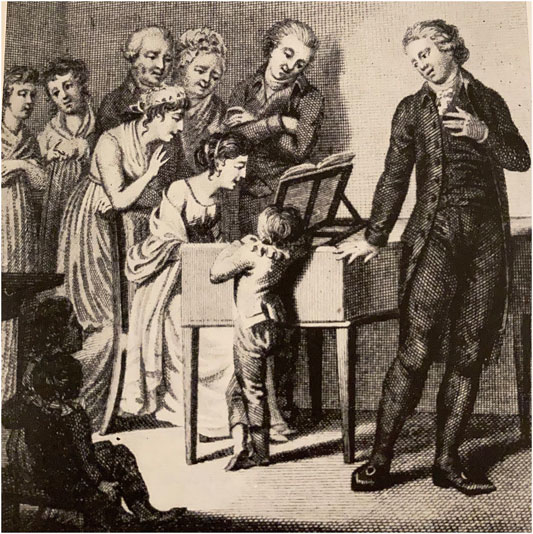

One might also understand mothers as figures of emulation as well as usurpation or subjugation. In keeping with the Geschlechtscharakter ideology of the time, women were assumed to be naturally adept at intimacy, the paragons of feeling (Gleixner and Gray, 2006). Fathers may have been ventriloquized more often in part because they were perceived to require the assistance of explicit songs in order to emote. As I argue elsewhere (Mueller, 2021), the iconography of Kinderlieder frequently depicts a mother or older sister as the accompanist, implying that she “speaks” obliquely, through her accompaniment and in the many codettas and other flourishes found in these Lieder themselves, such as the coda to the “rosebud” song from Amaliens Erholungsstunden (Figure 4). Mothers were sometimes even explicitly nominated for this role, as in Johann Adolph Scheibe’s preface to the first volume of his settings of Weisse’s children’s poems, Kleine Lieder für Kinder zur Beförderung der Tugend (Little Songs for Children for the Promotion of Virtue, 1766:1, n.p.). Scheibe dedicated the collection to “Frau W. * * in Leipzig,” or Weisse’s wife, imagining her accompanying herself at the keyboard. He fantasized about

FIGURE 4. Meno Haas, after Heinrich Anton Dähling, Familienkonzert (1800). Meno Haas, after Heinrich Anton Dähling, Die Klaviervirtuosin (Berlin, 1800). Courtesy of Kunstsammlungen der Veste Coburg, Inv.-Nr. V,112,111.

How much [Weisse’s] fatherly heart will be moved, when you sing [these Lieder] to your sweet children—one on this side, the other on that side, the third at a certain distance by the fat side—from the Klavier with motherly love. And they, these loveable children, will babble along one after the other; the virtue that is already their birthright will develop in their hearts all the more easily; they will feel it, comprehend it, and carry it out.

Feeling, in other words, would lead to understanding and practice, and the first step in this process was the mother.

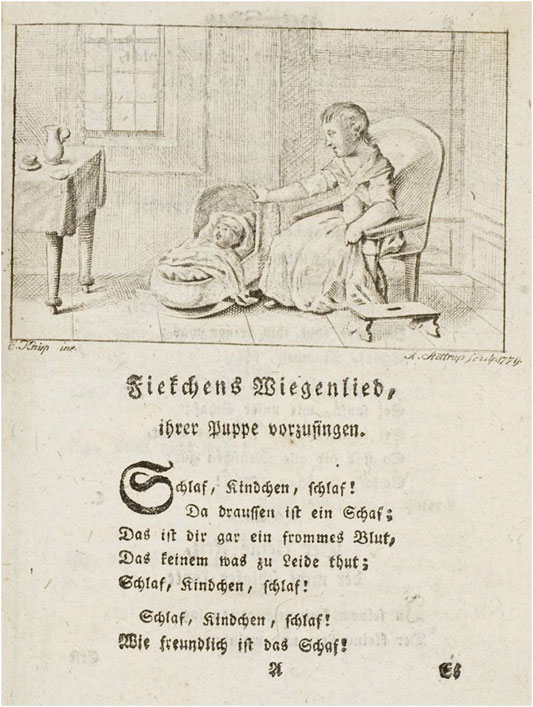

Another notable exception to the silence of mothers was the subgenre of lullaby collections. Women were expected to sing in the nursery, in keeping with Rousseau’s assertion in Emile, ou de l’education that the mother was the ultimate source of the entire moral order [Rousseau (1762, 171)]). And as Gramit (2002) has pointed out, girls were often encouraged to submit to singing instruction as a way to improve their roles as wives and mothers. Such was the motivation for Reichardt’s collection Wiegenlieder für gute deutsche Mütter (Lullabies for Good German Mothers, 1798), whose preface opposed “good, sweet mothers” to “incomprehending, hot-blooded wet-nurses” looking for short cuts to soothe their charges (iii-iv). In other words, lullaby collections were part of the same appropriation of female knowledge and oral tradition as the nascent field of pediatrics was for midwifery. These ideologies converge in Reichardt’s Wiegenlied “Für Sophie ihrer Puppe vorzusingen” (For Sophie to Sing to Her Doll) (Reichardt, 1798). The poem, by the author and Philanthropinist Joachim Heinrich Campe, originally appeared in his Kleine Kinderbibliothek (1779:2, 1–2), a children’s reader that rivaled Weisse’s Der Kinderfreund in its popularity and influence. In its original appearance, the poem (here entitled “Fiekchens Wiegenlied”) has pride of place at the beginning of the 180-page volume, illustrated with the only engraving to appear within a page rather than as a tipped-in plate (Figure 5). The inclusion of this Lied in Reichardt’s lullaby collection some 20 years later presupposes that girls might occasionally—indeed, should—join their mothers at the cradle. After all, as Reichardt notes in his preface, the “attentive child” who sings such a song to her doll can “awaken many good feelings, make many a good teaching more penetrating” (v). Thus could young girls rehearse their future roles as mothers.

FIGURE 5. Campe, “Fiekchens Wiegenlied, ihrer Puppe vorzusingen,” from Kleine Kinderbibliothek (1779:2, 1). Courtesy of SUB Göttingen, shelfmark DD ZA 246:2.

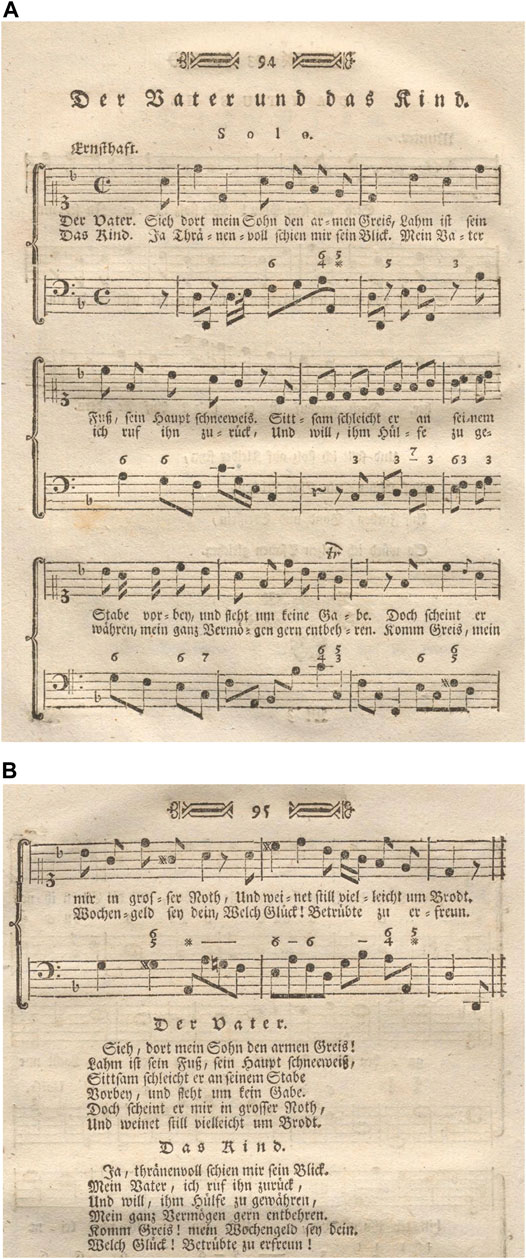

Kinderlieder occasionally called upon parents to sing not just to, but also with, their children, alternating strophes in the manner of a dialogue poem. In one of the first sets of Kinderlieder to appear in any print medium, the nine songs included in a 1766 issue of Johann Samuel Patzke’s moral weekly Der Greis (The Old Man), one of the Lieder is a duet called “The Father and His Child” (1766:13, 118–119). In this Lied, a father and son are out walking and come across a poor man begging. The father points the man out to his son, and the son, feeling compassion for the man’s misery, offers him his own allowance. The setting, by Gotthold Wilhelm Burmann, was later anthologized in Burmann’s separate collection of Kleine Lieder für kleine Mädchen und Knaben (1774, 94–95) (Figures 6A,B). Father and son alternate verses to the same somber march in D minor, with an expression marking “earnest” and an awkward, lopsided approach to declamation and phrase length (part of which may stem from a metric error in the engraving of mm. 3 and 8).

FIGURE 6. Burmann, “Der Vater und das Kind” (text: Patzke), from G. W. Burmanns Kleine Lieder für kleine Mädchen und Knaben (1774, 94–95). Courtesy of Zentralbibliothek Zürich, shelfmark 6.43,3.

Weisse’s Lieder für Kinder included many dialogue poems, whether for a pair of birds, a parent and child, or two siblings. Three examples of the latter were set by Scheibe in volume two of his Kleine Lieder für Kinder (1768): “Der arme Mann” (The Poor Man), “Eitle Schönheit” (Vain Beauty), and “Die Lieblingsleidenschaft” (The Favorite Passion). In all three cases, Scheibe switches to the relative major or minor for the second strophe, an economical technique for effecting a change in mood without over-challenging young singers.

In addition to strophic duets, composers also set duets for family members to sing simultaneously, in harmony with each other. Weisse and Hiller’s duet for the two children on their mother’s birthday is one example of this subgenre, set almost exclusively in homophonic thirds and sixths. Burmann’s Kleine Lieder für kleine Mädchen und Knaben (1774) unfolds as a set of fifty-three duets, printed in parts on facing pages. However, the Lieder texts are all first-person singular, so the harmony is purely musical.

A more complex example, and one that explicitly stages siblinghood, is “Brüderliche Eintracht” (Brotherly Harmony), also from Weisse and Hiller’s revised Lieder für Kinder (Weisse, 1769). “Brüderliche Eintracht” unfolds over four verses that are traded between a brother and sister, followed by a closing verse for both siblings. The refrain is a self-reflexive apostrophe: “These must well be siblings,/ Because their love is tremendous!” Hiller’s setting is a slow minuet in rounded binary form with a straightforward conjunct melody (Figure 7A). In the final stanza, however—at the text “Oh, let us always burn with this friendship”—not only do the brother and sister sing together, they are singing in “brotherly” harmony (Figures 7B,C). Hiller singles out this Lied in his preface to the volume, showing how unusual this piece would have appeared to readers: “the last verse is sung by two voices, and I have given each voice its own line” (Weisse, 1769). The right hand of the keyboard splits into two staves, with the sister presumably taking the top line and the brother harmonizing a third below. For the refrain—“Where hearts stand in alliance,/There is the first blood-relationship beautiful!”—Hiller adds a new feature: a point of imitation, initiated by the lower voice and taken up by the higher. This call-and-response allows the “sister” to sing higher than in the previous verses, enhancing the poignancy of the duet.

In addition to freestanding Lieder, readers might encounter arias, duets, ensembles, and choruses for family members (either solely as texts or with musical settings) in the many theatricals for domestic performance that were published in children’s periodicals and in separate collections (Table 2). Theatricals for juvenile readers were often based on everyday life, with children portraying thinly fictionalized versions of themselves, and their parents or older siblings portraying their fathers and mothers. The roles were often stereotyped: “rational fathers, mischievous sons, virtuous daughters, caring mothers,” as Ute Dettmar (2002, 11) summarizes it. This was a participatory, interactive repertoire, one in which, as Dettmar argues, the close-knit family “instantiates itself in its rituals and at the same time celebrates itself in its staging. [Fictional] setting and performance venue blend together, and the family-theater does not seek to build a “fourth wall”; the amateur actors perform as family members and as such are addressed as spectators” (20).

TABLE 2. Selected Children’s Theatricals with Vocal Ensembles for Multiple Family Members, 1760–1800. Italics are the titles of individual plays/Singspiele.

Putting children on display in private theatricals was another way to monitor and coopt their free time for the projects of Erziehung and Bildung. By memorizing moralistic dialogue, submitting to the direction of an adult “director,” and impersonating idealized children, all for the approval of an adult audience, children could affirm the principles of virtue and filial obedience (Wild, 1987). A number of the plays exposed child misbehavior to critique, even mockery, as in “Die Schadenfreude” from Der Kinderfreund (1776:5), or “Denk, daß zu deinem Glück dir niemand fehlt, als du!” (Keep in Mind That You Do Not Need Anyone But Yourself To Be Happy!), from Salzmann’s Unterhaltungen für Kinder und Kinderfreunde (1780:3) (Mueller, 2021). Since this top-down, edifying function of plays, scenes, and dialogues was foregrounded within the works themselves, as well as prized highly by both authors and critics, this tends to be the aspect most frequently emphasized by modern-day scholars (Cardi, 1983; Mairbäurl, 1983; Dettmar, 2002).

As with the Kinderlieder, however, there was more at work in domestic children’s theater than just Foucauldian disciplining of children, or the exporting of religious instruction to an increasingly secular domestic space. Parents needed “disciplining,” too, an opportunity to rehearse the kind of familial intimacy called for by pedagogical reformers. This is confirmed in paratexts such as Carl August Gottlieb Seidel’s preface to his 1780 Sammlung von Kinderschauspielen mit Gesängen (Collection of Plays with Songs), in which he wrote that he not only gave these theatricals to his children, but performed them with them. Meanwhile, the melodramatic plots borrowed from the sentimental theater offered plenty of opportunity for pathos: abandonment and reunion, war, disaster, poverty, and death featured prominently. The heightened emotions and often traumatic nature of such events, as Wild (1987) notes, offered a pretext for tenderness and vulnerability to be foregrounded. As a Neue allgemeine deutsche Bibliothek review of one Kinderschauspiele collection noted, “We already know that Kinderschauspiele are mostly of the sentimental genre [rührenden Gattung], in which innocent children or thoughtful parents are usually the main roles, in contrast to hard-hearted people or spoiled children” (1795:15, 60). In other words, the goal was not just to give children models for how to be innocent instead of spoiled, but also to give parents models for how to be thoughtful instead of hard-hearted. In their “double address” to both children and their parents, then, the dialogues, plays, and Singspiele in collections like Der Kinderfreund encompassed more than moral guidance. They also offered a template for frank emotional expressivity, a training ground for knitting the family together along more intimate lines than ever before.

This knitting-together was often modeled within the works themselves, in those rituals (inevitably set to music) with which family members marked birthdays, anniversaries, reconciliations, and especially reunions—again, moments that lay outside the everyday, thus eliciting heightened emotional response. Such moments of self-conscious celebration served to make explicit these works concern with promoting family solidarity (Dettmar, 2002). Music and stage directions often egged readers on to tears and effusive embraces, facilitating a kind of emotional role-play as parents and children habituated themselves to the ideal of familial devotion. When plays brought family members together, their embedded songs capitalized on music’s power to facilitate communal feeling (Joubert, 2006). This was especially true of vocal ensembles for family members, which were already marked as they occurred much more rarely than solo arias.

One poignant vocal ensemble occurs in August Rode’s Der Ausgang, oder die Genesung (The Way Home, or The Convalescence/Recovery) (Ewers, 2010). Rode was a colleague of Basedow’s at the Philanthropinum, who published Der Ausgang in 1777 as one of a set of three Kinderschauspiele dedicated to the Philanthropinum. Der Ausgang portrays the return of a father to his family after overcoming a life-threatening illness in the care of his doctor (Mueller, 2011). In his preface, Rode instructed adults taking on the roles of “The Mother” or “The Father” that they must “not be present at these performances merely as a favor to the children; rather their attention (must) not waver, and they (should) feel their hearts moved by a good-natured sentiment” (n.p.). Such remarks echoed the imperatives for attentive parental involvement in childrearing treatises from Rousseau (1762) to Basedow (1770) (Hurrelmann, 1974), as well as the “rhetoric of attention” which Matthew Riley (2004) has identified across contemporaneous German aesthetics. Whether observing from the audience or acting alongside their children, parents were expected to be emotionally invested participants in the ritual.

Rode’s Der Ausgang has just one musical moment, for which no musical settings appear to survive. But it is an extended scene, the crux of the play. In a performance-within-the-play, the father’s five children sing and dance a “Ronde” (Round) in honor of his return. Rode calls for the music to change with each verse, as the children reflect on the range of possible catastrophic outcomes of his illness, and their good fortune that he is out of danger. The stage directions set out in exacting detail both the emotional turns in the music, and the father’s subsequent outburst of affection and gratitude.

(The children stand so that when the father enters, he comes right into their circle; they close it at once; a light, cheerful music arises; and they dance with simplicity, decency, and cheerfulness around their father, and sing, as follows:)

Be welcome, welcome

With joy, Father, here!

(The music is here slower, and the children only sing, do not dance.)

If Death had taken you,

Beloved, we would have mourned.

[ . . . ]

(The music changes here again, and expresses joy, and the children dance again.)

But now, now joy shouts

Out of your children’s breast.

[ . . . ]

Be welcome, welcome

With joy, Father, here!

(The Father, surprised by these entrances, stands entirely without moving, among his children. Soon the tears come into his eyes, his head sinks down a little sideways, and with the deepest sentiment in his eyes he looks down at the dancing. When they have sung and danced, he embraces them all with silent emotion; the children are full of joy and caress him.)

The precise choreography, even down to gaze and head position, implies that such demonstrative signs of familial affection could not be taken for granted among Rode’s readers. In other words, children’s theatricals like these offered not just a pretext, but also a textual and even physical vocabulary—a blueprint—for parental participation in the theatrical modeling of the devoted family.

Just as Christian Felix Weisse dominated the genre of the children’s periodical, so too with the children’s theatrical—no surprise, given his long history as a playwright, librettist, and translator. Over the course of its seven-year run, Der Kinderfreund included twenty-four one- and two-act plays, and its sequel, Briefwechsel der Familie des Kinderfreundes (Correspondence of the Kinderfreund Family, 1784–92), which ran for another eight years, had thirteen. Most of these plays were also published separately, as well being anthologized in the 1778 Sechs Schauspiele für Kinder and the three-volume 1792 Schauspiele für Kinder. Of Der Kinderfreund’s twenty-four plays, three include solo songs, while five include songs and vocal ensembles. Briefwechsel’s thirteen included one with a solo song, another with “untermischten Liederchen” (intermingled little songs), and a third billed as a “comische Oper.”

As already mentioned, Hiller set many of the songs in Weisse’s plays, and published vocal scores to at least two: Die kleine Aehrenleserinn (The Little Gleaner-Girl, 1778) and Die Friedensfeyer, oder die unvermuthete Wiederkunft (The Peace Festival, or The Unexpected Return, 1779). In Die kleine Aehrenleserinn, the titular heroine and her poor, widowed mother are adopted into the family of a benevolent landowner. The final vaudeville has each character reflect on their experiences, concluding with a pun on the play’s title. Thus the harvest becomes an allegory for the cultivation of family along sentimental and companionate lines (Mueller, 2011, 46). In Die Friedensfeyer, a local nobleman’s children participate in a peace festival following the end of the War of the Bavarian Succession. The nobleman is feared dead, but he secretly takes the place of the monument that is being dedicated to his memory, and just as the children finish singing a verse at the festival about Peace returning to families their missing “husbands, sons, fathers, and brothers,” the curtain rises to reveal the living father, the stone made flesh (a moment memorialized in the engraving that accompanies the play). The effect of this transcendent reunion is, as Carola Cardi (1982, 186) argues, to lift war and peace “out of social reality” and into the realm of other “natural and God-given phenomena” (Mueller, 2011, 53-61).

In addition to songs in children’s theatricals that were billed as “Schauspiel” (play) or “Lustspiel” (comedy), some theatricals were labelled as musical theater, whether “Operette für Kinder” or “komische Oper.” An example of this appears in volume five of Weisse’s sequel to Der Kinderfreund, Briefwechsel der Familie des Kinderfreundes. The Singspiele is called Unverhoft kömmt oft, oder Das Findelkind (Things Always Happen When You Least Expect Them, or The Foundling) (1786:5; Bauman, 1985), and it was soon set to music by the famed composer Georg Benda, who published a free-standing piano-vocal score. In keeping with Der Kinderfreund’s frame narratives, this “komische Oper” is presented as an offering by the family friend Herr Spirit, inspired by Karl’s account of a walking excursion with his friends, during which a storm broke out and a kindly woodcutter offered them shelter. The story introduces an officer’s wife, Frau von Lilienfeld, despondent and guilt-ridden at her six-year-old son having gone missing while her husband is away at war. She encounters a poor woodcutter’s son who is the same age as her lost child, and, in her grief, immediately offers the boy’s father money if he will let her adopt his son. Despite her and her maid’s bribes, the rationalizations of the woodcutter’s greedy wife, and the temptations of wealth for the child’s elder siblings, the father holds strong and rejects Frau von Lilienfeld’s offer. Chastened by his devotion, she withdraws the request, which immediately triggers the miraculous reappearance of her own boy. Mother and son are reunited in a dénouement memorialized in the play’s lone illustration, with Frau von Lilienfeld depicted in a transcendent pose reminiscent of the Fainting of the Virgin (Figure 8).

FIGURE 8. Tipped-in illustration, “Unverhoft kommt oft, oder das Findelkind,” from Weisse, Briefwechsel der Familie des Kinderfreundes (1786:5, after 162). Courtesy of Bayerische Staatsbibliothek München, shelfmark Paed.pr. 4415 i-5, urn:nbn:de:bvb:12-bsb10761748-7.

Frau von Lilienfeld gives the woodcutter’s family a sizable reward for teaching her a valuable lesson about parental devotion, and her maidservant even draws an analogy to parental love in the animal kingdom in the aria “Die Affen lieben ihre Kinder” (Apes love their children) (176):

Apes love their children

(So they say) no less,

The baby ape is their plaything and game,

They love it so much, and press, and press

Their baby ape so close to their heart

That they nearly choke the baby.

The image of the mother embracing her child to the point of smothering him is the polar opposite of her earlier carelessness, for which she had blamed the son’s disappearance. Thus did Weisse’s comic opera serve as a cautionary tale for indifferent parents, as well as offering a model—outside even the human—for the kind of intimacy sacralized in the drama. As Frau von Lilienfeld puts it in the aria she sings after being reunited with her son (174):

Bey Vaterpfleg und Mutter Sorgen, Only through father’s care and mother’s concern

Ist nur der Kinder Glück geborgen. Is children’s happiness ensured (safe).

Nearly all of these children’s periodicals and collections (whether of Lieder or plays) included prefaces in which the author, composer, or editor addressed their readers and set out their goals for the publication. I have already referred to several such prefaces, and there are numerous other examples. Many were addressed directly to “meine kleinen Leser” (my young readers), or “An die Jugend” (to the youth), advancing the conceit that children’s literature was exclusively read by the young. But as all young readers surely knew, the main consumers—indeed, patrons—of children’s literature were parents and educators. Lathey (2006, 2) describes prefaces in children’s literature as seeking “to justify the choice of text, to commend its didactic intent, or to reconcile teachers, parents, and child readers to its provenance and content.” Bruce (2015, 83) puts it somewhat more strongly: prefaces sought “to exert control over the relationship between author and reader,” in much the same way as the aforementioned frame narratives featuring model families sought to circumscribe the reading experience, and by extension, shared free time as a whole.

In prefaces to Kinderlieder collections, composers often enumerated the benefits of singing the songs, while also occasionally offering guidelines for their performance or apologias for their unassuming appearance. Hiller’s preface to his first set of Lieder für Kinder (Weisse, 1769) sets this out plainly: “I have,” he writes, “given preference to light and natural singability over the bombastic and artificial. Good coherence of the voice, pure intonation, and a clear and affecting delivery is more important than (executing) all the mordents, trills, and turns.” Claudius (1780) exhibited a trait common to many of these prefaces: paying tribute to those who had already published in the genre, especially Weisse and Hiller. Claudius acknowledged the primacy of Hiller’s collection, and professed only to have published his set for very young players, “those of you who would always come away from the Clavier with a sad face, and lament that (Hiller’s Lieder für Kinder) was still too difficult for your little fingers.” Claudius went on to insist, with conventional humility, that his melodies were “not nearly as beautiful as those of the excellent Hiller—but I have done what was within my ability, and you will have to be content with that.”

Such modest prefaces may have been a way to forestall criticism—after all, these publications were reviewed in general-interest periodicals like the Allgemeine deutsche Bibliothek (General German Library) as well as specialty education periodicals like the Allgemeine Bibliothek für das Schul- und Erziehungswesen in Deutschland (General Library for the Schooling and Education System in Germany), and in the newly emerging music journals that were establishing a robust critical tradition around music for domestic consumption (Rose, 2019). In fact, like Weisse himself, many of the composers who produced music for the juvenile market were also themselves music critics. Scheibe was the editor of one of the earliest music journals, Der Critische Musicus (1737–38, 1740). Hiller edited one of the earliest music periodicals, the Wöchentliche Nachrichten und Anmerkungen die Musik betreffend (Weekly News and Notes Regarding Music, 1766–70), which, as Rose (2019) points out, was aimed at amateurs. Reichardt also advanced the cause of simple, unaffected music in his own Musikalisches Kunstmagazin (1782, 1791). With so many of these agents of German canon formation “moonlighting” as composers of music for the young, it is little surprise that the narrative of “edle Einfalt” (noble simplicity) should be such a key tenet of German nationalism in music.

Despite composers’ best efforts, however, music critics pulled no punches when it came to Kinderlieder collections. Possibly the earliest such collection, Scheibe’s Kleine Lieder für Kinder, volume 1 (1766), received a scathing review in the Hamburg Unterhaltungen (1768:5, 343–344) that was particularly unforgiving of Scheibe’s use of parallel fifths and octaves. Scheibe—already infamous for his critique of J. S. Bach in 1737— was incensed enough by this review to publish a sprawling rebuttal that took up seven and a half pages of the eight-page preface to volume two of his Kleine Lieder für Kinder (1768, 1–8). Scheibe even referred to the reviewer as “mein Gegner” (my enemy/adversary). Hiller published a gentler review of Scheibe’s volume two in his Wöchentliche Nachrichten (1766:1, 356–360), sympathetically noting the “heftigen Kritiker” (severe criticism) Scheibe had received, while also confessing, “the more fierce (Scheibe) is, the less we wish to get embroiled in the debate” (356). A few years later, perhaps apprehensive of similar treatment, Burmann wrote in the preface to the first of his collections, Burmann (1773), that “The musical critic will of course find reason enough for criticism—and perhaps no one criticizes more, than myself.”

As for the subject of the present article—songs for family members to sing to or with each other—most critics do not seem to have addressed these songs individually in their reviews of Lieder collections. One exception was Hiller’s (1776:1, 358) review of Scheibe’s volume 2. He praised his fellow composer Weisse for his “expressive melodies,” particularly in those duets where Scheibe supplied different music for different strophes (as discussed above). In general, songs in plays and theatrical anthologies tended to be largely overlooked by critics, in favor of criticisms of plot and language. The only one of Weisse’s three separately-printed children’s Singspiele to have received a review appears to be Hiller’s setting of Die kleine Aehrenleserinn, in the Allgemeine deutsche Bibliothek. The short, muted review suggests that parents who had first read the Singspiele were “doubtless eager to see it performed by their children” (1780:40, 127). The reviewer goes on to observe, however, that Hiller’s music is not accessible to the average child, and was clearly composed with the professional stage in mind. Indeed, a number of these plays made their way into the repertoires of professional children’s troupes (Dieke, 1934; Mueller, 2013).

Another strain of criticism may have been motivated by regional or confessional rivalries. The Jesuit priest Franz Xaver Jann, professor at a Gymnasium in Augsburg, published a seven-volume series entitled Etwas wider die Mode: Gedichte und Schauspiele ohne Caressen, und Heurathen, für die studierende Jugend (Something Against the Fashion: Poems and Plays Without Caresses and Marriages, for Studious Youth, 1782–1821). Nearly every volume included a handful of Singspiele alongside spoken plays, all on vehemently chaste subjects. The first few volumes came in for harsh criticism from the Allgemeine deutsche Bibliothek, with one reviewer singling out the Singspiele as “so indescribably wretched and pedantically dumb that there is nothing more to say” (1789:84, 554). Another reviewer even suggested that a better title for the collection might be “Etwas wider den gesunden Menschenverstand” (Something Against Common Sense) (1790:95, 297). Either or both anonymous reviews may have been by Friedrich Nicolai, the editor of the Allgemeine deutsche Bibliothek, who in his Beschreibung einer Reise durch Deutschland und die Schweiz, im Jahre 1781 twice excoriated Jann’s “tasteless” collection (1787:8, 126, 154–155). Concluding that the concept of a “Jesuit comedy” was virtually an oxymoron, Nicolai “pitied” the “poor children who have to ruin their minds with such nonsense.” The occasional critique notwithstanding, the many reprints and anthologies of children’s Lieder and plays shows just how much traction they had in the marketplace.

Free-standing and theatrically embedded songs for parents and children to sing to and with one another constituted—for the first time that we know of in European print culture—a shared, notated repertoire for young and old. The learning taking place here was reciprocal: parents listened to their children perform, siblings listened to one another as they traded verses in a song, and older siblings played parents alongside and in front of their own parents and younger siblings. At the level of the everyday, such reciprocity has been observed in our own time, in more casual musical interactions between parents and infants. Custodero and Johnson-Green (2008, 16) liken such “musical parenting” to “the musical phenomenon of counterpoint,” and describe it as contributing to various aspects of child development. In the eighteenth century, the explicit and implicit goals of German repertoire for family singing bore the weight of many ideological burdens: psychological, moral, social, even nationalistic. As Georg Carl Claudius summed it up in the preface to volume two of his Kleine Unterhaltungen (1783, n.p.): “Honor your God, love your parents, treasure your teachers, respect religion and virtue, and you will—and you must—be happy.” In other words, through obedience, morality, and a sense of shared obligation, children could find fulfillment. A poet and composer of Kinderlieder himself, Claudius knew well the role that singing could play in supporting all of those pursuits. But as the intimate family portrait on the title page of Claudius’ volume makes clear (Figure 9), parents shared their children’s burden of responsibility. They had to make themselves worthy of that all-consuming love, and return it. The father, mother, girl, and boy shown in the engraving are woven together, their hands entwined, their bodies pressed together in a tableau of idealized intimacy. They fulfill Weisse’s profession in the first issue of Der Kinderfreund, to love his own children “almost more than my life.”

FIGURE 9. Title-page illustration, Claudius (1783). Universitätsbibliothek Augsburg, shelfmark 221/GK 9951 C615 K6-1.2.

This sense of mutual devotion would become even more nostalgic and sentimentalized in the next century. In his Über naïve und sentimentalische Dichtung [On Naïve and Sentimental Poetry, 1795], Friedrich Schiller argued that young and old, like nature and the man-made, were incomplete in and of themselves:

They are what we were; they are what we should become once more. We were nature like them, and our culture should lead us along the path of reason and freedom back to nature. [. . .] We are free and what they are is necessary; we alter, they remain one. Yet only if both are combined with one another—only if the will freely adheres to the law of necessity and reason maintains its rule in the face of every change in the imagination, only then does the divine or the ideal emerge. [. . .] In the child are exhibited the potential and the calling, in us their fulfillment, and the latter always remains infinitely behind that potential and that calling (180–182; emphasis original).

Whether practical or sentimental, utilitarian or romantic, the mutual obligation between young and old, encapsulated in that compound word “Kinderfreund,” was modeled—indeed, transacted—in songs and ensembles for family members to sing to and with each other. None of them, not even the lullabies, were ever truly solos.

As that cold spring journey from Salzmann’s Unterhaltungen für Kinder und Kinderfreunde had allegorized so well, both everyday life and intergenerational rapprochement were treacherous, with many foreseen and unpredictable hazards along the way. But there would always be “Rosen auf den Weg gestreut,” roses strewn upon the path. The children’s authors, poets, and composers encountered here all seem to have shared the hope that, by affirming the blessings of familial affection, children might be helped to weather all of life’s dangers and challenges, while also reassuring their elders that all would be well. “Instantiating and celebrating themselves” in these participatory rituals (Dettmar, 2002, 20), German families consuming this repertoire were afforded both pretexts and scripts for performing the devoted family—along with enough pleasing music to make it worth rehearsing again and again.

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Funding assistance provided through a Frontiers.org partial fee waiver.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The author would like to thank Anicia Timberlake for her comments on an initial draft of this manuscript, as well as Julia Hyland Bruno, Brian Boyd, and the other organizers of the 2019 Columbia University Presidential Scholars in Society and Neuroscience conference, “The Transmission of Songs in Birds, Humans, and Other Animals,” for the invitation to present on this topic and share the research that formed the basis of the present article.

Allgemeine Bibliothek für das Schul- und Erziehungswesen in Deutschland (Nördlingen, 1773-1784/86)Allgemeine deutsche Bibliothek (Berlin and Stettin, 1765-1796)Amaliens Erholungsstunden (Stuttgart, 1790-1792)Briefwechsel der Familie des Kinderfreundes (Leipzig, 1784-1792)Der Critische Musicus (Hamburg, 1737-1738, 1740)Der Greis (Magdeburg, 1763-1769)Der Kinderfreund. Ein Wochenblatt (Leipzig, 1775-1782)Mannigfaltigkeiten. Eine gemeinnützige Wochenschrift (Berlin, 1770-1773)Musikalisches Kunstmagazin (Berlin, 1782, 1791)Neue allgemeine deutsche Bibliothek (Kiel, 1793-1803)Unterhaltungen (Hamburg, 1766-1770)Unterhaltungen für Kinder und Kinderfreunde (Leipzig, 1778-1787)Wöchentliche Nachrichten und Anmerkungen die Musik betreffend (Leipzig, 1766-1770).

Abert, A. A., and Bauman, T. (2001). “Hiller, Johann Adam,” in Grove Music Online (Retrieved Feb 1, 2021).

Abert, A. A., and rev Bauman, T. (2001). “Weisse, Christian Felix,” in Grove Music Online (Retrieved Feb 1, 2021).

Basedow, J. B. (1770). Das Elementarwerk: Ein geordneter Vorrath aller nöthigen Erkenntniß; Zum Unterrichte der Jugend, von Anfang, bis ins academische Alter, Zur Belehrung der Eltern, Schullehrer und Hofmeister, Zum Nutzen eines jeden Lesers, die Erkenntniß zu vervollkommnen; In Verbindung mit einer Sammlung von Kupferstichen, und mit französischer und lateinischer Uebersetzung dieses Werkes. Dessau 4.

Benda, G. (1787). Das Findelkind, oder Unverhoft kömmt oft, eine Operette aus dem Briefwechsel der Familie des Kinderfreundes in Musik für das Pianoforte oder Clavier gestetzt. Leipzig: Schwickert.

Berger, A. A., and Cooper, S. (2003). Musical Play: A Case Study of Preschool Children and Parents. J. Res. Music Educ. 51, 151–165. doi:10.2307/3345848

Brand, M. (1986). Relationship between Home Musical Environment and Selected Musical Attributes of Second-Grade Children. J. Res. Music Educ. 34, 111–120. doi:10.2307/3344739

Bruce, E. (2015). Reading Agency: The Making of Modern German Childhoods in the Age of Revolutions (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota). dissertation.

Brüggemann, T., and Ewers, H.-H. (1982). Handbuch zur Kinder- und Jugendliteratur: Von 1750 bis 1800. Stuttgart: J. B. Metzlersche Verlagsbuchhandlung.

Burmann, G. W. (1774). G. W. Burmanns Kleine Lieder für kleine Mädchen und Knaben. Musik gesetzt von J. G. H. Nebst einem Anhang etlicher Lieder aus der Wochenschrift: Der Greis. Zu Zweyen Stimmen ausgesetzt. Zurich: David Bürgkli.

Buch, D. (2014). Liedersammlung für Kinder und Kinderfreunde am Clavier (1791): Frühlingslieder and Winterlieder. Middleton, WI: A-R Editions.

Burmann, G. W. (1773). Kleine Lieder für kleine Maedchen. Berlin and Königsberg: G. I. Decker and G. L. Hartung.

Cardi, C. (1982). “Christian Felix Weiße (1726-1804): Schauspiele Für Kinder. Aus Dem Kinderfreunde Besonders Abgedruckt. 3 Teile. Leipzig 1792,” in Handbuch zur Kinder- und Jugendliteratur: Von 1750 bis 1800 Editors T. Br̈ggemann, and H.-H. Ewers (Stuttgart: J. B. Metzlersche Verlagsbuchhandlung), 174–187.

Cardi, C. (1983). Das Kinderschauspiel der Aufklärungszeit: Eine Untersuchung der deutschsprachigen Kinderschauspiele von 1769-1800. Frankfurt: Peter Lang.

Claudius, G. C. (1780). Lieder für Kinder mit neuen sehr leichten Melodieen [sic]. Frankfurt: Heinrich Ludwig Brönner.

Custodero, L. A., and Johnson‐Green, E. A. (2008). Caregiving in Counterpoint: Reciprocal Influences in the Musical Parenting of Younger and Older Infants. Early Child. Develop. Care 178, 15–39. doi:10.1080/03004430600601115

Custodero, L. A. (2006). Singing Practices in 10 Families with Young Children. J. Res. Music Educ. 54, 37–56. doi:10.1177/002242940605400104

Dettmar, U. (2002). Das Drama der Familienkindheit: Der Anteil des Kinderschauspiels am Familiendrama des späten 18. und frühen 19. Jahrhunderts. Munich: W. Fink.

Dieke, G. (1934). Die Blutezeit des Kindertheaters: ein Beitrag zur Theatergeschichte des 18. und beginnenden 19. Jahrhunderts. Emsdetten: Lechte.

Düll, S., and Wallnig, J. (1996). Amaliens musikalische Erholungsstunden: Musikbeispiele einer Monatsschrift 1790-1792. Sankt Augustin: Academia Verlag.

Ewers, H.-H. (2010). “Sie hüpfen fröhlich herum und freuen sich.’ August Rodes Kinderschauspiele im Kontext von Empfindsamkeit und Philanthropismus (1998),” in Erfahrung schreib’s und reicht’s der Jugend: Geschichte der deutschen Kinder- und Jugendliteratur vom 18. Bis zum 20. Jahrhundert. Gesammelte Beiträge aus drei Jahrzehnten (Frankfurt: Peter Lang), 79–89.

Freitag, T. (2001). Kinderlied: Von der Vielfalt einer musikalischen Liedgattung. Frankfurt: Peter Lang. doi:10.3790/978-3-428-50439-8

Gleixner, U., and Gray, M. W. (2006). “Introduction: Gender in Transition,” in Gender in Transition: Discourse and Practice in German-Speaking Europe 1750-1830 (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press), 1–24.

Gramit, D. (2002). Cultivating Music: The Aspirations, Interests, and Limits of German Musical Culture, 1770-1848. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Head, M. (1999). "If the Pretty Little Hand Won't Stretch": Music for the Fair Sex in Eighteenth-Century Germany. J. Am. Musicological Soc. 52, 203–254. doi:10.1525/jams.1999.52.2.03a00010

Head, M. (2013). Sovereign Feminine: Music and Gender in Eighteenth-Century Germany. Berkeley: University of California Press. doi:10.1525/california/9780520273849.001.0001

Heckle, G. (1987). “‘Ein lehrreiches und nützliches Vergnügen’—Das Kauf- und Lesepublikum der Kinderzeitschriften des 18. Jahrhunderts,” in Wege zur Kommunikationsgeschichte. Editors M. Bobrowsky, and W. R. Langenbucher (Munich: Ölschläger), 317–341.

Hiller, J. A. (1778). Die kleine Aehrenleserinn, eine Operette in einem Aufzuge, für Kinder. Leipzig: Siegfried Lebrecht Crusius.

Hurrelmann, B. (1974). Jugendliteratur und Bürgerlichkeit: Soziale Erziehung in der Jugendliteratur der Aufklärung am Beispiel von Christian Felix Weißes ‘Kinderfreund’ 1776–1782 (Paderborn: Ferdinand Schöningh).

Jann, F. X. (1782-1821). Etwas wider die Mode: Gedichte und Schauspiele ohne Caressen, und Heurathen, für die studierende Jugend. Augsburg: Riegers Sel. Söhnen. 7.

Joubert, E. (2006). Songs to Shape a German Nation: Hiller's Comic Operas and the Public Sphere. Eighteenth Century Music 3, 213–230. doi:10.1017/s1478570606000583

Lathey, G. (2006). “The Translator Revealed: Didacticism, Cultural Mediation and Visions of the Child Reader in Translators’ Prefaces,” in Children’s Literature in Translation: Challenges and Strategies. Editors J. V. Coillie, and W. P. Verschueren (London: Routledge), 1–18.

Löffler, K., and Stockingern, L. (2006). Christian Felix Weisse und die Leipziger Aufklärung. Hildesheim: Georg Olms.

Köberle, S. (1972). Jugendliteratur zur Zeit der Aufklärung: ein Beitrag zur Geschichte der Jugendschriftenkritik. Weinheim: Beltz.

Krämer, J. (1988). Deutschsprachiges Musiktheater im Späten 18 Jahrhundert: Typologie, Dramaturgie and Anthropologie einer Populären Gattung. Tübingen: M. Niemeyer.

Mai, A.-K. (2003). Christian Felix Weiße (1726 -1804): Leipziger Literat zwischen Amtshaus, Bühne und Stötteritzer Idyll. Beucha: Sax-Verlag.

Mairbäurl, G. (1983). Die Familie als Werkstatt der Erziehung: Rollenbilder des Kindertheaters und soziale Realität im späten 18 Jahrhundert. Munich: R. Oldenbourg.

Mittler, E., and Wangerin, E. (2004). “Nützliches Vergnügen: Kinder- und Jugendbücher der Aufklärungszeit aus dem Bestand der Niedersächsischen Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Göttingen und der Vordemann-Sammlung,” in Göttingen: Niedersächsische Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek.

Mueller, A. (2013). Youth, Captivity and Virtue in the Eighteenth-Century Kindertruppen. Eighteenth Century Music 10, 65–91. doi:10.1017/s147857061200036x

Mueller, A. (2011). Zauberkinder: Children and Childhood in Late Eighteenth-Century Singspiele and Lieder. [Berkeley (CA)]: University of California. PhD thesis.

Nicolai, F. (1783-1796). Beschreibung einer Reise durch Deutschland und die Schweiz. Berlin and Stettin, n.p., 12

O’Hagin, I. B., and Harnish, D. (2003). Reshaping Imagination: The Musical Culture of Migrant Farmworker Families in Northwest Ohio. Bull. Counc. Res. Music Educ. 151, 21–30.

Pape, W. (1981). Das literarische Kinderbuch: Studien zur Entstehung und Typologie. Berlin: De Gruyter. doi:10.1515/9783110844627

Parsons, J. (2004). “The Eighteenth-Century Lied,” in The Cambridge Companion to the Lied. Editor J. Parsons (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 35–62.

Rehle, B. (1989). Aufklärung und Moral in der Kinder- und Jugendliteratur des 18. Jahrhunderts. Frankfurt: Peter Lang.

Reichardt, J. F. (1779-1780). Oden und Lieder von Klopstock, Stolbert, Claudius und Hölty. mit Melodien beym Klavier zu singen. Berlin: Joachim Pauli, 2.

Reichardt, J. F. (1798). Wiegenlieder für gute deutsche Mütter. Leipzig: Gerhard Fleischer der Jünger.

Riley, M. (2004). Musical Listening in the German Enlightenment: Attention, Wonder and Astonishment. Aldershot: Ashgate. doi:10.4324/9781315090702

Rose, S. (2019). “German-language Music Criticism before 1800,” in The Cambridge History of Music Criticism. Editor C. Dingle (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 104–124. doi:10.1017/9781139795425.007

Rousseau, J.-J. (1762). Émile, ou de l’éducation. Trans. and ed. Christopher Kelly and Allan Bloom as Emile or On Education (2010). Hanover: University Press of New England.

Scheibe, J. A. (1766). Kleine Lieder für Kinder zur Beförderung der Tugend. Mit Melodien Zum Singen Beym Klavier. Flensburg: Johann Christoph Korte, 2 vols.

Schiller, F. (1795). “On Naïve and Sentimental Poetry,” trans. D. O. Dahlstrom, in Essays (1993). Editors W. Hinderer, and D. O. Dahlstrom (New York: Continuum), 179–260.

Schilling-Sandvoß, K. (1996). “Kinderlieder des 18. Jahrhunderts als Ausdruck der Vorstellungen vom Kindsein,” in Geschlechtsspezifische Aspekte des Musiklernens. Editor J. Hermann Kaiser (Essen: Die Blaue Eule: Musikpädagogische Forschung 17), 170–189.

Seidel, C. A. G. (1780). Sammlung von Kinderschauspielen mit Gesängen. Göttingen: Johann Christian Dieterich.

Smeed, J. W. (1988). Children's Songs in Germany from the Eighteenth to the Twentieth Centuries. Forum Mod. Lang. Stud. 24, 234–247. doi:10.1093/fmls/xxiv.3.234

Trehub, S. E., Unyk, A. M., Kamenetsky, S. B., Hill, D. S., Trainor, L. J., Henderson, J. L., et al. (1997). Mothers' and Fathers' Singing to Infants. Develop. Psychol. 33, 500–507. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.33.3.500

Trehub, S. E., Unyk, A. M., and Trainor, L. J. (1993). Adults Identify Infant-Directed Music across Cultures. Infant Behav. Develop. 16, 193–211. doi:10.1016/0163-6383(93)80017-3

Uphaus-Wehmeier, A. (1984). Zum Nutzen und Vergnügen—Jugendzeitschriften des 18. Jahrhunderts. Ein Beitrag zur Kommunikationsgeschichte. Munich: K. G. Saur.

Volk, A. A., and Atkinson, J. A. (2013). Infant and Child Death in the Human Environment of Evolutionary Adaptation. Evol. Hum. Behav. 34, 182–192. doi:10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2012.11.007

Weisse, C. F. (1769). Lieder für Kinder, vermehrte Auflage. Mit neuen Melodien von Johann Adam Hiller. Leipzig: Weidmanns Erben und Reich.

Werthes, F. A. C. (1774). Lieder eines Mägdchens, beym Singen und Claviere. Münster: Philipp Heinrich Perrenon.

Keywords: children, eighteenth century, Enlightenment, families, Germany, Lieder, Singspiele, songs

Citation: Mueller A (2021) Roses Strewn Upon the Path: Rehearsing Familial Devotion in Late Eighteenth-Century German Songs for Parents and Children. Front. Commun. 6:705142. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2021.705142

Received: 04 May 2021; Accepted: 27 July 2021;

Published: 03 September 2021.

Edited by:

David Rothenberg, New Jersey Institute of Technology, United StatesReviewed by:

Paromita Pain, University of Nevada, United StatesCopyright © 2021 Mueller. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Adeline Mueller, YW11ZWxsZXJAbXRob2x5b2tlLmVkdQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.